Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 159

February 22, 2016

The charming gloom of A Place for the Unwilling takes to Kickstarter

In the Republic, Plato’s characters try to uncover the nature of justice by looking for it not in human beings but in the communities they build together. Since the city is bigger than the individual, Socrates suggests that it might contain justice in larger quantities, making it easier to discover if they search for it there instead.

A Place for the Unwilling takes this project and gives it a Lovecraftian twist. As we reported last December, the designers at AlPixel Games wanted to create a city that might live and die just like the people inside it; a cyclical symbiosis consisting of moments either lovely or sinister, but always intimate.

Now, after months of proto-typing and working on the project part-time, AlPixel Games have taken to Kickstarter in search of funding they say will allow them to focus on completing their vision sooner rather than later. “Without this additional support, we wouldn’t be able to work on A Place for the Unwilling full-time, which means that development would take twice as long and the risk of never finishing it would rise,” they write.

The game takes inspiration from both Majora’s Mask (2000) and Sunless Sea (2015), with plans to keep time always running as players navigate daily rituals that range from reading the morning newspaper to working as a trader who negotiates deals with various merchants. The sum of these interactions portends something more ominous, however. A general sense of alienation permeates the city with one class of citizens toiling away in factories while another attends the theater.

“Nothing is what it seems”

Layered on top of this dynamic is an art style that’s both chalky and vibrant, with muddy blues and fleshy pinks that evoke the whimsical grime of a Bertolt Brecht play. The game’s creators point to more contemporary influences though, citing the “heartbreaking” prints of Alfred Kubin the macabre illustrations of Edward Gorey, among others. They also took inspiration from Patrick McHale’s cartoon series Over the Garden Wall (2013). “One of the things that we loved the most about it was how it introduced adult themes and plots while using a naive and colorful façade,” AlPixel wrote in a recent update. “Nothing is what it seems and nobody is ‘good’ or ‘evil’, we all have two sides.”

The subject of inequality has become such a cultural touchstone in recent years that a dense tome of economic research became a best-seller two years ago, and even games like Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate (2015) have embraced it as a narrative conceit. The simplicity of an adventure puzzle game with an expressive animation style could offer A Place for the Unwilling a novel, less distracted approach to the issue.

You can support A Place for the Unwilling over on Kickstarter.

Far Cry Primal is more gathering, less hunting

“Upgradeable huts.”

“Your game progression can be checked in your personal cave.”

“Gather green leaves. To heal tiger wound.”

These are some of the phrases I’ve encountered in my time with Far Cry Primal, and they encapsulate a fundamental disjunction that seems to define it. On the one hand, this is a serious and gorgeously realized caveman simulator, a playable diorama: a Far Cry in which every club, arrow, and spear must be crafted; in which darkness is a threat that only fire can abate; in which the formation of a rudimentary society feels, from a narrative perspective, like a matter of life and death. On the other hand, it’s another Far Cry game—more broadly, another open-world game that feels like every other open-world game.

You become Rambo all over again

You’re presented with an extensive (and in some ways literally infinite) laundry list of tasks to do. You collect, collect, collect, with the lackadaisical urgency of a white-collar criminal picking up trash on the side of the road. You hunt, which means: following “hunter vision” detective clues exactly like Geralt and Batman; marking your enemies like Big Boss; performing takedowns with the decisive yet hollow click of an accountant closing a spreadsheet. There’s undeniably something satisfying about the Core Gameplay Loop we get here. But it emerges from the world-logic of a time and place unfathomably different from the time and place depicted. Bare necessity, meet market-driven refinement. “Nasty, brutish, and short,” meet “pleasant, relatively easy, and 25-50 hours of playtime.”

This is not, in other words, a game that effectively captures the anxiety of being alone in the unforgiving world, alone as a species. It sort of starts out that way: the darkness is more foreboding, the crafting less abstract. But then, very quickly, you’re amassing supplies and making spear-holster upgrades and spamming the heal button—which, even less plausibly than the typical magic health needle, involves chomping down on an indistinct chunk of meat—in the middle of melee combat. You become Rambo all over again, invincible and fearless, without a whole lot of friction or motivation.

At the same time, Primal makes a weirdly compelling case that it isn’t simply a reskinned Far Cry but a distillation of what the series has always been about. Previous Far Cry games flirted with totemism: fighting under the sign of The Shark or The Spider or The Tiger or The Elephant. This game makes it literal. Previous games nudged players in the direction of silent, bow-based predation, even as they retained a Call of Duty-grade arsenal. In this game, the bow is basically your only long-range weapon, and solid bowfeel was clearly a development priority. Previous games did everything they could to make hunting animals feel worthwhile and important, inexplicably making holsters and containers obtainable only via skinning creatures in a place otherwise littered with vending machines that could sell you a flamethrower. This game doesn’t need to make hunting feel important. In Far Cry Primal, you stumble into a jungle where the idea of Far Cry makes sense.

There is something primal about Far Cry Primal

In other words, there’s no mismatch between prehistory and the idea of Far Cry; there’s a lot, however, between prehistory and what it’s like to play Far Cry, and it’s a mismatch precisely between the game’s narrative of zero-sum survival and its accumulative, productivity-suite rhythm. In some ways it feels like a classic case of “ludonarrative dissonance.” But I think it’s more a case of dissonance between the unstoppable, constantly iterating ur-structure of open-world design—that creature of consensus that seems to refine itself and grow new features every time a new blockbuster videogame comes out—and the particularities of any historical period, prehistory included.

There is something primal about Far Cry Primal, but it resides not so much in the game as in what the game targets: whatever dopamine receptor gets hit, whatever basic need gets fulfilled, by the performance of tasks that are challenging but not too challenging; exciting but not too exciting; a little different but still routine. I have many mammoths and cannibals left to kill, and things may change. For now, I wonder why I feel so compelled—deeply, subcortically, primordially compelled—to kill them.

February 19, 2016

Weekend Reading: Ryerson, Tigers, and Bears

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there is an endless supply of articles about games, technology, and art around the web that is worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Taming the Inexplicable, Liz Ryerson, The New Inquiry

You have probably read a fair bit about Jonathan Blow’s The Witness at this point. While you may hesitate to dive into another breakdown, Liz Ryerson’s deconstruction of all frustrations and ambiguities with the puzzle game, its waxy philosophies, and its creator is worth reading. I swear. Just one more thing. Just read one more thing about The Witness. For now.

The Secret Lives of Tumblr Teens, Elspeth Reeve, New Republic

A massive feature that will be shocking to anyone over 23, Elspeth Reeve visits some of the teens who created their own highly profitable empires right under their parents’ nose on one of the most unwieldy social media networks there is. Tumblr has apparently turned handfuls of kids into masterful social engineers, with certain parts of this piece reading like a Moneyball of memes.

Puke Force and the Power of Satire, Anya Davidson, The Comics Journal

One of the two Brians of Lightning Bolt, Brian Chippendale, is releasing his first new graphic novel in a number of years, a collection of scenes amid chaos called Puke Force. While the ideal way to read Puke Force is having Chippendale explain all the gizmos and cameos strewn page by page to you like a six-year-old showing their parents a drawing, Anya Davidson’s exploration of Chippendale’s style of satire is a close second.

The Man Who Made the Whac-a-Mole Has One More Chance, Peter Rugg, Popular Mechanics

Verging on too-good-to-be-true, a story of deception, desperation, and singing robot bears. Peter Rugg visits the dream factory of Aaron Fechter, the man who claims he invented Whac-a-Mole—the only reason 60 percent of us have ever held a mallet—and how he was swindled out of the glory by a carny so devious he could have driven in The Wacky Races. Worth reading alone for a description of the amazing inferno the The Rock-afire Explosion storage became when it, uh, exploded.

One-Trick Tiger, Michael LaPointe, The Walrus

Yann Martel is one of Canada’s best-selling authors, so why is it that he’s only got one massive hit to his name? Well, as Michael LaPointe explains, it’s likely because he constantly returns to the same sort of paradigm that works for Life of Pi but fails for a number of other subject matters. A good piece of criticism and an even better excuse for the pun we made as the headline for this roundup!

Play through Italian trauma in these fables of fascism from WWII

A fable is put together like a joke: the punchline—the clever inversion we expect at the end—is set up with a story, sometimes just a framework distilled into the simplest form of itself. The hare oversleeps and the tortoise wins, and while we may have details about the hare’s braggadocio, these animals lack names or histories or lives outside the fable. These things aren’t important for the punchy moment the ending gives us, or for the moral we get to keep afterwards. And the purity and simplicity of the fable are what allow it to permeate our culture so completely that a seemingly lethargic presidential candidate can hand out toy turtles and say, “Slow and steady,” and everyone knows what he means.

Venti Mesi (Twenty Months) is new game from We Are Müesli that takes the form of a collection of twenty short (sometimes very short) stories that play out in the greater metropolitan area surrounding Milan as day-to-day life becomes more severe under fascism near the end of World War II. The length of the stories and their brisk pace make them easy to distill—the characters have names, but what remains with the player is “the one about the smuggler who, racked with guilt over the starvation in his community, kills himself” or “the one about the child who sees bombs and mistakes them for beautiful night-lights.”

The Holocaust, World War II, and the associated rise of fascism had such a profound effect on the international community that we’re still understanding and re-contextualizing it today. In the United States, this tends to lead to Hollywood films about Americans in conflict—Fury (2014), Unbroken (2014), The Monuments Men (2014)—it means Nazis on the History Channel 24/7, and it means opinion pieces that point out how Donald Trump’s rhetoric resembles Hitler’s. In Europe, and especially in France and Italy, the wider narrative becomes one about surviving fascist occupation, and the smaller stories that contribute to that narrative are visible on a daily basis: there’s a cemetery in the city, or houses that were bombed and never rebuilt, or a plaque that marks where the Jewish school was before the war.

too many terrible things happen too quickly

Louis Malle’s 1987 film Au revoir les enfants centers around the boarding school life of a young boy who stands in for Malle himself. He befriends a Jewish student protected by the priests who run the institution, and at the end of the film, the Nazis arrive and lead Père Jean away through a crowd of horrified schoolboys. The priest turns back to them and says “au revoir, les enfants” and his “until I see you again” as opposed to a definitive “goodbye” is perhaps a message of hope, even as this sanctuary has been penetrated by violent invading forces. The moment is powerful—it’s the moment you tell your friends about, it’s where the movie gets its title—but it’s part of a whole movie that describes the personalities, relationships, and experiences of the schoolboys. When those 45 seconds of film are taken out of context, they can easily become fable. The story can lose its personal power and become generalized. Aleida Assman writes in Cultural Memory and Western Civilization that “What for the writer is the most terrible experience becomes merely one episode among many for the reader. …[W]ords… draw a veil of generalization and trivialization over the unique and the profound…” It is different to watch Au revoir les enfants (and then Roma, Citta Aperta (1945), and then L’armée des ombres (1969), and then, and then…) than to have been Louis Malle in January of 1944.

For Venti Mesi, this means that even though the game tells me that these stories are pulled from real life, the way that every moment of them has to be so forceful and communicate so much trauma prevents them from feeling true or real—I’m introduced to too many characters to whom too many terrible things happen too quickly. In fable IX (which begins with one of the game’s beautifully-read voice-over epigraphs, this one on Gunfire) a woman looks at a pile of bodies, men murdered by the fascists, and hunts through a long list of the dead for her brother. After reading each name, she says “No… he’s not my brother… but it’s as if he were,” and when prompted with one name in particular, she says “If he was there, I’m sure my brother was too…”

Venti Mesi is part of a project celebrating April 25th, Italy’s Liberation Day in Sesto San Giovanni, a suburb of Milan that Wikipedia says was sometimes called the “Stalingrad of Italy” because of the local influence of the communist party and their resistance to fascism during WWII. It was nominated at the Emotional Games Awards for “Most Emotional Indie Game.” It was released in English on January 27th, Holocaust Rememberence Day, and it is available for free on Mac and PC over on itch.io.

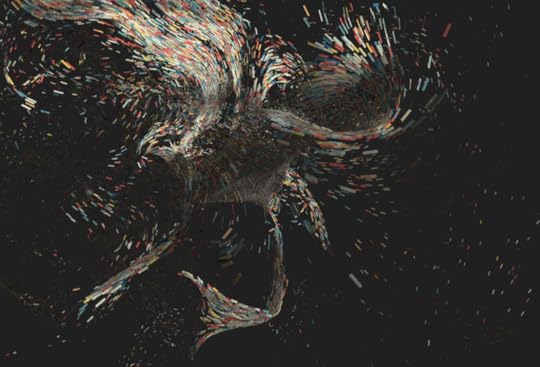

Polygon Shredder is all the fun of confetti with none of the mess

As I tool around with the cascading confetti waves of web developer Jaume Sanchez Elias’ Polygon Shredder, I feel a bit like Moses parting the red sea. Except this sea isn’t just red, but also blue, yellow, white, and I think I saw a little chartreuse in there.

If you ever had a pet tornado in the ‘90s, Polygon Shredder follows a similar principle. As a sort of desk toy for the digital age, Polygon Shredder works by generating a certain amount of multicolor cubes based on your preference, then shredding them into paper-thin strips and tossing them into the virtual wind. It’s a fully customizable experience, setting the confetti to follow your mouse as you move it about and allowing you to adjust anything from the thickness of the strips to how much they rotate to whether or not they pulsate.

It’s stunning just how different these slight permutations of the same experience can be. Set the number of confetti strips generated to “almost none” or “a few,” and they’ll move around like leaves in the wind, almost as if a tornado smashed through a Party City. But change that output to “quite a few” or “a lot,” and the confetti behaves more like a wave, one unified force crashing against itself as it moves to your whims. It’s an odd combination of serenity and power, capturing both the meditative calm of staring out at the ocean, while also giving the user the rush of controlling that ocean.

art that wouldn’t be possible without a computer

As it stands, I’ve only used Polygon Shredder with either a trackpad or a mouse, but I’d recommend loading it up on a tablet if you can. I enjoy the sense of control I get with my cursor well enough, but I have a feeling using my finger would be all the more satisfying, as if I were actually tossing the confetti into the air myself.

Elias’ site is filled with similar projects, including a cloud generator and a lava lamp application coyly titled Bumpy Meatballs. Most are tailored around user-manipulated objects and playing with physics, while at the same time featuring abstract spaces that would be impossible to recreate in the real world. As art that wouldn’t be possible without a computer, Elias’ projects are a great example of the types of boundaries only interactive works can break.

You can check out Elias’ full library of work over at Click to Release, and you can find the source code for his projects on his GitHub.

A people’s history of PlayStation Home

Released at the end of last year, Postcards from Home has the feel of a curio: a weighty tome assembled exclusively from images captured within Sony’s discontinued virtual world, Home (2008-2015). Its author, the Spanish photographer Roc Herms, has explored games before, whether making absurdist use of the Game Boy camera or documenting an enormous LAN party from the perspective of the hardware. But it only takes a few pages for the scope of Postcards from Home to reveal itself as something much more empathetic, even human, full of penetrating longform interviews that explores the digital architecture of Home as well as the emotional lives of the people filling it. The result is something like embedded reporting within a virtual world, assembled into a frequently moving graphic novel that doubles as a people’s history of a dying world.

Perhaps befitting of an exploration of digital space, Postcards from Home is a playful physical object, riffing on paperstocks and page layouts, and the imperfections of an in-game camera. In one passage on the afterlife, Herms utilizes a soft, transparent paperstock, making each frame fade into the next; later, an honest-to-god centerfold flips out of the book. I spoke with Herms from his home in Barcelona about the years-long process of constructing the book, as well as transhumanism, Facebook, and his infiltration of the cult-like Homelings.

Kill Screen: Let’s talk about how you started the book. Which came first: You getting into PlayStation Home or you starting the book?

Roc Herms: The book is quite autobiographical. In the beginning of the book, there’s a history between me and Alex, my best friend. His nickname is aBeBoy. He was living in Barcelona, but then there was one winter where he got a girlfriend in Madrid and he went to live in Madrid. On weekends, we spent many hours with me on my sofa and him on his sofa with headsets and microphones playing Call of Duty, playing Minecraft (2011). [We stayed] together inside different kinds of virtual worlds and online games. Not just playing, but talking about, “How was your week, your day?” etc.

At some point, more or less at the time, I realized that all those 3D environments—where I have control of the movement of the character and the point of view—[provided the two variables] I needed to be able to work as a photographer. You can move around, you can look, and then whenever you want, you can take a screenshot and capture what you’re seeing. I [did go online] on New Year’s Eve, we made a dinner [inside] Home, and I realized that there were many people celebrating with New Year’s Eve displays. And it was like “Woah, that’s not a game, there’s people doing important things for them [in here].” I thought: “Now I may as well try to document the lives of those people that are standing inside this place.” That was the beginning.

KS: What year was this New Year’s Eve experience?

RH: 2010. 2009 to 2010. At the beginning, I was just walking around and taking pictures. And then one day I realized that in this place, when people talk, you don’t hear the conversations because that will be so messy in a public environment. But conversations are displayed at the top, and I was holding in my hands the only camera able to capture those conversations. I could be in a place and I could not just be looking, but seeing what people were saying. Maybe the most important thing for me was finding the pictures of what people were saying to each other.

KS: How did people respond in interview?

RH: In the beginning it was like “Can I take your picture?” and many people said no. Then there was one of them that said, “Yes, okay” and then I took a picture. I was telling them that I was a photographer in real life—well, now I don’t like to use that word, “real,” because maybe [it would make too much of a] distinction between physical and digital. I did learn that both of them are “real” in a way. Things happen in [PlayStation Home], relationships can be “real” in [its virtual] streets [as they are] in a physical environment.

KS: What’s the big difference between using a traditional physical camera and the one inside PlayStation Home?

RH: I got into photography quite late, when digital cameras arrived and almost everyone became a photographer. In the beginning, I was using it as an excuse to travel with my parents—I left them at the hotel. But little by little, I started to use photography to learn about histories or make small projects to go with my work. And I focus on subjects that interested me before photography. I grew up with a Game Boy and Super Nintendo, making LAN parties with my friends. I always related to videogames and computer technology.

I have another book that [physically looks] like a laptop. I’ve been documenting a huge LAN party in Spain, something around 8,000 people are connected for a week, and they spent a full week inside this place. The idea is to travel from the black to the inside of the computer. The idea that the black is where it starts in a way, and then closer to the screen it’s like collecting all the desktops of the people that were there. That was the first project. That ran for five years.

KS: You spent five years on that book and then five years on this one?

RH: Same time, or less. Five to six. When I realized that I was making this book of interviews, when [it came to putting] them on paper, I thought I could use a comic book or graphic novel style. In graphic novels, you go, you write, and then you mix it. And here, the words and the graphics come at the same time. Graphic novels in a sense are always fiction. And this is like, the same. [It was right in that] moment of time and space, and there was a lot of work on design, putting things on the pages.

KS: One thing that sticks out in Postcards from Home is how you spent a long time talking to a person’s avatar, and then sort of shockingly cut to an image of the person from the real world. How did those moments come about?

RH: I often thought of how much to include the physical reality. Actually, there’s this chapter of [a user named] Joanna Dark where she loves fashion and she wears all different stuff. For that, I thought “oh, maybe I can go to United States, and [try to portray her] with all the clothes that she has in the physical world.”

In the end, it was like, maybe I don’t need to include their physical lives. I think the first one is all grainy from Hawaii. There’s a [very old] picture of a [young woman], after I’ve shown all her avatars. One time I asked if I could have a picture of her, and she sent me this old picture, telling me that if I want to see one picture of her, she would like to show [her younger self]. But, right now, maybe she doesn’t feel comfortable with her physical appearance. [She talked] about identity and how in these places you feel detached from your physical body.

KS: The next real-world picture is of you, on vacation, when PlayStation Network was shut down.

RH: Yeah, like four years ago, the servers were down for like 52 days. At the time there was a disconnection. But the idea of my built wall was shut down, because the servers were down. So it’s time to go into the physical world and enjoy some sun and mojitos, etc.

KS: Toward the end you infiltrate a group called the Homelings. It has an ideology, a uniform, and even a leader named Mother. They say they’re not a cult, but they do admit that they look a lot like a cult. And then you show a real-world picture of Mother, who is a member of the US military. Did you talk to her in-game?

RH: I talked to Mother in a chat on the forums they have outside of Playstation Home. But she was on duty—I’m not sure exactly where—and I could not interview her properly. But I did talk a lot with her that in a way was like Jesus Christ. Like, there’s God and there’s Jesus Christ, everyday they’re just organizing a lot of stuff. But no, no I could not talk to Mother much.

KS: What drew you to the intersection between the digital and physical worlds?

RH: It’s the interest to learn. I can play online games for a long time, but they will always be games. They’ll be quick, running and shouting from one to another. Maybe I did not realize before this project, that when we were inside Quake (1996), that we would actually be living inside Quake. We would be sitting in front of the screen, but my mind was inside that wall, and we were being chased. You could be scared, you could be happy. I connected to Second Life (2003) when it was on top, but I did not make it anywhere there, and I did not understand what people were doing in there.

I think also that maybe while writing the book, with almost everything having happened inside of Home, it made me think of virtual worlds in general. I was thinking about where this kind of stuff can go in, I dunno, 20 or 50 years. And I think, in the end, everything is in the hands of the program. In Playstation Home, for example, it’s for all ages, and you will not see naked [bodies] or sex, as it’s deleted. But afterwards, I checked and there are some virtual worlds that have sex—I mean, during the process I did study [a few of the other] virtual worlds. And it also made me read about science, and how maybe one day you will be able to disconnect your physical senses and connect to digital ones. Maybe we will be able to connect and disconnect from the digital and physical. Then the next step is maybe trying to reach a point where intelligence will be restored like human life. Maybe we will be able to live inside one of those kind of environments.

I did learn that both of them are “real” in a way

KS: What did you do when Home closed? I guess was it about a year ago.

RH: Yes, more or less, one year ago.

KS: What were you doing?

RH: I was in the process of designing the book, and from the beginning I knew that Home was gonna die some day. I was lucky for it to be exactly when the book was finished, because I think it’s a nice ending for the book. But in the beginning, I knew that those lifespan of those environments was very short, because technology advances at such an incredible rate and speed. When the PlayStation 4 came out, all the people in Home went away, so they decided to close it. So when Home died, I was in the process of doing the book and it was like, “Okay, now I have a proper ending.” The last page of the book is the last frame of one of the last parties that were being held inside the world before the pop-up message that said, “Unable to connect to the server.”

KS: What were you doing specifically when it happened?

RH: Actually, I had a very long day. And after all those years of going inside and after knowing that that was an important day, that maybe I could have stayed there in the party, and make another short chapter from it, I did not connect that day. Because I had traveled with my girlfriend and I already knew that there would be many people recalling this event. And I thought to explain it in the book I could use the people who there to actually show it.

I think inside Home itself, I didn’t really make any friends, [not] any real friends, [no] personal attachments with which to connect. I would go inside to work and learn, but I wasn’t connecting in Home that matched. Actually, I think that Playstation Home was not the most interesting virtual world of recent times. There are others that are more interesting. But this one gave me all the tools I needed to work as a photographer. This single thing about seeing what people were saying in such a graphical and direct form, was much better than what was offered in Second Life.

KS: What other virtual worlds do you think are more interesting than Home? Are you involved with any of them?

RH: I think the next step is Facebook. Maybe it’s not a 3D environment where you can build your house and buy a nice sofa, etc. But it’s a digital environment where all of us are living a huge part of our lives. It’s a place where I can work, where I can meet people. I think that social networks, in a way, are like an escalation of those online 3D worlds.

In Spain, today, we spend about seven and a half hours in front of a computer—for me it’s more, of course, and for my mother less, I guess. But I think that when we stay in front of the computer, we are inside the computer. We still have to connect. When I’m sitting here, I can be working, I can be talking to someone. And I think everything is going on inside this 2D environment on the screen. I think that everyone is spending a lot of time of their life already working, socializing, or living inside the Internet or this digital world. Other examples could be Minecraft, or World of Warcraft (2005), or Eve Online (2003).

KS: Something you get at in the book is that Home was like a big shopping mall. A consistent part of the experience was consuming stuff. How did that strike you as a space to live in? When I’m in a shopping mall, after a while I start feeling claustrophobic, I wanna get out. What did it feel like to live there?

RH: At the beginning, after New Year’s Eve, and after working around there a bit, I thought it was quite difficult to find someone to do something interesting, because it’s more focused on shopping. But afterwards I discovered that, even with those restrictions, I found two proper people in this place. One of those is the guy who writes for a magazine and spends four hours a day inside Home, socializing with his friends, but then spends another four hours writing for a magazine that talks about this environment. In a way, it’s almost like living inside this place, because his work and his friends are in this place.

But maybe one thing is that with Second Life, for example, you have to access it through your computer. And maybe the people who were into that were more nerdy or geeky [than the console players of PlayStation Home]. I think Sony sold around 50 million units [of the PlayStation 3] worldwide or something. Maybe many people that didn’t know anything about these types of virtual worlds had found Home by accident, because it was already connected on the console. Like the grandma from Hawaii, for example, she told me that she never knew about any of this, and her grandson was playing one day and she found it by accident. Maybe it opened up this environment to people who didn’t know anything about it before.

KS: So you found that people’s naivety counteracted the commercialized nature of the space?

RH: Even being in a place more focused on shopping, they wanted to try you to do this stuff. [But] they did not give you as many tools as other places, where you can construct things, you can build things; it was a limited space. But as I write in the book, people saw through the restrictions and managed to construct things of their own. They found their own way to enjoy the place.

KS: Yeah, the Homelings were a very interesting example of that. They created a culture around specific things that you can consume, like having an outfit you were supposed to wear.

RH: The beginning of the Homelings, Mother joined when the beta was out, when there was only the one stage—it was the bowling alley. At the bowling alley there was this machine, that if you beat the game they give you this outfit, and then you have to beat the machine to dress like them. The idea of the Homelings was more or less this one. [Despite being located] in just one stage, they managed to construct a group of people, or friends, of more than one thousand. And they had their own rules and their own culture.

people saw through the restrictions and managed to construct things of their own

KS: What are you working now that Home is gone?

RH: After a long travel inside the digital world, I got a big motorcycle, and I’m now leaving my apartment in Barcelona. From Barcelona I’m going to the Middle East, and then I don’t know where we’ll end up going. My plan right now is to get away from keyboards for some time and watch the mountains.

I’m pretty sure that if I end up in Kazakhstan, or some kind of away-from-keyboard country, that I will still have my eyes on how the people there relate with technology. Maybe there will be some projects for me to [pursue] there that talks a little bit about the use of technology in another environment. I will not make a project about the flowers of Kazakhstan, I’m pretty sure.

Design your dilapidated fantasy home in Shabby Home Designer

One of my most played games of last year was the simple and charming Animal Crossing: Happy Home Designer, a game in which you designed houses according to the fancies of cutesy animal citizens. Happy Home Designer was released to a wash of lukewarm reviews, nearly all resounding with the common criticism of the game befalling no risk or reward. I agreed with these grievances, but somehow still found myself coming back to it night after night for a few months. Happy Home Designer became my nightly relaxing retreat from reality. In game developer Todd Luke’s recent Flash game, Shabby Home Designer, the serenity of designing a living space is replicated. Except in this instance, it’s really anything from happy.

Nothing looks straight out of an Ikea catalogue

Shabby Home Designer is a barren Flash game. The game was created “over the course of a few days,” according to the game’s description page, with most of its assets nabbed from Google Images and YouTube. The player cycles through furniture to place in their home and has the option to flip through additional options, such as a giant flan for a stool. The player can also color coordinate and draw tile that’s repeated for the floor and ceiling, similar to the patterns that can be easily created in Animal Crossing.

The thing that differs is that everything is, well, shabby. Nothing looks straight out of an Ikea catalogue, perhaps least of all your low-poly “friends” that you can place throughout the room. The rooms the player creates can take any rickety turn: be neatly organized but bland, or bustling with overflowing garbage and bugs. Shabby Home Designer gives the player full reign over creating their own dilapidated fantasies. It’s the Happy Home Designer for the browser-bound, obscure Google Image-savvy fan.

Flash games aren’t a new venture for Luke, with plenty of other like-minded, oddball browser games under his belt. Included in the breadth of other Flash games are Entomo, a game about exploring the base of a tree as a rolling orange ball afraid of bugs, and Space is Red, a bite-sized sci-fi game that oozes with cyberpunk coolness (thanks in part to its dope music). Luke is a prolific game developer, and his itch.io demonstrates the risks continues to take, and Shabby Home Designer is not lost among them.

Play Shabby Home Designer here in your browser and design derelict rooms to your heart’s extent.

Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel, a cartoon jab into the past

There can be a fascinating tension in watching old cartoons—we’re talking pre mid-20th century here—it lies somewhere between the familiar and the absolutely unexpected. In early appearances, for example, Daffy Duck showed no signs of the devious but hapless narcissist struggling with his peers for the spotlight that we now know. Instead, Daffy is almost a pure agent of chaos; a mad mallard with a trademark HOO-HOO, HOO-HOO bouncing laugh that accompanies his most successful violations of the laws of physics and common sense. Bugs Bunny might be initially less jarring in terms of personality—he’s a bit more willing to instigate trouble rather than retaliate, perhaps—but his appearance bears little resemblance to the tall, puffy-cheeked gray hare that we’re used to seeing plugging a carrot into the barrel of Elmer Fudd’s shotgun. He’s shorter, more bottom-heavy, and his head is almost a simple tilted oval.

As unfamiliar as these early versions of Warner Bros. characters may be, at least most of their appearances were in color. Tracing Disney characters back to their earliest versions, on the other hand, requires entering an entirely different world. In this world, movement is frequently repetitive and halting, as if every living thing were an automaton, and yet at times the screen is filled with massed activity in ways that color animation rarely tried to match. It is this black-and-white world that Red Little House Studios’s upcoming game Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel seeks to revisit.

Red Little House Studios, who are based in Valencia, Spain, describe Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel as a graphic adventure/action adventure game set in the 1930s, “the sunset of the black and white era.” When Fleish the Fox is kidnapped by his nemesis, Mr. Mallow, Cherry has to navigate a world of cartoon characters and animated obstacles in order to rescue him. This is, of course, a twist you might not expect to see very often in an old black-and-white cartoon. “The shorts from the 1930s overuse the damsel in distress theme,” says Red Little House’s Iván López, “with Olive Oyl and Minnie being kidnapped and Popeye or Mickey Mouse having to save them. We found that reversing the trope gave us a very interesting story.”

It’s the sort of tribute—sincere, but with a bit of a jab—that one might expect to see in a cartoon where Bugs Bunny finds himself in a nightclub populated with Hollywood caricatures—the 1947 Merrie Melodies Slick Hare, specifically. In other words, it might be just the right mixture of fidelity and irreverence for a medium dependent on establishing its own peculiar laws of reality (see: Cartoon physics), and abandoning those very rules whenever it makes for a good joke. Consider, for example, the rabbit at the center of another tribute to a bygone era of animation, the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. In the second act, Roger, wrongfully accused of the murder of novelty magnate and his wife’s apparent lover, Marvin Acme, finds himself in a secret rotgut room leftover from Prohibition handcuffed to clown college alum and private investigator Eddie Valiant. As Valiant tries to cut through the cuffs with a hacksaw on top of an old, rickety crate, Valiant yells at Roger to hold still, and Roger tries to make himself useful by quietly removing his arm from the handcuffs and using both his hands to steady the crate. Valiant, incredulous, stops sawing.

“Do you mean to tell me you could have taken your hand out of that cuff at any time?” barks Valiant.

Then comes Roger’s telling reply: “No, not at any time. Only when it was funny.”

Like Toontown in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel looks to build its storytelling on a gesture of pulling back the curtain on a showbiz world. Writers Paula Ruiz and David Martínez describe Crazy Hotel as an attempt to explore what happens after the end of a classic cartoon. “Storywise,” they say, “our game is like visiting the backstage from the cartoon shorts.” In contrast to Roger Rabbit’s toon showbiz, what happens “onscreen” to Fleish and Cherry is part of their lives, but their lives don’t end when the camera stops, and onscreen events have offscreen consequences.

If this sounds more like a take on classic cartoons as reality TV rather than the old Hollywood studio system, then it might be the contemporary jab within the period sincerity. “What we want is the game to recall that age,” says illustrator and character designer Raquel Barros, “but without losing our own identity. You can say we are trying to be a 1930s animation studio placed within our time.” And like Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, the most intriguing potential within a project like Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel is the creation of an alternate version of the era from which it takes inspiration.

what is a cartoon for if not breaking the rules?

There is, after all, a stark juxtaposition between the golden age of black-and-white animation and the historical events of the 1930s. In 1928, Disney’s Steamboat Willie was the first cartoon with a fully synchronized on-film soundtrack. In 1929, the crash of the American stock market initiated an international economic depression. In 1930, Betty Boop made her first appearance. The Flowers and the Trees, a Disney Silly Symphony, was the first Technicolor animated cartoon in 1932. In 1933 Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany, declared Führer in 1934. By 1936, Spain was embroiled in civil war, and Germany invaded Poland in 1939. None of this factors directly into Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel, except that for a Spanish developer to create a game as a black-and-white cartoon from the 1930s—a period when a great deal of foreign media was banned—is a striking act of historical reimagination.

It is important to know the way that things were, and it is important to know that they could have been different. And what is a cartoon for if not breaking the rules? Animation, like all media, is and must be a product of its time. But if all media is bound on some level to the world that created it, cartoons can often seem to have their own escape velocity. As Red Little House Studios puts it, even in the 1930s, a toon has easy ways to reach outer space.

Pinstripe, a fanciful trip through a father’s worst nightmare

Teddy isn’t looking so good. Stood in the freezing cold of Hell, his shawl visibly shivering, a crescent of stubble clings to his jaw and chin. This ex-minister is in search of his daughter, Bo, who has been kidnapped by a “strange entity” that claims to be God. Whether he asked for it not, it seems Teddy’s faith is being thoroughly put to the test—his responsibility as a father even more so.

This is a snapshot from the upcoming 2D adventure game Pinstripe. Thomas Brush has been slapping paints and computer code all over it for the past four years, intermittently between freelancing and home life. Now, at last, he’s put it up on Kickstarter, where it blitzed past its base funding goal of $28,000 in a small number of hours. This means he’ll be able to concentrate on finishing Pinstripe over the next few months, put a beta build together, and then get it released on Steam for PC this summer. Slap, bang, wallop.

Over the years, Pinstripe has evolved from something Tim Burton would probably cough up onto a reel of celluloid to, well, a gruffer version of that. Teddy has always had those inch-thin Jack Skellington legs, but now he has distressed-dad facial hair and religious attire. The blobbier art of the game’s earlier days has transformed too, becoming more stringent, Expressionist—exaggerated straight lines and harsh angles (one tree’s branch is literally a right angle). What this suggests is that, over time, Pinstripe has become more harrowing, harrowing, harrowing! This rings true: Pinstripe used to be about a dead man searching for his wife, now its plot is more desperate and looks to test Teddy’s will that much more.

In adapting to his new dadcore makeover Teddy has also gained a shotgun and a puppy called George. The former deals with the screeching monsters and also acts as a rather blunt puzzle-solving instrument. There are other puzzles that take more traditional formats, such as ticking clocks, which presumably have less violent solutions. Or maybe that’s a false assumption. Perhaps Teddy hates clocks. Imagine it now: Him facing a wall-mounted clock, a stern expression on his face. “Fuck clocks” he shouts. Then blows a giant hole into the wall with an almighty bang, afterwards panting heavy with the anger. Teddy’s got it rough, I’m telling you.

another aspect worth latching your feelers around is the music

As to the puppy, you’ll be pleased to find out that it hasn’t got a violent streak in it at all. Instead, it helps Teddy to find clues that will reveal more about his past. Oh yes, he is in Hell, remember? How he got there is rather slyly omitted in all of the text that describes the game and tells us what it’s about. But it could be that he’s dead. In any case, there is presumably a reason for why Teddy is now an ex-minister, which is surely a ripe topic to dive into between stroking George and kicking the shit out of clocks.

As well as the art and the themes of Pinstripe, another aspect worth latching your feelers around is the music, especially as Brush has won awards for his sound work in his previous games, Coma (2010) and Skinny (2011). For Pinstripe, it seems he’s going for a mysterious ambient sound pinched together with classical piano and medieval instruments. It’s a work-in-progress still but you can float your ears over to Soundcloud for an early impression.

Currently, Pinstripe is steaming towards its set of stretch goals, which includes an extended level in heaven (already reached), an Adventure+ mode that has new discoveries after the first playthrough, full voice acting for the odd characters you’ll meet, and a mobile version of the game.

You can support Pinstripe over on Kickstarter.

Author in the machine: An XCOM 2 Review

Vigilo Confido goes the motto of the titular fighting force in Firaxis Studio’s excellent XCOM 2. To any English speaker, even one without any specialized knowledge of Latin, the meaning of the motto appears self-evident. Vigilo—vigil, vigilance, or something to that effect—and confido—obviously, confidence. Or . . . wait, is it confidential? In fact, the Latin is intensely and conspicuously ambiguous. Depending on whether or not those final “o”’s are read as nonal case endings or verb conjugations (to say nothing of the tense), defensible translations of Vigilo Confido include everything from “I Am Watchful; I Am Relied Upon” to “Trust the Vigilant.” The vagueness isn’t necessarily bad; either interpretation is a respectable, lore-friendly motto. So rather than nitpick XCOM’s apparent fondness for kinky Latin syntax, why not wonder what it means for a slogan to set up a limited, but evocative, interpretive horizon, rather than the calcifying closure of “meaning.”

There are any number of reasons to praise XCOM 2, although the game is better understood as a theme and variation on its already-fantastic predecessor, 2012’s XCOM: Enemy Unknown (to wit, both are clearly built in the same engine, including some of Enemy Unknown’s more recrudescent visual bugs). Still present is the superb tactical simulator that made Enemy Unknown so fulfilling, enhanced by the more frequent use of timed missions—one of Enemy Unknown’s few faults was that it was sometimes too plodding and methodical for its own good—and a balance overhaul that gives each of the game’s eight classes a more distinct sense of strategic purpose. Technical improvements abound; textures have been sharpened, animations made more fluid, and environments more destructible. Those interested in representation will be happy to learn that XCOM 2, like its predecessor, effortlessly captures the immense diversity of the human world, which underscores the game’s premise of a united human response to an existential threat. In short, XCOM 2 does everything we expect a sequel to do, and well.

But XCOM 2’s most interesting adjustment of the series’ winning formula might be in its approach to the ambient storytelling that imbued Enemy Unknown with such a sense of life. This isn’t to say that XCOM 2 has dispensed with every cliché in the alien invasion playbook; if anything, the game doesn’t fall back on well-worn conventions so much as it gleefully leans into them. The contours of the story are deliberately archetypical: despite the events of Enemy Unknown, the aliens have occupied Earth, placating its citizens with promises of panaceas and global harmony. But, of course, they’re secretly up to no good (slavery, cloning, genocide, etc.) and it’s left to a long-dormant XCOM to gather allies and rise against two decades of extraterrestrial rule. Familiar platitudes cycle though, one after another: a mechanical savant returns to finish her father’s work and alien architecture enters its fascist chic phase, black and red with no curved lines. It’s all very campy, and intentionally so: a talented voice cast deliver line after line with a self-seriousness normally reserved for Dalton-era Bond villains.

But what of it? For years, scholars of games have futzed over the tension between the designers’ intentions and the meanings players inevitably produce in the act of play. Scripted narratives, no matter how well-crafted, are inevitably in competition with those imagined by the player. This debate has a long pre-history in literary theory (see Umberto Eco’s 1962 book The Open Work and Roland Barthes’ 1967 essay, “The Death of the Author”), but is felt with particular acuity in videogames. Simulation tends to produce what game theorists call “emergence,” the unexpected results of the interplay of semi-autonomous elements within a game’s algorithms. The more intricate the simulation, the more difficult it becomes for designers to exert authorial control. This isn’t necessarily bad, but it does point to one of the challenges designers face when attempting to communicate specific meanings to the player. In her talk at GDC 2015, Mitu Khandaker-Kokoris discussed the trade off designers face on a spectrum that stretches between “emergence” and “emotional nuance.” Autonomous behavior might yield wonderful, unexpected outcomes, but it comes at the cost of subtle, authored encounters that only a human touch can create (think The Sims vs. The Walking Dead). Crucially, she argues that neither is inherently more valuable than the other, but that each lends itself to particular kinds of storytelling, and designers would do well to consider whether their intention or their players’ interpretations fit with their creations’ goals.

Scripted narratives are inevitably in competition with those imagined by the player

Enemy Unknown and XCOM 2 attempt, in their own ways, to cleave a path between the two poles of Khandaker-Kokoris’ spectrum. Despite the authored narrative that anchors the progression of each game, both titles tend towards emergence though through their ambient storytelling. Yet XCOM 2 is significantly less emergent than its predecessor. Consider that one of Enemy Unknown’s most loved signature flourishes was the randomly assigned nicknames for experienced squaddies. Upon promotion to the rank of sergeant, each soldier received a nom de guerre from a pool of suggestive titles—Junkyard, All-In, Lockdown, etc. Even so, Enemy Unknown patently refused to reveal what its soldiers did to deserve these sobriquets, even if an obvious connection occasionally presented itself (one particularly agile sniper was called “Spider”). The effect of this randomness was twofold: it implied the existence of soldiers’ subjective lives beyond the tactical functionalism privileged by XCOM’s player-commander, but it also invited the player to imagine how these nicknames came about, that is, emerged. Though, I’ll admit I stopped short of picturing why one of my best grenadiers earned the title “Septic”.

In XCOM 2, though, the distribution of nicknames seems a lot less random. Over the course of the campaign, it became clear that the majority of assigned noms du guerre were based on and referred to a character’s class: my most lethal Sniper was named “Bolt,” my finest combat hacker, “Tinker,” my best medic “Patch.” Others were clearly related to events that took place in the mission prior to a soldier’s promotion: one rocketeer with an acute disdain for private property earned the title “Junkyard” after laying waste to a trio of sedans in addition to the aliens using them as cover. To be sure, a degree of randomness remains: why my soldiers call my backup hacker “Shakes” is a tantalizingly open question. But it’s hard to escape the sense that Firaxis has taken a more active role in controlling the horizon of possible interpretations. XCOM 2 shifts away from the sublimity of emergence and toward the coherence of an authored whole.

Likewise, operation names in XCOM 2 display evidence of a heavier curatorial hand. Enemy Unknown assigned each mission a unique name, randomly selecting a foreboding adjective and pairing it with an evocative noun (supposedly, this formula was modeled after would-be 80s heavy metal albums). The results—Operation Twisted Hero, Operation Broken Crown—were winningly tongue-in-cheek, even if the algorithm was occasionally too random for its own good—Operation Vengeful Vengeance and Operation Hot Mother come to mind. Sometimes, there were happy accidents in which an operation’s title carried an obvious connotation—one Reddit user talks about a raid on a crashed UFO hilariously called “Operation Forgotten Engine”—but, most of the time, the player was simply left to imagine the implications for themselves.

In XCOM 2, though, operation names frequently imply something about their area of operations or the types of alien forces active therein. Missions set in equatorial regions can no longer draw upon boreal adjectives (i.e., no more Operation Frozen Night in Nigeria), which now seem to be reserved for missions set above the 50th parallel, direct assaults on alien installations usually carry a religious allusion, such as Operation Hellborn Altar. To be sure, a connection between the title and the mission isn’t a given—one of my colleagues suffered through Operation Brutal Dirge (!), an incredible name with exactly nothing to do with the sortie it described—but such connections occur far too often to be mere coincidence.

Taken together, the evidence that Firaxis’ approach to ambient storytelling has shifted away from unfettered emergence and into a higher degree of authored branching seems unequivocal. Yet what XCOM 2 gains from this shift is an open question. In Khandaker-Kokoris’s telling, the benefit of authored branching is the potential for a greater degree of emotional nuance, two words that only the most generous critic could write about XCOM 2. But, implicitly, the trade-off Khandaker-Kokori describes assumes that emergence entails the “death of the author,” to borrow Roland Barthes’ legendary phrase. Yet it might be more accurate to say that it’s not authorship as such that emergence puts out to pasture; rather, emergence locates authorship not in a human touch but in a game’s algorithm. XCOM 2 is far from the only game to do this—to wit, any game with an emergent system arguably qualifies—but the subtle assertion of the authorial hand in comparison to Enemy Unknown illustrates it clearly. In a sense, it is not the changes themselves but the fact that they have changed, and what they reveal as a result, that is meaningful. Through comparison, XCOM 2 isolates the authorship in emergence in its ubiquity, like drawing a square in the sand on the beach, and so expands our conception of what it means to be an author and what it means to experience authored works. It asks us to question what we’ll allow to be considered a legitimate “author.” Perhaps the wonder of an algorithm-as-author is not that it tells a story, but that it allows a story to be told at all.

XCOM 2 is authoring its own stories at least as much as you are making yours

Despite all this, it’s only fair to note that players are free to adjust every aspect of their soldiers —appearance, nickname, nationality—as they see fit, with one telling exception. Whatever scars your squad earns in combat are permanent. As the injuries add up over the course of the campaign, their faces become increasingly disfigured. At some point, you inevitably try to obviate the physical consequences of your commands only to discover that you can’t wish their cicatrixes (or the memories of their making) away. It’s an unnerving moment, because in a game that offers you so much customization, it’s an unexpected declaration of the game’s authority over whatever story you wished to tell. Which means that if you’re willing to listen, XCOM 2 is authoring its own stories at least as much as you are making yours.

Under these terms, XCOM 2 isn’t so much a game about liberating humanity from its extraterrestrial overlords, but a statement about the kinds of stories our games can tell and allow to be told, even when they aren’t especially valued for their narrative. It speaks to the sense that we might not just want stories in our games, but authored fields of narrative possibility. Like XCOM itself, the unseen author of XCOM 2 is ever watchful, always relied upon. Vigilo Confido.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers