Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 175

January 13, 2016

Blackstar won’t tell you how to die

I spent a lot of time this week listening to “Subterraneans,” the last song on 1977’s Low, by David Bowie. I didn’t know what else to do. Like a lot of other people, I had a feeling—this response to death we all have, with varying degrees of terror and/or sadness attached to it—combined with the uselessness of just being on the internet, looking for something to do. And so we (I) look for more David Bowie, or we (I) listen to more David Bowie, because all of it’s still right there, right where we (I) left it. We sort of rummage around for new eulogies, get into conversations about albums and songs, publically remember moments of connection with him, in his various guises and vocations. (There are a lot of Labyrinth fans out there, apparently.) These understandable, human impulses eventually tip into something much less savory, but no less expected: performative grieving, neatly incorporated into somebody’s ongoing personal brand, or, worse, an actual corporate brand co-opting the death. We eye these with disdain and move on. We find another eulogy.

The routine of internet grief

This is the routine—now familiar—of internet grief. We’ve done it enough that we know what to do and even what not to do. What’s different about David Bowie’s death is the knowing, almost canny way it was anticipated by the artist himself. I’m speaking of Blackstar, the album he released just days before dying, as well as its music videos, and the off-Broadway production Lazarus—a combined artistic effort that sucks in, accommodates, and ultimately overpowers all these acts of massive, public grieving. Our impulse, in these situations, is to create narratives and order; to eulogize and create legacies; and, in our worst moments, to fight over ownership, over greatest-possible identification, with whoever else might lay claim to it. There needs to be something to do with that feeling, after all. The inverse of this tendency is a retreat into stories, to bid adieu tidily and fantastically: Satoru Iwata mourned over by Kirby and Mario; Robin Williams’ suicide transposed into a freed genie; Jim Henson tearfully played offstage by Kermit; David Bowie, returned at last to Mars. These sentiments help us deal with the fact that a human who was alive no longer is. But they also hide the fact. They soften truths, in the exact way science fiction and fantasy should not.

Blackstar is not tidy. It is science fiction and fantasy the way Bowie always understood it: as a license for wild, unrestrained creativity, and as a reflection of our present. In this case, it was a way for its creator to make sense of terminal cancer. It fits, then, into a tradition of art made while actively dying: Mozart, the story goes, composed the Requiem for himself; James Joyce completed Finnegans Wake while totally blind on his deathbed; J. Dilla sat up punching out beats on his SP-303 as he succumbed to lupus. Blackstar fits into this canon uneasily, sucking the light out of the room. David Bowie aged with proverbial grace, a public symbol of sexual confidence and worldliness as his career stretched into its fourth and fifth and sixth decade. But the actual matter of Blackstar, despite the presence of Bowie’s impossibly fine falsetto, gives us no extraterrestrial, otherworldly advice on how to die. “Where the fuck did Monday go?” he asks repeatedly on “Girl Loves Me,” expressing not the sanguinity we’d hope from old age but a frank anger at the passage of time. The album begins with imagery of a death cult, and closes with no hard-earned peace; “I Can’t Give Everything Away” remains unresolved, beginning with the sentiment that “something is very wrong” and ending with that heart-breaking lament and an almost unfinished guitar solo. In the video for “Lazarus,” he lurches from his bed in distress, and the abler Bowie that emerges from a darkened, coffin-like armoire scribbles furiously at a desk, trying desperately to get as much ink out of the pen as possible. He runs out of paper and starts scribbling on the sides of the desk before slinking back into the armoire.

His death two days later is impossible to extricate from the artwork, in part because Bowie’s longtime collaborator, Tony Visconti, immediately tied them together. We’ll never shake the phrase “parting gift” from Blackstar. It sustains the myth of David Bowie, even as the album dispels it. On Blackstar, Bowie publicly fears death. He shakes in his deathbed. He yearns to create more, to reach “the English evergreens” he’s running towards—and knowing that he will not, weeps. And then the album ends. That Blackstar so nakedly and directly talks about death will not change the way anybody talks about it—the album or death itself—nor will it provide a frame for our many posthumous discussions about David Bowie, what he meant, and what he created. But it is worth at least listening to Blackstar as a suggestion, and beginning to talk about the album not as some cosmic press release from the beyond but as an eloquent forecast of what it will be like to die. To do anything less would be to mistake Bowie’s medium—science fiction—for his message.

An eloquent forecast of what it will be like to die

On the other hand: at its root, immortality does not necessarily mean living forever but instead not dying. Those of us who have only interacted with Bowie through his art can sustain that relationship. We can have the feeling that accompanies death, but the exponentially refracting nature of Bowie’s work—the way Lodger glints off Outside and Major Tom finds a denouement on “Blackstar,” the way Earthling bounces off of Twin Peaks or the way “Subterraneans” crawls between melancholy and hope—will change over time, but it will not die. To wit: There are 26 David Bowie albums, they’re pretty much all great except for Tin Machine, and “Let’s Dance” will slay at every wedding you ever go to. If you like Labyrinth, you’ll still have Labyrinth. Humans are not immortal; art is. This is the sentiment we find comfort in when we imagine artists carried off by their creations, or when we treat them, in death, like the characters they portrayed, whether it’s a Disney genie or Ziggy Stardust. Blackstar, while utterly alive with the fantastical, and so an unimaginably graceful conclusion to Bowie’s body of work, urges us to also take the frightening step of considering its creator’s death as a biological fact. In so doing it tells us not how to die but how to live: to make and consume beauty with every breath that we have, and to do so with absolute, terrifying honesty.

If only Congress worked more like this game

A new teaser for Netflix’s House of Cards plays like a highlight reel of protagonist Frank Underwood’s most heinous exploits. As the show prepares to drag itself into a fourth season this March, it’s worth remembering not just how villainous Frank’s rise to power was, but also how ludicrously easy. The political journalist David Weigel once criticized the show for never exacting its proper pound of flesh in exchange for letting Frank succeed. It was as if every adversary was forced to confront him with one arm tied behind their back. As Weigal wrote, “Underwood’s enemies don’t seem to understand politics.”

For instance, in one of Season 2’s more outlandish moments, Frank can be seen poaching votes from the other side of the aisle in order to pass an omnibus bill supported by the President. Frank’s ability to bribe and coerce some of his Republican adversaries into changing their votes is plausible enough. What’s less convincing is that he’s able to do so at the last minute with limited planning, let alone invoke a series of unlikely parliamentary maneuvers in order to secure the bill’s passage once they renege. The outcome feels at once unearned and ad hoc.

Whip the Vote has no time for personal neuroses.

Ryan Lambourn’s Whip the Vote, on the other hand, is less forgiving but more lucid. Inspired by House of Cards, the game tasks players with negotiating Congressional votes as a Democratic whip. Unlike the Netflix original series, however, the game never stacks the deck in your favor. Instead, it plays like a Machiavellian cat-herding simulator. Convince a Republican representative to switch his vote by ginning up the opposition in his home district only to watch a couple Democrats slip back into the undecided column. Corner a particular politician for too long, forcing them to make unpopular votes, and don’t be surprised if they’re eventually replaced by a hardliner unwilling to deal.

Unlike the Shakespearean drama that animates so much of House of Cards, Whip the Vote has no time for personal neuroses. Lambourn’s exploration of Congress strips away the arcane rules and messy humanity, reducing the institution and its actors to a series of varyingly randomized parameters illustrated with a slick, political cartoon aesthetic. As a result, politics in Whip the Vote are actuarial, like comparing stats on baseball cards. But while the calculus may be difficult to complete, or seemingly impossible to reconcile, the simplicity of it all offers a more clarifying approach to Washington D.C. than nearly anything in House of Cards.

The game’s politicians have clear priorities. For example, representatives who value the chance to vote their conscience are more likely to be swayed by the promise of campaign funds than by shifting public opinion polls back home. By allowing the player to see clearly the political landscape in front of them, and the rules governing different interactions, Whip the Vote offers some insight into how Congress could work, if only it were better designed.

Nowhere is this sentiment made more apparent than when losing a particular vote. Watching the various “Ds” and “Rs” you’ve spent 20 turns courting finally register in either the “Yay” or “Nay” column can be heartbreaking, but rarely frustratingly so. Even if success doesn’t come as easily as in House of Cards, there’s something refreshing in feeling like the system you’re navigating is governed by negotiation rather than rigid ideology. The latter leads to stasis while the former remains dynamic, full of possibilities and has the opportunity for change.

You can purchase Whip the Vote on itch.io.

Go Sunset a Watchman

This past summer saw, within a month of each other, the arrival of two of the year’s most unwanted works: Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman and Tale of Tale’s Sunset. No one asked for, and no one is celebrating, Watchman’s publication. Leaving aside the troubling context surrounding the “discovery” of the book’s manuscript and the alleged role Lee’s caretaker had in its release, there is always an uncomfortable silence after the shattering of an idol. That’s despite the deconsecration of Atticus Finch being especially timely in the context of, say, the swell of the Black Lives Matter movement. In slight contrast, Sunset is a quiet compromise between the more experimental pieces like The Path and Bientôt L’été and more conventional, narrative-driven videogames—and yet it too found few takers because it nevertheless remained transparently highbrow.

And yet these works are oddly twinned: they are both works centred around an angry young woman; they are both entangled in questions of race, agency, and societal wrongdoing. Then there are the similarities that emphasize their dissimilarity: one is set at the relative beginning of the Civil Rights movement, while the other takes place after the movement’s own sunset. Though they approach these characteristics from drastically different angles—to say that one is a photo negative of the other is a stretch, and yet the metaphor does capture the sheer oppositeness of both works—one is the last native glimpse of a world over sixty years old now; the other is an avant-garde example from a studio that has consistently pushed the envelope.

No one asked for, and no one is celebrating, Watchman’s publication

Watchman is a deeply conventional work: twenty-something-year-old Jean Louise Finch (née Scout) returns for a vacation to her hometown, her father, and her boyfriend, Henry. The first half of the book is a combination of setting and flashbacks to her childhood. These vignettes set the stage for the profound betrayal that marks the book’s turning point: Scout surreptitiously observes Atticus and Henry introduce and tacitly consent to one Mr. O’Hanlon, who gives a monologue that would make Strom Thurmond blush. And from this consent cascades a sense of outrage and moral horror at her family, her hometown, and the gap between the polite, genteel exterior and the hierarchical and corrosive interior. So far, so good. The only issue is that Jean Louise takes this revelation as a personal betrayal on the part of her family and community—but that is the extent of her outrage.

Scout’s meeting with her former housekeeper and surrogate mother, Calpurnia, is an exemplary display of this kind of inutile hurt. Having just learned that Calpurnia’s grandson is being arraigned for manslaughter, Jean Louise tries to talk to her old nanny—an old, tired woman, confined to a rocking chair and trapped by the certainty that her grandson will be found guilty “with or without Mr. Finch.” Contrast this hollowness, however, with Jean Louise’s own concern for her sudden sense of hurt: “Cal, what are you doing to me? What’s the matter? I’m your baby, have you forgotten me?” Scout goes on, “What are you doing to us?” What indeed?

It is a poor victim that asks “what about me?” when another’s harm is brought to light. But it emphasizes the solipsistic perspective of this coming-of-age novel. Another example: while confronting her beau over his presence at an all-important town meeting, Henry defends himself by arguing for compromise with the community he lives in.Though he did not necessarily want to attend a meeting where an avowed racist was given a platform, he defends the necessity of his presence: “Look, Honey. Have you ever considered that men, especially men, must conform to certain demands of the community they live in simply so they can be of service to it?” When she calls this compromise hypocrisy, he responds, “How can I be of any use to a town if it’s against me?” This is where the conversation ends: Atticus interrupts, and there is no resolution, no constructive way forward. There is only anger upon anger, hurt upon hurt, all borne from a personal grievance and not any sense of a greater injustice.

But where Watchman’s emotional arc is powered by self-pity and misdirected anguish, Sunset’s is lit up by political and aesthetic outrage, and its rejection is more troubling: it is, after all, a rich compromise between conceptual art and convention. Angela, the protagonist, like Nina Simone and other African Americans who bore witness to the slow rollback of the gains won during the Civil Rights Movement, has fled America—though she still carries memories of burnt-out churches and the difficulty she overcame to earn her engineering degree—for the fictional South American country of Anchuria. But plus ça change: she can only find work as a housekeeper for an hour every few weeks at the penthouse suite of a wealthy aesthete named Ortega. Then the military stages a coup d’état and the country collapses into civil war—yet Angela keeps cleaning. She expresses outrage, fear, weariness, resignation, and hope as she looks at herself in the elevator on the way up to the penthouse each evening. But there is not an act that is not charged with the terror outside—whether she plays a revolutionary song on the piano, or a more nostalgic folk song; whether she responds to her employer’s notes with either affection or a rigorous call to arms. The apartment becomes a refuge from the war outside, but it becomes impossible to fully escape that conflict. The sound of gunfire is carried up to the balcony even as Angela brings her fear for her guerrilla brother’s impending execution to up the elevator.

The apartment becomes a refuge from the war outside

Sunset is a game that asks what we value in art: social commitment or pure aesthetic pleasure? Despite its setting—a rich, open-air apartment filled with modern and classical art—supporting the latter stance, the militant fervour and righteous indignation Angela brings to the apartment every day is the injection of outrage at injustice, preventing naked enjoyment at the statues representing the labours of Hercules. Angela’s rage is twin to that of Jean Louise: there is a grievous wrong that needs righting; Angela, however, has no Atticus to castigate, no symbol to attack. Instead, she curates an apartment and reflects upon the world outside and the items inside,often at the same time. But Angela is not doing anything different than we normally do when engaging with the art in Ortega’s apartment. She brings her lived experience to the piece. What we say about the work is as much a commentary on ourselves as it is on the piece itself. But the corollary of that idea is that we cannot escape the piece’s effect on us: if you gaze too long at a Grecian urn, it gazes back into you.

The apartment then becomes this refuge, and a metonym for the rest of the world: the changes made to it over the course of the game are not moments of self-expression in a void, but reactions to the rising chaos outside. The statutes of the Labours of Hercules, the outré abstract sculptures, the piano, or the canvas-covered armchair are all pieces whose meaning keeps shifting as the progress of the civil war continues. The ivied wall that serves as a marker of the passage of time, the way statuettes shift as they hold down a map of the city, or the sudden closing down of various areas of the apartment, as Ortega turns from curation to preservation, are all testament to the way in which time can shift aesthetic values and interpretations. While critical of various pieces’ opulence, Angela nevertheless helps to secure their protection, and even finds some small comfort in their presence. The progress of time does nothing to dull her rage, but it finds new expression in every interaction with various pieces: the reflecting pool disappears underneath crates filled with straw, the pictures the player has chosen are taken down again. And this shifting valuation even applies to Angela herself, when she steps in front of a reflective surface, the player sees her in the same way as she might another work of art.

These confrontations reach their climax when, respectively, Scout lambasts her own father for his views while Anchuria’s civil war reaches its conclusion with the overthrow of a dictator. In Watchman, the debate that has been smouldering throughout the book’s second half is never resolved. Instead, the project of grappling with the wrongs of the past is transformed into a cute moment where Jean Louise must realize her independence. Her hometown’s conservatism and her father’s paternalism make her realize she must become her own woman, independent from Atticus’ moral compass. It’s a lesson that, perhaps, all those lawyers inspired by Gregory Peck should heed. But by transforming the book’s climax into a lesson, the whole historical context collapses to an interesting background put up for the sake of the main character. Yes, Scout learns to set her own watchman—her own conscience, as it were—at the end; but of what use is that when the conflict raging is inside, not outside, the city walls?There is crisis, and then not so much a resolution as an acclimatization. Her father is still a patronizing racist, and her boyfriend is still a conventional hypocrite, but it’s all okay because Scout has learned that she needs to be her own person.

Angela’s deliverance is found in the end of the war, an experience that becomes an almost religious apotheosis as she has a vision not of the smoking city, but beyond it into the wild, paradise-like jungle beyond the walls. There is a sense of apocalyptic discontinuity, to be sure—this scene represents the entry of a wild, uncultivated, and naturalistic beauty lacking in the videogame’s art—but the overall effect is that of a constant search for some kind of numinous meaning that can be found in the world. It represents the eye searching beyond the city walls for some kind of answer or meaning.

Sunset denies that this solipsism is possible

This, then, is the primary difference between the two works: Watchman is solipsistic in its engagement with the world, while Sunset denies that this solipsism is possible. The complex social and political shifts present in 1950s Alabama are reduced to a sitcom-like moment of personal growth, where all strife is merely meant to serve as a personal opportunity or lesson.The civil strife in Anchuria is inescapable, even from the relative safety of a penthouse patio—and the explosions, figuratively and literally, color the artwork on the walls.

This difference might also explain the various receptions these works had. Watchman came at a time when its literary solipsism runs afoul against a plurality of voices.For who can care about a young, inward-looking woman’s own loss, given the context in which that loss operated? Sunset came at a period where questions of exegesis and videogames are still in their relative infancy. The Beginner’s Guide, it should be remembered, came out only a few months afterwards, and its more straightforward approach to the interpretative relationship between artist and audience was heavily praised. Watchmen was a closed work that came much, much to late. Sunset is a more open experience far behind its rightful time.

A few weeks after Sunset was released, the pair behind Tale of Tales—the Belgian couple Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn—vented their frustrations over the videogame’s reception. As of late July, Sunset had only sold 4,000 copies of the game, inclusive of copies offered to its Kickstarter backers. The studio announced that they were free. Having tried, with their latest venture, to cater to a more conventional crowd, they were now done compromising with the world. Granted, Samyn admitted in a recent interview with Endgaget that the airing of their frustrations had been partially motivated by the need to drum up further sales to pay their collaborators.Nevertheless, their language had the tone of a sincere and righteous indignation, and the zealotry behind the Latin maxim Fiat ars—pereat mundus: “Make art, let the world perish.”

Tale of Tales’ latest project is Cathedral in the Clouds, a digital cathedral created for VR headsets like the Oculus Rift. For the last few weeks, their Twitter account has been festooned with pictures of churches and religious artwork from Ghent to Santiago. The feel of this new project is something of a drastic leap from the political commitment of Sunset: there’s no meditation on art and its place in revolution; there’s only a spiritual retreat into traditional and ethereal conceptions of beauty. The monastic dictum contemptus mundi (contempt for, or perhaps detachment from, the world) is an apt descriptor, but there nevertheless remains a thread of connection between Sunset and Cathedral: the presence of that second word, mundi, and the need for a world to withdraw from. In other words, Tale of Tales’ new project still grapples with the world outside, and all its complexities. But it defines itself by opposition to and distance from that world: sunlight from the outside nevertheless seeps in through the stain-glass windows, coloring the world within.

Create the prettiest planets then watch them spin in your browser

I’ve just done us all a favor. Sure, the North Pole is heating up, the ice caps are rapidly melting. But chill out, the globe spinning in front of me right now, on my monitor, is miles thick in solid ice. Try melting that global warming. Admittedly, I was a little overzealous in my ostensible goal of saving the world. There is no inhabitable land or water left on this planet—at least not for humans and most creatures—only centuries of thick frozen ice to slip around on. That said, humans are probably the worst thing that’s ever happened to Earth, so perhaps by wiping us out I have, indeed, secured the planet a better future.

The digital toy allowing me to play around with this spinning globe all of my own is Oskar Stålberg’s “Polygonal Planet Project.” It’s described as “a study in tilesets”—Stålberg’s interest in this stemming from being a videogame artist—and it is a beautiful thing to have open in your browser. Beyond staring at it, you can use your computer mouse to pop-in and pop-out hexagonal pockets of different types of terrain. Start by selecting a biome theme (forest, ice, town, grassland), then a tile size, and then you can place it anywhere on your planet with the click of the left mouse button. You can also add layers of the same biome on top of another to create rises in the topography; or, similarly, using the right mouse button lets you sink the land all the way back down to ocean level.

an exercise in pure aesthetic

It proves remarkably similar in its experimental playfulness to Stålberg’s previous project, Brick Blocks (2015). But that only let you determine the shape of an architectural structure while the faces of each block fashioned themselves automatically into rooftop terraces or towers pocked with windows accordingly. In Stålberg’s Planet you can decide for yourself both the layout and the motif of each hexagonal tile. Intuitively, it encourages greater exploration with its scientific toolset than Brick Blocks. Even so, it remains an exercise in pure aesthetic, as there are no simulated consequences for your edits to the planet’s surface.

Sure, I turned my globe into a giant snowball, but the results of doing this was all embellishment on my part. When you construct settlements they do not become visibly populated. You can zoom right in with your mouse wheel for evidence but not a single person will be seen. You are a god with all-power but can only build and destroy; life is beyond your control. The closest thing you do get to world simulation are slight tidal changes: the sea’s white foam adjusts to whirl around the periphery of the coasts you have carved. There are also clouds that float by but they’re mostly doing their own thing.

You can create kingdoms amid the ice, hamlets sitting quietly between the trees, even castles sat alone in the sea. But this is all. If you want more, you must imagine the archaeology of your world, informing its current shape, and that might also determine its future. Or you can simply let it spin slowly in a spare tab in your browser so that it may entertain the occasion of procrastination.

You can play Planet in your browser or you can download it here.

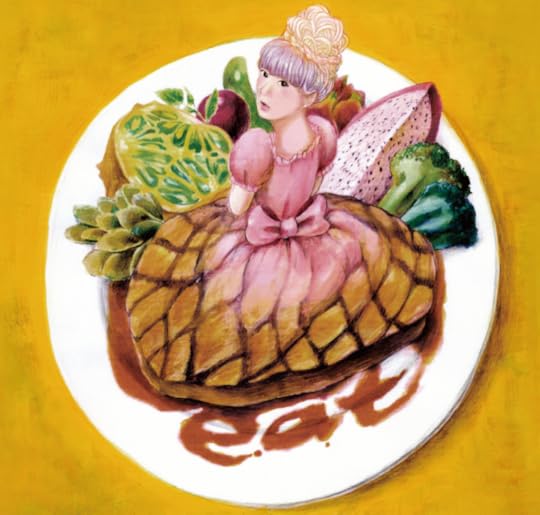

Asami Shigemitsu and the importance of earnest creativity

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Asami Shigemitsu is nothing if not enthusiastic about her art. A freelance video director and illustrator, Shigemitsu is a graduate of the Kyoto Seika University School of Design. She’s had success with creating commissioned illustrations for various organizations and directing a number of music videos for independent Japanese artists. She’s also a big fan of gaming and film, and finds them to be particularly influential on her work. Her directorial style relies heavily on strong color palettes, using bold monochromatic tones to give the visuals a striking look.

Using a variety of motifs and styles, Asami’s work often showcases contemporary Japanese culture, ranging from videos featuring panning shots of classic architecture to high-energy pop punk bands in quirky environments. Most importantly, her work gives exposure to artists and different aspects of Japanese youth culture others outside of Japan may not be aware of. These youth are often seen interacting with elements of traditional Japanese culture, blending them with modern music and performances, as seen in some of Asami’s more striking videos featuring artists dressed in traditional garb or posed in front of classic shrines.

It provides a glimpse into the ways people of a younger generation learn to identify

It provides a glimpse into the ways people of a younger generation learn to identify and embrace more classical elements of their culture while also exploring the integration of new ideas and influences, as is seen with the infusion of pop rock music and Asian music stylings. As a successful artist, she’s very passionate about self-expression and inspiring other young Japanese people to pursue their creative impulses.

In a TEDx talk given earlier this year, Shigemitsu offered advice to young people looking to find new forms of self-expression. According to her, art is an extension of emotion, a way to express how, what, or why she feels things at certain times. This is her motivation to create; it helps her better understand her experience in the world.

January 12, 2016

Introducing Versions, the first-ever VR festival focused on creativity

Though virtual reality has existed in some form since the 1960s, and in the realm of science fiction for much longer, 2016 promises to be a breakthrough year for the technology, with high-profile product launches and major releases in games and film. With that in mind we are thrilled to announce our new conference Versions, organized in partnership with NEW INC, the incubator program at The New Museum.

Versions aims to shift the conversation around VR from one focused on tools and gadgets to a dynamic interdisciplinary discussion that will examine how this technology is being shaped and defined through creative applications. Conversations will span VR’s proclaimed status as an “empathy machine” and how it’s being leveraged by journalists, filmmakers and the military; address urgent questions regarding emerging standards around ethics and practice; consider the technology’s relationship to the brain and its neurological and psychological effects; and uncover how practitioners are exploiting the format’s opportunities for embodiment and immersion.

Through conversations and skills-based learning opportunities, Versions aims to cut through the hype and critically examine the future that we are bringing to life via VR. It’s not about what the technology can do, it’s about what we do with it. We want to show how creative applications of new technologies allow us to surpass their out-of-the-box options, and why the future of this new technology will be equally invented by artists as well as engineers.

Keynoting the inaugural conference is legendary filmmaker Douglas Trumbull, who directed Brainstorm and supervised special effects for Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and countless other keystones of American cinema. The panels are comprised of experts from the diverse array of industries converging on this moment in VR, well-equipped and excited to discuss the issues facing this emerging medium.

You can learn more about Versions on our website, and apply to attend the conference and workshops, March 5-6, 2016 at The New Museum in Manhattan.

Header image from Brainstorm, courtesy of Douglas Trumbull and MGM/UA Entertainment Co.

Body text image courtesy of BeAnotherLab.

Beyond the veil of Counter-Strike

Robert What wants to take Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (2012) back from the people who made it—yes, Valve. Despite the multiplayer first-person shooter proving enormously popular, What wants to see it undergo a conceptual transformation; from a series of static, made-to-look-real maps made for online competition to “dynamic spaces of artistic contemplation and social interaction where interesting events spontaneously emerge.”

He has a theory but, before that, he has a gallery of tailored images called the “CS:GO Noclip Exhibition” that attempts to unravel it. In total, the gallery includes 396 screenshots from around Global Offensive‘s many maps, all taken and curated by What himself. These screenshots make use of the “noclip” command that lets you float and fly around the gamespace, passing through the walls and barricades that typically keep players boxed inside the map.

Due to this, most of the images reveal the surrounding voidspace that always lingers just out-of-sight beyond the veil of videogame worlds. The way he frames this emptiness is often striking. Walls that were once brick are now transparent to reveal a magnificent grayspace. Terraced houses stand lonesome and fragmented against an endless hue. Entire industrial buildings are revealed for their criss-crossing complexity when viewed from underneath without a floor. It looks like a world at its end as it is shredded towards non-existence.

“This project conceives the voids between surfaces (andor surface-voids) not only as a postmodernist critique of digital architectures, but as a means to rethink relationships between subjects and virtual objects of architecture and suggest other forms of open reading,” writes What. He adds that using tools like noclip to explore virtual maps beyond their perceived borders gives rise to “unexpected hyperreal delight / an uncanny space of displacement.” In becoming this type of virtual tourist we are able to better understand the blueprint of a gamespace. Some players use this information to find exploits that allow them to cheat the system when playing online matches. But What wants us to go further: to move beyond the constraints of the system’s rules entirely as Valve has written them and find a new type of playful expression.

“to move away from static maps to constantly moving systems of artistic expression”

This desire is discovered in What’s previous writing on “Thinking beyond game maps and levels” as well as his notion that game engines should be “Play Enablers” that service “player based design.” In essence, What wants to see game engines shift away from being used to create deliberate and restrictive games shipped as products, and towards facilitating accessible and more immediate expressions of play. It might seem that he’s asking for the creation of the Source Engine-based sandbox creation tool Garry’s Mod (2004) but he’s clearly aware of its existence and seems to be suggesting something more. In any case, “CS:GO Noclip Exhibition” demonstrates how applying this thinking might change an existing videogame.

“Imagine being able to position oneself anywhere in a game map and witness cool strange events occurring while you customize the immediate area with art objects, even adjust the ambient tone to fit your mood,” What writes. “That is, to move away from static maps to constantly moving systems of artistic expression, where how you play–ie. aesthetic style–becomes far more important and interesting.”

You can see some of the images of CS:GO Noclip Exhibition here and follow the links on that page to see the rest.

The most subversive uses of drone technology

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Initially known to many for their military use, drones have evolved quickly into tools for creating and enjoying new experiences. They have become flying extensions of the human desire to innovate, help people and have fun. Nearly four million commercial drones are expected to sell this year, rising to 16 million a year by 2020, according to a new report by Juniper Research.

“Three years ago, this technology was so expensive, so unattainable, that only the professional cinematographer could afford it,” said International Drone Racing Association CEO Charles Zablan in an interview with The New York Times. Zablan said that now a full drone racing kit with flying google can be bought for about $1,000.

flying extensions of the human desire to innovate

Like many new technologies that become affordable and widely available, these flying robots are proving to be useful as well as entertaining. In war-torn Syria, drones are delivering food to starving villages. Drones carry cargo so frequently in Rwanda that they have their own airport. While drones bring stunning aerial video perspectives on life, they’re also inspiring people to create art and invent games that never existed before.

Here are five innovative ways drones are bring used:

Drones on the Silver Screen

Using drones to capture footage that would normally require expensive helicopters or cranes is more common not just in major Hollywood productions but also in videos created by small production houses and even amateurs. In “First Flight of the Phantom,” viewers see the oft-filmed grandeur of NYC from a totally new perspective, with the DJI Phantom moving from street level to building-top in one continuous shot. It’s not just for smaller indie films, either — Chappie, Neil Blomkamp’s latest venture into South African sci-fi, filmed several of its action shots with aerial drones. This November, the Flying Robot International Film Festival will even make history as the first to feature films exclusively made by, and about, these autonomous flying devices.

Drones Scare Geese to Protect Other Animals

On the beaches of the Ottawa River, geese reign wide swaths of land as tyrants, proving resistant to all efforts to dislodge them and rendering most of the watery real estate uninhabitable. Ottawa, however, has a new trick up its sleeve. The GooseBuster is a drone fitted with speakers blaring the howl of a grey wolf as it zooms through the air (geese hate flying wolves). Unsurprisingly, it’s done wonders, scaring off the winged bullies at lightening speeds. Aside from terrifying geese, drones can also be used to protect endangered animals. Lian Pin Koh and Serge Wich, two scientists spearheading conservation efforts for the Sumatran orangutan, developed an inexpensive, lightweight drone that maps large swaths of land, a process that was once costly and time-consuming. They’ve even used their drone to take aerial photographs of orangutan treetop nests, something that’s been impossible to do in the past.

Drones Capture the Eye of the Storm

Because drones are unmanned and cheap, scientists can send them into all kinds of dangerous situations. One explorer, Sam Cossman, even sacrificed a camera-mounted drone to capture mind-blowing images and footage of active volcano Vanuatu. For those more interested in academics, drones can venture inside a tornado. Right now, scientists have a lot of questions about how tornadoes are formed, and although the movie Twister showed otherwise, humans can’t safely collect data from the center. Engineering students at Oklahoma State University could be changing that in the future. They are working to develop drones capable of flying into dangerous storms and collecting data.

NASA is also developing a drone for monitoring dangerous weather: The Hurricane and Severe Storm Sentinel, or HS3, studies the storms from above, closer than any piloted aircraft could ever safely attempt. “Our hope is to be able to make better predictions about the impacts of hurricanes,” meteorologist Sharan Majumdar told Discover Magazine. That’s certainly a crucial task, considering how hard coastlines around the world have been pummeled by severe weather in the last few years.

Drones Lift Urban Artists

When these flying machines are used for surveillance and military combat they invoke authoritarian symbolism, so it was shocking for many to see rebellious drones defacing a colossal Calvin Klein outdoor advertisement in New York under the dark of night.

“It’s exciting to see its first potential use as a device for vandalism.”

While the art itself wasn’t terribly impressive, it’s the kind of performance that could never have been accomplished by mere human hands. As drone technology improves, so, too, will the displays of public tagging. “Seventy percent of the concentration is in maintaining this equilibrium with the two dimensional surface while you are painting,” KATSU explained to Wired. But he seemed optimistic about future careers of drones as graffiti artists. “It’s exciting to see its first potential use as a device for vandalism.”

Drones Join a Fight Club

The dream of battling robots to the death has been around ever since robots were first imagined. Something about unmanned machinery summons the inner toddler in everyone who used to mash action figures together until a limb popped off.So it seems only natural that the most exciting use of this high-tech gadgetry is making them fight each other for human amusement. Robot Combat League, anyone? But fighting while flying takes the amusement to new levels.

The Aerial Sports League (ASL) currently leads the pack in flying robot death matches, featuring races and obstacle courses for pilots to navigate. But ASL founder Maqrue Cornblatt points out that the heavy-duty drones used in these sports are great for reasons other than aiding destruction. “They’re really ideal for STEM and educational outreach,” he explained. “It’s a drone little kids can build and smash and take apart and rebuild over and over again.” Cornblatt and his team specifically incorporated “pit stops” that allowed pilots to fix their fighters on the spot, making drones sports a fantastic hobby for burgeoning engineers. “We have an intrinsic human desire to see violence,” Cornblatt said. “But to put it in this context, where it’s safe and actually educational, is extremely rewarding.”

Presumably, though, it’s only a matter of time before flamethrowers and buzzsaws are added to the fray. As drone technology continues to improve, philanthropists, makers and rebels will find new and interesting ways to entertain, inform and accomplish their goals.

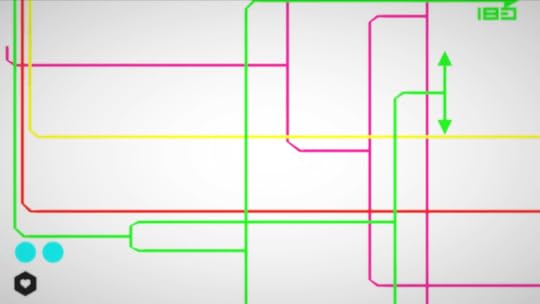

In Line/Dash, you are both maze-maker and maze-runner

It’s a chicken and egg problem, and one with deep roots in videogaming history. And we’ll get to that, I promise. But first: some words about Line/Dash.

Created by Davide A. Fiandra, Line/Dash is a minimally modernized arcade game. Blocks float across the screen rom right-to-left. Your job is to intercept them before they exit stage-left. This is done by launching lines in their direction. At the click of a key, a line starts working its way downwards. At the click of another key, said line branches off to intercept the incoming block—or at least it does if everything is lined up correctly. Easier said than done.

Supposing, however, that the interception has been successful, that line can then branch off into two vertical and then horizontal stems to intercept another oncoming block. On and on it goes until one block escapes your linear reach. Your score is recorded. Play again.

This may not sound like much, but Line/Dash is profoundly addictive. Its lines and blocks collide with a pleasing thud. The whole screen shakes. What starts as a black-and-white color scheme gradually expands to neon shades on alternating black-or-white backgrounds. The game rewards reflexes with linear tableaus. A good round produces a score, sure, but also something that resembles a demented subway map.

“a procedural player-controlled multimedia sculpture”

Fiandra says the game “doubles as a procedural player-controlled multimedia sculpture,” which, insofar as all games can be art, is probably defensible. The underlying premise holds even if the ultimate conclusion is a bit of a reach. Still, a static image of Line/Dash does raise an important interpretive question: Are the lines barriers or live actors?

This question dates back to Snake, the arcade/early cellphone/graphic calculator-game, in which a line (umm, well) snaked around to gobble up dots and progressively grew longer. As this line extended, it began to serve double duty as a barrier. Snake, at the highest level, asked whether a maze, by dint of being self-made, could also be a maze runner? Line/Dash, with its similarities to Snake, doesn’t so much answer this question as it mines it for artistic inspiration. At any given moment, you may be building the maze or trying to navigate it. Insofar as that’s an interpretive challenge—and a fun one to solve at that—Fiandra’s claims about multimedia sculpture may not be so far off the mark.

You can purchase Line/Dash on itch.io and Google Play.

The impossibility of sadness in That Dragon, Cancer

Art has always been useful for drawing our attention to the controversially sad. Take something like Zoe Quinn’s text adventure Depression Quest; depression is, by its nature, a miserable affliction, but it is also a diagnostic category burdened by stigma, shame, and skepticism. Some people insist that reliance on psychotherapy or medication is a sign of moral weakness, while others deny that clinical depression exists at all. Playing Quinn’s game and allowing yourself to feel sad therefore becomes a form of social action; to play is also to take a stand, placing yourself on one side of a debate. The sadness intertwines with a kind of proactive anger to challenge the status quo and advocate for the disenfranchised.

The role of art in unpacking incontrovertible sadness is more ambiguous. When I was in college, some friends and I went to see the play Rabbit Hole on Broadway, which follows a couple as they attempt to grapple with the death of their young son. We were all studying playwriting at NYU at the time, which is to say we were a bunch of snarky 20-year-olds who made it our business to be hard to impress. One of my friends succinctly captured our collective impression of the play when he later said that “the only thing Rabbit Hole taught me was that the death of a child is sad, and I’m pretty sure I already knew that before I sat down.”

the pain feels real, the sadness is authentic

Ten years later I’m a little wiser and a lot less snarky, but I still don’t think Rabbit Hole is a good play. Its emotional punches land squarely on the nose, yet its point-of-view is absent. One ends up feeling manipulated by such a work: we are made to feel sad because, well, it’s sad to watch parents grieve for two hours. No one could argue with that. But what’s the point? There is no stand to take, and any anger evoked cannot be put to productive use. What can be gained by such an exercise? Then again, perhaps the idea that something should be gained is simply an indication of our discomfort with facing the undeniably tragic.

Rabbit Hole and other works like it are easy to criticize because their chief flaw is a sense of inauthenticity. They take advantage of an audience’s response to universal sadness in order to present themselves as prestigious and deep, and as a result leave a cynical taste in the viewer’s mouth. Numinous Games’ That Dragon, Cancer does not suffer from this problem; the pain feels real, the sadness is authentic. This is not surprising given that the game is undisguised autobiography: Ryan and Amy Green created it as a meditation on their family’s journey as their son Joel was treated for and eventually killed by brain cancer.

The story behind the work is compelling, but it is hard to know how to approach That Dragon, Cancer for the purpose of review. The developers refer to it as “Myst without the puzzles,” but a more apt comparison might be Davey Wreden’s recent The Beginner’s Guide, as the game is composed of several short vignettes that follow the Greens’ tragedy in more-or-less chronological order, while stylistically fluctuating between the literal and the expressionistic.

I did not feel cynical while playing That Dragon, Cancer; it has a point beyond bumming the player out. This game—and I imagine the process of creating it—represents a personal therapeutic exercise by two parents working through their grief. What players derive from it, therefore, is entirely dependent on their personal relationship with both the subject matter and the ways in which the Greens come to make meaning out of their experience. I cried once during my playthrough—early on, when listening to Amy describe the envy she felt over other parents at the hospital being able to celebrate end-of-treatment parties with their kids—because it was so sad. I thought, “This is the worst thing.” I thought, “Cancer sucks.” Then I didn’t know what to think.

The emotional core of That Dragon, Cancer is real—so real, in fact, and so personal, that I ended up feeling like an outsider looking in. I pitied the Greens for having to endure this awful series of events, but I did not come away feeling connected to their experience, or enlightened by it. This was not because the game tried but failed to connect with me, but because it didn’t. There is an insular quality to the vignettes; they are by and for the family Green (and, perhaps more broadly, others who have lived through similar trials). The “point” of the game is that this is how Ryan and Amy are dealing with their loss. I can praise or criticize it, but really my opinion is irrelevant. This game was not made for me, and reviewing it feels like a borderline intrusion into a family’s private mourning.

reviewing it feels like a borderline intrusion into a family’s private mourning

The greatest reason for my disconnect is due to the fact that the latter half of the two-hour playthrough increasingly focuses on the Green’s reliance on their Christian faith as a means of understanding and coping with Joel’s illness and eventual death. Before playing, I had assumed that the game’s title was a nod to fantasy tropes ubiquitous in role-playing videogames—and indeed, throughout That Dragon, Cancer classic gaming imagery from Mario Kart to arcade platformers is evoked in iterative attempts to find a metaphor that might actually fit the ever-shifting monstrosity of disease. But for the Greens, the titular dragon turns out not to be an RPG’s final boss but rather one of the Arthurian variety: an evil to be battled by brave Christian crusaders, pure of heart and clean of soul, who know that even losing the fight means an unfettered ascension to god’s heavenly kingdom. As a secular existentialist Jew, it may go without saying that by ultimately settling on this metaphor, the game started to lose me. But I think it also got away from the Greens. The voicemail recordings and intimate conversations that rang so true in the early scenes began to be replaced with more heady discussions of grace and divine intention. Powerful imagery of drowning in a storm and pulsating black tangles turned to a staid letter from Ryan to Amy and a bucolic paradise where Joel enjoys an eternal picnic. Everything ends up in its right place. The suffering was simply too great to bear it any other way.

The most effective scene in the game takes place in a hospital room. You are looking through Ryan’s eyes, and, interestingly, Joel is not physically represented in the space. His crib is there, empty, and next to it is all manner of medical accoutrements. You can walk to the bathroom, look out the window, but you cannot see Joel. You can hear him, though, because he won’t stop crying. There are only a handful of clickable hotspots and none of them do anything of import. All you can do is wander around this tight space for several minutes, listening to the blistering screams of an invisible child who doesn’t understand what is happening to him, unwilling to leave, miserable to stay.

This is sadness. Our task, I think, when faced with this kind of sadness, is not to force it into an ill-fitting symbol, or turn it into a cause, or define its point. Our task is to sit there for a while and feel its invisible weight, its randomness and cruelty. But I understand why the Greens could not stay in that space for long. Who could? I applaud that they tried, and I am sorry for their loss.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers