The Paris Review's Blog, page 89

March 7, 2022

To the Son of the Victim

Santa Rosa–Tagatay Road in Don Jose, Santa Rosa, California. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

Santa Rosa, California

I met you the day your father was shot and killed. I’d been in Oakland for a pink sunrise, watching police sweep a homeless encampment, gathering what we called “string” from residents who had nowhere—yet again—to go. I felt more outraged than usual and also maybe more useful. This was journalism, I suppose I was thinking, making sure the world knew what was happening right here. I wrote three hundred words for my newspaper’s website in a café and was preparing to drive back across the Bay Bridge in brilliant golden morning light. Then I got a call.

An editor back at the office on Mission Street was listening to the police scanner and heard something unusual going on near Santa Rosa, about sixty miles northeast. Since I was already out, could I go? I could. I drove north, generalized dread already flushing cold through my veins, though I had no sense of what I was going toward. This is what the days were like, back then: waiting for something to happen, hoping it wouldn’t, getting the call, driving, always driving, toward disaster.

There were black SWAT helicopters flying overhead and mixed reports from my editors: a robbery at two different addresses in Santa Rosa, three dead. Or maybe only one person was dead? Maybe they were related; maybe they weren’t. Someone seemed to think that it had something to do with marijuana. I kept driving north into the brilliant sunlight, in a direction that—on other days or for other people—might have led to wine country or skiing in Tahoe.

Then the road turned into a vast sprawl of neon signs. I stopped at a gas station to buy a water bottle and a phone charger, a little shaky from hunger. I was listening to a song on repeat: “Heard you were rolling in the good times out West, went to the desert to find your destiny and place . . .”

I’d moved to San Francisco just a few months before to become a “breaking-news reporter.” The romance of breaking news was that you were just thrown out there, learning on your feet, somehow transforming into a real reporter in the process. I had wanted this badly, all of it: the crime scenes and fires, the early-morning wake-ups and late-night phone calls. But it turned out I hated showing up on people’s doorsteps in the wake of disaster and death. One Friday, there had been reports of a hostage situation many miles north. While the details emerged online and over the radio, I did something unforgivable in the profession: I went to the bathroom, took deep breaths, and waited a few minutes until someone else was sent instead.

The first Santa Rosa address was a bust. Or, rather, it wasn’t really an address at all—it described a long stretch of halfway highway between two traffic lights. There were a few houses and I knocked on their doors but, to my relief, got no answer. I drove on, down a road that cut through farmland, where the distance between mailboxes grew longer. There were horses and shocks of green, as though drought had never struck here. This was the kind of place where neighbors could be relied upon to say, I can’t believe that something like this would happen here of all places. Then I saw the Sonoma County Sheriff’s truck hulking beside one of the mailboxes. This must be the place.

There were large cactuses and there was yellow tape. Even as I flashed my press pass, it was clear I wasn’t going to get very close to the scene—to your house, a low, white ranch house I could see from the driveway behind the kind of padlock gate that would keep horses in. A grizzled deputy with a red beard and sunglasses looked at me with disgust. “The family’s not interested in talking, ma’am,” he said.

“Can you tell me what’s going on?” I asked. Reporting under conditions like this was always full of roadblocks, and the primary obstacle was usually someone in uniform.

“You’ve got to call the press line,” he said. He was disgusted by me, and I by him. Sometimes the only thing that motivated me in my reporting was the stoic “No” of police officers and sheriff’s deputies and flacks on the phone. I pulled up nearby to wait. I fiddled with my phone, checked for new statements from the different law enforcement agencies, texted friends in New York—a boy I loved was there—and then looked up to see you, leaning on a gate and looking straight at me through the windshield.

I grabbed my notebook and scrambled to get out of the car, up to the gate. We stood for a minute in the dusty early-afternoon heat and didn’t say anything.

You were about my age, give or take. I was twenty-two. You had been crying, though you made a good attempt at hiding it, red rims around your eyes.

I can’t remember what I started to say, maybe something like, Hi, I’m a reporter, I know today must be a hard day, but I was wondering if you could tell me a little more about—

“We’re not talking to anybody right now,” you said quietly, looking down. I looked down, too, and saw you were wearing dark leather cowboy boots.

“I’m really sorry to bother you, it’s just that”—I was trying to figure out what to do with my hands, gesturing too much, probably—“we’re hearing reports that someone was killed here last night and I wanted to know if you could tell me if that’s true?”

To that, you said nothing; you looked at me and turned away, walking back toward the house. The cop was watching me from the car with the window rolled down. Maybe he shook his head, or maybe that’s something I’ve imagined since then.

I drove away, back to the first set of addresses, and fielded calls from frustrated editors. Someone from the family—perhaps you?—had spoken earlier to the Press Democrat and confirmed that a man had been tied up, tortured, and shot dead in the middle of the night. The suspects were a group of men who had mistaken the property for a cannabis farming operation—or perhaps it actually was one? Could I go back and find out? I could.

When I got there, I stayed in the car, engine on, watching the clock and hoping you wouldn’t return. But you did, this time flanked by two men—boys?—who looked about your age. Maybe cousins or brothers or just friends. You recognized me and you looked my way almost imploring, as if to say, “I already told you: I need some time.” The three of you walked toward a parked truck. I wish I’d given up then, but I instead followed numbly.

“You need to leave right now,” said one of the other boys. I liked him for that.

“Can I just give you my phone number, in case you’d want to talk later?” I asked.

“Okay,” you said, surprising me. But as I tried to write my number down, my pen ran dry. We stood awkwardly facing each other as I tried to sketch it, us just standing there in the brutal heat, your red-rimmed eyes behind sunglasses. Finally, I was ready to quit; I even shrugged. But then you pulled a pen out of your pocket, and you let me use it.

I have thought so often of this day—of my cruelty and your pain, of how powerful I was and how powerless I felt, of the pen you lent me, right in the moment of my defeat. What you must have felt that day remains impenetrable to me, even as I know more of the story, or at least as I know the bits of it that were reported in the following days, before everyone looked away. Your father was shot ten times while you and your mother were bound to chairs, with duct tape in your mouths. Four men and one woman were eventually arrested. More than a year later, a murder trial was ordered. It has yet to happen. That’s one version of the story, but the ripple effects of that night are, I am sure, a much longer and more complicated story than could ever be written. No one has even tried, least of all me.

That day in Santa Rosa, I imagined that you hated me, but I now suspect you didn’t think much of me at all. Probably I was part of the collateral of your grief, the random details—chipped nail polish, oddly shaped clouds, the color of someone’s hat—that one notices in the moments before or after catastrophe. If you remember me at all, I imagine that it’s like that: a girl standing improbably in the glare of sunlight and rising dust, borrowing your pen after hers runs dry, the sound of gunshot still fresh in your ears. Regardless, you were generous to me on a day when you had no reason to be. I wish I’d been kinder in return.

Sophie Haigney has written for the New York Times, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, the Economist, The Atlantic, Slate, The Nation, and the Boston Globe. She was Off Assignment’s first managing editor and helped get the Letter to a Stranger column off the ground.

From Letter to a Stranger © 2022 by Colleen Kinder. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

March 4, 2022

The One Who Happened

Illustration by Thomas Colligan.

He happened to hear the world was square, like the square table at home that could be used for eating or playing cards on.

He happened to hear that the emperor is made so by divine right, but he was just a commoner so that’s nothing.

He happened to have not heard of Hitler; that guy with a little mustache avoided him for nineteen years.

He happened to have not heard of the Cultural Revolution, and looked at himself in the mirror in a positive light.

When he came to Beijing, it happened to be a clear day, no smog;

in a spurt of energy he went to Inner Mongolia, where he happened not to run into a sandstorm and so never got lost.

Convinced by the blue sky with white clouds above the grasslands that all distance was reachable,

he happened to meet a stallion that let him ride for one hour at full gallop between heaven and earth.

Back in his hometown, he happened to not run into the accountant’s daughter, so he married the daughter of the fruit wholesaler instead.

On the street, he happened to avoid a car crash, and it was great that life could go on.

He learned how to bray just like a donkey, and he was so happy he didn’t notice it was a donkey braying in Chinese.

He happened to be born Chinese, happened to read Dream of the Red Chamber not Gargantua and Pantagruel.

He happened to know poplars and willows, but not the paulownia tree.

He happened to find three wallets, but if there were a fourth time would it still be that he happened to?

He happened not to know the rich connotations of the word second, and though his neighbors know they’re not telling him.

He has experienced a second-rate happiness, and happened to be encouraged by the spring breeze.

Translated from the Chinese by Lucas Klein.

Xi Chuan is an internationally acclaimed poet, essayist, and literary translator. Among the numerous honors he has received are the Lu Xun Literature Prize (China), the Cikada Prize (Sweden), and the Tokyo Poetry Prize (Japan). He lives in Beijing.

Lucas Klein is a father, writer, translator, and associate professor of Chinese at Arizona State University. He has translated Mang Ke, Li Shangyin, and Duo Duo, and his second book of Xi Chuan translations, Bloom & Other Poems, will be available from New Directions in the summer of 2022.

March 3, 2022

The Review’s Review: Vesna

Ukrainian ethno band DakhaBrakha on its concert in Lviv. Photo by Lyudmyla Dobrynina, Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

I have been thinking often of the 2017 anthology Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine, edited by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky. The collection includes nine poems by Lyuba Yakimchuk, who grew up in Luhansk, one of the regions taken by Russia-backed separatists in 2014. Her poems of that period bear witness to the decomposition of a country, a region, an identity, and language itself. Her words break apart under the pressure of violence: “my friends are hostages / and I can’t reach them, I can’t do netsk / to pull them out of the basements.” Now Yakimchuk is in Kyiv, working to help defend the capital as Russian shells fall. When the invasion began, she was already trained in military-style first aid and well stocked with supplies; she donated much of her store of gasoline to the local Territorial Defense Forces for Molotov cocktails. She has been documenting her experience on social media and in frequent interviews.

I am also reminded of the Soviet writer and four-time Nobel Prize nominee Konstantin Paustovsky’s memoir, The Story of A Life—long out of print in English, but now available in a new translation by Douglas Smith. Paustovsky was born and raised in Kyiv and attended gymnasium with Mikhail Bulgakov, whose White Guard is another classic of that city’s literature. During the First World War, Paustovsky served as a hospital train orderly, following the troops, collecting the wounded, and burying the dead. His memoir is a model of fine-grained, compassionate observation in the tumult of history and violence. In one scene, he listens to the dying words of a captured Austrian soldier who wants to confess that he is a Slav, captured in battle. “Why hadn’t he complained,” Paustovsky wonders, “or asked for a sip of water, or pulled out the metal chain holding the regimental disc engraved with the address of his next of kin as the other wounded Austrian prisoners did? He seemed to want to say that the world is run by the powerful and it wasn’t his fault that he had been forced to take up arms against his brothers.”

Today, you can watch another such memoir emerge in real time: the Kyiv war diary of the writer, photographer, and activist Yevgenia Belorusets is being updated regularly online here, hosted by Artforum in collaboration with the small press Isolarii, which recently published Belorusets’s short story collection Modern Animal. Lucky Breaks, her 2018 collection of half-documentary, half-magical stories about Eastern Ukrainian women and war, also just came out in English translation. Now, she turns her exquisite powers of perception to the bombardment of her own home city. “When I think about the beginning, I imagine a line drawn very clearly through a white space. The eye observes the simplicity of this trail of movement—one that is sure to begin somewhere and end somewhere,” she writes. “But I have never been able to imagine the beginning of a war.”

One of my favorite Ukrainian musical groups is DakhaBrakha, the theatrical, Astrakhan-hatted band that has become famous beyond Ukraine’s borders for their “ethno-chaos” blend of Ukrainian and world music. Their hypnotic 2011 video for “Vesna” (“Spring”) captures the gritty yet verdant beauty that made me fall in love with Ukraine. March 1 was the beginning of spring for Ukrainians; I hope that the new season will bring peace. —Sophie Pinkham

I remember taking “internet literacy” classes in third grade in which we were made to find examples of three reliable and three unreliable websites, based on a list of rules according to cues like their adherence to normative English (typos: unreliable), the modernity of their graphic design (rainbow fonts: unreliable), and their domain (.gov: very reliable). Two years later, on Facebook, we would begin making our own rules. These early experiments in semipublic, semicryptic semiotics—like identifying each of our friends as a loser, sidekick, or it-girl type by “tagging” them in an image of various Harry Potter characters—which our teachers were quick to decode (and discipline), have long since been made obsolete by ever more opaque forms of creative communication that came to the deeply online as naturally as bullying. The amazing thing about internet literacy is that it actually doesn’t have to be taught; in fact, it’s so intuitive that it’s difficult to put into words at all. But Libby Marrs’s “The Lore Zone: How to Read the Internet,” a careful structural study of this almost kinetic skill (navigating the proliferation of online languages), does just that. The essay, which thankfully transcends the tiresome hysteria surrounding the cultural meaning invested in the term vibe shift, draws on the concept of orality to describe the production of memory and meaning online. It more than satisfies one’s itch for formalization, and my specific desire to follow elaborate extended diagrammatic metaphors involving trees and rivers.

The “Lore Zone” essay series (coresearched by Marrs and Tiger Dingsun) is a product of Other Internet’s applied research into social technologies. The organization’s other reports include fascinating case studies of governance in online communities, granular interface critiques, and more meta-level opinion pieces on the social implications of various technologies. My favorite of these, “Positive Sum Worlds: Remaking Public Goods,” by Toby Shorin, Sam Hart, and Laura Lotti, is a philosophically and ethically rigorous investigation into the administration of the public sphere in the age of crypto protocols. It’s hard to find careful, legitimately technically informed analyses of digital culture, at least in legacy media publications—I recommend these! —Olivia Kan-Sperling

March 2, 2022

Against Any Intrusion: Writing to Gwen John

Santa Monica, 2019, oil on canvas, 40 x 48″. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro.

February 14, 2019

Santa Monica, California

Dearest Gwen,

I know this letter to you is an artifice. I know you are dead and that I’m alive and that no usual communication is possible between us but, as my mother used to say, “Time is a strange substance,” and who knows really, with our time-bound comprehension of the world, whether there might be some channel by which we can speak to each other, if we only knew how: like tuning a radio so that the crackling sound of the airwaves is slipstreamed into words. Maybe the sound of surf, or of rushing water, is actually the echoes of voices that have been similarly distorted through time. I don’t suppose this is true, and you don’t either. But I do feel mysteriously connected to you.

We are both painters. We can connect to each other through images, in our own unvoiced language. But I will try and reach you with words. Through talking to you I may come alive and begin to speak, like the statue in Pygmalion. I have painted myself in silent seated poses, still as a statue, and so have you. Perhaps, through you, I can begin to trace the reason for my transformation into painted stone.

It has been a time of upheaval for me and I have been trying to gather my thoughts. So many things have ended, or are ending. New beginnings, too. I have been thinking a lot about the past, about our past, and it has never struck me so forcibly as now, when I am nearly sixty years old, just how much our lives have been stamped with a similar pattern.

We both came to study at the Slade School of Art from our homes in the West Country; we both had passionate relationships with much older and more famous male artists, who we also modeled for; we were driven to find our true creativity by leading interior, solitary lives; we both became interested in abstraction (and the idea of God) in later life. The sea has always been important to us: you died trying to reach the coast at Dieppe, “feeling the old compulsion” upon you to glimpse the sea.

We both work best from women. Your mother died when you were only eight whereas mine died when I was fifty-five, yet mothers are of central significance to both of us. We are both close to our sisters, one in particular: you to Winifred, whom you often painted, I to Kate, my younger sister, who is my most regular sitter. The two men I have been most intensely involved with, Lucian Freud and my husband, Steven Kupfer—in both cases their girlfriend before me had been called Kate; I had suffered terrible jealousy at Kate’s birth and felt supplanted by her in my mother’s affection, but then grew to love her particularly. Jealousy heightens love; the special intensity with which we observe the object of our mother’s (or lover’s) devotion narrows the beam of our focus. Who was it who said that love was the highest form of attention?

One of the main reasons I want to speak to you now is because I’ve become increasingly aware of how both of us are regarded in relation to men. You are always associated, in the public’s eyes, with your brother Augustus and with your lover, Auguste Rodin. I am always seen in light of my involvement with Lucian Freud. We are neither of us considered as artists standing alone. I hate the term in her own right—as in “artist in her own right”—because it suggests that we are still bound to our overshadowed lives, like freed slaves. I hate the word muse, too, for the same limiting reason. We are both referred to as muses, and you have repeatedly been described as “a painter in her own right,” as I have. Why are some women artists seen for what they are uniquely? What is it about us that keeps us tethered? Both of our talents are entirely separate from those of the men we have been attached to—we are neither of us derivative in any way. Do you think that, without fully understanding why, we are both of us culpable?

Kate Pregnant, 1995, etching, 25 7/8 x 20 5/8″. Courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Fine Art.

You never traveled to America, from where I am writing to you now. I’m in my hotel room, lying on my bed, from which I can just see a glimpse of the ocean. There is a notice on the door with instructions about what to do if there’s an earthquake.

I know how you and I both suffer terribly from homesickness, so this feeling may have been what prompted me to communicate with you. You always said that one doesn’t get to heaven in twos and threes, one can only get to heaven alone. But doesn’t being away from home intensify this loneliness so that it’s almost unbearable? Not that either of us has ever properly had a “home” in any consoling sense: the homes we lived in as children never felt like home. When did you become aware of this feeling of rootlessness? For me, this sensation seems to be bound up with my identity. And stillness, of course. I have never been able to understand why people are so restless.

It isn’t restlessness that brings me here, or even curiosity. I am impelled to come for the sake of my paintings. I am having an exhibition here, in California, organized by a man who has helped me with my career. Here is one of the differences between us—you would never have used the word career. Painting, for you, was always a vocation. It is for me as well, but I am more ambitious than you, more organized and driven. These aspects of my nature may have surprised this American man who has helped me so much. He used to refer to me as “a very patient woman,” but I am sure he was thinking of you, really. This is the third exhibition in America that he has dreamed up for me. The first was just over three years ago, in New York.

New York frightened me. Before I went, people assured me that it would seem very familiar because I would have seen it in so many films. But actually it had seemed the most alien place I had ever encountered. I was only there for four days. I arrived in a heat wave; the weather broke on my last day: in a torrential downpour accompanied by apocalyptic thunder and lightning. New York seemed primeval and everything uncertain, as if the skyscrapers and towering buildings were built on sand, not rock, and the whole fabrication could collapse and there would be left just the howling emptiness of a barren, uncultivated land. I hardly dared go out of my hotel room and I lived only on room service. I ventured out to the Frick Collection and found consolation in Rembrandt’s great masterpiece: his Self-Portrait dressed in gold, a postcard of which I keep on the shelf in my studio in London. I looked into his shrewd, kind, knowing eyes and felt more grounded suddenly. It made me aware of the urgent importance of the language of painting—this subterranean language that speaks most powerfully to lost souls.

The second time I went to America was to Yale. It had been snowing when I arrived. My experience of being abroad was partly soothed by the subduing presence of snow. But it was really the fact that the gallery, the Yale Center for British Art, owns such a great body of work by you. Your paintings appeared to me like essential fragments of a life blown over the ocean like rose petals in a storm: delicate, broken, unfinished, yet intact and suggestive of a secret, perfumed world, a guarded, haloed world, a sheltered rose garden. You weren’t interested in the efforts of John Quinn, the enlightened and influential American patron of artists and writers, to make presentations of your work in America. You guarded yourself against any intrusion. And, for this reason, you were able to make these silent evocations of your spirit, of your soul. It had seemed a miracle to me to see them here because they looked so fragile. But they have the tenacity of seeds that flourish wherever the wind blows them.

I have been invited to talk here in Los Angeles about the group of seven paintings of mine on show in the Huntington Museum, which, among many treasures, also houses several paintings by John Constable. The director asked me to speak about how I feel that my paintings of water and sea connect to Constable’s work. I said that although Constable and I often rely on nature as our subject, my paintings from water differ to some extent from his because I only started to paint water as my mother was dying, and have continued to do so after her death. My water paintings are about grief. I said that I hope one day to stop painting water.

Let me tell you what it is like here. The hotel I’m staying in is very beautiful. It is big and square and made out of solid stone that, though gray, has a sort of blush as if it is constantly reflecting a sunset over the ocean onto which it is facing.

On the first morning I decided to walk on the beach, crossing the track where an army of joggers was pounding along continually, to the water’s edge. The light, though overclouded, possessed an opalescent intensity; it was like seeing a blazing fire through gauze. The air was milky and very still. I watched the funny little birds that bounced along the shoreline. I had seen hummingbirds in the bushes outside my hotel window—I had watched them from my bed as I drank my first cup of tea. I noted that not one single bird or tree or flower was the same as in England.

I stood at the ocean’s edge and watched the lapping waves. Then, as the waves continued to gently break onto the shore at my feet, I thought about Charlotte Brontë’s book Villette. I know you must have read it, too. There is an undertow of sadness throughout, like a low murmur that gradually gets louder and more intense until it threatens to drown out the narrative and break up the rhythm of the plot. On the last page, Lucy Snowe is waiting in her bedroom above a classroom in Brussels for her beloved, Monsieur Paul Emanuel (her “Maître,” as you always called Rodin), who is traveling home to her from America. A storm is raging outside her window. She is restless and paces up and down; she is waiting, perhaps forever waiting, since the ocean across which he is traveling toward her must be impossibly treacherous. The lightning strikes and the storm rages on and Lucy is still waiting. There’s a foreshadowing of Lucy’s fate near the beginning of the book, in the story that the old lady (for whom Lucy is a paid companion) tells her: how she had lost her beloved fiancé, Frank, in a riding accident the day before they were due to be married.

I returned to my room. My window has only an oblique view onto the ocean beyond the hotel car park but I am aware of it as a constant presence. It has a mirage-like quality, quivering, an intimation of light across the expanse of sand. It suggests to me the vastness of nature, of the universe. On this first afternoon, I watched, from my bed, the tiny figures on the beach, black shapes like cloves with vestigial arms and legs, silhouetted against the shining strip of water.

As the evening light intensified into a final flaring, I decided to venture out again. I hadn’t been able to sleep. Outside, there was a clarity to the light that was quite different to anything I had experienced in England, where there is always a blurred halo around every form. Here, it was as if some lens had been wiped clean and every outline was distinct. I felt closer to the outer air and the stars. Sounds traveled more keenly too. Three boys were calling to each other and their voices were without echo. I walked along the water’s edge. The waves on this ocean followed each other in straight, uninterrupted lines, no unruly overspilling before the whole straight unbroken wave came cleanly down onto the shore, which stretched in both directions as far as the eye could see. The foam trimmed the water’s edge and clung neatly to it, never flooding too far into the sand. There was a clear demarcation between land and water.

Now, when I look out the window, I see that the weather has changed. A thin rain is falling steadily. I have arranged for a car to collect me from my hotel and drive me to the Getty Villa, which is situated further along the coastline. The driver is an elderly man who alarms me by fiddling constantly with switches and knobs on the dashboard. I realize, with dismay, that he is trying to locate the windshield wipers. The glass is becoming opaque with rain. Eventually he manages to turn the correct switch and the view opens up to reveal a heaving ocean to the left of the highway, lit by a brooding sky. The museum stands on a hill surrounded by towering pine trees. I get out of the car. I arranged for the driver to wait for me. I breathe in the air, which is saturated with pine and herbs from the immaculate herb gardens. The fragrant rows of thyme and sage and marjoram are punctuated with pools filled with ornamental fish.

Inside the Getty Villa are ancient statues and paintings from Greece and Rome. They seem like captive spirits waiting to be freed from their cages of stone and paint. I cry in front of a battered stone carving, titled Elderly Woman, of the face of a woman still beautiful in her endurance: she has a peaceful air as though she is saying that all will be well despite the ravages of time. She is probably only in her mid-fifties, younger than me.

You lived to be only sixty-three. I dread real old age. I am fifty-nine. I think of my mother and all the pain she suffered towards the end, and then the dementia that gradually carried her off into an unreachable place until her death, age eighty-seven.

I think of the unfinished sculpture Rodin did of you. You were in your late twenties then. It must have been a very difficult pose to keep, with one leg raised onto a plinth, your neck stretched out and your lowered head tilted at an angle. You look as if you are consciously being patient, like an animal lowering its humble head so that its master can put the harness over it.

I return to the car and the driver takes me down the hill, along a winding road bordered by immense trees, to a café built on a pier that stretches out into the ocean. I stand by the railings; the waves are crashing against the stilts of the terrace. I could reach down and touch the water with my hand. I need to stand here and look at the steady breathing of the waves, without even thinking, so that the disturbance in my heart can subside.

***

I am back in my hotel room now. I have just had my first cup of tea. Again I didn’t sleep. It is my last day in America, and my flight to London leaves this afternoon. I need to pack and prepare so I will have to finish this letter now, dearest. I will write to you again when I’m home.

With a handshake (as Vincent van Gogh used to say, on signing off a letter to his beloved brother, Theo),

Celia

Breaking, Santa Monica, 2019, oil on canvas, 42 x 40″. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro.

February 22, 2019

Great Russell Street, London

Dear Gwen,

I was looking at a book of paintings by you just now. I turned to the catalog at the back. The first reference is to an oil painting of your sister Winifred, “probably painted in 1895.” The text goes on to say that Winifred became a violin teacher in California, where she married a pupil of hers. I think about how much you must have yearned for her. I don’t know how I could live if my sister Kate emigrated so far away from me.

Soon after my return from Los Angeles, I prepared my canvases for two new seascapes. I hadn’t made studies of the sea while I was there but the light—the particular visionary light—haunted my imagination.

I made a ground of Payne’s gray, Vandyke brown, and Naples yellow by squeezing these colors onto my canvases. I then tipped on Sansodor, an odorless paint thinner that I’d begun to use as a replacement for turps. Until a few years ago, when I opened the door to my flat the smell of turps was overpowering. Everyone commented on it. I loved the smell. All my clothes and my hair were saturated with its pungency. I wore the scent with pride, like a saint reveling in her hair shirt. If I lit candles in my front room in the evening, their flames would shoot up toward the ceiling, fueled by the gaseous fumes. But gradually, I found it harder to tolerate and it became difficult to breathe. I had constant sinus pain and headaches. I had to give it up.

I think I used more turps than you did. I poured quantities of it over my paintings if I felt they were becoming too tight or illustrative. Often a new image would rise up miraculously from the resultant drips and disordered paint marks. Something that I could never have foreseen, if I had been controlling the depiction of an image.

But you always had your own delicate disorder: a dress thrown over the arm of a chair, a brown shawl slipping from your shoulders. You had an instinct for ordered haphazardness. In your garden you would have let the weeds grow naturally among the flowers, though you would have made sure the weeds didn’t choke the other plants. You would have grown lavender and alyssum in the borders. And violets, your favorite flowers.

In preparing my canvases, I shift the paint, drenched in Sansodor, around them, using whatever ragged scraps of material come first to hand, so that the whole surface is equally covered in luminous gray brown. Every item that strays into my studio, every bath towel, eventually becomes a paint rag.

I need to leave the canvases to dry now.

The first marks I make on the canvas suggest movement: the horizontal lines of the waves, the upward lift of the sky, the red-and-gold clouds breezing toward the top right-hand corner and beyond. The sunset of the evening of my arrival in Los Angeles is in my mind, but I am not working from memory. I am a slave to the demands the painting is already making on me. The sound of the waves is in my mind, too. My paint marks weave in this movement so that, when I step back from the canvas, I can see that the water is beginning to have a life of its own, quivering and shifting the longer I look at it.

The painting comes about very easily and freely. I am still energized by the newness of my recent experience in America and some of this wonder makes its way into the painting, which I title simply Santa Monica.

As soon as I have finished it, I start on the second canvas. The overclouded, gauzy light of my third day in California is what I want to convey now. The sky broods, hiding a blazing sun that remains concealed. The painting builds up like a covered pot of milk on a stove, boiling over when the waves break onto the shore in a luminous, frothing band of bright white light. I title this one Breaking, Santa Monica.

Pembrokeshire and Brittany were the coasts that you spent most time in. Your memories of the sea were filled with a bracing wind, the horizon meandering as if warped by the waves and the wind. There were no straight lines, as there are between the sea and the shore in California. You would have to understand that, when you looked at my paintings.

I am suddenly tired, dearest. I will write again soon.

With a handshake,

Celia

Celia Paul’s work is in the collections of the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery (London), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her major solo exhibitions include Celia Paul, curated by Hilton Als, at the Yale Center for British Art (2018) and the Huntington Art Museum, San Marino, California (2019); and Desdemona for Celia by Hilton at Gallery Met, New York (2015–16). She is the author of the memoir Self-Portrait (2020). Celia Paul: Memory and Desire, is at Victoria Miro, London from 6 April–7 May 2022.

This is adapted from Celia Paul’s forthcoming book, Letters to Gwen John, which will be published by New York Review Books on April 26, 2022.

March 1, 2022

Redux: Be My Camera

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

When Edward Hirsch spoke to Susan Sontag, in between her trips to Sarajevo, for a 1995 Art of Fiction interview, he noted that her work seemed “haunted by war.” She said, “I could answer that a writer is someone who pays attention to the world.” This week, we’re rereading a poem by Claribel Alegria and a story by Nadine Gordimer, looking back at a portfolio of the writer Ryszard Kapuściński’s photographs, watching the news, and considering what it means to pay attention.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

INTERVIEW

The Art of Fiction No. 143

Susan Sontag

I suppose it could seem odd to travel to a war, and not just in one’s imagination—even if I do come from a family of travelers. My father, who was a fur trader in northern China, died there during the Japanese invasion—I was five. I remember hearing about “world war” in September 1939, entering elementary school, where my best friend in the class was a Spanish Civil War refugee. I remember panicking on December 7, 1941. And one of the first pieces of language I ever pondered over was “for the duration”—as in “there’s no butter for the duration.” I recall savoring the oddity, and the optimism, of that phrase.

From issue no. 137 (Winter 1995)

PROSE

Face from Atlantis

Nadine Gordimer

A flashlight picture, taken in a night club. Stefan holds up a glass of champagne, resigned in his dinner suit, dignified in a silly paper cap. New Year’s in Budapest, before Hitler, before the war. Can you imagine it? Eileen was fascinated by those photograph albums and those faces. Since she had met and married Waldeck in 1952, she had spent many hours looking at the albums. When she did so, a great yawning envy opened through her whole body. She was young, and the people pictured in those albums were all, even if they were alive, over forty by now. But that did not matter; that did not count. That world of the photograph albums was not lost only by those who had outgrown it into middle age. It was lost. Gone. It did not belong to a new youth. It was not hers, although she was young. It was no use being young, now, in the forties and fifties. She thought of the green albums as the record of an Atlantis.

From issue no. 13 (Summer 1956)

POETRY

Documentary

Claribel Alegria

Come, be my camera.

Let’s photograph the ant heap

the queen ant

extruding sacks of coffee,

my country.

From issue no. 108 (Fall 1988)

ART

Roadsides

Ryszard Kapuściński

From issue no. 180 (Spring 2007)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

February 26, 2022

In Odessa: Recommended Reading

Potemkin Steps, Odessa, Ukraine. Photo: Dave Proffer

“Buried in a human neck, a bullet looks like an eye, sewn in, / an eye looking back at one’s fate.” So writes the Russian-language Ukrainian poet Ludmila Khersonsky, born in Odessa. Now, President Putin claims he is sending troops to Ukraine in order to protect Russian speakers. What does Ludmila think about Putin?

A small gray person cancels

this twenty-first century,

adjusts his country’s clocks

for the winter war.

Putin is sending troops, and the West is watching as Ukrainian soldiers, and even just young civilians, take up guns in the streets to oppose him. There is no one else to help them. I’m rereading Ludmila:

The whole soldier doesn’t suffer—

it’s just the legs, the arms,

just blowing snow

just meager rain.

The whole soldier shrugs off hurt—

it’s just missile systems …

Just thunder, lightning,

just dreadful losses,

just the day with a dented helmet,

just God, who doesn’t protect.

I first met Ludmila in Odessa in 1993. She tried to teach me English. I was a terrible student. These days, she writes to me to say that she hears explosions outside her windows. She is placing batches of newspapers on the windowsills, to fortify them. She is writing poems.

Ilya Kaminsky is the author of Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press) and Dancing In Odessa (Tupelo Press). His awards include the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Whiting Writer’s Award, the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Metcalf Award, Lannan Foundation’s Fellowship, and the NEA Fellowship. His poems regularly appear in Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize anthologies. Read his poem “From ‘Last Will and Testament’” in our Winter 2018 issue.

The translations of poems used here are by Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco, Valzhyna Mort, and Katherine E. Young.

February 24, 2022

The Review’s Review: Real-Time Historicization

The K’alyaan Totem Pole of the Tlingit Kiks.ádi Clan, erected to commemorate those lost in the 1804 Battle of Sitka; photograph by Robert A. Estremo, copyright © 2005. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This week, as Russia formally invaded Ukraine, I thought of the Battle of Sitka, another military operation Russia initiated against a smaller autonomous stronghold, in this case the Kiks.ádi, a clan of the Indigenous American Tlingit people. I learned of the battle in Vanessa Veselka’s essay “The Fort of Young Saplings,” which was published by The Atavist in 2014 (I’d recommend the version printed in their Love and Ruin anthology). Both the Kiks.ádi and the Russians claim that they won the battle. Veselka’s essay investigates the problems this battle raises regarding historicization, the interpretation of events, and national identity formation. (She also questions whether a crucial Tlingit tactic of the Battle of Sitka influenced General Mikhail Kutuzov’s withdrawal from Moscow during the War of 1812, a series of events Tolstoy dramatized in War and Peace.)

The Russians began colonizing Alaska in the 1740s. As they expanded their empire, they trespassed onto Sitka, Kiks.ádi ancestral land. In 1802, the Tlingit, who’d long resisted Russian forces, initiated an attack to draw the invaders back, claiming a Russian fort in the process. “K’alyaán,” Veselka recounts, “a great Kiks.ádi warrior, struck the initial blow, killing a blacksmith and taking his hammer.” Two years later, the Russians returned to Sitka and battled the Kiks.ádi, including K’alyaán and his hammer. The Tlingit built Shis’gi Noow, which translates to “the fort of young saplings,” to ward off the Russians, but ultimately retreated from the fort. Veselka writes:

On the first day of combat, the Russians were soundly defeated … For the next four days, the Tlingit fort was bombarded from the sea by the Neva as emissaries went back and forth. Both sides raised white flags, sometimes simultaneously. At the end of the sixth day, the Russians were in the fort and the Tlingit were in the forest. On these facts everyone agrees.

But the more I learned of the battle, the shakier the claim of a decisive Russian victory seemed. The battle was not followed by an influx of Russian trading posts. The Tlingit did not become slaves, as had other tribes. Although the Kiks.ádi abandoned their position, they did not exactly flee, but instead made an organized retreat, covering their people with a rear guard and taking up a new position on the straits. From there they launched an effective trade embargo to cut off the transport of fur to Russia. The following year another Russian trading post fell to the Tlingit in Yakutat and was permanently abandoned.

The retrospective logic seems to be that since the Kiks.ádi do not run the United States today, they must have lost to the Russians in 1804. Native wins are irrelevant. Native defeats are final. The Russians would inevitably prevail, and if not, it didn’t matter anyway. The Battle of Sitka, the lost posts, the embargo on the straits—these were details.

According to Niall Barr, an expert on European military history, martial victory is typically understood as a fairly simple affair: whoever vacates the fort at the end of the day has lost. But Veselka wonders: “How big is that fort? And how long is that day?”

Like many smart interrogations into history, “The Fort of Young Saplings” is a great detective story, though it subverts any of that genre’s narrative formulas and traditional notions of closure. Like Saidiya Hartman, Veselka interrogates the holes in historical archives, looking beyond facts and figures to both excavate and extrapolate the narratives excluded from canonized accounts. The essay reminds me that the disregard Russia has for the autonomy of the smaller countries it neighbors, including Ukraine and its Crimean peninsula, which Russia illegally annexed in 2014, is part of an ongoing process of colonization that began centuries ago and has never really ended. It’s obvious, but bears repeating: imperialist superpowers, including Russia and the United States, usually begin their dominion by attacking Indigenous nations.

As concerns this year’s nascent Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the war of interpretation has already begun. Earlier this week, Putin gave a speech distorting Ukrainian history: “Modern Ukraine was entirely and fully created by Russia, more specifically the Bolshevik, communist Russia,” he said, echoing a five-thousand word essay he published on the subject last summer. Now, news outlets report that President Volodymyr Zelensky has banned Ukrainian males aged eighteen to sixty years old from leaving the country, suggesting conscription is imminent. Ukraine’s own mythologizing has begun as well. Already there is folklore spreading about “The Ghost of Kyiv,” a Ukrainian fighter pilot who is supposed to have taken out six Russian war pilots during dogfights. Social media users uploaded video of what appears to be a MiG-29 jet soaring through the skies over several Ukraine sites. Although their origins and contexts are very different, I wonder if this—likely apocryphal—“Ghost of Kyiv” might function like the very real K’alyaán did for the Kiks.ádi, as an anti-imperialist national hero. Do Ukraine’s landlocked men really believe in him, or does he represent what they can’t do: move freely? What’s old is new again. As in 1804, Russian oligarchs may not totally get their way; embargoes and sanctions are in play. The roadways are clogged, as Ukrainians flee attacks from land, sea, and air; another retreat is underway. Kyiv is at serious risk of being seized. Inspired by Veselka’s incisive questions about the Battle of Sitka — “How big is that fort? And how long is that day?” — I pose other inquiries about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: When does the day begin? And how far do the boundaries of the fort extend to brains, and from brains, into forms of storytelling? —Niela Orr

I’m in the middle of reading Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm by Dan Charnas, one of the most extraordinary music books I’ve ever read. It is a biography of the genius hip-hop producer J Dilla, who died in 2006, after, as the book convincingly argues, changing the way music listeners hear rhythm. Dilla figured out how to imbue sampled beats with the kinds of imperfections and happy accidents that make music played by humans so wonderful. The book is also a thorough, though concise and highly readable, history of rhythm itself in American music, tracing its journey from European classical music through ragtime, blues, jazz, funk, rock, and hip-hop, explaining, sometimes using helpful charts and diagrams, how we hear time. If you care about music and want to experience it more deeply, even if you’re not a hip-hop fan, this book is full of revelations. —Craig Morgan Teicher

February 22, 2022

Photographic Neuroses: Alec Soth’s A Pound of Pictures

Alec Soth, Quan Am Monastery. Memphis, Tennessee, 2021, archival pigment print, 24 x 30″. All images copyright © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

On his travels across the United States, the photographer Alec Soth likes to visit Buddhist temples and sometimes to ask the monks if photography, with its “desire to stop and possess time,” is antithetical to their teachings. He reports that the response is often some variation on “No, I love taking pictures!” After one such interaction in Connecticut, he found that the monk in question had even tagged him in a photo on Facebook. The average American monk, it seems, isn’t concerned about whether the photographic impulse may be a neurotic one born of upādāna, or worldly attachment. Soth, though, clearly is.

Since he burst onto the scene in 2004 with his now canonical book Sleeping by the Mississippi, Soth has been one of the great visual chroniclers of the American condition. His work, armed with Walker Evans’s docu-formalism, fights William Eggleston’s “war with the obvious”; it has always incisively captured the country’s psychosocial landscape, examining who we are and how we feel, collectively. But his new project, A Pound of Pictures, takes a turn inward. Here, America as Soth finds it serves less as a subject than as a vehicle to examine the photographic medium itself, and his relationship to it. The book and the exhibition play on our desire to memorialize, to preserve pieces of experience. Many of these images contain another photograph somewhere in the frame—there are, by my count, seven pictures of people taking pictures—and interwoven throughout are a handful of portraits of well-known image makers: Sophie Calle, Duane Michals, Nancy Rexroth.

When Soth began this body of work, he wasn’t intending to make photographs about photographs. His original plan was to follow the route of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train, “in an attempt to mourn the divisiveness in America.” But the project, he writes, felt “lifeless,” lacking the fundamental sense of mystery that makes his best work buzz. So, he abandoned the approach, trying to think less and feel more, allowing his camera to be oriented by an inner photographic compass—the instincts he doesn’t always understand but has learned to trust. The result is A Pound of Pictures, a project that is political only in that it asks a people mindlessly producing billions of images every day: What are we doing? And why are we doing it?

I spoke to Soth over the phone just after touring his exhibition at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. I wanted to ask him some similar questions about the medium he has devoted his life to, and to push him on its efficacy and purpose. But Soth gives no definitive answers, either in our interview or in his photographs: both are structured less by conclusions than by his wandering, wondering curiosity. A selection of photographs from A Pound of Pictures follows the interview.

INTERVIEWER

This project is titled A Pound of Pictures. What was it that appealed to you about thinking of photographs not as weightless visual data but as tangible objects?

SOTH

During the pandemic, on a whim, I created a timeline of the history of photography. I laid it out on a sheet of paper. Then I overlaid my career as a photographer on it and saw that my whole early developmental stage took place in a purely analog world. Inkjet printing arrived right as my career took off. And then, during some of my key years, the internet as we know it came along. I wanted to mark this transition. It’s not that I believe it’s important for things to be physical rather than digital, but I wanted to address my own compulsion towards the physical.

INTERVIEWER

I know that you don’t throw away photographs, and that you collect vernacular photos in pretty large quantities. But I was surprised to hear that you even have trouble deleting images off your phone. Why do you think that is?

SOTH

The way I learned to think of the medium of photography was that the whole point of taking a picture was to preserve a moment. So, throwing away a negative? I can’t conceive of it. Even damaged negatives, ones with giant light leaks, I don’t throw away. I recently read The Night Albums by Kate Palmer Albers, and learned that in the very beginnings of photography, for the first twenty years or so, they struggled to make photographs permanent. Once that was achieved, permanence became the point, but it doesn’t have to be that way. This new world of how we communicate with pictures is in some ways a return to that beginning: the pre-permanent state of photography.

INTERVIEWER

So, for you, throwing away a photo is counter to the very impulse of taking a photo?

SOTH

I sometimes use this analogy: photography is like fishing. Why can’t we all just catch and release? Somehow that seems like a more ethical form of photography. Like, we could go out with binoculars instead of a camera and just look at the world. Why do we have to pin it down?

INTERVIEWER

You could just look through your viewfinder all day and never click the shutter.

SOTH

Exactly. A hunter, on the other hand—I’m not a hunter, by the way—probably wouldn’t wait out in a blind for five hours in the cold unless there was the possibility of taking down the deer. I’m not mounting and hanging every fish I catch, but I do feel the need to save all of them.

INTERVIEWER

A Pound of Pictures made me want to revisit Sontag and think about what motivates us to take pictures. Walking around the exhibition and spending time with the book, I began to feel acutely aware of the fact that the photograph’s promise to freeze time, to make permanent what is ephemeral, is a false one. Do you think photography is an effective way to memorialize a moment? Or is it a noble fool’s errand, something we do to cope with our mortal inability to hold on to anything?

SOTH

I don’t think it’s terribly effective in that way, no. But I do think it’s effective in getting me out the door, in experiencing the world in a way that I wouldn’t without the excuse of photography. I’m always battling cynicism. I noticed this when I started giving lectures to students. I would talk about how there are too many pictures in the world and then realize, This student just exposed their first roll of film and processed it in the darkroom, and they’re super excited about it! Why am I shitting on their experience? So, I’m always trying to get back to that original joy, the joy an amateur has.

INTERVIEWER

Are you talking about “beginner’s mind”?

SOTH

Yes. The thing I want to communicate most in this book is that original enthusiasm. I’m trying to access it again and again.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve also compared photographs to flowers in your attempt to battle cynicism while making this project.

SOTH

It’s a funny thing. People never say, There are too many flowers in the world. Enough is enough! No, we just enjoy the bounty of flowers.

INTERVIEWER

That analogy between photographs and flowers strikes me as similar to Walt Whitman’s comparison of his pages to leaves of grass. Can you talk about Whitman’s influence on this work?

SOTH

I think it’s important to start with the fact that I’m nothing like Whitman. I’m no Ginsberg, I am nothing like those personas of abundance, but I do find tapping into that kind of energy helps my neuroses greatly. Whenever I read Whitman, I feel a little better about the world. This project had its origins in my thinking about Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War. Whitman was able to write about that period in such a beautiful, open-minded way. Frankly, I wouldn’t have been able to do that. I couldn’t photograph Trump’s America in that kind of spirit. That’s where I sort of got into trouble with this work. But what I was able to do is tap into celebrating one’s own vision, one’s own experience.

INTERVIEWER

In the book you write that attention might be the opposite of neuroticism. How so?

SOTH

We tend to use the word neurotic in a flippant way, but once I understood the word’s more clinical definition, I realized, Oh, that’s me. And I accept that, but it can spin out of control, and the way I’ve found to regain some sort of equilibrium is through directing my attention outward. For example, I’ve always felt like playing ping pong was a balm for my neuroses because all my attention was on the ball and the game. It offered me relief from my own brain. I feel that way when I’m photographing, when I’m in the experience of looking at something intensely. I mean, even people taking a picture of their food—for a brief second, they’re really paying attention.

INTERVIEWER

I always imagined that people’s need to photograph their food was actually a product of their neuroses.

SOTH

Well, maybe the whole photographic enterprise is born out of some neuroses, because we’re thinking about the fact that we’re going to die, and we feel we’ve gotta, like, pin this shit down. But the moment of actually making the photo offers a brief respite from that.

INTERVIEWER

This project, more so than your previous work, flips its attention around, focusing less on the world as you find it and more on yourself and the medium. What prompted this shift?

SOTH

I heard Philip Roth or some writer talk about how you reach a certain point where you become more influenced by your own work than the work of your influences. I still hold on to my early influences, but these days I’m mostly thinking about my relationship to photography. I think it’s just a natural progression that unfolds as you do something for a long time.

INTERVIEWER

A Pound of Pictures, with its self-reflective mode, almost feels like the end of something for you. What is it the beginning of?

SOTH

It’s definitely backward-looking, but just because someone writes a memoir doesn’t mean their next project isn’t going to be short stories or something. Right now, the project is done, and I’m in the phase of talking about it. This is the moment in which I allow myself great experimental freedom. I have six months to a year to just try stuff. Now is when I become a beginner yet again.

A Pound of Pictures is currently on view at Sean Kelly in New York, Weinstein Hammons in Minneapolis, and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco. The project’s accompanying book will be published this month by Mack Editions.

Gideon Jacobs is a writer who has contributed to The New Yorker, Artforum, The New York Review of Books, BOMB, Playboy, VICE, and others. He is currently working on a collection of short fiction.

Niagara Falls, Ontario, 2019, archival pigment print, 52 x 65″.

The Coachlight. Mitchell, South Dakota, 2020, archival pigment print, 40 x 50″.

Camera Club. Washington, Pennsylvania, 2019, archival pigment print, 24 x 30″.

Ames, Iowa, 2021, archival pigment print, 24 x 30″.

Naples, Texas, 2021, archival pigment print, 25 x 20″.

King & Sheridan, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2021, archival pigment print, 52 x 65″.

Abandoned House. Coahoma, Mississippi, 2021, archival pigment print, 24 x 30″.

Julie. Austin, Texas, 2021, archival pigment print, 30 x 24″.

White Bear Lake, Minnesota, 2019, archival pigment print, 40 x 32″.

Redux: Literary Gossip

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

Photo copyright © Laura Owens.

In honor of the longtime friendship between BOMB and the Review, we’re offering a bundled subscription to both magazines until the end of February. Save 20% on a year of the best in art and literature—and for your weekly archive reading, a selection of authors that the two of us have each published over the years.

Interview

Gary Indiana, The Art of Fiction No. 250

Issue no. 238 (Winter 2021)

I was desperate to write a novel, but I didn’t have a story. Whenever I tried to write fiction it was all about my own inner bullshit. Writing about films and architecture and books was never the end point of what I wanted to do, but it forced me to get outside my own head, to describe physical objects and action. And then somebody handed me a story.

Fiction

Second Dog

By Kate Zambreno

Issue no. 228 (Spring 2019)

When I think about getting a second dog, I think about what we might name the dog. It’s exciting that we won’t have to disguise naming the dog after a writer or artist. Our dog is named Genet, and I fantasize about a little terrier named Violette Leduc, so if our Genet ignores her or humps her, I can pretend I’m enacting some literary gossip, as Violette Leduc always abjected herself to Genet in her desire for his friendship. With babies, there is more pressure to at least disguise one’s pretensions.

Poetry

Learning Persian

By Solmaz Sharif

Issue no. 230 (Fall 2019)

deek-teh

deek-tah-tor

behn-zeen

dee-seh-pleen

eh-pe-deh-mi

fahn-te-zi

mu-zik

bahnk

mah-de-mah-zel

sees-tem

vah-nil

vee-la

vee-roos

ahm-pee-ree-ah-lizm

doh-see-eh

oh-toh-ree-te

Art

Walton Ford and Ryan McGinley

By Waris Ahluwalia

Issue no. 201 (Summer 2012)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

February 17, 2022

The Review’s Review: Ye’s Two Words

A red planet in the foreground with a green planet in the distance, set in a starfield. Image courtesy of Adobe Stock.

In the wee hours of this morning, Ye shared a flurry of Instagram posts. There were videos advertising his proprietary Stem Player, which he claims will be the only place fans can listen to DONDA 2, the album he plans to release next week. “Go to stemplayer.com to be a part of the revolution,” he wrote. The Stem Player, which allows users to remix music by manipulating stems, or the individual, elemental parts of a song, is a disc covered with what looks like semitranslucent tan silicone, featuring blinking multicolored lights that correspond to the tempo and other aspects of a currently playing track. Its design is of a piece with Ye’s Yeezy aesthetic: earth tones complemented by bright hues, like a Star Wars scene set in Tatooine. His posts recall George Lucas’s series in their narrative messaging as well: Ye highlights the battle between an evil empire—in this case, the music and tech industries—and an intrepid revolutionary, himself. “After 10 albums after being under 10 contracts,” Ye explains, he is ready to control the means of distribution. “I turned down a hundred million dollar Apple deal. No one can pay me to be disrespected. We set our own price for our art. Tech companies made music practically free so if you don’t do merch sneakers and tours you don’t eat … I run this company 100% I don’t have to ask for permission … I feel like how I felt in the first episode of the documentary.”

“The documentary” is jeen-yuhs: a Kanye Trilogy, a nearly five-hour bildungsroman that premiered at Sundance in January and is distributed by Netflix. Directed by the filmmakers Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah, who made Ye’s first music videos, jeen-yuhs is shot in what appears to be vibrantly colored 8 mm—something of Coodie & Chike’s trademark—and is narrated by Simmons, who quit his job as a comedian and public-access host in Chicago to follow his friend’s journey. It’s a culmination of over twenty years of documentation and hundreds of hours of footage. Consequently, the film plays like a very long, intimate home video.

In the trilogy’s first part, which premiered on February 16, it’s the early aughts: Ye is hustling in New York City and working on what will become his 2004 album, The College Dropout. This is the portrait of an artist as a twentysomething young producer, a successful beat maker struggling to be taken seriously as a rapper. He goes into Roc-A-Fella’s offices and plays his music for busy A&R and marketing professionals, who half listen in between phone calls. We see him playing his instrumentals for other rappers, driving around New York delivering tracks, taxiing through the city with CDs of beats, waiting for his career to take off. We see him waiting in the wings of another rapper’s concert anticipating his chance to get on the mic, and then buying a porn mag from a newsstand. We see the empty refrigerator in his Newark bachelor pad. We see him spending time with his mother, the late Dr. Donda West, in her Chicago apartment. Dr. West’s confidence in her son’s abilities is touching; while watching Ye and his mom rapping one of his early songs in her kitchen one late night, I had to wipe my eyes. In this film, we see Ye built bit by bit; we see his stems.

One of today’s predawn posts was an excerpt of a track called “Fuck Flowers”: a video of the Stem Player playing the song in the dark, its blinking nodes like a pulsing beacon cast from a lighthouse, beckoning insomniacs, those in other time zones, and workaholics to come and listen. The device’s undulating light show matches the rhythm of Ye’s recent Instagram activity, which has functioned as a rapidly changing post-and-delete diary of his thoughts. For the past few weeks, he’s been sharing dozens of posts, which vacillate between harassing his estranged wife, Kim Kardashian, and her boyfriend, Pete Davidson; promoting his new album; and expressing a desire to restore his marriage. Beginning with 2016’s The Life of Pablo, an album notorious for its ever-evolving tracklist and sequencing, Ye has been editing his art to fit his moods. At the same time as he started live-editing his art, he began live-tweeting his thoughts. In 2018, for example, he ecstatically expressed his ideas about Donald Trump’s “dragon energy,” and his emoji skin-color preferences. Ye’s impulse to share has only intensified. On Sunday, he wrote, and subsequently deleted,

HERE’S SOMETHING I HAVE TO DISPEL MEANING REMOVE THE SPELL THAT PEOPLE ARE UNDER WHY DOES A MEDIA OUTLET GET TO POST 20 TIMES A DAY BUT IF I POST THAT AMOUNT THERE’S SOMETHING WRONG ISN’T INSTAGRAM OUR OWN PERSONAL MEDIA PLATFORM? … I LOVE BEING IN CONTROL OF MY OWN NARRATIVE “I FEEL KIND OF FREEEEEE”

The contrast between Ye’s impetuous Instagram dispatches and the thoughtfully arranged, two-decades-in-the-making jeen-yuhs is a fruitful artistic juxtaposition: between a hastily assembled chronicle and a more reflective composition. We can see two chronologies in motion, two contradictory but complementary records in play, suggesting distinct, but overlapping destinies—hinting, like Tatooine’s binary sunset, at elliptical experiential timelines. Holding the two together means witnessing a pleasant anachronism, as sweet as Ye’s old sped-up soul samples. “We get a good juxtaposition now in this film between the two lenses,” says Chike Ozah, referring to balancing the media’s critical view of Ye with a more empathetic one, in an interview with Netflix. On the College Dropout classic “Two Words,” Ye plays with the power of contrasting pairs: it features Freeway, who was then a hard-core street rapper, and Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey), the Toni Morrison–quoting indie-rap darling. Throughout the song, the featured artists use the refrain “two words” before juxtaposing sets of images. Ye begins his verse by establishing the scope of his playground—“Southside, worldwide”—which is both local and cosmopolitan. In light of the duality offered by his social-media narrative and the documentary—a long view alongside a short one—I wonder what words he’d use to describe himself now. For me, two words come to mind: recording artist.

In one jeen-yuhs scene, filmed with Ye and Dr. West at his childhood home, the musician says, pointing at the space where a full-length mirror used to be, “I used to just practice in front of it.” It’s not hard to imagine; in several scenes, Ye flexes for the camera, posing and preening. Oh, how things have changed. For Ye, these days, mugging in front of the camera is like mugging in front of a mirror. At the beginning of the film, a Roc-A-Fella A&R rep asks him, “You still doing your documentary? I thought it’d be finished.” Ye replies, “It’ll never be finished.” —Niela Orr

I knew that Joachim Trier counted Arnaud Desplechin’s 1996 film My Sex Life … or How I Got into an Argument as an influence—he said as much at a recent talk at Lincoln Center—but was delighted by just how deeply Trier’s new movie, The Worst Person in the World, reminded me of the former when I finally saw it last week. The Worst Person in the World, like My Sex Life, is a freewheeling exploration of one’s early thirties—that delicate age at which actions do indeed begin to have consequences but it’s still fun to occasionally blow up one’s life in a moment of boredom. From the voiceover to the adultery plot points to the menstrual-blood shower scene, Trier borrows freely from Desplechin, though he swaps the gender of his main character, Julie. The result is a witty, realistic look at the highs and lows of finally growing up, and might include the best sex scene I’ve ever seen—it’s certainly the best sex scene in which the characters don’t even touch each other. —Rhian Sasseen

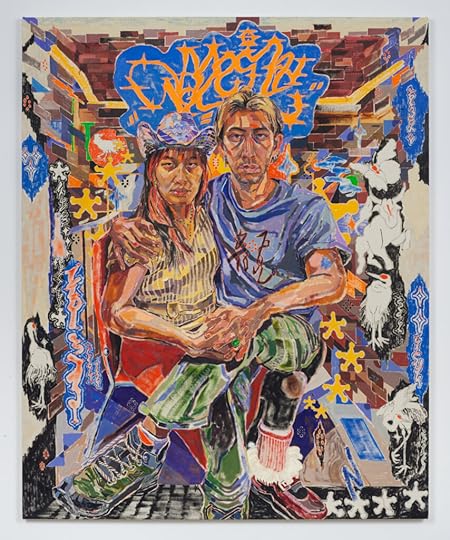

I first encountered the work of Oscar yi Hou—now an upcoming solo exhibitionist at the Brooklyn Museum after winning their third annual UOVO Prize—when I saw his A sky-licker relation at James Fuentes Gallery late last summer. The exhibition is a series of portraits, mainly of young Asian people. The subjects, through their various positions of vulnerability, stoicism, solitary ponderance, and mutual affection, stare directly out of intricate, kaleidoscopic frames to meet the eyes of their audience, positioning the viewer such that they take up the gaze that was once held and reciprocated by the artist. This dynamic between creation, creator, and beholder is simultaneously mediated and immediate, spontaneous and reenacted—an experience that is communal but also intensely concerned with the individuality of personhood. Seeing yi Hou’s work amidst a crowd of other twentysomethings fresh into the gallery from a day that had been hot and damp, hopelessly sweating through an outfit I had probably chosen with great effort for the occasion, I was faced with exactly that: the discomfort, the relief, the multiplicity and solitude of the person.

With me at the exhibition were several people who had modeled for the paintings. I saw them as they existed both in the real world and within the complex iconography in which the artist had immersed them: the dragon, horse, and ox of the lunar calendar; ornate lettering reminiscent at once of ancient calligraphic practices and contemporary American street graffiti; golden stars denoting the Chinese flag as much as the classic westerns of old Hollywood. Graceful and precise, these aesthetic references index their subjects as global intersections of past and present, living fulcrums upon which a multitude of dreams and inheritances—fame, beauty, nationhood, belonging—have come through time to balance. Standing before their portraits, sharing with them my reality and the collisions of perspective inherent to it, I felt that transhistorical identity reflected within myself. —Owen Park

Far Eastsiders, aka: Cowgirl Mama A.B & Son Wukong, 2021, signed and dated verso, oils on canvas, 61 x 49 3/8″. Photo by Jason Mandella, courtesy of Oscar yi Hou and James Fuentes.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers