Fabrizio Ulivieri's Blog, page 119

September 20, 2018

Not among Italians!

Silvano kept a safe distance from the partisans, who wandered between woods and gullies around Montaione, San Gimignano and Volterra. He did not understand their reasons, their way of thinking. He felt instinctively that their smell was not his own smell. Their skin had different reasons than his.

And those strange, incongruous noms de guerre, detached from any human logic: Sandokan, Ursus, Falco, Caserta, Camoscino, Intrepido, Lampo, Mitra, Tigre, Leone, Condor, Cobra, Orso, Bufalo, il Vendicatore, Potente, Birba, Bistecca, Chicchirichì, Cognach, Emorroidi, Fastidi, Fifa...maybe they had a logic, it had to be a logic in those names, it was undeniable, but still they formed a language that Silvano had difficulty to learn.

He did not completely avoid them. In the woods of Jetta, Casa al Rosso and Cetine, he had often met them, had shared their food, smoked their cigarettes, talked to them but had always felt an unbridgeable distance between his own world and their distant world.

They had asked him many times to join the Resistance but Silvano had just delayed. He had not fought as a soldier for the Royal Army and he did not see why he had to do it right now.

— Listen…why don’t you join us?

— I do not know. I have to decide.

— Are you afraid?

— No.

— So, you're a fascist?

— Do you know any fascist in my family?

— So, what are you waiting for?

— Look ... I defected ... I did not fight for the King. And now I have to hide because the carabinieri are after me. And I do not even know why they want me arrested...I thought the war was over and instead ... it's not my war. I do not see any reason to fight it.

— I see…you are not a compagno...

— What do you mean by "you are not a compagno" ?

— You are not a Communist. You don’t believe in the proletarian dictatorship.

— No, I don’t even know what you mean by that…I think it’s not my case to believe in what everybody pretends to believe ...

— You are a defeatist, that's what you are! ... Don’t you want to free Italy from Germans and fascists?

— Allies will do that, not you.

— But we will help them. And then they will treat us as a victorious country and we will be treated equally.

— You are idiots! That’s what you are. They will give you a good kick in the ass. Here's what England and the Americans will give you all!

One of them pointed a gun at him and maybe he would have fired, if one (perhaps the commander) who was called Guido l’ Ebreo had not bellowed out: "Put that bloody gun away. Not among Italians! "

Published on September 20, 2018 02:58

Not between Italians!

Silvano kept a safe distance from the partisans, that wandered between woods and gullies around Montaione, San Gimignano and Volterra. He did not understand their reasons, their way of thinking. He felt instinctively that their smell was not his own smell. Their skin had different reasons than his.

And those strange, incongruous noms de guerre, detached from any human logic: Sandokan, Ursus, Falco, Caserta, Camoscino, Intrepido, Lampo, Mitra, Tigre, Leone, Condor, Cobra, Orso, Bufalo, il Vendicatore, Potente, Birba, Bistecca, Chicchirichì, Cognach, Emorroidi, Fastidi, Fifa...maybe they had a logic, it had to be a logic in those names, it was undeniable, but still they formed a language that Silvano had difficulty to learn.

He did not completely avoid them. In the woods of Jetta, Casa al Rosso and Cetine, he had often met them, had shared their food, smoked their cigarettes, talked to them but had always felt an unbridgeable distance between his own world and their distant world.

They had asked him many times to join the Resistance but Silvano had just delayed. He had not fought as a soldier for the Royal Army and he did not see why he had to do it right now.

— Listen…why don’t you join us?

— I do not know. I have to decide.

— Are you afraid?

— No.

— So, you're a fascist?

— Do you know any fascist in my family?

— So, what are you waiting for?

— Look ... I defected ... I did not fight for the King. And now I have to hide because the carabinieri are after me. And I do not even know why they want me arrested...I thought the war was over and instead ... it's not my war. I do not see any reason to fight it.

— I see…you are not a compagno...

— What do you mean by "you are not a compagno" ?

— You are not a Communist. You don’t believe in the proletarian dictatorship.

— No, I don’t even know what you mean by that…I think it’s not my case to believe in what everybody pretends to believe ...

— You are a defeatist, that's what you are! ... Don’t you want to free Italy from Germans and fascists?

— Allies will do that, not you.

— But we will help them. And then they will treat us as a victorious country and we will be treated equally.

— You are idiots! That’s what you are. They will give you a good kick in the ass. Here's what England and the Americans will give you all!

One of them pointed a gun at him and maybe he would have fired, if one (perhaps the commander) who was called Guido l’ Ebreo had not bellowed out: "Put that bloody gun away. Not between Italians! "

Published on September 20, 2018 02:58

September 19, 2018

Sei comunista?

Silvano rimase sempre distante dai partigiani, che si aggiravano nei boschi e borri fra Montaione, San Gimignano e Volterra. Non capiva le loro ragioni, il loro modo di pensare. Avvertiva d’istinto che il loro odore non era il proprio odore. La loro pelle aveva ragioni diverse dalla sua.

E poi quei nomi di battaglia strani, incongruenti, avulsi da ogni logica umana: Sandokan, Ursus, Falco, Caserta, Camoscino, Intrepido, Lampo, Mitra, Tigre, Leone, Condor, Cobra, Orso, Bufalo, il Vendicatore, Potente, Birba, Bistecca, Chicchirichì, Cognach, Emorroidi, Fastidi, Fifa...o forse non erano invero privi di logica, la logica vi era ed era innegabile, ma comunque facevano parte di una lingua che Silvano aveva difficoltà a imparare.

Non li evitava completamente. Nei boschi della Jetta, di Casa al Rosso, delle Cetine, li aveva spesso incontrati, Aveva condiviso con loro il loro cibo, aveva fumato con loro, aveva parlato con loro ma sempre aveva accusato la distanza fra il suo e il mondo dei partigiani.

Gli avevano chiesto di unirsi alla Resistenza ma Silvano aveva dilazionato. Non aveva combattuto come soldato del Regio Esercito e non vedeva perché dovesse farlo proprio ora.

— Ma perché non ti unisci a noi?

— Non lo so. Devo decidermi.

— Hai paura?

— No.

— Allora sei fascista?

— Conosci qualcuno fascista nella mia famiglia?

— E allora che aspetti?

— Senti…io ho disertato...non ho combattuto per il Re. Ora devo nascondermi perché i carabinieri mi cercano. E non so neanche perché mi cercano. Mi cercano e basta...Io credevo che la guerra fosse finita e invece...non è la mia guerra. Non vedo un motivo per combatterla.

— Ma come, non sei un compagno?

— Che vuol dire “non sei un compagno”?

— Non sei comunista?

— No, mi pare una moda...

— Sei un disfattista, ecco quello che sei...non vuole liberare l’Italia dai tedeschi e dai fascisti?

— L’Italia la libereranno gli alleati, non voi.

— Ma noi li aiuteremo. E dopo ci tratteranno da paese vincitore e potremo trattare il futuro della nazione alla pari.

— Voi siete solo degli illusi. Ecco quello che siete. Vi daranno un bel calcio nel culo. Ecco quello che vi darà l’Inghilterra e gli americani!

Per questo erano quasi venuti alle mani. Uno di loro gli aveva puntato una pistola e forse avrebbe anche sparato, se uno (forse il capobanda) che chiamavano Guido l’Ebreo non avesse urlato “Metti via quella pistola. Fra italiani no!”

Published on September 19, 2018 04:42

September 18, 2018

The language of honor

At ninety-four, Silvano was only trying to resist. To force the body to do what it could no longer do and the mind consequently had difficulty keeping up with the will. Sabatina was confined to a wheelchair. She barely could walk and hardly. She was too fat. So many times he had told her she had to lose weight.

— Me fat? I only have a swollen stomach - she answered. She did not see herself fat. Quite the contrary.

In that old-age-fog that enveloped his brain (high blood pressure, prostate, varicose veins, medicines in large amounts) he tried to find his way. To reorganize his vision that he felt close to be extinguished.

He understood that if he switched off that vision he would lose contact with the rest of the world. It was the last link between him and the outside world, that vision which desperately he grabbed. And the past years he had fought to keep it alive.

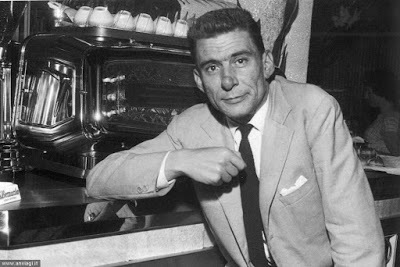

Until the collapse of Bettino Craxi had been a lion. A fighter, a beast. He never gave up. He could fall asleep at midnight and wake up at four in the morning every day. He worked for the Socialist party and he commuted every day (Rome – Florence) to save on the daily allowance that the party gave him.

When the PSI collapsed, he realized that he too had come to the end. After Craxi fall he wouldn’t raise again, ever. He understood that the party he dedicated his life to was bound to disappear forever, that all those who would come after Craxi would be nothing but names, adjustments to delay an agony that could not be delayed. The end had been decided long before the end.

That day was another 8 September, for Silvano, the same day that Italy died. The First Republic was dying. And the Second was certainly not better. If the First was an icon of Italy yet, still Italy for Italians, the Second was nothing but a nightmare, the fear of becoming another Mexico.

And then came the Third and most devastating Republic: the juntas of Monti, Renzi and the PD. A governance under the Brussels bureaucrats whose goal was to suffocate identities, to impose the dominion of finance, to destroy societies through a new weapon called mass migration.

After months of complete discouragement, of hoping in a return of Craxi from Hammamet where he had taken refuge to avoid arrest, an escape allegedly with help from the same judge who was prosecuting Bettino, Silvano realized he was feeling a loss of that vision which until then had guided him.

He was conscious that if he had lost the ability to visualize the direction he would have broken the oath made to himself on the very day Rocco had left him at Firenze Santa Maria Novella on September 11, 1943.

Rocco had spoken the language of honour. What other language could he have used? He who refused to surrender and fought for the Decima Mas and Junio Valerio Borghese despite of the collapse of the Kingdom of Italy, the Fascism and the dissolution of the Italian Royal Army.

Published on September 18, 2018 19:30

September 17, 2018

How to get around the inadequacy of an outdated language

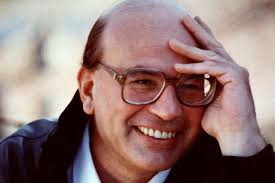

Beppe Fenoglio

Beppe FenoglioThis is the second time that I find myself in front of an unexpected situation, which goes under the name of "language", i.e. the lack of an adequate language to describe the past.

The first time was when I was planning to write a novel about the Unification of Italy. Now that I plan to write a novel starting from September 8th, 1943, to nowadays, I feel this difficulty once again.

It is obvious that if you want to write something about the years of war and those immediately after you must read those authors who have (de)scribed that period, but every time you try to read them you fall into linguistic and cultural stereotypes that have formed that Italy, from the post-war period onwards. You experience the unbridgeable distance between today's language and post-war language.

Challenging, aggressive, modern, experimenting the language you use to describe the current reality, monotonous, old, cumbersome, stereotypical, boring themes the language used by post-war writers.

I could say the same things for the contents. Dead, ineffective, almost invalids, those highlighted by writers like Cassola, Fenoglio, Vittorini, but still, to be honest, stronger than those expressed by contemporary literature-meme - which may seem a contradiction but it is not, in how neorealism has however a greater impact of contents than neo-post-realist writers watered down by the prevailing globalism).

The solution I have adopted is then to keep in the book a narrative voice that describes the past from the present, starting from the present versus the past. a Voice able to throw a cone of light, to illuminate the past realities, directly from the present to the past, from a present universe in which the revision takes place, towards the past universes on which revision is operating.

In this way I will be able to filter the past with a modern language, with a modern structure, without depending on past models.

Published on September 17, 2018 02:30

September 14, 2018

La lingua dell'onore

A novantaquattro anni Silvano cercava solo di resistere. Di forzare il fisico a fare quello che non poteva più fare e la mente di conseguenza aveva difficoltà a stare al passo della volontà. Sabatina era confinata ad una sedia a rotelle. Camminava poco e a malapena. Era troppo grassa. Tante volte glielo aveva detto che doveva dimagrire.

— Io grassa? Ho solo lo stomaco gonfio — rispondeva. Lei non si vedeva grassa. Tutt’altro.

In quella nebbia di vecchiaia che gli avvolgeva il cervello (pressione alta, prostata, vene varricose, medicine in quantità industriale) cercava di trovare la strada. Di riorganizzare la sua visione che sentiva spengersi.

Aveva capito che se si spengeva quella visione avrebbe perso contatto con il resto del mondo. Era l’ultimo legame fra lui e il mondo fuori, quella visione. E aveva lottato negli ultimi anni per mantenerla.

Fino al crollo di Craxi era stato un leone. Un cavallo da battaglia, una bestia. Uno che non mollava mai. Che tornava da Roma la notte a mezzanotte e alle quattro del mattino si alzava per andare alla stazione e riprendere il treno per ritornare a Roma, solo per risparmiare sulla diaria che gli dava il partito.

Quando crollò il PSI, capì che era arrivato alla fine anche lui. Che finito Craxi sarebbe finito anche il suo lavoro, che il partito per cui aveva lottato e dato la vita non ci sarebbe stato più, che tutti quelli che sarebbero venuti dopo non sarebbero stati che nomi, aggiustamenti per ritardare una fine che non poteva essere ritardata ancora. La fine era stata decisa molto prima della fine.

Quel giorno per Silvano fu un altro 8 settembre, un giorno in cui l’Italia di nuovo morí. Morì infatti la Prima Repubblica. E la Seconda non fu certo meglio. Se nella Prima era ancora l’Italia degli Italiani, nella Seconda vi era di tutto. Nella Seconda si profilava l’incubo di fare la fine del Messico.

E poi arrivò la terza Repubblica quella più devastante, quella di Monti, Renzi e del PD. Quella dei burocrati di Bruxelles sordi a ogni voce dei popoli di Europa, la Bruxelles delle banche, dell’immigrazione di massa.

Dopo mesi di completo scoramento, di speranza in un riscatto di Craxi da Hammamet dove si era rifugiato per evitare l’arresto, una fuga concordata con la magistratura in realtà, avvertí la perdita della visione che fino ad allora l’aveva sempre guidato.

Si avvide che se avesse perso la capacità di visualizzare la direzione avrebbe cozzato contro quel giuramento fatto a se stesso il giorno che Rocco lo lasciò sotto la stazione di Firenze, l’11 settembre 1943.

Rocco aveva parlato una sola lingua. Quella dell’onore. Che altra lingua avrebbe potuto parlare uno cha ancora si ostinava a combattere con la Decima Mas di Junio Valerio Borghese? Nonostante il crollo del Regno d’Italia, del fascismo e della dissoluzione del Regio Esercito d’ Italia.

Published on September 14, 2018 08:14

Come aggirare l'inadeguatezza di un linguaggio inattuale.

Elio Vittorini

Elio VittoriniÈ già la seconda volta che mi trovo a cospetto di una situazione inattesa: il linguaggio. La mancanza di un linguaggio adeguato per descrivere il passato.

Una prima volta è stato quando avevo in mente di scrivere un romanzo sull'unità dell'Italia. Ora di nuovo che ho in mente di scrivere un romanzo dall'8 settembre ai nostri giorni, avverto questa difficoltà ancora una volta.

È ovvio che se vuoi scrivere qualcosa sugli anni della guerra e quelli immediatamente dopo devi leggerti quegli autori che hanno (de)scritto (su) quel periodo, ma tutte le volte che provi a leggerli cade negli stereotipi linguistici e culturali che hanno formato l'Italia dal dopoguerra in poi. Avverti la distanza incolmabile fra il linguaggio odierno e quello del dopoguerra.

Sfidante, aggressivo, moderno, sperimentante quello che usi per descrivere temi attuali, monotono, vecchio, ingombrante, stereotipico, noioso.

Potrei dire le stesse cose per i contenuti. Morti, ineffettivi, invalidi quasi, quelli messi in luce da scrittori come Cassola, Fenoglio, Vittorini (ma comunque, ad onor del vero, più forti di quelli espressi dalla letteratura-meme contemporanea - che può sembrare una contraddizione ma non lo è, in quanto i neorealisti hanno comunque un maggior impatto di contenuti dei ne-post-realisti annacquati dal globalismo imperante) - eccitanti, dilanianti per l'attualità quelli di chi sa produrre oggi temi contrastanti il globalismo generato dal capitalismo predatorio e il burocratismo finanziario di Bruxelles e le loro consequenti menzogne di parte.

La soluzione che ho adottato è allora di tenere nel libro una voce narrativa che descrive dal presente il passato, partendo dal presente versus il passato. Capace di gettare un cono di luce, in grado di illuminare le realtà trascorse, direttamente dal presente sul passato, da un universo presente in cui prende luogo la revisione, verso gli universi passati su cui si attua la revisione.

In questo modo potrò filtrare il passato con un linguaggio attuale, con un impianto moderno, senza dipendere dai modelli passati.

Published on September 14, 2018 02:44

September 11, 2018

Secret services and the Italian publishing world

Manipulation.

Media manipulation currently shapes everything you read.

Great powers (finance, intelligence, politics, States ...) influence economy and social structure of states beyond any doubt. Italy is probably the best example. From the Unification until today Italy is a constant experiment of conflict and manipulation of foreign states (England, USA, Germany, France ...) and every time this land tried his own way the politician who tried it was taken down (Mattei, Moro, Craxi).

Given the disappointing literary panorama, marked by a kind of literature devoid of originality (especially of contents), which I define literature-meme, i.e. able only to repeat without innovating, suitable to produce frames without contents *. Therefore if I consider the premises I started from from I naturally ask myself how those who are capable to influence the media are also interested in controlling the editorial world (an authentic inaccessible bunker, which admits and promotes only the names certified by a type of literary vision appreciated by those who generally manipulate the world of information and entertainment.

The neorealist vision of Italian literature.

I again ask myself: why every time a film or an Italian book is successful abroad (with a few exceptions), does it only convey to the whole world that kind of stereotypical image of Italy? A poor country, more or less co-belligerent or even a defeated nation, or in the hands of mafia, but always firmly anchored to the so-called "allies": USA or England.

Debate.

For the time being, however, I do not have any elements to fully support this thesis but obviously I like to confirm that at the base of editorial choices must be a trend that has been imposed, and which continues to prevail. Otherwise I would not explain the editorial myopia that extends itself no more than the limits of the above mentioned bunker that has set itself the limits and terms of its very survival.

Of course, there is also independent publishers, but their economic power, distribution and marketing skills are so minimal that publishing with independent publishing leads an author to remain not only a complete stranger but also they are at risk of losing money .

I would therefore like to open a debate, so that we can identify concrete and evident cases of manipulation or at least of dominant ideological paradigm .

Some cases (Alvaro, Bassani, Lussu ...to stay within the limits of a few names) are mentioned as collaborators of the UK secret services by Giovanni Fasanella and Mario Cereghino in their book "Colonia Italia". In this book is well exemplified how UK secret services strongly interfered with manipulation of Italian culture and public opinion.

* Obviously the fact that the frame becomes dominant with respect to contents is certainly not due (or not only due) to a direct intervention of external/foreign influences but, certainly, to the dominant culture imposed by search engines and social media that have constituted a culture where the collective dominates the individual, providing contents (feeds) already pre-established by/in the network via algorithm to the detriment of individual creativity.

Individual content (creativity and innovation) tends to decrease to zero.

Published on September 11, 2018 02:41

September 9, 2018

Servizi segreti e editoria italiana

Manipolazione.

Che esista la manipolazione dei media è fuor di dubbio.

Che esistano poteri forti (finanza, servizi segreti, politica, Stati...) che influenzano l'economia e la struttura sociale degli Stati è altrettanto evidente. L'Italia ne è il miglior esempio. Dall'Unificazione ad oggi l'Italia è terra di scontro e di manipolazione di Stati stranieri (Inghilterra, USA, Germania, Francia...) e ogni volta che ha tentato una strada in proprio chi ha provato è stato fatto fuori (Mattei, Moro, Craxi).

Visto il deludente panorama letterario, caratterizzato da un tipo di letteratura priva di originalità (soprattutto di contenuto), che io definisco letteratura-meme, cioè capace solo di ripetere senza innovare, idonea a produrre solo frames senza contents*, e considerate le premesse da cui sono partito, mi viene naturale chiedermi quanto chi influenzi i media in generale abbia anche interesse a tenere sotto controllo un mondo editoriale , bunker, che ammetta e promuova solo i nomi certificati da un tipo di visione letteraria gradita a chi manipola in generale il mondo dell'informazione e dello spettacolo.

La visione neorealista della letteratura italiana.

Possibile mi chiedo che ogni volta che un film o un libro italiano ha successo all'estero (con poche eccezioni) non fa che veicolare al mondo intero quel tipo immagine stereotipica dell'Italia? Un paese povero, più o meno cobelligerante o anche sconfitto, in mano alla mafia, ma sempre saldamente ancorato ai cosiddetti "alleati": USA o Inghilterra.

Dibattito.

Al momento non ho elementi per cui avvalorare in toto questa tesi ma ovviamente non posso che confermarmi nel dubbio che alla base delle scelte editoriali vi sia un trend che è stato imposto, e che continua a imporsi. Altrimenti non mi spiegherei la miopia editoriale che vive non più in là dei limiti del bunker che si è imposta per sopravvivere.

Ovviamente esiste anche l'editoria indipendente, ma le capacità economiche, di distribuzione e di marketing sono così minime che pubblicare con l'editoria indipendente porta un autore a rimanere non solo un perfetto sconosciuto ma anche a rischiare di rimetterci economicamente.

Vorrei perciò aprire un dibattito, per cui si riesca a individuare casi concreti ed evidenti di manipolazione dell'editoria.

Alcuni casi (Alvaro, Bassani, Lussu...), per limitarsi ad alcuni nomi, vengono citati come collaboratori dei servizi segreti da Giovanni Fasanella e Mario Cereghino nel loro libro Colonia Italia. In questo libro è messo bene in luce il forte condizionamento operato dai servizi segreti dell'Inghilterra nella formazione della cultura e dell'opinione pubblica italiana.

* Ovviamente il fatto che il frame divenga dominante rispetto al content non è certo dovuto (o non solo dovuto) a un intervento diretto di influenze ester(n)e ma anche, certamente, alla cultura dominante imposta dai motori di ricerca e social media che hanno costituito una cultura dove il collettivo domina sull'individuo, fornendogli (feed) contenuti già precostituiti dalla/nella rete via algoritmo a scapito della sua creatività individuale.

Il contenuto individuale (creativo e innovativo) tende all'azzeramento.

Published on September 09, 2018 03:43

September 7, 2018

Ištraukos iš "Amore, šaltibarščiai ir raudoni pomidorai" — Pabaiga

(Iš italų kalbos vertė Margarita Gaubytė)

Aš praeinu savo skausmą ir ilgesį,

Neregio žingsniais skaičiuoju tave.

Tavo tolimą kelią, o, meile, vienintele,

Tyliai praeisiu ir būsiu šalia.

(„Myliu“, Romo Dambrausko daina)

Sėdėjau virtuvėje prie stalo, žiūrėjau lietuvišką televizijos laidą „Auksinis protas“, kurioje atsakinėjo į bendruosius kultūros klausimus, – geras būdas mokytis kalbos. Tai padėjo man suprasti lietuvių kalbą ir išmokti naujų žodžių.

Lauke buvo tamsu, snigo kaip svajonių mieste. Austėja ruošė valgį. Vėl atėjus žiemai, ji pagamino šaltibarščius su virtais kiaušiniais. Atskirai supjaustė raudonų pomidorų. Paprastai šaltibarščiai patiekiami su virtomis bulvėmis, tačiau ji negalėjo be savo gyvybiškai svarbaus maisto. Artėjo Kalėdos, lauke buvo sniego ir spaudė poliarinis šaltis. Manau, kad siekė −35 °C. Buvau sakęs jai, kad žiemą norėčiau paragauti šaltibarščių su kiaušiniais. Man reikėjo energijos – šaltis, sporto klubas, seksas su Austėja beveik kasdien...

Pastebėjau, kad jau keletą dienų Austėja nevalgo saldumynų, negeria kavos ir net vyno. Tačiau niekada neapsieidavo be raudonų pomidorų. Kitą rytą pusryčiams ji pasidarė sumuštinį su kalakutienos servelatu – rūkyta kalakutiena, kuri forma primena salamino, jį kaitaliodavo su mortadella – uždėjo agurkų ir raudonų pomidorų. Pietūs, ką ji bevalgytų, visada būdavo su raudonais pomidorais. Vakarienei vėl raudoni pomidorai.

Ji prisiartino prie manęs rankose laikydama lėkštes ir padėjo jas ant stalo. Rūpestingai išsirinko raudonų pomidorų gabaliuką ir įsidėjo jį į burną, elegantiškai, tarsi būtų nusiteikusi bendrauti.Tada ištarė:

- Netrukus atvyks Marco.

- Marco?

Aš pagalvoju apie Marco, savo wing fight trenerį Italijoje, kuris buvo ne tik treneris, bet ir gyvenimo mokytojas. Vienas iš mano labiausiai gerbiamų žmonių Italijoje.

Prisimenu, kartą jam pasakiau:

- Žinai, Marco, galvojau wing fight, istorinis futbolas... vienuolika metų žaidei istorinį florentietišką futbolą, dabar visam gyvenimui esi diskvalifikuotas, tik vieni raumenys, statinė be smegenų, bet va, atradau Mokytoją. Man kalbi apie kūną, jo simetriją, kinų mediciną, energiją, duodi patarimų, kaip elgtis su žmonėmis. Nustebinai, Marco, tikrai mane nustebinai. Iš tavęs išmokau ne tik wing fight – išmokau gyvenimo.

Austėja gerai žinojo, kad labai gerbiu Marco. Aš jį vertinu.

- Pasirinkau šį vardą, nes žinau, kaip tą žmogų gerbi.

- Apie ką kalbi, Austėja?

- Aš nėščia, laukiame mažylio Marco.

Iš lėkštės ji paėmė dar vieną raudoną pomidorą (pomidorai sveika širdžiai, virškinimui, akims, laisvina vidurius, veikia prieš vėžį, mažina cholesterolį, kovoja su osteoporoze... tinkama pradėti naują gyvenimą...), įsidėjo į burną ir dar labiau nusišypsojo man.

Pažvelgiau Austėjai į akis. Nežinojau, ką galvoti. Ar buvau laimingas?

Man žemė pradėjo slysti iš po kojų. Taip, buvau labai laimingas.

Published on September 07, 2018 07:14