Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 176

January 11, 2016

Breath of Light breathes new life into Australia’s game-making scene

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

In 2011, curious creatures took over the music festival “Splendour in the Grass” in Woodfordia, Queensland. Jimmy McGilchrist designed “Curious Creatures” as an interactive exhibit for the public; silhouettes of strange animals were displayed on a large screen, as if fenced in on the other side. Attendees could approach and engage with them: Stick your hand out and the animal would dip its snout toward you; get too close and the large chicken-like thing might cackle and flutter away. By the end, the question of which creatures are meant to be the curious ones is up for debate.

Matt Ditton’s Melbourne-based game studio, Many Monkeys, developed the technology for McGilchrist’s project, which would go on to festivals in South Africa and Austin, Texas. Born in Brisbane, he worked in the games industry for over a decade on franchises such as Krome Studio’s Ty the Tasmanian Tiger and Pandemic’s Destroy All Humans! before moving south and starting up his own company.

“I came down [to Melbourne] specifically to try the one thing I hadn’t done,” Ditton tells me. “I’ve been an artist, a technical artist, a programmer and a producer… maybe I could just run a company. Maybe we could just get a bunch of people in the room together and make stuff.”

That room is located in what’s called The Arcade: A consortium of game developers working both independently and together on various projects. A growing number of PC, console, and mobile games are being brewed here, a former warehouse now home to dozens of offices working in synchronicity. Mighty Games’ first effort is called Shooty Skies; the mobile shoot-’em-up that came out last year, features geometric animal-pilots shooting down robots across an isometric landscape. Mighty Games works out of the same room as Many Monkeys; in fact, Shooty Skies is a combined effort between Ditton, Ben Britten, and Hipster Whale, the team behind Crossy Road and Pac-Man 256. I mention another game getting good buzz out of Australia, the PC and PS4 strategy game Armello by League of Geeks. “They work upstairs,” Ditton tells me.

“The Australian development scene works really well because we are so close-knit,” Ditton says. “Geographically we are incredibly isolated. It’s a long way to get anywhere. And we share so many resources because we’re the best resources that are easy to find.”

Such collaboration has risen out of a great trauma, Ditton shares. Not too long ago, there was almost no Australian development scene at all.

A RELAXING, ZEN-LIKE EXPERIENCE

“In 2009, the world ended,” Ditton says, explaining how with the global economic crisis, large developers in Australia shut their doors in record numbers. There wasn’t the market for smaller, independent games as there is now; most developers worked as contractors on major projects for large publishers. When that went away, there was almost nothing left.

“In the space of nine months, every studio closes,” Ditton remembers. “What now?” Without a steady job, Ditton taught at the Griffith University in Queensland while working on side projects. In 2011, he finally moved south to Melbourne and decided to begin again, using his talents for interactive art installations before moving back into commercial development with his first independent mobile game, Breath of Light.

Light is a relaxing, Zen-like experience; you direct stones and rocks around a spare, colorful garden in order to shift a flowing energy over flowers waiting to bloom. It’s lovely and low-key; the pace and atmosphere demand headphones and a comfy chair.

But its original incarnation, titled Feng Shui Master, was more aggressive and combative, moving furniture around a house to perfect the titular aura. “It was an interesting game,” Ditton says of the first build, “but the joke was stupid.”

Australian game studios are anything but a joke these days, with success stories like Halfbrick’s Fruit Ninja and Jetpack Joyride coming out of Brisbane, while Loveshack’s Framed and Alexander Bruce’s Antichamber were both made in Ditton’s newfound home, Melbourne. Predictably, Ditton tells me that Joshua Boggs of Loveshack is a friend. He doesn’t say if they exchanged notes. But it wouldn’t be surprising.

“I feel incredibly thankful to be working in the games industry now,” Ditton says. “Right now is the best the Australian industry has ever been. It’s also probably the most difficult. Everything’s kind of hanging together. People are looking after each other. But at the same time it’s really stressful.” With more independence comes greater freedom, but greater risk. You can’t hide behind a giant corporation; as a smaller developer, your game is a direct extension of yourself. And your friends.

“You’re putting yourself out there on this world stage. And there’s no safety net; all we have is each other to make it all work.”

Suits: A Business RPG asks how easily you’ll give in to a corporation

The enemy here is capitalism. Isn’t it always?

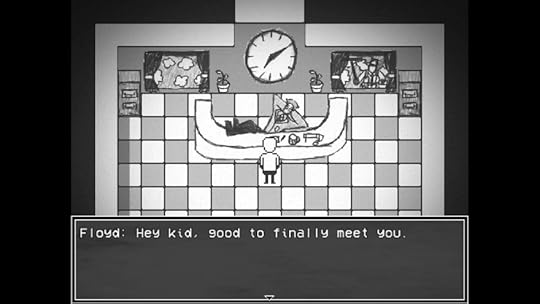

Suits: A Business RPG is an expedition into the morass that is modern capitalism. Note that it is not a journey through this world. That would presuppose the existence of an escape, and Suits is not that sort of game. The action takes place in a black-and-white corporate dystopia, though the extent to which this world differs from ours is very much up for debate. “Corporations,” the game’s documentation explains, “control the entire global government.” What’s new?

You play as a businessman. You are not the worst of people, but you’re also not particularly virtuous. You’re just another cog in the machine. The Corporation and its representatives give you tasks to complete. Remember: your corporate overlords value your silence and acquiescence. Do exactly as they say and there’s money in it for you. What else could you want? But let’s say you want more. Well, it’s there for the taking. Not legally, sure, but it’s there. Wealth is all around you, so why not take some? Suits bills itself as “the journey of a businessman’s descent into corruption,” which is not a particularly optimistic view of human nature but a reasonable one nonetheless.

This is a structurally and linguistically corporate world.

Insofar as this gloomy disposition extends to political and economic systems, Suits attempts to make its point through language. This is a structurally and linguistically corporate world. The former isn’t really that big of a change, but it is relentlessly underlined through corporate language. The world, the government, and power itself all take their name from the corporation or, to be precise, The Corporation. This critique of capitalism depends on the viewer already believing that corporations are unpleasant. It’s only slightly subtler than Mr Robot’s “Evil Corp.”

These critiques work because corporations have not exactly covered themselves in glory over the past few decades. The weakness of capitalization as rhetorical strategy—just call it The Corporation—is that it preaches to the choir. If you believe that corporations are somewhat sinister, these works will resonate. But what if you’re on the fence? Suits and, to a lesser extent, Mr Robot don’t really develop a language to criticize the worlds they depict, and the broader concern is that the culture as a whole is failing to do that. These are still valuable and interesting works of social criticism, but their value is limited by their indifference to those who most need persuading.

John Carpenter’s The Thing refuses to change shape

The Thing is one of the most peculiar media series to try and wrap your head around. For starters, as far as series go, it struggles to qualify, mostly orbiting John Carpenter’s 1982 film, with a small and loose assemblage of multimedia offshoots (a comic series, a prequel film) dancing at the edges of its gravity. You could argue that the series itself resembles its titular namesake: an amorphous entity that devours and impersonates the characteristics of its predecessor; each incarnation a diminishing return of success.

Part of the difficulty in capitalizing on The Thing’s clout through serialization is the film’s singular premise. It takes place at a secluded Antarctic research post infiltrated by a dangerous extraterrestrial being. In other words, The Thing champions isolation; set in a location that is perpetually hostile to human life, a group of hapless scientists desperately lash at one another to save the world from the monster that prowls within their midst. It’s an extraordinary film made all the moreso for the particularity of its setting and the frightening intimacy of its circumstances. These attributes render the task of adapting or expanding on the premise of the original film daunting through other mediums, let alone within the shared space of film. So how does one adapt John Carpenter’s The Thing, a film that defies adaptation, into a videogame?

Announced on September 21st, 2000, little less than a month before formal development of the game would begin, Computer Artwork’s incarnation of The Thing was touted as one of presumably many potential forays into Universal’s back catalogue of intellectual properties to adapt into successful videogames. The game takes place in the immediate wake of the film’s events, following two U.S. Special Forces units as they investigate the wreckage of the U.S. and Norwegian bases in Antarctica. You play as Captain J.F. Blake, a dyed-in-the-denim dudebro perpetually nonplussed by the harrowing events of this mission as they unfold. Whether that be being assaulted by a host of skittering human-faced flesh spiders, or the bald-faced revelation of extraterrestrial life, Blake remains stoic.

The game opens with an aerial pan over the derelict remains of the U.S. outpost, underscored by the terse notes of Ennio Morricone’s iconic theme. After being ushered inside by the threat of hypothermia, a cutscene introduces you to the faces of your three starting squadmates, each with their own snappy can-do declaration of purpose. A tutorial prompt takes special pains to assure you that these squad members are “very much alive.” They blink. They fidget. They beg for ammunition. None of their names are spoken.

ALL OF THEIR LIVES ARE FORFEIT.

This strikes at the heart of the inadequacies behind The Thing’s fear/trust mechanic, a squad management system intended to act as a mirror to the film’s emphasis on interpersonal relationships. In Carpenter’s film, Macready, Childs and the rest of the outpost personnel had already cohabitated for several months before the creature’s arrival. The dissolving of their trust and concern for one another is the result of pent-up animosity being brought to the surface in the name of survival. Humanity’s primal distrust of itself in the face of extraordinary duress. But in Computer Artwork’s The Thing, I have no idea what the medic feels about the pointman. I can’t tell if the technician truly believes Blake when he says he’s not infected. And Blake himself is a cipher, his stony exterior absent of meaningful expression. This problem is only exacerbated as the story goes on. My squadmates progressively feel less like my compatriots and more a rotating cast of liabilities, their placid expressions all bobbing in unison, hungrily sapping at the limits of my resources. Perhaps, in some twisted, inadvertent way, there is a genius behind the shortcomings of this mechanic. If I was meant to suspect and resent my cohorts, as Macready and his team so passionately resented one another, wasn’t that result effected, regardless in what way it was achieved? Perhaps my exasperation was the calculated effect of a faulty system. My disdain for these carbon-copy caricatures however serves no justice in recreating the film’s meticulous dismantlement of social hierarchy in the service of terror.

Something sad occurred to me shortly after I defeated one of the game’s larger, more difficult adversaries by circle-strafing, taunting and trapping it in a ring of fire. And that was the salient realization that this game, to put it frankly, just wasn’t scary. The Thing’s ability to infiltrate the strata of the outpost’s physical and social structure was shuttered in favor of monster closets and gallery ghouls. It had abandoned all pretense of coercion, manipulation, and assimilation in the fires that claimed its last ticket to civilization. Now all it wanted was to kill, and the game is all the poorer for that choice. The telegraphed instances where the members of my squad are outed as carriers of the Thing’s parasitic presence feel like a core mechanic relegated to an tiresome afterthought. Where once the creature’s macabre transformations served the purpose of punctuating a prolonged stretch of tension and unease, now they only serve to further underscore the expendability of my teammates. On top of that, the story unfortunately strays from the potent concision of the film’s premise and instead falls on the trope of a conniving corporation hell bent on immortality and a dastardly commanding officer, predictably culminating in your decorated team of stock dudebros pitted against another faction of paramilitary dudebros with the occasional scripted monster encounter sprinkled between.

It is within reason to suggest that the failure of 2002’s The Thing to meaningfully build off of the template of its source material is as much owed to the technical limitations of the time, as they are to the game’s direction. Aside from its role as a continuation of the film, The Thing’s moment-to-moment experiences are typical of that of an otherwise adequate if flawed early-aught third-person shooter, shouldering the likes of Freedom Fighters or Psi-Ops: The Mindgate Conspiracy. The question however persists: If this constitutes a failure, how does one adapt The Thing successfully? One possible approach in capturing The Thing’s signature blend of horror in an interactive medium is perhaps not through slavish adaptation but spiritual emulation.

The Half-Life 2 mod Black Snow, from 2012, is a sterling example of this. You are John Matsuda, an IT technician tasked with a repair team to investigate a mysteriously radio silent installation known as the Amaluuk research station. Things quickly take a turn for worse when your team is massacred by a mysterious presence on arrival and you, wounded, weaponless and alone, are left to fend off the elements and find safe passage back to civilization.

THE THING’S SIGNATURE BLEND OF HORROR

The game is an unabashed homage to Carpenter’s opus; recreating such familiar scenarios as a desecrated dog kennel and a subterranean excavation site while managing to interweave its own intriguing mystery. What it lacks in a character study of the disintegration of untrustworthy relationships it compensates with an unwavering tone of ambiguity. The game offers only a piecemeal explanation as to what the malicious presence that stalks you through the corridors of Amaluuk might be. A presence that, at the risk of over-explanation, is less phantasmagorical body-horror and more Vashta Nerada, the microscopic horrors of Doctor Who.

Carpenter’s original film is tantalizingly bookended by ambiguity. The human inclination to dispel mystery is compulsive, a preoccupation with which is, perhaps, why we make sequels and adaptations in the first place. Explanation is too often confused for resolution; the catharsis of doubt for the conclusion of conflict. But to abide a mystery is to suffer it, to solve one is to destroy it. And so too is a crucial part of The Thing’s enduring appeal stripped away in the attempt to place it as the mid-point in a larger continuity. Black Snow, too, exists on its own; its conclusion offering only a modest understanding of what transpired before our arrival. The mystery, and therein the horror, persists long after our departure.

But perhaps more impressive than Black Snow’s ability to coax the player’s curiosity from out of their comfort zones is its discerning sound design. Many of its primary assets, including sounds, are lifted from Half-Life 2: Episode 2’s pre-existing library. As such, there are the familiar Valve-authored bleeps and bloops, the synthesized death-rattle of a combine soldier co-opted to accompany the hallucinatory static flashes that seize across the player’s line of sight from time to time. But it’s most interesting in its quiet moments. The game relishes these pregnant pauses: the errant flicker of a faulty light installation, the ambient hum of the station’s power system, and the howling snowstorm that rages outside. These sounds form a blanket of ambience that offers, if not a total reprieve, then a temporary moment of calm before the inevitable scuffling pitter-patter of imminent death.

The nature of adaptation necessitates that one or more of the defining features of the original are likely to be lost in the gulf between mediums. This includes staples of the film that may be inadaptable to the medium of games, such as Carpenter’s deft camera-work that, when studied closely, masterfully insinuates a resolution to one of the film’s lingering mysteries; or the grotesque physicality of Rob Bottin’s creature effects design. It bears mentioning, however, that even Carpenter’s film itself is only the second adaptation of John W. Campbell’s short story, “Who Goes There?” Perhaps the interactive successor to Carpenter’s The Thing is not ostensibly an adaptation, but merely a game that knows how to siphon into our collective desire for solidarity, our repulsion to isolation, and our all-too-knowing fear of what waits in the dark.

January 8, 2016

Watch this guy attempt to spend 48 hours in virtual reality without sleeping

How long have you spent inside virtual reality in total—an hour? Two hours? 24 hours? It’s probably only a small number of hours as it takes quite the toll on your eyes and brain. And that’s if you don’t get the infamous nausea it brings on for a lot of people. But heck, try telling that to Thorsten Wiedemann, who is currently at the beginning of a performance called DISCONNECTED that will see him spending a total of 48 consective hours inside virtual reality. As the description says: “No human being has ever spent such a long time in computer generated Virtual Reality without sleep.”

Not only that, but the whole thing is being livestreamed on YouTube—you can tune in right here (or down below). It’s taking place at the Game Science Center Berlin and the livestream gives you a clear shot of Wiedemann scooting around on the floor (and sometimes resting on the sofas) as well as a projection of what he’s seeing through the headset on the nearby wall.

With the help of VR experience designer Sara Anna Lisa Vogl, who is updating the performance’s page and providing tech support, Wiedemann will be playing a range of virtual reality games over the next several hours. During the interim as games are exchanged he closes his eyes so as to not escape back into our reality. And if you’re wondering, yes, he has a place to relieve himself just off-camera, but he’ll still be doing so virtual reality.

According to the performance’s description, the idea of it is to give us a taste of the future, in which it is predicted there will be “VRShamans” who curate trips into virtual reality for so-called VRNauts, looking after their health and safety while they attempt to embody a prolonged digital existence. Vogl and Wiedemann are the actors in this imagined scenario brought to life for us to watch.

attempt to embody a digital existence

Oh, and by the way, Wiedemann is the founder and director of the international label A MAZE. which celebrates independent and alternative games through festivals, exhibitions, conferences, workshops, and more. It’s in attending the A MAZE. Indie Connects festival held in Wiedemann’s hometown of Berlin (and in Johannesburg, South Africa) a couple of times that I’ve met him. And having done so, getting acquainted with his flamboyant dress sense and always-on party head, finding out that he’s now throwing himself inside virtual reality for so long doesn’t surprise me all that much. It’s very him.

In fact, I don’t think I’ve seen a photo that sums his entire personality up as well as this one—check out those flip flops:

Postcard From Capri, your upcoming videogame vacation

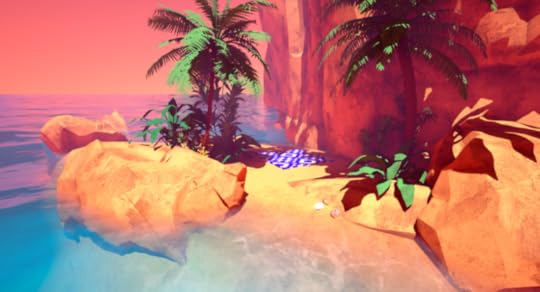

More videogames should be set in the places their creators want to go on vacation. I’m not sure if the person behind Postcard From Capri wants to travel to the Italian island of the game’s namesake but, hell, after having seen the work-in-progress screenshots, I know now that I certainly want to go there.

It’s described as an interactive short story played from the first-person perspective. So far so ordinary. OK, but you play as either a detective or a journalist (to be decided, I guess) who receives a mysterious letter that contains a postcard, a ticket, and enough money to travel to a certain Mediterranean island. There’s some kind of enigmatic plot to solve by searching for clues and speaking to the residents around the island, but that’s all that has been revealed about the narrative so far.

“it symbolizes a typical exotic place to me”

Story aside, the biggest appeal of Postcard From Capri should be the mood its creator is trying to capture. It’s this that is probably jumping out at you (and me) in the screenshots. They have several mood boards (style, city, art deco, characters) that, as one person has insightfully pointed out, show an interest in “dense informal urbanism with a Mediterranean vernacular.” What should also be noted at this point is that the game’s world isn’t supposed to be a virtual recreation of Capri, despite its title (which is subject to change). “I used Capri in the title since it symbolizes a typical exotic place to me, as well as being an inspiration,” explains the creator. Hence you shouldn’t be surprised to see architecture in the game comparative to the electric coastal houses found in the Cuban capital Havana, or the hillside box-stack labyrinthine favelas of Brazil, or even the grand art deco theaters of Paris.

Another of the big influences is the bathhouse in the Japanese animated film Spirited Away (2001). Not so much the traditional Japanese-style design of the building but its use of red, green, and dulled browns around its exterior—this can easily be seen in the color palette dominating Postcard From Capri‘s buildings. The creator adds that they’re also looking at the strange Spirit World creatures seen inside the film’s bathhouse. It can be assumed, then, that the people we’ll meet in Postcard From Capri will somewhat capture the exaggerated, slightly monstrous vibe of the bathhouse workers: bloat-headed manager Chichiyaku, witch-like owner Yubaba, and spidery multi-limbed boiler man Kamaji. Whether that presumption will have any relation to the final result is yet to be revealed.

What has been confirmed is that the island’s residents will speak a gibberish version of Italian. And so, you might say, much like the vague Mediterranean location and slightly misplaced choice of architecture, the language in Postcard From Capri is meant only to evoke the aura of a certain geography and culture, rather than explicitly pinpointing itself. It’s a dream location, a fictional city based in the designs of reality, and one that emphasizes daily living and folksy charm. Even the audio will participate in this, said to be “realistic and ambient with melodies coming from street musicians, open windows, radios”—in other words, a sizzle pot of diegetic sounds.

a sizzle pot of diegetic sounds

The lasting appeal here, at least for me, is that eclecticism. But what’s more instantly praiseworthy is how it’s all held together by that coastal sunset theme. Despite the mix of angular staircases, industrial pipe-laden rockery, and precarious red-slated villas, it’s all united under a single Mediterranean fantasy of palm trees and orange dusk. Without that it’d be a wild kitschy mess but, instead, Postcard From Capri comes across as a believably outlandish island. Better get packing your suitcases.

You can keep up with the development of Postcard From Capri on the TIGSource forums.

Everything’s (not) alright on the VR front, apparently

On the occasion of CES, the annual “consumer” electronics extravaganza in Las Vegas, murmurs started to be heard about whether virtual reality headsets were all that useful, particularly at the prices at which they are being sold. Better late than never.

CNN, however, is here to distract from the doom and gloom with an article cheerfully entitled “Google Cardboard saves baby’s life.” When you put it that way, VR sure sounds like money well spent. Granted, that title is somewhat hyperbolic. VR’s corporeal presence did not save a baby’s life all on its own. Rather, it allowed doctors at Miami’s Nicklaus Children’s Hospital to visualize a treatment to save a four-month-old’s heart. Without this visualization, doctors say they would have been forced to carry out a more dangerous procedure. They didn’t, and now everything appears to be okay. So, there: one use case.

The great irony of this use case is that it’s also VR’s cheapest implementation. As CNN so gently puts it: “A toy-like cardboard contraption that sells for less than $20 online has helped save the life of a baby who was so sick that doctors told her parents to take her home to die.”

Just imagine, then, what you could do with $599 of VR! This, by the by, is the newly-announced price for the Oculus Rift, and you should keep on imagining because the use case for this piece of kit is…not obvious? You can play games, sure, provided you also happen to be in possession of a nice gaming computer. And, well, that’s about it—at least for now. If you can save lives with the Oculus Rift, it likely won’t be at 30 times the frequency of Google’s Cardboard. Where does that leave everyone?

what’s the value of promise

In an effort to quell this existential angst, Oculus founder/developer Palmer Luckey took to Reddit last Wednesday night. In January, he explained, “we committed to the path of prioritizing quality over cost,” which explains the current price tag. “To be perfectly clear,” he added, “we don’t make money on the Rift.” Luckey added that he’d learned his lesson and would not be providing any more ballpark price figures in the future.

There are, it seems, two separate yet occasionally confounding variables when it comes to VR: price and value. On the one hand, $20 is great value for saving a life. Heck, $599 would be great value, too! And if that number priced-in all the costs of producing said innovations, everyone would presumably be pretty happy. But what is the value of a piece of kit that, for all of its advancements, does not offer a high enough resolution for such close-up viewing? More to the point, what’s the value of promise, because that is what is really being sold here?

Insofar as the answer is far from clear, determining a fair price is nigh-on impossible. You can charge what the market will pay, but when the market is paying for promise, it all gets a bit tautological. All of which is to say that it can be simultaneously true that Oculus is prioritizing quality, making no money on the Rift, and a baby is still alive because of a $20 Cardboard headset. At least one of these things is certainly good.

The world’s most complex problems, now in emoji

Step into the bustling streets of Grand Theft Auto 5’s Los Santos, or one of the many sun-dappled, monster-rich forests in The Witcher 3. These worlds are so fully realized, and at their best so compellingly true-to-life, that it’s easy to forget that all games, when stripped of the bells and whistles, are only systems operating on a specific set of rules.

But more than just games run on complex systems of interaction, and Nicky Case has made this point before. You might remember Case’s previous project Parable of the Polygons, the cute bit of interactive sociology about geometry and racism. Case developed the game with Vi Hart, adapting sociologist Thomas Schelling’s “Dynamic Models of Segregation” to demonstrate how slight biases can lead to segregation.

don’t worry: it’s all rendered in highly relatable emoji.

In Simulating The World (In Emoji), Case broadens the thesis he once expressed in Parable of the Polygons; instead of seeking to explain a specific issue like segregation, he suggests that learning to think about complex problems in systemic ways is key to understanding the forces shaping the world today. This time, he’s drawing from his own experience surviving the Mad Maxian droughts of California, and showing us how intricate systems can arise from simple rules. If any of this sounds intimidatingly intellectual, don’t worry: it’s all rendered in highly relatable emoji.

The first model in Simulating The World (In Emoji) is a forest. Add in the variable of an occasional lightning strike, and you have a simulation of the ravaging forest fire problem which has been California’s most steadfast tradition the last few decades.

As much a delight as the emoji diagrams is Case’s writing on the topic. In concise and curious terms, Simulating The World (In Emoji) talks us through the variables of invasive species and controlled burns. It might be a stretch to call Case a young Neil deGrasse Tyson, but his explanation of the feedback loops involved in his model (more trees = further spreading fires = more open space = more trees) has a similar enthusiasm and eagerness.

The title of the project is Simulating The World, though, not Simulating A Forest Fire. Using simple rules and emoji of various strains, Case goes on to simulate disease outbreaks, eruptions of conflict and a familiar parable about some racially biased rodents. He ends with an open simulator, the variables of which can be plugged in from scratch. It’s a simulation of anything you want, or anything you care about enough to make, and Case encourages everyone to muck around with it.

It’s tempting to accuse Case of actually oversimplifying problems like this, but Simulating The World (In Emoji) doesn’t set out to explain the intricacies of contagion and quarantine, or conflicts as embittered as the one between Israel and Palestine. He’s simply trying to get people to understand the cycles and patterns at the root of our most complex problems. As Case puts it, “All we gotta do is start thinking in systems, and see the forest for the trees.”

You can play Simulating The World (In Emoji) in your browser.

Behold the Berserk composer’s lost cyberpunk anthem

With last week’s announcement that the renowned, metal-as-fuck series Berserk would return later this year, it brought to mind some of the genre’s most austere compositions. “Theme of Guts”, named after Berserk’s main character, is a sedate, moving electro-vapor hymn from composer Susumu Hirasawa. Not only is it the show’s emotional cornerstone, but it holds up astoundingly well, even all these years later.

The same goes for most of Hirasawa’s stuff (the guy was a rock pioneer long before he became an anime composer), but few tracks of his are as bonkers—or frankly, as genius—as his monstrous jam “TOWN-0 PHASE-5.” This thing is filled to bursting with over-the-top anime OST tropes, like the chugging backbeat, ethereal strings, and operatic backing vocals that recall Nobuo Uematsu’s “One-Winged Angel”.

Hirasawa has some profoundly weird shit up his sleeve

But Hirasawa has some profoundly weird shit up his sleeve, too: his vocals flip-flop between immaculate and possessed as he smacks each chorus with the song’s signature modulation. Then, about three-quarters of the way into the track, Hirasawa splits the whole thing wide open with an absolute screamer of a guitar solo that wouldn’t sound at all out of place on Primal Scream’s XTRMNTR. (Listen and watch below.)

And then there’s the video, which calcifies the anime influences into a wonderfully surreal collage of sub-Reboot CG images. In all its low-budget, high-concept insanity, “TOWN-0 PHASE-5” is a lost treasure that presages today’s vaporwave low-poly revivalism, with an added touch of anime bombast that elevates it to something uncanny and sublime.

The biofeedback games made to improve our well-being

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

When Space Invaders dropped into Japanese arcades, the alien shooting gallery was such a phenomenon that the 100 yen piece, the equivalent of an American quarter, became a rarity. The games action was straightforward and exacting, and the narrative spoke to everyone’s inner xenophobe. Ultimately, however, it was the stellar soundtrack a simple pulsing heartbeat that accelerated with each passing minute that made each playthrough a thrill.

Videogames have always had the ability to affect a player’s biorhythms but now games are being created to pull those physiological reactions into the game. “I really look forward to when games are controlled at the most basic level by not only the buttons you press, but also by the way you react, by where you look and by what you say and dont say,” said Chuck McFadden, executive producer of Intel RealSense Gaming.

Imagine your entire human-self engaged in the experience.

Past attempts at biofeedback games merely toyed with the concept

McFadden has been working with Intel’s RealSense sensory input technology for years. The depth camera technology is giving game makers a way to bring a player’s body movements and heart rate into their games. Past attempts at biofeedback games merely toyed with the concept. Tetris 64 shipped with an earclip that monitored the player’s pulse, organically changing the puzzle game’s difficulty. But a new slate of contemporary games are using their players bodies not only to entertain but to help them understand and regulate their health. Now, instead of shooting for a new high score, players can aim to improve their mental, emotional, or physical well-being.

That certainly seems worth a quarter or two.

Skip a Beat

Created by a small team in the Netherlands, Skip a Beat is what would happen if Flappy Bird had been built by a cardiologist with a flair for creating geodesic illustrations. The player holds her finger over the phone’s back camera and flash so that the built-in light sensor can keep tabs on her heart rate, which then influences the on-screen action. When the player’s pulse goes up, the character, a frog flying through the sky, grows in size. This means avoiding obstacles becomes more difficult. Maintaining a steady heart rate and keeping calm adds a challenging, instructive layer to what could have been a simple endless runner.

Mindlight

Described as a neuro-feedback game, Mindlight‘s most fearsome enemy is not some fantastical monster but the player’s own anxiety. Players wear a simple headset outfitted with a single electrode that monitors the wearers brainwaves and places them in the game world. What sounds like science fiction is actually based on research from the Developmental Psychopathology department at Radboud University.

In game, the character wears a magical hat that shines a path forward through a dark and foreboding mansion. Players must navigate, moving room to room as they solve puzzles and defeat creatures. If the player grows nervous or anxious, the light will fade, obscuring the way. By combining real-time feedback based on the players actual mental state, GainPlay Studios is creating a new kind of videogame power-up: The ability to control fear responses.

Nevermind

Sometimes, people like being scared. Flying Mollusk’s Nevermind rewards the player with an increasingly surreal and horrific experience the more tense she gets while exploring a haunted house. Though playable without any biofeedback device, a slate of sensors including Intels RealSense camera are supported, offering a window into the player’s internal state. That mood is then reflected in the game world: If the player’s biorhythms are detected as too erratic, a serene kitchen bends and distorts into a flooded, static-y nightmare. To ensure the games nightmarish feel was truly frightening, the team needed to test the game over and over again. This proved challenging.

”The disturbing images and jump-scares start to lose their potency by the hundredth time you experience them,” explained McFadden, who helped during the game’s development process. “We had to come up with creative ways to manipulate our heart rates.” The final result is a game that’s wholly different from adventure games like The 7th Guest and Silent Hill that toy with horror as a reflection of the player’s skewed reality. Nevermind dissolves the barrier between fear in the game and fear out, and the results are terrifying.

Wild Divine

Videogames usually try to excite their players, with deafening explosions often acting as the reward for a job well done. Wild Divine is interested in calming those frayed nerves. More a meditation lesson than pure entertainment, Wild Divine uses the IomPE Biofeedback sensor to give the player immediate insight into her body’s reactions. One scene shows rose petals floating on water while the user is instructed to breathe in and out slowly.

More a meditation lesson than pure entertainment

Whereas standard meditation relies on the practitioner understanding whether she is doing it right, the included sensor helps answer that question. This helps players realize meditation as the developers see it: Nothing more than the practice of paying attention.

MindMasters

Biofeedback can be a novel experience for the player, but what happens if playing a game actually provides important information to a larger community, too? Rochester Institute of Technology and St. Johns College had the same idea. That’s why they collaborated on a project to build a proprietary physiological controller that would not only measure a player’s nervous system but also gather data. By answering a set of preliminary questions, each player generates her own unique avatar. Then, harnessing the fight-or-flight response, the player carefully guides the avatar through a virtual environment.

The result enhances gamers’ ability to overcome challenges at home, school and work. By studying the cumulative results of thousands of players, however, the researchers can identify better ways to treat mental health and behavioral problems in the future. The game also means players have the added incentive of playing videogames for science.

Overland envisions Edward Hopper’s America as an altogether filthier place

America as depicted in the work of the American realist painter Edward Hopper is almost unbearably quaint. The majority of his paintings and prints involve remarkably calm, perhaps lonely, people leading blissfully mundane existences in vintage diners, full service gas stations, and excessively tidy drawing rooms. It is easy on the eye, but you can’t help but despise these privileged, perfectly normal human beings who had nothing better to do with their time but sit gazing out of windows, halfway nude, at skylines and crap.

Thankfully then, Finji is introducing these quiet, placid Americans of our national heritage to the grim reality of modern America, which is full of suffering and anxiety and social awkwardness and ostensibly tough choices about who gets to eat who when the food supply runs out.

“it is good to temper the notion of the lonely genius”

Overland is the small Austin-based studio’s take on the perennial post-apocalyptic wasteland videogame, and it looks suspiciously like scenes of peacetime-era American loftiness, except served up with sweet, delicious angst. In fact, the game’s art director Heather Penn has seen fit to look towards Hopper in designing her revisions of the barren North American locations and prairie architecture. “In retrospect, the connection seems obvious,” writes lead designer Adam Saltsman in a recent Finji Friday blog post. “In so many paintings, just one or two people remain, the vastness of the great plains spread out before and behind them.” Adding to the Americana of it all, many of the symbols and icons were borrowed from the iconography of the nation’s National Parks.

So that explains the almost patriotic classicism in the art and design. But why the lone-wolfing it? What to make of Overland’s mutants and pointed sense of dread? Well, that comes from disgruntled Soviet-era sci-fi and roguelikes, of course! “I think it is good to temper the notion of the lonely genius who somehow invents everything out of thin air,” Saltsman says, before going on to dump out a shopping basket worth of videogames and other cultural artifacts that motivate the team, including the Strugatsky brothers’ terse and influential novel Roadside Picnic, and Michael Brough’s tension-filled roguelike 868-HACK.

As a result, Overland looks to be a delicious intersection point of a bunch of stuff that doesn’t really belong together but somehow fits without showing seams. It’s pretty, profane, and it’s turn-based strategy. What more could you want?

Overland is coming out later this year for Mac and PC. Find out more on its website.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers