Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 171

January 25, 2016

Splatoon makes a splash in Japanese esports

Japanese players embraced Nintendo’s colorful, team-based squid shooter Splatoon with open arms (or tentacles) in 2015. Featuring half-squid, half-human creatures who can swim through the ink that blasts from their guns, Splatoon is a fast paced and accessible game making a mark on Japanese esports.

Following its release in May, the game moved over 800,000 copies across the country and boosted Wii U sales. Japanese players are spending more and more time with these squids, too. In fact, many U.S. Splatoon players now express dread at facing off against competitors from across the Pacific because they are just too good to beat.

“I play Splatoon almost everyday,” admitted a Japanese player known as Ryo. “I can’t stop thinking about how to play on each stage or figuring out strategies for each weapon in my spare time.”

Now, Nintendo hopes to catapult Splatoon into the world of competitive gaming, by holding a series of tournaments dubbed the Splatoon Koshien (in reference to a famous Japanese summer baseball tournament.) Beginning this past September, they’ve already held competitions across the archipelago, leading up to the grand finals set for this January’s Niconico Tokaigi (“game party”).

The stakes are high for players: the Splatoon squad that wins will take home approximately one million dollars. But for a country that has been slow to embrace esports, it could also popularize a hobby usually thought of as niche.

Unlike other Asian countries, Japan has not fostered an avid esports community that regularly tunes into broadcasts of League of Legends tournaments and the like. The Japanese competitive gaming scene has centered mostly on console games, while esports elsewhere moved to PC titles. Existing tournaments tend to be smaller affairs held in arcades rather than big stadiums like LA’s Staples Center.

SPLATOON’S GAME WORLD IS POPPY AND BRIGHT

But Splatoon fostered an active community in Japan from the get-go. It’s an online community that player Nemu Nemu said flourished through a few small fan-organized tournaments prior to Nintendo’s official Splatoon Koshien. “I often Tweet to find people who I can play with and build my strategies from those experiences,” Nemu Nemu explained.

The announcement of Splatoon Koshien prompted extra excitement in the community, with players such as Nemu Nemu scrambling to find a team. He hooked up with a player named Mochi to join a team called YumeiiroBWI for the Kinki area competition in Osaka.

Ryo and his squad Ika Se No Gorilla’s origin sounds like a story worthy of a coming-of-age movie. “I grew up with our leader Shamoji, but I met our other members, Pushu and Amane, online. They’re the people I’ve always played the game with since I started.”

Despite feeling like they weren’t “skilled” enough to win, YumeiiroBWI entered the Tokai tourney held in Nagoya’s Hisaya Odori Park on October 11th.

To an extent, the excitement over Splatoon Koshien is helping to legitimize competitive gaming as a whole in Japan. Japanese esports needed a fun and accessible title that both avid players and non-players alike could enjoy watching.

“Splatoon’s game world is poppy and bright, I never feel unhappy while playing,” Nemu Nemu said, highlighting the game’s potential to become the country’s most popular esport. The rules of Splatoon are also much easier for casual spectators to pick up on, especially when compared to the complexity of a game like League of Legends.

THE STAKES ARE HIGH FOR PLAYERS

Of course, there are roadblocks in Splatoon’s journey to becoming a legitimate esport. Many point to the game’s lack of a voice chat, which makes it hard for team members to communicate, as well as the lack of a designated “spectator mode” for broadcasting tournaments.

But so far the Splatoon Koshien events, which are part of a larger tour with competitions for other games, have been held in more public and popular spaces, attracting solid crowds.

“The audience was so fired up, it felt like a festival,” Nemu Nemu said of the Osaka stop.

Japanese video site Niconico livestreamed some of the tournaments too, such as the Nagoya competition, helping to spread the burgeoning esport to even more viewers. Ryo, accustomed to online battles, initially felt overwhelmed by the live setting. “There was something, an energy, you can’t experience unless you’re at the actual venue.”

And, like all good competitions, Splatoon Koshien has had plenty of dramatic showdowns so far. Nemu Nemu’s team, which he joined specifically because he believed they had the best chance to take first place, has been challenged by equally strong outfits. They even lost a match.

“But we followed the strategies we trained with, and knew the worst thing we could do was become rushed and frustrated,” he explained. YumeiiroBWI went on to take first place in that competition.

Ryo and Ika Se No Gorilla’s run ended up being even more thrilling. “To be honest, we didn’t really have a strategy, beyond ‘let’s win,’” he said with a laugh. “We had moments where we struggled in every game.”

SPLATOON’S FUTURE AS A COMPETITIVE GAME LOOKS BRIGHT

But they managed to squeak through anyway, landing in the final game. There, they took advantage of a Splatoon rule where, by covering more of the stage in their ink, they eked out a win at the Tokai regional championship.

Both Nemu Nemu and Ryo’s teams are headed to the grand finals in Tokyo at the end of January. Both say they are practicing and preparing to compete in front of larger crowds than ever before.

Considering just how many people already love the game, Splatoon’s future as a competitive game looks bright. “I think there’s a big chance for Splatoon to become a popular esport,” Ryo said. “It has tons of users, the title is famous enough, and you can have fun and get excited by both playing and watching.”

Paint splatter image via Womb Gallery

Online play and Drawing images via Kana Natsuno

The only opinion of The Witness I care about is Soulja Boy’s

I love Soulja Boy almost as much as Soulja Boy loves videogames. He was supposed to disappear after 2007’s “Crank That”—a misogynist dance anthem that was embraced, largely, sarcastically—but instead he hit the gas, beefing like crazy, flirting with major-label pop, and then dissolving in a haze of weird, fractured mixtapes. Early on, he co-opted the image of Sonic the Hedgehog, and in some ways that remains the defining image of the emcee, spinning wheels and flying off to god-knows-where. He could release something like the lacerating, subversive “Turn My Swag On,” on which he defied all reason by electing to sing for an entire track, on the same album as the saccharine teen-rap “Kiss Me Thru The Phone.” One of my absolute favorite Soulja Boy moments ever is this 2008 interview in which he absolutely clowns class-of-’08 also-ran Charles Hamilton for deigning to also like Sonic the Hedgehog. (Pretty much everything he says in that interview is offensive.) He is an enormous nerd who has named mixtapes after both Naruto and Mario.

I related more to his interactions with the game

Anyway: Soulja Boy was also an early-ass adopter of the Xbox Live Arcade, back when that was a thing people gave a shit about (the late-aughts were crazy); he regularly invited other people to play with him by regularly sharing his screenname, which also felt sort of revolutionary back in 2008. (He was in his teens then, and proud of his custom 360 in the way only a new-money 18-year-old could be.) One day he got massively faded with his friends and downloaded Jonathan Blow’s Braid—which, to most people, was just this thing that popped up on your 360 menu, and not an Art Game Classic—and filmed a video going bananas over it. Here is the video, and below that, a partial transcription:

So they got this game, right, for people who smoke or people who drink. Like, if you drink beer and you get drunk, or if you smoke weed and you get high, or anything—if you just be getting fucked up. They got this game right, oh no, this shit called Braid. Oh, fuck! Hey, watch this shit. It’s about this little guy in this suit and he walk around. It ain’t got no point to the game. He just walk around jumping and shit. It look like Mario in the future, and it’s Mario in a business suit with his hair dyed orange and a tie on. And he just walk around jumping on shit but the funny part about it—you can do this right here, watch this. Yee-up!

The yee-uping continues for awhile as Soulja Boy engages Braid‘s signature time-reversal mechanic. He finds this extremely funny, because it is extremely funny. This is the exact effect Blow’s game was intended to have on players, despite its somber music and surfeit of text: To shock and delight them with its tidy dismissal of one of videogames’ central mechanical conceits.

After awhile, Soulja Boy continues:

You see how far I rewinded that shit? What make it so funny (is that) he don’t ever run out of “going back in time” potion. He just go back in time forever. There ain’t no point to the game. He just go around. This shit is stupid as hell, man.

Now, you may disagree with those last couple sentences, but “‘going back in time’ potion” is a hilarious way to talk about this game. Many news pieces at the time delighted with a troubling condescension in Soulja Boy’s word choices, but I confess that I related more to his interactions with the game than many of the bleeding-heart reviews that met its initial release. I’ve softened to it over time (the classic analysis by Taylor Clark helps), but its portentousness felt overblown, and quite in need of this puncturing. This was a game about Mario in the future with a fucking tie on.

get Soulja Boy to record a review of Jonathan Blow’s new game

All of this is to admit that one of the great dark spots on my career going forward will be my inability, in two years of trying, to get Soulja Boy to record a review of Jonathan Blow’s new game, The Witness. In point of fact, I’m not even sure if Soulja Boy is represented by a traditional PR agent anymore. But I wonder: Has Soulja Boy changed? Will The Witness be as contentiously somber as Braid? How have Soulja Boy and I grown apart over the years—maybe he’s ready for the game’s long haul in a way I’m even less apt to. Will the game’s mechanical innovations shock, as Braid‘s did, requiring a reconfiguring of our critical vocabulary—and, indeed, Soulja Boy’s?

Wherever you are, Soulja Boy, I’m begging you: record a video review of The Witness. Answer these questions. If the game’s reception is anything like it’s predecessors’, we’ll need it.

How “girl games” will save the post-apocalypse

A disaster completely destroys your city or country, what do you do?

Thankfully, numerous videogames have prepared everyone for such a scenario. You immediately go on a killing spree as you look for The Thing that will improve your life, of course. Following 2013’s The Last of Us, you might bring a critical survivor to an important location, shooting mutated humans in your way, scrapping for supplies. Or you could seek vehicular vengeance a la Mad Max (2015). Alternatively, perhaps you need to look for your father, barreling across a hazardous wasteland, helping to purify water when you’re not firing slugs into molerats—yep, that one’s Fallout 3 (2008).

What do you do after you find The Thing? Well you take the points or upgrades or materials you’ve acquired from shooting and running over things, and use them to get better at shooting and running over things.

These games always answer the question of what to do on an individual level, but rarely do they address it on a societal level. They’re pure, indulgent, aggressive macho fantasies. The world will not be stable if we all follow their example: everyone running around and shooting people for spare parts, trying to find a lost paternal figure. There’s a bigger question that these games have ignored for the sake of their power fantasy. What is a society supposed to do when a nuclear weapon or zombie outbreak or global warming has destroyed everything? Beyond that, what constitutes a society in such a state?

These are questions that last year’s Fallout 4 has started to explore. It believes the answer lies in interior decorating, borrowing from a thread of game design typically categorized as “girl games.”

If you haven’t peered over the gender divide of games recently, girls are being tasked with finding joy in domestic labor and maintaining strange beauty rituals in “girl games.” These games share themes of dressing up, cooking, caring for children and pets, and decorating a home. In sharp contrast to the violent and self-interested masculine themes of many post-apocalyptic games, these games groom girls to think about other people, even though videogames are commonly hoisted as a place for a solipsistic form of imagination. Novelist and literary critic Margaret Atwood’s wisdom applies here: “Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a fantasy … You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.” Whether it’s helping a princess apply layers of green goop to make her aesthetically appealing to her prince (Princess Jasmine Birthday Party Prep), cooking with a baby (Baby Hazel Cooking Time), or decorating a house (Dollhouse), you are a girl watching yourself play male-defined roles of womanhood.

PRETENDING YOU AREN’T CATERING TO MALE FANTASIES IS A FANTASY

Because games are so heavily gendered in what is seen as appropriate or natural forms of play for boys and girls, they end up being unhealthy caricatures. Whereas many post-apocalyptic spaces seem to punish players for being empathetic or nonviolent with a quick death, many “girl game” experiences punish you for not constantly seeking approval through appearance, interior decorating, domestic labor, and mothering skills. One is deeply self-interested; the other is a form of shallow martyrdom.

There are meaningless and limiting parts of “girl games”: the emphasis only on others, the importance of looking attractive to men, the supposed joy of vacuuming. Thankfully, Fallout 4 discards these as it tries to strike a balance between individual fulfillment and altruism. When you are asked to build a settlement in Fallout 4, you can see a little “happiness” meter. After placing your first rug, or framed picture, or jukebox, this meter increases. Slightly. It’s a little clumsy, and very game-like to assign a number to happiness, but the idea it’s communicating is powerful: these small indulgences, these acts of adornment are what make a community. These settlement-building systems only make sense in the context of a violent world; on their own they are empty gestures.

You are of course free to ignore some of these features. You can go through the game and not really decorate or clean up even one of your settlements, in the same way that you can choose to not play with a helpful follower. But it becomes a deeply isolating and selfish exercise to pick up materials to only use for guns and armor upgrades, or to make more drugs to inject. It can make you feel like an unpleasant vulture. You know what feels great? Building a market stall and having characters walk around it. Making a beautiful chair and seeing a settler sit down in it, with “The Swan” playing over the radio that you gathered parts to build. It’s rewarding, welcoming to return to your settlement after a battle with yet another band of raiders, with the generators humming, cooking a deathclaw steak as a settler farms in the background.

And the game’s systems offer answers to the question “what makes society” over and over. Fallout 4 encourages you, while wandering through abandoned buildings, to take look at the irradiated trash that used to be a home in a different light than its predecessors. The series has always made it clear that searching through rubble can reward you with better guns and armor, but now it’s also a way to build and improve a settlement and its community. A desk fan is an opportunity to use the gears to make a water pump. The circuitry from the telephone next to it can be used to make a turret to protect the town and the people you’ve brought to it. You also discover that, as you spend more time with your followers, they will slowly open up to you if they witness actions they agree with, and you begin to learn about their drug addiction or their struggle to overcome their past. This iterates the idea that your story is not the only story to experience. In fact, one conversation with your robotic butler and housekeeper Codsworth alludes to the importance of keeping company throughout the game. You emerge after 200 years of being frozen in a vault, and upon reuniting with your old friend Codsworth, he talks about his loneliness: “Two centuries with no one to talk to, no one to serve. I spent the first ten years trying to keep the floors waxed, but nothing gets nuclear fallout from vinyl wood. Nothing! And don’t get me started on the futility of dusting a collapsed house.”

FALLOUT 4 TRIES TO STRIKE A BALANCE BETWEEN INDIVIDUAL FULFILLMENT AND ALTRUISM

The Fallout series has always featured places where you could see other people buying and selling items or living in hotels, and sometimes you could have a small home of your own. But you were always a wanderer, and you could only ‘help’ others by going out and killing or retrieving something they required. Now, you actually get to build that town. You can explore the wastes, gather up everything that has been destroyed, and use it to improve the lives of other people. It’s drawn out the deeper meaning of those home decoration and cooking games by putting them in the context of these violent and unstable worlds. It turns these “girl games” into acts of defiance against raiders and enemies who try to hurt your settlers and upset the community you’ve created.

Other games are enabling these behaviors too, and their players are embracing the change. Look to the Dark Souls (2011) and Bloodborne (2015) communities, which love to defy what makes for good defensive armor by engaging in what has been deemed “Fashion Souls”; piecing together outfits based on aesthetic or cosplay goals rather than chasing increased protection against attacks. Last year’s Undertale also enjoyed upending the whole notion of violence. Maybe, it suggests, that monster you’re fighting can be overcome by showing it love and by not bullying it into submission, or to death. In Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons (2013) and Fable 2 (2008), sometimes the quiet moments spent with your companion say more about time well spent than resolving the fate of the world. Whether it’s being silly with your appearance for the entertainment of a community, viewing empathy and kindness as signs of strength, or giving time to treasuring moments of connection, these features borrowed from “girl games” can prove more fulfilling, more meaningful than bludgeoning a person’s face.

The pink shanty town built for girls is cramped and vapid. The grimy, slaughter-happy wasteland reserved for boys is bleak and tiresome. After years of videogames encouraging players to run riot in the latter, perhaps they’re steadily realizing that a dilapidated settlement covered in strings of lights and a frilly rug is a welcome sight.

Featured image via khreesy

January 22, 2016

Grimes’ new music video is the epic finale to a sublime YA trilogy

The wait is finally over, Grimes fans—Kill V. Maim, the epic final chapter in the Art Angels trilogy, is finally here. And, boy, does Claire Boucher deliver. (A fair warning—the following contains spoilers, enthusiastic though they may be.)

What more emotionally resonant opening could Kill V. Maim begin with than a race across the ruined city of Neonopolis? Atop her Doomsday Cruiser, our protagonist Grimes looks out at her childhood home; everything she’s fought so hard to prevent has come to pass. This is, of course, after she’s become a vampire. Oh, she may smile and jape with her brave band of Synth Raiders, but Boucher reveals a fine hand for subtlety in her dialogue here. Inside we can see Grimes’ heart is breaking. But even in all this (admittedly neon-saturated) darkness, hope still shines.

The Ailing King confronts Grimes

All of Grimes’ hardship over the course of this music video series—as diehard fans will know—can be lain at the black, buckle-clad boots of The Ailing King, who appears here early and in full menace. The flu mask-clad villain has tormented Grimes since the beginning, and was personally responsible for infecting the twins Puck and Patch. Their story still tugs at my heart strings—their minds rotted by the illness, their muscles confined to short, jerky movements, the twins are still determined to protect their friend.

She emerges covered in blood, exhausted, but alive

The stakes of Kill V. Maim couldn’t be higher: if Grimes can kill The Ailing King before he can infect all of Neonopolis, the city will be saved. Of course, this is hardly an easy task, as she and Valentine Trueshot, her trusted advisor and master archer, will have to fight their way through his legions of Viral Ravers first. In this intense and exhilarating scene, Grimes is pushed to her physical breaking point. She emerges covered in blood, exhausted, but alive—thanks, no doubt, to the training she received from the three-eyed monks of the Vivid Dream.

Valentine Trueshot, taking aim

I admit, the dream sequences which found Grimes wandering through the prison of the underworld were too vague and mysterious for my taste. It felt like Boucher was satisfying some literary impulse, and in doing so strayed from the propulsive pacing of the rest of the series. As we approach the finale, though, this confusing subplot is revealed to be the setting for the final confrontation between Grimes and The Ailing King, with both of them ascended to dark angelhood, as the prophecy in the first installment foretold.

Grimes, post-ascension

Ultimately, Kill V. Maim concludes the trilogy with an explosive, heartfelt, and inspirational finish. Boucher’s Art Angels series gave a generation of girls a spunky, clever hero to see themselves in, and this final installment is everything it should have been.

Prepare for an “artful escape” into the world of psychedelic folk singers

The weight of artistic expectations, particularly in the era of peak content and endless aggregation, can be crushing. A story about the next big thing and why you should care (what to expect when expecting an album?) lurks around every corner. While some reactions to this scenario are better than others, no sane person can be expected to react with utter nonchalance. This question of how an artist responds to these pressures is both the text and subtext of The Artful Escape of Francis Vendetti.

Let’s start with the former. Developed by Beethoven & Dinosaurs, The Artful Escape follows Francis Vendetti, a young folk singer who goes on the lam a few hours before his first concert. The triggering event, it appears, is the sight of his father’s name—also a folk singer—on a promotional poster. Other issues may well linger below the surface, but this is the moment at which Francis snaps. He goes off in search of himself and what Beethoven & Dinosaurs describes as “a multidimensional journey to create his stage persona.” Drugs are involved, as are a number of hallucinations and psychedelic landscapes.

curious bits of dialogue

The Artful Escape of Francis Vendetti, like its protagonist, has yet to make its first full public showing. At present, Beethoven & Dinosaurs has only released a trailer and announced that the game will be going to Kickstarter on March 1, 2016. The trailer’s a pure delight, filled with stunning vistas, bright colour combinations, and curious bits of dialogue. It’s a lot to look forward to, but it’s also all just promise for now. This is the videogame equivalent of a poster announcing Francis Vendetti’s first concert. If it took a psychedelic trip through the woods to get to that first public appearance, that wouldn’t necessarily be the worst of outcomes, but here’s hoping the game proceeds more smoothly than its namesake.

You can find out more about The Artful Escape of Francis Vendetti on its website.

We watched Ubisoft’s 30-minute The Division short so you wouldn’t have to

When Assassin’s Creed II was released in 2009, it was accompanied by a 35-minute live-action YouTube miniseries titled Assassin’s Creed: Lineage. Low-budget, hokey, free-to-watch, and largely peripheral to the story of Assassin’s Creed II, the miniseries’ promotional nature was clear, but the sheer length and novelty of the project gave it a sort of “official fan film” charm that made it seem at the least harmless. It wasn’t revolutionary television by any means, but the glorified cosplay nature of the project made it difficult to stay mad at it. Seven years later, after a whole generation of live-action trailers, a Prince of Persia movie, and an upcoming Assassin’s Creed feature film, the same trick isn’t nearly as cute.

Released on January 19th to Amazon Prime subscribers, Tom Clancy’s The Division: Agent Origins is a 30-minute prelude to the upcoming game The Division that spends about five minutes setting up the game and 25 minutes patting its audience on the back.

Wrapped in J.J. Abrams’ “mystery box” concept, Agent Origins strives hard not to spoil anything about the soon to release game upon which it is based. The most we learn is that it’s about a group of secret government operatives called the Division who are trying to restore order to New York City in the wake of a virus attack by an unknown, gas-mask wearing faction. We already knew this. But what works for a two minute Star Wars trailer doesn’t translate over to a 30-minute miniature movie. While it is spoiler free, most of the short fails to expand on the premise introduced in its opening, leaving about 80 percent of its content as contextless filler.

Compare this with Assassin’s Creed: Lineage, which follows Giovanni Auditore (father of game protagonist Ezio Auditore) as he unravels the Borgia conspiracy his son would later deal with in Assassin’s Creed II, and sets up the circumstances that lead to his capture in the beginning of the game. Agent Origins feels noticeably lighter. While Lineage’s plot still doesn’t spoil the game, it manages to tell a clear, self-contained story of its own that follows a well-defined lead character, and is therefore satisfying on its own accord.

contextless filler

Meanwhile, characters in Agent Origins are loosely defined. If this short, as the title implies, is supposed to tell me who these people are, it gives me little reason to care about them or understanding of how they relate to their world. Rather, each member of the Division could easily be a next door neighbor or someone equally innocuous. Which, to the short’s credit, is kind of the point.

During a brief scene towards the beginning of the short where a conspiracy theorist explains how the Division works, he makes it clear that Division members could be anyone, even himself or his buddies in the room with him. His group of friends share a very down-to-earth, jokey relationship that practically screams “This is you, audience!” at viewers. This is no accident, as Ubisoft teamed up with YouTube favorites RocketJump to help make Agent Origins. Predictably, the scene ends with one of his friends revealing herself to have been a Division member the whole time as she defends her group from looters.

This “hero all along” twist feels distinctly born out of the artifice of the role players will carry out in the game version of The Division, and it’s here that Agent Origins starts to show its more conniving nature. Despite being highly competent government agents, the members of the Division are fairly unremarkable people, carrying themselves with the casual, good-natured vibe of a group of friends shooting the shit rather than trained spec ops forces trying to save the world. They feel less like the people we’re told they are and more like supremely competent yet relatable hero costumes that players can look forward to putting on once they finally get the game. These are drop-in, drop-out superheroes made to fit the co-op, part time heroics The Division promises its players.

In short: it’s a dramafied Xbox Live. In 2005, Microsoft released an Xbox Live commercial where people are going about their day before an impromptu pretend shootout pops up around them after a single person holds someone else at pretend gunpoint. The ad was quickly pulled, but this is the same fantasy being sold by both The Division the game and Agent Origins the short. That you and all of your friends are secret badasses just waiting to be selected to save the world. This fantasy may hold value when explored through play, but when turned into a non-interactive marketing stunt, it fails to come across as anything other than Ubisoft complimenting its audience for how secretly cool they are before selling them a product that will allow them to make good on that promise. If Assassin’s Creed: Lineage felt commercial yet harmless, then Agent Origins feels manipulative in how it seeks to inflate its viewers ego all while selling their own identity back to them for a profit.

If you don’t have Amazon Prime, you can also watch the short as a series of four vignettes over on YouTube, albeit with some missing footage.

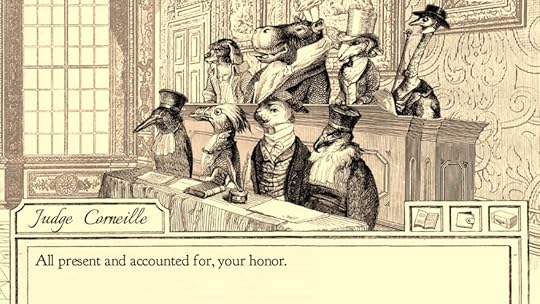

Aviary Attorney does justice to employed cartoon animals everywhere

That crows can use adaptable tools or that pigeons possess facial recognition should only surprise the doubtful. Birds have always held a knack for observation, logic, even deduction. But I don’t need science’s testament or anecdotal evidence to reinforce the intelligence of our airborne confidants. I have always known that “birdbrain” was a misconstrued insult, even if a number of them have tried to eat me in the past. I have known these things as I, a mere cartoon frog who reviews videogames, have always recognized and been inspired by the remarkable legacy of Jayjay Falcon, the 19th century bird who wore a tiny hat and was also a lawyer.

While Jayjay may have been a legal representative of the past, you are now in Killbert the Kill Screen Fun Frog’s court. I am the judge. I am the jury. I am the executioner. I am the fun-haver. I will put down the gavel on whether or not this game is fun, so press on. (Spoiler alert: it’s pretty fun!)

Brought to life through the animated portraits of 19th century artist Jean-Jacques Grandville, Aviary Attorney is a visual novel sipped through a Gilliam straw. Recounting the sordid adventures of one feathered public defender, Jayjay weaves the cases of kitty cat socialites, reptilian low-lifes and those that fall in between. All the while, the animals prepare a boiling revolution against the elites within the Parisian streets. Comparable to a famous book, maybe, though none come to mind.

Yet, there is one fun videogame this historical adaptation brings to mind: Phoenix Wright! Capcom’s wacky colorful series about various murder trials, the Ace Attorney games have set a standard for courtroom fun. Golly, it even set the standard for bird roles in the videogame court. But as fun as those games are—and they are fun (and I love fun)—they did leave room for improvement. Making progress often meant having to push along a narrative invisible to first-time players, meaning that puzzles and evidence, deductive reasoning, weren’t prioritized over unforeseeable dramatic twists. Is that fun? It is fun. But I believe it could have been more fun. To criticize Aviary Attorney, the more literal Phoenix Wright, means to launch off a criticism of Ace Attorney, as this game manages to weave around those trappings while stumbling into newer, comparable ones.

a visual novel sipped through a Gilliam straw

Time is of the essence my dear Watson (I am going for a fun mystery motif here, see?), and so time is a value in this bird game. Between taking the case and making them, you must gather evidence and testimonies across barnyard Paris, each site of intrigue taking up 24 hours of your time. However, on multiple occasions the calendar is a ruse: Jayjay and associates are flanked by story developments that knock you out cold, advancing toward the court date without warning. When this happens, you’ll suddenly feel unprepared when you previously thought you had all the time in the world, sort of like when I rent too many fun videogames for the long weekend.

When you are fully prepped for the trials they feel like a breeze. Aviary Attorney is much easier than Ace, regardless of fastballs, but they are on par for entertaining dialogue and charismatic animatics. Though having a fellow frog as the first victim, well, that took some time to process (poor, poor Monsieur Grenwee, I will leave flowers on your grave).

But, more than anything else, I am glad that one of the key chapters in animal-employment history is being recounted in such a fun way. Without Jayjay Falcon’s worthy service in the court, we’d be looking at a much different world. We wouldn’t have the bird opportunities, dodo lawyers, jury stands full of screaming parrots, or owl judges in amazing teeny powdered wigs and officiary gowns. When I was a younger frog, Jayjay inspired me, maybe I, Killbert the Fun Frog, could represent the innocent or the oppressed in the court of law, perhaps aid in actuary or immigration. But that was, of course, before I discovered fun videogames, and found my true destiny.

Besides, they do not allow frogs in court. That is a fight for another day. And perhaps, oh, perhaps, they’ll make a fun videogame about the amphibian hero who changes that. We, my fellow frogs, are more than Battletoads, brawling in the arena for your sickening amusement.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Where painting and videogames collide

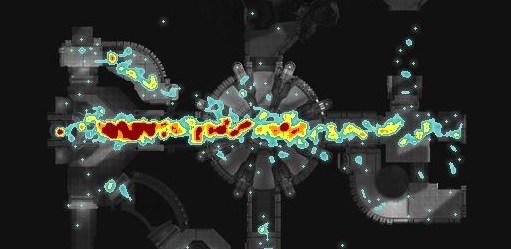

If someone refuses to paint, all you need to do to fix that is strap tubes of the stuff to the soles of their shoes and send a couple of angry dobermans after them. Don’t question why you’d ever be so desperate to get someone to paint that you’d resort to this admittedly drastic method. This is how art is made. At least, according to Splattershmup, that is: through peer pressure and, failing that, hostile encouragement.

In truth, Splattershmup isn’t as goofy as that (or its title) makes it sound. It’s an honest and successful attempt by Rochester Institute of Technology’s MAGIC Spell Studios at exploring the “intersection of the classic shoot-em-up (or ‘shmup’) arcade game and gesturalized abstraction or ‘action painting.'” This means that, as you’re steering a ship from a top-down perspective, shooting the enemy ships that rush you, you’re also actively painting. Your ship trails paint as you move it around the grey floor of the gamespace while dodging bullets. You occasionally get pick-ups that change the color of this paint. Once you die, you get to see the streaky composition you made in full, and can easily save it to your computer or share it on social media.

action painters have an “encounter” with the canvas

The comparison to action painting works as the painting side of the game is involuntary; a byproduct of playing the game. Your urgent concern isn’t what you’re painting but making sure your ship doesn’t eat a thousand bullets and blow up. The process of action painting itself is similar. It’s a term coined in 1952 by art critic Harold Rosenburg in his essay “The American Action Painters.” He applied the term when describing the works of abstract expressionists such as, most famously, Jackson Pollock. Rosenburg says the action painters have an “encounter” with the canvas, adding that, to them, it was “an arena in which to act.” These painters, according to Rosenburg, captured an immediate moment of emotion, letting paint drip and smear spontaneously, rather than sticking to the typical method of bringing a planned image to life with their brush.

You can see through the language that Rosenburg uses that the jump to turning action painting into a videogame isn’t a big one. The idea of it being an “arena” makes a direct connection to shmups in particular. They often confine you in a space and send waves of enemies for you to deal with, using fast-motion to avoid incoming fire—it’s a performance of skill. Action painting quite easily transfers to the shmup format.

But it’s worth noting that Splattershmup isn’t the only game to have explored this translation from painting to videogame. Ian MacLarty’s 2014 title Action Painting Pro used the format of a 2D platformer to recreate the process of action painting. In it, you moved a character around, leaping from platform-to-platform, the catch being that the platforms constantly shifted position. While doing this, the character leaked paint onto the backdrop of the gamespace, it running down the walls as a rainbow assortment.

Before even this, though, there were the Halo 3 heat maps back in 2007. These were overhead plans of the multiplayer maps of the first-person shooter that displayed data as blotches of color. This data included player deaths and kills around each map. If a certain spot was dark red it meant that it was a place of frequent death-dealing, while less busy areas were orange, yellow, green, or had no color at all. The idea was to use this visual data as a way to improve your tactics in-game but it also doubled up as an unusual means of collaborative action painting.

You can download a beta version of Splattershmup on its website.

Jonathan Blow’s Laboratory

A series of opaque circles flicker around a crudely rendered pool table like digital fireflies. As you choose your shot, a program simulates the aftermath, allowing brief insights into the future before you’ve even decided what to do. The game is Oracle Billiards, named after, and partly inspired by, a character from the Matrix. It’s a straightforward experiment based on a simple concept: how does seeing into a game’s future change how you play it?

Exploring the contours of that question proved difficult, however, and so the prototype was scrapped. Its creator, Jonathan Blow, had decided that the “billiard-balls-physics phenomenon was inherently too chaotic” for the line of questioning he was trying to pursue. The idea was to help players get inside the mindset of a pro by shifting the emphasis from technique and experience to strategy. The results were too messy. Being able to see the future turned out to be its own burden, at least in Oracle Billiards.

This sort of Icarian pattern runs through a lot of Blow’s earlier work. Questions are asked and experiments created that end up leading to small games which are as conceptually ambitious as they are structurally flawed.

Another of his prototypes, Painter, has players use a primitive set of graphics tools in order to create imitations of famous artworks and earn money for them based on how accurate they are. The feedback was mixed. The players who tested it at the time liked its meta-game of earning money for creating imitations. They also rated the potential to have different patrons with different aesthetic preferences that needed to be catered to. But the painting itself was tedious. What was interesting about the game’s core conceit failed to trickle down.

how does seeing into a game’s future change how you play it

Searching for this kind of continuity throughout a game’s systems has become a signature of Blow’s approach to game design. Fond of emphasizing the famous McLuhanism “the medium is the message,” Blow has spoken often about wanting to take the unique attributes of games and unify them around specific themes or ideas. Rather than let games simply be containers for the content of other mediums, like war films or science-fiction literature, his work can usually be seen as a struggle to convey human experiences in sub-verbal, sub-intellectual, deeply game-y ways.

Braid, Blow’s most famous and profitable game to date, is currently the most successful outcome of that project. Playing with recognizable game forms like platforming and collectibles, it nevertheless twisted them into something surprising, and in the end, deeply emotional. Nicewrench, an iteration on an early build of developer Messhof’s Flywrench, was another experiment of Blow’s from around the same time he was working on Braid. Written in two days, the idea was to see how making Flywrench less brutal would affect it. “How does the design change, and how do you keep the game interesting?” Blow wrote in the game notes.

Adding collectibles and eliminating death helped open the game up, making levels larger, more varied, and less conclusive. But while, in Blow’s words, “this prototype highlights some interesting gameplay situations that were not possible in Flywrench,” he felt movement in Nicewrench was too clumsy. It opened up different possibilities, but lacked interesting patterns of traversal to match them. The results were enlightening but incomplete.

it can feel possible to glimpse the vague outlines of the translation Blow was aiming for

“I’m not a very visual person,” said Blow in a recent interview with Gamasutra. “When I close my eyes and imagine things, there’s no picture whatsoever—there’s just ideas.” Perhaps nowhere is that more evident than in one of his earliest prototypes, Raspberry. “The original idea was to try and explore the way music can induce emotion,” explains Blow in the game’s readme file.

To do this, the game is split up into a number of different modes which continuously segue into one another as time moves on. One mode, for example, requires the player to accrue points by matching nodes of the same color while penalizing them if they drag the cursor over a different color in the process. Another treats the cursor like a balloon, constricted only by the borders of the frame and the particles buzzing around within it. More time spent allowing the cursor to expand in the gaps created is rewarded, while players lose points for any time spent where the cursor is contracting.

The rules are complex enough that Blow himself narrates them in the game’s tutorial. The resulting designs are bracingly minimalist, at times bumbling and slight, at others nearly harmonious. In the midst of a long play session, it can feel possible to glimpse the vague outlines of the translation Blow was aiming for with it. Asking what a song would be like if it were a game may be a quixotic goal, like asking how a sound would taste if it had flavor, but the motivation behind it, at least in Blow’s case, remains a deeply practical one.

Even with Oracle Billiards, the gaps between the idea and its execution, both visually and programmatically, yielded a moment of relief. “You can visualize the collision in your head,” wrote Blow. “But what you envision doesn’t necessarily put the balls where it says they will go. But then the collision happens, and they go right there. It feels pretty surreal.”

This friction between imagination and simulation remains a focal point throughout Blow’s work. Perhaps this is partly because of its aspiration to move beyond systems of rules governed by difficulty, risk, and reward. It’s a goal that seems inextricable from his un-visualized approach to design. It in these spaces, between the idea in theory and how it works and looks in practice, that Blow’s experiments have yielded their most interesting results.

In many ways, The Witness—Blow’s seven years in-the-making follow-up to Braid—is the culmination of this process. Born out of a prototyping phase in 2008, the game seems intended to recreate the sames struggles associated with experimental game design. “The game is designed to create many opportunities for epiphany moments, both small and large,” Blow told Gamasutra. The puzzles aren’t “arbitrary,” structured as scenarios for reward and punishment meant to string the player along. Instead they’re more intimate, a mirror into the same exploratory process that made the game possible in the first place.

January 21, 2016

It’s all cults and charming co-workers in Knuckle Sandwich’s new trailer

A shitty job is a rite of passage. You move away from home, maybe go to college, and get a lame job to pay all those pesky bills and rent. Juggling the taxing reality of ten-page essays and “clopening shifts” (in which you work a closing and opening shift… in a row) becomes second nature. Your colleagues often become the confidants you so desperately need, the voids for bemoaning the woes of being a young, broke, and most of all bored adult.

Such is the theme of Knuckle Sandwich, the latest in a recent slew of quirky JRPG-inspired games, this time developed by Australian developer Andrew Brophy. In Knuckle Sandwich, the mundanity of everyday life within the RPG is the Persona-esque twist to set it apart. In a new trailer, the unassuming protagonist’s co-workers—and potential adventure companions—are introduced in full force. There’s the raven-haired and talkative Echo, rosy-cheeked Thea, and the awkward bespectacled lone boy of the trio: Dolus. All three equipped with showing the new kid around town, and reassuring his insecurities of finding things to do, even if he’s stuck in a dead end job.

With moving to a new to city and passing time with a mundane job at a rundown diner, life in the aptly named Bright City can seem, well, not so bright. To add to it, Bright City is the recent host to numerous dark horrors: people are going missing, eerie cults potentially behind it, and here is the new citizen, stuck right in the middle of it, whether he likes it or not.

psychedelic-visualized turn-based battles

With the introduction to more characters, Knuckle Sandwich’s latest trailer also shows a bit more of what players can expect. As the player traverses the colorful environments of Bright City (boasted as “hella pleasant” by Brophy himself), soundtracked to the delightful Super Nintendo-inspired score by composer Gyms. From its puppy-less Puppy Shops to its indiscernible dialogue (think Okami meets Simlish) and psychedelic-visualized turn-based battles, Knuckle Sandwich is a personality-driven RPG, with autobiographical qualities to boot. Recently greenlit on Steam this past autumn, the game is still without an official release date.

Follow development of Knuckle Sandwich on Brophy’s frequently updated devlog or website .

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers