The Paris Review's Blog, page 87

March 25, 2022

On John Prine, Ferrante’s Feminisms, and Paterson

Historical diorama of Paterson, New Jersey, in the Paterson Museum, licensed under CC0 1.0.

Jim Jarmusch’s film Paterson is set in Paterson, New Jersey, the city that is also the focal point for William Carlos Williams’s modernist epic Paterson, a telescoping study of the individual, place, and the American public. Paterson is home to—and the name of—Jarmusch’s hero, a bus driver and a very private poet, played brilliantly by Adam Driver. He lives with his ditzy but extremely loving wife, Laura, who is obsessed with black-and-white patterns and becoming both a country-and-western singer and Paterson’s “queen of cupcakes.” Like much of William Carlos Williams’s poetry, the film is a celebration of ordinary life. Every day in Paterson’s life is the same. He wakes at the same time each morning, kisses his wife, eats a bowl of Cheerios, goes to work, listens to his colleague moaning about his life, sits in the same picturesque place to have lunch and write his poems, comes home to have supper with his wife, goes to the bar. And he’s not interested in being published. His pleasure is in the writing, and in seeing poetry in the everyday. As Carlos Williams writes: “no ideas but in things— / nothing but the blank faces of the houses / and cylindrical trees …”

One of my favorite scenes in the film is Paterson’s encounter with a little girl who is writing a poem while waiting outside the bus station for her mother and sister. When she reads him some of her work, his response is respectful, tender, and genuine. The whole film is suffused with this gentle respect. The only fly in the ointment is Marvin, Laura’s bulldog, who hates Paterson (perhaps because Paterson leaves him outside the bar when they go on their evening walks?). After Marvin wreaks revenge on his poems, a bereft Paterson visits his usual writing spot. There he meets a Japanese poet and fellow Williams fan, who makes him a gift of a new notebook. “Sometimes empty page presents most possibilities,” he says, before leaving with an enigmatic “Aha.” And Paterson begins to write again. In the midst of the ongoing evils of our time, it is a balm to be immersed in the entirely unsaccharine Paterson. It is a privilege to appreciate how sweet it can be when everything—the good and the ordinary—stays the same.

—Margaret Jull Costa, cotranslator of “Three Sonnets” by Álvaro dos Campos

Close readers of Elena Ferrante may already know that her books draw strongly on seventies Italian feminist theory, as formulated by groups such as the Milan Women’s Bookshop Collective: in the third Neapolitan novel, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the narrator, Lenù, even gives a long, impassioned summary of Carla Lonzi’s essay “Let’s Spit on Hegel.” But the second lecture in Ferrante’s new In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing, translated by Ann Goldstein, describes in detail the influence of the Bookshop Collective’s theories on female friendship (elucidated in their book Sexual Difference: A Theory of Social-Symbolic Practice) on her fiction. In fact, all of the lectures in In the Margins—originally commissioned by the University of Bologna and delivered publicly in 2021 by an actress and a Dante scholar, in an effort to preserve Ferrante’s anonymity—provide new insight into the novelist’s engagement with writers like Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Ingeborg Bachmann, María Guerra, and Emily Dickinson. It’s a fascinating peek into Ferrante’s process, one that opens up intellectual rabbit holes and as many new questions as it answers.

—Rhian Sasseen, engagement editor

The songwriter John Prine died of COVID-19 in April 2020, at the age of seventy-three. He had contracted the virus while touring for The Tree of Forgiveness, his first album of new music since 2005, and one of his best. Prine’s deceptively simple melodies and lyrics were a conduit for a sort of plainspoken mysticism, and I’d long been in the habit of seeing him perform once or twice a year. I still miss him.

His death urged fans to reappraise an album released that same March by another great songwriter, the visionary soul artist Swamp Dogg. Swamp Dogg—born Jerry Williams Jr., in 1942—had invited Prine to sing on two of the album’s tracks. They would be Prine’s final studio recordings.

The two singers had been friendly since at least 1972, when Williams had a minor hit with his arresting version of Prine’s “Sam Stone.” Williams’s aesthetic leans more experimental than Prine’s: in his heyday, he sang tender postapocalyptic sci-fi ballads on records with titles like Gag a Maggot. Still, the affinity between Williams and Prine is audible in their duets, recorded when both men were in their seventies, and when neither knew what the next year would bring.

“Please Let Me Go Round Again” is a classic, comically depressive Swamp Dogg character study: “Oh life, can’t you afford me another chance? / If you let me go ’round again / I’ll build a better mousetrap from a far more better plan.” Williams and Prine are charming, trading lines. It’s a lovely tune. At the end, over a vamp, the two begin to pal around. They start in character:

Williams: I’m scared to bet on myself.

Prine: I’ll bet on you.

Williams: Well, I’ll bet on you. But I done screwed up so much.

Prine: Well, maybe we’ll get a two-for-one. Maybe they’ll give us both another chance.

Williams: At half price.

Prine: We can get a two-headed sweater.

Williams: Yeah! Right!

The exchange doesn’t sound scripted. The laughter and warmth are real. It was “whatever older people call having a ball,” Williams would of the sessions. As the exchange continues, the two drop out of character, speaking sweetly to one another, as if forgetting the microphones. “Hey, man—I want to thank you for that ‘Sam Stone,’ man,” says Williams. Prine replies, “You bet. You got it around to a lot of people, Swamp.” It’s beautiful. Something between them there on record has the power to make the listener feel cared for. Then it’s over. “We were planning on going to his house in Ireland,” Williams said of Prine, in an interview that followed Prine’s death, “and we were going to stay there about a week or so and just write some new shit, you know? His intertwined with mine, you know, the ideas. And it was going to be good, man.”

—Zach Williams, author of “Trial Run ”

March 24, 2022

Conversations to the Tune of Air-Raid Sirens: Odesa Writers on Literature in Wartime

Odesa Monument to the Duke de Richelieu. Photograph by Anna Golubovsky.

This story begins more than thirty years ago, in the late eighties. There are poets working at the Odesa newspapers, many of which are faltering. A publisher visits my school classroom.

“Who would like to write for a newspaper?”

A room full of hands.

“Who would like to write for a newspaper for free?”

One hand goes up—mine. I am twelve.

In the busy hallway of the paper’s office, I meet an old man with a cane, Valentyn Moroz—a legendary Ukrainian-language poet who’s often in trouble with Soviet party officials. He is reading Mandelstam next to me, unable to sit still, unable to read quietly. His voice trembles as he reads a stanza: “Do you hear? Do you hear? This is Mandelstam, this son of a bitch Mandelstam, no one writes better than this son of a bitch Mandelstam. Don’t you know this Mandelstam?”

I don’t.

Moroz stands up. He takes me by the hand and leads me out of the building to the nearest tram station. He recites poems from memory all the way from the office to the station, and then on the tram all the way to his apartment.

I leave there with a bag of books and a handwritten note telling me not to come back next week unless I have read and memorized some of Mandelstam’s poems.

Thus begins my education.

That same year, I meet Yevgeny Golubovsky, a legendary Odesa journalist, when he gives a talk at my school. Moroz makes a point of telling me that Golubovsky was one of the first people to start publishing Mandelstam again after the poet’s final arrest and death in a transit camp in 1938. As the story goes, Mandelstam’s widow, Nadezhda, shared some of his unpublished verses, typed up on thin cigarette paper, with Golubovsky. When Golubovsky vowed to find a way, against all the rules then in place, to publish them, Nadezhda chuckled and nodded her head in disbelief.

And yet he did find a way. That’s the kind of man Golubovsky is.

My family leaves Odesa in 1993. Moroz dies in 2019, but Golubovsky and I remain in touch. In late February this year, when Russia invades Ukraine, his email to me describes air-raid sirens and panic, then concludes, “But now it is calm. It’s a beautiful summer day.”

This is also the kind of man Golubovsky is.

When I ask him how I can help, he replies, “Ah, I need nothing,” and when I ask again what I can do, he sends a quick message back: “Putins come and go. We are putting together a literary magazine. Send us poems.”

Golubovsky is always starting something. Some years ago, he invited a group of literary people of all ages over for tea, and so began Green Lamp, a regular gathering of poets and writers. “As a two-hundred-and-twenty-seven-year-old city, Odesa is still relatively young,” he writes to me,

But more than two hundred of these years took place on the world’s literary map. Writers as different as Lord Byron, Mark Twain, and Pushkin wrote about Odesa. Poland’s national bard, Adam Mickiewicz, lived and taught in Odesa for a while, and wrote about it. The legendary Anna Akhmatova was born here. By the early twentieth century, Odesa already had its own—very diverse and multilingual—literary tradition: Isaac Babel and Yuri Olesha were writing in Russian, Yanovsky and Sosiura in Ukrainian, Sholem Aleichem in Yiddish, and so on.

Now Golubovsky walks around the city seeing its cobbled streets covered in anti-tank devices, hearing explosions overhead. In his emails, he insists on both the importance of cultural memory and the need for new voices. At his suggestion, I begin a series of interviews with the members of Green Lamp, whose words about the first few weeks of this war you can read below. “My wish for you,” Golubovsky writes, “is to never have the experience of going about your day to the rhythm of constant air-raid sirens. The pain is experienced by the city and by Ukraine as a whole. This pain passes constantly through the writer’s breastbone.”

Elena Andreychykova

“And you?”

Every morning starts with this question. I am asked and I ask. Family asks, friends ask, colleagues, acquaintances: my lines of defense. I still can’t understand how it can be—war in Ukraine? Attacked by Russia? They are bombing our cities? Just days before the war began, I finished my latest novel. The protagonist dreams about war—dreams impacted by stories of her grandmother, who was a prisoner in the Salaspils camp. I haven’t found the strength to reread the novel yet. I still feel disgusted.

One day I will find the courage to rewrite it. I will speak as a witness. To how scary it is when air-raid sirens wail in the early morning on an ordinary Thursday. How I kept smiling while packing frantically, trying to signal to my son that I was not worried. How a warehouse exploded and burned before our eyes, less than two hundred feet away. How we spent a night surrounded by jam jars in a root cellar in Odesa. How my three-year-old nephew, who had just arrived from Kharkiv, stuttered and cried. How unwilling I was to decide whether I should stay with my husband or drive the kids away from all this. How we left Odesa at night: eight cars, women and children, cats and dogs. Some of us were driving for the first time ever. We were stopped at a checkpoint: no cars were allowed to pass through at night. One woman suddenly exclaimed, “I know the password! My husband wrote it down for me before he went to war.”

We fight our own information war. We wake up every morning and hope that it’s all over. That we can live, plan, write novels again. But for now, I just message everyone: “And you? How are you?” Hearing an answer is the only thing that matters.

Vladislava Ilinskaya

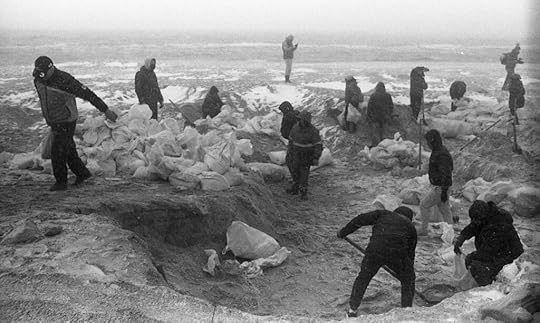

After a week spent in a stupor, I walked out into Odesa’s streets to see anti-tank fortifications, barricades made of sandbags blocking the avenues. Boutiques and restaurants boarded up. People with guns on the streets. I’m writing this in a taxi. We were just stopped at a checkpoint, we were searched. It’s frightening how quickly I’ve gotten used to this life.

The most terrifying thing is the silence, when you know that the whole country is boiling in a bloody broth. Our people are amazing: never before have I seen such solidarity and care among neighbors.

A strange feeling: as if I haven’t lived before this moment. As if some kind of shell has burst, a carapace that prevented me from breathing in deeply. I don’t know what I did before the war. I’ve never been so aware of being needed, of being involved in reality.

People gathering sand into bags for fortifications. Photograph by Anna Golubovsky.

Vitya Brevis

War entered my life in L’viv. I was there on vacation. An urge to go home: I got on a train back. I am still not quite sure why I went toward Odesa when most people were leaving our city for L’viv or to go farther west, abroad, to safety. I struggled to get through the crowd at the station in L’viv. People were waiting for trains to the western border, and the trains were five hours, seven hours late; some folks were sleeping on their suitcases, and kids were crying, just like they do in movies about war.

Today is March 11, the sixteenth day. The war of bullets and bombs has not started full swing in Odesa yet, but you are going to read this later, so you will know more than I do now. I envy you.

In the beginning I taped my windows, crisscross, so that even if something exploded nearby, the blast wave wouldn’t leave my entire apartment covered in shards of glass. I moved a large dresser in front of the window for better protection. As days went by, we got used to being afraid, so I moved the dresser back to the wall, and peeled the tape off.

Other cities get bombed, missiles explode, and Russian soldiers walk down the streets and sometimes shoot the locals for entertainment. Those who are leaving Odesa now see that other side of war: crying children, thirty hours of waiting at the Moldovan border, not knowing where to live, where to shower, or when to return home.

I live on the twenty-first floor. There is no one left around here. Of eight apartments, only one still has inhabitants: my dog, my cat, and me. When I hear the sirens wailing, I walk out on the balcony to see if missiles are coming.

Eugene Demenok

I have been dividing my time between Prague and Odesa for many years, but when this war started, my family was on a trip to New York. For a few days before our flight to Prague we did not venture out of our hotel room other than to attend protests. We spent the entire time scrolling through the news and calling our friends and family.

Back in Prague, we found we could be of more use: the Czech Republic has already received more than two hundred thousand Ukrainian refugees. I spend my days between the refugee integration center, the train station, and a community residence for seventy-two people that my friends are building at their own expense.

I cannot write anything. I don’t have the stamina, desire, or time for it now. For many days, I have been grinding my way through a piece on the correspondence between Henry Miller and David Burliuk. I would love to publish a few letters from Miller in Ukrainian translation for the first time. And yet my mornings start with calls and letters asking for help, my days are spent on volunteer work, and by the time I am free it is already late into the night.

Vladislav Kitik

A seagull, all fluffed up, sits at the edge of the pier, chest against the wind. A sharp explosion over the bay interrupts its contemplation of the gray water, and it spreads its wings.

Seagulls don’t know what war is. But after sixteen days, the gulls have managed to overcome their confusion and learn not to fly too far when the sky shakes with land-mine explosions or cannon fire, not to hide when they hear the howl of sirens.

The seagulls fly over Odesa’s streets, which are usually crowded and noisy. A rare pedestrian leaves footprints on the untouched snow. In silence, the famous Potemkin Stairs climb the slope, buried in bags filled with sand. They hide the monument to the city’s founder—Odesa’s bronze soul—from the malice of artillery. But the seagulls love the sand.

The street bristles with anti-tank devices. Will they be able to protect us against modern missiles? Of course not. But there is something hoodlumish, cocky, in these six-pointed crosses known as hedgehogs. Such hedgehogs stood here in 1941, and now time has jumped off the footboard of the past.

The gull circles over the houses and flies once again to the sea.

Ganna Kostenko

A few days ago, I decided to listen to Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto. I wanted to clutch it in my hands like a branch, so that I wouldn’t slip into the sticky mud of hostility toward everything Russian. Rachmaninoff is innocent—he has nothing to do with Putin’s crimes. Just as Goethe was innocent of Hitler’s madness.

Yesterday, during an air raid, I hid in a bathroom, and I understood with clarity that I don’t want to sink into hate. I have made a choice for myself, and I am trying to stick to it. Hate is the language of my enemies. It is their source of strength. How else to explain the bombardments of kindergartens, maternity wards, hospitals?

I come back to Heine, who said that each new epoch needs a new kind of reader, needs new sets of eyes.

Victoria Koritnyanskaya

What is life in wartime? It is hard for me to choose the right word—I suppose life has narrowed to some very mundane actions: watching the news, buying groceries, cooking simple food, washing the dishes. I try to read books and even to continue writing an article about the artists of Odesa in wartime, but … Here’s a thought: What is it all for, if tomorrow I—and Odesa—may not exist? War steals the pleasure from writing.

War steals many things. Even an ordinary walk by the sea is impossible—the beach on Luzanovka has been mined in anticipation of the Russian landing. Odesa now lives in a constant state of suspense, waiting for the shelling, the air strikes, the chemical attacks. We live inside the waiting hours.

The strangeness is everywhere: barricades made of sandbags and concrete blocks at almost every intersection, volunteers distributing bread and sausages. There is strangeness, too, in the snow that has been falling for three days—frost in Odesa, a vacation town, in March!—and in the courage of my neighbor, an eighty-year-old woman who survived Hitler’s war, who every evening says: “You need to have a good wash and put on new clothes, so that if they bomb you, you will be clean …”

Despite it all, I am convinced: We will get through this. Because white snowdrops and violets are blooming in all the front gardens, because pigeons are cooing on my windowsill, because we are strong.

I am not sure about literature right now, whether anyone needs it … My essays on the Second World War, which I wrote based on interviews with eyewitnesses, are no longer relevant—we have a different war, a different experience. And my other writing—my stories about angels—is too light to be timely now. The Russian language in which I write is no longer trendy. I think sooner or later every writer in Odesa will face the question of whether to write in Russian, only for Odesa, or to write for the whole of Ukraine, in Ukrainian. What choice will I make?

Odesa Opera Theater. Photograph by Anna Golubovsky.

Vadim Landa

My wife and I left Odesa for Poland. A group of friends, nine of us, crowded in a train compartment designed for four people, traveled to L’viv. Then we tried to cross the border by car, but our cars were stopped. We walked on foot for a mile in the snow and stood in an enormous crowd that the border guards called a “line to the checkpoint.” The guards left us and focused their attention on the trucks coming from the other side of the border. From time to time someone in the crowd screamed, “Doctor!” Old women were fainting. Finally, a border guard let us into the building. The crowd flooded the empty hall. We stood there for an hour. Then a guard shouted, “Run into the next hall!” The crowd flooded into the next room, only to find that we were now behind those who had been behind us in the crowd outside. The mothers with young children were hysterical.

An impossible moment: a border guard stamped our passports, and we entered Polish territory. The guard, playing Santa Claus, gave each child a candy. But it took two more hours to pass through the Polish border. Then, a bus to the information center. Another bus to the train station. A second half-sleepless night, sitting on suitcases in the hallway of a crowded, moving train. We tried not to look at ourselves in the mirror.

Finally, in Poland, friends and volunteers try to help us, selflessly. What will the future hold for us? Who today would dare to answer such a question?

As for writing: I am unable to read anything except the news—so don’t ask me about my writing. My attitude toward the Russian language has not changed. No, I don’t speak the language of the occupiers of my country. It is they who stole my language.

Marina Linda

In these two weeks my life has changed entirely: the world I knew has become as fragile as shortbread. But people who might have been weak have become as strong as steel. I myself have felt for many days like a kind of iron frame on which the whole house hangs, on which my frightened children, my cats, and everything I know is hanging right now, including my own clarity of mind.

A strange feeling: everything around me now is what I once used to read about in books on war, thinking how wonderful it was that I lived in a different time. I don’t live in a different time. This movie is now the life of my family, my city. It is a very mediocre movie. I want to turn on the lights in this theater.

Anna Mihalevskaya

The cats are screaming in the night, trying to outscream the air-raid sirens. I find beauty in strange things—graffiti on peeling walls, a street dug up for repairs. I look about greedily. I don’t know if I will ever see this or that street again. I see photos of Kharkiv in ruins, photos of a bombed-out Kyiv. Everything is changing too fast. If you want to do something, you need to do it right now.

Doing something, anything, is medicine at this moment. When I manage to help someone, I can forget about the war. I think many people have discovered this.

Prewar life already seems unreal and faraway. There was so much in it. I didn’t appreciate it: always rushing, searching for new projects. Not enough time for basic talk. Now there is so much talk, but it is tense. Cruelly, this situation brings us back to each other.

Nail Muratov

Has Odesa changed in these first few days of war? Yes. No. There are lines of people at the gas stations so long that they are blocking traffic on the streets, lines in stores of people sweeping everything from the shelves—cereals, sugar, salt, matches—this blizzard of movement pulling the city from its usual calm, this human anthill.

Checkpoints have sprung up, but cars still weave through the streets, fewer now. Passersby go about their business; supermarkets and some small stalls and kiosks are open. On Monday, classes are starting in schools and universities. But no one knows what will happen next.

In times of war, writing goes badly. What can you do? Your mind refuses to make sense of what’s happening.

Some people have left, and those who remain have banded together. My ninety-two-year-old mother returned a couple of days ago from the store, and in her bag were several cans of preserves, given to her by women she didn’t know.

Taya Naidenko

On the first day of the war, people in Kharkiv, in Kyiv, in L’viv—first among them Russian-speaking and bilingual people—started speaking Ukrainian en masse.

Some have already managed to “surrender” and transition back to their customary Russian. At first with a disclaimer—“In order to be understood by all the Russian enemies”—and then silently, without rationalization. When, hurriedly, between air raids, you try to articulate your thoughts and feelings, you involuntarily switch back to the language you’ve been accustomed to thinking in since childhood. Others keep their oath—not one more word in Russian!—and I think they will remain strictly Ukrainian speakers even after the war.

The Russian invasion showed what a source of strife regular words can be. Some fearmongers, including those from other countries, accuse me of naivete: “After the war they could ban speaking Russian in Ukraine!” But I remind them: saying what you think in the Russian language is banned only in Putin’s Russia.

Anna Streminskaya

A city that is preparing its defense does not make the best impression. You can’t simply pass through the streets of the city center: everywhere there are tank traps, sandbags, wire gauze.

Several times a day there are air-raid alarms, and some neighborhoods have no bomb shelters. I bring my eighty-five-year-old mom to the bathroom, the only place in her home where it’s possible to find some kind of shelter.

Through all this, Odesites are not losing their sense of humor. Across the city walls there are giant banners advising Russian soldiers to do as Ukrainians on nearby Snake Island had famously suggested a Russian warship should. In wartime, profanity is forgivable, it relieves stress.

People are volunteering everywhere, assembling sandbags on the seashore. “You’re an Odesite,” the song goes, “and that means that neither grief nor misfortune is scary for you!”

I’ve written several poems about the war. A poet should be a vibrating string that responds to everything happening around us. I am following what my poet friends are writing, and the level of their poetry has risen—the language has become very precise, strong.

There are no words nor justifications for what the Russian Army is doing in Ukraine—in Kharkiv, in Mariupol’, in other cities. Still, the task of poetry is to find words even when there are none.

Translated from the Russian and the Ukrainian by Ilya Kaminsky, Katie Farris, Natalia Baryshnikova, Louis Train, Anastasia Diatlova, NK, and Yohanca Delgado.

March 23, 2022

Remembrance Day

Illustration by Alex Merto.

Spencer Matheson is a novelist and poet. His fiction has appeared in Conjunctions. He lives in Paris, and teaches at the École normale supérieure.

How to Choose Your Perfume: A Conversation with Sianne Ngai and Anna Kornbluh

Sianne Ngai, Anna Kornbluh, and Jude Stewart try perfumes. Photograph by Seth Brodsky.

Even after writing a whole book about smell , I still resisted finding “my” perfume. Perfume has always seemed gimmicky, too expensive, anti-feminist. But researching my book got me rethinking these objections. I wanted to get to yes with perfume but do so honestly.

I mentioned this to my friends Sianne Ngai and Anna Kornbluh , who both really like perfumes. Sianne is a professor of English at the University of Chicago and specializes in aesthetics and affect theory in a Marxist context. She has written books about the “ugly feelings” of envy and irritation; contemporary aesthetic categories like “cute,” “zany,” and “interesting”; and, most recently, a theory of the gimmick. Anna is a professor of English at the University of Illinois Chicago and specializes in formalism, Marxism, aesthetics, and psychoanalysis.

Sianne, Anna, and I are middle-aged women who admire each other, loudly and often. Our sensibilities overlap but also diverge in intriguing ways. We met for this conversation in September at Sianne’s high-rise apartment in Chicago’s South Loop. It’s an airy, glassed-in space with views of Lake Michigan and the South Side in many directions. The day was unseasonably warm, so we’d brought our bathing suits to swim in her building’s rooftop pool. But first we spread out tiny bottles of perfume on her kitchen table, and sprayed and sniffed for a good long while.

NGAI

Let me start by asking, Why a perfume? Why not several? A lot of people have perfume wardrobes. You can have a depersonalized relationship to perfume and just ask, How do I want to smell, in a performative way?

I like perfume. I got really sucked into it and then I had to pull away because I had a dog whose nose was very sensitive. The irony is I ended up with a boyfriend who’s so romantic that he gets upset when I wear anything other than the scent I wore when we met.

When I first got into perfumes I thought about it all wrong. It was very conceptual, like, I bet I’ll be someone who likes citrus. I was reifying my identity, thinking of myself as a certain kind of person. It turns out I don’t like citrus at all in perfume. I don’t like florals either, especially jasmine or rose. I do like earthy, woody smells. When I leaned into what felt good at the level of sense, it became easier.

KORNBLUH

Smell really vexes the problem of aesthetics because it’s always a judgment. I smell something, I identify it, and it smells good or it’s not good. But what authenticates the judgment?

NGAI

What is interesting is that middle ground where you’re finding concepts for an experience that’s profoundly immediate and spontaneous. You remove the layer of, Do I like it or not? It becomes more about, How will I use language? What’s amazing is that the vocabulary works.

In your book, Jude, you asked, How could I become a better smeller? I like how you shifted away from questions of connoisseurship. You didn’t want to cultivate better aesthetic taste than other people. You just wanted to take in more of the world. Fredric Jameson once said, paraphrasing Adorno, that when you’re doing aesthetics as a Marxist, you can’t get away from the fact that art is a luxury item. It shouldn’t be, but that’s the guilt of the art object for certain critics. There’s an anecdote I’ve heard about Herbert Marcuse being interviewed at his home in La Jolla, California. The interviewer says something challenging, like, “Herbert Marcuse, you’re a Marxist thinker, but I’m looking at all this luxury. We’re lounging around your swimming pool. What do you say to that?” And Marcuse supposedly replies, “Nothing is too good for the people.” That’s a great response to the guilt thing.

STEWART

Yeah. I wanted to inhabit my body more and stop doing this head-in-a-jar screen thing. It’s funny, when you write about the smell of freshly sharpened pencils, you can’t just go to Wikipedia and start your research there. You have to get actual pencils—a lot of them, it turns out—and sharpen them first. With smell, you bump into thingliness at every turn.

KORNBLUH

You were trying to have a sensuous basis for ideas you’d generate and translate them back into prose. That’s a conundrum because you’re having this deeply embodied experience. We know that the perfume will smell differently on you than it does on Sianne.

NGAI

And we’re spontaneously going to like or dislike it.

KORNBLUH

Right. Even though smell is our most sensitive sense, it’s the one around which we have the least cultural apparatus. You can’t traffic in smell the way we traffic in images or sounds.

NGAI

There’s a school of thought that says concepts kill beauty. Knowing history won’t help you find the stone more stony. But that’s where that philosophy was completely wrong. Jasmine has a history and a set of values associated with that history, and the more you know about something, the more you can perceive in it. So your perception is expanded by the conceptual and not broken by it.

Back to embodiment. We’re never just smelling the thing, like freshly sharpened pencils. The pencil is also a tool, with a certain production in the world. Your book suggests it’s wrong to say that those things aren’t also being smelled in pencils. As you write in your jasmine chapter, when we smell jasmine, we also smell civilization, well-ordered beauty, luxury. I have to say, when I smell jasmine, I smell gender.

KORNBLUH

Let’s spool this out a bit. I think the whole denigration of luxury is entailed in the denigration of women, for many reasons. Smell is a determinant of atmosphere. It can accord sensation to people. It prompts and triggers many things. And who’s in charge of atmosphere?

STEWART

Not women, usually.

KORNBLUH

Some of smell’s power might be associated with masculinity in the sense of controlling the environment.

Thinking about Marcuse’s remark on luxury, some of the more contentious arguments in Marxist theory circle around whether we can have luxury or not. Some Marxists think there shouldn’t be a scarcity of pleasure, that beauty and sensuousness can arise inside a different mode of production. Others think it’s a fantasy of hyperconsumption and we need degrowth. And those positions present themselves more and more in our time of ecocide as the environmentally realist position. But they are deeply misogynistically motivated, because of this long historical, artistic, and rhetorical association of women with too much consumption, with uselessness and ornament.

NGAI

Which is racialized, too.

STEWART

This idea that smells control environments is true in a different way. Only twenty percent of fragrances are luxury perfumes, the ones we’re talking about. The other eighty percent are so-called functional perfumes in laundry detergents and personal products. We live in a smell reality that’s much more edited than we realize. It’s mind-bending. But we were talking about gender and who controls environments.

NGAI

A friend once told this story about another friend who’d wear a strong perfume and then try on clothes in stores. She liked leaving her trace on all the clothes. My friend found this appalling.

STEWART

Well, it is. It’s a power move marking her territory.

KORNBLUH

That also speaks to the situation dependence of smells. If you’re flying on an airplane or going clothes shopping, should you spray your perfume?

STEWART

How much scent is too much is both personally and culturally dependent. Take oud, a super expensive incense that Middle Eastern people scent their clothes with. If you’ve ever strolled through an international airport, you know the scent bower can be large. Part of what one is choosing with perfume is to create a nimbus. The question is, how social or private should that nimbus be?

NGAI

How I approached perfumes is that they were for me. When I’d perform in public I’d wear something for me to smell, like a halo of protection.

STEWART

Who said that fashion was armor? Perfume can be a kind of invisible armor, too.

KORNBLUH

Another thought about perfume and gimmick is that perfume is a shortcut to charisma. It’s a way of projecting a nimbus of self into the world that other people can respond to without words. Does that imply perfume is more for single people?

NGAI

Some perfumes are complicated and aren’t a good shortcut to anything precisely for that reason. I’m upset because there’s a perfume that exemplifies this that I’ve been searching for and can’t find. It’s called Dzing! by Olivia Giacobetti, for L’Artisan Parfumeur. Dzing! is discontinued. It smelled like a mixture of horse, leather, sawdust, cotton candy, popcorn, and poop. I loved Dzing! so much, but it’s not a good shortcut.

STEWART

Speaking of horses, have you seen the Adam Driver Burberry Hero perfume commercial? It’s incredibly weird. Perfume ads almost justify my complaint about perfume as gimmick. They’re so awful.

KORNBLUH

They’re not as stylized as fashion photographs and don’t have a clear point of view. They’re just trying to convey evanescence and mystique and whatever.

NGAI

They always tell a flattened story. And they’re also very white.

STEWART

Yeah. What they’re trying to convey more than anything is white subjectivity. But I do want to figure perfume ads out. So much gets crammed into them that almost nothing gets communicated about what the perfume smells like.

NGAI

I actually think perfume ads are quite accurate in their semiotics. For example, the Clinique Happy ad with the puppy. You can tell this is a sporty, citrusy, feminine scent and not something with oud in it.

STEWART

In your latest book, Sianne, you say a gimmick is something that’s somehow working too hard and not hard enough. After writing my book about smell, I can’t say that perfume is not working hard enough. It’s insane how much effort goes into developing perfumes—and how much money they make. Possibly perfume is working too hard. For you, why is perfume not dismissible as a gimmick?

NGAI

Oh, I don’t know. Perfumes can contain gimmicks, sure. Do you know the novel Clear by Nicola Barker? It consists primarily of people discussing and justifying their aesthetic tastes to one another. All these conversations are catalyzed by the dangling of an enormous gimmick over a public space in London—the illusionist David Blaine starving himself in public in a glass box in 2003. This piece inspired such strong feelings from the British public that it made them newly aware of themselves as a public.

There’s a conversation about perfume in Clear in which one character sniffs another and says something along of the lines of, Oh, you’re wearing Comme des Garçons Odeur 53. That’s a perfume designed to have a space in the middle of it, meaning the middle or heart note is intentionally empty. And then she disparagingly says something like, Of course you bought that. Implying he fell for a cheap Conceptual art move. So, yes, there are definitely gimmicks in perfume.

That makes me think of another book, Teresa Brennan’s The Transmission of Affect, where she makes an analogy between affects, feelings, and smells. She’s interested in the idea that we can feel other people’s feelings before they’re conceptualized or named. Feeling tension in a room is similar to smelling it.

STEWART

There are emotions we can smell from each other’s bodies: fear, joy, and disgust. And smell also has metaphorical associations with wit. We’ll say, Does it pass the smell test? Or, Did you it sniff out? Intelligence is implied in smell.

NGAI

Probably because smell moves across borders. That’s why affect theorists like it. It’s relational and causes boundary confusions. Is it out there or is it in me? Well, if you’re smelling it, it’s both.

STEWART

In preparation for today, I wore different perfumes and reflected on them. My questions were different in practice than in theory. I wondered, What am I asking from a perfume as an aesthetic experience? I also considered logistics, like, Am I choosing the right pulse points? Am I putting perfume on at the right time of day? In short, I tried to create aesthetic encounters around perfume with myself, over time.

NGAI

I love that. What’s cool about perfumes is that they’re narrative, they change over time. My friend Tina Post uses this metaphor of filters, like on Instagram, to think about aesthetic experiences. A filter can describe how the same perfume smells subtly different on different people. You observe different patterns of decay of one note and the emergence of another.

KORNBLUH

This brings us back to the problem of describing smells. There’s the narrative lapse of how they change over time. There’s a situatedness of how they wear on different people. And there’s the problem of aesthetic vocabulary. If I tell you I’m buying a lipstick-red couch, you probably know what I mean, but we don’t have a well-honed cultural sense of describing smells. You’re always using other smell words, with narrative, subjective, and even biochemical complications. I don’t like jasmine, but you have no fucking idea what I mean when I say that. Do I dislike the top note of jasmine? Do I mean jasmine on my body? Jasmine on your body?

STEWART

Jasmine has many, many notes but they’re unusually well-balanced, as if a perfumer created them. And jasmine does have a fecal decay note. That might be the note you object to, Anna—but it’s also the note someone else loves. All the perfumes I didn’t like after wearing them seemed too one-note, they didn’t make me want to figure them out. For example, this one isn’t my favorite but it is fucking weird in a good way. It’s CB Beast by I Hate Perfume’s Christopher Brosius. It has opening notes of roast beef and parsley, and then it mellows out into an interesting smokiness. [We apply CB Beast and sniff.]

I‘m getting a hot-stone thing.

KORNBLUH

The pine is very strong.

NGAI

Yes, it’s a medicinal smell. It’s menthol and eucalyptus and dried black things, a little scary. Like my grandma’s Chinese medicine cabinet.

KORNBLUH

Here’s the problem, though. I’m sniffing this and don’t dislike it. A beef perfume concept was disgusting to me before I tried it on. But if I had purchased it for that beefy note and then didn’t think it smelled like beef, is the defect in me or is it in the commodity? You know, Where’s the beef?!

STEWART

That gets back to the question of what you want perfume to do for you.

NGAI

I want to be bold enough to wear a perfume like CB Beast. Not to please to other people, but to smell like, Fuck you.

STEWART

Yeah. I’m intrigued by fuck-you perfumes. At the other extreme, I liked these subtle perfumes that invite someone to come closer. Here are two—Cyan Nori and Green Cedar, both by Abel Odor.

Green Cedar is resinous. It’s very secretive and contained. Nori Cyan smells like the sea—but not in a Jean Naté, fresh, clean, overly simplistic way. It’s more like the actual sea, with a little rot and that live, hunger-making quality of ocean air. These scents were like cool techno music, where the music is so spare it doesn’t feel complete. They’re roomy. You complete the music, or the fragrance, by moving your body around.

NGAI

I like how wearing perfume extends your personal space. When you encounter dangerous animals in nature, you’re often supposed to make yourself bigger. And perfume lets you spread out and become bigger.

STEWART

I like the idea of smelling something to snap yourself into a mood, too. For instance, actors keep smells on hand if they need to cry for a scene.

KORNBLUH

It’s a short circuit to intensity again, because the smell process is much faster than the other senses. Smell’s rapidity may give us the illusion of power as disguise. But you know, nobody can ever see women. Right? The lady camouflage.

STEWART

Two things fascinated me when thinking about smell beyond perfume. One is how smell makes you aware of air. We’re not sitting in a void, we’re in a room filled with gasses. Air’s existence, its movement, becomes palpable because smells ride on air.

The other thing was how perfume interacts with time. Perfumes unfold over time, but also smell collapses memory. We can visit a historical landscape or even an imagined landscape via smell. You can smell Napoleon’s perfume and even buy it. Green Cedar reminded me of a small cedar-lined closet we had in my childhood house. It was full of tennis balls and sweaters. That scent has a physicality that’s very close.

NGAI

You’re suggesting that perfumes also have scale.

STEWART

Air has more dimensionality than we credit to it, and time and space are forms of dimension that are part of smell and perfume. While I’ve been trying with perfume to articulate an aesthetic experience, just sitting with a sensory experience you can’t explain is also a defensible pleasure. We’ve established that it doesn’t matter what those aesthetic preferences are. The pleasure comes in finding that friction.

Jude Stewart is the author of three books, most recently Revelations in Air: A Guidebook to Smell. She has written about design, science, and culture for The Atlantic, the Wall Street Journal, Quartz, The Believer, Fast Company, and many other publications.

March 22, 2022

Objective Correlatives

In compiling the following list of influences and inspirations for my memoir, Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography, I had a certain, specific range of aesthetic experiences in mind. What I was looking for in this list were particular individuals, works, or bodies of work that engendered in me a deep aesthetic experience that expanded and altered my understanding of art, of myself, and of the world. In some cases these were specific experiences that have stayed with me for decades.

CIDOC

In 1971, I attended a month of seminars, talks, and workshops at CIDOC (Centro Intercultural de Documentación) in Cuernavaca, Mexico. CIDOC was an institute founded by the radical educator Ivan Illich, whose book Deschooling Society was published that same year. Most of the major progressive educational theorists in North America were present that month. Particularly memorable was a one-week workshop I attended that was conducted by George Dennison: “Organic versus Arbitrary Order.”

James R. Roberts, Ivan Illich leading seminar at the Centro Intercultural de Documentación, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1971. Courtesy of the Northwestern University Archives.

The workshop met for a few hours each day, for five days. We sat spread out on a lawn at CIDOC. Instead of being a theoretical discussion of organic versus arbitrary order, the workshop was, itself, a demonstration of organic order—the order that grows outward from the relationship of the essential elements of a situation. Dennison let the discussion go wherever it seemed to flow. He was a person of wide-ranging interests and experience. There were several participants who became frustrated with the free-form nature of the workshop. The “arbitrary order”—the order imposed onto a situation—is what they brought to it. Dennison’s workshop sensitized me to the structural issues at the heart of how a photographer translates the world into a photograph.

Several years later I ran into Dennison at an exhibition of Cézanne’s watercolors at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I remember him commenting that the watercolors reminded him of late Beethoven quartets.

Paul Cézanne, Forest Path, 1904–1906.

Walker Evans

In the 1964 edition of Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography, he included a final chapter titled “Recent Trends.” He described four trends: the document, a photograph that points to something out in the world and asks us to pay attention to it; the straight photograph, a self-conscious work of art that asks us to pay attention to the picture itself; the formalist photograph, a picture that explores the structural qualities of an image or the formal nature of the medium; and the equivalent, a photograph that embodies or engenders a state of mind or an emotional state (what T. S. Eliot might have called a picture that functions as an “objective correlative”). These aren’t necessarily separate aesthetic directions. A photograph can be a self-conscious work of art that springs from a perception of the world, that is clarified by formal understanding, and that is sensitive to the psychological and poetic resonances of the image. A photograph can address all four at the same time, and the best of Walker Evans’s images do.

To this Evans added an awareness of the cultural implications of a visual style, as when he spoke of photographing “documentary-style.”

Walker Evans, Breakfast Room, Belle Grove Plantation, White Chapel, Louisiana, 1935. Courtesy of the Walker Evans Archive.

The Gubbio Studiolo, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The studiolo is a small room with a door and a window. The walls are a trompe l’oeil representation of a study, with books and musical instruments on shelves and benches against the wall. Light from the single window appears to filter in and cast shadows on the bookshelves, whose latticework doors are sometimes slightly ajar. This illusion is created entirely of wood veneer. Most of the photographers I know who are familiar with the studiolo love it—I assume because we, too, deal in illusion and representation.

Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, designed by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, ca. 1478–82.

Giulio Romano’s Sala dei Giganti, Palazzo del Tè, Mantua

In the 1568 edition of The Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari wrote of the Sala die Giganti:

Let no one think ever to see any work of the brush more frightening, or more realistic, than this; and whoever enters that room and sees the windows, doors and so forth all distorted and apparently hurtling down, and the mountains and buildings falling, cannot but fear that everything will crash down upon him, especially when he sees in that Heaven all the Gods rushing here and there in fright. And what is most marvelous to see in this work is that the whole painting has neither beginning or end, but is all interconnected and smoothly continuous, with no ornamental partitions or boundaries, so that objects which are in the distance, where the landscapes are painted, gradually recede into infinity. Hence that room, which is no more than thirty feet long, seems like open country.

And the acoustics of the room make the air seem to crackle.

Giulio Romano, Sala dei Giganti, Palazzo del Tè, Mantua, 1532–34.

Ibn Tulun Mosque, Cairo

I’ve been in two buildings that I would call examples of “objective architecture”: Ibn Tulun and the Pantheon. By “objective architecture,” I mean a building that by design, by material and volume and light and detail, produces a specific, intended state of being in receptive visitors. Ibn Tulun opens the heart.

Berthold Werner, Mosque of Ibn Tulun at Cairo, licensed under CC by 3.0.

Equivalents

I am struck by how, in Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, the structure of the plot, of the photography, of the editing, of the pacing of the dialogue, and, importantly, of the interior of the Amberson Mansion are all of a piece. There is a unity connecting these various aspects—a unity of mise-en-scène. The experience of watching the film was an early building block in my understanding of structure and meaning in art.

Still from The Magnificent Ambersons, directed by Orson Welles, 1942. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

The Amberson mansion’s Victorian interior—its ornateness, its darkness, its heaviness, its complexity—seems a physical reflection of the characters’ Victorian repression and of their interactions: George Minafer’s weak manipulations, Aunt Fanny’s shrill manipulations, George and Lucy’s Oedipal undercurrents. The mansion is an objective correlative, but it’s not simply the interior. The film’s core is carried through in the acting, in the structure of each image, and in the camera movement. A unity of means.

The term objective correlative was used by T. S. Eliot in his essay on Hamlet. Eliot wrote:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an “objective correlative”; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.

In photography, this relates to what Alfred Stieglitz called equivalents. This is what he titled a series of pictures he made of clouds. He saw the images as being equivalents of psychological or emotional states.

Alfred Stieglitz, Equivalent, 1929. Courtesy of the Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

He photographed clouds because he wanted to rid the experience of the image of the associative meanings of content. He wanted the pictures to be abstract. But photography is relentlessly specific. A straight, unmanipulated photograph is a representation of the world seen at a particular moment, from a particular vantage point, within a defined frame. Within these parameters, it seems literal. So, these pictures of Stieglitz’s do have recognizable content—clouds. They are not abstract the way, say, Lotte Jacobi’s work is.

Stieglitz wanted these images to be like music. Where music is sound and structure, photographs are tone and structure. But some music also has lyrics, and a photograph can have recognizable content, with all its resonance and cultural meaning, and still stand for or, perhaps, evoke a state of mind. This is what Walker Evans meant when he referred to “transcendent documents.” Photographers sometimes find themselves attracted to certain content, not for its political or sociological meaning, but because it, for some reason, touches them—stirs something in them. This content, in this light, means something.

Stephen Shore, from Transparencies, Small Camera Works 1971-1979.

One of the threads running through the history of the medium is the redefinition of meaningful content. Photographers find meaning in something where it hadn’t been recognized before, and then, over time, that content itself becomes a convention. And when it becomes a convention, it lacks the immediacy of the original picture. “Immediacy” means without mediation. Without the mediation of visual conventions. In time the original content becomes a cliché. And the cutting edge of immediacy finds new territory to function as an objective correlative. Not new for the sake of newness, but because an artist, working within the center of the present, experiences with spontaneity.

George Eliot

Reading Eliot, I see a world where real compassion and sense of humanity are amplified by clarity of thought, unclouded by sentimentality. It is dense in subtext and in wisdom. And her English is simply a delight to read, as in Daniel Deronda:

The Meyricks had their little oddities, streaks of eccentricity from the mother’s blood as well as the father’s, their minds being like mediaeval houses with unexpected recesses and openings from this into that, flights of steps and sudden outlooks.

When I first read this sentence, Ginger and I were living in an eighteenth-century house in the Hudson Valley. Our house was sandwiched between a hill, a large rock outcropping, and a stream. Over the years it had been expanded in a way that organically accommodated its difficult site. It literally had unexpected recesses, flights of steps, and sudden outlooks.

Stephen Shore, Rye, United Kingdom, June 24, 2016.

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick

I remember the days, almost fifty years ago, when I was immersed in this book. Melville’s thoughts formed a backdrop to my daily experience. They sometimes still do. “Do thou, too, live in this world without being of it.” The book is like an eight-hundred-page poem.

It does seem to me, that herein we see the rare virtue of a strong individual vitality, and the rare virtue of thick walls, and the rare virtue of interior spaciousness. Oh, man! admire and model thyself after the whale! Do thou, too, remain warm among ice. Do thou, too, live in this world without being of it. Be cool at the equator; keep thy blood fluid at the Pole. Like the great dome of St. Peter’s, and like the great whale, retain, O man! in all seasons a temperature of thine own.

…

There is a wisdom that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness. And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.

The Catskill Eagle paragraph seems like an elaboration of and response to Ecclesiastes (1:17–18), here in the King James Version, with which Melville would have been familiar:

And I gave my heart to know wisdom, and to know madness and folly: I perceived that this also is a vexation of spirit.

For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.

I must admit to a fondness for beautifully constructed sentences, with cascading dependent clauses. I think I take a certain kind of almost physical pleasure in holding the clauses and their referents in mind. For no other reason in particular, these sentences from chapter two sometimes come to mind:

As most young candidates for the pains and penalties of whaling stop at this same New Bedford, thence to embark on their voyage, it may as well be related that I, for one, had no idea of so doing. For my mind was made up to sail in no other than a Nantucket craft, because there was a fine, boisterous something about everything connected with that famous old island, which amazingly pleased me.

J. M. W. Turner

From Turner I learned about the balance of dynamic forces in a work of art—finding the center of the work.

J. M. W. Turner, Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, ca. 1842.

Fra Angelico

Standing in front of his frescos in the Convent of San Marco brought me to tears. He speaks directly to the higher emotional center.

With such concentrated truth that his colours here seem dissolved in tears that drop and drop, however softly, through all time.

—Henry James, Italian Hours, 1909

Fra Angelico, The Taunting of Christ, 1441.

Stephen Shore’s work has been widely published and exhibited for the past forty-five years. At age twenty-three, he was the first living photographer to have a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York since Alfred Stieglitz, forty years earlier. More than twenty-five books have been published of Shore’s photographs including Uncommon Places: The Complete Works and American Surfaces, works which are now considered important milestones in photographic history. Shore is represented by 303 Gallery (New York) and Sprüth Magers (London and Berlin). His new hybrid-genre memoir, Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography, of which this is an extract, will be published by MACK Books this March.

Redux: Which Voice Is Mine

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NANCY CRAMPTON.

“Among the greatest pleasures of the Review’s Writers at Work series,” as our editor, Emily Stokes, wrote this week in a note introducing the Spring issue, “is the opportunity to eavesdrop on a revered author speaking intimately.” That sense that you’re eavesdropping is likewise often crucial to literature’s appeal. This week, we slip back into the archives to listen in on John Cheever’s 1976 Art of Fiction interview, in which he describes reading certain books as “finding myself at the receiving end of our most intimate and acute means of communication”; reencounter the young amateur spies of Joy Williams’s “A Story About Friends”; tune in to Laurance Wieder’s poem “The Seismographic Ear”; and rifle through Kathy Acker’s papers.

If you enjoyed these free interviews, stories, poems, and art portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

INTERVIEW

The Art of Fiction No. 62

John Cheever

INTERVIEWER

One almost has a feeling of eavesdropping on your family in that book.

CHEEVER

The Chronicle was not published (and this was a consideration) until after my mother’s death. An aunt (who does not appear in the book) said, “I would never speak to him again if I didn’t know him to be a split personality.”

From issue no. 67 (Fall 1976)

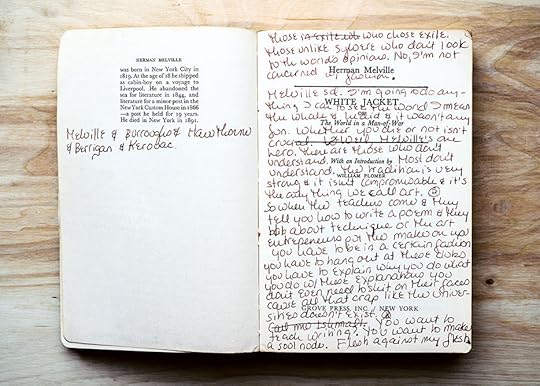

NOTES FOUND IN HERMAN MELVILLE’S WHITE JACKET; OR, THE WORLD IN A MAN-OF-WAR (1956).

PROSE

A Story About Friends

Joy Williams

Their schoolbooks lay open and unread, littered with particles of bread and nail trimmings. Every night that didn’t bring a blizzard, they would spy on the chemistry teacher, for they were fourteen and could only infrequently distinguish what they did from what they merely dreamt about.

From issue no. 57 (Spring 1974)

NOTES FOUND IN HERMAN MELVILLE’S WHITE JACKET; OR, THE WORLD IN A MAN-OF-WAR (1956).

POETRY

The Seismographic Ear

Laurance Wieder

Sometimes I wonder which voice is mine, I hear

The dust accumulating everywhere like dead snow

On bleak eaves, fields, aluminum storm windows

Is also connotative, suggests words which float

From transmitter to receiver, from dusk to dark.

From issue no. 44 (Fall 1968)

NOTES WRITTEN IN JEAN GENET IN TANGIER BY MOHAMED CHOUKRI (1975).

ART

Kathy Acker’s Library

Julian Brimmers

A significant element of Acker’s creative process was her personal library. She was an avid and active reader. She frequently marked passages that she later pirated for her own novels and traced illustrations that would appear in her works whenever writing alone was insufficient. Most important, she used margins, blank pages, and the empty spaces in front matter to formulate spontaneous ideas about her own art and (love) life—a glimpse into the writer’s mind at its most unfiltered.

From issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-nine years’ worth of archives.

March 21, 2022

Painting Backward: A Conversation with Andrew Cranston

Andrew Cranston’s studio. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Andrew Cranston, whose painting A Room That Echoes appears on the cover of the Review’s new Spring issue, did not intend to become a painter. He grew up in Hawick, a small industrial town in Scotland, and planned to become a joiner. For a time he was in a band, and he eventually started sketching. In 1996, he completed his M.A. in painting at the Royal College of Art in London. He now lives in Glasgow with his partner, Lorna Robertson, who is also an artist and works in the studio next to his. When I first saw Cranston’s show “Waiting for the Bell” at Karma Gallery last summer, I was delighted. His paintings, tinged with humor and a sense of longing, invite the viewer into what feels like another person’s dream. I called Cranston from New York while he was in Scotland, preparing for his next show in London. We planned to briefly discuss his work, but ended up speaking for two hours about books, golf, and monkeys.

INTERVIEWER

How did you start to paint on book surfaces?

CRANSTON

I ran out of things to paint on, and I found some books in the studio, so I started working on them. They instantly seemed full of potential—they linked the work to a kind of narrative storytelling and literary interest quite explicitly. And a book, as opposed to a blank canvas or piece of paper, has a particular color and shape, a particular size. You’re destroying the book in some way but making something else with it.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a fictional or poetic quality to your paintings. Do you reference real-life subjects, or are they imaginary?

CRANSTON

A lot of it is rooted in experience. One of the paintings in the show depicts a kind of wall by a beach. That came out of looking at this one tiny corner of a Christopher Wood painting, particularly a wall in the painting. It triggered a memory of being on holiday in Cornwall, which was where Wood lived, and that opened up into trying to remember that holiday, and even trying to remember photographs of that holiday, which I hadn’t seen for a long, long time. So, the art is based on experience, but so many other things get woven in—other paintings, scenes from films, and real places that are there in front of you, but also places remembered.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve seen dogs, monkeys, turtles in your paintings. Do you have any pets?

CRANSTON

Not at all. My dad had, in his childhood, lots of pets, including dogs and cats and birds—and a monkey his granddad ended up with. This was in the twenties or thirties in Scotland. We used to get told about this monkey quite a lot. A funny thing happened when my dad was quite old and quite close to death in a nursing home, and a woman who must have been in her nineties was brought in to see him. She suddenly sparked alive and said, “I remember you. I remember your monkey.” My brother told me it was a hair-standing-on-end moment, because we’d heard about this monkey but never seen any photographs or anything of it. Was it really real, this monkey? And suddenly this person remembered it.

There’s something just strange about animal presences, I think, around you. I don’t have any pets. A way for me to have pets is to put them in paintings.

INTERVIEWER

Do you work on multiple paintings at once?

Winter Vegetables (To Robert Bell Cranston). Courtesy of the artist and the Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh.

CRANSTON

Yes. I will have literally fifty, at least, small paintings in progress at one time. I can’t ever really decide how to finish paintings, so I’ve got the same disease as Cézanne. The only way I can kind of make it work is if I just start another.

INTERVIEWER

How do you know when a painting is done?

CRANSTON

I think it’s quite like bomb-disposal work, finishing a painting. You can do too much and spell things out too much. I don’t really like when every t is crossed and every i is dotted. I want something that’s still open-ended. Sometimes you have to paint backward, when you go past the point at which you had something that was quite mysterious and slightly ambiguous—you realize you’ve made it too clear and too obvious, and then there’s some undoing of that.

A few years ago, I did a painting that was explicitly about writing—it was a bit like the work I did for the Paris Review cover. I write as well, and I was interested in the aspect of writing that is very interior. Most writers do write in rooms—I know that Hemingway wrote in cafes, but probably most do shut themselves away—so, I was working with that idea. That painting sat for a year. I was really looking to do something else to it, and then I realized it was finished. There was nothing else to do.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about the goldfish in A Room That Echoes.

CRANSTON

You can’t really paint goldfish without bringing up Matisse. Matisse owns goldfish, really. He kind of owns red, as well. It’s very hard to think of red paintings without Matisse.

INTERVIEWER

He owns the color red and goldfish.

CRANSTON

You know, Van Gogh has yellow. Matisse has red. Picasso has blue. But the goldfish, I think, poses an interesting problem for a painter—how to represent things like water and glass. The fish was the ping of color that I felt the painting needed. In an abstract sense, I needed something to puncture that kind of atmosphere, the whole fog of the green. That thing became the goldfish.

INTERVIEWER

Do you paint every day?

CRANSTON

Most days. When the pandemic first was unfolding, we were very much in our routine of doing some homeschooling with Joseph, who’s now thirteen, until maybe two o’clock. Then we’d both walk to the studio. We would get to the studio at two thirty, and then we’d work until eleven, then eat, and then do the same thing all over again. That was a very interesting time, in a way, because of the space we went into in each day. I remember reading As I Lay Dying and being especially struck by the fact that—maybe this was in the introduction—Faulkner wrote that book in a six-week period when he was working a job, and the job was a night shift. He would finish at a certain point, midnight or something, and then go home and write from midnight till four or five in the morning, and then get up the next day. The book came out of that process and that space that you can find in a day.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re doing other things, are you still thinking about painting?

CRANSTON

Yes. It’s a total curse. I had a tutor who used to say, in a mantra-like way, “Whatever situation you’re in, ask yourself, ‘Is there a painting in this?’” I’ve really digested that advice. I’ll be in a nightclub and still be thinking, Should I make this nightclub scene into a painting? People sometimes fetishize ideas, but often an idea comes out of just paying attention to a situation. Some part of me is always on the lookout for material I could use. One of the great subjects in painting is people sitting around—bathers, or just people sitting on the grass.

INTERVIEWER

Are there specific authors or works you revisit? Does your reading ever influence your work?

CRANSTON

Books are a huge influence. I’m more a reader of poetry and of short stories than of novels. Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson, James Joyce’s Dubliners, things like that—little glimpses into things. I get a lot from the poet W. S. Graham, who was a Scottish poet based in Cornwall for most of his life. He wrote quite a few poems about painting, and he had a real interest in vision. I like D. H. Lawrence’s poems as well, and Seamus Heaney’s. I like how you can read a poem or a short story quite quickly, but digest it very slowly so that the aftereffects are lasting.

The Hue of an Orange, oil and varnish on hardback book cover, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a particular color that you end up using more than others? Do you have a favorite color that you find yourself sneaking into paintings?

CRANSTON

Yellow. A lot of the paintings start yellow. When I was growing up, a friend of my dad’s from Manchester used to come and visit us. One time he brought us packs of paper he said had fallen off the back of a lorry. There was so much of this paper that we never needed any more paper for the whole rest of our childhood—there was always paper to draw on and make comics. Most of it was yellow, a very pale, quite cold yellow, and most of the drawings I made when I was young were on this yellow paper. Whether that’s the reason, I don’t know. Yellow’s an interesting color psychologically as well. It can feel a bit sick and a bit ill sometimes, jaundiced or something. It’s the color that is the most mysterious to me.

INTERVIEWER

How many brushes do you have?

CRANSTON

A lot, but quite often I’ll make a painting with just one brush. The painter Steven Campbell once gave me the critique, “You’ve only got one brush.” But I find if you use one brush, you are, in effect, putting some of the color all over the painting. It’s a way of connecting bits of the painting. And using a terrible brush can force you to work in ways that make a more interesting painting. I sometimes look at a Rembrandt and see how he’s done the hair, and it looks like he’s used the scruffiest old hardened brush, not his best brush. So I’ve got certain brushes that I use all the time, but they’re not good brushes. You have to invent and to adjust to the tool, and it gives you something quite unexpected.

Andrew Cranston’s studio. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

INTERVIEWER

What do you do for fun besides painting?

CRANSTON

I play a bit of golf. I think golf’s quite different in other countries, but it’s still quite a working-class sport in Scotland and cuts across a lot of class structures. It’s quite cheap, and it’s very easy to get clubs at secondhand shops and thrift shops. I know Mark Twain said golf was a walk spoiled, but you are dealing with some construct of nature when you golf. Some of the Scottish courses are very wild. They’ve not really been tamed or cultivated in the way that other courses in America have been. They tend to use the natural aspects of whatever the landscape’s got: dunes along the coast or the woods. It’s kind of like land art. Golf is land art on a large scale.

INTERVIEWER

Can we expect some golfing to show up in your future paintings?

CRANSTON

Well, it’s so uncool, golf. It does appeal to me in that sense. It’s almost a taboo subject because it’s so uncool. I’ve read that Samuel Beckett was a really big golfer, and I can see that there are slightly surreal qualities about golf. You’re trying to get this ball in a tiny hole, and it’s quite frustrating. There’s something cartoon-like about it. I did do some golf paintings when I was younger. I might do it. I might make another golf painting.

INTERVIEWER

How do you come up with the titles for your paintings? There’s one that I love, and I love the painting: It Was Your Birthday (And a Seagull Shat on Your Head).

CRANSTON

That happened to my partner, Lorna, on her birthday, so that is based on a real experience. I store up the titles. I have them all written down, and sometimes they happily match an idea or match an image. I write on the work as well. I write notes on the paintings, just loose notes about how the painting could go or what it could be about or things it reminds me of. They’re like little index cards or reminders to myself. It’s so fleeting, sometimes, a painting. You forget what you’re meant to be doing. The painting seems to vanish before your eyes. It’s like Orpheus—when he looks for his lover, she disappears.

INTERVIEWER

When Orpheus turns around.

CRANSTON

Yeah. It’s a bit like that.

INTERVIEWER

That’s a great metaphor for painting.

CRANSTON

It’s always slightly out of reach.

Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Na Kim is the art director of The Paris Review.

March 18, 2022

Walk Worthy

In Eloghosa Osunde’s column Melting Clocks, she takes apart the surreality of time and the senses.

Artwork by Eloghosa Osunde.

Back then, one of my favorite leashes to use on myself was a Scripture from Ephesians 4:1. Paul wrote: “Therefore I, a prisoner for serving the Lord, beg you to lead a life worthy of your calling, for you have been called by God.” I loved his words there because they spoke to something already on the inside of me: a sturdy addiction to a set standard, height marks on the wall. There was something in me already easily seduced by the faith other people put in me, because to be believed in is to have the best of oneself amplified, and what could be better than that in terms of fortifying one’s right to a body, right to a life? So there was me, always—on the way to class, in the shower, on the bus, in my room, in my sleep—reciting it to myself, confessing it over and over in my head: Walk worthy. Walk worthy. Walk worthy.

When I fell short of what I thought that meant, the whips I sent to my back were fearfully and wonderfully made. I’d left church—the place that made that kind of thinking possible—for a reason, but some of the lessons stayed. When I started writing my way toward the freedom that’s now mine, it was because I wouldn’t have survived otherwise. I was coming from a life of “must” and “should”; such teachers those words are, reminders that letters can keep you stuck, can make it too hard for you to show yourself mercy, and that we die without mercy. There are Scriptures for mercy, and for everything else. When I was younger, the ones we memorized at home were called confessions. We’d say them over our heads in unison: God fights for me and I hold my peace. Greater is the god in me than that which is in the world. Nothing can separate me from the love of God. I flourish like a palm tree and grow like a cedar in Lebanon. I learned quickly that to memorize the Word was to be guided by its content—to be, always, in a state of prayer. To find Scripture I trusted was to be kept company from the inside and, one is likely only to obey what one knows and what one can easily remember. “This is the best thing I can give you,” my parent would say. I still agree. It was. The Word was always there, and so, inside my body, I never felt alone.

Now, postchurch, I turn to poems and songs in place of Bible verses, reciting words I trust over and over in my heart, assimilating slowly. Toni Morrison’s “You are your best thing” is a handy hook. A quote from Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters is an affirmation: “I love myself in error and in correctness, waking or sleeping, sneezing, tipsy, or fabulously brilliant. I love myself doing the books or sitting down to a good game of poker …” It reminds me—in a Psalm 139:1–18 way—that love follows me, that I do not have to be good in order to choose myself, to take my own side. “Somewhere Real” by Shira Erlichman is a Psalm of acceptance. You breathe better, I’ve found, when you remember that you don’t need to go through a thousand divorces from the selves you want to leave behind: you can just accept them. Most of what we fear and regret gets bored and floats off if we just look at it, anyway. Bassey Ikpi’s “The Heart Attempts to Clear Its Name” is a letter from the heart to my sometimes bratty mind, my body, the rest of me—a reminder that you do not, as Florence Welch has written, “beat your own heart”; that even when I cannot fight for myself, my heart works to make sure that my life remains possible. Sometimes the body—a realm unto itself—insists on being remembered, and we’re blessed when this insistence can come through language instead of force. The tone of Ikpi’s poem shakes me the way Job 38 used to, with its self-spinning questions. When the shame appears, when forgiveness seems elusive, when the truth around the fatigue is dark, Morgan Parker’s “Since I thought I’d be dead / by now, everything / I do is fucking perfect” on repeat does the work. It reminds me that the tunnel I used to be in was too everlasting for me to forget that it took great strength to exit it in the first place. On the rough days, in the tough times, when nothing in the world makes sense, I marry Gwendolyn Brooks’s “To The Young Who Want to Die” with some jazz—and together, they make me from scratch. Some songs say what I’m thinking before I can find the words. Msaki and Sun-El Musician’s “Tomorrow Silver,” for instance:

I’ve been thinking about peace and how to keep it once I’ve found it

I’ve been thinking about money and how to keep it once I have it

I’ve been thinking about love and how to keep it once I’ve made it

…