Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 167

February 3, 2016

Advice from Torment: Tides of Numenera

Torment: Tides of Numenera is, in its own words, “chewy and full of strangeness.” The game’s beta sets players down in the city of Sagus Cliffs, where weird humans and alien “visitants” live in squalor beside buried spaceships. You meet citizens who can’t stop sprouting extra toes, others who drink and brood about psychic wars, and one who’s trying hard to stop a robot from having babies. They toil in the shadow of countless dead civilizations, as well as the shadow of the monumental Planescape: Torment (1999), whose themes, protagonist, and aversion to short sentences have been carried over intact to Monte Cook’s anything-goes Numenera setting.

The one constant in Cook’s screwball future is that nobody seems to have any idea what they’re doing. The instruction manuals for every space VCR went missing about a million years ago, and now people hit random buttons and hope for the best. And yet every skinless time traveler within the city limits is happy to dispense smarmy advice about how you, the Capable One, should live your life, just before they ask you to solve the riddle of the stars or repair the ancient machine that their dick is stuck inside.

I came away from the beta with a wealth of advice and aphorisms passed on by talking bugs and sentient triangles. Rather than trying to judge the unfinished game (which, I should disclose, I backed on Kickstarter), I’ve instead reviewed the advice that the characters in it were eager to give me.

nobody seems to have any idea what they’re doing

“Everything is worth seeing, even the boring bits. Take your time, talk to everyone you meet, and keep your eyes open!”

Some busybody told me this early on—it might have been Otero, one of those eccentric videogame characters who hangs around the entrance of a city giving people tips. It’s standard advice for questing minds: stick your hand in every burrow, follow every turtle. I had no idea how much trouble this approach would cause in Torment.

As I exhausted every dialogue tree (including that of Otero, who is himself one of “the boring bits”), I was given dribs of XP and several single-use items called Cyphers as rewards. These can only be consumed during a Crisis, one of the game’s hand-crafted combat encounters. But Crises are so rare, and so avoidable, that I missed every chance to use the Cyphers I collected. For the crime of being given these useless items (I believe I had four) by grateful NPCs, the game afflicted me with “Cypher Sickness,” a stat-reducing ailment.

It took me a while to take Cypher Sickness seriously. You can’t sell items or give them to other party members in the beta, so I wasn’t sure I could reduce my Cypher load at all until I found a Crisis. In the absence of other ideas, I resolved to keep picking up Cyphers and hope for a hair of the dog cure. I soon became very sick indeed:

“Never buy lunch from Meatmonger before you go for a chat with Master Artisan.”

A sort of science wizard warned me here not to buy steaks underground from a man who cuts them from vats of endlessly regenerating meat—the food gave him (the wizard) stomach trouble once. His recounting of this event was neither amusing nor useful. By this point my character’s very bones were afire with Cypher Fever.

Due to the beta’s restrictions on merchants, the Meatmonger couldn’t sell me anything anyway, so I was safe from his steaks. I stopped by an inn in an attempt to rest and dispel my item cancer, but the bed merchants would not accept my “shins” (the local currency). Disgusted, I threw my Cyphers on the ground at their feet. This also did not cure my Cypher Sickness.

“I’m sure the Cult of the Changing God will hold the answer.”

The cultists did not hold the answer. Instead they made me fix their multi-dimensional clock, ignored my requests to rent a bed, and directed me toward the next group of needy souls.

His recounting of this event was neither amusing nor useful

“The avatrol whistles while it runs, a fearful sound. Perhaps even for the avatrol.”

I had to pass a speech check to receive this wisdom, so you know that it’s good. It came from what looked like a floating glass eyeball wearing a robe. There are no “avatrols” in the beta, but this observation made me wonder if they’re one of those high-strung animals that attack their own reflections, as some cats do.

As it happens, I finally cured my character’s Cypher Sickness by accidentally killing him with a mirror. As in Planescape, the protagonist of Torment wakes up again right after “death,” so this turned out to be an easy cure for status effects. I wish I’d found it sooner, but there isn’t much in the beta that can kill you.

“You can laugh, but the old saying is undeniably true: the tongue that wields the words is deadlier than the hand that wields the sword.”

The old saying “the pen is mightier than the sword” is much snappier than this one, and it’s troubling to see the citizens of the Ninth World fattening up our truisms with their own alliteration. This came from Dhama, one of the grizzled psychics in the Fifth Eye, a bar cut from the same cloth as the Smoldering Corpse.

He’s not wrong. Intellect towered over the game’s other stats in my playthrough. The Torment beta isn’t balanced yet, but the original Planescape gave players little incentive to build a character for anything but conversation. It’s hard to tell before release whether developer InXile sees that as something to emulate or correct.

It’s exhilarating to watch a game lie with conviction

“When one stands at the utmost peak of the highest mountain, an advance is no better than a retreat: all change is decline.”

Spoken by a rotten old alien brain in a flashback told Choose Your Own Adventure-style. (Although they’re becoming a cliché in Kickstarter RPGs, Torment’s CYOA segments punch above their weight.) This advice demonstrates a commendable bias for inaction, which is one of the performance evaluation metrics at my dream job. But in the game, it’s also a laudable example of purposeful bad advice: the brain wants to delay you, not advise you. As you waste time listening to its philosophy, pondering all the “boring bits,” it marshals its strength to attack.

It’s true that the Numenera setting can feel indulgent, inclined to let too many far-flung concepts share the stage at once. But its shifting rules and narrative frames give the Torment writers more room to misdirect and disorient their players. It’s exhilarating to watch a game lie with conviction (as it does again later, in another note of false authority that I shouldn’t spoil), leaving players to work their own way to the truth. Of all the promising and exasperating signs of the Torment beta, this narrative courage stands out as the best reason to return.

“You might ask Mapper, over there by the shanties. He’ll be the one with the maps on his skin.”

By far the greatest advice I received in the Ninth World. Mapper was indeed right over there. He had the maps on his skin. He knew where I should go next.

February 2, 2016

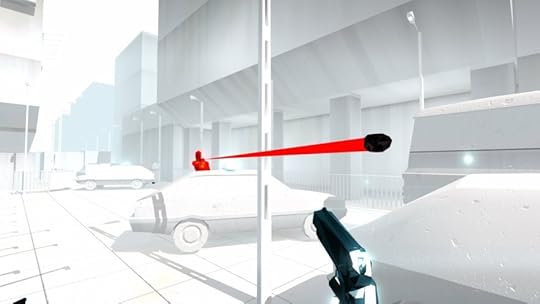

SUPERHOT is so close it’s burning our skin

The wait for SUPERHOT is over.

Almost.

With a newly announced release date of February 25th, the high-contrast, low-poly fever dreams of the Poland-based Superhot Team are only a few weeks away. A teaser trailer that accompanied the announcement shows these highly-stylized bullet hallucinations in action. While the “time only moves when you do” mechanic gives SUPERHOT the complexion of a puzzle game, it’s the frenzied, John Woo-inspired combat that’s center stage in the new trailer.

But behind the brief and seamless action of this last look before launch lies a longer road to development. What was originally born of a seven-day game jam event in 2013 became a full-fledged Kickstarter the following year. Maxing out at two-and-a-half times its early funding goal of $100,000, the team left a trail of screenshots and GIFs for backers to follow in the months that followed, culminating in the game’s closed beta last fall.

The game has come a long way since its first browser-based prototype, a journey that seems to mirror the game itself. As the idiosyncratic challenges of each level reveal themselves, players progress in fits and starts, adjusting their approach with every new failure. What begins as a process of trial and error eventually grows into something more natural and choreographed: a ballet of bullets and katanas that beautifully masks all the effort and struggle that went into creating it.

SUPERHOT should make its console debut on the Xbox One in March. You can find more information on the game here.

After 18 years dead, this bizarre videogame is making a return

The Nintendo Entertainment System sits comfortably in its position as the grand-pappy of the game consoles we have today. To go along with their new machine, Nintendo came up with a lucrative licensing system that guaranteed players a certain standard of quality, and ended up jump-starting the American game market after the infamous “crash” of 1983. At that point, plenty of people had already written off the “game console” as a dead idea—Atari, once a monolith of American entertainment, had fallen (after playing host to such awful products as that one infamous E.T. game)—but the “home computer” was a subject of some interest. Advertisements touted the promise of languages like BASIC, and tools like word processors or spreadsheets for finance, recipe catalogs, music collections, and whatever else you could automate.

not bound by the standards of taste or usability.

One of these computers—released the same year as the NES—was the MSX. While not particularly popular in the US, it was one of Nintendo’s stronger competitors internationally, because of course, games were a great way to show off what your computer could do, and you can’t be using Multiplan (proto-Excel) to plan your taxes 24/7 anyway. Metal Gear (1987) was introduced to run on MSX architecture, and Final Fantasy (1987) and Castlevania (1986) spent some time there, too. But, unlike Nintendo’s console, anything could be run on home computers. They became a space for bootleg games, or for hobbyists to make their own weird little creations—enclosed in plastic bags, distributed with zines, not bound by the standards of taste or usability.

This brings us to TPM.CO Soft Works, which describes itself like this: “A company creates a game work since 1985.” The page combines Japanese and not-quite readable English, and it calls back to those games that only got to strut their stuff on a handful of machines. First made in 1998 if the title cards are to be believed, Tarotica Voo Doo is an “ancient adventure game with movie such as stop motion animation,” and it boasts “110 pics for the opening movie, 160 pics for the ending movie… total 648 pics” of animation “drawn by hand.”

Tarotica Voo Doo has been exhibited at a number of shows, most recently the 2015 Tokyo Game Show Indie area, where it was displayed on an actual MSX machine, running off a 3.5” floppy disc. At the moment, it’s on Steam Greenlight to see if there’s enough interest to bring a port to the PC in 2016. With dissonant, sometimes clipping sound effects and a dark and minimal graphical style that fits its aggressively homemade aesthetic, Tarotica Voo Doo is as obscure as it looks, and equally unfriendly. But the way the website feels like something you’ve stumbled upon by accident, or the way none of the instructions are quite as comprehensible as you might hope, all goes toward making it nostalgically murky—like it didn’t really want to be found, like you tracked it down in a ragged zine and now you’re going to figure out what’s going on between all the bleeps and shifting pixels. There’s something wonderfully strange about that.

Even presidential campaigning is available in sweet, sweet VR

Don’t look now but Ted Cruz won the Republican vote in the Iowa caucus. (At the time of writing, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders were on track to split Iowa’s Democratic delegates.) Or maybe you want to look. I don’t know you or your political views. At the very least it seems safe to bet that at some point during this interminable campaign, which is still very far from over, you have wanted to turn away from a candidate. Just for a second, for your sanity.

Thanks to the magic of virtual reality, you can now turn your back on leading presidential candidates as much as you want. The latest film on the New York Times’ NYTVR app takes you into the crowds of the frontrunners’ campaigns: a diner with Ted Cruz, a stadium with Donald Trump, and anodyne event spaces with Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. Using a Google Cardboard headset (or just the app and your hands), you can spin around and see how audiences react to the stump speeches and guest entertainers. This makes sense insofar as democracy is actually about the voters.

Easter eggs hide at the periphery of every scene

The level of political insight to be gleaned from NYTVR’s narration is minimal at best. It turns out that Donald Trump feeds off the raucous energy of large venues whereas Cruz prefers more intimate meet-and-greets. In other news: Hillary Clinton uses a bevvy of surrogates on the campaign trail. Who knew? But this latest installment in NYTVR’s growing collection isn’t really about advanced analysis. It exists to give you an idea of the mood in these rooms. For all that campaigning is democracy in action; the distribution of primaries all but ensures that most of the citizenry will never witness this sort of fevered campaigning firsthand.

In terms of filmmaking, NYTVR’s approach to the presidential campaign is not particularly exciting. The camera sits still in the midst of the crowd and you can spin around its axis. The net effect is more panoramic than it is immersive. (One wonders, however, how the New York Times managed to bring a VR rig to campaign events without constant mugging to the camera from the crowd.) While the film’s individual scenes may be a touch lackluster, VR gives you the ability to look around in search of weird reactions. Easter eggs hide at the periphery of every scene: an audience member staring too intensely, a photographer tuning out the event to focus on his footage. These elements don’t add up too much of a film, but they bring enough amusement to suggest that NYTVR is contributing something to this campaign season.

Oh, and as a bonus, you get to witness this proto-fascistic Donald Trump song-and-dance number performed by three small children in virtual reality. Turn around and see if the audience’s reaction matches yours:

You can download the NYTVR app on the App Store and Google Play.

This parody of The Witness is more accurate than you might think

Be warned, this article contains mild spoilers for the end of The Witness.

///

Most of the people I know who have been playing The Witness since it came out a week ago have been doing so in the graces of midnight—”it’s an ideal late night game,” is the consensus. While loved ones are tucked up in bed, you can be quiet with The Witness, as it is quiet with you. There’s no music, no maddening rapid button-pressing, nothing to yelp at as it jumps out at you. And the mix of serene exploration and chewy puzzle-solving lends itself to caressing eyelids determinedly toward the ‘rest’ position. I manage about two hours of playtime before I have no choice but to go to bed otherwise I’ll be accidentally waking up on the couch the next morning.

What I’m saying is, at this rate, it’s going to take me a bloody long time to complete The Witness. Two hours, maximum, a day? And this is a game that’s supposed to take at least 40 hours (maybe more, maybe less) to finish, and possibly up to 100 hours to do absolutely everything it has to offer? Doing the math, I can see why some people may choose to push the long commitment of The Witness aside and entertain other ways to occupy their time. But the slight problem with this may be that a lot of people are playing it and talking about it all around you. And that eats away at you. In such a scenario, what you need is an abbreviated version of The Witness, and it just so happens to be that there is one. Well, sorta.

Australian game maker Ian MacLarty has created his own version of The Witness using his virtual world creation tool Vertex Meadow. What this tool does is render 2D images as 3D terrain. “With it you can create detailed and unusual 3D environments to explore using a 2D paint-program-like interface,” reads the description. You can also link multiple terrains together too, creating a larger experience with different moods through each transition.

For his game, MacLarty took a screenshot of The Witness and turned it into an explorable 3D space. By virtue of using the exact palette of the 100-hour long The Witness, this much shorter version of the game resembles its island as if you’re seeing it through beer goggles. None of the topography is the same and there are no sounds at all, but the warm bucolic glow of the place lives on through the colors.

Then comes the punchline

Despite all of the jagged grassy mountains begging to be explored in MacLarty’s The Witness, he gives us a path to follow, leading us up to a summit. There are no puzzles to stop you along the way, no doors sternly blocking your progress, nothing but you and this path (and the surrounding scenery). Then comes the punchline. When you reach the edge of the summit you get an on-screen prompt to “see ending.” Press the button and you’re redirected to Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” on YouTube. Yep, MacLarty is Rickrolling people like it’s 2008 all over again.

But, actually, that wizened internet meme in place of The Witness‘ actual ending isn’t irrelevant. I should warn you that this is where the mild spoiler comes in. And it’s mild because, as I’ve made clear, I haven’t finished The Witness and can’t possibly spoil it for you right now. But I know someone who has and who remarked previously that not many are going to like the ending. “That is definitely how a lot of people will feel about the ending,” they say about MacLarty’s Rickroll ending in reference to The Witness‘ actual ending. So, er, now you know not to expect too much from the end of The Witness, I guess. It certainly brings into question the value of putting in all those hours into the game, huh? I’m still going for it anyway but, well, now I guess I’ve reduced any expectation I did have to nil. Apply the “Enjoy the journey and not the destination” mentality to the game, and any other relevant truism that you have stuck to your fridge by way of glossy magnet.

You can play MacLarty’s version of The Witness in your browser.

SUPERHOT and the unique temporality of videogames

When the Wachowskis transported bullet-time over from Hong Kong cinema to The Matrix (1999), mainstream western audiences were wowed. This was the beginning of something new for action cinema, the ability for the camera to pivot around action, playing a moment from a multiplicity of angles that stunned and awed in equal measure. The camera was unhinged from static points, instead echoing the orbital movement of a clock or pendulum.

In the years following, slow-mo sequences in games misguidedly attempted to convert what was so fascinating about that spectacle into something the player could experience. Instead, it only introduced the banality of controlling an avatar in digital treacle. The real key wasn’t the high frames-per-second cameras, but the way the moment was crystallized and played out in multiple facets—the temporality of the situation was toyed with in a new and exciting way.

Many games have toyed with the elasticity of time, but SUPERHOT will perhaps come closest to digging into that curious sense of temporality which goes beyond the manipulation of the speed of time. In SUPERHOT, you fire bullets that tear vivid red scars through the interiors—austere, wiped-clean renditions of office architecture that are only a side-step from that famous Matrix Lobby scene. The speed of the game world is linked directly to your character’s motion, like a twitchy editor you scan the game speed forward in lurches or staccato beats. Bullets move primarily when you move, otherwise they hang in bizarre abstracted webs and patterns, cutting up the frame as they dissect the screen.

like a twitchy editor you scan the game speed forward in lurches or staccato beats

It’s been a curious experiment since 2013, soon to be a full-fat game, but it beckons towards something that only games can do with any real sense of agency: the power to alter the flow of time in various ways, something that is impossible within the confines of real-life. Time is a highly abstracted concept, perhaps one that is perceived only because we need it to be. Frank Kermode’s book The Sense of An Ending (1967) talks about how we are obsessed with quantifying time, demarcating it. Through religions, societies became obsessed with eschatological events, all for for the sake quantifying time, making moral decisions seem like they had impact due to a definitive end date and a guaranteed meeting with their maker.

As a species, this is frequently reflected in our art, even in the most basic structural premise of the ending: books end, films end, songs end. That isn’t to say temporality escapes subversion in these mediums. If anything, the constraints of physical mediums have encouraged artists to toy with temporality in bizarre ways. This happened most notably during the modernist period in literature, during which writers such as Woolf, Joyce, Ford, and Faulkner all wrote with a keen eye focused on the issue of presenting the moment as a reality on the page.

Instead of being able to guide a reader through a warped knot of plotting that obfuscated the narrative time, they instead focused on the experience of time itself. In Mrs. Dalloway (1925), the narrator ducks and weaves through the consciousness of multiple peripheral characters as they all experience the retort from a backfiring car, or their perceptions of a skywriting plane. In the text, this allows Woolf to bat the reader between the fractured, shell shocked mind of Septimus and the cluttered reminiscences of Mrs. Dalloway. Dorothy Richardson and subsequently James Joyce each attempted to capture all the minutiae of a day within one book, crafting the tomes Pilgrimage (1914-1938) and Ulysses (1922) respectively, but still kept in that free-associative feeling, that any instant in human perception could careen off into another lateral thought or moment.

Games that play with time, like SUPERHOT, translate that desire to explore a moment into a mechanical foundation. The lazy vectors of bullets precipitate a multitude of responses—specific approaches force the player to decide how and where to spend their time, knowing that each step taken will accelerate the trajectory of bullets, narrow certain opportunities and present others. The shared moment between player and AI is an interlocution of bullets and trajectories. Time and thought is reduced to a shared focus on those angles of impact and response, with the player’s agency providing such a multiplicity of responses that no other entertainment could hope to replicate the almost fractal nature of the action.

If time is an artificial construct in our existence, then digital time is doubly so. How time passes in games is unique to the hardware, the system clock usually being the anchor for all progression, with coded artifice creating a digital world that allows the simulation of time in a way that makes sense to the player. While games frequently have narratives that subvert the A-B conventions of chronological time, their main differentiating factor from film and literature is the ability to make the use of time as a tool or commodity that can be toyed with in a way that is beyond our ability in the physical world. SUPERHOT’s metered out instances allow the player to demarcate their own portions of strategic time: but importantly they can never go backwards. Braid (2008) offered a number of ways to alter time (with certain levels mirroring SUPERHOT’s convention) and rewinding to find solutions was par for the course.

the constraints of physical mediums encourages artists to toy with temporality

In Braid, creator Jonathan Blow tells us that this is a closed system the game cannot be rewound past its point of conception—which matches the limits placed upon Link in The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask (2000). Time can only be toyed with to a certain degree, as it begins to abstract cause and effect beyond the limitations of a computer simulation. Despite this, Majora’s Mask and Braid both show us how time in games can be fluidly altered, either by hopping forwards and backwards through it, or by increasing or decreasing its passage to create an effect. This is something ultimately impossible in traditional media, where our actual perception of events is not changed; passages and scenes can be repeated, but there is no autonomy.

Still, the repetition of the day’s events in Majora’s Mask helped to create a highly detailed microcosm of quotidian activity. Few games delve into the network of day-to-day life as heavily as Majora’s Mask, with the intimacy of people’s schedules revealing themselves to players as they learn them by rote. Inamura and his team created a network of layered interactions similar to those created in Modernist novels, but with the player fulfilling the function of author within remit of the text, jumping back and forwards to fill in blanks, carefully altering events to steer storylines in favorable contexts. Curiously, Majora’s Mask still fulfills Kermode’s assertion of the obsession with the eschatological, with the game centered around the fall of the moon on the city, reinforcing the fact that toying with time in narrative games still needs to be organised around a firm teleological point.

Even games that profess to have little to do with ‘time manipulation’ as a mechanic reveal echoes with texts that explicitly state it. Mode7’s realtime strategy (a curious term considering little game-time is truly ‘real’ or mapped to real time 1:1) games Frozen Synapse (2011) and Frozen Cortex (2015) explore the idea of agonising over a single moment for as much time as a player can stomach or afford. While Synapse is overly fussy in its detailed controls of human drone combat, Cortex instead prefers a simpler system that is nonetheless robust enough to draw players into endless iteration on simple actions inside the parameters of team-based future sport.

With its matches divided into short handfuls of time, the planning phase allows a player to move both theirs and their opponent’s team of robots around the play area, performing dry runs of plans. Tiny fractional differences in stopping distances and movements can result in huge differences in outcomes—a missed tackle or pass, a poor stab at guessing a player’s movement—which leads to obsession and tinkering in these plans over and over. The 30-second play time can then be broken up by hours of plotting individual moments over and over, in such detail and multiplicity that it recalls the literary devices used by Woolf and Joyce to explain the mental state of a conscious human in time. In much the same way that these authors compartmentalized moments in time and delivered them to readers, so too do the two players deciding on the best iteration of a few short moments. It leads to entirely different interpretations of situations that isn’t possible within the format of twitch-heavy occurrences of other synchronous videogame competition. The way these interactions then free-associate into a network of call and responses that can be endlessly pored over is tied explicitly to the game’s combination of overt planning, encouragement of iteration, and the real-time simulation of disparate ruminations.

And it is these curious temporal knots that make videogames unique. They function in ways that a novel or a film struggle to achieve, allowing a player to construct their own Groundhog Day (1993) style scenarios. They are in control of the iterative looping, finding their own points of interest and potential to alter time. This year’s Oxenfree comments lightly on this, by alluding to branching narratives and multiple end states. To achieve this, the ending is structured in such a way that it invites the player to play the game again and again to try and fix what looks like a less than optimal outcome—one that is linked to the time loops that beset the characters as they attempt to progress. Adding to the encouragement, the game even goes so far as to allow players to record choices that will appear in another player’s game, and it also breakdowns of all a player’s outcomes (as Telltale does in its adventure games), as if suggesting there were some hidden combination that might finally allow the narrative to change. In the end, the narrative cannot be corrected, the denouement and its results are always fixed from the beginning. The hint of some ultimate ‘correct’ solution instead speaks of the strange conceit of playing a game with branching narratives again to try and alter the outcome. When all’s said and done, Oxenfree is less concerned with the destination, but the experience of travelling, with its nested time loops echoing the player’s limited agency. It’s an idea that finds strange kinship in the futility of Dark Souls (2011) narrative; a game that throws notions of temporal structure to the wind with its half-forgotten legends and shifting, phasing timelines that allow its cyclical plot to continue without end.

games provide the ability to have a conversation with the fabric of existence

With these time-altering tricks, games place themselves within a canon of art that is dedicated to exploring a concept that at once defines and defies human existence. Perhaps stereotypically they are often overly concerned with packaging these explorations into mechanical devices, focusing on how time manipulation can alter play, as opposed to toying with time for reasons beyond the participatory—John Cage’s 639-year-long musical piece As SLow aS Possible is a prime example of something that exists on the very limits of participation.

Nevertheless, these temporal conceits in games speak to something atavistic. The ability to have a conversation with the fabric of existence is something that videogames can provide, and it is an experience that the agency of gaming makes possible in a way that other mediums cannot. Games do not simply comment on the construction of time, they allow people to twist, stretch, compress, replay and manipulate time in a way that allows a glance at the abstracted concepts that lie behind the ineffable machinations of existence.

Prepare to feed elastic bodies to the stylish Necropolis on March 17th

Last time we mentioned Necropolis, the gawp-worthy dungeon crawler wasn’t much more than a few entrancing gifs and a promise to sate our unending thirst for procedurally generated, spooky fantasy. Now there’s a set date at which you can start your death tally. Oh yes, Necropolis will release on March 17th, with pre-orders opening today.

And a set release date isn’t all that Necropolis has gotten since we looked away—it also appears to have grown a sense of humor. Made by Harebrained Schemes, the creators of the Shadowrun games, Necropolis is a game about exploring a very dangerous tomb and getting killed a lot by awful monsters. With that sort of premise, the temptation to embrace grimdark self-seriousness (as Shadowrun Returns is occasionally guilty of doing) must have been enormous. Instead, we got this piece of dance magic over the summer:

Harebrained Schemes also announced that players won’t be biting the dust alone. Necropolis will be playable with up to four people. This actually fits pretty cleanly into the game’s narrative; the titular super-structure relies on the life force of freshly murdered adventurers to keep operating, and by operating I mean continue to kill adventurers. It would make sense that the more life force you can pour in at once, the better for the Necropolis.

what eats the Gemeaters?

There are details that I dearly want expanded on, such as the ecology at work in the Necropolis. Harebrained Schemes has stated that a predator/prey hierarchy totally exists within the dungeon, but the specifics there have always been vague. Gemeaters, presumably, eat gems, but what eats the Gemeaters? Still, seeing a fantasy game so absolutely swole with style has been enough to keep me highly interested in Necropolis. Even divorced from its Dark Souls-inspired combat, funkadelic music and Pixar-minimalist art style, there’s a lot to like.

In a recent press release for the game, studio manager Mitch Gitelman claimed “If you think hanging out with your friends and whacking on monsters sounds fun, this is the game for you.” If there are any people in the house who hate their friends and think monsters should go un-whacked, it’s probably best you show yourselves out.

The inescapable echoes of Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak

It might have been the cruise missiles that triggered it. One of a string of upgrades nudged towards me by my commanding officer, charting the slow expansion of my carrier’s already formidable arsenal. It was the name— cruise missiles— that was so distant from science fiction, so connected to a sideshow of images of war. It would have been the 1990s when I first saw a cruise missile launch, the flashcut plume of smoke followed closely by the hammerblow of ignition—the camera whiteout as its automatic exposure struggled to account for the solid-fuel flare that drove the missile until it was a distant glowing speck, arcing over a distant amber land. That amber land was Iraq, and these projectiles landed there unseen by the cameras, the audible roar of destruction distant enough to follow a few seconds after the flash of a successful impact.

The cruise missiles of Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak take flight in much the same way, though from the elevated viewpoint of the game’s camera they seem distinctly more benign. Perhaps benign is how the developers at Blackbird Interactive saw these armaments when they added them to the vast aircraft carrier-on-wheels that serves as the player’s base of operations in Deserts of Kharak. And perhaps they are benign, perhaps it was the amber sands that triggered my memory, or the low drone of everyday military radio chatter. Perhaps it was even the talk of prophets and holy wars, the leader mounting a “sermon on the rock” clad in something that seemed to flicker between an industrial gas mask and a jet black veil. Whichever it was, the accumulation of those images pointed to something in particular, an aesthetic I was born into, something unnervingly familiar.

It was war as I knew it, distant, technological, baked in desert heat, waged on desert sands

It was war as I knew it, distant, technological, baked in desert heat, waged on desert sands. It was the idle dialogue of my forces, all call signs and denotations, which brought to mind the lazy discussions that ran under every leaked video of a drone strike. It was the word “coalition”, used so casually to describe the loose alliance of forces that seemed to stick in my head like a grain of shrapnel, an annoying itch. Hadn’t I been here before? Not on the distant planet of Kharak, not among these fictional races and their squabbles, not beside these improbably vast machines of fantastical war. But here in the desert, watching towering plumes of smoke emerge from impact sites while my quietly idling armored assault group issued a faintly audible complaint over the radio channel, “I can’t take it.” he whispered “it’s too damn hot”. Haven’t we all been here? Here, hovering as a distant observer, staring at a screen, hunched forward in the short winter days of January.

///

Many would have played the original Homeworld as bombs fell on Iraq. In 1999, bombings could sometimes be a daily occurrence, with more than 100 airstrikes targeting the northern no-fly zone. This campaign would invariably be in and out of the news, but would be ever present, the desert and the accompanying plumes of smoke, the military chatter and targeting overlays. There would be the occasional computer generated simulation, as crude vehicles and the brash arrows favored by news agencies crossed paths. That conflict, and the interstellar war at the heart of Homeworld, could not have felt further apart. Homeworld was a 70s Chris Foss book cover: patterned ships set against glowing nebulas, shimmering space battles of unprecedented scale. It was less a war and more a space opera, a grand journey built on complex three-dimensional strategy. Its story, that of a race of exiles pursued through space by vast forces, in search of what was once their home, seemed to borrow from grander sources than games of the time were used to. Anabasis, by greek soldier and writer Xenophon, was chief among them, charting as it does the march of 10,000 mercenaries from Persia back to the relative safety of the Black Sea’s shores in 401 BC. This ancient work has come to represent an inspiration for countless stories, and in Homeworld’s case it formed the backbone for a campaign where each unit persisted across escalating missions that headed deeper and deeper into the unknown. This ancient influence is not only evident in the game’s structure, but in its naming conventions, which mirror ancient Middle Eastern and Asian tribes.

The 2003 sequel, Homeworld 2, only furthered these connections, focusing more on the deity of Sajuuk and the conflict between the tribes that believed in his power. Only months before, the first coalition forces had entered Iraq, their long road to Baghdad filling news broadcasts with amber lands and mechanized war, columns of tan vehicles rolling out across deserts that stretched to the horizon, punctuated by the black smoke of burning oil fields. Once again, Homeworld 2 might have offered something of a respite in its starward vision, its colorful explosions lighting up distant voids. Yet on the columns rolled, and on the cameras rolled, and the images of a desert war flickered in the background whether you were watching or not. That journey into Baghdad has also been compared to Anabasis, not least in The March Up: Taking Baghdad with the First Marine Division, published as one of the first full accounts of the invasion in the following year. Written by Bing West and Major General Ray L. Smith, it recounted their experiences and the experiences of the division tasked with taking Baghdad. Both were military men, Bing West being a Vietnam veteran as well as assistant secretary of defense under Ronald Reagan, and from its first pages March Up reaches towards an epic mode, using Anabasis as a way to connect modern marines to the great warriors of old. Unlike Homeworld, which finds in Anabasis a grand and fantastical journey of desperate struggles, March Up finds the questionable glory of fearless combat, crudely recasting an invading force as warriors in search of a home.

///

Deserts of Kharak, though appearing over a decade after the original Homeworld games, once again finds structure in the journey of Anabasis. Setting the player on a journey across a great desert in search of a mysterious technology, it casts them and their carrier out into the sand, to forge a trail across dangerous lands. This is reflected in every aspect of Deserts of Kharak, from the persistence of units across missions, to the limited resources that force the player into careful restraint rather than the building of vast conquering armies. Adaptability, decisiveness, and tactical awareness are the qualities this journey asks for, not the machismo of overwhelming force, the arrogance of shock and awe. It is an effective translation, the space combat of the original games matched with ground-based analogs, the power relationship of small strike crafts, ranged armor and heavy cruisers still intact. The three axes of open space have been replaced by the bluffs and dunes of the desert, making line of sight and elevated positions key to making the most of a limited unit count.

ships no longer backlit by nebulae but buried in sand, corroding under scouring winds

This, in some ways, grants Desert of Kharak even more tactical detail than that of its forebears, where the topography of a battle mattered little. Yet, it is in its aesthetics that Deserts of Kharak most differs from its series, and these changes are what seem to bring the echoes of the world Homefront was born into to the fore. This desert land is inescapably connected to those grand campaigns that might lay claim to Anabasis, those desert invasions that are so unpleasantly familiar. It doesn’t appear to be a purposeful choice, but instead a kind of overbearing influence, one which has leaked into this world by exposure alone. In Deserts of Kharak those Chris Foss ships are no longer backlit by smoky nebulae, but are buried in the flowing sands, their bright patterns corroding under metal-scouring winds. The Middle Eastern inflected names and music no longer seem in service of an exotic atmosphere of space travel. The Anabasis is no longer that of a journey home, but of an “expeditionary force” striking out into lands unknown. All of these elements, even those that once could be thought of as defining aspects of Homeworld’s colorful space-fantasy, somehow conspire to evoke the history of war that has shadowed the series; echoes from another world, another time, rising to the surface.

Unpleasant as it is to accept, this association is a natural one for a certain generation. The symbol of the desert has become colored by conflict, those images of scorched sand difficult to forget. Deserts of Kharak is not to be blamed for unearthing these connections, for so easily slipping behind these images and trying to make them strange. There is some integrity in its detail, its precision, its distance. It manages to reach the epic mode, the grand narrative, to evoke a mythical journey now lost to us. But it also fails to escape the easy orientalism of that same myth, the simplicity of bloodless violence. It is a throwback in many senses, not just to the history of its own series, but to images of war that came to us already cold, already distant. To shots of cruise missiles launching but never landing, just glinting over that amber land.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

February 1, 2016

This videogame about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict makes peace uncomfortably achievable

I solved the Israeli-Palestinian situation over the weekend, and the experience didn’t fill me with hope for the future.

Let’s backtrack a little: Benjamin Netanyahu is still Israel’s prime minister, Palestinian statehood is still far from a reality, and international pressure or support for any just outcome is lukewarm at best. All of which is to say, my solution could only exist in a fictional universe. And so it does—I was playing ImpactGames’ PeaceMaker: Israeli Palestinian Conflict, which was recently updated for iOS and Android.

PeaceMaker tries to play down its fictional side. It is very much of this world, opening with a montage of archival clips that goes back to the 1940s, including Winston Churchill’s inspection tour of Julich, Germany. The clips that follow tell a depressing story of violence on both sides interspersed with the occasional summit. The opening montage is reasonably evenhanded though narrow in its focus on high politics. There is no real room for the broader effect of the last 70 years on the welfare of all involved. This is serious statecraft, the intro signals, and that impression is only furthered by the game’s dashboard, which is full of dials measuring changes in popularity occasioned by each decision you take. At the center of the screen is a map resembling the one used in the Civilization games. As crises arise, different cities will appear in squared off crosshairs. Make no mistake, PeaceMaker’s design tells you: This is serious work.

Who said peacemaking was hard?

You are working as a head of state, either Israel or Palestine’s—your choice. If you can’t choose, the game will do so for you. The differences between the two positions are largely flattened by the game’s mechanics. You make decisions about politics, security, and construction. Each of those decisions causes the games’ Israeli and Palestinian popularity scores to shift. Achieve a 100-point rating on both sides, and peace will have been achieved. The game’s central conceit is that the average action will make one side marginally happier and the other marginally less so. This is both true and facile: Peace is hard. But that is PeaceMaker’s real insight into the peacemaking process. So, sure, it’s hard to find policies that please both Palestinians and Israelis and that goes a long way to explaining why both sides are where they are today.

But in PeaceMaker: Israeli Palestine Conflict, a mutually acceptable solution can be achieved. Actually, I pulled it off on my first try. The game had randomly assigned me the role of Israeli prime minister. Mazel tov, I muttered under my breath. The job, it turns out, is not that hard—at least if you aggressively buy off your citizenry with economic stimulus packages, ignore your ministers, use the police to tamp down protests, crack down on settlers, very gently pressure your Palestinian counterpart, and ignore all news involving Iran. Twenty minutes later, I had cruised to a two-state solution. Who said peacemaking was hard?

PeaceMaker tries ever so hard to be reasonable, but its path to victory is that of a supremely fanciful game. Each individual move is plausible enough, but the possible combinations boggle the mind. In that respect, the game comes to feel like geopolitical Tony Hawk. Initially, I found this thrilling: For the first time in my life peace and Palestinian statehood were within reach. After a few minutes, however, the absurdity started to eat away at me. Was there really no decision that was too unpopular to end the game on the spot? Did I really have an unlimited amount of time to achieve peace? Was the support of my constituents and government really that stable? The biggest luxury in PeaceMaker is time and patience. Yes, the conflict it lightly fictionalizes has been going on for decades, but the average politician does not last that long. After 30 minutes of radical peacemaking, what I really wanted to know about PeaceMaker was whether my avatar could meet the same end as Yitzhak Rabin.

Following an appearance at a 1995 peace rally in Tel Aviv, Rabin was shot and killed by Yigal Amir, an extremist who believed the prime minister was betraying the Jewish people. That assassination and the context out of which it emerged is the focus of Amos Gitai’s documentary, Rabin, the Last Day, which opened in America last weekend. Seeing as memories are short, it’s worth returning to the time of the Oslo Accords, which were meant to lead to Palestinian self-determination (though not statehood). Rabin, the Last Day brings back the fevered reactions to Rabin’s negotiations with the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Yasser Arafat. Gitai shows posters with Rabin depicted and scenes of extreme parliamentary rancor. (Rabin was also the target of multiple failed assassination attempts in the year leading up to his death.) The film is not exactly a whodunit—the proximal who is the only thing we really know—but it is an investigation into how the events of November 4, 1995, came to pass. There’s plenty of blame to go around.

I broke PeaceMaker after just five minutes.

I tested PeaceMaker on Friday, and that would have normally been that, but I couldn’t escape the Rabin question. On Sunday evening, I finally gave in and fired up PeaceMaker for one last test. I played as the Israeli prime minister using the most difficult setting available and set out to become the most polarizing politician in the country’s history. (To be clear: My policies bore no deliberate resemblance to Rabin’s. I was purposely more impractical and polarizing just to see how the game would react.) I attempted to demolish settlements and walls, rolled back military and police deployments, sent aid to Palestine while spending nothing on domestic policy, and offered my Palestinian counterpart as much support as I could. Consequently, I was very popular in Palestine and desperately unpopular at home. There are no elections looming around the corner in PeaceMaker, but if there were I’d have had a better shot in Ramallah than Tel Aviv. Still, no matter what I did, I remained in government and untouched.

I broke PeaceMaker after just five minutes. The game’s website indicates that it is possible to be removed from office if you are too unpopular, but that is not what happened to me. A video announcing a terrorist attack popped up, as such videos periodically do in the game. When the video came to an end, however, I could not return to the action. This had never happened when I was playing to win. I was stuck in an infinite loop, left with nothing to do but watch the footage over and over again. I was still in office, but fundamentally powerless. Time refused to move forward. I conducted the experiment a second time and met the same fate. PeaceMaker’s narrative may not feature the likes of Yigal Amir and it may indeed be possible to get kicked out of office, but the fact that the game breaks down in situations of extreme polarization is perhaps more revealing about its worldview.

That is a fitting encapsulation of the PeaceMaker: Israel and Palestine Conflict experience. The game has an immense capacity to be imaginative—the two-state solution is achievable in a remarkably brief amount of time—but that imagination only extends so far. The game cannot conceive of individuals acting in poor faith or outside of ‘reasonable’ parameters. Indeed, it fetishizes a narrow definition of reasonableness. Members of your side may disagree with you, but the game expects them to act reasonably. History, however, has shown that the sort of reasonableness PeaceMaker traffics in is in short supply, both domestically and internationally. Would that more of human behavior matched ImpactGames’ models, we might be better off.

You can download PeaceMaker: Israel and Palestine Conflict using the links on its website.

This Go student has become the Go master—and it’s a computer

If Go is mentioned in the US, it’s in the context of complicated games, or hard games, or games with some element of “purity.” It’s just white stones and black stones on a nineteen by nineteen board. You play by putting stones down, not moving them, if you surround your opponent’s stones they are “captured,” and that’s more or less it. Ostensibly, no game could be simpler. But if you’ve ever tried to learn how to play Go, you’ll know it feels a lot more like the spoiled-for-choice paralysis of staring at a blank page

The board has 361 spaces, all of them technically available to start, even if there are specific areas make for good (or popular) moves. With so many choices available, it becomes difficult for a beginner to assess them all, and for a long time, this was the problem for computers too: machines had to spend time and effort assessing moves a professional human player has the experience to know not to play. The number of legal Go positions (~2*10^170) is higher than the number of atoms in the observable universe (10^80). So the brute force method (which is sort of available for Chess and Checkers) really was off-limits for machines.

it’s a twist on an old tradition

I know most of what I know about Go because of how engrossed I got in a 65-year old novel, Yasunari Kawabata’s Master of Go (1951). I figured out how to play, and played mostly against computers and puzzle books. I watched YouTube videos of professional games, followed the move sets available online.

In line with current trends in computer science, AlphaGo approaches the problem sort of like I did. It learned to play Go when the Google DeepMind team behind the algorithm fed it vast swathes of professional games to watch and analyze. Then they had it play against other Go algorithms, and against itself, over and over and over. Now it can beat other Go-playing machines 99.8% of the time, and it just beat the European champion—Fan Hui—in a decisive 5-0 set, with no handicaps.

Google Maps learns when you like to leave for work, Siri learns how you mumble, so what AlphaGo is doing isn’t totally new for our computers. But, from a Go perspective, it’s a twist on an old tradition. Kawabata’s novel describes the way the professional Go world works—there’s a ladder-based system with ranks and numbers that determine who has to play whom to prove they’re the best, or what each game means for the ranking (and career) of a professional player. These professional players take on apprentices, and learn by playing each other. The novel centers around two players—a young upstart and an old master—who each represent ways of thinking about Japan in the aftermath of World War II.

The young man wins, the older man dies, and Kawabata implies that with this defeat comes the death of an older way of behaving. It doesn’t mean the same thing to be a Go master anymore. There will never be another player quite like the older man.

your smartphone can beat you while making obnoxious quips

In the US, at least, there was a lot of commotion around DeepBlue facing off against Gary Kasparov in 1997, as if the future of the human race were in the balance. Some people believed the game was too complex, involved too much lateral thinking for a computer to “understand” it. It took a while, but now, even if you’re any good at Chess, your smartphone can beat you while making obnoxious quips and telling you what your friends are out doing while you try to prove you can keep up with a machine the size of a deck of cards.

AlphaGo is scheduled to play Lee Sedol, the world’s current best in March, and Sedol appears to be confident that he can beat it. I assume he’ll be studying his old games in the meantime.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers