Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 180

December 21, 2015

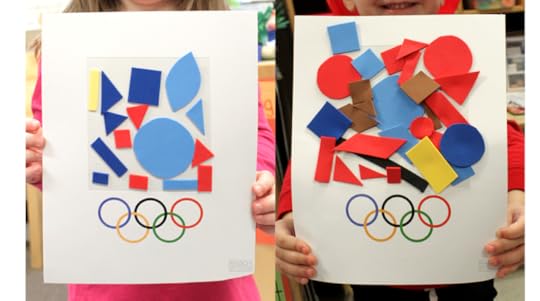

3-year-old graphic designers tackle the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

A U.S. designer enlisted the help of preschoolers in a project to redesign the Tokyo 2020 Olympics logo after the original design was scrapped for plagiarism.

Michael Raisch, a graphic designer based in the U.S. reached out to his daughter’s preschool class for help in the design of the new Olympics logo. Raisch gave the children colored foam shapes to arrange into a logo of their own design. The results? A mishmash of designs ranging from the sparse contemporary sprinklings of a few triangles and the occasional blue oval, to a rainbow pile of foam that would have Picasso squinting for meaning.

The original Tokyo 2020 Olympics logo, designed by Kenjiro Sano was tossed after graphic designer Oliver Debie pointed out similarities to the logo Debie started working on in 2011 for the Théâtre de Liège in Belgium, the Japan Times reported. Tokyo is currently crowdsourcing possible designs from Japanese artists in a search for the next logo. However, any Japanese citizen over the age of 18 is free to enter the contest online.

The children’s designs followed the guidelines of Japan’s contest, but were an educational exercise only and will not be submitted, as they were created in the U.S.

Théâtre de Liège vs Tokyo 2020

#Tokyo2020 #ThéâtredeLiège #plagiat? pic.twitter.com/u64MpWBAI2

— Olivier Debie (@OliDebie) July 28, 2015

“As a creative professional working in the sports branding field, I felt it was important to discuss the significance of creativity and expression in logo design over the trend of crowdsourcing,” Raisch said. Raisch used the children’s designs to create images of the logos on flags, t-shirts, planes and commercials, the way an actual Olympics logo would be presented. The resulting images can be seen on his website.

The Year of Mom

It begins with her. Whether the birth of a nation or your own life, it all began with her. Inside her, existence takes shape. Outside her, the shape of her existence is forgotten. As American poet and feminist Adrienne Rich says, “Life on the planet is born of woman.” Yet, somehow, the begetter of planet Earth has been all but cursorily kept out of humanity’s central myths, social structures, and ideologies.

In Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, Rich weaves autobiography with literary and historical research to paint a universal portrait of motherhood as it exists under patriarchy. Rich defines patriarchy as “the power of the fathers: a familial-social, ideological, political system in which men—by force, direct pressure, or through ritual, law, and language, customs, etiquette, education, and the division of labor, determine what part women shall or shall not play, and in which the female is everywhere subsumed under the male.”

“Life on the planet is born of woman.”

It is no wonder, then, why motherhood is often kept out of the creation, consumption, and conceptualization of popular culture. A society ruled by the Kingdom of Fathers, as Rich describes, relies on the devaluing of motherhood while also simultaneously tasking motherhood with the most invaluable work on the planet. A mother’s reward for breeding humanity is exclusion, marginalization, and disregard. At most, motherhood appears in popular culture as a concept: a perfect, selfless mirage or a horrid, selfish monster. Her story is never told in full: from her exclusion in something as silly as #dadbods, to the continued absence of significant maternal stories in mainstream videogames, TV shows, and films, patriarchy puts the mother in opposition to pop culture—after all there’s no quicker way to kill a trend than to see your mom do it, right?

However, 2015 revealed glimpses of the mother’s elusive profile. Shows like Jane the Virgin and The Mindy Project, for one, broke the cardinal rule of motherhood on television by actually showing the aftermath of a character’s pregnancy for longer than a Christmas special. And even more taboo, Jane the Virgin places central narrative importance on not only the child, but the experience of the mother as she struggles to live up to her notion of motherhood.

Yet despite its unabashedly frank (and notably entertaining) depiction of such things as “pumping and dumping” (which is when a new mother who drinks alcohol must “pump and dump” her breastmilk so as not to booze up her newborn) even Jane the Virgin falls prey to what Adrienne Rich would call the institution of motherhood: a definition of the maternal that relies on inhuman selflessness.

In the the institutionalization of motherhood under the power of the fathers, the female body becomes “both territory and machine, virgin wilderness to be exploited and assembly-line turning out life.” Women are considered reproductive factories in the Kingdom of Fathers, valued for their uterus and discarded once it is used to house and raise the father’s offspring. More than just co-opting the female body to perpetuate the very system that oppresses it, patriarchy fundamentally devalues the very definitions of motherhood that it fabricates. Patriarchy dictates that mothers must raise children, but in patriarchal society, that human life carries little value. The Kingdom of Fathers may feign a respect for human life but, “women, upon whom most of the burden of respect for life has been placed, know that it does not. We know too much at firsthand about the violence… which over centuries we have been told is the way of the world, but which [women] exist to mitigate and assuage.”

In a patriarchy, mothers must be viewed as a singular force with a singular function. Take, for example, the fleeting yet impactful role of the wildling Karsi in the “Hardhome” episode on this past season of HBO’s Game of Thrones. Karsi is defined, from start to finish, by her motherhood. She aligns herself with her enemy Jon Snow in order to save her two daughters, and then dies at the hands of tiny zombie Walker children because…. motherhood? Karsi’s death sequence, in which she finds herself incapable of fighting against rotting zombies because they take the form of children, perpetuates the curious assumption that a mother’s instinct—even a tough wildling mother—outweighs her primal need to survive. Yet, as Bianca Batti of Not Yo Mama’s Gamer points out, Karsi’s death isn’t even a logical depiction of the self-sacrificing mother because, “if such a maternal instinct is at play here, wouldn’t it cause [Karsi] to fight that much harder to get back to her children?” Regardless, like so many others, Karsi serves her purpose in the story before being unceremoniously murdered out of the plot. She is remembered, not as a person, but as Wildling Mom #4.

engage with each individual enemy on a human level

The oversimplifying motivations of institutionalized motherhood litter the rest of Game of Thrones, too, with nearly every major mother figure being defined by her willingness to sacrifice herself for her children. Meanwhile, the fathers are allowed to share selfish, misguided, complicated, and often even contradictory relationships with those same children. But the mothers are just that: the concept of a biological instinct first, a human being with complex emotions second.

It certainly isn’t just Game of Thrones, either. In fact, you’ll be hard pressed to find nonbinary portraits of motherhood in any popular medium. In videogames, however, the pattern is particularly gross. As Bianca Batti and Ashe Samuals from Femhype point out, moms appear more useful to videogames as plot devices than as actual characters. Like many other female characters, the mother’s death or absence serves as motivation for the (usually male) protagonist. From God of War to Mother 3, Among the Sleep to Animal Crossing, mothers are addressed as caricatures of compassion or neglect; either Good Mom or Bad Mom, but removed from the story nonetheless. As Batti from Not Yo Mama’s Gamer writes, in “both constructions of either mother-as-victim or mother-as-monster, the mother is the object of the protagonist’s action—be the action one of seeking to reunite with the victimized mother or seeking to push the monstrous mother away—and not the performer of action. She is an object, not a subject.”

While mothers are busy getting refrigerated, there’s no shortage of videogame dads who capture the multiplicity of a three dimensional human being. Critics typically reference obviously dadified titles like The Last of Us, The Walking Dead, and BioShock: Infinite—all of which feature characters who find purpose and power in fatherhood rather than passive absence. But, in truth, dadification runs much deeper than just the many game plots that focus on paternal relationships. In fact, the list of paternal videogames is about as long as the list of videogames that exist overall.

Adrienne Rich says that the shift toward patriarchy in human consciousness happened the moment the father realized that the child the woman gave birth to was not a gift from nature, but in fact his own offspring, who could “make him immortal, both mystically, by propitiating the gods with prayers and sacrifices when he is dead, and concretely, by receiving the patrimony from him. At this crossroads of sexual possession, property ownership, and the desire to transcend death, developed the institution we know: the present-day patriarchal family with its supernaturalizing of the penis, its division of labor by gender, it’s emotional, physical, and material possessiveness.”

The dadification of games took place long before fatherhood became the focus of a few “gritty” big-budget titles. As an echo of our culture, the paternal mentality has defined videogames for most (if not all) of the medium’s existence: from Space Invaders to Pac-Man, the notion of protecting your territory, conquering death through iteration, and measuring success through monetary gain birthed the medium, and continues to dominate game design to this day. By and large, the language of Game Overs and leveling up through violence subsists on the values of patriarchy. Aside from just the obvious lack of mother-centric stories, paternal biases define what we’ve come to expect of games as players, critics, and creators. Like the male gaze informing so many shots in film, our culture has tailored the container of a videogame to only fit male content.

In the margins of the debate on what constitutes a videogame and what doesn’t, you will find some vague and ill-defined notion of what maternal gameplay looks like. I don’t think we’ve ever seen the true shape of a maternal videogame, but I definitely know what it is not. In Spike Jonze’s Her, a film which understands videogames on a level few others even bother trying to, the protagonist’s female friend is in the midst of developing a videogame called Perfect Mom. In the scene where she finally reveals Perfect Mom, we are shown a woman being rewarded and punished for how well she performs domestic tasks. The player-character is awarded 30 points for pouring cereal into a bowl. Meanwhile, when her health bar runs low, it warns that she is “being neglectful” and subtracts 200 points for the oversight.

What would a truly maternal videogame look like?

Jonze spends a lot of time grounding the futuristic society of Her in the same cultural problems we face today. Sure, this society has surpassed singularity. But it still exists under a patriarchy, and technological advancements don’t solve the deep-rooted power struggles that come with it. Perfect Mom is a subtle reminder of that. Because while robots may have advanced enough to feel love in Her, motherhood—in all its primordial splendor—continues to be devalued through its invaluableness.

So we return to the million dollar question: what would a truly maternal videogame look like? You could say Cooking Mama or, if you’re feeling particularly asinine, Metroid. But a videogame truly born of woman would necessarily negate each and every unexplored assumption that persists in the vocabulary of domination, property, possession, and—by extension—misogyny. And while we may be incapable of understanding what that kind of uncorrupted experience of motherhood would be like—let alone what videogame momification might play like—one game released this year has come closest to doing just that.

There’s no doubt that Toby Fox’s Undertale relies on the inhumanly selfless portrait of motherhood, but it does so with a purpose (warning that spoilers abound for the game). Early on, after the player-character accidentally falls into the monster world, you meet a momish character named Toriel. Toriel wishes to protect your from all the harm human children face in the monster world, and teaches you that, when you meet a foe, you will have the option to fight (and gain experience points) or to show them mercy by figuring out a narrative puzzle that sorts out that foe’s issues. But the real catch of this revolutionary kind of anti-combat system comes midway through the game, when you are forced to fight Toriel herself as she stands in the way of your progress. Toriel has watched several human children die at the hands of the monster king, Asgore, who seeks revenge on the human world for trapping the monsters underground. She refuses to let you continue in fear that you will die at the king’s hand, and you in turn are left with a crucial choice.

The battle with Toriel is a long and arduous one if you choose to not attack her. Showing her mercy requires you to repeat the same difficult process over and over again, probably dying often, which only extends the battle even longer. Throughout, there is no indication that your non-lethal tactics are even working, causing many players to give up and just kill her. You murder Toriel because you don’t know what else to do—because it appears to be your only option. You murder Toriel because the Kingdom of Fathers has defined videogames through the language of gaining power at the expense of the mother. Later on, you learn that Toriel once ruled the monster world alongside Asgore. But when the king began to murder human children, Toriel gave up her crown and cast herself into the Ruins, dedicating the rest of her life to saving humanity.

Most players kill Toriel on their first playthrough, even if they’re aware of the game’s morality system. But this choice, rather than serving as a reflection of the player’s lack of moral fiber, instead holds the mirror up to videogames themselves. This, Undertale says, is the kind of player patriarchal game design produces: impatient, quick to quit, and more than willing to sacrifice their own mother and humanity in the name of…what, even? Progress? A positive feedback loop? This vague and arguably meaningless concept of “leveling up” through “experience points”—whatever the fuck that even means in this context?

Undertale does more than just criticize paternal game design, though. It presents the beginning of a solution. Instead of relying on an abstract system of damage and violence to resolve every single combative interaction the player encounters, Undertale gives you the chance to engage with each individual enemy on a human level. If you choose, you can pay attention to what they say: to their wants, needs, and experiences in order to win. Arguably, doing that even makes for a much better game. This kind of game design also thinks more of a you as a player, intellectually-speaking, than the kind of game that names you king for pressing a button faster than another person. Undertale’s game design not only respects your ability to think through a problem, but also your basic instincts as a human being.

Undertale does more than just criticize paternal game design

Which brings us back to the other million dollar question: why, despite all logic, is motherhood considered too boring, lame, or otherwise undeserving of its own explorations in pop culture, particularly videogames? Publishers literally throw money at designers who want to create a game about a violent paternal journey. But titles like Might and Delight’s Shelter and Shelter 2—which casts the player as a mother in the animal kingdom—are forced to subsist on meagre funds. But what makes one gender’s system of motivations and instincts more interesting or valuable or even “game-y” than the other? Why is destruction inherently more “fun” than creation? Because, from where I’m standing, motherhood should, by all logic and definition, be seen as the ultimate experience of empowerment. As anyone who has birthed a project—from a novel to a building to a business to a videogame—can attest to, you must endure a long and difficult gestation period before you produce work that you can feel truly proud of. So imagine that, but in the creation of a human person. Now imagine that, but as the guiding principle of game design.

As games like Undertale show, maternal game design isn’t just about telling worthwhile yet disregarded stories. The popularity of paternal game design is indicative of deeper issues, ranging from how we as a society measure success and who and what our laws protect. But one thing is clear. As Rich says, “the mother’s battle for her child with sickness, with poverty, with war, with all the forces of exploitation and callousness that cheapen human life needs to become a common human battle, waged in love and in the passion for survival.”

It is difficult for a society that favors consumer ideals above all else to imagine a world truly born of woman. But “the repossession by women of our bodies will bring far more essential change to human society than the seizing of the means of production by workers.” We must try to imagine, not just for the sake of the women who we sacrifice daily in the name of conquest and power. But because everything flourishes in a world where mothers–begetters of planet Earth—reclaim their own identities and bodies. “In such a world women will truly create new life, bringing forth not only children (if and as we choose) but the visions, and the thinking, necessary to sustain, console, and alter human existence—a new relationship to the universe. Sexuality, politics, intelligence, power, motherhood, work, community, intimacy will develop new meanings; thinking itself will be transformed. This is where we have to begin.”

After decades of paternal game design, I am eager to unleash the potential of videogames born of woman. Motherhood deserves more than a cursory glance, and play deserves the benefits of creation instead of destruction. If and when that will happen, no one can say. But in 2015, we captured a glimpse of what fruit it can bear.

December 18, 2015

This real-life injury simulator is fascinating if a little gross

Researchers from the Center for Advanced Surgical and Interventional Technology at the University of California, Los Angeles used detailed CT scans of human legs to create lifelike simulations of leg injuries to train medics.

“Our goal in this specific project is to train medics to be able to deal with these sorts of injuries quickly and efficiently,” said one of the researchers, Jeff D. Eldredge, in an article for Motherboard. “When they train they have to feel the anxiety of seeing a real injury, and that’s the important aspect that’s hard to recreate.”

The injury simulations, featured in the video above, show bullets entering and leaving a leg, as well as blood rushing out of the arteries and veins. The video also features the construction of a finished virtual model of bones, skin, flesh and gushing arteries.

The research team at UCLA aimed for the simulations to replace the real animals used for medical training by students. The team says that the simulations are detailed enough that the future medics can train in a safe virtual space and still get the necessary experience without involving live animals.

“If we can recreate that sort of feeling of anxiety and call-to-action in a virtual environment, I think that’s going to be a really effective tool,” Eldredge said.

Here, have a free mixtape of JRPG music on us

You know what we like? Yes, videogames, but apart from those. No? Music, silly. Yes, we like music, and we especially like game music. You probably do too. Why does this matter right now? Well, we have a little gift for you.

If you didn’t back our Kickstarter to reinvent our print magazine then you wouldn’t have received the special mixtape that we gave out on December 4th. It’s called “Run 2 The End of the World, Vol 1” and it was put together by freelance film and TV composer Julian Wass for us. The whole mixtape is a love letter to classic SNES scores and features tracks from the composers of Earthbound, Chrono Trigger, and Xenosaga.

we love you

See, you should have backed our Kickstarter! But, don’t worry, we love you, and think you should also get to listen to this mixtape, so here you go—a full, free download of the entire 27-track mixtape.

Think of it as a little Christmas prezzie from us. (You can also click the image below to get the download.) The entire track list is below and, so you know, the last track is a bit of a bonus as it’s never been released before, too.

RUN TO THE END OF THE WORLD VOL 1

ETHEREAL – Hip Tanaka

DREAM – Tsusaka Masuko

HAPPENIN – Julian Wass / Mitsuda

URUSEI BGM 5 – Fumitaka Anzai

SILENCE – Yumiko Kanki / Naoto Ishida

MARIDIA – Kenji Yamamoto / Minako Hamano

AMBROSIA – Tsugitoshi Goto

INTO THE WILDERNESS – Michiko Naruke

STAMP MAKING – Hip Tanaka

SATMOMI TADAHI’S PHARMACY – Hidehito Aoki / Misaki Okibe /Kenichi Tsuchiya /Shoji Meguro

GOOD NIGHT SEE YOU SOON – Soyo Oka

STILL OF THE NIGHT – Hiroki Kikuta

SHINING CORAL – Sadao Watanabe

BREEZY – Nobuo Uematsu

HOME VILLAGE ARUNI – Yasunori Mitsuda

THE LUNARIANS – Nobuo Uematsu

GUMI VILLAGE – Hip Tanaka / Keichi Suzuki

THE MAZE OF DREAMS – Hip Tanaka / Keichi Suzuki

DREAM SHORE – Yasunori Mitsuda

ENDING – Tsusaka Masuko

APPLENUTS / THE RETURN HOME – Hip Tanaka / Keichi Suzuki

GAME OVER – Tsusaka Masuko

SAD SEQUENCE PRELUDE – Fumitaka Anzai

TAKE MY HAND – Toto

LE TRESOR INTERDIT – Yasunori Mitsuda

SMALL OF TWO PIECES (WAVE EXISTENCE MIX) – Julian Wass / Mitsuda

NEW AMSTERDAM – ギラ BLADES ft. Special Rapper Guests

Driving to work is a kaleidoscopic nightmare

I dunno about you, but when I drive to work in the morning it’s exactly like zooming through the crazed eye of a protean god, high as shit, as they fall helplessly and perennially through some rapturously psychedelic wormhole. Yep, that’s precisely it. So when Niklas Ström rocks up with something he describes as a “great realistic game about driving to work,” and it resembles that scenario just described, I’m impressed and can’t acknowledge the accuracy of the work fast enough.

Only kidding, I don’t drive to work.

But I have done. And so I know of that glaze that sits across your skull, like a morning dew thick and stringy, screwing with your brain and weighing down on your eye lids. I know what it can do to you. In fact, years before I could drive, I had a paper round, I used to get up at half five in the morning and cycle for 20 minutes. Sometimes I fell asleep with my eyes open, still somehow watching the road as I pedaled, and it could have been up to 30 seconds before I came back round to my resentful semi-consciousness. The light always hurt my eyes when I did.

leaving only the spiraling shock of it all.

The only way I knew I had slept is because I couldn’t remember cycling past the usual sights that morning. A police station. A school. A lonesome pub. Had I even swerved around parked cars? I had, and it’d freak me out. (That’s nothing: I used to fight close friends and my parents, even managed to empty my bladder in the bathroom once, all while sleepwalking.)

The mornings, they be weird once you’ve left your bed earlier than you’d like, is all I’m saying. You become like a groggy after-drunk pleb, dropping keys, stumbling into corners. And millions of us have to drive to work like this? Blurred vision, muted sounds, an ever wavering state of somnambulism; this is what we tolerate. And so maybe it isn’t such a stretch to imagine that driving to work, with all the motor-kinetic commands it puts on us, when tired and rushed isn’t unlike Ström’s CAR ON A STICK. That is, like playing Super Hexagon with all the challenge removed, leaving only the spiraling shock of it all.

You can change the colors that flock around you in the shape of roads and barriers at the push of a number key. Rainbow blocks become brown smears or purple knives. Hit any of the QWERTYUIOP keys (which is also the sound the game will force out of you) and the road will fall away entirely or reform as some other frightening structure of sharp lines, or worse, a giant smear of repeated sprites. It’s beyond surreality. Your other option is to hit the Space bar and let it randomize before your eyes like the never-ending flicker of icons on a fruit machine.

You can also drive. The car, on its stick, can accelerate and decelerate (or, the background can, at least), and it can turn sharply to the left or right. It’s like you’ve been playing an old 2D driving game and fell into its kill screen. There is no end and you will not get to work. You can only keep driving and watch as the colors fly into your eyeballs to the appropriately ecstatic bang-bang of the music, a mesmerizing arrest falling over your body. Staring at it blank-faced for several minutes comes highly recommended.

The Year in Feels

If we had access to some grand compendium filled with every single emotion that videogames make us feel, it would probably waste most of its words trying to describe fun. But as a concept, fun is primitive. Fun is escape. Like a dog chasing a tennis ball or a crow sliding down a tin roof, fun is intuitive. Fun is smashing your thumb down on the square button while Kratos slings around his orange blades. Fun is nailing that QTE and watching Kratos pull out the cyclops’ eye. Fun is when the red blobs come out and makes Kratos stronger, so that next time you push square his chainblades sling longer and harder. Fun is release.

But fun can also get stale very quickly. Even though videogames have already begun to reach beyond the concept of “fun” to carve out their own emotional lexicon, they’ve never broken quite as much new ground as they did this year. From smoldering teenage infatuation to hopeless desperation and real-life tears of joy, 2015 felt like the year that people up and went for it, unleashing their deepest emotions without so much as a hint of reservation.

///

It starts with denial. Three dudes in button-up shirts and one bewildered-looking woman sit in a semicircle, listening intently as an industry executive slowly lifts the veil on a new project. When familiar images of a blond spiky-haired man and his big burly sidekick start to pop up on the screen, the men clutch at their hairlines in agonized disbelief. One of them climbs onto his chair. Another starts to mutter under his breath: “No. No. No!” The word R E M A K E spreads across the display, and nobody even has to tell them it’s a Final Fantasy 7 remaster: they know. The ensuing freakout is familiar to anyone who’s doggedly followed a cherished videogame series, but there’s an almost sobering voyeurism to this video, like peering in at these guys in a moment of private ecstasy.

With platforms like Twitch and YouTube Gaming still gaining meteoric traction, esports is more popular than ever, and players are in closer proximity than they’ve ever been. But the extent of that human interaction has jumped way beyond fleeting teamwork and Pokemon crowd-play. At the League of Legends World Championship, Marcus “Dyrus” Hill—the Tim Duncan of LoL—announced his decision to retire from the game with a fumbling tearjerker of a farewell speech that had even the interviewer struggling to find words. It’s the kind of moment that translates beyond esports and even beyond games; Kevin Garnett’s “anything is possible” celebration and Kevin Durant’s moving MVP acceptance speech come to mind.

It starts with denial.

It’s a strange instinct to wonder whether games can make us cry. Not only is it an awkward system of emotional currency that equates tears with sentimental aptitude, but it fails to acknowledge how those emotions are created. Even though esports have only been mainstream for a few years, they’ve built their massive followings on the diligence and fervor of their player bases. It’s not an orthodox angle, but it denotes a major fork in the path between games as systems for emotional investment, and games as self-contained emotional experiences.

///

For most videogames, emotion has always been more of an afterthought than a prime virtue. In a majority of cases, gravitas feels either out of place (Gears of War), contrived (To the Moon), or directly at odds with what’s happening elsewhere in the game. This year’s Rise of the Tomb Raider, like its 2013 predecessor, pushed a bittersweet “honoring father’s legacy” premise that felt completely detached from its ultraviolence.

Feelings worked best this year under the delicate care of the “walking simulator,” a genre known for prioritizing dramatic, aesthetic, and artistic appeal over fun. It doesn’t jive too well with the base utilitarian Fun Value we tend to break games down into, but the ability to hone in on story beats and thematic elements without drawn-out grinding or combat gives them a sense of focus that’s completely absent from your average 50-hour RPG.

That being said, these games haven’t done much to flip the anti-fun stereotype. The walking sim poster child Dear Esther, from UK-based studio The Chinese Room, was essentially a long hallway with tripwires that’d play long monologues after being triggered. Paired with the solemn, elegiac voiceover work, it was hardly a populist triumph.

The Chinese Room’s 2015 effort Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, by contrast, had an almost Spielbergian everyman appeal, tapping both the pastoral beauty of the English countryside and the solitude of the post-apocalypse in equal measure. Rapture’s method of filling that empty void was almost sublime in its warm serenity; vistas of rolling meadows and firefly manifestations of human spirits instantly related the game’s poignant themes of loss, sacrifice, and love. Paired with the approachability of Dan Pinchbeck’s script and gorgeous orchestral arrangements from Jessica Curry, there’s a grandiose, cinematic sense of production to the entire work. Each vignette takes on its own life within the larger tapestry, deftly swelling and subsiding and building up again into eventual catharsis. It’s a dense work of moving honesty, gathering the individual talents of its creators to create one cohesive whole.

A host of smaller games leaned mostly on personal experience, creating a fleet of smaller, weirder, and completely singular works of raw, unrefined passion. Most of these games feel so deeply personal that it feels wrong not to pair them with the names of their creators. Just like Do The Right Thing seethes with a brand of impassioned frustration unique to Spike Lee, games like Nina Freeman’s Cibele, Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide, Kyle Seeley’s Emily is Away, and Matthew Burns’ and Tom Bissell’s The Writer Will Do Something all carried the emotional stakes to immediately suggest auteur status.

It’s easy to picture a lone artist creating these works in a dim room

Like Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska or Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago, it’s easy to picture a lone artist creating these works in a dim room, writing out scripts and hashing out aesthetic details while recalling some of their most traumatic or most cherished experiences.

The Twine-produced choose-your-own-adventure The Writer Will Do Something is probably the rawest of the bunch. Using onscreen text to convey the debilitating pressure of high-budget videogame writing, it feels like a PTSD flashback, with roundtable arguments escalating ad infinitum and an ending that offers no clear solutions. The fact that this game exists at all feels like an act of bravery: most people wouldn’t leave a bad comment anonymously on Glassdoor, much less attach their name to an industry exposé.

Nina Freeman’s Cibele and Kyle Seeley’s Emily is Away work well as companion pieces. Both use computer interfaces to tell their stories, and both call back to the early- to mid-2000s. But the interface-as-setting isn’t so much a generational statement as it is a way of recreating familiar digital scenery. In Emily is Away, which takes place entirely within AOL Instant Messenger, the creaking door alert sound is an instant time jump to the days of shitty MySpace HTML tweaking and awful XP-era interface design. With the game’s main conceit following two would-be lovers over a five-year period, AIM functions as a séance for modes of human interaction that have long been obsolete.

Nina Freeman’s Cibele pulls a similar trick, but injects its creator directly into the narrative. As the player navigates Nina’s desktop, they find samples of her old poetry; pictures of her with friends; selfies she’s taken in lingerie. It all feels unsettlingly private, but gives the player unprecedented access to the awkward spontaneity of her online love. The full-motion video sequences break up the interface’s carefully-crafted immersion, but it’s all on purpose: this is what a “living, breathing world” really looks like, and Cibele has the audacity to welcome it with outstretched arms.

///

The influential Russian film director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein saw cinema as a complex vehicle that worked best when “exercising emotional influence over the masses.” As a lifelong student of the form, his obsession with film’s intricate machinery culminated in some of the most influential films of the 20th century.

Although they’ve had their John Carmacks and Will Wrights and Sid Meiers, videogames haven’t quite met their Eisenstein. Then again, videogames are more systemically complex than films, and it can be hard enough to make something that’s consistently fun, much less to build something that holds any semblance of emotional influence.

this is what a “living, breathing world” really looks like

After releasing the critically acclaimed walking simulator The Stanley Parable in 2013, Davey Wreden withdrew from the public eye, struggling to pin down his place in a universe filled with the interpretations and opinions of outside observers:

Every time I turned to someone else’s opinion of the game, I felt less sure of my own opinion of it… So: to help myself better understand and isolate the feeling of depression around the GotY awards, I wrote and drew a comic to explain what I had been feeling… I just wanted to put it into some words to help make it less nebulous and unknowable.

The Beginner’s Guide, released in October of 2015, is Wreden’s second attempt to deconstruct—and then understand—the psychological inner-workings of his art. The game is a labyrinth, not just in its unsolvable puzzles and oppressive imagery, but in its complex weaving of characters and creators, players and developers, reality and fiction. To interpret The Beginner’s Guide is an impossible task; there’s nothing beginner-friendly about it. But to Wreden, a man whose prime obsession has been to make sense of his art and his status as a creator, it’s the perfect starting point.

At the end of The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden makes a desperate plea to Coda, his imaginary game-developing muse: “I know that I did an awful thing, and I’m doing it again right now: I’m showing people your work—but I can’t stop myself from doing it. That’s how badly I need to feel something again, like I’m an addict.”

Most people have their own hang-ups, whether it’s detachment or addiction or an insatiable need for self-validation. For about as long as they’ve been around, we’ve cherished videogames as a way to escape from these vices and from the many other stresses of everyday life. But games can serve the opposite purpose just as well, and the most emotionally resonant games of 2015 opted to confront us with truths instead of helping us avoid them—whether they were ugly or embarrassing or cheesy or pathetic. It might not sound like much, but it’s a solid foundation for a more personal, more incisive, more emotional videogame medium.

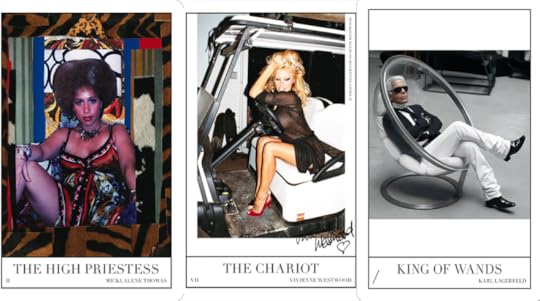

A tarot card deck designed by world-famous designers and artists

We all know artists and designers are practically fortune-tellers, able to pick up on future trends and styles when creating and reimagining their art. But when they put that divination talent into a strangely fitting literal manifestation, the results are breathtaking.

Contemporary Magic: A Tarot Deck Art Project is a collection of tarot card designs, created by 78 esteemed designers and artists, and put on display in a travelling exhibition. Among the artists commissioned were Ultra Violet, Andres Serrano, Francesco Vezzoli, Nan Goldin, as well as designers Christian Louboutin, Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Jacobs and Dame Vivienne Westwood.

The exhibit is curated by Stacy Engman, and has traveled to distinguished museums across the country, including the Dali Museum, Andy Warhol Museum and Virginia MoCA, amongst others. The tarot cards are now being compiled into a tarot card app by Playdots, Inc, for everyone to experience. Card designs range from eerie and majestic, to colorful and brash, each striking in their own way, while carrying the style of their respective artist.

“Each matched to a card based on parallel archetypes in their artwork and themes in the card,” reads the app’s description. “The show is a celebration of the great creative icons of our time, all reflecting universal and iconic facets of visual expression.”

You can download Contemporary Magic: A Tarot Deck Art Project here.

The year in boardgames

“2015 is the year of the board game,” I told everyone I knew. I wrote it out in emails. I typed the words out in text messages. I casually said it over the phone. If friends or family wanted to get me something for my birthday, a PlayStation gift card would not do: I had a manicured Amazon wish list pruned with all the games I wanted to play. Sure, I occasionally played games on a screen. But people know, now: when they invite me over for dinner, they better be ready to play Love Letter or Netrunner or whatever I’ve managed to stuff into my backpack.

I’ve seen others go analog, too. Our gaming PCs and high-fidelity graphics cards may be able to render each follicle on every neo-futurist assassin’s soul patch, but they’ve got nothing on the experience of tabletop gaming. The finest AI can’t manufacture the electric betrayal in a late-evening game of Coup, or the cold social gerrymandering in the Game of Thrones board game. In that way, tabletop gaming is to videogaming what theater is to cinema production: it’s smaller, more intimate, fueled more by social rapport than production.

There’s a renaissance of cardstock and meeples in the works. Analog is in. Even if a solar flare fries every smartphone and CPU and society reverts to the Stone Age, there will still be boardgames. Below are some of the best examples of analog gaming to come out in 2015.

Pandemic Legacy (Season 1)

A surprisingly emotionally charged year-long plague simulator.

This is probably the most exciting (and hyped) release all year, because every piece of the game crafts a distinct, urgent experience. The original Pandemic was a tense, timed puzzle that wrapped up in around an hour. Pandemic Legacy doesn’t reset when the group finishes for an evening. The Legacy format prompts its players to tear up cards, unbox secret compartments and mark up the game board as the virus mutates and cities crumble under duress. At the end of a full playthrough, a copy of Pandemic Legacy will be unusable, scarred with memories, and utterly unique.

This iteration of Pandemic is as tightly wound as its forebear, but Legacy is specifically built to produce a serial narrative. The characters are archetypal—Medic, Researcher, Scientist, etc.—but each player gives their character a unique name. When shit goes down, they receive ever-more punishing psychological scars; they bring in their siblings and friends to help; they die tragically or disappear into wreckage. As characters succumb, the players have to withstand escalating punishment as the strains of pathogen mutate and the objectives evolve. The group might think they’ve cured the black virus only to see it grow more vicious and impossible to treat. It’s like a less self-aware tabletop relative of the Russian plague simulator Pathologic.

Pandemic Legacy embraces the tactile presence of tabletop gaming, which is likely what has made it so beloved. There’s something weighty about dismantling the game engine or permanently opening dossiers as a reward. The game itself is designed to become a relic: it documents the group’s narrowest victories and breaks down in response to their failures.

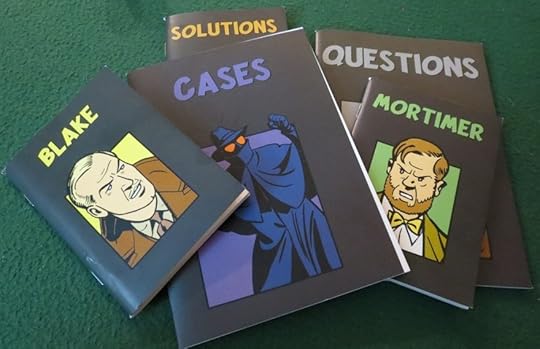

Witness

Belgian subterfuge Telephone.

Four players seat themselves in a specific arrangement, according to their characters. The profile pictures are brightly colored, hearkening back to the glory days of the old Belgian Tintin magazine. One player reads the details of a case out loud: a jewel theft, a rogue spy, a grisly murder. The players pick up their casebooks, furrow their heads in frustration, commit the details to memory. After a moment, everyone puts down their casebook, and two players whisper from memory everything they read to the other two. A pause, then another round of whispering between other players, and another, then another. The details travel around the table. At the end, the players furiously scribble everything they learned on a scrap of paper, and one player reads out a series of questions for everyone to answer. The winner is the player who got the least wrong.

Witness is brief and full of embarrassment. A game of Witness is more or less twenty minutes of cramming for an exam via Telephone: players with the best short-term memory will shine. Those with poor retention will be scorned. It’s obvious when someone has forgotten his clue. Yet even with a few missteps, the structure of each round means that the players can often piece together enough clues to form a coherent theory. Rounds are short enough that, even when a group is hopelessly lost, they can easily finish and move on to a fresh challenge.

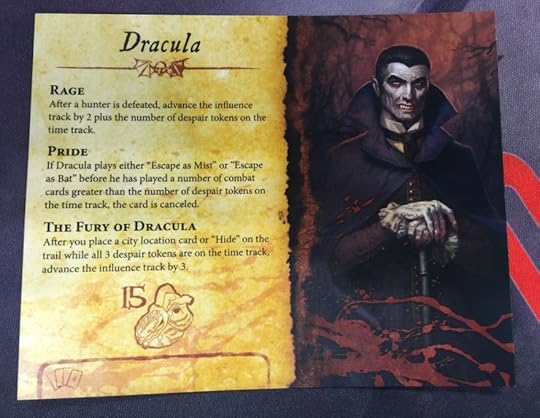

Fury of Dracula, 3 rd ed.

Vampire hunting, alone or with friends.

Fury of Dracula is a game about the chase. One player, controlling Dracula and his minions, threads a careful path across Europe, leaving fresh vampires, dusky tombs, and strange weather in his wake. As hunters, several other players spread a wide net. They buy garlic wreathes and train tickets as they try to find some trace of the Count’s trail. The game ends either when Dracula has garnered enough influence to rule the people of Europe (or at least keep everyone from leaving their homes after dark) or the hunters have killed him.

The game is actually quite old, printed in 1987 by Games Workshop, but the third edition, released this year, represents a trend toward building games in which mechanic is wholly subservient to theme. Travel has been simplified, timers sanded off, dice eliminated. Combat in Fury of Dracula is tense, lasting no longer than six rounds, and serves to underscore Dracula’s intimidating power, as well as the fragility of the hunters. There are no numbers here: only tense, nail-biting worry. And wooden stakes.

Fury of Dracula is best played in character. The game is mechanically engineered to encourage players to despise Dracula for his perfidy; as such, it helps to play Dracula with a hint of arrogance. In one game, as the Count, I confronted Mina Harker and a now-ancient Van Helsing several leagues from Castle Dracula on the eve of my victory. I was drunk with power. A well-placed stake, some garlic, a holy incantation, were just enough to put Old Vlad down for good. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief: the hunt was over. As in Bloodborne: the intensity and release hurt so good we didn’t even care who’d won.

Codenames

A psychological word game.

Two code masters, referencing a shared private grid, point their team to a network of informants via simple verbal clues. Imprecise wording could mean hitting a civilian, tapping an assassin (resulting in an instant game over), or giving the other team points. A well-thought clue could mean an easy win. It’s deceptively simple.

Codenames is a new gateway drug for boardgaming. The explanation and setup are easy enough to lure an uncle or grandma to the kitchen table, and it’s simultaneously cooperative (agent and codemaster) as well as competitive (red and blue). If a master is trying to push agents to “bond” and “tick,” she might say “gadget 2” which inadvertently could point agents to “apple.” Agents might completely miss certain hints: knowing the cultural and psychological subtext of a single word is vital to success.

Like Chess, Stratego, Poker, or a bunch of other games I’ve never had the patience to play more than a few times, Codenames rewards mental acuity as well as aplomb; it is accessible enough for people who don’t frequently play games and complex enough to invite mastery. What sets it apart is its social and psychological dimensions. Depending on the group, the same clue might carry a completely separate meaning in one session to the next, and the box is stuffed with so many cards that there’s little risk of the game getting stale with use. Creator Vlaada Chvatil is known for honing intricate systems, but Codenames might be his most compulsively playable game to date.

Mysterium

If Clue were a séance.

In the wake of a grisly murder in Mysterium Mansion, a wave of psychics descend on the old manor to divine the details of the crime. One player, playing the ghost, must communicate a specific message (person, location, weapon) to each psychic via extremely abstract dream imagery. If each psychic can discover his/her three answers in seven rounds, the group has a chance to cull the true perpetrator, etc. from the tangle of visions.

Codenames and Mysterium are odd cousins. Where the first relies on careful, deliberate verbal cues, the latter thrives on misdirection and abstraction. In Codenames, failure is to be avoided at all costs; any failure in Mysterium becomes a kind of glorious theater that unfolds after the game as psychics can finally ask the ghost questions. “How the &$^# was a mouse riding a unicycle and raining knives supposed to point me to the hunter?”

Mysterium is also, without a doubt, the most visually stunning game on this list. Its sturdy deck of oversize cards brims with colorful dream imagery; a large illustrated clock counter tracks the hours in the game. The players’ success in the game hinges upon very subjective imagery, its aesthetic appeal, and the complicated psychology of getting into each others’ headspaces. If a psychic and ghost “get each other” outside the game, they’re more likely to intuit a vision, which is potentially as satisfying as it is personal. Or they won’t. Success is sweet. Failure is rarely as disappointing as it is hilarious.

Android Netrunner: Data & Destiny

“Game-changing” doesn’t do it justice.

Three years in, the two-player, collectible card game Netrunner is in top form. Its major recent expansion Data & Destiny deserves a place on this list not just for what it introduces into the Netrunner metagame but also for what it represents in the game’s larger development arc. Each consecutive release tips the balance of power in favor of a specific faction, a strategy: a single asset might render an old play irrelevant, or a new card might finally slot into a burgeoning archetype. A good Netrunner release will subtly but significantly shift the game in some new direction.

Data & Destiny casually upends everything. Beyond providing a slew of muscular new cards for the last of the game’s factions—the data-driven marketing network NBN—the box contains three new micro-factions for the hacker “runners.” The new factions aren’t simply subtle parodies of their runner counterparts: they are reinventions. For the punk Anarchs: an insatiable computer virus who destroys the board. For the artistic Shapers: a Frankenstein’s monster who hacks servers as a kind of performance art. And the Criminals, always in it for the $$$, have a security agent who hacks for her day job so she can feed her kids.

From a purely conceptual standpoint, Data & Destiny feels fresh, but the cards here have only just begun to be digested by the Netrunner community. The game is in process of constantly being reinvented: a card *breaks* the game, and a new combo breaks that card, and so on and so forth. There is no shortage of imagination here.

Lead photo by Paulo Renato on BoardGameGeek.

Pandemic Legacy photo by yoppy on Flickr.

Witness photo by Daniel Thurot on BoardGameGeek.

Fury of Dracula photo by Cody Jones on BoardGameGeek.

Codenames by Wayne McIlvaine on BoardGameGeek.

Mysterium photo by lelo arrowsmith on BoardGameGeek.

December 17, 2015

Metaphor or not, these little towers in test tubes are beautiful

There’s experimental housing, and then there’s housing created in a test tube. Rosa de Jong creates the latter.

To use Zoolander terminology, these are homes for ants. There are no ants here, but the scale is appropriate for the little critters. Instead, what you have is a series of cylindrical dioramas, wherein buildings float in midair on the earthen bases. The facsimile of soil beneath these buildings tapers like the flame coming out of a rocket engine. In a sense, these scenes have achieved liftoff. As part of her Micro Matter series, De Jong had created all sorts of homes, from experimental towers to teepees, with a smattering of silos and smaller domiciles in the middle.

The test tube used in the Micro Matters series function primarily as convenient vessels, but they also serve as a reminder that housing can certainly be experimental. Indeed, America’s history of public housing is often referred to as an experiment. This attitude is not always for the best: by virtue of being experimental, such developments represent a small percentage of the overall housing stock. Experimental housing remains a curiosity—sometimes beautiful and sometimes a failure. Rosa de Jong’s houses in test tubes, on the other hand, are consistently beautiful. If only they could scale up.

A beautiful 3D platformer to celebrate our worship of coffee

It’s almost surprising that there isn’t a giant Starbucks logo to be found among the pastel-colored environments of Caffeine shown in its first trailer. If it were made back in the ’90s, during the height of the genre it belongs to—the 3D platformer collect-a-thon—it would likely have some form of corporate backing. Like that Zool platformer I played on my DOS computer; the Chupa Chups logo shining like a flowery beacon next to the candy cane meadows and green jello mountains. I was four, maybe five, and highly impressionable. I licked a lot of lollipops that summer.

But Caffeine isn’t from that era. And so it’s a game in worship of coffee for reasons other than paying the bills. You play as Steeper, a barista with a coffee machine for a backpack and an outrageous white curl for a haircut, as he missions to make the best coffee ever. This puts Caffeine more in line with the modern, metropolitan pursuit of locating the best coffee in town. If you go to a city and strike up a conversation about coffee with someone who drinks it, they will probably reel out a range of recommendations, places to avoid, perhaps even getting so specific as to tip you on preferred baristas. You don’t just drink coffee in a city, you enter a culture that thrives on entering every cup consumed on an unwritten league table, everyone an expert reviewer.

In Caffeine, the perfect cup of coffee has been decided, and so the discourse isn’t centered on what or where the best cup of joe is, but how can it be made. The answer directs the journey you’ll make throughout Caffeine, travelling across a sky island to collect the perfect ingredients to throw into Steeper’s backpack, whirring them around, and relishing the hot liquid result. But where Caffeine breaks off from its city-dweller’s fantasy is in abandoning the tall architecture of the metropolis and using Steeper’s quest as a reason to return to nature.

caves made of the purest sugar

As the trailer shows us, Caffeine‘s environments are, for the most part, bucolic. There are gardens where coffee bean plants grow and caves made of the purest sugar. From these you locate the ingredients you are after. But you are also encouraged by the music, which passes over you like waves of electronic water, to take your time, chill out between running errands, and gorge on the rustic vistas pepped up as they are in purple, pink, and green hues.

Even when civilization does sprout like a sharp-cornered weed on this island it is almost as pleasant as when it is absent. The interior design has the indulgence of a 70s luxury pad: hotel lobbies with crystal decorations and gigantic water features, open-plan apartments with luminous flora used as natural lighting next to cream-white furniture. And yes, the populace, too, is fittingly modeled and named after coffee as per Steeper’s example—Pressa and Lady Karmel for starters—almost as if acknowledging the hold coffee has over city folk. And if that doesn’t get the message across then the temples dedicated to the substance certainly should.

You can follow the development of Caffeine on Tumblr.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers