Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 165

February 8, 2016

QWOP goes avant-garde in this silly dancing game

I’ll admit upfront that I’m a terrible dancer. Not the kind of terrible that is actually cute. I’m talking the real, awkward kind of terrible. I blame it on being tall. It’s just not easy to make limbs in these proportions move cohesively the way I’d like them to. Maybe that’s why An Evening of Modern Dance caught my attention—it’s easy to see a bit of myself in its hilariously floundering dancers.

An Evening of Modern Dance follows in the tumbling footsteps of QWOP (2008) and Octodad (2010), this time bringing ragdoll physics to the stage. Made for Ludum Dare 32 by Joseph Parker, the game has no objective other than dancing. In it, you attempt to control one to four abstract human figures in a brief dance performance, backdropped by randomly generated modern “music.” Typical shenanigans ensue.

The spotlight brightens, the first chord strikes, and your performance begins. The only trick is that all attempts to move in a way that resembles actual dance result in utter and laughter-inducing failure. Any sense of real control over the dancing figures is fleeting at best, especially if a (ridiculously easy to trigger) glitch causes one or more of your dancers to, say, inexplicably burst into flailing pieces and/or completely fly off the stage and into the blue void beyond the walls (“If the physics glitch out you need more dancing practice” quips the game’s description). The fact that the controls are relative to the dancer and not you as a player only makes it even harder.

I found myself chuckling just as much at the standard ragdoll tumbling about as I did when the dancers performed game-breaking flights past the walls. It only felt appropriate, really, because ragdoll mechanics already toe the line between intention and glitch. Maybe that’s why they’re so damn funny—because it seems like the game’s broken, and it seems like the dancer’s broken too. Take an avatar with warped responses and add a player with frustratingly ineffectual controls and you get one piss-poor imitation of a ballerina. Something in between algorithm and human happens on the screen that isn’t quite either.

poke fun at avant-garde modern dance

But the ragdoll comedy is only amplified here because modern dance is supposed to be Serious Business Art. I mean, what better way to poke fun at avant-garde modern dance than with slapstick ragdoll physics? And there can surely be no better setting for the hilarity of flailing about than a stage meant for highly precise dance. And yet I get the hankering to make something more of it. Maybe An Evening of Modern Dance is an assertion that games won’t ever be Serious Business Art in the heavily elitist way that modern dance can be—not when game makers refuse to take themselves seriously, not when laughter (obviously the enemy of Serious Business Art) is so welcomed and expected. Though, in making that statement, I give the game a dose of the art cred that it probably doesn’t want. It just wants to flail across the screen, broken and beautiful for it.

Role-playing games are just like medieval oral culture

You’re woken from your slumber by the piercing cries of a man in agony and the splintering of wood. The room is dark, though the glowing embers in the grate cast a dull glow across rapidly moving shapes. All about you is pandemonium: guttural panicked sounds of man and beast.

Its stench strikes your attention before you realize it’s stood beside you but in the fire’s dying glow you can see the heft of a large arm reaching out to grab you.

Roll for initiative.

///

Hwaet.

This word—usually translated as “listen”—marks the opening of Beowulf, one of the rarest surviving stories in Anglo Saxon. In fact, the 3000-line heroic epic was only discovered during the cataloguing of survivors of the eighteenth century library fire that nearly destroyed the single extant copy.

Yet it is as unlikely that it survived as it had even been written down in the first place. Trained scribes were not cheap. Paper didn’t exist (Beowulf is hand-written on calf-skin parchment). People couldn’t read. But they could listen.

This meant that narratives developed under a culture of storytelling: an oral tradition where tales were spoken and sung. Poets would travel from place to place, performing their favourite stories for disparate audiences, learning of new stories and honing their performance through subsequent retellings. Though skilled, the poet was not an artist—these were not her stories, these were just the stories she told.

PEOPLE COULDN’T READ. BUT THEY COULD LISTEN

Over time, the stories would evolve: through mutating multiple tellings, through hundreds of different poets telling their preferred versions, through tangents and flourishes loved by the home crowd. Different versions of the same story would cross paths and cross-pollinate. The story lived—a memetic, quantum entity not to be enslaved in pen and ink.

Yet every so often, someone would invest the great resources of time and expense to have one of these stories written down. This facsimile was a mere moment in time, like the photograph of a ghost departing. Several manuscripts might tell the same story but they have each been captured in different places, in different times. The words, the phrasing, the structures even, are ever so slightly different: uncanny doppelgangers of their own mirror image.

One of the best examples of this is Sir Orfeo—a medieval retelling of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth, replete with otherworldly fairy king and machinations of court politics. Three distinct manuscript versions exist and while each pair shares nigh-identical features, it is clear that none of them are directly related. In fact, it’s my opinion that J. R. R. Tolkien’s greatest work is his version of the “perfect” Orfeo: an ur-text to father the others.

Today, the brand of authority is everywhere. Even in the field of writing where the listener is most likely to retell it herself—that of comedy—there is still a thorough sense of parental ownership in the creation of jokes. Joke theft is viciously decried.

It would seem that oral culture has died, selectively bred into extinction. But I believe it still lives. Around the gaming table, its ballads are sung to the clatter of falling dice.

///

Tabletop roleplay is difficult to directly compare to other media. Usually, a number of players will each take on the role of a single character, the same way an actor assumes a role in a play. Another player becomes everything else, as a stage manager might control the set design and the stage directions, as a director might direct the responses of the extras. Unsurprisingly, this more complex role is often titled the Games Master, or Dungeon Master, or Keeper, or Referee, or whatever is canonical to the game at hand.

But where a traditional play is intended to be performed to an audience, a roleplaying session is like an improvised radio play where the actors are its audience.

BALLADS ARE SUNG TO THE CLATTER OF FALLING DICE

Late last year, Paradox Interactive bought White Wolf Publishing—the house behind the monolithic World of Darkness roleplaying games. The series had begun in 1991 with Vampire: the Masquerade, and although I’ve never played it myself, its cover of a single resplendent red rose on a stark field of verdant mausoleum marble sticks firmly in my mind. While not as old as Dungeons & Dragons (itself having recently published its fifth core edition), White Wolf’s systems and mythologies remain some of the most popular properties in roleplay publishing.

Within six weeks of owning White Wolf, Paradox rebranded their current line. Fair enough, the distinction between classic World of Darkness and new World of Darkness was somewhat unwieldy. Now called Chronicles of Darkness, it not only shows their lineage but also implies an increased importance on the stories told.

It’s around gaming tables that these Chronicles will manifest: using the patterns and shorthand taught by the books, recognized by the people who have never read them.

///

Barely a fortnight into 2016, Wizards of the Coast announced the DMs Guild. It’s an in-house marketplace for Dungeons & Dragons players to create and sell their own material using controlled D&D intellectual property. This would allow Dungeon Masters to use some of the game’s more iconic creatures, such as the displacer beast or the beholder, while providing them safety from the company’s more perilous creatures: its legal team.

Rather than merely providing a platform for crowdsourcing of ideas, Wizards are shining a beacon to all players of the game with the DMs Guild. Pulling together as many story seeds as they are able could considerably catalyze the narrative potential that thrives within an oral culture.

Relatedly, one of the biggest elements of the medieval oral culture—especially when we see its evidence in the poems that have been written down—is that the audience of the story is a considerable driving force behind its evolution. The same is true when it comes to tabletop role-playing games. It might appear obvious on the surface considering the improvised telling of a collaborative story. After all, the compact audience are directly making choices about the protagonists’ interaction with the world. Yet the structures of the game systems themselves promote a deeper, subtler shaping of the audience interests.

AN INCREASED IMPORTANCE ON THE STORIES TOLD

Any different group will have its own preferences regarding the elements of play: a preference for sneaking over combat, for political posturing over wilderness exploration. The elements that the players are less interested in can be increasingly abstracted, dealt with by the whim of a dice roll in the wings—the critical fumble that led to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s death in Hamlet (1603), for instance. The elements that players are more interested in will be foregrounded in play. Not only does this happen through overt choice, but the increased attention will iteratively improve the players’ skill and invariably lead to more challenges of a similar sort.

The ways in which both tabletop games and orally-transmitted stories evolve by audience interest plays along an interesting interstice between flexibility and freedom. Inasmuch as the stories shift based on local interest, they do so by adhering to remarkably regular forms. This exploration of form is something that has remained a mainstay of poetry until modern times. That applies even when shifts in fashion are taken into account, such as how the 1066 invasion of England meant the French style of rhyming couplets pushed the alliterative English form outwards and upwards. Creativity stems from the boundaries enforced by formulaic restriction.

It’s a careful line to tread. In role-playing adventure design, one of the greatest sins is that of “railroading”—i.e. restricting player agency to a choice of forwards or stop. Yet some of the strongest designs come from deftly playing with a classic structure. Innovation and originality stand clear in the shadows of a familiar space.

The structures of roleplaying and of oral culture themselves are also echoed at sentence level. If you read a lot of Chaucer, you’ll find the phrase ‘for the nones’ crop up with regularity. Verbally it means ‘did you know,’ but linguistically it mostly exists to carry the meter of the line—to settle the rhythm and enable the rhyme. Similar verbal cues occur in roleplaying. From reference to character statistics like Humanity to instructions to players to ‘make a pull’ or ‘roll for initiative,’ these cues serve to ease the transition between the primarily narrative-driven aspects of the telling and the mechanically-powered parts of the story. The common tongue of stock phrases ushers the change of focus, interrupting without interfering.

But above all, medieval fiction and the stories derived from it have an intense awareness of their past, a thorough understanding of their own nature. Promoting the unobtrusive self-aware elements of oral culture in tabletop roleplaying will provide better sessions, better stories. At the very least, it helps to be conscious of the connection between the style of story and its strengths.

Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings (1954) to provide a modern mythology that he felt had been lost with the dwindling oral culture of his beloved medieval era. Tabletop roleplaying began by attempting to retell stories like The Lord of the Rings. But rather than simply reinvigorating the heroism of Tolkien’s tales and the idiosyncrasies of his cultures, it has breathed new life into a pattern long thought lost. It’s revived an oral culture.

Canterbury Tales image via Wikimedia

D&D image via Youtube

Orfeo image via Wikimedia

Campfire image via Flickr

February 5, 2016

Screensaver jam results in a colorful throwback to the ’90s

You don’t really see screensavers all that often anymore. I know that when my computer enters sleep mode, I just have it set to display a black screen. It’s the same thing for all my friends as well as most offices I’ve visited since turning 13-years-old. Maybe it’s a consequence of our modern habit of leaving our computers on at all times, since if your computer is constantly sitting asleep in the background, having it display a bright or showy screensaver is just distracting. Or maybe it’s because we don’t need screensavers to protect our displays from burn-in images anymore, so having one now is more of an affectation than a necessity. But in the ‘90s, they were everywhere. Brightly colored and tacky was the dress code for the decade, and I remember the classic flying toasters of my youth well.

I’m not the only one, it seems, as Kitty Calis and Jan Willem Nijman of Utrecht-based videogame gallery Broeikas recently took to itch.io to host a screensaver jam, the results of which are a real throwback to my 3rd grade computer lab. Submissions vary among looping animations, playable minigames, and even one particular feature-length entry, but a few common themes are scattered throughout. Pixel graphics are popular, as is simple CGI and abstract fractals, and many entries feature tacky neon colors. When scrolling through these, I feel like I’ve entered an episode of Full House.

Brightly colored and tacky was the dress code for the decade

But this is itch.io we’re talking about. There’s bound to be a few avant garde aspirants out there. In an attempt to update the screensaver for modern sensibilities, some entries have ditched looking like the Rugrats title card for a sleek, contemporary design of harsh blacks matched against stark whites, all set to angular imagery. One in particular looks like a Japanese Shinigami (death God) mask, which brings to mind well-off Americans hanging meaningful foreign art on their walls just to impress their friends at dinner parties. Yet another just straight up looks like The Witness. In stark contrast to the first camp of entries, these submissions shed some light on what screensavers might look like if we still used them today.

Like Geocities, the bombast of screensavers from the late ’80s and early ’90s were often indicative of just how much we still had to learn about user experience on computers. It reminds me when I was a middle-school girl, just absolutely destroying my face with makeup before I learned how to apply it with subtlety and grace in college. But that’s the beauty of these awkward growing phases- they show us at our most vulnerable. And even if you’ve put these things behind you, sometimes it’s relaxing to go back and look at your old Lisa Frank three-ring binders.

The dizzying art of the cinematic zoom invades videogames

Zooms have long been the crux of dramatic filmmaking. Legendary director Alfred Hitchcock popularized the dizzying camera effect in his classic thriller Vertigo (to, obviously, envelop the viewer in a sense of vertigo). Afterwards, zooms became a trend among filmmakers seeking to add that extra depth of environmental distortion to a shot – sometimes even to comedic success. For videogames, the art of the cinematic zoom is harder to master. In most cases, the player has control over the camera, and cutscenes hardly ever implement such dramatic effects. In reaching, a game borne out of a recent Global Game Jam, the omnipresent camera zoom is instead the sole guide of the game, utilized to its fullest extent.

Reaching is emblematic of everything excessive about the zoom

Developed by Peter Smyth and Thomas Newlands, with music and sound effects crafted by Luke van Oene, reaching follows an egg-headed person in its monochromatic home. First the player walks about its living room, then its kitchen, then the bedroom, before repeating itself over and over again, flowing seamlessly via camera zoom. Reaching is emblematic of everything excessive about the zoom. As the scene goes on, the camera zooms into a painting, computer screen, or tablet, quickening as time goes on to a highly disorienting speed. By the end of the experience, it’s hard to keep your eyes on the screen as the zoom speeds through the stationary frames, let alone try to walk around the room the character resides in.

Perhaps reaching is a lesson in why the zoom isn’t a trait often seen in videogames. For in games, we perceive the world as the character in the screen, not as an outside observer as we do in film. Since the usage of the zoom is typically controlled by the player, it’s one marred in unimportance, such as landing that Twitter-ready screenshot in a game’s glamorous Photo Mode. That is, rather than being maneuvered as a tool to increase story-driven drama. Reaching’s instead neither of these, it’s accommodating the zoom as the game’s guide, but it’s not doing so for any aesthetic or drama-driven reason. It’s exploring the mechanics of employing the art of the zoom in the first place. Perhaps, just as Hitchcock intended, as we peered down that windy staircase and felt vertigo that very first time.

Download reaching for free on itch.io , available for PC, Mac, or Linux.

Secrets sit behind the devilish sound puzzles of Told No One

“You told no one, right?” This is the language we use when speaking of secrets. Something was found out and it must be kept as unknown as possible. It’s telling that Karachi-based artist NAWKSH uses these words to title his videogame Told No One. For it seems to be a tightly woven secret itself. It’s hiding something, perhaps many things, beyond the arcane rituals it tests you with.

From the outside, Told No One seems simple enough. The description reads: “five short sound puzzles / interactive experiments in greyscale.” Sounds quite pleasant. But once you head inside it’s immediately clear that something else is going on. Something potentially sinister. It assaults you with a screen of harsh noise. Your immediate reaction will probably be to click on it and hope it goes away, and it will. But if you endure it for a few seconds a face appears, traced lightly in the static, staring you out from the other side of this hostile surface as if this were a video call (with terrible signal) made to threaten you. Who is that?

sounding like a computer error stuck in the throes of death

You’ll ask a lot of questions as you play through Told No One. Even when you get an answer you may not recognize it. The puzzles are like that: wordless, lo-fi, slow to fade out when solved. The first turns your computer mouse into a microphone. With it, you’re able to move over a large spinning occult symbol. If anything, this symbol resembles the satanic zodiac (this one), with the line art in the middle morphing into a pentagram, moons orbiting the largest circumference as they go through their cycle. Each of the geometric shapes are assigned a sound and you can spot them with your mouse. Something here will take you to the next puzzle if you listen close enough.

Told No One requires quite a lot of you. Not only patience but determination. It gives little clue as to what it wants you to do. In one puzzle you need to spin a circle that seems to rewind and fast-forward the background as if it were the plastic reel of a cassette tape. Not only does the speed change, but the chaos does too, with everything on the screen vibrating, turning into glitch-noise, it all sounding like a computer error stuck in the throes of death. It’s actually quite exhausting—the puzzle being akin to slowly dunking your head in a bucket of acid and then taking it out again.

The biggest mystery of Told No One is at its end, once you’re through the puzzles. You’ll get to select from a number of circles that take you to what seems to be a short video clip of the door frame of a house, or a street turned upside-down and viewed from the window of a moving car. There are more. It’s like you’re glimpsing into someone else’s life, as if this were the secret the game was hiding, and the puzzles beforehand were only there for you to prove yourself worthy of being let in on it.

At the start of the game, you were being looked upon by a distant viewer, now it seems you have swapped roles. What was unknown is now known. I suppose you must tell no one.

You can download Told No One on NAWKSH’s website and itch.io. NAWKSH also produces music and shares it on Soundcloud.

Facial recognition lends itself to creepy digital portraits

You shouldn’t have to carry ID when you go to grab a coffee. Coffee is not a controlled substance, though it sure is wonderful (and possibly addictive). That does not stop nominally just societies from demanding that their citizens identify themselves while out and about. Inevitably, the burden of these policies is unevenly shouldered by different groups. This problem could easily solved by no longer demanding that citizens identify themselves at every turn. There are, however, two problems with such a proposal. First: Good luck getting municipal politicians and police forces to agree. Second: The elimination of identification requirements means relatively little when your body functions as an ID card in its own right.

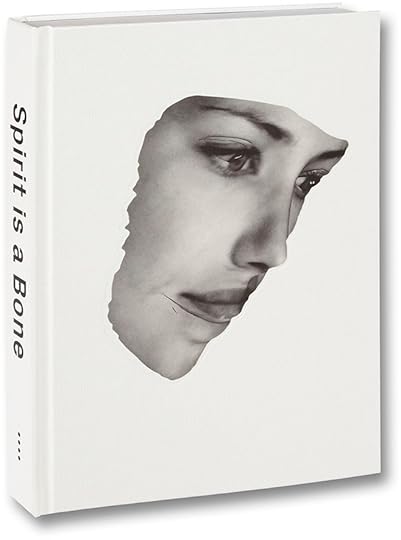

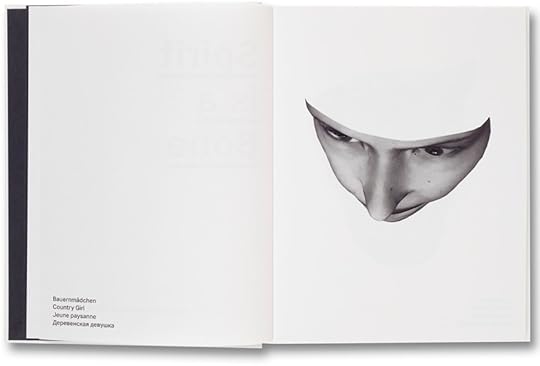

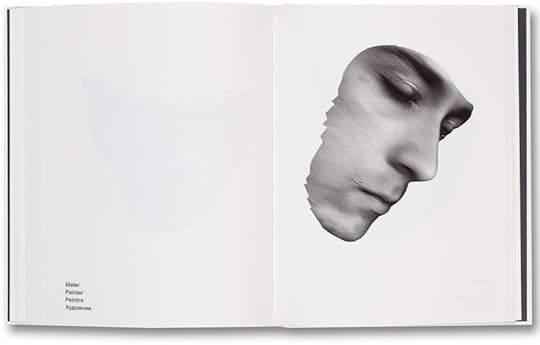

Spirit is a Bone, a new book by the artists Oliver Chanarin and Adam Broomberg, concerns itself with that second problem. It is the story of a world in which you are identified at every turn, no matter what you do, whether you like it or not. It is, in other words, roughly the story of the world in which we live. More specifically, Spirit is a Bone is about Moscow, where special cameras have been developed to capture the faces of citizens going about their lives. Chanarin and Broomberg used this technology to create the series of portraits that fill their book’s pages.

You can’t really pose for the surveillance state

The facial recognition cameras produce disembodied faces that are rendered all the more eerie by their verisimilitude. These digital masks might as well be made of human skin. If that wasn’t sufficiently unsettling, the use of surveillance technology precludes traditional compositions. You can’t really pose for the surveillance state; it finds your face and recreates it as if you were looking directly into the camera. The photos emphasize the subject’s lack of control. This is how an apparatus sees you, not how you want to be seen. So, deal with it?

Chanarin and Broomberg write that they have sorted the subjects in their book by profession in a nod to August Sanders’ Citizens of the Twentieth Century. The German photographer’s project, which could not be finished before his death in 1964, used this taxonomy to tell the story of a society through its economic classes. Spirit is a Bone has less to do with capitalism than Sander’s work, but this structure still has a certain appeal. It suggests that information and identity is organized according to the needs and priorities of a larger apparatus as opposed to those of the individual. You have a face, but the state has that, too, and anyhow you’re just a collection of numbers.

How videogames are changing the action movie

Something strange happens with the camera at the start of Spectre (2015). The movie opens with a wide view of an elaborate Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City. We’re then shown a villain before focusing on James Bond, who starts to follow this villain. Bond and a woman then go into a hotel and he leaves her by exiting through a window onto the rooftop, where he prepares to shoot his target. It’s a standard set-up for a Bond film, but throughout all of this, the camera doesn’t seem to cut away, not once. The entire opening is presented as if it’s a single seamless shot (it’s actually several).

This opening represents a real reversal in style from the last few Bond films. In those, action and chase scenes are typically afforded hyperactive editing and camera movements, as if the camera had been tossed down a staircase. Spectre‘s long opening shot abandons this established school of editing. It belongs to a newer style of action filmmaking that’s been building on the fringes for the past decade and has now unequivocally hit the mainstream.

Spectre‘s opening shot should also be familiar to anyone who’s played a third-person videogame. The perspective is commonplace, the camera closely tracking the main character, often but not always from behind. And, in Spectre, as in almost any game, the camera itself is a gliding, mobile presence that remains unblinking in its focus. It’s evidence in the case that videogames have started showing a strong influence on cinematography beyond goofier incarnations such as CGI, tie-ins, or critically derided adaptations. Instead, the movies leading this charge across mediums are rooted in physicality and often adored by cineastes.

Recent action movies like The Raid: Redemption (2011), John Wick (2014), and Snowpiercer (2013), among others, have mimicked the visual and in some cases structural form of videogames. Some of them, like Spectre, have shown this influence through conspicuous long takes, while other hallmarks of the style include smooth, minimally obtrusive editing, strong focus on a single protagonist’s point of view, and camerawork that remains stable despite its mobility. These films have gained prominence and won critical praise not just for their style, but also for what it represents: an alternative to the currently dominant mode of action filmmaking, which Matthias Stork dubbed “chaos cinema” in a video essay for Indiewire.

You may not recognize the term, but if you’ve been to the multiplex over the summer in the last ten years, you’ve almost certainly encountered chaos cinema. Think Paul Greengrass’ Bourne films, Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, or literally anything directed by Tony Scott and especially Michael Bay. The camera seems less fluid in these movies than it does epileptic. The camera often spins in circles around its characters, with its movements cut by an endless, hyperactive rhythm of edits. Quick cuts and short shots don’t necessarily guarantee incomprehensibility, but that’s often the result for action scenes in these movies. Take Christopher Nolan’s chaos cinema standard bearer The Dark Knight (2008). The hero Batman is introduced to the audience interrupting a three-way gunfight in a parking garage. Batman’s arrival is framed a surprise, which is easy to orchestrate since we never have a clear sense of where most of the other characters are, or even how many of them there are. Despite being set mostly on a single open surface, the rapid editing that kicks in once the shooting starts means the audience never has an obvious sense of the characters’ location or movements, and the camera switches its focus quickly from one character to another.

an alternative to the currently dominant mode of action filmmaking

By contrast, the action movies that have borrowed their style from games prioritize physical clarity, rarely obscuring the movements of their characters. Around the time critics started noting the emergence of chaos cinema among blockbusters, a number of movies pushing towards arthouse or cult audiences made a splash due to their own showy approach to violence, centered around long takes. Park Chan-Wook’s 2003 film Oldboy was among the first of these. Oldboy arrived on American shores in 2004 as part of a wave of sleek new Korean films. Its assured style and revenger’s tragedy plot won it the Grand Prix at Cannes that year. Meanwhile, its presentation of violence—especially one standout single-take action scene—has made it a perennial favorite of action fans. Over the course of this one celebrated shot, actor Choi Min-sik decimates a hallway full of thugs that vastly outnumber him, continuing even with a knife stuck in his back. Sure, the rest of the film attempts to sour viewers on violence and revenge, but this scene revels in its action. Visually, it achieves this by mimicking the side-on view of beat ‘em ups like Streets of Rage (1991), making use of the singular wide angle to let us take in the entirety of the scene; a single man against an armed mob.

Prachya Pinkaew’s The Protector (2005) moved that kind of action scene into 3D the following year. Gleefully lacking any of Oldboy‘s moral complexity, the Thai action film has a plot that’s best summarized by the guy on his phone coming out of the movie theater ahead of me: “This dude has his elephant stolen and he has to kick all kinds of ass to get it back.” In the course of trying to find his elephant, Thai martial arts star Tony Jaa barges into a restaurant-cum-brothel. Camera held firmly to his back, he proceeds to head up the stairs, viciously dispatching anyone in his way as the camera spins along unblinking in his wake. Beyond the camerawork, the scene itself follows the logic of basic level design: start at the bottom, work your way up, defeating anything that tries to stop you. It’s a set-up reminiscent of Bruce Lee’s unfinished Game of Death (1972), whose simple premise, memorable style, and series of one-on-one fights would make it a major influence on fighting games and brawlers.

With 2006 came Children of Men, Alfonso Cuaron’s masterfully directed sci-fi film. While not an action film (the protagonist, played by Clive Owen, spends most of his time running away), the movie features several extended takes of its characters scrambling to escape intense violence. Children of Men depicts a future thrown into global chaos due to humanity’s unexplained inability to reproduce, and the film’s style reflects the idea of pervasive violence. Long takes are used to maintain a running level of suspense, the rarity of cuts reinforcing the idea that there’s no escape from the violent state of the world. Particularly during an anti-government uprising toward the end of the film, the camera follows behind its main characters while occasionally turning away from them to demonstrate that the situation they’re caught in extends far beyond just them. Watching it upon its release reminded me of playing through particularly busy, tense portions of first-person shooters like Half-Life 2 (2004) or the Call of Duty series (starting 2003), both of which took pains to make the player feel like she was one person taking part in a larger struggle. Children of Men required a similar endurance from its viewer.

It’s easy to forget now, but the visual language of 3D games has only recently been established. This was more of a problem with third-person games than first-person ones. Even an 8-bit game like Sweet Home (1989) could switch from a top-down 2D view of its characters to a frontal view of the monsters they encountered and expect players to assume that they were now seeing what the characters saw. For 3D games, though, the third person perspective was more complicated. The first Resident Evil (1996), a 3D third-person game inspired by Sweet Home, relied on static shots of rooms with no controllable camera movement. The series eventually switched to a behind-the-character perspective with Resident Evil 4 in 2005. Notably, the games that could best make players feel like they were intuitively and effectively moving through 3D space were often described in terms of movies. Even a game like Half-Life 2, which was played entirely from the first-person perspective with no cutscenes, attracted constant movie comparisons. Reviews from the time mentioned its “cinematic moments,” “cinematic presentation,” “cinematic set pieces,” and “filmic ambition.”

directors can express a game-like sense of seamlessness without one-take shots

As the vernacular was established around 3D games, with certain camera styles and control schemes solidifying as genres, more filmmakers were picking up on the value of bringing the unique language of videogames to amplify the impact of their action scenes. The 2005 Doom adaptation included several action scenes shot almost jarringly from the first-person perspective, distinguishing an otherwise forgettable movie. The Crank films, meanwhile, featured a hyperactive style that was the complete opposite of a film like Children of Men—in Crank 2 (2009) there’s literally a title card between cuts that says “9 seconds later”—but was frantic enough in its individual beats for it to play out like a non-stop five-star crime spree in Grand Theft Auto. The rise of this style in movies was enabled by more than the zeitgeist, with advances in cinematic technology also playing a role. Digital video and the Steadicam reduced the cost of filming and enabled greater camera mobility. As early as 1992, John Woo staged an extended single-take action scene in Hard-Boiled, but no wave of imitators sprang up in its wake. Now, long-take action scenes seem to appear regularly.

More recent films have also shown that directors can express a game-like sense of seamlessness without one-take shots. 2011’s The Raid: Redemption coupled tight, brutal fight choreography with editing meant to reveal the action smoothly and comprehensively. Watching its characters fight their way through the film’s dingy hallways feels a world apart from the overcharged editing of The Dark Knight. The action scenes make use of some quick cuts, but the camera usually remains focused on a single character at a time. When the camera does cut, it’s often to follow the character’s movements or gaze, making the editing less obvious. In addition, The Raid once again featured that level design-like setup of working your way up from the bottom of a building to defeat the nemesis at the top.

John Wick also boasted a clear use of space and smooth, choreographed sense of action; watching scenes from it or The Raid sometimes feels like seeing someone accomplish a speed run through videogame fight scenes with real actors. John Hyams’ 2012 surprise cult favorite Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning uses strobe lights, cryptic dialogue, and a droning soundtrack to frame the action movie as a fever dream, but still presents its fights with similar lucidity and continuity. Bong Joon-Ho’s 2013 film Snowpiercer took the game-like environmental focus the furthest, set entirely on a train with a rebellion trying to move from the back to the front, often framed yet again as left to right. In an interview with Under the Radar, Bong disavowed any direct videogame influences, but noted that Snowpiercer‘s progressive structure and sense of perspective limited to its protagonist are similar to games.

films drawing their style from videogames embodies an alternative

Both fans and movie studios eager to market their films have drawn parallels between these movies and games. You can download John Wick as a character for Payday 2, play an 8-bit fan tribute to the Oldboy tracking shot, or watch The Protector‘s single-shot fight scene dubbed with videogame audio. These game-like movies have also drawn positive reviews, especially for how they broke with the mainstream mode of action filmmaking. John Wick has not one but two reviews in The Atlantic lauding it for not being another “lazily cut shaky-cam action movie,” Vulture’s Bilge Ebiri praises Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning for its “spatial logic that’s all but disappeared from action moviemaking,” and The Guardian declares that The Raid: Redemption “puts western action movies to shame.”

The kinetic editing of chaos cinema may have been exciting, but a decade-plus of Fast & Furious and Transformers movies has been more than enough to create a critical backlash to the style. If the original joy of the action movie was bodies in motion—per the common comparison of kung fu films to musicals—then chaos cinema has erased that in favor of nothing more than sound and fury. The proliferation of films drawing their style from videogames embodies an alternative. Which brings us back to that opening in Spectre. It felt like a new statement of purpose for the Bond series, and it isn’t the only film indicating that a style once relegated to smaller cult movies is now having a wider effect. Netflix’s series Daredevil (2015) channeled Oldboy with its own one-take action scene set in yet another dingy hallway. Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015), meanwhile, presents one of its critical boxing scenes as a long, uncut take. When film critics say that movies resemble videogames, it’s usually a curmudgeonly complaint. It shouldn’t be. Instead, with their focus on nimble achievement, spacing, and smooth, comprehensible visuals, games have brought the action movie back to its roots. Formally speaking, action movies really are coming to be more like videogames. They’re all the better for it.

Dangerous Golf wields destruction as a middle finger to the rich

Golf is the sport for people with far too much time and money. The average length of one round is 4 hours; the average golf course is so large, there’s a particular vehicle designed to carry you across the field of play. Its archetypal depiction, in the collective human unconscious, will eternally be an old white man with a sun-visor and a cigar, making someone else carry his clubs from hole to hole. Golf is the sport of the one percent.

why not turn anything into a golf course?

Maybe it’s golf’s status as an activity of the elite that makes bending it towards destruction such an enjoyable concept. Your goal, in the recently announced Dangerous Golf, is to cause as much property damage, in dollars, as possible. “Smash a priceless chandelier,” reads the website for Dangerous Golf. “Destroy a kitchen full of china!” Satisfy that urge you get to obliterate the wealth gap, implies Three Fields Entertainment. Fuck the rich, I’m pretty sure is implicit. One of the three images we’ve seen so far includes a white marble bust shattering to pieces as a red-hot golf ball bursts from its chest like an alien parasite. Marx predicted as much when he said “The weapons with which the bourgeoisie felled feudalism to the ground are now turned against the bourgeoisie itself.”

This proletariat theming carries over into the course design for Dangerous Golf. Most golf courses require a horrific amount of water to remain lush and green. In California, the Natural Resource Defense Council estimated that “an average Palm Springs golf course uses the same amount of water in one day that a family of four uses in one year.” Rather than take water from the thirsty mouths of the lower classes, why not turn anything into a golf course? Courses described by Three Fields Entertainment so far include a medieval castle, which seems pretty difficult to mess up, and a fancy ballroom, which seems less so. Best of all, fight back against the overpowering greed of the oil industry by blowing a gas station the fuck up.

While Dangerous Golf will be the studio’s first game, founders Alex Ward and Fiona Sperry have a pedigree in destruction. Black (2005), which they made while leading Critereon Games, was a first-person shooter which was mainly about how cool all the guns sounded. Burnout (2001), a game about smashing beautiful cars into flaming hunks of slag, was the beginning of their experimentation with wealth destruction. Look forward to their latest entry into the genre in May of this year.

The Spaceteam card game will make you wanna shout

“The future is disorder.” –Tom Stoppard, Arcadia

///

The Spaceteam card game is chaos. Like its forebear on Android and Apple, it’s a cooperative game that forces you and some friends to scramble with tools and ailing apparatuses to fix your spaceship before you are swallowed by a black hole. As an adaptation, it’s faithful to the frenetic shouting of the original Spaceteam (2012), which was itself a faithful homage to the technobabble of Star Trek and giant-mecha sci-fi films. Instead of a digital interface, this iteration replaces it with cards and a timer, which are easier to wipe clean of beer stains. Better still, the components and box sport a crisp visual flare, popping with bright colors and symbols.

Spaceteam is among the first app store-to-tabletop games: a fact that attests to the challenge of its translation. To manage the process, designers Matthew Sisson and Tommy West clearly drew from their past in designing escape rooms, making a distinct imprint on the experience of the Spaceteam card game, which is engineered for maximum adrenaline rush.

The mechanics are simple: three to six players (nine, with expansion) flip over and resolve separate malfunction decks as they dig for six Systems Go cards that signify victory. Every other card represents some kind of malfunction or anomaly, some system gone awry. To solve a malfunction, slap down the right combo of tools and then draw the next card. The catch is that no one has the right tools and everyone is shouting for what they need at the same time, because a single game only lasts five minutes.

a game about organizing chaos

It’s a hectic and purposefully broken game. The card design engenders incompetence: a malfunction might specify its tool by name, or by picture, or by any of five inscrutable types. The game is best summed up in the following transcript of a game I played the other night:

“I need a Rotomist Container.”

“Does anyone have a purple whisk-looking thing and, like, a sun tool? It’s a sun-type tool. Looks like a sun.”

“I need an electric-type tool! Does anyone have an electric type tool?”

“Steve, pass this to Lee.”

“I still need a Rotomist Container! Does anyone have a Rotomist Container! Also, give this to Brent.”

“Here, Brent. I need, like, a blow torch! It’s a yellow blow torch! Thanks, Kit! Aw, yeah! ENGINE SYSTEMS 2 ARE GO!”

“Two sparklies! I need two sparklies and a space dildo!”

“GUYS, I NEED A ROTOMIST CONTAINER”

“WORMHOLE! EVERYONE SWITCH SEATS!”

“Navigation Systems are go!”

“I need that space dildo!”

“GUYS I STILL NEED A ROTOMIST CONTAINER”

Everything happens at lightning speed, colored by the group personality and fueled by the five-minute timer. Anyone can be panicked and loud for just five minutes. This core concept—shouting for parts—is what makes it so compulsively playable. It’s a game that is destined to be unboxed at parties and tutored under the influence of alcohol, caffeine, or whatever you happen to be smoking at the time. The adrenaline-soaked shouting matches it encourages are what make it ideal for breaking the ice with new people.

The problem with Spaceteam is that it cannot last much beyond that initial encounter among strangers. And how it instigates the shouting that defines it is where its strengths deteriorate into weaknesses. It is undoubtedly a game about organizing chaos. Each game includes a few rogue anomaly cards, which add some unique flavor. The “Man Overboard” anomaly mandates players to physically pull back another player before they can continue playing, while the “Robot” anomaly forces a player to finish the game without using their thumbs. However, most of the chaotic interplay comes from unfamiliarity, from not knowing what a symbol means or even what the five obtusely labeled tool subtypes mean. The point of the game is to be broken, for players to be inundated with unfamiliar symbols and technology. Knowing the game makes it less interesting, and embarrassingly easy. What happens when a group of players knows the game so well that they can tell the Slime Discpistion requires the Contracting Propeller, Quasipaddle and Duotronic Capacitor? The designers’ solution seems to be inflation.

My friends and I slotted in the “Not Safe For Space” expansion: an array of toilet and sex-themed tools and numerous scatological and drug-themed malfunctions. Space-bongs, stellar dildos, mushroom anomalies that prompt a “Woah, man!” for every card flipped. The new cards make the game less manageable, but not markedly different. According to the web store, there are two more expansions available or forthcoming, and if the game sells well, we can surely expect many more in the future. Yet these new components only muddle the game’s already-clunky system.

There’s nothing deeper at play in Spaceteam: it’s fast, idiotic fun. It’s the type of game that begs to be played at parties and incorporated into drinking games. It occupies the accessible yet slightly edgy segment of games like Cards Against Humanity and Exploding Kittens. For all the chaos and urgency it induces, this adaptation can’t quite approximate the cracked consoles and trashy madness of its app forebear.

The Spaceteam card game is available to purchase on Amazon.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

February 4, 2016

Solitaries will have you dreaming of concrete

How much does concrete weigh?

This is, on the one hand, an insultingly simple question. Take some concrete. Put it on a scale. Record the weight. Multiply by some larger number if you’re using a sample. There you have it: concrete’s weight. It’s not really a mystery.

But it’s not that easy. There’s the not insignificant matter of heft. Concrete, by dint of the way it is used, can come to feel heavy or miraculously lightweight. This is the sort of sensation that cannot adequately be calculated with a scale. You have to experience it, and that’s where Solitaries, a procedural game created by Ivan Notaros for the Screensaver Jam, comes in.

it’ll have you dreaming of concrete

There’s nothing to do in Solitaries, and that’s just fine, thank you very much. You float through a grey world filled with polygonal structures. There are tall towers made of concrete and mirrored glass. Small, blockier structures are sprinkled around the towers like a bad parsley garnish at thanksgiving. Float around for a little bit. Take in the buildings. Take in the sky. In grayscale it appears to be made of the same material as the buildings and the ground. Maybe that’s why it all feels so weightless.

For a material associated with permanence, concrete is in need of periodic resurgences. (One might well ask where it goes between these resurgences.) So why the latest resurgence of the ancient material? In a recent essay about Christopher Beanland’s book, Concrete Concept, The Telegraph’s Liz Hoggard, herself a recent convert to brutalism notes:

“Beanland believes our concrete nostalgia is a protest against the greed of the current housing market, with cities like London being bought up by the international super-rich. ‘The 21st-century reappraisal of brutalism is partly an attempt to re-invoke pre-1979 values of social democracy – even though the ‘democracy’ wasn’t necessarily all it was cracked up to be.'”

Solitaries is democratic. All its spaces, procedural though they may be, are for you. It’s not exactly a utopian vision, but it’ll have you dreaming of concrete.

You can download Solitaries on itch.io.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers