Thresholds Between Worlds: Writing the Dreaming Mind

There are nights when the mind becomes a borderland—not waking, not sleeping, but something tender and trembling between. That’s where my stories live. When I write, I’m less interested in plot than in passage—the subtle moment when reality begins to shimmer and something unseen breathes through. It’s the hum before a dream takes shape, the hush in a library where imagination crosses the threshold.

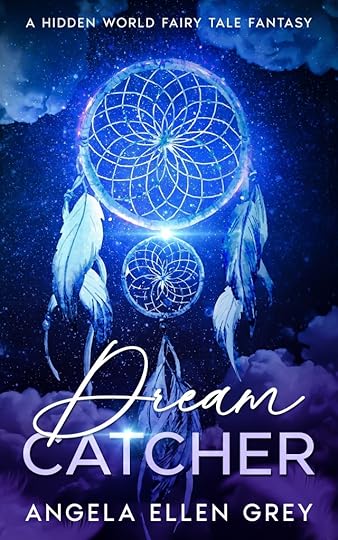

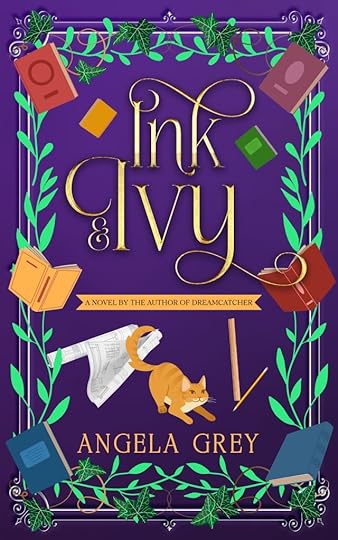

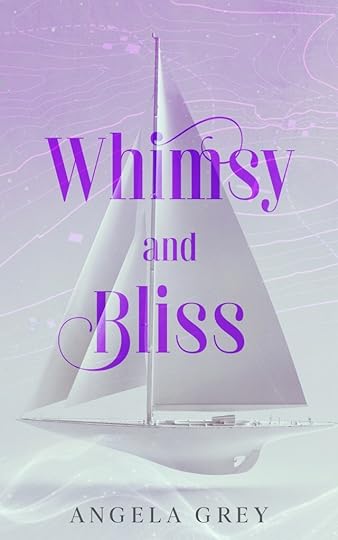

My novels Dreamcatcher, Ink & Ivy, and Whimsy and Bliss were each born from that in-between space: where dream logic and daylight ache overlap, where imagination is both refuge and revelation. I’ve come to think of them not as separate stories, but as three rooms in the same house—the House of the Dreaming Mind.

1. The Doorway in the Dark

1. The Doorway in the DarkThe idea for Dreamcatcher began with an image: a girl climbing through a fire-escape window, brushing against her grandmother’s dreamcatcher, and falling into another world. For Dash, my protagonist, the dream realm of Baumwelt is not a fantasy world in the traditional sense—it’s a reflection of her inner life. Every creature she meets, every landscape she crosses, echoes her memories, fears, and ancestral lineage. The world outside her window dissolves, but what replaces it is not pure invention—it’s memory rearranged by sleep.

Dreams are the language of the unconscious, but they are also archives of ancestry. In Dakota tradition, dreams carry instruction; they are bridges to spirit, not mere illusion. Writing Dreamcatcher, I wanted to honor that worldview—to let dream be teacher, not escape.

The dreaming mind, after all, has its own geography. It’s where past and present fold into each other, where the living and the dead keep company. Dash’s journey through Baumwelt is really a journey into inheritance—into how memory, myth, and trauma shape the self. When she wakes, nothing around her has changed, but she has. That’s what every good story does—it sends you somewhere so that you can return with new eyes.

2. Ink as Spellwork

2. Ink as SpellworkIf Dreamcatcher is the dream entered through sleep, Ink & Ivy is the dream entered through creation. Marisol, the girl who runs a hidden bookshop, learns that the stories she writes can alter reality. What she pens becomes what she lives; language itself becomes a portal. But her gift carries risk: every act of creation has a cost. Words can heal, but they can also harm.

In that sense, Ink & Ivy is about authorship as alchemy—the idea that writing is both spell and surrender. As writers, we are always crossing thresholds between imagined and real. We live half in the world and half in language. The line between the two blurs until even we can’t tell which is which. When Marisol writes, she’s not escaping grief; she’s giving it shape. The ink becomes her ritual of remembrance.

Writing, too, is a dream you enter deliberately. When I’m deep in it, time dissolves, sound thickens, and the body becomes peripheral. That liminal state—the creative trance—is the same consciousness that dreams speak from. It’s what poets call flow and mystics call vision. I’ve come to believe that all art is a form of lucid dreaming: we are awake, but we allow the dream to guide our hand.

3. Between Wonder and Loss

3. Between Wonder and LossThen there is Whimsy and Bliss—a story set not in another world, but in the precise moment before girlhood fades into adulthood. Abigail Whimsy is the dreamer; Lainey Bliss is the realist. Together, they chase “thin places,” secret corners of their lakeside town where the fabric between worlds wears thin. Their summer map becomes a pilgrimage of goodbye—to childhood, to friendship, to the certainty that magic is only for the young.

In Whimsy and Bliss, the dreaming mind is not only nocturnal—it’s emotional. The dream here is nostalgia: the ache for what can’t be returned to, the shimmering almost-memory of who we were. When Whimsy and Bliss explore abandoned libraries and climb water towers under moonlight, they’re searching for wonder before it vanishes. They are practicing a kind of everyday mysticism—the belief that the ordinary world is already enchanted, if only we pay attention.

This, to me, is the heart of the dreaming mind: it notices what others overlook. It lives in metaphor, in symbol, in atmosphere. It insists that even grief has its own radiance.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3681" style="aspect-ratio:0.666931321953156;width:404px;height:auto" />Photo by Kaique Rocha on Pexels.com4. Dream as Bridge, Not EscapePeople sometimes ask why I write “fantasy.” I never quite know how to answer, because my worlds are not so much invented as revealed. Fantasy, for me, is not an exit door—it’s an entrance. Dreaming and writing share a purpose: they make the invisible visible. They bridge what logic can’t. When I write about portals, I don’t mean only magical doors. I mean threshold moments: the second before grief hits, the silence after someone says I love you, the pause between inhale and exhale. These are the real portals, the moments where transformation begins.

The dreaming mind knows this. It’s always translating feeling into image: a locked door becomes fear; a rising tide becomes memory; a missing key becomes forgiveness waiting to happen.

In Dreamcatcher, Baumwelt is Dash’s subconscious given form. In Ink & Ivy, imagination becomes tangible, able to wound or heal. In Whimsy and Bliss, dream takes the shape of longing. Each story moves through a different register of the same truth: that what we imagine is not separate from who we are.

Fantasy still matters because it reminds us that the world is layered. Beneath the surface of the ordinary lies a pulse of mystery, waiting to be remembered.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3673" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:308px;height:auto" />Photo by Ron Lach on Pexels.com5. The Craft of CrossingWriting the dreaming mind requires a particular discipline of attention. It’s not about inventing strange worlds, but about listening for what already hums beneath language.

I’ve learned to approach each story like a lucid dreamer: half-awake, observant, unafraid. When a sentence feels too rational, I let it unravel. When logic tries to take over, I ask what image might speak instead.

A novel like Dreamcatcher grows through atmosphere before plot; it must be dreamed onto the page. Ink & Ivy demands reverence for language itself—every word carries spell-weight. Whimsy and Bliss thrives on emotional resonance—the threshold between childhood and adulthood is its own kind of magic realism.

To write the dreaming mind, one must accept unknowing. The story reveals itself only as you move through it, like a dream that solidifies upon waking. You can’t outline it entirely; you can only walk with it.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3683" style="width:280px;height:auto" />Photo by Mo Eid on Pexels.com6. Waking GentlyWhat I love most about dream-based writing is how it teaches you to wake differently. When you step out of a story like Dreamcatcher or Ink & Ivy, you don’t just return to life—you return to it changed. Readers often tell me they see their own dreams differently after finishing these books. That is the greatest compliment I could receive. It means the stories have done their work: not to distract, but to awaken.

The dreaming mind is not a place we visit only at night. It’s a consciousness we carry—a sensitivity to meaning, pattern, and possibility. It’s the part of us that still believes rivers can whisper, that trees remember, that words are alive.

Writing through that lens keeps me tethered to awe. And awe, I think, is a form of prayer.

[image error]Pexels.com" data-medium-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." data-large-file="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." src="https://angelagrey.wordpress.com/wp-c..." alt="" class="wp-image-3671" style="aspect-ratio:1.50044656147663;width:320px;height:auto" />Photo by Tara Winstead on Pexels.com7. The Threshold ItselfI return often to that fire-escape window from Dreamcatcher. The girl climbing through it. The touch of feathers, the shift of air. The dreamcatcher trembling like a heartbeat.

That moment—between step and fall, between real and imagined—is the space I write from. It’s the threshold itself that matters, not what lies on either side.

Because the dreaming mind isn’t about choosing one world over another. It’s about learning to live in both at once. To walk through daylight with a trace of starlight still on your skin. To carry the dream with you, awake.

Every story I’ve written is, in its own way, a map back to that place.

Dreamcatcher taught me to honor ancestral dream as truth.

Ink & Ivy taught me that language is alive.

Whimsy and Bliss taught me that growing up doesn’t mean losing wonder.

All three remind me that imagination is not an indulgence—it’s a responsibility.

The dreaming mind keeps us human. It holds the world together, one dream, one story, one word at a time.