Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 178

January 6, 2016

The Dualism and Morality of “Golden Sun”

My father always says there are two sides to every story. There’s one party’s side, the opposing party’s side, and then the truth tends to fall somewhere in the middle.

Most videogames, however, exist in a vacuum of storytelling, where the player takes control of a set of heroes out to destroy a set of bad guys. Through this, they mostly attempt to capture and tell only one side of a story. Mario is good, and Bowser is bad. Sora wants to save the world, the Heartless want to destroy it. Link is the Hero of Time, Ganon the bringer of destruction. It’s a repeated formula because it’s easy (and because it works), but it also tends to make things somewhat superficial and obvious.

Golden Sun, the 2001 Game Boy Advance role-playing-game from Nintendo, then, manages to pull off something that not a lot of videogames are able to do: take a look at both sides of a story and use it to explore the complexities of real-world morality.

the truth tends to fall somewhere in the middle

The first two entries in the series, Golden Sun and Golden Sun: The Lost Age, together tell one complete story, but halfway through pull the narrative rug out from underneath the player. In The Lost Age, the player takes control of the antagonists from the first game, and the story from there delves into deeper ideas of morality, right and wrong, and starts to make the player wonder which side the “good guys” are on.

Golden Sun takes place in Weyard, a world kept in balance by the four basic elements of Alchemy: Venus (Earth), Mercury (Water), Jupiter (Wind), and Mars (Fire). Years before the game begins, the powers to control Alchemy were sealed away in an attempt to keep the world safe. Now, a rogue group of Adepts — the name for the in-game characters who can control the elements and have magical abilities — is attempting to relight the Elemental Lighthouses and break the seal on Alchemy, releasing its untold power unto the world.

This is all fairly standard Japanese role-playing game stuff, but, after spending the entire first game on a quest to prevent this from happening, the sequel deconstructs the player’s notion of right and wrong. You play as Felix, one of the antagonists from the first game, in an attempt to light the lighthouses, opposing the goal you tried to accomplish in the first game.

Slowly, more and more information about Weyard is revealed. Felix and his companions visit towns that are actually suffering from the lack of having the lighthouses enflamed. Lemuria—the ancient civilization based on the Atlantis-like myth—is in a state of continual decline, with the once rich civilization now devoid of its enthusiasm and creativity. (There’s also a not-so-subtle metaphor here: the leader of the Lemurian senate is named Lord Conservato, who is trying to keep things exactly the way they are).

Compare Lemuria with your visit to Izumo, a town that is on the verge of offering human sacrifices to a giant dragon that was awoken due to the player’s actions in the first game. For any area in the world that may have seemed to be better off with Alchemy restored, the second installment shows the other side, with other civilizations wrestling with the dire consequences of the player’s original actions.

The biggest reveal is saved for the end, though. The last location in the game is the frozen wasteland of Prox, home to the Fire clan that has been the “enemy” for most of the game. You learn that Felix’s parents aren’t dead; they have been held hostage in exchange for Felix’s cooperation. He was out to save his parents this whole time, not out of any selfish greed or lust for power.

A strong sense of self-preservation, not world domination, has been moving the characters

As you explore Prox, you discover that the only reason the members of the clan set out to return Alchemy to the world is because their northern-most continent is slowly being destroyed, and that the whole world is moving closer and closer to the overflowing edges of the planet. (Like early maps of Earth, Weyard is flat, with giant waterfalls surroundings its edges).

A strong sense of self-preservation, not world domination, has been moving the characters, cast as enemies, over the past two games. It paints them in a much different light than average videogame “bad guys.” Can the player accept the actions of the Fire Clan if they were done in an attempt to save their town and villagers (and by extension, its children and elderly) from destruction? Do the ends justify the means?

The ultimate decision boils down to this: If the Lighthouses are relit, then the world will stop decaying, but also might be destroyed in the resulting cataclysm. But if the lighthouses aren’t lit, then the world most definitely will be destroyed.

It’s a surprisingly dark take on morality and mortality, implying that the act of making a decision can be more important than blindly accepting a predestined fate. On the other hand, to make no decision is to condemn entire races and villages to certain death.

There’s no clear right or wrong. No clear “videogame trope” of which side is the “hero.” Even as the characters go to light the last lighthouse beacon, they are stopped by The Wise One, a god-like deity who originally tasked them with stopping the lighthouses from being lit. Even with the characters’ resolve to not let the world end, The Wise One attempts to stop them, claiming that the world will end either way: “It is inevitable. In time, one man will seek to rule over all. It is human nature, inescapable.”

Even then, the game even asks the player directly, in a simple Yes or No prompt that appears on screen, if risking this is worth saving entire villages over. The characters ultimately choose to oppose the Wise One, and take the fate of the world into their own hands. The Wise One then reanimates the player’s previously missing parents into a giant dragon that they have to kill in order to save the world. It’s grim stuff.

The results of the decision to light the Lighthouses is even further explained in the sequels, as the rest of the world has to deal with the actions of a few children. To some, they are heroes, but to others, they were help not asked for, returning a power back to the world that not everybody wanted.

There’s at least two sides to every story

But the world was saved. Weyard continues to exist, even with the power of the elements unleashed. However, in the process of unleashing these elements, the normal videogame role of hero is redefined. The player receives a much more complex look at the characters through the shifting viewpoint of the characters. Golden Sun succeeds in raising interesting questions about the human condition. How will a person’s upbringing and background affect their viewpoint, and what is the right choice when faced with the complex moral decisions of real life? There’s at least two sides to every story, and Golden Sun thoroughly investigates this.

And in that sense, Golden Sun presents players with a reality that transcends the game. Sometimes there aren’t right answers. Life isn’t as easy as black and white, and sometimes even the best of intentions can cause the worst of outcomes. It’s a hard lesson, but one that Golden Sun, despite its bright name, manages to get across, well, adeptly.

Golden Sun and Golden Sun: The Lost Age are available to play on the Wii U Virtual Console.

January 5, 2016

Drum machine manufacturer offers a more sensible take on Guitar Hero

TR-REC is basically Guitar Hero by another name, and it seems unlikely that any of the parties involved could object too strenuously to this characterization. The game is an exercise in conflating genres and media forms.

The self-described “pattern sequencing game” is made by Roland, a company more commonly known for its synthesizers, production tools, and drum machines. TR-REC is a digital facsimile of the latter, asking you to tap out a variety of sick-adjacent beats. This, in the digital world, might also be called drumming. Beat sequences are denoted using scrolling dots on the screen of your iPhone or Android device. Points are awarded for accuracy. As the game progresses, the beats become faster and more complicated. (Stop me if you think you’ve heard this one before.) By the by, Roland makes an instrument known as the “TR-8 Rhythm Performer,” which has basically the same interface as TR-REC. Go figure.

Being good at TR-REC does not make you a beatmaster

What is TR-REC? A game? A promotional tie-in? A tutorial? A veritable drum machine? All of the above, I suppose, and this isn’t necessarily the worst of things. The game reflects the now-decade-long convergence between games about music and the act of making music they seek to depict. The two are not yet one and the same, mind you. Being good at TR-REC does not make you a beatmaster, much as Guitar Hero expertise is not really the universe’s way of telling you that you are the artist soon to be known as Prince, but these two realms aren’t entirely unrelated.

Indeed, the parallel is clearer in TR-REC, where the game shares more interface elements with the actual instrumentation than Guitar Hero. Some of that surely has to do with Roland’s involvement with the game, but that is not a sufficient explanation. The sort of simplifying and reliance on buttons that music games typically require is less suited to a guitar—see Guitar Hero’s awkward implement—than digital drumming. In that respect, TR-REC, promotional tie-in though it may well be, is actually quite sensible.

Find out more about TR-REC, including where to download it, on its website.

A model for referencing videogames in literature

Generally when literature alludes to other media—Facebook, texting, film, the song “Hey, Soul Sister” by Train—my first reaction is to cringe. At its worst these mentions feel unnatural, lazy—the author’s gawky attempt to connect to the modern world or to an artistic tradition by simply referencing it. But even good media references can be jarring. Haruki Murakami’s thoughtful incorporation of jazz and classical music into his work, for instance, still has a weirdness to it.

Perhaps this can be pinned down to degrees of separation from reality. When reading a work of fiction, it is typically odd to see mentions of real-world media, because we then have to reconcile the fact that this media exists in a fictional world as well as reality. The fiction no longer exists within its own self-contained bubble, but rather one with the same kinds of consumable culture that we interact with every day in real life. That realization is a lot for the reader to take in.

The problem is that literature needs to be more contained than reality. Things cannot happen at random or without consequence. Events, dialogue, and narration need to connect to the greater thematic elements of the work. They need to serve a purpose. Otherwise, why are we reading?

Alex Gino’s George is a young adult novel centered around the eponymous ten-year-old trans girl. It reads like an analogue to Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Just as Blume’s work concerns Margaret’s cisgender experience of settling into her identification as a young girl, so Gino’s work concerns George’s parallel trans experience.

A quick word on George as a novel. I’m always apprehensive about “coming out” queer literature because authors tend to either martyr their protagonists for moral purposes or else make the narrative so unbelievably optimistic that it is difficult to connect to on a personal level. George, thankfully, is neither. It leans toward the optimistic, but within a more believable context. There are no strawmen villains, nor are there people who accept George at first reaction without question. It is written for queer young adults rather than the parents of queer young adults—a novel meant to show these young people that they aren’t alone, rather than help those parents process the young person’s plight. By this I mean that Gino doesn’t condescend to George; they treat her point of view with respect, on an equal level. And that really makes all the difference with queer young adult literature.

I’m always apprehensive about “coming out” queer literature

Now, George has one particular passage that shows exactly what well-implemented media references look like. This passage involves our titular character playing Mario Kart with her brother Scott. Although extremely different people—Scott is a stereotypically gross teen boy, unwilling to shower regularly, obsessed with gory horror movies and violent first-person shooters—they are able to bond over playing this videogame together.

The passage begins with Scott, in an uncharacteristically mellow mood, invites George to play Mario Kart with him. It establishes the current state of Scott and George’s relationship, suggesting that they used to spend a lot more time together.

“Scott hadn’t asked George to play video games in months. They used to play almost every day. George would come home after school to find Scott on the couch, watching wrestling and ignoring his homework. They would play until Mom got home and yelled at them to turn off the TV and get their homework done. Now Scott usually came home just in time for dinner, if not later.”

From here the two play the game together, enjoying the competition and the camaraderie. The ensuing passages work well because they smooth Scott and George’s relationship over, illustrate how they can get and have in fact gotten along despite how opposed their personalities are. Gino describes how they laugh together, work together to defeat the computer opponents and compete against each other in jovial sibling rivalry. This makes the coming reaction that Scott will experience regarding George’s identity much more believable.

But Gino doesn’t use Mario Kart solely as a device to show the unspoken affections shared between the two. They take it a step further by actually having the characters that George and Scott play as reflect and deepen their development. Whereas Scott chooses the bulky, brusque and evil Bowser, George selects Toad. To quote:

“She liked the happy sounds the little mushroom made. When she was alone, she sometimes drove as the princess, but she didn’t dare choose her in front of Scott.”

These character choices further enforce the dichotomy between the two characters, reveal how drawn toward femininity George is, and how drawn away from masculinity. This is pushed further by the final paragraph of the chapter, in which Scott persuades George to switch the a first-person shooter. George is quickly bored with the game, unenthused by its macho violence. Without condemning masculinity or violent games outright, Gino stresses their character’s repulsion from such stereotypically male attributes, emphasizing George’s feminine inclinations.

YA authors are fond of referencing media, perhaps as a way to foster a love of culture in its readers. But it often doesn’t feel organic. John Green is guilty of this, for instance referencing Gabriel García Márquez’s The General in His Labyrinth in Looking for Alaska. The character Alaska has many great works of literature on her bookshelves, General among them. References to General are apparently meant to connect Alaska to García Márquez’s philosophical musings. While not misguided, the connection feels forced, in essence borrowing literary import to beef up Alaska‘s message. Green’s references to General neither invite more character development nor bring much to the table aside from the name of an interesting novel. It is a barely veiled literary device used to make Alaska appear deeper than it is.

references media as a means to develop characters and their relationship

George instead references media as a means to develop characters and their relationship with one another. George is able to incorporate media into its story without using it as just another literary pretension, without the sense that the author is making lazy attempts to try to connect to the modern world. It is a natural-feeling occurrence of media within George‘s fictional world, one whose perfect sense and intelligent implementation prevents it from jarring the reader.

In the scheme of George, this Mario Kart section is a quiet interlude within the larger story. Yet it speaks volumes about the character of George and the dynamics in her home. That is why it works so well as a media reference. Without bringing too much attention to itself, making sure to make perfect sense within the context of a suburban child’s life, Mario Kart operates as a helpful tool to further articulate the author’s fictional world.

Turning Fallout 4’s world into 1950s-style animations

If you’ve played last year’s Fallout 4, you’ve doubtless seen the series of animated shorts that play upon starting the game up. Black-and-white and with scratchy audio, these videos turned the post-apocalyptic Boston wasteland of Fallout 4 into a comedic, 1950s-style cartoon. (If you haven’t seen these shorts, then you can easily catch up on them all over on developer and publisher Bethesda’s YouTube channel.)

Each of these shorts detailed one of the letters in the game’s “S.P.E.C.I.A.L.” system. This has been a staple of the Fallout series since its first outing in 1997. It’s an acronym that stands for Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility, and Luck. It’s these that you advance through the leveling system and that dictate your character’s effectiveness in different situations, whether that is combat, exploration, or conversation.

“This wasn’t 30’s or 20’s floppy rubber hose style”

When creating the cartoon series, the small Australian animation studio Rubber House had its work cut out: not only did the team have to communicate the individual elements of each letter in the S.P.E.C.I.A.L. ruleset, they also had to do so while adhering to the animation practices of the 1950s. This was the outline given by commissioning agency AKQA, who was working on Bethesda’s behalf.

Why the 1950s? It’s in keeping with the cheesy, anachronistic, and inappropriately cheerful (this is the post-apocalypse) adverts, manuals, and products of Vault-Tec, the omnipresent corporation that exists within the Fallout universe. (The corporation’s existence perhaps being a commentary on the persistence of capitalist practices no matter the state of the world.) While Vault-Tec is never really seen as an entity inside of the game except in the products that lie as debris around the wastelands, it isn’t faceless. Vault Boy, the company’s all-smiling, all-winking mascot is a typical 1950s model of the ideal man, complete with golden curls. Naturally, he is the star of Fallout 4‘s animated shorts, parodying the government-made training films meant to prepare citizens for the potential disasters of nuclear war—the most famous of which being 1951’s “Duck and Cover.”

Perhaps you think Rubber House’s task simple. Surely all you need to create shorts that have a 1950s feel to them is to degrade the sound and turn down the colors. But as the studio outlined to Motionographer in a recent interview, there’s much more to it than that, at least, if you plan on going the whole hog. “When we were designing it were insistent on getting the period right,” said Rubber House co-founder Ivan Dixon. “This wasn’t 30’s or 20’s floppy rubber hose style; it had to feel like late mid to late 1950’s, which is less spheres and sausages and more angular/designed.”

The studio researched the 1950s style of animation by watching plenty of The Flintstones and, when drawing up their own designs, always asking “Could they have done this? Would they have done this?” In other words, the studio made painstakingly sure to adhere to the vintage practices under which animation of the 1950s was produced. “This means setting up parameters such as, for instance, the maximum number of planes that can be used in a parallax or avoiding storytelling tropes that wouldn’t have existed back then,” said the other Rubber House co-founder, Greg Sharp. “We even went as far as making the editing slightly erratic as sometimes happens with analogue equipment.”

at least one violent Vault Boy death per episode.

Crucial to achieving the effect was the audio. And for this, Rubber House teamed up with previous collaborator and sound designer James Brown. He followed the same restrictions on audio as Rubber House had done with the visuals, following advice given by Looney Tunes director Chuck Jones, who said to never mix music and sound FX. “However, these weren’t fully-fledged cinematic shorts, so our aim was to simulate the score that a 1950’s Public Service Announcement produced on a middling budget could afford,” adds Sharp.

Outside of these necessary limitations, where Rubber House clearly had some fun was in introducing another rule for each of the seven shorts: there had to be at least one violent Vault Boy death per episode. It’s a bit of a throwback to a time when cartoons could be a little more violent and get away with it, slapstick having pervaded early 20th century animation. Though, not many (if any) quite achieved the gore levels in the visual gags of the S.P.E.C.I.A.L. animations.

You can read the full interview with Rubber House over on Motionographer.

The rocky path to widespread internet access in India

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

If you’re reading this, you probably have internet. In fact, you may rely on the internet for a significant portion of the day. You may wake up in the morning and check the weather on your phone, or use your laptop to type out a message to your boss or coworker. You’re one of the lucky 43 percent. In India, you’re one of the 29 percent.

Facebook launched Internet.org in India alongside Indian mobile company Reliance Communications in early April, hoping to discover an efficient way to provide free internet access to that 81 percent previously without it through the use of a mobile app. “Last year I visited Chandauli, a small village in northern India that had just been connected to the internet,” wrote Mark Zuckerberg on Facebook in April. “In a classroom in the village, I had the chance to talk to a group of students who were learning to use the internet. It was an incredible experience to think that right there in that room might be a student with a big idea that could change the world—and now they could actually make that happen through the internet.”

Global connectivity is not a new concept or an easy goal to achieve

However, the initiative hasn’t been without its bumps and halts. Critics admonished the initiative for only offering a sliver of all the things the internet can provide (like news, weather, government info, and job listings). In response, it has recently rebranded its app as “Free Basics by Facebook,” and is offering more services than the previous Internet.org app offered.

Global connectivity is not a new concept or an easy goal to achieve. Organizations like the United Nations and Internet Society have already been showing less developed countries the benefits of internet access, building infrastructure and teaching others how to build and maintain that infrastructure. In fact, the Internet Society has been striving to perfect global access for 25 years, and there are many steps involved to getting to that point. “[The Internet Society is] super supportive of anything that can push the margin, but the hard underlying fact is that you have to follow certain rules,” says Jane Coffin, director at the Internet Society. “We kind of think that everywhere is like we are. I was sitting in one country and couldn’t upload anything onto Facebook. What are governments doing to actually remove barriers to connectivity?”

Wifi is transmitted through spectrum, or radio waves. However, spectrum is limited, and can interfere with other devices using it. “Spectrum is regulated by every country in the world,” says Coffin. “You start to unpack how difficult it is to get spectrum. In certain countries, you need a license to get spectrum and sometimes it can take more than a year.” Facebook has attempted to develop ways to transmit spectrum through the use of satellites in low-density areas and, in medium-density areas, low-flying solar-powered drones.

In the past, organizations like the Internet Society have taught people within less developed communities how to manufacture, assemble, and operate technology. By teaching one person, or one section of the community, Coffin says the rest of the community becomes more open to the internet through the use of a human trust network. “Think about it from a videogame perspective,” says Coffin. “There’s a huge gaming community in Uganda. The gamers were bummed out because they couldn’t play as fast. There was a way to make the connectivity faster by building up the local internet infrastructure. They talked to each other and figured out a way to communicate what they needed. In that way, they built up a human trust network.”

the trust placed in Facebook is missing

However, the trust placed in Facebook is missing, especially as Facebook sets up its connectivity from the corporate level, rather than from the community level. Some sites have claimed Facebook is surveilling the people using Free Basics and using them to their marketing benefit, as well as stripping them of their anonymity.

While the need for a globally accessible internet has been highlighted and more awareness has developed surrounding it from initiatives like Internet.org, there’s still work to be done in creating something accessible and it may not happen for many years to come. Nonetheless, the work and effort put into global accessibility is invaluable. “The internet allows you a visuality to do something,” says Coffin. “With the internet, we brought in an amazing transformation in innovation happened.”

January 4, 2016

Celebrate Swiss architect Le Corbusier by defacing one of his masterpieces

What better way to celebrate it being 50 years since influential Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s death than redesigning his famous Villa Savoye? Oh, not actually, of course. We couldn’t possibly bear to spoil what is considered by many to be one of the keystones of modern architecture (and also an official French historical monument). We’re talking videogames here. Yes, it’s their easily-reset worlds that allow us to enjoy reckless fantasies without consequence (usually), so why not employ them to deface a prestigious villa that sits on the edge of Paris?

This is the concept of a new project by Greek-born Theo Triantafyllidis, who is currently a student in UCLA’s Design Media Arts program, and creator of the dating app parody Pin-Pon, which we previously covered. He was commissioned by the #decorbuziers exhibition that took place in December 2015 in Romantso, Athens, to produce a videogame that, in some manner, paid tribute to the late architect. What Triantafyllidis came up with is called Le Petit Architecte.

Put too much clutter down and the game will start to break

Much like Pin-Pon before it, Le Petit Architecte embraces chaos, glitches, and silliness. It places you as a young, inexperienced intern who is destined for greatness as they will one day “create the absolute architectural masterpiece.” Hmm. Perhaps you can help along with that. Jumping into this intern’s perspective, the game gives you the ability to throw (yes, literally) architectural pieces in front of you. This intern is clearly quite strong in the arm considering they’re capable of throwing iron ladders, doric pillars, and entire arches made of stone at a reliable and handy height and distance.

But that is not this intern’s only feat. It seems that they have also found a way for all of these hefty building pieces to stick together upon contact. The architect’s arch-enemy is gravity, but not this one: with them, you build a higgledy-piggledy tower of supreme balance and strength. It’s best built Minecraft-style. That is, standing atop the highest point of the tower, and then spamming the jump and build keys so that you steadily arise, and the tower with you.

The finished sight would render not only the best architect’s in the world speechless but its variety of bright colors would also hold every single toddler spellbound. There are blues, yellows, greens, reds; a tootie-frootie lollipop of a tower. Not only that, but the tower’s materials aren’t even sensible. Along with the bits of wall, arches, and pillars, there are also doors, cats, pianos, lamp posts, and slides. Wonderfully, each individual piece makes a sound relative to the object when thrown: cats meow, pianos crash discordantly, and so on.

Given the absurdity of it all, what Le Petit Architecte may end up bringing out in you is not an interest in creating the tallest tower possible, but as much of a mess as you can. The entire voidscape within which sits the Villa Savoye at its center can be filled with a mass of architectural bodies, careful design be damned. Put too much clutter down and the game will start to break, with objects desperately vibrating in empty space, unable to find purchase, and eventually, a whole tornado of over-sized toys can be sent juddering around you. Le Corbusier wouldn’t have approved of such destruction but he would have most likely marveled at the sight of it all.

You can download Le Petit Architecte for free for Windows and Mac over on itch.io.

Finding new respect for Battletoads’ classic soundtrack

Battletoads was released in 1991 as an effort to rival the success of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The game features three humanoid toads named Rash, Zitz, and Pimple and—while they do share some aesthetic similarities with their amphibian contemporaries—the series couldn’t be more different. Battletoads is an exceedingly punishing game and is often praised (and sometimes criticized) for its extreme difficulty. Where most beat ‘em ups throw wave after wave of low-powered adversaries at the player, Battletoads features obstacles and enemies that only increase in strength, frequency, and ruthlessness.

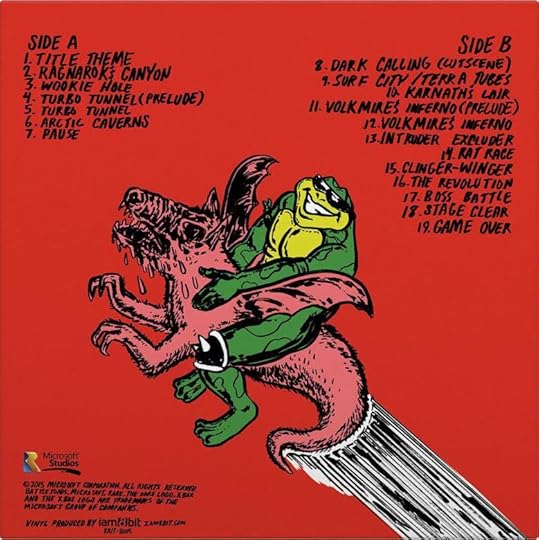

But, as a game remembered for its cruelty, Battletoads is often overlooked for having one of the most sophisticated soundtracks of its time. The compositions work so well, in fact, that the soundtrack was recently released as a full LP by the L.A.-based creative collective known as iam8bit.

As a physical object, iam8bit’s release is an absolute masterwork. The record is presented in a double gatefold sleeve with original artwork from Nick Gazin (best known for his recent work for Run the Jewels) and pressed on high-quality 180 gram vinyl. Vinyl nerds relish 180 gram prints: heavier than the standard 120 or 140 gram releases, it promises superior balancing, scratch resistance, and overall stability. In other words: it’s really thick.

Battletoads has one of the most sophisticated soundtracks of its time

Each record is custom-pressed with a special mix of green and yellow wax, a color that’s been artfully dubbed “toad skin.” It’s beautiful and messy and, when spun on a turntable, absolutely mesmerizing. It’s the perfect avatar for a game that features mutant toads dismembering robots and curb-stomping space rats.

The soundtrack—remastered specifically for this release—was composed by David Wise. His credits include Star Fox Adventures, Diddy Kong Racing, and the upcoming Yooka-Laylee, though he is best known for his work on Donkey Kong Country.

His compositions are notably atmospheric, a style derived from mixing sound effects from his games with melodic and heavily percussive accompaniment. A good example in the Battletoads soundtrack is the “thwomp thwomp thwomp” of “Pause,” a track cleverly placed at the end of side A. The beat that carries the song is made from the punching sound effect used in the game. It’s heavy and fierce and surprisingly thoughtful for something meant to play during bathroom breaks.

That’s part of what makes the Battletoads soundtrack so enjoyable to listen to. Every note is specific, every sound intentional; every track does as much to create a narrative landscape as the design of the levels they accompany. Consider “Ragnarok Canyon,” the second track on the record and the song for Battletoads‘ first level. It opens with a heavy beat and is soon overwhelmed by a speedy melody. There are several layers of deft percussion, each a sample of combat sound effects. There’s also this elongated synth that’s dragged over each chorus. It gives the level a pseudo-scientific, Mystery Science Theater vibe. It also mimics the noise made in game when long-legged robots manifest near the middle of the level.

Side B is filled with tracks that increase in complexity and pace, making it my favorite half of the album. The first track is the music that originally played during Battletoads’ cutscenes, rightly titled “Dark Calling.” The beat is a bit slower, a bit steadier, and it’s overlaid with a menacing synth that taps out in a high, confident pitch. It feels perfectly menacing, perfectly dark, with a richness built on layers of deep percussion. It’s short and sweet and a fantastic introduction to the last half of the recording, representative of the game’s final—and most excruciating—levels.

The last two tracks are the seven-second “Stage Clear” and 60-second “Game Over.” It’s a clever order and a testament to iam8bit’s dedication to impressive detail work. The record ends with a short reprieve, the rare sound of having actually beaten a level of Battletoads, only to be followed by the more obvious “Game Over.” When you play Battletoads you’re going to die over and over again, and the “Game Over” sequence is one you will hear multiple times.

Every track creates as much of a narrative landscape as the design of the levels they accompany

Ending the soundtrack with “Game Over” is a purposeful nod to the punishing gameplay that made Battletoads a classic. It’s a tribute to the shadow of foreboding that is cast through every inch of the game. From the pressing, to the track listing, to the tender care given to Wise’s original recordings, this record demands respect.

And for me, that’s what makes this release so exciting. The Battletoads soundtrack is a legitimate artistic effort composed by a legitimate musician and it deserves to be taken seriously. This release does more than give listeners a nostalgic kick; it gives the Battletoads soundtrack the opportunity to exist on its own. It doesn’t matter if you’ve played the game, or that this pressing is a collector’s item, what’s important is that the music is presented as a complete and treasured work.

Special thanks to iam8bit, who provided the high resolution artwork that accompanies this article.

A VR exhibit journeys into the hidden souls of libraries

Libraries, huh, yeah. What are they good for? With apologies to Edwin Starr and Betteridge’s Law, the answer to that question is probably not “absolutely nothing, uh-huh uh-huh.” That’s a start, but it still leaves the not insignificant question of what, exactly, a library is good for in this day and age?

As I waited in the bowels of the Grande Bibliothèque in Montreal for a showing of The Library at Night in mid-December, I found myself thinking of this question. The show, which is a collaboration between writer Alberto Manguel and artist Robert Lepage’s production company, Ex Machina, centres on 10 three-minute virtual reality films about famous libraries, from Alexandria, Egypt, to Mexico City, by way of the vessel in Jules Vernes’ Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. As with Manguel’s book of the same title, the exhibit suggests that libraries only reveal their true selves outside of peak hours. To that end, its constituent films do not function as user guides. Rather, they each place the viewer in the center of a library and invite her to look around as Manguel narrates the scene.

The Library at Night is not, however, solely composed of VR films. The experience begins in an anteroom, modeled after Manguel’s barn. The space first appears to be a museum exhibit, but it comes to life as the author’s pre-recorded voiceover explains the room’s collection and importance. As Manguel speaks, books, portraits, and windows light up to emphasize his points. The audience mills about the anteroom, experiencing subtly different versions of the same environment even before they have donned their VR headsets.

That happens in a second room. With double-height ceilings, it accommodates artificial trees whose trunks turn to sheaves of paper as they intersect with the floor. Those papers later rustle underfoot as audience members spin around in their wooden chairs. In the final moments before donning headgear, one notices that the chairs are positioned in front of library tables that are topped by green banker’s lamps. This, too, is an alternate reality library, albeit one with a physical presence. The Library at Night takes an expansive view of immersion, suggesting that VR alone cannot produce such engrossing results.

Once one accepts that the experience of a VR film is not wholly contained within the headset, it becomes hard to know where that experience actually begins. The Library at Night encourages a form of criticism more associated with architecture than film, the promenade architecturale. At the very minimum, The Library at Night really begins in the Grande Bibliothèque’s lobby, where the library and archive’s regular patrons come and go, and newly-returned books are shuttled away on conveyor belts. The experience continues past the café where students are studying and down the steps to the basement. There, a sign about the health risks of VR—“Wearing the Gear VR headset may have harmful effects on pregnant women and people with a known medical condition (visual or neuropsychological disorders, cardiovascular disease, etc.)”—greets potential audience members. This is not an introduction to VR for tech geeks and insiders; it is the sort of cautious greeting offered by an institution that once introduced much of the population to personal computing and the Internet. Thus, to the extent that The Library at Night is about libraries in general, it is also specifically about the library in which it is on display.

But what of the actual films?

Fine. They’re fine. Ex Machina’s approach to VR is accessible but fundamentally uninspiring. Their films avoid VR sickness by employing a still camera that floats in the centre of each library. You can look around as little or as much as you wish. Look down and you’ll see the floor. No feet are visible. You are just a data point floating in space. This approach to filmmaking is weightless. It is also largely opinionless. One of the central challenges of VR filmmaking is that the audience’s ability to look around curtails the director’s ability to frame a shot. This problem has yet to be solved—and may not be entirely solvable—but works like The Archer suggest that visual ingenuity can be a means to this end. The Library at Night, however, resorts to audio cues. Some of these cues, like the sound of birds chirping, are subtle and effective. Others, like the narrated command to turn around and look at a mural, are clumsy and nonsensical. What if you’re already looking in that direction, as I happened to be? Tough luck. The Library at Night can be visually inventive and its narration, when not compensating for the medium’s limitations, is engaging, but Ex Machina’s use of VR just isn’t up to the task.

Lepage and Manguel’s show can be understood as a companion piece to 2014’s Cathedrals of Culture. Spearheaded by Wim Wenders, the collection of six half-hour documentaries uses aggressive stereoscopy and narrations delivered as if walls could speak in an attempt to understand the innermost feelings of famous buildings. This approach to 3D filmmaking distorts the relationship between foreground and background, emphasizing details at the expense of context. Cathedrals of Culture, for all of its failings, succeeds in transmitting a clear visual idea of what should be held dear in each of its six buildings. (The remarkably asinine narration offers little competition in this regard.) The Library at Night is also interested in the soul of buildings and also uses a combination of technological advances and narration to get its points across, but does so to completely opposite effect. Whereas Cathedrals of Culture offers no shortage of opinionated visuals and little else, The Library at Night leaves you wishing that Manguel’s words and Lepage’s visual wit could be complimented by Wender’s aggressive framing. Both works are inventive disappointments that suggest that their central concepts, once fully realized, will make for a good film. That film does not yet exist.

One exits The Library at Night much as one came in: past the library tables and artificial trees, past the warning sign, up the stairs, past the café where students are still studying, through the atrium, and past the book return machine. It’s one last library tour after the ten or eleven in the exhibition space. Of all the tours The Library at Night orchestrates, this one is the most compelling. It is a reminder that the library has historically served to diffuse cultural and technological innovations, from books to personal computers to virtual reality. Ex Machina’s approach to VR is too mild to be memorable, but it is a safe introduction to the medium. You can go to The Library at Night with your parents and not worry too much about the possibility of their throwing up. That’s what I did, and no nausea ensued. (I have also been asked to point out that my parents purchased the tickets and brought me along.)

Portrait of the author’s mother, an expert in the field of motion sickness, watching a VR film with no adverse effects

Portrait of the author’s mother, an expert in the field of motion sickness, watching a VR film with no adverse effectsCompared to specialist meetups, The Library at Night takes a democratic approach to promoting the medium of virtual reality. In this case, the underutilization of VR’s capabilities is the cost of accessibility. For now, that may well be an acceptable trade-off. It is not obvious that the more in-your-face approach employed by VR filmmakers is always preferable. Aggressively experimental works have an important role in advancing the medium, but they may not be the best way to spread it. The New York Times’ VR app, for instance, offers a more plausible route to widespread adoption, and The Library at Night is more closely aligned with NYT VR’s vision. Embedded in the experience of attending The Library at Night, then, is the sort of political and cultural calculus one can expect from a library.

Therein lies the beauty of the procession out of The Library at Night. VR to a café-cum-study space to books: It’s the modern library encapsulated in one short sequence and the sort of clear framing that is otherwise lacking from the whole affair. The Library at Night, by dint of its existence makes a good case for what a library can offer as a civic institution in 2016, it just doesn’t do it through its filmmaking.

The glorious return of The X-Files, TV’s greatest science show

There was one point in my life where I thought about becoming a member of the FBI. In the months prior to my graduation from college, I had decided that I could put the 200+ hours that I had invested into The X-Files to good use. Of course, after I learned of the trials and tribulations one had to go through to get there (like a fitness test, and the ability to overcome the fear of being near a gun), my weak noodle arms and I dropped the idea. I also played with the idea of becoming a Ufologist for a few days, but had a very hard time figuring out how I would make enough money doing that to sustain living, aside from working for the History Channel. I eventually settled into a PR job working in a cubicle with an “I Want to Believe” mousepad.

It doesn’t amaze me how much of an impact a television show has on me; I fairly easily envelop the things I love and integrate them into a part of my daily life. I related well to Mulder’s blind determination and obsessive personality, and Scully was a grounding role-model for me, who would stand up for herself in the face of any man or monster. What does amaze me is just how many people the show actually had an impact on; for example, the phrase “shipping” is residue from early ’90s message boards dedicated to Mulder and Scully’s relationship. The show’s relaunch has given cause for many such reevaluations, and one of the people on that relaunch is Anne Simon, who serves as the show’s science experts as well as a Biology professor at University of Maryland.

“[The X-Files] really had an impact on science,” she told me recently. “It portrays science in a positive light. Scully was portrayed as a real scientist. She was caring and human. I asked one of my biology classes, ‘How many of you went into the field because of The X-Files?’ and half of the hands in the class went up.”

Because of the show’s impact on me, I was initially ecstatic when they announced the mini-series due out in January. This was immediately followed by trepidation from what seemed like me and every X-Files fan on Tumblr. What if they fuck up? They’ve broken up Mulder and Scully, what’s not to say that they’ll break the entire show?

But I’m confident, after giving it some more thought, that everything will be fine. This is because the science is there.

It portrays science in a positive light

When trying to figure out the real MVP of The X-Files, everything needs to be taken into account: the relationship between Mulder and Scully, the agents (including Doggett and Reyes, who are greatly underappreciated), the aliens, CSM, the Lone Gunmen, etc. For a while, I thought it was Scully. It’s not. After spending months trudging through the abominations that are season eight and season nine, with Scully’s 13-month pregnancy and sudden belief in aliens, and Mulder’s vague brain illness (and total disappearance), I realized the thing I really missed the most was not, to my surprise, David Duchovny, but the strong science foundation that the show had always weirdly maintained. It somehow made every episode more believable, even when bees are carrying government-manufactured alien diseases seemingly designed specifically to ruin any chance that pre-season seven Scully and Mulder had at romance.

If you don’t believe me, take a moment to reflect on the rightly acclaimed episode “Post-Modern Prometheus.” The episode follows Mulder and Scully investigating a mysterious pregnancy, after a woman is attacked by her child’s “comic book creation,” The Great Mutato. Apparently, X-Files showrunner Chris Carter wrote it while on a Cher kick because it features a couple of her songs and the 1985 film Mask (as someone who experienced a Cher kick at the age of eight, I was wickedly obsessed with this episode). We love it because of the shipping fuel—Scully and Mulder dance together to “Walking in Memphis”—and because Cher is actually the only reason most of us carry on with our day-to-day lives, sure, but maybe there’s a subtle reason behind the love, too. The entire time you’re enjoying this weird Frankenstein riff, Simon’s scientific ideas are whirring away in the background, making the whole thing seem plausible.

“‘Post-Modern Prometheus’ was the first episode where Chris (Carter) based the script off of one of my ideas,” said Simon. “It’s become one of my favourite episodes. I was even asked to live-tweet it for the X-Files countdown on Fox.”

The scientific explanations interwoven throughout the show are what make monsters like the Flukeman and plotlines like the government-distributed diseases so memorable. I mean, Mulder would be unrelatable if there was no scientific basis to any of his claims; people who spew conspiracies with no basis in reality are often pretty easy to disregard. That’s why it’s important for Mulder to have Scully, a scientist and a medical doctor, and a background in psychology: these practices help describe unscientific events and beings. The new miniseries looks to continue to honor science. Simon is even credited as a writer in one of the new episodes.

The new miniseries looks to continue to honor science

“I don’t write for the show, I give the ideas. I’ve put more into the new season than previously before,” said Simon. “I had a really good idea and Chris incorporated it into the central plot of this mini-series. For this new episode, episode six, I came up with the background for the entire episode.” Not giving too much away about the episodes, Simon also said Scully would be a focal point of two episodes.

While it’s devastating that Mulder and Scully are separated and have found different partners and moved away from each other, I don’t think we have a lot to worry about. The most important things will all be there: Scully, Mulder, The Lone Gunmen, Reyes, Skinner and the scientific narrative that pulls all of the characters together and makes every adventure believe. And anyway, nothing The X-Files ever produces will be as bad as its terrible PlayStation 2 game Resist or Serve. At least we’re all safe from that now.

Max Ernst’s surreal forest paintings get a videogame tribute

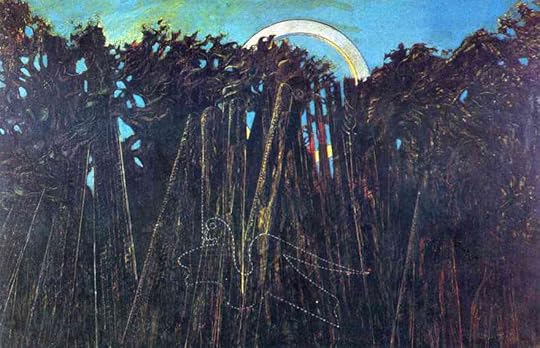

Textures in games are hardly ever painterly. There are clear cut examples of games trying to emulate the look of a painting (like Okami’s cel-shaded, oil painting art style), while others are literally hand painted (like Double Fine’s Broken Age)—but to find a genuine surreal art style implemented into a game would be much harder to pinpoint. In Saint Petersburg-based digital artist Yuliya Kozhemyako’s latest project La forêt, Kozhemyako seeks to emulate the surreal paintings of German artist Max Ernst.

Ernst was a pioneer of surreal art, helping to formulate the obscure Dada avant-garde movement in Berlin and Cologne. Among his notable works are his forest paintings, redundant in texture and haunting in their complexities, the very same paintings that inspired Kozhemyako’s digital project. The project itself is an exploration game of sorts: you pace forward in silence, a white circle illuminating the dark space, abstract textures growing out of the ground. They are trees, but, hardly look the part.

a similar panic and confusion surrounds them.

As the trees grow taller and taller, crossing one another and obscuring your view of the pale white flat circle in the sky, an ambient sound grows more and more distorted, once silent, now fully encasing you.

In Ernst’s paintings, a similar panic and confusion surrounds them. Textures are repeated across the works, from the early forests of 1925 to the later, more detailed, paintings in 1933. All with forests, all surreal looking, all with rounded, empty moons looming overhead. Kozhemyako’s project embodies these visual motifs, and implements them in a fresh way, using the blurred motion of walking around the space, the sight of seeing the towering textures grow above you, and the unsettling ambient sound that soon encompasses you entirely as a means of transporting you into one of Ernst’s paintings. The experience is completely surreal, and Kozhemyako’s homage wouldn’t have it any other way.

Experience La forêt for yourself for free via itch.io .

///

Photo of Max Ernst’s “The Embalmed Forest” from Wiki Art .

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers