Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 181

December 17, 2015

The consumerist zenith of Star Wars: Card Trader

When asked about the origins of Star Wars at a Sundance panel earlier this year, George Lucas didn’t describe a mystical story some muse had moved him to tell. Nor did he frame his films as an epic family soap opera he was inspired to get on celluloid. Neither did he delve into the many filmic influences behind the movie, from westerns and WW2 dogfighting films, to samurai flicks.

Instead, his answer was about the ownership structure of the movie and how he financed it in a deal with 20th Century Fox to keep the licensing rights. He then shifted into how he only started to realize the franchise’s potential after the film’s release, when he discovered that “the big money was in toys.” Lucas had nothing to say on the deeper significance of Star Wars outside of the film’s commoditization as an entertainment product.

Star Wars is far less Calvin and Hobbes and far more Garfield

That’s not to begrudge any meaning that others derive from the fiction—witness the religious fervor swirling around “The Force Awakens”—but for me, Lucas’ explanation made sense. Star Wars has always been, above all else, something to buy, buy, and keep buying. Through the purchase of books and toys and videogames and cards, I’ve long come to accept—despite the pseudo-moralistic preachings of many of the film’s characters—that Star Wars is far less Calvin and Hobbes and far more Garfield. In fact, my most salient, lasting Star Wars memory is opening packs of trading cards as a kid and hoping I would get lucky and score a coveted rare card. Be these purely collectible cards, as printed by Topps; or the fantastically complex collectible card game created in the mid-90s by Decipher Inc. to compete with Magic: The Gathering.

Star Wars: Card Trader, a digital card collecting app from Topps released in March 2015, is the epitome of the Star Wars object obsession that began when Lucasfilm first struck deals with toymakers back in 1977. In the app, you buy packs of digital cards using “credits,” which can be purchased with real money; or you can earn credits by watching advertisements or downloading ultra-spammy apps. Like all self-respecting addict-feeders, Topps gives you 25,000 credits a day, or the equivalent of five free base packs. Whatever way you get them, the object is to build up a nest egg of credits to spend on a variety of packs that are offered on a rotating basis, each promising a shot at different variants of cards or “inserts”—special rare cards, packaged in sets (“Blueprints” or “Film Quotes”, for example), that are limited in their distribution and feverishly coveted by the community for about two weeks until everyone moves onto the next shiny thing.

The app is oriented exclusively toward consumption. Your peers are fellow hyper-nerds whom you communicate with in a code of arcane abbreviations via an in-app messaging system. No matter how much cash you drop, at the end of the day, you will need to trade with these people for what you want. This is both the main hook of the game, and its curse, because these interactions combine all of the pleasures of condescending Comic-Con jerks with the anonymity of a comments thread.

All you can do now is admire your jpegs

But in the end—once you have waded through enough ads and put up with enough obnoxious trade offers, or just straight up dropped enough money—you will have amassed a collection of often-beautiful (but sometimes ugly) digital Star Wars cards. And what do you get for all of your hard work? Nothing. All you can do now is admire your jpegs. There is nothing more to it than that; and the app pretends at nothing more. Now you understand the Star Wars game.

The app started out with a rabid niche community that has since gotten a bit out of control, spawning a vigorous after-market. It hit its fever pitch in August when iO9 ran an article about how a “Vintage” Han digital card sold for $225 on eBay. (Yes, to clarify: a buyer paid $225 for a promise from an eBay seller that he would transfer a Star Wars jpeg from his phone to the buyer’s phone.)

Since then, the app has seen an influx of new users, and Topps has been struggling to find a way to gain control of the after-market and profit from it. The company has started, like Senator Palpatine, to corrupt its own magical ecosystem with increasingly gouging ways to monetize the user base.

Through incessant notifications, you are pushed at every opportunity toward purchasing credits to chase down that “rare” jpeg. Most recently, Topps has offered up the option to outright purchase cards—removing the thrill of opening packs, hoping for a “good pull”—a move that has infuriated longtime users, prompting many a declaration that the community is now dead. Enraged proclamations notwithstanding, I logged in to the app today and saw plenty of those purchase-only cards up for trade. This is, after all, the Star Wars franchise—the bench of consumers is deep; and the forgiveness is infinite.

Star Wars: Card Trader serves up a distilled shot of the lifeblood of the Star Wars franchise. It is a perpetual, compulsive reason to look at and purchase Star Wars objects every day. We’ve had action figure bobbleheads, Blu-Rays, digitally remastered downloads, Lego sets, trading cards, and now digital trading cards.This latest iteration is the ultimate collector’s toy, frozen forever in packaging, there only be looked at, to be had just to have it, but to never be played with. They are only more minarets for the onanistic cathedral of Star Wars and yet serve as synecdoche for the entire franchise.

Elvie: The exercise game for a happy vagina

Between getting an education, working full time, taking care of kids and being reminded by society to look good while doing it, the pressure of being an independent woman in this day and age can be overwhelming. Luxuries like heading to the gym or taking a jog often get put on the back burner so you can get in some overtime or study for finals. But personal health, at least in one area, doesn’t need to take the backseat any longer: say hello to Elvie—the workout game you play with your vagina.

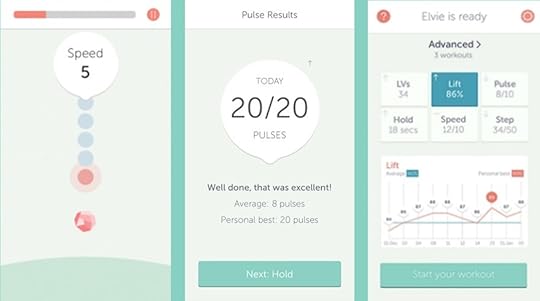

Elvie is a silicone exercise device connected via Bluetooth to an app on your phone, which instructs you through a series of games and exercises. The controller, an oval stress ball of sorts, is inserted into your vagina discretely, so you could perform exercises as you go about your day. Kinda takes multitasking to a whole new level, huh?

In one game, the app instructs you to perform kegel exercises in time with a bouncing ball on your screen, which mostly involves tensing and relaxing the pelvic muscles in different ways. In another, you must keep pressure on the controller to keep the ball floating on water. It’s a series of minigames, designed for keeping your hoo-ha happy. Your twat will be terrific. Your vajayjay will be a-okay. Alright, I’m done.

Keeping your hoo-ha happy.

The Elvie was created by Tania Boler, a London women’s health professional, who designed the device after the birth of her child four years ago.”I had a baby four years ago and had no idea how much change our bodies go through,” Boler said in a piece by Broadly. “My husband is French, and in France the motto is ‘Happy woman, happy baby.’ Women take more care and attention in healing themselves after birth [there].”

Kegel exercises are a treatment and preventative measure against uterine prolapse, in which the uterus shifts from its position. Nearly 50 percent of women experience uterine prolapse after childbirth.

“Most people think that this is a health issue or a sex issue,” Boler said. “Yes, it is both, but fundamentally this is a women’s issue, because women don’t know much about the importance of looking after this part of their bodies.”

So, come on Superwoman, you can do it! Can you feel the burn? (Though, realistically, if you’re feeling burning down there, you should go see someone about that.)

You can find out more about Elvie on its website.

The Year in Space

“Why Is NASA Exploring Pluto?

NASA sends spacecraft to other planets because exploring space is exciting.”

NASA Educational Technology Services, 2015

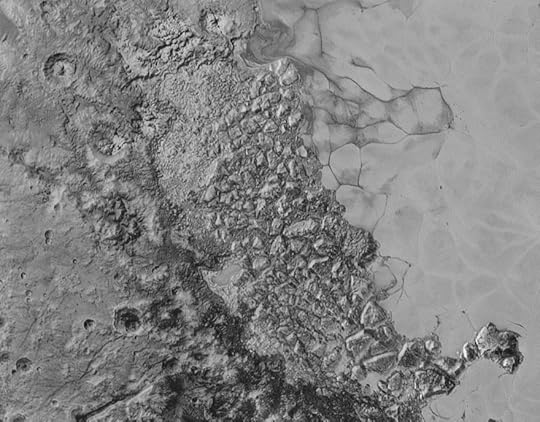

The Sputnik Planum,

Pluto

It emerges out of the ancient, cratered highland of the Viking Terra like a great lake, rippled with vast waves and sectioned into polygonal pools. It is of course, exceptionally dry, though hills of water ice rise up in aligned ripples like the rake marks of a zen garden. It is young, at least comparatively so, like the cheeks of a child yet to be marked with the scars and pockmarks that life accrues. Its cell-like structure is derived from the convection caused by the methane ice that lies below the thin surface. Glaciers of nitrogen flow out across it, pooling at the base of mountain shorelines like crystal oil slicks. Somehow both macroscopic and microscopic, the textures of the planum look almost as if I could reach out and run my fingers over them, the geological formations protruding through my screen as the final millimetres of a journey too vast to imagine, measureless to man.

This is a distant reading, mediated through the long-range reconnaissance imager and visible imager that protrude from the gold-wrapped body of the New Horizons probe. In January 2015, after waking from its long hibernation, the probe began its approach towards the dwarf planet Pluto. Over the course of the year it has gathered a portfolio of imagery which has crawled its way back to Earth at a rate of 1 kilobit per second, to be disseminated, multiplied, uploaded, edited, analyzed and proliferated across our many networks. There is an odd sense of ease to this process, as images of a distant planet jump readily up our news feeds, maps of alien landscapes finding themselves among the company of gossip and news, the real and the imagined.

The view from orbit is tempting, alluring, its power residing in its distant mystery

Over the course of the year, these images, and the geological features they depict, have become oddly familiar—not on a named basis, but present nonetheless, at the corners of our vision. Space exploration has been a constant feature of the news, this steady stream of images from New Horizons, depicting the underworld of Pluto and Charon, augmented by a handful of other missions and discoveries. This constant presence has somehow further muddied the real and the imaginary—with no human reference point, these machine-made images slot easily into an ecology of other machine images, computer visualisations, event simulations, test renders, “not representative of gameplay” CGI and procedurally generated worlds.

This process moves towards obvious ends—we will soon be able to pick our way across the Sputnik Planum, gazing out across its vast, untouched surface. Elite Dangerous: Horizons, an expansion to the space trading sim that seems unlikely to have been named by coincidence, adds planetary landings to the game’s map of the universe. As this map includes our home system of Sol, it is logical that over the next months Pluto will be opened up as a possible landing point. It’s worth considering that Elite Dangerous has already taken the images of Pluto captured by New Horizons and wrapped them around its in-game model, the Sputnik Planum clearly visible on the face of the distant dwarf. Like Jean Baudrillard’s iconic image of the “map that is the same size as the territory,” the referent eclipsing the original, what is the effect of one image slipping on top of another? A pixel-thin skin sent back from space recontextualized as a simulation of the object itself. The view from orbit is tempting, alluring, its power residing in its distant mystery. Touch down and the dusty rock is dead, the Sputnik Planum is just another “desert of the real.”

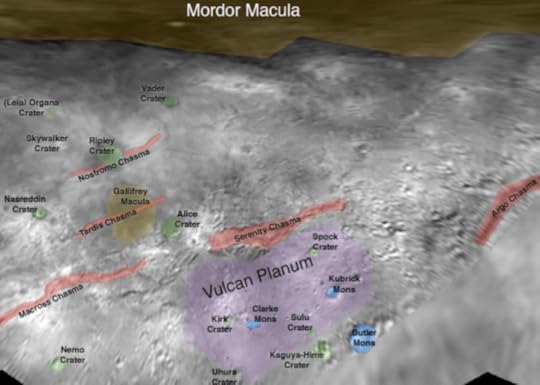

The Nostromo Chasma,

Charon

This split in the surface of the moon spans out from the Ripley Crater in both directions, as if the ancient impact had burst the frozen skin like that of a ripe fruit. The floor of the chasm is often in shadow, concealing the deposits that lie there among the shards of ice and perhaps a light dusting of snow. It is nothing more than a scratch on the surface, not coming close to reaching the rocky core that is encircled by an underground ocean of perpetual dark. Beyond that point there is nothing to be taken here, nothing to be exploited, the chasm is a barren scar.

However, the chasm’s name is a source of something richer, a set of connections leading into another core. Nostromo is a name shared with Ron Cobb’s iconic design from Ridley Scott’s Alien. A hunk of industrial architecture, crawling across space, a refinery floating in the void. It is an image that has started to take on a hint of reality, in the flowering of companies like Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources. These corporations, which at first appear to be fanciful entities, have already begun to set out the first plans for industrialised space, for their own Nostromos. This year NASA revealed further partnerships with these private mining companies, designed to boost the flagging budget for space science.

The Imperialism of Nostromo is not a feature of the past

And there is another Nostromo, the one from which the ship took its name. Often considered Joseph Conrad’s greatest work, it follows the fortunes of a mining colony in Latin America, the fictional Costaguana. A critique of imperialism and its central driving force of material gain, the story revolves around a final haul of silver from a colonial mine that is tied up in the political upheaval of the indigenous people. Through distant in time and place, there is something potent about these associations. Nostromo is a man, once a rebel and perhaps a hero, who is unable to escape the imperial desire to take from the land for the ceaseless pursuit of personal fortune.

Mere months ago, the U.S senate legalized the mining of celestial bodies, marking this year as a historic turning point in the industrialisation of space. Though the planets and asteroids themselves remain unable to be claimed by one government or corporation—“the common heritage of mankind” as decided in the outer space treaty of 1967—their contents are now the property of whoever extracts them. This heritage, then, is now a universe of husks, empty signifiers of what were once worlds. When Asteroid 2011 UW-158 passed the Earth this year, it did not appear in the news as a threat, or a scientific curiosity, but instead as a resource, its platinum core being reported to be worth $5 trillion. Even the landing of the Rosetta on the Philae comet came to symbolise not just a unique achievement in human history, but a test case for the concept of landing a mining vehicle onto an asteroid. The Imperialism of Nostromo is not a feature of the past, but a future, a continuation of imperialism beyond the “final frontier.” That term, so popular when evoking the romance of space exploration, also betrays the colonialism implicit in the process of human expansion. It is the victimless crime, the discovery of a territory without an indigenous people, without politics, yet it can’t help but represent—much like the greed that overtakes the idealism of the man Nostromo—a cursed enterprise.

The Cthulhu Regio,

Pluto

It was once known as the whale, a dark expanse, growing steadfastly across the planet’s surface. In reality it is a vast tar slick, its hydrocarbons formed from chemical reactions catalyzed by cosmic rays. Readable across its tenebrous surface are the ringed edges of craters, betraying its ancient form. It has seen hundreds of millions of years of sunlight, though the planet it covers has yet to make a single rotation of the sun in the time we have known it. Its darkness is a site for speculation, a container of mysteries unable to be simulated.

There is something pleasing about the naming of the Cthulhu region. Taken from the publicly voted list of names submitted to NASA—which also led to the moon Charon’s spate of science fiction names such as the “Vader Crater” and “Tardis Chasma”—it continues something of a tradition in the mythical names of celestial bodies. More than that, it represents the mystery that is easy to project on the objects of space exploration. H. P. Lovecraft’s creation is the ideal symbol for this mystery, an ancient malevolent being that is worshipped as well as feared. Though this year may have marked a key stepping stone in the instrumentalization of space travel as an industrial pursuit, it has also seen a rise in the public desire for space to be an evocative place of mystery and darkness.

we had an entire history of imagined realities to take from

Fueled by the media, but eagerly received, there have been many cosmic mysteries in the year’s news. The Ceres bright spots, discovered by the craft Dawn, was one of the objects of speculation, but even more notable was the distant star KIC 8462852. Discovered by the Kepler telescope to have a dramatic and inexplicable dips in its light emissions, the idea of an “alien megastructure” was presented as a possible explanation. The theory went that nothing natural could be blocking the star’s light so significantly, leaving structures made by sentient beings to be the only explanation. Widely propagated online and in print, it was easy to tap into a collective imagination of vast alien spacecraft, glinting against a distant sun. From Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama to Mass Effect we had an entire history of imagined realities to take from and to fuel the always scare-quoted phrase “alien megastructure.”

Though it was clear that this explanation for KIC 8462852’s unique traits would ultimately fall short of our imagined explanations, there was a certain kind of willingness to engage with the idea. It was as if we were all happy to let fiction and fact bleed easily across each other, to live for a moment in the muddy waters of not knowing. For a decade marked with irony and cynicism, it seemed almost as if a desire for naivety was being enacted on a large scale, one that perhaps hadn’t been associated with space exploration for decades.

Perhaps it is the case that the idealism that comes with space exploration is harder to kill than we thought. In fact, in some sense we can see this idealism being mobilized in the pursuit of our imagined dreams. Both No Man’s Sky and Star Citizen have, this year, felt as if they were trading entirely on the promise of space rather than the actuality of it. Star Citizen in particular, having raised funds through pledges that reward players with exquisitely detailed ships for a game which has yet to be released, seems to demonstrate the monetization of optimism. It is no coincidence that both of these games are depicting space exploration, when it is clear that it remains one of the last reservoirs of unfulfilled digital dreams. As a culture our desire to blend the real and the imagined is easily exploited. Our ability to envision powerful visions of future experiences, along with our desire to escape this earthly cradle, drives us to see these games as transformative experiences. It is not that Star Citizen or No Man’s Sky are scams, it is that, for the time being, they have yet to become actual objects, and so in an imaginative sense are unlimited. Like the surface of Pluto as transmitted by the New Horizons probe, these are untouchable ideals, as marked by distance as anything else. The moment we set foot within them, however, they become, like Pluto itself, unavoidably real, filled with a catalog of problems, a quotidian lifelessness and a distinct lack of higher meaning.

Yet, while this optimism is easily exploited, it is perhaps the only remaining way to champion space exploration as an endeavour. This year Interstellar tried to marshal environmentalism as a reason to escape the Earth, while The Martian turned to humanitarianism as its motivation for collective space missions. Both seemed to fall on deaf ears, neither reinvigorating the idea of space exploration as a viable endeavour. Instead the grainy images of Pluto’s distant surface, one which no living eye will ever see, became more compelling than their airbrushed counterparts. These imperfect visions became more potent canvasses for our ideas, perhaps because of their untouchable nature, their irresolvable mysteries. If this energy is allowed to be shuttled into the release of Star Citizen, No Man’s Sky, and Elite Dangerous: Horizons next year then an opportunity will have been missed. Equally, if support for the industrialization of space only grows with this year’s discoveries, then something will have been lost. These dreams borne of distance will only evaporate when they are revealed to be limited in scope, scale, and function. The only way for them to continue is to forever be directed outward, at unachievable aims and ever-retreating objects. Perhaps No Man’s Sky alone might have the opportunity to serve as a conduit, a catalyst for dreams of space rather than an endpoint. But instrumentalization has many forms, and all are incompatible with the wide-eyed optimism needed for space exploration. There is no need to lie—going ever deeper into space is not a chance to save the planet, nor to fulfill our species, or form a common bond. It is simply a chance to dream without limits.

All space photos credited to: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Help a whale on stilts find a new watery home

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Flewn (iOS)

BY GABRIEL SMETZER

Arriving at a topically relevant time, Flewn is about the search for water. More specifically, it is about a whale journeying across the desert on stilts to find a new oceanic home. With its storybook aesthetic, Flewn is less about interactivity and more of a display case for the gorgeous art style and allegorical tale. A long time ago, when the whale watched as disaster destroyed his homeland, he saved as many sea creatures as possible. Now, it’s up to him to find them all a new place to live, as he treks across the most dangerous environment imaginable for a marine animal. Aided by friends like an adorable frog named Frog who flies a unicycopter, Flewn is about taking a leap of faith to find something bigger than yourself. With mechanics similar to Simogo’s narrative iOS games, it mostly consists of side scrolling through the world and meeting colorful characters. However, there’s also a mode from Frog’s perspective, which adds the element of an unwieldy flying machine.

Perfect for: Marine biologists, animators, Simogo fans

Playtime: Twenty minutes

Remembering the beautifully boring MMO Star Wars Galaxies

There aren’t many games where the player can be a club dancer, strapped-for-cash and performing for tips in a sleazy bar. There are fewer where that bar is filled with fish people and space bears.

When Star Wars Galaxies first released in 2003, it did so under the tagline “Live in the Star Wars Universe.” A simple slogan that could initially be read in a number of ways, but one that turned out to be diametrically opposed to the rest of the Star Wars game library over the title’s lifetime. As opposed to the epic quests of games like Shadows of the Empire or the previous year’s Jedi Knight II, which could perhaps be summed up with “Save the Star Wars Universe,” Galaxies billed itself as a more personal take on the familiar space fantasy world. Players could still play out those movie-inspired dreams of being smugglers or bounty hunters, yes, but these more glamorous callings were only able to succeed because of the player-driven socioeconomic systems propped up by a whole in-game society stretching far beyond the fantasies of kids playing Han Solo and Boba Fett in their backyards. As the motto implied, this was a large-scale world inhabited by players who, if they so desired, could simply live meaningful lives on the small scale. In a way, Star Wars: Galaxies was the Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru simulator we never knew we wanted.

Rather than relying on a simple variation of the basic warrior/thief/mage class structure so common to other games of the same type, Galaxies instead debuted with a multi-tiered profession tree of over 40 different jobs, each of which could be mixed and matched to a player’s content so long as they had enough skill points to invest across them. Among these jobs were combat professions like commando or Teras Kasi Artist, but also titles like politician, chef, musician, tailor and image designer. Players who didn’t like the idea of adventuring through the mud could instead focus on running cities, cooking healing items, helping other players with status-improving songs, crafting clothing, or changing the look of other players’ characters … all for a fee, of course. Those who were good enough at it could even open up stores of their own and become famous as brand names. It wasn’t uncommon for combat-oriented players to have a trusted armor guy or spaceship parts guy, regularly making pilgrimages to their shops, which were all set up in player-built housing within player-built cities, which were themselves run by a mayor who could take taxes as needed. You could essentially open a mall in the Star Wars universe, which proved to be more compelling than you might think.

This was because Galaxies didn’t rely on non-player characters to fulfill the more mundane roles of its world. Many massively multiplayer games have crafting systems, of course, but Galaxies’ was more expansive than most. Whereas crafting in World of Warcraft is essentially a side-activity meant to provide players with a few small bonuses that quickly become outpaced by higher-level loot earned from fighting bosses, Galaxies’ crafting system was the best way to earn many essential items, from weaponry to vehicles. If someone wanted the best armor in the game, then they went to a player armorsmith, not a dungeon. If someone wanted to re-customize the look of their character, then they went to a player image designer, not a computer-controlled stylist. If someone wanted to buy a droid (Galaxies’ answer to the pets of other games), then they went to a player engineer, not a non-player breeder. This lack of competition from non-player characters forced players to rely on each other for goods and services, creating a robust player-driven economy that gave crafting or service-based characters as much purpose within the game’s world as those toting guns. And nothing symbolized this economy more than the Cantina.

This was due to “battle fatigue,” a clever little tactic used by the designers to turn their watering holes into actual gathering places. As combat-oriented players spent more and more time on the field, they accrued various stages of a status effect that would reduce the efficiency of their attacks and make them more vulnerable to damage. Initially negligible, this battle fatigue would absolutely doom players who went too long without getting it treated, and the only way to do so was to relax at a Cantina. Watching any of the entertainer professions perform for a long enough time would not only cure the nasty ailment, but also replace it with various positive bonuses. This meant that Cantinas quickly became host to dozens of adventurers all watching the various performers on display, which in turn drew entrepreneurs. Scenes of characters from every class and race shouting reminders to tip your entertainers, hocking their wares, and advertising personal stores became common in Cantinas. The result looked right out of the films, but more than that, it had managed to create an actual incentive for players of all stripes to consistently get together in a single spot. This was an MMO with a bar scene.

This was an MMO with a bar scene

When I first picked up Star Wars Galaxies, I was still in middle school. I hadn’t yet grasped the shear appeal of playing as a Wookie hairdresser on Naboo who also serves as mayor over a small hamlet of various artisans just outside of Theed. I just wanted to blow shit up! My time was largely spent in various hunting parties as I worked up my marksmanship skills until I could become a bounty hunter. Along this path, I spent many hours recuperating from questing in Cantinas, and not only came to appreciate just how friendly the community was, having been brought together and encouraged to cooperate and swap stories by our shared battle fatigue, but also how diligent the entertainers were. I felt as if I had owed something to them because I took part in their services so frequently. I tipped generously, and when I finally did become a bounty hunter and needed a good way to earn cash for all my shiny new blasters and thermal detonators, I started up an alternate character as an entertainer.

I whipped up a Twi’lek dancer, started her off on Tatooine (I wanted to hear that sweet jizz music while I danced), and set to work paying off my bounty hunter’s equivalent to student loans. Unfortunately, as a newbie to the dancing gig, I quickly realized that I wasn’t attracting any customers. Being so low level, my dancing wasn’t able to heal battle fatigue or pass on bonus effects as effectively as the more seasoned entertainers, and I could only entertain one person at a time. Not to be dissuaded, I simply moved my act to the privacy of the Cantina’s kitchen area and started practicing until I was ready for the big time. At first, I was willing to grind this out manually, but after a while, I came to understand that doing so would have taken hours more than I had as a busy student. So I set up some macros, and for the first time ever, I left my computer on overnight to power-level a character. It wasn’t blowing up bad guys that gave me my first experience as a “power-gamer,” but dancing in a club.

The result of my “training” was a respected addition to the Mos Eisley Cantina scene. Because practically everyone in the Galaxies community required the service entertainers provided, we found ourselves rather appreciated by the other players. Tips weren’t mandatory, but few people rarely stole free entertainment. I quickly attracted a clientele and the creds started flowing in at a fairly steady rate. I even had a few regulars. Once, a guy actually asked me out on a date. When I told him my age, he politely apologized and left me to my business.

And that’s what it was: a successful business. Outside was a universe full of Rancors and AT-ST Walkers, but rather than adventuring, I decided to engage in local business. This may sound like the most boring way to experience Star Wars, but it actually made me feel something few other MMOs have: it made the world feel alive.

Raph Koster, the former creative director for Star Wars Galaxies, summed this up well when talking about the game’s early days for an article over on Gamasutra:

“But the game was shaping up…Players had formed governments…Entertainers were going on tour…People were building supply chain empires and businesses with hundreds of employees.”

an interconnected society of not only heroes, but also shopkeepers, hairstylists, and local bands

True, I didn’t abandon my bounty hunter. I wasn’t about to pass up a game that let me hunt down other players. But doing so did require primo equipment. Thankfully, I had my little side-operation to keep me funded. Being a bounty hunter made me feel like I was exploring the Star Wars universe, but being an entertainer made that universe feel worth exploring. If the recent Star Wars: Battlefront is a diorama of Star Wars, then Galaxies felt like a living, breathing world. It was full of players with their own individual playstyles and goals, each relying on people from different strata of society to help them succeed. This is where the tagline “Live in the Star Wars universe” took its shape. As a player in Galaxies, you weren’t necessarily trying to save the world. That was Luke Skywalker’s job. You were just an average person living one of any number of possible lives. You were part of an interconnected society of not only heroes, but also shopkeepers, hairstylists, and local bands.

This community was the real strength of the game. When Elder Scrolls Online launched last year, it did so with a storyline claiming every single player was the chosen one destined to save the world. Rather than have players work together, this framed them as competing for space to be the one great hero of destiny. By avoiding this, Galaxies allowed itself to do something rarely seen for an online space. It cultivated a friendly society where players relied on and appreciated each other rather than mocking each other. After all, you can laugh at the shipwright for choosing a crafting class all you want, but when you need a new engine part, who will you turn to?

This, unfortunately, didn’t last forever. In late 2005, in an attempt to compete with World of Warcraft, Star Wars Galaxies’ multifaceted profession system was dropped for something resembling WoW’s more standard classes. Players were encouraged to take on “heroic roles” modeled after their “favorite characters from the movies.” Jobs were consolidated, and with that, many of the characters players had created in their heads weren’t able to exist in this new world. Unfortunately, this backfired in what many within the community were calling a mass exodus to other, competing titles. Sony Online Entertainment stopped releasing official subscriber reports for the game, although hacked information placed the amount of players logged into a game on a typical Friday evening as being around only 10,363 by 2006. Players simply didn’t want to play as Not-Han Solo. Not every player wanted to be a hero. There were plenty of other games for that. They wanted to live in the Star Wars universe, not save it. And if their preferred life was dancing in a bar somewhere, they felt little reason to stay.

Hopeful, I stayed on after the release of what has been referred to as the NGE (short for “New Game Enhancements”) for a small while just to see where the game was headed. What I got in return was a once-beloved Cantina that had been rendered a ghost town and a list of bounty hunting jobs with no more players to challenge.

Feeling defeated, I eventually moved to World of Warcraft alongside the rest of my friends. It was a drastic shift, but with help from veteran players, I found myself warming up to Azeroth. It was filled with many of the same design decisions that bothered me in the NGE, true, but because it had been built around them as opposed to having them hastily stapled on top of a pre-existing system, they didn’t irritate me as much here. Rather than the confused patchwork that Galaxies had become, Warcraft functioned like a well-oiled machine, and kept me invested in MMOs until I chose to quit during high school to focus on my social life.

I watched quietly when Star Wars: Galaxies officially accepted its fate

I stayed away from MMOs for a long time after that, afraid of the drain that they could have on my free time. I watched quietly when Star Wars: Galaxies officially accepted its fate and shut down in 2011. But when The Old Republic was announced, my interest was piqued. “Maybe this one could do it right,” I hoped. “Maybe it can make up for what happened to Galaxies.” I knew it was unlikely, but it was enough to get me to follow the game. I didn’t dive in for a paid subscription at launch, but when Old Republic finally went free-to-play in 2012, I knew I had to at least give it a try.

For my first character, I decided to play a Sith Inquisitor. One of my biggest regrets from Galaxies was that I never really spent much time playing as an Imperial. Again, I was an idealistic kid, and my sympathies were with the Rebels. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown more attached to the particular aesthetic surrounding the Empire, if not their ethics. I was hoping playing as a Sith would help touch on what I had missed when I was younger.

Instead, what I found was the same structure I remembered from World of Warcraft, but dressed up in Star Wars packaging. The zoned off leveling areas, the “Bring me 3 space rocks” quests, the “kill 10 space boars” tasks—it was all familiar. Once I unlocked the Sith Assassin class, it became clear to me that I was simply playing a Rogue by another name. I tried again with the Imperial Agent class, hoping I would find a more inventive experience with a non force-user, but neither of these glamorous roles satisfied me as much as my dancer from Galaxies.

Rather than the multifaceted profession tree of Galaxies, where I felt I was able to create a character that I felt was cool, Old Republic’s classes had me feeling like I was simply picking from a small number of pre-made characters someone else thought was cool. The Galaxy felt small again, and I had little reason to stay.

The Old Republic is a fine game, but as an exploration of Star Wars, its connections to the series felt superficial. One of the most famous scenes in A New Hope is the early one in the Mos Eisley Cantina. Here, moviegoers saw bizarre alien races of all types simply having a drink in skeezy dive bar. The world felt like it had grit to it, and the room seemed full of possible stories. In comparison, my experience with The Old Republic felt pristine. There were no gathering places, and everyone was too busy playing Darth Vader to stop and acknowledge the smaller world around them. In a community full of hundreds of Sith, that weird werewolf sitting at the bar doesn’t get a name. We don’t learn that the guy with the V-shaped head blew all his money on salt and juice. We’re never told that the guy that looks like Satan is a war criminal with a particular taste for jizz. There’s simply no time for them, when every player is out to either save or conquer the galaxy. When these minor characters are cut out, the world ironically feels much smaller. The Galaxy doesn’t feel lived in, and with nobody for Luke to save, his quest feels pointless. This is something Galaxies understood.

In Galaxies, the people who would have been background characters in other games got to tell their stories. This gave us a new look at Star Wars from a street-level perspective, something the films had always hinted at with its underworld, but had never given the spotlight, choosing instead to devote the main story to Emperors and Princesses. By exploring the everyman of this sprawling world, Galaxies honored its source material while at the same time discovering a novel approach to exploring it. It gave its players the chance to be anyone they wanted, no matter how boring, and that proved to be far more attractive to its community than dressing up as Luke Skywalker and holding a plastic lightsaber.

December 16, 2015

This GLaDOS-inspired robot brings science to dating apps

As a young twenty-something, a small amount of my young adult life has been spent hovered around the phones of my friends, laughing as we collectively swipe right and left on Tinder. Being in a long-term committed relationship myself, I’ve never personally experienced the whims of Tinder, but its attached lingo and stigma have breezed past me in the conversations of acquaintances and their recurring stories of failed Tinder dates.

Thus comes NYU Interactive Telecommunications Program graduate student Nicole He’s “True Love Tinder Robot.” Put your Tinder-armed phone in front of the robotic hand and place your hands onto the skin sensors that lie in front of it, and the robotic hand will swipe through potential suitors for you, all depending on how your body reacts—or rather, how sweaty your palms get. An entirely fresh, yet unnerving way of exploring the app.

Not only does the robot swipe for you, it additionally speaks to you in the process. Inspired by the much-adored, passive-aggressive robot GLaDOS from Valve’s Portal, the robot flatly provokes you as it swipes away. The Arduino-powered robot beneath the eerie-looking hand speaks to you as it browses profiles, saying phrases such as “judge this person,” “determine if this person has any value,” and “can you see yourself spending your life with this person?”, and your body’s increasingly sweaty reactions give the robot its answers.

The True Love Tinder Robot got its start when He had the idea of exploring the notion of computers knowing us better than we even know ourselves. In this not-so-unrealized world, the computer has a better idea of who we should date than we even do ourselves. He writes on her project’s page, “In a direct way, the True Love Tinder Robot makes the user confront what it feels like to let computers make intimate decisions for us.” With sweaty palms, the robot questions why we even swipe right and left in the first place.

Test out Nicole He’s True Love Tinder Robot for yourself when it’s on display at NYU’s ITP Winter Show on December 20-21.

///

Photo from Nicole He, Vimeo.

Kommissar is an adventure through the language of despotism

It’s about the language. It’s always about the language.

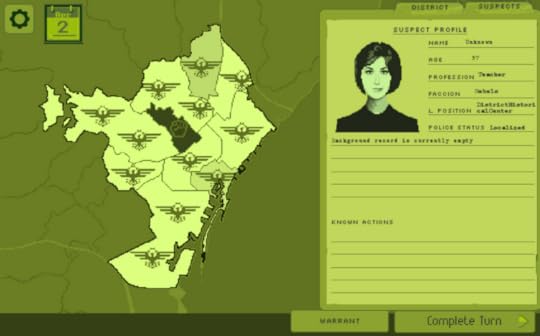

Kommissar is a text adventure masquerading as a thriller—and that’s a good thing. You play as an officer in the Ministry of Truth. This is a plum job seeing as it went to you, a child of the elite, and not some pleb. Suffice it to say this is not an equal society. To the winner goes the spoils, and you are spoilt with spoils. One of those spoils is the power to issue warrants. And do you ever issue warrants, directing investigatory efforts and powers of detentions to various quadrants of Roulettenburg. Sure you sit behind a desk, but you are in the seat of power. The people who carry out your orders are never seen; they are just pawns in this operation.

There are things to do in Kommissar—choices to make, strategies to devise—but most of what you need to know about the game can be gleaned from intertitles. You know where the whole thing is going when you are asked to send “peacekeepers” to areas where the government is losing control. Similarly, Beardserk’s description of the game—“a political prosecution thriller”—hints at the game’s sterile, bureaucratic doublespeak. This sort of Orwellian language is not original, but it takes on a slightly different meaning in the context of a game; there is more to this world than its language, but you can never escape the effect of these words. Indeed, it is only appropriate that all your power comes from warrants, pieces of paper with your signature affixed to the bottom. These are just collections of words, but Kommissar is aware that words matter.

The invasive power of bureaucracies is a timeless theme.

Cultural products about surveillance have to be set in a time and place. This is apparently a rule. Kommissar is therefore ostensibly set in the late 1920s, just like Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others is set in 1983. These works are about their time, but they also take on a more general quality. The invasive power of bureaucracies is a timeless theme. In that respect, Kommissar may be more timeless than most of its points of comparison: there is nothing obviously late-1920s about the game. If you didn’t know that’s when it was set, it could be any other time. Kommissar’s intertitles tell you all they can, but they can’t always shield you from the arc of history.

You can play and download Kommissar over on Game Jolt.

Voi wants to play architectural peek-a-boo with you

I like it when videogames play peek-a-boo with me. Yes, please, treat me like a toddler. I mean it. I am not yet beyond the delight of a magic trick; a spatial sleight-of-hand. And Voi has enough of them to warrant your curiosity. This is a game in which I spent a good five minutes going back-and-forth, side-to-side, reliving the couple seconds of the gif below in my own time, free from the never-ending repetition of the gif’s structure.

First you see a lengthy hallway, next you see a black void where nothing could ever exist. Where did the hallway go? Oh, look, it’s still there if I sidle back this way. How is that possible? Ad infinitum.

Naive as this sounds, I’m relishing the fading thrill of non-Euclidean architecture in videogames. And it is fading. Having been through what feels like an exam on the concept in Antichamber back in 2013, and then seeing its impossible structures and space-swallowing corridors cropping up in other games, the surprise of it all is getting lost on me. For example, apart from that conscious attempt to grok full appreciation of the not-corridor, I walked through Voi‘s puzzles with the confidence of a steam roller, flattening their solutions almost without thought. I’ve solved them before, if not in these exact formations, then at least the same components and programming tricks needed to make them possible.

a claustrophobic maze like a snake’s knotted stomach

Fortunately, Voi does have something else going for it: a stern, black-and-white posterior. Its temple feels holy in its hazy silence. You walk through it wordlessly to reach the top of its central pyramid, unlocking a staircase at a time. Each new tier that you ascend to and enter crossfades almost seamlessly as it transports you from the pyramid hub to a fresh set of puzzles laid out before you. First, it gives you doors and buttons, second comes bells and symbols, thirdly it pulls out invisible platforms and floor-sized reflections. All of this building you up to eventually face the game’s greatest non-Euclidean structures (including a claustrophobic maze like a snake’s knotted stomach) as if an otherworldly ceremony, a rites of passage.

Tonally, it’s flawless. But otherwise it’s a proof-of-concept that needs to go much further to deliver a hefty punch to the old cogs clicking in my brain, or better yet, to have me sat before my monitor agape and astounded at some new architectural hypothesis. And, thankfully, that’s exactly what its creators are going for: “Voi will also be receiving content updates for the foreseeable future,” they say. Watch this space.

You can download Voi on itch.io.

Replaying Yoda Stories, the most 1997 Star Wars game imaginable

Yoda Stories wasn’t much more than a lightweight diversion for preteens with a propensity to hog time on the family desktop. With an overhead view, players guided a cartoonishly large-headed Luke Skywalker, ordered by Yoda to visit various planets to save his friends, collect piles of robot junk, and swing a lightsaber around.

The game was an installment in LucasArts’ stalled “Desktop Adventure” series—low-key, cutesy titles that require about as much investment as your average game of Minesweeper or Solitaire. It spit out randomly created maps of various Star Wars-esque locales. (Desert planet? Frozen planet? Forest planet? Check, check, check). It’s in the same vein of early-90s lightweight PC action titles like Chip’s Challenge, but it has the bonus of giving the player the excuse to run around and bash on Stormtroopers.

Playing it now, in my thirties, I’m questioning whether it was worth the hours I sunk into it on our screaming-fast 133mhz computer. It’s a clunky, poorly written cash-in on the series, with bloopy, cartoonish sound effects. The seemingly never-ending permutations of adventures apparently were just variations on 15 levels. Its clearest descendent is the type of game you get Facebook invites to play with from former high school classmates.

But as a kid, this little timewaster stirred my fascination with just how expansive that galaxy could be.

When Yoda Stories hit the shelves of local Babbage’s in March 1997, moviegoers had two months prior been treated to A New Hope: Special Edition, the first installment in a decades-long feud with George Lucas as he futzed with minute (and major) alterations to the original films. An updated wave of action figures were hogging allowances. The Expanded Universe, previously conversation fodder for sci-fi conventioneers and comic-shop junkies, had gone semi-mainstream with Shadows of the Empire, a novelization about the space between Empire and Jedi that received the same kind of promotion reserved for a new film. We were well in the midst of a Star Wars media blitz.

Of the three original films, it’s that gap between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi that provides the most room for the imagination to run wild. Lando and Chewie blast off to find a frozen Han Solo and wind up embedded spies in Jabba’s palace. Luke transforms from a broken and battered Jedi-in-training to a cloaked, sinister-looking master. Leia ended Empire standing beside Luke as a supportive friend, and the next time we see her, she’s the closest the series ever comes to an empowered female character, impersonating a notoriously fearsome bounty hunter.

How did these characters get from A to B? We had an overabundance of action figures, free time and imagination to act out these adventures, and a videogame playground aimed at kids made perfect sense to keep stoking those daydreams.

And so Yoda Stories dumps the player in the midst of the “what if” that’s essential to loving these films, sending the player out on a few less-than-vital missions. Waving a lightsaber at giant desert bugs to save C3PO’s head from jawas isn’t exactly captivating in 2015, but there was a charming clunkiness to the affair that kept me stuck on it far longer than I expected.

Before “procedurally generated” was back-of-the-box selling point for videogames, Yoda Stories plunked unsuspecting kids into an X-wing and told them to go run around in literally hundreds of randomly generated maps. Played today, it’s redolent of that era before there were prequels and midichlorians. It tapped into the imagination of kids wanting to bash together action figures and take Luke on more adventures around the galaxy, and for that alone I’m glad it existed. Also, for how funny bighead Luke Skywalker looks.

Pianos can emulate human voices, apparently

I never thought a piano could emulate a human voice, but based on these songs, converted from MP3 to MIDI and then back to MP3 again, it’s possible. It sounds like someone singing while being held underwater, but it’s clear enough to decipher: the lyrics to familiar songs, rendered in hundreds of notes, played all at once in a cacophonous, but undeniably impressive imitation.

A blog post from Waxy.org outlines other examples of this phenomenon, including a frantic MIDI-fied MP3 of Hotline Bling that sounds like a horror film, and a “speaking piano” that delivers its own garbled, but startlingly clear interpretation of the Proclamation of the European Environmental Criminal Court.

a cacophonous, but undeniably impressive imitation

It’s hard to say if the ability to hear words instead of a mess of seemingly haphazard notes is my mind filling in the blanks. According to Andy Balo of Waxy.org, the Pokemon theme song, which he’s unfamiliar with, sounded “totally nonsensical” after undergoing this strange conversion. You can easily convert files from MP3 to MIDI and back to MP3 using browser-based tools and free software; I’m curious to see what other warped musical oddities people can render with this technique.

While not quite the same thing, this type of experimentation reminds me of the trend of slowing down pop songs, like Justin Bieber’s U Smile, to create haunting ambient tracks—transforming something so drastically with only a simple structural tweak.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers