Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 163

February 11, 2016

The makers of Hatred’s next cheap shot takes aim at ISIS

Destructive Creations does not support ISIS. There is no reason to believe anyone ever suspected otherwise, but the developers behind the quasi-genocidal civilian shooter provocation that is Hatred (2015) aren’t taking any risks. In a Steam post, they say their latest game, IS Defense, is their “personal veto against what is happening in the Middle East nowadays.”

Let us briefly set aside the fact that “what is happening in the Middle East nowadays” is not synonymous with ISIS, which is a concern in much of North Africa as well as Nigeria, and discuss how IS Defense exercises its veto. In short, it does so by compelling you to shoot everyone in sight. There’s a backstory, sure, but IS Defense is fundamentally a game in which you man your NATO-assigned post with a machine gun (and possibly rocket launcher) and fire away. That’s it.

About that backstory: The game takes place in “a politically-fictional 2020”; ISIS has taken over North Africa and is planning to launch an attack on Europe; you are called upon to “defend the old continent.” In a narrow sense, that means manning your post and defending the continent using all the weapons at your disposal. In a broader sense, what on earth could this possibly mean? If IS Defense is the symbolic veto against ISIS that Destructive Creations says it is, why wait until 2020 before opening fire? Why, for that matter, wait until ISIS has seized control of North Africa and is threatening Europe before taking action? Even if you believe that non-white lives are cheap, as IS Defense gives every indication of believing, this seems like a poor strategy. IS Defense is not really a narrative veto against ISIS; it is simply an opportunistic excuse to use a bunch of military gear.

IS Defense isn’t even about ISIS, for that matter. Sure, it uses the name as a pretext, but that’s about it. There is no indication of ISIS’ motivations other than an allusion to its “genocidal understanding of the world order” in the game’s Steam blurb. This is far from Destructive Creations’ dumbest statement. IS Defense, however, makes no effort to differentiate between groups with arguably genocidal understandings of the world order.

The games’ basic scenario has less to do with fighting ISIS than the fight against the Axis powers during World War II. More specifically, its “politically-fictional” premise is largely rooted in the war’s North African campaign. The Allied capture of French North-Africa in late 1942 as part of Operation Torch and Tunisia in 1943 established a foothold from which the Italian Campaign, beginning with the invasion of Sicily, could be launched. In a sense, this experience established that one could invade Europe from North Africa, lending a small amount of credence to Destructive Creations’ scenario. Yet one of IS Defense’s great ahistorical ironies is that the game’s near-future version of ISIS is actually modeled on the actions of the Allied powers.

one ought not confuse political incorrectness with mere stupidity and cynicism

What does IS Defense’s version of ISIS even want? Genocide, in short, but that’s about all the game has to say about that. In this respect as well, the game might as well be billed as World War II with new labels. It is, however, trivially true and uncontroversial to note that ISIS is not the present-day incarnation of Nazism. In Europe, the counterterrorism analyst Harleen Gambhir notes, “The Islamic State’s strategy is to polarize Western society — to ‘destroy the grayzone,’ as it says in its publications.” The end goal of this process is to prove that Muslims cannot coexist with the West. (Muslims overwhelmingly reject this theological interpretation.) IS Defense largely elides ISIS’ particular motivations. Insofar as the game has anything to do with ISIS, it is acting out the Islamic State’s ambitions of a quasi-civilizational conflict that precludes any possibility of coexistence. If that’s a veto, one can hardly imagine what Destructive Creations’ endorsement of ISIS might look like.

IS Defense is an interpretive trap. It seeks to bait critics and players into proclaiming that the game’s opposition to ISIS has gone too far. There is probably nothing its developers would like more than for the game to be chastised for its political incorrectness. At the time of Hatred’s release, PC Gamer noted that the Destructive Creations’ website included the following statement: “These days, when a lot of games are heading to be polite, colorful, politically correct, and trying to be some kind of higher art, rather than just an entertainment – we wanted to create something against trends.” Much of the early reaction to IS Defense on Steam suggests that we are experiencing déja vu all over again.

It would, however, be a mistake to write IS Defense off as politically incorrect. It would be a mistake because that’s exactly what Destructive Creations wants you to do. It would be a mistake because one ought not confuse political incorrectness with mere stupidity and cynicism. Most of all, such a critique would be a mistake because Destructive Creations is too cowardly to be engaged in an act of political incorrectness.

IS Defense’s primary moral dilemma—insofar as it has one—centers on when the use of force is justifiable. There are plenty of controversial arguments to be made with regards to this subject—arguments that, by some standards, are politically incorrect. The Bush Doctrine of anticipatory self-defense is controversial in this manner, as is carpet-bombing, or endless drone warfare. One can argue that the ends justify these means (here’s looking at you, Madeleine Albright) but such arguments accept that those particular means have adverse effects. A politically incorrect argument suggests that it harms while acknowledging being politically incorrect and unpalatable are necessary to achieve some broader goal. (This narrower interpretation of political incorrectness implies that the mere hurling of epithets is not political incorrectness; Let’s let words such as racism and bigotry do their jobs.)

The entire premise of IS Defense’s “politically fictional” universe, however, precludes the trade-offs inherent in politically incorrect arguments. The deck is so heavily stacked that there are scant harms with which to reckon. The NATO-affiliated protagonists is standing on European soil shooting at invaders who have come from overseas with genocidal ambitions. Pacifists may object to this scenario, but Destructive Creations has basically recreated the textbook justification for the use of force. Supporters of public international law and the UN would find little to object to in this premise. Suggesting that a nation defend itself against armed invaders is categorically not politically incorrect.

As anyone who has turned on a television in the last year knows, there are plenty of controversial and politically incorrect suggestions for countering the threat of ISIS. Destructive Creations, however, has created a world in which shooting people makes perfect sense. Maybe that’s their goal. Insofar as that is the case, IS Defense should not be allowed to trade on the cachet of political incorrectness or even political relevance: It is simply an alternate-reality shooting gallery.

Some people just want to see the world burn. In a simplified sense, this is true of ISIS. In a different but parallel sense, this is also true of IS Defense, which creates a moral universe in which you can shoot everything in sight without feeling anything at all—especially guilt. The problem with IS Defense, however, is not the senseless violence so much as what it is supposed to mean. Destructive Creations wants to be credited with expressing a veto against ISIS’ actions but cannot be bothered to engage with ISIS in its present form. The game’s alternate-universe clash with ISIS is really just a contrivance that allows players to shoot brown men. In spite of their unwillingness to take moral risks, IS Defense’s developers still want to be credited with political incorrectness. Don’t give them that satisfaction.

Inside the mind games of cinema’s dangerous romances

Actress Marion Cotillard’s obvious allure brings the young Polish girl of the slums, Sophie Kowalsky, to life in Jeu d’Enfants (2003). It’s the ultimate film français, featuring a teasingly surreal yet realistic mind-fucking game of cat-and-mouse that you won’t forget anytime soon. Sophie’s childhood bond with Julien plunges them into a game of mind-morphing dares (“cap ou pas cap?”) that is both timeless and inescapable. And yet their game is not a prison. It gives the two jeunesse the freedom to fearlessly confront their impulses and invite one another into their own uniquely intellectual world as the heat and intensity of the game develops. The two are inevitably forged together into one mutual psychopathy, a mind game gradually leading to love.

At times witty and at times cruel, their game of dares has no limits: Sophie dares Julien to fuck another girl and then return with her earrings as proof; Julien fake-proposes to Sophie before introducing her to his future wife; Sophie concocts a story that leads to Julien being pursued by cops; and finally, Julien temporarily fakes a serious near-death injury in order to truly mindfuck Sophie one last time. Yet, despite the brutality of their love, there is an exquisitely explosive chemistry and a real bond of friendship shared between Sophie and Julien that lasts a lifetime. Would you want to play?

Having a mind game as the central conceit is a trait that Jeu d’Enfants shares with its fellow French film Amélie (2001)—it explores a game of stratagems and puzzles between two lovers-to-be. What starts as a spark of attraction between two strangers turns into a raging forest fire as Amelie and Nino spread into each other’s minds, burning through the oddities and eccentricities that the two have in common. And so the dominoes fall into place one by one in their sequential game of clues and trails and hints. It’s all rather reminiscent of the oddly detached lifelong flirtation between Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). Our modern lovers-to-be don’t even speak to each other until the very end of the film (Amelie is very shy), and so the level of communication that takes place between them— through their mind game—is quite literally beyond words, and perhaps the stuff of dreams, adding to the psychedelic nuances in the film.

Despite the other-worldly quality of these French feature-film mind games, the playfulness of each game is relatable, “the moves” that our lovers make in their games seeming to remind us of our very own mindgaming capabilities. We all end up pushing other people’s buttons through teasing or childish playfulness, starting mind teasers that will either (a) establish a real connection with someone or (b) achieve an endgoal (the latter being more manipulative rather than genuine).

Amélie‘s mind games are quite literally beyond words, perhaps the stuff of dreams

Playing mind games is our way of testing someone else in an attempt to see how well their mind can stay in sync with ours, and it’s a phenomenon that’s been tested in research studies as well. The moves that the recipient of the game makes in response to the initial mind-teasing invitation becomes a conversation or a dance between the two individuals involved.

The mind game phenomenon among humans is thoroughly explored by Stanford professor Nir Halevy. Halevy attempts to determine the uses of everyday mind games in terms of negotiations and conflicts. According to his research, collaborating with Eileen Chou and Keith Murnighan from Northwestern University, there are four types of significant mind games that can occur between two people. Statistically, these four clearly stand out from the 576 mind game possibilities that can be played between any pair of individuals. These possibilities were narrowed down based on three key assumptions: (1) That we as humans love symmetry and simplify both the conflicts and the negotiations involved as being “symmetric”, (2) that we as humans are happier when there is cooperation rather than conflict, and (3) “that there will be (at least some) correspondence between the games that scholars and lay people see as psychologically compelling.”

The research concluded that “the games people think they are playing” play a major role in their own perception as well as their opponent’s perception of the situation at hand. In fact, two of those four games aren’t overly aggressive and ultimately lead towards a cooperation of sorts, whereas the other two games are overtly aggressive, focused on competition rather than partnership. Perhaps the mind games in the French films fall under the category of games that are ultimately cooperative rather than being in a state of constant diametrical opposition.

But compare this to the 2014 American film Gone Girl. It features a definitively more grotesque game of complete deceit and manipulation that has the potential to make your bones tingle. There is an underlying darkness and cynicism that gradually envelops the film, making it a colorful juxtaposition when compared to the French films, which primarily emphasize true love or passionate love. In Gone Girl, Nick and Amy are introduced as a young couple in love with a bright future ahead of them, and yet their passion gradually dissipates into something that is toxic and competitive as they continue to infect each other with the poison in their minds. The marriage ultimately becomes a sinister trap that they inflict upon one another. The game between these ex-lovers is one of mental torture and anguish as they both decide to live out a lie for the rest of their lives.

Think on that as well as this interesting note about the French language itself—there is no word or term to describe the concept of a “mind game”. This is a purely English construct and perhaps says something about the love culture of English-speaking societies when compared to those of French societies as a whole. Couple it with this 2003 survey, which claimed that the French have the most sex out of any other country, while the Americans seem to be all talk and no play with their thirst for instant gratification through online dating. As a woman who has spent time in both countries, I can definitely say that the Americans have a thing or two to learn from the French when its comes to amour. The differences in the mind games that each nation’s fictional lovers play seem to also confirm as much.

Play Firewatch for a breath of fresh air

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Firewatch (PS4, PC, Mac, Linux)

CAMPO SANTO

People say they go to videogames to escape. And they say they go to the wilderness for basically the same reason. To get lost in something bigger—something outside themselves. But wanting to be lost is one side of wanting to find another answer. Firewatch throws players into the existential crisis of protagonist Henry, a middle-aged man looking to restart his life as a park ranger in a national forest. Through lonely exploration and dialogue choices, the player shapes Henry. With only a fellow colleague on a walkie talkie for company, Henry is left to wrestle with the questions of escape on his own in the Wyoming wilderness. Created by ex-Telltale designers, Firewatch centers around a gripping narrative while also setting a simultaneously eerie and peaceful atmosphere for self-exploration.

Perfect for: Telltale fans, outdoor enthusiasts, Idle Thumbs listeners

Playtime: 4 hours

The Deadly Tower of Monsters revels in the schlock of B-movies

Bad movies can be a laugh to watch. It’s best done with a certain camaraderie, a group of buddies getting together to voluntarily partake in schlock, probably with alcohol and snacks to push them through it.Hell, Mystery Science Theater 3000’s (1988-99) Joel Hodgson has made an entire career out of that idea alone. But stripped of the jokes, there’s only so many rubber-masked martians and tin foil spaceships held aloft by fishing wire that your average viewer can tolerate. Let’s be real: no one is earnestly watching 1950s camp like This Island Earth (1955) for its cinematic merits.

The cornball DNA of Mystery Science Theater 3000’s movie-of-the-week fodder is baked into The Deadly Tower of Monsters, a fairly stock top-down shooter wrapped in 1950s B-movie trappings. Presented as a remastered DVD edition of a fictitious long-gone film, we’re given director Dan Smith’s commentary of the on-screen action as “intrepid explorer” Dick Starspeed traverses planet Gravoria.

As Starspeed, the mysterious Scarlet Nova and “The Robot,” the titular tower throws schlocky monsters of every variety your way, with Harryhausen-lite dinosaurs, rubber-masked monkeys, and flying, pulsating brains showing up to mindlessly take a beating. We never quite find out why Starspeed is on Gravoria, and Smith’s commentary cops to the fact that it doesn’t really matter. It’s the action that counts, right? We’re here to see some baddies get beat up, so let’s get to it.

True to the hackneyed plots and tacky costumes of the films the game is aping, there’s a charm in the low-rent plot and absurd sidequests. The artifice of the game’s aesthetic choices lend to some amusing jokes on Hollywood tropes of the era like reused sets, unexplained character motivations, and technical gaffes of every flavor. However, this visual comedy isn’t matched by the voiceover. Compared to recent game narrators who reflexively comment upon player choices and decisions, like those of Bastion (2011) or Transistor (2014), Smith’s anecdotes remain relatively static. Get to point A, he makes a joke. Get to point B, a story about somebody bringing their kid on-set and dressing them up like a squid. And so it goes. While a story about getting chastised by the crew for rubbing his greasy hands all over the camera lenses (just as massive on-screen fingerprints cover the action) is chuckle-worthy, most of the commentary falls a little flat.

No one is earnestly watching 1950s camp for its cinematic merits

Most impressive with all of this is the game’s ability to tirelessly throw absurd scenarios at you as quickly as possible. While the plot and characters are mostly relegated to window dressing, the tower itself and its goofy inhabitants easily become the star of the show.

As soon as you find yourself tiring of beating back waves of bone-wielding monkey-men, it’s time to destroy an island of mutated ants. Once those have been exterminated, it’s a jetpack-fueled platforming section. Have a new gun. Or three. Kill a gigantic ape. Go skydiving. Thwack some dinosaurs. Listen to Dan Smith’s pointless anecdotes while deflecting pteranodons and fireballs. Every bit of action takes place on just the one tower; a vertical sandbox environment. Rather than traveling to far-off mountains or exploring sprawling cities, you’re free-falling from a few thousand feet in the air before warping back up to the top.

The burning question of “how did this get made” looms over any terrible movie. It’s usually the fever dream of an insurance salesman from Idaho or a wayward studio executive hell-bent on cashing in on the latest fad. That a trainwreck of a film with such a production was able to navigate the layers of red tape in Hollywood makes you wonder who is responsible for greenlighting these disasters. The enjoyment of this garbage entertainment usually comes in the schadenfreude of watching those dreams come crashing to earth. Recreating the aesthetic without the real-world consequences leaves The Deadly Tower of Monsters feeling a bit hollow. Is seeing a boom mic dip into frame still funny when an art director decided to place it there, rather than somebody’s nephew just slacking on the job? No, not really.

That said, while The Deadly Tower of Monsters might be silly and a little clunky, it’s hard not to root for something that lovingly apes (for lack of a better word) a bygone era so successfully. Nobody is going to mistake Them!’s (1954) nuclear-sized ants for High Art, but you can’t blame yourself for chuckling at the screen while reaching for more popcorn. Even professional bad-movie-watcher/joke-writer Bridget Jones-Nelson of MST3K admitted to Wired that “occasionally, you’d be watching the movie and you’d forget to riff, because you’d get wrapped up in it. Even if it was Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues, I’d be like, ‘I kind of want to know what’s going to happen!’”

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

February 10, 2016

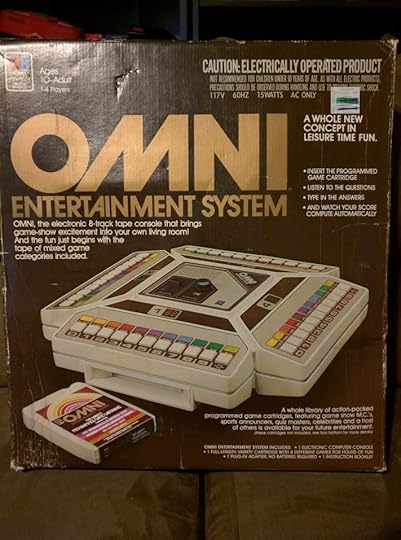

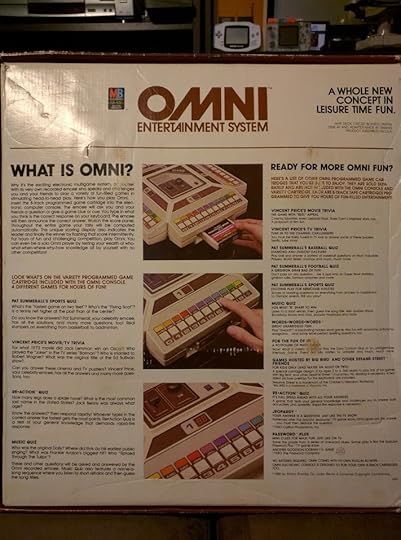

A closer look at the audio game console from 1980

Did you know there were such things as audio-only game consoles? We’re going way back to 1978 for the first of these, Mego’s 2XL Robot, which had you insert 8-track cassettes that told jokes, hosted quizzes, and gave you mathematical problems to solve.

But that’s not what classic game enthusiast zadoc recently shone a light on. They, instead, give us a closer look at Milton Bradley’s Omni Entertainment System, originally released in 1980, and that replaced those 8-track cassettes with 8-track cartridges. This was a time prior to Nintendo’s entry into the console world, when the likes of the Magnavox Odyssey, the Atari 2600, and Colecovision were all competing alongside dozens of others for a piece of the burgeoning gaming audience’s attention. And while this may have eventually lead to the videogame crash of 1983, which saw the Western market’s dominance fall as Japan rose to take its place, it also encouraged a good deal of experimentation. The Omni Entertainment System is one of the less-remembered manifestations of this era.

The console was originally developed as a way to bring the game show experience to the living room, but as Milton Bradley felt videogames weren’t ready to handle the task yet, they instead went a different route: the audio game. Taking an 8-track player and placing it in the center of four control panels, the system paired pre-recorded trivia cartridges with a small computer that would register answers and keep track of scores. It was clunky, sure, but Milton Bradley had enough faith in it to hire celebrities like Vincent Price, Pat Summerall, and even Sesame Street‘s Big Bird to host their games. Now it is largely forgotten, with Google searches for it directing mostly to obscure collector forums. But it is of note for serving as one of the first examples of blindness accessibility in videogames, however unintentional.

one of the first examples of blindness accessibility

Last week, we published a feature from Robert Kingett on how he approaches playing and writing about games while blind. It’s well worth a read, but one of his sticking points is the lack of basic accessibility options in games. “It’s true that videogames have tried to become more accessible over the years by providing more ways to customize their experience,” he writes. “But the reality is videogames still have too few accessibility options.”

Today, audio games live on in sites like AudioGames.net, which keeps track of hundreds of small, experimental sound-focused projects across multiple genres. There’s even an audio-only version of Super Mario Bros (1985). While much of the discussion surrounding games as a whole is often focused on videogames, there’s no reason games have to be restricted to visual mediums. The Omni Entertainment System and its more recent descendants serve as an example of how focusing on non-visual output like audio can serve audiences that, as Kingett explained, currently often lack attention from big developers.

Lead image credit to Zadoc on Imgur.

Where’s Waldo? finally gets interactive in this videogame

Where’s Waldo? (1987) has stepped out of the past and into a super stylistic new game. Hidden Folks is the latest from game designer Adriaan de Jongh, in which you can relive the eyestrain of days past in a grown-up version of the classic find-the-character game. This new project comes in the wake of de Jong’s previous efforts, the quirky titles Fingle (2012) and Bounden (2014), produced with the now-defunct Game Oven. This time he’s teamed up with illustrator Sylvian Tegroeg to create something entirely different.

The premise is simple and differs little from its striped-shirt predecessor: find the hidden character in a crazy busy illustration. Hidden Folks, however, kicks it into hard mode with the added layer of interactivity through animations and moving parts all doing their very best to snag your attention. Even when they aren’t moving the black and white illustrations are delightfully intricate and filled with charm. Animated, they have a music-box-like magic that’s just mesmerizing.

The interactivity itself doesn’t add anything particularly revelatory here, but it doesn’t need it. There is a certain pleasure of finding hidden things and a certain frustration at not being able to find them, especially when you know the secret is right there in front of you. Bringing the Waldo concept to videogames only fits the bill: Games are notoriously good at hiding secrets and players are just as good at finding them, even if that’s not always blatantly the objective. And whether that means finding the guy you’re actually supposed to be looking for or just noticing all the tiny enchanting details of the moving illustrations themselves will be up to you to decide.

Prepare for something new from Kentucky Route Zero soon

We really like Kentucky Route Zero. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it’s the Ideal Kill Screen Game: aesthetically surefooted, poetic, funny, surreal, and melancholy. (The other pole of this is, like, last year’s Bloodborne, or something.) So when designers Cardboard Computer tease more Kentucky Route Zero in their inimitable, coy way, we jump all over it:

That image is all Cardboard Computer tweeted out. Since their customary pre-episode interlude has already been released (2014’s delightful Here and There Along the Echo) I can only assume this is from Act IV proper. I’m sure I’ll wake up in three weeks or so and a elderly, neatly-suited man will knock at my door. He’ll deliver a bottle of ice-cold milk. A chicken will shuffle into my foyer as I speak to him. Taped to the bottom of the bottle is a USB drive containing Kentucky Route Zero Act IV.

There’s a quote from Martin Scorsese that Cardboard Computer seem to innately understand: “cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Kentucky Route Zero has been uniquely interested in frames, from a TV that shows the future in Act I to the transportive, celestial musical interlude in Act III. All we can see here is an apartment block, stretching beyond the frame in every direction, with a single figure standing on a balcony. It’s a prosaic image, but following the more industrial Act III (contrast with the earthier Act I and II) it suggests the scope will be widening even further on the story of Conway and his friends.

But there’s no use trying to divine where Kentucky Route Zero is headed. It’s the most mercurial, exciting, ambitious game going, and we hardly deserve it.

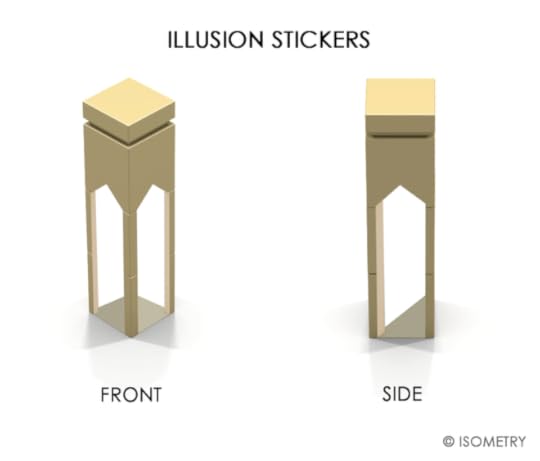

Monument Valley’s illusory architecture could become a Lego set

Monument Valley (2014) and Lego. It just feels right, doesn’t it? Maybe it’s that the puzzle game’s isometric perspective gives us the privileged view of god games, in which we build and destroy. Or perhaps more simply it’s the attention the game draws towards it brightly colored geometric mazes, eager for us to prod and spin them. Either way, there’s something about Monument Valley that makes it ripe for a transformation into modular Lego blocks. Now, there’s actually a chance of that happening.

The first step towards this end goal has been made through the proposal of a Monument Valley set over on Lego Ideas. Yes, it should have happened months ago. There should be Monument Valley blocks being pressed in Lego factories right now. But there isn’t. And there’s still no guarantee that it will happen, even with this Ideas pitch now existing. It requires tens of thousands of people actively supporting the pitch on the Lego Ideas website to even get it accepted by Lego. Right now, it’s only recently stepped over the 1,000 mark, with 500-odd days left to get the rest.

It’s a long way off. But have faith: This is how the Minecraft (2011) Lego set was born (among many others), and look at it now—an essential part of the entire Lego brand. Monument Valley is surely widely loved enough to get similar treatment. Even if you’re not familiar with the game the aesthetic has a broad appeal. The tomato-red arches, the indented ladders, the clean corners of rotating walkways that slot into position with a satisfying perfection; it’s all gorgeous. Not to mention the cute-as-heck characters that navigate these dioramas. Especially Totem. Everyone loves Totem and that big googly eye.

the Monument Valley Lego set would have “illusion stickers”

But there’s more to the game and this proposed Lego set than just that. If you’ve played Monument Valley, you’ll know that its puzzles have a basis in the graphic art of M. C. Escher. It’s all optical illusions, architectural sleight-of-hand, labyrinthine trickery. Of course, plucking all of this out of its digital format means that the impossible parts of these illusions are lost. Actually, not quite. For the Monument Valley Lego set would have “illusion stickers” that give the impression that the sacred pillars have different forms when viewed from the front and side. Pretty swish.

You can support the Monument Valley Lego set over on Lego Ideas.

Falling through 100 million stories in Gravity Rush: Remastered

Gravity Rush (2012) director Keiichiro Toyama didn’t choose horror, it chose him. His first game as director, Silent Hill (1999), was assigned to him by his bosses at Konami. A stranger to horror as well as a self-professed scaredy-cat, in order to find his feet Toyama turned away from schlock and gore and towards those softer influences that did appeal to him: occult practices, mystery stories, and evidently enough, the work of David Lynch. Silent Hill’s thoughtful, ambiguous atmosphere may have gone on to define survival horror, but it also went on to define Toyama’s career. Which is why Gravity Rush, with its cartoonish sensibility and playful atmosphere was something of a curveball when it released on the PlayStation Vita in 2012. Beautiful and ambitious, it suggested a grand vision for a portable game, and an unlikely outlet for a reputed horror auteur. Somewhat of a critical success at the time, Gravity Rush has since been granted a sequel on the larger canvas of the PlayStation 4, as well as a full remaster. Buffed to an attractive sheen by specialists Bluepoint Games—responsible for both the Ico and Shadow of the Colossus remasters (2011) as well as The Nathan Drake Collection (2015)—Gravity Rush: Remastered is a vote of confidence in Toyama’s vision, and an attempt by Sony to widen the game’s audience. It works: even after four years, its distinct gravity-shifting, which sees protagonist Kat forever falling across its floating city, retains a sense of newness. But it is the game’s multi-layered, ornate city districts which are its most magnetic aspect. And it is in those densely packed towers that the game’s unlikely origins can be found.

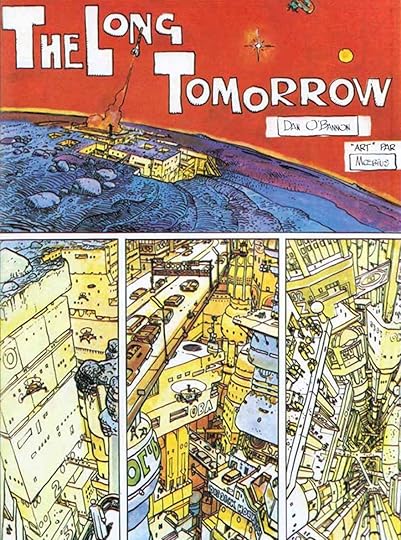

As a student, well before Silent Hill, Toyama was fascinated by the bandes dessinees of the 1970s, those French comics that found their way around the world among the pages of magazines like Metal Hurlant (or Heavy Metal, in its latter American form). Filled with precise line work and loose, bright colouring, these wildly inventive science-fiction stories and psychedelic trips had a unique influence on a whole generation of artists and writers. Jean Giraud, known by his pen-name Moebius, might be considered the most influential among them. In fact, his short graphic story, The Long Tomorrow (1975), created with Alien (1979) writer Dan O’Bannon while they were doing preparatory work for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-to-be-made Dune, has an almost unbelievable legacy for such a little known work. Cited by three of the godfathers of science-fiction, it has been named as a key influence by Katsuhiro Otomo for his epic Akira (1988), by William Gibson for the textures of Neuromancer (1984), and by Ridley Scott as fueling the rich visual language of Blade Runner (1982). Such a collection of names and works represents high praise for what is a 16-page graphic short, a succinct blend of noir detective story and urban sci-fi with a taste for the surreal. Despite its age, and the fact that its visual language has been strip-mined for ideas, it’s still possible now to see why it was so influential. Otomo called it “dirty,” Scott labelled it as “a tangible future” of “cities on overload,” and Gibson referred to its visual texture as “density” and “perceptual overload”. What each of them found in Moebius’ work was an analog for a changing world, a hyperactive layering of images and frames. The final line of The Long Tomorrow is “There are 100 million stories in this city, this was twelve of them”. A pun on a classic noirish line, and a reference to the height and depth of Moebius seemingly endless, dirty, and dense city.

a death-defying fall

Yet Toyama saw something different in Moebius’ work. Something that is as equally present as the density and the dirt. He saw the romance, the scale, the Parisian belle-epoque style that lay just beneath the surface which, when washed clean, would bring forward something other than those stygian cyberpunk cities. After all, Blade Runner, Akira, and Neuromancer took the grand visions and colourful pulp of ‘70s science fiction and fed it into an ‘80s atmosphere of grunge and chunky technology, layering on the dirt of the street and the struggle of those who lived there. Looking at Moebius’ work in the ‘90s Toyama saw instead its optimism, its sense of wonder and scale, and the beauty of its ornate linework. Moebius, too, followed this path, his work drawing away from ugly urbanity towards a colourful and luxurious future. The Incal series, perhaps Moebius’ greatest work and a clear development of The Long Tomorrow’s hardboiled future, charts exactly that path. Beginning with the similar set-up borrowed from the work of noir writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, it accelerates out of the densely layered city towards a universe of surreal landscapes of crystals and prisms, imbued with the bizarre mystical hallmarks of its co-creator, Alejandro Jodorowsky. This is the Moebius that Toyama brings to the fore in Gravity Rush and its remaster. Almost garish colors back its grand city-islands, which buzz with a bright sense of life. Illegible script flowers atop beautiful art deco towers, while Parisian rooftops are multiplied and layered in impossible formations. And perhaps the most startling connection is the viewpoint that Toyama chooses for the player to experience this setting—the dramatically converging perspective lines of a death-defying fall.

If you turn to the second page of The Incal you find the inception of Gravity Rush, right there, nestled among the panels. John Difool, the private investigator and protagonist of The Incal is plummeting face first into a panel rich in detail, a city of overlapping walkways, ornate skyscrapers and a festering, glowing sense of life. As it recedes down below Difool, the linework of the city takes on an increasing simplicity, until it resolves into a handful of sketched shapes, and then at the lowest point, blank white. It’s an image that draws you in, as your eyes rehearse Difool’s fall again and again, each time picking up on new details as you scan the city from highest peak to lowest depth, from the pile of newspapers outside a door, to single points of distant passersby. This often imitated panel is both The Incal’s most resilient image, and Gravity Rush’s most explicit connection to Moebius. In fact, this image almost feels like a design document for Gravity Rush, giving it both its setting and its mode of locomotion. That’s what Toyama understood so clearly, that Moebius’s iconic dense cities were not just a collection of richly layered stories, but a perspective too.

This perspective is a difficult one to tire of. In Gravity Rush, it’s easy to find yourself climbing again and again to the edge of the tallest and most ornate tower just to throw yourself off, slipping between walkways and through gaps on the way down. The game’s gravity shifting, along with its floating city-islands mean that you can bisect the city, cutting through it at any angle. These trips are rewarded too, with new angles constantly revealing themselves, as hollowed out interiors are found to be filled with terraced slums, and crisscrossed pipes reveal hidden passages hundreds of flights of stairs below street-level. It’s often difficult to resolve these dizzying angles into a single city, and returning to the leafy square where you started your journey is as much of a surprise as any other. Even at pedestrian pace, Gravity Rush’s city seems to reveal layers and layers of hidden depths, from food stalls to the mix of characters you share the street with. To travel like this is to be defined by a vector, to simply choose a direction and then fall into it for as long as you can stand. It redefines the city as an object, one where each surface can be touched, each direction followed to its conclusion. In its movement Gravity Rush allows you to step lightly from every rooftop, to find by falling. To bisect the city, surround it, touch it, yet never fully conceive it. This city asks you to fall into it, eternally, like Difool tumbling head-first into Moebius’ linework, revealing a future that would be realized elsewhere by other artists with other aims, but carrying the same dizzying sense of forward momentum.

February 9, 2016

Timruk explores the layers of historic violence beneath its beauty

Pages contain bodies and blood both literal and metaphorical. Illustrations and text occupy a confined world of disarray, littered with skulls. Among this is the beauty of rain falling and of bright wallpaper colors. A world where your hands are not your own. This is a world of contrasts, the world of Timruk, the world of Somewhere.

Studio Oleomingus is simultaneously in the business of beauty and violence. Its latest game is called Timruk, which is a fragment of the larger upcoming videogame project Somewhere, following on from the studio’s previous off-shoot, Rituals. All these games have in common a thematic basis in colonial India but Timruk is a little different. It is concerned with a particular story that was, it should be clarified, entirely constructed by Studio Oleomingus.

The game’s page tells us that this story originated as wall paintings which were translated to written form by a poet for the Rajah’s court in 1821. Later, this story became part of a larger folio, accompanied by miniature paintings scavenged from various Persian and Mongolian sources from the Maharajah’s library. Finally, the manuscript was translated by British historian, Prof. James P Fielding, being published in 1903. Timruk is said to be based on a copy of this historical story found in the archives of Calcutta State Library.

Studio Oleomingus is simultaneously in the business of beauty and violence

To honor its fictional source, Timruk is experienced as a storybook that presents you with ornate pages from the start. But the true experience of the game is being able to literally enter these pages and emerge in a courtyard. From there comes the narration, telling the story of two sons—both named Timruk—primarily through text and illustrations, which overlap with the rooms you find yourself in.

While it’s easy to read Timruk as being about about colonial forces in India it’s clear that Studio Oleomingus means to allude to far more complex power dynamics at play. Early on in the game, a telling of a battle is recounted, it mentioning that the book making workshop is walled up, as it’s feared the book maker’s need to depict the bloody battle will consume a precious and rare red ink. Here, the parallel between resources and bodies is subtly made—one must be sacrificed for the good of the other.

This theme is continued with ongoing reference to the beauty of book making and exclusionary collecting, with reference to all the rich resources that surround the craftsmen (golden leaf, Lac and Ocher paints, Mongolian ink pots etc.). These intricate trails of trade and war, as well as issues of class and luxury, have informed so much of human history. It reminds us that complex power dynamics stretch far beyond a world we often take to cleanly dividing into “pre/post-colonial,” as if we cannot imagine another metric. Perhaps we cannot, considering that our current context is so meaningfully enmeshed in that constructed divide in history. We are stuck.

As the pages turn in Timruk, you are transported from room to desolate room. Each contains its set of skulls. Death is everywhere. The contrast of Western-styled sitting rooms and open courtyards, and how they repeat in different forms, enhances the sense of limbo. Timruk is desperately beautiful from the rooms to the pages, but the quiet yet insistent layers of violence persist. It seems inescapable.

Timruk is free to download and play on Mac, Windows, and Linux. Be sure to follow Studio Oleomingus’s Tumblr for updates.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers