Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 179

January 4, 2016

What does virtual reality sound like?

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Much of the focus around virtual reality has targeted the visual experiences, but audio is critical for pulling people into stories that unfold through digital worlds. In the opening minute of Lost, the first VR short film by Oculus Story Studio, a compelling soundscape that brings the viewer into the scene before leading them deeper into the narrative. Saschka Unseld, creative director at Oculus Story Studio, knows that sound is critical to hooking people and heightening their experiences.

3D audio is an integral part of virtual reality.

“The first thing you see is the firefly,” said Unseld, describing the opening scene. “Our thought was to have something tiny, the opposite of overwhelming, and let her be our guide into the world of VR.” The story continues with a singing bird that flies by, drawing the user into the forest.

“We used spatialized audio, so you know it’s coming from the right. That’s when the story for Lost finally begins, because you have settled in and we have your attention.” 3D audio is an integral part of virtual reality. It’s different from what people typically think of as “surround sound.”

When a person is watching a home movie connected to a surround sound system, the sounds come from the speakers in front, to the side and behind the viewer. If the viewer moves, the sound doesn’t change direction.

In virtual reality, all the sounds come from stereo headphones, which are part of the VR headset, but sounds seem to emerge from every direction because the audio is processed in a way that mimics how a person actually hears. Instead of coming from multiple speakers, 3D audio seems to come from infinite spots around the wearer. It isn’t a soundtrack. It’s a spatial reality all around the user.

The sound of cricket chirping near a VR headset wearer’s feet will get louder as the person kneels down. When the wearer turns her head toward the sound, she will see the insect in front of her. It isn’t a soundtrack. It’s a spatial reality all around the user, according to Unseld.

Music can also be a vital component of the virtual reality word. ZeroTransform, the developer of Pulsar Arena, is currently working on a VR music video called NUREN.

“The chief difference is immersion and positionality,” explained Jake Kaufman, the music wizard at ZeroTransform. “You are actually there. That involves reverb, occlusions and geometry. The challenge is making a place.” Part of this realism comes down to HRTF, which stands for head-related transfer function. This is the name for how a sound is different coming in one ear than the other, which lets your brain determine where the sound originates.

It is also about how a sound changes when it vibrates through the bones and flesh of your head. Listen to this video with headphones to hear how HRTF sounds compared to a film soundtrack.

If the sound doesn’t perfectly match with the 3D visuals, you might be taken right out of immersion.

HRTF sounds are recorded with a pair of microphones placed like ears inside a container that mimics a human head. In addition to ensuring the sound works just right, implementing 3D audio can prove challenging in other ways. If the sound doesn’t perfectly match with the 3D visuals, you might be taken right out of immersion.

“Let’s say you are in a field, and you hear the wind blowing, and then you move your head and everything changes,” said Tom Smurdon, audio content lead at Oculus, explaining how bad audio can break the suspended belief that a person has while immersed in a VR experience.

“In videogames, you make a stereo loop, and you just place that in an area. The problem is, in VR, this sound would be glued to your head. That’s not what you want at all.”

With VR games, sounds are tied to specific objects or points in space, too. In the example of the field, Smurdon would place four different wind sounds in the cardinal directions of the scene. There may even be eight sound effects so that when the player turns around, the sound would change so that the wearer would instinctively know which way was north the entire time.

This careful placement of noises in a 3D space—placing both high and low, near and far—creates a spatial soundscape useful for realism and immersion as well as for direction and narrative. All of this serves the ultimate goal of any VR journey: making the user experience a particular set of feelings.

“You have a covenant of trust with somebody when you put a visor on their head,” said Kaufman. “You are replacing their mental soundtrack with your reality. It’s not called virtual reality for nothing. If anything, that emotional connection is doubly important in VR.”

December 28, 2015

On Quentin Tarantino’s masterpiece of misogyny, The Hateful Eight

What you make of Quentin Tarantino’s latest genre genuflection The Hateful Eight will really come down to one thing: how many times can you tolerate a woman getting hit in the face?

The gauntlet is thrown down early: Kurt Russell’s ursine bounty hunter John Ruth smashes his captive, Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Daisy Domergue, full in the face when she speaks out of turn. She gets a lingering close-up courtesy of Tarantino’s vaunted “glorious 70mm” frame, seething with fury through the blood.

I lost count of how many times Domergue gets slapped, thumped, and punched, but I’m comfortable with saying it was “a lot.” It is aggressively distasteful provocation, calibrated to leave no viewer on the fence. The film is deliriously violent, but these moments of intimate, inescapably loaded abuse cut just a little deeper than the piles of exploding heads and bloody vomit.

aggressively distasteful provocation

For anyone assuming Domergue will get her exploitation-flick revenge, I advise tempering your expectations. The Hateful Eight is something new for Tarantino; he’s visibly trying to Say Something Big. Inglorious Basterds smartly kept its commentary diffuse, and Django Unchained found time to render slavery in vivid, brutal strokes, but The Hateful Eight is a vicious examination of post-Civil War America. And, also, exploding heads.

Tarantino introduces his characters as archetypes first: Russell as John Wayne, Walt Goggins as an embittered ex-Confederate, Tim Roth as a mincing, proper British caricature. Then, over three meticulous hours, he complicates and enlivens them at every turn. This is Tarantino’s stagiest script, bar none; it’s set in a single location (give or take a few snowy trails) and lays out one verbal confrontation after another.

The conversations are knotty, and always reveal character in ways both subtle and obvious; they’re a far cry from the interminable wheel-spinning of 2007’s Death Proof. Tarantino’s no stranger to flashy talk, of course, but here it all matters. The film feels tight, though naturally your mileage may vary here; despite its three-hour runtime it moves with purpose, with little of the bloat that weighed down Django.

That’s not to say Tarantino’s peccadillos aren’t on full display, because oh, are they. The score lifts from unused compositions by Ennio Morricone for John Carpenter’s The Thing (itself a riff on the ethos of Carpenter’s idol, Western auteur Howard Hawks), and the plot echoes The Thing in its broad strokes. The snowbound setting, costuming, and florid style nod to Spaghetti Westerns, particularly Sergio Corbucci’s downbeat The Great Silence from 1968. A slow-motion close-up of horses galloping through a snowstorm conjures the surrealist limbo of Lars Von Trier’s recent work. You get the idea.

The Great Silence (1968, dir. Sergio Corbucci)

The Great Silence (1968, dir. Sergio Corbucci)But this is far more than a game of spot-the-reference, as Adam Nayman incisively teases out at Cinema Scope. Working with his frequent DP Robert Richardson, Tarantino lets the cinematography play operatic counterpoint to the meaty script. He uses a series of four split diopter shots—a technique using a deep-focus-made-easy lens, resulting in a characteristic blurry line down the center of the frame; epitomized by Brian De Palma as well as, hey, Carpenter’s The Thing—to track two characters’ shifting relationship, linking them visually before they themselves are fully aware of what’s happening. The ultrawide 70mm also allows Tarantino to do things like neatly tuck a coach and entire train of horses into a single composition, or pull off a gorgeously staged musical interlude that uses nothing more than a stationary camera and shifting focus.

Of course alongside all that impeccable craft we have a baroque, sexually violent centerpiece monologue prominently featuring the word “dingus,” an absurd voiceover done by the director himself, castration-by-gunfire, an embarrassing White Stripes needle drop, and the abrupt bloody murder of the film’s few legitimately innocent characters—but also a razor-sharp summation of living under the yoke of racism, snow-draped, quietly beautiful vistas, and fleeting moments of grace. This is insane, scattershot cinema; it’s like some lost Italian epic from the 70s, coursing with bad taste.

The film is inescapably rough and confrontational; all the more so for this ragged juxtaposition of form and content. And, most troubling of all, it hangs its thematic hat on the increasingly battered Daisy Domergue, played with feral abandon by Leigh. Domergue’s treatment throughout the film is repulsive. Yes, she’s a criminal. Yes, it’s called The Hateful Eight: hateful. And yes, things end terribly for pretty much everyone. But Tarantino wrote Domergue as a woman; he wrote John Ruth to repeatedly brutalize her. Why? It demands that you make sense out of it.

Early on it’s almost a punchline, if you’ll pardon the pun, as if Tarantino wanted to actively turn viewers off. But what a film does and how you interpret it may be two very different things. Film isn’t a one-way transmission of Good or Bad ideas. Because Mad Max: Fury Road (for example) is a movie about women struggling against an oppressive patriarchy does not immediately mean it’s a movie about feminism or, worse, a “feminist movie.” It’s easy to passively receive messages from media; we have to do the work of dissecting those messages.

And it’s no secret that Tarantino comes from a film tradition that prides bluntness over everything else; exploitation films don’t mince words, and they don’t cut away. Remember the Goodbye Uncle Tom ferocity of Samuel L. Jackson in Django Unchained? Nothing in 12 Years a Slave matched that guttural, discomfiting contradiction of a character. That’s the essence of exploitation. The austerity of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring became the brutality of Wes Craven’s The Last House On the Left, and perhaps the stately middlebrow dress-up of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln begat the splattered-brain mess of The Hateful Eight.

///

Tarantino slowly brings together two unlikely partners over the film: Walt Goggins’s former rebel Chris Mannix and Sam Jackson’s ex-Union Major Marquis Warren. Mannix claims to be the sheriff of nearby Red Rock, and indeed it seems he has some twisted respect for justice: he is bound and determined to see Domergue die for her crimes. But it’s not justice that battered her, nor justice that sees her foot blown off, nor justice that sees her meet her end from the rafters of Minnie’s Haberdashery. It’s misogyny.

Domergue’s continuous abuse is the natural outcome of a frontier—and country—built on cruel, rapacious masculinity. John Ruth brutalizes her, but also believes she deserves to be hanged, not summarily executed. In this world, Ruth’s conviction passes for a sense of decency; when he’s gone, the mantle of hanging Domergue is taken up to Mannix and Warren. They honor Ruth, not show mercy to Domergue, by their actions.

women in Westerns don’t get to enact violence; they witness, or suffer

As a murderer—an unrepentant one, at that—Daisy Domergue encroaches on the violent territory of the Western man. Natural order is huge in Westerns. If the hero has to kill the bad guy, he leaves town and returns to the wilderness. It’s all heightened drama, played out at mythic scale. By and large, with the rare sort-of exception like 1971’s rape-revenge hybrid Hannie Caulder, women in Westerns don’t get to enact violence. They either witness it, or suffer it.

With the inclusion of a brief coda featuring a forged letter from Abraham Lincoln—the great unifier, lest we forget—Tarantino suggests that America, in the land-of-the-free all-men-are-equal sense, is a lie built on hatred, pure and simple. It’s as much a myth as the white hat cowboy gunning down the black hat cowboy to make everything better. This is hardly a fresh idea, but Tarantino makes his point fiercely, alchemizing several different genres and hundreds of years of American social strife into a potent climax. A beautiful thing happens when both Union and Confederate, black and white, put aside their differences: they can come together just long enough to hang a woman.

December 22, 2015

That Dragon, Cancer is coming out extremely soon

A lot can change in three years. It was back then that the Green family and the small team with them started production on That Dragon, Cancer—a heartfelt videogame that passes through interactive vignettes like a dream, depicting the family’s journey with baby son Joel as he battled with cancer. He was still fighting it back then, Joel, that is—still alive and under the care of his parents. The story around the game changed when, in March 2014, he passed away. But he is not totally gone from this world, living on in the memories of those who loved him and inside the game about him: his voice, likeness, and personality permeate.

The other significant change across that time is That Dragon, Cancer now being finished. It even has a release date. On January 12th, 2016 it’ll be out on the Razer Cortex Storefront for OUYA and Forge TV, and on Windows and Mac through Steam and a Humble widget. You can pre-order it at $14.99 right now over on its website.

“Everybody has a Joel”

Although That Dragon, Cancer is based on reality—sometimes distressingly so, like a scene in a hospital at night when Joel relentlessly cries hurt into the air—the Green family have asserted that, in some way, it’s about all of us. Cancer has affected the majority of us in some way. Most of us have known loss. And so it’s a game that, yes, is about a specific family, but you’ll likely be reminded of your own loved ones and hard times while playing.

“Everybody has a Joel,” father Ryan Green told us at Two5six earlier this year, “so this becomes a memorial that we get to put out there for people to walk through and for it to hopefully add to their lives. My hope is that people will feel like this experience added rather than took away from.”

You can pre-order That Dragon, Cancer and find out more about it on its website.

The Year In Weird

I think I started writing about videogames because I was lonely. What I found in games was a sorely needed form of two-way communication. It started sometime in 2007 when I happened across the Indygamer blog (founded by Tim W., who I’ve now joined in doing similar work on Warp Door), which was regularly discovering and writing about these small, weird games that you couldn’t find anywhere else.

After a while, I started to recognize some of the recurring names of the individuals that were making these fascinating experiences. With some of these creators, it was possible to see themes across their oeuvre that collectively explored more than, say, mere mechanical experimentation. Making games seemed to be both a creative and a more personal type of outlet for these people, as if they operated like diary entries, providing insight into their thoughts and feelings as their lives played out. Noticing patterns in their work, spending more and more time with it, reading deeper and deeper, I started to feel attached to these people who I was able to concoct a vague impression of from playing their raw and experimental games.

these were the ones that spoke most to me

A few years after becoming absorbed in what evolved into a hobby, I happened across a desire to reach out to these people, who had only existed disembodied in my imagination. Yet, this impulse wasn’t realized in writing emails to these people, sharing my thoughts and thanking them. It felt weird to do that, as if I were a stalker unveiling my tainted presence in their lives. Instead, I started writing my thoughts on these videogames down, sending them into the chaotic void of the internet, just as they had done with their games. What made this compelling was that the ideas and emotions inside these games were usually crude and often communicated abstractly, meaning they came across as simply weird to mostly everyone, except if you were willing to look beyond that and connect the dots—yes, they were strange, but everything in these games had come from somewhere.

Five years later, I’m still doing the exact same thing, and I still care tremendously about games as a vessel for a person’s inner world, for them to eviscerate what’s bothering them, or to explore their thoughts on a complicated subject (all the while developing their ability and style in doing this). I tell you this so that you know how I’m approaching and presenting the games listed below. All released in 2015, these were the ones that spoke most to me, that let me into their creator’s mindspace and maybe also opened my eyes to something. In short, these were the games of 2015 that brought me closer to other people.

im null

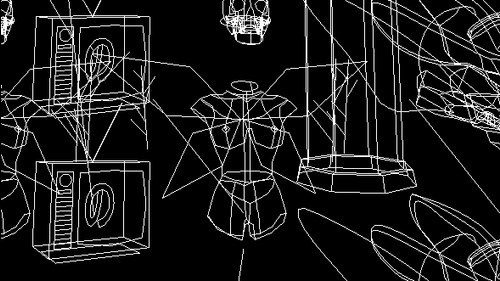

Thoroughly, but not unequivocally, im null is a virtual world about alienation. You wander as an indistinctive integer inside a black space, which is sporadically—and sometimes terrifyingly—scattered with concepts drawn in scratchy white lines. An endless highway, a woman screaming over the phone about a breakup, a lonesome drug trip, a graveyard; all these sights have in common the theme of exclusion (and are, themselves, distanced from players through their cryptic presence). Among them there sometimes wanders “null,” the shapeshifting skull that haunts this online space, banning the anonymous wanderers without mercy or reason.

It is into this eerie realm of nothingness that its lead creator, Zak Ayles, seemed to transpose an agony. In the months prior to launching im null he had tried to remove himself from the internet and escaped into his inner self for a while. His darkening thoughts must have slow-cooked during that period with this digital space bookending that process. And so what you might suppose about im null is that its title is a confession (both literal in that Zak might be playing as “null” inside the game, and metaphorically reflecting his state of mind) and the rest of the experience has been built to expand on that thought like an interactive monologue.

Play im null on Zak’s website or on Game Jolt.

///

Stick Shift

Stick grasped firmly, you stroke your hand up and down, not furiously but erotically. Small, rousing jerks. Long, teasing pumps. The car revs in excitement, accelerating into the ticker, ready for the next stage. You place your palm on the stick and fiddle it into the next gear and then… Tingling explosions of pleasure from head-to-toe, bursting, inside and all over the carburetor. Eyes roll back. Lips are bit. Exhausts drip.

Robert Yang has been exploring gay sex and erotica through games over the past year and more with the likes of Succulent, Rinse and Repeat, and Cobra Club. But it’s Stick Shift that stood out to me. An “autoerotica,” it captures both the excitement and the danger of gay sex and its relationship with technology. For me, someone of queer identity, it seemed to acknowledge my specific experience of finding vindication through a computer (the car representing technology in this allegory), specifically the media and community that helped me and that couldn’t have been reached otherwise.

Stick Shift speaks to an individual person’s non-straight pleasures

More than that, there’s a scene that has a 48 percent chance of happening in the game, in which a pair of armed cops turn up at your car window to disapprove of your open display of sexuality. They threaten authoritarian violence; something that queer people have known for centuries. Yang contextualizes this scene outside of the game as a call-back to the the Stonewall Riots in 1969, during which the queer community protested against the cops through flamboyance. And so Stick Shift speaks to an individual person’s non-straight pleasures (whether mine, Yang’s, or anyone else’s) but also to the historical troubles that queerdom has endured and, eventually, began to surmount. And, heck, it’s also goddamn arousing.

Download Stick Shift on itch.io.

///

Gardenarium

Vacationing in someone’s headspace isn’t possible but, if it were, I’d surely make the beautiful imagination of Paloma Dawkins one of my first stops. She emerged in blossom this year: I imagine her entrance to the medium as an image sewn in grass, her pose angelic, a delicate hand reaching out to a drooping petal, flower crown atop her head. Practised in vibrant animation, Dawkins made nature and everything it sprouts dance with her videogame work this year. She brought with her a distinctively bright palette, forgoing the expected choice of colors for each of her plants and trees to favor a motley intensity.

Gardenarium was her first, but there was also Alea, and that one is meant to be played with a moss controller. You place your hands in actual green lichens in order to play as if to symbolize the intimacy between human and verdure that Dawkins realizes on-screen. Gardenarium presents flora as a 3D stageshow; all singing, all dancing. Whereas games like Proteus and Eidolon portrayed nature as a grand tableau, trees and shrubs still and silent, Gardenarium brings it all to life in motion and song. It’s the people and creatures that are still, as if stunned by the sights as they grow around them, flashing and rippling in unison. In this place found on a cloud, you are safe and surrounded in beauty, able to chill and ruminate on the fabric of life. I get the impression that this is where Dawkins goes, in her head and through her art, to find peace.

Purchase Gardenarium through its website.

///

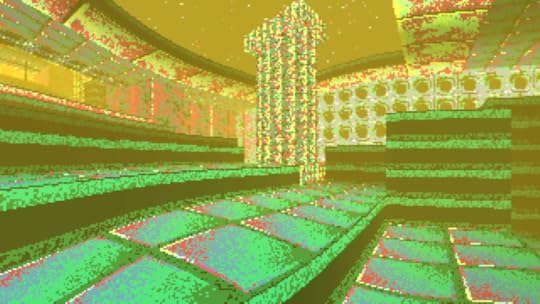

Strawberry Cubes

Loren Schmidt’s games are increasingly about texture and confusion. The two are interwoven. In Strawberry Cubes, you rely on the arrangement of sprites, the 2D mosaics of each room, to navigate. Ostensibly a trip through your grandma’s house, the game casts you inside a lo-fi labyrinth where the significance of icons and interactions have to be guessed at. Where are you trying to go? What are you trying to do? Nothing is known. There are skulls. There are frogs. There are numerous crimson icons flashing away. It’s all telling you something, you just don’t know what.

To wit, playing Strawberry Cubes is like loading up a save state in a videogame that you stopped playing months or years prior. You have to relearn what each button does and how its systems interact in ways that let you progress all over again. Except you don’t have that previous knowledge to draw upon. Your process ends up resembling cellular automata in that you attempt to find structure in the noise, testing out each process with each room, steadily grasping a workable map of this place and its rules in your head.

Schmidt’s interest in cellular automata is clear as he’s not only made a tool that lets him work with it but incorporated its evolutionary procedures into his games. Instead of a computer, he uses us as the inquisitive data, trying to make sense of the worlds he creates. Going forward, his next set of projects only further pronounce this interest, providing us with endless alienscapes to explore with the meaning and perhaps the rules being left for us to determine.

Purchase Strawberry Cubes on itch.io.

///

Hylics

Mason Lindroth released his masterwork with Hylics this year. His games are recognizably made in clay and animated with dithered stop-motion, this one especially so. Where his smaller projects before Hylics etched out specific curiosities and clay-monsters that he would re-use, it’s in this larger RPG that he really indulges his talent, bringing his previous work together under a single philosophy.

Hylics is about the malleability of material. You crush trash cans, mold clay sigils, throw highly-explosive dynamite and, when you die, also witness the flesh melt away from your face. Everything disintegrates, is molten, rapturously moving from one state to another as per the cycle of life and death. This is a celebration of the material world. It also sees Lindroth entertaining the playful tactility he so clearly loves and that is so desperately lacking in the digital game space. Hylics purports to be a journey towards spirituality but it is much more a testament to the glory of creation and destruction, which can only be found in the corporeal space that Lindroth so readily enjoys.

Purchase Hylics on itch.io or on Steam.

///

Knossu

Knossu is an experiment in non-euclidean architecture and it is terrifying. Instead of puzzles (although it is still puzzling), creator Jonathan Whiting sought to find the horror that’s possible within the limitations of tight corridors and unreliable geometry. It’s a reworking of his earlier game Knoss that adds structure to the concept while also expanding it to a fuller experience. Playing both of these games now is to condense the years between them and see the evolution of the idea as well as the progression of Whiting’s own skills. It all comes together like a perfectly composed nightmare.

Knossu benefits from two sources that its predecessor didn’t. First is the inspiration Whiting took from JP LeBreton’s notion of “Tourism play.” And second is Whiting’s own experiments in 3D level design. What we end up with is a frankly panic-inducing challenge: enter four separate spaces to bring a beam of light to a hub-like center that connects them all. The catch is that there’s some demonic and vague cloud of noise ambling in these areas. It warps your vision and sends alarm bells off in your ears upon approach and, if it catches up to you, warps you back to the hub. It’s not scary by itself, but consider that it’s so easy to get lost among Knossu‘s architecture as it shifts behind your back and catches you in sinister loops. The game is an accomplished investigation in pulling the rug from under the player’s feet and a true testament to developing a single idea to its maximum potential.

Download Knossu on Jonathan’s website.

///

Orchids to Dusk

No other videogame came close to matching the wordless gesture that rings out into the infinite in Orchids to Dusk this year. You may not discover it straight away as it’s hidden and requires a certain submission on your part. But it is entirely the point of it all. I speak of it vaguely so as not to spoil it but also because it has a poetry that averts articulation. What, then, can be said about Orchids to Dusk? Firstly, it’s a game that has you feel out the final moments of an astronaut after they crash land on a foreign planet, running out of breathable air. What happens to them might be up to you or, more likely, it has already been fated by the dire circumstance.

Secondly, it’s the latest game by Pol Clarissou. When he’s not making playful digital toys or beautifully goofy slapstick, Clarissou tends to make solemn, solo experiences that encourage us to think about death or, at least, the nature of existence. They’re quiet, visually pleasing, and contemplative pieces. You’re exploring space, alone in a subway, or daydreaming in darkness.

Orchids to Dusk follows on from this trend in Clarissou’s work as you are a lone astronaut left to explore a planet sparsely populated with oases and nothing more. But where Clarissou previously used procedural generation to provide an endlessness to his games, Orchids to Dusk has a determined end, and it’s in that the game’s power emerges. It’s a full-stop at the end of his work up until now, one that resonates through all our lives, across the planet, throughout existence. It is eternal peace and it is abject horror—it is what unites all of us.

Download Orchids to Dusk on itch.io.

///

Rain, House, Eternity

Rain, House, Eternity is Kitty Horrorshow’s most personal game. It’s also the most implicitly distressing. And at the same time it’s the most hopeful. You wander through a series of intimidating architectural spaces in search of glowing purple gems. Pick one of these gems up and you get to read the thoughts of an unknown character who feels rejected by their family and the world. In short, they feel out-of-place, and it leads them to dark places where suicide doesn’t seem too bad an idea. Autobiographical or not, these snippets of monologue are certainly troubling, but it’s in pairing this with the surrounding chasms and enormous gray structures that Horrorshow excels.

She seems to acknowledge at a late point in the game the service that game creation has brought her. She specializes in crafting a specific kind of psychogeography. Her virtual buildings feel like individual people. They seem to talk to us in their silence. This is probably due to the emotional significance that Horrowshow grants them. She uses shape, line, color tone, and size to communicate her specific experiences of fear. And it’s in doing this that she seems to have broached and helped herself work through a number of tough personal matters. In Rain, House, Eternity she not only explores this but also reaches out to encourage us to find our own way of making peace where we need it.

Download Rain, House, Eternity on itch.io.

///

Selfie: Sisters of the Amniotic Lens

Gruesome at first, Selfie opens up after you’ve passed its early tests and turns into what can be a surprisingly touching community-based exchange. It starts with you sat in front of an old television, dead flies all around, a dismembered corpse staring at you coldly. After entertaining the masochistic beliefs of a cult and tapping into its black magic you’re able to depart this scene and head into cyberspace—it’s possible that you become one of the flies buzzing around the room you previously occupied. While it seems to then become a first-person shooter, the real heart to this game is found in the large floating bottles you can find in this new expanse.

These bottles are where the responses that new players typed out at the beginning of the game end up. “Shed your skin and tell me what lies beneath. What tears do you cry that are worth bottling?” the game asks upon opening it up. You can go as deep and personal as you like here but whatever you type will, technically, be visible to all other players, though not many of them will likely see it. Upon finding a bottle and reading the confession inside, you get the chance to “Condemn” or “Free” the writer, either taking away all their in-game currency, or giving them some of yours. If you choose the latter, you can also respond to their confession with a written reply (which, especially on the internet, is a freedom open to abuse), the idea being to offer this person your support in a more meaningful manner.

While creating Selfie, Dylan Barry was having theological issues that caused him to leave the church, while also growing increasingly paranoid. Given that the game acts as if an online confession booth but hides this underneath a nasty, uninviting preamble, it could be that Barry was working through his turmoil through the game’s themes. In any case, while it does contain religious ideas, it finds worth in a more universal gesture: encouraging people to help one another during their dark times, to mete out their sins and hopefully move on to a more positive space.

Purchase Selfie: Sisters of the Amniotic Lens on Steam.

Soviet City will turn urban planning into terror control

City building games are rarely exercises in democracy. The player’s agency stems from her role as a central planner; she designs cities that hopefully please their residents, but this is not a consultative, bottom-up process. Considerate urban planning in the city-building game is an act of benevolent dictatorship.

Soviet City, a forthcoming strategy game for PC, takes this association between city builders and central planning to its logical extension. Instead of being set in the deracinated utopia of most city builders, the game is set in soviet Russia, a place that may have wanted to be seen as a utopia but clearly was not. You play as a central planner tasked with keeping the populace in line and the government’s five-year plans on track. Happiness—or, more accurately, the absence of sadness—is a means to an end in Soviet City. A city whose population feels too much terror (the game’s metric of choice) is likely to rebel. But pure bliss is not the end goal. As the game’s documentation warns, “when terror level is too low, the dictator can replace you with more appropriate person.” Thus, a certain amount of volatility is desirable. Your goals as a planner are not perfectly aligned with those of your citizens or your overlords.

a certain amount of volatility is desirable

Although the period from which Soviet City emanates is ostensibly over, the legacy of the era’s architecture remains in flux. “There is a long tradition in the West of dancing on the Soviet grave in order to celebrate Western values,” writes Mirela Ivanova in an excellent Los Angeles Review of Books essay about socialist housing, “and so it comes as no surprise that the focus on Soviet historical artifacts is a focus entirely on the dead and decaying.” This sort of fetish, Ivanova notes, is apparent in the ruins porn of the architecture blogosphere. Soviet City does not exactly reclaim this architecture, but it does at least place it in the realm of the living.

A more generous recasting of Russia’s architectural heritage in Moscow, where a former Soviet worker’s canteen and bus garage in Gorky Park was transformed by Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture into the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. Primarily clad in translucent plastic, the building only retains a few hints of its former use. Portions of murals have been restored, but that’s about it. As Edwin Heathcote explains in Icon:

This is a building that is not so much about its contents, but about giving Moscow a reception space for art – which the city lacks – and about the reassessment of an era in which architecture was conceived for the masses. This is a proletarian building – a workers’ canteen in a park – and Koolhaas visibly enjoys the provocation that communism produced not only much of value but an alternative, a parallel universe in which capitalism and elitism were once not the only option. The Garage revels in the contrast between mass catering and elitist art. It is an architecture of dreaming, of subtle nostalgia and about the preservation of partial memory.

Soviet City exists somewhere between these approaches to the Soviet Union’s architectural heritage. It doesn’t fall into the pattern of fetishizing ruins that Ivanova critiques, but it also fails to gloss up Soviet architecture as Koolhaas has done in Moscow. The game is not a historical facsimile, but it shows an interest in warts-and-all as an ethos if not a practice. Architecture and urban planning is messy, even in a centrally planned world, and Soviet City is at least willing to engage that mess with clear eyes.

December 21, 2015

This Morse code game relives the 1914 Christmas truce

‘Tis the season for Christmas music to blare from every direction. They come from speakers, carolers, and buskers. They are played in stores and putative public spaces. As a side effect of this sonorous onslaught, ostensibly cheerful songs become backing tracks to breakups and calls announcing the sickness of loved ones. Omnipresent holiday cheer, as social networks have previously learned, cannot coexist with sensitivity to personal context.

Relay, a game created by Jon Reid for the 34th Ludum Dare games jam, uses this incongruity to make a historical point. Set in December of 1914, the game juxtaposes a light, instrumental version of “Silent Night” with the sounds of the First World War, namely bombs dropping and telegraphs beeping away. You play as a telegraph operator, relaying messages from the front line. By necessity, the messages are short. By virtue of the nature of warfare—particularly in 1914, but also generally—they are unpleasant. The messages usually start with send: send air support, send food.

The messages in Relay, like the game’s background music, take on a musical quality. Unlike Alex Johansson’s Morse, which treated Morse code as a merely sequential series of long and short beats, Relay is concerned with the rhythm of these beats. The long and short notes that make up each letter must follow at very specific intervals; you can’t take a downbeat off while you find your bearings. Think of Relay as high-stakes Whiplash: are you rushing or are you dragging? At the same time, the game’s approach to Morse code is also exceedingly generous. An incorrect letter can be immediately repeated, leaving a jumble of long and short beeps in the middle of words for the person on the other end of the line. Relay is both a harsh musical challenge and much easier than the task it seeks to replicate.

This leaves the time to wring out all the gruesome meaning

Relay’s use of “Silent Night” is not, however, a purely musical point. The game is interested in the precise historical context of December 1914 and, more specifically, the Christmas truce on the Western Front. Its messages and the delay casualty reports that come in between are an alternate way of describing the atrocities of trench warfare. Relay does not offer pictures or even particularly vivid descriptions of this hellscape, but uses Morse code to amplify the effect of its words. The prevailing thinking in higher education is that students who take notes by hand retain more material because they must slow their thinking and focus on every word. Relay’s Morse code transcription has a similar effect, forcing the player to slow down and agonize over every letter. This leaves the time to wring out all the gruesome meaning of phrases like “send food.”

The Christmas truce is the sort of feel-good historical moment that can be (and has been) transformed into a cheerful story. See, the incident seems to say, there is a fundamental goodness to these men. On one level, fair enough: men fighting in the trenches were not responsible for the course of the war. Yet to focus on the truce risks obscuring the general brutality of the war: it was very much the exception that proved the rule. That the story of the exception lives on (in videogames this isn’t limited to Relay, the truce also features in Verdun) is both understandable and worrying. The real lesson of war—and particularly this war—is brutality, and exceptions therefore need to be wielded with caution. Relay, with its terse wording and clashing audio clips, hints at this incongruity, but historiography has a way to go.

Grayout simulates the experience of post-traumatic aphasia

Did you play 2013’s Blackbar? You should have. It’s about censorship. Specifically, it has you filling in the black bars that the authoritarian regime, The Department, has used to cover up certain disallowed words in the letters sent between two women. It has a touching narrative, an underlying critique of state power, and it’s all wrapped up by simple, prodding interactions that have you steadily grasp the power of language.

Neven Mrgan, the studio that made Blackbar, has now brought out a prequel called Grayout. This time, the subject at hand isn’t state censorship (although it’s certainly connected) but medical experiments. You get inside the head of a woman called Alaine, a member of the totalitarian community The Neighbourhood—part of the same dystopia that Blackbar is set in—who wakes up in a hospital unable to move and struggling to put her words together.

“the frustration of knowing what you mean but not how to say it”

The doctor that sees to her informs Alaine that she was in an accident that both nearly killed her and left her paralyzed. She also has post-traumatic aphasia which Neven Mrgan neatly describes as “the experience of having a word on the tip of your tongue, the frustration of knowing what you mean but not how to say it, the feeling of being overwhelmed by the runaway thoughts inside your head and struggling to reign them in.” You’re probably familiar with any one of those frustrating experiences, but those who have aphasia suffer it at all times, whether reading, listening, or talking.

Your role in Grayout is to help Alaine form sentences as she talks with the doctor. After he has said his bit you’re left with a word cloud with which you must piece together the correct sentence in response. The stem of the problem is that you don’t know exactly what Alaine wants to say. There are no hints as to what the sentence might be so you find yourself trying to grasp Alaine’s way of thinking. It can be pretty tough, especially when you have tens of words and no idea how many you need or what order they should go in.

But that complete lack of help, and the consequent frustration, is part of what makes Grayout at least conceptually superb. When you do struggle it feels like you, too, are going through some of what Alaine is supposed to be with her aphasia. The game acknowledges the parallelism of the experience when the doctor notes that Alaine—but also you—is struggling. “I imagine that right now you probably find it challenging to form sentences, choose the right words, say what you mean—is that right?” he says at one point.

As minimal as it is—text and a background—Grayout makes use of every one of its components to try to bring you closer to Alaine’s state of mind. The unused words in each conversation are a great example. None of them are random. Instead, Neven Mrgan uses them as an opportunity to help describe Alaine’s feelings in each moment, as if the thoughts whirring around in her mind, but which aren’t intrinsic to what she wants to say. It might be “struggling” or “collapse” or “panic.” The background color helps along as it changes to suit Alaine’s mood: a hospital-teal when she’s talking to the doctor calmly, orange when she’s concerned, and red if she’s hurt or upset.

In later parts of the story, the doctor starts to use experimental drugs on Alaine, which enact changes in her thinking processes as well as the textual options presented to you. He tells her what each drug will do to her speech but it doubles up as a way to instruct you as to what kind of sentence to put together. It might be a full and poetic sentence or one with improper syntax, or maybe the drug has a caustic effect that makes every word seem hostile (which is represented by a random mix of upper and lower cases). Adding to all of this, and opposing the austere silence of the Soviet state-inspired Blackbar, Grayout‘s futuristic 1970s dystopia has a soundtrack of eerie synths worthy of a John Carpenter score. Each phase of the story gets its own chilling soundscape that helps express Alaine’s gradual, appropriate terror as she struggles to find the right words.

You can purchase Grayout for $2.99 on the App Store.

The Year in Anxiety

There’s nothing to be worried about, it’s just a quiet walk through the woods. The sun is shining through the leaves. Strings swell in the background as you amble about. Everything is okay.

Only it isn’t. Sure, Alessandro Salvati’s Anxiety Attacks starts out pleasantly enough. You are in the woods and everything is indeed picturesque. Your only real job is to breathe. Breathe in. Breathe out. Walk through a field of flowers. Breathe in. Breathe out. Breathe—you get the hang of it. Well, you think you’ve got the hang of it, and then the sky turns red, your breath shortens, vines claw at your field of vision like a possessed creature’s tentacles, and your screen is flooded with messages about your inadequacy. You are experiencing an anxiety attack.

Much as there are many ways to experience anxiety, there are many ways to experience Anxiety Attacks, very few of which will leave you in a peaceful state of mind. The most intriguing option is to watch the small collection of Let’s Play videos on YouTube, which juxtapose the formal conventions of the genre with the experience of what Salvati describes as a condition affecting “15% of the entire world population.” (The exact share of the population suffering from anxiety disorders is contested, but Salvati’s figure is in the same range as other surveys.) This approach to the game is probably not the best way to appreciate Salvati’s artistry, but it succeeds in raising its own questions about games and human behaviour. Namely: faced with an experience that many humans face, how will our stoic videogame narrator react?

“Ooh,” says YouTuber Philofhatsandgames as the game’s first anxiety attack strikes. His face, which occupies the top-right corner of the screen, remains impassive. The sound of breathing becomes more pronounced—not Phil’s breathing, mind you, but that of the game’s protagonist. Alarming messages fly into the foreground: “I’m weak; I need help; I’m paralyzed; I’m powerless; Alone; I’m stuck.” Phil spins around, but the dark thoughts are coming from every direction. “It’s okay. It’s okay,” Phil says in an even tone. He goes silent for thirty seconds, long enough to notice the interval and start counting his blinks. His voice eventually returns, like Apollo 13 rounding the moon and coming back into contact. “Yikes!”

Phil gradually gets a handle on the game. As he does, his face loses its affectless quality. “That’s right, you’ll be okay,” he enthusiastically pronounces. Who is “you” in that sentence? Who is he trying to convince? Phil escapes his first anxiety attack and pronounces, “This game is not for the faint of heart, but I’m fascinated by it.” He’s less than eight minutes into his 26-minute video.

To watch Phil work his way through Anxiety Attacks is to reckon with the extent to which games can serve as therapy. “That’s right buddy, you can do it,” he tells the screen. This is both an encouraging and somewhat therapeutic thought. It sounds like something he might tell his avatar in any other scenario. The game is either affecting how he thinks about mental health or simply recontextualizing linguistic tics already associated with games. Either way, games and their associated media provide a forum for working through these issues in public.

Games provide a forum for working through these issues in public

It’s better to have Phil work out these issues than deal with them yourself. If he can do it, maybe there’s some hope for the rest of us. “That was Anxiety Attacks, guys. It’s not a good thing to have those especially when they’re severe,” Phil concludes. True. Before signing off, he adds: “Take someone with you when you go on walks.” He’s on to something there: We may all need a bit of help navigating life’s literal and figurative forests.

/////

I can’t tell you when I first lost sight of the forest for the trees. Maybe it was as a high school student, where the highs of travelling for competitions were usually followed by crushing lows. I’d occasionally scrawl notes to that effect and forget where I left them. The discovery of such notes occasioned all manner of awkward questions about what they meant, questions that I was never in a position to answer. I was a teenager—a subsection of humanity known for its lack of self-awareness and emotional fluctuations—who liked dark music. Maybe I was sad. Maybe I was parroting my cultural consumption. Maybe I was self-indulgent. I, of all people, couldn’t solve this riddle, which led to many variants on the following conversation:

“Are you okay?”

— “Of course I’m okay. Why are you even asking?”

I’m not okay.

Most days, I’m good enough. It just takes a lot of work. I’m exhausted. The minimum threshold for making it through the day is attainable, but I spend a lot of time thinking about. Its existence is more of a challenge than a comfort.

The real problem is not knowing what to make of these emotions

It’s hard to quantify the effect of living with anxiety and periodic bouts of depression. The occasional metric presents itself: The historic trends monitored by my phone’s pedometer serve as a diary of all the times I told myself I’d walk around the block to calm myself down before doing something. One lap becomes two becomes 10,000 steps before 10:00am. That’s as concrete as it gets. Everything else—the days spent without leaving unlit bedrooms, the menial tasks turned into crises, the emotional labour inflicted upon others, the trouble eating, randomly crying on the bus—is squishy.

If that all sounds like nonsense, I don’t really disagree. Most discussions of the symptoms of depression and anxiety tend to devolve into truisms: depression means sadness; anxiety means stress. These explanations have the benefit of sounding concrete. Tell someone you’re sad and they’ll know what you mean, or at least claim to know. But such truths are trivial. Everyone gets sad and stressed; the real problem is not knowing what to make of these emotions.

Anxiety and depression are, above all else, attacks on your brain’s ability to contextualize feelings and information. What’s the difference between a bad day and my world collapsing? Will I always feel this way? Will things ever get better? Is there something wrong with me? Does everyone feel like this? I can’t answer any of these questions. The difference between a momentary bout of sadness or anxiety and a prolonged crisis is, in large part, believing that the precipitating event is normal and that these things usually pass. Without that faith, or any understanding of what constitutes a minor setback, all feelings become weaponized. They fold in on one another, creating new and compounding crises until all points of reference are lost.

Image by Justine Warrington

Image by Justine WarringtonThis inability to contextualize feelings also makes it hard to contextualize actions. How am I to know if my bouts of laziness or inability to focus are products of my anxiety or a natural state of being. The same goes with my tendency to lash out at friends or abruptly cut off correspondence. I reckon with these questions on a daily basis, and spend even more time on this one: Why am I such an asshole? On the one hand, anxiety is a part of who I am. It will not be excised anytime soon. It is a part of who I’ll always be. Thus, to say it’s the anxiety acting is to let myself off the hook. There is no doer behind the deed. At the same time, I’d rather not be defined by my ailments. Anxiety is not all that I am, though it can definitely feel like it. I’d like to think that there is some separate part of me that remains untainted. So, to the extent that there is such a thing, which one is my ‘real’ self?

/////

One of the promises of interactive experiences, as extolled in both specialist texts and the general press, is that they offer a low-stakes venue for trying on different selves and new identities. You may be a nervous wreck of a white man offline, but you are under no obligation to be any of those things online. As the developer Jake Elliott puts it, videogames allow you “to explore a simulated space with no consequences. You can try on different behaviors, see the outcomes, and learn how you feel about it.” Players often take advantage of this freedom. A significant percentage of cisgendered male gamers, for instance, sometimes play as women in MMORPGs. Trying on different identities can be a way for players to distance themselves from their ‘real’ selves or to find such a thing through experimentation. The choice is theoretically theirs.

But online spaces only offer so much latitude. Even if they are under no obligation to do so, players often bring elements of their offline selves into games. “Even when we believe we are free and empowered, our offline politics and cognitive baggage prevent us from changing,” writes Ubisoft’s Nick Yee. Psychological studies, for instance, that all sorts of racial biases affect player relationships with their avatars. Many players badly want to leave their real lives behind, but it can still follow them into games.

Many players badly want to leave their real lives behind, but it can still follow them into games

This tension between the potential freedom afforded by games and the baggage that cannot be outrun is especially pronounced in games about anxiety and depression. How do you try on new identities when an emotional condition tinges everything? Is anxiety one of the things players leave behind or a part of real life that bleeds into games? These questions also apply to game creators and distributors. In the absence of concrete knowledge about the sort of promises that can honestly be made, the language used to describe games about anxiety is maddeningly imprecise. That’s how you get PR emails with subject lines like this one, which I received in September: “Can Video Games Help You Manage Stress & Anxiety?” Good question.

This question of how much games can really accomplish dovetails neatly—perhaps too much so—with talk of new technologies as tools for generating empathy. Games may or may not be able to help with anxiety, but can they help others understand what it’s like to live with such difficulties? This, in short, is the promise of virtual reality: by taking on different identities, you can better empathize with the experiences of others. In his popular TED Talk about VR, Chris Milk talks about immersion as a means of creating deeper and more meaningful empathy for others. TED calls the talk “inspiring.”

The talk may be inspiring, but how much understanding can an interactive experience—five minutes in a headset or a few hours in a game—inspire? Some knowledge is probably better than nothing, but it’s not yet clear how much better. Moreover, there is a considerable danger of overestimating the amount of information that can be gleaned from an interactive experience. This sort of faulty calculus turns empathy into erasure. Mitu Khandaker coined the perfect term for these faulty expectations of technology: “Magical Empathy Machines.”

There is no magic here. Understanding takes time and effort. Technology may expedite matters, but it is not a remarkable shortcut. This leaves everyone in the same boat, wanting to understand more—about themselves, about others. There are also many attempts to sate this demand. Amidst all this work and desire, the big challenge is finding a way to talk about what these offerings can and cannot do.

/////

There is no shortage of games about anxiety and depression. The past year and a half has seen an explosion of small, personal games, all of which sought to address this subject in their own way. These titles’ characteristics do not all overlap, but that is precisely the point. Specificity can serve as an antidote to generalized claims about empathy.

Zoe Quinn, David Lindsey, and Isaac Schankler’s Depression Quest is a game about depression (duh!) but it is more importantly a game about language. The second-person text-adventure’s player surrogate is known only as “you.” All relationships are mapped relative to you. You are at the centre of this story, but that doesn’t mean you are in control. The specific challenges you face are largely built into the game’s mechanics; there’s relatively little you can do to create or avoid them. Of course you can make things worse. You can always make things worse. This choice structure matches the game’s description of how depression works.

Depression Quest does not subscribe the narrative convention of “show, don’t tell.” It is a series of moving diktats: you feel this; you feel that. The game doesn’t trust you to piece together the leaps made by a brain that is in crisis, and why should it? The whole point of the exercise is to map out the sequences a depressed mind runs through. These sequences aren’t logical per se but they have an internal logic. One thing leads to another and before you know it, you’ve spiraled into a pit of despair. There’s some good news on the other side, but you’d be lucky to break even in the end.

Nicky Case’s Neurons is perhaps best understood as the story of Depression Quest told from a different perspective. Neurons also maps out the linkages made by a depressed brain. Instead of thinking of these connections in terms of words and scenes, Case diagrams them in accordance with the underlying intuition of cognitive behavioural therapy. This approach to psychotherapy views depression as the product of linkages between stimuli and feelings, behaviours, and thoughts. Those connections can be reprogrammed over time. Neurons has you do just that by clicking away and introducing new stimuli and linkages. This is what characters in Depression Quest are hinting at when they encourage you to seek help: your context is all broken, go make those new connections. This is much easier to do in the context of Case’s interactive diagram than in the midst of a crisis, but the underlying intuition is the same.

Of course, depression and its cousin, anxiety, make much more sense in purely intellectual terms. One can suffer from many of their symptoms and understand what they mean in the abstract without being able to put this information to use. In practice Case’s cognitive behavioural therapy approach takes time, and lots of it. You don’t simply pass a test proving you can draw the diagram of how different stimuli are linked on the back of a napkin; you actually have to reprogram your thinking. Interactive experiences don’t really exist along that time horizon. Games can hint at how that process works, as Neurons does, or show why it is needed, as Depression Quest does, but they are not standalone forms of therapy.

Understanding how depression works, however, leaves the player a long way from knowing what the condition actually looks like. Is it just a bottomless pit of blackness, or does it take on an altogether different appearance? This question is at the heart of Open the Door and Smile, a game created by Arne Bezuijien for the 33rd Ludum Dare games jam. The game attempts to put you in the shoes of a woman in the midst of a custody dispute with an abusive former partner. This state of affairs sends her into a spiraling bout of anxiety. Unlike Depression Quest, Open the Door and Smile renders its protagonist’s world in 3D Space. This graphic choice affects the game’s language; whereas Depression Quest is constantly telling ‘you’ where you are, Open the Door and Smile uses visuals to situate the player, allowing the narration to proceed in the first person. As the game’s protagonist spins around her apartment in search of pills and peace, the walls tessellate and turn into razor-sharp shards. At first, this feels like a rendering bug. Over time, however, the distortions of Open the Door and Smile’s built environment come to match the state of its protagonist. This is not what the apartment actually looks like, but it is what it looks like for her.

(The apartment is not the only place Arnage blurs the line between performance glitch and narrative technique. My award for best update note of the year goes to the latest version of Open the Door and Smile for “Fixed a bug that caused severe performance drops when the player reached high stress levels.” In a game about anxiety, is that really a feature or a bug?)

You cannot know what it is like to be any of these protagonists from these titles’ combined playing lengths. There is obviously more to their struggles than can be fitted into a game. That reality does not, however, preclude learning something along the way. Depression Quest, Neurons, and Open the Door and Smile are all attempts to think about the different forms of reasoning one engages in while suffering from depression or extreme anxiety. These are not comprehensive trips into the brains of others, but they are diagrams of how their brains work. If nothing else, it’s a start.

The differences between games about anxiety and depression are as instructive as their commonalities. The most common difference is the triggering event for each episode. Neurons is a purely theoretical exercise, the fear of an abusive partner and losing one’s child triggers Open the Door and Smile, and past traumas lurk beneath the surface in Depression Quest. Indeed, a game can examine triggers without putting you in the shoes of its protagonist. Manos Agianniotakis’ An Interview turns a man’s story of depression into a third-person interactive feature. There are text prompts to click, but they accomplish nothing. This is the protagonist’s story; you may want to change its course but that is not your place or within your power. The sub-genre of games about depression and anxiety does not come anywhere close to covering the full range of potential triggers, but the mere existence of diversity within the genre is a useful point in and of itself.

Each of these games combats the platitudinous nature of discourse around mental health by telling one specific story and not attempting to stretch that story past its limits. By dint of these stories’ limited scope, they also have limited explanatory power; they tell you some things about depression or anxiety in certain scenarios and nothing more. Depending on the player’s imagination, this may be enough to generate a more generalized sense of empathy, but there can be no guarantee of this outcome. As with Case’s diagram, everything depends on how you connect the dots.

/////

Every Friday, the psychotherapy group meets in the basement of a building that can only be described as brutalism’s lowest moment. It has no windows and the heating only works at the most inopportune moments. The group doesn’t need any further reason to fidget, but the environment obligingly provides one anyhow. There’s a filing cabinet in the corner of the bunker. As best I can tell, it does not contain a single file but does an excellent job propping up the Kleenex stocks, thereby justifying its continued existence.

The advantages and drawbacks of group therapy tend to be evenly balanced. In return for the ease of booking an appointment, you have to accept that much of the session will be spent on concerns that have little relevance to your life. The answer to “why can’t I give public speeches” interests me as little as “why can’t I get out of bed” interests some of my peers. That’s the deal we’ve all made. The real benefit of the group session, however, has very little to do with the actual questions and answers. There’s comfort in looking around a table and seeing people who are dealing with similar issues. I don’t wish any of their difficulties on them, but it is nonetheless reassuring to know that there are other people out there dealing with similar issues. The presence of others is the closest I get to contextualizing how I feel about life and answering my recurring questions.

There’s comfort in looking around a table and seeing people who are dealing with similar issues.

This group therapy dynamic also describes the last eighteen months of games about anxiety and depression. All of these works are in conversation with one another, but messily so. They talk past each other, raising their own issues and searching for their own answers. Artistically, they fidget in a difficult climate. Yet the existence of all these faces around the table is nonetheless helpful. Even when these games are talking past one another, they contextualize each other by virtue of their existence.

I don’t want to be happier. I’d gladly settle for that, but it’s not a real goal. Instead, I only wish for a bit more perspective, just enough to get through the day with a minimum of fuss. The same is needed from videogames: A little more perspective on what they can and cannot tell us about others or ourselves. As in other media forms, anxiety and depression aren’t signs of artistic seriousness—you can be a serious artist or author without these afflictions—but they are challenges that should be taken seriously. We now have enough games to form a group therapy session and hope some greater context comes of the exercise. That context is needed—it is one of the few areas in which I am confident of not being alone.

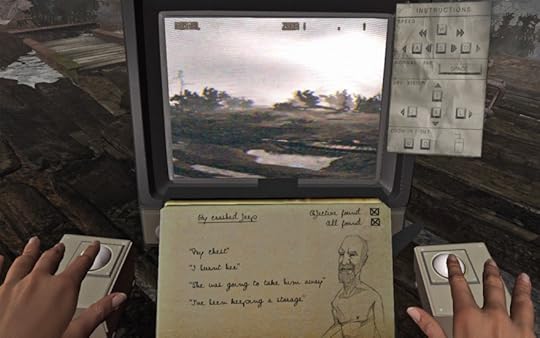

Sylvio 2 and the ghostly terror of analog technology

Sylvio was a humble ghost-hunting horror game in the foggy, abstract lineage of Silent Hill. It also boasted an indelible protagonist in soft-spoken Juliette Waters. Her resolve through all manner of supernatural phenomena makes you, the player, feel a bit better about the screaming ink-black blobs milling about as you investigate an abandoned amusement park. Using EVP recording equipment, you can capture the whispers of the dead on analog tape, scrubbing back and forth to pinpoint clues about how each spirit met their end. Yeah—Sylvio is a game about helping ghosts find peace.

Now designer Niklas Swanberg is back on Kickstarter with Sylvio 2, which swaps the tape machine and amusement park for a video camera and a gnarled, misty open world. Check out the new trailer premiering below, and then read Swanberg on horror, Twin Peaks, and Ingmar Bergman.

///

Kill Screen: My first question is simple: Why do Sylvio 2 ?

Niklas Swanberg: When I was in the last year or so of finishing Sylvio, the story was set. I couldn’t add anything to the game, or I wouldn’t have finished it. I really just needed to discipline myself out of the creative zone and force myself to finish. You know, fix bugs, create GUI, make stuff logical for a player. But new ideas kept coming nevertheless, and by the time Sylvio launched, I had a skeleton for a sequel living in my head.

I am very fond of that park, the concept, and the main character. I believe there is so much more content, characters, and situations yet to explore, and that’s why I feel it has to continue. Also, I feel the communication with both the living and the dead can go so much deeper than in the first Sylvio. In Sylvio, there was a point in keeping Juliette isolated, but now I’d like to occasionally break that isolation and give her direct social interaction, which means more focused objectives and situations.

you’ll just have to tolerate that it’s happening to you

KS: What’s behind the switch to video? Can we expect any found footage elements to sneak in?

NS: The reason is to deepen Juliette’s communication with the spirits, to deepen their story and their characters. I am also very interested in experimenting with movement, how a spirit moves in different speeds in different parts of the recording, where it goes, how it moves, why it moves. It can be a part of puzzles, it can tell you things that speech can not. Lastly, I believe it gives the player a sense of presence to have their movement, zooming and panning recorded, while they record the sounds. It’s still very much in the experimental state, but I’m very excited about it as a concept.

I am intrigued by the found tape concept, but I don’t think it would be a big part of the story. It would be fun to find VHS tapes of something like a children’s show though, or lost family vacation footage. Just as an extra.

KS: What’s scary to you?

NS: When a familiar situation becomes unexplainably unfamiliar, that’s horror to me: when logic tells us something should be one way, yet it’s another, and there’s no way to control it, and there’s no way to predict what will happen. That’s why I enjoy horror games from other cultures; I can’t read the words in between the lines, so I’m all alone with what’s happening. But when I see a film from Sweden or the US, I can always rely on my past film experiences, or my knowledge of acting, or anything else familiar in the setting to explain the situation. I believe all horror must always strive to be unique and original, in order to place the viewer somewhere unsafe.

KS: Do you see Sylvio to be a straight-up horror game or does it simply deal with the supernatural?

NS: Even though I know Sylvio is technically a horror game, in my mind I like to see it as just a game. A game that has disturbing parts, and darkness pounding beneath a calm exterior. It’s realism, but evidently there’s something supernatural going on. But you can’t really be sure, you know? Nothing is for certain, you’ll just have to tolerate that it’s happening to you, and hopefully eventually you’ll understand why, unless you lose your mind first. It isn’t there to be scary, it’s just simply there.

that game’s calmness inspired Juliette’s character.

KS: You mention film; is there any cinematic DNA in Sylvio 2 ?

NS: That depends. The foggy, grey look, I think is very cinematic. A bit like an old Bergman film, maybe. I remember watching the cinematic trailer for The Witcher 3, before there was any gameplay footage at all, and I remember being so pumped up. Not because of the graphics—I knew they were prerendered. But in my naivete, I thought the whole game would have that colour palette to it. Later, when I saw how the game actually looked, I was really disappointed. I mean of course it was beautiful—the trees, the skies, the winds, all beautiful. But it was just so colorful, it was exactly what you expect—I’d wished for the whole world to be that dark grey, muddy and hopeless.

As for cinematic in any other sense—the sound design and musical scores, yes, very much so. Some of my absolute favorite all-time scenes are the dream sequences in Twin Peaks. The way they used backwards speeds to manipulate the voices—I just knew there had to be a way to use it in a game. It all came together after combining speech in different speeds with the diffuse quality of EVP recordings, and giving the player the playback controls. I knew I’d found something different, and the audio recorder became the core of Sylvio. So naturally I had to make my protagonist an EVP recorder.

KS: Who or what inspired Juliette? She’s such a unique character, from her quiet voice to her profession.

NS: Many years ago I played a game called Broken Sword, where the protagonist was a female journalist. She spoke in a French accent, commenting everything around her and I just fell in love with the mood in the game. I think a lot of that game’s calmness inspired Juliette’s character. Also, I don’t believe in putting emotions on players by telling them that the character is afraid, like using hard breathing or angry speech. The effect is much stronger if the player is alone with his or her feelings. I wanted Juliette to be strong, intelligent, and calm, because that’s a bit rare for a female character in games.

You can support the creation of Sylvio 2 over on Kickstarter. You can download the Sylvio 2 prototype on itch.io.

Speak Up, Off-Peak

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Mad Max. Fallout 4. Star Wars Battlefront. In a year of stunning videogame landscapes—or at least landscapes that are mildly pleasing, so long as you enjoy dull, pretty pictures—Off-Peak, by Cosmo D, is exceptional. Its train station cum art gallery is an evocation of art versus functionality, of a world and an industry where talented creators are trained to become commodities.

Musicians are gathered here. Artwork and posters adorn the walls. Above you hangs a life size sculpture of a blue whale. Around you, people of all shapes, sizes and skin colours sip coffee and converse. But you, a true free spirit, roaming the station at your pleasure, searching for truth in the form of scattered ticket pieces, are not welcome. The station’s owner is watching you and is displeased. When you reach the upper floor, collect your ticket stub, and turn around, a team of identical, suited, albino spies is glaring directly in your face. This is a place for artwork and expression, but it’s a place, also, for people to clock routinely in and out of work.

this is what I see in videogames, not just this year, but every year.

And just as the images and sounds emanating from the station disguise its industrial purpose, your exploration is either displeasing to the station’s management or, in the case of the albinos, a kind of job interview—they notice in you a kindred spirit, and carry you off to join their collective of ostensible free-thinkers. Expression in Off-Peak is not true. Shady upper forces seek either to curtail or assimilate it. You believe you are finding your own way home, but your search through the station is part of other peoples’ machinations. One way or another, they want you to fall in line.

And this is what I see in videogames, not just this year, but every year. I see genuinely talented people corralled into working on humiliatingly simple games. I see expression and creation discussed in the most menial and reductive terms, with “story” and “characters” treated like components in a machine. I see a functioning system, a pure business, hiding its grey self-perpetuation behind emotional hyperbole and the occasional flicker of artistry, praised and awarded beyond all proportion. Large, industrial, and designed in almost every respect to help maintain routine; videogames are a train station.

And the enthusiast press, self-congratulatory award ceremonies, and blithe videogame positivity, which stems from a few cheaply emotional, poorly written independent hits, are the posters and sculptures adorning it. Genuine artists do exist. Cosmo D is certainly one. Will O’ Neill, Silverstring, and Jallooligans are but a few others. However, Off-Peak warns of a culture—or maybe something broader than that; maybe just a tendency in people, generally—to label and compartmentalize, to “use” artwork in the way one would use an appliance.

One school of game-making treats creation as design, and games as consumer electronics. Another is unthinking and masturbatory, so determined to find worth that it will adore even the limpest work, as long as it has represents vaguely an alternate future. Off-Peak announces our longing for uncontainable expression. Regardless of what you create, it believes there is nobility in pure artistic vision.

You can download Off-Peak over on Game Jolt.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers