Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 177

January 8, 2016

Apocalypse Now (& Again)

In English, the word “apocalypse”—ety. Greek, n. apo (un-) + kaluptein (-veil)—has three non-exclusive uses. The first and most common is simply the end of the world, whether by divine punishment or whatever transpires in movies directed by Roland Emmerich. The second is any form of calamity, representational or real, man-made or no, that resembles the end of the world, like the 2010 Haitian Earthquake, Chernobyl, or the movies directed by Roland Emmerich themselves. The third is what the Greeks intended apocalypse to mean: the revelation of knowledge through profound disruption, which is why the final book of the New Testament is called “Revelations” (composed, it is thought, to reassure Christians during their widespread persecution by the Roman emperor, Domitian). In other words, the apocalypse either is the end, looks like the end, or helps us understand the end.

Like books, movies, and the visual arts, videogames are well-acquainted with the apocalypse. Countless games have been set in the final days of mankind; countless more ask the player to prevent them. Yet, as mere setting, the apocalypse can never be truly apocalyptic—when Mass Effect 3 ends and the galaxy has been saved/altered/destroyed, you can always boot up the series’ first act and play it all again. The finale is not the end. In the curious lexicon of games criticism, we often speak of “world-building,” yet rarely do we stop to think about its opposite. Anything made can be destroyed, yet destruction in games is rarely the destruction of games. What masterpiece of eschatological design could possibly convey the all-encompassing, crushing finality of a true apocalypse?

Perhaps we will never know. But, in the meantime, we have the next best thing.

Since the 1990s, when the spread of reliable in-home internet made persistent game worlds both commercially and technically viable, the game industry has developed over 300 massively multiplayer online games, some gargantuan (The Old Republic, etc.) and others more slight, like the thoughtful browser-based government simulator, NationStates. The majority of MMOs, of course, do not experience the runaway success of World of Warcraft or EVE Online and eventually adopt a free-to-play model once it becomes clear that subscriptions alone cannot sustain ongoing costs. But a smaller number—44, if Wikipedia is to be believed—have been shut down, and with their closure, their persistent worlds simply phase out of existence, beyond the reach of any archaeology. And this is surely an apocalypse of every kind.

Star Wars: Galaxies launched in 2003 to critical and commercial acclaim. Though videogames routinely spoil the player with fantasies of singular greatness (in Elder Scrolls Online, every player is, improbably, “the one”), Galaxies initially set its sights lower. Instead of saving the Star Wars universe for the umpteenth time, the player was asked merely to live in that universe, getting by doing anything from bounty hunting to stripping in dusty cantinas on the Outer Rim. That might seem hopelessly jejune in 2015, but Galaxies was a tremendous success for several years. Alas, in 2005, in response to a lack of new players, Sony Online Entertainment redesigned the game to emphasize combat, trading the game’s supreme sense of inhabitation and belonging for a sense of power (the lure of the dark side indeed!). Players revolted over the bowdlerization of the game’s combat, and, by 2006, barely 10,000 people could be found in Galaxies on any given Friday. The death-knell came in 2011, when SOE announced, to no one’s surprise, that Galaxies would be shut down for good in December of that year (not coincidentally, the same month that BioWare launched its dreary Star Wars MMO, The Old Republic).

In the end, though, the final moment was a whimper

Call it pity, or perhaps apology, but SOE took the end of Galaxies to do something meaningful with its apocalypse: it declared a winner for each server based on the relative population of Rebels and Imperials. And in the galaxy’s final moments, before the servers took everything and everyone with them, the players who remained gathered in Mos Eisley and Corellia to wait for the end. Bittersweet celebration ruled the day: veterans let neophytes try out their finest gear, the sky was filled with brilliant (if lag-producing) fireworks, and the spaceports clogged with groups of friends, some cultivated over thousands of hours, waiting to say goodbye. In the end, though, the final moment was a whimper. Writing in PC Gamer the next day, Chris Thursten captured the moment perfectly

[We] timed the hyperspace jump to coincide with the final shutdown. As the seconds tick down, the hyperdrive calculation rises to 100% completion . . . The time hits zero and tiny points of light begin to streak across the windows then freeze, arrested in time. The moment hangs, the game unresponsive, one of the most iconic images in Star Wars halted before it can fully play itself out. “You cannot connect to that Galaxy at this time. Please try again later.”

Not every apocalypse is so poetic. Sega’s ill-fated MMO The Matrix Online ran from 2005 to July 2009, when it was brought down with little warning by none other than SOE, which had purchased the property from Sega some years before. Like they would later do for Galaxies, SOE organized a final event for The Matrix Online. But unlike Galaxies, it was not so much a celebration as a genocide fitting of an apocalypse. On PvE servers, SOE flooded common areas with high-level monsters that slaughtered every player in sight; on PvP servers, players discovered that their weapons had been augmented to kill other players with a single shot. A bloodbath ensued; anyone whose character died found that death, suddenly, was permanent. In both cases, survivors were cut down by an unexplained electrical phenomenon (a glitch in the matrix, so to speak). In one YouTube video, perhaps two dozen players obliviously wait for the end. Someone in the server-wide chat yells “I’m smoking weed and crying”; someone replies, “Please don’t cry.” Seconds later, a bolt of ochre lightning tears through the crowd, killing everyone. The contortions are horrific; the screams are worse. After, the only sound is an irregular beep, like an old modem. Someone asks “Is it over?” A pop window answers: “Failed to reconnect to the margin server. Shutting down.” The machines win after all.

Star Wars: Galaxies and The Matrix Online stand out among MMO apocalypses as a conscious attempt to script a proper “end” to their universes, whether celebratory or catastrophic. Most titles, though, take a simpler route: passing out free high-level gear or experience boosts to offer players a sense of closure, however insufficient. In its final months, Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean Online offered players double gold, double XP, and unlocked all the game’s content for all its players. But in the end, the small population of remaining players watched the world go dark from the beaches of Port Royale. Another Disney Property, Toontown Online, ran for over a decade before being shuttered in 2013. With two weeks to go, Toontown Online arranged for its holiday events to take place two months early and flooded Toontown with the game’s most iconic foe, The Big Cheeses (“Watch out! I can be a real Muenster at times”), a parody of corporate greed, which, in retrospect, is an oddly apropos metaphor for a beloved children’s game whittled into extinction by the budget hawks at Disney Interactive.

Players can celebrate or they can resist, but in the end, they cannot stop the inevitable

Even when a developer doesn’t plan a final hurrah, players often take it upon themselves to commemorate their world’s imminent end (Cormac McCarthy, in The Road: “When one has nothing left, make ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them”). In Hellgate: London, which lasted barely 18 months thanks to gross mismanagement by its developer, Flagship Studios, the small band of players that held out to the end took it upon themselves to don their most visually outrageous gear and fight the game’s final boss, which had long since ceased to be a challenge. How ironic that a game set in the apocalypse succumbed to another apocalypse. The final moment, when it came, arrived without warning: a friend of mine who played Hellgate from beta to the end told me that he was cut off mid-conversation by a final, mass disconnection. But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven…

Faced with annihilation, other communities resist: when Bungie announced in 2010 that it would soon take Halo 2’s long-running servers offline, several dozen Halo 2 fanatics vowed to leave their consoles on in order to host further matches. One by one, whether by overheating consoles or the loss of power, the number of dwindled to a handful of hosts. The last holdout was disconnected by Bungie nearly six weeks after the “official” end of Halo 2. In some, players vow to resurrect their game on a private server; few such plans work out on the players’ terms. Those MMOs that are revived by carrion-picking studios are often flattened unrecognizably to prepare them for the designs of free-to-play, as was the ultimate fate of Hellgate: London. Players can celebrate or they can resist, but in the end, they cannot stop the inevitable.

No matter if it’s that final horror of The Matrix Online or the somber last acts in ToonTown Online, it’s not hard to see how the end of an MMO constitutes an apocalypse of the first and second kind (i.e. “the end” and that which resembles the end). From the perspective of the characters who inhabit a doomed MMO’s diegesis, it is truly the end of everything, their world, as the poet Philip Larkin put it, “[soon] to be lost in always, not to be here, not to be anywhere.” For players, the apocalypse is, of course, not real, but nevertheless imparts a real experience of what the apocalypse might be like, to see a world they have come to care about lose its ability to be. But what about the third form of the apocalypse, that which helps us understand the end? How do MMOs help us come to terms with the causes and effects of an apocalypse on any scale?

The media scholar Richard Grusin attributes the popularity of end-of-the-world scenarios in popular media to a phenomenon he calls “premediation,” the representation of cataclysm to build the public’s expectations for a real cataclysm. The plausibility of these scenarios matters little; the point of premediation, Grusin holds, isn’t “prediction” but “practice” — we steel ourselves for any number of possible futures so that we might overcome whatever trauma awaits us, like swallowing a pill to prevent the heartburn we know is coming. Because we know, all of us know, deep down, that apocalypse awaits us on every scale. Premediation helps us rehearse our reaction so that, in the event of real chaos, we might behave in a manner more rational and productive.

Apocalypse awaits us on every scale

It’s easy to see how games like Fallout 4 (2015), Mass Effect 3 (2012), and Mad Max (2015) constitute a kind of premediation, rehearsing our collective anxieties over nuclear war, AI takeover, and ecological devastation, respectively. Yet premediation isn’t quite sufficient to describe the end of an MMO—SOE likely didn’t imagine, or at least did not intend for, Galaxies to suffer its gradual blackout. Premediation, like its prefix implies, is rooted in what comes before; by the time an MMO shuts down, it’s already too late. In this respect, all-but-forgotten Hellgate: London is an object lesson in this distinction, a game about an apocalypse that eventually fell victim to its own. But if not because of premediation, why should we care about the end of MMOs at all? What knowledge is there that isn’t present elsewhere?

If there can be said to be any good in an apocalypse, it’s that it almost always reveals something about what went wrong. As the New York Times columnist David Brooks (of all people) wrote in an Op-Ed just days after Hurricane Katrina transformed economic marginalization into mass death, apocalyptic disasters “wash away the surface of society . . . expose the underlying power structures, the injustices, the patterns of corruption and the unacknowledged inequalities.” In the days after Port au Prince’s horrific 2011 earthquake, it became clear that the landslides that killed so many were tied to decades of strip-logging in the forests nearby. (This phenomenon was itself tied to the nation’s sovereign debt, which replaced colonial occupation as a means of imperialist domination, in a chain of injustices stretching back to the European encounter, depicted at the end in Mel Gibson’s historical epic named, not coincidentally, Apocalypto.) There are no such thing as natural disasters, just fantasies we entertain to excuse our inaction.

In other words, an apocalypse can help bridge the gap between what we experience and why we experience it, to negotiate between our lives as individuals and the systems that establish the limits of our experience. The point is not to equate the closure of virtual worlds and tragedies in our own, of course, but to note that videogames can be excellent at modeling characters and sublime at representing systems, but rarely does a single game succeed at both. In an article in The Atlantic, Ian Bogost argues that what games offer, above all else, is an “operable argument . . . that shows us something about the world outside ourselves, something incomplete and grotesque, but something we ought to see.” Through simulation, we transcend the need for personal identification and focus instead on systems we are embedded in. On this count, Bogost surely has a point. But it’s only half the story. Life might occur within systems, but it is not itself a system. Identity or system, narrative or simulation, representation is always a failed project—if a game could represent everything, it wouldn’t be a game at all, but (and just) a perfect simulacrum of the real. What’s unique and valuable about the end of an MMO is that it can be read as a kind of representation, but it’s also a kind of “real” event that destroys representation, the destruction of an imagined world. With that duality comes the ability to wander between personal identification and reflection on the institutions that give rise to identification.

Representation is always a failed project

Looking back at Galaxies, Hellgate, ToonTown, and everything else that occupies the immaterial junkyard of discarded universes, the signs of their impending doom are all too obvious. In Galaxies, the attempt to simplify combat galled old players; the subsequent reversal of these changes alienated new players. In Hellgate: London, the lack of new content for players to experience in-game signaled that something was deeply wrong outside of the game; Flagship Studios filed for bankruptcy in July 2008 and all of its intellectual property was seized as assets, halting the creation of new material. And closure doesn’t have to be about failing revenues; it can be about building new ones. Contrary to conventional wisdom, ToonTown didn’t shut down on account of dwindling subscriptions. Rather, as Disney Interactive wrote in the press release announcing its end, “we are shifting our development focus towards other online and mobile play experiences, such as a growing selection of Disney Mobile apps.” The simplicity of ToonTown’s mechanics lent itself to the uncomplicated interfaces of mobile devices, the preferred platform for the game’s target demographic, children age seven to twelve. In every case, built into the experience of play is something larger about the architects of the machines in which we play. And when those machines shut down, even (and especially) when their indifference doesn’t match our own investment, we should know that the heraldry of the end times were there all along. There’s always truth in a ruin.

An apocalypse cares for nothing but its own being, bought at the expense of everyone else’s. Only a hopeless optimist would think that games can save us from whatever fates await us, as individuals or more. But whether at most or at least, the end of a world, even a virtual one, can help us understand both our own experiences and how “made” those experiences are, no matter how natural and private they feel to us. Before it can be changed, it must be understood. And it matters that we do, more than anything—eventually, there will be nothing to save but ourselves.

January 7, 2016

Quiet as a Stone will evoke humanity’s architectural awakening

We remarked back in July last year that Richard Whitelock’s upcoming “simple stone throwing game” Quiet as a Stone turned nature into your own personal playground. But it seems a better metaphor would be comparing it to the Mesopotamian mud flats where it is thought humankind’s first buildings were erected. This is a game that ostensibly simulates that important architectural moment in our ancient history.

This insight is born of Whitelock’s latest update on his progress with Quiet as a Stone, which includes how he first came up with the idea, and how it has changed over the months. To start, Quiet as a Stone was intended only as a means to test some of the ideas he has for his larger project, Into This Wilde Abyss, as a smaller and more manageable off-shoot. (It is still that but, my, how it has grown!) His initial idea, or vision, was a child throwing stones at the ground, what Whitelock calls a “canvas for world making.”

insignificant stones turn into walls and pillars

This idea wasn’t random. Whitelock decided to mimic Shigeru Miyamoto’s process for coming up with the original The Legend of Zelda. Miyamoto cast himself back to his childhood, when he explored the forests, lakes, and caves of Kyoto, Japan to come up with the formative NES adventure. Whitelock made a similar journey into the past. But the thought didn’t grow legs and coalesce until a particular moment in the present overcame him.

“I distinctly remember a photo walk around Oxford thinking this idea over when I noticed the setting sun glancing over the mud and worn stones of the grounds I was in,” Whitelock writes. “The simple interaction of a stone bouncing from soft mud to hard stone came to mind. I knew I could represent it as I saw it. And I saw a blank canvas for a whole potential world of interactions and atmospheres.”

With this locked down, Whitelock then had to piece it all together, using photogrammetry to create detailed representations of his miniature vertical portraits of rock and dirt. He knew that to encourage players to imagine the potential in these primordial building elements—to have that playful “a-ha” moment when insignificant stones turn into walls and pillars—he needed to achieve a sense of solidity, for it to “feel reactive and graspable.” This progressed with lighting and weather effects being added, but most of the work that Whitelock did was in the audio: ambient breezes, the caw of distant crows, rocks hitting stones, clay pots smashing.

That much would be enough to justify it being described a playground. You throw stones and enjoy them tumbling across the jumbled topography, chiming with a pleasing tactility. This much made Quiet as a Stone a pleasure machine in that it delivered an experience of nature through artificial means. Pachinko for ecologists. But what comes then? Whitelock took it further, not only relying on an imagined architectural space, but an actual one—he added the icons of ruins and eventually entire small villages with adorable country cottages, windows illuminated with signs of life.

“What if Diablo 3 was an art application?”

The idea was becoming fuller, bigger, and it was a time of perplexing clouds of thought. “I was looking for strange, useful questions to ask myself,” Whitelock writes. “What if Diablo 3 was an art application? What would an atmospheric pinball game be like?”

All this, it turns out, is where the game was left months ago, before Whitelock took it to the Eurogamer Expo in September 2015. Having since had people playtest Quiet as a Stone, he has decided to completely rethink how to engineer player creativity, deeming it necessary after some (not all!) left the game bemused and frustrated. He’s now also working on other projects outside of his personal ones so it may be a while yet until Quiet as a Stone emerges from its cubbyhole. For now, await.

What is virtual reality?

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

You cross the ice and reach a crevice. You look down and see how deep it runs, how dangerous a fall it would be. With a running start, you hop over it and continue along the icy path. When you enter a valley, a roar echoes from the right. A behemoth 50 feet tall stomps toward you. You follow it with your eyes as it reaches you, then steps over you. It walks out of sight. You once again are alone in this windy valley in icy Antarctica.

This is a scene in Edge of Nowhere, an upcoming computer game that will use the Oculus Rift headset to bring you to a monster-ridden version of Southpole. In a couple of months such immersive games will be available to everyone thanks to the release of virtual reality headsets.

“Virtual Reality is a set of technologies that are aimed at fooling your senses into believing that you’re in a different environment than the real world,” said Kim Pallister, director of content strategy for Intel’s Visual Computing Group.

Now you can duck to see what is on the floor, lean out a car window to watch the scenery

One of the first VR (virtual reality) games coming out is The Gallery from Cloudhead Games, where you walk around strange worlds and solve puzzles. Denny Unger, Creative Director of Cloudhead, said, “I usually start off by telling people that this generation of VR hardware is more like the first generation holodeck. The problem then becomes proving to them just how apt that description is and the only way to do that is to get them in a headset, in a walking volume, and with hand controls.”

Rather than looking at a flat screen ahead of you, in virtual reality you have a small image for each eye and your brain combines the two into three-dimensions. Since the lenses magnify the image, you aren’t looking at a rectangle out in front of you like a TV screen. Instead, it fills your field of view. The screen stays strapped onto your head, so the picture moves with you as you turn. It’s as if you’re actually rotating your head in the virtual world, allowing you to look up into a virtual sky or look back on a virtual motorcycle.

Pallister said, “The first and foremost thing is presenting a stereo 3D view. Right along side that is letting you change that view along with changing the position and orientation of your eyes and your head. So when you tilt your head downwards to look at the floor, the view of the world you are seeing looks down toward the floor in a way you expect. You forget you are wearing an HMD (head-mounted display).”

The first VR headsets will have screens with resolution similar to HD televisions. But since the image is so close to your eyes, even greater detail will be necessary. Right now, the horsepower of computers limits how detailed you can get, since VR has higher technical requirements than normal computing. But within the next few years the screens will jump to 4K or even 8K, letting people see even richer worlds when they look around.

Some headsets take immersion further by using external sensors like a camera to track how your body moves. Now you can duck to see what is on the floor, lean out a car window to watch the scenery. The screens aren’t a static image. They are a view into an artificial reality. The sensor also tracks an area of a room, so you can even walk around a room and the image reacts like you are walking in the virtual world.

The screens aren’t a static image. They are a view into an artificial reality.

The software to make VR images believable is tricky, requiring a distortion of the images so the lenses can put them in the eye properly. It has to present the image smoothly, so the moving graphics aren’t jerky or make you dizzy. While television airs at 30 frames per second (FPS) and some games go as high as 60 FPS, VR uses 90 or even 120 frames per second. Such smoothness makes the world feel more solid.

Unger says, “When the display’s refresh rate and a game’s native frame rate marry to hit over 90 frames per second something magical happens. Some call it ‘presence,’ the sense that what you’re seeing has tangibility even if it’s clearly not real. This is difficult to describe but is immediately apparent.”

Some products will also track your hands with a sensor, putting virtual objects in your grasp and control. In The Gallery, players solve puzzles a la the classic game Myst. You travel around a world, figuring problems out. But now, you are actually walking around a scene, leaning around the puzzles, and using Vive’s motion controls to handle the objects involved. It’s profoundly different from statically clicking a cursor on a computer screen, turning fictions into worlds that surround you.

“Normal use of a computer monitor provides you with visual information. Whether you are playing a game or watching a movie. They say, ‘We will do our best to tell a story, but you have to suspend your disbelief.'” said Pallister. “With VR, they say, ‘What are the things that cause people to realize they are not really in that environment? Let us try to fool those senses, one by one, until they can no longer tell.'”

Like the evolution of cellphones, features like tracking will become more detailed, eventually tracking eye movement, facial expressions, even lip movement. Virtual worlds will be presented to you more realistically and you will be more accurately represented in them. Such fidelity will bring more compelling experiences, and like cellphones, adoption will then become more widespread.

Unger said, “‘Good VR’ is undeniably compelling and consumers from a broad cross section will have a high appetite for it. The applications are so far reaching that it’s clear this medium will dominate in entertainment, education, training, travel, research, and socialization. It’s one of those technologies that will have a profound impact on our lives.”

North Korea isn’t playing

North Korea dropped a bomb. “It was confirmed that the H-bomb test, conducted in a safe and perfect manner, had no adverse impact on the ecological environment,” Pyongyang announced, by way of the Korean Central News Agency. “The initial analysis is not consistent with the claim the regime has made of a successful hydrogen bomb test.” Even if it’s not the “H-bomb of justice” the KCNA makes it out to be, we must now talk about the bomb—including the Security Council, which will discuss further sanctions—and that’s the point. When your foreign policy is also a content strategy, it barely matters that “DPRK News Service” on Twitter is a fake account. A retweet’s a retweet. Welcome to kleptocracy-by-clickbait.

Elsewhere in North Korean content strategy, the Associated Press has tested the country’s hottest mobile game, Boy General. Eric Talmadge describes the game, which was first released in September, as follows:

“In the game, players are prompted to go on missions to defeat the enemies of the young general Swoeme, which means ‘Iron Hammer,’ a brave warrior-commander of the Koguryo kingdom that lasted for about 700 years and ruled most of the Korean Peninsula and the heart of Manchuria until its downfall in AD 668.”

The game’s political parallels with another supposedly “brave warrior-commander” aren’t exactly subtle, but subtlety is neither North Korea’s forte nor its likely end goal. As a piece of content strategy, Boy General is a brand extension for the nation’s venerable animated series of the same name. The show’s original 50-episode run that ended in 1997 and was revived by Kim Jong Un last year. Vice reports that the titular prince in this revival is no longer a boy. Like Kim Jong Un, he’s now a man. Go figure. Anyhow, the hero is fighting to preserve the nation and its purity, and with higher production values to boot.

even the Supreme and/or Dear Leader must have a strategy for second screen experiences.

The revitalization of Boy General’s IP comes at a curious moment for North Korea. On the one hand, the nation is still generally isolated and desperately poor. The country is not, however, completely off the grid. Particularly in Pyongyang, there are enough screens and pockets to allow for media consumption. “State-run TV is dominated by bland fare of old propaganda movies and news programs praising the country’s leadership,” writes Talmadge, who notes that media from South Korea and China regularly crosses the border. Boy General’s higher production values are best understood in this context as a way to combat viewers’ ennui. Content strategy is about securing mindshare, after all, and even the Supreme and/or Dear Leader must have a strategy for second screen experiences.

Boy General is not, however, North Korea’s first videogame. Nosotek, a North Korean developer founded in partnership with foreign investors, released the browser car-racing game Pyongyang Racer in 2012. In the game, which no longer appears to be online, the player drove a car around a track that vaguely resembled the country’s capital. Insofar as Pyongyang already looks like the city time left behind, the game’s primitive (for 2012) graphics did it no favors. Its world is deserted; buildings are few and far between. Judging by the gameplay videos that remain online, Pyongyang Racer flattens the perverse architectural charms of a city The Guardian’s architecture columnist Oliver Wainwright likened to a Wes Anderson film set.

The great irony of this game, which made Pyongyang look even less appealing than it actually is, was that it was designed to attract tourists. Koryo Tours, a company that arranges for foreigners to travel to North Korea and currently boasts on its website that it is recommended in “Lonely Planet,” published the game. Although foreigners do travel to North Korea, there is no concrete evidence of a tourist being persuaded by Pyongyang Racer. That is understandable: the game was unbelievably grim.

What was our most popular book of 2015? Find it in our library catalogue! https://t.co/hmfeCmGKCj (UN only) pic.twitter.com/niGXUxHtGt

— UN Library (@UNLibrary) December 31, 2015

In addition to being more uplifting than Pyonyang Racer, Boy General appears to be less concerned with international audiences. This domestic focus is in part attributable to technological factors. Unlike Nosotek’s racer, which was easily diffused online, Talmadge notes that Boy General is shared using Bluetooth. But Boy General’s particular focuses as a game ultimately come down to the idea of politics as content strategy. Games and TV deal with the situation in Pyonyang; bomb tests, on the other hand, simultaneously provide content for the domestic and international markets.

A love letter to the stony architecture of Ico

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

In Ruins (PC, Mac)

TOM BETTS

The craggy, mysterious ruins of Ico’s fortress-like castle are known for their wind-blown eeriness. Tom Betts has taken that game’s architecture and used its melancholy character as a model for one of his experiments into procedural generation. The idea, he says, is to interpret the work of Romantic landscape painters, such as Thomas Cole and Caspar David Friedrich, as a sublime videogame. The result is an island of broken ramparts, cold beaches, and overgrown pathways that lead to crumbling staircases, or sharp faces of moss-covered rock. At the center is a tower with a golden aura that draws you to it. You can head straight to this tower’s peak if you like. But that would be to miss the pithy extracts of Roman philosopher Lucretius’ poem “On The Nature of Things,” which echoes a historic importance through the virtual monuments. After, you’re allowed to fiddle with the tools that generate the island in order to author one closer to your preferences.

Perfect for: Ico fans, landscape painters, ruins zealots

Playtime: 20 minutes

How virtual reality will push PCs to their limit

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Today, almost everyone can access entertainment on their PCs, consoles, tablets and smartphones. Anyone eager to own a new virtual reality headset, however, must first find out if their trusty computer is up to the task. Oculus released its computer hardware requirements for the Rift headset last May, which means many people need a new computer if they want to enjoy VR experiences like this thrilling roller coaster ride.

As a VR device, the Rift (headset) will be capable of delivering comfortable presence for nearly everyone, wrote Atman Binstock, Oculus chief architect, in a blog post announcing the new Rift requirements. However, this requires the entire system working well. The entire system Binstock is referring to is a computer that can feed high quality video to super high definition headsets.

Anyone who wants a PC ready for virtual reality will need to have a computer equipped with an NVIDIA GTX 970 / AMD 290 equivalent or greater graphics card; a 4th generation Intel i5 (4590) processor equivalent or one with greater performance; at least 8GB of RAM; compatible HDMI 1.3 video output; 2x USB 3.0 ports; and Windows 7 SP1 or newer operating system.

These computer requirements mean that anyone with a computer that is more than two years old may not have the oomph to power new VR goggles and gear. Computers will have to deliver video to the headsets two 1200 x 1080 displays, each with a 90 frames per second (FPS).

Thats right, higher than HD quality at 90 FPS.

That rate brings abundantly more visual images to the human eye than 30 FPS for standard TV broadcasts and high quality 60 FPS videogames. To smoothly deliver that many pixels to two headset screens so quickly requires a PC with ample horsepower. ”Most consumers find virtual reality a mind-blowing experience the first time they try it,” said Ben Wood, CCS Insights Chief of Research, in a recent report about virtual and augmented reality technology sales.

Thats right, higher than HD quality at 90 FPS.

His team of technology analysts believe VR has the potential to be one of the most disruptive technologies for a decade. A CCS Insight report concluded that the transformative experiences they bring could spur more than 12 million VR headsets be sold in 2017. As people spend more time with VR, its likely theyll buy more than one new VR-ready device. CCS Insight expects 2.5 million virtual and augmented reality devices to be sold in 2017, with that number climbing to 24 million devices in 2018.

With more devices expected to hit the market in the years ahead, industry leaders are teaming up to make it easier to identify what hardware and accessories work best together. Oculus is partnering with Dell and Asus to sell PCs with an Oculus Ready label in 2016. The label helps buyers identify which new computers work well with VR. Microsoft is also working with VR gear companies to make Direct X12 and Windows 10 deliver VR entertainment efficiently from PCs.

While consumers may not want to dish out cash for a new PC, Epic Games software engineer Nick Whiting believes new hardware will allow people to enjoy VR games and entertainment built to Oculus standards and beyond.

“Pushing the boundaries is always where the most exciting stuff happens,” said Whiting, who with Nick Donaldson are the Epic Games software engineers behind the VR demos that showcase Unreal 4, one of several established engines that developers are using to provide a software platform to create new immersive experience. Their Showdown demo pushed the limits of high-end graphics, but they designed their Bullet Train demo to run on Oculus standard computer hardware spec. ”The rendering optimizations we did for Bullet Train were a lot more efficient,” said Whiting.

Many developers are putting in extra eye-candy

“Using the recommended software is ideal because thats the standard most games will be judged by,” said Oculus founder Palmer Luckey. “Many developers are putting in extra eye-candy for people with high-end hardware, which is really just a continuation of how the PC industry has always operated,” Luckey continued. There will always be levels of quality that only those on the leading edge will have access to.

While the VR-obsessed few are likely to invest in high-end equipment, Luckey sees the new requirements impacting a different market of PC gamers. Non-gamers and casual gamers face the toughest challenge. “They have never had to worry about owning a powerful PC,” said Luckey. “It will take time for VR to trickle down to typical PC hardware.”

January 6, 2016

Self-driving cars won’t kill mass transit: they’ll save it

Google is an optimistic company. Presenting itself as Silicon Valley’s version of Disney’s imagineers, the tech giant consistently predicts a future where its innovations drastically change the way we approach everyday activities. To be fair, advancements like its widely-used Android operating system have shown that its predictions aren’t entirely unreasonable. But for every Android or Google Docs, there’s a Google Glass, which in retrospect reads like the mad dream of some 1950s futurist. As much as Google would like us to see it as a high-tech Nostradamus, experts suggest the truth of their predictions may lie somewhere in the middle.

the truth of their predictions may lie somewhere in the middle

Take self-driving cars. The vision presented by Google and Tesla is one where massive fleets of single-occupancy autonomous vehicles make individual transportation safe and efficient, practically eliminating traffic as well as opening up individual travel for those who currently rely on mass transit like buses. But there’s only so much efficiency that can be achieved when every person on the road has what is essentially a small room of mostly unused space entirely to themselves. “As the world’s population shifts towards cities, it’s a fact of geometry that people in mass transit can be transported more effectively in cities than private single occupant passenger cars,” Timothy Papandreou, the innovation director at San Francisco’s MUNI office, recently told Engadget.

For example, the photo below by dasBild on Imgur demonstrates visually just how much more space 150 commuters take up in cars than in buses.

150 people in 103 cars or in one bus

Whereas the cars use all four lanes of traffic and span the length of several streetlights, the bus fits neatly into one lane and is easily contained in the space between two streetlights. This is something self-driving cars will never be able to fix, but they can help. As Papendreou continues, “It takes a mix of services to make cities work.”

Although often disparaged as unpleasant experiences in popular culture, buses already provide commuters with many of the same pick-up, drop-off services automated car manufacturers are selling as a utopia, all while taking up much less space on the road and producing far fewer greenhouse gas emissions. The difficulty with buses is that while they can drop someone off near their final destination, they cannot transport each specific passenger all the way to their desired stop. While self-driving cars cannot solve traffic entirely, what they can do is help make up for the gaps in our current public-transportation system.

self-driving cars cannot solve traffic entirely

“We’re thinking about planning, and multimodal connections and definitely looking at what’s happening with car shares and taxis,” Kiersten Grove, the strategic advisor on shared mobility for the Seattle department of transportation, told Engadget. The idea is that through a combination of self-driving buses and self-driving cars, roadways will be made more efficient than either travel method could achieve separately. In a sort of hub-and-spoke style system, future passengers may well see themselves boarding self-driving buses to take them across freeways while flagging down a self-driving car for the last mile or so of their commute. Through this compromise, thoroughfares could be safely packed with as many travelers as possible while still utilizing self-driving cars to eliminate the issues surrounding buses today.

The result could be a revitalization of public mass transit, where self-driving cars make up for its weaknesses rather than replacing it entirely. This solution would, of course, present its own difficulties. While the idea of single occupancy autonomous vehicles already presents its own ethical problems, putting an entire bus-full of people in the hands of a single robot driver carries an even greater risk of injury. Because of this, organizations like the California DMV are proposing that human overseers be present at the wheel just in case something goes wrong. “Of course, the driver will always remain present for ultimate control,” explained Mercedes-Benz spokeperson Uta Leitner.

Ultimately, though, the hope is that self-driving cars will help usher in a new wave of public transportation. Freeways filled with single-occupancy driverless cars may never be able to curb traffic quite the way that mass transit can—a road full of driverless cars is still a road full of mostly wasted space. But being able to call in their on-demand individual service to take you from your final bus stop to your office can help take the sting out of the riding the bus every morning, and hopefully encourage more people to make the switch to public transportation in the process.

Bus photo courtesy Vitaly Volkov on Flickr.

The greatest trick the devil ever pulled might be this videogame

What do you see when told to imagine a videogame titled “Pony Island”? Verdant fields of grazing horses, foals nestling by their mothers, others leaping on spindly legs? Sorry, but I have to break this to you now—a game called Pony Island exists and it is nothing like that. The title is deliberately misleading. It’s a game that’s made to build up your jolly expectations and then crumble them, nastily, right in front of your face.

As horrendous as that sounds, stick with it. The creator of Pony Island compares it to 2012’s Frog Fractions which, if you’ve played it and peered behind its illusory curtain, tells you almost everything you need to know about Pony Island. In short: not everything is as it seems.

there’s something not right…

For me to explain Pony Island—which is a task fret with attempts to avoid spoiling it—you need to know that there are, in fact, two Pony Island games. One is the entire game itself that you download onto your PC and begin playing. The other is found inside that game and is only a part of the entire experience. To wit, this second Pony Island is a dull, one-button game in which you make a horse (well, a unicorn, to be precise) jump over hurdles. You do this over and over. It’s meant as a spoof of one of those soul-sucking browser games that appeal to that natural inclination we have towards meaningless progression. However, you’re supposed to get bored of it, and fast.

I don’t feel too bad in essentially spoiling that part of the game as, for starters, it is only the beginning of what becomes a web of reveals that eventually make that initial casual game encounter seem tiny. It’s a semi-detached house in what becomes a metropolis of intrigue and cryptic puzzles (and also faux-glitches). Not to mention that it’s clear, even before you’ve started to play the Pony Island game inside Pony Island, as it were, that there’s something not right… something more going on here. There’s an ominous hum, the pixels are a deathly grey; the game is falling apart before you’ve even started; aesthetically, this isn’t inviting, but in an effect akin to reverse psychology, that the game doesn’t want you there or isn’t ready for you makes it more appealing. There’s a thrill in being the intruder.

But where Pony Island really begins is at the Start menu. It’s an ordinary-looking Start menu. Three options: Start Game, Options & Help, Credits. You wouldn’t suspect a thing. Move your mouse over to ‘Start Game’ and give it a click, however, and with a flash of static it’ll turn into the word “< ERROR >”. This is a perfect synecdoche for Pony Island. You see a typical-looking component of a videogame, but upon trying to interact with it, it breaks or otherwise distorts into something else. Everything is a trickster; part of a puzzle that could have been designed by the devil. And it was. But, oh, I’ve said too much…

You can purchase Pony Island on Steam.

The tragic tale of rugby as a sports game

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

After the 34-17 loss at the Rugby World Cup semi-finals last October, Australian fans could do with some escapism. But if they’re looking to relieve their broken hearts and reclaim the cup through a videogame fantasy, they’ll find that the medium is still working to catch up to the excitement of real life matches.

While annual soccer video games like FIFA plow ahead with authentic ball physics and a realistic facial rendering of Lionel Messi, rugby videogames are admirable mostly for their refusal to quit. Judging from the opinions of players, developers, and critics alike, there is a gulf about the size of the Mariana Trench between the best new soccer games and the latest rugby offerings.

Rugby fans are not alone in their frustration of putting up with bad videogame versions of a good sport. In the sales forecast-driven industry of games there are two kinds of sports games: those written with a capital “S,” and everything else. As far as mainstream videogames are concerned, the sports that matter are the ones that are most popular in countries where people have the largest amounts of disposable income to spend on them: American football, baseball, basketball, and soccer. The rest fall into a class categorized as “other.”

“Other” sports, as the name suggests, is a catchall for sports that don’t draw major attention from game audiences, and they include everything from dirt bike and horse racing, to foosball and cricket. It’s important to note that being “other” doesn’t necessarily reflect on the popularity of a sport. Cricket’s estimated 2.5 billion fanbase, for instance, completely dwarfs that of American football, but because the game is popular in places where few people buy $60 games, such as India and Pakistan, it gets placed in the “other” camp.

For a professional sport to be deigned “other” by the videogame industry usually means that all major publishers with the coin to create a top notch game have passed, leaving smaller studios to fight over the table scraps. According to Jeremy Wellard, the founder of HB Studios, one such mid-tier sports game studio, “there has never been a bigger disparity between the grade one sports and the grade two sports, and the latter is where rugby and cricket sadly reside.”

This is a cause for concern whether you care about rugby and cricket or not

This is a cause for concern whether you care about rugby and cricket or not. Some speculate that hockey is in danger of being exiled to the bottom shelf. Golf is trending in that direction. And tennis simulations have been collecting dust since the early 2010s, save for a PlayStation Vita port of Virtua Tennis 4. Sports fans could be headed towards a starkly contrasted future where a few bright and beautiful games outshine the rickety heap of outdated, subpar ones they stand on top of.

Rugby has already found itself trampled by the cleats of premiere sports games. “It is sad to say it, but it is extremely unlikely that there will ever be a day that rugby or cricket video games match FIFA, Madden, NBA 2K or The Show for technological advancement, sophistication, game mode depth or online play,” Wellard says. While the developers of these franchises have been steadfastly improving their product every season, in Madden’s case for 27 consecutive years, rugby games are released sporadically by smaller, competing software houses, and the result is a discrepancy that smacks you in the face.

This was not always the case. There was a time when there was an optimism for rugby. “We did rugby union. We did rugby league. We did Australian rules,” says Nigel Sandiford, the former president of the Asia-Pacific arm of Electronic Arts. For a run of years roughly between the 2003 and the 2008 World Cups, rugby was in the big leagues, so to speak.

These were the glory days, as Wellard tells it. He and his studio had eked out a tentative alliance where they made the games and Electronic Arts, the world’s largest publisher of sports games, sold them. The relationship had some huge advantages. Namely, they got to build rugby games using expensive technology that was developed by Electronic Arts’ crack team of engineers. Beyond that, the publisher’s involvement meant that a layer of spit-shine was evenly applied to every facet of digital rugby, from realistically rendered stadiums, to character models that were cribbed from FIFA, to motion-captured animations of the players. Even the commentary for once was decent. “That is as close to [the upper echelon of games] as Rugby ever came,” he says.

This is not an “EA is the Death Star of gaming” article. They pulled out because the Venn diagram circle that contained fans of rugby and the other one that contained fans of videogames did not overlap in a way that justified continued support. There were constant frustrations with mothering these games. Among them, the rugby league’s demanded licensing fees that were equivalent to American sport leagues like the NFL and NBA—though the vast majority of rugby games were sold in territories like Australia where the audience was far smaller and less likely to pay.

There could be a resurgence of alternative sports games

“You’ve got no idea how sophisticated the pirates are in the rest of the world,” Sandiford says. “In five days, the pirated copy is out for five bucks. What chance do you stand?”

In their wake, rugby videogames have struggled for competence, but often underachieved. HB Studios’ latest rugby offering, Rugby 15, for instance, garnered an aggregate score of 19 out of 100 on Metacritic—which is considered egregiously bad. But Sandiford expressed a bit of hope that rugby games will return to former glory and compete with the privileged sports games. If games eventually make the transition from expensive consoles to ubiquitous mobile phones, as many predict they will, Sandiford says, things could change. There could be a resurgence of alternative sports games, since people in parts of the world that don’t play games on consoles would have access to them.

If not, “we had our day in the sunshine in a pretty spectacular way,” he says.

Final Fantasy draws a line between games and high fashion

Fashion is basically LARPing at scale. You decide on an identity to take on for the next few hours—a functional person, a grown up, someone loveable, Matt Bomer’s character on White Collar—and then you give it the old college try. Results may vary.

The connection between LARPing and fashion is apparently a two-way street. On Tuesday, Louis Vuitton and Square Enix announced that Lightning, the protagonist of Final Fantasy XIII, would appear in the promotional campaign for the former’s Spring/Summer 2016 collection. The two images released thus far show Lightning holding (“holding”?) purses (“purses”?) at the end of her outstretched arm. The items appear to be made of the same materials as her clothes, making the stills a victory for either computer rendering or high fashion, though probably not both. Anyhow, Lightning looks a fair bit like a model, which is a victory for either computer rendering or high fashion, though, again, probably not both.

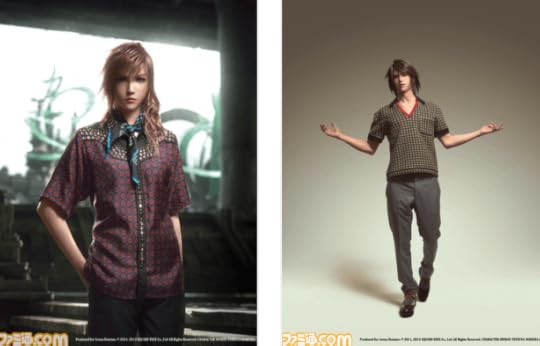

This is not Lightning’s first foray into the world of high fashion. In 2012, the Japanese men’s fashion magazine Arena Homme Plus published a spread in which she wore the latest duds from Prada:

Getting dressed or dressed up is also an opportunity to experiment with identity

Insofar as games can serve as environments in which players try on different identities, it makes sense that they would have a certain overlap with fashion. Getting dressed or dressed up is also an opportunity to experiment with identity, though sometimes the stakes feel higher than a game. This is probably not the synergy Square Enix was interested in, but it is nonetheless the one that comes to mind when looking at the pictures of Lightning.

A photo posted by

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers