The Paris Review's Blog, page 90

February 17, 2022

The Review‘s Review: Ye’s Two Words

A red planet in the foreground with a green planet in the distance, set in a starfield. Image courtesy of Adobe Stock.

In the wee hours of this morning, Ye shared a flurry of Instagram posts. There were videos advertising his proprietary Stem Player, which he claims will be the only place fans can listen to DONDA 2, the album he plans to release next week. “Go to stemplayer.com to be a part of the revolution,” he wrote. The Stem Player, which allows users to remix music by manipulating stems, or the individual, elemental parts of a song, is a disc covered with what looks like semitranslucent tan silicone, featuring blinking multicolored lights that correspond to the tempo and other aspects of a currently playing track. Its design is of a piece with Ye’s Yeezy aesthetic: earth tones complemented by bright hues, like a Star Wars scene set in Tatooine. His posts recall George Lucas’s series in their narrative messaging as well: Ye highlights the battle between an evil empire—in this case, the music and tech industries—and an intrepid revolutionary, himself. “After 10 albums after being under 10 contracts,” Ye explains, he is ready to control the means of distribution. “I turned down a hundred million dollar Apple deal. No one can pay me to be disrespected. We set our own price for our art. Tech companies made music practically free so if you don’t do merch sneakers and tours you don’t eat … I run this company 100% I don’t have to ask for permission … I feel like how I felt in the first episode of the documentary.”

“The documentary” is jeen-yuhs: a Kanye Trilogy, a nearly five-hour bildungsroman that premiered at Sundance in January and is distributed by Netflix. Directed by the filmmakers Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah, who made Ye’s first music videos, jeen-yuhs is shot in what appears to be vibrantly colored 8 mm—something of Coodie & Chike’s trademark—and is narrated by Simmons, who quit his job as a comedian and public-access host in Chicago to follow his friend’s journey. It’s a culmination of over twenty years of documentation and hundreds of hours of footage. Consequently, the film plays like a very long, intimate home video.

In the trilogy’s first part, which premiered on February 16, it’s the early aughts: Ye is hustling in New York City and working on what will become his 2004 album, The College Dropout. This is the portrait of an artist as a twentysomething young producer, a successful beat maker struggling to be taken seriously as a rapper. He goes into Roc-A-Fella’s offices and plays his music for busy A&R and marketing professionals, who half listen in between phone calls. We see him playing his instrumentals for other rappers, driving around New York delivering tracks, taxiing through the city with CDs of beats, waiting for his career to take off. We see him waiting in the wings of another rapper’s concert anticipating his chance to get on the mic, and then buying a porn mag from a newsstand. We see the empty refrigerator in his Newark bachelor pad. We see him spending time with his mother, the late Dr. Donda West, in her Chicago apartment. Dr. West’s confidence in her son’s abilities is touching; while watching Ye and his mom rapping one of his early songs in her kitchen one late night, I had to wipe my eyes. In this film, we see Ye built bit by bit; we see his stems.

One of today’s predawn posts was an excerpt of a track called “Fuck Flowers”: a video of the Stem Player playing the song in the dark, its blinking nodes like a pulsing beacon cast from a lighthouse, beckoning insomniacs, those in other time zones, and workaholics to come and listen. The device’s undulating light show matches the rhythm of Ye’s recent Instagram activity, which has functioned as a rapidly changing post-and-delete diary of his thoughts. For the past few weeks, he’s been sharing dozens of posts, which vacillate between harassing his estranged wife, Kim Kardashian, and her boyfriend, Pete Davidson; promoting his new album; and expressing a desire to restore his marriage. Beginning with 2016’s The Life of Pablo, an album notorious for its ever-evolving tracklist and sequencing, Ye has been editing his art to fit his moods. At the same time as he started live-editing his art, he began live-tweeting his thoughts. In 2018, for example, he ecstatically expressed his ideas about Donald Trump’s “dragon energy,” and his emoji skin-color preferences. Ye’s impulse to share has only intensified. On Sunday, he wrote, and subsequently deleted,

HERE’S SOMETHING I HAVE TO DISPEL MEANING REMOVE THE SPELL THAT PEOPLE ARE UNDER WHY DOES A MEDIA OUTLET GET TO POST 20 TIMES A DAY BUT IF I POST THAT AMOUNT THERE’S SOMETHING WRONG ISN’T INSTAGRAM OUR OWN PERSONAL MEDIA PLATFORM? … I LOVE BEING IN CONTROL OF MY OWN NARRATIVE “I FEEL KIND OF FREEEEEE”

The contrast between Ye’s impetuous Instagram dispatches and the thoughtfully arranged, two-decades-in-the-making jeen-yuhs is a fruitful artistic juxtaposition: between a hastily assembled chronicle and a more reflective composition. We can see two chronologies in motion, two contradictory but complementary records in play, suggesting distinct, but overlapping destinies—hinting, like Tatooine’s binary sunset, at elliptical experiential timelines. Holding the two together means witnessing a pleasant anachronism, as sweet as Ye’s old sped-up soul samples. “We get a good juxtaposition now in this film between the two lenses,” says Chike Ozah, referring to balancing the media’s critical view of Ye with a more empathetic one, in an interview with Netflix. On the College Dropout classic “Two Words,” Ye plays with the power of contrasting pairs: it features Freeway, who was then a hard-core street rapper, and Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey), the Toni Morrison–quoting indie-rap darling. Throughout the song, the featured artists use the refrain “two words” before juxtaposing sets of images. Ye begins his verse by establishing the scope of his playground—“Southside, worldwide”—which is both local and cosmopolitan. In light of the duality offered by his social-media narrative and the documentary—a long view alongside a short one—I wonder what words he’d use to describe himself now. For me, two words come to mind: recording artist.

In one jeen-yuhs scene, filmed with Ye and Dr. West at his childhood home, the musician says, pointing at the space where a full-length mirror used to be, “I used to just practice in front of it.” It’s not hard to imagine; in several scenes, Ye flexes for the camera, posing and preening. Oh, how things have changed. For Ye, these days, mugging in front of the camera is like mugging in front of a mirror. At the beginning of the film, a Roc-A-Fella A&R rep asks him, “You still doing your documentary? I thought it’d be finished.” Ye replies, “It’ll never be finished.” —Niela Orr

I knew that Joachim Trier counted Arnaud Desplechin’s 1996 film My Sex Life … or How I Got into an Argument as an influence—he said as much at a recent talk at Lincoln Center—but was delighted by just how deeply Trier’s new movie, The Worst Person in the World, reminded me of the former when I finally saw it last week. The Worst Person in the World, like My Sex Life, is a freewheeling exploration of one’s early thirties—that delicate age at which actions do indeed begin to have consequences but it’s still fun to occasionally blow up one’s life in a moment of boredom. From the voiceover to the adultery plot points to the menstrual-blood shower scene, Trier borrows freely from Desplechin, though he swaps the gender of his main character, Julie. The result is a witty, realistic look at the highs and lows of finally growing up, and might include the best sex scene I’ve ever seen—it’s certainly the best sex scene in which the characters don’t even touch each other. —Rhian Sasseen

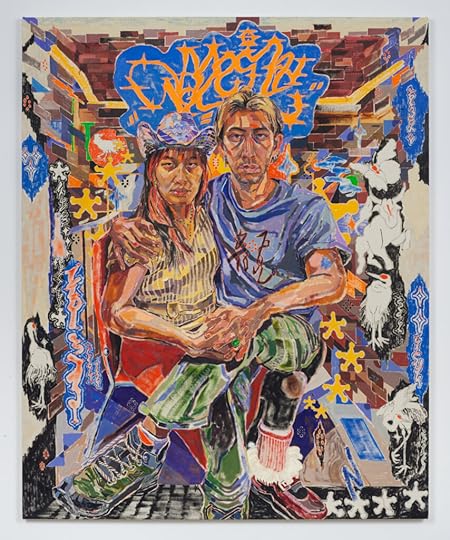

I first encountered the work of Oscar yi Hou—now an upcoming solo exhibitionist at the Brooklyn Museum after winning their third annual UOVO Prize—when I saw his A sky-licker relation at James Fuentes Gallery late last summer. The exhibition is a series of portraits, mainly of young Asian people. The subjects, through their various positions of vulnerability, stoicism, solitary ponderance, and mutual affection, stare directly out of intricate, kaleidoscopic frames to meet the eyes of their audience, positioning the viewer such that they take up the gaze that was once held and reciprocated by the artist. This dynamic between creation, creator, and beholder is simultaneously mediated and immediate, spontaneous and reenacted—an experience that is communal but also intensely concerned with the individuality of personhood. Seeing yi Hou’s work amidst a crowd of other twentysomethings fresh into the gallery from a day that had been hot and damp, hopelessly sweating through an outfit I had probably chosen with great effort for the occasion, I was faced with exactly that: the discomfort, the relief, the multiplicity and solitude of the person.

With me at the exhibition were several people who had modeled for the paintings. I saw them as they existed both in the real world and within the complex iconography in which the artist had immersed them: the dragon, horse, and ox of the lunar calendar; ornate lettering reminiscent at once of ancient calligraphic practices and contemporary American street graffiti; golden stars denoting the Chinese flag as much as the classic westerns of old Hollywood. Graceful and precise, these aesthetic references index their subjects as global intersections of past and present, living fulcrums upon which a multitude of dreams and inheritances—fame, beauty, nationhood, belonging—have come through time to balance. Standing before their portraits, sharing with them my reality and the collisions of perspective inherent to it, I felt that transhistorical identity reflected within myself. —Owen Park

Far Eastsiders, aka: Cowgirl Mama A.B & Son Wukong, 2021, signed and dated verso, oils on canvas, 61 x 49 3/8″. Photo by Jason Mandella, courtesy of Oscar yi Hou and James Fuentes.

Don’t Delete: A Visit with Billy Sullivan

Billy Sullivan’s studio. Photograph by Lauren Kane.

Billy Sullivan’s studio, a fifth-floor walk-up on the Bowery, has a comfortable, elegant dishevelment. Hanging all around the space are some of the brightly colored figurative paintings he has been making since the seventies: portraits of his friends, lovers, and other long-term muses, rendered in loose, dynamic brushstrokes and from close, pointedly subjective angles. A still life of a bouquet and two coffee cups is an outlier among the faces. Near a work in progress on the wall is a table with a color-coded array of pastels, each wrapped in its paper label (mostly the artisan Diane Townsend, with a few older sticks from the French brand Sennelier); a metal cart bears tubes of oil paint, and reels of film negatives are tucked away on low shelves. Tacked up on a set of folding screens is a display of Sullivan’s photographs and sketches, and next to that is a burgundy chaise longue adorned with a faux animal pelt. When I visited on an overcast afternoon in December, Sullivan had set out a bowl with grapes and a fig on the kitchen island, where he pulled an espresso for himself and poured a glass of water for me.

I had brought along a copy of Gary Indiana’s 2003 novel Do Everything in the Dark, a contemporary answer to George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which follows a tight-knit group of artistic New Yorkers who, over the years, have either realized or surrendered their potential for happiness. As Indiana explains in an Art of Fiction interview in the Winter 2021 issue of the Review, the novel began as a series of vignettes intended to accompany Sullivan’s paintings of people they both knew in the “downtown” scene. We looked through images together, and Sullivan told me some of the stories behind them. That milieu—Cookie Mueller was a part of it, as were Andy Warhol, Jackie Curtis, and the FUN Gallery founder Patti Astor—flourished for only a few years, from the late seventies through the tragic onset of the AIDS epidemic, and is often fetishized, much to Indiana’s irritation. The very word downtown carries a whiff of romance, especially when spoken by those too young to have known an era when you could live in Lower Manhattan on next to nothing. “There was a lot more free time,” as Sullivan puts it, and to be an artist essentially meant that “you got respect from your peers and you hung out with people you really liked.”

Sullivan is mild-mannered and considers himself a wallflower, an observer. While we sat and talked, he kept lifting his phone to take quick images of me as I fidgeted, recrossing my legs or tying up my hair. His photographs—he calls them his sketchbooks—have a loose, spontaneous quality, conveying an intimacy that invites the viewer in. The second time I referred to them as “candid,” he corrected me. For Sullivan, there is no distinction to be made between a candid photograph and any other kind.

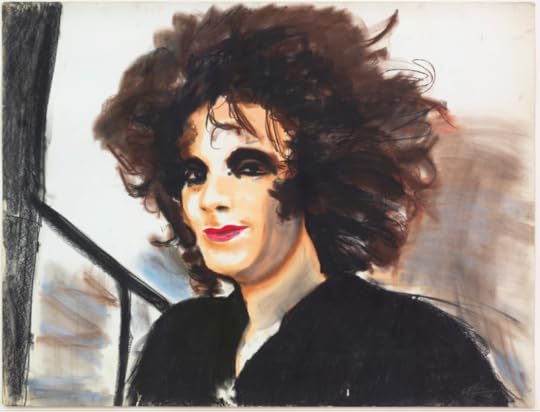

Gary, 1997, pastel on paper, 42 x 30″. All images copyright Billy Sullivan. Courtesy of the artist and Kaufmann Repetto, New York and Milan.

Gary was always around at night. I was interested in the way he wrote—dynamite art criticism. His writing was sort of like poetry. We ran pretty much in the same places at the same time. I’d see him when I went to the barber, and we’d go to the same restaurants, too, like Mickey Ruskin’s at One U. Places where you could go and get food and it didn’t cost anything. One U took the place of the back of Max’s Kansas City, where it first started for me. You would go to One U at around ten o’clock. Everyone would show up there, and you would play around. And then there was the Mudd Club. Gary would go. It was what you did at night. And it would be whoever was interesting. We never thought of it as the underground. It was just the world, and everyone was hanging out. You wouldn’t call somebody and say, “Are you going?” You would just show up.

You didn’t want to use the phone. There was all this paranoia because we were anti-war, we were anti all these things. And the older people, like Brice Marden and those guys, they would be really frightened of the FBI.

Gary became a muse for a while. We became friends over a long period of time, and it was always interesting—something was always going crazy in his life, and you got to hear that. We would have these long telephone conversations, kind of piecing together what happened the night before. In the morning you would check in and see when you left somewhere and what you did. It used to be a whole part of my life was, the next day, trying to figure out what exactly happened.

Cookie’s Secret #1, 1983, pastel on paper, 62.5 x 42″.

Cookie Mueller had a place on Bleecker Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues. And you’d go there, like before you’d go out at night, and get whatever you needed. Lots of times you went to Cookie’s to get drugs and get ready to go out. She’d be putting on her clothes.

Cookie called me a diarist. She used to work for some place called Details, and she wrote that in a review in there. And I liked it. It sounded like what it is. This is my diary.

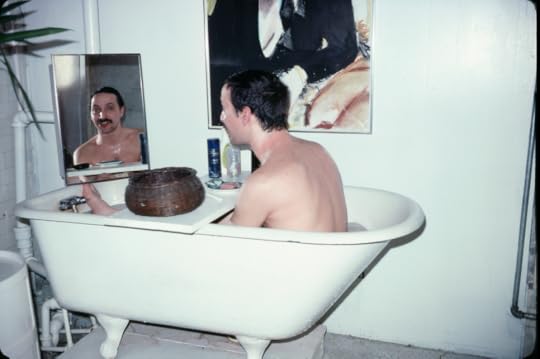

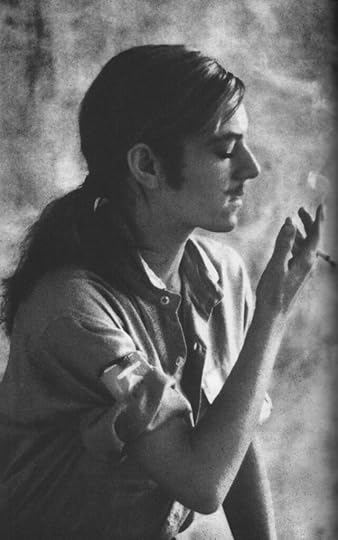

Frank, April 1977, 1977 (printed 2017), digital c-print, 16 x 24″.

I get to go to lots of people’s bathrooms. That’s just, I’m friendly.

Anne, March 1985.

This is Anne, my husband Klaus Kertess’s best friend. She was a beard when we would travel sometimes. They were opening the Morgan Hotel, and she was doing a big party. And that’s the first bathroom at the Morgan. That’s her drinking her wine, talking on the phone, her favorite thing. Now she just texts.

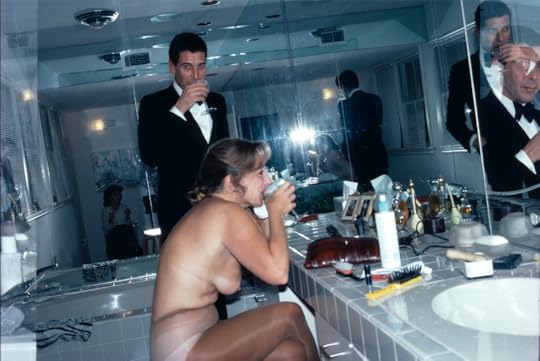

Anne and Klaus, 1981 (printed 2002), digital c-print, 13.5 x 20.25″.

That’s Anne in the bathroom in Fort Worth. They were getting ready to go to a big party at the Bass Hall, and Klaus was doing an art show then, for Laura Carpenter. They’re having margaritas before we went out. When we got to parties in Fort Worth, Anne would give everybody an individual vial of cocaine so that we wouldn’t go into the bathrooms together, because she’d get in trouble.

Michael and Naomi, 1971, 1971 (printed 2011), digital c-print, 30 x 20″.

Naomi Sims was the first really big Black Halston model. She was married to Michael Findlay, who is an art dealer. And she came to my house on Eighty-Seventh Street, all decked out in the Halston, just to have dinner, and to drink and have a good time. She was the most elegant woman ever.

Eileen, 1998, oil on linen, 30 x 20″.

I’m good at red. I got interested in them because they hung out with Jimmy Schuyler, and I always thought he was the most brilliant poet. I’d see him at Fairfield Porter’s house in Southampton, and he must have been on Thorazine or something. He’d just be sitting there like that, but still brilliant.

Patti Astor, 1979, pastel on paper, 42 x 46″.

Patti Astor had a place in the East Village. One day we went over there, and you had to bring her a bottle of vodka. She had great makeup. She was something else. She was one of the beginnings of the East Village—she pulled all that together. This is in her home at like one o’clock in the afternoon. You know, the mattress on the floor with some pillows and Marlboros and ashtrays …

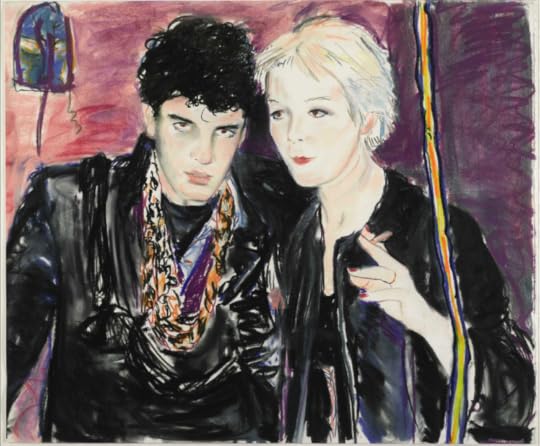

Louie and Patti, 1979, pastel on paper, 30.25 x 39″.

And that’s Louie Chaban. He was going out with Rene Ricard, then, that’s how I met him. Louie was once the doorman at the Mudd Club, and then when Soho started having fashion as well as art stores, he worked for Anna Sui. I’d go visit him when I was looking at art there, and we would take pictures, and we’d go out at night. I can be fascinated by somebody, totally involved in that person, and I can spend years doing it. Louie is somebody who I’ve done from when he had a twenty-six-inch waist until … He’s this big, huge, grumpy man now.

Gary and Cookie, 1981, ink on paper.

Gary and Cookie again. They were perfect together at night. They just had this whole conversation going. She seemed like she was always kind of whispering in someone’s ear. I’ve never seen Gary be really loud, and I don’t think Cookie had to be loud. She could get anything she wanted just being Cookie.

Jackie Curtis, 1971, pastel and watercolor on paper, 35 x 46″.

Jackie Curtis and I were in high school together. I didn’t know that until she told me later. My studio was on Eighty-Seventh Street, I had a spiral staircase. She came over and we started playing around. She was trying to get some money to make a movie. I worked on plays that she was in, too—I did sets for Andy Warhol. This is from around the same time as that great portrait by Alice Neel of her and Ritta Redd. Ritta Redd was there the same night, and Andrea Whips and Warhol were with us. It was a total Factory thing.

Stephen Hall #1, 1972, pastel on paper, 35 x 26″.

He was a boyfriend of Rene Ricard’s. He got undressed that day. It was really nice.

Klaus, Nan, Cookie, and Louie, March 1980.

I never really paid attention to my photographs, because I just used them for reference. Some of them have become drawings and paintings. I could take a picture in 1979 or 1980, and I could make a painting in 2004 of that image—I can go right back and be there.

I never knew they were sketchbooks until somebody was doing a book about me. What they wanted were my photographs. And then I started noticing that they’re relevant, that they really mean something. They lock a time and a place, and puts me somewhere. They block time, so I don’t have to think about time. All I have to do is remember to organize my images. I tell kids now, “Don’t delete your images, because images that you delete today, one day will really look good.” Sometimes you can’t see what things look like until time passes. It’s like if you write for a living. You’ll write something one day. The next day, you’ll look at it. You don’t think it’s any good. And then a week later, it really makes sense, what you wrote. And that’s the same thing with images.

I used to love it when it was film in cameras, because you didn’t see anything. The film had to go away, and then it had to come back, and then you’d look at it. This time period that it took, it was kind of like sobering up—“Oh, this is what it was.”

Lauren Kane is an editor at The Paris Review.

Hunger Moon

In her monthly column, The Moon in Full , Nina MacLaughlin illuminates humanity’s long-standing lunar fascination. Each installment is published in advance of the full moon.

The Large Figure Paintings, No. 5, Group 3, Hilma af Klint, 1907. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I

In a driveway in San Jose, California, faded winter sun shone off the waxy tongues of the biggest jade plant I’d ever seen. The person I was with, whose mother’s heart had stopped four days before, unloaded things from a rental car. His stepfather, who I’d been warned was “a strange man,” pulled in behind us, back from collecting his wife’s ashes. He walked over with a cardboard box, anonymous and regular as any box you’d see on a doorstep, and stood by his stepson, holding this box. The man hefted the box in his hands and said, in a tone I cannot describe as anything other than merry, “You wouldn’t believe how much your mom weighs stripped of water and bodily liquid.” Something exited the person I was with, as though his bones had changed density, and he leaned back into the trunk of the car. The stepfather started to speak again—“Or fluid is the word, isn’t it, bodily fluid, blood and …”—and I moved toward him, opened the door to the kitchen, and held it for him. “Here,” I said, and he walked through it and the door swung closed and through the plexiglass I watched him place the box on the kitchen table, next to a bowl of persimmons and a bouquet of white carnations neighbors had sent in sympathy.

The next day, a boat took us out to sea from the San Francisco Bay. The captain cut the engine, the boat rocked in the waves, and the stepfather dropped the ashes, held in a dissolvable vessel designed for such ceremonies, into the Pacific Ocean. Shaped like a small flying saucer, with a sunset scene painted on top, the vessel bobbed. The woman’s grandchildren threw clippings from her beautifully tended garden. Sprigs of sage, roses, and six lemons from her lemon tree. “It’s sinking,” someone said of the vessel. “It’s designed to,” said someone else. Soon it was swallowed, absorbed into the deepest deep. And sooner than anyone expected, the motor churned, the boat lurched back into motion. Our small group stood at the bow and watched the garden matter recede, tumbling in the wake. The lemons, buoyant, bobbed and dipped on the dark surface of the sea.

II

The root of a tooth cracked and had to be extracted. On a sunny midwinter morning, a strong doctor used her strength to remove the tooth farthest back in my lower left jaw. It was unpleasant. Injected and well numbed, the left half of my face was a cementy nonpart of me. I couldn’t feel it but I knew it was there. The doctor put a piece of rubber between my teeth, the texture of a hockey puck, and began to do her work. Her assistant stood behind the chair, held my forehead, and offered encouragement. “Keep breathing.” “You’re doing great.” I could feel the flex of the doctor’s flank against my shoulder. Before closing my eyes, I watched a vein swell at her temple. Nothing hurt, but I did not like the sounds, nor the visible strain required of the doctor. At some point, my mind told me: Your jaw is going to break. “You’re almost there,” said the lady behind me with her palm on my forehead. “Okay, slow your breath.” My jaw is going to break. “Deep breaths now.” My mouth was full of fingers and wrenches and post-hole diggers and crowbars. Naturally, I could not speak my concern out loud. “You need to breathe slower.” My jaw. “Okay now, easy, easy, we’re almost there.” “It doesn’t want to come,” the doctor said, quietly, sounding baffled and vexed. The lady put her other hand on my shoulder. Shallow, frantic breaths. “Deep, slow breaths now, you’ve got to slow your breaths.” And then I heard myself cry out, a high-pitched yelp, involuntary. And in that moment, the doctor said, “It’s out, it’s out, we got it, it’s out.” I dissolved into the chair. The room spun. “Do you want to see?” she asked. Dizzy, sweating, high off the chemicals my body had delivered to my bloodstream, I nodded, and she held out a wad of gauze on her open palm, my tooth as big as an acorn, long tendrils of bloody root. I might’ve been hallucinating.

Ten days later I returned, with more of my wits about me, to have the healing process assessed. “You mentioned bone matter,” I said. A piece of bone matter had been crammed into the socket where my tooth had been, into which a small titanium rod would be inserted, onto which a new fake tooth would be attached. “Bone matter?” I said. “Yes,” the doctor said. “Cadaver bone,” she said. Ghost bone in my face. “In time,” she explained, “your own bone will absorb the cadaver bone, and in time, it will become entirely your bone.” I expressed my amazement. “The body is in a constant state of destruction and creation,” the doctor said. “The body will always try to move toward equilibrium.” Ghost bone in my skull becomes my own bone. Absorbed and altered, destroyed and created, equilibrated, chew and swallow.

III

The biggest argument I’ve ever witnessed was about whether men had landed on the moon. Some years ago, at dinner—paella and wine—a chemist with a Ph.D. from Stanford suggested that the moon landing had been a hoax. This did not go over well with his father-in-law at the head of the table. At first I didn’t understand what I was hearing—I didn’t know then how many people believe the moon landing to be a fiction. Soon the men were roaring, the chemist’s brother-in-law got involved: “Of all the boneheaded bullshit to come pouring out of your face …” “Well, how do you explain …” Threats were flung, neck veins swelling, a hand slammed on the table, a knife clattered to the floor. We joked about it recently, the brother-in-law and I, recalling the scene, eating pasta with clams and garlic, and he asked me, “You’ve read the Apollo 11 eulogy speech, right?” I hadn’t. “Read it,” he said.

On a windy night not long ago, I did. William Safire wrote the speech in 1969, for Richard Nixon to deliver in the event that the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded on the moon and left there to die. The speech, never spoken, was slotted into archives and forgotten. Thirty years later, the brown-edged, typewritten memo was unearthed. Safire explained to NBC that Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong, marooned on the moon, would have had two options: starve to death or kill themselves. The speech would have been delivered not after they’d died but as soon as it was determined that there was no way to get them back. The speech is 233 words long. It troubled me.

It begins: “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.” Fate has ordained. (Not: We got the math wrong.)

The Fates are three sisters: one who spins the thread of mortal destiny; one who dispenses it; one who snips the thread and kills us dead. Blaming fate—already I was rubbed wrong. But more unsettling by far was the thought I’ve still not shaken, of two people up there dying. “The moon is your moon & my moon & it is here, full in the night sky,” the poet Laressa Dickey writes. “Here I am. Stones nearby.” It is your moon and my moon, full tonight, look, and here we are, all of us, we’re all down here, the stones nearby. To see the moon and know two men were up there stranded on its surface? It would be a changed moon, a ghost moon.

I was so troubled reading the speech, I went outside for a night walk. Wind and clouds. No moon.

I imagined the men, hungry, gaunt, shadows deepening in the craters of their eyes, getting thinner, getting weaker, and one night lying down together, maybe holding hands in their big gloves, their lives leaving them. And I imagined the abrasive moondust chewing through their big moon suits, then the flesh of them, so they were bones on the surface of the moon, and I imagined the moon swallowing the bones into itself, as the desert sand absorbs a snakeskin. Their helmets left as headstones. Their bones absorbed into the bone of the moon, until they were made moon themselves.

What’s the moon made of? In the West we say green cheese, but according to ancient Hindu texts, it’s a vessel that holds soma, a nectar that grants immortality. Maybe that is what the men would have been absorbed into, a great bath of vision-giving elixir. Anthropologists, biologists, and medical historians have tried to figure out what plant soma is made of. Ephedra, ginseng, lotus, cannabis, sugarcane, the mushroom Psilocybe cubensis. Theories abound. Do we need to know? In the Apollo 11 speech, Safire writes of “mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.” What did we find? What did we lose? The untranslatable, the mystery, the shadowed space of not knowing.

“We drank soma, we became immortal, we came to the light, we found gods,” the Rig-Veda says.

We found gods. We’d been searching for them everywhere.

“In ancient days,” Safire writes, “men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.” As I walked that night, I kept hoping the clouds would part, that the moon would reveal itself. The men would have become the moon, I thought as I walked. And maybe this is immortality. To become the moon! Except that here, on earth, we’re absorbed in various ways, too: by fire into ash, into the soil, into the sea. Are we thus offered immortality? It’s always seemed the opposite to me. Our bones are absorbed into the mouth of the earth, making us earth. Here I am, stones nearby.

Following the short speech, Safire writes, “after the President’s statement, at the point when NASA ends communications with the men”—adios boys, you’re on your own out there, godspeed; snip, thread cut, and not by sister Fate—“a clergyman should adopt the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to ‘the deepest of the deep.’”

Off they would’ve gone. And off we’ll go. Off we’re going, on the search, our noble goal, looking until we cannot look, vessels on the surface, tugged toward what shines and spins until we are pulled out, unrooted, taken up into it, finally and forever, unstill as light.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice. Her previous columns for the Daily are Winter Solstice, Sky Gazing, Summer Solstice, Senses of Dawn, and Novemberance.

February 15, 2022

Redux: Couples at Work

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Working at his place in the afternoon, and other notes from the archive on writing and romance.

If you enjoy these free interviews, and the portfolio, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

Jane and Michael Stern, The Art of Nonfiction No. 8

Issue no. 215 (Winter 2015)

INTERVIEWER

When you started writing about road food, did you think it was of a piece with the folkways movement that was going on then?

MICHAEL STERN

If we didn’t at the start, we very quickly did. The year after Roadfood was published, we published Amazing America. And in Amazing America there are lots of folk-art environments and stuff like that. I think when we absolutely started, when Roadfood was called Truck Stoppin’, we weren’t thinking that it had anything to do with pop culture or folk art, but as soon as we got on the road and started finding guys like Howard Finster and that guy in Wisconsin—

JANE STERN

—the guy who collected—

JANE AND MICHAEL STERN

—the oil rags—

MICHAEL STERN

—not only did we very quickly realize that that was our passion, but I think it really helped us, in some way, to get a perspective on the food we were writing about. It wasn’t just truck-stop food. It was food that was a cultural phenomenon as well.

INTERVIEWER

And that led to Roadfood?

JANE STERN

Well, in doing that, we were eating in all these road-food places, which didn’t have a name then. There wasn’t the concept of “road food”—there were just these little mom-and-pop cafés, and we kept a little notebook of these places. So after the trucker book came out, and did very well, there came the usual publisher question of what was next. And I said, I think we should do a book called Truck Stoppin’, and I remember the editor said, What’s that? And I said, Places truckers eat. So we got a contract to do that. Then our grand idea was to review every restaurant in America, which seemed like a really easy thing to do, considering neither of us had ever been anywhere. Michael had been to Chicago, and I had been to New Haven! We just opened a Rand McNally map, and said, Piece of cake. Three years later, we were still on the road finding these places. We were so sloppy. The main thing is that we wanted to be together.

Interview

Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, The Art of Translation No. 4

Issue no. 213 (Summer 2015)

INTERVIEWER

Richard, you once wrote that rumors of your ignorance of Russian are somewhat exaggerated. What is the actual state of your Russian?

PEVEAR

I can’t really speak Russian. But I can hear it, and I understand quite a lot. I look at the text all the time as I translate. I don’t just use Larissa’s translated manuscript. She even sometimes gets very angry. She says, Where did you get that? You must have looked in the dictionary!

VOLOKHONSKY

Richard has something better than the knowledge of Russian. He has intuition and literary style.

INTERVIEWER

When your first draft goes to Richard, what does it look like? Is it close to what it might become?

VOLOKHONSKY

You mean, how bad is it? How bad is it, Richard? Tell me.

PEVEAR

She makes it as bad as possible so that I have something to do.

Interview

Simone de Beauvoir, The Art of Fiction No. 35

Issue no. 34 (Spring–Summer 1965)

INTERVIEWER

People say that you have great self-discipline and that you never let a day go by without working. At what time do you start?

DE BEAUVOIR

I’m always in a hurry to get going, though in general I dislike starting the day. I first have tea and then, at about ten o’clock, I get under way and work until one. Then I see my friends and after that, at five o’clock, I go back to work and continue until nine. I have no difficulty in picking up the thread in the afternoon. When you leave, I’ll read the paper or perhaps go shopping. Most often it’s a pleasure to work.

INTERVIEWER

When do you see Sartre?

DE BEAUVOIR

Every evening and often at lunchtime. I generally work at his place in the afternoon.

INTERVIEWER

Doesn’t it bother you to go from one apartment to another?

DE BEAUVOIR

No. Since I don’t write scholarly books, I take all my papers with me and it works out very well.

Art

Couples

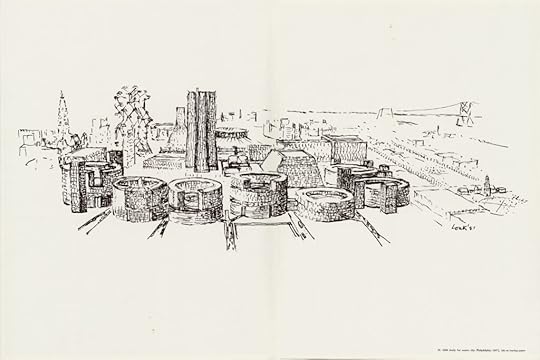

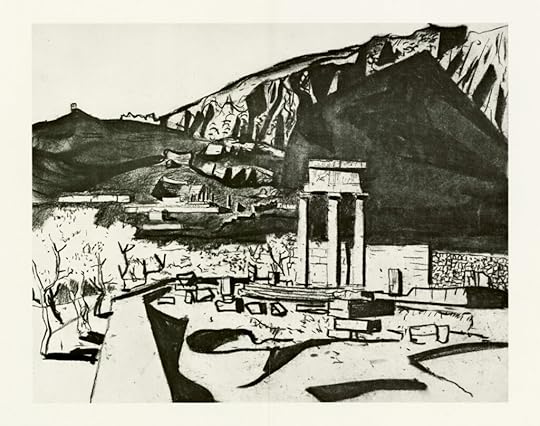

By Eric Fischl

Issue no. 86 (Winter 1982)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

February 14, 2022

Sephora on the Champs-Élysées

Illustration by Matthew Fox (@matteo_zorro).

New Recruits

The vast office in which the group of Black men find themselves is open-plan. No walls interrupt the space separating them from the glass cage emblazoned with the three letters—CEO—that mark the territory of the alpha male. A huge picture window generously affords a view over the rooftops of Paris. Forms are handed out, left, right, and center. Here, they are recruiting: recruiting security guards. Project-75 has just been granted several major security contracts for a variety of commercial properties in the Paris area. They have an urgent need for massive manpower. Word spread quickly through the African “community”: Congolese, Ivorian, Malians, Guineans, Beninese, Senegalese.

Everyone takes out the various papers required for the interview: the identity card, the traditional résumé, and the CQP, a kind of official permit to work in security. Here, it is portentously dubbed a diploma. Then there is the cover letter: “To Whom it May Concern,” “part of a dynamic team,” “a profession with excellent career prospects,” “in keeping with my skills and training,” “please be assured,” et cetera. In a place like this, the medieval circumlocutions and ass-kissing phrases of motivational letters become risible. After all, everyone in the room has a powerful motivation, though what it is may be very different depending upon which side of the glass one finds oneself on. For the alpha male in his glass cage, it is maximum turnover. Hiring as many people as possible is part of the means. For the Black procession outside, it is an escape from unemployment or a zero-hour contract by any means necessary. Security guard is one of those means. The training is absolutely minimal, employers are all too willing to overlook immigration status, the morphological profile is supposedly appropriate: Black men are heavyset, Black men are tall, Black men are strong, Black men are deferential, Black men are scary. It is impossible not to think of this jumble of noble-savage clichés that is atavistically lurking in the mind of every white man responsible for recruitment, and in the mind of every Black man who has come to use these clichés to his advantage. But that is not at issue this morning. No one cares. And, besides, there are Black men on the recruiting team. Everyone fills out his form with a modicum of diligence. Last name, first name, sex, date and place of birth, marital status, Social Security number: this will be the most demanding intellectual challenge of the morning. Even so, a few of the men glance at their neighbors’ forms. Someone coming out of a long period of unemployment lacks self-assurance.

After signing and initialing a few white pages blackened with esoteric phrases, every member of the group is given a bag containing a pair of black trousers, a black jacket, a black tie, a shirt that may be white or black, and a monthly work roster indicating the times and places of shifts. Those who already have experience in the profession know what lies in store in the coming days: spending all day standing in a shop, until the end of the month comes and they are paid. Paid to stand—and it is not as easy as it might seem. In order to survive in this job, to avoid lapsing into cozy idleness or, on the other hand, fatuous zeal and bitter aggression, requires either knowing how to empty your mind of every thought higher than instinct and spinal reflex or cultivating a very engrossing inner life. The incorrigible-cretin option is also highly prized. Each to his own method. Each to his own goals. Every man who comes into these offices unemployed leaves a security guard.

Vocabulary

In the Ivorian community in France, the security guard is such a ubiquitous profession that it has spawned a terminology, one inflected with the colorful expressions of Nouchi, the popular slang of Abidjan.

Standing-Heavy: designates all professions that require the employee to remain standing in order to earn a pittance.

Zagoli: specifically refers to the security guard. Zagoli Golié was a famous goalkeeper with Les Éléphants, the national team of Côte d’Ivoire. Being a security guard is like being a goalie: you stand there watching everyone else play and, once in a while, you dive to catch the ball.

MIB

At the branch of Sephora on the Champs-Élysées, the security guard wears a black jacket, black trousers, black shirt, black tie. He works his shift with four other Men in Black and a supervisor who sits behind a bank of monitors surveying footage from the forty cameras bristling around the boutique. He has a walkie-talkie connected to a transparent earpiece. A swanky guard for a swanky avenue.

“Sephoraaa” or “Sephoooora”

This Sephora is one of the largest in the world. As people step inside, or sometimes simply as they’re walking past, they often shriek as though they’ve just spotted an old friend they are about to run to and embrace: “Sephoraaa!” (version française); “Oh my God! Sephoooora!” (English version).

The Prairie

The Sephora store is long and narrow, and the black-and-white-striped pillars are reminiscent of a basketball umpire. To the right, color-coded orange: Men’s Fragrances. To the left, color-coded pink: Women’s Fragrances. To the rear, color-coded green: Face and Body Care. This zone is nicknamed the Prairie, as much for its color as for the luxury Swiss skincare brand La Prairie, which sells the most expensive item in the store: a “caviar cream” that costs nine hundred euros for a hundred milliliters.

Sense(s)

In the perfume aisles, soft lighting is deployed to heighten the sense of smell. In the makeup aisles, harsh lighting is deployed to heighten the sense of vision. Everywhere, Muzak is deployed to heighten the sense of deafness.

The Shoe Carrier

A young Japanese man enters with a Prada bag slung over his shoulder and, in one hand, dangling from a carabiner, a plastic gadget on which hangs a pair of visibly worn sneakers: this is a Zpurs shoe carrier. The man is currently wearing a pair of blue sandals, and the security guard imagines him performing a quick-change when it starts to rain, shrieking “Banzai!” When we do not understand the Other, we invent it, usually with racist clichés.

J( n+1 )

The MIBs at Sephora communicate with one other via earpieces, tracking suspects or supposed shoplifters according to their morphotype using codes that conform to a numerical sequence with the formula J(n+1), in which n is an integer.

J3: Arab.

J4: Negroid.

J5: Caucasian.

J6: Asian.

The security guard does not dare ask what call signs should be used for persons of mixed race. J4/5 mixed Black and Caucasian? J3/6 Arabo-Asian? J6/4 Black Asian… Given its high rate of interracial marriages, the security guard cannot help but think that in Brazil, his counterparts must have a much more complex formula.

The Emir’s Wife

Cloaked, from head to toe, in a black veil, her every step reveals a glimpse of a patent leather stiletto and an ankle encircled by the cuff of a pair of jeans that, one imagines, tightly hugs the rest of the leg. She is accompanied by a servant, an aide, and a bodyguard. They are easily recognizable. The servant, a young Filipina woman with a particularly pimply face, is carrying bags from every luxury emporium from the Place Vendôme to the Champs-Élysées. The aide, a rather effeminate Arab man, has the Woman in Black’s handbag tucked under his arm and holds her credit card conspicuously, between his index and middle fingers. The bodyguard is the man carrying three umbrellas who trails meekly after them.

Americanophiles

An Arab couple. The husband wears a T-shirt printed with a map of the New York subway. The wife, in full veil, is wearing a grey boubou with sleeves stitched from fabric printed like a ten-dollar bill. Clearly visible on her left elbow is the motto of the United States of America: in God we trust.

Relegation

The clothing-store axiom “A customer without a bag is a customer who will not shoplift” does not hold true at Sephora. This, ipso facto, relegates the axiom to the status of a mere theorem. At Sephora, underpants, bras, pockets, scarves, baseball caps, gloves, baby buggies—in fact, anything that can be worn on the human body or used to transport small human bodies—are susceptible to being used as a cache or as a means of concealing an item that has not made the requisite stop at the cash register.

MIB and WIB

At Sephora, the Men in Black are the security guards; the WIBs, the Women in Black, are those who wear the niqāb.

Confusion

From time to time a WIB wearing the fullest veil slips a lipstick or an eyebrow pencil beneath her niqāb. The security guard is convinced he has caught a shoplifter red-handed, until he notices that, in her other hand, the WIB is holding a small mirror that also disappears beneath the veil.

The Hijab and the Hoodie

No one is allowed to enter Sephora wearing a hoodie with the hood up. But it is perfectly not forbidden to wear the hijab, or even a niqāb. What approach should the security guard take if he should see a young woman coming in wearing a hoodie over her burqa?

Floko

A white woman comes into the store carrying a bag on which is printed a large red colonial fez.

In French colonial Africa, the gardes-de-cercle were brutish, moronic Africans who were cruel and zealous in carrying out the orders of their white masters. In Bambara, the word floko means a little bag. The foreskin, which looks like a little bag at the end of the penis, is also called a floko. Metonymically, the word is used to refer to those who are uncircumcised. In countries where circumcision is often a rite of passage, an initiation into adulthood and personal and collective responsibility, being called uncircumcised is particularly insulting. Loathed by the people for their brutality, the gardes-de-cercle were nicknamed floko guards. Each wore a red fez.

For Whom the Metal Detector Tolls

The walk-through metal detector tolls when anyone enters or leaves with an item that has not been demagnetized. It signals only hypothetical guilt and, in 90 percent of cases, the item has been duly paid for. But it is striking to note that almost everyone heeds the command of the security gate. Hardly anyone is insubordinate. However, reactions differ according to culture or nationality:

The Frenchman looks around, as though someone else were responsible for this noise and he is merely looking for the culprit—in the spirit of collaboration.The Japanese customer stops dead and waits for the security guard to approach.The Chinese shopper does not, or pretends she does not, hear, and continues on her way as nonchalantly as possible.The French citizen of Arabic or African ancestry accuses the device of conspiracy or racial profiling.The African jabs a finger at his chest as though seeking confirmation.The American rushes over to the security guard with a broad smile and all bags open for inspection.The German takes a step back in order to check that the system is functioning correctly.The Gulf Arab adopts a lofty, supercilious expression, and slowly stops.The Brazilian puts his hands in the air.Once, a man actually fainted. He was unable to confirm his nationality.

Dior J’adore

This perfume exerts a powerful magnetic attraction on Arabic, Chinese, and Eastern European women. The boutique runs an informal daily sweepstakes for the buyers of Dior J’adore. Yesterday, the grand prize went to the United Arab Emirates, to a woman who had €1,399.76 worth of Dior J’adore in a shopping basket that came to a total of €3,456.85.

Fast ATM

Seven seconds, including the time needed to enter the pin: this is how long it takes the HSBC ATM on the Champs-Élysées to spit out twenty euros. It takes forty-three seconds for the Crédit Lyonnais on the rue Louis-Bonnet in Belleville to perform the same task. On the Champs-Élysées, money is quickly dispensed, and just as quickly expended. In poor neighborhoods, even cash machines are reluctant to hand over cash.

Break

In the lingo of security guards, “to take a break” means to stand in for a colleague at another shop while he takes a break. In this way not only does he do a favor for his colleague, he notches up another hour’s overtime. This is also a way of discovering other shops.

Break at La Défense

At the Sephora outlet in La Défense, the head of security is an Ivorian of a certain age who goes by the nickname Éric-Coco. He is completely possessed by the spirit of Chanel.

“While I’m in the back, you keep an eye on the Chanel, especially the six-point-eight-ounce No. 5s.”

“What?”

“People tend to steal the large No. 5. Oh, and the three-point-four-ounce Allure. I need you to stop them.”

“Okay, but what exactly are we talking about?”

“We’re talking about Chanel, for god’s sake! Chanel No. 5 and Allure de Chanel. Perfume. Premium perfume. Why do you think you’re here?”

Break in Levallois-Perret

In this Paris suburb with bourgeois delusions, the Sephora outlet is in the paved, pedestrianized town center, next to all the other brands that exude fake luxury and fake sophistication. The boutique is not very big, and all the departments are within eyeshot of the security guard, who does not even need to turn his head. Inside, the atmosphere is muted; staff and customers whisper, perhaps to avoid disturbing the sacred perfumes, perhaps to avoid altering their chemical composition with raised voices. In an outlet of this kind, shoplifting is rare.

Break in Vincennes

The shop in Vincennes stands right outside the castle. Back in the days when it was inhabited by a Louis the Umpteenth, body care and bathing were vanishingly rare.

Police Presence

The avenue des Champs-Élysées is teeming with plainclothes police officers. They always wear jackets, regardless of the season, and white earbuds, plugged into iPhones on which they livestream the mug shots of France’s most wanted. They are easily identifiable at five hundred paces but believe they are utterly invisible. As we say back in Assinie: “Everyone can see a swimmer’s back, except the swimmer.”

Revolutionaries

So pleased were young Tunisians by the Jasmine Revolution they had launched in their own country and by the overthrow of the dictator Ben Ali that battalions of them took the Mediterranean by storm and found themselves in France. With little education and a limited grasp of the language of Jamel Debbouze, left to their own devices, they spend their days in Paris much as they did in the ghettos of Sousse or Tunis: between idleness and petty theft. For them, the height of elegance and fashion is to dress like the young people from the French banlieues. But they have neither the swagger nor the lingo and, as a result, are easily recognizable.

Security guards have dubbed them the revolutionaries.

“Heads up, three revolutionaries prowling around the Good Dye Young stand!”

“Revolutionary uprising in Bath and Body.”

“Man the barricades, the revolutionary in the red baseball cap has a Sauvage body spray in his underpants.”

A “revolutionary” has been seen in the act of shoplifting. Until he leaves the shop, he cannot be searched or considered a thief. But if he jettisons the fragrances whose packages he exenterated, he must pay for them. There follows a surreal low-speed chase in which security guard and shoplifter calmly wander around the shop side by side. After almost half an hour of this preposterous game, the revolutionary cracks and loudly and intelligibly demands his own arrest. Down his trousers, two bottles shaped like clenched fists: Diesel, Only the Brave.

Auction

All of the sales assistants at Sephora are awarded performance-related bonuses from the products they represent. All of them have developed techniques for luring customers in and persuading them to buy one perfume rather than another. Most simply spray the passing customer with perfume or hand out presoaked scent strips while babbling a few words.

But one of the male sales assistants has become famous for his technique, which involves interspersing his praise for the perfume with carefully disguised slogans from the 1968 student protests. A week ago, he was proclaiming the glories of Bleu de Chanel:

Beneath the paving stones, the beach…

Bleu de Chanel.

A fragrance that is beguiling, bewitching, bewildering.

Allow yourself to be beguiled by the sensual notes of musk, bewitched by bright notes of bergamot.

A breath of amber wreathed in a cloak of castoreum.

Beneath the paving stones, the beach…

Next week, he will be working the Givenchy concession. His spiel will begin, “Be realistic, demand the impossible…”

Esprit de Corps

Still standing: the trait of the security guard.

Esprit de Corpse

Still standing: the fate of the security guard.

Thief

The floppy chestnut fringe, the flawless side parting, the perfectly ironed blue-gray shirt, the immaculate black trousers that fall over neatly polished shoes—all these make him look like a British prime minister in mufti. Yet there is something incongruous in this portrait of the ideal brother-in-law. It is unusual to have a backpack and a shoulder bag when dressed as though you are about to give a PowerPoint presentation to an urban-planning consultancy. His nonchalant air as he stands next to the Dior concession is a little “hammy.” A filmmaker’s term. This man is “iffy.” A security guard’s term. But no one has seen him do anything suspicious. Confirmation comes over the headset: “J5 in a tie at the Dior concession—nothing to report.” The Dior concession is the first the customer encounters when he enters the store, or the last as he leaves it. Will the man venture farther into the store or leave straightaway? With his sidelong looks and his squinting, it is the security guard who now looks “shifty.” A thief’s term. The man does not move. He enters into a conversation with one of the salesgirls. The security guard cannot hear a word of what is being said. The salesgirl smiles. Apparently, the man is pleasant company.

On this early summer evening, the store is thronged with customers, making it impossible to focus on one man. A large group enters. Their accents are Slavic. Poles? Russians? Czechs? Their shoes are covered with a fine but visible layer of white dust. They have clearly been to the Louvre and amassed this layer of dust walking through the Tuileries Gardens. It is the most direct route from the Louvre to the Champs-Élysées, and most tourists stroll all the way to the Arc de Triomphe. The branch of McDonald’s next to Sephora is where they stop off after this marathon. The staff at Mickey D’s call them the palefoots.

A palefoot woman approaches the security guard. She is accompanied by a sullen child clutching a balloon shaped like a smiling Mickey Mouse on the end of a plastic stick. She wants to know where to find the Métro. The security guard points. The gaping maw of George V Métro station is fifty yards up the street. Glancing over the woman’s shoulder, the security guard sees the man with the floppy fringe. He is creeping out of the store, hugging the far wall. Their eyes meet. In both of their minds, a penny drops. The man is quick off the starting blocks, sprinting down the avenue. The security guard is slower to react. The long hours spent standing have left his joints stiff. Whoever the thief is, he now has a ten-yard head start. He glances over his shoulder and sees that the security guard is running after him. There are no shouts, no screams.

The Champs-Élysées is crowded. The thief zigs, the security guard zags. At the thirty-meter mark, the security guard’s biomechanics grind into gear. Glancing over his shoulder again, the thief notices. In a feat of remarkable dexterity, he manages to disentangle the bag slung over his shoulder without breaking his stride, and tosses it behind him. Jettisoned ballast, a votive offering, or both. But the security guard keeps going. He had anticipated this maneuver; he hurdles the bag before it even hits the polished granite slabs of the pavement. The thief continues to zig, the security guard to zag, faster and faster. The thief’s necktie flutters behind him, hovering parallel to the ground in the headwind. The security guard’s tie does likewise. A few more meters and the thief will be within his grasp. Suddenly, the traffic light ahead turns red, and, familiar with the highway code, he stops. But this is merely a coincidence. In the mind of the security guard, another red light flashes. What is he thinking running after this man? What if he’s armed and dangerous? What great moral imperative is satisfied by pursuing a perfume thief? This is probably how you contract floko guard syndrome. The colonial guard with his white truncheon, his inane grin, and his fez… red. Red means stop. The thief vanishes into the crowd. The security guard retraces his steps. In the jettisoned shoulder bag, he finds three bottles of perfume: Elixir Pour Homme by Azzaro, Diesel’s Fuel for Life, Allure by Dior.

Translated from the French by Frank Wynne.

GauZ’ is the pen-name of Armand Patrick Gbaka-Brédé, born in Ivory Coast in 1971. His first novel, Debout-Payé, was awarded the Prix des libraires Gibert Joseph and chosen as best debut novel of the year by the magazine Lire. Debout-Payé, translated as Standing Heavy, will be published by MacLehose Press in May 2022. GauZ’s most recent novel, Camarade Papa, won the 2019 Prix Éthiophile.

Frank Wynne is an Irish literary translator. He has translated numerous French and Hispanic authors including Michel Houellebecq, Javier Cercas, and Virginie Despentes. His translations have been awarded the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and he has twice been awarded both the Scott Moncrieff Prize and the Premio Valle Inclán. He has edited two major anthologies, Found in Translation: 100 0f the Finest Short Stories Ever Translated (2018) and QUEER: LGBT Writing from Ancient Times to Yesterday (2021).

February 11, 2022

The Review’s Review: Mathematics of Brutality

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

“A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery,” goes Mao’s famous dictum. “A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence in which one class overthrows another.” The aftereffects of this kind of violence on a nation’s citizens is the subject of the South African writer C. A. Davids’s new novel How to Be a Revolutionary, out from Verso this month. In chapters that crisscross between present-day Shanghai, apartheid-era Cape Town, Beijing during the suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests, and a series of McCarthy-era letters from Langston Hughes to a South African friend, Davids follows the friendship of Beth, a South African diplomat, and Zhao, a Chinese writer, as they come to terms with the moments of betrayal, naivete, and political cowardice in both of their pasts.

But history, like revolutions, is complicated, and Davids is sensitive in her portrayal of the impossible choices that ordinary people face during moments of acute political crisis. “Do not forget,” writes Zhao in a manuscript that will appear on Beth’s doorstep early in the book, “that there exists a mathematics of brutality where the amount of blood spilled is inversely proportional to emotional resonance, so that after the first viewing of an act of inhumanity one begins to grow numb somewhere inside one’s head and heart.” Writing isn’t a revolution—but it is a way of recording one’s humanity. —Rhian Sasseen

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, the debut graphic work from Mannie Murphy, plays on the myth of Portland as a liberal haven, a city of roses sequestered from the far-right enclaves that pockmark the rest of the state. It begins as a rumination on River Phoenix, and the artsy punk Portland crowd that took him in, and mushrooms into an account of white nationalism in the Pacific Northwest. The book hinges on the hate crime that alit Portland in 1988, the murder of Mulugeta Seraw, a college student who had moved to the city from Ethiopia to study business. It traces the connections between Phoenix, Keanu Reeves, Gus Van Sant (who made Phoenix his pet), the punk club owner Mr. X, and the killer, Kenneth “Ken Death” Mieske, another of Van Sant’s teenage muses and a member of the neo-Nazi gang Eastside White Pride. I Never Promised You a Rose Garden paints a portrait of a fraternity for the vulnerable, the volatile, and the bigoted. Murphy demonstrates that the history of Oregon itself is bathed in white supremacy, its founding tied to the aspiration for a white ethnostate. Murphy recounts Ken Death’s murder trial and its resonance outside the courtroom, and also acts as amateur investigator, tracking down incriminating details in old footage, and as a memoirist: Murphy grew up in Portland, attended the same K-12 school as Phoenix, and crushed on him as a fan. Murphy’s handwritten cursive script, which accompanies the illustrations on lined newsprint, oozes the naivete and intimacy of a diary entry or elementary school composition book—a fitting choice for a book that is both confession and corrective history lesson. Their illustrations, drawn with a paintbrush, are in the gray and indigo palette of that drippy city. Each one dimples in the places where pools of water-soluble ink have bled through and dried. It’s rare to find a graphic artist whose captions and drawings are balanced in their storytelling power, but Murphy is one.

Like Murphy, the photographer and textile artist Lisa Anne Auerbach is ambivalent about the legacy of punk. At seventeen, she’d go to all-ages shows in Chicago, pull out her camera in the middle of the mosh pit, and shoot the sweat-streaked faces streaming past her, the teenagers in their homemade band tees, the boots in the air, and the skinheads swinging by with their bare torsos and shining scalps. She developed the Tri-X film in her high school darkroom and hung on to the negatives for over three decades. A selection of these photos, taken in the spring of 1985 at the clubs Cubby Bear and Cabaret Metro, were recently assembled into the gorgeous photobook PIT. Published by the Glasgow-based workers co-op Good Press in 2021, the book is slim and potent. It includes a great introduction by LAA, full-page black-and-white photos printed on rich card stock and paired as diptychs, and an interview with the artist conducted by Ethan Swan, a writer of DIY communities and music subcultures. “I wanted to document the choreography and ecstasy of the pit, the half naked bodies, the camaraderie and ritual and aggression,” LAA writes. She also discusses the mechanics of nostalgia and the ethics of reproducing images like these, in which you can glimpse, knocking against and mixed into the mash of bodies, the hardcore racist with his uniform of leather, pins, and Aryan skin burning under the camera flash. You can’t look at the pit without also seeing a space where full-on and “fashion” skinheads alike might be purging some of their antagonism. PIT speaks to the countless things the pit came to be for those who eyed it from a distance, haunted its fringes, and tossed around in it: “The audience moved like a wave, a mass, a school of fish, a pile of garbage. We responded to music, to movement, to one another. The pit was codified and random, organic and tempestuous.” —Jay Graham

February 10, 2022

Narcotics

Gary Indiana, Cookie as my ex-boyfriend, New York, 1980.

I was at a sedate little cocktail party in SoHo, one of those uneventful parties I wound up at once a week. It was a typical SoHo art shindig: there was a full bar, sliced raw veggies and clam dip, bread sticks, mini-wieners and pea-size meatballs floating around in red sauce in a hot stainless-steel pan. The usual bunch of scrubbed, aspiring, New York art climbers were there mingling and tittering and chit-chatting discreetly, the women in sensible low heels and expensive stockings with no runs, and the men in silk ties, designer sports jackets, and clean jeans.

A few of the men with goofy-looking bloodshot eyes were passing around marijuana; the ladies were giggling and tossing their sleek pageboy hairdos around, acting like they’d never seen marijuana before. These women were young, fresh out of college, but they were always trying to make themselves look old for some reason. I never understood that. They wore gray baggy dresses and a few pieces of tiny, tasteful, conservative jewelry.

There was a man standing near me at the butlered bar, flirting with one of those bland-looking, corn-fed debs in gray. They were smoking a joint. The girl—this perky, peppy, preppie—started to cough, and he laughed and attempted to cuddle her for her cuteness. He turned to me only long enough to hand me the joint.

“Here,” he said, “you look like the type that could handle this.”

“No thanks,” I said, “I don’t use drugs … only narcotics.”

That was the truth. I’d stopped using marijuana. It made me paranoid.

The person I’d come with, Alvain Arles, the art critic and historian, came over to me.

“This is a real bore. A snore fest. Let’s get out of here,” he said. Alvain was many things, but never boring. He had a hard time tolerating people who were. I hurled back my martini and we slipped out the door.

“You think UFO or SHELL SHOCK will be out yet over on Fourth Street?” he asked.

“I don’t think so. But ROADRUNNER or SEVEN UP or NAUSEA ought to be out on Seventh Street,” I said, as we tried to hail a cab.

“How about T.N.T. or DOLT BOLT?” he said in the cab, counting his money, “they’re a little stronger.”

“Let’s just head straight for 10th Street for POISON or BLACK DEATH,” I said, “they’re always open. They have TOXIC and RADIOACTIVE there too.”

“So where’ll it be?” the cab driver asked.

“Just head for the east side,” Alvain said. “How about IMPALE or PEG-LEG? VIRGIN DEVIL, X- RATED? Or PARALYZE or WALLOP or LOT O’ROT?”

“Never had any of those except WALLOP. I don’t even know if WALLOP still exists. You have to go for the newest stuff … after a week or two the quality always plummets. How about SWEET SIXTEEN or TRUE BLUE? Wait, wait! Why not TOILET?”

“Hey!! Okay!! Yeah!! TOILET’s out now, so’s TORTURE!” He got excited. “Driver, take us to East Third Street and Avenue B,” he said, and settled back, happy. “TOILET and TORTURE. Either one is great.”

We were talking about heroin. These were the names rubber-stamped on the little glassine packages of ten-dollar amounts sold on the Lower East Side streets. Junkies, weekend users, and other heroin aficionados memorized all the names by heart; they knew where to get each one and exactly what time the “store” opened.

I wondered what this cab driver thought. Maybe he thought we were going over the names of our favorite exploitation films or dirty books, or discussing S&M bars.

We got to the corner of Third and B, and Alvain hopped out. “You hold the cab,” he said. “It’ll take one second.”

The cab driver waited for four seconds and then he turned to me, “Hey, I don’t wanna sit here. I’m losing fares,” he said.

“Don’t worry. We’ll make it worth your while,” I said.

“No. Pay up, I gotta go.”

I gave him the money and got out. That was a drag. Ordinarily, it was no calamity being without a cab, but I was looking a little too spiffy in my cocktail regalia for that neighborhood at that hour in that time of the decade. I was also holding the rest of Alvain’s money, and junkies can smell money, especially if they’re thieves or dope sick. I looked around for Alvain and saw him down the block talking to a Puerto Rican guy in red-and-white running clothes, probably flirting, because the guy was cute and he was Alvain’s type. I walked up to them and heard the Puerto Rican say, “Yeah, TORTURE’s smokin’ righ’ now. I seen ’em carron out somebody who jes O.D.ed on it. You give me ya money an’ I’ll git it fa ya.”

“And that’d be the last I’d see of you,” Alvain laughed. “No, I know where to go.”

The guy kept trying to think of some way to get some money from us, and he walked beside us talking nonstop. I could tell that Alvain was falling in love.

“Okay, I’m gonna give ya one of my bags,” Alvain said, and gently tweaked the Puerto Rican’s beardless chin.

We walked over to the burned-out building where people were lining up in the dark hallway, clutching their money, waiting to buy. Everyone was very quiet. The first guy in line put three ten-dollar bills through a slot in a door in the back of the hall and out of the slot came three glassine bags of TORTURE.

A big black guy standing at the hall entrance was keeping everything moving. He worked there. “Hurry up, move along, have your money ready, step up,” he was saying.

A punk rocker in front of me was talking to a skinny Italian American guy, “Yeah, somebody jes O.D.ed on this shit minutes ago. Must be the best shit on the street right now.”

“Told ya,” the Puerto Rican reminded us.

“Great!” another person in line said, “I’m lucky I came out now.”

“Yeah, my ol man was sa high on TORTURE yestada, he was throwin’ up all ova da place,” said a skinny birdy girl in a blue leather jacket. “Was goooood sheeet, man!”

“Shhh!” said the big guy at the entrance.

Mixed in with the losers and hardcore users were a few prosperous types waiting in line: a Wall Street man, a blonde-haired model I’d seen in last month’s Vogue, a famous post-minimalist sculptor, a famous filmmaker, and a guy I’d seen once on some daytime soap opera, Another World, or The Edge of Day, or City Hospital. I can never remember the names of those shows.

When Alvain and I got to the dope door, Alvain slipped his money through the slot and out came six little white rectangular packages, taped with clear tape and stamped with the word TORTURE. With the goods, we bustled out the building and walked fast off the block. Alvain gave one to the Puerto Rican, and the Puerto Rican disappeared. Alvain was temporarily heartbroken.

He got over it immediately when we saw a cop car cruising down the avenue. Instant paranoia. If they decided to stop us, we would go directly to jail for the night, even if we’d had just one measly bag between us.

I heard the lookouts, young kids who worked for the dope houses from the rooftops, start yelling, “Bajando! Bajando!” That was the Spanish alert. It meant the cops were coming. We saw people walking very fast out of the building we’d just come from. Another watcher from the corner yelled, “Don’t run! Calm down! Don’t run!” People on the street who were heading toward the building just turned in their tracks and walked fast the other way. In less than two minutes the street was empty. The whole thing was really organized. By the time the cop car appeared around the corner and cruised slowly in front of the building, everything was peaceful.

I’d seen a funny scene one day at a dope spot on Rivington Street. People were lined up against a waist-high wall, waiting to score. Suddenly the alert went out, a cop car was coming, so the seller and all the people in line dropped on all fours and were hidden by the wall. After the car went by, it was business as usual, everybody just stood up.

The sellers were always trying to be one step ahead of the cops. A few dope houses were doing the routine where the sellers would lower a basket from the window on a rope, the customer would put in his money, and the basket would be raised. Down would come the packages of dope. When the cops came, the basket would be raised quickly and the crowd would disperse. The dope scene had no room for sloppy salesmanship. There were many workers.

Before the cop car got to us, we found a cab right on the next block. That was luck. We drove past Ninth and B and there was a guy with a knife standing over a person who’d been in line at the building we’d just come from. The guy on the ground wasn’t hurt, he was reaching into his pants pockets, pulling out his heroin, and handing it over. As we whizzed past I heard him cursing, “Shit. Dammit, now I’m gonna be sick. Common, man, leave me jes one bag. Fuck!”

“Poor kid.” Alvain looked back at the scene.

“He ain’t gonna hurt ’im,” the cab driver said. “He’ll pralee leave him one bag too.” Anyone on the streets there at that hour knew what was happening.

“Good thing we found you when we did,” Alvain told the cabbie.

“Yeah. I saw you two in line,” he laughed. “Where to?”

Friends of mine who went to buy dope in that neighborhood would sometimes have their watches, earrings, rings, and all their drugs and money taken. An artist friend had gone there right from an opening and he’d been all dressed up in his leather jacket, his cowboy boots, his best wool tweed pants. The person who ripped him off at knife-point wasn’t satisfied with just the dope and his money. The thief also took the jacket, boots, sweater, tweed pants, and even my friend’s boxer shorts. Stark naked, he started running home, freezing. On his way he searched the garbage cans for something to wear and finally found a dirty pink sweater, so he put his legs in the sleeves and ran, hoping he didn’t see anyone he knew. At least his wang was covered.

I laughed uproariously when he told me this story. In retrospect he too admitted it was very funny, but at the time he’d been mortified.

Things like this were always happening there. Friends would occasionally get arrested and wind up in jail for the night, or they’d lose their rent money. I’d never known anyone to get stabbed, but I’d never known anyone stupid enough to refuse to give up their stuff to a thief with a knife. Some people, new to street copping, would give their money to guys they thought were dope-house runners. Of course these “runners” wouldn’t ever return. If you happened to find a real runner, he would come back with the dope, but he’d take one or two bags for the run. So it was expensive and sometimes dangerous over there. For that reason, a couple of friends started selling heroin from their homes.

Barbara did. She’d written a mammoth novel that weighed something like ten pounds. She lived with her paramour, Jane, who was a rock and roll musician. They were good friends of mine before they started selling dope, and while they were selling it I saw them every day. Way more pleasant than the street, there was always a fire burning in the fireplace, lots of books on the shelves and flowers in vases. The cats were curled up on the chairs, there was the smell of fresh coffee. It was a home.

A few close friends would visit Barbara and buy some heroin. She made some money, everyone was happy. A habit takes months, sometimes years of dabbling with the stuff before it creeps up on you. I think a lot of these people were shocked to find themselves dependent on heroin even though they weren’t shooting it but snorting. Some people are dumb enough to believe you can’t get a habit if you aren’t using a syringe. At a certain point, a lot of the people I knew were using heroin, and some of them had habits, but no one took it too seriously. Everyone would always joke about it and everything was playful … but … being dope sick wasn’t pleasant, or fun, or romantic. Baudelaire, Poe, Coleridge, and all those writers who flirted with opiates didn’t write much about the sick part.

A heroin habit isn’t a problem for the user until there’s no money. I remember one New Year’s Eve party, held at this chic French restaurant, where all the guests were high on heroin. Everyone’s pupils were pinpoints; everyone was in a vegetable state, and acting cool like cucumbers. All eyes were dry at the stroke of midnight, and there wasn’t a whole lot of laughter; there wasn’t much outward display of emotion, like there was at drinkers’ parties, but in their black little junky hearts everyone was feeling warm and loving, they just couldn’t show it.

Everyone was standing up and mingling and talking; if they’d sat down they probably would have nodded out. They were all really good friends, people who’d gotten to know each other from the Mudd Club days before, and it was great to see everybody, even through the dopey haze of dope. These heroin users, like drinkers everywhere, had used the New Year’s Eve excuse to get higher for this night, and everyone was as stoned as they could be. At one point, after midnight, I turned to a filmmaker friend of mine.

“Look around,” I said, “Do you realize that every single person here is high on heroin? It looks like a Zombie Jamboree.”

He scanned the group, “You’re right,” he said, and laughed. I told everyone, and everyone laughed about it. We all had a good time that night, even though a lot of people were dozing off on their feet, buoyed up by the crush of friends around them. Yeah, everyone had fun, even the people who missed most of it because they were in the bathroom throwing up, or snorting more heroin.

It wasn’t like those typical SoHo art parties, like the one where they had passed marijuana around, where the guests had never known scary 4 A.M. walks in the heroin neighborhood, where none of them ever was dope sick, or ever ran home wearing a dirty sweater on their butt, or ever went without food for three days because there wasn’t enough money for food and dope too. Those people, the dope innocent, who never found themselves suddenly in a lowdown compromising situation of need, seemed like adolescents to a junky. The non-users were a whole different set of people. They might have been smarter for never getting involved in dope, but it’s a fact that when junkies become ex-junkies, they’re somewhat the wiser, having seen hell.

Cookie Mueller, née Dorothy Karen Mueller, played leading roles in John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, Desperate Living, and Multiple Maniacs. She wrote for the East Village Eye and Details Magazine, performed in a series of plays by Gary Indiana, and wrote numerous stories that would only be published posthumously. She died in New York City of AIDS-related complications at age forty.

A version of this previously unpublished piece will appear in Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, New Edition: Collected Stories , which will be published in April by Semiotext(e).

February 9, 2022

A Dew-Lined Web: On Sula

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.