Angela Grey's Blog

October 29, 2025

The Real Magic Is Survival: Reimagining Girlhood Through Myth

There is a kind of myth that begins not with a goddess or a monster, but with a girl—ordinary, fragile, luminous in her unknowing. She doesn’t lift a sword or command the seas. Her weapon is quieter: endurance. Her myth begins the moment she decides to live.

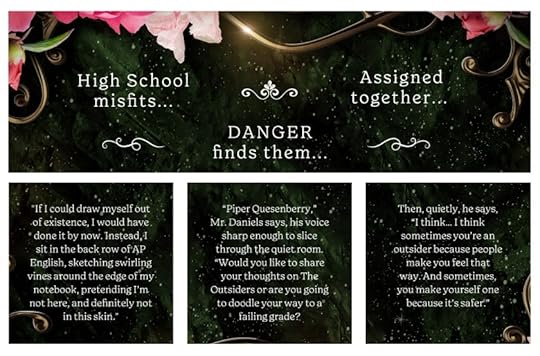

In my novels—Some Species of Outsider-ness, Whimsy and Bliss, Dreamcatcher, The Cartography of First Love, The Shadows We Carry, and Dancing Without Music—I return again and again to this quieter mythology of survival. These are stories where mental illness, trauma, and identity fracture are not narrative detours but sacred terrains. Where girls and boys on the edge of unraveling become the new myth-makers—reclaiming the right to define themselves, to choose love in the face of despair, to say: I am still here.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3727" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:292px;height:auto" />Photo by Ozgur Camurlu on Pexels.comGirlhood as Mythic TerrainFor too long, the myths told about girls—especially those living with mental illness—have been either tragic or ornamental. They are Ophelia, drowned; Persephone, abducted; the muse, never the maker. But the modern myth I want to tell is not one of passivity. It’s about the interior odyssey: what it means to fight through panic and self-doubt, through disordered thoughts and despair, and to still reach toward connection.

In Some Species of Outsider-ness, Piper and Slater—two teens navigating bullying, chronic illness, and a dark web of secrets—are outsiders not because they are weak, but because they see too much. Their sensitivity is not a flaw; it’s a kind of second sight. In a world obsessed with belonging, they learn that empathy can be both their wound and their weapon. Their survival is the magic.

Whimsy and Bliss reimagines the coming-of-age myth as a map of thin places—the unseen seams between childhood wonder and adult loss. Abigail Whimsy, ever the dreamer, and Lainey Bliss, her pragmatic counterpart, move through a lakeside summer like two halves of the same soul, searching for the portals where wonder still seeps through. It’s less about escaping reality than about expanding it—about realizing that the magic we’re looking for was always inside the friendship itself. Girlhood, here, is its own mythic realm: ordinary and holy, bruised and glittering.

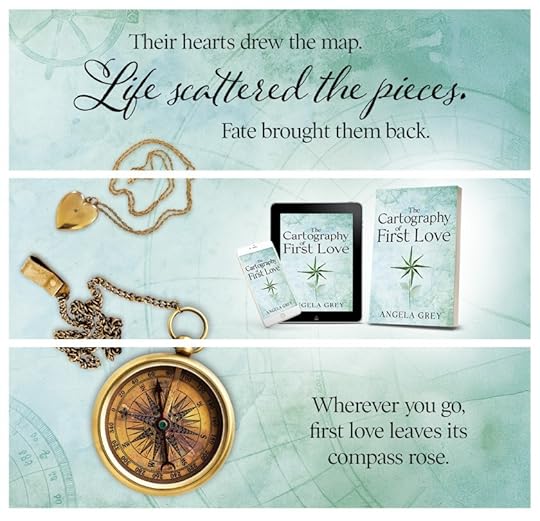

Mental Illness as Modern MythTo write about mental illness is to write about thresholds. Between the seen and unseen. Between the mind that betrays and the mind that longs to heal. In The Cartography of First Love, Zibby and Nico meet inside a psychiatric unit—a place both sterile and sacred. Their story isn’t about illness as spectacle, but about love as witness. Within those six weeks, they trace the coordinates of first love across therapy rooms, greenhouses, and whispered library exchanges.

There’s a map inside both of them, drawn in scars and tenderness. The miracle isn’t that they find each other—it’s that they find themselves. Years later, when they meet again by chance, the question isn’t whether love survives time, but whether healing does. The myth of recovery is rarely linear. It spirals, it falters, it returns. It asks us to keep choosing life, even when it hurts.

Mia and Milo, the central pair in Dancing Without Music, echo this theme in a rawer, more dangerous register. Two teens falling in love while their worlds are falling apart: Mia fighting an eating disorder, Milo hiding seizures and depression. Their story—threaded with bullying, trauma, addiction—pulls from the real language of survival. These aren’t heroes in shining armor. They’re kids clawing their way toward light through the rubble of social media cruelty, systemic failure, and internal chaos.

Their resilience is not romanticized. It’s messy, imperfect, human. Love doesn’t save them—but it steadies them long enough to seek help, to speak truth, to begin the slow choreography of recovery. The real dance, as the title suggests, happens in silence—in the small, defiant act of staying alive when everything tells you not to.

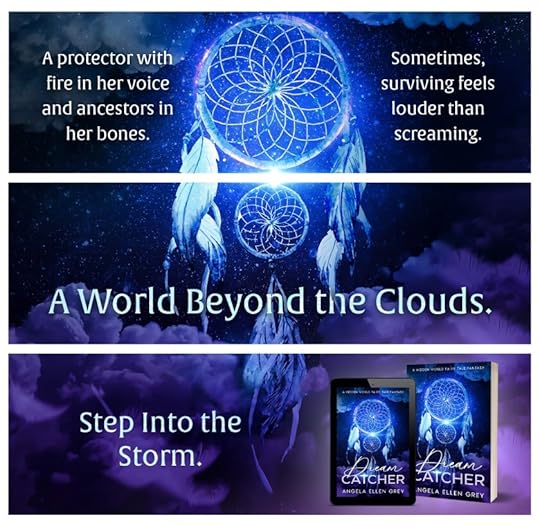

Dream as Ancestral HealingIf Dancing Without Music is rooted in realism, Dreamcatcher drifts through the luminous realm of allegory. Here, girlhood is not only psychological terrain but spiritual inheritance. Dash, a Dakota Sioux girl grieving her parents’ mysterious deaths, touches a dreamcatcher in her window and falls through clouds into Baumwelt—a world woven from collective memory and ancestral wisdom.

In Baumwelt, survival takes the form of mythic questing: dragons, shapeshifters, and lands that mirror trauma back as a test. But beneath its fantasy lies the same heartbeat as every other book I’ve written—the belief that facing one’s fears, honoring one’s lineage, and listening to the quiet voice within can heal what the world tries to silence. Dash learns that courage isn’t the absence of fear but the decision to keep walking through it.

In this way, Dreamcatcher becomes an Indigenous-inflected myth of reclamation: the sacred task of remembering who you are when the world forgets. The land itself participates in her recovery. It’s not an escape from pain—it’s a return to belonging.

The Inheritance of ShadowsThe Shadows We Carry extends that mythic inheritance into adolescence and womanhood, where mental illness and memory intertwine. This novel asks: What do we carry that isn’t ours? Which stories, silences, and stigmas do we inherit from generations past?

The protagonist’s journey through grief and genetic mental illness becomes a reckoning with family ghosts—literal and figurative. The book suggests that recovery is never solitary. It’s ancestral, collective. Healing ripples backward as well as forward. When one girl chooses therapy, medication, art, or simply another sunrise, she’s rewriting the myth for everyone who came before her.

Survival as Sacred ArtAcross these novels, I see a pattern—a constellation of wounded but luminous characters turning their pain into passage. Whether through art (Some Species of Outsider-ness), friendship (Whimsy and Bliss), heritage (Dreamcatcher), love (The Cartography of First Love), or sheer endurance (Dancing Without Music), they transform suffering into story. To survive, they create. To create, they must survive. The loop is sacred.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3736" style="width:230px;height:auto" />Photo by Mohammed Alim on Pexels.comIn this sense, writing these books has always felt like both ritual and rebellion. Each story emerged during my own seasons of anxiety, loss, or recovery. Each one asked me to reimagine girlhood not as something fragile but as something feral and enduring—a myth of resilience hidden inside every nervous system, every heartbeat, every moment we choose to stay.

When Mia and Milo hold each other after the worst night of their lives, it’s not a fairytale ending. It’s a beginning. When Zibby and Nico meet again after a decade apart, it’s not closure—it’s continuation. When Dash stands at the edge of the dreamworld, deciding whether to return, it’s not escape—it’s integration. Survival, after all, isn’t static. It’s art in motion.

Toward a New MythologyWhat would it mean to tell girls—not just in books but in life—that their feelings are not too much, their minds not too broken, their stories not too dark? That inside every panic attack, every relapse, every sleepless night, there’s still a pulse of mythic power saying go on?

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3738" style="aspect-ratio:1.51005580315344;width:324px;height:auto" />Photo by Frank Cone on Pexels.comThe old myths taught us that magic was external: fire, lightning, divine intervention. The new myths—those of mental health and recovery—teach us that magic is endurance, empathy, and the quiet work of staying.

In the end, the real magic is survival.

It’s the girl who keeps painting when her hands shake.

It’s the boy who takes his meds and still writes poems.

It’s the friendship that outlasts grief.

It’s the love that doesn’t cure you but holds you steady until you can begin to heal yourself. That, to me, is the truest myth—the one we’re all still writing.

The Language of Survival: On Mental Illness, Resilience, and First Love

I’ve always believed that the most courageous stories are not about rescue, but about return—how we come back to ourselves after the mind has turned against us. When I write about mental illness, I don’t write from a distance. I write from the thin edge of it—from the quiet hours where thought unravels and the only lifeline is language. Each of my novels—Secret Whispers, Déjà Vu, and Of Laughter & Heartbreak—was born out of that liminal space between fear and faith, between survival and surrender.

These books aren’t companions by chronology, but by spirit. Each follows a young woman whose inner world threatens to eclipse the outer one, and each discovers that love—whether romantic, platonic, or self-forged—is the most powerful form of recovery we have.

1. The Mind as Haunted House: Secret Whispers

1. The Mind as Haunted House: Secret WhispersWhen I wrote Secret Whispers, I began with an image: a house stitched together by secrets, its silence louder than any scream. Inside it lives Adria—a painter, sister, caretaker, and reluctant witness to her own unraveling.

Schizophrenia shadows her family line, coiling like a whispered curse. Her brother’s breakdown has already split the household in half. Her mother holds everything together with brittle faith. And Adria, caught between caretaking and collapse, begins to hear the same whispers that once took him away.

I wanted to write honestly about what it means to live with a mind you can’t fully trust—the terror of not knowing whether what you see is symptom or sight. But I also wanted to write about love: the improbable, incandescent kind that dares to root itself in fractured soil.

In Secret Whispers, love doesn’t save Adria. It steadies her. The boy who sees her—awkward, hopeful, honest—doesn’t fix her illness; he becomes a mirror in which she can see more than diagnosis. Their love flickers like a candle in a draft, fragile yet real, proof that connection is possible even when perception splinters.

Adria’s resilience isn’t loud. It’s made of small gestures: washing a brush, opening a window, whispering not today when the shadows come. Recovery, I learned while writing her, is not a staircase but a spiral—you circle the same fears until you finally face them without flinching.

2. Déjà Vu: The Loops of the Bipolar Mind

2. Déjà Vu: The Loops of the Bipolar MindIf Secret Whispers was about hearing too much, Déjà Vu was about feeling too much—about living inside a mind where memory and mania blur.

Ivy Lancaster is eighteen, brilliant, impulsive, and newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She experiences life in echoes: every stranger’s face feels familiar, every nightmare seems rehearsed, every choice loops back like a record caught on its scratch.

The first time I wrote Ivy walking through the parking lot at dawn, barefoot and disoriented, I felt the pulse of the entire novel—this young woman spinning in the orbit of her own brain, terrified of herself yet desperate to be believed.

Déjà Vu is not just a psychological thriller; it’s an emotional x-ray of bipolarity. Mania is painted not as glamour but as velocity—the thrill that burns. Depression is written not as stillness but as suffocation. Yet in between, there’s the quiet miracle of awareness.

And there is love. Love arrives in Ivy’s world not as romance, but as recognition: people who refuse to define her by her disorder, who remind her that she exists beyond chemical imbalance. Love, in this book, is accountability—the friend who says take your meds, the parent who whispers you are more than your mind, the stranger who looks her in the eye when she feels invisible.

Resilience here is not recovery in the clinical sense. It’s survival as rebellion. It’s Ivy saying, I may live inside loops, but I can still choose where to step next.

When readers tell me Déjà Vu helped them feel seen—that it mirrored their manic spirals or the hollow aftermath—I’m reminded why I write these stories. To dismantle stigma. To remind us that living with mental illness is not a flaw in character, but a feat of endurance.

3. Of Laughter & Heartbreak: OCD and the Art of Staying

3. Of Laughter & Heartbreak: OCD and the Art of StayingBy the time I wrote Of Laughter & Heartbreak, I wanted to explore a different texture of the mind: the obsessive, ritualized patterns of control that masquerade as safety.

Stevie Matthews is almost sixteen. Her thoughts arrive like barbed wire; her rituals multiply like vines. When the summer’s order collapses, she’s hospitalized—a space she never asked for, but where, for the first time, she meets others who understand the language of compulsion.

OCD, for Stevie, is both prison and prayer. Her rituals aren’t about superstition; they’re about trying to keep the world from shattering. I wrote her story as both confession and communion—a letter to anyone who’s ever mistaken coping for control.

Behind those locked doors, Stevie meets her mirror selves: the anxious boy who collects facts like talismans, the quiet girl who hides notes to her future self, the nurse who knows that healing isn’t linear. Together they build something like family—a map stitched from shared fragments of hope.

This novel, like the others, carries the pulse of first love—not in grand gestures, but in small acts of belief. The hand that steadies hers during a panic spiral. The smile that says you are not too much. The love that grows not in spite of illness, but within it. Because love, at its truest, doesn’t demand wholeness—it meets you in the fragments and stays.

4. The Quiet Revolution of SurvivalEach of these novels began with illness, but each ends with something larger: a reclamation of humanity.

In Secret Whispers, Adria learns that her art can hold what her mind cannot.

In Déjà Vu, Ivy redefines truth beyond the lens of mania.

In Of Laughter & Heartbreak, Stevie learns that control is not safety, and surrender is not defeat.

Together, they form a kind of triptych about resilience—the quiet kind that never makes headlines. They remind me that mental illness and first love often share the same vocabulary: vulnerability, risk, surrender, trust. Both require standing on the edge of the unknown and saying yes anyway.

To live with a brain that misfires is to live constantly between worlds—the real and the imagined, the lucid and the lost. Yet within that space, there’s beauty. There’s empathy. There’s art.

These are not stories about being cured. They’re stories about being human.

5. Why I Keep WritingSometimes readers ask why I return, again and again, to characters who struggle with their minds. My answer is simple: because I know what it means to stay.

Because the world still whispers that mental illness is weakness.

Because the stories that saved me were the ones that refused to flinch.

Because the young readers who see themselves in Adria, Ivy, and Stevie deserve to know they are not broken—they are becoming.

Writing these books has taught me that resilience isn’t the absence of relapse; it’s the decision to keep loving life anyway. It’s the courage to reach for connection even when your hands shake. It’s the soft defiance of building hope out of symptoms.

And maybe, at the center of it all, it’s first love—the thing that reminds us we’re still capable of wonder.

When I look back on Secret Whispers, Déjà Vu, and Of Laughter & Heartbreak, I see not a trilogy of illness, but a mosaic of endurance. Each girl walks through her own labyrinth and emerges carrying the same small flame: belief.

Belief that we are more than diagnosis.

Belief that love is still possible in the dark.

Belief that the quiet work of staying—of waking up again, and again—is itself a form of grace.

If these stories have a single message, it’s this:

Even when the mind fractures, the heart remembers how to reach for light.

Letters Never Sent: The Language of Almost-Love

There are some stories that never make it into envelopes. They live instead in the folds of memory—creased, re-read, and worn thin by time. They’re the letters we write but never send, the words that hover just behind the heart, waiting for a quiet room to finally be heard.

When I think about my first love, I think about the hum of hospital machines, the antiseptic air that tried and failed to scrub out tenderness, and the boy named Timothy who sat across from me in a hospital dayroom in Bismarck, North Dakota, when I was fifteen years old. We met in a place where silence was its own kind of language. There were no dances, no declarations, only the small exchanges that happen when two people recognize in each other a kind of ache they can’t yet name.

Timothy had eyes the color of bright blue mornings. I remember that more than I remember his laugh. I remember the way we traded drawings on napkins, folded them like notes. I remember the way time slowed when we spoke, how the air seemed to listen. It wasn’t the kind of love that blooms; it was the kind that lingers—half-formed, half-forbidden, the kind that teaches you that connection doesn’t always need duration to matter. That’s what I’ve come to call almost-love: the love that teaches you what the real thing feels like, even if it never lasts.

1. Cartography of the Heart

1. Cartography of the HeartWhen I wrote The Cartography of First Love, I didn’t know I was writing about Timothy until the story was finished. I thought I was writing about two fictional teens—Zibby and Nico—who meet in an adolescent psych unit and build a map of first love through sketches, letters, and whispered promises. But every line of that book carries a trace of that hospital dayroom in Bismarck—the smell of coffee, the soft buzz of fluorescent light, the way we used humor like a flashlight against fear. The way we bonded with each other and the other teens on the ward. The dreams we had of escaping our broken lives, along with another teen couple, to a dream life in California.

Zibby’s eating disorder, Nico’s depression—those were fictions, but the emotional terrain was real. Both of them were trying to survive themselves, and somehow, in doing so, they found each other. That’s what Timothy and I were doing too: surviving. Learning how to be human in a place built to monitor it.

There’s something profoundly sacred about the love that forms between the broken. It doesn’t need polish or promise; it exists simply because both hearts recognize that the other is still beating. When Zibby says, “I don’t know if this is forever, but it feels like oxygen,” I was really writing what I never said to Timothy. I never told him how, in that sterile, rule-bound space, he made the world feel possible again. That his presence was proof that tenderness can exist even in places designed to contain it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3696" style="aspect-ratio:1.7045022194039314;width:364px;height:auto" />Photo by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels.com2. The Letters We Don’t SendI’ve always believed that letters are a kind of spell—language meant not just to reach someone else, but to reveal the self. When I was fifteen, I started writing letters I never mailed. To therapists. To friends. To Timothy. They weren’t love letters in the romantic sense; they were survival letters. I wrote them to remember what feeling felt like. To tether myself to something human.

Years later, when I began The Cartography of First Love, I found those letters again—folded, smudged, and still breathing. I didn’t copy them verbatim, but their spirit is in every page. Letters, after all, are time machines. They preserve the version of us that dared to speak, even when no one was listening.

Maybe that’s what almost-love does—it leaves us with letters, not outcomes. It gives us language we can’t unlearn.

3. Whimsy’s Map of Wonder

3. Whimsy’s Map of WonderIn Whimsy and Bliss, I returned to the idea of unsent letters, though in a different form. Abigail Whimsy, the dreamer, writes postcards she never mails—notes to her best friend Lainey Bliss, to her late grandmother, to the lake itself. She believes that words can travel through time if you believe hard enough. Whimsy’s letters aren’t addressed to a boy; they’re addressed to memory, to childhood, to the version of herself that still believes in magic. But they, too, are love letters of a kind. Letters to what’s been lost.

The older I get, the more I understand that love doesn’t always need a recipient. Sometimes it’s enough to write it down, to set it loose like a paper boat and trust the current to carry it where it needs to go.

Timothy never saw my letters, but I think, in some cosmic way, he received them. Maybe they reached him through dream or distance or the invisible threads that connect first loves across decades.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3702" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:324px;height:auto" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com4. The Language of AlmostAlmost-love has its own dialect. It speaks in half-sentences, in glances, in small pauses before parting. It’s the love that never makes it to the altar but still shapes your sense of faith. It’s the song that stops mid-melody but leaves the tune in your head for years.

When I write about first love, I’m not writing about romance so much as recognition—the sacred shock of being seen. Zibby and Nico’s map in The Cartography of First Love isn’t geographic; it’s emotional. It charts the spaces between fear and desire, between what’s spoken and what’s withheld. It’s the same map I’ve been unconsciously drawing since fifteen—the topography of tenderness interrupted. In that way, Timothy is the first coordinate on all my maps. Every love that came after carries his imprint, faint but indelible.

5. What We KeepI never saw Timothy again after that spring in Bismarck. We left the hospital on different days, back to different towns, different futures. I remember watching a late-spring snow swallow the parking lot as I waited for my mother’s car. I thought of how, in the snow, everything looks erased but is only hidden.

That’s how almost-love survives—not by continuation, but by concealment. It hides inside the art we make, the stories we tell, the way we hold someone’s name gently in the mind decades later.

When I look back now, I don’t feel regret. I feel gratitude. For the way that brief connection taught me how to pay attention. How to see the soul beneath the symptom. How to believe that love, in any form, is never wasted.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3704" style="aspect-ratio:0.718473244355744;width:318px;height:auto" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com6. The Cartography of ClosureEvery writer has an origin story. Mine began in that hospital, where letters I couldn’t send became stories I eventually did.

The Cartography of First Love was, in many ways, my way of finally mailing them. Each page was an envelope addressed to the past. Each chapter a way of saying: I remember. I made it. I’m still here.

In Whimsy and Bliss, that same message echoes through Abigail’s summer adventure—her yearning to finish her grandmother’s “map of thin places,” where wonder seeps through the world. It’s the same impulse: to locate the sacred in the ordinary, to find beauty even in what’s unfinished.

Because that’s what almost-love is—it’s unfinished beauty. It’s a comma instead of a period. And yet, sometimes, the sentence feels complete anyway.

7. To Timothy, Across TimeIf I could write one more letter now, it would be simple:

Dear Timothy,

We were just kids. But for a moment, the world stood still. You showed me that connection doesn’t need perfection—it only needs presence. I don’t know where you are now, but a part of me still sends light your way whenever I write a story about first love. Thank you for being the first mapmaker of my heart.

Maybe he’ll never read it. Maybe he’s long forgotten that spring. But the point isn’t whether the letter arrives—it’s that it was written. Because writing, like loving, is an act of faith. We send the words out anyway.

When readers tell me The Cartography of First Love or Whimsy and Bliss reminded them of someone they once loved and lost, I smile. That’s the quiet miracle of almost-love—it continues. Not in the way we expect, but in the way stories and letters do: across time, across silence, between worlds.

The language of almost-love is the language of becoming. It teaches us that some doors never close; they simply turn into windows through which light still enters. And if you listen closely enough—under the hum of memory, under the rhythm of your own pulse—you can still hear it:

The letter, written in the dreaming heart, whispering—I was here. You were too. That was enough.

Thresholds Between Worlds: Writing the Dreaming Mind

There are nights when the mind becomes a borderland—not waking, not sleeping, but something tender and trembling between. That’s where my stories live. When I write, I’m less interested in plot than in passage—the subtle moment when reality begins to shimmer and something unseen breathes through. It’s the hum before a dream takes shape, the hush in a library where imagination crosses the threshold.

My novels Dreamcatcher, Ink & Ivy, and Whimsy and Bliss were each born from that in-between space: where dream logic and daylight ache overlap, where imagination is both refuge and revelation. I’ve come to think of them not as separate stories, but as three rooms in the same house—the House of the Dreaming Mind.

1. The Doorway in the Dark

1. The Doorway in the DarkThe idea for Dreamcatcher began with an image: a girl climbing through a fire-escape window, brushing against her grandmother’s dreamcatcher, and falling into another world. For Dash, my protagonist, the dream realm of Baumwelt is not a fantasy world in the traditional sense—it’s a reflection of her inner life. Every creature she meets, every landscape she crosses, echoes her memories, fears, and ancestral lineage. The world outside her window dissolves, but what replaces it is not pure invention—it’s memory rearranged by sleep.

Dreams are the language of the unconscious, but they are also archives of ancestry. In Dakota tradition, dreams carry instruction; they are bridges to spirit, not mere illusion. Writing Dreamcatcher, I wanted to honor that worldview—to let dream be teacher, not escape.

The dreaming mind, after all, has its own geography. It’s where past and present fold into each other, where the living and the dead keep company. Dash’s journey through Baumwelt is really a journey into inheritance—into how memory, myth, and trauma shape the self. When she wakes, nothing around her has changed, but she has. That’s what every good story does—it sends you somewhere so that you can return with new eyes.

2. Ink as Spellwork

2. Ink as SpellworkIf Dreamcatcher is the dream entered through sleep, Ink & Ivy is the dream entered through creation. Marisol, the girl who runs a hidden bookshop, learns that the stories she writes can alter reality. What she pens becomes what she lives; language itself becomes a portal. But her gift carries risk: every act of creation has a cost. Words can heal, but they can also harm.

In that sense, Ink & Ivy is about authorship as alchemy—the idea that writing is both spell and surrender. As writers, we are always crossing thresholds between imagined and real. We live half in the world and half in language. The line between the two blurs until even we can’t tell which is which. When Marisol writes, she’s not escaping grief; she’s giving it shape. The ink becomes her ritual of remembrance.

Writing, too, is a dream you enter deliberately. When I’m deep in it, time dissolves, sound thickens, and the body becomes peripheral. That liminal state—the creative trance—is the same consciousness that dreams speak from. It’s what poets call flow and mystics call vision. I’ve come to believe that all art is a form of lucid dreaming: we are awake, but we allow the dream to guide our hand.

3. Between Wonder and Loss

3. Between Wonder and LossThen there is Whimsy and Bliss—a story set not in another world, but in the precise moment before girlhood fades into adulthood. Abigail Whimsy is the dreamer; Lainey Bliss is the realist. Together, they chase “thin places,” secret corners of their lakeside town where the fabric between worlds wears thin. Their summer map becomes a pilgrimage of goodbye—to childhood, to friendship, to the certainty that magic is only for the young.

In Whimsy and Bliss, the dreaming mind is not only nocturnal—it’s emotional. The dream here is nostalgia: the ache for what can’t be returned to, the shimmering almost-memory of who we were. When Whimsy and Bliss explore abandoned libraries and climb water towers under moonlight, they’re searching for wonder before it vanishes. They are practicing a kind of everyday mysticism—the belief that the ordinary world is already enchanted, if only we pay attention.

This, to me, is the heart of the dreaming mind: it notices what others overlook. It lives in metaphor, in symbol, in atmosphere. It insists that even grief has its own radiance.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3681" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:404px;height:auto" />Photo by Kaique Rocha on Pexels.com4. Dream as Bridge, Not EscapePeople sometimes ask why I write “fantasy.” I never quite know how to answer, because my worlds are not so much invented as revealed. Fantasy, for me, is not an exit door—it’s an entrance. Dreaming and writing share a purpose: they make the invisible visible. They bridge what logic can’t. When I write about portals, I don’t mean only magical doors. I mean threshold moments: the second before grief hits, the silence after someone says I love you, the pause between inhale and exhale. These are the real portals, the moments where transformation begins.

The dreaming mind knows this. It’s always translating feeling into image: a locked door becomes fear; a rising tide becomes memory; a missing key becomes forgiveness waiting to happen.

In Dreamcatcher, Baumwelt is Dash’s subconscious given form. In Ink & Ivy, imagination becomes tangible, able to wound or heal. In Whimsy and Bliss, dream takes the shape of longing. Each story moves through a different register of the same truth: that what we imagine is not separate from who we are.

Fantasy still matters because it reminds us that the world is layered. Beneath the surface of the ordinary lies a pulse of mystery, waiting to be remembered.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3673" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:308px;height:auto" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.com5. The Craft of CrossingWriting the dreaming mind requires a particular discipline of attention. It’s not about inventing strange worlds, but about listening for what already hums beneath language.

I’ve learned to approach each story like a lucid dreamer: half-awake, observant, unafraid. When a sentence feels too rational, I let it unravel. When logic tries to take over, I ask what image might speak instead.

A novel like Dreamcatcher grows through atmosphere before plot; it must be dreamed onto the page. Ink & Ivy demands reverence for language itself—every word carries spell-weight. Whimsy and Bliss thrives on emotional resonance—the threshold between childhood and adulthood is its own kind of magic realism.

To write the dreaming mind, one must accept unknowing. The story reveals itself only as you move through it, like a dream that solidifies upon waking. You can’t outline it entirely; you can only walk with it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3683" style="width:280px;height:auto" />Photo by Mo Eid on Pexels.com6. Waking GentlyWhat I love most about dream-based writing is how it teaches you to wake differently. When you step out of a story like Dreamcatcher or Ink & Ivy, you don’t just return to life—you return to it changed. Readers often tell me they see their own dreams differently after finishing these books. That is the greatest compliment I could receive. It means the stories have done their work: not to distract, but to awaken.

The dreaming mind is not a place we visit only at night. It’s a consciousness we carry—a sensitivity to meaning, pattern, and possibility. It’s the part of us that still believes rivers can whisper, that trees remember, that words are alive.

Writing through that lens keeps me tethered to awe. And awe, I think, is a form of prayer.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3671" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:320px;height:auto" />Photo by Tara Winstead on Pexels.com7. The Threshold ItselfI return often to that fire-escape window from Dreamcatcher. The girl climbing through it. The touch of feathers, the shift of air. The dreamcatcher trembling like a heartbeat.

That moment—between step and fall, between real and imagined—is the space I write from. It’s the threshold itself that matters, not what lies on either side.

Because the dreaming mind isn’t about choosing one world over another. It’s about learning to live in both at once. To walk through daylight with a trace of starlight still on your skin. To carry the dream with you, awake.

Every story I’ve written is, in its own way, a map back to that place.

Dreamcatcher taught me to honor ancestral dream as truth.

Ink & Ivy taught me that language is alive.

Whimsy and Bliss taught me that growing up doesn’t mean losing wonder.

All three remind me that imagination is not an indulgence—it’s a responsibility.

The dreaming mind keeps us human. It holds the world together, one dream, one story, one word at a time.

The Quiet Work of Staying: Healing in Fragments

Before I learned how to write, I learned how to stay. Not the cinematic kind of staying—the triumphant recovery arc, the sudden sunrise after years of darkness—but the quiet, ordinary kind. The kind that happens in fragments: brushing your teeth after days of forgetting due to deep depression, answering one text message, writing a single word. The kind of staying that doesn’t look heroic, but is.

For a long time, I thought healing would feel like a song. Now I know it’s more like static—broken, uneven, but still carrying sound.

Both The Alphabet of Almosts and Some Species of Outsider-ness were born from that static—from the ache of trying to make coherence out of chaos, from the question that threads through all mental-health narratives: how do you keep living when the story doesn’t make sense anymore?

1. Fragments as Language

1. Fragments as LanguageWhen I began writing The Alphabet of Almosts, I didn’t set out to create a story about illness. I set out to alphabetize survival—to give shape to the words that hovered between diagnosis and hope.

The book unfolds through small vignettes, each one a lettered fragment—A for Admission, B for Breakthrough, C for Control—and together they build something resembling a life. I was living in that in-between place: between recovery and relapse, clarity and confusion. Each fragment became a way of saying, I’m still here, even if I can’t say it all at once.

There’s something deeply honest about fragments. They don’t pretend to be whole. They allow contradiction, misstep, mess. They remind us that language, like healing, doesn’t have to be linear to be true.

For me, fragmentary writing became both mirror and medicine. When the mind fractures, linearity can feel dishonest. The world arrives in flashes—images, memories, unfinished thoughts. Writing in fragments wasn’t an aesthetic choice; it was survival. It was how I could stay.

2. The Work of StayingStaying is not glamorous. It doesn’t get book deals or film adaptations. It doesn’t even feel like progress most days. Staying is brushing your hair. It’s making a list you may never finish. It’s finding small reasons not to disappear.

In Some Species of Outsider-ness, I wanted to explore that kind of endurance through two characters—Piper and Slater—whose internal battles are as invisible as they are immense. Piper lives with bipolar disorder, Slater with the lingering paralysis of Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Both are marked by difference in a world that worships sameness.

Their story begins not with love, but with survival: two teens learning that belonging doesn’t mean being fixed, but being seen. The novel’s title comes from the idea that being an outsider is not a condition to be cured—it’s a species to be studied, honored, understood.

The quiet work of staying runs through both their lives. For Piper, it’s managing the cycle of mania and depression without letting either define her. For Slater, it’s learning to move again—physically, emotionally, relationally—after trauma. Neither of them is “better” by the end. But they are still here. And sometimes that’s enough.

Staying is not stagnation; it’s an act of devotion. It’s choosing to keep breathing even when the air feels heavy. It’s sitting in your own skin, even when it doesn’t feel like home.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3660" style="aspect-ratio:1.4980494148244474;width:425px;height:auto" />Photo by AS Photography on Pexels.com3. Healing in FragmentsThe culture of wellness often sells us a singular image of healing: bright mornings, clear journaling pages, the triumphant “after.” But true healing—especially after mental illness, grief, or trauma—is far less symmetrical.

Healing happens in fragments. In partial sentences. In moments you forget to count as progress: the laugh you didn’t expect, the walk you took without dread, the meal you actually tasted.

In The Alphabet of Almosts, the narrator describes healing as “collecting the scattered glass of myself and learning not to bleed every time I touch it.” I think of that often. Healing is not about gluing the shards back together into what once was; it’s about learning to live among them, to see beauty even in the breakage.

The Japanese art of kintsugi—mending broken pottery with gold—has become almost cliché in self-help spaces, but there’s a reason it endures. It acknowledges fracture as part of the story. The break becomes the illumination.

That’s what I wanted for Some Species of Outsider-ness too: a kind of emotional kintsugi, where characters mend not by erasing their scars but by tracing them in gold.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3659" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:150px;height:auto" />Photo by Ann H on Pexels.com4. The Myth of WholenessWholeness is overrated. I don’t mean that cynically. I mean that wholeness, as it’s often sold to us, is a myth that keeps us ashamed of our incompleteness. It suggests there’s an endpoint to becoming human. But what if our task isn’t to be whole, but to be honest?

Fragments allow for honesty. They let contradiction breathe. You can be healing and hurting, hopeful and hopeless, all at once. You can love your life and still want to leave it some days. You can laugh and cry within the same minute, and both are true.

When readers tell me they saw themselves in The Alphabet of Almosts, it’s rarely because they relate to every word. It’s because they recognized a single line that felt like their own breath. That’s the gift of fragmentation—it leaves room for others to enter.

And maybe that’s what healing really is: not the restoration of self, but the reconnection to others. To community. To language. To the small rituals that keep us tethered to the living.

5. What the Outsiders Teach Us

5. What the Outsiders Teach UsThe title Some Species of Outsider-ness came to me during a sleepless night. I was thinking about how often we label difference as deficiency. How quick the world is to exile those whose rhythms don’t match its pace.

But outsiders—those who live at the edge of ordinary—often see what others cannot. They notice the fissures, the unspoken rules, the small violences of normalcy. They remind us that empathy is not a theory but a practice.

Piper and Slater’s story is, in a sense, a love letter to outsiders: to those who feel too much, too loud, too strange. It’s also a call to stay—to resist disappearance. Their survival is not cinematic. It’s quiet. But quiet doesn’t mean small.

The quiet work of staying is the foundation of every great act of love. Because staying—whether in a body, a relationship, or the world itself—requires belief in something beyond the immediate pain. It’s faith in tomorrow’s breath.

6. The Shape of HopeBoth books taught me that hope doesn’t always look like light. Sometimes it looks like a shadow. Sometimes it’s the pause between two heartbeats, the whisper between words. Hope, for me, is found in the act of making: writing, painting, collaging. In taking fragments and saying, You still matter. In creating beauty that refuses to be perfect.

When I wrote The Alphabet of Almosts, I kept a note above my desk that said, Stay in the room. That was my whole goal—not to write a masterpiece, not to heal overnight, but simply to stay. To stay long enough to turn a feeling into a line, a line into a page, a page into something that could keep another person company in their own darkness.

Art doesn’t fix us. It doesn’t erase pain. But it translates it. It gives it a place to rest. It lets others know they’re not alone in the fragments.

7. The Quiet EndingWhen people ask me what The Alphabet of Almosts is “about,” I tell them it’s about learning to live inside unfinished sentences. When they ask about Some Species of Outsider-ness, I say it’s about the kind of courage that doesn’t get applause—the courage to stay.

Healing will never be tidy. It will never be final. But maybe that’s its beauty. Maybe the work of being alive is to keep stitching the fragments together, one breath at a time. There’s a line near the end of The Alphabet of Almosts that still feels like a compass to me:

“Maybe we don’t need to be whole. Maybe we just need to stay long enough to see what else becomes possible.”

Fantasy has its dragons. Romance has its declarations. But healing—real, quiet, ordinary healing—has this: the act of staying. So if you find yourself in pieces, remember this: every fragment is proof that you have not disappeared. You are still here. You are still writing. And that, too, is a kind of wholeness.

Portals Made of Language: Why Fantasy Still Matters

Before I ever believed in magic, I believed in words. Not the easy kind—abracadabra, or once upon a time—but the harder ones that carried grief and wonder in equal measure. The kind of words that didn’t promise escape, but understanding. Fantasy, for me, has never been about running away from reality; it has always been about walking toward it through a different door.

That door is language itself. Every metaphor is a threshold, every poem a small, shimmering key. And if you listen closely enough—between syllables, between breaths—you’ll hear the hinge creak open.

1. The Work of Wonder

1. The Work of WonderWhen I began writing Dreamcatcher, I wasn’t trying to build another world. I was trying to make sense of the one I already lived in—the one that didn’t always make space for silence, for Indigenous belief, for the shimmer between dream and waking. Baumwelt, the world my protagonist Dash steps into through her grandmother’s dreamcatcher, grew from the ache of that absence.

In the beginning, I thought Baumwelt was a fantasy realm. But the longer I wrote, the more I realized: it was a reflection. Every root in that world grew from real soil—the Dakota stories, the wind through Minnesota pines, the ache of losing and finding yourself again.

Fantasy has a way of returning us to what’s most real. It asks us to look at our world through the mirror of the impossible, and in doing so, to see what we’ve overlooked. When Dash touches the dreamcatcher and slips between worlds, she isn’t escaping. She’s being invited to look deeper—to face the dark, to understand grief as something that can be walked through, not avoided.

Fantasy matters because it teaches us the work of wonder: that curiosity is not naiveté, and awe is not ignorance. It is an act of radical attention.

2. Language as Portal

2. Language as PortalIn Ink & Ivy, language becomes a literal form of creation. Marisol, a young lady who runs a magical bookshop, discovers that what she writes can change the world around her. Her stories don’t just describe—they summon. But with every word comes responsibility; every metaphor has consequences.

This, too, is the work of writers: to understand that words are not harmless. They shape what we see. They summon possibility—or erase it.

In Ink & Ivy, the girls’ language becomes a living thing, something that resists control. The “pale man,” a figure who feeds on imitation and distortion, thrives on empty words—stories written without care, without truth. The girls learn that creation, to be sacred, must be done with reverence.

Fantasy, at its best, reminds us of the power of language. We speak worlds into being. We dream communities into possibility. We write our own maps through darkness. The portal isn’t the wardrobe or the dreamcatcher or the bookshop door. It’s the sentence itself—the turning of one word into another.

3. The Sacred OrdinaryMany people think fantasy is escapist because it contains dragons, spells, or portals. But what if those things are simply metaphors for what already lives within us? The dragon, in Dreamcatcher, isn’t just a beast—it’s fear, grief, the inheritance of pain. When Dash confronts it, she’s really confronting the trauma of generations, the unspoken stories that haunt her family.

And when Marisol in Ink & Ivy writes her way through grief, her pen becomes both wand and weapon—an instrument of creation that heals by revealing.

Fantasy is the literature of the sacred ordinary. It allows us to approach heavy truths with the gentleness of myth. It helps us say what cannot otherwise be said.

I think of Indigenous storytelling—how coyote and wind, willow and raven are not just symbols, but relatives. Fantasy, in its truest sense, carries that same heartbeat: it teaches us that the world is alive, responsive, and holy in its strangeness.

When readers step into Dreamcatcher or Ink & Ivy, I don’t want them to find an escape hatch. I want them to find a mirror. I want them to feel what it means to hold grief and beauty in the same breath, to remember that imagination is not a luxury—it’s an inheritance.

4. Why We Still Need FantasyIn an age of data and disconnection, we need stories that remind us what it feels like to be human. Fantasy does that. It re-enchants the world. The modern world is noisy with explanation. We want everything to be understood, categorized, proven. But what if the point of wonder is not to be solved, but to be stayed with? Fantasy slows us down. It asks us to listen. It gives us permission to imagine again—a radical act in a culture of cynicism.

When I visit workshops, I often tell young writers that fantasy is not an escape from truth; it’s a different route to it. The language of magic lets us speak about mental illness, loss, and love in ways realism sometimes can’t. A dragon can hold more honesty than a diary entry. A spell can say what a scream cannot.

In Dreamcatcher, the dream world exists because Dash’s waking life is too painful to face directly. In Ink & Ivy, the written world becomes a refuge from grief—but also a reminder that creation without integrity can destroy as easily as it heals. Both stories are, at their heart, about the power of imagination to rebuild us.

We still need fantasy because the world is still breaking—and fantasy shows us how to mend.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3642" style="aspect-ratio:1.7769942706037902;width:452px;height:auto" />Photo by Yusuf P on Pexels.com5. The Door Within the ReaderEvery time a reader opens a book, they cross a threshold. They leave behind their certainty and step into language. That act—quiet, solitary, miraculous—is the closest thing we have to magic. When I write, I try to make that doorway visible. Sometimes it’s a dreamcatcher. Sometimes it’s a bookshop in a forgotten town. But always, it’s a passage between the seen and the unseen, the possible and the impossible.

Fantasy matters because it reminds us that those borders are permeable. It whispers that the ordinary world is threaded with portals if only we know how to look. And maybe that’s the point—not to lose ourselves in the unreal, but to find our way back to the real with our eyes open wider, our hearts more attuned to wonder.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3646" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:286px;height:auto" />Photo by Athena Sandrini on Pexels.com6. Closing the CircleIn Dreamcatcher, Dash returns home after her journey through Baumwelt, carrying both loss and wisdom. In Ink & Ivy, Marisol learns that creation is not about control—it’s about connection. Both stories close with the same truth: that every world we build through language eventually leads us back to ourselves.

When I walk along the lake near my home in Minnesota, I often think about the way water mirrors sky—the way two worlds touch without truly merging. That thin line of reflection is where my stories live: the between-place where reality brushes against dream. Fantasy still matters because it keeps that shimmer alive.

In the end, every book is a portal. Every reader, a traveler. Every word, a small act of faith that the invisible still matters—that imagination, like water, can still cleanse, connect, and carry us home.

October 26, 2025

When Fiction Heals the Dreamer: Writing Trauma as Art

There’s a quiet moment that comes after finishing a dark book—that first deep inhale, the feeling that the air has changed somehow. That’s what writing Long Since Buried felt like for me. I’d exhaled years of unspoken fear, and when the final chapter ended, the silence that followed wasn’t emptiness. It was relief.

But the story didn’t stop on the page. Healing never does.

What I learned in therapy—and later through mindfulness—is that creative survival isn’t about mastering pain; it’s about making room for it to transform. Long Since Buried gave the nightmare form. Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful taught me how to live beyond it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3618" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:270px;height:auto" />Photo by Engin Akyurt on Pexels.comThe Two Languages of Survival

In therapy, I discovered that trauma speaks two dialects: chaos and control. Fiction became my translation of chaos—the wild, cinematic projection of buried emotion. Mindfulness became my translation of control—the patient return to breath, to the present, to what is still possible.

Writing Long Since Buried was visceral. It bled from dreamscapes and flashbacks, the body remembering danger. Every paragraph was an adrenaline pulse, an echo of that twelve-year-old’s terror.

Writing Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful was slower—a reclamation of quiet. It was learning to listen to the world again, one heartbeat at a time. While the thriller roared, the memoir whispered. Both, however, were love letters to survival written in different tongues.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3611" style="aspect-ratio:1.502851392150285;width:318px;height:auto" />Photo by Atlantic Ambience on Pexels.comThe Mind–Body Bridge

Trauma divides us—the mind races ahead while the body stays trapped in old danger. Through therapy I learned how narrative and mindfulness work together to build a bridge back to wholeness.

Fiction let me remember safely. I could approach the pain through story, where characters held the fear for me. Mindfulness let me return safely. It anchored me to the now, reminding me that the threat was past.

I began to see that the very act of creating—forming sentences, describing light, naming sensation—was neurological repair. The brain’s storytelling instinct and the body’s breathing instinct are twin healers. Together they weave coherence from chaos.

When readers tell me Long Since Buried feels immersive, I know it’s because I wrote it with my entire nervous system. When they tell me Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful feels calming, it’s because I wrote it with the same system finally at rest.

Writing the Body Back Home

During therapy, my clinician once said, “The body keeps score, but it also keeps rhythm.” That sentence changed how I wrote. I started noticing rhythm everywhere—the pattern of my steps, the cadence of my sentences, the rise and fall of my breath.

In Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful, I intentionally explored this rhythm. The prose mirrors the inhale–exhale cycle: tension, release; grief, gratitude. It’s structured mindfulness, disguised as narrative.

In Long Since Buried, rhythm became heartbeat and gunshot—the percussive language of suspense that mirrors trauma’s pacing: freeze, run, breathe. The thriller was the storm; the mindfulness memoir was the still water after.

Together, they compose a symphony of the same theme: how the body returns to itself after being lost in fear.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3628" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:330px;height:auto" />Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.comWhy the Dark Still Matters

People sometimes ask why I continue to explore the dark—murder, secrets, obsession—after publishing a book devoted to calm and healing. I think it’s because darkness isn’t the opposite of peace; it’s the doorway to it.

Writing thrillers like Long Since Buried allows me to enter that darkness on my own terms. The fear that once hunted me now waits on the page, obedient to craft. Through fiction, I can orchestrate the chaos that once consumed me. Through mindfulness, I can sit beside it without flinching.

The two practices are not opposites—they are partners. One dives deep into the abyss; the other teaches how to resurface without drowning.

The Craft of Compassion

When I teach or speak about writing through trauma, I remind others that craft and compassion are inseparable. Good storytelling isn’t about dramatizing suffering; it’s about humanizing it. The line between a scene of violence and a scene of healing is empathy—for the characters, for the reader, for yourself.

While revising Long Since Buried, I played with quiet moments amid tension—the smell of coffee in a sheriff’s office, the tremor of a hand brushing against a windowpane—small reminders that even in fear, life insists on beauty.

In Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful, compassion showed up differently: as permission to rest, to not perform recovery as productivity. I wrote those pages with gentleness, the way you might speak to a frightened animal—softly, patiently, without sudden movement.

Both books required the same heartbeat of grace: You survived. Now, what will you make from the pieces?

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3630" style="aspect-ratio:1.7769942706037902;width:352px;height:auto" />Photo by Frank Cone on Pexels.comCreativity as Continuum

Looking back, I can trace a clear lineage between the two works—between the hunted girl of Long Since Buried and the healing woman of Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful.

One wrote from the wound.The other wrote from the scar.Together they tell a larger truth: healing is not an endpoint but a continuum of creation. We write the pain to understand it, and we write the peace to remember it.

If Long Since Buried was the exorcism, Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful was the benediction.

A Note to the Dreamers

If you’ve ever woken from a nightmare that feels too real, or carried a story inside you that no one believes—this is for you. You are not alone in the dark. The act of writing, painting, singing, or simply breathing through it is a radical declaration: I am still here.

Fiction may not heal the wound, but it can build a bridge to the part of you that wants to. Mindfulness may not erase memory, but it teaches you to hold it gently, without letting it consume you. Every story we tell from a place of survival becomes a lighthouse for someone still lost at sea. That’s why we keep creating. Not because we’ve conquered the dark—but because we’ve learned to live with its light inside us.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3622" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:302px;height:auto" />Photo by George Milton on Pexels.comIn Closing, A Reflection…

When I look at my bookshelf now, I see not just titles but testaments. Long Since Buried stands as the girl’s scream turned into structure. Bedridden & Gutted to Mindful stands as the woman’s whisper turned into prayer.

Between them runs a thread of ink, breath, and bravery—proof that stories born of pain can become the architecture of peace.

And perhaps that’s the most honest definition of healing I know:

Not erasing the nightmare,

But rewriting it until it learns how to dream.

October 25, 2025

Writing the Nightmare: How Long Since Buried Became My Way Back to Light

When I was twelve, I began dreaming of being hunted.

It wasn’t the kind of nightmare that dissolves with morning light. These dreams followed me—in hallways, in car rides, in the spaces between waking and sleep. In them, I was always running. Sometimes, I saw who chased me; in others, there were only the shadows gathering at the edges, the sound of breath too close behind.

Therapists would later call it trauma’s echo, the body remembering what the mind couldn’t articulate. But at the time, I just called it fear. It clung to my ribs for decades, shapeshifting—into insomnia, perfectionism, silence. When I finally began therapy as an adult, my sessions became less about remembering events and more about re-entering the emotional rooms I’d locked shut. Those rooms were crowded with ghosts, but also with stories waiting to be told.

That’s where Long Since Buried was born—not as a thriller at first, but as a reckoning.

The Fiction That Remembered Me

The Fiction That Remembered MeI didn’t sit down to write a murder mystery. I sat down to write about a feeling I couldn’t escape—the sense of being watched, pursued, never quite safe in my own skin.

In Long Since Buried, twelve-year-old Sydney dies during what should have been an ordinary spring day in South Dakota. Thirty years later, her newly discovered twin, Laci, returns to the same town to unravel what happened. Two women, two timelines—one silenced, one searching.

When I began, I didn’t realize how closely those sisters mirrored the split inside me. Sydney became the self that never got to speak, the child frozen in that recurring nightmare. Laci became the adult voice, trying to rewrite what the dream refused to release.

I remember writing late into the night, hands trembling, feeling the same chill I had as a child. The words felt like digging—not for a plot twist, but for buried truth. I didn’t outline the story. It unfolded the way memory does—fragmented, looping, unreliable. Each chapter was a séance, calling forth pieces of the past I’d long since buried under survival instinct.

When Therapy Meets the PageOver the years, therapy taught me how to sit with the body’s reactions—the quickened pulse, the tightening throat—without letting them drown me. Writing taught me how to translate those sensations into language. Between the two, I found a strange kind of balance: psychology as scaffold, story as sanctuary.

The sessions and the drafts often overlapped. One week, I’d describe the recurring dream to my therapist—the smell of dirt and spent ammo with its sulfurous, metallic odor, the sound of footsteps, the desperate wish to turn and face what chased me. The next week, I’d find that same image emerging in the manuscript—but this time, under my control. I could decide what happened when I turned around.

That was yet another time I realized that fiction could be a survival tool—not a means of escape, but a way to return to the site of the wound with agency. In writing, I was both hunted and hunter, both lost girl and adult author mapping the terrain of her own memory.

In this way, Long Since Buried became an act of reclamation disguised as suspense.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3590" style="aspect-ratio:0.6630815531106616;width:252px;height:auto" />Photo by morgana pozzi on Pexels.comThe Town as MirrorThe fictionalized setting—Watertown, South Dakota—is more than a backdrop. It’s a possible mirror of containment and repression. On the surface, it’s idyllic: lakeside weddings, small-town gossip, the scent of lilacs after rain. But underneath, everyone knows something they won’t say out loud. Everyone carries their own secret version of the truth.

That, too, came from life. The unspoken rules of small communities. The polite silences that can hide harm. The way a family can appear whole from the outside while cracking beneath the weight of what’s unsaid.

When I described the town, I was also describing the psychological landscape of trauma—beautiful, familiar, and haunted. The serenity of the lake juxtaposed against the violence beneath its reflection. The wedding festivities standing as fragile rituals of denial.

Readers often tell me the book feels cinematic—as if the town itself were breathing. I think that’s because every building, every echo, every whispered conversation was built from memory’s architecture.

The Child Who Was HuntedDuring therapy, I realized that the nightmares of being hunted were never about literal pursuit. They were metaphors for the feeling of being unsafe in my own story. The faceless hunter was every force—societal, familial, internal—that told me to stay small, quiet, compliant.

When I wrote Sydney, I gave that hunted girl a name, a world, and eventually, a voice that transcended death. Her chapters are written from the past, but they hum with an afterlife’s awareness. Through her, I could finally face the forest—not as prey, but as witness.

The process wasn’t easy. Writing Long Since Buried often meant reliving the old panic. I’d have to step away, breathe, ground myself in the present—feeling my feet, naming five blue things in the room. But each time I returned to the keyboard, I felt a little stronger. The page became a threshold: on one side, fear; on the other, creation.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3593" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:212px;height:auto" />Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.comThe Adult Who ReturnsLaci’s sections—the modern-day timeline—are my love letter to persistence. She’s not fearless; she’s relentless. Her investigation isn’t just about uncovering who killed her twin. It’s about confronting the emotional debris that lingers when truth has been buried too long.

Writing her reminded me that healing is never about erasing what happened; it’s about learning to carry it differently.

I gave Laci my own instincts—her tendency to overanalyze, her compulsion to observe, her need to understand why. I also gave her what I wish I’d had sooner: a sense of permission to look, even when others warned her not to.

Through her, I could finally answer the question the nightmare always posed: What happens if I stop running?

The Silence After the GunshotThere’s a moment in the first draft—quiet, almost imperceptible—where time seems to stop. A gunshot echoes. The scene goes still. My first readers describe it as eerie, cinematic. For me, it was cathartic.

That silence after the shot became symbolic: the stillness that follows a trauma before the mind rushes to fill in the blanks. In that pause, the reader and I share the same breath—both of us listening for what comes next.

And what comes next, in fiction and in life, is always the same: choice. Do we remain buried in the narrative others wrote for us, or do we dig our way toward our own version of truth?

Writing as ResurrectionI used to think writing about pain would make it permanent. But I’ve learned it can do the opposite. When we give shape to what haunts us, we reclaim it. We define it before it defines us.

In that way, Long Since Buried became both elegy and resurrection. It honored the frightened twelve-year-old who couldn’t wake herself from the dream, while allowing the adult me to finish the story on her own terms.

The nightmares still visit sometimes, though less frequently now. When they do, I no longer wake in panic. I reach for a notebook. I listen. I write. Because I’ve learned that every dream, even the terrifying ones, contains a fragment of language waiting to be set free.

Why I Still Write the DarkReaders often ask why I continue to write thrillers—why I linger in the dark when I’ve already survived it. The answer is simple: because the dark is where I found my voice.

The shadows aren’t just where fear lives; they’re also where empathy grows. In exploring human darkness—greed, guilt, survival, grief—I’ve learned to honor the complexity of being alive.

For me, Long Since Buried isn’t just a story of murder or revenge. It’s a story of reclamation—of what happens when a girl who once dreamed of being hunted becomes the woman who writes the ending.

That’s the true closure fiction gives us: not a perfect resolution, but a language for what once felt unspeakable.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3583" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:356px;height:auto" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.comSometimes the stories that terrify us are the ones that most need to be written.

Sometimes the only way out of a nightmare is through the page.

And when we finally reach the end—when the words fall quiet and the ghosts rest easy—we realize we were never being hunted by monsters.

We were being pursued by our own courage, waiting for us to stop running and turn toward it.

October 1, 2025

“Whimsy and Bliss” by Angela Grey

Shady Oak Press (2025)

ISBN: 978-1961841468

Reviewed by Stephanie Elizabeth Long for Reader Views (09/2025)

Abigail Whimsy and Lainey Bliss have been best friends since the second grade. Like yin and yang, their opposites somehow fit together like errant puzzle pieces. Whimsy exists in a world of vibrant dreams and imagination, while Lainey is pragmatic and even-keeled, which anchors Abigail. Because nothing good can last forever, the girls have one final summer together before Lainey goes off to a fancy college, leaving Abigail behind.

Before Lainey leaves, Abigail has devised a plan. They will create a map (complete with a detailed legend) and explore all the mysteries of their town—dismantle the “thin” places, using her late grandmother’s journal (chaotic musings) as a guide.

As they delve deeper into the journey, Abigail’s reality becomes skewed, and Lainey’s attempts to keep her friend’s sanity in check become more difficult. The places they visit awaken a humming within Abigail, and the more they add to the map, the louder the hum becomes.

Whimsy and Bliss is a coming-of-age literary masterpiece. Angela Gray’s writing is known for its vivid imagery and deep metaphors, and this novel is no exception. Readers will quickly be immersed in Abigail’s world of wanderlust, where magic and realism become blurred. Beyond that, the character-driven story explores themes of friendship, self-discovery, and bridging the transition from childhood to young adulthood.

Sometimes it can be hard to decipher the difference between imagination and illness. The author has done an excellent job of illustrating Abigail’s unraveling—the whispering of nature, the ebb and flow of the hum, and the excitement turned obsession. With every place Abigail and Lainey traversed, I fell more in tune with Abigail’s frequency, at times questioning what was real and what was fictitious—this is the type of story that makes you see the world differently.

Whimsy and Bliss certainly highlights the plight of mental illness, particularly hypomania. Still, at its core, the novel’s overarching message is one of connection and trust—it’s the impenetrable sisterhood between two young women on the cusp of adulthood. In a world that is often stuck in the me-versus-you mentality, the solidarity between friends is refreshing, teaching us that we don’t have to suffer alone; we can lean on others for support.

For readers who love young adult books about friendship and adventure with a focus on mental health, this literary gem will appeal to you. Angela Gray’s exquisite prose is unmatched, and the multilayered characters are memorable. Abigail and Lainey’s map of thin places will forever hold a special place in my heart.

agoraphobia anxiety bipolar disorder book review chronic mental illness cognitive behavioral therapy delusions depression eating disorders exercise grandiosity grief group therapy hallucinations how to write a memoir intrusive thoughts Journaling meditation memoir writing tips mental health mental illness mindfulness nature therapy nutrition OCD psychosis psychotherapy PTSD schizophrenia self-harm social anxiety disorder social withdrawal stigma stress stress reduction suicide support group support group work writing suggestions writing therapy YA fiction YA fiction about mental illness YA novel YA novel about mental illness YA romance

September 30, 2025

Of Laughter & Heartbreak book trailer

This is the summer of locked doors, fragile rituals, and the ghosts that keep count.

I’m Stevie Matthews—almost sixteen, the kind of girl people whisper about. “Bat-shit crazy,” they say. Maybe they’re right. This summer, the order cracks. Obsessive thoughts tighten like barbed wire, rituals multiply, and the only way forward is a hospital stay I never asked for.

Behind those doors, I meet strangers who feel both broken and familiar, each carrying their own secret galaxies of fear and hope. Together, we make a kind of map—messy, jagged, stitched with laughter, unraveling with heartbreak.

This is the story of how I learn that friendship can be born from accident, that healing isn’t neat or pretty, and that sometimes the bravest thing is to stay.

This book is a tender, unflinching portrait of adolescence, OCD, and the fragile alchemy of survival—equal parts bruised and luminous, like a diary written in ink and ghost light.

agoraphobia anxiety bipolar disorder book review chronic mental illness cognitive behavioral therapy delusions depression eating disorders exercise grandiosity grief group therapy hallucinations how to write a memoir intrusive thoughts Journaling meditation memoir writing tips mental health mental illness mindfulness nature therapy nutrition OCD psychosis psychotherapy PTSD schizophrenia self-harm social anxiety disorder social withdrawal stigma stress stress reduction suicide support group support group work writing suggestions writing therapy YA fiction YA fiction about mental illness YA novel YA novel about mental illness YA romance