Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 169

January 29, 2016

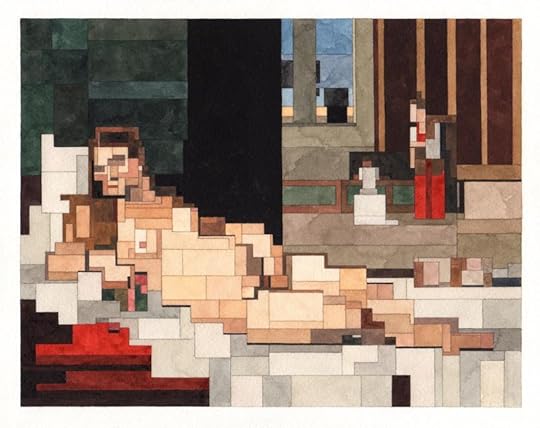

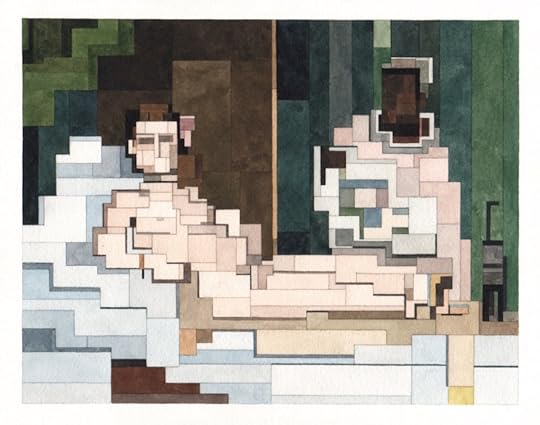

Fine art gets an 8-bit inspired make-over

Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was rejected by the Paris Salon when he submitted it in 1863. In fact, so may paintings were rejected that year that the Emperor Napoleon III decided to create the alternative event where these works could be seen and judged by the public at large. This “Salon of the Refused,” despite including the now historic work of Manet and others, was treated more like a freakshow of aesthetics than a showcase of France’s avant-garde.

The public’s mockery of Manet’s paintings was ongoing, as were allusions in his work to the prostitution scene in late nineteenth century Paris. Perhaps the inspiration he drew from past masters only added to the perceived insult of these works. Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, for instance, shows connections to Giorgione’s The Tempest and Titian’ The Pastoral Concert from the early sixteenth century. By taking the nude figures out of their allegorical context and instead situating them in the contemporary setting of a picnic in the park, Manet’s piece was as scandalous as it was modern. It spoke to his present moment not by ignoring the past but by scrambling and re-deploying it.

Adam Lister’s re-imaginings of Manet and other artists’ work operates in a similar, if less controversial, manner. While often praised for their 80s and 90s, early videogame aesthetic, recalling the days of the Atari and NES, Lister prefers a more expansive view of his paintings. “I would describe my paintings as geometric deconstructions,” he says. “They are not 8-bit, but I would say they are ‘8-bit inspired.’”

a sea of lines, tones and corners

His version of Titian’s Venus of Urbino draws a particularly interesting contrast with the original. Reconstituting Titian’s soft curves and warm blending of oil pigments with angular swabs of watercolors has a flattening effect that re-orients the viewer’s gaze to the figures in the background. A lump of browns and whites at the foot of the bed provides compositional balance but in no ways resembles the sleeping dog in Titian’s original, nor does it have its semiotic value.

Manet’s Olympia in many ways also plays off the Venus of Urbino while also being inspired by it. Another shocking display for its time, the harshness and realism of Manet’s lounging nude was considered vulgar, an affront to the idealized representations of the paintings it borrowed from. Lister’s version of Olympia seems to reveal an even plainer subject. Dissolved into a sea of lines, tones and corners, the model feels somehow more disdainful towards the viewer’s gaze. A vertical line cutting down the middle looks even less like a structure in the room than a division between Parisian woman and her servant.

This sort of balancing act is central to his work, Lister says. “As a painting progresses, I try to keep a balance between making a visually simple picture and highlighting the complexities of the original subject matter.” Partly he sees his role as being a translator, turning one form into another by way of a geometric language he can use to visually describe something.

In this way, he considers his interpretations each the result of a process that strives to break down the originals into their key ideas and visual components. As he told The Creators Project, “I’m paying special attention to the subtleties in color and the handling of each composition.” It’s process not unlike trying to decipher an old code, he explained. The re-coding that follows thus provides not so much an 8-bit remix of the original work as a geometric excavation of the visual principles animating it.

Shut Up, Gaming Positivity

This article is part of a series called Shut Up, Videogames, in which critic Ed Smith invites games old and new to pipe down, or otherwise. In this edition, he looks at today’s atmosphere of “gaming positivity” in games criticism.

Rather than challenged by the emergence of different games and different creative voices, I feel like the culture of blithe acceptance in the gaming industry has simply widened. Old reviews of shooters and sequels, scaffolded by a checklist of “graphics, gameplay, replay value,” are today lampooned even by the big sites—I think anyone with the sense to not leave comments on things they read on the internet understands that gaming criticism, for a long time, was simplistic and toothless. But still I find myself wincing at the superlatives and hyperbole that I and others have used to describe games, even in articles I’ve written in recent months. Still I see a paradigm—a mental model—of championing games beyond all reason, in the hope their false glory will reflect back to us, the critics, a sense of validation.

we’ve decided that it’s over now, that games have made it, that they’ve arrived

We want games to be creatively, artistically successful. If they are, we celebrate and fawn over them to nauseating extent. If they’re not—if some slight, twee, whimsical independent game has very little to say but at least looks nice, and makes us feel slightly warm inside, if even for a minute—we’ll insist it has credibility. Games sell more than music or films. Games attract talent from the world of cinema. Games can tell stories about adult things that will make you cry—we swear to God. The author is dead and there’s nothing I love to read (or write) more than a weighty, evidenced alternate interpretation of a scoffed at AAA videogame. But I sense, today, there’s an atmosphere of “gaming positivity.” It’s a dream shared among developers and critics for gaming to be wonderful, smart, happy and successful—a willingness to force smiles and wave flags, even though it’s not helping.

Gaming positivity isn’t bad. In a culture besieged by sexism, consumers and retrograde politics of all kinds, it’s healthy to remind ourselves—even if it takes a little blurring of our vision—that games are worth something, that we do our jobs, as writers or game-makers, for a reward additional to our salaries. It’s nice to be nice. And if a game contradicts our tiny, backward culture, and also makes it to sale, I consider that a small miracle. But the desperate, cloying praised lathered on froth like Her Story (2015); the laughable earnestness of the Emotional Game Awards; the shaky insistence, in articles and at presentations, that games can change your life. It seems like, as an industry, as a collective, as a whatever, we’ve decided that it’s over now, that games have made it, that they’ve arrived. Papo & Yo (2012) is art. The Vanishing of Ethan Carter (2014) is art. Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons (2013) is art. And if people don’t agree or don’t realize, it’s their fault, and we have the affected sincerity of a thousand editorials to prove ourselves right.

But whatever “it” is, games are miles off. In fact, there is no “it”—there is no objective finishing line over which games have crossed, or ever can cross. My problem with gaming positivity—this constant insinuation either tacit or direct that games are “better” than they once were—is that it assumes an end state, some kind of final evolutionary stage whereby artists and critics can rest easy. The spirit of blithe acceptance lives on in gaming positivity, only now disguised behind more sophisticated language. A smug, self-satisfaction has descended onto games. We have an independent scene, some slightly smarter mainstream releases and a game where you can play as a petal, and with that we seem satisfied. The tragedy, however, is that a lot of the truly great writing and games currently being published are being overlooked in favor of work that better suits a chirpy, videogame-positive zeitgeist.

But whatever “it” is, games are miles off

I find it frustrating that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015), because it’s inoffensive and beautified and unambiguously “emotional,” is a more recognized marker of gaming’s current state than Off-Peak (2015), or Actual Sunlight (2013). I find it troubling that, in search of games and images that can be easily used to sell the idea that games are artistically valuable or emotionally… something, critics, developers, and the industry at large passes over genuine creatives. It’s not the caustic, penetrating work of Cosmo D that gets nominated for BAFTAs, but the showy, wholesome output of The Astronauts and The Chinese Room. Gaming positivity latches onto the easiest sells and the simplest pleasures and then tells us games are either going somewhere or, even worse, have already arrived. But videogames are not a person, a friend or an extension of ourselves—their success isn’t, or shouldn’t be, our gratification. And a consensus that games are “better now” has the same effect as those febrile reviews from back in the 90s, the ones we so smugly like to mock: it leads to a cultural vacuum, an unwillingness to create and a moratorium on change.

January 28, 2016

Virtual Drag, or how to queer virtual reality

“We’re born naked, and the rest is drag.” – Ru Paul, Lettin’ It All Hang Out, 1995

///

Australian digital media artist Alison Bennett says that Virtual Drag came to her “like a bright flash.” It may not seem obvious at first, the connection between drag performance and virtual reality, but once the two concepts merge in your head your thoughts can start to accelerate down a rabbit hole of vast questions and possibilities.

Before getting to the larger implications you must first know what Virtual Drag is all about. It’s an exhibition that will see 3D scans of drag queens and kings displayed on virtual reality headsets from February 1st through February 7th in the Studio at Testing Grounds, located in Southbank, Melbourne. It’ll also be realized as a gigantic projection on the side of an adjacent building during a free after-dark event on February 5th.

Virtual Drag is a feast of images.

Bennett teamed up with choreographer and 3D animator Megan Beckwith, and award-winning designer and photogrammetry artist Mark Payne for the technical side of Virtual Drag, all with the funding and support of the Australia Council for the Arts and Deakin Motion.Lab. Posed on the other side of the project’s lens are drag queens Philmah Bocks, Art Simone, Jackie Hammer, as well as the Transylvanian Gypsy Kings.

Visually, Virtual Drag is a feast of images. The main promo art implies the multiplicity of a drag queen’s face through an almost horrific 3D display; multiple skins and blotches of make-up layered in such a way that they appear to smear into each other, pink hair and digital shrapnel almost like a glittery representation of gore. Alone, it’s striking, but it is even more so if you see all the discourse it meshes together.

Virtual reality and drag performance intersect in how they challenge the concepts at their core. We can say that virtual reality destabilizes our notion of reality by recreating it in such a way that it can be difficult to discern the original from the copy. In this way, the question at the heart of virtual reality is: “What happens when we can’t get out?” Suppose that the simulation of reality gets so far that, one day, it’s possible to feel like we’ve removed the VR helmet and presumed to have returned to reality, not knowing that actually the helmet still shrouds our eyes. This confusion of reality and the non-real is arguably what drives our curiosity in advancing virtual reality—when the verisimilitude becomes indistinguishable. What’s important here is the idea that what we consider to be the ‘original’ reality might be proven to be faked, or at least questionable. This has been considered in philosophical thought for millennia, as far back the 5th century BC, when Plato contemplated the separate states of dreaming and non-dreaming, but the rise of virtual reality has accelerated this “what is real?” question in the public consciousness in recent years.

brings attention the hyperreal surface of the video

To explain how this theory of virtual reality relates to drag performance, Bennet calls upon gender theorist Judith Butler. In her 1990 essay “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” Butler explicates what drag performance achieves through its deconstruction of genders and how they are represented and identified. In short, she concludes that drag implies that there is no original expression of gender, that it is informed by our social realities: “compulsory heterosexual identities, those ontologically consolidated phantasm of ‘man’ and ‘woman,’ are theatrically produced effects that posture as grounds, origins, the normative measure of the real.”

In both, the notion of ‘realness’ is brought into question—quite simply, what we accept to be real, shown to be a construction of human making. And so, by bringing drag queens and kings into virtual reality, Virtual Drag doubles their implications, letting their deconstructions overlap in an astonishing synergy. It brings into question the mainline pursuits of many other virtual reality projects as of late, too. “So much of the early work in virtual reality has been driven by naked girls presented for a male gaze,” Bennett says. And she’s right, with pornography being big in virtual reality right now, squeezable breast peripherals and penis-controlled masturbation controllers were among the first devices developed for the Oculus Rift. What Bennett hopes to do with Virtual Drag is to contribute to the ‘queering’ of virtual reality.

Queering virtual reality is also a layered concept. Not only does it mean bringing queer bodies into virtuality, it can also refer to a more direct disruption of the medium of virtual reality. You can see this might be done in the 30-second trailer for Virtual Drag (as seen above). Notice how it incorporates the visual effects associated with a corrupt VHS tape such as banding, scratches, and noise. This brings attention the hyperreal surface of the video—the distance between the virtual space and the one we occupy—deliberately preventing us from fully engrossing ourselves in its verisimilitude. This barrier is exactly what most virtual reality projects so readily attempt to make disappear. And so by queering virtual reality, Bennett not only challenges the performances we enact in our perceived reality (such as gender), and that we then bring to virtual reality, she also challenges the primary use of virtual reality as a simulated performance of the real.

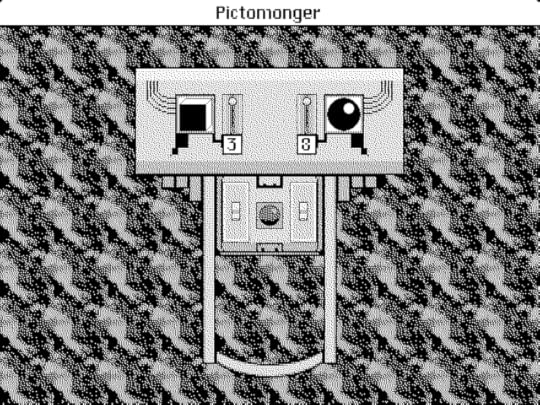

Corporate hell as seen through a 1980s operating system

Imagine a purgatory for the beleaguered office worker. It is probably a world of endless (or, to misuse the term to constructive ends, more endless) meetings and water cooler chat. Fair enough: That is what office culture and the cultural portrayals thereof have conditioned us to expect. But what if this purgatory was something else entirely, a strange liminal space whose only connection to office life is the skin of operating systems past?

This possibility is the central conceit of Wince Nail, a game originally created by CYBEReris for the Myst Jam. The game, which is currently available in demo form, tells the story of a worker who, as punishment for his indiscretions, finds himself in corporate purgatory. Unbeknownst to our protagonist, his employer, Corporeal Industries, created a liminal place to stash intransigent underlings. It started as an outsourcing facility, but corporations are prone to mission creep and now it’s a prison masquerading as a vacation spot.

Wince Nail is both a literal and figurative black box

Wince Nail is, in a sense, a very traditional vision of corporate hell. The game’s aesthetic is straight out the original 1984 Mac operating system. It is the kind of thing one joylessly employs. It is also a conceivable outgrowth of corporate IT practices. Wince Nail is not really going for verisimilitude, but its alternate universe is sufficiently plausible.

In that respect, Wince Nail is what you’d get if you stretched the internal logic of a Dilbert strip until you were looking at a Black Mirror episode. Its world is both distinctly fictional and entirely plausible, the product of decisions that would be understandable in isolation though not in their totality. The purgatory in which our protagonist finds himself is apparently only known to the company, but its existence still raises the question of what sort of society out of which such an idea might emerge. Wince Nail is both a literal and figurative black box in that respect. There is no world outside of Corporeal Industries’ confines, no indication of where the game fits into a broader society. If nothing else, that offers the comfort of not having to think of how Wince Nail’s world might relate to ours.

Pop, politics, and everything in between: the virtual families of netlabels

It’s approximately 7 p.m. on a Monday night in California, and across from me sits the bleach-haired Zeon Gomez of Ulzzang Pistol, an artist of Los Angeles-based netlabel Zoom Lens. Yet for Gomez, it’s 11 a.m. on a Tuesday. He resides across the world from my foggy little city in the United States, approximately 16 hours ahead in the Philippines (Manila, specifically). Dividing us is an extremely common window: a computer screen. The household item not only used for the sake of hosting our lengthy conversation over Google Hangouts, but a tool for maintaining friendships across countries and oceans, discovering inspirations in unexpected places, and releasing art into the boundless void of the web—in Gomez’s case, music. Without the Internet, we wouldn’t be having this conversation, and more than that, Gomez’s music wouldn’t even exist.

Netlabels, by simple definition, are online labels that distribute their music largely online, either through websites like Bandcamp, Soundcloud, or via their own (often free) downloadable means. Typically helmed by one or two people, netlabels have a set roster of artists on their sites, in addition to co-signing releases through the label (in some cases, it’s only cosigned releases). To be clear, using the Internet to promote and distribute music is nothing new. In the early aughts, the popularity of French house label Ed Banger Records grew steadily—largely thanks to artists’ profiles on social network sites like Myspace. This resulted in electro-rapper Uffie’s quick rise to fame, as well as the success of labelmates Justice and Mr. Oizo. Where Ed Banger used social media to market their music, netlabels emerged in a fashion that was more borne of the Internet itself. With tunes not as polished as something like Justice, netlabels cultivated a new form of pop and dance music for the DIY, laptop-enabled crowd. In an era where being an independent artist changed from peddling mixtapes in dingy bars to hustling free albums on Bandcamp, netlabels evolved at lightning speed.

Conservatism and the right to dance

Japan is a country dominated by its own sugar-coated, highly manufactured brand of idol pop music (colloquially referred to as J-Pop). Japanese netlabels arose in the mid-aughts as a new youth-based counterculture in rebellion against the highly conservative Japanese music industry, which essentially exists in a ‘nothing is a free or unmanaged’ vacuum of corporate culture. Netlabels such as Maltine Records emerged with the idea of pushing past this stuffy mantra. By distributing their eclectic circles of pop, dance, and hip-hop for free, netlabels forged a means of expression and rebellion against something major labels would frankly never allow their artists to do. For largely the first time, underground musicians were given the voices and agency they so desperately desired.

Netlabels cultivated a new form of pop and dance music for the DIY, laptop-enabled crowd

The first Japanese netlabel was 2003’s Minus N, which wasn’t nearly as powerful or successful as the leagues of netlabels that came in its wake. Despite its counterculture roots, netlabels aren’t an attack on J-Pop. In a lot of instances, netlabels embrace the genre’s bubblegum-tinged sound, and some netlabel artists even lend a helping hand to up-and-coming J-Pop artists. Maltine Records, established in 2005, remains the most prominent in the Japanese netlabel scene alongside Bunkai-kei Records. Its scope of releases expands beyond Japan to artists from London to Melbourne, just as Minus N’s did.

Across the board, netlabels are mainly seen as purveyors of electronic music, but the reality is more complex. Smaller netlabel Ano(t)raks is a rarity in itself. Instead of pushing its weight behind electronic music, indie pop-rock is at the forefront. For Maltine Records, the label’s overall subgenre is not clearly defined—leaving freedom for anything, really. For instance, city pop-inspired musician bo en’s affinity for Maltine’s artists and various videogame soundtracks gave him the agency to feel that “‘real music’ didn’t have to be boring, you can be a serious and studious artist working in these playful formats.” Contemporary dance netlabel Trekkie Trax’s strong camaraderie of underground DJs actively fought against Japan’s late-night clubbing laws. Under the law, you could not dance in a nightclub if it did not bare a “dancing license,” a point of contention for the young proctors of dance music until the law was eradicated in 2015.

Japanese netlabels, in short, give artists the freedom to create whatever they damn well please. This is especially welcome in a music scene where cookie-cutter idol groups are common, and diversity among their style is rare (except for the joyous “indie” idol groups Negicco and Especia, or the frenetic subgenre of denpa idol groups). Where Japanese netlabels paved the way for web innovation, some Western netlabels surface and readjust the scene in new, peculiar ways.

A “Friends First Mentality”

The Western netlabel scene is technically older than Japan’s, but is far less defined in terms of an actual, tangible community. In the States, there hardly seems to be a place for grandiose roster-wide celebrations, or subterranean bass-heavy parties, as there are in Japan. What’s different in two notable Western-based netlabels, however, are the pockets of communities that thrive within them, and their varied inspirations for running a netlabel within a highly congested net-music climate.

According to co-founders Devin Miski and Noah Hafford of California-based netlabel/collective Galaxy Swim Team (GST), a “friends first mentality” is essential. Before GST’s inception, the two admired netlabels from afar but never felt welcomed themselves within the community. So Miski and Hafford came to the conclusion of simply starting their own web-based home. The result is the unwavering support that permeates throughout GST’s roster of pals. Perusing the small roster of artists, GST is full of the glee of pop-enthused youth. The music itself is rough around the edges, but heartfelt and earnest—part of its charm. “For me especially, all my other music is so brooding and negative and noisy,” said Miski. “So I specifically like to make the music I make for GST as something that balances it out. I feel like GST for a lot of us is the positive balance in our lives.”

Miski grew up in San Jose, California’s DIY punk scene, a music community he never felt a deep connection with, despite bouncing from band to band since he was 15-years-old. Hafford’s only experience with any music scene has been to admire netlabels from his home in Pennsylvania. (He has since relocated to California). While the netlabels Hafford admired are older and more established, Miski and Hafford’s GST is fresh off the web, founded in January 2015.

In their first year as a netlabel, GST have released a slew of online releases, notably all for free to download (and plan to do “twice as many” in the coming year). They played a showcase at South by Southwest in Texas, as well as various other shows. The casual experiences shared among GST’s artists, ranging from prolific 4Loko drinking to heated arguments over Wendy’s, showcase that at the crux of it, music is just the bread for this particular netlabel/collective, with everything else stuffed in between. Through the music crafted, shared interests and private Twitters, the “feeling of just wanting to spend the entire night with your friends, playing a PS2 game and laughing at all the things that got lost in 2002,” GST illustrate that they didn’t just create a family through the netlabel, they already happened to be one. “I feel that that’s really important, when you’re brought together by more things than are just art,” said Hafford. “Beyond just music.”

“Blank Ocean”—A Worldwide Perspective

If freshmen netlabel Galaxy Swim Team are the jubilant side of Western netlabels, then Los Angeles-based Zoom Lens illuminate the grimmer, sad sect of the scene. For Zoom Lens founder Garrett Yim, a broader perspective beyond the Western hemisphere to the net music scene is most important. Zoom Lens, founded in 2009, has grown exponentially during its short lifespan, and continues to develop and widen its scope. With collaborative releases and even shared artists with Maltine, the two labels at the same time reflect one another, and yet shine very differently. Yim, a passionate curator for diversity in independently produced music, praised the local community that Maltine’s created in Japan. “I just saw a reflection of what I wanted to represent,” said Yim. “In that the Internet is simply a tool to be used to reach a community and to form a language to a world beyond our grasp.” The Internet as a means, not an end.

For Maltine, a specific aesthetic doesn’t really exist—it’s more a jumbled beacon for notable underground electronic, pop, and hip-hop in Japan and elsewhere. If there’s a throughline, it’s giving voice to Japan’s unknown (or, due to occasional major success, formerly unknown). For Zoom Lens, though, Yim’s goal is even grander: a community unified by commonality in feeling and ideology, music that’s not afraid to talk about the depressing side of life, while staying true to the nature of pop music. Yim abstains from even using the term “netlabel,” instead settling on the decisive “Zoom Lens community.”

In addition to being the founder, creative director, designer, and manager of Zoom Lens, Yim pours his efforts into his current music project, MEISHI SMILE, whose sound straddles the line between pop and noise. Yim started Zoom Lens during a time when he began to feel at odds with his place in the experimental and noise music scene. “The way I saw people consume noise music and the exploitation of niche, limited releases felt the same as the idolization and worship of pop artists,” said Yim of his experience in former project Yuko Imada. “People’s reactions and affinity with music and art are always the same, no matter the genre explored.”

The overall feel of Zoom Lens music, then, is bleak. The burned face of deceased eighties J-Pop idol Yukiko Okada is seen across products (in Yim’s effort to familiarize people with the pain Okada suffered in her life before her suicide, the burn mark as a ‘mask’). Every Zoom Lens release features dark, personal experiences funneled into “lighter” music. This contrast has wrought accusations of being “violent” and “negative,” though Yim always defends their collective creative decisions.

Zoom Lens differs from other blossoming Western netlabels in many ways, mostly in that its artists operate on a global scale, from Singapore’s Yeule to Manila’s Ulzzang Pistol to Japan’s LLLL. Its genres aren’t as cut and dry—much like MEISHI SMILE’s sound itself. This duality of sound and community is important to Zoom Lens’ approach. Yim recalled a conversation with the netlabel musician Gus Lobban, when someone told Lobban after a show, “What you did tonight was very brave, creating pop music.” For Yim, this raised the question, “When did pop music become brave?”

In Savannah, Georgia, Zoom Lens artist la pumpkin said that she was attracted to the label’s emotional sincerity and the lack of catering to a “trendy sound.” In Singapore, artist Yeule feels as if her quieter, ambient music differs strongly from that of the grander Singapore music scene (noting the local prominent hip-hop community). Personally inspired by her father’s jazz music and David Bowie, Yeule is content with the ambiguity of Zoom Lens. “I don’t think we’ll ever ‘fit’ into a scene,” said Yeule. “We are all merely just floating around and having a great time connecting with others through music.”

“When did pop music become brave?”

For Zeon Gomez of Ulzzang Pistol, his dreamy, pop-inspired house music relishes in its pan-Asian roots. Across his Ulzzang releases to date, Gomez has sung in English, Japanese, Korean, and most recently Tagalog; his native tongue. This is in addition to varied collaborations with artists from all around the globe, including Kero Kero Bonito’s Sarah Perry from London and the far lesser-known vocalists Yikii from China and Oh Hee Jung from Korea.

Gomez is hesitant to conform to a single genre, especially as he’s growing up and maturing, his music along with it. Where Gomez’s full-length Girlfriend was borne out of heartbreak, his future releases have formulated through a stronger sense of cohesion. His influences range from Korean golf MMO PanYa (“There wasn’t anything special about the game. I was there because I enjoyed talking, as much as I wasn’t so good at talking to people in real life”) to the diverse sounds of J-Pop, K-Pop, and C-Pop. A goal of Gomez’s music is simple: to make people feel good about themselves. He judges his success in this by the waves of beauty videos on YouTube using his music as a backing track. In Gomez’s experience, when someone’s getting ready to go out, they play a song to make themselves feel good. That’s what beauty vloggers do with his music. “Which is kind of shallow, but the instrumentals, that’s what they’re about,” said Gomez. “That’s why I’m still very keen on how music makes you feel.” His gravitation towards Zoom Lens evolved from an appreciation and friendship with its founder, Yim, and the two remain close today, despite living across the world from one another.

“Fuck Real Life”

The Soundcloud-universe of Western net music is filled to the brim with high-pitched twee and archaic Yoshi samples. This is fun, but creates a set of expectations that netlabels themselves fight to crash through. Zoom Lens mantra “Fuck Real Life,” attempts to counteract that. “It’s about being your own and going against this idea of what is ‘real’ and what is not,” said Yim. “It goes against the prefabricated notion that certain things need to fit in a box and cannot co-exist with each other, just like pop and noise music.”

Subcultures are nothing new. The media theorist Dick Hebdige has written about how as generational consciousnesses arose after World War 2, subcultures like mods, punks, and reggae emerging to help deal with the claustrophobia of reality. All of which is to say that it’s important to contextualize such subcultures with the society they existed in. Netlabels would not exist without a generation of middle-to-lower-class kids growing up with the Internet, and the simplicity of its accessibility—a pure symptom of the digital-age. It may eventually fizzle out, as did other niche subcultures of the past—but that’s okay. Right now, netlabels are an anomaly in the subculture space, one that isn’t strictly defined by any sole aestheticized surface but a thread that varies wildly with each label. It’s instead the pockets of diverse communities that drive netlabels. Whether through the shared ideology and duality of sound spanning across seas in Zoom Lens’ global approach, the cemented long-term friendships in Galaxy Swim Team, the diverse power of Maltine’s releases, or the passionate activism-fueled fight for the right to dance in Tokyo clubs by Trekkie Trax—that’s the forefront. The aesthetic is an afterthought.

///

During our long-distance chat, Ulzzang Pistol’s Gomez expressed optimism for the future of the netlabel scene. A hope that netlabels venture out of Japan and the West, and pop up in new, untapped areas (such as Taiwan, China, Korea, and Southeast Asia). A hope that net music diversifies beyond the “kawaii” and popular contemporary dance sounds. “Putting all these other nationalities under the fray will probably inspire a new wave of sound,” said Gomez. “A new culture not appropriated, but inspired.”

Photos: Header image – MEISHI SMILE at Belong release party, photographed by Ei Toshinari, provided by Garrett Yim.

Zoom Lens artists liquid.sunshine & Thought Tempo at ZL x Glitch City, photographed by Daylen Chiang, provided by Garrett Yim.

Noah Hafford live at Billy DeFrank LGBT Community Center in San Jose, provided by Devin Miski and Noah Hafford.

MEISHI SMILE at SXSW Perfume Official Showcase, photographed by Adam Kissick, provided by Garrett Yim.

Yeule performing, provided by Nat Ćmiel (yeule).

Ulzzang Pistol performing, provided by Zeon Gomez.

Head into the dark with debut footage of Sunless Sea’s first expansion

“The sea has never been friendly to man. At most it has been the accomplice of human recklessness.” These are the words that Sunless Sea, the game of nautical exploration and cannibalistic mutiny, first chooses to present to its players. Creator Failbetter Games wants us to have no illusions of our chances going in. When we sail out in our derelict vessel, the darkness of the Unterzee barely intruded on by our searchlight, it’s all too likely we won’t return.

But if we feel so vulnerable bobbing along on top the titular sunless sea, imagine being fathoms underneath it. That’s where Zubmariner, the first expansion to Sunless Sea, wants to put you: crammed into a metal tube, with cold water pressing in on all sides.

everything below this level is absolutely dark

In a new video released on Tuesday, Failbetter games gave us the first look at the Unterzee’s ocean floor with the lighting—and the lack thereof—in focus. Your ship, in its new submarine form, has a much greater halo surrounding it. Since everything not illuminated by your vessel is pitch black, you’ll need the beefed up running lights demonstrated in the video.

It’s disconcerting to think of the Unterzee, with all its dangers and mysteries, as only the surface of a terrible, vast expanse—the livable layer, in fact. In the oceans of Earth, anything below 1000 meters is known by the scientific / 1980s horror film term “the midnight zone.” Because sunlight can’t penetrate it, everything below this level is absolutely dark. Nightmare fuel like the angler fish and the vampire squid are found at this depth, as well as the sunken city of R’lyeh from Lovecraft’s dreams. What lurks in the inky depths of Failbetter’s subterranean ocean? One more way to set off from shore, never to return.

Sunless Sea’s Zubmariner expansion doesn’t have a set date for release yet. You can, however, purchase Sunless Sea via is website right now.

Bringing otome games to the other side of the world

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Otome games—visual romance novels targeted at women—don’t often find a wide audience outside of Japan. Not only do they struggle to market towards women in countries where dating simulators are less of a cultural staple, but the games’ protagonists and stories are often coated in a Japanese context, causing some of the magic to get lost in translation. Even breakthrough titles in the otome genre usually meet small niche popularity when compared to their male-oriented counterparts. That being said, some otome games have broken the barrier, finding their foothold in the west.

Among those chosen few are games like Alice in the Country of Hearts, a romantic reimagining of Lewis Carroll’s classic; Hakuoki, a game following a protagonist disguised as a man in search of her father; and Amnesia: Memories, a game in which the main protagonist awakens with no recollection of her past. These notable titles have overcome the cultural barrier, with many players and reviewers alike celebrating their distinct art styles, varied story routes and, in the case of Amnesia, expert localization for an English-speaking audience.

Their method of reaching out to a western audience mirrors that of another otome game, Purrfectly Ever After, which follows a burglar cat-turned-girl, trying to live as a real human while navigating her new city life. Purrfectly Ever After was designed specifically with a western audience in mind, with the team referring to the game as an effort to “bridge the gap between Japanese-centric otome games told from a not-so-Japanese point of view and storyline.”

“Otome games are popularized in Japan. It’s natural that those who are exposed to otome games are also those who are very much into Japanese ACG (anime, comic and game) culture,” said Sue Anne Chan, founder of Weeev, the team behind Purrfectly Ever After. “Unless the concept of the game is set in Japan, though, we want to make it as universal as possible.” Chan cited cultural and environmental differences as the largest barrier for western audiences, noting that “even though some otome games are localized in English, the elements of Japanese culture remain intact.”

Otome games have broken the barrier, finding their foothold in the west

Instances of cultural references that might not be removed during subbing and dubbing of otome games, such as the removal of shoes before walking into a room, or the act of ‘kabe-don’ (where one pins another against a wall as a romantic gesture), are just a couple of elements that might not be fully appreciated by a western audience at best, and alienate them at worst. Whereas non-playable characters in romantic visual novels generally fit neatly into traditional Japanese anime tropes (the cool character, the shy one, the intellectual guy, the tsundere one, etc.) newer titles in the otome genre have been more lenient with these roles when conceptualizing for a western audience.

According to a survey conducted by Weeev, an overwhelming majority of their fanbase said they prefer otome games with a moderately complex storyline, as opposed to a simpler one-track plot. Norihisa Kochiwa, who oversees development of one of the top otome game companies, Idea Factory, mirrored this sentiment in an interview with Siliconera, saying that they focus on the storyline as opposed to the gameplay itself. For western audiences in particular, character complexity even leaks into the main protagonist. While Japanese otome games generally feature a blank-slate character for the player to project their own personality upon, Chan said that games developed with Europe and North America in mind tend to portray leading female protagonists with more developed backstories.

“Western audiences like to see a lead with an established personality, unlike the ones stereotyped in typical otome games,” Chan said, going on to note that audiences for Purrfectly Ever After responded positively to their female lead Pastel being characterized as a “a strong-willed, cat-turned-human girl who is a leader of a clan and a hero of justice.” Even in the case of Amnesia, the most popular title among western audiences, the player is allowed to build a completely new personality for the protagonist following her memory loss. Each narrative decision slowly establishes her character as the game goes by, adding a layer of depth to the path that the player chooses. “I think the momentum has started to pick up among western audiences, and people are more receptive of otome games now than ever before,” Chan said. “The increase of fan base and coverage of otome games is prevalent. It will only bring more opportunities and awareness to the genre worldwide.”

Darkest Dungeon knows your weak point

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Darkest Dungeon (PC, Mac)

RED HOOK STUDIOS

We’re all pretty fragile, aren’t we? Never mind being mauled by fang and claw, merely being in the dark for a short time can deteriorate our defensive capacity. We grow paranoid and mad. Authors have long known this and picked at it with their words. Lewis Carroll used the language of nonsense to invent an unknowable monster, the Jabberwocky. The unknown is scary to us. And it’s this that H.P. Lovecraft so brilliantly exploited with his vast, unimaginable horrors that struck fear due to existing beyond the limits of humanity’s tether to sense and sanity. As with these authors, Red Hook Studios understands that our own psychology is among our greatest weaknesses. With Darkest Dungeon, the studio turns the dungeon crawler into a battle against paranoia, madness, and masochism as the toil of the journey warps the minds of your adventurers. You must deal with more than waves of monsters here. You have to cope with the unpredictable manifestations of the human mind when stressed towards breaking point.

Perfect for: Psychologists, masochists, Lovecraft’s disciples

Playtime: Six hours

The Westport Independent does*** ***** understand censorship

The Westport Independent is a game about journalism. And so, in the interests of good journalism, a full disclosure is in order: I was employed as an editor at a newspaper company in Hong Kong, the South China Morning Post Group, from 2012-2015. This is important because The Westport Independent is, specifically, a game about the self-censoring of journalism. And the South China Morning Post is a frequent target for accusations of self-censorship due to pressure from the Chinese Communist Party. I’ve seen self-censorship happen and I’ve seen it been falsely accused. Point is, I know it when I see it. And at the ironically named Westport Independent, I see a lot of it.

You are the editor-in-chief. You are 12 weeks away from the Soviet-esque regime shutting you down with its new, draconian media law. In this remaining time, you can turn your mouthpiece into a proletariat rabble-rouser, a shameless propaganda organ, or a trashy gossip rag. The other option is somewhere in-between all of these. It all unfolds at an editor’s desk stacked with a pile of articles that you need to copy edit and arrange into tomorrow’s edition. You have three basic levers to pull: you can toggle an article’s headline between the loyalist/rebel version; you can excise paragraphs from the text; and you can select the articles you want to run and the ones you want to spike. (You can also arrange the layout of the paper, but the impact of this, if there is one, is too opaque for my eyes.)

I know self-censorship when I see it

It’s in selecting articles where The Westport Independent rings the closest to reality, since in an actual self-censoring situation, headline choices are never binary—it’s usually more about obfuscating a controversial topic than it is in making an outright slant in the regime’s direction. In my experience, The South China Morning Post has taken the most flack in choosing to give pride of place to stories of dubious news value. This might be fawning profiles of pro-regime businessmen or publishing unquestioning reviews of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speeches. You can do the exact same in The Westport Independent. Go ahead and slap a review of the president’s inspirational biography right there on the front page, and be rewarded with invitations to galas from the iron-fisted regime.

Aside from this highly-charged form of curation, the rest of the game’s take on self-censorship is just too blunt and binary to feel real—it is solely and completely rebel vs. loyalist. In fact, the scariest part about self-censorship is the rarity of binary considerations;the slipperiness of the continuum. In my experience, self-censorship is an insidious process, and it often invades your psychology so slowly that you don’t even realize it’s happening to you. In fact, you may never realize it. Quite often, in a real situation at a paper that’s facing pressure from powerful overlords, a journalist might end up reinforcing the regime’s agenda while thinking they are paying dues to fairness and balance. There are glimmers of this psychology in The Westport Independent, such as when you find yourself choosing a headline because you think you’re including a winking subtext that rebels will understand as a dog whistle, but the regime will take at face value. However, there are too many moments where you do this only to end up surprised to find that you were given simple “loyalist” points for it between levels. The game is just not subtle enough to account for nuanced dissidence.

The aesthetic here is so similar to Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please (2013) that they may as well exist in a shared videogame universe. In both, the milieu is Soviet and the time period is 1940s. (You better believe newsreels open and close each play session.) But the comparisons to Papers, Please also lay bare the game’s other big flaw. Unlike Papers, Please, where you are making serious decisions right in the face of desperate and sympathetic people, The Westport Independent is a little too distant and removed from the individual to resonate on an emotional level. The game does deliver scenes between levels that color some of your writers’ inner lives, but they are too minor to establish much empathy for, say, a writer disappearing by the regime’s hand in the post-game wrap up.

A censored media is a crude and obvious instrument, but a self-censored media is something more odious. To be mired in it is to be engaged in a game of mental gymnastics to justify your actions. Somehow, dubious trade-offs start making sense: you might think it’s useful to cover a loyalist business leader in a flattering way, because it will help with access when his next controversy breaks. Soon enough, you end up taking non-existent orders from authorities that you think are watching but probably aren’t. You become filled with self-doubt. You second guess yourself. Even a good-hearted person can end up on the wrong the side of a repressive agenda, and yet still believe they are right. It’s too bad that The Westport Independent is far too blunt to carry this point home.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

January 27, 2016

Stay a while and “smell the polygons”

There are moments in adventure game series Life Is Strange (2015), typically once per episode, that encourage you to stop, relax, take in the surroundings. The camera slowly orbits protagonist Max Caulfield as she spends a moment away from the mad throes of her teenage years. She lies face up on her best friend’s bed, hands cradling her head, the light of a golden dawn streaking through the windows, and the world totally quiet apart from the tiny chirps of birds. Or she sits with her back against a tree stump, long grass tickling her fingertips, cushioning the denim of her backside, the solitude of the outdoors filling her lungs with a sigh of gentle relief.

But there’s a problem with these reveries. For the most part they’re forced upon you as a mandatory downbeat in the narrative. Not that they are an unpleasant shift in pace but it does mean that you encounter a moment of involuntary suspension. If you don’t feel like chilling out with Max right then it can feel like you’re only stopping the action from moving on to be polite, perhaps like you would for a friend. This swings the other way, too. If you welcome this downtime then you’re reminded for the duration that there’s a game to be getting on with due to a prompt in one of the corners. “Space Get Up,” it says (if you’re playing on PC). It sits there silently nagging at you, not letting you forget that, at some point, this lull will have to come to an end by your command. It’s a niggling distraction when, ideally, there shouldn’t be one.

to be the silence among the noise.

The sentiment that these carefree moments of downtime in Life Is Strange carries isn’t isolated. But it is lacking a crucial element from the gestalt to which it belongs: inertia. Its stillness isn’t pushing against other forces. To explain, take a look at this Daytona USA (1993) gif by Tumblr user “pk dub.” What’s significant about it is that it positions us against the speeding lo-fi cars that zoom by. There’s a satisfaction to be derived in comparing our own motionless to the busyness of the world around us—to be the silence among the noise. This dichotomy can help us meditate on the glory of that singular moment. And most videogame worlds cater to this, too, as they are made to be roaring simulations stuck in animated loops; populations that never sleep, traffic that never stops, forests stuck in perpetual daylight.

(Daytona USA, 1993)

Matt Hawkins of prestigious videogame collective Attract Mode wrote the same of this Daytona USA gif, using it as a starting point to discuss the wider sentiment behind it. “For many of us these days, our hands are always full and our minds always occupied,” Hawkins wrote. “We’re constantly working towards tomorrow without actually living in the moment. Hence why it’s important to occasionally drop what you’re doing and take a breather; observe and appreciate point A before rushing off to B.” The importance of this idea is that you’re stopping between destinations on your own terms to observe life as it moves around you. What Life Is Strange lacked in its downbeats is, firstly, the importance of allowing the player to arrive at these moments naturally, and also letting us be idle among kinetic activity, not kept separate from it in a peaceful microcosm. But, hey, don’t get me wrong: Games can afford to go a little slower, no matter what form it may come in. You’re doing alright, Life Is Strange.

In a more recent post titled “Don’t Forget To Smell The Polygons” (the origin of this article’s own title) Hawkins provides many more wonderful gifs created by “pk dub” that echo the sentiment witnessed in the Daytona USA gif—”forget that pause button and instead full-on stop dead in your tracks in whatever game, to simply enjoy the moment.” The post is a public service announcement; a reminder of how you can better learn to appreciate videogame worlds. We should also be thankful to the short-loop format of the gif which, itself, is a way to extend a brief notch in time into the eternal. You may also question why all of the games used are of late ’90s and early-aughts in origin. There’s no definite answer but perhaps it’s that the colorful, low-res polygons evoke the perceived simplicity and joy of the past. Anyway, you can see some of the gifs Hawkins shared below.

(Crazy Taxi, 1999)

(Shenmue, 1999)

(Katamari Damacy, 2004)

(Outrun 2, 2003)

///

Header image by pk dub. From Sonic Adventure DX, 1998.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers