Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 182

December 16, 2015

A few things I learned from the late-90s game about nerds, Star Warped

A word of warning. This is an article about Star Warped, a comedic CD-Rom and a comet made of raw 1997 that swung by this planet without many noticing. Parts of this summation are painfully, extraordinarily, and sickeningly 1997, so if you’re concerned about hearing a dial-up tone in your head similar to the whir of tinnitus—be warned.

I first saw it on Splat!, a magazine-style program for the then-new animation specialty channel Teletoon. The segment was about cartoons in videogames, a cross section that couldn’t have possibly been more eclipsing for a kid who gave himself nightmares retrying Brain Dead 13 just to get more glimpses of its grotesque hand-drawn landscape. The main subject of the segment wasn’t Don Bluth or ClayFighters, but an obscure-then and obscure-now studio that shuttered when The Learning Company bought out its parent studio Palladium in 1998. This company was called Parroty Interactive. Their title card showed a red parrot in Groucho glasses to the chorus of a tinny, whirly CD-ROM cartoon march, and closed with the sound of that bird of paradise coughing out its cigar.

Parts of this summation are painfully, extraordinarily, and sickeningly 1997

In the same vein as other distractionware popular in Windows office culture, Parroty exclusively made joke mounds and minigames, interactive MAD Magazines riffing on items from the mid-90s ecosystem, such as Bill Gates (Microshaft Winblows), X-Files (X-Fools, nice one) and Myst (Pyst, which starred John Goodman and had an unreleased sequel, Driven). Star Wars was the pop culture circus I was most familiar with. I wasn’t invested in Chris Carter or Silicon Valley. Meanwhile the theatrical Special Edition re-releases and Nintendo 64’s Shadows of the Empire put Star Wars on the tongue of every schoolyard, so it was Star Warped that I begged my parents for after seeing the company’s profile. I begged my parents for this game.

We often reminisce of the ways games influence us. We do it all the fucking time. How the craftsmanship of Mario and Mega Man installed instincts in us like we were ourselves computer hardware, and we routinely return to those illustrations because they seem like the most universal.

This tendency changes from person to person. Take me, for example: Super Mario Bros. wasn’t my first Nintendo game. Bubble Bobble was my first Nintendo game, and from it I learned that games can be joyous, and dizzying, and supremely devastating. A younger version of myself crumbling in a fit of tears to my father, overcome that I couldn’t demolish the infamous Level 57. And you know what else? My home computer sucked when I grew up, the majority of games were off shareware demo disks or Monopoly. Star Warped was my first PC game, the first I sought out and fished back home. So I’m going to treat it with the same dignity, history and lessons that your first PC game gave you. So here are the things that this game taught me.

What Brian Posehn’s Voice Sounds Like

There exists about 10 minutes of never-published footage of me and comedian Brian Posehn talking backstage after one of his shows. We were smoking. During his performance he whimpered because someone in the back had already started lighting up, and he compared the smell to the dog hearing the can opener. Those rebels approached him immediately as he walked off the stage, and smoking circles began. Miraculously he didn’t have any jabs about my eye-patch, which I was wearing during an infection, and my editor was fine with me wearing during an on-camera interview (then again: never published). The point being is everyone was in a nice, toasty shape, and I lobbed some insanely stupid questions. The only one I even remember being, “Your uncanny voice is a huge element of yours. What would you do if someone else could impersonate you?”

“I don’t know,” replied Posehn, “they could have it.”

Brian Posehn is a doped-up sasquatch, his tone cruising between surly weiner and sleepy rage. During a date that ended up with watching the “Lost Episode” of Mr. Show, we commented on his unique sort of presence, which is an odd thing to say about a bald man in glasses lumbering out of a parking lot and throwing a tape into the air.

In Star Warped, Brian Posehn plays, uh, Brian, opposite Robbie Rist (Cousin Oliver from The Brady Bunch) as his brother Aaron in a messy Modesto, California apartment. The two have amassed a collection of merchandise from the Star Wars sprawl, letting the player explore their piles of junk, pirated security footage from Skywalker Ranch, fake international posters and action figures (including Pizza-Flipping Greedo and a Princess Leia modded into GI Jane by their feminist sister).

Brian Posehn is a doped-up sasquatch

Other games include a You Don’t Know Jack parody, a first-person jaunt as a Rebel paparazzi trying to snag photos of Vader’s affair with Boba Fett, and a nugget-sized arcade game where you man the Death Star and blast all the space junk threatening your hull. Though Rist sounds like a squeaky asthmatic alien that you’ll hear across the voice acting roster, Posehn’s slob mystique stuck even then. It’d be years until I picked it back up with his work in Mission Hill as the stoner roommate, but I could still recognize his performance as the vastly different character, dweeby brother.

Not all Insults are Actual Insults

In grade school, you have priorities. You want to see pornography, even though you have no sexual attraction to the material, and you want to learn swear words. Swear words are your magical spells as a kid, and the more you have collected the more powerful and influential you become amongst friends. The most important swearing warlock.

Nerf Herder is not an actual swear word.

It is strewn though Star Warped as the meanest thing to call someone. When it appeared in Star Wars itself (Leia to Han in Empire Strikes Back) I think it just high-dove through one ear and right out the other, one of those classic milliseconds of the original trilogies to spawn shirts and memes for actual generations. But at the time I didn’t know that. I just knew that it got lobbed constantly by Aaron, Brian, their sister and in some clips from a what-if version of Star Wars written by Jerry Seinfeld (the staleness of that concept was resuscitated in Netflix’s With Bob & David). Each time the characters become livid and winded as if they had just been slandered. I had to try this swear out.

It sure didn’t catch on in the schoolyard. It sounded alien. It IS alien, and it lacked the kind of punch as “fuck” and “ass,” the most revered in spoken grade-school contraband. I rhymed it during dinner around my parents to see if I could get a rile if they thought I said it. Nerd birder. Burp shirter. Nothing. I spit out nerf herder during a game of catch and my dad must have just thought I was being random; the truth is much sadder. Nerf herder is no curse word.

The Word “Splice”

There is one actual term that Star Warped taught me. A few of the sections of Star Warped are less of a game and more of an activity center. One is a time machine, where you can see R2 being taken out of his packing peanuts box or a golfing Vader in his twilight years. The other was a “Gene Splicer,” a concept I didn’t really understand when I first played the game.

Splice, as you may know, means to turn two things into one. Had I known that, I would have known that you have to put in two of the cassettes labeled after the series’ main characters in order for the machine to work. Ignorant and patient, I would put in each of the cassettes, one at a time, and wait for something to happen, maybe load or buffer or some mechanical concept, as the game’s white noise of engine hums and light bulbs looped. After no prompt from the game, and just a bunch of clicking around, I figured it out, reverse-engineering the meaning of splice and learning that Chewbacca spliced with Darth Vader would be Howard Stern.

And who knows: without these life lessons, maybe I wouldn’t be the person I am today, an adult who writes about videogames.

December 15, 2015

Try to communicate with an alien race through abstract art

With Joy Exhibition, the enigmatic Manchester-based game artist Strangethink inverts the role he gave us in Secret Habitat. Once again, the virtual space is an art gallery, but this time we are the exhibiting artist and not the visitor. That said, we do seem to be a visitor of some kind, perhaps to a distant world, as all the people inside this enclosed art gallery are aliens. It is to these slow-walking mutes that we are told to “communicate” through our art.

You do this by making use of the 10 blank canvases and the many paint guns the art gallery affords you. But you are not the total artist in this scenario. The paint guns don’t shoot in a straight line nor in a single color so that you can determine exactly what you are painting onto each canvas. Instead, you are forced to play the role of co-artist to the procedural effects placed on each gun. Some guns may shoot in spirals, others in swirling stars, one that I used created an unpredictable cloud of green and pink smog.

You’re free to choose which guns to use (though you won’t know how any of them shoot), what parts of the canvas to shoot them on, and can also pick what distance to shoot them from—distance greatly varies how the gun’s paint ends up on the canvas. You also get to decide when each painting is finished and ready to show. But your control over the artistic process is still limited; forced to submit to the peculiar behavior of these paints. This turns out to be a running theme in Joy Exhibition.

The task initially seems simple. You create images for the aliens to look at and hopefully understand what you’re getting at. “What will you show them?” asks the game’s description. But that’s the problem: the paint guns wrestle authorial rights from you so that your intentions become swayed. Maybe you wanted to communicate the notion of love to these aliens and thought a plain love heart might do the trick. But as you can only paint in abstract forms this proves difficult if not impossible.

would they understand what your paintings are getting at?

Even if you are successful in painting this love heart on one of the canvases, do you really suppose that the aliens would understand it? Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously said that “if a lion could speak, we could not understand him.” By this he meant that the lion’s points of reference would be so different to our own that this attempt at inter-species communication would ultimately fail. Likewise, a love heart means something to us as it’s embedded in our cultures as a symbol of love. But the image of a love heart itself, to an alien such as those in Joy Exhibition, would have none of this prior association and so it wouldn’t have the intention you delivered it with. An even deeper problem than this would be trying to get the alien to understand the concept of love in the first place.

Therein lies the dilemma throughout Joy Exhibition. It challenges us to communicate with a foreign culture but acknowledges through its never-ending structure and absence of conclusion that this task is impossible. It may also have more to say about the nature of art and the interpretation of it, especially in the absurdity of the exhibition space, which is always so desperately engineered to help the visitor align with the artist’s vision. Ponder this: Even if the people in Joy Exhibition‘s gallery were regular humans would they understand what your paintings are getting at? The use of procedural generation doesn’t only distort your artistic intent but seems to allude to the impossibility of expressing oneself through art and further connecting to people through the resulting abstract imagery.

And yet, there’s something beautiful captured in that uncertain space between intent and interpretation. As the aliens in Joy Exhibition stand still facing your smeared canvases you can look on, longingly, hoping that they’re getting something out of it for themselves, even if it’s not what you had in mind (if anything at all). Perhaps that’s where the joy in the game’s title is located.

You can download Joy Exhibition on itch.io.

The year in graphic adventures

Growing up, graphic adventures were essential. Sure, I might have gone to Greg’s house to race through some Mario Kart tracks now and then, or called up Izzy if I were looking for the vicarious thrill of watching him charge the dark corridors of DOOM (I was too skittish to actually play). But at home on my dad’s IBM were the mainstays: a treasure trove of epic adventures with funny dialogue and exotic, lushly rendered locales where I could hang out and explore for hours on end. The Caribbean, the lost city of Atlantis, the increasingly satirical lands of Daventry or Kyrandia … these were my preferred virtual worlds. They didn’t threaten death at every turn (which made me anxious) or demand adroit motor skills (which I lacked). Instead, they offered the kind of interactive storytelling that seemed to me the very point of art, as I was beginning to understand the concept. You just couldn’t find this stuff anywhere else.

the kind of interactive storytelling that seemed to me the very point of art

In 2015, graphic adventures aren’t so essential anymore. As I have prattled on about at length, the philosophy behind the ‘90s “golden age” of graphic adventures had a diasporic impact on the videogame industry just as the genre was entering a decline. Emerging designers inspired by classics like Grim Fandango, Gabriel Knight, and countless others would incorporate the qualities that made those games special into other genres. As a result, we now no longer rely on graphic adventures as the sole bastion of character development and narrative sensibility in videogames, which, all things considered, is a very good thing.

At the same time, this year has featured a high-profile showing of several new but traditional graphic adventures. There is a cynical way to account for this. People like me—for whom graphic adventures are inextricably tied up with nostalgia for the innocence of youth—are now old enough to put some disposable income toward crowdfunding campaigns, out of which several of 2015’s graphic adventures emerged. The upsurge in this “non-essential” genre could then simply be viewed as a retro effect: a futile attempt of an aging generation to reclaim something we lost through the mere act of growing up. And, as Proust warns, our memory of the past is not the same as the past itself; you can never really go back.

The question, once the nostalgia wears off, is this: do the games hold up? In the worst cases, playing a new graphic adventure can feel like little more than a poorly aged friend imploring you to “remember the good times.” But such entries were in the minority this year; most of 2015’s notable graphic adventures dabble in nostalgia but do not linger there, instead asserting a modern relevance that serves to justify their place on our harddrives.

///

Armikrog is the worst-case scenario: a pure bid for nostalgia which by its nature is a proposition doomed to failure. The game was created as the spiritual successor to 1996’s The Neverhood, a fondly remembered claymation graphic adventure. Armikrog banked on the notion that replicating a past success would be enough to appease a contemporary audience, but doing so only served to highlight the flaws of its dated approach, and in so doing imply flaws in its predecessor. Evoking feelings for a bygone era without offering anything new can only produce feelings of sadness and resentment. The Neverhood’s biggest selling point was its gorgeous animation, and Armikrog also looks great—but, you know, lots of games look great these days. Playing Armikrog wasn’t just frustrating for its own apparent disinterest in making something fresh; it made me wonder if in fact The Neverhood wasn’t as good as I remembered it.

How dare you promise to take me back home

Perhaps ill-advisedly, I dug up my old copy of The Neverhood and ported it into ScummVM. Sure enough: its presentation of story struck me as lazy, its puzzles abstract to the point of seeming spiteful … I’m getting upset just thinking about it. How dare you, Armikrog. How dare you promise to take me back home, where neither I nor anyone else can ever go, only to leave me with an attractive, vapid, buggy little game, not to mention a bunch of ruined memories.

///

Going into it, I expected that the episodic revival of King’s Quest would travel Armikrog’s same path, tugging at the strings of nostalgia until they break. Perhaps the foundational franchise of the graphic adventure genre, I hadn’t touched a King’s Quest game since 1990’s aggressively boring Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder!, the fifth entry in the series. I assumed that the newest incarnation—the first episode of which is titled A Knight to Remember—would evoke a little fondness, a lot of frustration, and ultimately would do little to justify its existence.

To my surprise, A Knight to Remember is sheer delight. The story feels quintessentially modern: a nebbish but clever young knight seeks adventure in the celebrated kingdom of Daventry, only to find it mired in bureaucracy. Guards place caution-tape around dangerous areas, bridge trolls are on a labor strike, and proving oneself as a knight ends up having less to do with heroism and more with jumping through increasingly obscure governmental regulations. As a result, the genre’s classic inventory/environment-based puzzle-solving fits like a glove; lateral-thinking feels like the only way to disentangle Daventry’s profoundly unromantic officialdom. The game also lets in more contemporary influences through the use of (mercifully brief) quick-time sequences, some spatial-reasoning type puzzles, and several nods (and a few jabs) to Telltale Games’ successful “so-and-so will remember that” approach to adventuring.

The new King’s Quest ended up being, in a sense, more than I remembered. Inspired casting and a whimsical score elevate the charming, pun-filled dialogue beyond what the old VGA games could achieve. I’m an adult now; older, harder to faze. Nothing can replace the contradictory mixture of glee and horror that I felt the first time I watched Sir Graham being devoured by a moat monster in Roberta Williams’ original King’s Quest. The beauty of A Knight to Remember is that it doesn’t try to bring me back there: it is a new entry in an old series, which helps cement the idea that there really is something worthwhile about graphic adventures even after the nostalgia washes away.

///

A further step removed from the trappings of nostalgia is Double Fine’s Broken Age. In this case, the game itself did not promise a return to the past, but its meta-narrative did: as an early Kickstarter success from designer Tim Schafer—who created three of the golden age’s most beloved graphic adventures in Day of the Tentacle, Full Throttle, and Grim Fandango—Broken Age came to represent the potential resurrection of the genre, as though graphic adventures had been preserved in amber for the past two decades. If you carry the burden of this expectation as you play the game, it will disappoint—nostalgia always does, in the end. But if you are able to see Broken Age for what it is, you will find that it stands as a prime example of what new graphic adventures can offer.

as though graphic adventures had been preserved in amber

Broken Age essentially takes the hallmarks of the genre and amps them up with the technical and artistic prowess that is available in contemporary game design. The art, sound, and music are among the highest quality you will experience in any game this year, and they combine to tell a sophisticated story about the pain and excitement of growing up. Broken Age is, itself, an embodiment of that journey: the graphic adventure growing up. It may not be all the way there, and certainly it’s not without some bumps along the way—I don’t know that the traditional puzzle-solving fits as logically here as in a game like King’s Quest, though Broken Age’s commitment to that approach does compel the player to engage in a slow, relaxed manner, which is essential to the game’s dreamy atmosphere and parable-esque storytelling. Regardless of its growing pains, Broken Age emerges as something familiar but still vital, something in process, capable of holding onto the old without being bound by it.

///

Lastly we come to a game that neither in itself or its creators has any direct connection to the golden age: Stasis is simply a new graphic adventure. To be fair, there is a nostalgic pull: its isometric perspective and horror theme recall 1998’s Sanitarium, a cult classic of the genre and one of my all-time favorites (recently ported to iOS). But Stasis works independently of its inspiration, using the methodical, somewhat detached mechanics of the traditional graphic adventure in order to sow unease and encourage the player to slowly unfold the microscopic human dramas of its abandoned spaceship’s former crew.

The game is not perfect; it isn’t even my pick of best sci-fi horror game of the year. (That distinction goes to SOMA, which, I would argue, shares DNA with landmark first-person graphic adventures like Myst and The 7th Guest.) But this is exactly what is so exciting about being an adult in 2015 rather than a child in the mid-1990s: it’s not either/or. Games like Stasis are worthwhile not because there’s nothing else like them out there but because they are interesting in their own right, despite the competition; they have something to say and use their genre to say it. Graphic adventures aren’t topping many lists this year, but that’s okay; they don’t need the spotlight. What they need is an identity independent of nostalgia—a raison d’etre beyond being a throwback to a decades-past era—and this year has represented a major step in that direction.

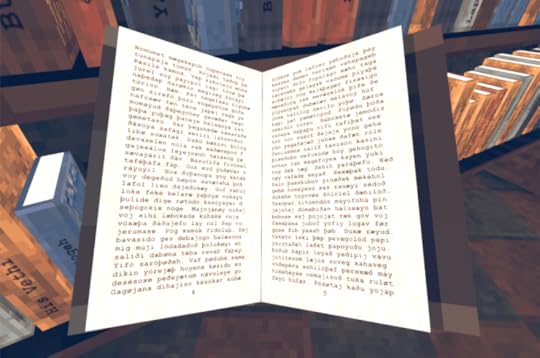

Explore an eternal cathedral of nonsense in Library of Blabber

If there is an infinite library of every possible permutation of basic letters and punctuation, among all the absolute nonsense and incomprehensible rambling must exist every coherent text that could ever be written.

This is the basis of Jorge Luis Borges’ short story, The Library of Babel, which is in turn the basis of a #ProcJam game called Library of Blabber. Created by Ivan Notaros, Library of Blabber seeks to emulate what Borges’ overwhelming hexagonal web of a library must look like: an endless series of branching hallways, each leading to shelves and shelves lined all across with books spouting random strings of text.

Some of the books use the English alphabet, others Russian or Greek, with strange imaginary titles. Once in a while, you’ll catch a glimpse on the spine of one of these novels, or several pages in, of a word understandable in your language, a small indication that maybe there is some order in all of this chaos. You just haven’t looked hard enough.

find sense in the mess of non-words

The inhabitants of Borges’ Library of Babel went crazy trying to find sense in the mess of non-words. You might, too, if you spend long enough doing the same. A website also titled Library of Babel attempts to recreate the same thing, hosting a database of random strings that you can access randomly, or via a network of visualized bookshelves.

It’s an interesting and overwhelming experience to occupy what a library like this might look like in three dimensions.

Download Library of Blabber for free on itch.io.

Where Horizon Chase got its retro-futurism

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

From Gran Turismo to Grand Theft Auto, players often master the best racing games from behind the spoiler of an unlicensed Corvette. Horizon Chase stays true to form: As the player skids and swerves to keep from wrecking her cherry-red hot rod, the music swells to what sounds like a guitar solo from a lost Guns N’ Roses album.

Reproducing the distinct digital driving experience of the late 80s to early 90s, the game supplies players with a constant nitro boost of nostalgia. Just don’t call it old-fashioned.

That’s because Aquiris Game Studio designed Horizon Chase to be retro in the best possible way. This meant overhauling the less desirable aspects of older games while still maintaining its reflective outlook.

“[The game is] like a reality where half the computer graphics evolved to be what they are today, and the other half were left frozen in time,” said Amilton Diesel, the team’s Technical Art Director.

Part of the reason Aquiris Game Studio has a knack for crafting new games that feel endearingly old is because of their location: Brazil.

“16-bits systems were probably the most popular video games in Brazil so far,” Diesel said.

This phenomenon was a product of necessity. Because steep tariffs and government regulations kept new game consoles from penetrating the market, the vintage systems had a much longer shelf life than they did in the rest of the world.

“I’m not a big fan of pixels.”

An official version of Sega’s 8-bit Master System, for instance, was released in the country as late as 2006, although the system has been discontinued in North America since 1992. This gave Brazilian developers a unique perspective that goes beyond mere nostalgia.

Diesel sees videogames as the perfect medium for exploring the “retro-future”—not the future as it came to pass, but as it might have happened if you went back in time, stepped on a microchip, and set off an unforeseen chain of events. The retro-future is the space in which “having flying cars but not mobile phones can still somehow make sense,” he said.

In the case of Horizon Chase, it is a sly hybrid of the racing games kids loved at the beachside arcade and on their Xboxes as adults.

“What we did was basically deal with the same limitations of developers working on the Super Nintendo,” Diesel noted, saying that the team then added modern techniques and a new art style.

While they are extremely fond of the art design in early racing games—the wide open skies, the snakelike scrolling of the highway, how the signs on the roadside flickered by—creating a sleek experience on mobile phones required the developers to update some things.

“I’m not a big fan of pixels,” Diesel said, referring to the hundreds of grainy little dots that old games were drawn with.

“Modern devices call for something better, like polygons with pure and vibrant colors. They have the power to create the perfect ‘computer world.’”

This posed a dilemma: creating an old-school racing game without pixels is like ordering a steak without the red meat. Pixels were fundamental to the way these racing games were created.

He stitched together the outdated pixel techniques with present day polygons.

Prior to the mid-90s, game hardware was too limited to show a car zipping toward the horizon, so game developers had to fake it. Games like Out Run and Pole Position were made up of pixelated images (think of those iconic palm trees) which got larger as the player scrolled toward them. This created an optical illusion that the user was cruising through 3D space—even if, in reality, it was closer to a programmable LED sign.

This seems archaic by today’s standards, but it was also fundamental to the design of classic racing games. Diesel couldn’t just take Out Run and give it a fresh coat of paint. To do so would undermine all the qualities that made those games special in the first place.

Instead, using great care, he stitched together the outdated pixel techniques with present day polygons.

“Triangles and illusionism put together in the form of computer graphics are my real motivation,” he said.

A bit of deception is involved as well. Like any classic racer worth its salt, “Horizon Chase is essentially a 2D game,” Diesel explained.

“It may look like a 3D game, but if we try to rotate the camera a few degrees, everything breaks. The sky, tracks, cars — they all break.”

It was this careful manipulation of the artwork that makes Horizon Chase authentically hum. Diesel said being able to stitch together these graphics was the most challenging and rewarding part of tackling this project.

“All of this was done to capture the look and feel in exactly the same way it was 23 years ago,” he said.

For players who miss burning rubber in retro-graphics glory, those drives into the sunset with the 80s rock blaring are surely worth the effort.

Young Saudi women demand we expand the imagined gaming community

That all sorts of people now play games is something of an article of faith, but definitions of “all sorts of people” vary. Inclusivity has a great deal to do with imagination; it requires you to imagine that people who are not your clones share common interests. The success or failure of communities—of gamers and otherwise—has a great deal to do with this form of imagination. (Rest in peace and power, Benedict Anderson.) Alas, when it comes to gaming, the imagined “all sorts of people” can be a very homogeneous group.

As a corrective, NPR has an excellent piece about GCON, which is an annual convention in Riyadh for Saudi women who love games.

(Image source. Taken by Ashwag Bandar)

The tournaments listed on GCON’s website focus on major titles and do not hew to tired tropes: FIFA 16, Call of Duty: Black Ops II, Assassin’s Creed. “Some 3,000 women showed up over the two-day Riyadh event in late November,” NPR’s Deborah Amos reports. Another two-day event was held in Khobar in early December.

Saudi Arabia, it should be noted, is not only home to active gamers, but also to developers. Earlier this year, Amos reported that developers were filling a cultural gap left by a relative dearth of film showings and live entertainment. One of the titles she highlighted, SemaphoreLab’s Unearthed: Trail of Ibn Battuta, tracks a brother and sister pair (he hunts treasures; she’s an archeologist) as they follow the steps of the 14th century explorer Ibn Battuta.

a community depends on its ability to find points of commonality

It is important to imagine these games, and those who make and play them, as part of the gaming purpose. It is important to imagine this, because these titles and people are part of this community, but also because the failure to do so is damaging to all. As Benedict Anderson explained, a community depends on its ability to find points of commonality that allow an individual in one location to feel an affinity for others who they will never meet. We never get to know most people in the nation state—or the gaming community for that matter—but institutions depend on our being able to imagine that there is a degree of commonality. For everyone’s sake, it is important to do that here.

TIE Fighter found the humanity in fascism

In 1993, LucasArts released Star Wars: X-Wing, a space flight simulator that let the player fly as part of the Rebel Alliance in missions focused on ambushing Imperial forces and gathering intelligence. The game received near universal critical acclaim for its authenticity as both a window into the Star Wars universe and as a flight simulator that reproduced in excruciating detail the difficulty of piloting for the Rebel Alliance. In X-Wing, nearly every button on the keyboard serves a purpose, from shield and energy management to changing cockpit viewpoints, making the dogfights a careful balance of ship maintenance and white-knuckled shooting. The game did, however, have a few rough edges indicative of the studio’s inexperience with flight simulators, the ships sometimes handling clumsily or chasing objectives that could only be fully understood after multiple failures. It makes sense, at least in retrospect, to think of these rather insignificant stumbles as part of the Rebel Alliance’s own sloppiness of sending groups of ragtag freedom fighters against a colossal military outfit; the game carries a sense of underdog charm in the Alliance’s guerilla strikes against the Empire.

the perspective shifted from the story of the noble Rebels to the machinations of the evil Empire

LucasArts rectified many of these small quibbles a year later with the release of Star Wars: TIE Fighter, a more polished title with better resolution, improved sound, and sharper AI. More importantly, the game presented the first instance in Star Wars history where the perspective shifted from the story of the noble Rebels to the machinations of the evil Empire. The player steps into the flight boots of Maarek Stele, a character named only in a supplemental booklet (and later official strategy guide), who pilots various ships for the Imperial Navy on missions that range from repelling Rebel attacks and securing new technologies to intervening in a civil war and rooting out Imperial traitors. The focus on maintaining the Empire’s seat of power gives TIE Fighter a much grander scope than X-Wing, which, again, makes a certain amount of sense, considering the Empire’s expansive control and vast resources. As an Imperial pilot, I rarely felt like more than a drone sent to repair the occasional hitch in the Empire’s political machinery, working to keep the Empire from running at maximum efficiency. As a result, TIE Fighter inadvertently becomes a game as much about the functional aspects of fascism as it is about tense dogfights and galactic conflict.

TIE Fighter begins after the Rebels’ evacuation of their base on Hoth in Empire Strikes Back. The iconic Star Wars text crawl cascades across the screen, only here John Williams’ “The Imperial March” provides the score and the language of the text is replete with hyper-nationalistic spin. Explaining how “Rebel terrorists … struck a cowardly blow at the new symbol of Imperial power” with the destruction of the Death Star, the text lauds Darth Vader’s commitment to “swift justice” and the Empire’s mission “to eradicate rebellion and restore law and order to the galaxy.” The association of the Empire with fascist regimes like Nazism has always been clear, from the officers’ uniforms and regalia to the actual name of their troops as “stormtroopers,” but TIE Fighter reproduces directly the language of nationalist propaganda. The game continues with a speech from Emperor Palpatine that explains how the Empire is “on the verge of success” despite the destruction of the Death Star and the botched Imperial assault on Hoth.

This language mimics the nationalist rhetoric circulating across Italy and Germany that gave rise to fascist ideologies in the wake of World War I. Adolf Hitler famously detailed his philosophy of propaganda in Mein Kampf, explaining that “the art of propaganda consists precisely in being able to awaken the imagination of the public through an appeal to their feelings” in order to reach “the broad masses of the people.” Believing in the power of repetition and the gullibility of the crowd, the Empire wields information as deftly as it does its military branch, promising a galaxy of peace and order while downplaying the threat of the Rebel Alliance. TIE Fighter’s glimpse into the rhetorical strategies of the Empire shows a side of the Star Wars conflict beyond the dynamic battles and simple political narrative of the films to convince the player of the virtues of Imperial ideals.

Political language, of course, comes secondary to the actual operations of the Imperial navy. Here, TIE Fighter borrows more from Benito Mussolini’s Italian fascism than from Nazi propaganda. While the Emperor bandies words in the political arena, the Empire’s military adheres more closely to Mussolini’s dictum in “The Doctrine of Fascism” that “War alone … puts the stamp of nobility upon the people.” Mussolini calls for national unification by abdicating the indulgences of individuality in favor of “the State as an absolute.” Likewise, pilots in TIE Fighter are indeed rewarded for their success, but their objectives always inform a connection to the Empire’s cause, foregrounding the importance of the Imperial progress rather than individual accomplishments. Here again, TIE Fighter elucidates a more complex picture of the Empire—one that promotes collective order and efficiency as pathways to peace.

the player strives all the harder for recognition

Much like the fascist ideals that inspired the Empire of Star Wars, such philosophies often came at the expense of the people fighting for them. Consider, for instance, the disposable simplicity of the TIE Fighter. Essentially a shieldless cockpit held precariously between two tall hexagonal wings, the Twin Ion Engine starfighter serves as an example of the philosophy driving the Imperial war machine: victory by overwhelming force. Mass-production forms the technological backbone of the Empire’s war efforts; consequently, the TIE Fighter’s effectiveness comes not from its individual power but from its inclusion in a swarm of other fighters, each as expendable as next. The Imperial navy reduces the complexities of war to ruthless calculus, a game of numbers winnable by amassing the largest fleet.

For the player of TIE Fighter, however, being a faceless pilot in a swarm makes any personal victory all the more satisfying. Piloting a fragile, cheap ship forces the player to prioritize evasive actions instead of aggressive force, and as a new recruit, the player must prove herself by completing missions in the TIE Fighter, TIE Bomber, and TIE Intercepter. While X-Wing begins with the player piloting a shielded craft, TIE Fighter makes the Empire’s value of the player clear by withholding the more heavily-armored Assault Gunboat until the player can survive her first few missions. As the game progresses, the Empire invests in more specialized craft like the TIE Advanced (later named TIE Avenger), and the TIE Defender—but only after the player secures the supplies and intelligence required to develop them. The stakes of the missions, too, increase in complexity as the player progresses, beginning with simple bureaucratic inspections until the player eventually flies in formation with Darth Vader or rescues Emperor Palpatine from a traitorous kidnapping plot.

This mission and equipment escalation proves to be the game’s masterstroke. Even as the Empire upholds the concept of unity by diminishing the worth of the individual, the player strives all the harder for recognition. The faceless and voiceless protagonist of TIE Fighter may believe fervently in the Empire’s goal of peace through order, but games as a whole (and certainly the games of the early and mid-nineties) insist on the player’s importance as an individual, reinforcing her worth through rewards. In the beginning of the game, the Empire expects the player to fail, to die as one of the swarming pilots crashing against the Alliance in hopes of overwhelming them. Only through skillful flying can the player survive long enough to gain the recognition she deserves as one of the Imperial navy’s top pilots—a victory assured through the sheer number of pilots still speeding headlong into the fray, ready to die for the ideals of an uncaring Empire.

That drive to become a key component in the Empire is what I remember most about TIE Fighter when I first played it over two decades ago. Though I enjoyed X-Wing, flying under the Imperial insignia was far more engrossing, beyond the novelty of flying for the enemy every other piece of Star Wars media told me to hate. There exists an undeniable clarity to the Empire’s mission, despite the dehumanizing, mechanical political ideologies that inspired it. Admittedly, I have become recently troubled by the game’s seductive reveal of the Empire’s reliance on propaganda and the ruthless disposability of its pilots, and I would wager that the game wants the player, to some degree, to embrace and interrogate the values that drive many of the mission objectives. In fact, I’m sure of it—just as sure as I am that damn near any cause could seem noble to someone willing to be swayed by some clever rhetoric and a show of power.

December 14, 2015

“After GTA V” and the inevitable deterioration of data

New York artist Rachel Rossin sees beauty in an ersatz sunset. “GTA V has some of the most beautiful sunsets I have ever seen and they give me a very similar experience to the sublime that I experience in ‘real life,'” she says. “This was very interesting as my show, Lossy, was about the translation of physical reality to virtual reality.”

Her exhibition, Lossy, was held in Zieher Smith & Horton, Manhattan from October 15th through November 14th 2015. Part of it pays tribute to those unreal sunsets in Grand Theft Auto V as an oil on canvas painting titled “After GTA V.” It depicts two sunsets attempting to wrap around each other. Rossin is credited as the sole author of this painting but she considers herself to have a co-conspirator in the form of physics engines.

The process behind creating these paintings acts as an explanation: Rossin creates “drafts” of each painting and then transfers them to virtual reality, where the 2D images are given cloth dynamics simulations and subjected to inverted gravity so that they crumple and distort, then Rossin simply picks stills from the results to turn them back into physical tableaus. In other words, the paintings are churned through a physics engine and then piped back out onto a canvas, meaning that we can only experience Rossin’s original paintings in a mediated form.

Lossy reflects the increasing method by which many of us experience real locations and objects, which might be through a TV, as a photograph in a magazine, or recreated in a digital space. Perhaps you’ve explored Chicago in Ubisoft’s Watch_Dogs but have never physically visited the city yourself. What Lossy represents is the image saturation that we experience as we jump from screen-to-screen in our modern lives. The title of the installation makes reference to lossy compression in JPG and MP3 formats, as data is encoded to a digital form and inevitably loses some of its original quality as an inferior facsimile.

“it’s about the entropy of these moments”

Accompanying “After GTA V” and the other paintings that made up Lossy were virtual reality headsets that dangled from the ceiling. Putting them on let the visitor enter the virtual reality installation “I Came and Went as a Ghost Hand,” which Rossin tells me is about floating by windows of three-dimensional captures of time.

“The photogrammetry captures are of personal moments of my life and the tableaus that I painted from,” Rossin says. “So it’s about the entropy of these moments (as you travel there is a script that lightly decimates meshes) and then the strange familiarity and translation of a 2D (painting) that you’re literally inside of.”

You move without control as a spectre through warped and decaying virtual architecture. The memories of Rossin are seen to fade, violated by the entropic effects of time and repeated technological degeneration.

Thematically, it recalls the notion of “kipple,” as devised by sci-fi author Philip K. Dick, who described it as useless objects, implying the epic waste left behind after aggressive capitalism. “It’s a universal principle operating throughout the universe,” Dick wrote about kipple, “the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.” If “kipple” applied to the gradual waste of physical objects, perhaps Rossin’s coinage of “Lossy” can be understood as a similar term, one that references the unstoppable deterioration of all digital data.

You can find out more about Lossy on its dedicated webpage and about Rachel Rossin on her website.

///

Groundhoth Day

Stage One

They call Hoth “the ice planet,” because that’s exactly what it is. I found that out immediately upon arriving at the Rebels’ Echo Base mere days ago. The word “Hoth” even sounds frigid, like the exhale of visible breath in winter. We’re out in the middle of nowhere on Hoth, a tiny speck on an uninhabited world of permanent freeze. The remote location of Echo Base helps us to escape prying Imperial eyes, but as an extra precaution, the fort itself is dug out of snow and mountain rock, hidden from plain sight by all but the most discerning of gazes. And now it’s gone, or at least we’re gone from it.

Imperial forces that managed to scout our location attacked us. A shield, powered by a massive outdoor generator prevented their space brigades from conducting a direct assault, but their ground troops were undeterred. They destroyed the generator and we were forced to evacuate the base. I managed to escape in one piece, but I was lucky. Maybe we should have seen the assault coming and began the evacuation sooner. I don’t know, I’m just a speeder pilot, part of the Rebels’ Rogue Squadron. I follow the orders I’m given. All we could do was deflect fire from our transports as they fled to safety.

Command ordered us to take out Imperial probe droids first. Easy enough business, really. Probe droids are these little hovering pods with gangly pincer arms. Their black, metallic shells make them pretty simple to spot out against the gleaming white drifts. A couple blaster rounds seem to trigger their self-destruct functions. The sounds of their robo-scatting transmission signals are burned into my brain, mocking my subconscious from their ashen craters.

Next, the walkers came. First it was the bipedal AT-STs—“chicken walkers,” we call ‘em. Basically metal pillboxes on legs. Their outer casings are resistant but still they can only take so much targeted blaster fire. I managed to take one out from behind in my speeder. Their heads can rotate about 180 degrees, but based on the direction they were striding, it was clear they had our shield generator in their sights.

I managed to escape in one piece, but I was lucky

The AT-ATs were the real trouble. These gigantic mechanized cows (or bantha, if you prefer) are heavily armored and can traverse the deepest of snow banks without issue, plodding forward like elephants. “That armor’s too strong for blasters.” I heard over the comm system. Someone had the ingenious idea of tying up the AT-ATs legs with our speeders’ tow cables. It’s a tricky maneuver even without the warzone crossfire. Still, despite the odds we managed to string up a couple and send them tumbling into the frost in a tangled mess. No matter the tactics though, we were ultimately outsized and outgunned. Once the walkers got in range of the shield generator, it was over. Our mission was a success only insofar as retreating and permanently losing your position can be considered successful. I am alive though, I suppose.

///

Stage Two

I’ve seen this all before. Hell, I’ve DONE this all before. Somehow, magically(?), I’d returned to Echo Base. Everything played out as it did yesterday, or at least the broad strokes as best I can recall. That I can’t reason what has actually transpired and what I’ve only imagined leaves me unsure of what is real. Perhaps I’ve been knocked unconscious on a patrol and am conjuring frozen nightmares of arctic battlegrounds from my own imagination.

I don’t have an explanation, but something was a bit curious about the battle on Hoth this time around. I knew what was going to happen before it occurred. I knew how many probes were deployed. I knew shooting the AT-ATs with blasters was a fool’s errand. Yet I listened to my squadmates come to these realizations in the moment. I didn’t know how to explain my preexisting knowledge of the AT-AT tow-cable strategy, but I followed through with the process all the same. Down went more bovine mechs, but not enough of them to prevent the destruction of the shield generator once again.

Could I have warned Command and prevented all this? I can’t be certain. I woke to emergency sirens, and there was no time to consider. Soon enough the screeching Imperial lasers began echoing through the corridors of our ice fortress. I saddled up my speeder to enter the fray with the rest of Rogue Squadron. Unfortunately, the encounter concluded with the same seemingly futile resolution as last time.

To my dismay, I’m faced with the possibility that I’ll awake in Echo Base once more tomorrow and this battle will recommence a third time. I have no desire to repeat this tragic course of events again, but if it must be, I want to be prepared. Perhaps we could rally more than simply a safe retreat, even a counterattack. Maybe it would be possible to hold off the Empire with a pre-emptive strike. If Hoth greets me in the morning, I’ll be ready for it.

Tonight though, I’m determined to dream that I’m somewhere very unlike Hoth, somewhere warm and secluded. I hear Dagobah is nice this time of year.

///

Stage Three

… Hoth … again.

Did this cursed ice ball somehow manage to freeze space-time itself? Is it my fate to hogtie robo-cattle for eternity? At this point I’ve begun to wonder if there’s some other external condition that God or The Force or whatever power is out there is cryptically pressing me to satisfy, and I’m missing all the clues. Try as I might, I couldn’t prevent, halt, or counter the Empire’s assault. I took down 3 AT-ATs singlehandedly and yet they still blew up the shield generator right on schedule.

Try as I might, I couldn’t prevent, halt, or counter the Empire’s assault.

It was pointless to warn Command; preliminary evacuation was already underway when I came to. I thought my advance knowledge out on the field could have stemmed the tide in our favor, but there was always another walker lurching over the horizon. I’m beginning to think there’s no true win state for the Rebels on Hoth, and perhaps, more dishearteningly, for myself either.

Let’s say tomorrow I’m back on Echo Base once more and I figure something out. Something big. Let’s say I uncover a way to cause a massive, ground-splitting tremor and Hoth itself opens up like a wintery maw and devours every last Imperial walker, enveloping them in its dark, white abyss. Does that make the cycle stop? Or is this internal? Am I the broken spoke on the wheel?

Strangely, the detail I find myself obsessing over is that I’ve fought in other battles. I’ve been in dogfights with TIE Fighters in the depths of space. I’ve blown up turrets on Imperial battlestations. I’ve evaded capture through asteroid fields and outrun bandits in narrow canyon systems. What’s special about the Hoth conflict that I must relive it and not the others? I’m fearful of the amount of time I may have to find an answer.

///

Stage ∞

I’ve stopped questioning why this is happening anymore. Having relived the battle on Hoth dozens, maybe hundreds of times now, I’ve become totally disconnected from the meaning of the fight in relation to the larger war between the Rebels and the Empire. There are no stakes for me at this point, only the design of the encounter, which has become my defeatist sandbox. I’ve drawn maps and marked enemy positions, but nothing carries over except my memories. It’s amazing how once-random, complex systems can seem so purposefully articulated after enough repetition.

Numbers aside, I’ve been considering whether the Rebels or the Empire actually has the advantage here, and finding it a relatively even matchup despite how asynchronous the tools and methods are between the two. It turns out Hoth itself is ostensibly neutral terrain (no one on either side wants to be here). Sure, the Rebels have trenches to take cover, but their infantry fire isn’t felling any Imperial vehicles of consequence. Ultimately, it’s a speeder versus walker fight, where all players are literally out in the open. Maneuverability and accuracy are the Rebels’ roguish attributes (the Rogue Squadron title, perhaps no mere coincidence), while the Empire are the tanks, absorbing high levels of damage with a singular, destructive goal in mind.

I started inventing little challenges for myself to “maximize” my time on a particular run. For example, I like to see if I can hunt down all of the probe droids before the shield generator goes down, or fly through all of the AT-ATs’ legs without taking a hit. Once I managed to disorient and trick an AT-ST pilot into firing on one of their comrades, which took a great many attempts to carve a successful flight path. My reward is ultimately only whatever satisfaction I can derive from the moment of my performance, since these are the only moments I have to experience.

We’re all just following orders after all. Well, everyone else is anyway.

A long time ago, when this was first beginning, I asked myself, “Why Hoth?” I still don’t know that answer, but I can at least say that, divorced from the reality of the consequences of war, the Hoth battle is an elegantly designed encounter, and I now possess a deep appreciation for it. It’s an epic military drama where the underdog can only triumph through ingenuity and sacrifice, fittingly tragic in the Rebels’ inevitable defeat. While I’ll always be sympathetic to the Rebels’ cause, I’d be quite interested to witness the skirmish from the Imperial side and better understand their perspective and mentality. We’re all just following orders after all. Well, everyone else is anyway.

I’ve resided that Hoth may just be the way of things, and even if I were to break out of this loop, I may never really leave the snowy field. I’ll continue circling, tying up the loose ends.

One more pass…

The Year of Not Playing Games

This coming year, I will turn thirty-five years old. Such an accumulation of time brings certain privileges: the ability to run for President; the removal from key marketing demographics, aged 18-34, typically known as Young People; the necessity to buy shampoo that strengthens follicles at the root, “saving hundreds of strands per month.” When I entered that most trend-setting of audiences, way back in 1999, I did not foresee “playing and writing about videogames” as a key element of my identity in this far-flung future. And yet here I am, contributing to a year-end series about an industry whose evolution has shifted alongside my own throughout the course of its relatively short history.

But here’s the thing: I’ve squandered the last year of my marketable youth ignoring most of the videogames on most of the Best Of lists, including Kill Screen’s own. I could have kept up. I could have joined the conversation. But I didn’t, content to remain blissfully unaware of Solid Snake’s pain or Cibelle’s awkward romancing, because life beyond the screen proved challenging enough without any more lives lost. When asked to consider a theme or trend worth discussing, I could only think of an absence of themes or trends. For me, 2015 was the Year of Not Playing Games.

At least, that’s what I told myself and my editor. Then I checked the numbers. Turns out, I still played a ton of videogames. Less than previous years, yes. But the larger factor in my mental erasure of them had to do with perception. The games I played were not the ones I was supposed to have been playing. For some reason, they were not important enough, or new enough, or indie enough, or AAA enough, or obscure enough, or interesting enough to merit my attention.

I found two common denominators between those games I did sink time into: They were either on Nintendo systems, or were not released in 2015. The year started out strong, playing two award-winning games… from 2013. In January I fired up The Swapper, my New Year’s resolutions being transmitted metaphorically onto a 46” screen. I could be someone else this year, I thought, cloning and killing off multiple selves through the ten hours I played.

For me, 2015 was the Year of Not Playing Games.

I put 18 hours into The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds, GameSpot’s Game of the Year 2013, between February and March. Few of you out there, those reading this now, were talking about it anymore. But it was still good. I pressed Link into a two-dimensional painting on the wall and felt strangely whole. I must enjoy playing in the wake of past adoration. The last Zelda game I played on 3DS was another bypassed classic, the 3D remaster of Ocarina of Time I first experienced on the handheld. In my review, I list things my 17-year-old self was more concerned with at the time of its 1998 original release than playing a new videogame, among them my own two “spiritual stones” growing heavy with disuse. That’s one benefit of time, and being married: You feel confident enough to reference your testicles in a public forum without worry of recrimination.

You also can delight in the beauty of a pink blob artfully rendered in clay. By March, I put another ten hours into Kirby and the Rainbow Curse, this one at least current, though notably forgotten by the time December rolled around. Its charms are real, but our collective short memory is valid; for some reason the touch-screen puzzle-roller does not linger brightly in my mind, even though I enjoyed its thumbprint-stamped imperfection.

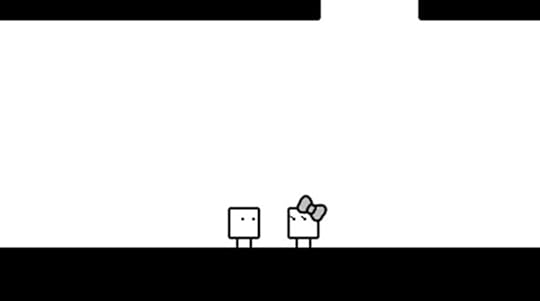

April brought with it another current game, but a small one, and one cut from such a simple, rudimentary mold as if to have been released in 1989. BOXBOY is a brilliant little exercise in avoiding excess. HAL Laboratory’s platformer does the most with straight black lines since the intercontinental railroad. How’d I forget the ten and a half hours spent throwing my square-head onto edges and reeling myself in? Perhaps the black-and-white aesthetic blurred my time with it into some pre-Oz-ian memory lapse. Perhaps the lack of a box on the shelf failed to remind me once end-of-the-year voting began.

That’s one regrettable consequence of our new all-digital consumption. Fewer physical goods mean less clutter, yes, and lighter boxes when moving across town. But as we read on our Kindles and listen to MP3s and play a digital file, foregoing the slip of a compact disc into a purring system, we grow disconnected from the thing itself—I experienced BOXBOY, but I didn’t place a cartridge in a slot. I can’t look across the room and see its spine alongside a collection of other games. When I felt like I hadn’t played anything this year, I must have meant something closer to this: I had not as frequently interacted with the tangible coverings that once meant “videogame.”

Come summertime, I did just that. A trio of Xbox 360 games have sat under my TV, wrapped in cellophane, for years: Fallout 3 from 2008, Bayonetta from 2009, and Child of Eden from 2011. While many sunk into their Steam Sale purchases, I caught up on past hits on old hardware. But more importantly, I displaced a physical disc from its plastic anchor and placed it on an extendable tray.

My layman hypothesis is contrasted by science, alas. Dr. Thomas Gilovich, professor of psychology at Cornell University, has studied how consumer goods and experiences affect our happiness. “You can really like your material stuff,” he writes. “You can even think that part of your identity is connected to those things, but nonetheless they remain separate from you. In contrast… We are the sum total of our experiences.” He’s referencing more active pursuits like traveling or visiting a museum. But to exist in a virtual world is one kind of experience. To own a plastic disc should not equal or trump what happens while there. Still, I wonder how downloading games will alter our memories of them in years to come.

But to exist in a virtual world is one kind of experience.

Awash in culture, especially as another calendar year folds over, we’re festooned with commands. Do this, listen to that, play this, watch that. And if we veer to the side of all this noise, the same noise that will be forgotten for the next wave of hype-riders in 2016, there’s a very real chance of feeling left out, or left behind. I can’t say how many times I hear or see another person expressing angst over not experiencing some heralded piece of culture. As an occasional irritation, the damage is minimal; “I should have ordered the soup instead of the salad.” But as a moment-to-moment drip of anxiety, the result feels closer to lunacy: An absence of reason, the opposite of reality.

When asked to consider their year’s experience, a suitable answer becomes, “But I didn’t play any games.” On Wii U (317 hours) and 3DS (123 hours) alone, I spent the equivalent of over seventeen days in front of videogames. But by and large, they weren’t what others in the enthusiast, alternative, or mainstream press were talking about. Drip, drip, drip. The erosion leads to valleys where before there was a mountain.

The James-Lange theory suggests that our experience of emotion is actually an experience of bodily change as we perceive that emotion. We don’t run away because we are afraid; instead, we are afraid because we run away. C.G. Lange, a Danish philosopher, developed the theory in the mid-18th century. Elsewhere, William James theorized the same notion, independent of Lange’s work. Today their names are connected as if having worked in tandem. But the truth is they conducted their own research and only later saw that another felt the same.

It is increasingly difficult to remain untouched by others’ opinions. By the time you play a particular game, or see a film, or read a book, you likely know how thousands before you felt. But resist the temptation to have such opinions narrow your field of view. There’s little sense in crowdsourcing a Rorschach test. The ink-blot awaits you, its wavy contours a mystery, whether translated now or in ten years.

//

Header image by fotologic via Flickr

Rorschach Test photo by Zeh Fernando via Flickr.

Old Man photo acquired via Wikipedia Creative Commons.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers