The Paris Review's Blog, page 83

May 5, 2022

Chestnut Trees

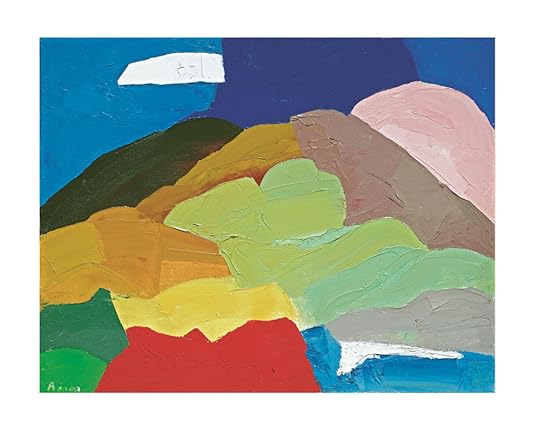

Artwork by Hermann Hesse. Photograph by Martin Hesse Erben. Courtesy of Volker Michels.

Everywhere we’ve lived takes on a certain shape in our memory only some time after we leave it. Then it becomes a picture that will remain unchanged. As long as we’re there, with the whole place before our eyes, we see the accidental and the essential emphasized almost equally; only later are secondary matters snuffed out, our memory preserving only what’s worth preserving. If that weren’t true, how could we look back over even a year of our life without vertigo and terror!

Many things make up the picture a place leaves behind for us—waters, rocks, roofs, squares—but for me, it is most of all trees. They are not only beautiful and lovable in their own right, representing the innocence of nature and a contrast to people, who express themselves in buildings and other structures—they are also revealing: we can learn much from them about the age and type of arable land there, the climate, the weather, and the minds of the people. I don’t know how the village where I now live will present itself to my mind’s eye later, but I cannot imagine that it will be without poplars, any more than I can picture Lake Garda without olive trees or Tuscany without cypresses. Other places are unthinkable to me without their lindens, or their nut trees, and two or three are recognizable and remarkable by virtue of having no trees there at all.

Yet a city or landscape with no predominating woods of any kind never entirely becomes a picture in my mind; it always remains somewhat without character, to my feeling. There is one such city I know well—I lived there as a boy for two years—and despite all my memories of the place, my image of it is of somewhere foreign and alien; it has turned into a place as arbitrary and meaningless to me as a train station.

It’s been a very long time since I’ve seen a real chestnut-tree city—this thought occurs to me whenever I see a single beautiful horse-chestnut tree around here or sadly catch sight of the shabby little horticultural chestnut trees in certain villages. If they only knew how chestnut trees could look! How mightily they can stand there, how luxuriantly they blossom, how deeply they rustle, how luscious and complete the shadows they cast, how they swell with monstrous fullness in the summer and lay down their golden-brown leaves in such thick, soft piles in the fall!

Today I am once again thinking of the city with the beautiful chestnut trees: a town in southwest Germany. In the center is the old castle, a massive sprawling boxy structure, with the whole sprawling building ringed by an amazingly wide moat, long since turned into a dry ditch, and surrounding the ditch in a wider circle is a splendid avenue. On one side of the avenue is nothing but old low houses and little gardens, and on the other, open side, facing the castle, is a mighty garland of large chestnut trees.

On one side hang signs for shops and inns, the joiners hammer away, metalworkers smash menacingly at their sheet metal, cobblers lurk in the twilight of their cavelike workshops, tanneries give off their mysterious stink. On the other side of the wide avenue there is silence and shade, the smell of leaves and the green play of light, the song of honeybees and the flight of butterflies. So the poor devils beating carpets and doing handicrafts have their windows facing an eternal holiday, the never-ending peace of God, and they squint longingly at it all the time, and on warm summer evenings they cannot go out to visit it early enough, or with enough sighs.

I stayed in that little city once, for a week, and although I was actually there on business, I liked to look patronizingly in through the merchants, and craftsmen’s windows and put on a show of strolling—slowly, aristocratically, and often—on the shady, leisurely side of the street and of life. The best thing, though, was that I was staying by the moat, at the Blond Eagle, and had the many blossoming chestnut trees, red and white, outside my window in the evening and through the night. Now, enjoying this visual pleasure was not entirely without a cost, since the seemingly dry moat still had a damp enough moss-green bottom to send up a hundred thousand hungry mosquitoes a day. But a young person traveling doesn’t sleep much on such summer nights anyway, and when the mosquitoes got too rude I rubbed some vinegar on myself and sat by the window with a cigar lit and the light off.

What singular evenings and nights! The smell of summer, a little warm street dust, the buzz of mosquitoes, and mugginess filling the air with its electricity, secretly twitching and thrashing.

After all these years, those warm nights along the chestnut alley now come back to me and seem precious and poignant, like an island in my life, a fairy tale, a lost youth. They look at me with a gaze so deep and holy; their whisper is so beguilingly sweet and hot; they make me so sad, like the legend of paradise or the lost song that dreams of Avalon.

I would usually be finished with my “business” by the afternoon. As soon as that moment came, I would stroll the whole circle around the castle once or twice with the gentlemanly hauteur of the idle do-nothing, enjoying the freedom and laziness I felt such a talent for in those days. Oh, if I’m ever going to accomplish anything in life (but is that really as very necessary as everyone’s always telling me?)—if I am, I will have to work so hard, so bitterly, that surely I can now enjoy the gift of these few free day …

Then I would saunter off through the city and the park outside town, and up some hill to a high, fragrant summer meadow or dim, secret corner of the woods. The squirrels racing like lightning, the tumbling butterflies—I hadn’t looked at them with so much idle abandonment since I was a boy. I would swim in a brook, or at least splash water on my warm head. Then, in some hidden spot, I would take out a little notebook of graph paper and write in it with my sharpest pencil things I was ashamed of, but which nonetheless made me unbelievably happy, even proud. Presumably my poetry from then was worthless, and I’d probably laugh if I saw any of it again today … No, I wouldn’t laugh. Definitely not. But I wish I could ever be as crazily silly, giddy, and deeply happy again when I was writing or, indeed, doing anything.

And so evening would come, and I’d walk back into town. I would pick a rose in the park and carry it in my hand, for how easily it might happen that I would find myself in a situation where one wants to have a rose in one’s hand. For instance, if I ran into Kiderlen the carpenter’s daughter on the market corner at a propitious moment, and I doffed my hat, and maybe she didn’t just nod but let a conversation spring up, would I have any qualms about offering her that rose with some suitable words? Or maybe it might be Martha, the niece and waitress at the Eagle—it was because of her that they had renamed the Black Eagle Inn as the Blond. She always looked down on me so. But maybe she wasn’t really like that.

Lost in such thoughts, I would enter the city and walk back and forth through the few little streets, inviting Chance to show its face, before returning to the Eagle. As I walked up to the door of the inn I would stick my rose in my buttonhole and then enter, and politely order ham with mustard or a ham hock or ribs with cabbage and a Vaihinger beer to go with it.

I would page back through my little book of verses until the food came, quickly putting a line in the margin or a question mark or crossing something out here and there, and then I would eat and drink and take the older, more elegant gentlemen among the regulars as my model for proper conversation and conduct. It sometimes happened that the innkeeper, husband or wife, would do more than wish me bon appétit, they would sit down across from me for a bit and start a conversation. I would answer their questions, affable but modest, and I could occasionally manage to offer a pithy saying, a political opinion, a joke.

Finally I would pay for my dinner, take a bottle of lager with me, and go upstairs to my room. The mosquitoes would be whirring busily. I would have to stick my beer in the washbasin’s water to keep it cool.

Then came those strange evening hours. I sat on the windowsill, alone, and half-consciously felt how beautiful the summer night was, and the slight mugginess, and the ghostly pale beacons of the chestnut’s white blossoms, like large candles. Then, anxious and melancholy, I would see the couples walking in the dark under the great trees, slowly, pressed up against each other, and I would sadly take my rose from its buttonhole and throw it out the window onto the slightly dusty, shimmering white road for carriages and guests from the inn and lovers to trample.

Have I promised to tell you a story here? No, I promised nothing of the sort, nor do I want to tell any stories. You can tell a story about getting engaged or breaking your leg. I want only to hear the song of those summer nights once more—it is dearer to me than all the songs of Avalon put together. I want only to call back to mind the old city, and the castle, and the moat, so I don’t forget them forever. I want only to think about those chestnut trees for a little while, after all these years, and about my little poetry notebook, and all of that, because it will never return.

But it does seem unbelievable that I only spent seven days and nights there. It feels like I took at least a hundred walks up to the woods, broke off at least a hundred roses, planned to give at least a hundred roses on a hundred evenings to the pretty girls in the chestnut-tree city and then gloomily threw them out onto the darkening street later, when no one wanted them. Of course I’d stolen those roses, but who would have known that? Not Kiderlen the carpenter’s daughter, not blond Martha, and if one of them had wanted that stolen rose from me, I would have gladly bought a hundred more to give her.

This essay, originally written in 1904, is an excerpt from Trees: An Anthology of Writings and Paintings by Hermann Hesse, edited by Volker Michels, and translated by Damion Searls. The anthology will be published by Kales Press in May.

May 4, 2022

Notes on Nevada: Trans Literature and the Early Internet

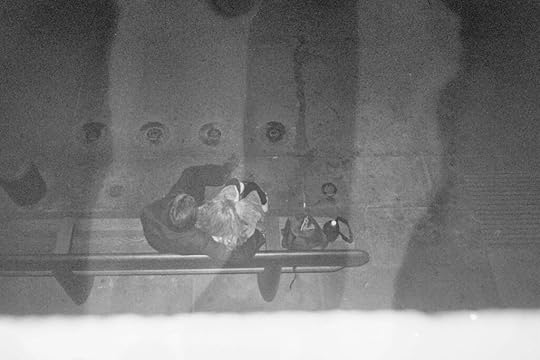

Imogen Binnie at Camp Trans in 2008. Photo courtesy of the author.

Almost ten years ago, I published a novel called Nevada with a small press called Topside that doesn’t exist anymore. You may or may not have heard of it, but if there are trans people in your life who are readers, they probably have. It became a subcultural Thing. It’s been out of print for a few years, but in June, Farrar, Straus and Giroux will bring it back into print.

People have called Nevada “ground zero for modern trans literature,” and while I get that—before it was published, I don’t think I’d read a novel with a trans character who I didn’t at least sort of hate—I don’t really feel like a genius visionary who invented literature centering marginalized experiences. At the very least, this idea occludes the work other people had done that made Nevada possible. So instead of celebrating myself, I want to use this opportunity to say thanks, and to think through some of the influences and experiences that shaped the novel.

FICTIONMANIA

At one point in Nevada, Maria mentions the “stupid 2002 internet.” At a Q&A following a reading on the 2013 book release tour, I was asked what that meant. I struggled to come up with a decent answer. We are so steeped in for-profit social media today that it’s hard to remember anything else. It wasn’t until the night after that reading, lying awake and beating myself up for not having a good answer, that I thought of a pretty good one. It is a website called Fictionmania. It’s still online. And if you’re hungry for that post-post-vaporwave retro “2002 internet” aesthetic, great news: it hasn’t updated its design since it came online in 1998.

Fictionmania is a free archive of user-contributed stories on the theme of gender change. If you were trying to figure out what was going on with your gender in the late nineties and early aughts, you tended to end up there. Its stories, on the whole, are not politically or stylistically progressive, but it’s accumulated, like, forty thousand stories over the last twenty-five years, so it’s definitely doing something that’s compelling for a lot of people. I mean, how many websites have been around since the late nineties?

Fictionmania is the first place I was published, unless you count a short story in a high school lit mag that was about 40 percent unattributed Tori Amos lyrics. You’d just send FM a story you’d furtively made up instead of sleeping, and then they would publish it—publicly, on the internet!—and then strangers would tell you that they hated it. In the late nineties, for an English major who Wanted to Be a Writer, that was a serious thrill.

As a praxisless but punk-identifying teen with good intentions, no analysis, and no idea how to exist in a body, anonymously contributing stories with cuss words in them to FM was an empowering way to say, “I have no idea what’s going on with me or my gender, but I do not care for it.” I lost interest pretty quickly and moved on to my own zines and in-person writing groups, but because those things involved identifying information, I put away the What Is Gender stuff for a few years.

CAMP TRANS

As I processed the fact that I was trans, mostly on LiveJournal, I started connecting with a like-minded community of trans people who also were unhappy with the options for living we saw available as trans people. Brynn Kelly was one. Sybil Lamb was there. A lot of other people. And the smartest, funniest, and most intimidating people on LiveJournal were usually also on the strap-on.org message board.

Strap-on was terrifying.

When you’ve spent the first couple decades of your life trying your best to be a straight white cis guy, you generally end up with some shit to unlearn, and the way you unlearn it is often by having strangers on the internet yell at you about it. The people at strap-on were more than happy to do that for you. You either learned to talk (and think) in a way that at least tried to take marginalized people’s experiences into account, or you got flamed off the internet. It was exhilarating.

There used to be a music festival called the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. It started in the seventies. In 1991, a trans woman named Nancy Burkholder was kicked out of Michfest for being trans, and it became the official Michfest Policy that trans women were not Womyn. So some people started holding a week-long protest called Camp Trans outside the Michfest gate, which grew into its own thing, with music and food and camping and queer stuff in the woods. Sometime around 2005, its leadership fell apart and some people from strap-on stepped up to take the Camp Trans wheel.

Camp Trans was a field in the woods deep in rural Michigan. There was a kitchen tent that didn’t have access to refrigeration, a welcome tent where people hung out with acoustic guitars and dense zines of gender theory, more tents back in the woods, and a taped off area maybe thirty feet across dense with ground hornets. It was not impressive, but it was perfect. Camp Trans, for me, was where strap-on stopped being a place to post and became a thing to embody. I leaned into being a humorless dirtbag.

Well, I’m bad at being humorless. Trans people are very often very funny. Jokes can be a defense mechanism, a trauma response: if you can make someone laugh before they remember that they hate people like you, you might get out of a 7-Eleven before they can hurt you. But I was good at being a dirtbag. I started wearing bandanas around my neck and romanticizing train-hopping without ever actually doing it. It would be impossible for me to overstate how valuable meatspace trans community is. Can I tell you something? We have bodies. All of us. Trans people maybe more than anyone else. And like it or not, the body keeps the score. (You should read Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score. It made me ugly cry on an airplane.) To put it reductively, trauma impacts our ability to exist in our bodies, which feels bad.

You know what else can make it hard to exist in a body?

Being trans.

It feels bad not to be able to be in your body.

The internet is great, but it is not a substitute for being in physical space with other trans people who care about at least some of the same shit that you do, smelling and seeing and hearing one another, nervous systems engaging directly. You might not realize how important that is if you’ve never had it. I had never had it before Camp Trans. I mean, I’d had meatspace trans friends beforehand, but I never got to spend a week with them. In the woods. With ground hornets. Experimenting with what it might feel like to legitimately trust another person in real time.

When you’ve learned to dissociate defensively around cis people, and you spend all of your time among them, and when they frequently make it clear that you are right not to feel safe around them, you can forget that it is even possible to let your guard down. That you don’t necessarily have to be alone to feel safe. That it is even possible to feel safe.

Even with all the complicated things about it—all the ways it probably was not safe—Camp Trans was a space that centered trans bodies. Even, by the time I got there, trans women’s bodies specifically. Camp Trans taught me that it is possible to feel safe in my body.

Fuck Michfest. Camp Trans saved my life.

Hey, on the topic of Michfest and other regressive, transphobic things, can I give you a tip? If you find yourself interacting with someone who is “critical” of “the transgender movement” or whatever, ask them what they think trans people should do. If the only thing they can come up with is “not be trans,” point out that the vast majority of trans people have already tried that, and it tends to make us suicidal. If they can’t come up with anything better than “don’t be trans,” please understand that they very literally want me and at least 1.4 million other Americans—not to mention way, way more people outside the US—to die.

Don’t let them equivocate. “What should trans people do?”

All they’ve got is “die.”

It’s kind of intense.

OTHER AUGHTIES QUEERS

A lot of Nevada is me processing my 2007 move from New York to Oakland. Oakland fucked me up. When I moved there, I found myself spending a lot of time in a queer demimonde full of people who had graduated from Smith, which I understand was lousy with trans mascs at the time but which would not admit an out trans woman for another seven or eight years.

It’s not like all the queers in Oakland were mean or anything. There was a lot of trans-inclusive language, and there were a lot of trans people. It’s just that there were almost no trans women who weren’t me. Which is not to say that there were no other trans women in Oakland, obviously. Or other queers. Just that I lived and dated and socialized in this tight community and nobody else in it was a trans woman.

I blamed myself for feeling out of place. I mean, I had found a queer community! I was a queer woman, these were (mostly) queer women! They were explicitly okay with trans people! So why did I keep leaving parties and potlucks and performance nights crying?

Long story short, the queer community just wasn’t there yet. Y’know? Plenty of good intentions, no idea what to do with them. It was like, one moment I’m exhilarated, talking to trans women friends about this new book called Whipping Girl, and the next I’m going to Dyke March where cisgender radical cheerleaders are yelling the word “tranny” at me.

It was exhausting to be outside my house as someone who was read as trans. In retrospect, of course, it’s clear that I was doing everything I could not to admit that it was also exhausting to be inside my house when the queers were there, too.

It was lonely.

Nevada is dead set on treating one trans woman’s experience with honesty because I was so fucking exhausted and sad that my own was never treated that way.

I felt invisible to the world at large and also invisible to the demimonde, so it was kind of a shout that I—and therefore we—exist.

Around this time, I printed up some copies of a zine in which I reprinted three essays by trans writers explaining why we wanted cis people to stop calling us “trannies.” I made them to keep in my purse and give them to people when they used that word, so that I could hand them a zine instead of having an emotionally draining and most likely pointless conversation. In a sense, Nevada was an extension of that zine.

THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK

When I first moved to Oakland, it was into a big collective house called the Fork in the Rode. There were, like, eleven of us in a four-bedroom house on North Sixty-First Street. Somebody lived in the garage. Somebody else lived in a plywood shack in the backyard for a while. Two people lived in the driveway in a van that didn’t start. At one point we had a rat problem, but to make it feel like less of a problem, we called them bunnies. I was a fucked-up mess. It was a great fit. And at some point during the year or so that I lived at the Fork, my friend Fischer loaned me their copy of an anthology called This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa.

I want to be careful, because while one of the stated goals of This Bridge Called My Back was to educate middle-class white women like me, it is not a book about me. What I mean is, I hope I’ve been able to learn from its contributors. Anti-racist work is work white people need to be doing every day, and This Bridge Called My Back was a jolt—a wake-up call—in my own anti-racist work. Not to gush, but it remains an achievement that we’re all fortunate to have. I just picked up my copy to flip through a little as I write this, and while the range of pieces by contributors including Norma Alarcón, Barbara Smith, the Combahee River Collective, and Audre Lorde covers a lot of ground, the book remains as vital today as I imagine it was when it was first published in 1981. It’s an absolute classic. Full stop.

Picture me in Oakland in 2007. Six feet tall, only on hormones for a couple of years. My hair was part blond and part hot pink with dark roots. I remember a lot of hot-pink eye shadow. I was not subtle. But at the same time, I really wanted to be passing for cis. Or more specifically, I really wanted to be cis. It hurt that I was not. I got shit for being trans in public pretty regularly, and it shattered me every single time.

So why didn’t I learn to do less gaudy makeup and stop dying my hair? Why wasn’t I making more of an effort to pass for cis, if it hurt so much to be read as trans?

A couple reasons. First, I didn’t know how, which would have been a scary kind of vulnerable to admit. Also, what if I worked really hard on passing and couldn’t? That felt like it would be even more heartbreaking. Further, I don’t think I was able yet to articulate the trap that is “I should be able to do whatever I want with my body, but I also shouldn’t have to face unfair consequences for it.” In other words, it was the transition thing of having a new, more vulnerable location under patriarchy, but not yet really having come to terms with the ramifications of that location.

Complicating this was the fact that for years I had been devouring narratives of queer liberation written by cis people. I’ve written elsewhere about how lots of ideas conceptualized by cis people to describe things experienced by cis people don’t map neatly onto trans experiences—like, for example, male privilege. (Do trans women have male privilege before transition? Kinda. Do trans guys have male privilege after transition? No matter what Maria Griffiths might tell you, the answer is probably also: kinda.) What I was learning—and what I could not find language for—was that the rules of liberation for cis queers are different from the rules for trans people.

This is why I felt so lonely in my queer Oakland community.

Now picture me reading the faded maroon cover of an anthology by a number of, at the time, woman-identifying writers talking about living at the impossible nexus of public vulnerability, as women of color under white supremacy, and private vulnerability, as women of color marginalized within predominantly white, lesbian, feminist, and other progressive/radical communities.

The way that paralleled what I was experiencing—of course, with different specifics—was a revelation. The pain of feeling marginalized wherever you were, and the corresponding power of sharing space with people who got it. Who got you.

This Bridge Called My Back wasn’t about me, but it was talking to me—on more than one level. Both deepening my own sense (and work) of solidarity and giving me a framework for better understanding my own positionality.

It led me to Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and other marginalized feminist/womanist thinkers. I still feel like, if I have anything intelligent to say about being trans, it can probably be traced directly back to their work.

ALSO OTHER BOOKS

There were a lot of books that influenced Nevada, of course: Dennis Cooper and Junot Díaz were enormously important to me while I was writing it. But here I want to focus on another writer who made it possible to write this weird little novel: the singular Joanna Russ.

I DuckDuckGo’d it to see if her essay “What Can a Heroine Do? or Why Women Can’t Write” was online anywhere, and it turns out that as of this writing there’s still a scan of it on the Topside Press Tumblr.

That essay, specifically, felt like it gave me permission to structure Nevada the way I did. In it, Russ systematically breaks down all the ways that the Western hero’s quest narrative fails women. It’s incisive and funny in a way that I wish I could write: “When critics do not find what they expect, they cannot imagine that the fault may lie in their expectations.”

She opens with a number of familiar premises with the genders flipped: “Two strong women battle for supremacy in the early West”; “A phosphorescently doomed poetess sponges off her husband and drinks herself to death, thus alienating the community of Philistines and businesswomen who would have continued to give her lecture dates”; “A beautiful, seductive boy whose narcissism and instinctive cunning hide the fact that he has no mind (and in fact, hardly any sentient consciousness) drives a succession of successful actresses, movie produceresses, cowgirls, and film directresses wild with desire.” She goes on to write about patriarchy and gender and to outline the ways that what is coded as success for men tends to be coded as failure for women.

Hold that thought.

I’m going to use the word “transition,” but I’m going to put quotation marks around it, because I think it’s kind of a goofy framework: a cisnormative way of understanding what trans people do. I think a more accurate way to describe the process of being trans—or the journey or whatever—is as one that starts with a cisnormative framework for understanding what it is to be trans and moves to one that more realistically encompasses the complexities of the lived experiences of trans people. This means that “transition” doesn’t start with hormones or coming out. It starts way before, with the feeling a lot of us have pretty early on that something’s wrong. Or maybe it starts with the early, initial work of trying to figure out what, exactly, it is that’s wrong.

I don’t think we live in a culture in which that particular transition has an end point.

One of the things I wanted to confront in Nevada was this cisnormative idea that, for trans people, first you are one of The Two Genders, then you are in a fascinating in-between place while you transition, and then you are more or less uncomplicatedly the other of The Two Genders. And because the mysterious in-between phase is the most salaciously interesting thing to people who don’t have to go through it, I decided to cut it out. I wanted to look at the ways that the part “before transition” and the part “after transition” are not, actually, characterized by being a cisgender version of one or the other of The Two Genders. So I wrote a character who was “post-transition,” whatever that might mean, who was still living with the fallout from a lifetime of repression as well as the trauma of that transition phase, and I wrote a character who was “pre-transition,” whatever that might mean, because the head full of mixed-up shit that you can’t help but walk around with when you live in that state does not have a corresponding cisgender experience. Y’know? The cisnormative approach to honoring this difference would be to pay attention to the difference during that middle “transition” period; the approach that respects the complexity of trans people’s lived experience says, Well actually, no, trans people are trans before and after “transition.”

And I should be clear: even this model does not describe all or even, necessarily, most trans lives. Lots of nonbinary experiences don’t follow this model, and even trans people who identify within the gender binary still have very different experiences. It’s almost as if the white settler colonial construction of The Two Genders is violently inadequate.

But the question, then, was: how do you fit all that into a story with a call to adventure, a road of trials, a vision quest, et cetera?

Well, you don’t, says Joanna Russ. You don’t have to. The first half of Nevada is about a trans woman named Maria, and then the second half is mostly about a kid named James who’s trying to figure out whether he’s trans, because I wanted to interrogate both the “before transition” and “after transition” stories.

So why does Maria show up in James’s half? Well, it’s a separate thing, but it’s because one of the most common ways for trans women to self-flagellate is with a whip labeled “I should have come out sooner.” It’s unfair to ourselves. It takes as long as it takes to figure out what you need to figure out—and to figure out what you need to do about it. But we still do it. I thought it would be funny to make that explicit: what if, while you were still unaware / in denial about being trans, some trans woman fairy godmother had shown up and not only told you to your face that you were trans but tried to convince you.

Would that have made you come out sooner?

I won’t spoil the ending here, except to say that people have strong feelings about it. It’s unconventional. And Joanna Russ gave me permission to write it that way.

PRETTY QUEER

Prettyqueer.com was a smart-ass website started around 2011 by the people who went on to start Topside Press—Julie Blair, Red Durkin, Riley MacLeod, and Tom Léger.

At this point I’d given up on Nevada. I’d worked on it a lot, but the second half just wouldn’t come together. I knew what I wanted it to do, but I didn’t know how to make it do it. I’d sent it to Soft Skull, but they were not interested.

Fuck it, I thought. I’ll take what I learned from it and write another one.

I don’t know how much of an impact it made on anyone else’s life, but to me, Pretty Queer was a very big deal. The editorial board was four cool trans people you wanted to hang out with. I knew Julie and Red from Camp Trans. They got it. We could write things that did not pander to cis people, and people actually read them. They published my friends. You would publish a thing and in the comments people would tell you they hated it, which meant they had read it!

If I recall correctly—I’m afraid to DuckDuckGo it on the Wayback Machine—I mostly contributed fake interviews with trans celebrities in which they said the cool things I wished they would say, instead of the disappointing things they actually tended to say. And Pretty Queer paid me for that! In fact, in looking through old emails for this, I found one where I was like, “You guys I am working as many hours as I can get, but I can’t afford hormones or rent—can you front me money in advance for future articles?” They totally fronted me that money. I doubt I ever actually turned in those articles.

I don’t think I’d been paid for anything I’d written before.

The Pretty Queer era bled into the Topside Press era. I was in Portland, Maine, and they were in New York, so when Topside’s first book, The Collection: Short Fiction from the Transgender Vanguard, came out, it was an easy bus ride for me to get there for readings. Plus, they chose a story I’d written to open The Collection. I felt like a rock star.

Those three years were intoxicating. At first, Topside Manor was Tom and Julie’s apartment. I slept on their couch a lot. I remember many, many Bud Lite Lime-A-Ritas in what felt like an endless, endlessly hot and humid Brooklyn summer, talking shit all night about representation, literature, trans literature, how to be trans in the world, bodies, intersectionality, and what could be salvaged from transphobic seventies and eighties feminisms.

Riley was probably the only real punker. He had one of those chain necklaces with a lock on it and a dog-bone name tag, and at one point I think he had lived on a houseboat that sank. Tom was connected to what felt like this whole other gay world: he knew a lot about ACT UP and which gay men from the previous couple generations of activists were jerks. Also I think he’d done a literal MFA. Julie was a hilarious and brilliant weirdo with an encyclopedic knowledge of nineties garbage—“I only happen to enjoy typesetting because I’m perverted,” she told Lambda Literary—and Red is the funniest person you’ll ever meet. Also I’m pretty sure she said the If gender is a construct, so is a traffic light thing that gets quoted sometimes from Nevada, and I stole it.

There was a revolving door of other geniuses coming through all the time: wingnut San Francisco artist Annie Danger; Ryka Aoki, who publishes with Tor now; Brynn Kelly, again, a writer and genius who we all miss; a bunch of contributors to The Collection. Sometimes Sarah Schulman would just be hanging out. Casey Plett and Sybil Lamb were around. Loads of others.

Of course, within a few years, the wheels came off. Topside fell apart and became something else and then fell apart again. Some people made some bad decisions, some people got hurt, and some people disappeared. Topside doesn’t exist anymore, nor does Pretty Queer, but for a couple years, it was a legitimately beautiful thing.

When Topside first asked to see it, Nevada didn’t work. But Tom encouraged me to send it anyway. I did.

He agreed: yep, the second half doesn’t work.

But he shared it with Red, Julie, and Riley. They all saw something in it and worked hard with me to get it to do what I wanted it to.

I’d never been through such an intensive editing process. I pushed back pretty hard on what felt like MFA bullshit, which in retrospect probably was not (“This character doesn’t actually want anything”—Imogen Binnie, 2012). I think the editing process of your first novel is probably always a bit of a rude awakening, and I was fortunate to go through it with them.

NOW

Nevada opened a lot of doors for me. I sold a movie. People actually listened to a podcast I made, by myself, in a car. I toured the US, Canada, the UK, and Ireland, crashing on the couches and floors of strange queers—many of whom I had previously known as screen names from strap-on. I sleep in a bed now, instead of an old futon mattress on a series of Oakland collective house closet floors. That bed is in a house I share with my gay wife and two small, wild children. I’ve mostly kicked social media. When I’m not being a big-shot LA TV writer, I’m a social worker and therapist.

I’ve even had a few months here and there where money wasn’t stressful, if you can believe that.

Parenting kind of makes you a recluse, and trans women are prone to hermitism to begin with, and also our house is in rural Vermont, so I don’t really do stuff or see people the way I used to. It’s not like I’m a different person—but I might be less of a fucked-up mess. Which was all Maria wanted, too, wasn’t it? To be less fucked-up?

In the Topside Press era, we talked a lot of shit about the transgender memoir as a literary genre, because so often it felt like begging for validation from cis people: “Maybe you wouldn’t be so mean to me if you knew how much pain I’ve endured!” But it’s been a decade. Maybe we’ve opened some doors for the kinds of spaces that trans stories—fictional or otherwise—can occupy. Not to mention, Janet Mock basically turned the transgender memoir into something incisive, progressive, and cool all by herself. Twice. The cultural landscape has definitely opened up. Have you read Janet, Ryka, Torrey Peters, Casey Plett, Vivek Shraya, Jackie Ess, or Charlie Jane Anders? Have you seen Pose, or Euphoria, or listened to G.L.O.S.S. or 100 Gecs? I, personally, wrote on a TV show where Laverne Cox played a lawyer who had a season of ups and downs with a hot boyfriend, as well as trans friends with names and lines. There’s still a lot of work to do, but things look pretty different. I don’t know about Nevada being ground zero for modern trans literature, but I do feel fortunate that this funny little book was able to contribute to that.

Imogen Binnie is the author of Nevada, which won the Betty Berzon Emerging Writer Award and was a finalist for the 2014 Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Fiction. A writer for several television shows and a former columnist for Maximum Rocknroll, she lives in Vermont. This piece is adapted from the Afterword to Binnie’s Nevada, which will be reissued by MCD x FSG Originals, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, in June.

May 3, 2022

Other People’s Diaries

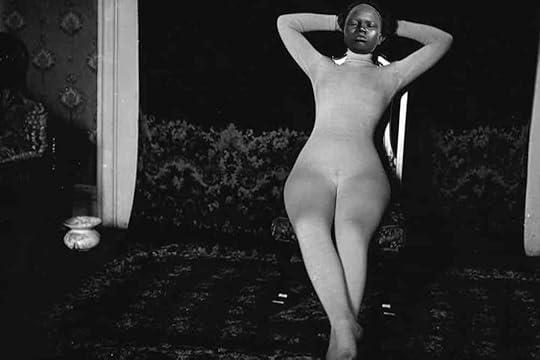

Annie Ernaux. Photo by Catherine Hélie. Courtesy of Éditions Gallimard.

While reading Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion, I often caught myself mistaking it for a diary. The memoir details an illicit affair in prose that feels startlingly immediate, full of particulars that seem to surface in real time: a skirt in a Benetton shop; a list of fortune-tellers in the telephone book; the faded lettering of a plaque that reads PASSAGE CARDINET, near where the author sought a clandestine abortion years before. Yet I was continually made aware that time had passed, and this was last year’s love seen through this year’s eyes: “From September last year,” Ernaux writes, near the beginning, “I did nothing else but wait for a man: for him to call me and come around to my place.” The details of this “most violent and unaccountable reality” have been refracted and altered, distilled into a remarkable book.

I recently read A Girl’s Story, Ernaux’s 2020 memoir of another doomed and passionate love—her first, in the summer of 1958—and was struck by her description of the process by which she reconstructed her former self, the diligence with which she studiedthis young “girl of ’58.” Ernaux googles her summer-camp bunkmates and considers pretending to be a journalist so she can call them up and ask about herself. She looks at a photograph of her long-lost lover’s great-grandchildren. While reading an old diary, and letters she sent to a classmate, she recognizes certain falsenesses in them—pretensions, lies, self-deceptions. The quotations from books she copied down in 1958 now strike her as a more direct means of access to her state of mind then. All memoir involves time travel, and yet Ernaux, as she twists and turns, trying to cross the schisms between her various selves, manages to create what feels like a new tense—a literary time zone that can hold it all at once.

In our Spring issue, the Review published some of the source material on which Ernaux based Simple Passion: selections from her real diaries from 1988, which describe her affair with a married diplomat from the Soviet Union. Here is that violent and unaccountable reality, recorded at a distance of mere hours. Many entries are short, factual, engaged with the torment of love and logistics: “Last night he called. I was sleeping. He wanted to come around. Not possible. (Éric here.) Restless night, what to do with this desire?” Others are breathless and breezy: “I realized that I’d lost a contact lens. I found it on his penis. (I thought of Zola, who lost his monocle between the breasts of women.)” To read them is to encounter something like a pentimento, the revelation of writing underneath other writing—a quality that already suffuses so much of her work. We can, of course, marvel at what Ernaux was able to make of these entries in Simple Passion. But they offer their own distinct and potent pleasures, the rare, delightful, occasionally shocking intimacies of reading someone else’s private thoughts.

To mark the appearance of Ernaux’s diaries, the Review has been asking writers and artists to share pages from their own. Yesterday on our website, we published the first in the series: part of the poet Elisa Gonzalez’s 2018 journal, which documents the aftermath of an affair and a marriage. Reading them now, she, too, had some distance from this former self. “I used to accept, unquestioningly, that pleasure was fleeting,” she writes in a postscript. “but now I think it has an afterlife, during which we integrate it into all the griefs we also feel.”

These diaries feel like gifts, or offerings, that are unlike any other kind of writing. There is, as Ernaux herself writes in a brief introduction, “a truth in those pages that differed from the one to be found in Simple Passion—something raw and dark, without salvation, a kind of oblation.”

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

Redux: The Marketing of Obsession

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

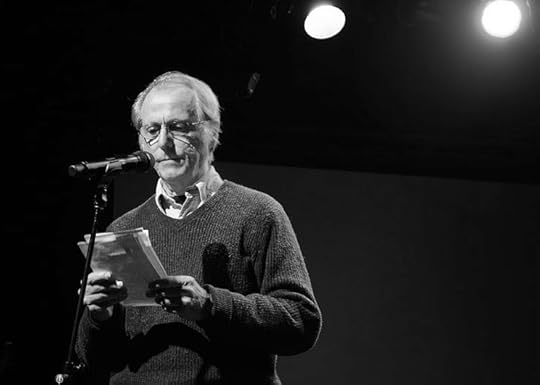

DON DELILLO, CA. 2011. PHOTOGRAPH BY THOUSANDROBOTS.

“Barneys was more than a department store,” issue no. 239 contributor Adrienne Raphel reminisces in a new essay on the Daily. “A glowing spiral staircase, white as milk, wound its way through the store—the Guggenheim, but make it fashion.” This week, we’re unlocking an Art of Fiction interview with the bard of postwar American consumerism, Don DeLillo, as well as Zadie Smith’s story “Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets,” Mary Ruefle’s account of shopping—as in shoplifting—at Woolworth’s in “Milk Shake,” and a series of photographs taken of Paris’s legendary market, Les Halles, in the sixties.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and art portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

INTERVIEW

The Art of Fiction No. 135

Don DeLillo

INTERVIEWER

Frank Lentricchia refers to you as the type of writer who believes that the shape and fate of the culture dictates the shape and fate of the self.

DELILLO

Yes, and maybe we can think about Running Dog in this respect. This book is not exactly about obsession—it’s about the marketing of obsession. Obsession as a product that you offer to the highest bidder or the most enterprising and reckless fool, which is sort of the same thing in this particular book … And in Libra, of course—here we have Oswald watching TV, Oswald working the bolt of his rifle, Oswald imagining that he and the president are quite similar in many ways. I see Oswald, back from Russia, as a man surrounded by promises of fulfillment—consumer fulfillment, personal fulfillment. But he’s poor, unstable, cruel to his wife, barely employable—a man who has to enter his own Hollywood movie to see who he is and how he must direct his fate.

From issue no. 128 (Fall 1993)

PROSE

Miss Adele Amidst the Corsets

Zadie Smith

“A corset,” she repeated, and raised her spectacular eyebrows. “Could somebody help me?”

“WENDY,” yelled the voice behind the curtain, “could you see to our customer?”

The shopgirl sprung up, like a jack-in-the-box, clutching a stepladder to her chest.

From issue no. 208 (Spring 2014)

POETRY

Milk Shake

Mary Ruefle

I tried her milk shake, I told her what I had done, the vanilla shake came, and we salt-and-peppered that one, too, and afterward we were bored, so we went shopping—we were in Woolworth’s after all—though by shopping we meant shoplifting, as any lonely bored thirteen-year-old knows. Vicki stole a tub of the latest invention, lip gloss, which was petroleum jelly dyed pink, and I stole a yellow lace mantilla to wear to Mass on Easter Sunday, though I never wore it to Mass; I wore it to confession the Saturday before, confessing to the priest that I had stolen the very thing I was wearing on my head.

From issue no. 216 (Spring 2016)

ART

Les Halles Photographs

Harold Chapman

Les Halles Centrales de Paris—the Central Market of Paris—is in 1967 enjoying only an apparent reprieve. In decreeing its removal, the public powers have long since signed its death sentence. But this eight-hundred-year-old mastodon, despite its advanced age, retains a strange vitality, and does not seem so easy to move around. Its transfer to Rungis, originally anticipated for 1966, has raised many and difficult problems, not all of which have been solved. So it is still with us, at the heart of Parisian life.

From issue no. 40 (Winter–Spring 1967)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-nine years’ worth of archives.

May 2, 2022

Diary, 2018

Photograph by Caryl González.

In our Spring issue, we published selections from Annie Ernaux’s 1988 diaries, which chronicle the affair that served as the basis for her memoir Simple Passion. To mark the occasion, the Review has begun asking writers and artists for pages from their diaries, along with brief postscripts.

July 13, 2018

I was up all night and it’s afternoon now. Maybe writing this will let me go to sleep. Sometimes it feels as if I’ve been awake for six months. Longer? In Cyprus I felt like I never slept. Even when I did my body felt impatient, braced, alert, waiting for the knock of the cat’s paws on the bedroom door at 5 A.M. I would be out of bed before she could start mewing for food. “Acutely, terribly awake,” I wrote in a poem I’m still trying to finish. She knew I was an easy mark, looking for an escape into the day. I saw nearly every sunrise from my window onto the garden. The bougainvillea. “I want to make love to everyone who’s ever lived,” I wrote in the same unfinished poem. An unwise wish, and a lie, of course, if taken literally—but the feeling. What was I trying to ask for? Pleasure. Recompense from the world. Surprise. The end of desire. Something.

And now I’m a sad woman, apparently; sleeplessness is entirely changed, desire’s not ended but it holds hands with pain. He does not come to me because he does not want to come, and not for any other reason. It’s all very boring, this recitation. Last night it rained horribly but even so I forced myself to go to Chelsea for dinner with J. and her friend Y., who has one of those jobs I always want when I find out they exist. He’s an expert on repairing antique, or simply old, sound equipment. I envy expertise that seems both useful and specific. And like you had to actually do something to acquire it, like it’s not just blather. J. was late, so I had to make conversation with Y. while he finished a blueberry galette. The galette was a godsend, actually, since I had just listened to his complaints about how blueberries are an inferior fruit, tasteless, and the only reason he was making this was because J. had requested it. And then, after I had enough wine to feel like talking, J. arrived, and everything improved as they sparred the way old friends do. I didn’t eat enough for Y.’s satisfaction, so he chided me and then forgave me after I ate more galette, and then he started playing records on a record player so beautiful I didn’t want to go near it, and then J. got out the molly and coke. We took a signed photo of a famous musician off the wall to do lines off of, now I don’t remember who, but Y. joked “he’d approve” so it was probably Keith Richards or someone like that. I saw K. R. joke once about how his ghostwriter did all the work on his memoir. It sounds like a relief to have someone translate, or invent, your memories, to tell your life story so you can read it.

I came back to this weird temporary home sometime around 4:30. I took the subway, even though it would have been so much nicer to take a cab up Madison Avenue in the dark, all the lighted shop windows flashing by, emptied of their luxuries though still so bright. But I’m very poor. I had breakfast plans with C. at 9:30, and since I couldn’t sleep from drugs and/or ambient heartbreak, I didn’t cancel. Instead I took a shower, smashed a cockroach, and stared at the gray ceiling till it occurred to me that I could walk there. So I walked all the way from Eighty-Second to MacDougal, the chemical ecstasy filling me so that I felt as if I were expanding as the city did, awakening. It was the happiest I’ve been since I came back, alone. I thought, No one in the world knows where I am. Why do I always return to that thought as a source of, if not happiness, then pleasure? I remember in Warsaw when I’d tell D. I was going out somewhere, or had an appointment, and instead I would walk south to Praga-Południe or crisscross the bridges—there was no point in the lie, he wouldn’t have cared. But the claustrophobia of our life together was such that I just lied, which should have told me something about how it would end. And I was so happy, even when it was cold and smoggy and gray, to be alone and unfindable. I know why, then, it felt liberating. But now, when I clatter around this big house missing everything about love and proximity? I mean, yes, drugs are an explanation, but I’m writing about this because the elation was more than that. There’s something bigger than solitude in being lost to everyone who knows you, to being open only to the eyes of strangers. Real loneliness? And that loneliness is an escape from owing everything to everyone I love. I suspect, at least. If I could have the love I want to have exactly as I want it, but I could never think exactly that—no one on earth knows where I am—again, would I choose the love? No, I think. But maybe I am just telling myself that. Walking around in a circle again, as Professor B. said, unable to choose whether to be inside or outside: love, loneliness.

Then again in this case I don’t have a choice, and I should stop prattling and go to sleep. Or to bed, even if I can’t sleep. When I showed up, C. said, Why do you look so happy? I told him. He laughed at me; he always enjoys my chaos, so I always confess it to him. Patti Smith, who knows C., came up to say hello on her way out. I didn’t say I’d seen a signed photo of her on the wall last night. I just stayed quiet and admired how—at least there in the café every morning—she chooses exactly who she speaks to, and when. Drinks her coffee. Writes. I envy that.

***

Postscript:

At the end of 2017, I finished a Fulbright in Poland and moved to Cyprus with my husband. It was to be a geographic pause of uncertain length during which we planned to apply for a U.S. immigrant visa for him. Secretly, I hoped the sea and sun—and the return to a place where he’d spent the happiest years of his childhood—would cure his depression. It did not. I, however, fell in love with someone there with whom there was no possible future. My husband found out; everything went to hell. In June 2018, I retreated to a friend’s parents’ otherwise empty townhouse on the Upper East Side, a lavish setting that belied my poverty. I’d exhausted my savings, had no job, and ate a nauseating number of boiled eggs, depending on the kindness of friends for more substantial meals. And yet, as my diary reveals, my biggest preoccupation was my double heartbreak: the end of my marriage and the end of my affair. What Proust calls “the charms of an intimate sadness” beguiled me. I used to accept, unquestioningly, that pleasure was fleeting, but now I think it has an afterlife, during which we integrate it into all the griefs we also feel.

In the general (and tedious) chorus of misery of entries from this time, typed into Microsoft Word because my handwriting is often incomprehensible even to myself, this entry is an aberration in its strange pleasure. It interests me now because I have been thinking about forms of loneliness. Last year, my youngest brother died. Now I often feel loneliest in company—looking around a party, knowing that I am the only one who feels his absence in the world. (Another Proust line I repeat to myself now: “The absence of a thing is not merely that, it is not simply a partial lack, it is a disruption of everything else, it is a new state which one cannot foresee in the old.”) But even that specific loneliness brings an odd pleasure: a confirmation that love hasn’t been lost along with him. If I could address the Elisa of 2018, who believed in the surpassing intensity of her suffering even as she called it “boring,” I wouldn’t tell her she was foolish. I would say that the division she imagined between love and loneliness was at least partly false. Loneliness is a figure of present-tense love, for the lost person and for those strangers who represent, to her, the as-yet-unknown beauties of the world. She was correct, though, that there’s no choice to be made.

Elisa Gonzalez is a poet, fiction writer, and essayist whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award.

April 29, 2022

Venice Dispatch: from the Biennale

Jacqueline Humphries, omega:), 2022 (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

My mother is a Renaissance historian who specializes in Venice and paintings of breastfeeding; her books and articles have subtitles like “Queer Lactations in Early Modern Visual Culture” and “Squeezing, Squirting, Spilling Milk.” I have an early memory of her taking me to a Venetian church to see Tintoretto’s Presentation of the Virgin, a depiction of a three-year-old Mary being brought before the priest at the Temple of Jerusalem. The child Mary is shockingly small. Dwarfed by a stone obelisk carved with faint hieroglyphs, she ascends a set of huge, circular steps inlaid with abstract golden swirls. Onlookers crowd around, including three sets of fleshy women with children who dominate the scene and who, my mother explained to me, are likely wet-nurses. Breastfeeding women are often allegories of caritas: Christian care. This vision of femininity—as carnal, and as both literally and figuratively nurturing—reappears, centuries later, virtually unchanged, as the central conceit of Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale, “The Milk of Dreams.” In her selections, the woman’s body once again serves as a breeding-ground for personal and political metaphors, and the artist’s relation to her own embodiment as cornerstone of her creative practice.

Alemani’s show, which includes an unprecedented eighty percent women artists from the highest number of nations in the Biennale’s history, was wide-ranging, surprising, and often exciting. But the corporeal interpretive framework that “Milk of Dreams” insists on was disappointing in its failure to imagine (imagination being another theme of the show) a new future for feminine forms of expression. The description for every single subcategory of the main exhibition references “hybrid bodies,” “corps orbite,” “somatic complexity,” et cetera. Even the work described to me as “abstract” was mostly vaguely suggestive of womblike figures. There was a lot of fan art dedicated to Donna Haraway, whose “Cyborg Manifesto” once offered a revolutionary vision of embodiment—but was published nearly forty years ago. If the work wasn’t thematically body-related, it likely involved a textile, a well-known medium for women (often worn on bodies). And though many of the “leaves, gourds, shells, nets, bags, slings, sacks, bottles, pots, boxes, containers” (this is the actual title of one of these sub-exhibitions) were really quite cool, it’s frustrating to be told to relate to oneself solely as some version of a clay pot, even a subverted one.

Among the artworks less mired in the biomorphic, I liked: Jessie Homer French’s paintings of climate disaster transposed into flat, Wes Andersonian landscapes, including one in which pixel-like stealth bombers glide over desert shrubs and windmills; Monira Al Qadiri’s shimmering, slowly rotating, jewel-toned sculptures inspired by the Gulf region’s “petro-culture,” which resemble rococo drill bits hypertrophied into palaces; a sensorial maze by Delcy Morelos, made out of dense cubes of soil, cacao, and spices, which was somehow both comforting and uncanny; and Jamian Juliano Villani’s painting of a traffic light submerged in a whirlpool of foliage. Her goat wearing UGGs was great, too, and perhaps the only nod towards the girly in the show. There’s a video by the Chinese artist Shuang Li, which seems to be narrated by human (?) manifestations of digital images or pixels, in a series of surreal statements formulated with the narrative simplicity of religious or mythological texts. The strangest sequence features a chubby white girl illuminated by a fluorescent ring light eating chicken fingers (perhaps our Mary at the temple), whose moving image simultaneously tunnels into and spirals out of itself, until the ring light appears to be the entrance to a psychedelic well, or a black hole (of YouTube).

Monira Al Qadiri, Orbital, 2022. Courtesy of the artist. Photographs by Tony Elieh.

Easily most impressive, though, was Jacqueline Humphries’s massive four-panel abstract painting omega:). From afar, it gives an impression of colors moving very quickly, like a glitch radiating for one second across a torrented video. But up close, it’s painstakingly precise, composed of many shapes, similar yet irregular, somewhere between the rectilinear patterns on QR codes and the organic mottle of army camo. They’re intensely black, and tactile, with multiple layers of red, green, yellow, and blue paint underneath them that contribute to the vaguely migrainous feeling I had of hallucinating colors into a black-and-white image. (There were also two smaller paintings by Humphries, composed of small black Xs and dashes, like ASCII characters, to similarly hypnotic effect.) Stepping back and forth between the two scales gave me a more genuinely “dream”-like sensation of three-dimensionality, movement, and digitality than any sculpture or video in the show. Several people told me that they liked these paintings but that they were clearly out of place in the exhibition, given Alemani’s theme, which, in addition to the orgy of bodies, focused on surrealism—highly literal figurations of the content of dreams. Humphries’s paintings, instead, stimulate or simulate the feeling of unreality by playing at the edges of perception itself, through masterful manipulations of form. And her gesture towards femininity is pleasurably abstract, too: omega:)’s focal point is a set of gloopy, sparkly letters, bright pink, in the rounded style favored by middle school girls—her own initials, JH.

Jacqueline Humphries, omega:), 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

On my last day in Italy, I saw Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, a cycle of frescoes dating to the early fourteenth century, and a masterpiece which doesn’t need a review from me. But it’s worth describing the drama of technology and timing through which the experience was staged. Upon arriving in the verdant park surrounding the chapel, you are first led into a glass cube affixed to the small stone church. You sit, on transparent plastic chairs, in this “Corpo Tecnologico Atrezzato” for more than fifteen minutes, during which time your body humidity is lowered and cleansed of smog particles, so that your visit will not harm the fragile paint in the chapel; this is explained in one of two videos shown to you on a small flat-screen. The second video, melodramatically inflected by the Italian narrator and underscored by stirring music, is a moving gloss on the stories in the paintings. Once purified in body and spirit, you are allowed to exit this space station and, for twenty minutes, enter the chapel itself, which feels, by then, like a time-travel machine. In the chapel, surrounded by the white-noise sound of ventilation technologies, you can feel the compression of hundreds of years of human history—and the future, too.

In addition to that of Christ, Giotto’s frescoes depict of the life of Mary. Motherhood and care are all very well; “the body” is certainly important. But there’s also the Virgin, who is certainly a vessel, but actually far less corporeal than her bleeding, perspiring, emotional-labor-performing, dying son. Even as the breastfeeding Madonna Lactans, she usually looks detached, almost plasticene, more like a meditative Renaissance Barbie than a mother. One likes to imagine her preoccupied with the heavens, with her ideas. In Giotto’s Annunciation, as in most, she is reading alone in her room. (Mary is understood to have been studious.) And, in an amazing final trick of circumventing her body, rather than die, she simply ascends.

Olivia Kan-Sperling is assistant editor at The Paris Review.

April 28, 2022

The Secret Glue: A Conversation with Will Arbery

Will Arbery. Photo by Zack DeZon.

Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning, which opened at Playwrights Horizons in 2019, continued to work on me long after I’d emerged from the theatre into the megawatted midtown Manhattan night. The play’s world—much like the white, rightwing, Catholic, intellectual milieu of Arbery’s upbringing in Bush-era Dallas—wasn’t something I’d seen onstage before. We meet Arbery’s cast of five characters seven years out from an education of Plato and archery at an ultra-strict religious college. They hunger for passion, touch, reason, the pain and vitality of others, and for one another. They are characters to be reckoned with, if kept at a careful distance.

Arbery’s latest work, Corsicana, an excerpt of which appears in the Spring issue of The Paris Review, is a different kind of play, one that invites you in rather than takes you over. It is about gifts, the making of art, and, more poignantly, the sharing of it. Named for the town in Texas where the play is set, Corsicana opens in the home of Ginny, a woman in her midthirties with Down syndrome, and her slightly younger half brother, Christopher, who are grieving the recent death of their mother. Ginny has been feeling sad, depressed maybe, and Justice, a godmother figure to the siblings, introduces them to Lot, a musician and artist who uses discarded materials to create sculptures that he rarely shows anyone. Lot got a graduate degree in experimental mathematics, and, as he tells Christopher, succeeded in proving the existence of God, although he threw the proof away. “Art’s a better delivery system,” he says.

Arbery’s dialogue has an unnerving way of being at once caustically funny and prophetic; perhaps it’s no surprise that he is much in demand as a writer for television and film. Earlier this month, I called him in London, where he was working as a consultant on season four of Succession, a series that I, from my sofa in Brooklyn, was struggling, without much success, to resist rewatching.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve recently picked up quite a bit of TV work. Are you eager to make your return to the theater?

ARBERY

I’m writing for film and TV a lot more than I did before the pandemic. Heroes of the Fourth Turning closed in November of 2019, and I went to Los Angeles and got some film and TV work lined up. I worked as a consultant on season three of Succession. Then the world stopped. But luckily, I was able to line up enough film and TV writing to keep me going during the pandemic. It ended up being three TV projects and three feature films. That’s way too much for one person to handle. I wouldn’t do it quite that way again. But I spent my twenties hustling in the theater and barely scraping by financially and having monthly panic attacks about making rent. So I thought, I’m going to take these opportunities because they might not come up again.

I was able to develop—for the first time—a writing routine that felt sustainable and enjoyable. It was something about having time away from the theater, and finally being able to move into my own apartment. But then, of course, I learned about the film and TV industry. In theater, you have complete control over what that play is. Every word in it. People have thoughts, and it’s collaborative, but in film and TV there are many, many notes. There are the core producers—I love those people. But when it gets to the levels of the financier or the studio or the streaming platform or the network, the notes start to feel more anonymous and by committee. You’ll start being on Zooms, and there are three people on there who you’ve never seen before. That makes me really excited about going back into rehearsal for a new play.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds like you prefer to have more control over your projects. Or do you like to surrender a bit?

ARBERY

No, I don’t like to surrender. Letting go of the things you can’t control is a good quality, but creatively, it’s very difficult.

INTERVIEWER

Was there a play that was formative, that made you want to write for theater?

ARBERY

When I was a kid, there was this production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard at Shakespeare in the Park in Dallas, where they put the audience backstage. It blew my mind—and it made so much sense dramaturgically. Here were the actors, coming from the stage back to us, giving us this privileged access. It felt very charged and exciting.

INTERVIEWER

What inspired you to write Corsicana?

ARBERY

I have seven sisters. The sister directly above me in the order is Julia, who has Down syndrome. I grew up being this amazing person’s younger brother—and also her protector in certain ways. Whether it was true or not, it was what I took on as a kid: I’m going to look out for Julia. But she was also looking out for me. The dynamic of her reminding me over and over that she’s the older sister was a refrain in my childhood, and is still. I wanted to make a play centering a woman with Down syndrome in a way that wasn’t drawing too much attention to it or making it an issue-play but rather just having her be a part of an ensemble, with her own complicated wants and desires.

At the time, I had just written Heroes, which was a draining and dark experience in a lot of ways. The idea of writing something that at least on its surface was a little bit gentler appealed to me. Then of course, once I’d written a draft, I started wondering, How do I complicate this? The play could be deceptively gentle, but I wanted it to have edge in the way that people have edge. I started with the central idea of, What would it be like if it was just me and Julia on our own? Some things stayed the same—some things about Ginny and Christopher’s dynamic are pretty much exactly as we are—and other things changed. The characters became their own people, not perfectly mapped onto us anymore. Then these two other characters, Justice and Lot, emerged out of some mysterious place. Sometimes if you’re writing something really close to home, it helps to place it a little bit to the side. I went to a residency in an old building on the main street of Corsicana, a town forty minutes south of Dallas, which feels on the cusp of being a ghost town. That felt like a good place for these characters to be talking to me. Then I wrote it over the course of three years.

INTERVIEWER

What does Corsicana, the place, mean to you?

ARBERY

It has a quiet energy. The two things the town is known for are the local fruitcake business and the Netflix documentary CHEER—based on the cheerleading program at Navarro College. My months there had a profound effect on me even though I didn’t get any work done, and I was really hot and lonely and scared of this building and mostly spent my time watching YouTube videos and eating too much Domino’s. I felt a heavy sense of history in that place. I went exploring, and I found these old closets where there were still these weird garbs from societies that met there in the early twentieth century, like the Odd Fellows society. I visited the town cemetery, where there’s a grave that reads simply “Rope Walker”—as I discovered, there was a man who wanted to tightrope walk across town and then fell to his death, but nobody knew who he was or what his name was. History doesn’t feel far away in Corsicana. You just still feel it in the air. I imagined the dinosaurs walking around there.

INTERVIEWER

Heroes of the Fourth Turning was set in a world of intellect. As Teresa says, “I don’t know what the artist does. It doesn’t matter.” What does it mean that in Corsicana, everyone has an artistic passion and fraught relationship to the ways in which their art is revealed or hidden?

ARBERY

In and around Corsicana, I started meeting more of the folk art community in Texas—incredible untrained artists from Texas and nearby states. I got curious about people who were making things that they didn’t know if anyone would ever see. This art is not for sale. It’s not to make you famous. It’s just for the thing itself, which comes out of you and finds a shape. There seemed to be a connection between that mode of making things and Julia and her relationship to music. She has an amazing voice and an incredible love of music. She loves singing for people, but she also gets very shy. Once she asks everyone to stop talking so she can sing, it takes a long time for her to actually start singing because she feels all the eyes on her. And yet I know that when she’s behind closed doors in her room listening to something, she’s dancing like crazy and really letting it all go. I wanted to capture that feeling, which is like when you open a door and glimpse something beautiful, but you know that it’s not really for you, and so you close the door again.

INTERVIEWER

So many of these characters are interested in forming ties through their art: Christopher’s letter, Justice’s book, Lot’s sculptures. Some of them are cagey about it, but it’s not necessarily because they want to be.

ARBERY

Even though I did not design this to be a play with an agenda, it’s a play that’s actively engaged in breaking down certain barriers to access. It’s certainly one of the biggest roles I can recall for a performer with Down syndrome in a theatrical play. There’s a temptation in that kind of work to put all of the meaning in one character, but the more I was writing it, the more I thought about how creativity and collaboration and community form. I was interested in the idea of granting access to people who wouldn’t otherwise have it, and then sort of denying it and feeling that loss by the end of the play. That’s my own subtle way of addressing some of the history around “outsider art”—even that term is viewed by a lot of people as being problematic. I watched a documentary about the artist Bill Traylor, who is similar to the character of Lot. He grew up in obscurity, and then his work was discovered after he was dead. It accrued value and was put on museum walls and began selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars. A lot of his drawings and paintings were just sitting on the top shelf of a closet in his relatives’ house. They were surprised and a bit blindsided to find out, “Oh, actually, this stuff has a lot of value.” There’s something inherently a little bit gross about it. It’s important to me to try not to be a part of that grossness and instead look at the characters as people who make things instead of fetishizing what it is they’re making.

INTERVIEWER

Lot is describing a woman who has come from some fancy literary magazine to investigate his “outsider art.” He says, “Seems to me like she’s collecting people. Like she shows up and takes pictures and writes and then takes it away by the writing. Suddenly it’s not what it is anymore.” That idea that the act of writing can take something away from our experience of the work—that’s a challenge for someone who’s writing a play.

ARBERY

I’ve been testing the idea that language is inherently always a bit of a lie or a compromise. But my girlfriend has a good retort to that: “What about Elon Musk and other people who want to put these chips in our brains to go beyond language because they think language is inconvenient and inefficient, and they want us to leapfrog over that entirely?” I hear that, and I think, No. No. I do love language. A person’s language and the way that they use it is like a fingerprint. Which is another thing Julia taught me growing up: I learned more about writing and dialogue from her than I did anybody else in my life.

INTERVIEWER

Your play has original music in it by composer and musician Joanna Sternberg. In the stage directions, you give that Lot’s song is “impromptu and weird but awesome.” There’s a lot of space there not just for an individual vocabulary but an individual voice and melody.

ARBERY

Joanna writes music that is accomplished but also has a clarity and directness. I love Daniel Johnston, and I haven’t heard something else that went right to my heart like that. Joanna’s been writing the music for these songs and slowly adjusting lyrics. It’s been this beautiful back-and-forth of trying to find these melodies while also letting the songs remain a little bit jagged and raw.

INTERVIEWER

Heroes is clearly a play about the right, and it’s a politically charged play all the way through. I initially thought Corsicana was more about art, as though it’s a hard divide. But there’s so much in it about failed utopias and anarchism, especially in the character Justice. How did your decision to use these ideas in the play come about?

ARBERY

It snuck up on me. Justice just started talking about that one day while I was writing it. Then I had to go back and do research and decide who her favorite communist writer would have been and fill in these surprising little details about her literary and intellectual obsessions. It was a huge breakthrough, because I always suspected that she was this secret glue or motor in the play. It was exciting to be inventing a book that that Justice was writing that I genuinely wanted to read. The play takes Justice’s intellectual pursuit seriously. If we were to look at her through the lens of, What polity is she trying to form throughout the course of this play?, then I think what the play shows the delicate nature of that work, the heartbreak that goes into caring for each other and listening to each other and listening to what people say about what they need and don’t need and want and don’t want.

INTERVIEWER

Justice says the book she’s writing is about “the belief that when a part of the self is given away, is surrendered to the needs of a particular time, in a particular place, then community forms. From the ghosts of the parts of ourselves we’ve given away. A new particular body. Born of our own ghosts. I don’t know. It’s about Texas.” That’s what the book that we can’t read is about.

ARBERY

I’ve said before that every play I write is a ghost story. I’m not entirely sure why that is, but it probably has to do with the fact that if I’m writing a play and sitting with these characters, there’s a good chance I’m feeling haunted by some element of the world of the play. There’s another element, too, which has to do with what it feels like to be the author of a play and know that these words are going to be spoken and embodied by a real person. Just the idea of sitting and deciding what people do and say, and making bad things happen to them or difficult conversations happen—the more real they become, the spookier that feels. Some mysterious thing happens.

INTERVIEWER

They become more mysterious and, at the same time, maybe more true. It makes me think of that Zadie Smith essay “In Defense of Fiction.” The essay starts out being about whether you can represent others in fiction, people whose experiences you haven’t yourself had. She writes that what makes her want to read more of a story is belief—belief, that is, in what has been written. I was thinking that, in theater, belief is both necessary and hard to achieve, because there’s no opting out of the fact that the people in play are real, even though there’s something uncanny about them. They need to haunt you, in a way. You need to believe that they’re having real drama in front of you—fictionally real drama.

ARBERY

For me, when theater is at its best, it’s not that you forget where you are, because you’re in a theater squished up against other people, and they’re coughing and sniffling. You always know that you’re in this room. But you find yourself wondering, How did these people on stage get here? Why are they saying the things that they’re saying? And why am I allowed to witness this? It feels like I shouldn’t be here. There’s this double haunting, where you feel like both the visitor and the visited. They seem so real, and you know that you could just go up and touch them. But there’s a threshold that you’re not willing to cross. It feels like, on a very basic level, a sort of séance. It’s a summoning.

Hannah Gold is a critic and fiction writer living in New York City. Her latest work can be found in Bookforum, The Drift, The Nation, and Gawker.

Performances of Corsicana will begin on June 2 at Playwrights Horizons.

April 27, 2022

Barneys Fantasia

SPP Installation at Barneys, 2017. LICENSED UNDER CC0 1.0.

FLOOR LL

In 1923, Barney Pressman pawned his wife’s engagement ring for five hundred dollars and opened a five-hundred-square-foot clothing store on West Seventeenth Street and Seventh Avenue, in downtown Manhattan, where he sold well-tailored menswear at steep discounts. He hung a sign over the doorway: NO BUNK, NO JUNK, NO IMITATIONS. Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.