The Paris Review's Blog, page 84

April 25, 2022

Stealing It Back: A Conversation with Frida Orupabo

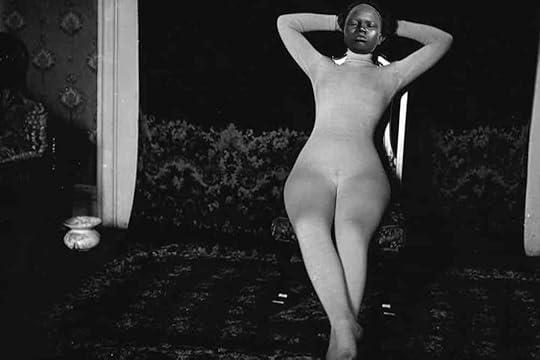

Frida Orupabo, Last Night’s Party, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Frida Orupabo, an artist and former social worker, was born in 1986 in Sarpsborg, Norway. Like most millennials, she can remember a life without the internet—she bought her first computer when she began attending the University of Oslo, but still didn’t have access to Wi-Fi. She started scanning old family photographs, making them into collages and eventually sending them to a printer, who bound them into books. The altered photos allowed Orupabo to imagine a new version of her relationship with her parents—she was, in other words, devising an alternate history of the present, and that same flair for fantasy characterizes the larger collages she is now known for. Since those early days, Orupabo has moved away from using personal ephemera as source material. Instead, drawing images from eBay, Tumblr, Pinterest, Instagram, and online colonial archives, she stitches seemingly disparate worlds together like a rogue seamstress. In the resulting works, things are usually a little bit off: a winged head may be without a body, or a body in repose may be interrupted by a disembodied head. Most of her subjects are Black women, and nowadays they quite literally take up space. After the artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa noticed her work in 2013 on Instagram, where she was curating series of images, film, and audio loops under the handle @Nemiepeba, he asked her to participate in “A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions,” his 2017 show at the Serpentine Galleries in London—and so she began printing out her images, fashioning life-size works whose various parts she held together with clothing pins. Now, Orupabo lives among these paper women. Her Oslo studio, from which she spoke to me on Zoom this spring, is also her apartment, and so when she eats, she watches them, and when she sleeps, they watch her, too.

INTERVIEWER

You initially made collages using family photos. Do you locate the genesis of your artmaking in how you grew up?

ORUPABO

I grew up in the late eighties and early nineties, in an old industrial city an hour’s drive from Oslo. At that time, there were not many people there who were not white. My sister is like me, but my mom is white, and my father went back to Nigeria very early in my life, so I grew up in a family that was predominantly white. As a child, I used to paint and draw, but I started to work in the way that people would now recognize when I was nineteen, twenty. I bought a scanner that could digitize film photos and used it to save family slides on my computer. I started to manipulate them using Microsoft Paint, of all things, and through that process I began to create my own narrative of my family history. I was using photos of my mom, my father, my sister, and me, trying to work through feelings that were attached to that family unit. Collaging was a way of reworking emotions and also reworking things that had happened, that continue to happen. So it was really linked to my identity, a crisis in my identity, and, finally, a healing process.

When I got access to the internet around two years later, I started to use found material. Since then, I’ve never gone back and worked with my own face or with my mother’s face. The collages I make are very attached to who I am, what I want to say, and how I feel, but I speak through other faces now.

INTERVIEWER

What were you studying when you began making the collages?

ORUPABO

My bachelor’s degree was in development studies, which was terrible. It was really Eurocentric. I was introduced to Black feminism very late. The courses I took on the side were linked to critical gender and race studies, and a professor on one of those courses suggested I read bell hooks, which was eye-opening. The way she writes is theoretical but also really personal, and I suddenly felt I had a language that I could use to understand my experiences as a Black woman living in a white society.

I switched to sociology for my master’s degree, and when I graduated, I didn’t want to continue with research at the university—I wanted to work with people. I got a job providing social services at a center for sex workers, doing low-threshold work: going out, speaking with people, and directing them to our clinic if they had any health related issues or issues with the police, or wanted information concerning housing, work, immigration policies, and so on. It was interesting, coming to terms with what I thought I already knew about who was selling sex and why. I was in constant dialogue with different people who shared their experiences and thoughts with me, many of whom were Black women, while simultaneously working in a field where there weren’t so many people who looked like me, where I also encountered racism.

I made art at the same time—collaging was a way of relaxing when I got home—but when I had my daughter, I realized I couldn’t do both, it was impossible. So I decided to quit.

INTERVIEWER

What was it about collage as a form that appealed to you?

ORUPABO

I remember I read an interview with David Hammons in which he was speaking about these body prints he makes, and how they express “exactly who I am and who we are.” By collaging, I’m trying to get to who we are. I don’t trust my hand to draw or to paint—I’ve never been so good at it—so collage is a way to get the representation right. It’s like going into a store: you want to be in a particular dress, and you can’t afford it, but you can put it into your collage. That’s how my collages started: I collected images that I liked, and then I sampled them in my work.

INTERVIEWER

That aspirational, acquisitive impulse seems like part of the larger element of fantasy at play in your work. You want these things to exist together—a particular face, an arm, a dress—and they can’t exist together, except insofar as you’re able to place them together in a collage.

ORUPABO

Sometimes you have to force it. And that’s what I like, to be able to make something that doesn’t otherwise exist. You have to do it yourself, to write it yourself, and you have to write yourself in. That’s what I’ve been doing for a long time: writing myself in, and creating things that I find beautiful at the same time. This kind of work gives me energy.

INTERVIEWER

There’s an affectless quality in a lot of the faces that appear in your collages, despite the fact that they’re so often surrounded by oddities. That’s not to say that the collages themselves are affectless: some are angry, others haunting, melancholic. But it’s difficult to read into the facial expressions themselves anything like anger, or love, or happiness, or dissatisfaction.

ORUPABO

When I was creating work for my 2020 exhibition “Hours After,” at Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg, I was dealing with themes of pregnancy and labor. I showed labor scenes and people with their babies, and I included mothers who wore ambiguous expressions. Were they feeling joy? Were they present with the child? I’ll put a face on a body, and although the body can be active, it doesn’t go with the face, which can be at rest or asleep. I am interested in creating works that show the ambivalence and complexities that often get left out in representations of Black people. Is it possible to show a naked body without it being objectified and sexualized? Can you portray Black anger without it being generalized? Sometimes, as a Black woman, I feel very locked in. I don’t like to speak so much, and I don’t like to write. So I’m left with the visual, which, for me, feels much more open than language. It can grab things that language can’t.

INTERVIEWER

Originally, your collages were purely digital—you were finding images online, piecing them together, and the completed work lived on the computer. Now, though, you produce these sculptures that exist in space. There’s something uncanny, I think, about encountering images intended for the internet as physical objects. What did that migration signify for you?

ORUPABO

Until Arthur Jafa asked me to show work at his exhibition, while I was still a social worker, everything I had made was digital. I considered the collages to be done when I saw them on my computer, so I never thought of doing something physical. Plus, I’m a lazy person, so I never would have done it if someone hadn’t said, “We need something right now.” My first idea was just to enlarge the collages and print them on a big sheet of paper. But then I thought, This is too flat. I tried printing out more layers, and then I had to find a way to keep the layers together. I had the idea to use pins. I couldn’t trust glue—it had to be something that went through the paper.

Once they were printed out, the presence of the collages was very strong. They were three human-sized women, and I hung them up on the wall. At that time, I lived in a very small apartment, so we really lived together. It was intense and wonderful, because I felt that I was onto something.

INTERVIEWER

Your description of sharing a room with the collages makes me wonder whether you think of them as characters.

ORUPABO

I think of them as subjects. Often, I choose people that stare back at you. I’m usually working on the floor, so when I start the process of pinning them together, it sometimes feels a bit strange. Some have said that it seems as though I’m working on an operating table. Most of the faces I use are from online archives that I find by Googling things like, “colonial, vintage images.” Sometimes I’ll come across an entire archive—that is the best. I’ll often enlarge an image by hovering my mouse over it, and then I’ll take a screenshot of that. In other words, I’ll steal it back.

INTERVIEWER

Do you consider theft integral to your artmaking? I sometimes wonder if being a thief is the only ethical position one can claim in relation to institutional life.

ORUPABO

Most archives are not forbidden to enter, but you’re only allowed to look, not grab. There’s pleasure in breaking in and snatching, and there’s anger behind it, too—especially when I encounter images that have watermarks, images that are owned by institutions and probably white people. Often there’s no name attached to the person depicted, because it’s not like the person who owns the image has done any research. At best, it’ll say “slave girl.”

INTERVIEWER

How do you think about those informational gaps you encounter in the archives? Is there a desire to research the images you use, or is it important to not research them, and let them take on another life through your work?

ORUPABO

I’m ambivalent: sometimes you come across archives that are more beautiful than ugly, and you want to know more, and other times you come across archives that make you puke—you don’t want to look for a long time, and, in fact, you don’t want to have anything to do with them. So it depends, but no matter what, you are constantly reminded of how the world is operating.

Maya Binyam is a contributing editor at The Paris Review.

Frida Orupabo’s portfolio is featured in the Review’s Spring issue.

April 24, 2022

Listen to Henri Cole Read Poems from the Paris Review Archive

Henri Cole IN NAGS HEAD, NORTH CAROLINA, 1978.

What a pleasure to read around in the Paris Review archive of poems from its pages. I experienced anew the capriciousness of taste and the ardor of individual decades. As the guest editor of the Review’s daily poetry newsletter this week, I chose poems that I consider keepers for my lifetime. All are by poets I read avidly in my twenties and thirties, when I was still unformed and seeking liberators. For me, Baudelaire, Miłosz, Walcott, Gregg, Glück, Wright, and Schuyler are masters in the craft of language. Their words (assembled into art) transport me. Even now, at sixty-five, I am always looking for new liberators. Thank goodness poetry is unkillable. Thank goodness poetry is continually renewed by a rediscovery of the past, by new translations, and by the ache of the young.

Listen to Henri Cole read his selections here, and read his commentary below.

“It Is the Rising I Love” by Linda Gregg

This poem is a glorious representation of the mind and soul of Linda Gregg, who died in 2019. When her first book, Too Bright to See, was published, I was in my twenties. With its strange innocence that seemed to have symbolic meanings, it captivated me. I value the neat way her poems communicate the darkness that surrounds mankind. As Joseph Brodsky said, her poems have a “blinding intensity,” like “lightning” or “heartbreak.”

“ The Crystal Lithium ” by James Schuyler

James Schuyler is my favorite New York School poet. “The Crystal Lithium” is the first of his great, long-lined, long poems. “All six senses are at play, plus those of tone and form,” as James Merrill observed of this shy poet’s wonderful poems, which prove that a “ ‘reverence for life’ doesn’t have to be boring.” Readers of this poem should remember that lithium compounds, known as lithium salts, are used as a psychiatric medication, primarily for bipolar disorder.

“Figs” by Louise Glück

Louise Glück is a marvelous poet. There is so much effortless intelligence in her poems. In just a few lines, she creates a tone with the peculiar power to draw us deeply in. “Figs” is so sharp and clear a narration, so ravishing it seems to declare simultaneously something familiar yet new about the journey of one soul, about the pulse of the earth, and about the ebb and flow of marital love.

“ The Sea Is History ” by Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott was my teacher. It’s difficult for me to be objective about this magisterial poet. I first read ‘The Sea Is History’ as a young man, in Walcott’s beautiful book The Star-Apple Kingdom, a book with a public dimension that traces Antillean history. Among other things, Walcott is a master of simile, and I love his lamenting seafarer’s tone. For me, his poems reestablish poetry’s responsibility to our common, troubled, historical past.

“Lying in a Hammock at a Friend’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” by James Wright

This free-verse sonnet is, of course, inflected by Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” The explosion of Rilke’s concluding line—“You must change your life”—becomes, in James Wright’s poem, “I have wasted my life.” The simplified beauty of his language and its truth-telling seem to me as enduring as classical Chinese poetry. I’m so grateful for the dark turn this poem makes at its finish. A man’s life is not a thing to sentimentalize.

“My Faithful Mother Tongue” by Czesław Miłosz

Years ago, when I lived in Japan, the country of my birth, I felt most at home in the bookstore aisle of publications in English. For Czesław Miłosz, a great servant of the Muses, the Polish language was his home, but he recognized that it was home, too, to “informers,” to the “debased,” and to the “unreasonable.” Still, Miłosz remained faithful to his mother tongue, for it was also for him a place of incarnation and renewal.

“ Epigraph for a Banned Book ” by Charles Baudelaire

I grew up reading Richard Howard’s translation of Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal, and it remains for me the standard version, even at its campiest, fiercest, and most theatrical. I adore Baudelaire’s breach of decorum, his openness to sorrow and tenderness, and his spleen. A hundred and fifty years later, his poems sound to me so original and contemporary.

Henri Cole was born in Fukuoka, Japan. He has published ten collections of poetry, most recently Blizzard, and a memoir, Orphic Paris. A selected sonnets is forthcoming.

April 22, 2022

The Review Recommends Gail Scott, Harmony Holiday, and Georgi Gospodinov

“Pale blue sky beyond anarchy of chimney pots,” writes Gail Scott. Photograph of chimneys in Montmartre by Dietmar Rabich. LICENSED UNDER CC BY-SA 4.0.

I first encountered Gail Scott’s sentences in Calamities, a book of glorious short essays by Renee Gladman, one of Scott’s closest readers. “These were the shortest sentences I’d ever seen,” Gladman writes, “yet they were not the kind of sentences that allowed you to rest when you reached the end of them. They pointed always to the one up ahead … They pushed you off a balcony; they caused fissures in your reading mind.” When I finally read Scott, it was two novels back to back: Heroine, a young lesbian’s feverish account of living in a Montreal boarding house in the early eighties, and My Paris, the precisely calibrated diaries of an often depressed Quebecois woman living in Paris. It was easy to see how you might want to live in Scott’s sentences forever, or, as Gladman did, transcribe them from memory onto your living room wall. I read them again and again for the pleasure of pure description; for the unnamed women who move through them without warning, wearing loose black pants, an olive-green jumpsuit, silk socks, and irrepressible perfume; for Scott’s impressions of Quebecois political-left consciousness in the second half of the twentieth century. “Heroine is more a work of reading than of writing,” Eileen Myles wrote in the book’s introduction, which was also published by the Review in 2019. It’s the deceptive work of accumulation, too, that drives both these novels—in the kind of ravenous prose that seems to revise itself as it’s already in motion. From My Paris: “The marvellous is to be had. I thinking at 5:30a. Looking out window. Pale blue sky beyond anarchy of chimney pots. You just have to pierce the smugness of the surface.”

—Oriana Ullman, intern

“History repeats itself.” This repetition, the relentless circularity of time, is the subject of Time Shelter, the latest novel by the Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov, translated by Angela Rodel. It follows an unnamed Bulgarian narrator as he finds himself drawn into the creation of a Zurich-based “clinic of the past” for Alzheimer’s patients, dreamed up by Gaustine, a philosopher prone to uttering enigmatic sentences like, “No one has yet invented a gas mask and bomb shelter against time.” The clinic is neatly divided into floors, each of which is dedicated to a decade of the patients’ lives—but these floors eventually begin to spill over into one another. Mayhem ensues. Soon, nonpatients want in, too, and politics enters the scene. Referendums are held: Should Europe be returned to its past? Strewn with aphoristic meditations on the history, fiction, the nature of time, and the construct of Europe, this is a novel that feels both prescient and like a dream. Or like a moment of déjà vu: At the book’s end, is it 1914 in Sarajevo, a time and place that decided the course of modernity as we know it—or is it a reenactment of that assassination, happening in 2024? At what point does that which is reenacted merge with that which is real? As Gospodinov illustrates, it’s pointless to bet against the past. The house always wins.

—Rhian Sasseen, engagement editor

I’ve been spending some time with Harmony Holiday’s startling new book of poetry, Maafa, which is both verbally dense and free-flowing, terrifying and moving. Maafa is a Swahili word for “catastrophe” or “holocaust,” and the book’s lyric sequences are preoccupied with questions of how to understand, represent, and maybe even channel the overwhelming history of violence against Black lives. From Holiday’s vantage, the answers are by no means simple—at one point, a voice exclaims, “I’m reluctant to write this shit.” The difficulty of doing a catastrophe justice is entwined with the further tragedy of its potential co-option. The result is a field of fragments that oscillates between Ancient Egypt and “Fenty / Beauty ambassador”: destabilized but driven, at war with itself and with the narcotic of easy narratives, and ultimately visionary in its search.

Black music is a recurring subject in Holiday’s writing, and the book calls on a pantheon of sonic ancestors: Lena Horne, Sun Ra, Al Green, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. They are the points of contact by which a stolen history might be clawed back: “black music is the music of forensics // all my dead friends come to me as songs.” Resurfacings of stark violence crash into quicksilver wordplay: Holiday’s language is always restless as it cascades over itself, mischievous and never quite pin-downable, like the theme of a jazz chart that is taken up and reinvented in improvisation. The words run across the page in staggered spacings, as though written by a musician trying to hold the rhythm of the sentence in her pocket. Survival, Holiday tells us, is an ongoing struggle, something that is fought for between every word.

—David Wallace, advisory editor

We Need the Eggs: On Annie Hall, Love, and Delusion

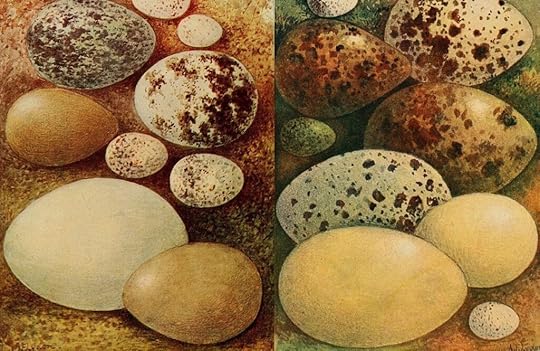

TWO ILLUSTRATIONS BY RICHARD KEARTON, 1896.

One night, my stand-up comic brother, David, and I were sitting on my couch, talking about the joke that concludes Woody Allen’s 1977 film, Annie Hall. We’d watched the movie together dozens of times growing up, and we’d always assumed that we interpreted the ending—about how people get into relationships because we “need the eggs”—the same way. That night, we discovered we did not, and even after much talking, we found we couldn’t agree on the joke’s meaning. In the weeks that followed, I longed to restage and expand our conversation, and hopefully to answer some of the questions it had raised, so I invited a few other people into the discussion: Zohar Atkins, a rabbi and poet; Nathan Goldman, a literary critic and editor; and Noreen Khawaja, a professor of religion who has written a book on existentialism. Could we, together, get to the bottom of this profound and amazing joke?

DAVID HETI

The joke came up one night when Sheila and I were talking.

SHEILA HETI

I think we’d been talking about relationships.

DAVID HETI

And I said how I understood the joke and then Sheila had a completely different interpretation. We couldn’t settle on what it meant.

SHEILA HETI

Let me read the joke. It’s at the very end of the movie, and Alvy is talking about meeting Annie for coffee, and he says, “After that it got pretty late and we both had to go, but it was great seeing Annie again. I realized what a terrific person she was and how much fun it was just knowing her, and I thought of that old joke—you know, this guy goes to a psychiatrist and says, ‘Doc, my brother’s crazy! He thinks he’s a chicken!’ And the doctor says, ‘Well, why don’t you turn him in?’ And the guy says, ‘I would, but—I need the eggs.’ Well, I guess that’s pretty much now how I feel about relationships. You know, they’re totally irrational and crazy and absurd, and I guess we keep going through it because most of us … need the eggs.” The funny thing about the joke for me is that there are no eggs. Just because the brother thinks he’s a chicken doesn’t mean there are eggs. And David was like—

DAVID HETI

It’s not about there being actual eggs! Lovers go into a relationship because they each get something out of it, and whether there’s something objectively there doesn’t matter. Each party gets the messiness and the intimacy and whatever you get—that feeling of something being there. Alvy Singer has all these divorces, but he’s saying that we keep doing it, ultimately, because we’re crazy: one of us thinks he’s a chicken, and the other one’s on the psychiatrist’s couch, thinking he’s getting eggs.

GOLDMAN

That’s interesting, because I’ve been wondering why there are two deluded people in the joke, and it seems like you’re suggesting that it’s because it’s about a kind of delusion that requires multiple participants—even though in the joke, the speaker at first frames it as only his brother’s delusion, before he reveals he’s participating in it.

SHEILA HETI

I think it’s true that a romantic relationship is a sort of delusion between two people. There’s an agreement to imagine something together, and you create this idea of each other and the relationship and what you mean to each other. And when one person stops imagining all this, basically that’s when the whole thing falls apart.

KHAWAJA

I saw the two brothers not as two people in a relationship, but as two versions of Woody Allen—or Alvy. One has the perspective of, “It’s crazy, I’m living in a fantasy of this other person and myself,” and the other one is saying, “Yet I’m still getting something out of it, so he’s seeing it from both sides.” And to Sheila’s point, I think he’s saying that there are eggs. The funny thing is, there shouldn’t be eggs, but there are eggs.

DAVID HETI

I think it’s important that the person speaking knows it’s a bit crazy what he’s proposing. He has to have that self-awareness for it to be so funny.

SHEILA HETI

I don’t think he knows he’s crazy. I think “I need the eggs” is the straight-man line. It’s like you originally said, David. He believes there really are eggs.

GOLDMAN

So he’s cognizant that his brother is crazy, but not that he is?

SHEILA HETI

I think so. Which is another reason why this joke is so perfect about relationships, because we always think the other person is crazy but we’re not. All we talk about when we talk about our relationships is how crazy the other person is.

ATKINS

I can’t even track how many layers of meta this joke is, but one that just came to me is the idea that maybe the joke doesn’t actually make sense, but we need it to make sense, because we need the eggs. Why do we laugh at a joke? Is it because the joke is funny, or because we need the release? So we’re almost complicit in the insanity, because he tells a story that doesn’t really hold together, but we need the closure, the laughter, so we’re brought in. Likewise, he’s both the butt of the joke and the one telling it. In the classical form of a parable, there are two parts: there’s the allegory, and then there’s the interpretation, and usually the interpretation is given by somebody else. A classical parable would end with just, “I need the eggs,” and then another person would come and say, “Oh, it’s like relationships.” But here, where does the parable end—when the joke ends, or when he steps out of that role to interpret it? By being the interpreter of his own parable, Woody Allen extends the boundary of the parable to include the interpretation. And in doing that, parable makes the interpreter less superior to the interpreted, because it shows that you can be a very rational, meta, balcony-view kind of person, and be just as crazy as the people you’re looking down on.

DAVID HETI

Why does that make the interpreter inferior? I think that elevates him. First off, this is not Alvy Singer telling the joke—this is Woody Allen, the director, so he is outside it. It’s like the opening joke: “I would never want to belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.” Here you have one guy who thinks he’s a chicken, which is a problem, and another guy who thinks he’s getting eggs, and that’s a problem, too, but you have these two things together and it turns out it works out beautifully!

SHEILA HETI

I don’t agree with you necessarily that the person who tells the joke is Woody Allen and not Alvy Singer.

GOLDMAN

I agree, I don’t think that’s clear. But I’m also not sure I agree with Sheila that the narrator doesn’t come to understand that he’s crazy. I think this question has stakes because it relates to the question of whether there are delusions you can participate in despite being self-aware—like free will, maybe. Is there a role for self-awareness in delusion? Does humor let us live self-awarely in delusion, or does it only diffuse it?

ATKINS

I’m now thinking of a Hasidic story about a guy, a prince, who thinks he’s a chicken, and he refuses to sit at the table, and he’s going underneath the table and eating the crumbs and making chicken sounds, and the king hires all these wise people to come visit and cure the son of his pathology, and none of them succeed. Then someone goes under the table with the guy and pretends to be a chicken as well. After he imitates him for some time, he’s like, “Wouldn’t it be fun to pretend to be human?” Like Alvy’s joke, it’s about being in on someone’s pathology as a way of healing them.

DAVID HETI

I think one joke that we’re all forgetting about is Alvy’s comment to Annie Hall on the plane that a relationship is “like a shark”—“it has to keep moving or else it dies.” Part of the magic of a relationship is that you can’t hold it down, you can’t put a finger on it or resolve it. It exists in the tension. Same with the joke. We are trying to resolve it, but we can’t.

SHEILA HETI

Right. If the guy accepted that his brother was a chicken, like very calmly—“This is great, he’s a chicken, and I get the eggs”—there wouldn’t be the anxious tension which keeps romantic relationships interesting. In some way, his dissatisfaction with the fact that his brother is a chicken is the eros—it’s the excitement that keeps the shark of the relationship moving. The answer is not, “Be happy that he’s a chicken and don’t see that as crazy.”

KHAWAJA

Nor is it to find the perfect person—

SHEILA HETI

—who doesn’t think they’re a chicken.KHAWAJA

And who satisfies all the things you think you want.

SHEILA HETI

Yeah, it wouldn’t be a better brother who didn’t think he was a chicken, but didn’t give eggs.

ATKINS

Exactly! He thinks he wants a life without struggle, and he’s looking for the perfect soul mate to ease all that tension, when in fact it’s the tension itself that’s producing the love interest.

DAVID HETI

And it’s the tension itself that creates … well, life. Because eggs represent fertility, life.

SHEILA HETI

But I think my original question was, Are there eggs, actually, in a relationship? Like, what are we getting? Are we getting eggs, or are we getting the illusion of eggs, or what?

GOLDMAN

At the risk of evading that question, it’s interesting to me that in the joke, it’s the narrator, not the brother, who introduces the eggs. When he says, “My brother thinks he’s a chicken,” that implies eggs, but it’s he, the narrator, who actually brings them up. I think that might help us understand what the joke is saying about relationships. Because we only know for sure that the eggs exist for one person—for the one who’s talking to the doctor.

SHEILA HETI

Right, we don’t know if the eggs exist for the guy who thinks he’s a chicken.

GOLDMAN

He could think he’s a barren chicken.

KHAWAJA

The classic chicken-and-egg joke is also just sitting there! “Which came first?” If the joke is refuting the idea that you can have the eggs without having the chicken, then it actually becomes a summary of that other joke. I think that’s floating somewhere in the funniness. And I feel like the eggs could be … whatever illusion yields. Like, not real eggs or false eggs, but whatever the fruit of illusion is. The one other egg moment in the film is when Alvy’s on the street doing a survey with the passersby, and he asks an Upper West Side older gentleman, How do you and your wife make it work after all these years? And the guy’s like, “We use a large vibrating egg.” The guy gives him a very reasonable answer, but Alvy is like, “Well, you ask a psychopath for advice, that’s what happens.” His reaction to the possibility of a vibrator is to be scandalized! He thinks it’s psychotic because it’s artificial. When I saw that, I thought, it’s not that mysterious why he and Annie failed. He tried to stop her from smoking pot before sex, and that was where everything went completely askew. Alvy is like, I want the eggs that come from when you’re relaxed; I don’t want you to use something artificial to get there. He wants her to get there “naturally.” So there seems to be some kind of echo there—he wants the fruit of the illusion, but he can’t accept the intentionality; that techniques may be needed to produce the illusion.

ATKINS

Right, you can’t pick and choose the things you want in a person. He says, “I don’t like that my brother’s insane, but I do like the eggs,” and the response to that is, “If you want the eggs, then you have to embrace his crazy.” If you want to reject his crazy, fine, but you don’t get his eggs. I suppose that’s a way of saying the eggs are sort of real.

GOLDMAN

And actually, the thing that you think is a problem sometimes produces exactly the thing you want. There’s that recurring thing where Annie is like, “You don’t think I’m smart enough.” And it’s true that Alvy does think that, and it annoys him. But he also enjoys his paternalistic, educating role.

SHEILA HETI

So what are the eggs? Not in the joke—but in relationships.

GOLDMAN

I could answer with respect to what I like in relationships, or what the film says about what’s valuable. But do people participate in relationships for the same reasons, fundamentally? I’m not sure. I think it speaks to that uncertainty that within the context of the joke, the eggs are a cipher, a determinate indeterminacy. An egg is a nascent, generative image of pure emptiness, of negativity, of potentiality. It could be anything.

SHEILA HETI

Yeah. I think that’s why the joke works—because when we hear we “need the eggs,” we all know what that means to us. I know what the eggs I need are. It’s such a nice mood to end the movie on. And the hardest thing to do in a work of art is to conclude it well.

GOLDMAN

One of the things that I think it makes a great conclusion is that, for a movie that’s very ironic and modern, it ends with a moral, in a strangely classical sense—relationships are like this. But all the things we’ve been discussing—the indeterminacy and irresolution and the fact that it’s a joke—undermine that didactic quality. So you get both at once. Here’s what relationships are like, and also a question mark.

SHEILA HETI

Here’s what relationships are like—we don’t know what we’re getting out of them.

KHAWAJA

Yes, and the conclusion of the movie—like the brother who thinks he’s a chicken—passes the crazy on. The first word I thought of when I heard this joke was contagion. This guy notices his brother is crazy, but in the midst of trying to understand his crazy or relate to it, he gets a little bit of the craziness. And the lack of resolution in the joke means it keeps spreading, the crazy dribbles down to us. There’s something giggle-funny about that—not Aha! punch-line funny, but like, ew, icky funny.DAVID HETI

This whole thing reminds me of that scene in the movie where he’s at the party and is watching the Knicks and his wife comes in and Alvy says, “All those PhDs are in there, you know, like, discussing modes of alienation and we’ll be in here quietly humping.” We’re not enjoying the joke! No one’s enjoying the joke here!

SHEILA HETI

And no one’s really answered my question. What are the eggs?

KHAWAJA

I think the eggs for me are the feelings I get from the version of me that my partner creates through their delusion. Whatever that fantasy they have of me, and of themselves in relation to me, yields—that’s the eggs. And maybe I’m suspicious of it, too, because they’re not really right, but it’s still what holds me there.

SHEILA HETI

What holds you there is their image of you?

KHAWAJA

The thing I can sort of see through about the way they see me. With one eye. I’m like, “Oh, I can see that that’s maybe not right.” Maybe there’s some fantasy element in that, but it gives me this hope, right? That fantasy or that generativity, the fact that they’re generating possibilities …

SHEILA HETI

And the way that they see you is usually a picture that’s better than yourself and worse than yourself.

ATKINS

I’m just curious to know—in the brother-brother relationship, who’s doing the work? Who’s being centered? We get the story from the point of view of the one saying, “I need the eggs,” but we don’t get the chicken’s side of the story.

SHEILA HETI

Instinctively, it seems to me like it’s the chicken that’s doing the work, because that’s a lot of work: to be a chicken. And to believe yourself a chicken.

GOLDMAN

And the physical act of producing eggs is also a lot of work.

KHAWAJA

To believe yourself a chicken sufficiently enough to produce some kind of egg that the other person is getting—there’s a lot of work in that belief!

GOLDMAN

But isn’t having a delusion no work at all? I wake up in the morning and effortlessly believe all kinds of things about myself that aren’t actually true. (Pause.) I am trying to think about whether the joke only works if the brother’s not there. Or is there a version of the joke where the brother is there that is funny in a different way, and that tells us something different?

DAVID HETI

Maybe the other brother is on the couch talking to his psychiatrist, saying, “He wants eggs from me!”

SHEILA HETI

And why is it two brothers in the joke? If what we’re meant to do is extrapolate this to a romantic relationship between Alvy Singer and his girlfriends and wives, why isn’t the joke, “My girlfriend thinks she’s crazy?” Why is that not as good of a joke?

GOLDMAN

Because brothers can’t break up with each other.

ATKINS

Alvy can keep breaking up with specific people, but he can’t break up with the concept of a relationship—the brother is the stand-in for that. The family relationship represents the idea of relationship itself, in a way that actually makes the problem of how you choose a partner a specifically modern one. It almost seems easier to be assigned one and be told, “This is your brother, go and figure it out.”

SHEILA HETI

Watching this movie I did kind of feel like, Well, their problems weren’t so bad that they should have broken up. Like, okay, Alvy is a bit of a drag for Annie. She wants to have more fun. But why can’t she have fun apart from him? And they do love each other. So, based on what Zohar is saying, the answer for him is, Don’t break up. You need the eggs. You need the relationship. Not that the moral of the movie is that they shouldn’t have broken up, but that’s … some wisdom.

ATKINS

I feel like he takes it in an opposite direction, though—I’m going to be a serial dater my whole life, because “I need the eggs.”

DAVID HETI

But those aren’t the good eggs. Those aren’t the deep eggs—the real craziness you can get to in a long-term relationship.

ATKINS

So does he misinterpret his own joke? Or is the joke sufficiently indeterminate that it’s more of a Rorschach test for him and for us to figure out how we feel about relationships?

GOLDMAN

I think the joke and the film are agnostic about the question of lifelong monogamy. It’s interesting that the joke follows the scene where they meet and he says “how much fun it was just knowing her.” At that point, he isn’t saying, We were really good together, we should get back together. So the movie kind of brackets the question of the best way to produce the eggs, or to get them.

KHAWAJA

I agree that it’s agnostic on the monogamy question, and I don’t know that you need endurance for eggs. I think the eggs come at all sorts of points.

GOLDMAN

It’s interesting that he says, “That’s pretty much how I feel about relationships” and not “romantic relationships.” I mean, in the context of the film and how we generally use that word, it makes sense to interpret that narrowly—romantic, sexual relationships—but could we also take it as true about relation in general?

SHEILA HETI

No, I think the joke is talking specifically about romantic relationships, because you wouldn’t say that friendships are “totally irrational and crazy and absurd.”

GOLDMAN

Why not?

SHEILA HETI

Because you have a degree of choice over who your friends are, but you don’t choose who you’re sexually attracted to, and you don’t have any agency over who you fall in love with. I think it’s the wild not-making of a choice that makes romantic relationships crazy and absurd. “How did I find myself in relation to this person whom I can’t seem to get away from, but whom I actually don’t want to get away from?” With a friend, it’s a bit more understandable—you have things in common. The reason you spend time together makes more rational sense.

ATKINS

Before the brother comes along and says, “Hey, I have these eggs,” Alvy Singer doesn’t know that he needs them. He’s not walking around saying, “I need eggs, where can I find some?” It’s only by being offered the eggs that he discovers himself to be someone in need of eggs. He actually discovered something about himself and what he needs through that surprise romantic encounter. And he couldn’t find that part of himself if he was just looking to have things in common with people. So it’s not just that we have a need for the eggs—we also have the need to discover the things we didn’t know we needed.DAVID HETI

There’s a sadness to that, I think. “I need the eggs.” That line could be delivered in many different ways. “Well, I need the eggs.” It’s kind of an admission of his failing. It’s out of his hands.

SHEILA HETI

In friendship, there’s actual eggs. In a friendship, you get real eggs.

(Everyone laughs.)

KHAWAJA

Well, I think it depends on whether there are erotically charged elements to the friendship. Friendship can be magnetic, too.

SHEILA HETI

That’s true. Certain friendships can also feel fated, absurd and irrational. Do you guys think the crazier, more erotic, more combustible relationships have better or bigger or more potent eggs than romantic relationships that are more placid, or do the more placid, amicable relationships have bigger and better eggs? Or is the joke making no comment on the quality of the eggs in relation to the type of relationship?

KHAWAJA

I don’t think the quality of the eggs is dependent on the tempestuousness of the relationship, because if we’re tying the eggs to fantasy, then we have to acknowledge that a placid relationship is full of fantasy, too. You think of the other as stable, as unchanging, and you’re both playing along with that: “We do things this way, and this is what we like, and it’s not going to change.” But you both probably know, somewhere, that it could change. You could have a tempestuous relationship that had terrible eggs, or a very placid relationship which was very fictional, actually, but which gave you tons of good eggs.

ATKINS

I think I agree with Noreen that we get the lovers we deserve. In that relational sense, if you are a placid-seeking person, you get a placid-seeking person in response, and that’s great. But I do think that on a more absolute level, just as there’s excellence in any realm of craft, there probably is excellence in the realm of relationships. Some relationships are brave and others are less so, and I think the braver the relationship, the more conflict will be surfaced, and therefore a deeper harmony will be achieved. Therefore, better eggs.

SHEILA HETI

What constitutes bravery in a relationship for you?

ATKINS

I think a willingness to go to uncomfortable places. I guess I’m a brooding type, and a person who likes to self-examine, so I value that in a partner. But if skiing with your partner is your thing, fine, that’s not worse than talking about your childhood wounds.

SHEILA HETI

I’ve never heard a person so confidently suggest that excellence in a relationship equaled bravery. It’s like you’re saying bravery in a relationship equals beauty in a work of art.

ATKINS

Now that I hear it reflected back, I’m not sure that I would stand by it.

GOLDMAN

I think it’s an interesting claim with respect to the film, because while you could make the argument that Annie Hall is a brave work, or a very self-assertive one, in some ways the defining characteristic of the movie—and the paradigmatically Jewish American, mostly male aesthetic it embodies—is actually a kind of cowardice. Or maybe that’s not right, but a neurotic, self-deprecating—

KHAWAJA

—failure to meet what’s demanded of him. Yeah, he doesn’t manage to get it right.

I guess we were saying two different things about what the eggs come out of. One is conflict—from which you get bravery. The other thing about the eggs is the element of fantasy. Does it constitute bravery to accept that there’s a delusive aspect to our most meaningful relationships? I feel like avoiding conflict would be him saying, “Right, I know the eggs come from the crazy, but I’m not going to try to excavate where my brother’s belief that he’s a chicken is coming from. I’m not going to try to shake him into reason, I’m just going to let him have his thing, because I’m getting these eggs.” That’s not necessarily a working-through of something.

GOLDMAN

Right, the picture you just described feels placid, not generative. And it cuts off the possibility that both participants might have an awareness of the delusion of the enterprise, yet still be interested in investigating it together.

KHAWAJA

I mean, speaking of the difficulty and deludedness of the enterprise, there’s also the “art and the artist” problem. Can you accept or appreciate one and not the other?

GOLDMAN

Right, like, if we need the eggs—the artwork, or whatever—do we have to take the chicken, too?

KHAWAJA

On the one hand it seems like we are saying yes, or that the joke is saying yes. I think what the very idea of art means is that there is a difference between the two. Somewhere. Not a brick wall, but… I think, yes, you’re in a relationship with both the art and the artist, but they don’t have to be the same kind of relationship.

GOLDMAN

So where is that line?

KHAWAJA

I don’t know in the abstract, and even if I did, I doubt the five of us would agree on where it is. I just think that orienting something as a work of art means that a line between chicken and egg exists, or can be drawn.

SHEILA HETI

A line between the chicken and the egg, or between the two relationships, or between the art and the artist?

KHAWAJA

Let’s say I’m glad Woody Allen made Annie Hall, and glad Woody Allen is not my brother.

SHEILA HETI

For the record, my father really wanted to name me Woody Allen. But my mother said she’d run away with the baby. (Laughter.)

GOLDMAN

If this is a joke about the necessary delusions that sustain a relationship, does it also speak to the delusions that sustain life in general? As in, if modernity and postmodernity are epochs in which everything has become disenchanted and historicized and revealed to be socially manufactured—even the very notion of romantic love—we have two options. We can bracket that and live our lives not thinking about it, or we can say, Yes, it’s all constructed, but that doesn’t make it any less real.

ATKINS

If we read this as being about modernity and our relationship to inherited myths—if that’s another possibility for the joke, that we’ve been handed all these traditions, and we kind of need them for the eggs, even though we can no longer believe in them sincerely, like people did two thousand years ago—to what extent are we deluded in thinking that we have a choice, if in fact we are operating from a powerful unconscious drive? If you hear from someone who’s complaining about a relationship they’re in, but they’re not breaking it off, and you’re like, “Get out of there,” and they’re like, “Well, I need the eggs,” I mean, you’d probably be concerned, right?

But you might also say, “You know what? If that’s their choice—clearly it’s doing something for them. I shouldn’t just be listening to what they’re saying consciously. I should be observing their unconscious, and their unconscious is saying, ‘Yeah, I love it.’” Similarly, the rational project is all about debunking religion, or debunking myth, and meanwhile, so much of what we do continues to be mythical or irrational. I think the lesson might be that we can’t reason our way out of delusion. Delusion is so much bigger than what we can say about it.

SHEILA HETI

What you’re saying is making me think that part of what’s interesting and funny about the joke is that he’s giving a conscious voice to his unconscious understanding of, “Well, I need the eggs.” It’s weird to hear someone be able to speak aloud their unconscious.

GOLDMAN

That feels right to me, and it also makes me wonder about the meaning of the form of the joke. Walter Benjamin talks about Kafka in relation to two components of the Talmud—Aggadah, or narrative, and Halacha, or the law. Benjamin says that traditionally, Halacha is subservient to Aggadah, but that Kafka’s genius is that he sacrifices the truth of tradition for the sake of its transmissibility—so, his writings are parables that abandon or negate the very truth the form is designed to illustrate. It’s almost like Kafka empties the Jewish parable of its content but maintains the form. We could think about this joke as performing something similar—doing what Zohar’s talking about, negating the mystification while also replicating it. Maybe this is where the absurd texture of modernity—and the joke—comes from. Not from saying, “This is irrational, and therefore we have transcended it,” but by being able to puncture or negate the irrational and still not transcend it.

ATKINS

I think what Nathan just said about the emptying out of the content but the preservation of the form is such a great description of what Woody Allen does in general, and of his use of intellectualism as a kind of superficial fashion. The characters will be reading McLuhan or Tolstoy or whatever, and you get this feeling of being so intelligent by participating in it—or at least I did as a teenager—and meanwhile the characters are completely idiotic. But that’s as old as philosophy itself. The philosopher always has to hold herself in suspicion of being a sophist. And maybe that’s the ambivalence—Do we get wiser from art? Or is art just another prop by which we justify ourselves in our psychopathy? I don’t mean that to sound cynical, because I need the eggs, obviously. That’s why I’m here.

DAVID HETI

Yeah. I mean, I do think you can take a joke and break it down into its formal logic. You can say, Here is the proposition, and here is where the contradiction lies. But also, for it to be a good joke, it can’t just be a formal mechanism. That’s how the performance of it matters—in its relation to greater social values, and even in terms of what we understand that one gets out of a relationship. Certain relationships can be purely monetary. A relationship in the old world might have existed only so that both families could survive. You would bring together a farm and get—whatever, a goat or something, whereas now relationships are supposed to provide you with your entire world. So, with the eggs—maybe it’s not even a joke, maybe it’s in fact some ancient story, where the eggs were literally eggs. He needs the eggs!

KHAWAJA

Oh, I love that!

(Laughter.)

SHEILA HETI

It wasn’t even a joke originally! Two hundred years ago there were no metaphorical eggs in a relationship!

ATKINS

Wow! Wait, so maybe the brother really is crazy, but he also does offer eggs!

KHAWAJA

That’s great!

ATKINS

Can I just give you two other associations that came to mind about the eggs? One is that in Jewish law, an egg is a Halachic measurement—it’s a stand-in for a threshold amount by which something becomes substantial. There are actually two different measurements—something is the size of an olive, or something is the size of an egg. Certain things become things at the size of an olive, and others only become a thing, legally speaking, at the size of an egg. There is something iconic about an egg in Jewish law. So if the egg is the minimal amount by which something becomes real, it’s a kind of border, an image of a borderline; yes, it’s a delusion, but it’s a delusion with enough gravitas to become real, to substantiate itself.

SHEILA HETI

That makes me think that a romantic relationship doesn’t become real until it becomes completely absurd to participate in it.

ATKINS

Oh, amazing. And there’s another association. In the Zohar, the book after which I’m named, there’s a short passage on one of the biblical laws, which says to “shoo away the mother bird before taking her eggs,” because it’s considered cruel for the mother bird to be present when you’re taking her eggs away. It’s one of the only commandments in the Torah where reward is given for observing that law, and the reward is that your days will be lengthened. In the Zohar, they interpret it allegorically. The bird is God and the eggs are the manifestations of God, so to shoo away the mother bird and then take her eggs is to say that we cannot know the origin of things, and that we shouldn’t try. But we can know the children, or we can know the offspring, in some form, and we’re allowed that. It’s not just that we’re allowed the eggs, but that inasmuch as we’re obliged to shoo away the mother, we’re obliged to take the eggs. The way I read it is that the eggs represent science or the pursuit of knowledge. The mother bird represents mysticism, and this mystical text is saying, Don’t try to be a mystic, because you’ll fail. But if you admit to the humility of your endeavor, then the eggs here are fine to take. There is a connection—between bird and egg, or between metaphysics and the known life of dailiness—but don’t interrogate it too much. So I think, actually, the mystical, acid-trip take, is, Oh, and the brother actually is a chicken. But it’s not for us to live on that plane, so don’t go there. Just take the eggs. You’re never going to figure it out.

Zohar Atkins is a rabbi, poet, scholar, and podcaster.

Nathan Goldman is the managing editor of Jewish Currents.

David Heti is a stand-up comic of two comedy albums, It was ok and And you will regret it.

Sheila Heti is a novelist and the former interviews editor of The Believer.

Noreen Khawaja is the author of The Religion of Existence and teaches in the Religious Studies department at Yale University.

April 19, 2022

Redux: All the Green Things Writhing

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

PHOTO COURTESY OF ANTONELLA ANEDDA ANGIOY.

“Spring like a gun to the head,” Dorothea Lasky writes in a poem in our latest issue, “Green how I want you.” It’s been a strange, uncertain season, and now that the weather is turning and the cherry trees are beginning to blossom, we’re revisiting some works that evoke the cruelest month: an interview with the Italian poet Antonella Anedda; a story by Ira Sadoff that makes romancing a florist sound wistful yet thrilling; Elizabeth Brewster Thomas’s poem in which “beneath your feet a thousand spores of ice / blossom in darkness”; and a collaboration between Ben Lerner and the photographer Thomas Demand, featuring a profusion of paper flowers. (And if you pick up a copy of our Spring issue, you’ll also find collages by the late artist Birdie Lusch, who pasted newspaper clippings onto Hallmark catalogues to make her glorious bouquets.)

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and art portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

INTERVIEW

The Art of Poetry No. 109

Antonella Anedda

ANEDDA

The first poem I ever heard was by Aleksandr Blok, on the radio in a small village in Sardinia. It’s an early work that begins, “Carried on the breeze, / the Spring’s music drifted from far, far away.” The poem was about space and wind—how the wind breaks open the clouds to reveal a strip of blue sky.

INTERVIEWER

What was it that moved you?

ANEDDA

When I was seven, a member of my family, a person I loved, died in front of me. Suddenly her body was a thing without a voice. Listening to Blok’s poem—I was thirteen or fourteen—I thought that perhaps poetry could create a relationship with absence, with death, transposing the present into another space and time.

From issue no. 234 (Fall 2019)

PROSE

Seven Romances

Ira Sadoff

I could not help myself, I fell in love with the florist. Each day he handed me arrangements of flowers: lilies-of-the-valley, chrysanthemums and roses, exotic willows and violets. As a lover he was strange and melancholy: he had an intense hatred for the out-of-doors and almost never left the house; the mention of sports made him dizzy and a car moving too fast would bring him close to tears. … When he threatened to leave I became the carnation in his lapel, I was his brooch. When the weather became warm and clear, somehow it was he who wrapped me in a blanket, dragged me outside to a park; and when we made love I was the one who wilted, I felt my color brush off on his chin.

From issue no. 68 (Winter 1976)

POETRY

Consolation: After Rilke

Elizabeth Brewster Thomas

Spring again. Wet April calls the blue

from the sky, would give me names

for all the green things writhing from the earth’s

numb body. But I’ve been too long

a student of the winter, have memorized the lines

of trees whipped bare by wind—I’ve learned to love

the gray in your hair.

From issue no. 173 (Spring 2005)

ART

Sample Trees

Ben Lerner & Thomas Demand

Blossoming en masse, in time lapse

You refer to a place where water flows

Over a vertical drop in culture / Poems

Fail to mention fission or decay

In the traditional ways, focusing instead

Then renouncing focus, a shimmering effect

From issue no. 212 (Spring 2015)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-nine years’ worth of archives.

April 15, 2022

On Thomas Bernhard and Girls Online

From Kati Kelli’s “My tragic homeschooled past.”

You’re on that old kick again, rereading Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage to refresh and resplendorize the senses, but why not go back to the source? It’s never wrong to read Dyer’s Thomas Bernhard (and, after all, your Bernhard). It’s never bad to sit at Good Karma Café, in Philadelphia, at a little metal table out front, with Bernhard’s novella Walking, reading

I ask myself, says Oehler, how can so much helplessness and so much misfortune and so much misery be possible? That nature can create so much misfortune and so much palpable horror. That nature can be so ruthless toward its most helpless and pitiable creatures. This limitless capacity for suffering, says Oehler. This limitless capricious will to procreate and then to survive misfortune.

while a person pulls up with a carriage and introduces to the air a baby, a little baby who was born three days ago, and stands there holding this: “Lily.” She explains as much—the three-day thing—and announces the name to inquirers (the nonreaders …). Three days old only! Why is this little baby taking the air so soon? Why promenade now? This merciless tenderness might permeate the whole atmosphere now, while you read “My whole life long, I have refused to make a child, said Karrer, Oehler says, to add a new human being over and above the person that I am, I who am sitting in the most horrible imaginable prison and whom science ruthlessly labels as human,” and laugh at combinations, at the café.

—Caren Beilin

You can read Sheila Heti’s interview with Caren Beilin on the Daily here.

A woman is a woman, to borrow from Godard, but once she’s online, argues Joanna Walsh in her new book-length essay, Girl Online: A User Manual, she becomes a girl. In a series of meditations and “thought experiments” exploring motherhood, blogs, women’s writing, and the meaning of work both on and off the screen, Walsh examines the relationship between looking and being looked at, watching and being watched, that is inherent to both the internet and femininity. “What’s a girl to do with communication technology?” she asks. “I mean both, ‘Why is a girl like a screen?’ and ‘What is she doing in front of it / on it?’ ” The answer is clear, Walsh explains, in a passage that draws from Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media: “Selling herself, of course.”

—Rhian Sasseen, engagement editor

Kati Kelli was a girl online who was just being herself—herself, in this case, being many, many different girls. The videos on her Youtube channel, Kati Kelli Girl, include sequences, somewhere between sketch comedy and video art, in which she dances “drunkenly” in a pink velour tracksuit and “Beverly Hills mom” wig, dances “interpretively” in a skeleton mask, plays with Barbies, and reads “DEEP poetry.” The rest are largely parodies of the now canonical forms of the girl-bedroom vlog genre: “I Have Daddy Issues,” “10 things about Kati Kelli,” “My Weight Loss Secret.” But describing her work as merely satirical doesn’t do it justice; Kelli’s experimentally edited monologues and musical numbers are also intimate, surreal, and, like all great comedy, somehow true. I encountered Kelli via Girl Internet Show, a feature-length “mixtape” of her work curated by Jane Schoenbrun and Jordan Wippell that screened Sunday at BAM. That same day, I had visited the Jewish Museum’s Jonas Mekas show. Whereas the world captured by Mekas’s “always running” camera—flowers, birthday cakes, babies, couples in the park—sometimes verges on a (beautiful) trope of “everyday life,” Kelli’s hyperperformances feel, always, intrusively, perversely real. “If I wasn’t real, could I do this?” she asks, in one video. “I just blinked,” she explains after a second. But we can’t see; she’s wearing huge, reflective sunglasses.

Schoenbrun and Wippell’s film, lovingly produced after the artist’s untimely passing in 2019, features both Kelli’s Youtube hits and several never-uploaded home movies. “I’m twenty-two, and I’ve done nothing with my life … except be ugly,” she whispers, in one of these few (seemingly) unscripted clips. Then she bats her heavily made-up eyelashes, trying out angles. Kelli always has the unmistakable look of a girl on camera who knows she’s very hot—which, of course, almost always involves fearing the opposite. The internal contradictions and multiple personalities that make up a person are explicit themes in her work, which one could characterize as the artistic output of an isolated young girl experimenting with costumes to explore her “identity.”

But the most beautiful moments of Kelli’s videos are those in which these experiments feel least intentional, when we’re watching someone alone in her bedroom behaving randomly, without a script or audience—when she doesn’t seem to be playing at being anyone at all. Sometimes, she’ll pause and look blankly at the camera, as though her teleprompter has frozen. She seems to be waiting for words to come—and when they do, it’s like she’s lip-reading her own on-screen reflection. “I just have a kind of, um, natural chemistry with the camera,” she says. “So yeah, like, if you’re wondering, like, Why am I so drawn to her but why, like—why isn’t she good—it’s because my talent is so raw that I haven’t figured out how to you know … whatever.” It’s a huge loss that Kelli didn’t have time to figure it out. Her videos are still up, though, here.

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

April 12, 2022

Cooking with Sergei Dovlatov

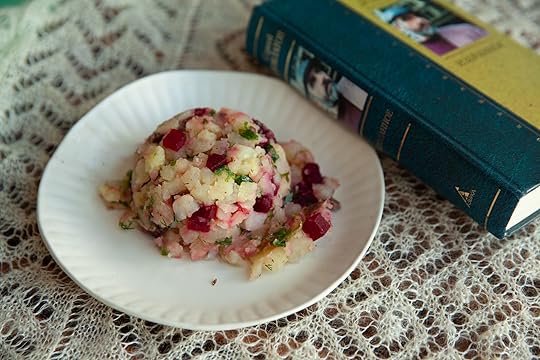

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

“Dad did not care about food,” the daughter of the Soviet dissident writer Sergei Dovlatov once told me, vehemently, upon my suggestion that I might cook from her father’s work. I knew what she meant, but I also knew that Dovlatov’s books were full of the everyday food that was still current in Moscow when I first arrived there to live in the nineties, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Dovlatov’s characters pause during phone conversations to scream that someone not forget to buy the instant coffee (the only coffee available—I grew to like it). They drink—continuously—wine, vodka, beer. They offer each other bowls of borscht or “spear a slippery marinated mushroom” while talking, or order a sandwich, a salad, or a “chopped-meat cutlet” at a café. In one memorable scene near the end of The Compromise, an autobiographical novel about Dovlatov’s time working as a correspondent for the newspaper Soviet Estonia in the seventies, a full spread of delicacies for Communist Party elite comes out: expensive cold cuts, caviar, tuna, and a piped marshmallow dessert called zefir.

Open-faced sandwiches called buterbrod (from the German) were popular in immediately post-Soviet Russia. At the Bolshoi Theater they served them with orange caviar. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Like everyone I know who has personal ties to the region, I watched with profound sadness and stress as Russia invaded Ukraine. I thought again of Dovlatov. Within Russia, he is among the most prestigious of the Soviet anti-regime writers, and is a household name. Born in 1941 to Armenian and Jewish parents, he grew up in Leningrad and worked primarily as a journalist. By the seventies, he was publishing fiction abroad, and circulating it by hand in photocopied format, as samizdat, in the USSR. This work drew government reprisals that left him unemployable, and he was forced to emigrate in 1979. His stories featured a depressed and often drunk narrator named Dovlatov and focused on the despair, hypocrisy, and absurdity of life—particularly life in the publishing industry and the arts—under a totalitarian government. I was working as a journalist during my time in Moscow, and everyone I met told me that I had to read him, specifically recommending The Compromise. Each chapter begins with a fulsome snippet of a fictional newspaper article written in the propagandistic style of Soviet newspapers, and is followed by the tragicomic story that unravels the propaganda. At the time, it was thrilling to believe that the forces of censorship had been defeated, and that Dovlatov and those like him had won.

A character in The Compromise eats marinated mushrooms while another passes out into a dish of potatoes during a drunken bender, the real story behind a fake story on a reunion of prisoners of war. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Now, of course, those forces are ascendant once again. In the nineties, I identified with Dovlatov’s experiences working for Soviet Estonia; I was freelancing for women’s magazines and early websites, and my editors often wanted to massage the facts to fit the preferred headline or had loathsome criterion such as “Everyone in this piece has to be attractive.” I could relate to Dovlatov’s pain as he was forced to write about ideologically correct babies or to cover a funeral where the bumbling authorities bury the wrong corpse. “Dovlatov can write in a lively way about any kind of nonsense,” an editor says of him, as a compliment (translation mine). I knew just what that felt like. Today, I am nostalgic for such lighthearted concerns.

Dovlatov included culinary details because of the realist bent of his work. The potato salad I made from these ingredients was unrealistically good for food of the time. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

To combat propaganda and censorship, Dovlatov offers truth and craft. His fiction is written in clear, meticulous language; he lets events speak for themselves. The pitch-perfect deadpan humor is almost untranslatable, but many lines resonate with me. My favorite statement ever made about a day at the office is this one: “I continued to work without any special ardor.” I also laugh when an editor sending him on assignment asks, “Comrade Dovlatov, do you have a black suit?” Dovlatov replies, “I have a sweater.” Their truth is in these daily details—the protagonist is broke, drunk, depressed, semihomeless, doesn’t own a suit, is unable to get his fiction published, and is wasting his talents churning out foul propaganda. The gorgeous craftsmanship of the rendering is the commentary, revealing the Russian value of dukhovnost, a slippery word that I’d translate as the combination of culture, morality, and spirituality.

Flavoring elements included tons of oil, chopped dill and tarragon, black olives, and beets. (Tip: Mix in the beets just before service to preserve the color of the dish.) Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Dovlatov believed that dukhovnost was in direct opposition to “excitement about food,” his daughter says. For him, there were more important concerns than what a person was eating for dinner, and to imbue food with any serious significance would have been both laughable and low. (Writing fifty years ago in the Soviet Union, he would have had no inkling of the way our food today has become an ethical quandary.) The feast at the end of The Compromise, which included “the standard assortment of Central Committee allocations,” provided an opportunity for social satire. It occurs when Dovlatov and a photographer-sidekick Zhbankov are sent to a regional town to interview a super-productive dairymaid. Her achievement will be celebrated in a telegram to Brezhnev. Upon arrival, Dovlatov and Zhbankov are whisked off to a house of rest and greeted by two young women with party affiliations, there to have sex with the visiting bigwigs. Like the chocolate-covered marshmallow (zefir), such things were perks for communist authorities. When he sees the unaccustomed spread of food, Zhbankov says, “Serge, what have we got ourselves into?” Dovlatov replies, with withering irony, “What’s wrong? We’re simply moving up.” And then, “We’ve been given a serious assignment.” (The assignment, don’t forget, is a made-up story about milking a cow.)

“Everyone who thinks is unhappy,” Dovlatov writes. For the thoughtless, there were feasts like this one. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Dovlatov partakes of the feast without comment: to take from the system that was taking from you was considered only fair. He sleeps with the girl, too, though it is a rueful experience. “It’s amazing how men are put together!” he observes, “Or am I the only one like this? You know it’s all lying, primitive Party sham and lying with a Hollywood patina over it. You know it all but you’re happy as a kid.” His aim is to truthfully portray humanity—and to make culture from even the lowest experience. This recalls for me the book’s prologue, in which he says of his work as a reporter: “Ten years of lies and dissembling. And yet, some people stood behind them: conversations, feelings, things that actually happened. Not on the pages themselves, but beyond them.” It’s the truth and the quality of the rendering that’s important, and that serves as a counterweight to the world of garbage and spin. In this sense, The Compromise is uncompromising.

The trick to cutlets “Kyiv-style” is to add riced potatoes as a thickener. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

I set out to try to reassemble the food in Dovlatov, doing my best on the quality of the rendering—cooking is an art form that Dovlatov may not have appreciated, but it’s my own. When I first encountered the type of Russian salads and cutlets and sandwiches he writes about, my suburban American sensibility found them both wondrous and awful. A Russian “salad” had no green leaves. A “cutlet” was a soft, oval ball of ground meat, scooped by the hostess from a bath of murky liquid. A “sandwich” was not a sandwich but a buterbrod, a heavily buttered slice of bread, topped by a curling bit of cheese or glistening balls of congealing orange caviar. In cafés, they were often left sitting out unrefrigerated. (Americans, I learned, are uptight about refrigeration.) Zefir tasted good—dessert is a universal language—but the marshmallow had a mysterious sour note. Later, living again in Moscow in the early aughts, I grew to appreciate these foods, especially in their home-cooked versions.

I made marinated mushrooms, buterbrod, a potato and beet salad, and, from a Ukrainian cookbook, cutlets “Kyiv-style.” I also attempted to make zefir at home, a process difficult to get right without a candy thermometer. I knew enough about Russian cuisine to predict—correctly—that the results would be mixed. Russian pickles and marinades, like Russian jams, are an arcane art. Each woman in the countryside does it in her own way, often from foraged or homegrown ingredients. My mushrooms were edible, but not authentic-tasting, nothing like the pickled mushrooms my Russian mother-in-law makes, with their additional notes of dill flower and blackcurrant leaf. The buterbrod, also, couldn’t be accomplished without commercially produced white bread and yellow cheese not available in the United States. They looked correct, but the single perfect flavor note, the salmon roe, emphasized that the rest wasn’t quite right.

The pointed-oval shape of my cutlets looked just right. Photograph by Erica MacLean.

The potato salad and the cutlets were inauthentic in a more successful way. Dovlatov ate his in a café in the seventies in Estonia. They probably weren’t very good. Mine were wonderful. The cutlet recipe called for riced potatoes as the thickener for the meat mixture, which was then shaped into ovals, rolled in flour, fried, and braised in stock. I made adjustments, leaving out the onions and changing the ratio of beef to pork, but this time it was a variation any grandmother might try based on her preference or ingredients at hand. I also tweaked the potato salad, adding much higher amounts of the flavoring elements. I don’t think I’ve ever had a better one, and my own Zhbankov, photographer Erica MacLean, agreed.

The zefir was a Central Committee allocation in The Compromise, not a dish an ordinary person would make at home. I discovered that the sour taste of the marshmallow that befuddled me as a young woman was a green apple puree, whipped with an egg white and sugar to make marshmallow. (Green apple and chocolate? Go figure.) I did my best with a complicated multistep process that included tempering chocolate, sieving apple mash, and cooking a meringue base with hot syrup. The marshmallows didn’t quite set right, but I was pleased by how correct the finished zefir, and everything else, looked. If some of those items were all looks and no truth—well, they were inspired by a book about propaganda.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Marinated Mushrooms

1 pound mushrooms, any style, cleaned and trimmed

1 teaspoon salt for blanching the mushrooms

1 cup white vinegar

¾ cup water

2 cloves

2 bay leaves

3 black peppercorns

2 whole allspice

1 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon salt

1 clove garlic

Bring a large pot of water to boil, and add mushrooms and salt. Simmer for two minutes. Drain.

In a small saucepan, combine vinegar, water, cloves, bay leaves, peppercorns, allspice, sugar, and salt. Bring to a boil and turn off heat. Let cool.

Pour the marinade over the mushrooms. Cover tightly and refrigerate. Ready in three days.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Buterbrod

White bread, 1 loaf

Butter

Yellow cheese

Salmon Caviar

Slice the bread, slather it thickly with butter, top with cheese or caviar, and set out in a warm place to await the guests. Voila!

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Potato Salad

2 large white potatoes

1 small beet

2 scallions, chopped

¼ cup black olives, chopped

2 tablespoons dill, finely minced

2 teaspoons tarragon, finely minced

¼ cup olive oil

½ teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

Black pepper to taste

1 teaspoon white vinegar, plus more to taste

Bring two medium saucepans of water to a boil. Boil potatoes and beet, separately, until cooked through. Cool and peel.

Dice both potatoes and beet into quarter-inch cubes. Reserve beet. Place potatoes in a medium bowl, add all the rest of the ingredients, and taste to adjust seasoning. (I used a full extra teaspoon of white vinegar.) Mix in diced beet just before serving.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Kyiv-style Cutlets

1 pound ground beef

½ pound ground pork

½ cup milk

1 egg

1 tablespoon bread crumbs

1 tablespoon melted butter

1 teaspoon salt

Ground pepper to taste

1 cup riced potatoes (potato boiled and put through a ricer or food mill)

½ cup flour

Vegetable oil

2 cups chicken stock (Better Than Bouillon)

2 bay leaves

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Place ground beef, ground pork, milk, egg, bread crumbs, melted butter, salt, pepper, and mashed potatoes in a large bowl and mix with your hands until well combined.

Place the half cup of flour on a plate, salt generously, and mix to distribute the salt. Set a bowl of water by your workspace. Shape the meat into oval-shaped cutlets, about the size of the palm of your hand, dipping your hands in water from time to time so the mixture doesn’t stick. Once the cutlets are shaped, roll each one in flour until lightly dusted.

Heat a generous amount of oil in a large skillet, add the cutlets, and fry until browned on all sides. Pour in the two cups of chicken stock, add the bay leaves, and bring to a boil. Cover and simmer for fifteen minutes.

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Zefir

Adapted from

the blog

Sweet and Savory by Shinee

. You will need a piping bag and large piping tips for cake decoration; Wilton 1M is recommended.

Puree:

7 ounces granny smith apples, peeled cubed

1 tablespoon sugar

Photograph by Erica MacLean.

Marshmallow:

1 egg white

¼ teaspoon salt

1½ cups sugar, divided

½ cup water

3 teaspoons agar agar powder

Chocolate dip:

1 11.5 ounce bag of Ghirardelli semisweet chocolate chips

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

Cook apples with one tablespoon sugar over medium-high heat for fifteen minutes, mashing as you go. You want the resulting paste to be fairly low in moisture content. Run the mixture through a sieve (you should have about two hundred and fifty grams of it), then cool and chill completely in the refrigerator.