Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 161

February 17, 2016

The videogame equivalent of Monty Python and the Holy Grail has arrived

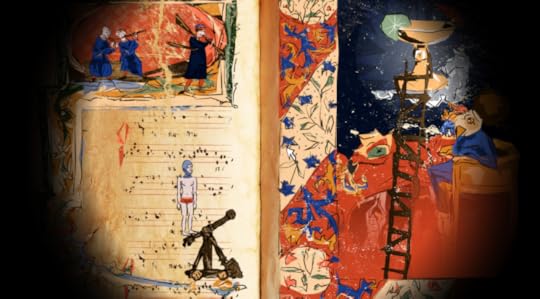

The Kickstarter for a videogame called Lancelot’s Hangover has gone live today. As a parody of the King Arthur myth of the utmost sophistication—including drunks and rapping bears—it demands a rigorous examination of Arthurian literary history. That means it’s time for a crash course in Arthurian literature—go!

King Arthur narratives have gone through a number of unique iterations over the years. Originally a Welsh figure whose brave exploits were described at length in writing and through the oral tradition from around the 7th century until the 11th century, Arthurian stories were popularized by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae (1136), or History of the Kings of Britain. In this work, Geoff chronicles a highly romanticized and fanciful version of the King Arthur tale.

relentless silliness

The 12th century French author Chretien de Troyes decided that the hero in this story didn’t have enough of a posse—thus the addition of the Knights of the Round Table—and lacked a distinctly religious ambition—thus the quest for the Holy Grail. He also decided that Arthurian literature wasn’t saucy enough and introduced Lancelot, who seduces Guinevere into cheating on her beloved (800-year-old spoiler, sorry). From here on out, Arthur found himself increasingly pushed to the sidelines of his own stories.

In more modern adaptations, Arthurian literature is tempered with contemporary concerns. Alfred Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1859 – 1885) and similar works use Arthur as a role model for Victorian concepts of chivalry. In the 20th century, T. H. White uses the lore as a means to tackle relevant themes such as war, power, and justice in The Once and Future King (1958). Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon (1982) gives the tradition a much belated retelling from the women’s perspective. But most significantly, Monty Python finds that the legend severely lacked enough butts and non sequiturs and creates Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). And now, from this incredibly rich and complex tradition, solo game creator Jean-Baptiste de Clerfayt has been inspired to create Lancelot’s Hangover. Phew, take a deep breath.

The premise of Lancelot’s Hangover is simple. God commands Lancelot (“the sexiest Knight of the Round Table”) to seek the Holy Grail in the most treacherous, sexually confusing place in all of Europe: the Kingdom of France. Once Lancelot has claimed the grail, he is to put booze in it and put on the greatest party in England. Now you may be asking: Why, out of all that sophisticated history you just spent half the article explaining, did Jean-Baptiste de Clerfayt decide to pull from the most juvenile of the whole lot? Well, because it’s amazing, that’s why.

Monty Python humor is notable for its relentless silliness. At times even to its detriment, the comedy troupe stops at nothing to create more and more ridiculous sketches, gags, and bizarro world asides. Yet despite their seemingly nonsensical approach to comedy, Monty Python is actually quite intelligent beneath the surface. While brimming with sex jokes and comical murder, Monty Python and the Holy Grail actually knows their source material through and through. They play with concepts of medieval chivalry. They mock holy men, plague-worn peasants, and witch hunts in equal measure. In knowing the subject of their ridicule so well, they are able to make the most delightful jabs at it.

Medieval manuscript art came to mind

Lancelot’s Hangover aims to live in the shadow of Monty Python but also takes from other sources. Clerfayt cites inspiration from Monkey Island for its point-and-click adventure format; he cites South Park for its politically incorrect (though, he notes, in no way malicious) humor; and finally cites Arthurian legend as its background. Three out of these four pride themselves on silly humor. So, yeah, sorry Arthur. To be fair, we are already over-saturated with self-serious King Arthur stories. Lancelot’s Hangover aims to stick its tongue out at all those grim faces and pokes fun at the somberness of much of the tale, bringing the ridiculousness up to 11.

“I’ve always been fascinated by this story,” Clerfayt explains. “Why do the Knights of The Round Table go find the Holy Grail? Because God wants to! No more reason needed. It was, for me, the best setting for nonsense humor. Why is everybody gay in France? Because God commands it! Why does a Nouvelle-Vague minstrel do gangsta-rap with a bear? Because God wants it to!”

The Arthurian story and setting actually arose by an artistic decision. In the beginning, Clerfayt knew he wanted to make a 90s point-and-click adventure tribute. He didn’t know how to go about approaching the game visually and contemplated what he could best achieve without exerting all his energy into the art. Medieval manuscript art came to mind, specifically that of the Bayeaux Tapestry—a famous embroidered cloth which records the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England. The reasons for this inspiration are numerous. Living with a father and sister who were medieval history enthusiasts was the first of these. Coming from a medieval Belgian town was another. But, most of all, Clerfayt knew that medieval manuscript style is easy to draw—you don’t need to worry about shadows or perspective. Hence he dove in through this art style and pulled the Arthurian myth out.

It’s a big undertaking, with Clerfayt being an almost one-man show in this enterprise. Coding, storywriting, puzzle design, graphics, animation, promotion, and PR, are all being done by him. The exception is the music, which has been composed by Brandon Fiechter. Fitting with the Monty Python approach to Arthurian legend, the soundtrack consists of traditional medieval English music filtered through chiptunes.

A Kickstarter campaign for Lancelot’s Hangover is currently underway. Find out about it here .

Hands.wtf is the latest inexplainable internet treat

The Internet needs more jazz hands.

That’s what Stinkdigital’s hands.wtf is for—if it has any real purpose, that is. “We created for no good reason at all,” the creative agency says. But here it is: two hands—Killer Mike and El-P are the credited hand models—floating in digital space. Type in a 3-letter word, the game compels you. Each letter brings up a different hand. Some appear to be plated with nickel, others are sheathed in red crocodile skin.

try to guess all the words

The hands spin around, their fingers extended as if a child was about to trace a hand print. Type in one of 37 pre-coded words, however, and the hands make special celebratory gestures. Those motions can be downloaded as gifs, which are basically trophies. If you want to make a game out of hands.wtf, you can try to guess all the words.

There is no need, however, to give this exercise a goal. Sufficient pleasure can be derived from simply typing random strings in hands.wtf. Each letter brings its own graphics and sound. You can therefore treat the keyboard as a soundboard, an unorthodox instrument to be played towards no particular end. Hands.wtf’s extremities don’t do sign language in the traditional sense—letters do not trigger symbols—but they do give you signs when you’re doing well. Like a date, the options are binary: impassive stillness or excitement. Try it. Stinkdigital has created jazz hands for the Internet.

You can play hands.wtf in your browser.

Between Me and the Night makes childhood last forever

The past can be an unclear place—definable through facts, yet easily clouded by emotion. Whether from nostalgia, personal interest, or error, humans have a pronounced ability to mis-remember or poorly represent their own history. In a sense, this defines us: as a populace, we live with the potential to build our lives on a set of experiences which may not be quite as precise, or as true, as we might want them to be.

It is typical for creators in any medium to draw on the experiences that shaped them when they were young. We tend to mythologize the art objects that set us on a path early in life, whether this is expressed as a filmmaker imitating the styles and rhythms of 70s movies, or as a game designer appropriating a crude, low-poly look similar to what she played as a child. Often, this act of remembering ends at style; we are not always asked to think about what feelings those styles bring out of us, or how. Few videogames have been crafted so totally around the phenomenon of remembering as Between Me And The Night. It uses a puzzle/adventure framework to say intimate, sometimes sophisticated things about the complex relationships we form with our past selves. It’s an attempt to speak to each of our individual experiences of growing up through a universal language. That proves to be as difficult as you’d imagine.

Between Me And The Night asks you to follow its main character from childhood to adulthood, discovering the roots of their fears and anxieties. Though its puzzles are procedural, their core is always in discovering whatever has made this character feel the way that they do, and perhaps why these feelings continue to linger on for so many years. This might read as dreary, but the first-hand experience of playing Between Me And The Night is warm and inviting—even at its most emotionally thorny, the game maintains a sense of humor and slightness. From the hand-made impression of its art design to its call-outs to cultural touchstones it assumes you will recognize, the game wants to appeal to you as a peer and draw you into its world on a personal level. (To get much more specific than this would possibly spoil the game’s unfolding sense of discovery, which is best enjoyed as it spools out.) Between Me And The Night is by held together by the clear passion and enthusiasm its creators have for telling this story, and their sense of care for this world is infectious.

For a protagonist, we are given a boy from a well-to-do suburban background. His experiences are built on large houses with bedrooms full of toys, a high school with a photo lab, a cramped apartment lined with posters for The X-Files (1993-2002) and Kill Bill (2003). I point this out because, to an extent, this game is ruled by its environmental details, and the objects that fill this character’s life do much of the work to explain who he is. When a puzzle is based around getting a Game Boy to work (as a way to unlock an 8-bit retro mini-game), or finding a complete collection of Power Rangers (1993-present) stickers, the game seems to know exactly who it is speaking to—a generation, from a specific background, that romanticizes certain toys and games as oases in what might otherwise feel like an unstable world.

The past can be an unclear place

Often reaching for a narrative logic that is aligned with imagination and dreams, the game’s creators at Raindance Lx capture the overwhelming emotions of youth with accuracy. This logic arguably reaches its most interesting expression in the interstitial levels, between chapters, in which the protagonist’s point of view fully merges with one of his videogames. These moments tip Between Me And The Night explicitly into fantasy—or, at least, the aspiration toward fantasy. Dressed up as a knight, slashing at enemies, we get a sense here of how powerful the pull can be to escape from the accuracy of memory: that to pretend being a Video Game Hero, to surround your life with an imagined Epic Experience can be a balm for what is often internalized as personal pain. The real tragedy comes from the sense that this happens at the expense of doing the hard work of being good to yourself and to others, of living a full life in the real world, intelligently showing the ease with which a fantasy life may feel preferable to accepting the pressures of personal growth.

In fact, one of the biggest successes of Between Me And The Night is in the way it describes the real world as unfriendly. If there is a villain in this game, it is the protagonist’s surroundings, which are constantly changing from one of security to one where danger seems unavoidable. Everyday situations and objects become landscapes for violence: one puzzle early on depicts the family cat as a giant monster that will claw you to death if you get too close. Once it is placated, the cat shrinks back down to size, showing its beastliness to be a projection of the main character’s own fears. The game also cycles continuously between day and night, and with nightfall comes the appearance of monsters throughout the playspace. The sense of exposure from being hunted through one’s home is strong, doing much to develop the game’s sense that the confusions of youth are themselves a dangerous place to exist. Augmented by detailed, impressive sound design (the feeling of doom at hearing a monster’s footsteps in the hallway outside while hiding in a “safe” room is powerful), these particulars underscore how real emotion can be conveyed with the mix of imagery, sound, and interactivity that is specific to games. Among the most typical for a videogame, such passages also feel the most fully lived-in.

Playing as a child, you are mostly helpless against these threats; as a teenager, you find ways of appeasing them; and then, as an adult, your only method of survival seems to be through escape. This is an elegant metaphor for the ways in which personal traumas hold on over time, slowly forcing us to adapt to their rhythms. What is experienced in childhood as terror becomes, with age, merely pathetic. The word “age” here is specific, because even though our main character gets older, he never seems to fully mature. Rather, his experiences gather on top of him in layers, insulating him from reality as he slouches reluctantly into adulthood. He winds up surrounding himself with the same toys you collect in the first passage, the nostalgia sanded into something recognizable, yet less meaningful.

In charting the growth of a boy into a man-child, Between Me And The Night seems deliberately ambiguous as to how desirable this change is. I’m split as to whether the game’s depiction of escapism feels critical or supportive of this approach to adult living, or if it is somehow both. To wit, at times Between Me And The Night seems laser-focused on getting you to ache for the sadness of its world. But, in other moments, this same escapism is used to justify, or at least explain away, less desirable adult behavior. The character ultimately becomes the definitive softboy—six unlistened voicemails and all—and the game can’t decide whether to fear or pity him for this.

the game can’t decide whether to fear or pity him

What is decisive is that, at its weakest moments, the game can feel as if it is presenting its choice of specific life experiences and family background as too universal. An air of “this is what we all go through, right?” hangs over much of it, and I wonder to what extent this might estrange certain players for whom this character is too loosely defined. Atmospheric traumas might read as much like the privilege of a certain upbringing as the Matisse print hanging up in the protagonist’s childhood home. That said, Between Me And The Night never feels less than sincere and heartfelt while doing this. And if you can embrace its perspective, the game stands to offer a moving and smart depiction of navigating life through the scrim of an angst born in childhood.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Night in the Woods to unravel its angsty teen tale this fall

There are two types of stories we tend to tell in the Fall: scary stories, and stories aimed at winning awards. Night in the Woods wants to be both.

First announced with a Kickstarter campaign on October 22, 2013, Night in the Woods was pitched as a clever sidescroller twist on the adventure game, which quickly attracted attention from eager fans as they helped it earn over $150,000 dollars beyond its set goal of $50,000. The project was also warmly received by critics, who dug its young-adult angst, muted woodsy environment, and light horror themes. Kill Screen’s own Davis Cox went so far as to say that it “picks up where Gone Home left off.” According to a February 8th Twitter thread on the game’s account, it won’t be long until we find out if it delivers on that promise.

“Night In The Woods will be released this fall,” the game’s Twitter writes. “Date to be announced. Later.” Along with a cute gif of the game’s lead character rustling some autumn leaves as the word “FALL” fades into the background, the rest of the thread follows up the announcement with shareable wit and commendable bravado. “Tell your friends, tell your enemies, go into the woods and yell it at the trees,” we’re told. “‘Hey, isn’t fall when all the big games get released? Aren’t you worried about getting lost in the shuffle?’” ask rhetorical doubters. “Well, that’s kind of up to you now, ISN’T IT?” Night in the Woods replies, calling us to action.

The team is clearly aiming big

The team is clearly aiming big, hoping to capture the same kind of independent zeitgeist that last year launched the likes of Undertale and Cibele to compete with Rise of the Tomb Raider and Metal Gear Solid V for Game of the Year titles. Big games don’t have to come from big studios any more, and Night in the Woods knows this. They just have to have big ideas.

But are Night in the Woods’ ideas still big? When Gone Home was first released in August of 2013, it shook up the adventure game market by paring down the genre’s familiar comedic and epic questlines to a personal story about a young woman’s self-discovery. This was set alongside tense allusions to mild horror in a secluded Oregon cabin, while also drawing the player in with non-violent, fully-explorable first-person scavenger hunts. In this way, it makes sense how Night in the Woods, with its sidescrolling, apathetic teenage misfits and forested secrets, felt like a successor to that same creative spirit. Both games ask questions about young self-identity, and both put forth new ways for the player to interact with the story.

But in 2016, Night in the Woods is now joined by the time-travelling shenanigans of Life is Strange‘s awkward Max Caulfield, the freewheeling dialogue of Oxenfree’s bitter teenage gang, the choose-your-own-haunted house wilderness of Until Dawn’s petulant assholes, and the middle-aged crossroads and walkie-talkie confessionals of Firewatch’s amateur woodsman, Henry. I could go on. None of this is to discredit Night in the Woods. By all accounts, it seems set to tell a compelling, personal, slightly spooky story about young self-discovery in the forested outskirts of a dilapidated town while questioning how exactly adventure games should play. But competition in this area is stiffer than it was even three years ago. David Lynch’s children are many, and young-adult games are quickly gaining popularity to match their filmic counterparts.

Videogames and Tarantino: A mistaken love affair

Whether you like his work or not, Tarantino has a grip over the collective imagination many creators can only live out in their dreams. Take this year’s The Hateful Eight for instance. So much attention has been given to the mere possibility of a new Tarantino project that the film’s first script was leaked, the early screener pirated, and later, the pirates even apologized for releasing the film early because they admired it so much. Despite all that, the three-hour long The Hateful Eight managed to convince people to fill theater seats and watch a film in an antiquated format (70mm), in an equally antiquated throwback roadshow.

People hope for Quentin Tarantino to grace every aspect of popular culture, and for the most part he has obliged. He has made comic books, directed television episodes, and is adapting his newest film for the stage. Despite such an eclectic portfolio, the one medium Tarantino has gone on record as to have no interest in is videogames. “I’ve been given video game players and they just sit there…gathering dust until I unplug them” he tells The Telegraph in 2010; and so far it seems he won’t have to change his position.

But that’s okay. Turns out videogames are not lacking their own Tarantinos. Just as how filmmakers who make irreverently violent films set to ironic soundtracks will be labeled Tarantino imitators at best, videogame criticism isn’t immune to this reductive labeling either. Cheeky, violent videogames will likely be declared “If Tarantino made a videogame” by the 10 nearest critics.

Tarantino has a grip over the collective imagination

When used, that expression is often misattributed. Videogames still need to work harder to earn that sort of comparison. Tarantino is primarily influenced by other films (one look at this TV Tropes page will attest to that). Videogames occupy such a unique place on the audio-visual-interactive spectrum that it can be—and increasingly is—influenced by nearly anything: film, music, physical activities, motion gestures, it goes on. The reason filmmakers get labeled as Tarantino imposters is because there are those who are content to simply copy the most striking and inimitable hallmarks of his films (i.e. the violence). But violent games with a sense of wit doesn’t make a game necessarily Tarantino-esque, contrary to popular belief.

Take a look at Tales from the Borderlands (2014) and No More Heroes (2007). On the surface, they have all the qualities necessary for that highly sought-after Tarantino comparison: the music, dialogue, pop-culture sensibilities, and explosive moments of violence involving bad people. But like some of Tarantino’s most important contributions to film, their importance in upending videogame norms have been largely glossed over. Quentin Tarantino, for whatever lack of subtlety, can still create films that are diverse in characters, genres, and subject matter. The violence and wit simply connects these disparate elements together.

Tales from the Borderlands might be the most ideal to compare to a Tarantino film in terms of tone and stylistic choices. But even if it wasn’t, there is a similarity between the two that runs deeper than its spot-on musical cues, explosive moments of violence, and actual references to Pulp Fiction (1994). Due to the limited freedom allowed in Telltale’s chosen genre, the point-and-click narrative adventure, they were tasked with making a franchise primarily focused on shooting into a compelling character drama/comedy. In other words, dialogue would have to substitute for gunfights in most instances of the five-episode series. It helps keep the momentum when Tales from the Borderlands demands split-second decision making and player actions. In Tales from the Borderlands, more than any Telltale game previously, your ability to talk your way out of trouble will ultimately determine your fate on Pandora. Because if you can’t bullshit your way through the bloodthirsty raiders, or the two-timing thieves on such a lawless planet, you probably have no business there in the first place.

Tarantino has always made films about bad people, and through those bad people we see the best and worst of ourselves. The AV Club’s review of The Hateful Eight goes deeper and details how each of its characters represent a certain, archetypal human value. In Tales From the Borderlands we, too, are tasked with playing two very different types of villains: the outlaw in a lawless land; and a corporate stooge of a large, evil, megacorporation. And through them we gain insight on the nature of survival, ambition, trust, and self-discovery. Telltale and Tarantino agree that outlaws and criminals, are, at the very least, the most entertaining mirror in which we can view the human condition.

their importance in upending videogame norms have been largely glossed over

So if Tales From the Borderlands managed to capture similar narrative themes as Tarantino’s best crime works, No More Heroes catapulted rockstar auteur Suda 51 into immediate Tarantino comparisons. Here was a colorful character of a man who waved around toilet paper and fronted, not a videogame studio, but a videogame punk band. He had made it big by making a game filled to the brim with pop-culture references, blood, sex, and a big old masturbation joke at its center. Really, it would have been harder to not call this man gaming’s answer to Tarantino.

Violent and humorous, No More Heroes expertly turned the Wii’s motion control into a smooth, third-person action game. However, beyond No More Heroes’ immediate style and beats, the elements that made the videogame truly subversive were glossed over. Many forget that of the many unique characters introduced in No More Heroes, the game’s inclusion of Shinobu Jacobs, the 8th best assassin in the the game’s world, stands out. Yes, she’s a katana wielding ninja; but she’s also a black, amputee, teenage girl, and later a playable character in the sequel. Possibly influenced by many of the pulp stories of the Blaxploitation genre, Shinobu Jacobs is the daughter of a kung-fu teacher who sells VHS training videos. He is later murdered prior to the start of the first game by a mysterious organization. When you meet her for the first time, she is essentially the hero of her own revenge story. While there are obvious comparisons to how Tarantino followed up Pulp Fiction with his own blaxploitation homage, Jackie Brown, it never occurred to me at the time just how a rarity a character like Shinobu Jacobs is. Not only is she a character that avoids any specific racial stereotypes, she actively embodies a uniquely original characterization while recalling influences from a variety of cultures and genres—70’s Kung-fu films, Japanese punk fashion, Star Wars, and ninja anime.

Suda 51’s punk opus didn’t only subvert the types of characters we could see in games, either. He also subverted the way we could identify with a playable character. Tarantino did this by using revenge as a tool to have his audience sympathize with his villainous protagonists. We will probably never understand the sort of world his characters live in, whether they are criminals in Los Angeles, Jews in Nazi occupied France, or a freed slave in Southern United States. But they are out for vengeance, and we at least no what it feels to be wronged. In that way, we can understand No More Heroes protagonist Travis Touchdown, but he’s not a career criminal. He’s an otaku, a person who watches wrestling, anime, and porn. And we are forced to identify with him in ways we might not like. Namely, the game’s central masturbation joke worked into the actual gameplay. In order to be an effective fighter in No More Heroes it is important you recharge your batteries, and we are forced to do it the way Travis Touchdown would. Yep, by shaking our Wiimotes up and down.

I don’t think Quentin Tarantino ever needs to make a videogame. I’ve played enough videogames to know that many of his fans are out here making games, maybe trying to become the Quentin Tarantino of videogames, chasing all the freedom and power that kind of influence would wield. But to do this is more than making stylish games. It’s about creating media that shakes up what the audience is willing to see versus what they’re willing to experience. Tarantino, through the force of his own personality, or creative engine, can make epic films that tackle slavery, or post-civil war reconstruction starring bullets and outlaws. Videogames do this too when they move past the glossy images of the most obvious Tarantino homage, it needs only to be recognized.

February 16, 2016

Fitz Packerton turns packing your bags into a theatrical videogame

The first note of suspicion arises in two boxes sat next to each other on a desk. The label on these boxes is blurred beyond detail by the low-resolution—it’s possible to make out that it depicts a cylindrical instrument, white and red in color. I told myself it must be batteries for the nearby handheld radios. But I think I knew it was shotgun shells.

///

“You hold your gun up when in waist-high water. You push away tall grass. Button just for Adrian Brody voicing how much ammo you have left.” These are a few of the features of the 2005 videogame adaptation of Peter Jackson’s King Kong that appeal to LA-based game maker Brendon Chung. “What a goldmine of things brendon likes in FPSs,” he exclaimed about the game. Follow Chung online for long enough and you’ll piece together an understanding of this list of Chung’s likes. Body presence, finicky objects, mundane tasks presented in excruciating detail, inventories that correlate to a character’s available pockets, it goes on.

a chopped-up series of reveals

In short, Chung loves it when a virtual world sells its own physicality entirely, not through hi-def graphics or similar benchmarks, but through physics. Especially, that is, if they acknowledge the ultimate imperfection of simulated physics—a kind of slippy, uncontrollable friction. This is what Chung loves to see in videogames, both the ones he makes and the ones he plays. It’s why his latest (co-designed by Hyper Light Drifter creator Teddy Dief) is all about picking up objects and putting them into bags or the trunk of a van. An entire story is told through this seemingly humdrum action.

It’s called Fitz Packerton. A name that shares a sarcastic artificiality with Ivana Humpalot from the 1999 Austin Powers sequel. Humpalot was a parody of James Bond’s love interests (like Chew Mee or Honey Ryder), acknowledging that these women were so one-note that their names act as a label, describing their entire existence exclusively in its service to Bond’s dick. And that is often all author Ian Fleming’s plots afforded these women. Fitz Packerton shifts that same parody to videogame protagonists, whose purpose is only to shoot guns, drive vehicles, or, in this case, pack bags. This character is called Fitz Packerton and with them you will pack objects so that they fit into bags.

But don’t get the wrong idea. Fitz Packerton isn’t concerned with you ensuring that each object fits neatly into its designated vehicle. It’s not that precise or meticulous. What it does want is for you to pay attention to its individual objects, on their own and in relation to each other, as it is through them that its story is told. It isn’t so unusual for a videogames to let the objects it has you handle tell a story. What is a little more unheard of is for the story to be told exclusively through these objects. And it’s this bold ambition behind Fitz Packerton that likely informs its unmissable theatricality.

The game unfolds in four distinct stages, with the completion of each stage opening up one of the walls enclosing the space to allow access to the next stage. In this way, the spatial design of Fitz Packerton resembles a theatrical stage when divided by curtains. You could probably say that about a lot of videogames, but in Fitz Packerton the comparison is distinct in that it doesn’t try to transition between these spaces naturally, nor does it try to sell the surroundings as anything but dull, grey virtual walls. This is clearly an artificial space and you have no choice but to recognize that. What this achieves is channeling all your attention onto the objects in each space. By doing so, it’s implied that these aren’t objects without a purpose, rather, they are props, and as the word implies, they are meant to support the narrative with the authored meaning they have been given. It’s a chopped-up series of reveals, with each new set of objects changing your understanding of the character, their destination, their intention.

you can see its artificiality playing out

The biggest tell of Chung and Dief’s approach to presenting Fitz Packerton‘s story comes at the very end of the game. Once it’s complete—or, at least, the narrative is over—you are left unprompted as its last action plays endlessly on repeat. Given a static camera angle and unable to move at all, you are left no choice but to press the Escape button, hoping that it’ll let you exit the scene. Here’s the thing: When you do hit that Escape button, the camera snaps you back to the first-person perspective you had before, letting you see that final action play out in its raw nakedness. Removed from the static angle that you’re supposed to experience this action from, you can see its artificiality playing out; how, through animation and sound, an illusion of a real-world event is created so that you can derive meaning from what amounts to a bunch of code enacted on virtual objects.

This moment could rightly be called a Brechtian act of breaking the fourth wall but, by now, it almost deserves to be Chungian. At the end of Chung’s 2012 first-person game Thirty Flights of Loving, you are thrust from the final scene into an art gallery, where you view the credits hung up on walls. It’s almost like a lobby after a stage show, where the audience gathers to discuss the play and sip on chardonnay. With this, Chung seems to encourage the notion that you’ve just seen a piece of entertainment meant to be considered from a distance. It goes against the usual efforts of a videogame, which is to try to sell itself as another reality that you can can immerse yourself in. Further, Chung provides an optional developer’s commentary in Thirty Flights of Loving, in which you play through the game as normal but have him explain every decision he made along the way. Every object placement, every virtual environment, every camera edit he made is revealed for its artifice. It’s akin to a magician revealing their tricks as Chung breaks the entire game down, almost going against his own work. But in doing this he shares his interest in the pained attempts at simulation and imitation that videogames often attempt. He celebrates videogames as unique magical theaters of illusory artwork and coded physics made for us to absorb and interpret.

Where most political games go wrong

How are presidents selected?

— How much time do you have?

A stylized sketch of how presidents are selected might go something like this: Candidates choose to run for one of two parties, raise money, compete in a series of caucuses and primaries to win delegates, and the candidate with the most delegates at each party’s convention becomes said party’s nominee. The nominee who picks up the most Electoral College votes in the general election then becomes president. That sketch leaves out the vagaries of political financing, third party candidacies, the curious sequencing of primaries, and superdelegates, but it normally gets the job done.

As with any system that straddles the line between the explainable and the outright byzantine, it doesn’t take much for the whole thing to descend into pure farce. Maybe it’s a candidate too rich to be disciplined by party or private interests. Or the untimely passing of a Supreme Court justice. These aren’t the most crazily unforeseeable of events, but they’re more than enough to disturb the quasi-natural equilibrium. (You can call it a constitutional crisis, if you so choose.)

This predicament ought be familiar to game aficionados. Games also depend on the line between the explainable and byzantine not being crossed. They are engineered to ensure that calamity does not regularly ensue but, at a certain point, depend on all participants to act within reasonable parameters. One might therefore expect games to be good at capturing the dynamics of the current campaign. At least when it comes to weirdness, that expectation is largely borne out.

Exhibit A: Stardock Entertainment’s The Political Machine 2016. The game treats the current campaign like a game, because that’s what is. Probably. Anyhow, you can play as the roster of current candidates or create your own. The game’s aesthetics dictate that all candidates look like they were hand formed from soft putty, but that does not mean the game’s in the tank for Ted Cruz. You can do all sorts of campaign-y things, like “mudslinging” or spending truckloads of money. There’s also an element of strategy because the campaign in The Political Machine 2016 isn’t about ideas—ideas, what are those? Traditional game elements like life bars are easily transformed into polling interfaces. If anything the transformation of game elements into election elements happens a bit too easily. At the end of the game, a candidate wins. It’s a game; there must be a winner.

a sort of cynicism about politics that serves mainly to prove its own cleverness

The Political Machine 2016 does not make enough of a statement to be truly satirical but it can hardly be mistaken for a documentary piece. Rather, it is a reasonably accurate sketch of political life that thinks the whole enterprise is silly. The Political Machine 2016 traffics in a sort of cynicism about politics that serves mainly to prove its own cleverness. It is witty in the same way political foes enjoyed Antonin Scalia’s dissents: a series of clever turns of phrase praised without reference to the underlying point. Fine. It’s still interesting to see a campaign so easily transformed into a game, The Political Machine 2016 feels like something of a missed opportunity.

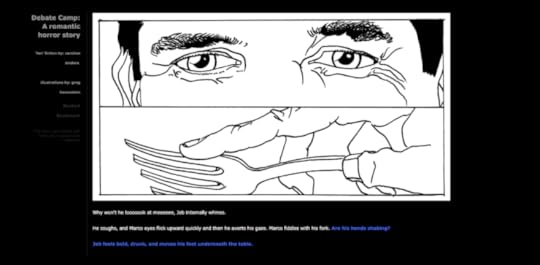

Exhibit B: Debate Camp: A Romantic Horror Story does not hold back. The choose your own adventure game asks one simple question about the Republican presidential aspirants: What if they’re secret lovers? To be clear Debate Camp’s developers, Caroline Sinders and Greg Borenstein, are not implying that the likes of Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Donald Trump are secret lovers. Theirs is a work of interactive fan fiction. Like X Factor contestants, the Republican hopefuls have been taken to a cave to prepare for the big stage. A few differences from the X Factor do present themselves. First: Dick Cheney occupies the eminence grise role in Simon Cowell’s stead. Second: The candidates are doing debate prep instead of ballad rehearsals. Debate Camp’s central conceit, however, is that all camps are broadly alike. They are all spaces where you ostensibly work on a skill but really serve as emotional pressure cookers. Debate Camp’s titular camp is not all that dissimilar from band camp or the space camp I once attended.

Debate Camp functions on a number of levels. It can first of all be read as a commentary on policies many of these characters have championed that force many Americans to live repressed lives without a full compliment of freedoms. The game turns that dynamic on its head: suddenly Marco Rubio is the one who suffers. Yet Debate Camp can more accurately be read as a story of yearning. It isn’t so much about sex or sexuality as it is about the deep neediness that might compel a person to run for president. Desirable though the job may be, the career path and work that goes into reaching the oval office hardly looks like fun. So why do it? Debate Camp is onto something when it suggests that campaigning is a way of filling some sort of personal void. If you don’t believe that, here’s a gif of Jeb! Bush putting on a hoodie:

In light of this weekend’s news, however, it’s hard to escape the sensation that Debate Camp and The Political Campaign 2016 might both still be trumped (sorry) by Christopher Buckley’s 2008 novel “Supreme Courtship.” It is, in short, the story of a president who, having run out of fucks to give, decides to nominate a Judge Judy-style TV presenter to fill a Supreme Court vacancy. As you might imagine, things snowball, causing much of the American political apparatus to descend into (even more of) a reality show of its own.

Political games could benefit from this approach

“Supreme Courtship” came out just around the time John McCain selected Sarah Palin as his running mate. It was the kind of timing an author can only dream of: a book about kitschy populism going on sale exactly as that strange brand of mavericky [sic] politicking takes off. The curious thing about “Supreme Courtship,” however, is that it remained applicable to the campaigns that followed. The book eerily foreshadows the Trump phenomenon. Buckley offers a very specific critique of American politics that takes on a life of its own. The Political Campaign 2016, on the other hand, offers a very broad critique of the state of electoral politics. Of course its critique will apply to future elections; there is nothing tethering it to this very moment. Debate Camp comes closer to the effect of “Supreme Courtship.” It has a very straightforward and focused point to be made about the world we live in, and that point will likely endure because our world is strange and not because the point itself is overly broad. Political games could benefit from this approach to political commentary.

Speak Up, The Order: 1886

This article is part of a series called Shut Up, Videogames, in which critic Ed Smith invites games old and new to pipe down, or otherwise. In this edition, he looks at the genre defying third-person action-adventure, The Order: 1886.

It’s no masterpiece—it’s the story of immortal knights fighting werewolves and vampires in Steampunk London. But The Order: 1886 (2015) is still more than videogame critics deserve. Its low review scores and petulant detractors are proof, once again, that games could never become art (whatever that would mean) because the people playing them and the people responsible for curating them simply wouldn’t allow it. Verily, no-one who reviewed The Order during its launch last year had a bloody clue. From complaining about its length, its closed, straightforward levels and its unwillingness to let the player explore, critics recited the same handful of complaints they throw at every game they can’t be bothered to consider. Even the praise levelled at The Order— “great atmosphere,” “solid gunplay,” “creative weapon design”—was recycled air. It’s a sorry state when a game as uninterested in tradition and form as The Order can only be viewed through the antique framework of magazine videogame review. And when critics have grown so smug and apathetic that only brazen, moist-eyed complaisance like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015) can get them to think—even for a second—about what they’re saying.

The Order cannot only be viewed through the antique framework of magazine videogame review

There are so many fantastic moments in The Order: 1886. The one-on-one knife fight with the alpha werewolf. Standing over the airship ballroom, identifying assassins disguised as guards via the discrepancies on their counterfeit uniforms. Igraine is a fantastic character. The ending, considerably more muted and sober compared to what could have been, is a rare example in the gaming industry of restraint and sombreness over spectacle—not that the game struggles with spectacle. Ready At Dawn Studios, quite rightly, picked up an award from the Visual Effects Society, and I can see why. Where so many games conflate visual lustre with colors, wide open spaces and fantastical expression, Ready at Dawn is fascinated by cold, old interiors. I’ve spent a lot of my life inside English churches, and the great halls at country estates, and the same woody smell and fragile silence that hangs heavy in those places permeates The Order, especially during scenes around the Knight’s roundtable.

At times, The Order lapses into rote third-person shooter or horror game style but largely I’m impressed and relieved with how defiant it remains throughout, refusing to emulate the many other games based around guns and monsters. I’ve never played anything like The Order: 1886. And I don’t mean in the dumb, false Saints Row way—this isn’t a sandbox game where every wacky, supposedly idiosyncratic idea has been researched and focus tested, and is remarkable only to the kind of people who think the Joker from The Dark Knight (2008) is a complicated character. I’ve bemoaned in this article the use of clichés, so forgive me in advance, but The Order is a true original. Videogames are often created to slot neatly into genres—shooter, horror, “interactive story.” But like its antagonistic Hybrids, The Order refutes easy classification. That wilful lack of straight identity meant, essentially, it was too complicated for game critics, not the individuals, mind you—they’re smart people—but the field in which they work.

Individuality and videogames are a square peg and a round hole. We credit work to studios. We judge all games by the same or similar criteria. We refer to artists with the dehumanizing titles “developer” and “designer,” or even worse, “dev.” The lack of diversity in the videogame industry is visible from space, but beyond precluding women, gay people, and people of color, there’s a surreptitious effort, smuggled through customs under the rubrics of consumer friendly or matter-of-fact writing to homogenize and compartmentalize videogames. Everything must have a term and a place. Everything must fit at least some of our pre-existing notions about what games are or should be. So when a game joyfully undermines the conventions of so many genres, a game like The Order, which cannot be easily separated out or discussed like one would discuss a household appliance, it goes misunderstood and forgotten.

Exactly what’s caused this opposition—an opposition expressed through unremarkable often non-confrontational language but an opposition nonetheless—to heterogeneity I could only speculate. It probably has something to do with games still being created by white men, to be reviewed by white men and then either bought or despised by white men. I’d say the gaming industry’s homogeneousness begins at race and gender but extends beyond those things, leading to a culture so blinkered and small that any contrary ideas, even if they come from white, straight, Western guys, must be chased away. We’ve delineated the independent space as suitable for exploration and experimentation, but big budget games are simply not allowed to effectuate and change. That would challenge our stratifications. It would fuck with our minds. Hence the magic of The Order: 1886. Hence the tragedy of its reviews. Something is going on. And until it’s identified and challenged, great, inventive, big budget games will continue to go unsung.

“Tracing You” uses web data to get closer than you’d like

The digital footprint is supposed to be an ominous concept. It’s supposed to be a reminder of all the digital breadcrumbs digital Hansels and Gretels leave in their wakes. But in practice, the digital footprint is too squishy a concept to truly resonate. How do you quantify all the little pieces of yourself given away with every click and pageview? They obviously add up, but in the moment they don’t feel like much. These pieces do feel meaningful to the companies on the other end of each transaction, however, and that asymmetry puts the individual web user at a disadvantage.

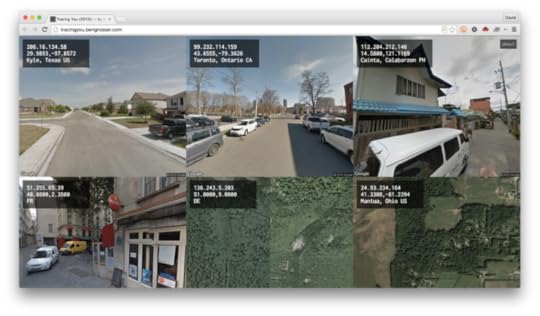

Artist Benjamin Grosser’s “Tracing You” is a brief reminder of the information contained in each click and every pageview. The website, which reproduces an interface that Grosser premiered at Paris’ Galerie Charlot, attempts to match visitors IP addresses with the nearest possible image. This is done by looking up the latitude and longitude associated with each IP address and then cross-referencing it with the nearest street view image.

The “Tracing You” homepage displays images and coordinates for the six most recent visitors. Results vary. In some cases, the image is an overhead view of a large tract. The result feels distant, at a remove from the viewer. (This is not strictly true: Insofar as there are few nearby properties, this may make it easier to pinpoint the visitor, but it doesn’t feel that way.) In other cases, however, the result feels close to home. Google’s camera is positioned in front of a home or a shop. Cars are parked out front. People can be seen walking about. It feels invasive, and it sort of is; that is the very point.

It feels close to home because that’s what it is.

“Tracing You” displayed an image a few blocks from my home—a four minute walk when caffeinated. You can’t see it in the image, but the camera car must have been driving past the church. The shot looks down a side street—there are cars on both sides; must have been a wedding that day—towards the car dealership in the building that’s much too large for its current occupant. You can’t see my front door in the image, but it gives you a closer sense of where I live than any of the information on my public-facing profiles. It feels close to home because that’s what it is.

Discussions of online abuse often run into the wall that is the “Internet is not real life”-claim. Words online don’t mean anything, apparently. Nor do threats. “Tracing You” is mainly about tracking and surveillance of a corporate or governmental varieties, but it’s also a useful insight into the ways anyone can glean this sort of information. Online and offline easily blur. A click becomes some coordinates, which quickly become an image of a front door. Where does one go from there?

Firewatch and the great American landscape

Steven Poole put it beautifully in his book Trigger Happy (2000): “the jewel in the crown of what videogames can offer is the aesthetic emotion of wonder… such videogames at their best build awe-inspiring spaces from immaterial light. They are cathedrals of fire.”

Cathedrals of fire. Sit on that for a moment.

I’m at my computer and the screen is burning, roaring with the light of the sun. Steven Poole’s got a point.

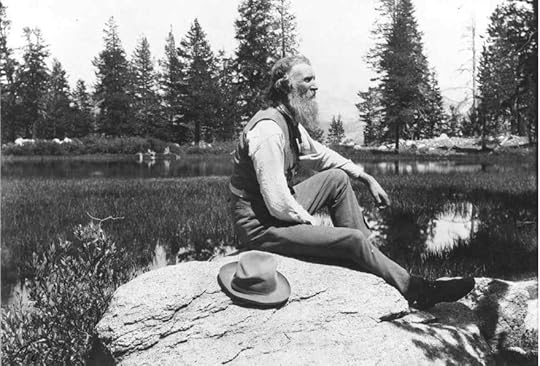

Wonder is hardwired into the history of videogames. It’s there in the labyrinthine mazes of 1997’s Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. And it’s there in the sheened cityscapes of 2007’s Mass Effect. Firewatch is part of this tradition, but it also fits into a longer-standing history of wonder and the natural world, a history borne in the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s also part of a more specific American heritage incorporating both literature and paintings, from the vast landscapes of painter Frederic Edwin Church to the words of John Muir, the founding father of the American national parks. And even though Church and Muir were documenting different landscapes—Church concerned with New England and Muir with the Sierra Nevada mountains—they share a visual lexicon.

Firewatch stands in solidarity with these representations. There are the great red mountains, coated in the rising or falling sun, and the conifers that stretch upwards with their blackened silhouettes. And that sky. Wow, that sky; it’s deep blue almost eclipsed by the constellations given free roam away from the light pollution of the city. Firewatch owes its existence, in part, to the work of John Muir and his role in the creation of the first national parks. If Muir loved those lands into the American consciousness, then Firewatch does a damn good job at trying to keeping them there.

A TERRESTRIAL ETERNITY

It’s fitting, then, that Firewatch inherits some of the fanatical zeal that characterized much of John Muir’s literary work, particularly My First Summer In The Sierra (1911). It’s a difficult read now. The style is florid, almost too much, but it conveys such exuberance, a supreme affection for the place, that it eventually wins you over. Muir speaks of how “the west is flaming in gold and purple, ready for the ceremony of the sunset… A terrestrial eternity.” Firewatch has these ceremonial moments, too. They’re there when Henry, fire lookout and protagonist, climbs out of a cave and sees the night sky for the first time, alive with stars. And they’re there when he comes across an abandoned cabin; the door falls through to reveal a vista, pines in the foreground while mountaintops stretch into the distance.

These are tightly designed moments that are hyperreal in their perfection, but they’re also distractingly artificial. Like the landscape painters of the 19th century they capture imagined moments, moments so perfect and full of drama that they couldn’t possibly have occurred in real life. Thomas Moran, in his painting ‘Nearing Camp, Evening on the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming, 1882’, went so far as to entirely eliminate the settlement that compromised his pre-industrial fantasy. And in Albert Bierstadt’s ‘Sunset in the Yosemite Valley’ and Frederic Edwin Church’s ‘Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860’, light dominates the pictures with such an elemental drama that it could only have occurred in the minds of the artists.

But for these artists, and Muir, the majesty of nature was bound up in religious devotion. These images of America present the totality of God, imbued in the world and every living thing. Muir observed that, “God himself is preaching his sublimest water and stone sermons.” He was acutely aware of the deep history of the place, of the way in which hefts of rock were carved by glaciers millions of years ago, how these created not only the sheer cliff faces but also the lush meadows found in the Yosemite region. And in these lush meadows he could fully indulge his botanical tendencies to discover the detail, the variety in natural life.

And this detail, that flourishing of life, is there in Firewatch’s imagining of the Wyoming wilderness. One of the first things Henry does in the game is inspect his new home, the firewatch lookout. There’s his typewriter, a nod to Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Angels (1965), and there’s the assortment of pots and pans, a thermos, outdoor paraphernalia needed to enjoy a long summer stationed in the middle of nowhere. And there on the wall is a poster detailing the common flora of the Shoshone. There are the trees: Blue spruce, Cottonwood, Lodgepole Pine, Aspen. And the shrubs: Birch Shrub, Alder Shrub, Mock Orange, Sagebrush. And there are the flowers: Prairie Fire, Filaree, Golden Aster, and the Tailcup Lupine. Firewatch inherits Muir’s eye for detail, and in doing so tells us to pay attention to our surroundings. It’s detail specific to the Shoshone National Park, and it helps breed a deeper understanding of the place. Muir, I suspect, would be pleased.

DISCOVER THE DETAIL, THE VARIETY OF NATURAL LIFE

There are, though, important ways in which Firewatch contradicts the ethos of Muir, particularly in its attitude to exploration. Muir was never bound by predetermined routes or existing pathways. He travelled where he wanted, usually in search of some unrecorded species of plant, somewhere he felt was untouched by human interference. Muir was not even bound by mountain faces. On one particularly wild occasion he quite literally surfed an avalanche to the bottom, escaping with only minor bruises and cuts. But in Firewatch, Henry is bound by the paths Campo Santo have laid out. He maneuvers up and down the rock faces the developers say he can. Even in the meadows, usually surrounded by gentle rock slopes, he’s unable to step onto the smallest of rocks, to move off the beaten track. I know Henry’s meant to be clumsy, a bit heavy on his feet, but it felt counter-intuitive, antithetical to the naturalism—stylized, sure—the game offered. It left me feeling frustrated, duped at times, by a videogame that seemed to promise the great outdoors but wound up giving me an elaborate facade.

But Firewatch is a more personal account than Muir or the landscape painters could ever muster. Muir was looking for something in the Sierra Nevada mountains that lay away from the “clocks, almanacs, orders and duties,” of the lowlands; he was looking for freedom and meaning in “Nature’s cathedrals, hewn from living rock.” And painters such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Moran saw God too, but they also saw man’s personality—his potential for exploration, resilience, and conquering. Firewatch steps away from these religious and colonial considerations, these big outward looking ideas, to focus on the intimate stories we as humans bring to the wilderness.

Henry isn’t looking for anything in the Wyoming mountains other than escape. In a beautifully executed introduction we learn of his and Julia’s relationship and it’s sad, inevitable breakdown caused by her early-onset dementia. Likewise, Henry’s friendship with Delilah, his lookout colleague, unfurls gracefully through radio conversations as they try to unpick the histories of one another while simultaneously creating their own. And then there’s the tragedy that lies at the heart of Firewatch’s mystery, the events surrounding Ned Goodwin and his son, Brian. Each of these characters is struggling, unable to cope with their own social or familial pressures. They are driven to the nearest end of the world they have, the Shoshone National Park, to escape reality.

Maybe in this regard John Muir and those landscape painters are not so different from the characters of Firewatch. Perhaps in striking out into the wilderness alone, those 19th century forebearers were leaving behind the same sort of troubles Henry is running from. Muir certainly left behind a difficult relationship with his father, a relationship that included not only beatings but “heart thrashings”, episodes of intense shaming. Henry experiences shame, too, but for his own inadequacies following Julia’s diagnosis.

CATHEDRALS OF FIRE

And honestly, Henry could do worse than escaping to the exquisitely rendered mountains and forests of Firewatch. It’s a world that delivers wonder with such frequency and to such great effect that it borders on the fantastical. But it’s also strangely limited by the potential the visuals present. Those instances where exploration is curbed, where Henry is hemmed in, threaten to derail the choice the vistas, and also the conversations, work so hard to maintain. You’re reminded, in those moments, of the inherent artificiality of the medium. Steven Poole’s metaphor, “cathedrals of fire,” holds up. Cathedrals may point to the sky, to the realm of (im)possibility, but they’re ultimately limiting; they enclose rather than release us. Firewatch is much the same. It’s a beautiful, beguiling place to spend some time, absolutely worth it while you’re there, but sooner rather than later you’ll yearn to shed its shackles, to get off the beaten path.

Header image via Wikimedia.

Firewatch image via Flickr.

John Muir image via Sierra Club.

Forest image via Wikimedia.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers