Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 154

March 3, 2016

A classic arcade game gets the SUPERHOT treatment

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

PUSER TOH (PC, Mac, Linux)

SOS SOSOWSKI

With the arrival of the Polish-made first-person shooter SUPERHOT, fellow Polish game creator Sos Sosowski decided to make a small tribute to the game’s “time only moves when you move” concept. But rather than make another shooter, Sosowski applied the principal to classic videogame Pong (1972), making for a surprisingly fresh result. In PUSER TOH (an anagram), moving your paddle up and down the screen causes the ball to speed up, while keeping it stationary results in the ball travelling very slowly. It means that you have to better anticipate the ball’s trajectory as it flies towards your paddle. However, this is a two-player game, and so being able to control the speed of the ball in the air gives each player a new way of outdoing their opponent. It also fills what was previously a brief period of downtime in the original Pong with a whole new interaction.

Perfect for: Arcade addicts, bullet dodgers, any pair of friends

Playtime: Seconds a round

The Outsider Art of Dominions 4

In 1947, French painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet coined the term art brut, or “raw art” when translated to English. It was used to describe, by his own definition, “Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses—where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere.” He was interested in art made by people who had never graced the halls of art school, who shunned the company of fellow artists and drew no influence from popular trends. In an art world plagued by repetitiveness and inauthenticity, Dubuffet argued, only the work of those totally outside society could be truly original. Children and people with mental health problems topped his list of favorite artists; he was dedicated to the movement that would, eventually, come to be known as Outsider Art.

///

While the world of videogames is wider and weirder than it’s ever been, taken at a distance, a lot of it begins to look familiar. 2015, for instance, will likely be viewed as the year of the open-world role-playing game, with a smattering of the usual guy-shooters thrown in. Like any art scene, videogames are influenced and inspired by whatever’s being made and published in the same environment. This results in patterns, trends, and a lot of iteration of similar ideas—all natural things for a medium, and all things that Dubuffet despised.

Now, I don’t pretend to know what games a particular 20th century Frenchman would have enjoyed, but his definition of Outsider Art helped me understand one of the most enigmatic, mystifying games I’ve ever spent time in. The seeds for the first Dominions (2002) game were, as per Dubuffet’s qualifications, planted in solitude. Kristoffer Ostermann, one of the two creators of the series, was taking a 1000-mile hike through Spain and France. He had a lot of time, he writes in the Dominions 4 (2013) manual, to think. At some point over the seventy two days it took him to walk that distance, Ostermann conceived of what might be the most unapologetically complicated strategy game ever made.

As of writing this, I am in a multiplayer game of Dominions 4 with 13 other people, only two of which I actually know. I was invited by a friend, who I presume was also invited by a friend; word-of-mouth is the game’s most successful marketing strategy. Since there’s no dedicated single-player mode and matches against the computer feel a little too purposeless to be sustainable, big multiplayer games are where Dominions 4 really shines. That makes it all the more baffling that there’s no easy way to do this. Online matchmaking is non-existent, and there are no servers dedicated to actually hosting games. In our friendly match, the host is currently running two instances of Dominions 4 on his computer—one to host the game, and one to actually play. For some reason, you can’t do both in a singular effort.

THE MOST UNAPOLOGETICALLY COMPLICATED STRATEGY GAME EVER

Turns happen simultaneously, about once a day after everyone has plugged in their orders. It’s closer to play-by-mail chess than most modern videogames. This match will be over in several weeks, give or take. By then, plenty of people will be knocked out by the deadliest enemies of all: frustration, monotony, the many-faced duties of adulthood, and the siren call of other, simpler games. I imagine I will not be among these lucky few as my time in this game is looking to be briefer, and a good deal more violent. To explain: I began this game in an unfortunate situation. While I’ve played about 20 hours of Dominions, the player to my east has spent over 200 hours in the game. Doubly worse, I have no idea what he’s capable of. He was playing Patala, a faction vaguely based on mythology concerning the Indian underworld. I knew he had snake people and monkeys at his disposal, but I didn’t know what the hell monkeys or snake people could do. I had never encountered or even heard of them up until then. This is a big problem for me. To take a detour in service of my point, here: MMA is, by many people, considered the most difficult sport in the world. That has more to do with its complexity than physically punishing nature—fighters pick their focus considering their own weaknesses and those of upcoming opponents, since no one has the time or talent to learn it all. A similar principle holds in Dominions 4. The person with the most knowledge (or time to acquire it) usually triumphs, but I’ll go ahead and say it’s practically impossible for any one person to know Dominions 4 inside and out. That includes, amazingly, the creators themselves.

Much of the development of Dominions has been additive. The first Dominions game was released in 2002, and the creators at Illwinter Game Design have been adding features to the game in one form or another for over a decade. It’s gotten to the point where even they don’t remember what everything does. “There are countless rituals, combat spells and other special abilities in the game,” said Johan Karlsson, the main programmer on the two-man team. When he says countless, he literally means that they aren’t sure how many there are. “I’m actually surprised by what some things do now and again, even though I programmed it.”

The driving design principle seems to be content above all else. It’s spelled out on the Illwinter website: “Animation sequences are intentionally kept simple to allow us to stuff more monsters and spells in the game than any other game, except possibly a roguelike. They don’t have any graphics for the monsters after all,” reads two of the four sentences in the meager ‘about’ section. Of course, doubling down on content above all else is hardly breaking rank in the world of game development, but the sheer quantity and way in which those things interact, somehow pushes Dominions into an oddly magical kind of territory.

I still remember one of my first games of Dominions 4. I was playing the relatively beginner-friendly nation of Abysia. I had mopped up in the early game, claiming vast swathes of territory with my army of lava people, who were well-armored and damaged the soldiers of other nations by proximity alone. I had backed one player into a mountain range and prepared to finish off his remaining troops. Then it started to pour. He had cast a spell summoning a storm and, drenched in cold rain, my lava people got a lot less dangerous. The best part was, I had no way to know that spell would interact with the Abysians in that way. It’s entirely possible that my opponent didn’t know either, and were just favored in their experimentation. In its fourth incarnation, Dominions has over 1500 units, 600 spells, and 300 magical items, and it doesn’t give a shit whether or not you ever see them. There’s never been a tutorial for the game. When I asked why that was, Karlsson said that “it would take time to implement. I would much rather put that time into making some new rituals or something else that makes Dominions a larger and better game.”

CONTENT ABOVE ALL ELSE

It seems almost compulsory the way Illwinter continues to pack new things into the game. But why was that their approach in the first place? From talking to the pair at Illwinter, it seems as though they created Dominions so that they could play Dominions. “It’s just obviously a good thing,” said Karlsson about the neverending firehose of content he’s been spraying into Dominions for over a decade now. “I always like to discover and try out new units when I play a strategy game.” Much of the theming of the game’s nations, from the Mayan underworld Xibalba to the Nordic Vanheim, seems to also be pulled more from personal interest than any other considerations: Ostermann, when he’s not making inscrutable strategy games, is a professor of Religion and Mythology.

Dubuffet’s vision of art brut was not art made in the style of art, but art that came from something untouched by culture or society within the artist. More than anything else, this is what cements Dominions as perhaps the most compelling piece of Outsider Art in the realm of game design. By so resolutely following their own vision of what they wanted to see in a game (which was, it seemed, “everything”), Illwinter has tunneled down through the crust of good, safe game design and emerged into a molten core of pure conceptual realization. Somehow, it does that humbly.

Dominions is a game that will only be enjoyed by a fraction of people; most won’t get through the brutish, horrifically neglectful first turn screen. Even more will be bucked by the difficulty curve, or even the challenge of finding a single person to play with. But those who stick around will find something wholly unique; a game where even the developers don’t know everything there is to know. Those lucky few that survive the gauntlet will find a bottomless well in which to jump.

Dubuffet header image via Flickr.

Screenshots via Illwinter.

March 2, 2016

Creators of The Novelist want you to avoid freezing to death next

Orthogonal Games, the studio behind 2013’s The Novelist, has announced its next project, called Near Death. It presents a simple premise: Your plane has crashed in Antarctica. You’re cold, you’re alone, and it’s dark. There’s an abandoned research station within walking distance. Try not to die.

It’s an effective hook, evoking the excitement and immediacy of the first BioShock‘s (2007) opening sequence, in which the game’s protagonist finds himself half-drowned in the middle of the Atlantic only to see a mysterious lighthouse in the water nearby. The major difference is that Near Death has no Rapture (the game’s underwater city) for its protagonist to stumble across, escaping from the deadly environment around them. Instead, it holds them in initial climate and it proves to be a constant threat; light is scarce, heat even more so. To survive, players will have to mark trails, melt frozen obstacles, and find fuel for their portable heater. Your lights flicker. Your body shivers. You are fragile and the storm outside does not care.

The other obvious cultural touchstone that Near Death evokes is John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). It, too, centers around an Antarctic research station cut off from the outside world in the middle of a storm. Both stories isolate their characters in whiteout conditions, juxtaposing the personal intensity of their struggles with a vast and cold wilderness that makes their concerns feel petty in comparison. A key difference, however, is Near Death’s apparent lack of a villain, whereas the characters in The Thing are forced to contend with the titular alien monster. Rather, Near Death focuses on a more primal fight to survive, elevating the game’s environment beyond set dressing and into antagonist.

You are fragile and the storm outside does not care

Perhaps more important, however, is Near Death’s smaller cast. If The Thing is ultimately about how a group of supposedly close friends can be turned to hate and and mistrust when confronted with opposition, Near Death is about being alone and scared. The drama presented here isn’t a story of group dynamics, but of individual fortitude.

This marks a drastic shift from the studio’s previous work in The Novelist, in which players take control of a ghost as it haunts a writer and his family, balancing the conflicting concerns of family members against each other to try to find an acceptable compromise. In The Novelist, tension comes from the stress of being beholden to others, which, on second thought, perhaps captures the group conflicts of The Thing better than Near Death’s scenario. Instead, Near Death foregoes the terror of others to focus on the terror of the self. A lonely mind stranded in a wintry desert is plenty capable of paranoia on its own.

You can keep up with Near Death over on its website.

The Art of Escape

This article was funded with support from Longreads members.

* * *

No one wore stripes that spring and summer in Leavenworth. Stripes were for rule breakers, and no one was breaking the rules. “Baseball As A Corrective” read the front page of the New York Times that May. It was 1912 and “the magic of baseball” had “wrought a wonderful change in the United States Penitentiary.” For the first time in Leavenworth’s history, for months at a time, everyone behaved, because everyone wanted to play or watch the baseball games. “Chronic trouble makers began to be so good that the officials were startled,” the Times reported. Prison guards were planning more amusements for the winter, “such as vaudeville entertainments and moving picture shows, to keep the men on their good behavior.”

Understand that at the root of punishment in America and its long strange history lies shame. For decades into the 19th century, we didn’t incarcerate, didn’t lock people up, put them away, out of sight, like today. Just the opposite: They went on display, placed in stocks and cages, tied to whipping posts, marched to the gallows or hanging tree where their beaten bodies remained for days afterward. Sometimes, in small colonies or towns surrounded by wilderness, repeat offenders were banished, but mass banishment into prisons was not embraced as an institutional form until the 1820s. Until then, public shaming was the central mode of punishment in America, for it was only through shame that one may find forgiveness and, eventually, redemption. In America, where spiritual belief has been refracted back into political culture from the beginning, sin is crime, and crime is sin. Mark the sinner. Make her wear a red letter, make him wear stripes.

Adam Lovell is the president of WriteAPrisoner.com, a company that helps match prisoners with pen pals and pen pals with prisoners. He writes a newsletter every month and sends it to some 1,500 of these letter-writers, inside and out. In April, he included an item titled “Video Games & Inmates.” “Does your incarcerated loved one or pen-pal play videogames while incarcerated? How about before they were incarcerated?” He told his letter-writers to “get out your pen and paper and ask your inmate if they’re a video gamer,” and he included my email, to get in touch.

Hester Prynne & Pearl before the stocks by Mary Hallock Foote, 1878

My reasons for wanting to get in touch were not, I’d told Lovell, moralistic. Maybe anthropological was the right word. Or aesthetic. I wanted to know what it was like to play videogames in prison, or think about videogames in prison. Or just: be a prisoner, who also identified as a gamer. The question of whether it is right or wrong to allow prisoners to play videogames—to give an incarcerated person access to this form of entertainment—was not interesting to me, then.

Dozens of people wanted to talk, but talking was difficult. Time was limited, phone calls and emails expensive (one four-minute call cost $18; a single email $3.50; when I was able, I reimbursed inmates for their time and efforts). Most didn’t have access to videogames in prison, but had been gamers before. They dreamed about games, they said. Ed, who was serving out a ten-year sentence for possession of a stolen firearm, wanted to hear about what videogames were like now. He’d been inside for five years, and had two more years, he hoped, with good behavior. “I wasn’t paying enough attention to what I was playing when I could play,” he said. “I wish I had been paying more attention to a lot of things.” Another prisoner wrote to say he dreamed about the cheat codes you could make on games, the way you could walk through walls in Doom, and dreamed of doing that here, inside, just walking through walls until you were out.

The change to the US prison system that ushered in the era of banishment was brought about by fear, the same fear that today has turned the United States into the undisputed world champion of locking up young black men. In the 1820s, the argument was the same: these individuals (young, recent immigrants, minorities) were a threat to family and society and so must be removed and reformed through solitude, order, and control.

Understand that at the root of punishment in America and its long strange history lies shame

The most expensive and famous prison of all was Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, which opened in 1829. Each cell was vaulted and skylit: “only the light from heaven, the word of God (the Bible) and honest work (shoemaking, weaving) to lead to penitence,” reads the prison’s history. De Tocqueville visited in 1831 and wrote, “Can there be a combination more powerful for reformation than that of a prison which hands over the prisoner to all the trials of solitude, leads him through reflection to remorse, through religion to hope; makes him industrious by the burden of idleness?” Charles Dickens visited eleven years later and found the prison’s intent, borne out of the Quaker’s own sequestered forms of punishment, to be in purpose “kind, humane, and meant for reformation.” And yet, in practice the “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain” made such solitary confinement “immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.” By 1909, Eastern State had loosened its single-cell model. Prisoners were gathering in group workshops on occasion. They even had a newspaper, The Umpire, that ran almost nothing but rosters and scores from the prison’s baseball league. Four years later, Eastern State abandoned the single cells that had made it famous.

Two inmates, Christopher and William, wrote to me. They were working on the development of a new videogame together, though the pair didn’t have access to any videogames where they were held, in Buena Vista, Colorado. Well, they did, they wrote, but “games are played on tablets that are sold on Canteen at inflated prices,” and the games were extremely basic. Christopher said he held a bachelor’s degree in Game Art and Design, and was “versed in 3D Max, Maya, Illustrator, Photoshop and Flash.” William, for his part, was “much more adept with functionality and playing of videogames.” They, too, wanted to hear about what I was playing, what games were exciting, and didn’t want to discuss the details of what they were working on over email. We tried to schedule a call but I didn’t add money to their J-Pay account in time and they couldn’t connect. I emailed them again, through one of the slow, antiquated email systems used by prisons, but didn’t hear back. Then, as happened with many who wrote me, we lost touch.

Ed wrote again. He had to sign up for a computer class in the computer room, which had about ten stations. You get a password, which you can only get if you sign up for the classes, but the room was open all day. There was no internet access. “I usually use the computer to play games for a couple hours a day. Usually but sometimes more if I have spare time.” The main thing he thought about was the game itself, which was important, because it took his mind off everything else. But this feeling of forgetting never lasted long, because it couldn’t. “I do get so focused that I lose myself in the game…I do forget that I am in prison for a short period of time but can’t stay out of focus for too long because of the unpredictable nature of where I’m at (in prison) and what could happen at anytime (violence) around me. No clowns with balloons!”

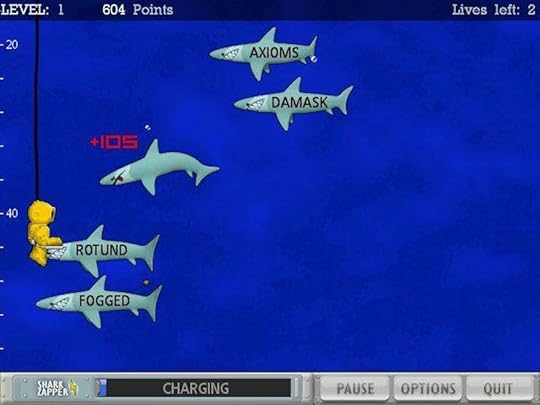

He included a list of some of the games he was allowed to play. “They are educational but so what to a gamer they are just fine.” They were mostly typing games, “Typing with Sharks” and “Tomb Typer” were two. I wrote back to Ed. I told him that his story of retreating into the computer lab had reminded me of when my elementary school computer lab opened, and how, sometimes, to avoid recess, the shame of getting picked last or nearly last in kickball, I would get permission to go to the lab instead. We were only allowed to play educational games, too. Mario Teaches Typing was the one I remembered best. Ed wrote to say that “Every once in a while an old issue of Gamepro will float around and we will all reminisce about the games we used to play. Then recently a new issue of Game Informer came around and we were all ooooohs and aaaahs with drooling in-between.” He thanked me for writing him and wrote that, even though he understood that my grade school experience wasn’t the same, he could see how it was, too. “We’re both escaping something,” he wrote. He wanted me to know that it was important for everyone out there who might read this to realize that even though he was away, and could only play a certain type of sort of dumb game and not the top name titles, he and his friends inside were still trying to find out about them, and looking forward to playing them, and thinking about them all the time. He didn’t want to seem too different, too marked. It was important not to forget that they were, he wrote, “like you, and like all the other gamers who might be reading your story.”

My old roommate, Brian, is my favorite person to talk with about videogames. When we lived together, he was getting his PhD in philosophy and studying riots, specifically the movements and shows of force among riot police. We didn’t play games much together—our apartment was too small, and we were too frugal, to have any system of our own—but no one else I knew was more fun about intellectualizing, say, the police AI movements and mannerisms in Grand Theft Auto. I remember this conversation in particular, because we meandered into what it meant for a society when it saw its police force routinely wielding big, brutal weapons, like assault rifles. Sure it was preventative, but at what cost?

I told Brian then about my experience living in New Delhi, India, where armed guards with automatic weapons were everywhere. I told him about my first day on the job, when one of my new coworkers slipped me his number and told me if ever I had any dealings with the police or military or anyone in power to call him, please, first, because no one in those positions could be trusted, and the feeling of heightened awareness, the edge I was forced to take on, an exhausting edge, living within such a society. When I finished, Brian—who is black—paused a moment, then said, “You realize you’ve just described what it’s like to be me, here, everyday?”

Sometimes the only thing that keeps me sane is the moments I get to think about anything else

Solitary confinement never went away. The slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain were not relegated to solitary anyway, but the entire incarceration apparatus, or something larger still, that lasts longer than incarceration and affects those outside the system, too—a whole race, even. By the 1970s, at the outset of our strange and modern era of imprisonment on a massive scale, the U.S. abandoned all its Quaker-inspired notions of rehabilitation and began to slash funding for in-prison education programs. Inmates were always meant to suffer, but now the suffering was outright. Suffering was the point. Activities that pulled a prisoner away from the experience of being in prison—a class, a game—were deemed particularly troublesome. Culturally, we’ve adopted this stance, too. The typical news story about videogames in prison most often mentions the irony or outrage of criminals filling their days with first person shooters. Any ex-con who had access to a real gaming system will tell you, as several told me, that the games with the most bang for your buck inside are not shooters but either sports games (because other inmates will pay to play them, too) or incredibly long and complex role-playing games. Shooters are usually too fast, too simple.

Malcolm, who was on a 355-month federal sentence for firearms and drug trafficking, wrote me. He wanted to tell me about his son. Videogames are what he and his son talk about, when they talk on the phone, which is as often as possible but not very often. He’s been gone four years now. He had an Xbox 360 in his car and he and his son used to play in there together. He can’t play games in federal, no, but it’s impossible not to think about, because it’s impossible not to think about his son. “Of course,” he wrote, “there is a bad part of prison life that is in some ways like a game.”

“Prison socializes an inmate to behave hyper-rationally,” begins Marek Kaminski’s Games Prisoners Play. Kaminski was a twenty-two-year-old Polish sociology student, arrested for running an underground, anti-communist publishing house in 1985. For three years he observed prison from the inside, making note not just of the endless violence but the events preceding and following a fight or a rape. He wrote his master’s thesis about the experience, which then became the book. Prison, Kaminski observed, rewards generously for smart action, and punishes severely for mistakes. There is constant feedback. The rules are different from real life. What might at first appear chaotic and lawless from the outside is in fact governed by its own internal, and in a sense, hyper-rational, rules. In this way prison is like an almost endless, exhausting game. To be a prisoner you have to become someone else, endlessly present to the moment, because every moment carries within it the possibility of turning deadly. No wonder, given the choice, an inmate would rather be in his cell, playing a videogame. One inmate, in a message conveyed to me in an email sent by his Write-A-Prisoner pen-pal, said that “sometimes the only thing that keeps me sane is the moments I get to think about anything else.”

Brendan Jay got out just a few years ago, after eight years in. He’s still on parole, and will be for about another decade, all for robbing some drug dealers who’d robbed his friend. “It basically cost me 20 years of my life,” he told me over the phone. There was still, he said, this “huge gap of not really relating to people, still having the same kind of anxiety and trepidation and hyper vigilance when I’m just, like, sitting around people.” Videogames have been an outlet and an escape. He’d found a group of friends online and they always play together—Halo, mostly. Gaming with the group allowed him to socialize while doing something active. It occupied his mind. “I would say that I spent too long in a place where everything is so intense and stressful and extreme that sometimes, when I’m just sitting around, it feels surreal, like, this can’t be life. I get anxiety from sheer boredom. Anxiety from not having anxiety. But when I’m gaming, it’s intense, it requires constant strategizing, it’s a way to distract and almost trick my mind out of the anxiety of regular life.”

At first I didn’t want to deal with the moral question. The moral question being: should videogames be in prison? When videogames and prison enter the media, most often, they are handled bluntly, dumbly, morally, like: can-you-believe-it? It’s a kind of trap to fall into. But, I’d learned, it’s impossible to avoid, because it’s the whole thing. Few inmates have access to videogames, and beyond videogames, the few means of distraction from his current incarceration an inmate is allowed are entirely moral choices others have decided for him. Often these choices defy logic—as moral choices often do. My personal favorite involves not videogames but Dungeons & Dragons. A 2010 decision by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a Wisconsin prison’s ban on the the dice game (as well as the possession of D&D publications and materials) under the rationale that it might stimulate gang activity, though there was no evidence to prove it did. In fact, the only evidence seemed to be indulging in escapism, becoming divorced from reality, and, in one case, from out of state and not even involving inmates or gang members, two D&D players acted out a D&D storyline and, in doing so, committed a crime.

At trial, a specialist testified that cooperative games can mimic the organization of gangs. And that, in fact, because one player in D&D is denoted the “Dungeon Master” and can give directions to other players, this mimics the organization of a gang.

Gaming with the group allowed him to socialize while doing something active

The worst thing about corresponding with prisoners over the course of many months is how easy it is to lose people. Maybe they run out of money or are moved or just don’t have time, but the number of half-formed conversations and dropped thoughts and missed moments would fill a whole other essay. It’s hard to be in touch with people in prison, and that is the point. It’s supposed to be hard because we have created a system that makes it easy for them to be forgotten.

The most dangerous aspect of an inmate playing videogames in prison, why inmates think and dream about playing, is so that they might forget, too, if only for a moment, the extraordinarily awful circumstances that surround them. It’s not as simple as an escape. It’s a return to something approaching life.

Is that okay? That they for a moment forget where they are? Or who they are? That they be, for a moment, not an inmate, not a number or a race or class or sexuality but simply someone playing?

Brendan Jay told me how much he’d wished he had videogames when he was inside. He said, “I don’t know why they don’t, it would be so helpful. To cope. To maybe feel not normal but not, there.” Then he described how often someone would come up to him, wanting to start something, slap him in the face, talk about his mom. “I just wished, in that moment, I could go back into my room and play Halo. Can you even imagine?” he said. “Can you?”

In 1920, the Times returned upstate to cover baseball in prison, this time to Comstock, New York, to a game pitting the prison team against a company team, from the Union Bag Company. The reporter noted something remarkable, watching the inmates walk out to play. “To an outsider there was nothing to indicate that the men thus crossing the field were prison inmates. They wore no uniforms as such. The trousers of each man were gray. Apart from that there was nothing to show they were members of a correctional institution.”

How female modders are bringing better diversity to videogames

For as long as we’ve had games, we’ve had mods. They’re an integral and maybe necessary part of gaming, used either to personalize an experience or simply as a creative outlet. As a South Asian, I’ve banked on mods to make characters that actually look like me and not a version of myself that looks like, you know, I jumped in a tub of baby powder. So I’m grateful for mods and big-name games like The Sims (2000) that have actively encouraged modders to further customize player worlds as they see fit, even going as far as to advertise popular mods on their website.

The female modding community in particular has found modding to be an effective way to turn drab, colorless game universes into spaces of their own. Testament to this, The Creative Project recently interviewed modder girlplaysgame, who runs a popular modding website eponymously named Girl Plays Game. In the interview, girlplaysgame noted that, on one hand, very few modders are, at least consciously, using mods to make big-time social impacts. Though she has no interest in “feminizing” games, she mentioned the importance of modding, or literally creating, a more inclusive gaming culture. For her, modding is the spice of gaming, and without the ability to mod or at least have diverse customization options, some people will feel excluded from an immersive experience, while some people just want to make their characters wear hipster glasses.

a tool for fighting ingrained sexism

On the other hand, modding is about more than just the visual ability to make Commander Shepard wear a modded tutu for fun while retaining her no-nonsense attitude. Maybe most modders aren’t consciously choosing to make social impacts. But modding can, in the right hands, become both a tool for fighting ingrained sexism in the gaming industry, and a method of agency for marginalized voices who would otherwise never see themselves in games.

For example, modding vigilantes have many times used their skills to point out overtly gendered movements in games like Dragon Age 2 (2011), in which female Hawke, compared to her male counterpart, has a clearly exaggerated hip-sway and daintiness in her walk in a way entirely at odds with her gritty personality. Modding is thus a way for players to gently prod those creating games and kindly point out a sexist practice (and others) in their work that they may have otherwise never noticed.

Don’t get me wrong: I am a huge fan of default Shepard’s gorgeous red mane, bulging biceps, and mini-galaxy of freckles painted on her face. But being able to make her look more like me is a great option to have and one that I readily take up. And until more games have such broad customization options, modding is the only way I can get that type of fulfillment. So, mod on, girlplaysgame. Mod on.

You can read the full interview with girlplaysgame over on The Creative Project.

Images via Girl Plays Games

Football players now use 360-degree video to improve their skills

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

A former NFL kicker is using cutting-edge virtual reality videos to help players and coaches train better, faster, and smarter.

Last year proved to be a banner year for athletics-related technological advances. A slew of smart helmets and wearable devices are now helping athletes, and better player tracking and camera angles are bringing sports fans amazing perspectives on favorite players. While all kinds of sports benefited from many new technologies in 2015, Sports Illustrated named virtual reality the innovation of the year. Looking ahead, 2016 could see virtual reality technology become widely adopted across mainstream sports. Professional football players are already testing it out through new training programs like the one by STRIVR.

A startup was founded in January 2015 by former Stanford University kicker and coach Derek Belch, STRIVR is poised to bring virtual reality videos into football training camps across the country. More accurately, Belch is bringing football training camps into the world of 360-degree videos. “When the player uses the training system, he is in an empty room with enough room to move around a little bit if he wants to simulate his footwork while watching a play,” Belch said. “In VR, the player is able to see the play from the view he actually has on the field and feels completely immersed in the environment.”

Tiny Steelers? by Andy McLemore

A handful of NFL teams and more than a dozen college programs are using STRIVR. With the help of a 360-degree camera, football drills are captured then stitched together so players and coaches can later watch each drill wearing virtual reality headsets. This gives them a 360-degree perspective on every play and every player.

The idea for STRIVR was born from a belief that there had to be a more effective way to study gameplay film than the traditional sideline and end-zone views. “Most teams will tether the [VR output] view to a television or projector so that the coach, or other players in the room, can see exactly what the player is looking at,” Belch said. “In this way, they can quite literally ‘coach’ the player while he is in VR.”

a 360-degree perspective on every play and every player

The example Belch uses involves a quarterback in search of his safety. If he looks for the right safety when he should be tracking down the left one, the coach will be there to correct him. “This is a very significant use-case for VR versus traditional film,” Belch said. Companies like EON Sports VR also bring virtual reality to athletic training using interactive videogame-like play, but Belch’s STRIVR actually films practice in 360-degree, immersive video, allowing players to ‘re-live’ each practice film from inside a virtual reality headset. Players can then study the practice from the same vantage point from which they played.

There is another benefit to using 360-degree video, according to Kim Pallister, director of virtual reality strategy at Intel: accessibility. “The thing you can do with video that you can’t do with the more [interactive] VR stuff is get it to a lot of people,” said Pallister. “360-degree video is already supported on YouTube and Facebook. Plus with Google Cardboard and GearVR shipping, there’s a lot of solutions out there.”

STRIVR uses the higher-end Oculus Rift headset for increased fidelity, but at a basic level, the company is working in a format that a mass audience can experience and understand. That mass audience can come into play when college football programs are recruiting. STRIVR shoots 360-degree videos in meeting rooms and huddles for schools including Arkansas University. These videos are designed to offer perspective players a taste of what it’s like to be part of the team.

Pallister said this implementation of VR is “more of a kitschy sort of experience,” but has a place in the competitive collegiate sports environment. “There’s money on the line,” Pallister explained. ”Teams often have a relatively high budget tolerance for things they believe will help them win games. They’ll look at any new technology and figure out what makes sense.” And with three STRIVR-using teams (Stanford, Clemson and Dartmouth) winning conference championships this year, Belch sees great momentum growing behind his technology.

While STRIVR and other virtual reality startups aren’t interested in entirely replacing real-world experiences or on-field practice, the technology is showing great promise beyond daily drills. It’s bringing current and future players, coaches and fans deeper into the game of football.

DJ transforms Sonic The Hedgehog sounds into house music

Tony Donson thinks he’s the first person to use the Yamaha YM2612 to create original music. It’s the sound chip found in the Sega Genesis (or Mega Drive) from back in the early ’90s, and so when it is used, it’s typically to create fan versions of songs with the Genesis sound or to remix classic Sega songs. Donson uses the sound chip to create house music that beams with the lo-fi tropical sounds of Sonic The Hedgehog (1991), as can be heard in his debut EP “Secret Island,” and he does it all under the telling moniker DJ Sonikku.

Speaking to FACT Magazine, Donson says that his introduction to music was through Streets of Rage‘s (1991) sound test menu on the Genesis, where he was able to listen to each stage’s soundtrack. This, he says, is where he learned what house and techno were before even knowing the words for their respective genre. The sound of the Genesis would stay with Donson for years as his family couldn’t afford a PlayStation One, meaning that he was playing the 16-bit console up to around 2000. He is hardwired into its iconic music. Be it no surprise, then, that one of Donlan’s biggest loves is Sonic The Hedgehog, which he still plays a lot today for its breezy, retro charm. “Obviously the music to the Sonic games is something that’s guaranteed to be good,” he adds.

Donson turned this love into his 3-track EP “Secret Island” which he says is modeled after an imagined island in the Sonic universe. Donson reasons that his fascination with the Sonic games is their nostalgic tones that are delivered with a notably pleasant air of innocence. The floating islands across the games are core to this aesthetic, being places untouched by humans, a paradise for the animals that live there. “The music reflects what it would feel like to discover that island for yourself,” Donson says about his EP. And key to achieving this feeling is tapping into the sounds of the Genesis’ sound chip.

“You can also make really nice smooth, jingly sounds”

Those years of listening to the Yamaha YM2612 at work has given Donson a deep intuition for how to get the most out of it when creating his own tunes. “I really like how gritty it can sound and metallic,” he told FACT Magazine. “You can also make really nice smooth, jingly sounds with it which is amazing.” He also claims that the chip has a “really amazing drum pack.” His understanding of the chip goes much further as he demonstrates when describing how he drags a sound into the sound frame so that it decodes—from this, he gets an individual instrument that he can manually tweak as he wishes, rather than settling with using pre-existing samples. “If I like the bassline on Green Hill Zone, I can put that in there and it gets the instrument for me and I can use that to make my own pattern out of it,” Donson says.

He’s one of a few musicians who has been raised on videogames to the point that it only feels natural to incorporate their hardware directly into their creative process. Another is Yamaneko, who focuses on using PSOne sounds and the console’s Final Fantasy games as a focal point, and who Donson feels a connection with. Next up, Donson says he has two more EPs on the way one is an extension of “Secret Island” while the other is darker, coming from a dystopian version of the island.

You can listen to and purchase Secret Island on Lobster Theremin.

h/t FACT Magazine

Layers of Fear can’t transform the tortured artist trope

On January 2nd, George R.R. Martin came clean with his readers about his progress on the sixth book of A Song of Ice and Fire (1996-present): Winds of Winter would not be published before season 6 of Game of Thrones (2011-present) goes to air on HBO. Readers could choose not to watch the show as it is released, but as any basically sociable person with a stable Internet connection knows, dodging Game of Thrones spoilers is a hopeless occupation. Martin explained his disappointment in a long post on his blog with an apology that laid bare some of his anxieties about the creative process, namely that he has little control over the timing of his breakthroughs. Frustrated fans aren’t wrong to feel that this is a cop out, but writers of all stripes can sympathize with his predicament. As Martin puts it most succinctly in his blog, “Sometimes the writing goes well and sometimes it doesn’t.”

Thankfully, Martin has the good sense not to comport himself like God’s wide receiver when it comes to churning out his work. No real writer has time to sit around waiting for inspiration to hit them out of the clear blue sky, and all the good ones have their own processes for getting the job done. While alive, John Updike used to force himself to write 1500 words a day—no excuses. Jonathan Franzen once glued a severed Ethernet cable into his office’s telephone jack so that he wouldn’t have the Internet to distract him while working. Inspiration itself isn’t a myth, but as just about any professional artist will tell you, the surest way to come upon it is to wrestle it out through diligent work.

It’s in the throes of this creative turmoil that Layers of Fear begins with its protagonist. He is a painter (his name withheld throughout the game) who met with some acclaim earlier in life and is now killing himself to complete his masterpiece. As you might expect from a game touted as psychological horror, things are not going well so far.

As the game begins, you stagger over the threshold of your impressive Victorian home, coming in late out of a wet, gloomy night. You’re presumably drunk—you soon discover that drinking is about the only thing the protagonist does consistently well these days—and your vision bobs and sways with your body as you look around. The house is fairly neat and furnished handsomely. It’s dimly lit, but little is amiss as you initially explore, finding notes and scraps that begin to ground your fuzzy, drunken mind back in the real world.

YOUR VISION BOBS AND SWAYS WITH YOUR BODY AS YOU LOOK AROUND

The walls of the stairway are hung with paintings almost to excess, but then, as you head up to the second floor, you realize that they comprise a kind of anthology for the painter’s morbid tastes. Most of the works have an unsettling undercurrent, if they’re not openly creepy. Francisco Goya’s Portrait of Tio Paquete (ca. 1820) peers oppressively over your shoulder as you turn the corner on the landing, and Rembrandt’s Stormy Landscape (ca. 1638) rumbles overhead. This trend continues throughout the game with each work reflecting some aspect of the protagonist’s inner life, whether it’s a fascination with violence, old world gentility, the pain of loss, or just plain moodiness.

Before you begin trying to navigate the endless labyrinth of halls and rooms that make up this haunted house, you’re given a quick glimpse of the protagonist’s own art. The studio itself is a spare room, dominated by a large easel near the center. A few trunks are stationed by the walls, some filled with the bottles of liquor that fuel the painter’s manic midnight vigils. The trail of notes you follow to his studio begin to show just how withdrawn the protagonist has become. He stays up most nights, working without eating or sleeping for days at a time, without any regard for the wellbeing of his family.

In short, this guy is a classic Tortured Artist, a caricature about as subtle as a Banksy stencil at Disneyland. He’s neurotic, self-obsessed, misogynistic, and thoroughly convinced of his own superiority. And most annoying of all, this guy is an absolute zeppelin of hot air. He has almost nothing interesting to say, and the ultimate object of his obsession (to say nothing of the grotesque way he intends to satisfy it) is painfully shallow.

However, after two playthroughs, I still wonder what exactly Bloober Team intended to say with this character. On the one hand, they could be delivering a send up of the tortured artist trope—a welcome one, because characters with this magnitude of self-seriousness desperately need to be taken down a peg. This painter seems loathsome by design, and his self-imposed isolation is almost cast as a dangerous withdrawal from family and society. On the other hand, the painter is the character with whom you are asked to identify most directly. For all his craziness, the game wants you to admire his ambition and dedication to his craft, to feel sorry for his loss, and to understand how he found himself on his path to madness. But that is a step I can’t take. In the end, he’s just a hateful, selfish jerk.

You spend the entire game stumbling in this artist’s shoes, searching through room after room for information about the house and the small cast of characters that occupies it. The trick of it is, after seeing the whole layout of the house in the prologue, you’re never comforted with that stability again. Old rooms and new ones present themselves on the other side of each successive door with no consistent logic. You’re completely at the whim of whatever forces—supernatural, psychological, or otherwise—are designing this harrowing journey through your own home.

YOU SPEND THE ENTIRE GAME STUMBLING IN THIS ARTIST’S SHOES

As an attempt at defamiliarizing this familiar domestic space, walking through the game feels like a series of exercises in recreating the chill of P.T.’s (2014) single hallway. On the whole, they’re executed with some modest success. The manipulation of environment is most effective when it is most cerebral, as when you look up to see that the walls of your office extend to dizzying heights, or when a basement room full of discarded furniture is suddenly relieved of gravity.

Moments like these make Layers of Fear worth playing. Yet as beautifully disorienting as the game can be, it ultimately has little interesting to say about artists and less to say about art. Stomaching the jump scares and heavily recycled horror imagery will earn you a handful of mesmerizing vistas, but Layers of Fear fails to challenge or transform its central trope.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

March 1, 2016

Computational artist creates a nightmare of writhing bodies

A mass of speedo-clad elastic men floating in space—just human enough to be unsettling. They don’t move of their own volition but, rather, succumb to the physics of zero gravity, writhing and contorting around each other. It’s as as if an astronaut has sneaked her childhood collection of Stretch Armstrongs onto the International Space Station. This is the bizarre reality presented by computational artist Albert Omoss in his most recent short, Undercurrents.

According to his website, “Omoss’ art practice relates the axiomatic structures of reality to the anthropocentric ideals of technological innovation,” which could perhaps be translated to mean that his work is an interrogation of humanity’s place in the universe. It poses the question that if reality is already fully established separate from our own society, can we ever really import our own will onto it, even with all of our technological advances? Ironically enough, Omoss does this through the use of code, first writing software simulating “intricate systems” and then using that software to create visual art, not unlike Jaume Sanchez Elias, the man behind confetti-simulator Polygon Shredder. In fact, my first thought upon seeing Undercurrents was “This is like Polygon Shredder, but with naked dudes.”

like a XXX parody of Castlevania’s Granfalloon

Undercurrents is actually the latest in a trend across Omoss’ work, which has slowly transformed from bright and cheery ads for companies like Keebler and Google to videos about masses of bendy people contorting together into new and surreal shapes. Forms, for instance, uses a dozen or so leatherclad men to create a worm, as if the Cirque de Soleil decided to interpret an episode of Voltron. Entangle features a more intimate experience, focusing on a man and a woman as she slowly wraps her body around him like a boa constrictor and dips her hand into his heart. Plug Party is about a man helplessly falling through the pegs of a pachinko machine. Of these works, Entangle seems to give its characters the most intention, while Plug Party and Undercurrents instead render the human body as the plaything of the reality around it.

Each of these shorts is set to bleak, melancholy soundscapes that instill a sense of growing dread. For me, the music transformed the work entirely, as when I first watched Undercurrents, I viewed it muted while waiting at a subway stop. In this context, it actually looked quite funny to me, like a XXX parody of Castlevania’s Granfalloon (sometimes referred to as Legion) directed by classic Hollywood choreographer Busby Berkeley.

But that in itself is not entirely at odds with Omoss’ message. Without sound, what I saw was all the presumed power of the male body being quite literally deflated, turned into a noodly collection of feet and chiseled jawlines. Just as the more serious version of Undercurrents I experienced when watching it later with headphones had me considering how insignificant humanity might be in the face of an uncaring universe, my comical first viewing was all about making the intimidating small. As Omoss’ About page explains, “His personal pieces often explore the fragility of the human form.” You can experience this fragility for yourself over on his website.

Experience the difficulty of seeking asylum in a beguiling virtual city

That NORTH is about the current climate surrounding mass immigration is about as obvious as a sledgehammer to the face. It’s coated in 80s synth-pop sci-fi as if to cover it up but there’s no denying it. You are a person in an overwhelmingly foreign city. You must learn the customs of this new culture. You have traveled from the south, escaping its lakes of fires, crossing a harsh desert, and arrived here where you hope it’ll be safe. Subtle this game’s allegory is not.

Mind you, the creators at Outlands (who also made the politically-charged Dämmerung) aren’t necessarily trying to shroud their efforts, considering they’re openly donating half of all the money NORTH makes to Refugees On Rails and Refugee Open Ware. Perhaps they can be forgiven. What Outlands specifically swivels its lens upon with NORTH is the scary process of learning, growing accustom to, and being officially accepted by another society.

NORTH wants you to feel utterly lost in this place

This is realized through the architecture of the game’s virtual city, which seems to grow endlessly upwards in concrete around you, and by the lighting that gives it all an unwelcome dinginess. In fact, the look of NORTH takes directly from the set designs of German Expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), borrowing the large slanted silhouettes of windows and sharp, oblique slopes that run through the city. The result is a three-tiered mass of towers and alleyways that unsettle you at first before you work out how to navigate it all.

Beyond that, NORTH seems to fail and succeed simultaneously. You are tasked with applying for asylum in this city—you know this as your character writes a letter to his sister at the beginning—but the granular details of achieving this are left for you to figure out. NORTH wants you to feel utterly lost in this place. This is why there are strange creatures in your apartment, why your workplace demands you adhere to a peculiar ritual, and why the people in this city worship surveillance as a god (a commentary on contemporary western norms). Nothing makes sense here. The idea seems to be for you to feel as any real asylum seeker does when they first arrive at their destination. And in doing this it could be said that the game is successful.

However, in trying so deliberately to alienate, NORTH risks losing you altogether. There is a hint system but it isn’t immediately available: you have to experience being stuck in a place first before you can write a letter to your sister that explains what you’re supposed to do. And the mini-games that you have to complete aren’t explained at all and don’t have the benefit of being obvious enough for them to be immediately worked out either. Everything is obfuscated so much that you’ll probably give up playing the game after only 10 minutes. But maybe that’s the point.

Given that NORTH is clearly meant to confuse, it might be that Outlands intended for many of the game’s players to not make it all the way through, to get stuck and to give up. This would mean that these players’ efforts to be granted asylum would have failed. In such a case, perhaps Outlands means to make a parallel between the players and actual asylum seekers, sending the message that the many legal and cultural transactions that refugees go through are too difficult and unreasonable. That may be giving Outlands too much credit for what is actually a failure. But it’s a reading of the game that certainly exists no matter how it came to be.

You can download NORTH over on itch.io.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers