Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 157

February 25, 2016

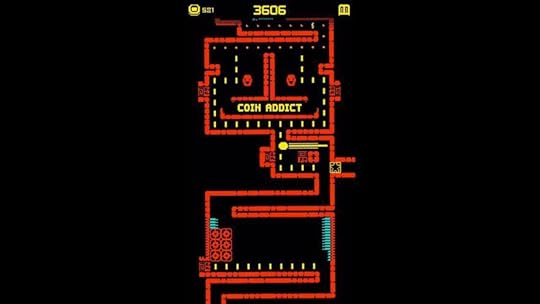

Let Tomb of the Mask consume you with its frantic death chase

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Tomb of the Mask (iOS)

HAPPYMAGENTA

Tomb of the Mask brings a new perspective to the arcade game, both literally and figuratively. Combining classic Tetris (1984) and Pac-Man (1980) aesthetics, Tomb of the Mask places you in a vertically scrolling gauntlet where the goal is to eat dots and coins while the ever-present threat of an encroaching death screen threatens from below if you don’t move upwards fast enough. You can latch onto any wall in the procedurally-generated arena which, in combination with your unstoppable momentum, creates most of the game’s challenge. Along the way, more complicating elements are thrown your way, as well as the chance to collect masks with special powers. In the same vein as Downwell (2015), this modern arcade title charms with retro FX and visual sensibilities that communicate personality more than merely nostalgia.

Perfect for: Downwell fans, arcade lovers, space invaders

Playtime: A few minutes per round

The lingering appeal of Pokémon’s greatest ghost story

The myth goes that when the first Pokémon games came out in Japan back in 1996, over 100 children who played it committed suicide. Others suffered nosebleeds or brutal headaches, or became irrationally angry when their parents asked them to take a break. Eventually, a commonality between the incidents was established—players started feeling the effects when they reached Lavender Town, home of the Pokémon graveyard, and the one dark segment in an otherwise light-hearted game.

Furthermore, most of those affected had been wearing headphones instead of relying on the Game Boy’s tiny little speaker.

It was eventually determined that Lavender Town’s music was to blame. Something about its high pitch binaural beats messed with the brains of children in a way adults were immune to. Nintendo released an updated, less prone-to-inducing-insanity version of the game and, with help from the Japanese government, covered up the entire ugly incident. We wouldn’t be speaking about it today if a single distraught employee hadn’t leaked Nintendo’s report on what they dubbed Lavender Town Syndrome, complete with a chilling line by line recap of the names, ages, and varied symptoms of its many victims.

The fact that Pokémon is celebrating its 20th anniversary instead of languishing in obscurity after being banished for the horrors it unleashed on the world should be enough to make it obvious that Lavender Town Syndrome is fake. But it’s a compelling lie, and it’s one of many alluring urban legends surrounding popular videogames. Everyone loves a good ghost story, and the Internet lets people share and build on them with ease.

The story of Lavender Town Syndrome was uploaded anonymously to Pastebin in 2010. From there it slowly spread to gaming forums and large general interest sites like 4chan, usually being rewritten somewhat along the way. Sometimes the music’s effects are an accident, sometimes they’re part of an experiment, and sometimes there are additional elements only included in the very first version of the game—a special boss fight against an undead trainer who was buried alive and who will drag you into the ground with him if you lose, being one of them. Interest in the story peaked in the summer of 2012, but it’s still searched and shared routinely today.

Everyone loves a good ghost story, and the Internet lets people share and build on them with ease

To give you a sense of the story’s popularity, searching “Lavender Town Syndrome” on YouTube produces dozens of videos ranging in views from 50,000 to over 3.3 million. There are dramatic readings of various editions of the text, debunkings and analyses of the myth, remixes of the song to make it even more unnerving… pretty much any topic you can imagine has been covered. A Google image search produces tons of fan art, some of it legitimately unnerving.

In the case of what makes Lavender Town Syndrome so compelling, part of the appeal comes from corrupting such an innocent symbol of childhood. If you grew up playing Pokémon Blue and Red, you remember that they were light-hearted right up until the point that Lavender Town introduced mourning trainers who told you that Pokémon could die. It’s not that much of a stretch to imagine that dark moment being twisted into even more unsettling tales.

It’s certainly not a stretch to imagine that Pokémon could hurt kids. Even putting aside the usual fears of games making kids violent or turning them into addicts, there is the very real incident of the Pokémon cartoon, which gave a number of Japanese kids seizures. And anyone who played a Pokémon game inevitably fell for a schoolyard rumor about it, whether it was being able to find Mew hidden behind a trick, or increasing your odds of a capture by jamming away at a certain button. Lavender Town Syndrome easily slipped in among a bevy of Pokémon myths that had been circulated for years. Except now, instead of just re-telling the story to your friends on the playground, you could immediately put your own twist on it and spread it far and wide. One anonymous stranger even made a fake spectrograph that allegedly shows a ghost Pokémon hiding in the Lavender Town audio file, a pretty ingenious way to contribute to a rapidly growing myth.

It’s that combination of interaction, corruption, and believability that you see in the best videogame ghost stories. Take Jvk1166z.esp, an infamous haunted Morrowind (2002) mod. Supposedly, it kills off hordes of NPCs outright, then has the survivors speak in portentous omens about “watching the sky.” Your health is constantly drained, there’s a creepy dungeon that’s impossible to finish, and it continues to get weirder the longer you play.

Interaction, corruption, and believability are what you see in the best videogame ghost stories

Jvk1166z.esp gained an unexpected level of pseudo-reality when some Reddit users gathered to turn it into a real mod—work that continues to this day, years after the story first surfaced. Meanwhile, those who fall for the story have been known to download a supposed copy of the mod that actually just infects their computer with malware. It’s tempting to dismiss those unfortunate people as gullible, but it’s really not hard to believe that an especially terrifying Morrowind mod is floating around the darkest corners of the Internet. After all, there are hundreds of real Morrowind mods—it almost seems statistically plausible that at least one of them happens to be unusually creepy.

Ben Drowned is another classic. While it lacks believability—even the most naïve person isn’t going to buy that a bizarre Majora’s Mask (2000) cart acquired from a cackling old man at a flea market turned out to be haunted by the restless spirit of its deceased former owner—it’s a legitimately compelling read that’s far more unsettling than a simple summary can convey. The story of the Majora’s Mask that players know and love slowly unravels into madness, being accompanied by modified video footage that features the player being stalked by a disturbing statue, creepy noises and glitches, and weird dialogue that grows increasingly ominous.

Again, it’s easy to see the appeal. For a certain generation, Majora’s Mask was a childhood staple, and it’s perhaps the darkest installment in a universally beloved series. The Ben Drowned myth resonated to the point where there’s now oodles of fan art and even a sprawling alternate reality game that adds new layers to it. It’s now a myth that’s grown more complicated than the actual story of Majora’s Mask. While Ben Drowned was written in 2010, internet searches for it peaked in 2014, and it’s still looked up routinely today.

The reason for this is due to it breathing life into an old game. Majora’s Mask is almost 16-years-old, an age when even hardcore fans who have spent countless loving hours memorizing every facet can find it feeling stale. An elaborate ghost story makes it fresh again. Suddenly there’s a whole new way of looking at the game that didn’t exist when they played it for the first (or fifth) time. The same applies to Pokémon Blue and Red, a while anyone who grew up playing these games have spent decades knowing all 151 Pokémon, they never knew that one town was trying to kill them (so goes the myth). Suddenly the whimsical childhood classic is a horror story, and a game where they thought they knew every secret is now full of fresh ones. These stories give classic games a new appeal at a time when they’d otherwise be ignored in favor of new releases.

Videogame ghost stories are a phenomenon that goes beyond bored adults making the games of their childhood retroactively spooky. There’s a whole subgenre of Minecraft (2011) stories, and that’s a game that every 12-year-old is seemingly required to play by childhood law these days. The most famous is the tale of Herobrine, a ghostly character that supposedly pops up now and then to screw with players in weird and unsettling ways. We’re told that Herobrine was secretly included as a tribute to the creator’s dead brother, and while everyone knows it’s a lie, that hasn’t stopped Minecraft fans from endlessly analyzing and building on it to the point where the game itself has started dropping Herobrine references in its patch notes. Search for Herobrine on YouTube and the first page of results has 16 videos with over a million views, including one 15-minute exploration of a Herobrine mod with a staggering 27 million views. It seems the rule is: if an urban legend is compelling to enough people, go ahead and pull it into reality.

They go beyond making the games of bored adults’ childhood retroactively spooky

Videogames have always been a natural medium for exaggerated storytelling—not just the actual plots, but the stories we tell our friends about making a difficult choice or the unusual method used to defeat a tough boss. Horror, too, lends itself naturally to tall tales—even the most squeamish and easily spooked can find themselves engaged by a campfire story. Good horror taps into a very primal fear of ours, of the dangerous and unknown. And it’s this that these urban legends surrounding videogames manage to achieve. Schoolyard rumours about unlocking Sonic in Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001) or discovering a Tomb Raider nude code can now be debunked with a quick Google search, but you can never truly debunk one of these horror stories. There’s a part of your brain that lets a fear linger, no matter how outlandish it sounds—a defense mechanism we’ve held onto since roaming the wilds. The fact that most of the original creators of the ghost stories tend to be anonymous only adds to the allure. They’re not just a chilling story someone wrote—they become a mysterious part of the Internet’s collective consciousness.

Games like Pokémon and Minecraft, being such large cultural touchstones, offer a huge built-in audience to aspiring horror writers. And that audience, instead of passively listening to the story and then passing it on to a few friends, can immediately share their additions, theories, fan art, or mods with hundreds of thousands of people. They’re modern-day campfire stories, and while the genre is still in its infancy it only shows signs of growing in popularity—the fervent fandom surrounding the Five Nights at Freddy’s series is testament to that. Maybe decades from now it’ll be the norm to gather a bunch of young’uns to tell them how, back in your day, virtual reality games didn’t exist so ghosts had to haunt physical game cartridges instead.

February 24, 2016

Genital Jousting, a real videogame about penises fighting each other

A videogame that has you and your friends play as mutant penis-butt creatures trying to penetrate one another might not sound like the most empowering female experience. But, believe me, it is. Genital Jousting began as a simple joke. At Berlin Minijam last spring, programmer Evan Greenwood (director of Free Lives, the studio behind last year’s masculine-pumped action game Broforce) set out to make a local multiplayer game with humor that was “at the expense of penises.” After teaming up with Marin Kvale (sound) and Daniel Schüler (art), they came to the understanding that watching players “chase each other around trying to have anal sex” was a multiplayer concept just “too ridiculous not to do.” (To which I say: y’all should try Tinder)

As the team explains: “A lot of the early design decisions involved drawings of penises, figuring out things like ball to shaft ratio, butthole attraction force, and the weight of balls needed to make penetration take just the right amount of challenge.” Eight hours and several buttholes later, the autonomous penis-butt monster was born.

In Genital Jousting, the goal is to get your dick wet. You are thrown into an orgy with 4-8 other penis-butts (all decked out in outfits ranging from a muscle shirt to a tuxedo) who also have the same goal. The challenge: penis-butts might be potent sexual beings, but their motor skills aren’t great (understandably, since the closest thing to eyes they have is their libido). When successful penetration does occur, however, both sexed parties receive points.

Featuring by far the most superb ass-feel ever experienced in a game, Genital Jousting celebrates couplings with a hard sucking sound followed by a straightforward declaration of “PENETRATION.” These sounds never leave you, it all perfectly capturing what one imagines a bag of dicks might be like in actuality. “Wet and schloppy when they move, super wet and explosive upon penetrating one another,” sound designer Kvale says in explanation.

by far the most superb ass-feel ever experienced in a game

“There’s an incentive to ask the other players to get inside you,” Greenwood says, expounding on the allure of playing Genital Jousting in public spaces like arcades. And indeed you’ll often find yourself yelling at friends to “Give me your ass,” or throwing in the towel with an exasperated, “Fine, I’ll just fuck myself instead.” Indeed, the penis-butt’s ultimate form is an endless schlong circle, either a singular masturbatory effort, or with all players attached ass-to-tip, resembling the most juvenile version of an ouroboros.

The team expected some hate and disgust when they first unzipped Genital Jousting onto an unsuspecting Berlin Minijam audience. They even expected some perverse love from like-minded delinquents. But what the Genital Jousting team didn’t expect was just how much careful thought their dumb penis game would inspire.

The Minijam raised concerns about consent—particularly because the initial design framed players as opponents who must forcefully penetrate each other in order to win. The team immediately set to fixing this oversight since, as Kvale says, “intention does not equal result.” So despite their initially asinine objective for the game, they added a consent screen and fixed the points system so that opponents turned into collaborators working toward a common goal (sex). They wanted to ensure the game—no matter how silly—didn’t inadvertently render trauma the butt of the joke. So now, Genital Jousting‘s message is that, as in real life, “Sex should be fun for both parties.”

The post-game jam discussion around the game also contributed to another major change for Genital Jousting. Under artist Jarred Lunt, the style transformed from anatomically correct dicks to the more playful pastel palette. Aside from the obvious hilarity of an innocent-looking game about the act of penetration, the more abstract style also landed another kind of joke.

“Making penises abject and silly works well”

“Making penises abject and silly works well because masculinity is so often portrayed as powerful and successful,” Greenwood explains when I ask about the lack of female genitals in the joust. “That same joke doesn’t translate perfectly to vaginas.” What’s more, the all-male team felt it wasn’t their place to figure out the exact mechanics of a self-propelled vagina. “That’s perhaps a game for a different team.” (And my dreams.)

While playing Genital Jousting, a famous Margaret Atwood quote kept repeating in my head. “Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.” It’s a statement that so perfectly crystallizes the absurd imbalance of power inherent to patriarchy that you almost want to laugh to keep from crying. You want to laugh—not because it’s funny—but because the truth of it makes your blood run cold.

Laughing at Atwood’s joke doesn’t make the reality any less horrific or factual. But for women—or, at least for me—laughing at it does make you feel a little less powerless. Women live their lives marred by the ever-present threat of male violence. Sure, I might still have to walk down the street alone at night, eyes darting in every direction, thumb hovering over the “SEND” button on a phone with 9-1-1 pre-dialed. I still have to humor my daily street harassers who believe it is their god given right to approve or disprove of my body in public spaces—silenced by the fear of my harassers retaliation if I talk back or, god forbid, laugh. The best I can hope for is feeling “relatively safe.” The worst I can hope for is to become the one out of five women in the U.S. who have been raped.

All of that is still true. Laughing at that Margaret Atwood “joke” doesn’t change any of those horrible experiences. But laughing at it does remind me that the basis for male violence is not female weakness, but rather the fragility of the male ego itself. It reminds me that, despite the inescapable oppression of patriarchy, male power actually stands on a house of cards that trembles at the mere possibility of a woman’s titter. If nothing else, when I laugh at that joke, I exercise the only recourse left to women. I laugh.

As women, we are made to be passive receivers of dicks

A funny thing happens when you actually play Genital Jousting, though: gender politics, violence, power—all of it melts away, leaving behind only the sound of a squelching dick as it finds a consenting ass to fill. I felt adamant about playing the game with an all-female cast. I don’t know why, but something about imposing women on a space exclusively for male penetration felt right. In real life, women are made to tiptoe around penises: love it—but don’t have it, respect it—don’t coddle it, fear it—and NEVER FUCKING LAUGH AT IT. Protected from scrutiny in movies while tits are paraded around Hollywood, yet also imposed on the unsuspecting in public spaces like the subway or Tinder, the dick dictates how and when it is exposed. As women, we are made to be passive receivers of dicks—almost never on our own terms.

So my girlfriends and I laughed (as evidenced by the recording below). We giggled as we tried to get a handle on the controls in the opening screen, watching as our flaccid worms flopped around in the consent box. We played rough, turning sex into a weapon no matter how many times I insisted that the game was supposed to be a “collaborative effort.” In a way, we were out for blood.

https://killscreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/genital-jousting-1-2_17_16-5.38-PM.m4a

“This is the source of all that fear, worry, and oppression?” is what I thought to myself, watching my pink little member squirm across the screen in search of whatever warm butthole would have it.

Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Maybe because men know that, when stripped of the power structure that puts their pricks on a pedestal, people will realize they’re nothing more than funny-looking appendages. Women are afraid men will kill them. Maybe because the pervasiveness of male violence silences us when what we really want to do is scream or burst out laughing.

Genital Jousting is a fun game. But there’s more at play than ass and dick. Because when male egos are on the line, flaccid fun might be exactly what we need.

You can find out more about Genital Jousting on its website. You can also look forward to its release (or climax, as one might say) in April.

ANATOMY is a masterpiece of cassette tape horror

The scariest part of The Exorcist (1973) for me wasn’t all the bedroom acrobatics and green puke, it was a much subtler scene. In it, Father Karras sits before large spinning reels as they playback the recorded voice of possessed 12-year-old Reagan MacNeil, all of it incomprehensible gurgled groans and anguished, hoarse throatiness. Karras wants to know what language it is and the guy who’s assisting him has the answer: “It’s a language alright.” He pauses. “It’s English.” Turns out Reagan was speaking English in reverse. It then cuts to Karras later that night, lit by the low light of a desktop lamp, a palm pressed against his head, the other hand clinging to a cup of something hot as he listens, stressed, to the voice of a demon barking at him. He’s caught up in the terror of it all until the telephone in the room suddenly rings, snapping him out of that looping hellhole.

That scene stuck with me due to the media within which the demon penetrates our reality—the cassette tape. When the devil is inside a young girl it can be conceptually terrifying, sure, but the physical performance carries the distance of drama with it. We know that this is all make-believe and that we’re watching an actress. The more plausible horror, at least for me, is in the idea of something terrible existing inside an everyday object, one that I have to hand, and especially one that so easily lends itself to being rewritten—a constant mundane horror of the ’90s was accidentally recording over the treasured contents of a VHS tape.

the terror that its visual error serves

It is this precise breed of cassette tape horror that Kitty Horrorshow’s latest game latches onto brilliantly. It is there from the start. ANATOMY opens up with a sound most familiar to me: the flapping plastic of someone inserting a VHS tape into a machine and the whining electronics that play it. A blue screen then flashes before the feature begins. And when it does, and you recognize that you’re peering into this game world from a first-person perspective, you’ll see that the distorted scanlines of a corrupt VHS tape are obstructing your view. They will never leave you.

The effect here is to suggest that you’re viewing ANATOMY as if it were on a video cassette. This isn’t an empty call upon the analog glitch aesthetic that seems to be rising in popularity of late, it’s more than that. Horrorshow says in the description that ANATOMY has multiple endings and encourages you to replay it to experience them all. This isn’t quite true, as ANATOMY only really has one ending, it’s just that to get to it you’ll need to complete and restart the game a total of four times. Each return sees the tape having degraded further as it more fully realizes the terror that its visual error serves. You dig ever deeper into the chew of the tape.

Beyond its obstreperous formatting, ANATOMY tells a more traditional type of horror story. It’s the tale of a haunted house, or perhaps, a tale of all haunted houses. Your task inside the game, at least on the first playthrough, is to wander a very dark suburban house to find audio cassette tapes. They’re each located in a room that will unlock themselves one-by-one. While the lack of lighting is enough to keep you on your guard, holding your breath while somewhat frantically searching an unknown room for its tape, the voice on the tape is what fills you with dread time and again.

Upon finding each tape, you bring it back to the kitchen where, on the table, is placed a tape player. Inserting the tape will fill the room with a gloomy monologue, it being split across all these tapes, which explains how a house can have an anatomical structure to it, much like a human body. The living room might be the heart as it is the most likely to “beat” with activity, we are told. It typically goes that a room will be explained in this manner and then you’ll have to head off to that room in the game’s house to find the next tape. Without revealing too much, it is this structure that pushes your heart into your throat, as you become so expectant of something monstrous and frightening to be held within these rooms before you even reach them, let alone when you’re inside fumbling around in the black.

Whereas a lot of videogame horror lets you walk into a room and then have a monster spring out on you unexpectedly—a cheap scare—ANATOMY whispers in your ear that there’s probably a monster in a room before you enter it, letting your own expectations grind you down to a tense wreck of a person. That it does this again and again draws the debilitating effect out, masterfully building up the terror but constantly denying you the begging release of a scream. It’s the kind of horror that gets so deep into you that it seems to scratch away at your bones. I’d liken the effect to being dragged perpetually across a saw blade. That the re-recorded VHS format means you exit the game, feeling momentary relief, but then have to force yourself to re-enter this nightmare only multiplies the anxiety. You are Father Karras caught in an agonizing loop of listening to the curses of the devil—the telephone never rings.

You can purchase ANATOMY over on itch.io.

PUP’s latest music video is an alcohol-fueled videogame riot

If great art does in fact flourish out of restraints, then it’s no surprise that the chiptune melodies of early games have so firmly embedded themselves in the hearts of the generations that grew up alongside them. This is particularly apparent in the mutual infatuation that the realms of videogames and music videos share. Just look at Bonobo’s Silver or Royksopp’s Happy Up Here videos that each clearly borrow from games, for example. The opposite is just as much true in the case of Mobigame’s mobile game Truckers Delight (2010) and Buncho Games’ adaptation of Jamiroquai’s Virtual Insanity video.

a manic, machinima mixtape of footage

The latest video for the first single from Canadian punk rock outfit PUP’s upcoming second album is the latest inductee in this hallowed roster of intermedia hat-tips. Directed by long-time collaborator Jeremy Schaulin-Rioux, DVP‘s video is nothing short of a manic, machinima mixtape of footage spanning some of the most iconic titles throughout the third generation of consoles. Mario boasting how fucked up on alcohol he is while referring a match of Punch-Out!! (1984). The reporter from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, April O’Neil, cheerily announces she’d be better off dead to a news crew. It’s a pretty bleak and eerie blend of tongue-in-cheek, that’s for sure. And it’s all paired with on-screen lyrics from lead singer Stefan Babcock’s blisteringly hoarse and sullen shouting into the pitch-black vacuum of jilted reciprocity.

The facile nostalgic pretense of the game visuals juxtaposed with the throat-parched inebriated vocals creates a feeling that radically bobs and darts along the spectrum of emotional extreme. All at once it seems to yearn for the stark low-poly simplicity of adolescence while tussling with the romantic and interpersonal fallout of arrested development.

The band’s follow-up album to their 2014 breakout self-titled debut currently has a tentative release date hanging in the amorphous window of late 2016. You’ve gotta wonder coming off the strength of this video as to whether there will be any more throwbacks to yesteryear aesthetics through a post-adulthood lens. Regardless, DVP certainly secures its place as yet another testament to the way in which games have embedded themselves in the shared imagination and visual iconography of our times. And this time it comes out shouting.

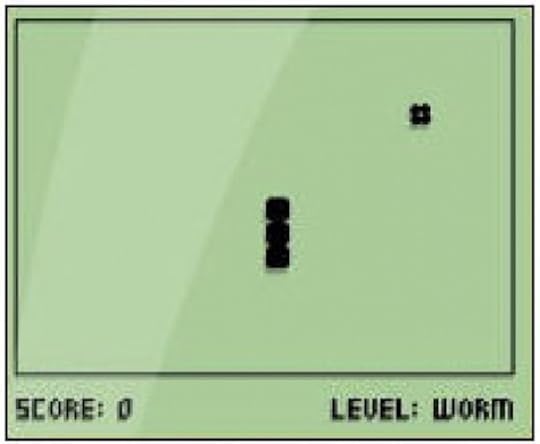

Let’s Play Snake brings the classic arcade hit to Twitter

With visuals that can be easily represented using only a line and a dot, and rules no more complex than “get to point b without hitting anything along the way,” classic arcade game Snake has become renowned for its simplicity and elegant design. This, in turn, has lead to its prevalence among a number of platforms, especially those that struggle for visual fidelity, such as graphing calculators and early cell phones. There’s even a version of it that can be played over your favorite YouTube videos. Now, thanks to web developer Yannick Rochat, Snake has been adapted for Twitter.

Rochat’s Let’s Play Snake is played through a computer-run Twitter account that takes the typically real-time game and slows it down to a turn-based format, allowing users to control which direction the titular snake moves by tweeting their desired input at the account. The account will then check for player instructions at regular intervals depending on how far the players have progressed in the game and move the snake accordingly. Fitting for Twitter, the field of play is represented entirely in emoji, with a snake emoji representing the snake’s current position, arrows behind it representing both its tail and past moves, and a mouse representing the goal. Of note is that, in a display of mercy, the original game’s restriction of not allowing players to touch walls has been removed, meaning that boundaries simply move the player to the other side of the screen, like in Pac-Man. In Let’s Play Snake, the only way to die is by colliding with your own tail.

The whole experiment is reminiscent of 2014’s Twitch Plays Pokémon, which functioned in a similar manner, allowing multiple Twitch viewers to simultaneously control a game of Pokémon by entering commands into the chat. The key difference here being that Twitch Plays Pokémon (which is still going on, despite having already achieved its original goal) had a bit more material to work with, narratively. Pokémon may not be the most complex of game worlds, but compared to Snake, its story might as well be Ulysses (1922). One of the more unexpected and fascinating creations to come out of Twitch Plays Pokémon was a complex user lore, in which players refashioned the familiar Pokémon story to suit their experiences playing the game together on Twitch. Telling legends of gods and messiahs, the religious fervor of this user-created context might have seemed an odd-fit for the child-friendly franchise, but it does make a certain degree of sense why a game like Pokémon would lead to these kinds of internet folktales. With its cuddly companions and deep-rooted nostalgia among the millennial crowd, players easily became attached to the characters they fought for control over, helping to cement Twitch Plays Pokémon‘s popularity.

Perhaps the game could more accurately be titled Ouroburos

Let’s Play Snake, working with Snake‘s trademark simplicity, doesn’t have that luxury. What it does have, however, is the chance for biting social commentary. Creator Yannick Rochat, after all, is a postdoctoral researcher from Switzerland’s École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, focusing on, among other topics, social media studies. In his developer page for Let’s Play Snake, he opens up with a quote from writer Allison Parrish reading “snake is a procedural fable that uses judeo-christian imagery to show the dangers of unchecked growth, i.e., capitalism.” These are big ideas for a game first invented in 1976, but their premise is not faulty. Snake has always been, to a degree, about the stress of success. The more food a player eats, the longer their snake’s own body will get, to the point that it serves as their greatest obstacle. From a design standpoint, it’s a wonderfully elegant way to make sure difficulty increases with skill, but it also means that in choosing to play along with the rat race (quite literal in Let’s Play Snake’s case, with its food being represented by a rodent emoji), they only get closer to consuming themselves. Worse is that, in classic arcade game fashion, Snake can never be beaten so much as just survived for a certain amount of time. Eventually, your snake will fold in on itself. Perhaps the game could more accurately be titled Ouroburos.

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬆⬜⬜

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬅⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

Kanye West and the gloriously messy Life of Pablo

Kanye West is making a videogame. Now, what that probably entails is Kanye approaching a group of game designers and programmers with, “Hey, nerds, make a game about my dearly departed mother entering the gates of heaven. And make it look dope.” Then, like, he signs off on their designs and whatnot. But you can feel Kanye’s pride when he unveiled the thing recently, and while the game’s depiction of the afterlife is as rote as can be (if there’s a hell in the game, it’s sure to be a lake of fire with pitchfork-toting imps nudging in agents, lawyers, George Bush, and other people Kanye doesn’t like), the delivery is ethereal in a way that’s fresh. And it’s elevated by the one thing Kanye is transformatively good at: music. In content Kanye is cliche; he recognizes that by deconstructing himself. But where his art distinguishes itself most is in the music. It’s there that Kanye’s mind works in great, mysterious ways.

If My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010) was Ye trying to make a masterpiece, and Yeezus (2013) was him trying to make a statement, The Life of Pablo is something entirely more humble. It is Yeezy trying to live. I think Kanye is confused as fuck right now, slipping into the supposed contentment of domestic life, getting his church on harder than ever before, having kids, knowing who he should be for those kids, accepting these roles that are both what he wants and what he is not. For the self-proclaimed “greatest artist alive,” these may seem like surprisingly mundane concerns. Kanye has always been self-possessed, but in a way that has always been disarmingly inclusive of others.

On The Life of Pablo that breaks to the next level. Here he stops trying to be a great rapper; it is a boon. Here he produces, he curates, and, sure, he raps a lot. But this is a tapestry with dozens of artists commissioned: he’s got sub-producers all over it, from major assists courtesy of DJDS, Charlie Heat, Karriem Riggins, and Boi-1da to Madlib taking over indelibly on “No More Parties in L.A.”; the vocals themselves are, at best, 75 percent Kanye, the other quarter an ever-shifting flux of guest rappers (Chance, Desiigner, Kendrick), singers (The-Dream plays Scottie Pippen), and sometimes people just saying shit, like on “Low Lights.” And yet what this entourage is weaving isn’t something grand. It’s something intimate, and it shifts on the wind of Ye’s whimsy—for The Life of Pablo is as much the dynamic, mutable nature of its own process as it is an actual document. Its confidence is supreme but also self-questioning, editing, revising constantly; even as it changes, though, Ye always comes back with the tested answer that, yes, he is the greatest, always has been, and so is this record. It’s a picture of Kanye, an honest and complete one, superimposing the halcyon, sample-bred nascence of The College Dropout (2004) over the decaying electro-bones of Yeezus (check when the Nina Simone loops drops in on “Fade”). It is a picture of one both possessed and anointed.

Opener “Ultralight Beam” is primo Philip K. Dick, channeled in a Kanye West jam, a surrealist, drug-addled hymn that would pair just lovely with four, five tumblers of scotch and Valis: “We on that ultralight beam / we on the ultralight beam / this is a God dream…” It’s a track held together by the most simple of production foundations, but it billows outward towards the diaspora of voices it seeks to encompass: a gospel chorus, guest rapper, singer, sampled child, sampled pastor, Ye himself. You can feel a million more voices beneath the surface. God’s dream, indeed. The thump of an intermittent drum and the synth horn that carries Chance’s incredible verse upward in its last few bars are Ye dabbing in masterstrokes I don’t think he fully comprehends. He just does, following his prodigious intuition, following the ultralight beam that burrows inward to the God buried beneath endless strata of human shit. Looking for “more faith,” or something that is more than faith.

It is a picture of one both possessed and anointed

On “Low Lights” the preaching poem is offset by a melancholy use of staggered chords. On the acapella “I Love Kanye” a joke track becomes increasingly meta and strange; Kanye is no longer capable of looking in the mirror without his brain writhing into an ouroboros. “I Love Kanye” has no place on a great record, and yet here it is on one, thrown in, fecklessly. Again, Ye’s process and Ye’s instinct overwhelm inhibition, even as the form of his art shapeshifts anew and anon. Where Ye’s excess once expressed itself through layer upon layer of production, here it has boiled then simmered down into an inch of dense reduction, nigh black with an oily rainbow sheen on top. The excess comes when Ye then splashes that shit everywhere. On The Life of Pablo, Ye fucks with the song structure, the album structure, hard and without reservation; no longer spilling over the margins of the mansion walls, he’s excavating the foundation and laying the bricks out in Stonehenge-esque bricolage.

The self-awareness at the heart of tracks like “FML” and “Real Friends,” which is as devastating a 1-2 as Kanye has ever made, is the best kind of portraiture because it is not confessional, it is bluntly observational. Ye hasn’t been this directly relatable nor his music this emotionally tonal since he was making tracks like “Through the Wire.” That feels like a long and happier time ago. Yeezus failed in large part because it was Kanye trying to tap into one thing, into his “righteous” anger, and making something messianic out of that when he lacked the grace to do so. The Life of Pablo doesn’t single out any one emotion, is neither aspirational nor seeking to be inspirational.

And while Kanye’s dick is a central, recurring character in its narrative, The Life of Pablo is also very in tune with all the other parts of Kanye, too. Somewhere in that sum it starts to paint a thing that kind of looks like a soul, without having to proclaim the soul is there the way Kanye would do on his past work. I mean, Kanye still does that on “FML,” but this time you believe him because of the way it sounds. This isn’t the sermonizing of “Jesus Walks,” it’s that track’s drum line. It’s the inflection of the rap’s one most impassioned moment. Vis-a-vis the sonic breadth of Ye’s ego, this isn’t the golden morass of “We Major” or “Power,” it’s that shine blast-fractioned off into a sinuous series of glints. This is The Life of Kanye and Pablo is referenced because Kanye’s still chasing something bigger and badder than himself. Only now he knows it’s only a God dream. Which is “everything.” Kanye’s just found a new, more potent way to talk about everything, and that’s to let the music do the real talk without talking over itself. But it talks a lot, and it talks hard.

There are “bonus” tracks here that are no longer bonus tracks, Kanye making the distinction himself and then destroying it. Gorgeous “30 Hours” is a long outro, with an ad-lib track akin to “Chonkyfire”—and it’s not even remotely the last track. It also contains a microcosm of what’s so vital about The Life of Pablo in that Kanye invokes Andre 3000 with “Three Stacks,” then Dre shows up to do fuck-all but say the track title at the end of the measures, while Ye inserts scat-filler in lieu of actual words and then, apparently, decided that was plenty good enough. And he was right. It’s so goddamn beautiful it will make you ache. You will hear your own love for Andre 3000 and Kanye’s love for what Andre 3000 sounds like. It is good.

At best, it’s an oneiric logic

The Life of Pablo, indeed, is built on this premise: that it will be good. The logic of what’s on The Life of Pablo and when and where and how Ye chooses to end the record (that is where you put “No More Parties in L.A.,” “Facts,” and “Fade”?) … I mean, at best, it’s an oneiric logic. Which, in art, can be the best logic. And Kanye makes batshit production choices (like the practically atonal coda to “FML”) because again, he has utter faith that it will be good. This faith is empowering. It renders The Life of Pablo the most daring entry in a discography not lacking in, er, audacity. It is Kanye owning what could be viewed as mistakes, for his life is basically made of mistakes, and exalting them—as part of the God dream. Kanye has found the key to artistic self-validation: bold, unmitigated, probably insane belief, belief so absolute it becomes hardwired into the self. Something more than faith.

It couldn’t be right to call The Life of Pablo Kanye’s best record, could it? Shouldn’t we let the honeymoon pass? And isn’t The Life of Pablo too erratic, too drunk, too scattered, too crass, too much about Kanye’s dick? But it is his most challenging record. And his most secretly rewarding. His funniest, most subversive record, and his most eclectic and self-comprehensive. His weirdest record and most off-the-cuff, off-the-dome, off-the-track of the path to greatness that Kanye was trying to blaze. His most sincere record, most in-the-moment. It is the record that is the least about him rapping, about him telling us—be it through a million grunting verses, or Auto-tune, or the mad stare and spit of his last record—and most about the music that haunts him, and him showing us that. It is his most Kanye record, but also his least Kanye record in that it is his most internally disconnected but his most externally connected, his most resonant. For Ye tragically self-isolates even as he thirsts for community and fraternity and love, he knows no other paradigm and no other way to be, but now from this space comes forth a tortured beauty, whereas before there was often just a pompous sort of beauty (most everything before Yeezus) or torture (Yeezus). There are a lot of ways to judge art, and by many of those measures The Life of Pablo is a bit of a hot mess. Myself, I always try to find the essence of the artist in the work, or the work’s essence in itself, and what about that is essential. The Life of Pablo is on that ultralight beam. I know this not because Kanye tells me it is but because, for instance, the beat switch at the end of “Famous.” The divinity is self-evident.

The iconography, the rap memes, the boasts, the insecurities, the persona, the T-Swift teasing, the Kanye dick on display here…all just contextual particulate whirling on the movement of the music. The music that makes Kanye speak, that makes him create, that made “All Falls Down” and “Can’t Tell Me Nothing” and “Runaway” and now this. That makes him essential. For the first time I feel like he and I share the same fabric, are part of the same thing. Faith is restored. I will play his fucking videogame. It will be good. My life will hurt as it always has, and it will be good, like Kanye’s. I will inevitably fail my kids like Kanye will inevitably fail his, but somehow it will be good, I believe, if we share this with our kids and everyone else we know, if we believe things can and will be good even when those things are fucked and damned to hell. Because we hear the music. Because we feel the ultralight beam. And I hope God never wakes up.

Two Interviewees takes aim at employment inequality

Two interviewees, both alike in aptitude, both attendant on the Internet where we lay our scene. One’s a man; the other’s a woman. You know how this goes.

Two Interviewees, a narrative game created by Mauro Vanetti, does not flip the script. That’s the point, really. Equality would be a shocking narrative turn. Fairness would be truly revolutionary. Equality and fairness are not to be found here. What can be found is a split-screen: a male candidate is on the left and a female candidate is on the right. They have identical CVs. You watch over the shoulder of an HR rep as identical backgrounds and answers lead to radically different outcomes.

In terms of its visual conceit, Two Interviewees is brutally effective. The interviewer’s notes are displayed on computer screens. The items from each interview are vertically aligned, allowing for a quick comparison. Think of it like a balance sheet, with credits to one side and debits to the other. Think of it like a balance sheet, because one of these interviewees will likely bring home far more over the course of his career than the other.

There are limits to what can be conveyed in a two-minute game. Two Interviewees largely passes over the subtleties of the coded language and expectations that result in hiring inequity. It takes very little to set off the game’s “she wants a baby”-alarm bells, which services a larger point, but the game has no space to explore how this process works. But who really cares about subtlety? Study after study has found that equivalent candidates do not experience identical outcomes; Two Interviewees makes its point effectively and gets off stage without overstaying its welcome.

Hire this game.

Digital Soloists: Jazz and the videogame score

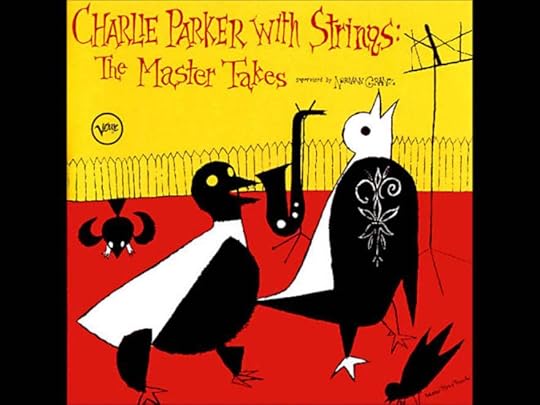

Rain gently pours outside the window. The detective crosses the room, bottle and glass in hand, and sits on the couch. He stares at the portrait of a beautiful woman. She’s the victim of the crime he’s investigating. A sense of mysterious infatuation permeates the room, emphasized by David Raksin’s score for Laura (1944). The famous apartment scene, a classic of 1940’s film noir, could only achieve its status with the help of music.

Laura’s main theme is appreciated not just for its functional aspect in the film, but for its quality as a well-written tune on its own terms. At the time of the movie’s release, the song caught the attention of the jazz scene, especially of legendary saxophonist Charlie Parker, who would years later record and release it in his critically acclaimed Charlie Parker With Strings, posthumously released in 1995.

Jazz provides a wide range of possibilities to interpret and give different twists to a song. Under the spotlight of Parker’s jazz score, Laura dances and morphs herself into multiple, winding melodies, but that’s not the only way a jazz musician can look at her. Take, for instance, Dexter Gordon’s version of Raksin’s recognizable theme, recorded and released as the opening number for 1977’s Sophisticated Giant: the symphony orchestra—a favorite among Hollywood composers—gives place to an 11-piece band largely composed of reeds and horns accompanied by a rhythm section.

Gordon’s skillful playing of the tenor saxophone takes the music to different and unexpected directions while it elevates him to the status of what double-bassist Charles Mingus would call a spontaneous composer—as jazz supports itself mostly on musical improvisation. By means of his newly created melodic combinations, the performer not only shows us different perspectives but also dialogues and adapts himself to a responsive medium, the musical accompaniment, to accomplish his intentions.

This so-called spontaneity is, perhaps, what captivates me the most in jazz. The ability to perceive multiple paths in order to take the listeners’ ears and minds to numerous places in a short amount of time. It’s this process that I compare with my experience playing videogames, where I find myself reacting to a number of details in a digital space while making decisions all the time.

jazz provides a wide range of possibilities to interpret and give different twists to a song

The jazz soloist interacts with multiple factors to blaze her trail. For instance, when playing in a band, it’s fundamental for her to listen to what the other members are saying through their instruments, as they also pay attention to her solo. Compare it to a conversation where you must hear what the other person is exposing to formulate appropriate responses. Also, if we focus on the performed piece of music itself, its features give a lot of possibilities to the interpreter. Listen to Bill Evans’ solo rendition of the traditional Irish tune Danny Boy. Instead of playing the original chords, the pianist chooses to substitute them in order to put the tune in a new perspective while maintaining its melody.

Like in jazz, we pay attention to every detail that videogames offer to us so we can explore and enjoy the most of them. For example, we learn tips from text boxes and avoid any potential harm. Our understanding of these elements is very personal. The pianist Herbie Hancock says that “jazz is a dialogue. Recognizing that that person is worthy of having their own creative expression of life. So, you don’t judge it, because it’s theirs.” In digital spaces or interactive art, our own way of “creative expression of life” overflows as we slowly discover what is being offered to us. In other words, we stand as soloists in an interactive space, and music highlights that experience in electronic gaming.

Videogame soundtracks, throughout their history, have walked hand-in-hand with technological advancement. In the 1980s, game music started as a repetitive sound accompaniment, commonly known as loop music, for each stage presented in the title. Even though this musical form persists as an effective model of game sound, at the time, it didn’t fully respond to the player’s actions. Sound designers and composers began to experiment with this matter in the 1990s when rudimentary systems of adaptable audio started to be used in games. For example, when Mario mounts Yoshi in Super Mario World (1990), a percussive rhythm pattern is added to the music. Nowadays, these systems have been fine-tuned in order to give sound professionals more possibilities. When fighting Obello, a giant poisonous mushroom in Titan Souls (2015), the whole musical background changes when the player is poisoned, its arrangement becoming a lysergic sound trip.

Fundamentally, the pursuit here is concerned with how game sound could establish more refined means of interaction with the player. Similarly, jazz musicians developed different forms of responding to sound through experimentation. Just listen to Ornette Coleman’s approach on collective improvisation, where performers assume the role of soloists simultaneously, or, more recently, Makaya McCraven’s 2015 release In the Moment.

I am often reminded of my position as a soloist when my friends and I stumble upon decisive situations in a videogame. As a fan of role-playing games, which often present narrative crossroads in their development, it was interesting to discuss which options my colleagues picked up along their way, as we also talked about the best strategies to defeat particular enemies—again, an overflow of our “creative expression of life.” Also, we used to play a lot of competitive multiplayer games like Team Fortress 2 (2007), where each match presents itself in a singular way. As a team, we had to know each other’s limitations and characteristics as players to overcome our obstacles while communicating tips to help one another adapt to each situation. It’s like we were a jazz group spontaneously composing melodies, even if, a lot of time, they didn’t turn out as hoped.

how can game sound establish more refined means of interaction with the player?

As much as jazz has been a genre that developed itself through collective creation, it has also been a multicultural form of musical expression. Its roots mostly lie on blues and Afro-American work songs, gospel hymns, and ragtime piano. Later on, it absorbs the influence of western classical music—Charlie Parker quotes Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in his solo on Repetition—and of other popular genres, like its merging with rock promoted by artists like Miles Davis, Weather Report, and Return to Forever. Guitarist John McLaughlin, founder and lead member of Mahavishnu Orchestra and Shakti, is one of jazz’s most iconic figures when it comes to the amalgamation of Western and Eastern music.

Along the same lines, jazz has lent its characteristics to other genres around the world. Paco de Lucía, who had previously played with jazz guitarists Al di Meola and aforementioned John McLaughlin in Friday Night in San Francisco, incorporated some of this contact to his flamenco in Zyryab—also, the renowned pianist Chick Corea plays on this record. South American musicians, who exported rhythms as bossa nova, tango, and samba to the Northern hemisphere, also assimilated this influence. Names like Antonio Carlos Jobim, Egberto Gismonti, and Astor Piazzolla come to mind.

Either by in-game necessity or by the influences of its composers, game music emerged from a multicultural cauldron as well, even though we cannot contain it in a specific genre. Think about the diversity of styles we find in videogames: in the 1980s, Koji Kondo’s funky hit theme for Super Mario Bros. (1985) coexisted in the Nintendo spectrum with Hip Tanaka’s Alien-esque score for Metroid (1986), an assortment of musical pieces influenced by contemporary western classical music. They were both Japanese composers working for the same company, yet, they extracted their desired sound from distant musical universes.

These cultural exchanges can make us observe genres under very particular angles. Take, for instance, Yasunori Mitsuda’s theme for Arni Village in Chrono Cross (1999). To write a tune reminiscent of the lead character’s home, the Japanese composer chooses the sound of the Portuguese fado guitar to create the desired atmosphere. In the composer’s words, published in the Chrono Cross OST album’s liner notes: “As the theme for the first town in the game, I injected a feeling of sunshine and brightness to it, something with a good atmosphere. I felt that the fado guitar would be and excellent choice to bring out that feeling, even though traditionally the image of the fado is one of sadness and sorrow. But I realized it can bring out the cheeriness of a song.”

In this case, Mitsuda transforms his knowledge of traditional Portuguese music into something renewed and conflicting—since, as the author remembers, fado is a genre usually associated with negative feelings. And apart from its narrative context in Chrono Cross, it stands as an appreciated tune on its own merits.

As I go back and remember Laura’s apartment scene, I remind myself of how dramatic music was taken out of its context to become an instrument of expression in the hands of jazz musicians. Now, it seems fitting to me that game music conquers this kind of space, especially if I consider that if jazz is open to various interpretations, so are our very own experiences with videogames.

Header image: Adi Holzer Werksverzeichnis 899 Satchmo (Louis Armstrong) via Wikimedia

February 23, 2016

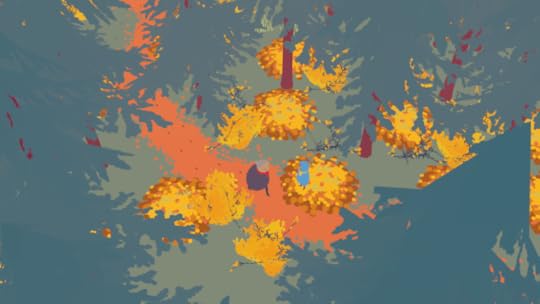

Look out for this beautiful tribute to sweet, caring grandmothers

“My grandmother is probably the most important person ever to me,” writes illustrator and game maker Florian Veltman. This text appears on the website for his latest game—it’s to be called Lieve Oma, the Dutch for “Dear Grandmother”—which Veltman confirms to me will very much be framed as a letter to his grandmother. But rather than have us stare at an inked page, Lieve Oma gives us an autumnal forest to explore, in which we play a young girl who goes mushroom picking with her grandmother.

Lieve Oma originally started out dedicated to the people in our lives who give us the stability and space we require as a child to grow. But this basis only lent itself to hitting generic, broad notes and lacked a distinct personality. Hence Veltman decided to spin it with an autobiographical angle, basing the interaction between the two characters on his relationship with his own grandmother.

“probably the closest I get to actually making a portrait of my grandmother”

Due to this, Lieve Oma will be dialogue-heavy, as it is mostly in the words, but also the behavior, of the grandmother in the game that the child finds a form of comfort. Importantly, this dialogue isn’t there to create a narrative arc; it exists only to divulge the sensitivity of the moment. Indeed, Veltman further says that the mushroom picking is only a pretext used by the grandmother to help the child get her mind off other matters. It seems there are shades of something darker happening off-screen, probably back at home, away from the joyful mounds of shrubbery and fallen leaves. The text on the website tells us that this little girl knows that grandmother only brought her to this forest “to get [her] to talk about what’s actually going on.”

Beyond the dialogue, Veltman is finding that drawing, sculpting, and “grooming” the game’s forest is serving as another way to pay tribute to his grandmother. “[I] feel like working on the forest is probably the closest I get to actually making a portrait of my grandmother,” he tells me. “Not because of the ‘autumnal sunset colours’, but because despite what it may evoke on the surface, everything still seems very vibrant, warm, and pleasant.”

The forest is surely the game’s biggest immediate draw, with a range of blobby auburn afros sitting atop the trees, and golden brown pools of leaves dotting the ground. It’s all meant to evoke the “bittersweet mood” that Veltman chases, especially as these seasonal colors visually contrast (though not harshly) with the peachy-pink ground. That almost any shot taken directly in-game is pleasant is testament to Veltman’s work here.

Speaking of which, being an illustrator who learned the craft among the vibrant scene in France, Veltman is especially interested in what every color selection and object placement brings to the image and the eye. He’s found this process relaxing, helping him to recover after a burn out, which occurred as he worked on making a new version of his team-built game jam entry Endless Express. He needed something comforting to help him through the aftermath, and as if by instinct, he turned to the softly-spoken solace of his grandmother.

You can follow the development of Lieve Oma on its website and on Veltman’s Twitter account.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers