Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 183

December 11, 2015

Learn to love again with the Alienware Steam Machine controller

This article was written using products provided by Alienware and the The Alienware Steam Machine First Look program.

It’s been over a month since Kill Screen’s first piece introducing the Alienware Steam Machine and our blossoming relationship, and you’re probably wondering how we’ve been getting along in our new life together.

The answer is, “Very well, thank you.” We’re out of the honeymoon phase, and no longer marveling at how the Steam Machine packs a surprising amount of power into such a tiny and delicate frame. It’s no desktop gaming tower, but it does the things it was designed to do quite well, and it’s got more juice than the Xbox One and PS4 right now.

the bridge between player and game

As anyone who’s been in a long-term relationship could tell you, one of the joys of settling down is the surprising discovery, years down the line, of new things to love about your partner. The latest discovery, in our time with the Steam Machine, has been the controller.

In discussing the Steam Controller, we would like to begin by saying that change is scary and terrible. Remember the first time you picked up an Xbox controller? It was heavy, clunky, and the signature triggers that would establish the Xbox and its successors as masters of the shooting game interface just felt ungainly. It was no Playstation controller.

Of course, the Playstation controller felt like quite the departure as well when all you knew was the Nintendo 64. You remember those, right? Poseidon’s trident made incarnate in a gamepad? The only controller (outside of movie theater arcades) that forced you to continually switch your grip in order to push all the buttons?

Our point is that often, initial feelings of skepticism are founded more on our own fear of change, rather than any rational observations. So when we first picked up the Steam Controller and our first thought was to cry and scream for your mommy, we recognized that as a rash reaction and resolved to stick with it.

If, like us, you’ve been playing basically every game you possibly could with an Xbox 360 controller for years now, your fingers might initially betray you due the lower position of the button pad. The usual second joystick common to most gaming controllers was gone, replaced with a touchpad. It took some getting used to, but eventually that patience was rewarded. We stopped promoting Sauron’s orcs with death after death in Shadow of Mordor, one of the games runnable on the Steam Machine’s operating system. Once we were more acquainted with it, the touchpad offered a level of precision in first-person shooters unheard of on a traditional controller.

But the real game-changer came when we booted up Door Kickers, a game that was never intended to be played with a controller. In situations like these, important keys from the keyboard are mapped onto the Steam Controller, with the touchpad acting as a mouse. It made our brains contort in the way that playing Sudoku for the first time might, but it worked. After a few levels, the controller had become peripheral in that mystic sort of way, no longer physically considered, just the bridge between player and game.

With its totally unique approach to the gaming interface the Steam Controller flits with impressive nimbleness between console imports and games so dedicatedly PC that a controller was never considered. We said in our previous article that the Steam Machine wanted to close the gap between PC and console gaming, and the more we use it, the more we’re convinced that the Steam Controller is the strongest weapon in that fight.

Click here if to check out the Alienware Steam Machine for yourself.

Ever feel like a break-up is the end of the world? This game’s for you

You know the feeling: your relationship has ended. What hope there was of rekindling it has long since faded. The detachment can feel crushing, and a peculiar transience sets in; you’re caught in a netherworld reeling from the loss. You still go about your daily business. You put the coffee on in the morning, you get dressed, and you might have a cigarette. But things are different now. You frequent the same spaces, the same bars and parks, you go to the cinema you’ve always gone to, except they’re tainted; past memories inhabit these places, recollections of shared experiences that are hard to swallow.

The End of the World, by Sean Wenham, is a videogame that takes the player through these experiences, and lets us view the the good times and the bad, in the hope that some sort of acceptance might be found. “Three years ago I had just come out of a long relationship,” Wenham told me. “I was feeling sad and I wanted to play a game that related to my misery the way a sad song does. After hearing (the 1960s country singer) Brenda Lee’s “The End of the World,” an idea formed and I started making this game.”

In the game, players assume the role of a nameless protagonist as he wanders the ruins of Newcastle, a city in the north of England, piecing together recollections of the relationship just ended. “The format for the game came from walking around Newcastle and seeing places we had been together and just feeling and being present in the memories,” Wenham said. “A space really holds someone’s presence after they leave.”

“People will play The End of the World when they need a sad song.”

In Wenham’s Newcastle, classical facades crumble into nothing. Industrial warehouses have fallen into disrepair, the brickwork caving in on itself, the buildings disintegrating before your eyes. What used to be a thriving city is desolate, the population is absent, save for you and your lingering memories. Urban degeneration is a symptom of mental anxiety, and the loneliness is compounded.

But it’s not all doom and gloom; Wenham hopes that “people will play The End of the World when they need a sad song.” It’s a cathartic experience, and also strangely comforting, reminding the player that getting over a break-up is a process, a painful one, but a process in which we need to revisit memories in order to move forward. Ultimately, it’s a message of hope and acceptance, and who doesn’t need a nudge in that direction when the going’s tough?

The End of the World is out now for iOS (App Store) and Android (Google Play). Watch the trailer here.

Modbox expands the playful possibilities of toys with virtual reality

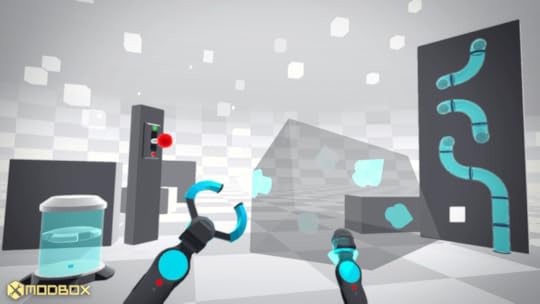

Imagine, if you will, a white empty volume. It’s a room. Now fill it with toys. Stuff ’em in there willy nilly. There’s a basketball, balloons, toy swords, bowling pins, propellers, nets, large die, colorful blocks to climb or topple over. Send a bunch of kids into this room and what do you think will happen? They’ll make up games as they play with each other and these toys, probably having the time of their lives. This is what Modbox will enable, except it all takes place in virtual reality, and that means no one has to clear up the mess afterwards.

Modbox is Alientrap’s VR debut and it shows. I mean that in a positive light. When studio head Lee Vermeulen first played around with the HTC Vive he didn’t have only one idea he wanted to develop for it but several. What stuck out for him about the Vive is that, not only can you move around somewhat freely (rather than having to sit down or stand still for the duration), but you grip a controller in each hand that lets you perform activities with intuitive precision. Experiencing this for the first time saw small “gimmicky ideas” popping off in his head. He wanted to swing a morning star around to destroy things, to stand in a batting cage with a baseball bat and hit things, and launch into a quick basketball mini-game. Modbox is a solution that lets them all exist.

Vermeulen teamed up with artist Harley Price and musician Ryan Roth but, before they stepped in, he started with a physics-based sandbox that let him play around with objects of different weights and materials. “I at first viewed it as just a Rube Goldberg machine creation game, but once we figured out how to allow for player locomotion and added all the toys it opened up to become a general game-making game,” Vermeulen says. “You can edit your level, set up some logic to have things spawn, then hit play to try it out, all online with friends.”

makes it easy to create complex creations.

One of the tiny features in Modbox that makes a big difference to the overall play experience is that, in ‘edit mode’, you can have two objects touch each other, but when switching to ‘play mode’ they will act as if one body. This means you could stick a cube onto a sphere and end up with, uhh, whatever that is. Yeah… Cripes, I hope you’re more creative than me. Vermeulen talks it up better, saying that this feature along with the two controllers makes it easy to create complex creations. “In the past setting up this stuff with a keyboard and mouse was painful, it’s hard to position stuff right unless you have all the gizmos and shortcuts of a modelling program,” he says. “With this, though, you can just naturally position it and start wiring things together.”

If you’ve played any of Vermeulen’s other games, such as Capsized, Apotheon, or the upcoming Cryptark, you’ll know that he loves making 2D action spaces that encourage creative destruction. While Modbox is a first-person sandbox, it really isn’t that different to those other games. Everything is destructible in Modbox. You start with the primitives—basic 3D shapes—stick them together to form larger objects such as a table or a house, and then you decide what material they are. It might be metal, wood, or glass, and they each have a different look, density, and friction, but most importantly it determines how easily that object will break. Vermeulen tells me that it takes a massive amount of force to break the metal, making it clear he’s had a lot of fun trying to do exactly that. His argument is that the destruction makes the world more tangible. Which, yeah, I’m sure it does, but I think it’s obvious that Vermeulen put destruction in there as he likes to smash things with a hammer until they break.

Sure enough, it doesn’t take him long to get onto his tales of smiting inanimate objects with his new videogame powers. This happens when he’s telling me about the “toys,” which you can pick up and have replace your little robot pincers that represent your hands inside the game. “Guns, chainsaws, boxing gloves… I especially love the Chainsaw and Crossbow right now,” he says. “With the chainsaw you actually have to pull the ripcord to start it, which feels insanely cool. And with the Crossbow you have to pull back the string each shot. Everything having all these fun things to interact with is really satisfying.”

After having acquired a HTC Vive on October 15th, developed Modbox through November—but not before creating a destruction sandbox first, of course—Vermeulen’s work with virtual reality has moved quickly, and now the plan is to bring it to Steam before the HTC Vive launches publicly in early 2016. The reason for beating the virtual reality headset’s wider launch is due to wanting there to be user-made content already available for people to try out when they get to it. Yes, it will have Steam Workshop integration so you can create contraptions and then easily share them with everyone else who is playing.

Still, that isn’t the main appeal of Modbox. Vermeulen is clear about what he things that title belongs to. Hint: It’s the freedom to play however you want. “When I am playing with friends I don’t think I need some structured game with points and systems—all we need is toys and the environment to have fun,” he says. If we wanna play basketball all we need is a ball and a net, and we can keep the score.”

Modbox will be available on Steam for the HTC Vive in early 2016.

The Legend of Zelda, now 75% less interesting

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds was the best Zelda game in a decade. The Legend of Zelda: Tri Force Heroes takes the engine from Between Worlds, contorts it into a multiplayer game, and does a disservice to its forebears in the process.

Tri Force Heroes (2015) works in the spirit of Four Swords Adventures (2004), but is of an entirely different moment in gaming culture. Four Swords was about sitting on the couch, fending off enemies and solving puzzles in person. But two things happened since 2004: I got older and gaming got more solitary. Why? The internet is the answer to both.

If Heroes is meant to be a corrective to the lonely nature of Zelda—the multiplayer answer to the single-player quests we know so well—it merely takes all of the pleasure of mastery that attends a Zelda game and distributes it among three capable players, who are then immediately rendered incapable by being forced to work together. The puzzles in Heroes are, in a word, obvious, and that insult stings a lot worse when the only thing keeping you from solving it is the people you’re stuck playing with. Playing Heroes feels like I imagine being a climate scientist testifying before the House of Representatives would: the answer is clear and immediately before you, but one of these assholes just keeps throwing you into the ravine.

I’ll concede that it’s possible Heroes’ random assignments could work if you play with a team over a long period of time, but the turnaround was such that I would get a new group almost every level, requiring us to generate new conventions for teamwork from round to round. While I appreciate Nintendo’s efforts to make a sign system for Heroes, trying to strategize about teamwork through GIFs is predictably disastrous. Fist pumps as “hooray” is clear enough, as is the “help! over here!” symbol, but what of the hopelessly polysemic Link-with-quizzical-expression? Are you just shouting your uncertainty into the void? Is this Tri Force Heroes for “existential crisis?” To get a sense for this, imagine trying to write an essay in ASCII or tell your partner where you think you should go for dinner in semaphore. Now do it while you’re fighting monsters, shooting crystals, lighting torches, etc.

To get a sense for this, imagine trying to write an essay in ASCII

But Heroes’s oddest design choice is surely its violation of a Zelda tradition since time immemorial (i.e. 1986): Link can’t jump. If Link could leap over a rock or hop up on a ledge (in the way he can nevertheless jump-attack with his sword), 50% of the game’s puzzles could be avoided. But he can’t so they aren’t—and they are so he can’t; it’s rather self-reinforcing. And, as obeisant to videogame illogic as this may be, we dutifully accept it. Link can’t jump.

Before you’re scandalized, Heroes doesn’t allow any of its three Links to jump. But it does fundamentally change the series’s level design to make seemingly every room into this three-layer cake, where you have to get your friend to come over and stack up into a little tower so the person on the bottom can throw the top two onto a slightly higher ledge, and the second can throw the third onto the highest ledge, so they can go smack a switch and you can get on with your lives. Each level is designed for a game with a character who can jump, but Link can’t jump, so elementary platforming is rendered as tedious stacking, throwing, and re-stacking/re-throwing as people continue the stream of tiny fuckups that constitutes an hour spent with Heroes.

And yet the most frustrating thing about Heroes is that the problem it addresses doesn’t even need to be solved. Zelda’s solitariness isn’t lonely. It’s directly in line with the tradition of the epic (if somewhat scaled back for our postmodern skepticism of metanarrative). But really: Link is the hero of time, his people, the chosen one, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. His actions are world-historical. His value as a trope is directly linked to his unique (and I mean this in the sense that there is exactly one of him in a given game/diegetic time) heroism. The pleasure of the romance and the fantasy comes from the individual defying the odds, systems of power, history, etc. Splitting the responsibility for that action across three doesn’t make it more fun; it makes it less meaningful.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Dedicated LEGO fans build an impressive animated Sisyphus sculpture

When I first saw JK Brickworks’ “Sisyphus Kinetic Sculpture,” I was floored by how smoothly it moved. My primary experience with LEGO, like many, was as a stationary medium, and yet here I saw a piece of art made entirely out of LEGO bricks moving with the fluidity of a Disney animation. As I was to discover on JK Brickworks’ site, this immediate comparison is no accident, as the project was inspired by a 3D modeling program from Disney Research that allows both artists and non-experts alike to plan out mechanical characters in a virtual space before constructing them in the real world.

The sculpture, which features the Greek mythological character Sisyphus pushing his trademark boulder, as well as a Greek relief art style retelling of his life built into the base, is made possible thanks to a surprisingly simple, albeit still impressive, system of gears and pegs. It can be powered either through a battery and motor or by a hand crank, to give the operator that true Sisyphus feeling. Turn and turn and turn, that boulder’s not going anywhere.

Jason Alleman, who founded JK Brickworks along with his partner Kristal (from whom the ‘K’ in the name is derived), writes over on their site that while he has been a LEGO fan since his childhood, his adult fascination with the project really began when LEGO released their Mindstorms programmable robotics system and acquired the Star Wars license in the late ‘90s. Now, Jason, Kristal, and their friends create mind-boggling LEGO builds like their Sisyphus sculpture on a near-monthly basis, most of which are mechanical in nature. Together, the team has built such projects as a working combination safe, a functioning AT-TE walker from the Star Wars films, a cookie icing machine, and a giant model spaceship entitled the NCS Aries-K, complete with spinning gravity generator.

To see more moving LEGO sculptures and even find instructions to build many of them yourself, head on over to JK Brickworks’ site.

The pointless scale of Xenoblade Chronicles X

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

A few months ago, The New York Times and several other outlets ran a story about an unlikely extinction happening in Japan: the Aibo, a robotic dog manufactured by Sony, was slowly but surely dying out. The company stopped repairing them in March 2014 due to a scarcity of spare parts, leaving Aibo owners unable to do much to resuscitate their moribund companions when technical failure eventually occurs—as it inevitably will. As a result, some owners are already holding Aibo funerals, mourning the loss of an object that received as much emotional investment as any flesh-and-blood canine. As the officiant at one of these funerals, captured on video by the Times, intoned, “The inanimate and the animate are not separated in this world. We have to look deeper to see this connection.”

Has Tetsuya Takahashi ever owned an Aibo? His games make me wonder, because they seem hell-bent on examining—and in a lot of ways, dissolving—the philosophical boundaries that intercross at a funeral for a robot dog: boundaries between the inanimate and the animate, the organic and the synthetic, the familiar and the alien, the physical and the spiritual. His career in JRPGs began with his designs for the Magitek armor in Final Fantasy VI, marking the series’ first flirtation not only with sci-fi but with the idea of a human-machine interface that called humanity itself into question. After that, he took the reins and directed Xenogears, a sprawling, philosophically ambitious JRPG about humans, robots, and God; then Xenosaga, a sprawling, philosophically overambitious three-part saga—it was supposed to be six—about humans, robots, and God; then Xenoblade Chronicles, a game of beautiful and surprising restraint that neatly allegorized the same big questions about … well, you get the idea. In Xenoblade Chronicles, you play as dwellers of the Bionis, an organic titan frozen in perpetual conflict with his robot nemesis, Mechonis. The Mechon are your enemy. And yet, some of them have faces. Some of them have human voices—albeit angry Cockney ones. Could it be that this elemental conflict between flesh and metal isn’t as elemental as it seems?

Xenoblade Chronicles was a triumph, but it was also always going to be an exception: a JRPG crafted for accessibility at a moment in the genre’s history when it, too, like the Aibo, might’ve seemed like a fetish object with a cult following whose days were numbered. The game worked. The story was as simple and complex as a fairytale; the systems were traditional yet reformist, distilling everything that makes JRPGs feel so alive despite their studious, often baffling artificiality. The translation of basic party strategy into impossible, flamboyant combos. The feeling of exponential—not linear—development: at level 1, you’re fighting crabs; at level 70, you’re fighting God. The essence of the horizon: to not know exactly where you’re going, and to be thrilled when there’s another place to go.

Xenoblade Chronicles X is big

Xenoblade Chronicles X retains almost none of that. The game is in every single way a disappointment. And maybe it’s unfair to compare it to its “spiritual predecessor” when that predecessor was so self-consciously exceptional in the first place. The game is a lot more like the worst parts of Xenogears and Xenosaga: overambitious and therefore incomplete; addicted to clunky, interminable exposition rather than the (relatively) subtler medium of capital-A Allegory; geared toward placating only the most veteran JRPG players rather than serving as an ambassador for the genre to everyone else. At the same time, I think its greatest failure has more to do with the big themes that bind together all of Takahashi’s games, Xenoblade Chronicles included. Everything about it is so synthetic that it has no possible way of being organic.

Xenoblade Chronicles X is big. You’ve probably heard that already. The game takes place on the planet Mira, where humans aboard a giant ship named the White Whale—like MGSV, the game is strangely preoccupied with Moby-Dick—have crash-landed after fleeing the destruction of Earth. Your task is simple: find the Lifehold, the part of the ship that contains the majority of its human population in stasis. The White Whale itself was pretty big, but Mira is bigger, comprising five huge, freely explorable areas with different climates that the game wants you to think of as continents. There’s Primordia, which is like a radically expanded version of Xenoblade Chronicles’ Gaur Plain; there’s Noctilum, a bioluminescent megaforest ripped straight out of Avatar (like many of the game’s fauna, which look like gross, lizardy alien versions of Earth animals, and also like a few of its characters: Vandham, the game’s gruff commander figure, is essentially a nicer version of Stephen Lang’s mech-suited imperialist asshole). Oblivia is perhaps the most captivating environment, a desert landscape punctured by the enormous wreckage of ancient alien ships, which become mountains in themselves. Much of the game—scratch that: the game’s essence—is about exploring these stark, concept-art wonderlands, first on foot, then in a mech-suit (“Skell”) that doubles as a car. And then by air.

The game provides proof of its own concept the first time you fly directly, seamlessly, from the streets of New Los Angeles (the game’s only human colony) to the highest peak in Primordia, high above the lakes and plains where the bizarro brontosauruses roam. It really is an amazing update to the airship in RPGs of old, or the heavenly wings in Dragon Quest VIII—that moment when you finally master the scale of the world, after struggling in the beginning to walk across a fragment. (In that respect, given genre tradition, the fact that you only get the ability to fly around 40 hours into the game makes sense.) Unfortunately, the sublimity of that moment is shadowed by the ever-present sense that it really is the game’s point, pursued with monomaniacal, Ahab-like fixation. Xenoblade Chronicles X is a game of great scale. But scale means nothing when it’s pursued for the sake of scale.

The game might be “big” in a literal sense, but it feels very small in a conceptual and emotional sense. Part of the reason is that you can traverse it at great speed, effortlessly and weightlessly, like some sort of hyperactive space squirrel: it doesn’t really matter that you’re crossing a plain that’s five miles wide if you can run at 60 miles per hour. But the other problem is the GamePad, and everything it represents. You’re always holding a map screen that not only tells you a lot about the five continents from the get-go (including where they are, what environmental theme each one falls into, and what kind of enemies to expect), but divides the world into a rigid grid of hexagons. Place more “data probes” in each area, and the hexagons will fill themselves with potential tasks: kill a giant monster here; find a treasure there. Each area map prominently features a percentage counter that records, to a double-decimel, the completeness of your “survey” (which means not just how much stuff you’ve found but how many sidequests you’ve done). For a game explicitly about exploration, its world feels profoundly pre-explored. Even worse, it turns exploration itself—ostensibly all about encountering the unknown—into systematic busywork that revolves around a literal checklist.

For a game explicitly about exploration, its world feels profoundly pre-explored.

Final Fantasy XIII’s Pulse, that wide-open area at the end of a game so notorious for its stifling linearity, “felt” bigger than anything you can traverse here—in part because, in that classic JRPG move, it was a space that wasn’t available at the beginning of the game, a suddenly and dramatically expanded horizon. Think of the bigness of the overworld after 10 hours spent in the streets of Midgar. Think of a world with one continent suddenly becoming a world with four in Final Fantasy IX—that quintessential example of the JRPG’s Magellan effect. There’s nothing dramatic about the scale of things in Xenoblade Chronicles X—nothing revelatory, nothing sudden or strange. You’re not really exploring. At most, you’re collecting, through the mediating screen-door of the GamePad’s insistent clutter: this vista and then that one; this cave, this promontory, this rock. And it’s all empty, depopulated, unsatisfying—including New Los Angeles itself.

That still wouldn’t be a huge problem if the game had a narrative that transcended its busywork structure, but it doesn’t: the story is simply one giant, prolonged exploratory task, interwoven into the web of tasks you’re doing already. Why do we need to look for the Lifehold? Because Mira is so big! What do we need to do to find the Lifehold? Explore more of Mira, because it is so big! Every single thing in the game is rooted in the same obsession with sheer expansiveness—the same misguided ethos that seems to believe that expansiveness is a virtue in itself (No Man’s Sky, take note). On the level of battles, gear, and stats, this ethos manifests as infuriating abstruseness—a tendency to add systems on top of systems, complexity for the sake of complexity. The battle system is a cluttered mess; as a testament to its redundancies, consider the fact that your HP appears in two places on the already-crowded screen. Things do eventually click; if you’re like me, you’ll feel hugely satisfied when you “get it,” in the same way it feels good to untangle a giant ball of Ethernet cables and AC adapters.

But a lot of the complexity feels not only pointless but actively oppositional, as though indirectness were also a virtue in itself. As you plant more data probes, they start to yield “Miranium,” a resource that can be used to invest in arms manufacturers—another system, apparently borrowed from Borderlands—which will then eventually produce better gear. Every half hour, you receive more Miranium from your precious probes, until you reach a cap that can only be increased by “storage probes,” at which point you have to return to NLA and invest your stockpiled Miranium. You cannot buy storage probes, despite the mundanity of their function; you can only find them or receive them as quest rewards. In practice, all they do is stifle you. Why do they even exist? Why not uncap the amount of Miranium you can mine every half hour—isn’t time already a limiting factor?—so that you don’t have to return to NLA over and over again? There’s only one answer: because having another kind of probe in the game means having more of something.

Here’s another example of needless, obstructive addition. Xenoblade Chronicles streamlined standard JRPG practice for the better by reviving dead parties almost instantaneously at the last landmark they visited—or, in a boss fight, nearby. Xenoblade Chronicles X does the same thing when your party dies on the ground. But if anyone dies in a Skell, a whole set of brand-new systems come into play. The Skell is destroyed, which means you have to go back to NLA to salvage it. In the best case scenario, you pay nothing because you still have “Skell insurance.” In the worst case scenario, you pay hundreds of thousands of hard-earned credits to gain back the Skell you already paid for—in a game that makes dying in a Skell about as easy as dying outside one, depending on the creatures you try to fight (or the creatures that decide to fight you, because you were in the wrong place at the wrong time in a game about … exploration).

It ought to remind us of what’s so good about the maximalism of other JRPGs

All JRPGs have bullshit like this in some form. The best ones find some way to coat their bullshit—the grinding, the fetch quests, the arcane systems—with a sense of epic urgency, or an atmosphere of against-the-odds oppression. The best Xenoblade Chronicles X can do in this regard, on the level of ludo-narrative continuity, is to remind you of your own insignificance: Skells are expensive, “storage probes” are prohibitive, Mira is already half-charted, because you are just a random human on NLA’s payroll, working toward a project that transcends you, a project on a greater scale than the individual self. Unlike its predecessor, which centered (like so many JRPGs) on a teenage messiah chosen by the divine, Xenoblade Chronicles X takes great pains to remind your customized avatar that he’s only one member of one team in one section of an eight-division organization called BLADE—an organization in which you can choose to be a monster hunter just as well as a miner, a social worker for NPCs, or a collector of little plants and alien garbage. In Star Wars Galaxies, it was interesting and cool that you could be a Jedi as well as a bartender. But there were other people in Star Wars Galaxies. Here, for all the game’s attempts to mimic MMOs, the multiplayer is mostly asynchronous—and besides, your division does almost nothing to determine what you actually do. The game’s pervasive anti-individualism is definitely something different, but it derives from the same obsession with scale that seems to have informed every other aesthetic, narrative, and design decision. BLADE has eight divisions because it wouldn’t feel big enough with four.

Where exactly did this obsession come from? It seems simultaneously rooted in a desire for realism—as in a game environment built “to scale”—and a desire to transcend realism, to be bigger than life. It accomplishes neither. If anything, the one thing it does accomplish is to remind us of the folly of maximalism for the sake of maximalism in games, where it’s an all-too-prevalent design philosophy that steals resources, and the spotlight, from other forms of aesthetic ambition. It reminds us of the same problem in any other medium, from panoramic triple-decker novels that assume that panorama itself is a virtue to three-hour superhero movies (or expanding cinematic universes) crammed with characters. And I think it ought to remind us of what’s so good about the maximalism of other JRPGs, Takahashi’s included, which always go big but seldom assume so blithely that size is everything.

The best JRPGs transform the synthetic into the organic, somehow creating pathos through artificiality and yoking abstract systems—repetition, machinelike behavioral loops—to melodrama. The best JRPGs have the potential to teach us a lot about precisely the things that seem to preoccupy Takahashi in game after game: the humanity of the inhuman, from objects to robots to videogames themselves; the inhumanity of what we tend to call human, given that the human self always seems to rely on things outside it, things unlike it, to give itself form, definition, and weight. This JRPG asks us to do nothing except buy into its synthetic religion of scale. You are big, Xenoblade Chronicles X. You are big because big is good. It’s like stroking a dead Aibo—an Aibo that was never alive in the first place.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

December 10, 2015

Way To The Woods, a beautiful upcoming videogame about two deer

When I was 16-years-old I think I was hiding bottles of whiskey in a make-shift compartment I’d fashioned out of a flat-pack desk in my bedroom. My ambitions involved finishing school and getting drunk. I was probably considered a hopeless if academically successful wreck. This is only confirmed by seeing what other 16-year-olds get up to. Specifically, the 16-year-old Melbourne-based artist Anthony Tan who is making a beautiful videogame called Way To The Woods by himself. This is flabbergasting.

Way To The Woods is described as a third-person adventure that follows a mother deer and her fawn as they travel through a “strange place.” By the looks of the screenshots, this place is the post-apocalyptic ruins of humanity; run-down public bathrooms and train tunnels abandoned except for the curling green fingers of nature as it takes back over. It’s hardly a stretch to see the similarities in these environments to those traipsed and fought through in The Last of Us and, indeed, that is where some of the inspiration for this 16-year-old’s project comes from. Others include teen drama videogame Life is Strange, and Miyazaki’s animated classics Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke.

As pleasant as it all looks, it seems that the titular journey to the woods with these two deer won’t be all peace and quiet. Another shot shows a pack of wild dogs (or wolves?) baring their fangs in a dark underpass. There will be danger. Which also makes it very similar to Might & Delight’s two Shelter games, both of which had you playing as a mothering animal safeguarding their young in the wild—in the first it was a badger, and in the second it was a Lynx.

“the most gorgeous thing you’ll see today.”

Way To The Woods has been in the making for about a year and its young creator is currently awaiting for a response to his application for a Unreal Dev Grant to continue working on it. While “nervously waiting,” Tan decided to share some new screenshots of the game that you can see here. And it’s these that caught the eye of No Man’s Sky programmer Sean Murray, who brought fruther attention to Way To The Woods via a tweet in which he described it as “the most gorgeous thing you’ll see today.” He’s probably right.

You can follow the development of Way To The Woods on its Tumblr page. It’s only confirmed for PC at the moment.

Bird lawyering game Aviary Attorney to flock to Steam next week

You might remember Aviary Attorney as the only lawyering videogame that features a crack team of attorneys straight out of Animal Farm. Set in 1848 Paris, the game only uses public domain drawings from that time to depict the trials and tribulations of bird lawyer Monsieur Jayjay Falcon. All characters have been lifted from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux (Scenes of the Public and Private Life of Animals), by French caricaturist Jean-Jacques Grandville.

As Aviary Attorney creator Jeremy Noghani told Kill Screen after the Kickstarter launched a year ago, “It was amazing how much of the humor carried across from 170 year-old drawings.” Since then, the Sketchy Logic team has created a colorful band of characters for Monsieur Jayjay Falcon to lawyer.

For example there’s Juan Querido, the Prince of Spain, who is accused of murder and conspiring to kill the king of France. Juan is a suave, collected fox with a rye smile permanently plastered on his lips. Meanwhile his majesty King Louis-Philippe of the House of Orléans appears to be a no-nonsense penguin with a strong sense of propriety and dignity. In the devblog, the entry introducing King Louis-Philippe of the House of Orléans (the first of his name, protector of the realm) is filed under category NothingBadEverHappensToFrenchKings—which sounds less than promising for the poor penguin’s head.

Unfortunately, all they have is you, a bird-brain

In Aviary Attorney, you must take on a a variety of clients who require excellent bird lawyering throughout Paris. Unfortunately, all they have is you, a bird-brain. You’re caught in the middle of a French revolution, and the way you play affects the outcomes of the case. From courtroom drama to dangerous sleuthing, you must out fox the fox, out caw the crow, and out best any other animal who stands in your way.

The game will be released on December 18th on Steam for Mac and PC.

Can India become an eSports powerhouse?

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

The eSports fever that has taken the world by storm is largely driven by its popularity throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas. But there are still billions of people on the sidelines in countries where competitive gaming has yet to take off. India, the second most populous nation on the planet, for instance, is one of the more prominent holdouts. As of the time of this writing, there are exactly zero players residing within the country who play eSports for a living. While pro players elsewhere in the world can bring in a hardy six figures, in the past three years Indian nationals playing in Indian leagues have garnered just 973 dollars and 40 cents.

However, it would be a big mistake to sleep on India. There is growing enthusiasm that the country will soon rise up and establish itself as a legitimate contender on the international scene. Just the latest example is , the 14-year-old wunderkind, who recently traveled from Hyderabad to New Orleans to play in Call of Duty World Finals, making him the first native Indian to compete on Major League Gaming’s big stage.

Sandeep Aurora, the Marketing Director of South Asia Intel, is one of many who believe that we are on the threshold of an insurgence of eSports in India. “Even in it’s nascent stage in India, [the] eSports space is steadily heating up with an increasing number of recognized competitions,” he said. “While India is still gearing up for better performance in the field of eSports, we believe that there is tremendous scope and it is just a matter of time before our country starts to shine in this realm.”

Undeniably, there is a buzz around Indian eSports. The biggest publishers, promoters, and broadcasters in eSports, including ESL, Valve, Wargaming, Riot, Twitch, and Azubu, have all courted the region. The reason is obvious. India is home to 1.2 billion people, with cities that boast populations larger than smaller European countries. It is easy to imagine this massive groundswell of humanity rising in unison to clash with other great nations at matches of DOTA 2, FIFA, and Counter-Strike (the three most popular eSports in the country).

its greatness is still in the visionary stage

The only problem: its greatness is still in the visionary stage. Ten years ago, Akshat Rathee, the founder of India’s largest eSports promoter, NODWIN Gaming, was among the first wave of Indian eSport players, and according to him, they were notoriously bad. “We kind of sucked,” he said, describing the scene as Indian minnows sent to be slaughtered by the Koreans. “We became as bad as we are in soccer, which is, say, 152nd in the world.”

But eSport players in India are no longer green behind the ears, and the level of competition has improved quite a bit. These days, the best Indian players tend to fall somewhere in the middle of the pack. At the time of this writing, the top Indian Counter-Strike team, NeckBREAK, was ranked a respectable 88th out of a global field of 226. However, Indian teams are still trying to get over the hump and experience a breakthrough signature win. When NeckBREAK faced off against the Australian team Renegades at the ESL One Qualifiers earlier this year, they were humiliated, failing to score a single point.

Despite this, Rathee is confident that India will produce an eSport champion sooner than later. One reason is simply that it is far more practical to play now that the Internet is widely accessible. “Ten years ago, eSports were like golf. It was just for the elites who could go out and afford it,” Rathee said. Stringent data caps pose an issue for playing the thousands of hours necessary to become an expert.

Still a bigger reason is that India herself is changing. The third generation of Indians, who are driving the interest in eSports, are becoming more ambitious about following their passions and pursuing careers in untraditional professions. “We’ve seen this generational change, where parents are OK with their kids playing videogames, because they played a little Mario, a little bit of Contra. We are that generation,” he said.

It is his opinion that India needs a few more years to get to the peak level where they can compete. “It might take another 5 years for people to say this is as good of a career as cricket,” he said. Like anyone in his position, he has projections and estimates that are perhaps a bit bullish. In two years he hopes that India will have 200 professional players, ten gaming houses (think: MTV Cribs for eSport teams), and two players breaking the million dollar mark. He sees the teams sticking together long enough to develop finesse and teamwork.

If that happens, the rest of the world better watch out.

A videogame in which the city is the protagonist

The city in A Place for the Unwilling is alive. It may even be possible for it to die. The streets and buildings make up its physical form as bones and muscles and arteries do ours. The population is its life force; rushing like a bloodstream through the alleys and avenues, occasionally stopping for conversation next to a monument or under a streetlamp. The city hears them whispering each other’s names, it feels them moving around inside of it, and more recently it has felt something darker and twisted lurking within it.

The idea in this upcoming narrative adventure is to explore this city, to discover its dozens of stories, and to play a part in the events that will shape its future. It’s a concept not so dissimilar to the many RPGs that promise you a crucial role in deciding a world’s fate. But where A Place for the Unwilling finds promise of its own is in shrinking that scope down to a single city. It’s intended as a rich, singular architectural essay in the same way that Fritz Lang’s Metropolis might be. This focus emerged naturally from the curiosity of the game’s three creators at AlPixel Games. “London, Madrid, and Paris are all different, but not only because of their monuments or shops; we could say each of them has a ‘soul’ which makes them unique,” Luiz Díaz, the game’s designer says.

turns the urban landscape into a kind of biological creature

AlPixel Games wants to delve deeper into this line of thinking; a city having a life of its own. Not only conceptually but actually. If you head into the poorest neighborhoods in A Place for the Unwilling‘s city you’ll see cheap houses “growing” on their own accord, without any of the urban planning it usually takes. Observing architectural quirks such as this is how you’ll gradually come to understand the city. There will be no mini-maps or destination markers to guide your way. Nor will there be anything gratuitous to distract from your aimless wandering such as puzzles to solve. And so, as the game turns the urban landscape into a kind of biological creature, its narrative is similarly organic as you find your way.

Through exploration alone, you should be able to figure out that there’s a tension between the city’s different areas, a divide between its residents. Using Victorian cities as a model when designing this virtual one has meant that squalor and plague infests some of its sections, while the richer areas are cleaner and is home to those who know only luxury. This inequality will perhaps be the most visually and thematically obvious characteristic of the game’s city but there will be much more to find. “The smallest details are one of our main focus, we want you to see the silhouettes on the windows and even be able to buy a newspaper and read about what happened the day before or what might happen that day,” Díaz says.

A city wouldn’t be much without its populace, of course, and A Place for the Unwilling does represent them, albeit in an unsettling form. The presence of strangers is visualized as shadowy figures that you can talk to but only to ask for directions. Until, that is, an important event happens and you hear their name, causing the shadow to fade and reveal the person below. Only then can you discover more about these previously faceless forms.

It’s implied in the game’s description that revealing people and experiencing events is how you’ll steadily move this city towards its conclusion. Although it seems that will happen anyway with or without your input. Díaz and team reference Pathologic and The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, both of which have in common a time-based structure, giving players only a number of in-game days to prevent a disaster. It seems that A Place for the Unwilling will enforce similar restraints when asking you to explore its city and affect what ultimately happens to it.

You can follow the development of A Place for the Unwilling on the TIGSource forums.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers