The Paris Review's Blog, page 94

December 9, 2021

Two Self-Portraits

Illustration by Na Kim

Self-Portrait 1

I cannot:

cook

pull off a hat

entertain

wear jewelry

arrange flowers

remember appointments

send thank-you cards

leave the right tip

keep a man

feign interest

at parent-teacher conferences.

I cannot

stop:

smoking

drinking

eating chocolate

stealing umbrellas

oversleeping

forgetting to remember

birthdays

and to clean my nails.

Telling people what they want to hear

spilling secrets

loving

strange places

and psychopaths.

I can:

be alone

do the dishes

read books

form sentences

listen

and be happy

without feeling guilty.

Self-Portrait 5

I once stood

and waited

by BT-Centralen

for someone who never came.

I loved him.

My youth

fell away

in flakes.

I pretended to be

eagerly reading

the news ticker and

personally affected

by the report of

Gustaf Munch-Petersen’s death

in the Spanish Civil War.

Why

didn’t he come?

I shouldn’t have

denied him

my pesky virginity.

My friend told me

you can tell

by a girl’s eyes

whether she still has it

or not.

An old lady

stood next me

under an open umbrella.

The skin on her neck

looked like a turkey’s.

I wished I

were her

because she

was nearer death.

All my life I’ll remember

her face

all my life I’ll remember

Gustaf Munch-Petersen’s

name

and envy him his fate.

In the bookstore’s window stood

And Now We Await a Ship

by Marcus Lauesen.

I never got around to reading it

I think of it

reluctantly

each time I pass by

BT-Centralen

where

a girl in a miniskirt

is pretending to be

deeply engrossed

in the news ticker’s flickering

words about Vietnam

Biafra and the student protests.

For a moment she looks

at me

and envies me

because I am nearer death.

She will never forget

my face.

Translated from the Danish by Jennifer Russell and Sophia Hersi Smith.

Tove Ditlevsen (1917—1976) was a Danish poet, fiction writer, and essayist. Four more of her poems, about divorce, appear in the Winter issue of The Paris Review, no. 238.

Jennifer Russell and Sophia Hersi Smith live in Copenhagen. Their cotranslation of All the Birds in the Sky by Rakel Haslund-Gjerrild was awarded the American-Scandinavian Foundation’s 2020 Translation Prize. They are currently translating My Work by Olga Ravn.

December 8, 2021

238 Announcement

This past summer, I kept turning to a certain kind of prose: the diaries in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, the biomythography of Audre Lorde, Elias Canetti’s journals, the field notes of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner. It seemed to promise me something, but what? The writing sometimes felt unpolished, as if the authors were allowing me to watch them work through a problem. It dealt with obsession, disappointment, depression. It wasn’t an obvious choice for the subway.

This past summer, I kept turning to a certain kind of prose: the diaries in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, the biomythography of Audre Lorde, Elias Canetti’s journals, the field notes of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner. It seemed to promise me something, but what? The writing sometimes felt unpolished, as if the authors were allowing me to watch them work through a problem. It dealt with obsession, disappointment, depression. It wasn’t an obvious choice for the subway.

I had just started editing The Paris Review, a literary quarterly with a formidable sixty-eight-year record of publishing the best writing, and of hosting glamorous parties. Every morning, in the office, I made coffee under the gaze of a bronze George Plimpton, one of the founding editors. The space was dominated by a monumental bookshelf that housed an archive of past issues. The overall effect was beautiful, and a little forbidding. And yet, when I took down the first issue, I couldn’t help but notice that it was rather small, like a pamphlet. It featured William Styron’s famous manifesto for the Review, in which he writes that the new quarterly should emphasize work not by critics but by “the good poets and the good writers, the non-drumbeaters and the non-axe-grinders.” But even that piece of writing was less grandiose than I had remembered, irreverently presented in the form of a private letter, a set of notes to a committee of editors struggling to make a public statement.

When I first encountered the Review as a teenager, I had only the vaguest sense of its history. What I liked were the interviews with famous writers, conducted by younger ones seeking to learn. They seemed to offer an unprecedented form of access. I had assumed that the purpose of a magazine was to equip you with something usable, to help you to follow what other people were talking about. The Paris Review was not that sort of publication. Over the years, it provided the reading list I really wanted, one that privileged mischief, strangeness, and pleasure: Jane Bowles, Raymond Carver, Lydia Davis, Akhil Sharma, Morgan Parker.

In keeping a distance from criticism and the debates of the day, the Review has always created a space for something more intimate, for the writing that makes us feel that we are in proximity to another consciousness. This is what my colleagues and I have been after these past months, and what we will continue to seek, whether in work by established, lesser-known, or very new writers, in English or translation, in poetry or prose, in very short stories or very long ones, in fiction or nonfiction or something in between.

Our new Winter issue is launching online today, and it will be available on newsstands later this month. (If you are a current subscriber, it may have already reached your mailbox, or certainly will soon.) As you may know, it looks a little different from the issues of recent years, though some longtime readers will recognize the new design as a kind of return. Our designer, Matt Willey, was inspired in part by the issues of the seventies. These issues were printed on soft pages; their spines crack in the places where they are most often opened. They are small enough to hide in a big coat pocket, or to hold in one hand while reading on the subway or in bed.

December 7, 2021

Reading Upside Down: A Conversation with Rose Wylie

Photo: Emily Stokes

Rose Wylie, whose watercolor Two Red Cherries appears on the cover of the Review’s Winter issue, lives in a cottage in Kent, England, that smells of firewood. A treacherous, narrow staircase leads up to a small studio. (“Hold the rail!” Wylie warned me.) Her large, funny, vibrant figurative paintings—made on unprimed, unstretched canvas—cover the walls and floor. When I visited on a recent Saturday afternoon, as Storm Arwen brewed outside, she told me she had spent the first years of her life in India, where her father worked as an engineer. The family moved back to England during the Second World War. Wylie studied at an art school in Kent and then a teacher-training program at Goldsmiths where, at nineteen, she met her husband, the painter Roy Oxlade. She put her own professional ambitions aside to raise their children, channeling her artistic energies, she said, into “soups, jam, clothes, curtains, and Christmas cards.” In her forties, she completed a degree at the Royal College of Art, and worked in relative obscurity until eventually, in her late seventies, her career started to take off, with solo exhibitions at Tate Britain and elsewhere. We talked at her kitchen table, drinking Lapsang tea. The mince pies I’d brought from London had crumbled on the journey, which seemed to delight her.

INTERVIEWER

How did people respond to your work in the early years?

WYLIE

I got very little response. I was considered a mother and a wife, married to an artist who was more prominent, and so whatever I did didn’t get a lot of recognition. That made me want to do it more, and more defiantly. I just thought, Bugger this! It was an impetus.

INTERVIEWER

How did you develop your style?

WYLIE

Look at that painting behind the dining table. That was one of my early ones, and it could just as well have been done yesterday. It’s peculiar to me when critics say that my paintings are naive or childish. I choose to work in a way I find exciting. “Naive” would be making unformed judgements, with no intellectual framework. Why is it childish, just because it doesn’t happen to look like a da Vinci or a Rembrandt?

INTERVIEWER

Why did you choose to make such big paintings?

WYLIE

I think it was a reaction against having learned to paint on a small easel—or perhaps against the idea that, unlike a male artist, a woman should be happy to do a little picture on the kitchen table. It was a sign of belief in what I did. Sometimes an artist will invent a constraint or difficulty to make his work less slick or more powerful, more grounded in reality—I didn’t have to do that. The difficulty was already there. I’d be in the shed in the winter, in a howling gale, wearing a big coat, sizing up these huge canvases, trying to staple them to the walls. Sometimes the canvases would blow off and wrap themselves around me.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you think your self-belief came from?

WYLIE

My mother was born in 1885, and esteem was allocated to the sons, and after that it was given by age. I was the youngest of seven, and a girl, so I had no position. Some people are born with prime time. I didn’t have that. I made my own games. I didn’t expect to be taken to places for amusement, or given treats. That was a great freedom. I just thought, Well, if I don’t do things my own way, then there’s no hope.

INTERVIEWER

Was it difficult to be married to a painter in the years when you weren’t painting yourself?

WYLIE

It was okay because I read all the time—Dostoyevsky and Chekhov, Mallarmé, Proust, Flaubert, Stendhal, Balzac. Roy and I would go to see shows, and artists would come to visit us. I wasn’t actually putting the brush on the canvas, but I’ve always done a bit of drawing, and I would draw and paint with the children. And I thought my husband was great. We were huge mates. He was dynamic, moody, attractive, funny. I’d do the meals—Roy liked small quantities of food, beautifully presented—but I would also make my own arrangements. I’m used to doing my own thing as well as the other person’s. When I was little, four or five, I learned to read upside down from looking at the book my brother was holding. He always had the book the right way up, so he could only read that way. I could do both.

INTERVIEWER

Did you and your husband have very different ways of working?

WYLIE

Roy was very ordered. I called him a good Bauhaus boy—he was all about form following function. His driving force was rationality whereas mine was a more female intelligence. I sometimes think of that artist who made casts from piss holes in the snow—Helen Chadwick. The man’s is a deep hole, very focused; the woman’s is more scattered and covers more ground. That was like us. Roy was Plato and I was Aristotle. He didn’t like imperfection. I don’t mind imperfection at all, only I don’t call it imperfection—I call it “wearing out” or “it’s got a stain on it” or “it’s falling apart.” Like your mince pie. Roy was always trying to find the ideal subject. I saw subjects everywhere. You use what you’ve got. It could be a crack in the floor, a fingernail, a gooseberry cutting. You know when you clip the tops off, and you have a little pile of tops and tails? I used to think they were stunning.

Photo: Emily Stokes

INTERVIEWER

Have you always made work from observation?

WYLIE

Yes. I maintain that figuration is more difficult than abstraction. People tell me I’m just being controversial, but figuration can be so bad and so distorted, so simpering or too elegant. With abstraction you haven’t quite got those problems. Maybe that is the problem of abstraction—that you haven’t got the problems.

You see these twigs out here? I’ve drawn little birds that sit on those twigs, from underneath. That’s a japonica. It’s related to the quince. The fruit are coral-colored, and there were thirty-seven of them on the ground this year. Never before have I had any. They were like golden apples, Aphrodite stuff. When I make a painting, I observe, but I also transform. You’re observing that they are this color, this shape, this size. They look like this, they feel like this, they smell like this. And then you try to put those things together in a painting.

Recently I’ve been painting a woman I saw running down the hill with her dog on a leash behind her. She was running with her knees right up, and leaning back because of the hill, and she formed such a strong image in my mind. She reminded me of an Assyrian sculpture. The first painting I did of her, I didn’t have the leg right, so I did another one.

Photo: Emily Stokes

INTERVIEWER

What are you thinking about while you paint?

WYLIE

Not much. Sometimes I speak to myself. I say, “Get it off, get it off.” Or “Scrape it off, get rid of it.” Or “Put it back.” I swear quite a bit.

INTERVIEWER

What kind of swearing?

WYLIE

I usually say “Fuck!”—because something has gone wrong, and I think, Now it’s horrible, I hate it! It was alright before, why didn’t I fucking leave it alone?

INTERVIEWER

How long is a painting session?

WYLIE

It’s so variable. Sometimes I’ll go up to my studio and do something in ten minutes and come down again. On other days I’ll go into the studio at about ten or half-past ten, and then miss lunch and go on till three, maybe have a late lunch and go on straight through the evening. Or I’ll have some supper and a glass of wine and then go back to the studio and think, Shit, it’s not right, I can’t leave it like that! And then I’ll try to get it right, and work until three in the morning, and it’ll go even more wrong. Some people say, “You must be having a whale of a time doing just what you want to do,” but it’s not like that. You’re always frightened to start—you don’t want to because it’s too difficult. It’s much easier to look out of the window or read a book. But then, when you’re actually in it, you escape from everything. You escape from climate change, people dying of famine, cows dropping dead. I hate the whole business of what’s happening in the world. My politics are green. We should eat local stuff, carrots and swedes. Not cherries from Washington—how obscene.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about the cherries in the painting we used on the cover of the Winter issue. Where did they come from?

WYLIE

There were a lot of wild cherries growing at the top of the garden, very dark red. I think they’re completely beautiful, cherries. They made me think of those sixteenth-century Spanish still life paintings. I like the way they hang in doubles. If you look at the painting, it’s like two breasts with large nipples.

INTERVIEWER

I saw that you had recently painted your cat, Pete. Did the pandemic affect what you painted or how you worked?

WYLIE

This is a highly intelligent cat. Watch him. Do you want supper, Pete? Did you see? He understands the word. Sometimes he jumps up onto my shoulder, and he puts one paw on one side and another paw on the other side, and he puts his arms around me. I know cats are affectionate, but this one is extraordinary.

As to the pandemic, I’m often here by myself so in fact there was very little difference. The only problem was that at one point my assistants couldn’t come to collect my paintings, so I would just staple one canvas on top of another on the wall. Having a piece of work superimposed onto another unrelated one like that led to something new, where I started to make paintings that had abrupt changes of image on the same canvas. Eventually my assistants came over wearing gloves and masks to collect the canvases. I left them little diagrams to show them what to do with each one. I actually liked those drawings. They were part of the pandemic and they became part of the work.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel when a painting leaves your studio?

WYLIE

I think, Well, thank heavens that’s done. I always want my paintings to go into a museum. That is what all artists want. Although private collections are good, too. That gives you money. Fuck it, my paint bills are huge.

Photo: Emily Stokes

Emily Stokes is the editor of The Paris Review.

December 5, 2021

Redux: In Honor of Jamaica Kincaid

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Cover art by Jonathan Borofsky.

In our Winter 1981 issue, The Paris Review published an early story by Jamaica Kincaid. Titled “What I Have Been Doing Lately,” it follows the narrator’s recursive, dreamlike journey in search of home. (You can listen to her reading it on the inaugural season of The Paris Review Podcast.) The story was included in Kincaid’s 1983 debut collection, At the Bottom of the River, which drew from her early life in Antigua and marked her as a singular voice in American letters. Kincaid has gone on to publish five novels and five books of nonfiction—she was a prolific New Yorker Talk of the Town columnist—as well as many other stories. In 2020, the Daily published two of her essays, “I See the World” and “Inside the American Snow Dome.”

It’s our pleasure to announce that on April 12, 2022, The Paris Review will present the Hadada, our annual lifetime achievement award, to Jamaica Kincaid at our Spring Revel.

To celebrate, we’re highlighting the work of previous Hadada winners in this week’s Redux. Read on for the Art of Fiction no. 223 with Joy Williams, Kincaid’s short story “What I Have Been Doing Lately,” N. Scott Momaday’s poem “Concession,” and a series of collages by John Ashbery.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Eleven Collages by John Ashbery.

Interview

Joy Williams, The Art of Fiction No. 223

Issue no. 209 (Summer 2014)

The Keys were still kind of strange and unspoiled in the eighties. I went around the state and wrote things down, but nobody talked to me. Nobody! I’d limp into these bed-and-breakfasts and people would snarl at me and not want to talk. I mean, honestly, it was terrible and I had no idea what I was doing. And it wasn’t edited, nobody edited it.

Eleven Collages by John Ashbery.

Fiction

What I Have Been Doing Lately

By Jamaica Kincaid

Issue no. 82 (Winter 1981)

What I have been doing lately: I was lying in bed and the doorbell rang. I ran downstairs. Quick. I opened the door. There was no one there. I stepped outside. Either it was drizzling or there was a lot of dust in the air and the dust was damp. I stuck out my tongue and the drizzle or the damp dust tasted like government school ink. I looked north. I looked south. I decided to start walking north. While walking north I decided that I didn’t have any shoes on my feet and that is why I was walking so fast.

Eleven Collages by John Ashbery.

Poetry

Concession

By N. Scott Momaday

Issue no. 99 (Spring 1986)

Believe the sullen sense that sickness made,

And broke you in its hands.

Believe that death inhabits the mere shade

Intimacy demands.

I drink, my love, to your profound disease;

Its was the better suit.

I could not have provided you this ease,

Nor this peace, absolute.

Eleven Collages by John Ashbery.

Art

Eleven Collages

By John Ashbery

Issue no. 188 (Spring 2009

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

December 3, 2021

The Review’s Review: Telegraphic, Incandescent

Still from Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993) courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

Years ago, I went to go and watch the Mike Leigh movie Another Year at a cinema in Bristol. It is a typical Mike Leigh film in that it is just about matchless in its emotional acuity, punctuated by shots where the camera lingers for about ten seconds more than is tolerable on the face of a character who has either had a shit life or is going to go on to have a shit life; it’s funny; it has an overall aesthetic atmosphere that makes you think of allotments even when an allotment never appears on screen; and it’s hellbent on presenting the most unglamorous vision of London that could possibly exist.

Having arrived at the scene where the desperately unhappy woman makes a drunken pass at her friends’ son, I clapped my hand over my mouth. I was seated at the end of a row of women—my mum, one of her oldest friends and her two daughters, and two of her daughter’s friends—and I remember turning to see that all seven of us had done the same thing. Just sitting there in the cinema with our hands over our mouths and our eyes as big as they could go, wondering why we had allowed Mike Leigh to do this to us, again.

I had this experience in mind two weeks ago when I went to go and see Naked, Leigh’s recently reissued 1993 film. I knew that it would be brilliant, and that it would cause me to wish I could unzip my own skin and crawl out of it at least once, and that it would complicate my already complicated feelings about English people, because I have this response to many of his films, but of course I was not fully prepared. It’s the best film I’ve seen this year, easily, and feels both entirely fresh and like an artifact of another era altogether. —Rosa Lyster (author of “On the Alert for Omens: Rereading Charles Portis,” out this week on the Daily)

I’ve been immersing myself in the writings of the Egyptian intellectual and revolutionary Alaa Abd El-Fattah, who has been imprisoned for much of the past decade. In You Have Not Yet Been Defeated, recently published by Fitzcarraldo, an anonymous collective has gathered and translated his essays, conversations, and social media posts, notes and fragments, many smuggled out of prison at great risk. It includes the 2014 prose poem “Graffiti for Two,” a collaboration with fellow inmate Ahmed Douma that was created by shouting across a long row of cells in the night. Alaa’s words are telegraphic and incandescent as he reflects upon tyranny, technology, and despair, as well as the failures of Egypt’s 2011 revolution, defeat without shame, where a dark optimism could be found. The book is a crucial testament to a history that is still alive. As Naomi Klein writes of Alaa in her introduction, “He has time only for words that hold out the possibility of materially changing the balance of power.” —Anna della Subin (author of “White Gods,” out this week on the Daily) Phototaxis , by the Canadian writer Olivia Tapiero, is a novel that oozes, much like the rotting meat strewn across its unnamed cityscape. Translated from the French by Kit Schluter, it follows a cast of characters that includes classical pianist Théo Schultz, a man addicted to both snuff films and the more metaphorical death drive that undergirds the artistic will, who eventually throws himself off a building. “Desire is one form of suicide,” notes Tapiero, in a characteristically beautiful line near the book’s beginning. “As with the last glance we shoot out at the crowd, we shoot ourselves with a blank.” —Rhian SasseenDecember 2, 2021

Jamaica Kincaid Will Receive Our 2022 Hadada Award

Jamaica Kincaid. Photo: Kenneth Noland.

Save the date: on April 12, 2022, The Paris Review will present the Hadada, our annual lifetime achievement award, to Jamaica Kincaid at our Spring Revel.

In our Winter 1981 issue (no. 82), the Review published a short story by Kincaid, then thirty-two, titled “What I Have Been Doing Lately.” The story follows the narrator’s recursive, dreamlike journey in search of home, and was later included in Kincaid’s debut collection, At the Bottom of the River (1983), which drew from her early life in Antigua and marked her as a singular voice in American letters. The book won the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and was nominated for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Also in the collection is the indelible “Girl,” a 650-word sentence of practical instructions uttered by a mother to her daughter on how to avoid becoming “the kind of woman who the baker won’t let near the bread.”

Kincaid has gone on to publish five novels and five books of nonfiction, as well as many other stories and essays. In 2018, she appeared in the inaugural season of The Paris Review Podcast, reading “What I Have Been Doing Lately.” In 2020, the Daily published two of her essays, “I See the World” and “Inside the American Snow Dome” (which originally appeared in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter).

In the words of the Review’s publisher, Mona Simpson, “Jamaica’s sentences roam over hills and valleys, from local poverties and the bitter legacy of colonialism to the beauty of a single flower. I can’t think of another writer whose voice contains such intensities of rage and love. It is a sound incantatory, biblical, and full of music.”

Kincaid is now a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Lannan Literary Award for Fiction, the Prix Femina Étranger, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the Clifton Fadiman Medal, and the Dan David Prize for Literature. She is a professor of African and African American studies at Harvard, and will be a visiting writer at UCLA in the spring of 2022.

We are delighted to add the Hadada to Kincaid’s array of accolades, in recognition of the impact that her remarkable body of work continues to have on readers and writers. Previous recipients of the Hadada include Joy Williams, Deborah Eisenberg, James Salter, Joan Didion, and the 2021 winner, N. Scott Momaday (a full list can be found here).

After canceling the Spring Revel in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we look forward to coming together again. We’ll mingle, present the Hadada and the Plimpton Prize—our award for emerging writers—and raise a glass in gratitude to the literature that has kept us company over the past two years. To join us, buy your ticket today.

#nyc #adayinmylife

Screenshot from “Restaurant Reviews: Lucien” video by @theviplist

Earlier this year I was obsessed with watching movies set in New York: campy comedies like Martin Scorsese’s After Hours felt like a night out when I was still hiding at home; erotic thrillers like A Perfect Murder and Dressed to Kill made the city seem more enticingly dangerous than it was during lockdown. As New York reopened, I stopped watching movies and started going out. Dining at restaurants, once a luxury, felt like a necessity—a way of re-entering the fantasy world of New York that I had streamed over the past year. It didn’t matter where I was going or who I was dining with. I just wanted to be out and around people, to feel like a main character living in New York City.

I’m not the only one who’s been going out more, at least according to TikTok. On my feed, iPhones pan across crowded New York City restaurants and plates loaded with steaks and pastas and gooey sauces, while raspy voice-overs celebrate or bemoan the food. These videos are more than restaurant reviews, they’re a sales pitch for the city—a reminder to whoever is watching that New York is back, and there’s no better way to celebrate than by spending money.

Like any other form of cultural mythmaking, TikTok generates desire for new experiences, shaping the way we navigate cities—and determining who gets to enjoy them. In the late eighties, the romantic blockbuster When Harry Met Sally functioned in part as a postcard for tourists and would-be New Yorkers curious about whether the infamous crime rates in Manhattan were beginning to decline. Harry and Sally, two University of Chicago graduates who move to the Empire State to pursue their careers—one becomes a journalist, the other a political consultant—experience the city as a land of promise, a place where good jobs and big apartments (and true love) present themselves to those willing and able to show up.

“A day in the life” videos on TikTok follow a similar narrative structure, showcasing the idealized lifestyles of college freshmen and entry-level marketers, most of them young white women, while they document their transition to NYC. Montages of neatly decorated studio apartments, strolls through Soho, and skyline vistas are punctuated by party scenes in rooftop lounges or laser-lit clubs. These videos provide an on-ramp to gentrification postlockdown, not unlike what When Harry Met Sally’s charming vignettes of Rockefeller Center, Macy’s, and now-iconic restaurants like Katz’s Delicatessen did for Mayor Giuliani’s “revitalization” of New York in the nineties. The majority of today’s New York–centric social posts are consumed by newcomers unbothered by unemployment rates or eviction moratoriums. Strung together in the feed, they generate a map for the young and upwardly mobile, whose idea of settling in the city isn’t finding or giving back to a community so much as engaging in commercial activities: spending money at bars and restaurants and boutiques to feel like they belong.

@katebartlettlife is good can’t complain##fashionstudent ##fashionschool ##nyc ##newyork ##dayinmylife ##dayinthelife ##fashioninstituteoftechnology♬ Call me – 90sFlav

@court0o0it was a chaotic day, gonna try again tomorrow ##homeless ##realliferecovery ##recovery ##SamsClubScanAndGo ##sober ##sobertok ##nyc ##harlem ##brooklyn ##fyp♬ Life Goes On – Oliver Tree

Of course, not all TikToks are made for or by privileged transplants. Some document rat infestations and street confrontations, and satirize the dreamy vignettes that glamorize moving to the city with views of garbage-filled courtyards. But these grittier NYC-Toks still mostly frame the hardships of city life as part of its quirky charm—moments when, as one user puts it, “New York is New York–ing.”

There are sobering exceptions, like an unflashy segment titled “a day in my life as a homeless recovering addict in nyc,” but they’re not easy to find, as TikTok moderators are instructed to suppress or filter out posts by those deemed too ugly (i.e., insufficiently young and white) or too poor. That’s why you’re more likely to see a video of Andrew Yang bumbling his way through a visit to a Midtown deli in an effort to prove himself a “real” New Yorker than a clip from the perspective of a deli worker.

@notfromdenmarkStop dreaming, start doing

#nyc #nycapartment #nycstudio #apartmenttour #manhattan♬ Runaway – AURORA

@wincxclubsuch an eventful day ##nyc ##viral ##fyp ##minigolf ##avocado ##halloween♬ Squid Game – Carrot

Those of us who use TikTok understand how the algorithm works—we have to strategize to ensure our place in the feed. And it’s so much easier to share experiences that play well in our online bubbles than to start putting roots down in our communities; we repeat the tropes we grew up seeing on Friends (set in New York but filmed in Los Angeles), romanticizing subway rides or trips to the deli. These fantastical and falsified narratives never capture what it feels like to really belong in a city. At least, I imagine they don’t. For now, like most NYC transplants, I’m still trying to play make-believe.

Taylore Scarabelli is a New York–based writer, consultant, and cofounder of Relevant Community. Her work has been published in New York Magazine, Artforum, Kaleidoscope, Spike, Vestoj, and more.

December 1, 2021

When You Misread the Title of a New Yorker Article Called “Going Home with Wendell Berry” as “Going Down On Wendell Berry”

© Gorilla /Adobe Stock

First you tease his hand-knit sweater with your greener thumb. You nudge it into that snail burrow beneath the wool. It is warm against Wendell Berry’s belly, and you consider leaving your thumb there forever. He would not mind. He would ask only that you join him at first light to hoe the earth, and not comment as he crumbles a pinch of soil between his fingers, and not ask how it is, exactly, that the particles fall in such perfect slo-mo. He would ask only that you join him under the hand-wrought pergola at the foot of his radish bed as he sips sugarless lemonade and pays gratitude to the clouds and the mycorrhizal network. He would ask only that you not try to his read his lips as they involuntarily mouth the objects of his gratitude. You think you catch him mouthing “Doritos,” but as you start to ask, he catches your eye in a steely way that tells you to back off.

Out of boredom, you tug a little on the navy wool of Wendell Berry’s sweater, undoing the cocoon in which you realize your thumb has begun to hope to turn into something new. He shudders a little at the ripple of cold air against his abdomen. Your thumb is saying: No, let us not go any further. Let us not do what we are programmed to do, how society and evolution have wired us to reap our worth. Let us instead stay here forever, above the waistband. Let us incubate in the warmth of Wendell Berry’s agricultural exertion. Let us listen to the roiling music of digestion. Let us crane to hear the music of the dirt—over half of Earth’s biodiversity clanging and gnawing and joining filaments beneath our feet, showing us another way to flourish, prospering by mending. Let us forget, temporarily, about the world beyond this farm, where roads are wet with oil slicks, clouds are pricked with jets, and flesh too easily torn open by lead traveling faster than the speed of sound. Let us believe we can go back to a time when man did not yet know about the stockpile of sunshine waiting beneath the soil—sunshine stolen by plants and condensed by time into a black reduction that can equip our every last fear. Let us believe the way back is through restraint: treading water by fingering dirt.

Wendell Berry has finished his glass of lemonade. He would like you to watch while he washes it with a garden hose. The very same garden hose he had in his boyhood. “Some inventions,” he chuckles, “don’t need upgrades!” It is the color of the flowerpot, from a time before your time, when hoses were not green.

He rinses the glass and, again, the droplets go instantaneously slo-mo. You wonder if Wendell Berry has ever been in a car wash. If he has sat back as his hulking vehicle is pulled onto a conveyor belt, as the lolling noodles slap and tickle his windshield, hiding him away, temporarily, from everything. You’re sure he could put the experience into better words but you doubt he’s ever had the pleasure.

So this is where the scene fades to black. You, with your thumb pressed to Wendell Berry’s belly, wondering if it will be able to resist gravity, trying to imagine what Wendell Berry would see in a car wash, wondering if his own thumb would head for the radio and twiddle the dial until he found some techno, and if he would then lean back, palms behind his head, leaving the steering wheel naked for a few moments (How long do you get in a car wash?) allowing himself to get lost in the suds and swashes, forgetting his fight, forgetting his dirt, forgetting the millions of strands of fungi reaching out to heal one another in the dark, forgetting that the car wash itself is an animate temple to his sworn enemy, forgetting about whether the moon is slowly getting closer or further from the Earth, and which it is of those two he fears more.

Lulu Miller is the author of the national best seller, Why Fish Don’t Exist. She is the cohost of Radiolab, and the cofounder of NPR’s Invisibilia. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Guernica, Orion, and beyond.On the Alert for Omens: Rereading Charles Portis

Annotated pages from the author’s copy of The Dog of the South

About a month ago, this man dropped an orange peel on me, deliberately, from the third-floor window of a pink apartment building on Bohdana Khmelnytsky Street in Kyiv, Ukraine. If you would like to picture the scene, you should imagine a man with the same shape of head and beard as Karl Marx, dressed in a high-necked white garment that sits at the intersection of “mystic” and “physician,” eating an orange and staring directly into the tired eyes of a woman who is wearing an ankle-length black coat that makes her feel like a corrupt but dignified old banker and big shiny black shoes that make her feel like a powerful car. I was on my way to the A. V. Fomin Botanical Garden a few streets away, and it was early enough in the morning that I had nothing in my head except the thought of how much I loved my shoes. I’d been gazing down at them as I walked, gloating over them in a way that was Rumpelstiltskinesque, when I realized someone was staring at me, hard, so I looked up and there was this man, in the pink building across the street, eating his orange with glazed conviction and giving off an aura of Rasputin.

We stood there for about thirty seconds, him at his window and me on my sidewalk, and then the business of making sustained eye contact with some kind of sinister holy man got to be too much for me, and I crossed the street so that I was right under his window, at an angle that made looking at each other impossible. This is when he dropped the orange peel. He timed it exactly, so that it bounced off my shoulder and onto my shoe. It was a good peel, as well, the practiced, unbroken spiral of someone who has spent a lot of time standing at windows issuing baffling communiqués through the medium of fruit. I looked at it for a bit, trying to figure out how to take the whole thing: Benediction or curse? Important or not important? I thought of picking up the peel and keeping it as a memento of whatever had just taken place, but my handbag already had too much bullshit in it, too many little rocks and ticket stubs, so instead I went to the café at the entrance to the gardens and wrote down what had happened, sitting at one of the wrought iron tables and whispering my shoes around in the drifts of leaves at my feet. “Clerical vibe to the white garment,” I wrote. “Seems like it would have a lot of buckles and straps going all up and down the inside of it.”

When you travel, these surplus encounters of unknown or dubious import occur all the time, and there is value in writing them down. They might become important later, or you may need to think about them when your life starts taking on an unrecognizable quality and you must pause in order to locate yourself within it. You believe you will remember exactly how it felt to be looking intently at a citrus peel while shifting from foot to foot on a navy blue morning so cold your hands are stiff little paddles in their pockets, and feeling so sad about something unrelated to oranges that the back of your neck actually physically hurts, this crawling ache that spreads all the way to your ears, but stuff like this vanishes unless you keep it somewhere. I’ve always known that the throwaway details are the ones you should hold on to, but I was never very good at doing that until I read Charles Portis’s The Dog of the South.

My friend Dan recommended the book to me, on the grounds that it would make me laugh more than anything I had ever read. This was an outrageous claim, and too much pressure to put on a novel about a man, Ray Midge, who makes his way from Arkansas to Honduras in an effort to track down his restless wife, Norma, after she has run off with her irritable first husband, Dupree—but Dan was right. I’d never read anything by Charles Portis before, and yet the shock of recognition I felt from the first page onward was strong enough to create the impression that I’d had his novels with me always, heard them read aloud as a baby, gone to sleep in pajamas printed with the words “Strength of Materials!” and on sheets that read over and over in tiny lettering: “The church arrest had grown out of a squabble with some choir members who had pinched him and bitten him and goosed him. They were trying to force him out of the choir, he said, because they claimed he sang at an odd tempo and threw them off the beat. One Sunday he turned on them and whipped at them with a short piece of grass rope. Some of the women cried.”

Trying to explain why this passage makes me laugh is like trying to explain why I like rivers more than oceans, or daisies more than roses, or extremely hard towels (like the ones in Portis’s Gringos: “Rough-dried in the sun. Very stiff and invigorating after a bath”) more than horrible, soft, fluffy ones. It is just my preference, something to do with my childhood. It’s the rhythm, maybe, or how evident it is that Portis is making himself laugh as he draws up the scene of this battle between Ray Midge’s travel companion, Dr. Reo Symes, and the choir members who are so destabilized by Symes’s presence that they are reduced to biting him, occasioning the retaliation involving the bit of grass rope. The phrase “turned on them and whipped at them.” The sentence “Some of the women cried.” I don’t know.

Portis’s imagination is truly wild—both unhampered and unpredictable—and reading him for the first time required a significant adjustment to all my previously gathered knowledge of what a person can or should put in a novel if they want it to be good. He is unbeatable at the non sequitur, so that every paragraph contains the possibility of crazed escalation. A conversation Ray has about the Bible with Reo Symes’s mother’s weird friend, Melba, starts with her asking him about a particular bit of Scripture and ends with her saying she will thank him to remember that “all the little animals of your youth are long dead.” At one point, Ray is treated “to some Pepsi-Colas” by another of his temporary traveling companions, a small boy called Webster Spooner, and expresses surprise because “most children are close with their money.” Portis favors the insertion of the unexpectedly specific question: “Can she make her own little skirts and jumpers?” “What about raisins? Does she like raisins?” “What kind of birds are they? … Can they talk? … Do they lay their tiny eggs in the road?” “Do you claim to know the meaning of every word in the Greek language?” The effect of these is to reveal that other people’s inner lives are remarkable, that each of us is walking around, at least 20 percent of the time, wanting the answers to questions no one else would have thought up if they lived to be as old as the hills. It’s hilarious to be in the company of a writer who thinks like this, who has his protagonist make sweeping, unkind observations about the financial habits of children or participate in arguments about who invented the clamp: “The principle of the clamp was probably known to the Sumerians. You can’t go around saying this fellow from Louisiana invented the clamp.”

But it’s not only that The Dog of the South is funny. I have been traveling constantly since June of this year, and it’s the only book I brought with me from home. Like almost every other decision I have made over the past few months, this one did not involve a lot of prior consideration—the novel was just there on top of a pile that happened to be near my open suitcase, and I needed something new to read, so I packed it. I had no idea what it would do to the way I write, which is to say, to the way I think about the world. Early on in the novel, when Ray is still in America, a man gives him a card that bears an impenetrable message. It says “Kwitcherbellyachin” on the front and “adios AMIGO and watch out for the FLORR” on the back. Ray has no idea what this means but considers it for a while anyway, because it seems like it could be important: “Tiny things take on significance when I’m away from home. I’m on the alert for omens. Odd things happen when you get out of town.”

They do happen. You are standing there on Kingsland Road in East London, having one of your nervous breakdowns about the strong likelihood of fucking up absolutely everything in your life, pouring a Diet Coke into your open mouth with your head tilted back at an angle that makes you look like Ernie from Sesame Street, as you can see from your reflection in the window of an empty shop that has a sign saying HAZAL NUTS above the front door, and this shockingly beautiful woman walks past. She is rifling angrily through her big shiny bag with its million extraneous straps, digging away at it with fast little paws like a rabbit, until she pulls out a big roll of smiley face stickers, holds it up to her disgusted, perfect face, and dashes it to the ground. She stalks off. At a party, a man who has been talking to you about diseases stops midsentence and says that he is sorry, he has to leave—he must go and check on Pauline immediately. You assume from the way he says it that Pauline is his cat or his pet snake, but she turns out to be his girlfriend. Pauline! I never really understood before what you were supposed to do with these oddly freighted moments, dense with potentially hilarious significance. Write them down, okay, and then what? Just leave them there? Do they not need to be marshaled in service of some wider narrative about your time in London, or about what you have recently found out regarding diseases? This stuff used to happen and I’d tell myself to write it down, but I wouldn’t. I’d just think, Au revoir, Pauline, you are not a pet, you are a woman—and attempt to retrain my focus on whatever I felt was important. Reading and rereading The Dog of the South has changed that.

What Portis’s novel is actually about, I think, is the exhilaration of noticing, and of keeping a record so that you can look at it later and see what kind of person you are, or were. This is what you picked out, what your attention made special, what you thought was funny, what you found worth slowing down for as you sprinted around in your amazing shoes. The slow accumulation of apparently insignificant detail in The Dog of the South in fact forms the basis of the narrative. Near the beginning, Ray says, “In South Texas I saw three interesting things. The first was a tiny girl, maybe ten years old, driving a 1965 Cadillac. She wasn’t going very fast, because I passed her, but still she was cruising right along, with her head tilted back and her mouth open and her little hands gripping the wheel.” The tiny girl doesn’t reappear, and there is no good reason for her to be there. She doesn’t advance the plot or do anything but cruise on past with her head back. She is intriguing, though, and funny, and therefore indispensable, just like my orange peel incident.

She also tells you something about Ray, who is always on the lookout for signs and portents. In Belize, he sees some men skinning a snake and stops to watch. Not because snakes have any bearing on his pursuit of Norma and Dupree, but because “There, I thought, is something worth watching.” He stores up encounters and people like little rocks and ticket stubs in the bottom of a handbag. Later, he’ll imagine, for instance, what an old man he met back in Arkansas could be up to right now. Maybe he is lying with his pearly shins exposed, watching a hard-hitting documentary on TV. The name KARL is carved into the headboard of one of the motels Ray stays in: “Each time I woke up, I was confused and then I would see that KARL and get my bearings. I would think about Karl for a few minutes. He had thought it a good thing to leave his name there, but, ever wary, not his full name. I wondered if he might be in the next room.” On the alert for chance messages, Ray retains them to use as navigation points whenever he begins to feel lost, or lonely. I do the same thing now: I currently have four notebooks rattling around in my suitcase, full of extraneous details that I could not do without.

My copy of The Dog of the South looks aggressively used nowadays, as if it has been set upon by someone who only half understands what a book is for. I’ve underlined sentences on every page and drawn wiggly lines down the sides of whole paragraphs. Arrows loop all over the place, traveling from blocks of text to a scrawled “LOL.” Though I am on my way to becoming the kind of person who carries a notebook at all times, I occasionally forget, which means there are notes all over this novel that have nothing to do with its contents. There are phone numbers, and an account of a conversation I had with a man who said that he drinks cognac when he has “helicopters inside his mind.” There are reminders to call my mother, or book a ticket, or apologize to someone for being late. There are a number of juice stains from when I became briefly addicted to cherry Capri Sun (disgusting). The book is going to fall to pieces at some stage, and then I will buy another copy to carry around in my bag, and every time I see it I will experience that little shock of recognition and think: “There I am. That’s what I’m like.”

Rosa Lyster is researching a book about the global water crisis.

November 30, 2021

The Fourth Rhyme: On Stephen Sondheim

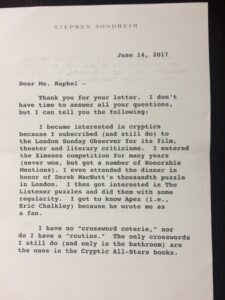

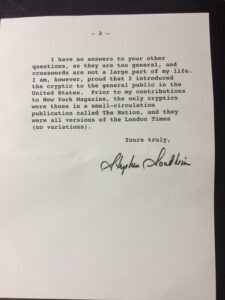

a letter to the author from Stephen Sondheim.

In the late fifties, Stephen Sondheim, who died last week aged ninety-one, performed a song from the not-yet-finished musical Gypsy for Cole Porter, on the piano at the older composer’s apartment. As Sondheim recalls in Finishing the Hat, his mesmerizing and microscopically annotated first collection of lyrics, Porter had recently had both legs amputated, and Ethel Merman, the star of Gypsy—in which Sondheim’s words accompanied music by Jule Styne—had brought the young lyricist along as part of an entourage to cheer him up. Sondheim played the clever trio “Together.” “It may well have been the high point of my lyric-writing life,” he writes, to witness Porter’s “gasp of delight” on hearing a surprise fourth rhyme in a foreign language: “Wherever I go, I know he goes / Wherever I go, I know she goes / No fits, no fights, no feuds, and no egos / Amigos / Together!”

That fourth rhyme–it astonishes every single time–exemplifies everything I revere in Sondheim. He is, of course, a musical-theater god: from West Side Story through Company, Follies, Sunday in the Park with George, and Assassins, his influence trounces superlatives. Even his flops were often revelatory. Merrily We Roll Along proceeds backwards, anticipating by decades the experiments with time in shows like Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years; The Frogs, a reimagining of Aristophanes first performed in Yale University’s swimming pool, must surely have been among the inspirations for Mary Zimmerman’s water-based stage adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Wordplay is never just a pyrotechnic aftereffect in Sondheim’s shows—it’s foundational, crucial to the plot and the characters’ emotional development. And his work continually reminds you that playfulness (in poetry, in music, in lyrics, in visual art) can be most essential when the subject is deadly serious. Sondheim includes a multiple-choice quiz in a love song—“Now/Later/Soon” from A Little Night Music: “(A) I could ravish her / (B) I could nap”—and likewise in a paean to the uses of a gun, sung from the rotating points of view of the actual and would-be assassins of U.S. presidents: “Remove a scoundrel / Unite a party / Preserve the Union / Promote the sales of my book.”

The Sondheim lyrics I love are too abundant to list, but there’s one in his fairytale extravaganza Into the Woods that gets my personal gasp of delight. In the prologue to that show, Sondheim introduces the lyrical and musical motifs of each of the main characters. Full disclosure: I played Rapunzel in my high school’s production; don’t ask me to attempt her high B-flats anymore. Jack’s mother, trying to coax milk from their aging cow, Milky-White, grumbles to Jack that “We’ve no time to sit and dither / While her withers wither with her.” That triple homonym—”withers wither with her”—delights the ear, develops the mother’s character, and moves the plot forward, all at once. (Sondheim’s repetitions are always ingenious: “Then you career from career to career,” he writes in “I’m Still Here,” Carlotta’s torch song from Follies, which my grandmother memorably rewrote to celebrate leaving her job as a middle-school principal—rather an awkward choice for one’s own retirement party, perhaps, but I like to think Sondheim would have understood.) When Jack goes to market and trades the cow, whose meager supply of milk will no longer support them, “for beans”—an idiom that usually means “for nothing”—his mother, a literalist, gets furious again. Jack tells her that these are magic beans, worth far more than their beast, which it turns out they are.

The high point of my own writing life was receiving a typewritten note from Stephen Sondheim. My weakness for that fourth-rhyme effect may be what first drew me to crossword puzzles, so it didn’t surprise me to find out that Sondheim liked them too, but while researching a book on the subject, I learned that he was also a brilliant composer of the cryptic crossword. Crossword lovers tend to remember their first eureka moment with a puzzle: that time they got stumped on a clue, only to realize they’d been seeing it the wrong way. “Strips in a club?” for example, indicates not dancing on a stage but BACON in a sandwich.

Unlike those in American-style crosswords, cryptic clues involve an extra layer of wordplay. In 1968, Sondheim began publishing cryptic crosswords in New York magazine, and wrote about them with reverence: “A good clue can give you all the pleasures of being duped that a mystery story can. It has surface innocence, surprise, the revelation of a concealed meaning, and the catharsis of solution.” He scorned the simpler American variety with equal relish: “The kind familiar to most New Yorkers is a mechanical test of tirelessly esoteric knowledge: ‘Brazilian potter’s wheel,’ ‘East Indian betel nut’ and the like are typical definitions, sending you either to Webster’s New International or to sleep.” I wrote to Sondheim’s agent, asking far too many questions; I edited and re-edited my letter and, after mailing it, spent the night in a cold sweat that I’d used the wrong grammatical tense. When Sondheim, to my astonishment, wrote back, he said that although he no longer had a regular solving practice, he counted introducing American readers to cryptic crosswords among the great achievements of his life. He’d given them a source of delight, a new way of seeing the world.

Crosswords initially appealed to me as a diversion, and I got hooked on them through that gasp of delight, but eventually I realized that they have special resonance in times of crisis. The crossword was invented in 1913, on the eve of World War I, when people craved something comforting in the newspaper. The New York Times first published its crossword during World War II, just after Pearl Harbor, to offer readers a distraction from the bleak headlines. Crosswords also leaped in popularity during the pandemic—I wrote two for The Paris Review in spring 2020—and not only because so many of us needed something to do in isolation. Crosswords provide an experience of immersion, yet they don’t completely shut out the world around you. Wordplay, whether in the best puzzles or in Sondheim musicals, can estrange your surroundings and the language through which you interpret them, allowing your life to catch you by surprise again.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures With Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, What Was It For, and the forthcoming book of poetry Our Dark Academia.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers