Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 151

March 10, 2016

Everything, an open-universe game about the nature of being

Everything is coming exclusively to PlayStation 4 in the near-ish future. Er, that is, Everything, the next game by David O’Reilly. Not, you know, everything. It’s a simple idea with a huge scope: you can embody and play as everything that you see in the game’s universe. Damien DiFede, the game’s programmer, has had to come up with a new way to create and design levels to accommodate this ambition, treating objects more like ecosystems. When O’Reilly says “you [can] be anything you want” he means it.

While this promise of being able to become anything does seem to be a one-upmanship of No Man’s Sky‘s enormous procedurally generated universe, there’s a big divide in the two games’ roots. No Man’s Sky is largely a mathematical feat about conquering planets, plants, and creatures by discovering and recording them; it’s an imperialist’s wet dream. But Everything is almost the opposite of that. You don’t hold power over your findings by categorizing them, instead you enter their bodies, see through their eyes. “If you ever wanted to see what it’s like to be a horse, or a paperclip, or the sun, this is for you,” O’Reilly says. “Your main power in the game is Being (there are more but I won’t ruin the surprise).”

“people have been arguing about what things are since the dawn of time”

Everything might seem like it’s trying to be the ultimate empathy game, but this doesn’t encompass its entire pursuit. It is more rooted in an ontological interest. O’Reilly wants to explore the nature of being and how it is that we understand and talk about things in the universe. “It sounds obvious, but people have been arguing about what things are since the dawn of time,” he says. It’s a line of thought that branches out from Descartes’s famous notion: “I think, therefore I am.” Having consciousness is enough to confirm our own existence. If so, then perhaps transferring that consciousness to flowers, peacocks, or an entire nebula can help to prove their existence too. This is what Everything is all about.

O’Reilly sees Everything as a continuation of the themes he explored in Mountain (2014), in which you were encouraged to regularly check up on the titular landmass as it floated in space. Notably, this mountain was shaped around questions you answered at the start of the game, lending it a personality. Over time, large objects wedged themselves into your mountain and you would learn that you could please it by playing songs on the touchscreen. All this led towards you beginning to care for this mountain as if it were a person. Mountain had us question our understanding of what a rock is, or what it could be. Everything looks to expand that to, well, everything else.

Keep track of Everything by visiting its website.

The desolate mansion of Resident Evil

Resident Evil, released in 1996 for PlayStation 1, is hilarious—it’s so funny. The voice acting is ridiculous, the plot is sensational and the live-action cutscenes look like they’ve come from a porn parody film. In fact, that’s Resident Evil in a nutshell: from the campy character and costume design through the cheap music and sound effects, Resident Evil feels like a high-end fuck film, only without any fucking. Look at Jill. Look at Chris. Look at BARRY. This is a cast of actors straight out of a Brock Landers movie. Resident Evil has become the beloved low watermark of videogame production value, but designers Shinji Mikami and Hideki Kamiya, and the rest of the team must have known what they were doing. Surely this game was never meant to be a straight-faced horror. Surely, to play Resident Evil is to fall for its honest, vivacious charm.

Resident Evil is sexy and fun. But the Resident Evil Remake, released six years later, is dull and dry. The difference may be based in a simple mistake. It’s still a game about zombies, monsters, and an elite group of cops called S.T.A.R.S., but so much of Remake is rooted in—not timidity exactly, because the original game was overhauled a great deal—but self-consciousness. It feels to me like a renege on Resident Evil, like instead of rolling with the original and all that made it wonderful, the game’s designers have grown embarrassed. It feels like an unnecessary apology.

The second floor of the dining room in Remake is a wonderful visual flourish—the lightning crackling outside, casting the shadow of a lone zombie large on an opposite wall is one of the finest single images Capcom has created. But other than that, the GameCube (and, later, the PS4’s) better hardware, while making for a more detailed mansion, leads Resident Evil in a boring direction. The original was colorful, blocky, striking. Remake is dim and dark. To some extent, it’s stifled by player experience—that main mansion hall, once you’ve explored it time over in the original Resident Evil, is never going to hit you the same way again, even recreated in a brand new engine.

The tone might not be as sophisticated, but it is consistent

But the new areas built for Remake, the additions to the mansion, are all bland and perfunctory. Apart from the nodding twists on old puzzles, I don’t remember, really, any of the new areas added to Remake. They’re just uneventful rooms, more area. That dark corridor behind the kitchen does nothing—it’s not scary, it’s not visually interesting, nothing happens there. That’s why, I think, the designers tried to punch it up by chucking in a few giant spiders and a puzzle with a fuse box and some water, but it’s halfhearted. Lisa Trevor’s cabin in the woods is a flat detour, again containing some arbitrary flashes (a graveyard and a puzzle with a weather vane) and that half hour long section, about two thirds into the game, where you go under the mansion and into the catacombs, traversing some caves and solving some lever puzzles, is drab and slow. There’s nothing aesthetically vibrant about brown cave walls. Compared to Resident Evil’s usual, weird puzzles, throwing levers feels pedestrian.

The original Resident Evil is much leaner and almost every room gives you something, be it an enemy encounter, a puzzle piece or some memorable visual flair—from the tiger statue closet to the dog corridor and the bar with the piano puzzle, you can refer to basically every area in Resident Evil by something that happens. Remake on the other hand wastes a lot of space. It has more booby-traps and monsters, but the mansion in Remake—and I mean this in the pejorative sense—feels more real. I’ve written before that Resident Evil 2’s (1998) police station is at its best when it drops the facade of a real municipal building, and leans more towards fantasy architecture and decor. The same can be said of the two versions of the mansion featured in Resident Evil and Remake. The original doesn’t make as much sense as a building and lacks the lustrous detail, but that makes it appropriately otherwordly.

I was talking with a friend recently who claimed the original Resident Evil is “over lit and lifeless.” I don’t disagree. But the mood set by Resident Evil’s over lighting, as opposed to Remake’s under lighting, is more spirited. Remake is supposed to be oppressive and an ordeal, but you’re playing as cops, with lots of guns, who are introduced in a smoothly produced, spectacular cutscene. The game’s lit in spite of the characters. These guys are trained soldiers—it has the blackened visuals, but I don’t buy Remake’s world as cruel. By contrast, the eager, action-heavy opener of the original Resident Evil, which ends with the characters tooling up and bracing for a scrap, looking straight into camera, feels absolutely right given the brightness and expanse of the mansion. These guys want to get into it. They want to know what’s going on. They’re as sparkling and fizzy as the mansion’s many lightbulbs, unburdened by the kind of introspection and pessimism connoted by darkness. The tone might not be as sophisticated, but it is consistent. Remake is sincerely trying to a serious horror, but its efforts regarding lighting and set feel occasionally token.

A lot of Remake features no music—it’s all silence and diegetic sound. When there is a score, it’s comprised of slower, somber rearrangements of the original Resident Evil soundtrack. That, I think, exemplifies the difference between the two games. Listen to the music from the snake boss battle in Resident Evil. Now listen to the same battle in Remake. The shark tank in Resident Evil. Now the shark tank in Remake. The original is cheaper, but every note is clear, distinctive, ALIVE. It sounds like one of John Carpenter’s scores, peppy synth that’s instantly recognisable and easy to hum. Remake’s soundtrack, by contrast, is mainly vague, orchestral posturing. It sounds more expensive, but it has no flavour. I mean, just listen to this. And now listen to this. One is unmistakable. The other could have come from any game.

Remake is at its driest when it’s dealing with Lisa Trevor, and her whole sub-plot and history. Resident Evil Zero (2002), developed alongside Remake and with the same technology, features as its antagonist a guy in a floral smock who sings hymns in order to command his army of leeches. Lisa Trevor is an altogether sadder, ostensibly more intimidating monster. Through found trinkets and diaries, you discover how she was kidnapped and transformed against her will, and is now wandering the mansion searching for her parents. She has her moments—when you hear her moans from a distance, it puts a rod up your back—but like Remake’s detailed architecture and its more reserved soundtrack, Trevor feels like an effort to ground Resident Evil, to make it—in the sense of Christopher Nolan’s high-end Batman films—grittier and more “real.” Her character isn’t badly handled and it’s unfair to criticise Remake for going more serious. But you look at all the sequels, spin-offs, movies, and novelisations of Resident Evil now, and it seems like a series absolutely drowning in lore and “back story.”

I can’t help but think of the tertiary Lisa Trevor plot line as a progenitor to that—Resident Evil 1’s story was fine, and much more nimble, without it. Sobriety and discipline seem like the creative bywords behind Remake and by that measure it’s a success in its own right. But the original Resident Evil is earnest, and I appreciate earnestness, and an absence of cynicism, above seemliness. To an extent, you can see that earnestness also in Resident Evil—Code: Veronica (2000), a game where, instead of a tortured, mutated girl, the villain is an insane English aristocrat with a penchant for cross-dressing. Deadly Premonition’s (2010) twists and turns always feel like the creators saying “yeah, why not?” Same goes for Driver: San Francisco (2011). Easily, that could have been another straight crime game, but the creators tried adding a science fiction twist and even a little soap opera, and it became something much greater. Resident Evil Remake is a contradiction. It’s a bigger game than its ancestor, made with more money, more detail and more craft. Yet, despite its expanded size and prestige, it feels like a retreat, like a game less confident in effectuation and painting in broad strokes.

March 9, 2016

People are forming orderly queues in The Division, a game about chaos

Military-minded author Tom Clancy has his work adapted into games all the time; his blend of nitty-gritty technical detail and completely absurd US-against-the-world plotlines is perfect for shooters of all kinds. However, despite his dedication to apocalyptic terror scenarios, one thing Clancy never anticipated was … the queues.

Luckily, Ubisoft’s Tom Clancy’s The Division was released yesterday, and it has all the white-knuckle waiting action you can stand. Taking place in a disease-ravaged NYC with absolutely zero parallels to 9/11, The Division taps into the same “but what if society fell APART, man?” paranoia of AMC’s The Walking Dead. It’s a license to be the all-American badass who lays into “looters” with a shotgun, keeps a closet nicely stocked with beanies, and … waits in line to exit the starting area.

“Form a line”

Yes, like families milling about in some sadistic future theme park, it appears players are queuing up in The Division‘s tutorial area because of an amusing oversight: all characters are rendered as bodies in the game world, meaning you can’t just pass through them to talk to the guy behind the desk or open a crate. You have to wait your turn, because no matter how Kafkaesque things have gotten, this is still America, and I swear to God if we start rushing the NPC behind the desk like animals what does this country even mean anymore? If we don’t line up right now, Manhattan is finished.

“Form a line,” says player FrankCastle80 in the screenshot above, standing up tall—the Rick Grimes of bureaucratic bullshit.

Another plaintive cry from the chat: “don’t cut.” Two words never felt so heavy.

@SuperBlueBadger "don't cut" – random Division player #27 pic.twitter.com/oczZWBKpyc

— Badger @ His PC (@SuperBlueBadger) March 8, 2016

And then there’s this gem:

Now this is all in good fun, of course. I wouldn’t be surprised if all this gets patched out of the game immediately. It’s a little curious, though, that in a game about a hostile, devastated NYC, you have enough trigger-happy “agents” lined up to combat The Chaos strangling the city. It’s like those if pricks that waltzed around Ferguson, MO with assault rifles collided with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: sheer apocalypse tourism tapping into a rich vein of xenophobia and fearmongering.

Line up, you brutes, and play nice.

1979 Revolution to explore the Black Friday Massacre this April

1979 Revolution, the adventure game series based on political events in Iran that year, will see its first episode released on April 5th. It’s something I’ve been waiting for since playing a demo of the game on an iPad at an exhibition titled “Sensory Stories: An Exhibition of New Narrative Experiences” at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image in July last year. I had primarily attended the event for the short films the Museum was showing on Oculus Rift, but it was 1979 Revolution that impressed me the most.

The demo I played followed fictional photojournalist Reza Shirazi as he covered the real-world Iranian revolution that led to the overthrow of the country’s monarchy, which replaced it with a new Islamic government led by Ayatollah Komeni. As Reza, I took photos of a crowd of protesters gathering in a city square as the situation escalated in an increasingly violent direction. The demo took place in the afternoon before the Black Friday massacre in 1978, in which armed troops fired into a group of civilians, killing dozens of protesters. That horrific event will be encountered in this first episode of the game series with subsequent ones going on to explore the rest of the revolution.

As its place in that exhibition divulged, 1979 Revolution is intended to expand the types of stories that games can tell. In an interview with our own Jess Joho last fall, the game’s director, Navid Khonsari, told her “In terms of content in videogames, for us, we feel like we’re creating our own little revolution.” He explained that while “games have broadened their design and audiences,” he thinks that “in terms of embracing the real world and real events, we’re only at the tip of the iceberg.”

a game about the difficulty of reporting events like this

Hence, for 1979 Revolution, Khonsari and the rest of the team at iNK Stories have combined historical assets, documentary content, and graphic novel elements. The idea is to provide an “authentic, historically accurate” recreation of the events leading up to and surrounding the revolution. Within this, you have to try to unearth the various stories that arise from different groups of people. It is, more than anything, a game about the difficulty of reporting events like this, especially in the Middle East.

Someone who can speak to that difficulty is Al Jazeera America’s Dorothy Parvaz, who like Khonsari, moved away from her original home of Iran when she was 10 years old, only two years after the revolution. Since then, she’s gone on to cover a number of wars and local conflicts, but eventually found herself captured by local rebels while covering protests in Syria in 2011. Her capture was part of an effort to control the story that she would tell through her reporting. Funnily enough, there’s a scene in which 1979 Revolution‘s photojournalist gets captured and interrogated. Through him, we, too, will have to face weighing up how we cover the revolution against protecting ourselves, just as Parvaz did.

Animated Van Gogh film is made entirely with paintings

Vincent van Gogh occupies a special place in the Western psyche. His legacy mythologized the idea of the tragic artist who nevertheless makes beautiful art. The Starry Night (1889) is so iconic the painting was used to symbolize Cory and Topanga’s fraught relationship at the height of Boy Meets World’s popularity. It’s not surprising, then, that Van Gogh’s life is the subject of a new animated biopic called Loving Vincent.

When Variety reviewed 1956’s Lust for Life, based on a novel by Irving Stone and starring Kurt Douglass as van Gogh, it called the film “a slow-moving picture whose only action is in the dialog itself.” The screen adaptation was considered faithful but flat, and colorless by many, seemingly the opposite of van Gogh’s dazzling work and conflicted life.

the film uses thousands of paintings in the style of Van Gogh

Loving Vincent takes an altogether different approach. Directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman commissioned an army of over 100 painters to tell the story of van Gogh’s life based on hundreds of his personal letters. Running at 12 frames per second, the film uses thousands of paintings in the style of Van Gogh to create a space around the artist’s life and monumental works that can be explored visually.

It’s an unusual approach that seems well suited to the unique flow and texture of Van Gogh’s paintings. While Bedroom in Arles (1888) might make for the perfect movie set, it fails to capture the dynamic brush strokes and movement of something like Road with Cypress and Star (1890). The same eccentric style and kinetic interplay of colors that make Van Gogh’s work so beloved and accessible are also what make it so uniquely untranslatable into other media. Rather than re-imagine his work, Loving Vincent serves instead to extend it.

The art critic Arthur Danto considered Van Gogh, along with Paul Gauguin, to be one of the first truly modern painters. In After the End of Art (1997), Danto wrote that modernism was “marked by an ascent to a new level of consciousness.” Instead of focusing purely on representing their subjects, Van Gogh and those who proceeded him were more concerned with the “means and methods of representation.”

Loving Vincent gives this theory a sort of visual clarity by helping to bring Van Gogh’s idiosyncratic style to the forefront. What slowly becomes clear while flipping through a book of prints takes on a new immediacy when the artist’s work is fleshed out into a continuous whole: the thick, gloppiness of the paint, the swirling nature of its contours, the menacing instability of the compositions.

In Van Gogh’s work, ego supersedes the subject by relying on a level of conspicuous artifice that would have offended painters from generations prior. No doubt it’s a significant part of the appeal. Café Terrace at Night (1888) just wouldn’t be the same if the bright yellows and deep blues of its city life weren’t juxtaposed with our knowledge that the man who painted them also chopped his ear off and later killed himself.

Loving Vincent is currently being shepherded to completion by Breakthru Films, the studio founded by Welchman, previously a producer on the Oscar winning animation short Peter and the Wolf (2006). You can find ongoing updates on the project at its Kickstarter page.

The videogames preparing us for space

“There is only one essential question: What’s the next thing that could kill me? Focusing on that thing, whatever it is, is how you stay alive.” Ground Control, this is Commander Chris Hadfield describing his experiences as an astronaut and career as a pilot for the Canadian Forces, North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School (TPS) and U.S. Navy. To get the full story, just read An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth (2013). It’s incredible.

In order to successfully complete three space missions, two space walks, and live aboard the International Space Station (ISS) for six months, Hadfield had to train extensively for years in Earth-based simulations that gradually prepared him for the thrills and perils of space exploration. As with any astronaut, he had to spend a lot of time in virtual realities, working with realistic simulations that imitate the challenges that might be faced in space. Yes, he had to play videogames.

Chris Hadfield after landing by jasbond007

In order to understand anything at all of the universe, the journey must begin by creating simulations right here on Earth that are informed by scientific research. In the meantime, space exploration is becoming more accessible to all of humanity as futuristic companies like Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are paving the way for civilian access to space. There is a whole orbiting infrastructure of space hotels, asteroid mining initiatives, and 3D-printing in space that is being developed, and it is inevitable that virtual simulations will be needed in order to launch this Earthling dream as a reality.

Hadfield spoke to the importance of astronaut simulations in a Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross once. “It’s not like astronauts are braver than other people; we’re just meticulously prepared,” he said. “We dissect what it is that’s going to scare us, and what it is that is a threat to us and then we practice over and over again so that the natural irrational fear is neutralized.” In other words, it takes years on Earth to prepare for a single space mission. There is so much to learn. Hadfield spent about 50 whole days practicing procedures in the world’s largest pool at the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory before his very first space walk. This gargantuan simulation consists of a large pool that is 200 feet long and 40 feet deep, containing 6.2 million gallons of water, where space station replicas are housed so that astronauts and astronaut candidates can get a sense of working in weightlessness while grounded on Earth.

it takes years on Earth to prepare for a single space mission

Hadfield also describes playing with part-task-trainers or PTTs that are run by a simulation instructor, learning to prioritize tasks as various systems in a simulated mission begin to fail. According to Hadfield, the most complex moments of a mission are during launch and deorbit burn. “We spend our days studying and simulating experiences we may never actually have. It’s all pretend, really, but we are learning. And that, I think, is the point: learning.”

It’s almost like a situation out of Ender’s Game (2013)—riding that blurred line between virtual simulations and true reality, not knowing which simulation or experience might actually end up saving lives during a mission. This is why there are also contingency sims or death sims that force the astronauts and everybody on Earth responsible for the mission—administrators, doctors, NASA media relations, the astronaut’s colleagues and family—to work through the sordid details of a death or fatal injury onboard the ISS or in orbit in a very practical manner. It is always important to prepare for the worst-case scenario. There is even an unusual power in negative-thinking according to Hadfield, gaining the ability to quickly and efficiently anticipate all the ways that a mission could possibly fail. This means preparing for just about anything, enabling each astronaut with the confidence to make quick judgement calls whenever it matters most.

Hadfield, too, speaks to the importance of failure in sims in his book. “Sometimes a sim is a proving ground where you demonstrate how well-rounded your capabilities are,” he says, “but more often, it’s a crucible where you identify gaps in your knowledge and encounter domino effects that simply never occurred to you before.” This is where true creativity is needed—thinking up all kinds of systems failures and actually recreating these ideas as effective simulations. We, as a species, have no problem with this particular task. After all, this is what’s already happening on a large-scale as all of humanity anticipates future Mars missions. Look at The Martian (2011), a bestselling novel turned award-winning sci-fi film that captivated audiences with Mark Watney’s ingenuity in surviving the tough Martian climate. Both the book and the film draw upon real scientific knowledge of Mars, as well as an understanding of current technologies being developed for future missions in order to create an imagined yet realistic simulation of a Mars mission.

It is this type of originality that will be needed in creating simulated scenarios for future deep space missions. Maybe future NASA job announcements will read somewhat differently than in the past as game makers are moved into high demand within scientific fields, bringing space exploration to life with virtual reality possibilities. In fact, NASA has already teamed up with Microsoft to create the Microsoft HoloLens, a virtual reality tool that gathers real Mars data from the Curiosity rover and then creates a 3D simulation of Martian terrain. It’s part of a line that’s being drawn towards the value of videogames that can both accurately simulate space exploration missions and reach a wide audience.

NASA is already trying to excite and educate

It should be unsurprising, then, to find out that NASA is already trying to excite and educate the younger generations with efforts like Moonbase Alpha (2010), where players must face the threat of a meteorite that damages the life support infrastructure on a lunar settlement, working with other astronauts to solve intense challenges within a short time span. There’s also the Station Spacewalk Game (2010) that allows players to conduct Extravehicular Activities (EVA) that real astronauts have accomplished in the past while also exploring the ISS via realistic 3D simulations. The Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral takes gaming and simulating further with a roller-coaster-like launch simulation. Players are escorted into their seats and strapped in for the ride while being briefed about the dangers of a typical launch before being tilted backwards in preparation for blast-off, anticipating and facing the roar of the engine and forces that make it an unforgettable experience.

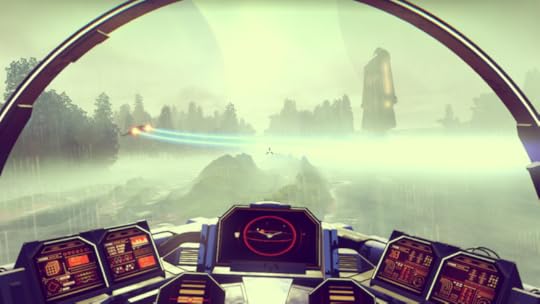

There is also what seems to be a whole movement right now that’s dedicated to creating creating space simulation games that capture the off-world thrill of it all. Space Engineers (2013) focuses on nuts-and-bolts situations and fixing up a virtual spaceship. While Kerbal Space Program (2015) is probably the closest right now to a real space mission in which players are subjected to the stresses of real science; launching rockets and trying to avoid deadly explosions. And for all the dreamers out there, the upcoming No Man’s Sky is probably the best bet, providing stunning visuals of celestial bodies and far-away galaxies and planets, granting players the freedom to explore an entire universe and chart its many ecosystems.

It seems that the major difference between Commander Hadfield’s experiences with simulations and those of subsequent generations will be accessibility and familiarity. Videogames are steadily closing the gap between a person’s interest in exploring space and them jumping into a realistic simulation of a space mission. Maybe the next Neil Armstrong or Mae Jemison will grow up inspired by these virtual realities, landing on Mars from the comfort of their couch before transforming that childhood dream into a beautiful reality.

Absolute Silence pushes the idea of a “game album” forward

The concept of a “game album” is hardly new but Davide A. Fiandra’s effort has a more specific goal: to capture good “record flow.” Titled Absolute Silence, Fiandre’s game album is a series of lo-fi and abstract experiences. Many of them do have a musical component but it’s supposed to be the mechanics rather than any audio that creates the flow. With that being the case, the album could be said to be a dreamy, contemplative series of stops and starts—sometimes exhausting, other times frenetic with energy before tapering off.

The album begins with “PLAYING PEGGLE AT 3 A.M,” which establishes the drowsy tone that will carry through the rest of the album. You fire balls into a pachinko machine while trying to regularly stick to a rhythm dictated by shrinking circles. There’s no score here and no way to win. The only end comes in the form of an eye-shaped aperture that slowly closes over the screen the longer you play. The notion, then, is that the rest of the album is a late night crawl through ennui and, indeed, Fiandre confirms that he worked on each of these games “in a non-awesome period of [his] life.” This might explain the dull grey color that dominates the album from start to finish—there’s a sense of lingering depression.

The following two games, “CREATION IS A HOPELESS QUEST FOR ABSOLUTE SILENCE” and “THE CUBES ARE STUCK” further feed into this tediousness. The first of these has you play a variation of Tetris (1984) with only rectangular blocks. You must maneuver each of them as they fall to fill the entire screen as if creating a wall. Each block adds more noise to the growing cacophony of musical sounds. And as the stack of blocks gets towards the top of the screen the pressure rapidly increases along with the volume. Given the title of this game—”CREATION IS A HOPELESS QUEST FOR ABSOLUTE SILENCE”—it’s plausible that Fiandre’s idea here is that each block represents a project, one that its maker hopes will satisfy their creative needs, working towards a satisfying silence. Yet each project (i.e. block) only multiplies noise and the effort soon tumbles out of control.

they recall the delight of creating music with digital tools

“THE CUBES ARE STUCK” is similar in that it gives you a maze to navigate that soon becomes exhausting. To succeed in this maze you have to solve block-pushing puzzles and also dodge deadly particles, sometimes separately, sometimes simultaneously. It’s tough going. And your will to continue is easily broken down by the constant reminder of an inventory box at the bottom of the screen that shows you how many items you still have to collect. You also need to figure out how and when to combine these items into new blocks. The garish art—mud-brown blocks and blurry red bullets—only encourage you to give up. Luckily, you can if you wish by skipping to the next game.

It is after these three initial games and the interlude that Absolute Silence begins to pick up some pace. Having demotivated you, the next three games in a row are shorter, more immediate, and absolutely musical. In fact, being so abstract, they recall the delight of creating music with digital tools. “MINUS ONE” has you shooting geometry with violent, glitch-like results. “NO INSIDE NO OUT” is a gentle, first-person wander through a two-tone forest of sharp pillars. “BETWEEN BEING” demands that you collect circles and click squares as they appear, with each of them lending a different sound to the mix, but also steadily shrinking the circle you control until it disappears. This last one is like a gradual fade out from this hat trick of more delightful games; from energy back to lethargy.

And so comes a return to the wearisome palette of “THE CUBES ARE STUCK” in its “REPRISE.” It returns as if a drought in creativity, the comeback of depression; like an artist losing their inspiration and leaning back into old habits. This reprise is easier going than the original game due to a single mechanic: invincibility. You push blocks onto lighted floor panels and your white circle turns green. With that, you can walk through the lasers and bullets that frustrated you earlier in the album. The implication is perhaps that the artist has found a way to cope with the obstacles in their life.

This idea is further cemented by the album’s “OUTRO.” You catch shapes as they fall, each success puncturing the black with a small circle that steadily grows. These circles add a lighter tone and music to the animated canvas. However, you can only move around in the black parts of the screen, so your maneuvering space shrinks. Eventually, you have no choice but to succumb to the noise as you get stuck between the circles; forget the pursuit of silence. This surrender seems comfortable, relaxing, perhaps even liberating. And so what Fiandre’s game album seems to connote is a journey through depression and tedium that ends with a way of coping with it. It doesn’t feel like victory, as overcoming depression never does, but there’s a sense that the artist has figured out how to live with it. Perhaps they’ll be able to create once again.

The Flame in the Flood floats comfortably in the shallows

I can think of few landmarks more American than the Mississippi River. It carves a slow, muddy path through the states, branching out as various smaller systems and tributaries that form the vessels of the country. The Mississippi carries with it the stories of Mark Twain and William Faulkner, the verse of Langston Hughes, the sounds of the Delta blues, the steady rhythms of riverboat paddle wheels, and the ghosts of those claimed by its waters. Perhaps my own Southern heritage has colored my perception of the river to an overly-romantic degree. But there is a mythic current that carries the stories from Minnesota all the way down to New Orleans before spilling out into the Gulf of Mexico, leaving traces of untold tales like so much flotsam and jetsam scattered along its banks.

I don’t know if the river that drives the action of The Flame in the Flood is supposed to be the Mississippi, but I’m hard pressed to see it as anything else. The game drips with a backwoods atmosphere ripped straight from a riverside campfire tale. A picaresque float trip through the wreckage of a nation, The Flame in the Flood chronicles the struggles of a young woman named Scout and her canine companion Aesop. Making their way down a river to meet some vague end, Scout and Aesop stop only to forage or barter for supplies, hunt for food, or find a safe place to rest before heading back to their raft to continue on their journey.

A picaresque float trip through the wreckage of a nation

Part of what makes this journey worth taking is its difficulty. The Flame in the Flood constantly deals out challenges in the form of deadly rapids and meager supplies. And so it is that each attempt to conquer the waters of a flooded America is an exercise in stubborn resilience that, for me at least, ends with Scout’s death. Succumbing to either starvation or to wounds suffered after encountering a pack of wolves becomes a routine ending for each trek down the river. With each death, however, comes a stronger understanding of the river’s challenges. You also learn that any supplies left in Aesop’s bag carry over to the next attempt—encouraging you to frantically scramble through your pack to save the most useful items for the river’s next pilgrim.

Upon each journey’s outset, the river creates new rapids and obstacles; the various camps and outposts, too, adapt to the river’s new course, popping up in new places among the river’s islands and banks. It’s a clever manifestation of the old adage, “You never step in the same river twice,” here delivered with a folksy twang instead of Heraclitus’ prose. The Flame in the Flood begs for exploration while twisting away from the player as she attempts to explore every place she can. Navigating the river means making the difficult choice of where to embark, what to carry, and what to leave behind in that moment of acceptance when the fire goes out and the cold creeps in.

This steady loop of embarking, exploring, and expiring cultivates an ominous atmosphere that melds with rough textured designs of the characters and their ramshackle environments. With their asymmetrical faces and gangly limbs, Scout and the people she meets look like rough-hewn dolls carved from the ominous trees that stand guard on the river’s flanks. Chuck Ragan’s mournful and stirring soundtrack bellows out gruff thematic annotations designed to spur you onward and lament your inevitable collapse. Such a mixture of sight and sound creates a folklore parable of struggle and hardship in world that, in losing civilization, has regained its mystery.

I suppose that struggle alone is enough to buoy The Flame in the Flood, at least on a purely mechanical level. Though it may be my new favorite survival game, The Flame in the Flood seems uninterested in uprooting some of the thematic implications of its setting and atmosphere. The game invites comparison to American traditions like travel narratives, Southern Gothic fiction, or pioneer folktales, yet it never attempts to penetrate the heart of what makes such stories so compelling. With its rafting sections broken up by excursions into the wild, the game evokes the structure of Twain’s Huck Finn (1884), but only as a gameplay template. The freakish people Scout meets—feral children, strange old crones, half-mad merchants—carry the hallmarks of writers like Flannery O’Connor for purely cosmetic purposes. But there’s no attempt to dig into the guilty past of the territory or to make any assertion about the freedom from shackles of history.

It seems like a missed opportunity, to hearken back to masterpieces of American literature and do nothing with them. Instead, The Flame in the Flood paints a picture of post-apocalyptic America without bothering with the more uncomfortable implications of what that would mean. Despite the brutality of the survival elements, the game’s America is a comfortable, sanitized one, from the charming character design to the pleasant music. It’s a game that ignores the struggles that inspired great American literature—the difficult legacy of race relations, the human cost of Manifest Destiny, the struggle for freedom from colonial rule—to instead use the hallmarks of such fiction as simple set dressing. Even as the river changes on the outset of each journey, the game offers a static picture of an America that never existed, more Cracker Barrel kitsch than Twainian epic.

Such omissions do not exactly hurt The Flame in the Flood. Its view of America is simple, but simplicity keeps the game focused on survival in a wilderness that refuses to be tamed. Though the river never captures part of the mythic grandeur of the Mississippi, maybe there’s something comfortable in the uncomplicated rhythms of Scout’s journey along its torrential currents. It’s enjoyable despite its difficulty, little more than comfort food with a bit of bite. And while there’s nothing exactly complex about it, I reckon there’s always a place at the table for some home cooking.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

March 8, 2016

Make murder look like an accident in Death’s Life

If you were to rap your knuckles across Death’s wooden door you might expect a black hooded cloak wielding a scythe to welcome you in. This is the most well-known image of Death over here in the contemporary west. But the personification of our greatest fear has a rich history and comes in many forms. In Slavic mythology, a female demon called Marzanna is known to bring death, winter, and nightmares. In East Asian mythology, Yama is the wrathful male god that judges the dead and oversees hell (Spelunky players will be familiar with this). In Latin America, festivals are held to celebrate Santa Muerte, the female saint of death—a skeleton often adorned with flowers—reminding locals of their own mortality during the celebrations.

It seems we have always realized Death as a figure not unlike ourselves, as a twisted humanoid that hunts us, a mirror image of our inevitable decay. But there is at least one exception to this rule. It’s found most recently in the Final Destination series of horror films. In these, a group of characters escape their deaths due to one of them having a premonition. This messes with Death’s design. And so, for the rest of the film, each person in this group is hunted down by Death and eventually killed (well, almost all of them).

play the scenario and see if death happens

But Death doesn’t come to them in the form of an ambling skeleton or a blade-wielding killer. Final Destination depicts Death as a force, perhaps like gravity or friction, one that invisibly tweaks the physical environment so that each of its targets finds themselves at the end of a particularly nasty Rube Goldberg machine.

This idea has now been translated to videogames. I’m surprised it’s taken this long. Umbu Games has made Death’s Life, in which you play as Death’s apprentice and must learn how to stage an elaborate, deadly accident in each level. It’s a puzzle game with a grim premise. In one level of the current demo, you assemble the crockery, cutlery, and other props of a grubby kitchen so that its owner will slip over when they enter and eventually be killed by a knife landing in their gut.

Coming across a solution can be a bit too trial-and-error at times. This is because each object in the level has a specific position it needs to be in. The puzzle is working out which position is correct. Click on a broom and it’ll shift to the left or the right. Click on the drying rack and the two plates sat in it will take different positions. Once you’ve decided on each object’s position, the only way to see if your arrangement is correct is to play the scenario and see if death happens. Most of the time it won’t, as if any single object is placed wrong, your Rube Goldberg machine will fail.

Conceptually, Death’s Life is tried and tested—we love stagey death sequences—and when it works it is as satisfying as you’d expect it to be (I ended up self-applauding my manufactured murder once). But it’s a little too obtuse and not always intuitive. What it could do with is letting you flaunt your own deathly creativity rather than forcing you to figure out a single solution—at least offer multiple solutions. Perhaps that will happen, as right now Death’s Life is only a demo, and is still a work-in-progress. Death, however, will hunt you down without fail. Unless those near-misses we sometimes have with death are the Grim Reaper’s equivalent of failing to complete a level.

You can download the Death’s Life demo on itch.io. You can also vote for the game on Steam Greenlight.

A videogame is being used to humanize Dakar City’s child beggars

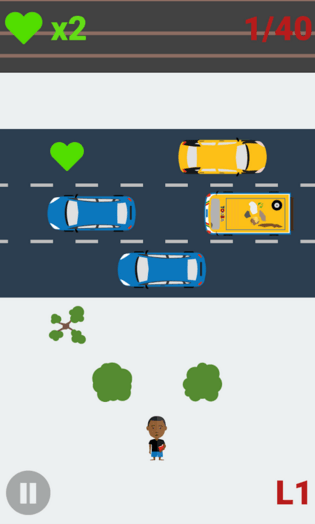

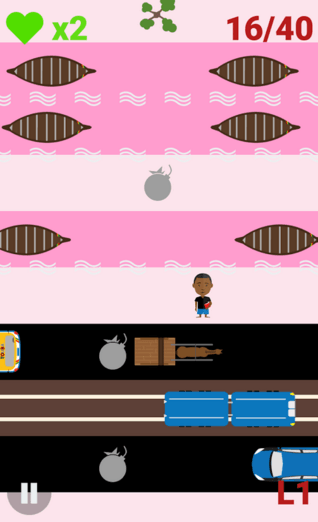

If ever a title exemplified the ability games have to comment on important issues, it’s Senegal’s Cross Dakar City. Essentially an updated version of Frogger in the vein of Crossy Road, its goal is simple: you are a young boy named Mamadou trying to cross the various streets, railroads, and rivers of Senegal’s capital city, Dakar, without running into any obstacles along the way. Unfortunately, traffic is indifferent to you, and you’ll have to dodge any number of vehicles, trains, and even bombs just to get home. This is because, as Mamadou, you are a talibé, or child beggar, and something as simple as pedestrian right-of-way is out of reach for you.

In Senegal, enfants talibés—talibés for short—are students at daaras, or Quranic schools. Because many families aren’t able to pay the costs associated with sending their children to regular local schools, they instead enroll them in these daaras in hopes of securing them a better future. However, the religious leaders (called marabouts) who run these schools sometimes exploit their students, sending them out into hectic and dangerous streets to beg for cash.

“People are not doing anything to help them,” Cross Dakar City’s developer, Ousseynou Khadim Bèye, told Okayafrica. “For most Senegalese, they are part of the decor.”

So Bèye took action, hoping to humanize Senegal’s oft-forgotten 15,000 child beggars through the use of play. A native game developer who studied at the city’s Ecole Supérieure Polytechnique Dakar before moving to France to intern with Ubisoft, Bèye developed Cross Dakar City to help bring attention to the problems faced by talibés as well as educate talibés themselves about traffic safety.

“Many child beggars, who are as young as seven, become accident victims,” he told VICE’s Motherboard. “They are also subject to kidnappings and sexual abuse.”

the response to Cross Dakar City has been overwhelmingly enthusiastic

So far, the response to Cross Dakar City has been overwhelmingly enthusiastic. As of now, the game has been downloaded close to 36,300 times, becoming a major hit in Senegal while also enjoying some success in France and the US. It’s a heartwarming outcome for Bèye, who was worried that he might be told not to focus on videogames while his home has basic needs still unmet.

For Bèye, however, addressing these needs isn’t at odds with making games, but rather an integral part of it. As he told Okayafrica, “People should be more oriented to resolving solutions than just learning programming languages…learning languages without applying them is not useful.” As such, he’s already partnered with a local organization that tries to place talibés in regular schools, and he one day hopes to make games alongside major human rights groups like UNICEF or the Human Rights Watch. Eventually, he’d like to set up his own independent game studio in Dakar with a focus on making games with African themes and messages.

Joining the likes of Cameroonian fantasy game Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan and cathartic Nigerian mosquito-murder-simulator Mosquito Smasher, Cross Dakar City marks a trend across West African game developers looking to explore their culture and important local issues through games.

You can download Cross Dakar City for free over Google Play and the App Store.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers