Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 170

January 27, 2016

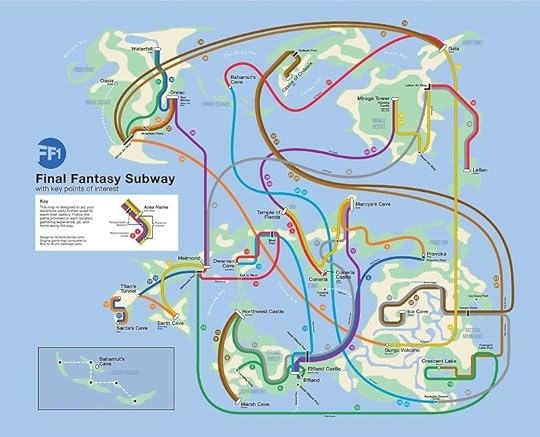

Classic videogame worlds reimagined as subway maps

Few moments are more familiar in an old-school dungeon-crawler than the opening of a treasure chest, only to find a dungeon map. But if—for whatever whim of your fancy—you’ve been hoping instead for a subway map to unfold itself from those chests, you’re in luck: graphic designer Matthew Stevenson has created six sprawling “subway” maps, based on his favorite NES games.

revel in these maps’ ability to evoke warm nostalgia

Each map is unique, encompassing the specific visual appeal of the game they seek to compress. The Legend of Zelda (1986) subway map, for example, is intricate and sprawling—based loosely on the London Tube—reminiscent of the hours spent riding through Hyrule Field. The map based on Metroid (1986), however, is blocky and bold in color as though it were an interpretation of Samus’s Power Suit. Stevenson didn’t miss any of the classic heavy hitters; he has also designed subway maps based on Final Fantasy (1987), Dragon Warrior (1986), Maniac Mansion (1987), and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (1987), all loosely based on real-world subway systems.

What is perhaps most impressive about these designs is how they reimagine entire videogame worlds as simplified one-dimensional spaces, yet retain a strange sense of familiarity: these are the worlds you know and love, only more abstract and sophisticated. One can hang them in their office and revel in these maps’ ability to evoke warm nostalgia for classic Nintendo in a minimalistic way, and perhaps feel inspired to revisit those beloved worlds.

You can see all of Matthew Stevenson’s videogame subway maps over on Red Bubble.

Nuclear Throne is hotter than a smoking gun

For a game that has zero puzzle elements Nuclear Throne sure feels like a seeing-eye puzzle. If I keep at it long enough I will eventually see the fire truck or star or whatever image it is hiding. There’s a sense that if I stay with it one more turn I’ll land on a magic run that sends me to the eponymous Nuclear Throne where I’ll be a king of the wasteland, like Immortan Joe, or anyone more flattering.

The Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) comparison goes more than skin deep. The world of Nuclear Throne is overrun with bandits and the primary solution to them is bullets. Every problem is an invitation to shoot your way to victory and, barring that, bludgeon your way to success. Aside from the fact you play as a mutated plant/fish/crystal/chicken, Nuclear Throne is as straightforward as one could get. Any obstacle is a point and click away from being a bouncing corpse.

the antithesis of so many other shooters

The beauty of Nuclear Throne is that it is very much the antithesis of so many other shooters. It does away with many of the modern trappings that clutters up the genre today. There is no in-game currency, no cosmetic upgrades, no online matchmaking or versus modes. There are actually very few features at all. You select a character and are immediately dropped into a wasteland where you do battle with scorpions and bandits, armed with only your trusty revolver, and any other weapon you might be lucky enough to find tucked away in a random chest. With a driving anthem at your back you’re left alone to do battle and reach the Nuclear Throne. It’s simple: a game that proves the best sugar comes from sugar canes and that the formula needn’t be more complicated than that.

Out of this reductionist approach comes a focus, pure and distilled: gunfire. All of Vlambeer’s games primarily revolve around using a barrage of bullets to progress, but with Nuclear Throne the studio has tweaked gunfeel and everything that informs it to a master level. Pressing a key moves my character, moving the mouse aims, and clicking the mouse produces a bullet, and hopefully that bullet goes into the world and kills something. But instead of feeling mechanical or dry, the launch of these bullets produces the same joy as the first bite of a hot, flaky pastry or a delicious slice of pizza. In general, of course, we expect outputs to accurately match inputs. The difference is that Vlambeer does more than simply execute on this expectation. They infuse those outputs with a little something extra, something onomatopoeic, something loud.

When I click the fire button my little revolver lets out an oversized boom. When I stab a bandit with a screwdriver there’s a Wolverine style “snikt” that accompanies it. Grenades fire with a characteristic THOOM and give off an almost too satisfying BOOM when they explode. The accompanying damage to the enemies and landscape makes it feel like my little mouse click has a weight and girth to it. This is exactly what Vlambeer’s Jan Willem Nijman said that his games do extremely well at the 2013 Netherlands’ Festival of Games, and he’s right. Not just sound and visual design, but creating a connection between several different game elements in a way that is supremely satisfying. To Nijman, the game is more than what is on screen or beneath my fingers. The game really exists in a third space, bordered by my inputs and the outputs they feed me. This third space might be deemed a secret ingredient, akin to a special sauce only able to be produced via a strange South American pepper. Except in Nuclear Throne it is not a singular component that achieves this, but an entire recipe of tiny effects stacked up to drive that gunshot from your finger, into your eyes, quickly engulfing your brain. The screen rattles at the explosions abound. The oversized bullets are joyous to watch as they cut through maggots and rats. And there’s a tangible sense of impact on its world when you blast an enemy and send its corpse careening through a mob. All of this is punctuated by big booms of cars and barrels, the aggressive thumps of a machine gun or the PEW PEWs of a laser pistol. Vlambeer is wildly successful in blending all of this together to furnish that elusive third space into one that is enticing enough that I keep coming back no matter how poorly I play. It is entirely a sensory experience, yet what I get out of it is more than what it shoots into my eyes or ears.

“point, click, BOOM” in its most distilled form

Nuclear Throne feels like a game that pushes laterally against time. As though it is responding precisely against the teleological push towards the realistic portrayal of guns seen among its peers. Vlambeer manages this by blowing up the most satisfying features of ballistics towards an arcade-informed absurdity. All this is to say that Nuclear Throne is for purists to feel the joy of “point, click, BOOM” in its most distilled form. It’s a shooter that wants to be best at moving and shooting first while fully knowing that true satisfaction in those elements comes from the way moving and shooting feel.

“Purity” in no way means sparse or drab. Purity can be strangely complicated. Each of the representated elements needs, and does make the game better. No one would accuse Hemingway’s fabled six-word story of lacking nuance. In fact, exactly like that mythical six-word story, Vlambeer succeeds by forging a connection between the player and the game. A mastercraft level of audio-visual responsiveness in every bullet fired keeps every successive shot as satisfying as the first one.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

January 26, 2016

Against the illusory architecture of Half-Life 2

In “On Dérive,” the titular act is explained through text and your own movements through a virtual environment. To dérive (to drift), is to let yourself wander through the city with no prior aim or destination in mind; a spontaneous journey through the urban stage. The point of it is to demonstrate the specific design of a city, how its deliberate topography affects us subconsciously to guide us down certain paths, or as French writer and theorist Guy Debord puts it: “cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vertexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.”

The On Dérive demo, created by David Cribb (aka Colestia), starts by quoting Debord and then throwing you into a boxy space in which you are constantly moving forward. You steer through a small portion of towers and alleys, enacting dérive without a choice, and eventually arrive at a red box stood lonesome in an open space. Then comes the revelation: Without realizing it, you took the path of least resistance, all due to the shape and angles of the architecture and the way it carves light. After another quotation, this time from philosopher Sadie Plant—which ends, “seek out reasons for movements other than those for which an environment was designed”—you return to the same space but this time have full control. You only move forward when you want to. The sense of urgency gone, you can properly explore, and in doing so will discover other channels you could have walked down. You resist the manufactured design of the city and, like the bubbling stream carving its own path away from the flow of the river, trickle into a maze of narrow passages that eventually lead to a green box. End.

///

Upon encountering Situationist ideas in Guy Debord’s 1967 book The Society of the Spectacle, David Cribb almost immediately thought of it in relation to contemporary game design. The similarity that most struck Cribb was in how both groups have enacted considerable study into how seemingly organic movement can be subtly controlled. “For the Situationists, the purpose of this analysis was uncovering (and undoing) the political structures behind the control,” says Cribb. “For game designers, the purpose was guiding the player towards important areas while maintaining an illusion of freedom of movement.”

actively work against the techniques employed by Valve

One game stood out in particular when picking apart these thoughts. Half-Life 2 (2004) and especially the clustered low-rises of its City 17 constantly come up as the masterwork in guiding players through an environment without shoving them around with waypoint markers, mini-maps, or camera-yanking cutscenes. This is something that game designer Matthew Gallant has written about in his article “Guiding The Player’s Eye,” in which he reveals how Valve subtly help players navigate Half-Life 2‘s environment through flocks of birds, ammo crates, and graffiti—”elements that fit seamlessly into the game world.”

This similarity became the starting point for a videogame project that would encourage players to actively work against the techniques employed by Valve and its many protégés. The invisible traces of a designer’s hand that guide people and players through urban spaces tossed out into the street to find a truer form of exploration. And this illusion would be broken down in a virtual metropolis called New Lethes.

///

New Lethes is the bigger project for which On Dérive serves as a type of demo. Both of these are first-person exploration games that view the city through elements of Situationist theory. But whereas On Dérive can be considered the lesson, New Lethes is the essay you sit in order to pass the subject. It takes place in the fictional city of its namesake, the most notable feature of which is the large pathway running through its middle, a busy canal of commuters constantly walking through. This large and obvious path has many small offshoots on either side of it but no one wanders them. You should know where this is going.

But to fully understand what New Lethes is getting at you first need to know a little about Situationist thought. The guy quoted at the top of this article, Debord, is one of the movement’s most important members. Branching off from Marxist theories, Debord wrote about how the city is an environment built to keep order and control, especially over the proletariat. This was part of Debord’s larger argument that capitalist society had bred a form of social alienation among people in which they are treated as passive objects; told what to do, what to desire, ever-consuming products that they didn’t need. To get out of this boring rut of existence, Debord and the Situationists suggested and acted out détournement (“rerouting” or “hijacking”). Whereas capitalism employed “recuperation” to channel social revolution and working class resistance back into into its own power structure—punk rock clothes being sold in boutiques, for example—the Situationists aimed to reinvent the everyday to jolt people out of their routines. Strikes and vandalism in public spaces, sabotaging the images of capitalism, all of this was incited by Situationist thought, going on to inform the May 1968 uprisings in France.

wander the path of most resistance.

The architecture of the city was targeted by the Situationists as a prevalent means by which capitalism held a grip over people. As On Dérive demonstrated, it can be used to steer us physically through spaces, acting as a singular mass of singular thought—all of us easy to control and manipulate in service of the elite. This is what you see when New Lethes opens up, all those people walking the same path, dull and grey. In order to turn “the whole of life into an exciting game” the Situationists worked against what dérive exposed, and so must you in New Lethes, with a view to aimlessly wander the tiny labyrinth of city streets that no one else does. You must deliberately work against designs supposedly greater than you. You must dare to get lost.

It’s in this exploration that you discover the truth of this city. In mimicry of John Carpenter’s They Live (1989), there are a pair of glasses you can find that reveal words such as “BOREDOM” and “TIRED” spread across the city in huge font, invisible to anyone but the glasses-wearer. This is only one of the significant events to be found within the urban sprawl of New Lethes and probably the most unoriginal one. As day passes to night, you will see riots break out in the streets, and later there will be subterranean surprises providing you wander the path of most resistance. Eventually, you will work your way to some other space separate of the city where you can move like a ghost through enormous skyscrapers that assert a terrifying authority at you—they scream at you without mouths. When you have performed this act of ultimate defiance against the controlling architecture of real and virtual spaces (daring to fall into the void behind them), you will discover that, at last, you have beaten the system.

You can purchase New Lethes on itch.io. The On Dérive is demo is free to download on the same page.

Waiting in the Sky recreates a universal childhood experience

I don’t remember many of the places I was taken to between the ages of two to 10, but there is a sort of coalesced impression I have of the many backseats windows I saw the world through. That window is always safety-locked, for one, and won’t roll down past half-way. Usually, it’s raining outside, and I’ve sketched out little monsters in the condensation.

Waiting in the Sky puts you in a similar backseat, the one from all your childhood memories. Instead of doodling on the fogged-over glass, you’re making constellations out of the stars. The celestial bodies are randomly laid out each time, and while some of my creations (striped horn-snake, hourglass tied to a balloon) could be called stretches of the imagination, stretching imagination is what kids do best.

moments like this were solitary experiences

Waiting in the Sky was originally made by Luis Díaz Peralta, Rubén Calles, and Celer Gutiérrez Dávila, for LocusJam—an event hosted by the inimitable game designer Porpentine. The goal was to make games that captured specific places and feelings, and when measured under those criteria, Waiting in the Sky is unarguably successful. It isn’t just the art and theme of the game that creates such a vivid moment in time, either—if nostalgia could be put into music, it would surely have the same bittersweet piano notes, the strings plucked like raindrops.

The ability to share your constellations on Twitter is built right in, but I refrained from doing so. It wasn’t out of any sort of artistic embarrassment, though; in my recollection, moments like this were solitary experiences. There are, after all, no others present in Waiting in the Sky, no suggestion of radio or travel-chatter. It’s just you, the stars, and the pixelated countryside rolling by in shades of night-time blue. Cottages with warm yellow windows dot the hills. Street lamps illuminate brief stretches of road. Highway signs, in all likelihood, point home.

INFRA asks what you’d do to stop an urban crisis

In the face of professional pressures, the profit motive, and a basic desire to survive, what can average citizens expect of the poor souls who inspect public infrastructure?

This unfortunately timely question is at the heart of Loiste Interactive’s INFRA, which is out now for Windows. You play as an engineer tasked with examining the structures in the city of Stalburg. You are competent though not exceptionally motivated. This is a job, not a crusade. While carrying out your professional duties, however, there are some things you can’t help but notice. Namely, the whole city’s going to shit. Structures are crumbling and if nobody’s been harmed yet, it’s only a matter of time until everyone’s luck runs out.

There is a relatively clear solution to this problem: fixing these structures. But talk of solutions is softer and more malleable than the relatively concrete question of whether a piece of infrastructure is deficient. Problem solving is less binary than the engineer’s evaluation. Indeed, while attempting to complete routine inspections, INFRA’s protagonist tumbles into a world of intrigue. Stalburg’s infrastructure is only in its current decrepit state because of political decisions (isn’t that always the case?), which means structurally unsound buildings aren’t the only things you have to fear or run from.

This is a job, not a crusade.

Games are not easily made. They take time to produce. Consequently, developers can hardly be expected to anticipate the exact context in which their game emerges. Timing is everything, but also uncontrollable. INFRA, for instance, came out the same week that the unacceptable condition of the drinking water in Flint, Michigan, came to light. In a sense, this was not news. Flint had switched its water source from Lake Michigan to the Flint River in 2014. “”We go from the freshest, deepest, coldest source of fresh water in North America, the Great Lakes, and we switch to the Flint River, which, historically, was an industrial sewer,” the area’s congressman, Rep. Dan Kildee, told Rolling Stone’s Stephen Rodrick. Like far too many urban tragedies, Flint’s was long gestating, reasonably foreseeable, and largely avoidable. But it is now news. A state of emergency was declared on January 16, which is meant to speed up measures that will address the dangerous lead levels in the city’s drinking water. The state of emergency was declared just 24 hours after INFRA’s release.

Both the game and the situation in Flint raise questions about what can be expected in these sorts of situations. “Over the winter, e-mails obtained through FOIA requests…revealed that the problem with Flint’s water could have been addressed months earlier if the state hadn’t ignored red flags raised by administration officials,” Rodrick reports. The situation in Flint was not a complete mystery. Therein lies much of its tragedy. Yet warnings were ignored. So what was to be done? The videogame world of INFRA leaves open the possibility of action. Its narrative is structured in a way that suggests a lowly functionary, despite being at a disadvantage, might indeed take on the system. That conceit is necessary for a videogame like INFRA to work. With respect to the efforts of functionaries who did note the problem, that conceit is sadly far too fictional.

You can purchase INFRA on Steam right now.

Fabulous Beasts makes the toy game physical again

Before there was anything else in this world, there was Bear. Bear was the perfect creature to start off a fresh new ecosystem: big and burly, with a stable base of four flat feet. His back, though hunched over in an arch, was unmovable. And so my quest to create a fabulous world of colors and fauna and water and flame would begin here, with Bear.

Only moments later, as Eagle and Hippo and Fire and Water tumbled off Bear’s back onto the linoleum floor of a New York City cafe, did I realize how wrong I’d been. But no matter: I picked up the pieces and started again.

\\\

Videogames have always suffered from a propensity to show rather than tell, so they’ve never been great at sparking the imagination. Even though World of Warcraft is pretty much Dungeons and Dragons brought to digital life, for instance, it’s rigid in the ways you can interact with it. The details of the in-game world can never be anything more than what’s placed directly in front of you. For this reason, I’ve always tried to strike a balance between virtual worlds and tabletop-based adventures that rely on abstracted ideas, leaving space for creative problem-solving and open-ended visions.

Fabulous Beasts, from UK-based hardware/game studio Sensible Object, is a wonderfully eccentric attempt to try and mesh the imagination of physical games with the satisfaction of watching these things come to life in digital spaces. This is a genre that’s already picked up steam in the form of toy-based games like Skylanders and Lego Dimensions, but Fabulous Beasts rests more comfortably in the physical world.

Ostensibly, this is a stacking game that works like a sort of reverse Jenga, where players work together to stack modeled shapes as high as they can atop a small circular platform. But the game isn’t necessarily about stacking. Before each turn, players scan the piece they’re about to play via a reader at the base of the platform. When they’ve securely placed their piece atop the stack (careful now), it shows up on the connected iPad as a digital facsimile of itself. If I get Bear to stay on the platform, Bear shows up on the iPad screen. Knock over the pieces, and you lose.

the balance of your ecosystem becomes more tenuous

The twist comes with the game’s imaginative scoring system. Many pieces included with the set aren’t creatures, but special modifier shapes that will increase or alter the “Fabulousness” (score) of the world (stack) you’ve created. The logic behind these mechanics is always some quirky flight of fancy, for instance: When you’ve populated your world with multiple beasts, they start to become jealous of one another, and players have to use special pieces—like the elemental blocks of fire and water—to bring balance and Fabulousness back into the ecosystem. Other pieces serve as multipliers, and require players to accomplish specific tasks on the iPad as they play the next round. If you thought it was hard enough to balance an egg-shaped object on top of a curved arch, try doing it with one hand.

One game of this and it becomes pretty clear how deep the rabbit hole goes. The provided models are complex, with swoops and spirals and asymmetries that make each placement a challenge. Without some practice, it’s tough to tell which pieces might fit well with one another, much less to place them in an order that optimizes stacking potential. But I find that the difficulty actually adds to the game’s theme. As you build your stack ever higher, the balance of your ecosystem becomes more tenuous—both in the complexity you’re seeing on screen, and in the terrifying anticipation that starts to permeate each turn. It’s tough to be a god, but as you start to synthesize strange new creatures and one-off biospheres, it feels uniquely rewarding, like a kind of strange, delicate synthesis.

\\\

Bear is not a very good creature to start out with, at least not in the way I thought he’d be. When he stands on all fours, Bear is cocky and selfish, stealing all the platform space for himself and making it tough for other creatures who need a firm foundation to stand on. But flip Bear over, and his feet stick out to create a perfectly balanced stage. This humble, more thoughtful version of Bear is a meek and altruistic creature. Instead of roaring at the other beasts, he welcomes them, embracing the fabulousness of his world. And although he’s no different than the model I’d placed just minutes ago, I could swear I’m using a brand new piece entirely.

Fabulous Beasts is currently in development, and you can now support it on Kickstarter.

Playing Paris like a game

I have never been to Paris. In my provincial life I’ve never even left the United States. Despite or, perhaps, due to my localism, I was beguiled by the vision of the city given by Luc Sante in his 2015 book The Other Paris. Sante provides an underground history of the city, of its crime and prostitution, its low-wage work and lowbrow entertainments, its intoxications and insurrections.

As fluent as he is with tales of murderous gangsters and wayward streetwalkers, what really comes across in The Other Paris is Sante’s deep mourning for the lost topography of the city. The book hinges on the two waves of urban reform (one in the 1850s, the other in the 1960s) that swept through and sanitized much of the city into “monolithic high rises with all the charm of industrial air-conditioning units.” These urban reforms turned parts of Paris from warrens of alleys and passages (as in Les Miserables) into over planned boulevards (as in every romantic comedy ever set in Paris).

Sante clearly has a deep appreciation for a Paris-based movement called the Lettrists. They were a Marx-inclined offshoot of the Surrealists, active in the mid-1950s. Sante characterizes the intellectual project of Guy Debord, the Lettrists’ ostensible leader, as “serious dissipation, seriously intended and seriously pursued, which combined pleasure, poverty, chance, sex, disputation, wandering, and the self-conscious theatre of youth.” The Lettrists’ central practice was the dérive, or drift, which took the form of extended wanderings through the streets of Paris to chart the “psychogeography” of the city. They divided Paris up into “ambiance units” which, due to subjective factors like “an effect of light and shadow or an imbalance of scale or a pattern of commerce,” seemed to leave a fleeting emotional trace. The Lettrists wanted to open themselves up to all the contingencies and chances that made such an emotional trace perceptible; in essence, to become expert players of Paris as a kind of game.

what really comes across is Sante’s deep mourning for the lost topography of the city

It was by chance that I was reading The Other Paris at the same time as playing last year’s Fallout 4. In doing so, the bearing that Sante’s and the Lettrists’ ideas have on open-world gaming became clear to me

Open-world games are, on one level, founded on a principle of dérive, of wandering and soaking up the variety of their landscapes. Playing Fallout 4, I spent the majority of a couple days touring the vicinity of the Commonwealth crater, for no particular end but to experience the psychogeography of that noxious and shattered landscape. The whole game is constructed out of Lettrist-esque “ambiance units”: the light-choking alleyways of the Boston Conflict Zone; the Commons, with the light off Swan’s Pond and the shadow of Trinity Tower; the gouged and barren countryside, which I remember as a succession of broken roads and stark branches against a hazy sky. Though these landscapes are all variations on a theme of apocalyptic menace, the emotional diversity of that menace is crucial to the success of the game.

My cousin once did a playthrough of Red Dead Redemption with both the navigational mini-map and the fast-travel option turned off; he said it forced him to keep his eyes open to signs and landmarks, to remember pathways from one town to the next, and sometimes to drift about in search of activity. Open-world games, at their best, thrive on this openness to accident, this marshalling of a player’s powers of observation and memory.

But open-world games also suffer from a creeping instrumentalism, a tendency to view aspects of the game as means to an end. Wherein each beautifully rendered landscape is just another game level to pass. Wherein each carefully art-designed object is just another stat-enhancer. Wherein Fallout 4’s Nick Valentine, an android fiercely struggling with his own almost-humanness, is just another glowing arrow showing you where to stand to trigger a mission.

The struggle here is between two meanings of the word “game”, a specific one and a general one. In the specific meaning of “game” there is a codified set of rules and objectives that designates a field of play. But in the general meaning of “game” there is a radical celebration of frivolity and human freedom, of the wide-open vistas of life. This second meaning is the one that Sante embraces when he implies that the Lettrist dérive through Paris was a sort of game. These two visions of “game” are very close to Sante’s two visions of Paris: one a capital of planning and administration, the other a riot of independence and abandon. While I would never be so bold as to say that open-world games should abandon stats and objectives and structures, I believe that they reach their full potential when an ethic of freedom and chance is taken as a lodestone.

Open-world games are founded on a principle of wandering and soaking up the variety of their landscapes

Michael Silverblatt, host of the literary public radio show Bookworm, quotes author William Gass, saying that Gass “thought the that the job of a writer was to wean his audience from stories and to return them to the love of the world, the things of the world, its details, its nature, human nature.” As with literature, as with any art, I think games can achieve this self-transcendence too. I’m always fascinated by the way I feel upon going back out into the world after a prolonged session with a game. Sometimes this feeling is very dark, like after playing too much Grand Theft Auto, when every passer-by looks like a mark or a victim. But sometimes the feeling is sublime, like how playing The Witcher 3 makes me more alive to the wavering of trees in a storm and the varieties of sunsets. Sometimes I wonder why I play games at all, when the world itself is so full of menace and risk, beauty and grace.

Maybe this is all just an elaborate way of saying that I should put down the controller and go to Paris, and see what I can see.

Feature Photo Courtesy of: Peder Skou

January 25, 2016

Dreii to bring people together in (almost) wordless collaboration

Take your fingers out your (p)lugholes and listen up: Etter Studio has let the world know that its “collaborative physics conundrum” Dreii will be drifting onto Steam (for PC), iOS, and Android on February 2nd. This is fab news.

To explain, Dreii is the new version of Etter’s European Design Award-winning co-op puzzler Drei (2014). The immediate difference between these two versions of the same game is that Drei is only available for iOS (on the App Store) while Dreii is also heading to Android, PC, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Wii U. It will allow for people to play together regardless of whether they’re on PC, console, or mobile. And yes, there are dates for those other platforms too: PlayStation gets it on February 9th, Wii U on March 8th. But that’s not all. Dreii also has faster physics than its predecessor, brand new levels, and a new addition to its cast of quietly floating characters.

these three people are always brought together as strangers

If you recognize the Etter Studio name, but not from Drei, then perhaps it’s due to last year’s orifice-stuffing interactive short Plug & Play. Drei is the game that Etter made before Plug & Play but you can see across both a shared visual etiquette. Each use animated characters in a monotone environment, drawing attention to the small action at the center of the screen; between actor and prop. In fact, both games do have a stage-like quality to them. But where Plug & Play seems more aligned with European arthouse cinema of the 20th century, Drei (and, indeed, Dreii) are informed by wordless multiplayer experiences such as the seminal thatgamecompany’s Journey (2012).

Drei, presumably, refers to the German word for three. Three being the number of online players that can be brought together in a single game. The idea is for them to work together to stack up objects to reach a certain height. These objects are typically awkward: lots of strange angles, curved surfaces, owing to unstoppable calamity without a moment’s warning. It’s due to the near-impossible stability of these towers that you need three people to succeed through the levels, hoisting objects with their collective tethers. But what makes Drei special is that these three people are always brought together as strangers and are barely able to communicate with each other, so that they also leave the experience as strangers too.

In place of Journey‘s singing, Dreii has a wheel of words that you can select from to nudge your collaborators. Well, one-note expressions, really: “Sorry,” “Slowly,” “Yay,” among others that will be available across 19 different languages. These words are handy to use on occasion but allow enough room so that Dreii becomes a game of doing rather than saying. Gesturing through the movements of your flying character becomes the dominant way to interact with the objects and the other two people. You demonstrate, encourage, suggest.

This creates a culture of helping each other out through action. You see another player struggling with a task and feel obliged to help out. Or, if you see their thinking is wrong, you want to move in and show them how else it could be done. Disagreeing or arguing takes too much work or is not even possible to bring to the fore in such an abstracted language. It’s what made Journey work so well, why people felt so connected by the end of it all, and why Dreii should play host to a positive-feeling space of both determination and cooperation.

The Witness is videogames’ long take

There are all sorts of studies floating around about the human attention span, and usually about how it’s getting shorter. I’ve heard my fair share of anecdotes over the years from teachers, supervisors, and fellow artists about how long an average audience member is willing to engage with a piece of media. Five seconds for a painting. Six seconds for a single shot in a film. 30 seconds for a free iPhone game. The list goes on, but suffice to say, these soft rules are geared toward grabbing audience attention quickly in hope that they’ll stick around for much longer. Even with this article here, you’re probably anticipating that I’ll cut to the chase in the next paragraph and tell you what I’m writing about. It’s true, I will (please like me).

I’m over 300 puzzles into The Witness and I don’t know what it’s about. It seems like the game is definitely going to be about something, and it might even try to be about everything, but it’s not a game that plays its hand anywhere near the opening twenty or so hours. I’ve been wandering around this deserted island, buzzing from puzzle screen to puzzle screen, soaking in the landscapes and the scattered little secrets that point to that something, but somehow never really hint at what it is. The more I uncover about the way the island works, the more puzzles I can solve, but with little indication as to what I, as this unnamed humanoid (you cast a shadow that seems to have my shaggy Jim Halpert haircut from 2006) entity, am doing on this island.

more like a Bela Tarr or Andrei Tarkovsky long take

And if what creative lead Jonathan Blow says is true about the enduring faith that The Witness asks of its players (80+ hours of time/very small percentage of players will complete every puzzle) then it’s sort of the ultimate videogame-as-long take—a long take being when a film doesn’t cut away to a new shot for minutes on end. And I’m not talking about the Alfonso Cuaron kind of long take where there’s all sorts of high stakes suspense—like spinning space stations and last child to be born on Earth kind of tension. No, The Witness is more like a Bela Tarr or Andrei Tarkovsky long take. The kind where you watch a guy walk down the street for five minutes to illustrate what a bummer his life must feel like. I kid, but the point is that sometimes there’s a reveal at the end of a Tarr/Tarkovsky long take, and sometimes there isn’t. And eventually, as someone who loves this kind of cinema, you stop trying to anticipate the reveal.

I don’t know what’s going to happen in The Witness when I complete what seem to be all of the major puzzle areas, and I don’t know if there’s a twist coming that will make me rethink my actions up until that moment. For now, I’m just taking pleasure in the act of playing the game, and will continue to do so for as long as my attention holds.

Now you can play Winston Churchill’s card game too

If Churchill Solitaire existed in smell-o-vision, it would reek of cigar smoke. Seeing as the game only exists on iOS, however, identifying the precise stench it gives off is something of a challenge.

The game, which was developed by WSC Software and former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, is based on a card game Winston Churchill supposedly played during World War II. This connection is played up at every turn. The game opens with archival footage of the war with one of the British Prime Minister’s famous speeches playing in the background. The levels a player can progress through in campaign mode are based on British military ranks. There is, however, no written proof that Winston Churchill ever played this modified—and more complicated—version of solitaire. The Wall Street Journal’s Julian E. Barnes explains that Belgium’s ambassador to NATO, André de Staercke, taught the game to Rumsfeld, who held the equivalent American position in the mid-70s. De Staercke spent World War II in exile in London, where he was close to Churchill and presumably learned the game in question. Thus, Churchill Heritage Ltd. told Barnes that the provenance of the game is “entirely credible.” Let’s be generous and call the story Rumsfeld is now peddling a ‘known known’.

never give in

Churchill Solitaire can be thought of as an exercise in high-level strategic thinking. That’s certainly what its developers would like you to think. With two decks and bonus challenges (including avoiding a card known as the ‘Devil’s Six’), Churchill Solitaire is definitely more complicated than your average game of solitaire. Whether that counts for much is a matter of interpretation. Still, it’s clear what side Rumsfeld comes down on. He told Barnes: “It is a game that requires you to be strategic, to look around corners, to think ahead, and to never give in—which is the phrase Churchill would have used.”

There is, of course, another way of thinking about Churchill Solitaire, which hews less closely to the company line. The sort of strategic thinking Rumsfeld and co. are touting is hardly unique to their game. Most games require players to engage in strategic thinking and there is scant evidence that Churchill Solitaire forces the player to operate on some higher intellectual plane. Would no other game fulfill a similar role? But Churchill Solitaire isn’t as concerned with gameplay as the historic narrative it seeks to advance. The game exists to draw a neat line from Churchill to De Staercke to Rumsfeld to you, the player. It co-opts the player into the sort of hero worship you’d expect from a practitioner of “great man” history. The game is largely a vehicle for delivering archival clips, but Churchill doesn’t need the game’s help and Rumsfeld doesn’t deserve to be labelled a great strategic thinker by association.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers