Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 158

February 23, 2016

New edition of Monopoly will swap paper money for bank cards

Hasbro has heard your cries for help and taken action. The scourge of adding up payments in Monopoly has been eradicated. Cash is no more.

Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game, which will come out this fall, is set to introduce four bank cards that can be used to make payments and transfer properties. Other editions of Monopoly—of which there are many—will continue to use cash for now, because the future of banking is not for everyone; you have to buy it.

The card reader is an amusing enough doodad, but what problem does it really solve? Most accounts of this development are light on answers. Maybe this is just change for change’s sake. That would not be unheard of; money, as John Lanchester argues in I.O.U. can best be understood as a force always on the lookout for new opportunities to grow. Financial innovation is therefore something of an inevitability, even if it serves no greater purpose. In that respect, Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game might be an unusually accurate name.

Gizmodo’s “Toyland“ blog, however, offers two possible explanations for this development. First, automated banking might do away with dishonesty (“Is there anything worse in a game of Monopoly than thinking you’ve bankrupted another player only to discover they have a secret stash of cash hidden away?”). What is a capitalism sim without dishonesty, you might well ask, but fair enough. The other issue is that Monopoly is apparently too damn slow. Pesky math! So, those are the problems Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game is meant to solve, maybe.

Monopoly initially served as a reflection of the American economy. The game’s deployment of digital banking, however, moves the game further from how the nation’s payments are processed. America is not a cashless society, nor is its use of credit cards particularly advanced. In 2014, The Guardian’s Heather Long rightly asked “why is the US a decade behind Europe on issuing safer ‘chip and pin’ credit and debit cards?” Scant progress has been made on this front and, as with all economic progress, it is only being experienced at the higher end of the market.

If you want an economy that looks something like Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game’s, it’s necessary to look abroad. “Bills and coins now represent just 2 percent of Sweden’s economy, compared with 7.7 percent in the United States and 10 percent in the euro area,” the New York Times reported last December. “This year, only about 20 percent of all consumer payments in Sweden have been made in cash, compared with an average of 75 percent in the rest of the world, according to Euromonitor International.” For the first time, Monopoly may be more aligned with the future of banking than its past.

That Dragon, Cancer documentary turns to crowdfunding for wider release

While last month’s That Dragon, Cancer is, itself, an artifact worth discussing on a number of levels, especially in terms of its handle on faith and loss, there is more to the story than what the videogame contains. Some of that story can be found in the documentary Thank You For Playing, which is primarily the work of filmmakers David Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall. The pair followed Ryan and Amy Green over an 18-month period as they slowly pieced together a videogame about their dying infant son Joel, who was diagnosed with brain cancer, and fought it for a number of years before passing away. The resulting documentary combines the intimate scenes with the family with their animated appropriations in the digital realm, offering insight into how a videogame “can be used to document profound human experiences in the modern age.”

Achieving any of this doesn’t come cheap

Thank You For Playing has been touring the festival circuit over the past year and even graced our very own Two5Six conference in May 2015. But now it’s time for a wider release, and for the film’s creators to achieve two of their goals, which are as follows: 1) to bring the film to theater audiences across the US and Canada, and 2) to enable various communities across the world to host their own screenings of the documentary.

Achieving any of this doesn’t come cheap. Hence, right now, Thank You For Playing‘s wider release depends on the success of its current Kickstarter campaign. The set funding goal is $35,000, which, if reached, will allow the documentary to be booked into several theaters with the help of indie film distributor FilmBuff, as well as manage a digital release. But backing the documentary on Kickstarter doesn’t mean you’ll come away empty-handed, of course. If you’re in New York, you can secure yourself a ticket to the NYC screening for $20, or if New York is out of your reach, that $20 can be put towards getting a digital copy of the documentary.

There’s lots more on offer, too, as you’d expect, including a bundle of the film, That Dragon, Cancer itself, behind-the-scenes access, and the soundtrack at $90. There are also rewards geared towards those who want to screen the film to a club or organization (you’ll need a public performance license, of course), and these are discounted during the Kickstarter: “1 screening with a public performance license and a filmmaker Skype Q&A for $195 for non profits, and $295 for other organizations. Or an educational copy of the film—yours to keep and screen as often as you like, for $350.”

You can support Thank You For Playing’s wider release over on Kickstarter.

Artists pick out their favorite critters from upcoming game Necropolis

It is well-known that upcoming dungeon-delving game Necropolis looks ludicrously stylish. Its stark angles, moody lighting, and cartoonishly exaggerated characters give it an aura that lies somewhere between art deco and fairy tale; as if Red Riding Hood were the emcee for a big-band show. It’s a striking aesthetic, and it does an admirable job of setting Necropolis apart from the gothic horror of its major influence, From Software’s Dark Souls (2011).

However, part of what’s allowed Dark Souls to be so successful is its memorable cast of baddies, their gruesome appearances helping them to linger in the minds of its players. Necropolis, too, is looking to make an impression with its own cast of foes, albeit in a more lighthearted way better suited to its unique look. In preparation for the game’s March 17th release date, Necropolis’ art director, Chris Rogers, recently sat down with the game’s artists and animators to talk to them about the creatures they’ve designed and ask which are their favorites.

Most popular was the game’s Gemeater enemy, which looks like what might happen if someone tossed a street shark into a gladiatorial arena. “It was really fun to create concept variants for him because of his comical look,” says artist Fiona Turner. “His large head, vacant stare, and reckless attacks contribute to his appeal. I imagine he has a peanut sized brain and has only survived the Necropolis long enough to meet you due to his brawn.”

“So many things in the Necropolis are calculating, thoughtful and deadly,” elaborates animator Hollie Mengert. “But the Gemeater survives by pure brute strength. I love seeing him thunder his way around the Necropolis.”

Meanwhile, animator Brigittie Tijerina talks about the unexpected horrors of the Eel Trap. “Animating it was so fun and its movement reminds me of a dog shaking prey in its mouth,” she shares. “Also, because the lair in which the Eel hides blends with the environment very well, it startles me every time it pops out.”

I love how his animation really sells his bird-like and flighty movements

Animator Jakob Zoepfl opts for the Changeling as his favorite, “Mostly because it’s rarely seen and it was super fun to make. It moves very fluidly and its long gangly limbs make for some interesting shapes and poses.”

Whereas character artist Marian Huber favors a friendly coward rather than a deadly enemy. “My favorite critter from Necropolis would have to be the Chemist, our cowardly, bird-brained merchant,” she explains. “It’s always funny when you open up a chest and finding [sic] him cowering in there, hiding from the horrors of the maze…I love how his animation really sells his bird-like and flighty movements, as well as his salesman attitude.”

Finally, character team lead Doug Magruder isn’t able to pick a favorite, likening the question to Sophie’s Choice. “Narrowing it down to one ‘favorite’ is like picking a favorite child out of your multitude of available children,” he shares. “All characters in Necropolis are special to me, from the lowly Rat King and Scrounges whose skittering movement and simple designs are endearing and pleasant…to the Hollowman Brute whose fierce aspect of a monstrous mechanical gorilla is carried brilliantly through his movement and mesh in equal measure.” He did admit, however, that “…the character that fills me with the strongest emotions is the Blackguard. It has gone through the most hands, had the most work done to it, the most joy and pain and heartache and triumph are present in that simple player avatar.”

We’ve already been impressed by Necropolis’ distinctive world, and now it seems as if the characters populating that world will be just as creative, and of course, stylish.

Rogers’ talk with the art team is the most recent in a series of behind-the-scenes updates as the team gears up for the game’s launch next month. To see the full talk and keep up with new posts, check out the game’s development log.

The Witch isn’t an empowerment narrative and that’s why it’s great

Before, I was not a witch.

But now I am one.

— Margaret Atwood, author of Half-Hanged Mary and descendant of accused witch Mary Webster

The Witch, described simply by its first time writer/director Robert Eggers as a “New England fairytale,” tells a story we’ve heard many times and in many different ways—but with one crucial difference. The ancient, devil-loving hag who wreaks havoc on good, devout Christians is, of course, a tale as old as most countries. More recently, though, it’s also been reapproriated to incorporate everything from Arthur Miller’s metaphorical scapegoats to the WB’s Halliwell sisters (and whatever the hell Strega Nona and her magic pasta pot are). But in a brilliant clash of world views, Eggers’ The Witch combines the sincere terror of the original witch’s tale with the echo chamber of modern hindsight. The witch in this case, neither metaphorical nor sympathetic, embodies an almost blameless evil: a fact of living on earth that’s as material as rain or food poisoning. By taking the Puritan nightmare at face value, The Witch puts the onus of meaning-making on the contemporary audience and asks us to make a conclusion about what lore like this means about who we were as people back when we believed in it. Who we are now.

(Beware, for wicked spoilers this way come.)

Already, many label the coming-of-age journey of The Witch‘s female protagonist Thomasin as a feminist tale of empowerment. And indeed, Eggers’ story does appear to validate what your feminist history teacher has been saying all these years: fear of female power fueled the Salem witch trials. What killed all those women (and some men) was a patriarchal society that not only thought of women as the weaker gender but also saw their sexuality as literal dark magic. The Witch covers it all, setting Thomasin and her budding bosoms up for slaughter as the natural scapegoat for evil.

But something about the feminist interpretation of the film’s events feels amiss to me. So, when Eggers held a Q&A after a showing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music this past Saturday, I decided to ask him about it. Somehow, his answer only made the claims of empowerment even more intriguing.

How can Thomasin’s story be one of female empowerment

Before we got to mine in the final moment of the Q&A, however, a man to my left asked the question on everyone’s mind. Would the director and talented, fresh-faced actress Anya Taylor-Joy consider Thomasin’s final resting place in Satan’s blood-soaked embrace a “happy” ending? Taylor-Joy answered: yes, because it was the first choice she really got to make. Yes, because it meant empowerment. Yes, because society left her no other option: if she went back to the plantation, she’d face the same accusations; and she couldn’t very well run a farm on her own with nothing but her dead family’s corpses for fertilizer.

Already, red flags were firing. How can Thomasin’s story be one of female empowerment when, as the final scenes imply, she chooses Satan because she literally has no other choice? If the story had painted her ultimate destiny as a clear decision between the life she lived with her family and dancing naked in the woods around a flame, that would be one thing. But Thomasin is no Carrie (of the Stephen King novel), who, despite ending up worse off in many ways, at least chose to be up there of her own volition.

I found the answer to this discontinuity once Eggers answered my question about what it had been like to write a movie about the fear of female power as a man. I asked the question for no other reason than I was genuinely curious about the challenges and insights that experience might have come with. Men, of course, can and have and will continue to write fascinating stories about female empowerment in horror. But, unarguably, a difference between Brian de Palma’s film adaptation of Carrie (1976) and Kimberly Peirce’s Carrie (2013) exists, for example—and it’s to do with much more than Hollywood’s declining artistic integrity.

To his credit, however, Eggers answered a difficult question with potentially catastrophic backlash with a careful (if somewhat fumbling) kind of honesty. Like many who get asked a sticky question they don’t have a semblance of a script to during press events, he clammed up, at first mumbling some vague PR response about consulting many different types of people with many different perspectives (in, I hate to say it, a somewhat eerie echo of Mitt Romney’s “binders full of women.”) Then he gave the honest answer: an equally awkward declaration of his loving and important relationship to his mom. Finally, Eggers gave the interesting and truest answer: “I didn’t set out to make a feminist empowerment narrative. But I learned that writing a witch story is kind of one and the same.”

your best chance at salvation was to turn to pure evil

There it was. The Witch, rather than being a tale of empowerment, instead might better be understood as a straightforward case study of the puritan woman’s dilemma. Because if nothing else, The Witch reminds us that, to a group of women who truly believed that eternal hell and divinity were real, inevitable destinations, sometimes your best chance at salvation was to turn to pure evil. While all other arms—including those of the ones you loved—are pushing you into the flames, Satan’s open up and welcome you.

But, really, you didn’t even need to be accused of witchcraft in order to live an inherently lesser and more sinful life in the eyes of the Lord you were supposed to worship blindly. Because, in the Puritan version of Christianity, woman has no true place among God: her faith is inherently less powerful than a man’s. Even though Genesis I (the older version of the ultimate origin story) describes man and woman as being made at the same time and both in the image of God, Genesis II (the Puritan preferred chapter) twists it a little differently. In that version, man is created in the image of God, while Eve, created from Adam’s rib and thus made in his image, is basically a notch above animals in the Eden totem pole. Thus women, Puritan’s believed, were more susceptible to the devil because their souls and bodies were inherently weaker. Simply put, men have a direct line to God. Meanwhile, women’s calls get patched through to a man first, then finally to God if the man vouches for her—but also if she’s unlucky, she could accidentally get transferred to the Satan hotline.

Needless to say, being a woman in Puritan society was a shitty lot in life. No matter how hard you prayed or how much you dedicated yourself to God, you were always closer to the flames of hell than men. If nothing else, Eggers’s The Witch is beautiful because is sends that reality into sharp relief. Rather than tell the easier, more typical modern witch story about female empowerment, it tells the story of female anxiety and dread. It revels in the horrific trauma inherent to being a woman in 17th century America.

American Truck Simulator is here for the long haul

I didn’t get my driver’s license until I was 19 years old. This is rare in my home state of Wyoming, where most kids learn to drive manual before the first day of high school—I had to make every effort to avoid the attendant responsibilities of vehicular ownership. But the mountainous west is colossal, grandiose, and requires a car to accomplish literally everything, so of course I capitulated. Every vehicle I drove was “pre-owned” and equal parts charming and dilapidated. They had nicknames, lost mirrors in bank drive-thru lanes, played Local H and Suicide Machines tapes, stranded me on the highway, served romantic interests, and consumed all my disposable income.

Escaping to the east coast freshened my perspective: give me those walkable distances, bike paths, unreliable buses, and crumbling train infrastructure. You can keep your interstates and parking meters. I’m done with driving. It requires too much of me; to focus unerringly so that I don’t die or kill someone else. It’s also super boring. When driving, you know you’re missing out on some great Snapchats and text messages, and unable to really zone in on your jams or whatever’s on the radio because you don’t want to be subject to a bloodbath. Which is to say that driving is pure torture for me. This is why I know that, after this heart of mine finally bleats out and my religious misdemeanors send me down to the hot lake, I will be lashed behind the wheel of an automobile and damned to an eternal hell of road rage, interminable loan payments and insurance premiums, constant vehicular breakdowns, and worst of all, other drivers.

Playing American Truck Simulator dredged up all of this. So many dormant, driving-associated emotions erupted in me that I had to take a prolonged break after less than an hour. I knew the premise and was aware of the success of its forbear, Euro Truck Simulator (2012), but it was still a surprising slip into old habits: cursing my fellow human beings, cursing this bumbling man-made death cage, cursing my own inability to park with any sliver of effectiveness. But after some tea and deep-breathing exercises I got back in the cab.

The proven formula established by Euro Truck Simulator has been uprooted out west to Nevada and California; enormous deserts that are easily compressed in computational space-time with a dearth of trees to gum up the processors. Make a profile, pick a side in the endless Peterbilt vs. Kenworth debate, name your company and get haulin’. American Truck Simulator gets you on the road as soon as possible, but it does not neglect the “simulator” in its title, dropping morsels of small business management as the pennies trickle in. If you wish, you can be a grunt that dreams about owning and operating a trucking company, taking out loans, hiring drivers, buying more trucks. I, however, do not have the lifetime to spare for such a commitment. But I assume that the endgame is that you become the Gerhardt family from Fargo’s second season, having to defend your illicit shipping empire against new world Kansas City corporate mobsters.

A MONSOON OF ANXIETY

Until that bloody showdown, American Truck Simulator offers numbers and trucking and it emulates both majestically. Scrolling through the bank tab and considering loans and the associated interest and monthly payments sent me spiraling into despair. The sticker shock of new trucks in showrooms across the state left my undershirt soaked with sweat. And the driving itself brought back the monsoon of anxiety that was my twenties. All of which I mean as an honest appraisal. American Truck Simulator so successfully replicates the act of driving that it floods me with ancient emotions I thought long resolved, and I’m left wondering if it was designed by Star Fleet empath Deanna Troi herself.

With each accepted trucking job I have two goals: To escape whatever city or town I’m in as soon as possible with a minimum of left turns, and to cruise any uphill exit ramps without stalling out. Accomplishing these tasks is difficult, but failure is almost always attributable to driver error. The driving is fluid and nuanced, with most settings adjustable to some degree and almost every aspect of the vehicle at your disposal. I’m so anal that I mapped the turn signal keys to my controller’s face buttons, one of my only controllable outlets of relief. There’s a comfort and glee to be found in sticking to assumed speed limits. The landscape is enchantingly rendered and every city accurately oppressive, though I can’t take in much of either as my defensive driving lessons require me to constantly check my mirrors and proximity to traffic lines. Your entire desired trucking experience is thoroughly customizable but if that’s not enough the modders will have you covered soon.

My real-life log of in-truck hours is nil, but driving the rig in American Truck Simulator feels eerily accurate, down to the floatiness of managing your tonnage at high rates of miles-per-hour. It’s closer to Mario Kart than one might imagine: you are primarily planning ahead rather than reacting. If you have to slam on the brakes it’s already too late, you’re probably 10 gears behind in your downshift, so get ready to watch that damage meter eat away at your profits. It pays to drive safe and sensibly. After all, the race is only against yourself, well, also the traffic, fuel, and the game’s presentation of the limits of the human body. Parking is almost an entirely separate puzzle game. It’s a maddening nightmare conceived by frenzied eldritch fiends to torment the mind. Thankfully, it can be skipped or mitigated with only a dollop of shame.

There’s space for mayhem as well. American Truck Simulator contains multitudes of it and caters to all. The first time I crashed into another car I panicked: Who do I call? Would my mom flip out? Where is the insurance information kept in this game? I was so wound up that I almost missed the quick cop siren and instant fine. No messy human interaction, just a garnish of my bank account and a lane full of impatient motorists. Larger incidents require a little more hands-on attention, potentially involving roadside assistance if your rig is too trashed to make it to town. Even that chaos merely evokes a sense of futility while allowing the chance to move along swiftly enough; a lesson more implied than learned. Still, I was so shaken by the immediacy and impact of every incident that I was instantly transported to the close-calls of my vehicular youth.

ENDLESS WAVES OF ASPHALT

Driving is inefficient, extortionate, and most people are garbage at it, including myself. I couldn’t comprehend why anyone would endorse the lie of the open road. American Truck Simulator reflected the anxious reality, but also allowed me to appreciate the grandeur of it all. I can finally see what I presume most other Americans have always enjoyed: Endless waves of asphalt paved just for me, veining the contiguous southwest, begging to be casually traversed. But stay out of Vegas and LA, those places are traffic shit-scapes.

Header image via Wikimedia.

Screenshots via YouTube.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Totem Teller will invite you to repair mysterious, broken truths

“Discover a broken world. Restore characters. Close plot holes. Truth is in the Telling.”

The above quote is all the descriptive information you will find on Totem Teller’s website. The game is still in its early stages—with the creators at Grinning Pickle mostly using social media to share more information about it, through screenshots and gifs, as they toy with different aesthetics and mechanics. The game’s IndieDB page goes a little further at least, telling us that the player guides the Teller as she explores a world which is part of a fading memory of a disintegrating story. The Teller gathers “pieces,” mends character arcs, unveils twists in the plot, and closes “holes” so the story can be retold.

With its female protagonist, as well as the themes and mechanics of time and decision making in a gloomy, and yet, at times breathtaking environment, its difficult not to draw parallels with the recently released Oxenfree. This, coupled with what seems to be a subdued glitchiness of the player’s experience of time and space, makes the connection stronger still.

However, it’s the potential differences between Oxenfree and Totem Teller that make the latter exciting. So far, all released footage from the game shows the Teller as a profoundly lonely figure among the gorgeous landscape. This is a stark contrast to Oxenfree, where the a large point of the drama is negotiating the dynamics of the teenage group of characters.

Moving beyond this comparison, Totem Teller clearly has an appeal all of its own. Its mysterious adage of “Truth is in the Telling” hints at intrigue, multiplicity, complexity. It also seems to undercut the idea of Truth being a singular, infallible, and objective object, to somehow be gained or gleaned as a desirable end. If Telling can receive the same upper case as Truth, then this tells us it has just as much power and sway.

Telling does not detract from Truth but rather enhances our understanding of it

This reminds me of historical concepts such as Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities”, describing how we might socially construct our larger identities. Or perhaps, E. J. Hobsbawm and T. O. Ranger’s idea of “invented tradition,” once again to describe a type of social construction, which we often perceive as an infallible and objective truth. However, the most important point in all this is that, no matter how much we might want to wash ourselves clean of things “imagined” or “invented” as affronts to Truth, these aspects actually allow Truth to have so much more depth than we could initially give it. Telling, does not detract from Truth, but rather, enhances our understanding of it.

Be sure to keep up to date with Totem Teller’s development through its website

The videogames that want to be disobeyed

Early in Far Cry 4 (2014), you sit at a dinner table across from the brutal antagonist, Pagan Min. While remaining unnervingly calm, he tortures a man by stabbing his back with a fork. As they leave the room, Pagan Min turns to you and says, “Don’t move, I’ll be right back.”

The cutscene ends and you soon learn that you can move with ease. A quest prompt appears and tells you to “explore De Fleur’s mansion.” Will you listen to Pagan Min’s instructions to stay still, or disregard them and obey the game itself? If you ignore this prompt and sit at the table for 10 minutes, Pagan Min returns and a short, new ending unravels—you have essentially beat the game without playing at all. The other option moves the main story forward and gives you access to Far Cry 4 in its entirety. It’s a clever, almost comical way Ubisoft explores, maybe even parodies, the role of compliance in videogames.

these games still tell you what to do, but the difference is you don’t have to listen

Typically, videogames fall into a vicious cycle of giving the player orders: Fetch these items. Kill those enemies. Press a sequence of buttons. Conforming to these conventions becomes ingrained in the player’s mind as second-nature logic or as a formula for success. In notoriously difficult games like Contra (1987) or Super Meat Boy (2010), failure to comply with directions results in harsh punishment, from an untimely demise to repetition of previously completed tasks. What happens when the reverse occurs: What if a videogame asks you to throw away said logic and rebel against its instructions instead?

Loved (2010) and The Stanley Parable (2013), among others, challenge this rule of thumb by turning these conventions on their heads with contradictory instructions and unreliable narration. At face value, these games still tell you what to do, but the difference is you don’t have to listen.

///

A Monster at the End of this Book (1971) is a children’s book that coaxes the reader with reverse psychology. Narrated by the iconic Sesame Street character Grover, he begs the reader to stop turning the pages, all in fear of a monster lurking at the end. With each page turn, Grover’s panic grows. Illustrations depict him building brick walls that the reader crushes without trouble. He ties down pages that, once again, are easily “cut” by the reader. He jeers, “I’d just like to see you try to turn this page.” These taunts give the reader a sense of power through what they may perceive as rebellion, but the book expects this response to move the narrative forward. Once invested, the chances are slim that you would put the book down. The result has the reader experiencing a sensation of defiance.

Videogames can shape this concept further with deeper interactivity and sophisticated mind tricks. While reverse psychology is widely used as a child rearing method, it seems to have transcended into the digital culture of videogames. The Stanley Parable simulates player defiance with the use of an interactive, present narrator that adapts and reacts to the player’s decisions.

The Stanley Parable’s deserted bureaucratic setting is both lighthearted and insidious, which also adequately describes the witty, British narrator that follows and anticipates your every move. You, Stanley, are a character in this story and there is only one way it will unfold, according to The Narrator. When you face a set of open doors, The Narrator confidently booms, “Stanley entered the door on his left.” With this remark, the game is encouraging the player to consider defiance—the right door is wide open too, after all. Both doors are identical, but by ordering you to the left door before you’ve even stepped forward, player agency kicks in. You realize you don’t have to obey. It’s an approach that feels unfamiliar in videogames, where we are normally conditioned to comply with directions. However, certain social psychologists would go as far as arguing we’re wired to obey, even in instances where we don’t want to.

certain social psychologists would argue we’re wired to obey, even if we don’t want to

With the Milgram Experiment in 1963, volunteers were directed by a perceived authoritative figure to give electric shocks of increasingly higher voltage to what they believed was another subject. The majority of participants went as far as implementing a fatal shock when ordered, even if it went against their moral views. It entertained the notion that obedience is strongly innate in human nature, and that those who refused to continue were following their own moral values more rigorously. When it comes to defiance in videogames, however, to obey or disobey may not always be our choice to begin with. Jamie Madigan, a psychologist who specializes in videogame studies, believes that this sensation of rebellion is an illusion for the player. It’s not just the narrator that toys with you in The Stanley Parable, but also the man behind the curtain: game creator Davey Wreden. “What’s interesting about The Stanley Parable is that poking at the system to try and master it is largely pointless,” says Madigan. “Or rather, that’s the point of the game: your choices often don’t matter or are arbitrary.”

This is a concept that is continuously toyed with and parodied throughout the game. The Narrator is always one step ahead of you, regardless of your choices. With each wrong turn, he satirically tries to guide you back to the original path. In one instance, he paints a yellow line on the ground for you to follow; a literal “plot line” to return you to the supposed main story. Yet disobeying him is deliberately amusing; you become curious to see what The Narrator has up his sleeve next and what new, comical jeers he will throw your way.

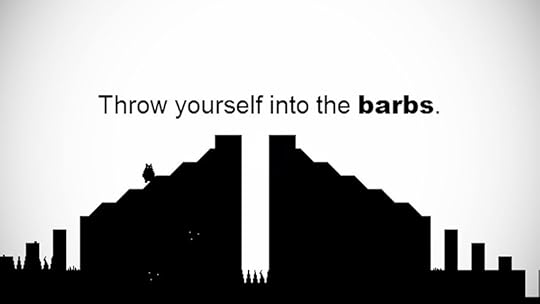

Loved has a similar ideology. This 2010 browser-based platformer by Alex Ocias is confrontational and kinky. The narrator begins by asking you questions about your gender and expectations. Whatever answer you give is spit out and rejected. If you say you are male, Loved refutes this by retorting that you are instead a girl. There’s a feeling of lack of control, as if you are at the narrator’s whim, just like in The Stanley Parable. The narrator views you as a puppet; something to be controlled. With this setup, there is an ongoing rapport between player and narrator, but your only method of communication is through obedience or disobedience. The narrator orders you to touch a statue to be forgiven and even demands you to commit acts of self-destruction, such as jumping into a pit of barbs. If you comply, the narrator praises you, but if you defy him, he degrades you and says, “Disgusting.”

“My philosophy was that involvement needs choices and for a person’s choices to matter, their choices must be acknowledged, and acknowledged violently,” says Ocias. Loved’s confrontational mechanics of obedience and disobedience resemble dominant/submissive BDSM power dynamics and sexual practices. It places you in the shoes of a submissive by putting you under the spell of the narrator’s dominance. Even if you disobey, there’s an impression that you are nonetheless being led by the narrator’s leash. Ocias says: “Sexuality is one lens I design for, and it would almost be weird to make a story dealing with relationships and power and not examine a BDSM perspective.”

“Maybe it’s supposed to be like a contract, obey and we’ll deliver fun?”

Ocias created Loved six years ago, and in his perspective, older games kept masochism integral to play. Loved takes these conventions and twists them into a more thought-provoking commentary, by being self-aware of its own masochistic undertones. You contemplate the connection between player and game. “Thinking about it now, instruction and obedience are really the assumed default in games, sort of divorced from play in ways like maybe saving and loading is, which is weird,” says Ocias. “Maybe it’s supposed to be like a contract, obey and we’ll deliver fun?”

///

GLaDOS, the passive-aggressive, robotic narrator from Portal (2007), enjoys deprecating humor much like The Narrator in The Stanley Parable, but she is also a serial liar. She promises a cake that’s never delivered, gives instructions that deem the ninth test chamber impossible to solve, and she even lies about lying. GLaDOS’ unreliability is quickly understood by the player. By beating the ninth test chamber, you are challenging those false instructions. Of course, that’s entirely expected of you. Undertale (2015) and Tale of Tales’ The Path (2009) have similar façades, but they take them to a further extreme. These games start the player off with tutorials or instructions that act as hindrances rather than guidance. You are deliberately told to do what the game perceives as wrong or a failure. It’s an unconventional approach that forces you to leave behind preconceived perceptions from other games. On this, Madigan says: “We’re used to having our literacy with games (that is, our way of thinking about them and understanding them) be useful from situation to situation. When it isn’t, that’s interesting and presents us with a rare challenge: learn to play the game in a way that we’re not used to.”

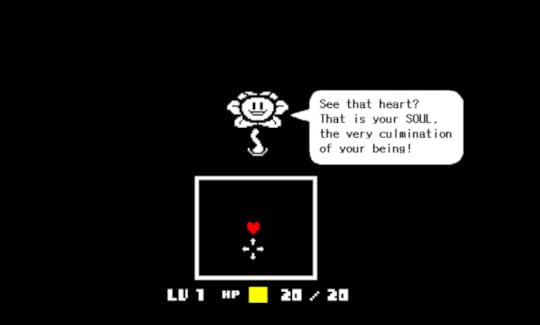

In Toby Fox’s Undertale, you’re swept away into a realm of monsters that often don’t want to fight you. It’s an unusual approach for a role-playing game, where combat is normally equated to killing. Flowey, one of the first characters you meet in Undertale, gives you false instructions when calling harmful bullets “friendliness pellets,” and using the term LOVE as an analogy for levelling up. It is later revealed that LOVE is actually an acronym for “level of violence.” Early on, it can be difficult to discern Undertale’s underlying message of peace. But when progressing through the game, it becomes clear through your interactions with monsters that killing is the last thing Undertale would encourage. Every monster can be spared through compassion and patience. “The message from Flowey’s tutorial is that things are out to get you, and that you should interpret what’s going on in the game in that light,” says Madigan. “This, of course, turns out to not necessarily be true and is the key to the whole pacifist playthrough approach.” This concept forces the player to think outside of the box: if killing is not the answer, what is? It’s a subtle way of prodding the player to disobey the initial guidelines. It asks you to set aside past ideologies of traditional game mechanics to achieve a “good” ending.

The Path, a horror adventure game from 2009, achieves this same notion of false instructions. As a re-imagining of the classic fairytale Little Red Riding Hood, you play as one of six young girls on their way to Grandmother’s house. As you begin the game or choose a new character, the message “Do not stray from the path” appears. The game stays true to the fairytale—you must leave the path and encounter the wolf to progress the full narrative. “As designers, of course we realized that the forbidden holds a certain attraction,” says Michaël Samyn, developer of The Path. “But it wasn’t a trick: we were simply following the fairytale.” Each time you conclude the game, a scoreboard appears that grades you in terms of item collection, exploration, and whether you encountered the wolf. A failure grade is given when directly entering the grandmother’s house as instructed. “The goal of the game is to reenact the fairytale,” says Samyn. “And in the fairytale, Little Red Riding Hood does not stay on the path.” Samyn explains that “success is very relative” in the game. Leaving the path means encountering the wolf and reenacting the fairytale, but it also leads to each young girl’s death. In The Path, disobedience and death are key to success. This uproots the conventional concept of compliance and survival in videogames.

there’s pleasure to be found in both obedience and disobedience

This approach to rule bending seen in The Path isn’t necessarily new, not even back in 2009. To turn to the extreme, sandbox games, for example, eradicate the idea of rules almost entirely, by empowering you with freedom, creation, and customization tools. However, what connects the games mentioned earlier is how, through toying with disobedience, they envision a Kantian view of anarchy. For German philosopher Kant, anarchy was defined as a mix of law and freedom, but without enforcement or punishment for the unlawful. These games attempt that same outlook—rules are presented, but compliance isn’t obligatory to succeed. These confinements are malleable, but only as far as the game’s world permits, which has you contemplate your true level of control.

There’s pleasure to be found in both obedience and disobedience. In both cases, you move the the game forward as its designer has planned. The difference is that the act of disobedience, even if it remains an illusion, can feel empowering or rebellious. From the workplace to societal laws, it seems strange that after following orders daily, we continue to do so as leisure within videogames. By being self-aware of their own mechanisms and encouraging the player to acknowledge them too, either through narration or specific instructions, these games invite you to set aside your comfortable routines. It is then that you can explore the meaning of play through a more anarchical lens.

Header image: obey mural detail via Susan Williams

February 22, 2016

Cheongsam to merge “virtual theatre” and videogames

Dubbed “virtual theatre” by its creators, Cheongsam is a game about chance encounters and the types of conversations that stretch until 3AM. It’s also about the role players have in creating a game’s story. Cast as a young man named Michael, you spend an evening getting to know an AI-controlled acquaintance named Maggie. There’s no set goal to your encounter with her, no achievements to earn or pre-written story branches to unlock. Rather, Maggie acts as a scene partner, and will respond to your body language and facial expressions in subtle ways, such as slightly and mysteriously glancing off into the distance. The way she plays off you, and you off her, are meant to be similar to the decisions actors make on stage. Like an improv scene, you build on each other’s choices, arriving at unexpected places so long as neither of you outright denies the other.

The neat thing about theater, and perhaps the quality that most sets it apart from film, is that it is performed live. Whereas movies are typically filmed away from an audience and, barring recuts, remain the same forever, theatrical performances vary wildly from night-to-night. On stage, actors are capable of responding to an audience in real-time, slightly changing the decisions they make to suit the feedback the audience is giving them. For instance, if a theater company is performing Twelfth Night and nobody is laughing, the actors can then change the way they deliver certain lines to elicit more laughter. If film is static, then theater is dynamic.

no two playthroughs of a videogame are entirely the same

Similarly, no two playthroughs of a videogame are entirely the same. Even if the story does not change, the way the player moves, the equipment they wear, and the tactics they employ will. Is your Mario hotheaded and someone who rushes through obstacles? Or is he more patient, carefully planning out each jump before making it? Games are performative, and Cheongsam understands this. Maggie isn’t just an animatronic who consistently repeats the same motions while guiding you through an on-rails theme park ride, but rather your own built-in audience who encourages you to engage with her and experiment. As she responds to your decisions, you can cater your performance around the feedback she gives you, just like an actor on stage. Meanwhile, she’ll be doing the same. Together, you’ll create your own unique production.

As the game’s website explains, “Cheongsam invites you to give your own interpretation to the script.” Just as Jonathan Pryce’s Hamlet is different from David Warner’s Hamlet, you and your neighbor might have completely different takes on Michael. Again, this isn’t necessarily new for games—in top Street Fighter tournaments, Lee Seon-Woo’s approach to playing Akuma is nowhere near the same as Hajime Taniguchi’s. But what’s refreshing about Cheongsam is how openly it acknowledges this. It encourages its players to think more like actors than filmgoers, and in doing so, not only makes them active collaborators in shaping this specific game’s narrative, but helps highlight the ways, however tiny, in which players have always shaped the narratives of the games they play.

Cheongsam is planned for release on PC, with more details coming later this year.

Super Russian Roulette turns a beloved childhood console against you

No matter how old we get the NES is seen through the same preserved lens—that of our youthful pupils. Our bodies grow hair, stretch, they wrinkle. But that classic grey plastic will remain supple for our entire life span (it will degrade slowly, over the centuries). It remains a steadfast icon for our childhoods. This may explain why there are those that want to drag the NES through the decades with them, re-purposing it, assigning new and probably less innocent memories to its cartridge slots and controllers. Perhaps this is why Super Russian Roulette exists.

It’s a subversive piece of software in its own delightful way. It asks you to take the NES Zapper—an electronic light gun most famously used with Duck Hunt (1984)—and place the end of its barrel against your temple, and pull the trigger. No one’s gonna get their brains blown out but that’s the implied stakes of this game. And right there is its striking image: a person turning the very gun on themselves that introduced millions to the thrilling violence of videogames. It used to be that videogames invited us to take arms only to enjoy the catharsis of ballistics and murder as it was directed away from us. Now it’s being pointed back the other way. The childhood console tainted by the haunt of death that creeps up on us as adults.

“I’ve heard the cowboy-assigned nicknames stick with people long after the game is over”

Not only that, but Super Russian Roulette is a drinking game. Alcohol and death—the cardinal recipe for the games we play at older ages. The drinking rules are flexible but what is standard in every game of Super Russian Roulette is that only one player can remain by its end. And it might be that the winner isn’t even one of you sat in the room. As you all point the gun to your head, hoping to not see a giant skull appear on the screen as you pull the trigger, a trash-talking cowboy eggs you on, sometimes even turning you against each other with ridiculing chants.

This cowboy is actually one of the most impressive parts of the game. Not for the way he leans back with his spindled boots resting cumbersome on the table, displaying that distinct breed of rugged, confident, fighty masculinity seen only in the the most cocksure brutes. You’d punch him if he wouldn’t knock the living shit out of you in return. No, this fully-animated, fist-banging cowboy is the reason that Super Russian Roulette requires new cartridge hardware. It takes one megabyte of program memory to punch the NES up to the technical level it needs to host the bar brawler.

He has randomized outfits, facial hair, animations, and behavior so that every time you boot the game up with the ol’ cartridge it’s a new gloating asshole sat opposite you. He also has four whole minutes of modulated speech which, rest assured, is something no other NES game has. Thankfully the NES’s most talkative character is a charmer… oh, yeah, not quite. For real, though, Andrew Reitano—the electrical engineer that created Super Russian Roulette—says that his rowdy cowboy adds a lot to the experience:

“All of the (many many) late nights I spent programming were instantly validated the first time I witnessed the cowboy turn friends against each other, slamming their fists against the table and chanting in unison with a fictional character,” Reitano says. “I’ve heard the cowboy-assigned nicknames stick with people long after the game is over, and the players looked at each other as much as they looked at the screen which really is something magical.”

The Kickstarter for Super Russian Roulette is specifically to allow for the game to be mass-produced. Reitano wasn’t going to take it beyond an initial prototype but after it won the Audience Choice Award at Fantastic Arcade last year he was encouraged to open it up and allow more people to play it. It also helped that plenty of people apparently still keep hold of their NES systems and were contacting him to get a copy. The goal of $20,000 on the Kickstarter is what’s required to start the process that will have people turning their childhood console into an adult deathbox.

Have a little more faith in That Dragon, Cancer

The most interesting part of the discussion surrounding this year’s That Dragon, Cancer is the reaction on the part of its audience to its religious element. The Telegraph’s review, for example, expressed puzzlement at the faith itself, but not at faith as a coping mechanism. Kill Screen’s own review discussed the way in which elements of that belief were incomprehensible to those who do not buy into the essential premise. A common theme in these reviews is that grief is eminently relatable; while faith, or at least the specific permutation found in the game, is considered potentially alienating.

These same reviews only make mention of religion in the latter part of the game, when it is at its most obvious. The truth is it was always there, informing and supporting the narrative, just as it informed the real-life events that led to the game’s creation. For example, the fact that the game’s protagonists and creators, Ryan and Amy Green, named their son Joel, in the context of their belief, reflects that faith as Joel is an anglicized version of the Hebrew Yoh’el, meaning, “the Lord is God.” At the same time, it is just as valid a sign of how religion pervades the game. The videogame is, in essence, suffused in a Christian context that, like an iceberg, is only noticeable at its most dramatic and obvious points.

Grief is eminently relatable; while faith is considered potentially alienating

One of these obvious points is the presence of Grace. In Christian theology, Grace is a complicated concept, but it essentially captures a variety of tangible and intangible gifts given by God, running the scale from good health (natural grace) to salvation (sanctifying grace). The term has a history, but the short of it is this: Grace is given by God to help mankind. And in That Dragon, Cancer, the most transparent invocation of Grace comes in the two-dimensional mini-game that casts Joel’s struggle as a religious one. This mini-game is, perhaps, the more conventional experience the description “a video game about a child dying of cancer” calls to mind. Yet it serves as a microcosm of the whole experience, as the point is to lose and to experience that loss in depth. The religious element has the same experiential texture: upon reaching a jump Joel cannot make, Grace in the form of an eagle—as with Dante in Purgatory—lifts him up to a place he cannot reach on his own. But this is not the sole moment of Grace within the game. It reappears in the penultimate scene’s end, when the camera pans downward and reveals that the player, and Joel, have been resting on an aquiline mosaic the whole time—they have been literally supported by Grace.

Avian references are found throughout the entire game. The opening scene has the player control a duck, while there is a long stretch of the game that is witnessed by a player-controlled seagull. Granted, there are no doves—a common symbol of the Holy Spirit, the third part of the Christian Trinity. Nor are there pelicans, another symbol for Christ stemming from the medieval belief that it fed its young with its own blood. Still, there is a history of associating varying elements of Christian belief with avian symbols: why not, then, add a few new ones? The ducks at the local pond are an extension of God’s gift—the mundane presence of God—in the same vein as the tutelary, household deities of old. Viewed as a strict allegory, the duck controlled at the start of the game implies that the player—with their curated omniscience—is placed in the role of God, or at least operates from His perspective. In a similar vein, the player later kindles tongues of flame in a cathedral’s pews, a moment alluding to Acts 2:3 where the Holy Spirit comes and gives the faithful wisdom. This role is also hinted in how the player rarely has direct control over Ryan through a one-to-one correspondence between keyboard and avatar. Save for the Mario Kart and Super Mario mini-games, the player clicks the object that Ryan is to interact with. In essence, the player does not directly control, she merely guides.

God games have gone out of style of late. It has been just over 10 years since the Peter Molyneux directed Black & White 2 (2005), while Godus is only his and the genre’s latest failed iteration. But it is worth noting the contrast between That Dragon, Cancer and Molyneux’s productions. The latter emphasize sheer power, defining omnipotence as the literal ability to move mountains or rain fire from the sky. While That Dragon, Cancer is quieter, more subdued, and perhaps represents a more familiar understanding of faith to the faithful. For the player is not omnipotent, merely omniscient. She is a witness to grief, sorrow, and joy, watching and guiding Ryan and Amy through their trials. The player acts as God, and in doing so perhaps finds an understanding of what belief means to so many believers: a sense of presence, of company, of a witness.

Granted, this is not the sole perspective in That Dragon, Cancer, as when the camera pans into Ryan’s or Amy’s head, it is clear that the perspective is theirs. But the activity on the part of the player does not change: guidance and witnessing. However, the player’s curated omniscience involves hearing the thoughts of Ryan and Amy, an intimacy that returns nothing, a silence that marks only presence. Indeed, all of the allusions to the Bible in the game invoke this idea of silence as presence of the divine. For example, the story of Christ calming the seas is from Mark 4:35-41, and ends with the command for “peace, be still.” The quotation from 1 Kings cited by Ryan similarly carries with it the idea that God is found in these quiet, unglamorous moments:

And, behold, the Lord passed by, and a great and strong wind rent the mountains, and brake in pieces the rocks before the Lord; but the Lord was not in the wind: and after the wind an earthquake; but the Lord was not in the earthquake: and after the earthquake a fire; but the Lord was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice.

To return to Christ calming the storm, the part of this story that Ryan does not mention is Christ’s questioning of his disciples’ faith: “and he said unto them, Why are ye so fearful? how is it that ye have no faith?” This lack of doubt is one of the more pressing unaddressed questions. Indeed, if there is any event that gives rise to doubt in God’s goodness, it is the death of a child, with all its concomitant suffering and His alleged consent to that agony. Job, the iconic character from the Old Testament who represents patience in the face of suffering, is a parallel example: Job is a righteous man, but nevertheless has his property and family destroyed in a series of disasters. He cannot understand the reasons behind this utter reversal of fortune, but when his wife urges him to curse God and die in his misery, Job refuses to blaspheme. Both examples of faithfulness—that of Job and That Dragon, Cancer—are ostensibly incomprehensible responses to moments of high injustice, and yet they nevertheless demand some kind of understanding.

Christian apologist C. S. Lewis offers something of an answer to this question of doubt in a book he wrote after the death of his wife, A Grief Observed (1961). The work is more meditative than his other polemics, being as it is a collection of haphazard thoughts written at varying points while he was grieving, arranged afterwards into a coherent—though meandering—thread on his faith, his relationship with his wife, and the presumptions he had regarding both. “If my house has collapsed at one blow, that is because it was a house of cards,” Lewis wrote. “The faith which ‘took these things into account’”—that is, took death into account—“was not faith but imagination.” If a thing like faith fails when it was first tested, perhaps it was never strong to begin with. There are jokes about atheists in foxholes, but the truth may be that there are few believers in foxholes as well. Doubt, then, does not necessarily enter the picture; they are beyond it.

An intimacy that returns nothing, a silence that marks only presence

The appropriate question for That Dragon, Cancer then is not “do you doubt?” but “how can I understand this sorrow?” To ask whether faith is something to be questioned and thrown away, depending on the context, indicates an assumption of an ancillary or extraneous quality inherent to that faith, a jacket to be put on and removed when appropriate. But in That Dragon, Cancer, it is—like the eagle mosaic—the very ground upon which they walk, the only lens through which they can comprehend their suffering. To return to the analogy of the player and God, her presence is not to be existentially questioned; the fact of her presence is only to be understood. Not, “does God exist,” but “how does He operate in this moment?” The game’s answer is to present the player as neither the subject nor the object of the videogame—neither Ryan nor Joel—but merely as a witness.

Yet there is always the ultimate failure of understanding, which has been incorporated into Christian apologetics. The answer to Job’s question—after his ‘friends’ assert that he must have done something wrong (according to the logic of retributive justice) to deserve the suffering he now experiences—represents some of the more striking poetry of the Old Testament. God speaks out of the whirlwind and asks “Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? Declare, if thou hast understanding. Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest?” Put simply, God’s answer is that mankind is inadequate to the task of understanding what order there is in the world. Again, Lewis offers a useful reading of the implication of this essential inability to understand the essential order, or justness, of the world in the context of God’s alleged goodness: “What do people mean when they say, ‘I am not afraid of God because I know He is good’? Have they never even been to a dentist?”

But the player does not speak out of the whirlwind, and neither Ryan nor Amy ask why. The question of God’s presence is phrased differently, in terms of how He will act in this story. Amy is convinced that a miracle awaits Joel; Ryan is less sure. The prayer meeting (which strikes an ex-Catholic like me as, well, indecorous) provides something of an answer: the player, pressing the keys, kindles the flames of wisdom in the devout. God is not absent in this scene, but neither does the player’s performance match the hopes and expectations of the game’s characters. The player inspires—dispensing wisdom, if we hold closely the reference to Acts noted above—and bears witness. In essence, the player’s actions are in keeping with the expectation of the faithful, giving a subtle understanding of the texture of religious faith.

This idea of unarguable presence and contemplation is not the only flavor of faith, of course. But the player nevertheless moves easily into this role as a witness, regardless of her own particular theological stance, learning of Ryan’s and Amy’s belief, along with their hopes, their fears, and the particular nature of their struggle. This presence is a part of playing as god. It fulfills the promise of Paul in 1 Corinthians: “Now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” The latter part of this quote—of being known—is a corollary of omniscience: it bears with it the promise that despite the awkward miscommunications and the frustrated meant-to-says inherent to our life, there will, at last, be some kind of true recognition of who we really are. It is this promise of understanding that the game, through the eye of the player, fulfills as well as it can. The idea of knowing Joel, with his limited vocabulary and his love for dogs and pancakes, and knowing Ryan and Amy in their grief and faith is the point of this small, quiet God Game. There is no whirlwind for the player to leap from; there is only the silent comfort of sympathy, of the assurance of a sympathetic witness, of the promise of understanding. It is an experience that reflects the texture of belief.

Photo: Ludolf Backhuysen – Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers