Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 164

February 9, 2016

Upcoming mass surveillance game asks if you’d really pull a Snowden

What would you do with the national security (read: espionage) apparatus at your fingertips: Would you defend civil liberties or use the reams of information collected each day to satisfy your own ends?

Need to Know, the debut title from Australian developers Monomyth Games which is raising funds on Kickstarter as of today, is in large part concerned with this question. You play as a worker in an intelligence agency and your decision to prioritize either the greater good or your own shapes the game’s narrative structure. The game, however, is not really about you, the intelligence worker. It is about the collection of data. No human could be the protagonist of this story; we are all just holding on for dear life.

The Kickstarter trailer for Need to Know is narrated using an excerpt from cybersecurity research Dan Geer’s 1997 speech to the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Technology. Post-Snowden, 1997 may feel like a more innocent time, but Geer’s speech still feels very much of our time. If you didn’t know better, you’d think the narration was written just for this trailer. It’s not like Geer subsequently changed his tune. In 2014, he told attendees at the cyber security conference Black Hat USA:

“Every speaker, every writer, every practitioner in the field of cyber security who has wished that its topic, and us with it, were taken seriously has gotten their wish. Cyber security *is* being taken seriously, which, as you well know is not the same as being taken usefully, coherently, or lastingly. Whether we are talking about laws like the Digital Millenium Copyright Act or the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, or the non-lawmaking but perhaps even more significant actions that the Executive agencies are undertaking, “we” and the cyber security issue have never been more at the forefront of policy.”

If nothing else, cyber security has never been more at the forefront of videogames. The uncanny aspect of Need to Know’s trailer is that there is now a language around games involving security bureaucracies. The protagonist works at the Department of Liberty. You’ve seen this sort of Orwellian doublespeak before—and not just in Orwell. Likewise, the game’s visualization of an ominous bureaucracy shares a fair bit in common with Papers, Please (2013)and The Walls Have Ears (2015).

None of that is really a knock on Need to Know. Its trailer has enough verve to suggest that the game will add something to the genre. Yet the existence of this genre and, more specifically, a series of associated visual and linguistic tics, says more about our society than any individual game. After Edward Snowden (who lurks in the background of Need to Know’s entire plot) the basic complaints about domestic surveillance have coalesced to the point where they can be introduced using shorthand and quick nods. We need to talk about these matters in more depth, but Need to Know is not wrong in noting that versions of these discussions can often happen without saying all that much.

Unravel wants to help us mourn, but doesn’t know how

Unravel begins with a letter from its creators that thanks you for purchasing the game. It explains to you the power of the medium, the senses of love and loneliness about to be explored, and how long they as a team have been pouring their hearts into it. The font and spacing makes it resemble the prelude to Thriller (1983), where Michael Jackson promises that he does not worship the devil.

A game that signals its own history and globe of emotions as active parts, Unravel began for audiences last year when Coldwood Interactive’s creative director Martin Sahlin was called to the stage of EA’s E3 keynote, as if it was his turn for show-and-tell. Like a schoolkid, Sahlin was earnestly and visibly anxious, his hands rattling while holding up Yarny, his star, a Funko Pop-sized wad of craft stuff shaped like a cat or a devil, with beady white eyes that look perpetually sad.

After the preamble and the curtains lift, you meet a grandmother longingly walking along the stairs of her warm cottage home. She glances at photos of children who once visited more often. And at that moment you know exactly at which junction this is going to end.

///

We’re very raw when we mourn. I don’t think people really consider the true malleable lumps they become, the way they sort of recede into a shell so as not to stumble through any more motions. Momentum is hard; you almost desire manipulation because it’s easier, to be given answers for your pain when there likely aren’t any. I’m there right now. It’s what’s going on. The family has been dented and we’re all still in the aftershock, figuring things out.

This couples a recent cultural tendency to project sentimental connections onto multimedia, as if the eerie coincidence of a TV drama’s syndicated subject matter is akin to it catching our bodies when we buckle. It’s just logistic contention and then a digital placebo. I’m being mean, of course—it can work both ways. Years ago, watching a new Clone High (2002-2003) on the second night of shiva seemed like a solid break. We couldn’t have expected that the running gag of that episode was JFK’s teenage reincarnation sobbing uncontrollably over the Ponce de León, a character introduced only to die comically. My brother, my cousins, and I whiteknuckled through the first half, glancing at the backs of each other’s heads, waiting for someone to change the channel on everyone’s behalf. That episode still isn’t as funny as I know it is.

///

The editorial staff here knew I’ve suffered a loss. They have never meant me any harm, especially not over assigning reviews. They just didn’t know a videogame starring a precious felty doodad sets its final level at a funeral.

At least, the final level of Unravel is in front of a funeral. In the background, sparkling images of sad human processions glow among the tombstones. In the foreground, the ol’ stone-faced Yarnster deals with wind obstacles similar to Gusty Glade in Donkey Kong Country 2 (1995). In the background of other stages I saw grandchildren sit among the wonders of nature and family while in the foreground I navigated block puzzles and was chased by a rabid hamster. In Unravel’s weirdest detour, the first of the many feel-bads, I watched nature take a hit from humanity’s pollutants, literally manifested as guys in hazmat suits and glowing green vats of acid sludge. In terms of subtlety, it scores higher than Captain Planet, but lower than Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze (1991).

Unravel’s a pile of travel package photos

In the background are memories—literal family vacation photos commissioned by the game’s creators—deconstructed into constellations of light. In the foreground is Yarny, who never breaks eye contact as it scampers back and forth like Bugs Bunny singing “This Is It.” In the background are broad strokes of empathy, generalized “moments” that play a chorus of violins. In the foreground is a pretty mild videogame, controls that do feel like you’re wrestling with floaty fuzzy weightless mess makers, with softball puzzles and, in contrast, breakneck action sequences that are unfairly clinching.

Yarny is a kind of a Forrest Gump figure to the world around it, minus the aphorisms and plus a knack for getting eaten by birds. Yarny rarely interacts with the emotional highs (sunny family good times) and lows (dark and gloomy deaths on personal and global scales) on which this game is apparently based. Hell, Yarny barely looks at them. Either the context or the game is a subtitle track to a different feature.

I am not doubting the sincerity of Coldwood. They’re a small team with a portfolio of sports and fitness games who are pursuing the distressing path of honesty, and emotional honesty is a good direction for most videogames. Between my states of tragedy and theirs I’m sure we could have a constructive chat, but nothing about their game has benefitted. Honesty and quality are two different traits with different exchange rates. I’m currently a soft emotional waterballoon who will work off the shiva rugula when I stop sleeping until noon and I haven’t even squeaked playing through Yarny’s magical journey. I cried at the end of My Dog Skip (2000) and I don’t even own a dog. Here I felt (give me this one pun) nothing, which isn’t a failure unless that’s a work’s key investment. Unravel’s a pile of travel package photos, and could actually take a few notes from McDonald’s ads on how to sell personal moments largely unrelated from the product they’re interacting with.

Despite all of its cutesy posturing and promises, Unravel is still looking to fill some kind of void. And I’m not sure if that void is its shortcomings as a mood board, as a videogame, or a cloying digestible basket of “feels” for EA.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Portal 2 experiment results in beautiful wormhole art

Dear Chell,

Where have you gone?

This is your fault. You chose this path. The Aperture Science testing environment has been proven entirely safe for each test subject. Yet your typical violent behavior towards the equipment has proven that false.

I’d just like to point out that you were given every opportunity to succeed. There was even going to be a party for you. There was going to be cake.

Are you dead? I told you: When you’re dead I will be still alive. I said that. Remember? I warned you. I did. It was not a lie.

Now you have broken my heart.

GLaDOS

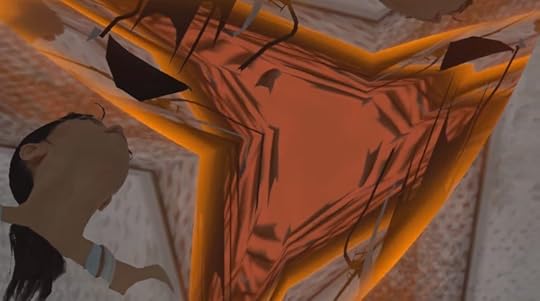

Chell is floating in eternity. She is surrounded by both an endless nothingness and countless duplicates of herself. It’s like someone melted all the mirrors in the world down to liquid and created a huge lake of crystalline reflections out of it with Chell at the center. She looks perplexed. She looks distressed. You can see it in her eyeballs as they leer mindlessly in confusion. Chell isn’t alright.

This is the result of a Portal 2 (2011) experiment by YouTuber “CrowbCat.” To use their words, they crushed Chell between two portals. As you can watch in the video (above), a portal is placed on the flat surface of two opposing crushers—one on the ceiling, one on the floor—creating a loop between them. If Chell falls through the bottom portal she emerges from the top one, falling once again towards the bottom portal. Ad infinitum. This is a trick that you can perform in both Portal games (there’s even an achievement connected to it) so it’s nothing remarkable by itself. Where this experiment does hit new ground is the addition of activating the crushers.

a beautiful series of wormhole art

The crushers allow the portals to move. This is something that was new to Portal 2 as previously they could only be static when shot on to a surface. Valve needed the portals to be placed on moving panels as, in Chapter 5 of Portal 2, this is how you cut neurotoxin generator tubes using a laser (watch it here). Even so, it’s one feature that Valve didn’t allow players to mess around with much, not even in the level editor that shipped with Portal 2. CrowbCat explains that to set-up this scene with the crushers and portals, they had to use a “special command” inside the Portal 2 SDK (software development kit) that allowed the portals to be placed on moving panels.

The result: As Chell is falling from portal to portal, the crushers are activated and the space between the two portals is reduced to nil. The game’s systems are not equipped to deal with this. And so Chell is trapped inside the portals. But rather than being crushed, she is instead caught inside some other realm; a terrifying limbo.

“It resulted in infinite psychedelic visuals such as giant spirals, never-ending walls, and gigantic perpetual portal rooms,” writes CrowbCat. “Scary at first when you’re face to face with yourself. Such visuals potentially can trigger anxiety about mirrors and stairs to some people. There is no way to get out without restarting or using cvars. Chell doesn’t die by doing this, and it looks like there’s no gravity anymore.”

But the kaleidoscopic visuals provided by this perpetual glitch-world aren’t the entire highlight of the video. CrowbCat removes the game audio, adds the mysterious notes of Self-Esteem Fund—one of the quieter and more contemplative songs of the Portal 2 soundtrack—and then cuts together a beautiful series of wormhole art. The obvious touchstone to compare it to is the wormhole scenes in Interstellar (2014). But in tone it more closely echoes the thought-provoking slow-takes of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solyaris (1972). Either way, it’s a mesmerizing way to spend a couple of minutes.

Meditating on Kentucky Route Zero

The first moment that Kentucky Route Zero (2013) throws a surreal curveball at you feels like a wake-up call. A character you’ve just met has finished fixing a TV, which doesn’t focus the picture on the screen as you expect, but somehow switches the barn outside the nearby window for a cave entrance. The transition is hard to grasp—a sleight of hand trick that holds up under scrutiny. As the camera zooms in, the edges of the entrance smudge against the landscape, unconnected to anything, like a hole has been painted into the scenery. A truck pulls in front of the cave—the characters driving it being your only remaining anchor to reality—and goes straight in, disappearing from view. And that’s it. It’s over. The moment remains unexplained, sending a clear message that this is not a game where you search for your answers and find them. The game demands that you meditate on them.

///

Headspace is a guided meditation app designed by a former Buddhist monk. I tried it out over a year ago and was surprised to find that it drew me in immediately. You learn early on in your journey with it that meditation is not about unlocking a zen state of oneness with the universe, or about clearing the mind. Conversely, it’s about mindfulness. You sit down and take slow, deep breaths before closing your eyes, then you notice the sounds around you and the weight of your body on the chair. The idea here is to be present in the moment, meaning you’re not actually thinking about any of these things, but taking the time to notice them, to feel them as you’re prompted to “settle into the space around you.” The same idea carries over to noticing the presence of the mind.

With guided meditation, you’re next given prompts to “scan the body” and “focus on the breath.” These prompts are designed to steer you away from analysis, because while you’re observing the physical body, it’s easier to do the same with your thoughts. The misconception is that meditation is a way to clear those thoughts, but it explicitly encourages you to let them come and go, instead of being distractions. One metaphor Headspace uses likens ideas stirring around your mind to cars driving down the road. Meditation is simply watching the traffic. You’re not chasing after the cars—or letting your thoughts carry you away—but noticing them as they go by.

The car metaphor is particularly appropriate here, as Kentucky Route Zero tells the story of a truck driver named Conway who’s trying to deliver a package to an unusual address on an unmapped road. The world gets stranger as you accompany Conway along the enigmatic Route Zero, like if Samuel Beckett wrote Heart of Darkness (1899). At first, it’s a bleak world of abandoned homes and financial struggle. Soon enough there’s an office building full of white-collar types bureaucratically repurposing buildings, including one floor full of bears (helpfully labeled in the elevator as “bears”). Later on, Conway encounters one of those repurposed spaces: a church converted into a bourbon distillery, staffed by ghostly skeletons making barrels shaped like coffins. At first pass, there appears to be little in the way of rhyme and reason in Kentucky Route Zero, its events bobbing and weaving in unexpected and unquestioned directions. You might ask yourself how you’re supposed to make any sense of it while you play. In response to this, some describe the game as “meditative.” What that term necessarily means may lead to confusion. But my short time meditating has informed my understanding of its connection to Kentucky Route Zero.

Meditation is time you spend ostensibly doing nothing. Headspace is very clear that you are not to be eating or listening to music or anything when you meditate. But this nothingness is used to find presence in the moment, leading to calmness in your thoughts and feelings. Kentucky Route Zero employs a similar emptiness and slowness to make sense of its characters’ abstract, melancholic world. It is principally an atmospheric experience that asks you to interact with, talk to, and notice the world around you. While I was learning the techniques of meditation and finding out what “settle into the space around you” actually felt like, I noticed parallels with how Kentucky Route Zero draws you into its own spaces, making its oddities enticing rather than alienating. Your purposeful, slow exploration of an expansive off-site storage facility-cum-church helps you process the full extent of how strange such a location is. Shortly after, you talk with a young boy whose brother is apparently a giant eagle that moves buildings in and out of a museum for a living, yet it is the delicate conversation you have with him about his missing parents that offers emotional grounding in that odd moment. Meditation is designed to help shed light on your thoughts without getting lost in them, and what Kentucky Route Zero does is adapt these same methods to take a player through someone else’s thoughts. Meditation appealed to me as a way to confront my problems with anxiety. It makes sense that a game that co-opts its techniques can then more intimately confront the anxieties of others.

notice the fleeting impermanence of moments

Since there’s no feedback or measure of your progress, newcomers to meditation often worry that they’re not “doing it right.” It’s easy to feel the same doubt when playing Kentucky Route Zero. The game plays out through a series of dialogue choices, but these don’t allow you to influence the plot. The purpose of these choices instead is for you to find awareness in someone else’s moment, like achieving mindfulness by proxy. Despite the absence of any possible failure with the choices you make—the story continues regardless of what you choose—it’s still not easy to pick the best dialogue options. Sometimes your task may be as simple as commenting on the sunset instead of asking for directions. Or it could be asking for help finding a package’s destination or asking for someone to tell you about their life instead. At one point, while playing as Conway after having an accident, you have the choice between stating that you think you broke your leg or that you feel fine. There are many moments like this where it’s easy to freeze and fret about what your choices could mean. But what’s more important is that in a game and story filled with elusiveness—in terms of both narrative and agency—the point isn’t to dwell on choosing the right decisions, but to notice the moments presenting them and feel out the decision that seems right to you. Meditation asks you to let your thoughts come and go, encouraging you to notice the fleeting impermanence of moments, and through its pseudo-chaos theory of unmade choices, Kentucky Route Zero envelops you in them. Awareness of the moment becomes how we understand it, even if the big picture remains a mystery. Both Kentucky Route Zero and meditation want us to value finding meaning in that mystery.

In one scene, you drive Conway’s truck and pass a guitarist on the side of the road. You’re given the choice to put a dollar in his cup. If you do, he pulls it out and hands it back to you, now wet with whiskey. The impulse might be to analyze your reaction to this; to decide if it was okay to laugh, to weigh your guilt, to search for hidden meaning in the scene. Or, to go back to a previous metaphor, to chase the cars. But this isn’t how you derive meaning from meditation and it isn’t how Kentucky Route Zero reveals meaning either. Noticing the reaction you had to that moment gives the scene a certain clarity that trying to analyze it might never be able to. If meditation teaches us to be mindful of our existence, meditative qualities in games could make us mindful of existences we might otherwise never be able to experience.

February 8, 2016

Firewatch: Come for the beauty, stay for the eeriness

Firewatch gets it. Beauty alone isn’t enough to carry an experience. There needs to be some grit, a bit of dirt, conflict even, to elevate a videogame (hell, any piece of art) from the whimsical to something more. I have a problem with 2009’s Flower and 2013’s Proteus precisely because there isn’t anything to offset that serene beauty, their new-age hokum. But in Firewatch, no matter how gorgeous that sunset or night sky is, there’s always a thick sense of dread. Something to unsettle you. Something to make you tense up. I’m not talking bump-in-the-night, Blair-Witch, voodoo nonsense either. Forget the horror stories we told one another at high-school before those weekend camping trips. The Wyoming wilderness that Firewatch quite brilliantly captures is uneasy, eerie in its quiet.

I felt like I was being watched throughout the whole thing

You are a fire lookout called Henry. And you are, for the most part, physically alone in Firewatch. There’s Delilah, your lookout colleague, but she’s stationed across the valley, communication maintained via your radios. And sure, there are those prototypical skinny-dipping teenagers, but they appear as silhouettes in the distance, and nothing more. So it’s mostly just you and Delilah. And while she may be your remote companion even she’s not always a reassuring presence. She’ll guide you from her fire lookout; she’ll know where you’re at, what you’re doing, but her omniscience is disconcerting. It’s antithetical to the solitude you expect from the wilderness.

But it’s not just Delilah that breaks the spell of solitude, it’s the lookouts themselves. They’re alien structures that loom out of the rock formations, interrupting the Wyoming idyll with a kind of surveillance dread. I felt like I was being watched throughout the whole thing; Delilah’s cabin across the way was a constant reminder. The analogue wavelengths of Henry and Delilah’s radio chatter lope across the cliff faces, ripe for interception. Notepads, too—a means of recording—surface with unnerving regularity in the Shoshone wilds. These are anomalies in the landscape, contemporary human remains at odds with the deep history of the place.

These artefacts, along with the story, ensure you have a reason to keep hiking those mountain trail paths. I was worried Firewatch might slip into a bland veneration of the American landscape, or never move beyond its cabin-porn imagery, but thankfully this is not the case. It’s gorgeous, sure. You will, as I did, stop and gaze at the natural beauty of the place—the burnt out haze of the evening sun, and those shimmering night skies. These are already available to you, though, in the copious screenshots and playthroughs of the game that already exists. The real joy lies in the dark secrets those mountains and forests hold.

I’m going back for more Firewatch now, but it’s the eeriness that keeps me there, not the beauty.

Firewatch comes out for PC and PlayStation 4 on February 9th. Find out more on its website.

Eastshade will let you paint its idyllic landscapes as you explore

Hark, another open world, first-person game in which you traverse picturesque natural environments!

That is both slightly unfair to Eastshade, a PC game that is currently in the making, and factually beyond reproach. Eastshade, as with many games before it, is all of those things, but it is also endearingly meta. You play as a painter who wanders through natural vistas in search of inspiration. That shouldn’t be too hard to come by, as the game offers stunning visuals, but there is still the not insignificant matter of framing. As you go about your business, you can stop to paint a portion of what you see, and those paintings can then be used to ply other characters for favors or physical goods.

Eastshade is a curious entry into the “are games art?” debate. It is not making an argument about the artistic merits of games per se, but the fact that the game’s universe can quickly be transformed into a painting is still telling. If the universe becomes artwork (in the traditional sense) when it’s put in a frame, isn’t that what it always was? Conversely, if you need a frame to think about a game’s visuals as art, what does that say about you?

we all live within paintings

In that respect, Eastshade is attempting a similar trick to Mike Leigh’s film Mr. Turner. In that latter work, the line between film and J.M.W. Turner’s paintings is regularly blurred. Outdoor scenes have the same thickness as the English romanticist’s works—and are only flecked with slightly less spittle. (Tom Hooper’s The Danish Girl occasionally goes for this trick as well but, as with the rest of the film, it comes up well short of the mark.) All of these works suggest—with various degrees of success, granted—that we all live within paintings. The role of other works, then, is just to make that reality apparent.

The beautiful destruction of old-school malware

Malware. Blech! We hate malware. And so we should—deleting files, maliciously clogging up our desktops, turning our browsers into never-ending adverts. But it’s so boring and irritating these days. At least back in the 1980s and 1990s you could take a step back and admire both the technical and artistic achievement of malware before it ate your computer.

If you’re not familiar with the malware of yesteryear then, fret not, you needn’t miss out. The internet archivists at archive.org have teamed up with self-professed “malware adventurer” Mikko Hypponnen to provide The Malware Museum. It’s a collection of malware programs that were made during the penultimate two decades of the last century to infect home computers. You’re able to view the animated effects and messages that would display on your screen as these viruses entered your computer and started ripping their insides apart. Importantly, The Malware Museum has quarantined (removed their destructive properties) the viruses and lets you run them through an emulator so you can view the show without your computer being at any risk.

“coding a virus can be creative”

What makes the malware of the ’80s and ’90s worth revisiting is that it was mostly created to experiment and play pranks. Sure, it may have been collapsing peoples’ entire personal contents on their PCs but there usually wasn’t much to it beyond that. Compare that to these days, with malware mostly being used by companies and governments to spy on people or nick their personal information (read: wreck their lives), and the malware of old seems quite innocent—just some hackers having some fun.

This more playful era of malware saw their creators wanting to show off their skills, taunt their victims, and sometimes even play games with them. Not much of the subtlety of today’s malware was present. Instead, it would announce itself on your computer like the jovial ringmaster for a doom circus. Colors and letters would scramble across the screen such as in the image above from CRASH. The word “ha!” was written in ASCII as if to display the malware creator’s joy in having scored one of their unknown prey. Text might scroll in the style of the crawling Star Wars intros. Some scream at you, some drew images, others were impressive displays of coding skill.

One of the malware programs, called MARS G, captured the spirit of malware creators back then, it showing you a scrolling 3D impression of the red Martian landscape, with the message “coding a virus can be creative” written in text at the top. The creators of old-school malware turned their hostile software into an art form as they explored the creative possibilities of taking over someone’s computer. It even went so far as turning malware into a game, such as Disk Destroyer, which steals all your data and then gives you a chance to get it back by playing slots. You get five credits to spin the reels, and if you match three pound signs you get your disk back, or if you match three question marks you get hacker’s phone number. Otherwise you lose the game and all your data with it.

What’s less obviously remarkable about all this malware is the technical feat behind them. This is something that Hacker News user “luso_brazilian” puts into perspective:

“Back in the days a lot of thought and ingenuity was put into making these viruses. For instance, the Friday 13th virus:

* was only 419 bytes long

* infected both .COM and .EXE, increasing the size of the former by only 1813 bytes

* on infection, became memory resident (using only 2kb of memory)

* hooked itself into interrupt processing and other low level DOS services to, for instance, suppress the printing of console messages in failure cases (like trying to to infect a file on a read-only floppy disk)

* activated itself every friday 13th and deleted programs used that day

It still managed to spread itself worldwide (mostly via floppy disk sharing as the world wide web didn’t exist yet) and went mainstream enough for the broadcast news to advise people not to turn on their computers on that date or to push the date one day ahead.

All that in 419 bytes, about a third of the size of this post.”

You can check out The Malware Museum for yourself to see the rest of the presevered viruses.

Burn in hell, Yarny

A videogame called Unravel will be released tomorrow. It may be a good game, and it is certainly a good-looking one, with a soft focus and hazy depth of field; tree leaves rustle convincingly and thick snowflakes pile up as the camera pans ever right-ward. It appears to make use of this tactile world for a series of physics-based puzzles, like moving rocks to get up on ledges and creating makeshift vines with which to soar across little ponds. These may be very clever puzzles, building toward a resolution that is very satisfying, but I will never know, because I will never play Unravel, and that is because its protagonist, a little red yarn-man named Yarny, can go fuck himself.

the commodification of childhood

Now, I’ve used the masculine pronoun to describe Yarny, but this may be entirely inadequate. The game’s designer, Martin Sahlin, has said that Yarny represents nothing less than “love, and the bonds that we make. And it unravels”—get it—”because that’s what happens when we’re separated from what we love.” Well okay, sure. I’m not gonna shoot spitballs at the metaphor here, it all sounds very nice. Another video of the game, purportedly debuting the game’s story, briefly shows an old woman looking at a photograph. Other videos show the little yarn man bouncing through the forest to somber stringed instruments as images of childhood appear and disappear behind him. So: we will experience the old woman’s life and at the end there will be a delicate yarn metaphor. Okay!

I’m fine with cuteness—I am a cat person. My issue with Yarny is that he doesn’t represent love but instead the commodification of childhood and emotion as some sort of antidote to “popular videogames.” Sahlin set the stage for Yarny’s reveal last year by introducing Unravel with the “need to do something more than entertain,” saying it “was born out of the need to make something more personal, something with a heart.” This is an increasingly common, and troubling, sentiment in interactive art: that somehow emotion is an end unto itself, and diametrically opposed to the baser pleasures of entertainment, rather than a byproduct of it. We see this consistently, in particular, in virtual reality, which trawls through disaster pornography and blithely important “empathy projects” as a means to use the technology Seriously, rather than for earthier, more human pleasures.

Yarny, then, is a mascot for this false binary. 2014’s Child of Light trafficked in the same storybook sentimentalism, and I suspected at the time that it was putting air-quotes around the experience of being a child; it was a children’s game made for adults to play and chortle and sigh at. Yarny is that sentiment crystallized, turned into a marketing plush—a sort of dark-universe Mario, who would sacrifice “fun” at the altar of “emotion,” thereby reinforcing the false binary that says you’re either dumb or you feel things. Fan art, of which there is a lot, frequently paints Mario and Yarny together, but this makes no sense. Imagine these two sharing a world: Mario would set that motherfucker on fire and keep on running. Mario has shit to do. Yarny just wants you to cry. Fuck Yarny.

The aliens in Somerville definitely don’t come in peace

“If aliens ever visit us, I think the outcome would be much as when Christopher Columbus first landed in America, which didn’t turn out very well for the American Indians.” That quote belongs, unfortunately, to one of the greatest minds of our age, Stephen Hawking. It’s not an uncommon sentiment, of course; popular entertainment has been driving home this idea since Orson Welles’ famous War of the Worlds (1938) broadcast. And it’s Welles that has clear influence on the visuals of Somerville, an upcoming sci-fi game: huge black monoliths loom over a rural community, spitting out all manner of neon terrors to hunt down the populace.

Somerville is to have an episodic narrative—perhaps not the only parallel its makes with Kentucky Route Zero (2013)—about John E. Somerville, an author who rises to prominence over the course of an alien invasion. The game is being developed by Chris Olsen, formerly an animator for feature films, games, and television. On this project, he wears many hats, including lead designer and writer, but the development blog is full of lovely examples of kinesis. Look at the way these little alien drones bob and zip through the air:

Or watch the way this grazing deer is startled, before taking off:

Olsen clearly has an eye for detail when it comes to bodies in motion. It’s a skillset that suits the platformer well, meaning that with his crack animation, Somerville shouldn’t only look good, but feel good too. Look at the way the gravity, momentum, and character-oriented physics come together in this jump:

That shit’s hypnotic. I could watch it all day, so I’m definitely looking forward to getting the chance to dive in and move around.

Somerville doesn’t have a release date just yet, but you can follow its development on Olsen’s blog here.

The Division doesn’t want you to think about 9/11

When I entered Ubisoft’s The Division press event on February 2nd in New York, I was greeted by a display of an NYPD patrol car that had crashed into a lightpost, with smoke bellowing from its engine and its lights still flashing. Machines in the rafters vigorously blanketed the room in snow. Caution tape separated visitors from the staff-only areas. A street marker for Madison Avenue with a “Closed” sign attached to it overlooked the game’s demo stations. A Do Not Enter sign sat in the distance. I had entered a New York that felt like it had been thrown into chaos.

For New Yorkers, imagery like this still hangs in the recent past. For how much it’s affected global affairs, September 11th, 2001 is a very local, very painful memory here. I have close personal friends who saw the damage, the loss of life, and the heroism of the first responders that day with their own eyes. After ISIS recently made threats against NYC, they told me how these memories still haunt them and that they don’t want an attack like that to happen again. As terrified as I was sitting in a classroom in Indiana that day, the people here felt the fear of what might happen next deeper than anyone else in the country. Ubisoft has become known for recreating real-life cities in virtual space, but The Division comes with the added challenge of tackling how New York City responds to terror.

The event itself kicked off with a 1.5 hour panel from the game’s lead designers as well as a few survival experts. Most of its time was dedicated to selling us on how supposedly “plausible” and “realistic” the game’s scenario of a Black Friday smallpox attack spread using infected paper money was. The attack wasn’t confirmed as being terrorist in origin, but the implication was there, and regardless, the results were similar. We were bombarded with statistics about how most Americans don’t wash their hands after handling cash and about how much money in circulation today has trace amounts of Anthrax on it. Expert testimony was a centerpiece here, but only in regard to how ‘innovative’ and ‘clever’ the game was being in its realism. As if imagining New York under attack were a new idea.

For all this time spent explaining the game’s setting, my time actually playing The Division failed to capitalize on it, feeling much more like Destiny (2014) grounded in modern times than the creative ruins of I Am Legend (2007) or Escape From New York (1981). The Manhattan Midtown I was shown was essentially the same as the one I know now, only with fewer people and more chest-high walls. I was lead through this drab take on my now home by a developer who didn’t want me experimenting with the game too much. As I tried to break and test it in as many ways as I possibly could, I was shepherded instead towards corridor shooting where I fought large gangs of looters, my military training and equipment making my opponents seem drastically inadequate in comparison. My enemies were New Yorkers struggling to survive in the wake of danger and I was spending my resources shooting them down rather than saving them. Was I really the rescuer here? I had all this money to spend on riot shields and holographic displays, but not on food for people so in need they were braving Smallpox-infected streets. But the looters were wearing bandanas over their faces and speaking in slang, as if that justified their deaths.

For New Yorkers, imagery like this still hangs in the recent past

When I was offered the chance to stop playing and interview one of the game’s designers, I was relieved. My eyes had glassed over while I was staring at the screen, and a quick glance around the room drew me back to reality.

“So when you have a disaster scenario set in New York, the obvious comparison is to 9/11,” I mentioned to Julian Gerighty, the associate creative director for the game. I wanted some basis for why the game was set in such a touchy area given its subject matter. “I know you spoke to survival experts about the realism of the game’s scenario. Did you talk to first responders or other people who were there during 9/11?”

“I didn’t,” he responded. “I don’t think even the parallel between this game scenario and 9/11 exists.”

I was a bit surprised. Surely, I couldn’t have been the first person to draw this comparison, right? “So you didn’t take September 11th into consideration when making the game?” I asked.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever been asked about it, and it hasn’t really crossed any of the meetings that I’ve done on it before.”

When I pressed further on the game’s themes, whether it was the inherent anti-capitalist message in centering the game around a virus spread through money, or the draconian justice of armed peacekeepers indiscriminately shooting down looters and escaped Riker’s Island inmates (another class of enemy in the game), he told me, “At the end of the day, it’s a videogame, it’s an entertainment product… There’s no particularly political message with it.”

But works of art aren’t made in a vacuum. They can never be entirely free from their creators’ assumptions. In its premise, The Division brings up a number of fruitful topics that could be entire games of their own: Dealing with the fallout of a terror attack in New York. A virus spread through cash on the biggest shopping day of the year. Turning Times Square into a player-vs-player meat grinder called “The Dark Zone.” Insisting on a cynical version of a New York under siege where people in need roam the streets murdering each other instead of helping. And then there’s the Division itself, a group of autonomous sleeper agents living normal lives who activate in times of great need and have the authority to restore order with no restrictions, Constitution be damned. This is based on NSDP 51, a real-life continuity-of-government plan set forth by George W. Bush, the majority of which is classified. The Division speculates it might look something like the eponymous organization within the game. The civilian hero aspect at play here is almost like a twisted take on a first responder, like a volunteer fireman who puts out fires less by blasting them with water and more by waging war against arsonists.

Not wanting to confront these themes doesn’t make them any less apparent in the text, just as not acknowledging that I’m wearing a red shirt doesn’t make it any less crimson. This means that The Division approaches heavy subject matter with all the subtlety of a 16-wheeler, casually tossing around imagery that a good deal of people associate with pain and loss while not paying it due diligence. Maybe, in the name of fun, this is acceptable. Maybe the implications being made here don’t matter, so long as players enjoy themselves. That’s certainly what I was told. But if Ubisoft was so excited about this game’s story that they felt the need to focus on explaining it to me for over an hour before I even got to play the game, it’s clear that they care about it at least somewhat. If it didn’t matter at all, they wouldn’t open with and give an extended breakdown of it. In emphasizing the realism of the setting they had invented, the development team clearly put no small amount of effort into researching how accurate it was from a survival scenario perspective. But this only highlights the comparatively light research put into New York’s already fervent, if tragic, history with attacks like this. If The Division cares as much about realism as it claims, why not focus more on what is unique about the city it has chosen for its setting?

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers