Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 155

March 1, 2016

Videogames and the art of spatial storytelling

French philosopher Guy Debord talked about the idea of the dérive, a mode of travel where the journey itself is more important than the destination, where travelers “let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.” But to think of dérive as a kind of random stroll dominated by chance encounters would be to miss Debord’s essential point: spaces, by virtue of being inhabited or shaped by humankind, possess their own “psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.” Spaces can be designed. They can be made to promote certain pathways, encourage specific behaviours, even elicit emotional reactions.

While impactful, this idea isn’t new. Humans have been engineering the social and psychological affordances of architecture and urban planning for centuries. For example, archaeologist Michael E. Smith argues that empires such as the Aztecs, with their neatly orthogonal capital city of Tenochtitlan, used city planning both to reinforce the cosmological beliefs of the Aztec religion, and to legitimize the political authority of the empire among the people.

In fact, if we take into account humankind’s original role as both a predator and a prey species among the vast savannahs of Africa, it isn’t hard to posit that a powerful awareness of space and place is intrinsic to our humanity. In fact, psychologists Yannick Joye and Jan Verpooten do just that, taking a Darwinian approach to analyzing the role of monumental architecture. They assert that the erection of what Michael Smith describes as “constructions that are much larger than they need to be for utilitarian purposes,” both a) parallels threat displays in the animal kingdom, signifying the might of the builders, and b) exploits our natural sensitivity for “bigness” to instill feelings of awe. In other words, we are biologically programmed to be highly sensitive to space, place, and location.

Mice and Mystics image via Flickr.

Games and Spaces

Spatial design is so important to us, that its principles transcend even the physical world of architecture and enter the fictional realm, especially that of games. the In the 1940s, Dutch historian Johan Huizinga published his ideas about the “magic circle”; a “consecrated spot” where play occurs (“the arena, the card-table… the tennis court”). Taking into account Huizinga’s ideas, you can argue that, fundamentally, the act of playing a game is the act of delineating a boundary that separates the mundane world from a mystical, created one—a world that is governed by rules different from everyday life. The concept of the “magic circle” applies even more to games that try to tell stories: any such game is unavoidably about the ‘where’ that the story takes place in.

Think about children playing make-believe, overlaying the real world with imaginary landmarks, superimposing an impenetrable citadel onto a jumble of pillows, varnishing a gnarled tree with magic and mystery. Similarly, sitting down for a rousing game of Dungeons & Dragons, is essentially about plunging into a fantasy world of enchanted forests, sinister dungeons, and caverns that stretch deep into the earth, ripe for exploration. Any boardgame that carries even a shred of narrative either includes lush artwork featuring the locations you visit, or force the creation of a psychic space: take the beautifully detailed stone floors of Mice and Mystics (2012), or the wind-tossed dragons of the minimalist game Tsuro (2004), that hurtle through only the open skies of your imagination.

Videogame designers, of course, often choose to focus a great deal on setting. The Mushroom Kingdom in Super Mario Bros. (1985) has a very particular aesthetic; BioShock’s (2007) underwater city Rapture is frightening and sad, and the upcoming No Man’s Sky promises a gargantuan, mathematically-generated galaxy brimming with impressionistic landscapes. But more than just provoke an emotional response, carefully constructed spaces allow for a different kind of storytelling. “Environmental storytelling”, where spatial elements are used to reveal or further the story, has become somewhat of a buzzword within gaming circles. As media scholar Henry Jenkins puts it, “…a story is less a temporal structure than a body of information… a game designer can somewhat control the narrational process by distributing the information across the game space.”

CAREFULLY CONSTRUCTED SPACES ALLOW FOR A DIFFERENT KIND OF STORYTELLING

Videogame designers, more than almost any other art creators, are furnished with near-limitless options regarding what they can do with the spaces they create, as well as what happens to the players who choose to inhabit them. They can, very literally, fashion any sort of space they care to dream. But for all this power, and all the narrative potential of space and place, most videogames follow a fairly traditional route to storytelling, using the space only to supplement a linearly (as opposed to spatially) told narrative. “Generally speaking,” argues Jamin Warren about videogame stories on the video series PBS Game / Show, “games are fairly straightforward when compared to other mediums.” If you look at other entertainment and artistic media, examples of unconventional storytelling structures abound. Dhalgren, science-fiction behemoth Samuel Delaney’s hugely successful 1975 novel, is mind-bogglingly circular in its narrative construction. Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) would be a far less compelling film if watched in chronological order. And readers of Neil Gaiman’s towering Sandman series of graphic novels are used to drifting dreamlike between different time periods—the latest book, The Sandman: Overture, is set simultaneously before and after the conclusion of the original series. Unfortunately, within the realm of digital games, where unusual narrative structures would assumedly be easier to create thanks to the magic of computer code, such variety is infrequently encountered.

Theater and Immersion

Paradoxically, some of the most interesting examples of non-linear, environmental storytelling seem to be taking place in the medium where space is the most difficult to engineer: the real world itself. The increasing popularity of “immersive theatre” experiences, where audiences are physically brought into elaborate sets designed to be explored, reveals that engaging stories can indeed be communicated through space. And I don’t just mean visually. Scott Palmer, quoted in Josephine Machon’s 2013 book Immersive Theaters: Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance, describes immersive theater as a “phenomenological multi-sensory experience of place,” where, “visual, oral, olfactory and tactile elements become an integral and often heightened part of the audience experience.”

Immersive shows can be seen as a natural extension of the practice of theater. Throughout its history, the theatrical world has been highly concerned with representations of places. Even in London’s famous Globe theater, for instance, with its minimalist sets, Macbeth’s Duncan made sure to loudly proclaim, “This castle hath a pleasant seat,” lest his audience forget where the action was set.

One of the most famous immersive theatre companies is the English Punchdrunk, whose sprawling, macabre experiences have gained international repute. In many Punchdrunk shows, audience members are left to wander an expansive, often ghoulishly eerie landscape in a kind of Debordian dérive, drifting where their interests, the characters, or currents of other viewers take them. Interestingly, Punchdrunk’s works are themselves influenced at least somewhat by videogames. When talking about one of their shows, Punchdrunk’s artistic director Felix Barrett told The Guardian, “It’s similar to how in Skyrim you can follow a character and go on a mission, or you can explore the landscape, find moments of other stories and achieve a sense of an over-arching environment.”

The Case of Sleep No More

Parallels to games are hard to miss in Punchdrunk’s most talked about show Sleep No More, a 1930s, Hitchcockian version of Macbeth taking place in a set of converted warehouses in Chelsea. Their fictional McKittrick hotel is an open-world game, where visitors can set their own pace and choose what to see. Secrets can be discovered in hidden corners; one-on-one interactions with characters can be “unlocked” by being in the right place at the right time. You even experience Sleep No More as a character: viewers are asked to don bone-white masks at the start of the show, divorcing their “self” from the shadows or ghosts that they must become to fully immerse themselves in Punchdrunk’s world, and make decisions that only an in-game character would. In Felix Barett’s words (quoted in Machon’s book), the masks allow participants to be “empowered because they have the ability to define and choose their evening without being judged for those decisions…they have the freedom to act differently from who they are in day-to-day life.”

(Source)

But it’s Sleep No More’s almost textbook use of environmental storytelling techniques that’s really intriguing. Henry Jenkins describes four main ways in which in-game environmental storytelling “creates the preconditions for an immersive narrative experience,” three of which are heavily used by Punchdrunk:

1) “Spatial stories can evoke pre-existing narrative associations”

Almost everyone who attends Sleep No More has some notion of the Scottish Play’s basic plot. The show’s scenic design specifically reinforces the noir-Shakespearian world you’re in. Hecate’s apothecary is a good example. If you stumble into it, likely guided by the scent or sight of dried herbs and preserved animal parts, you will almost certainly make the connection to the three witches from the play, and perhaps even recall a few lines from the famous Witches’ Song. If you stay a little longer, you may even notice a thematic resonances between all the natural materials and Macbeth’s impending doom: “Nature has this huge power within this play, this sense of destiny and nothing you can do to stop it,” Felix Barrett told the New York Times, while describing the room. “Things are collected, crafted and manipulated.”

2) “Embed narrative information within their mise-en-scene”

Punchdrunk clearly ascribes to preeminent dramatist Antonin’s Artaud’s “less text, more spectacle” philosophy of scenic design: every space within the show is redolent with objects that convey story in a number of different ways. Participants may discover artifacts that contain text and image that further the story, such as Macbeth’s letter to his wife that participants can find and read. They may find clues that suggest events that may have taken place, such as the murder of Macduff’s children, revealed through the bloody sheets in their nursery. But sometimes, objects embedded into the show are bridges to outside micro-narratives, to be guessed at, pondered, wondered at. The bleak hospital room, for example, is filled with hundreds of locks of human hair, each carefully catalogued and stored. “This is very much the outer reaches of our world…there’s implied narrative…” Barrett recounts, “…many, many stories of people, the backstories of the characters…”

3) “A staging ground where narrative events are enacted”

Macbeth ends an agonized solo dance in a graveyard by dangling from a tree like a hanged man. Duncan, right before his murder, discovers a room filled with dozens of clocks, all striking midnight at the same moment. Clearly, spaces and set pieces can be used to enhance the story being told. But, concentrating solely on this “enhancement” would be to only shallowly engage with Jenkin’s point, and to ignore some of the most interesting, and also the most underutilized (especially in the gaming world) techniques of spatial storytelling.

Jenkins reminds us that the environment itself can direct the flow and rhythm of the story. Dramatic lighting, the architecture of the space, the echoes of music and sound through doorways, stairways, walls and ceilings; in addition to contributing to an atmosphere and emotional palette, all of these are also all used to guide participants through the scenes of Sleep No More. There is no one path being the “correct” or “best” way to experience the story, and seeing every scene within Sleep No More is almost impossible with just one viewing. Some would even argue that this is a trope within immersive theater, that visitors never get a “complete” picture of the story.

BUT FOR ALL THIS POWER, AND ALL THE NARRATIVE POTENTIAL OF SPACE AND PLACE, MOST VIDEOGAMES FOLLOW A FAIRLY TRADITIONAL ROUTE TO STORYTELLING

Rather, spatial design provides participants the freedom to forge their own routes, to glimpse parts of the story that perhaps no-one else notices, to weave together the nonlinear collection of narrative fragments that is unique to each individual’s experience and create one’s own interpretation of how they’re all connected. During a lecture at GDC 2015, game designers Matthias Worch and Harvey Smith reminded us that, “environmental storytelling relies on the player to associate disparate elements and interpret [them] as a meaningful whole.” Through individual journeys and personal synthesis, participants and creators almost become collaborators in telling a story. Which is, of course, the goal of many games.

The Case of Gone Home

It is precisely this “association of disparate elements” that can be used in the videogame world to tell more interesting, nonlinear, spatially-oriented narratives. Out of the few games that use this technique, one of the most talked-about examples would be The Fullbright Company’s 2013 release Gone Home.

Gone Home is a rare example of a game that was inspired by a theatrical piece, which was itself inspired by games: scholars Daniel and Sidney Homan inform us that the designers of Gone Home were heavily influenced by Sleep No More. They quote designer Steve Gaynor, who feels that in Gone Home, “players, like theatergoers, can choose where to focus their attention,” and that the “audience…occupies the same three-dimensional space as the fictional inhabitants.”

Gone Home is a first-person exploration game where players take on the role of Kaitlin, a college-age girl in the 90s, who returns home to find that all her family members have gone away. Much like in the best examples of immersive theatre, players get to explore the house and its contents, absorbing narrative chunks until a clearer picture of the story emerges. There are no enemies to defeat, no scores, no competitive element; the objective is simply to discover more of the story.

And even more so than in Sleep No More, much of Gone Home’s story is told through environmental elements. Yes, there are examples of recorded voice-overs that reveal snippets of the main mystery in the game, but to focus only on those would be to miss much of the rich layers of story built into the game. As vlogger Rantasmo explains, “it’s a game about people and objects, and about who those people are through the objects that they own, and the very deliberate way in which they’re placed.” Not married to the trope of cutscenes, some of most intriguing parts of the story are scattered around the house, in the form of letters, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, homework assignments.

But it’s not just textual relics that reveal the story. No, you can literally pick up and play around with the most banal of items. Empty binders, toilet paper, a model duck… Homan and Homan even contend that the presence of such everyday items is “crucial to establishing real emotional connections between the gamer and his onscreen representative.” Then again, some objects do reveal significant pieces of the story. Piles of Kaitlin’s father’s first book languish all over the house, evidence of his brief flash of fame as a writer. A Ouija board hidden in a secret panel points at attempts to contact the spirit of a dead relative. A tender photograph of two clutching hands is a testament to adolescent love.

Once again, you as the player are made keenly aware of the space you’re in, though this time, the lights, sounds and textures adorn a virtual world rather than a material one. There’s a childish thrill in discovering and traversing the secret passages that dot the house. Entering Kaitlin’s parents’ room feels vaguely transgressive. And finally reaching the attic, the one marked from the very start with signs and coloured lights, really does feel like the end of the game, a triumphant ascension to glory, high above the mundane trappings of the rest of house.

And once more, just like in Sleep No More, much of the story, much of the tying together of narrative strands, is left to you. Not all the narrative dots are connected for you and the game leaves a fair amount of wiggle-room in terms of what might have happened. Did your mother actually have an affair or are you just fancifully implanting unnecessary drama into the situation? Is the copy of Leaves of Grass (1855) you found indicative of some sort of midlife queer awakening in your father, or are you reading too much into it? Gone Home doesn’t care to tell you. What it does care to do is leave breathing room between each revelatory discovery, giving you time to mull over what you found, time to create your own links.

YOU AS THE PLAYER ARE MADE KEENLY AWARE OF THE SPACE YOU’RE IN

And therein lies the key difference between The Fullbright Company’s quiet little game and Punchdrunk’s grand spectacle. In Sleep No More, visitors are constantly on the lookout for references to Shakespeare, or nods to Hitchcock. While the piecing together of the story elements is a personal experience, it’s always coloured by the presence of the reference material. Gone Home, on the other hand is virgin territory. A player goes in tabula rasa, armed only with genre tropes (many of which are playfully upended). Using signposts and hints supplied by the designers, players fill in all the gaps in the story within their own heads, because the game leaves you somewhere in between knowing and not knowing all the details. Even Felix Barrett comments on this: “Gone Home has an implicit narrative,” he told The Guardian. “You’ve either just missed the action or it’s just about to happen and you’re suspended in-between.” It’s this kind of nonlinear, almost emergent form of storytelling that makes Gone Home stand out from other videogames.

Non-linear stories, non-linear games

Humankind is obsessed by the concept of space, owning it, controlling it, changing it. Yet, even with our relentless quest to shape the spaces around us, so are we changed by them in turn. In his essay, Guy Debord quotes Karl Marx’s famous line: “Men can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves.” All around us, spaces are constantly filling up with stories, messy, nonlinear stories with no clear beginning, middle or end, stories of which we catch only fleeting impressions, stories that we each absorb and interpret to fit our own personalities.

If interactive experiences like Gone Home and Sleep No More, both of which defy their genre expectations (Is it a play or a game? Is it a game or a film?), have anything to teach us, it’s that we can very much rely on audiences to fit pieces of the puzzle together, and even to come up with their own, uniquely shaped pieces to fill in the holes. The world of gaming can very much embrace that the “magic circle” can be defined both by the creators as well as the players.

Header image via Flickr.

New podcast is dedicated to discussing death and videogames

A new podcast called PlayDead explores the intersection of loss, death anxiety, death positivity, and game mechanics. It’s hosted by Gabby DaRienzo, who openly confesses to being obsessed with “death positivity.” And, in fact, DaRienzo wrote a piece for Kill Screen last year, titled Death Positivity in Videogames, which foreshadows the focus of this podcast in many ways.

It’s a podcast that seems to be actively looking to contextualize videogames as yet another artistic medium exploring the theme of death. Even the earliest videogames such as Spacewar! (1962) are predicated on the idea that a game ends when a player dies. Often it’s the case that GAME OVER = Death of the player and/or losing the game. Diving into what videogames have to say about death proves to be a rich topic with plenty of history behind it. That should be no surprise given that our mortality is a fundamental part of what is quite severely termed “the human condition.”

Further, PlayDead argues that we are often largely unaware of death and any meaningful impact it has beyond being a means to progress, or to ending progress, within videogames. However, that does not mean that many games are not, or have not, been looking to explore death in new ways, or that the more “stale” aspects of death in games have no worth.

what videogames have to say about death is a rich topic with plenty of history behind it

Another core aspect of PlayDead is to unpack where our perceptions and feelings about death come from. In a world where every community and culture, the world over, and throughout history, has engaged with death in so many ways, it’s odd that we often have a very Eurocentric idea of death. Death is something to be feared. This is easily shown through the now almost ubiquitous figure of “the Grim Reaper,” whose personified form of a black-hooded, scythe-wielding skeleton originated in medieval Europe. This figure, as well as its accompanying associations of fear, villainy, and darkness, were deeply entrenched through Gothic fiction of the 18th and 19th century, which has gone on to inform mainstream media’s depictions and understandings of death today. The awareness of this is shown tongue-in-cheek through the podcast’s emblem of the Grim Reaper playing in an empty arcade.

The very first episode of the podcast tackles this through the discussion with Augusto ‘Cuxo’ Quijano, the Concept Artist at Drinkbox Studios, who is known for their game Guacamelee! (2013). Quijano describes wrestling with ideas and feelings of “death anxiety,” and how working with the idea that a death realm may not be the gloomy, Gothic trope it’s so often made out to be was part of an incredibly cathartic and important process. This allowed him to think of death differently on a personal level, as well as cause it to manifest differently through the game’s mechanics. Hence, in Guacamelee!, the death realm is showed to be glowing and bursting with a vibrancy normally relegated to the association of life.

The second episode explores ideas of players killing themselves within videogames as a means to to push and explore the boundaries and mechanics of the game. It also delves into the larger theme of feelings of suicide and self-harm from a game creator’s perspective. It also takes on the concept of martyrdom, both in real life as well as within videogames, and how characters and their deaths within games are often framed as noble or part of the grind of achieving a higher cause (such as succeeding in the game). This can become absurd when players are simply testing the boundaries of the game or, for example, even deliberately trying to kill their character off to see a new cutscene.

Be sure to subscribe to PlayDead on iTunes, or listen via Dork Shelf or your podcast player of choice.

You can also follow Gabby DaRienzo and PlayDead on Twitter

Stardew Valley brings in a full harvest

There is no point in kicking sticks around over Stardew Valley’s similarities to the Harvest Moon series, Natsume’s long-running farmlife simulator. Not to be confused with the also really good Neil Young album, “Harvest Moon”, which Stardew Valley does not riff upon outside of the honkey tonk atmosphere in the single’s bar waltz music video. And that is probably a coincidence.

Stardew Valley is an homage, a send up, and there is little mistake to make about that. It likes Harvest Moon a lot, and those who like Harvest Moon will probably like it in return. It likes the graces of the seasons, drifts of winter snow and spring’s cherry blossoms breezing through the air. It likes the innocent and isolated towns, full of mild-quirk townsfolk and not a one among them threatening. It likes escaping there, the prologue having an emphasis on fleeing an office cubicle. It likes filling a wooden box with grown produce, foraged flowers, and fish. It likes falling in love and getting married. It likes having a playful dog.

We see games in love a lot. Games that love Mario and Zelda, and wear that love on their sleeve; they’re in high supply. The more important question is, when love letters blush this hard, why would you play simulacra over the simulated? In small gestures, which mount enough to fill a silo, you can spot the fork in the road where the cultures and the sentiments between the American-made Stardew Valley and Japanese-made Harvest Moon’s split.

the different sentiments between the American Stardew Valley and Japanese Harvest Moon show

The first thing you’ll notice upon arriving to your little farm is that it is massive. It would be in-game weeks before I bothered seeing its full parameters. It’s initially so overrun with rocks, tall grass, and unwanted trees that I felt like Bart Simpson asking Mrs. Glick which ones are the weeds, hoping I wouldn’t need the iodine. I cut myself the land around my house to farm, holding off the rest indefinitely. Whereas Harvest Moon is conservative on the space, forcing you to be strategic with agriculture,the strategy in Stardew Valley is the opposite. It tests your modesty if you decide to build a beansprout Babylon—a god who makes themselves a garden so big even they couldn’t water it every blinking day.

And you can go big, too. Like Harvest Moon, Stardew Valley has a stamina bar, but it’s much more generous. You’ll get bored of farming before you get tired. For a while, I simply couldn’t find enough farming in the day to spend my energy on, instead exploring, fishing, and dabbling with the payloads of side-quests and minigames throughout the town. The excess strength is, perhaps, in reserve for crazier weekdays. Stardew Valley has all these things it wants you to enjoy.

The Harvest Moon games project a fairly Japanese mentality that work—successful labour day in and day out—is its own zen-like reward, hard lives lived well. Stardew Valley has far more rewards, treasures in a mini-roguelike cave crawling quest, a far off desert to explore, a museum to curate, courting a mall goth or just the satisfaction of spelling out your favourite meme in cauliflower across your estate. Produce is also more expensive in Japan, and each piece of purchasable produce has an element of craftsmanship. Perfect dodgeball-sized apples are the standard and a meal-sized portion, while the west is familiar with bags in bulk as to compliment a balanced diet. Even the locations of your home, in Stardew Valley starting on the left, Harvest Moon often on the right, seems to shadow how one reads English and Japanese. That, again, is probably just an odd coincidence.

There are bounties on potatoes and fish you can fill. There are dozens of local yocals to socialize with, from the shopkeepers to the survivalist living in a tent to the literal wizard. The wizard is introduced as part of a side-plot to save the magical-slime infested community center. Saving the decrepit town institution links arms with a different side-plot involving a Wal-Mart conglomerate muscling in, eying the land, and threatening the community’s fragile essence.

the expanse of farmland is clearly given to you in a Minecraft-ian gesture

Stardew Valley has a lot of things. It’s got scents of Animal Crossing in there; some of the collection and decorational aspects. And the expanse of farmland is clearly given to you in a Minecraft-ian gesture, encouraging you to go wild with your detailed visions of gardening or ornate crop circle patterns to maintain. Harvest Moon is not that game, and its bells and whistles are traditionally much more limited, structured, and harder circled on the calendar. Despite all odds, it seems Stardew Valley is a different game than the one it mimics. And a pretty fun, different game at that.

There will be plenty of overlap between the kind of players who enjoy both games, but wary be the worker who is concerned with the grit within the soil.

February 29, 2016

Inks will turn pinball into beautiful paintings

What’s the opposite of a pinball purist? Whatever it is, that’s me. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t mind pinball as a physical table game. It’s the translation to videogames that often bores me. The effort made is usually to simulate the table experience as accurately as possible. Yawn. This is a videogame—you are free of the bounds of the real world, do something else with the pinball format, geez.

There have been a few examples of pinball videogames with a lick of something fresher over the years. Sonic Spinball (1993), Devil’s Crush (1990), Rollers of the Realm (2014); they all embraced the idea that pinball doesn’t have to be a table, but could be used as a way to interact with a virtual fantasy world. Even that has become quite typical now, though. And so it is with delight that I look towards the latest pinball deviant, Inks, as it takes the game in a completely different direction to what has come before it.

this pinball game will resemble the act of throwing paint onto a canvas

Inks is to be the next game from the BAFTA award-winning game studio State of Play. For the past few years, the team has been crafting a miniature city out of tiny motors, lightbulbs, and cardboard houses for the adventure game Lumino City (2014). It’s a studio of people who enjoy taking a hand-made approach to a project, bringing a gorgeous materiality to their games. It makes sense for State of Play to be making a pinball videogame, then—bringing a table sport from the physical world into the virtual one. It also fits that this pinball game will resemble the act of throwing paint onto a canvas.

Yes, Inks is designed to be a visually beautiful experience, as opposed to one that prioritizes competition or chasing a score. The ball that you launch into the game area and bounce on the flippers leaves crayon-like trails in its wake, while a collision with a wall or another solid object is said to cause “blocks of color [to] burst like beautiful fireworks across the surface” of the playing space. The idea, according to what State of Play told Polygon, is to build up a “visual history” of your time playing the game right as you’re doing it as you attempt to increase your score.

Right now, there are no more details on Inks, but the visuals provide plenty of stimulus to form an idea of what we’re gonna get here. Plus, it will apparently be getting a release date soon as it heads to mobiles, which suggests you won’t have long to wait until you’re downloading it for yourself.

h/t Polygon

A videogame about the impossibility of grieving for Pol Pot

“Much of the experience of the site takes place in one’s head,” says the itch.io page for Cho-am, a new game from Aaron Oldenburg. The site described is the place where Pol Pot—the brutal dictator behind the Cambodian genocide in the late 70s—was cremated. In “real life” Cambodia, this site is near the Thai border, and is host to a small shrine made up of a tin roof over a mound of ash and dirt. Sometimes it is decorated with flowers or incense.

Cho-Am deals with the difficulty of understanding the way others process incomprehensible national trauma. Oldenburg writes of the shrine and the religious respect, “This is a way of dealing with the memory and presence of someone responsible for pain and destruction… outside the realm of forgiveness and punishment.” How do we begin to create sense out of senseless killing on this scale? How do we treat any relevant location or memory?

(Source)

As the player navigates the space, the game’s camera jumps from place to place depending on the position of the avatar—a naked, cream-colored figure—as though it were helping to give the player a better view, but it doesn’t move to frame the action, it moves erratically and confusingly, jumping from one side of the character to the other, making it hard—maybe impossible—to situate oneself. If you move beyond a certain distance, the camera zooms out and switches to black and white as if to suggest an external observer and highlight the distance of the player from the space.

a lot of fractured pieces to put alongside one another

When it switches back, a black inset appears in the corner—a close-up of the character—and the character performs an action in that halting inhuman way that 3D models sometimes do. The figure vomits, or pounds the ground, or falls over, and shakes itself. The actions themselves are recognizable, familiar, and affecting, but alien in their presentation. We can say “I know what that feels like,” but the skinny person on screen is not acting like I would, moving like I would, processing grief like I would.

Every so often, dream-like images are presented as if in puddles—a bed, a bull, maybe a kidney? They look like they’ve been scanned in from cocktail napkins, which puts them in stark contrast against the jarringly tiled and textured look of the rest of the world. There are occasional plaques, with dedications like “HERE IS THE PLACE WHERE I DISCOVERED THE NUMBERS,” or “THIS IS THE LOCATION WHERE HE CAME AND SAT ON MY BELLY.” These objects—collectable, but inscrutable and directionless—feel scattered, and the world feels at once unfamiliar and repetitive. There are a lot of fractured pieces to put alongside one another and attempt to make sense of, but on the other hand, “much of the experience… takes place in one’s head.”

Solstice leaves its best mysteries unsolved

In the eighth episode of The X-Files, agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully are dispatched to investigate radio silence at a science outpost in Icy Cape, Alaska. There they discover a parasite—because it’s always a parasite—that makes its host hyper-violent. Suspicion and fear threaten to tear the team apart as they search for answers. In the knick of time because it’s always in the knick of time—reason and rationality prevail, temporarily giving order to the chaos and showing our protagonists a way forward in their eternal search for the truth.

Solstice similarly follows the first-person accounts of Galen, a doctor, and Yani, an engineer, both outsiders sent to investigate a city during its three months of weather-induced isolation. Constructed on the site of unusual hot springs through a combination of magic and engineering, this “Jewel of the North” serves as a trading oasis in a desert of snow for the rich merchant families who control it. After Lev, a neurotic archeologist obsessed with the mysteries surrounding the city and phenomena that sustain it, disappears, a series of betrayals and mechanical failures lead Galen and Yani deeper into a conspiracy that threatens to undermine the city and its few remaining inhabitants.

Early on, one of the game’s characters says, “Insanity is hardly rare in this city. The rest of us are just better at hiding it.” The line serves as a sort of mantra for Solstice, a Chinatown (1974) inspired visual novel whose homely interiors and warm colors mask a city fraught with tragedy. Instead of extraterrestrial parasites there are only flawed human beings and the damaged psychologies that motivate them. The creators stress that there’s no evil in Solstice, only circumstances.

If the setup sounds cliché, it’s also extremely practical, serving as a more than capable vehicle for creating tension that the player must then navigate through various dialogue choices. Hubert Sobecki and Agnieszka Mulak wrote the game together, a collaboration significant for how it gives Galen and Yani an equal sense of independence and unpredictability. Rather than blank-slate to be role-played, each comes with a unique personality and history that isn’t so much managed by the player over the course of the game as uncovered.

As professional problem solvers, Galen and Yani offer different modes for exploring these circumstances, one more mystical, the other more technical, each with their own agendas and motivations. Whereas games like Mass Effect (2007) encourage you to imprint your own personality or made-up character onto the protagonist, Solstice lets you come to understand its heroes by seeing how they react. The interplay of text, image, and sound is limited to mostly static scenes peppered with animated character gestures that resemble something you might find in a Reading Rainbow segment. In this way Solstice relies on the player to make it dynamic.

Messy relationships become wellsprings of new information and insight

I don’t like conflict. It makes me nervous and uncomfortable. I’ve never been in a fight and I’m easily shaken. While I don’t keep a tidy apartment and my car is a mess, I try to manage any emotional chaos in my life like an IKEA bedroom, maintaining an orderly appearance by shoving everything else into a cornucopia of bins, drawers, cabinets, and closets. Solstice resisted this urge, forcing me to come to terms with its characters and contradictions, no matter how much I tried to reconcile them.

The more I tried to make Galen act judiciously, the more his relationships to other characters faltered, hurting his investigation. Every time I tried to tone down Yani’s indignant righteousness, arguments only escalated. In Solstice’s case, friction like this tends to feel liberating rather than frustrating. Messy relationships become wellsprings of new information and insight. Conflicts and disagreements, it turns out, can be productive in their own way.

There’s a tendency in many RPGs with branching stories for the min-maxing of levels and loot to infect character interactions. Conversations become just another data point to be managed with the game scoring your results according to strict, artificial moral binaries. Even when there aren’t “best outcomes,” concern over lost quests or potential party members can make these encounters feel more transactional than narrative.

Intentionally or not, Solstice hints at this subtext in the way it economically and politically orients its characters toward one another. Istvan is the oligarch who employs everyone, making the inhabitants of the game’s city less like citizens than they are indentured servants. They are less a community in the traditional sense than a corporation whose office politics remain constrained by the explicit hierarchy on which it is based.

Having laid the groundwork for interrogating this dynamic, however, Solstice tends more toward murder mystery dinner theater than fantasy film noir. A penchant for playful melodrama and comedic banter in many ways undercuts the tension established through the game’s mystery and its interactive methods for unraveling it. That the characters always seem to stay uncannily true to themselves, no matter where the player nudges the story, is a virtue. That this truth doesn’t always feel as weighty as the circumstances creating it is not. In this way, the process of untangling Solstice’s many secrets and deceits often outpaces its results.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Delightfully surreal adventure Samorost 3 comes out this March

We got a glimpse of it last year, but now it’s been confirmed that the full, beautiful picture of Samorost 3 will be landing on this planet on March 24th, 2016 for Windows and Mac.

This is the next in Czech-based game studio Amanita Design’s Samorost series, which started back in 2003 as a free browser-based title about a small gnomish creature wandering through a biomechanical spaceship in an attempt to stop it from crashing into his home asteroid. The title did well, being nominated for a Webby Award and prompting a Webby-winning sequel in 2005, which carved the path towards Amanita’s larger, more well-known, and most recent titles such as Machinarium (2009) and Botanicula (2012).

As we see in the new trailer above, Samorost 3 promises a significantly more ambitious adventure than its predecessors, sending the player on a large-scale journey across seven different planets.

resembling painstakingly handcrafted dioramas

The surreal landscapes that made the first two Samorost titles so successful are back and seem even more detailed, resembling painstakingly handcrafted dioramas. Even the gnome has gotten a redesign, switching out his former watercolor appearance for something more akin to one of Nintendo’s microscopic creatures in the Pikmin series, only now wearing Little Nemo’s pajamas. It’s a fitting look, given the dreamlike and often larger-than-life places this little gnome will be visiting.

Most of the trailer’s time is dedicated to showing off the various oddballs the gnome will come across on his adventure, including a bespectacled professor type, an ape-man who quite enjoys hot springs, and an almost spider-like creature who shares a cup of tea. This may be a strange world, but it seems to be welcoming enough to those who are willing to be patient with it.

One of the choices Amanita has stuck with since the game’s first outing is that the player doesn’t control the gnome directly so much as they play an omniscient force that manipulates his surroundings to allow him to pass. Given the bizarre nature of these environments and their inhabitants, that often means unlearning assumptions and rather discovering how this alien world works from the ground up. It’s a classic surrealist theme, surprising the audience and making them check their expectations at the door. Samorost 3 asks the player to be open to new ideas about how exactly societies and and ecosystems entirely divorced from our own are supposed to work, indulging in the types of imaginative but rewarding brain-teasers that can only happen when traditional logic is thrown out the window-flower-robot-thing.

You can keep up with Samorost 3 over on Amanita’s website.

Twinescapes, or The Rise of Spatial Hypertext

At least 100 pages of four novels. At least 20 pages of maybe half a dozen others. Not one book finished, not even in rough draft.

These are the vital statistics of my long war with fiction. For most of my life now it’s been my fondest wish to write and to publish a novel. Sometimes I’ve wanted to author a book of the Great-American-sort, other times my ambitions have been more humble, or more genre-bound. Sometimes my drafts have been muddy slogs through self doubt, other times they came as if poured from a vase by a woman in a toga. But every time I ended up feeling like something was missing, like I was doing something incorrectable.

My biggest compositional struggle has been over the right ways to move characters through an imaginary space. When I started, everything I wrote felt too static, with the characters all sitting in chairs or standing statuesque in their rooms. But even after realizing this defect, I never really knew how to proceed. Do I use the progression of details to give the illusion of a character’s thoughts as he walks down a street? Do I describe her walking pace, or the nervous way she shifts from one part of the room to another? Do I do as Umberto Eco in composing The Name of the Rose (1980), when he drew a scale map of his medieval Italian monastery so that he could know the number of paces between the scriptorium and the stables? I still haven’t found an answer that satisfies me.

So it’s with personal interest that I’ve noted a new fictional form emerging within the world of games. Twine-based interactive fiction, text stories made of clickable links and branching pathways, straddle the very threshold between game and literature. And I think interactive fiction, in the hands of certain writers and designers, also represents a new formal association between space and text.

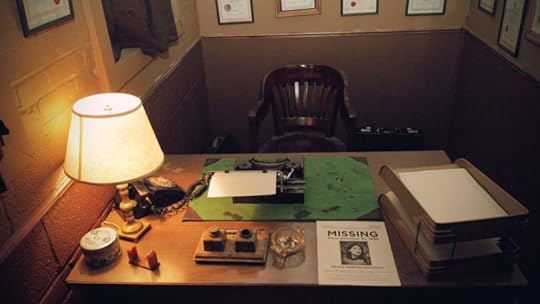

My inroads into Twine fiction was Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s With Those We Love Alive (2014). Told in the second person, the game thrusts the player into the role of an Artificer in service to an insectile Empress. Porpentine’s is a world where “Angel corpses rot in the sun” near a “dream distillery”, all of it “stained with smog and acid rain.” Her images are at once precise and yet broad enough to imply a whole deeper world. But this world is also given a feeling of physical depth, of spatialization, by the structure of Porpentine’s game/story. In a given passage certain words will be colored links, as in the following (with italics standing in for colors): “The garden stands over there. Your workshop is in a cabin down the path.” Clicking these links brings you to a description of the garden or of the workshop, respectively, and each of these descriptions might have links inside them as well.

This act and activity of clicking links serves as a metonymy for active motion between one place and another. In a traditional story the movement would be described on the page: “You walk from the palace courtyard to the garden.” But in Porpentine’s work, and the work of other interactive fiction writers, that fussy movement of characters like chess pawns is elided. What reigns instead is detail and an imagination of space.

this already spatial story is reaching out to haunt the physical world

What’s more, With Those We Love Alive is not a sort of “choose your own adventure story” made of unrecoverable choices. If you go from the courtyard to the temple you can go back to the courtyard and on, to the lake. These settings may or may not change from one appearance to the next, but even the repetition helps ground the game in a sense of spatial reality. You move around inside the story rather than tracking an inexorable march of words rightwards and down the page.

This desire for a spatialization of the text extends to one of the most often remarked upon features of With Those We Love Alive. The game asks you to draw symbols upon your body that represent abstractions like new beginnings and separation. In another place, the game asks that you—the player—hold your breath for a length of time. These effect are powerful, as if this already spatial story is reaching out to haunt the physical world.

If I were to generalize massively, I would say that the relationship between a traditional paginated novel and Porpentine’s work is that the former is about the passage of time while the latter is about movement through space. Which is not to claim that a novel can’t provide a sensation of dimension, or that With Those We Love Alive doesn’t have an affecting narrative. But I do want to point to the unique strengths of writing and design like Porpentine’s and how these strengths are different from the fiction that came before it.

This move towards a spatialized fiction is not sui generis with Porpentine, though. First of all, it is important to note that there was half a decade of work made on Twine before With Those We Love Alive arrived, and that much of this work set a touchstone that Porpentine has followed. But the history of interactive fiction is even deeper than that. Indeed, some of the very earliest computer games, such as Adventure (1976) or Zork (1980), communicated their worlds only through text and both described dark underground labyrinths and passages.

In the heady early days of the popular internet a loose collection of literary writers began taking up the mantle of “hypertext fiction”. Works like Michael Joyce’s Afternoon, a story (1987) and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995) were innovative in their use of hyperlink to produce a fragmented post-modern structure for the reader to explore, but these stories were more about textuality than space. In some ways I think that more recent Twine games split the difference between Zork and Shelly Jackson: the structural grace of hyperlinks (over the clunkiness of the parsing systems of old-school text-based games) combined with the groundedness of placing a character in a specified, detailed environment.

a new sort of literature

Other developers are using Twine’s structures to tell stories about, and in, space. In 2015, developer Orihaus released To Burn In Memory, an “ahistorical and atemporal Interactive Fiction” set in an unreal European city just before World War I. The architecture of the story is all promenades and mezzanines and arcades, producing a sort of labyrinth of 19th century cultural memory, as if Jorge Luis Borges and Walter Benjamin collaborated on a sequel to Adventure. Memories and time literally intrude on the spatial text of To Burn In Memory in the form of pop up windows featuring diary entries from unseen characters. That Orihaus developed the game without Twine, but still used its hyperlinked structures is a testament to the simple power of Twinescaped literature.

I should say too that not all interactive fiction is like With Those We Love Alive. Some Twine games like Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest (2013) and Anna Anthropy’s Queers In Love At the End of the World (2013) are deeply engaged with temporality, both interminable and minute. A lot of interactive fiction games aren’t developed in Twine, nor do they all use Twine’s link structure. However, I believe that With Those We Love Alive, and its predecessors and successors, opens up new vistas in the formalization of space, and might well be a new sort of literature.

As for me, I’ve got to close up here and get back to work on my new novel. I’m twenty pages deep and things are looking pretty good. What can I say? I’m married to the sea.

Header image: With Those We Love Alive node map via Twine Garden

February 27, 2016

Weekend Reading: The crescent, The Texan, and The True Believer

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Why Is Stan Lee’s Legacy In Question?, Abraham Reisman, Vulture

To the general public, Stan Lee is the Uncle Sam of comic books, a mascot and creator to the biggest portfolio in pop culture. To comic fans and cartoonists, it’s more complicated. Lee’s “Marvel Method” screwed over many who brought these icons to life, and continues to complicate cartoonists trying to make a living to this very day. Abraham Reisman has written a good feature on why so many comic buffs can’t find it in themselves to become “true believers.”

Open Secrets, Amanda Hess, Slate

Nancy Jo Sales is a celeb within celeb culture. Her sharp profiles have meant never underestimating the lessons to be learned from the Hiltons or the teen bandits looting the Hollywood’s most famous. But as for Sales’ new book, American Girls, Amanda Hess finds herself underwhelmed at Sales’ surprisingly 2D takeaway from meeting with 200 American teenagers, and the media’s obsession with framing social media as some kind of secretive puzzlebox.

King of the Hill: The Last Bipartisan TV Comedy, Bert Clere, The Atlantic

Surveys say that America’s liberals and conservatives have equally splintered taste in television, but there was one considerable exception: a muted, animated sitcom about a propane salesman and his family living in the red state o’ Texas. In The Atlantic, Bert Clere breaks down where Mike Judge’s long running show may have struck that middle ground, highlighting a particularly rich episode where Hank Hill takes driving lessons from a black comic.

Straightened-Out Croissants and the Decline of Civilization, Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

We live in uncertain times. Technology is frightening. The climate is ever changing. Politics leave us sick. It is in days like these that we should be thankful Adam Gopnik has come to give us peace of mind on the most important dispute of our generation: croissants that are crescent shaped versus croissants that are not crescent shaped.

///

Header image: Front cover of ‘The Fantastic Four’ No. 49.

February 26, 2016

Null Operator is the videogame that refuses to die

One of the more common pieces of advice given to aspiring writers is to “kill your darlings.” It simply means that writers should be willing to remove passages or ideas from their work that they might personally enjoy in service of the reader. Over the course of developing his game Null Operator, Anton from game development studio Rust Ltd., has killed several darlings.

When it was first announced to the internet as a whole in a blog post in October of 2014, Null Operator was pitched as a game where players fly a spaceship through a cramped, mechanical environment shooting down robot guards along the way while trying to avoid getting caught. Of particular importance was that it was built around full freedom of movement, meaning that the player could move up, down, and side-to-side whenever they wished, as well as hover in one spot for however long they wanted. Among enthusiasts, this is typically referred to as 6DOF, or six-degrees-of-freedom, movement. One of the first games to propose this style of navigation was the 1995 title Descent, which featured fairly standard shootouts for the time, but demanded attention with its multidirectional flying. Not so coincidentally, Descent happened to be one of Anton’s favorite games as a child, and was his greatest influence going into Null Operator.

Describing audience feedback to Null Operator after its first public showing at the Oculus Connect virtual reality festival, Anton wrote “The response was simply incredible, and served to light a fire under my ass to start sharing the project more publicly.” Which is why it was puzzling that after writing that first blog post in the fall of 2014, he fell silent. Expectant readers went for months not hearing from him until he reappeared with a new post in April of 2015, saying that Null Operator was dead (and long live Null Operator).

Brought out of hiding by a Kickstarter for another Descent successor, this one having purchased the Descent name, Anton explained the reason for his absence. He briefly shared his thoughts on the Kickstarter—“FUCKIN’ NOPE”—before ruminating on how his experience playing Descent might have differed from that of this other game’s creators.

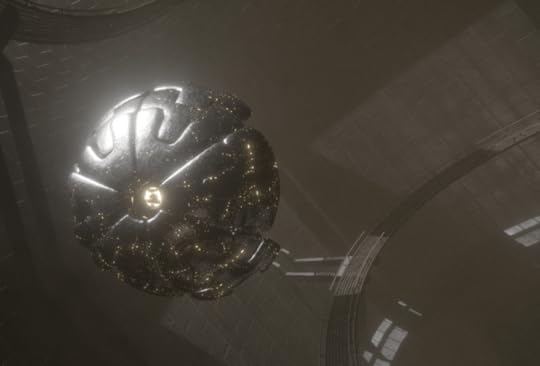

The Kickstarter project, Descent Underground, was presented as a fast-flying experience that was primarily about shooting down computer-controlled robots and player-piloted ships within a 6DOF environment. To Anton, this failed to capitalize on what he loved so much about Descent, and caused him to rethink his entire project. He came to the conclusion that what he enjoyed so much about Descent wasn’t the shooting so much as exploring alien mazes, listening to synth-rock soundtracks from Type 0 Negative and Skinny Puppy, and the thrill of being able to fly wherever, whenever. As he would explain in a later post, “The beauty of a 6DOF game…is that the player has the ability to fly basically anywhere they want, press their face up against any object and see it in all of its detailed glory, from any angle they please.”

Null Operator was dead

So he retooled the game. “I don’t want to make the ‘Descent’ some people seem to want at all,” he wrote. He scrapped the original version of Null Operator, and instead replaced it with a peaceful experience that was less about shooting down robots and more about exploring weird, ethereal ruins from any angle possible, sympathizing with their inhabitants rather than fighting them. He described a scene in which he had placed a large robot from one of his sketchbooks into this new game world. “I didn’t want to fly around shooting it. I wanted to help it,” he said. “I wanted to know why it was here, what it was looking for. I wanted to ask it where everything else had gone.”

This new direction kept Anton motivated through June of 2015, at which point he again mysteriously disappeared. However, earlier this month, on February 12th, he finally posted a new entry on his blog, this time with another change in direction for the game. “The idea of Null Operator I had been working with back in July was as a sort of 6DOF dear-esther-like experience,” he explained. “But…I ran into a giant issue once I scaled the constructed kit to a full (even short) building. It ran like shit.” This technical issue proved to be fatal to the project, as despite multiple attempts to fix it, he could not get the movement system he loved so much to work alongside the spacious, detailed world he had constructed. “So I fell away from the project,” he said. “It straight up died at that point.”

But this didn’t stop his creative work. Anton still had ideas he wanted to play around with, and because “Null Operator has basically been the receptacle of whatever I’ve been passionate about,” he did so within the context of his now-dead project, dabbling with new code for what was left of it. Which eventually lead him to again reconsider his what his goals were with the game.

“It was clearly moving in a direction that I’ve also found myself in,” he explained. “…namely creating something that is visually compelling, rhetorically interesting, likely to [be] fun for others, but something I would likely not find myself actually wanting/needing to play/experience myself.” This was because he felt constrained by the pressures of being a “Captial-A-Artist,” afraid that this sort of selfless approach to design “verges on the only acceptable way to make a game within the institution of ‘Captial-A-Art.’”

He had killed all his darlings, and consequently killed his interest in the project. “While this may be a totally acceptable approach for a film/painting/whathaveyou,” he realized, “I’ve come around more and more that this is really stupid way to make a game.”

As such, Anton has now resurrected Null Operator, but under his own terms. “From here on,” he wrote, “you’ll be seeing a very new and different Null Operator.” Details on this new approach are sparse at the moment, but Anton has promised weekly updates on the project.

You can keep up with Null Operator over on Anton’s blog.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers