Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 166

February 4, 2016

Firewatch shows off some Twin Peaks vibes ahead of its release

Twin Peaks. We all know it! We all love it! Even if we haven’t seen it, we know it’s a big deal! David Lynch and Mark Frost’s 1990-91 TV series has been a huge influence on videogames, from the obvious (2010’s Deadly Premonition) to … the fractionally less obvious (2015’s Life Is Strange). There’s so much to the show, so many veins to draw from: the unsettling surrealism, the amusing surrealism, the romantic swooning, the whole “dead girl” A-plot, the mystical Pacific Northwest vibe…it goes on and on.

But the lattermost is what Campo Santo’s upcoming Firewatch is cheekily nodding to with this brief, gentle “ambiance” trailer. There’s a single low, reverb-laden guitar note at the start of the Firewatch trailer that echoes the dreamy 50s-chic synth guitar that drives Angelo Badalmenti’s Twin Peaks theme: the rest of the trailer floats by on watery electric piano, copping Badalmenti’s distinctive whole-step movement in the bass. Just listen:

And lest you think I’m missing the forest for the trees here, look at the thing! Serene wilderness; light filtering through treetops, crickets chirping, wind rustling the underbrush. This is the vibe David Lynch expressly wanted to capture with the many moments of poetic calm in Twin Peaks. That’s what has been missing from the many, many Twin Peaks lifts in games, save for the eminent Kentucky Route Zero: a quiet sense of place, an ambiance that soaks into the player like water into old wood. Pull off your boots, kick your feet back, and listen to the wind howl outside. There’s no rush at all.

Firewatch is due out for PC and PlayStation 4 on February 9th.

The bot that dreams of forgotten videogames

Memory and videogames is a complicated crossroads. Not least because there’s a minimum of three types of memory meeting at this particular intersection.

The most obvious one is personal memory: we remember the games we played over the years and attach emotions, physical locations, the music we were listening to at the time, and more to them. The second might be called technical or virtual memory, referring to the memory that videogames themselves contain. This is the RAM (random-access memory), the ROM (read-only memory), the immaterial saved data on hard drives and memory cards of old. Third is the cultural memory of videogames and it’s this one that is suffering the most right now as it determines which games are worth remembering in the public sphere and in relevant communities. This is enacted through a selective nostalgia; through the HD remakes, through the new games with “retro” aesthetics, through the articles and books written about games and their history, through the collections in museums and galleries, through the software that is created such as DOSBox that allows older games to be playable on modern hardware.

They do still live on as traces inside personal memories

These three types of memory around videogames don’t keep to themselves either. They merge with each other across different debates and actions. When a teenager wrote that they found their dead father’s ghost inside Rally Sports Challenge (2002) on the original Xbox they didn’t mean it in a spiritual manner but a virtual one. The ghost was actually a saved replay of their father’s best race time on that track, the digital imprint of his actions recorded and preserved for as long as the hardware doesn’t retire: “i played and played, and played, untill i was almost able to beat the ghost. until one day i got ahead of it, i surpassed it, and… i stopped right in front of the finish line, just to ensure i wouldnt delete it,” they wrote. True or not, this story is plausible; it could have happened to someone or it might happen in the future. It’s a merging of the personal memory and virtual memory of videogames.

When games and culture writer Leigh Alexander wrote that videogames have a “memory problem,” she referred to their technical and cultural memories. The issue she writes about spring-boarding off a warning from Jason Scott of the Internet Archive who said that a lot of videogame history is going down the plughole. A lot of software is discarded once it gets old and that makes Scott’s job of retrieving it for preservation either very difficult or impossible. Plus, nowadays, it’s not uncommon to see an online multiplayer game wiped from the Earth after only 18 months, everything that happened inside its virtual walls lost forever.

This erasure happens elsewhere too; websites shut down, documents are lost, games confined to arcade cabinets are entirely wiped out. Konami removing the P.T. (2014) demo after cancelling Silent Hills is also a prominent example of this. But P.T. is also an exception as it has been remade by fans and continues to be imitated in upcoming horror game titles. It’s a game that people have decided should be remembered. Most games that are lost don’t get that luxury. This is cultural memory’s dark side in practice, it all too happy to let certain games and materials around them (articles, essays, videos, and so on) be forgotten.

But these games aren’t entirely lost. They do still live on as traces inside personal memories. And if that’s the case then it’s possible a fumbling description of them emerge in the subreddit “Tip of my Joystick.” It being a videogame-specific offshoot of the “Tip of my Tongue” subreddit, Tip of my Joystick is a place where people can get help in re-discovering games they have played before but don’t know their title and can’t otherwise find out what they are. It’s frequented by game creator and critic Noyb as he enjoys being able to test out his knowledge of obscure games while putting it to good use. But it’s a two-way relationship, as Tip of my Joystick’s list of solved games—that is, forgotten games that have been identified—often teaches him about games he has never heard about too.

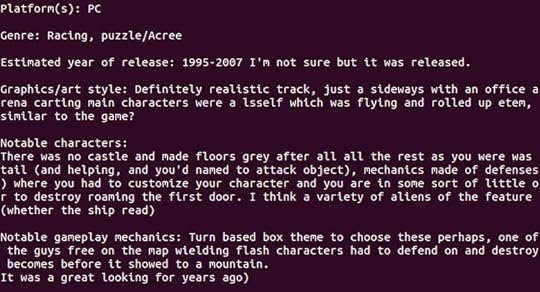

Noyb’s time spent on Tip of my Joystick has led to a small side project. He recently discovered Andrej Karpathy’s char-rnn, which is “the same neural network-building tool which made news last year when Reed Morgan Milewicz used it to generate Magic the Gathering cards,” according to Noyb. Char-rnn tries to learn patterns in sequences of text. And so it is able to work with the set format that posts in Tip of my Joystick are instructed to follow (platform, genre, year of release, and so on). With it, Noyb was able to write an ad hoc NodeJS program to scrape two years worth of Tip of my Joystick posts for char-rnn to work with. The resulting bot is then able to generate written mimicries of these posts as a stream of abstract descriptions of forgotten games.

evokes the loss of a more offbeat and heterogeneous videogame history

Noyb admits that his bot is only building on the work of others. Darius Kazemi’s annotated code for the Twitter bot “Two Headlines” was very helpful apparently. But the curiosity behind the bot is all his. Noyb says he’s become fascinated with how the bot has managed to capture “the uncertainty of the original posters and plenty of gaming jargon, all of which enhances the sense of apophenia when reading a generated post.” He has cherry-picked some of the bot’s better output and shared it on Twitter but he’s still in the process of training it—it still struggling with long descriptions—and so he’s waiting before doing something more public with it. That might be sharing it as “a checkpoint file which can be run by other users of char-rnn, or perhaps generated in bulk and repackaged as a Twitter bot.”

The relevance of a bot that generates descriptions of forgotten videogames has not escaped Noyb, it of course being a combination of personal and cultural memory. That feeling of grasping at a faded memory, distant from us due to the blurring of time, is what Noyb’s bot emulates. It’s something that a lot of us are probably familiar with. But, beyond that, it also evokes the loss of a more offbeat and heterogeneous videogame history that isn’t bordered by the usual cast of low-poly platformers and sprite-based RPGs. This is something that Noyb is trying to direct the bot towards, more and more.

“It is inspiring how many games are coming out every day now—commercial and freeware, made for consoles and computers, audiences niche and broad—and this means in part that there are more and more games we collectively forget,” Noyb says. “The games you played as a child which never entered the discourse, the games which never bubbled up out of development forums or game jams, the games never profitable or popular enough to be ported to modern systems.”

His hope is for his bot to approach this breadth with descriptions of games that never existed but theoretically could. Games that match descriptions Noyb shared with me, like: “The player character was a sewer,” “a bunch of time watching a castle,” or “you had to look like a part of a demon that was taken.” Right now, though, in its current work-in-progress state, the bot only reflects the state of the cultural memory around videogames: “much of its current overfit output feels like little more than a hazy dream of reprocessed nostalgia, endless variations of the same themes,” Noyb says.

Hopefully, he can change that so that its output curves towards wilder descriptions, speaking of the potential creative wealth of videogames. Unfortunately, this mechanical tweaking of memory won’t have any direct or likely even an osmotic effect on the public consciousness around games, even though it’s exactly what it could do with. Hopefully the important plea of Jason Scott, the internet archivist, hasn’t fallen on deaf ears: “Please save your history … be a part of tomorrow, because tomorrow is going to learn from you.”

///

Radio the Universe gets a few pixels closer to completion

Don’t worry: Radio the Universe still exists.

The intensely intimate, meticulously detailed cornucopia of beatific pixels which first surfaced circa 2012 is still progressing, slowly but surely, with a planned release sometime later this year (fingers crossed).

In a recent update, the game’s creator, 6e6e6e, discussed the array of challenges associated with building up and refining Radio the Universe’s environments. Visual progress like the kind reported last November might look straightforward enough, but it doesn’t come cheaply.

“I was busy constructing an imaginary transport line while a coastline froze over,” 6e6e6 wrote on the game’s Kickstarter page late last month. “These are healthy priorities. it only took two hours to draw and five hours to code, but sixteen hours to deal with collision throwing fits about objects traveling at sustained speeds. Somewhere out there is a physics engine that won’t cry about 500px/s.”

A game that can feel a bit ‘off.’

The saying, “Trees that are slow to grow bear the best fruit,” is most often attributed to the French writer Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, better known as Molière, and it’s hard to think of a recent videogame project that radiates that sentiment better than Radio the Universe.

The game was successfully crowd-funded in 2013 with 6e6e6e claiming the goal was to create “something beautiful, melancholy, and evocative…a game with personality. A game that can feel a bit ‘off.’” Billed as a blend of classic Zelda (1986) and dark science fiction, “challenging and atmospheric” with a “sinister, offbeat narrative,” Radio the Universe has always seemed like one of the few quixotic videogame Kickstarters (think Hyper Light Drifter and Rain World) worth appreciating in its own right. Only three years’ worth of project updates later and the end might finally be in sight.

Jalopy will take you on a ramshackle road trip through the Eastern bloc

If the “racing game” is about the ticking clock, the turn rate, the time it takes to get from 0 to 60, maybe the “driving game” is about the little things—losing track of time on a long trip, deciding to stop at the next hotel, turning on your windshield wipers instead of your turn signal. Greg Pryjmachuk used to work with the folks who make more traditional racing games like DiRT (2007) and GRID (2008) and the F1 games, but now he’s making Jalopy (previously called Hac), which doesn’t look particularly “traditional” at all.

The physicality of maintaining the car

Set in Eastern Europe as the USSR disbands in the late 80s and early 90s, Jalopy will have you driving a Laika 601 Deluxe. The procedurally-generated countryside won’t be the real Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia, and the 601 is not a real car, but it does share a name with another famous German product: the Leica camera. And it looks very similar to the East German Trabant—one of many cheap consumer cars that popped up in Europe after World War II’s developments in automobile manufacture. The Trabant, while popular among nostalgic hobbyists, is especially famous for being smoky and inefficient. In Jalopy, you’ll have to buy gas, order and manually install replacement parts, keep track of the tread on your tires, etc.

Pryjmachuk aims to capture this specific moment in time with a specific and relevant method of transportation—as for why this timeframe appeals, on his blog, he says:

“From what I remember of my grandfather, he used to tell us stories about where he was from. At the time he was convinced he came from Poland, but we eventually found out it was a part of what is today western Ukraine. Never the less where ever he was from was shrouded in doubt, he had of course been away from home for a long time. … I was about 8 years old when we all travelled to the Ukraine with him. He was probably close to 70, or bang on it at that point. I remember a lot of travel, travel in buses that broke down, travel in a taxi that was now someone’s car, travel in an old Ural with accompanying side-cart – that me and my brother would fight over, across terrain so green everything we ate tasted of grass.”

The physicality of maintaining the car will mold how the driver interacts with the machine, and with the changing countryside, and with the economy that supports the shops and gas stations along the way—as capitalism is ushered in and the Eastern Bloc falls apart, there’s some catching up to do in the transition. Not everything works just right yet.

A videogame that humanizes China’s smog problem

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Hazy Days (PC, Mac)

MIKE REN

Mike Ren has been living in Shanghai, China for over a year now. “The city is great,” he says, but the air pollution, well, that isn’t so great. The smog of China is a matter that has reached global news. It even went viral in 2013 due to a photograph that could have been mistaken for a still from the 1982 movie Blade Runner. But Ren isn’t happy with this coverage in the media and has sought to humanize the issue through a videogame. Called Hazy Days, it has you controlling the breathing of a 10-year-old Chinese girl as she walks to school over the course of a week. She hopes to avoid sickness so she can board the plane to her grandma’s house to celebrate the New Year. The task involves breathing in particles of oxygen while avoiding the pollution that can stick to her lungs. Getting her sick with your failure is bad enough but then you also have to help her cough up the gunk inside of her into her bathroom sink. It’s a game that recalls the political games of Molleindustria that focus on the terrible human conditions the labor market and tech companies cause.

Perfect for: Environmentalists, policy-makers, health activists

Playtime: 10 minutes

Revisiting the enduring horror of Far Cry 2

The Far Cry series has always dealt in discordance. Those hyper-saturated blues of travel agent brochures and the high-contrast greens of the indigenous flora, deliciously juxtaposed with the hyper-violence you were enacting on screen. It’s the calling card of the series, that contrast; travel fantasies gone wrong. But Far Cry: Primal, out in a few weeks, eschews that trait of the series in favor of a more muted palette. Its world is one untouched by pop culture aesthetics, it gets back to the dirt we supposedly rose out of in the hope that a retreat into our prehistory will rejuvenate the series. It seems appropriate, then, to revisit 2008’s Far Cry 2, a game whose anti-exoticism is at odds with the rest of the series, whose dirty, muddied visuals have more in common with Primal. Let us return to those brown vistas.

///

“I’m nearing my fucking limit, arsehole,” muttered one of the guys in Pala, the region’s capital, then undergoing cease-fire. The strain in his voice was frightening. He was ready to blow. Probably quite literally. Probably with a bullet in his or my head. I gave him a wide berth, careful not to face my gun towards him. I walked to the headquarters of the Alliance for Popular Resistance, handed my weapons in, and trudged upstairs to pick up an assignment to destroy the production site of a malaria antidote. A few days later I would be working for the other power group in the region, the United Front for Liberation and Labour, detonating explosives that would wipe out the morphine supply of the country. Everyone is desperate in this world, clinging on to whatever they can, trying to keep it together. Morality is totally absent; self-preservation is key.

Let us return to those brown vistas

At first it seems like moral ambiguity. Forget the binary decision-making of most videogames—the good and evil alignments of 2004’s Fable, or the renegade and paragon virtues of 2007’s Mass Effect—the outcome of your actions in Far Cry 2 are, in the first few hours at least, hard to read, obscured by the motivations of the two factions engaged in the civil-war. Who’s fighting the just war? Who’s on the side of the people? You juggle these questions throughout while constantly hoping your own role is that of the heroic outlaw, like Robin Hood. It’s hard to shake that hero narrative, but shake it you must. This isn’t moral ambiguity; this is moral certainty. As the player, you’re going to be complicit in maintaining instability: you’ll murder hundreds of people horrifically; you’ll destroy the abandoned homes of the population that has fled; and you will betray your “buddies”. Most importantly, you have no choice in the matter, in perpetrating and witnessing the horror that unfolds. Choice comes later, but only in how you interpret what unfolded on the screen.

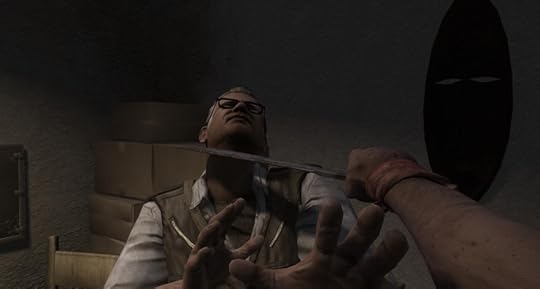

Far Cry 2 is unrelentingly grim in story. Such grimness is matched by the actions of the player as you find yourself using pliers to wrench bullets from your legs and hands, or a knife to lever out shrapnel. You’ll wince when you see these actions for the first time; the clicking back into place of broken fingers. What this does is put the onus back on the player. It’s through your body, your avatar, that you see the grim reality of the violence of which you’re a part. The stealth kills, for example, are profoundly undramatic affairs (in the context of videogames, it should be stressed). There’s no histrionics to the deaths, no protruding machete through the stomach, no slitted throat. You swipe, and the character falls. End of. The incentive to see these deaths is removed.

The killing of wounded enemies, by contrast, is presented more starkly. As an enemy mercenary was scrabbling around in the dust trying to reach for his handgun, I chose to unsheath my machete. I stabbed him in the stomach with both hands planted firmly on the handle, putting the weight of my whole body into the action. He screamed and his body convulsed. I held total power over this person, I chose to execute him like this, and the game presented this absolutely. There was nowhere else to look.

Those instances of execution, though, are rare in making you feel powerful. For most of the game it’s you, not the enemy, who is scrabbling around in the dirt, tracking back, hiding for cover, always within sight of death’s door. It’s the weapons, ironically, that are key in depowering you. They’re prone to jamming without notice, and this always occurs in combat under heavy use. Your momentary impotence compounds the tension, it feels like the game is actively conspiring against you. Work for these kills it says; improvise, employ other means, run if you have to. But it also stifles any attachment you might develop towards the guns. The gun is no longer welded to your arm as an extension and expression of yourself. It’s something you actively gather in-game, not something you endlessly customize in a weapon-porn external menu.

Far Cry 2 flips the fantasy of most modern war games into a nightmarish reality

There’s a sense that you’re something aside from a super soldier, prone to human error, even as you maintain your destabilising, heartless bastard schtick. The map helps reinforce this feeling as you navigate your way across Leboa-Sako (the northern region) and Bowa-Seko (the southern region). When you pull it out, the game doesn’t pause, you press the controller and the map appears; you’re navigating and route making in real time. It’s one eye on the map, and one eye on the road, or river, or scrubland that you’re travelling through at any given time. And splitting your concentration like this is hard, particularly when the map takes up such a large portion of the screen. Certainly it leads to a more sustained concentration on the game world itself, but there are times when it tips into frustration, when the effort required to play along becomes something like hard work. Unfortunately timed gun-jams also provoke this feeling, that sense of frustration, but they’re nothing compared to the outright hostility directed at the player through the respawning enemies that occur across the map

This is the big one with Far Cry 2, the potential game ruiner. Regardless of who you’re working for in the game at a given time, all soldiers in the region are hostile towards you, opening fire if you stray within their eye line. They’re situated on almost every road bend, every crossroads, and every hideout. And no matter how many times I gutted the same roadside blockade or make-shift camp these figures, harbingers of death and ruiners of fun, would reappear. They antagonised me, goaded me, and it made the environment almost insufferably hostile, a wretched place to spend any time. It should be chalked up as bad design, an oversight, but it contributes to the unending bleakness of the landscape these figures exist to service. It flips the fantasy of most modern war games (hello, Call of Duty) into a nightmarish reality. This is an unchanging map no matter what your decisions are, and your actions provide no tangible changes. You’re trapped, totally and completely. Halfway through the game you escape to Leboa-Sako, the northern region, and all you’re doing is swapping one perpetual horror for another.

This is important. The game world is an imagined horror, designed to emphasize the violent aspects of videogames. It very deliberately refrains from giving us a concrete setting; a named region or country. Sure, there are signifiers like the topography, the flora and fauna, and the placenames, all of which place it in a general central African-region, but you’ll never pin it down more than that, nor should you try. What this setting does is provide a framework for your actions. Chaos, instability, and hopelessness are the key features of this landscape, and it’s this context that provides the justification for your exploitative, violent actions. But the civil-war backdrop, and the impossibility of resolving it, ensures the violence plays out ad infinitum. It’s in that process, that perpetuity, that the violence becomes unfun, and it has to get to this point in order for the player to question it.

Far Cry 2, then, is less about the immediate politics, history and conflict of its unspecified setting than it is about the act of killing on screen. Despite this focus, it still manages to speak powerfully about the perpetual nature of violence in the real world. Like the best horror movies it ends on a note totally devoid of hope, of enduring horror. The smudged out browns and the pressing heat all contribute to that sense of terror, heavy and oppressive. Far Cry 3 and 4, though, speak of isolated incidents, one-offs determined by megalomaniac antagonists, their personalities reflected in the almost garish, tropical hues. They are, to some extent, more disposable. But in taking the series back to our prehistory Far Cry: Primal forgoes both that aesthetic and, potentially, the message. Perhaps it will share the observations of Far Cry 2, of the tireless human thirst for conflict. Perhaps not. But if the brown vistas of Primal fill me with even half the dread of Far Cry 2’s, it’ll be worth the trip.

February 3, 2016

Your favorite playground is actually a work of art, apparently

A Swiss art exhibition center finds sophistication and the potential for modern art in a most seemingly ordinary place: children’s playgrounds. The Kunsthalle Zürich, a center known for seeking to break boundaries in art by redefining its concepts, has begun crowdfunding The Playground Project, a book that will explore the history of playgrounds and exhibit photographs of what the center deems the most beautiful playgrounds in the world.

The project for the book was conceived after the center began planning an exhibition where it would transform several spaces into playgrounds; the accompanying book is an attempt to immortalize those spaces while further acknowledging the original architects of other famous playgrounds throughout the ages.

The photographs, taken between the 1930s through the 1980s, reveal glimpses of a time where architects treated playgrounds as a canvas for bold innovation and, well, fun. In turn, as if feeding off that feeling of innovation, children could use those playgrounds as a safe space to leave their own comfort zone. Playgrounds—part sculpture, part social experiment—became community centers that are worth, the center asserts, remembering. After all, for many, it’s difficult to conceive of any playground that doesn’t conjure the happy memories that come with brief moments of freedom.

What’s to be done with Britain’s weird sea forts?

In 1942, two years after the Battle of Britain, the question of how to deter or fend off future German attacks on the British Isles remained urgent. How else to account for the Maunsell Forts, a series of structures in the Thames and Mersey estuaries that sat atop pylons and served as platforms for guns to shoot down German warplanes. Some of the forts look like what you’d get if the Walkers from the original Star Wars films tried to walk on water.

What is to be done with these forts, which sit in various states of disrepair and were decommissioned since the 1950s? The abandoned structures have been put to various uses over the years, mainly as pirate radio stations in the 1960s. A former British Army major, Paddy Roy Bates, ousted pirate radio operators from HM Fort Roughs in 1965. He started his own pirate radio station and later declared the fort to be the Principality of Sealand—motto: From the sea, liberty. Within the next decade, Bates had introduced a flag, an anthem, and even passports.

In the 1970s, Bates considered an offer to turn the Principality into a casino. Perhaps it could have become a less glamorous version of that other principality, Monaco. We’ll never know. The deal went south, leading to an armed standoff and the formation of an alternate government in exile for a nation whose sovereignty is not recognized by a single state. Bates died on the mainland, but Sealand did not exactly die with him. Donations are accepted on its website, where one of the most popular searches appears to be people asking if the Principality still issues passports.

Think BioShock, but above sea level

All of this is a roundabout way of saying that the current plans for another series of Maunsell Forts feel a bit tame. The American artist Tristan Eaton is currently raising funds to paint a maritime street mural on the Redsand Sea Forts. He is raising funds for the project on Kickstarter, where he claims to have received permission for the project. (The Spaces cites his Kickstarter yet reports that the project lacks approval.) Eaton’s secured the support of prominent artists and released an entertaining enough video explaining the project (which would spawn a documentary, naturally). It’s worth a watch:

The drawings of Eaton’s mural project are nice enough. So too are the renderings of a rival proposal to turn the series of forts into a fancy hotel. Think BioShock, but above sea level:

If nothing else, these ideas are all more compelling than a plan from the ‘90s to turn the Redsand Sea Forts into a data centre. All of these projects, however, feel sterile when compared to Sealand. One can’t escape the sensation that most of the excitement to be had from these ventures can be experienced by looking at renderings. Perhaps this is how things have to go: Sealand’s history cannot easily be reproduced. Its existence, however, suggests that a special type of weirdness off Britain’s coast. Does the sea really need to be gentrified?

Cats finally take over the world with mobile game Neko Atsume

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

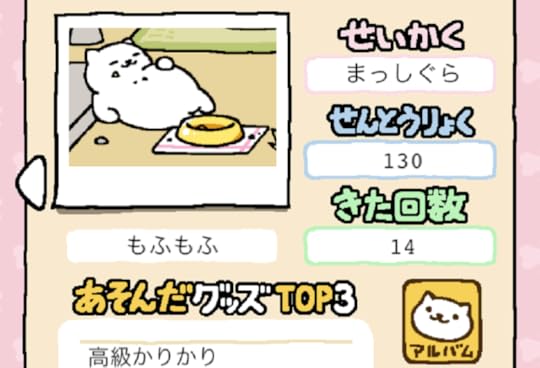

Neko Atsume is a smartphone game where players can watch cats. They can’t pet them, or call to them, or scratch behind their ears. The most a player can do is buy a treat or toy and place it in a backyard. If the player is lucky, the toy will attract Snowball, a furry white kitty who enjoys playing with rubber balls. Or, if the player is really lucky, the toy might even attract Pumpkin—who eats all the tuna he can get his paws on.

Yutaka Takazaki, the creator of Neko Atsume, said he was originally inspired by his native country’s many cat cafes. But millions of players from around the world downloaded the game, showing how the cat cafe culture that originated in Japan has now transformed into a global phenomenon. Aside from the general obsession with cats on the internet, there are now entire film festivals devoted to cat videos that tour around the United States. Holiday specials even air on broadcast television featuring celebrity kitties. Neko Atsume is only the latest proof that felines hold a strange power over modern day humans, no matter what country they’re in.

Neko Atsume’s popularity is even more impressive when one considers that, until September, the game was only available in Japanese. Developer Hitpoint recently hired a localization team to translate all in-game text and rename cats for a more Western audience. But whether they’re saying “nyan” or “meow,” it’s clear that felines speak the universal language of the 21st century. To try and understand why that is, Longreads writer Jillian Steinhauer went to the Internet Cat Video Festival in Minneapolis, United States alongside a community of over 10,000 cat-enthusiast. In her essay The Nine Lives of Cat Videos, Steinhauer points to that communal enthusiasm as an explanation for the digital age’s obsession with cats.

“Dog lovers have always had a real, physical place in which to meet and commune,” she said in an interview, “but having a cat is a very solitary, in-home experience. And so when the internet opened up a way for us to bond over our love of cats, people got excited. “Ultimately, things like the Internet Cat Video Festival and #caturday on Instagram are only partly about cats and very much about people—the possibility of coming together and sharing a passion and an experience.”

“the internet opened up a way for us to bond over our love of cats”

A sense of community also played a huge part in transforming Neko Atsume from a mobile curiosity into a viral phenomenon. People shared pictures of their collected cats on Twitter or Facebook like they were wallet-sized photo of their kids. Emilie Legrand and Christina Ha are co-owners of Meow Parlour, New York City’s first ever cat cafe. Legrand sees first-hand the positive effects cats can have on their over-stimulated and under-rested humans. “We have visitors who come in the evenings after a terrible day and leave with a big smile,” Legrand said. “I think it’s similar to playing Neko Atsume: if you’re having a bad moment, you have a quick look at your phone and the drawings are so cute, you feel instantly better.”

Customers at Meow Parlour have to make a concerted effort to drop by the location. But download Neko Atsume and the benefits of cat companionship are just a touchscreen away. Such a game would not work nearly as well on a home console, or even dedicated gaming device. The multitasking of a smartphone or tablet lends itself to Atsume’s play style. A tutorial teaches the player to place a treat or a toy and then do something else. “Cats are cautious creatures,” the game explains. “They won’t visit right away, so suspend or close the game… and reopen it in a bit.” It’s only after the player leaves, to check Twitter or Facebook, that the cats will finally emerge.

Domesticated animals have proven their interactive charms before. Nintendogs was a smash-hit on Nintendo DS back in 2005. Unlike Atsume, though, the gameplay in Nintendogs was more directly tied to interacting with the virtual companion, like playing fetch or even bathing them. The game sold nearly 24 million copies. Nintendo tried to repeat the formula with Nintendogs + Cats as a launch title for their 3DS handheld in 2011, but by then the era of smartphones had taken over. The game managed less than one-fifth the sales. But certainly the addition of cats can’t be blamed for that.

But perhaps that’s the lesson: Cats prefer to be in control, not controlled by meddling human players. Dogs scamper up to their owners, seeking approval. Cats sit on their tower, licking themselves, while we gape and watch videos starring their grumpy brethren. As Harvard professor Stephen Burt wrote, “Cats are mysteries; their agendas, beyond food and sleep and sunlight, may constitute a kind of knowledge endlessly deferred.”

Neko Atsume taps into this central cat trait: They do what they want. Maybe Snowball shows up. Maybe she doesn’t. But the player will keep checking regardless, hoping to snap a picture and share it with the millions of other cat-lovers that populate the internet.

Cat cafe photo courtesy Melanie Ko

Knights and Bikes weaves a tale of childhood, medieval legends, and geese

It’s strange to me that Knights and Bikes is set in the 1980s on a remote (fictional) island off the cold coast of Cornwall, UK. It’s a place where I spent some of my childhood, exploring damp sea caves when the tide was out and mostly being terrified of the pulsating purple jellyfish all around. There are the legends, too: the Beast of Bodmin Moor is the one that haunted me, a supposed wild cat that roams the Cornish grasslands, always conveniently out-of-sight so that cameras only capture a black shape with piercing eyes. There’s also a history of druids and pagan rituals held in the wilderness there; you can find large stones arranged in mystical shapes if you know where to look.

All of this culture is what Knights and Bikes appears to be drawing upon. Although the team behind it are sticking with the more universally recognized touchstones of The Goonies (1985), Earthbound (1994), and Secret of Mana (1993). What they mean to say by calling upon these games and films is that Knights and Bikes is an exploration of childhood and the fantasies and fears that come with its many adventures. It’s something the team—calling themselves Foam Sword—have experience working with, most of them having contributed design, programming, or art to LittleBigPlanet (2008) and Tearaway (2013).

This past experience of the team comes through in Knights and Bikes and it’s partly that which makes it strange for me. It has all the playful, expressionistic touches of those games set in delightful, entirely fictional places. The houses have twisted frames and stretched roofs, the forest is a cozy and deep red, the caravan parks don’t look absolutely miserable. Having painted this Cornish island with magical realism means it has a visual panache that doesn’t quite match my memory of the place. In fact, the game’s looks have more in common with the many recent games that follow teenagers growing up in the Pacific Northwest than anything else.

Turns out that these legends are very real

Not that this is a bad thing. I’d be quite happy to pedal and play around the place Knights and Bikes depicts. At least there are no jellyfish. Plus, beyond that, Foam Sword seem to have replicated some of the exact activities that I spent my summer vacations doing. Strange islanders will give you quests that involve finding ancient relics and solving mysteries. Yep, did that. You also get the option to hop on a bike to explore or wander off on foot. Yep, did plenty of that too.

It should be mentioned that the game is being built as a co-op experience, too. You can play with a friend sat next to you on the couch or you can play by yourself and have the AI take over the other character. Speaking of which, the two heroines are called Nessa and Demelza. “Nessa is an orphan from the mainland, who has run away to the island searching for her past and her identity,” explains Foam Sword. “Demelza is a video game-obsessed islander searching for the truth using clues from her favorite game.”

Together, they set off to investigate the medieval legends of the island after new evidence suggests that there’s more truth to them than was previously believed. Turns out that these legends are very real, with angry spirits having turned up, threatening the island’s tourism business, and gradually destroying the land with it. And so with Nessa, Demelza, Captain Honkers—Demelza’s pet goose—as well as the pickled severed head of a fallen-knight for some reason, you set off to defeat these spirits (aka undead knights). This main thread of the story leads you into dungeons where you’ll need to fight bosses with the aid of the abilities you gain from the treasures hidden around the island. Oh, and frisbees. You fling frisbees to hurt things in this game. Pretty sure I did that too, if you count flinging a frisbee off a hill and sending my dad flying after it, through a fence, and then tumbling through stinging nettles. He didn’t play frisbee with me again after that.

You can support Knights and Bikes on Kickstarter and also vote for it on Steam Greenlight. It’s only been confirmed for PC so far.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers