Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 185

December 8, 2015

A narrative experience where you are the cancer

In an interview for The Guardian, Ryan Green, one of the developers of That Dragon, Cancer, said, “We’ll have less games about saving the world and more about saving your child.” As developers and audiences grow older, more personal stories start to appear as subjects in games, led specially by the independent games movement. Apoptosis is a game that follows this path, telling the story of someone close to a cancer patient while offering us control of the spreading disease.

it challenges us to continue the path of a disease

The French team behind Apoptosis—François Rizzo, Lucien Cantonnet, Marjolaine Paz, and Gaspard Morel, from ENJMIN school—decided to give the player control of the cancer to contrast the uneasiness of spreading the illness with the expectancy of knowing more about the story and the relationship between a couple. The player only has to click on the organ to continue the path of the cancer. “Even though the expansion of the disease can be graphically pleasant to watch, the interaction has to be practically uninteresting in order to have meaning. It had to be the opposite of fun,” they write on the game’s site.

Apoptosis is a narrative experience of ten minutes that relies on a well-written script by Rizzo, initially only in French. Taking the view of a person close to the disease, and not the patient himself, the game uses this opportunity to talk about how the cancer is also a burden to those who care about him and not an individual experience. The team has recently made an English version that also features the work of a voiceover actress.

One of the special traits of games is that, unlike movies or literature, they are able to make us feel pride, sorrow, or guilt by providing interaction. Apoptosis is an example of the latter, as it challenges us to continue the path of a disease while giving immediate feedback on the patient’s health. We can find games about death everywhere, but what makes the current approach of independent games feel new is their ability to tell a personal story and give us a close look of its consequences.

You can download Apoptosis for free on itch.io.

Prominence has old-school sci-fi vibes, but it’s short on story

In January 1957, J.G. Ballard first published his story “The Concentration City” (then under a different title) in a magazine called New Worlds. It takes place in a city that spans the entire universe, where streets stretch out both horizontally and vertically, with lifts and levels expanding the city infinitely in every direction. Talk of real estate doesn’t just involve two-dimensional plots of land, but is priced and measured in cubic feet, so that even the air you breathe costs money. The biggest threat to life in this city is terrorists called “pyros,” the embodiment of a violent human impulse that seeks to explode order to replace it with a kind of meaningful chaos (a recurring motif in much of Ballard’s work).

“The Concentration City” doesn’t turn out to be the most elegant story by a writer with a career like Ballard’s. Is “The Concentration City” a perfect name for a story? Nope. Is a world where every cubic foot of free space has a price a great metaphor for the ceaseless onslaught of capitalism? It’s a little heavy-handed. Does it take a huge imaginative leap to invent a world with streets numbered in the millions, rather than the hundreds? Meh.

truth about the logic behind contemporary life

Still, it is animated by some spark, of a kind that all good science fiction has. It isn’t compelling because it strikes you as an accurate prediction of our future, but because it conveys in surrealistic terms some truth about the logic behind contemporary life. We don’t expect that the future of humanity will involve a universe-sized city, but we relate to the feeling of extreme claustrophobia, of the slow simmer of anxiety underlying city life, of the frightening velocity sensed in creeping urban sprawl.

This spark is mostly missing from Prominence, a recent point-and click-adventure game from independent developers Digital Media Workshop. Prominence suffers from an unfortunate dearth of vision, both in terms of its genre and its story—especially unfortunate because science fiction has always been about, if nothing else, vision. Sci-fi often resorts heavily to tropes of inner and outer exploration; it wrangles with politics and promises of utopia; and from the outset, it demands that its readers, viewers, or players confront something unknown or (pardon the pun) alien. You can find some of that in Prominence if you look very hard, but the sad fact of the matter is, the game makes these questions mostly incidental and roundly refuses to elaborate on them as you play. (It’s tough to demonstrate this point without getting into some story spoilers, so if you’re still interested in playing Prominence, you might skip the next two paragraphs.)

And this isn’t for a lack of opportunities either. As I see it, Prominence’s story passes on two great chances to weigh in on a genre-defining question that science fiction has been preoccupied with for decades: the possibilities of artificial intelligence. For starters, it’s confirmed in a fairly predictable twist about a third of the way through the game that your character is actually a medical droid that was temporarily incapacitated in the solar event that forced your crew to evacuate the ship. ANNIE, your HAL-like partner that leads you through the game, notes that the solar event has caused some changes that are allowing you independent thought. However it happens, the idea that a humanoid machine could become self-aware and act both rationally and emotionally is fun to spend some time with. But the game pretty much just skips past it, only giving you one shot at exercising your independence toward the end of the game. The game’s exploration of this issue ends up looking pretty much like this: you find out you’re an android, and now you’re imbued with higher cognitive powers. Cool story.

Then there’s ANNIE, the artificial intelligence of the ship’s central computer. You could see the fingerprints of 2001: A Space Odyssey on this aspect of Prominence even if it hadn’t already been noted that the developers drew influence from Arthur C. Clarke for the game. But where HAL gets elevated to the ultimate coldly rational thinking machine—one that counts human nature as frivolous, sentimental, and dangerous—ANNIE never develops into anything terribly interesting. ANNIE mostly guides the player through her objectives, commenting on the player’s impressive new capabilities and only lightly questioning the player if she takes her single opportunity to act against ANNIE’s will.

Prominence isn’t so much a failure as it is a missed opportunity

The question of vision less troubling where it concerns genre, since Prominence is deliberately old school in its design, a throwback to classic point-and-click adventure games like Myst. Your invisible avatar can look around in discrete three-dimensional scenes, searching for items to interact with or tools to use for later, and then you can click in one of a few different directions that will lead you to the next space. The shot of nostalgia isn’t necessarily unwelcome. The problem, however, is that Prominence is very content sticking to its old-fashioned guns, and as a result, playing it feels stale. Outfitting a game in retro-style is all fine and good provided you can deliver an exciting experience (see Downwell), but if the game design doesn’t feel at least a little fresh, you’re going to need some good storytelling to carry you through.

Which brings me back to the bigger issue: the story of Prominence just isn’t there. It’s fairly anemic—short on any meaningful conflict and maintaining too little inertia to keep the player motivated. If there’s any kind of motivation to speak of, it extends only from pursuing your objective (just roughly outlined for your character) to save an interplanetary mission and its marooned crew. While that may sound like something, it’s also a little too familiar, and it all takes place within a story-world so sparse that it fails to gain any traction.

To a significant extent, this is true because the story literally isn’t there. Much like the decision of the Destiny developers to post all of that game’s lore and story resources online and nowhere in the game, Prominence developer Digital Media Workshop has been releasing a set of prologue materials on their website to provide players with more context on their story-world. The gesture is appreciated, but it’s not doing Prominence any real favors, as you can’t help but feel like it all should have been in the game in the first place. As it stands, the in-game narrative is desperately thin, and all of its tricky and sometimes cool puzzles can’t do much to redeem it.

Still, with these materials and in one place in the game you’re given some significant insight into a fictional world that might actually sustain life. You’re told the story of the Letarri, a culture of planet-hoppers constantly on the run from their former imperial overlords, the Rynan Collective. In a final attempt to free themselves of any threat of Rynan domination, the Letarri send a mission of highly qualified engineers and scientists to start a colony on a distant planet and prepare the colony for the rest of the population. When your character wakes up in the game, the mission has gone south, and all of your crewmates are gone.

You gradually gather some of the details concerning your more immediate circumstances by exploring the ship, sifting through emails and audio files ripped from cameras. About half of the time though, you’re just reading or listening to communications related to day-to-day operations, material that you can sometimes later use to help you advance through the game. Here and there you’ll pick up information that helps you make sense of the broader story arc, but again, most of what you can expect to get in game is disappointingly weak. With only one real exception (some keyword searching in “Data Archives”), you’ll have to head outside the game to find anything substantial.

In the end, Prominence isn’t so much a failure as it is a missed opportunity. With a narrative background about an oppressed people struggling to free themselves by pushing the limits of science and technology, the story is set up for success. But unfortunately, those possibilities are rarely explored in Prominence itself, making for a rather sterile narrative experience with sleek sci-fi surroundings.

//

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

December 7, 2015

Gone Home heads to consoles on January 12th with behind-the-scenes commentary

It’s fair to say that we’re quite fond of Gone Home. It was our Game of the Year when it came out for PC back in 2013. And its mark has been left not only on our own minds, but in those of other creators, with Gone Home‘s intimate exploration of household objects manifesting in various game narratives over the past two years. Of course, there’s more to it than that; the moment of genuine terror it manufactures, the homage to the 1990s and teen angst, its housing of one of gaming’s prominent queer relationships, exploring themes of aging and growing in-and-out of various passions.

we get a chance to find out what makes this game tick

That Gone Home will be able to reach more people from January 12th as it’s coming to PlayStation 4 and Xbox One then is, of course, great. But for those of us already familiar with that small house in Oregon this new platform launch is a chance to further indulge a fascination. Get this: The console versions of Gone Home will come with 90 minutes of behind-the-scenes commentary from the creators. Finally, we get a chance to find out what makes this game tick, perhaps both literally and figuratively.

Unfortunately, before that date, we don’t know exactly what the folks over at The Fullbright Company divulge in this commentary. It’s all speculation for now. But, we do at least have a special message from studio head Steve Gaynor, who speaks in the video below about bringing Gone Home the announcement.

The Fullbright Company is saying that this console version of Gone Home is a “PC-perfect” translation, meaning that it plays exactly the same as it did on PC, albeit tweaks to some of the controls to make them perfect for playing on a gamepad may be present. It may not, however, look exactly the same, as Gone Home has since seen an upgrade in its transition from Unity 4 to Unity 5. In other words, if there are any changes at all, it should look a little better.

You can find out more about Gone Home on its website. Of you could, you know, read our review.

Muay Thai by day, League of Legends by night: A conversation with Tanet “Jacky” Puangngoen

When he comes onstage in the second-to-last panel in Tribeca Games’ “The Craft and Creative of League of Legends,” Tanet “Jacky” Puangngoen is not an immediately imposing figure. He’s on the shorter side, with a kind face and polite demeanor. Nevertheless, when he throws a mock punch in demonstration at James Patterson, the esports host flinches pretty hard. It could have something to do with the clip we all just watched of Jacky kicking a training pad over sixty times in a minute. Or it could just be the general knowledge that Puangngoen spends most days training in Muay Thai, the art of beating another person into submission with your elbows.

But Jacky’s not just here because he’s a great fighter—he’s also an avid League of Legends player, having logged more than 3,000 games. This intersection of competitive passions is what Riot has brought him here for; they’re making a documentary about him, Live/Play Fight. I chatted with him afterward. (It’s an interesting conversation, but dense with Muay Thai and League references, so I’ve added explanations where necessary in italics.)

///

KS: What are some commonalities between playing League of Legends and boxing?

Jacky: It’s the goal. When you’re Darius (Jacky’s favorite champion in League of Legends, a brutal fighter best suited for one-on-one combat), it’s all about winning your lane. You don’t really need your jungler to gank (A League term meaning ambush, basically). Also in Muay Thai, your goal is always to win. To beat your opponent. And the way you practice is the same. Your goal isn’t just to land your ultimate—you have to know your weaknesses, you have to know your strengths. And also your opponent’s. Don’t let him connect with his skills—don’t let him land a low kick if he’s famous for doing low kicks, but his weakness is his punching. If you’re fighting against a brawler, (A Muay Thai fighter who relies on powerful punches at close range), for example, you don’t brawl with him. But if you’re fighting with a boxer, maybe you brawl more with him. It’s the same with League of Legends. You wouldn’t buy a pink ward if you were fighting against Teemo. Something like that.

You have to know your weaknesses, you have to know your strengths

KS: Do you think League of Legends is different because it’s a team game? Do you have a different relationship with it than Muay Thai, for that reason.

Jacky: Well, it’s only a team game when it’s late game. I’m not very good at teamwork. And my friends always complain about me, like, “Darius, you can’t carry (to win a game by yourself), this guy sucks in team fights, stop using him.” It was before the new Darius rework (Jacky’s referring to the changes Riot recently made to the character, to make him more useful in all stages of the game). I always had like ten kills, five kills in lane, but after the lane phase, I’m pretty much useless. So I don’t see it as a team game, really.

KS: How many games do you play in a week?

Jacky: It depends. Fifty? After my Muay Thai training.

KS: Does it ever get in the way of your training?

Jacky: No, it’s all scheduled. In the morning I train people, train myself. The afternoon, late night, that’s my time. That’s why I always have to argue with my girlfriend. Like, this is what I have to do. This is my time. This is my League of Legends time. There’s no girlfriend time, so, she has to live with it.

(It’s worth mentioning, here, that Jacky’s girlfriend has been standing about five feet behind him for the duration of this interview. During the panel, Jacky mentioned that they had almost broken up before traveling to New York, because of the amount of time he spent playing League of Legends. He laughed on stage, but it’s unclear whether or not he was joking.)

KS: How do you prepare for a boxing match?

Jacky: You have to lose weight. You have to lose a lot of weight. You have to be prepared, mentally. You have to know your opponent, you have to study your opponent, just like I said. You have to stay calm, make sure you do what you practiced in the ring. Train everything. The most difficult part would be the weight loss. Jogging, and jogging, and not eating, and jogging. Jogging and sauna. It was the most difficult part of preparing for the fight. The fight, that’s different. But preparing yourself to weigh-in—I dropped about twenty pounds, in total. You have to lose the last ten pounds in five, six days. I look very different. You’ll notice in the documentary, I have—(Jacky gestures to his cheeks, which are sucked in to look hollow.)

KS: In a fight, how in-your-head are you? Are you thinking more, are you more strategic, or is it reflex and natural response?

Jacky: For me, I’ve been fighting for quite some time, so you know what to do already. If you say, “I’ve played 3000 games of Darius,” I can tell you, I’ve landed more than a million punches and kicks in my life. I’ve been doing it for eleven years. So it’s not really something I have to think about, it’s just muscle memory. When he kicks, I block. When he drops his hands, I punch him. It comes naturally, in the ring. Even on the street, if somebody hits me, I’ve already lifted up my hands to block. It’s easy.

KS: Has that ever happened to you? Have you ever gotten into a fight outside the ring?

Jacky: No. It’s funny, I’ve been training for eleven years, but nobody ever wants to fight me.

I’ve landed more than a million punches and kicks in my life

KS: I guess that makes sense.

Jacky: No, no, no—it’s because I look like a geek! Nobody wants to beat up a geek. It wouldn’t mean anything! If you look so tough, like Mike Tyson, then everybody wants to fight you. But if you tell your friend, I beat up that geek, they’d be like “What the hell? Why are you bullying that kid? Poor guy!” If I’m tough-looking, people would want to beat me up, but even when I go out partying, nobody wants to fight me.

KS: League and fighting for you are both about that win, for you. That’s the ultimate goal, right? Winning at the end. Can you tell me about the last time you lost?

Jacky: You get so disappointed when you lose. When you fight, your goal is to win. You get injured, people hit you—when you win, it’s all worth it, all the hard work that you went through, the training, the weight loss, everything’s worth it when they lift your hand. But when you lose, it’s like the end of the world. It’s like—it’s hard to compare. The feeling, when you win, is even better than sex. It lasts forever. But when you lose, it’s also the same. It’s going to last forever. You will always remember it.

KS: League is your big thing right now, but what other games do you play?

Jacky: I’ve been gaming since I was young. The game that I suck the most at is fighting games. I can’t win, in Street Fighter. I’m too stupid. I’m like, “You’re not supposed to fight like this!” They always want to land their ultimate, it doesn’t make sense! I love driving games. Grand Theft Auto. And now, the mobile game is Clash of Clans. I have good friends who play it. Now, I won’t really play games that I can’t play with my friends, because I’m already alone in the gym, and in the boxing ring. So I want to find something that I don’t get from boxing. You know what I mean? I’m just looking for something that I don’t have.

///

Photo from “The Craft and Creative of League of Legends” by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tribeca Games

Photo of Muay Thai fighters from David Maiolo via Wikipedia Commons

ClusterTruck turns truck trailers into a chaotic highway

The world record for a jump by a semi truck is 166 feet, which is both too long to be jumping a truck and not very far at all once you start thinking about it. What if you’re into jumping and trucks and you want to go much, much farther.

Here, then, is ClusterTruck, which you should definitely not try saying three times in a row in the presence of small children. It is a driving game, though it’s not clear what you are driving. What is clear is that you’re driving on top of trucks, bounding from one to the next as they pass around obstacles and flip over. So ClusterTruck is a driving-ish game with jumping and trucks and what else could you possibly want?

The curious quirk of cross-the-road games—be it Frogger or Crossy Road—is that life is seldom better on the other side of the street. Sure, you want to get there, but only because the game is built around that premise. All the fun is on the road. ClusterTruck understand this; its objective is to stay on the road as long as possible. You’re are not at odds with the road or even perpendicular to it. You are prolonging your roadtrip, and why shouldn’t you? Your destination is surely mundane. There are no jumping trucks there. Pity.

ClusterTruck is scheduled for a 2016 release from Landfall Games.

In Buzzard, living is hell

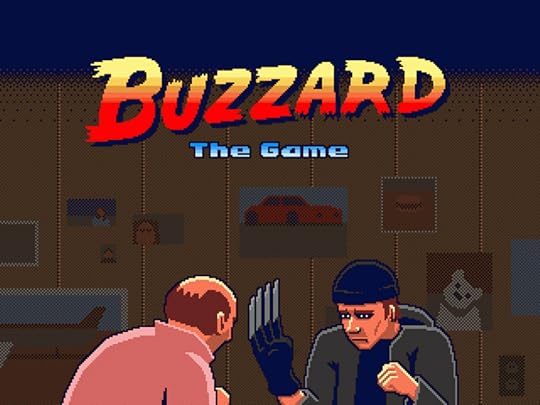

Buzzard, which was created in part by the forward-leaning design squad Babycastles, and recently launched at their gallery in New York, marks its own territory somewhere between a standalone game and a movie tie-in. Inspired by the recent film of the same name by Joel Potrykus, the game is less an adaptation of the film and more an illustration of it. Your enjoyment of this might depend on either your familiarity with the film or what you want from a game, but it is regardless a rare object: a handmade adaptation of an authentically independent film, where each title seems to illuminate the other.

Potrykus’s movie follows a not-quite-young man named Marty with a temp job at a nondescript bank in the midwest, who listens to metal, puts chips on frozen pizza, and seems to only have one (terrible) friend. He tries to release himself from this dead-end existence through petty crime, which ultimately leads him into a deeper dead end. The film is excellently made and beautifully evokes an atmosphere of aimless American living, mediated slightly by the comfort of lurking off to a suburban basement to play old videogames and chug Mountain Dew. Marty is the kind of person who goes to the movies alone wearing a rubber monster mask, who takes pride in fashioning a Freddy Krueger glove by attaching kitchen knives to a Powerglove—and, perhaps even more tellingly, Buzzard is the sort of film where tenderness, and pathos, is conveyed through one character offering to let another finish his level in a Genesis game. The true feel of microwave grease and Doritos dust is all over it.

Buzzard, the game, details that same atmosphere while approaching it from the inside. It uses an “8 bit” style, and mimics the frenetic pace of arcade-style games of the late-80s and early-90s—the same sort of games we see Marty frequently playing. While the film watches Marty and his acquaintances through the detachment afforded by a camera, the game feels like it is being projected outward from the world of the movie, as if it were a piece of the total environment which the entire Buzzard project articulates. The game, in its own way, brings us deeper into Marty’s emotional world than the film can; through its hyperactive, high-fructose aesthetic, it gives us a clearer window into his moods and habits, what it is really like to sweat it out on some dank sofa in west Michigan.

its hyperactive, high-fructose aesthetic

Buzzard gives the player a collection of mini-games which it cycles through at random. Each of these games are short—sometimes amazingly so—and are presented with minimal instructions. This modular structure, maybe a result of the several minds who created the game (at least four Babycastles-affiliated designers worked on Buzzard) mostly works in the title’s favor; your first playthroughs offer a constant flow of new experiences, which encourages the player to keep returning in order to see how many variations on the main theme there are. At the game’s launch, I watched many players repeatedly fail to get the hang of certain levels in time to beat them; yet, after losing all their lives, they would inevitably start over in order to try it again, to figure out the trick to whatever round had just flashed past them. The game encourages compulsion, much like Marty’s quest in the film to continue fighting the odds even the very enterprise of his life appears hopeless.

Though each level is pretty simple—always based around a core action that flies by as soon as it’s understood—the game is not necessarily “easy.” Buzzard is not really a game to be mastered, nor is it really about skill, or winning; it’s about being in the world of Buzzard. The game completes the image of scuzzy DiGiorno malaise so perfectly, but so differently from the film, that it strongly, if maybe accidentally, underscores part of what makes cinema and software such different art forms.

Though punctuated by moments of rage and violence, Buzzard, as a film, mostly moves at a patient pace, allowing its incidents breathing room and time for a base level of tension to develop. As a game, on the other hand, it moves so fast that it at times feels like it is pranking the film; some of the charm of the game is that it can feel like a parody of “videogames” in general and Buzzard, the movie, in particular. One level cleverly references an early scene in the film which consists of a long, unbroken close-up of Marty as he waits for a bank attendant to re-enter the room. In the context of the film, this shot provides us with a feeling of intimacy, and a creative statement about where the film is going to go, how it will work narratively, what we can expect to be shown, or not shown. In the game’s language, the complementary scene instructs you to “Wait”; the level is “won” by doing nothing, and letting time pass before the other character re-appears on screen to deliver dialogue.

Though narratively these two scenes are almost identical, the function across the two mediums is different. While both films and games are time-based forms, films are more inherently passive; we expect things to happen that we have no control over, and when something takes a while to unfold, it is more easily absorbed in the commonly agreed-upon language of cinema. In games, there is still an expectation that we have control, that progress happens because of our choices as players. Though a brief moment, the adaptation of this scene from film to game clarifies a profound difference between these two mediums, and what sorts of ideas can be simply adapted from one to the other.

It can feel like a parody of “videogames” in general

Levels like this one play with both the structure of the source material and what we expect a videogame to be. In a different level, the player controls Marty in a straight line across an Office Max parking lot to kick over a box full of office supplies. While this level’s prime motivation is to directly reference a moment from the film, as a play experience it becomes something like a distillation of what game mechanics even mean; you are presented with a linear task, there is one way to do it, and then you do it. It is nearly impossible to lose this level (though I did see this happen to a of couple players who missed the on-screen instructions).

Other levels are more “gamey”: a scene from the film in which Marty feeds Bugles to his friend Derek on a treadmill makes a seamless transition to the game. In another, you have to accurately aim a squirt of ranch dressing onto a frozen pizza. In yet another, you sharpen the knives on your Krueger glove by following a directional pattern laid out on screen (for whatever reason, this level gave me the most trouble). The tension between traditional arcade-style action and more conceptual moments gives Buzzard a tone somewhere between sincere tribute and provocation—which, as an adaptation of the film itself, is not too far off-track.

In evoking the “stuff” of the film, Buzzard, the game becomes a series of discrete moments which catalog and clarify a separate creative work. Sort of an homage to the bitter, yet heartfelt spirit of the film, as well as an entire era of action-based gameplay, Buzzard references nostalgia while frustrating it. It feels like a retro throwback, but unlike, for example, Shovel Knight, it doesn’t play by the rules of what has come before; it manipulates the feeling of classic games to summon a sort of comfort and familiarity, which the actual experience of the game dismantles. It is not a game to make you fondly remember your childhood. Like the film it sits alongside, Buzzard is more interested in looking at how life, as it drifts into adulthood, is disappointing, and how the pleasures which relieve that disappointment are so often brief, random, and infrequent.

Gone Home programmer announces a gorgeous game about manifest destiny

“One describes a tale best by telling the tale. You see? The way one describes a story, to oneself or to the world, is by telling the story. It is a balancing act and it is a dream. The more accurate the map, the more it resembles the territory. The most accurate map possible would be the territory, and thus would be perfectly accurate and perfectly useless.

The tale is the map that is the territory.

You must remember this.”

– Neil Gaiman, American Gods

American roads tell stories. From Huck Finn’s trek across socioeconomic boundaries to Kerouac’s rhythmic ode to a dying movement, American roads invite a uniquely existential wandering that could (and has and will) fill endless amounts of books, movies, and songs. Because buried beneath the surface of any American road are the layers upon layers of settlements and stories passed. Built on a foundation of reinvention, the American landscape welcomes the maverick, swallows him whole, and leaves only enough bones behind to entice the next unsuspecting traveler. The American identity is one of perpetual searching, discovery, and erasure—a journey home, where “home'” is a concept both unattainable and untamable.

“home'” is a concept both unattainable and untamable

As Wednesday from Neil Gaiman’s American Gods puts it, America is “the only country in the world that worries about what it is.” Because while “no one ever needs to go searching for the heart of Norway,” the search for the heart of America has led to things like jazz and folk music, as well as some of the greatest novels of the past century. Captivating the greatest and most creative minds from around the globe, American existentialism isn’t the story of a country. It’s the story of a world colliding with itself: the image of a snake eating its own tail.

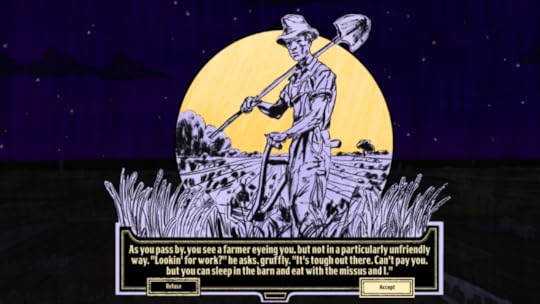

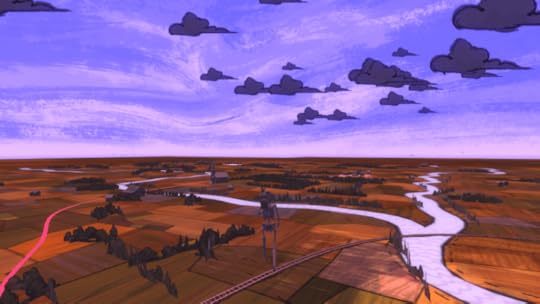

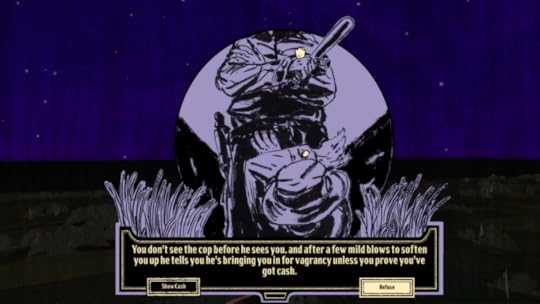

Johnnemann Nordhagen (who was the programmer of Gone Home) recently announced that his latest project will explore manifest destiny in all its many shapes, colors, and cadences. The first title from Dim Bulb Games, Where the Water Tastes Like Wine will combine 2D visuals with a 3D map of the US that allows players to experience the multiplicity of identities that helped define the country.

As Nordhagen explains to Eurogamer, “American folk culture is one of collaboration, [that’s about] sharing songs and stories but giving them your personal twist. [American folk] comes from many different cultures—the European settlers, the slaves that were forced to live here, the workers who have traveled here in search of opportunity, and of course the people actually native to this land.”

While “most of the romantic road stories out there are [about] white males traveling and having adventures,” Nordhagen tells Polygon, many of the country’s most influential travelers never had the freedom to tell their own stories. Spanning from cost to cost and over the course of an entire century, Where the Water Tastes Like Wine aims to tell “the stories of people who have been pushed to the fringes.”

American folk culture is one of collaboration

“[In a lot] of cases people are on the road not out of choice but out of necessity,”Nordhagen says. “They are being crushed by the rolling wheel of American society and they are doing their best to get out of the way.” From the spread of African Americans across the south, to the movement of migratory workers, and the forced marches of native Americans, the game hopes to capture the essence of the songs, poems, and stories that emerged from the most treacherous journeys in US history.

As evidenced by the teaser trailer, Where the Water Tastes Like Wine will incorporate elements of the surreal and fantastical. Nordhagen tells IGN that “every once in a while we see through the cracks in the world and get a peek at other realities. It’s recognizably America, though—poker and trains, the Southwestern desert mesas, and something that suggests the colorful and idyllic farm produce labels of the beginning of the 20th century.”

Though not much is known about the exact details of Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, the concept art promises a world of fantastic realism where magic emerges from the richness of storytelling itself.

Where the Water Tastes Like Wine is set to release in 2016. You can keep up to date with the game by visiting its website.

A series of inputs and outputs

Colossal Cave Adventure (or, Adventure for short) isn’t exactly a familiar title today. Developed during the early 1970s, Adventure was written by programmer Will Crowther while working for Bolt, Beranek and Newman. Crowther was an advent cave explorer, and had vast experience surveying the Kentucky caves. So, combining his love for caverning with his passion for fantasy role-playing, Crowther wrote a short interactive story about exploring a fantastical cave for his daughters. With the help of programmer Don Woods, the game quickly spread across the fledgling internet, and became an instant phenomenon. By the late 1970s, Adventure had ushered in a brand new videogame genre: adventure games.

Up until the mid-1980s, adventure games were predominantly based around interactive fiction. But when Roberta and Ken Williams stumbled across Adventure in the late 1970s, they decided to take their own shot at the genre. By 1982, Sierra On-Line was born, and, unlike the original Adventure, Sierra’s adventure games featured color pictures for the player to look at while solving interactive puzzles. The graphical adventure game was born, and, by the end of 1984, Sierra solidified the genre with King’s Quest, an epic Medieval journey which cast the player in the role of the daring knight Sir Grahame. For the first time, players moved through the world using their keyboard’s arrow keys, and typing in text commands—such as “open the door” or “talk to the king”—to learn more about the Kingdom of Daventry. King’s Quest’s interactive world was a major hit on the Tandy 1000, and Sierra soon capitalized on the game’s success with games like Space Quest, Police Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry.

Since then, graphical adventure games have become a classic genre in videogaming. Today’s players may fondly remember their first time playing through Tim Schafer’s Day of the Tentacle, Robyn and Rand Miller’s Myst, LucasArts’s Grim Fandango, and Sierra On-Line’s horror classic Phantasmagoria. Granted, adventure games aren’t exactly a relic of the past, either. In recent years, there’s been an enormous resurgence in popularity for the classics of the 1980s and ‘90s, thanks in part to Telltale Games’ success and Strong Bad’s Cool Game for Attractive People, up through more recent efforts like Dropsy and Life is Strange. Over 40 years after its debut, adventure games continue to interest players new and old alike.

graphical adventure games have become a classic genre in videogaming

Playing a graphical adventure game is, for the most part, a fairly standardized experience. Players use the arrow keys to walk around the world, and interact with people and objects through a point-and-click interface. Sometimes players have to hold onto items in order to solve puzzles, or ask for help from important characters. Either way, most adventure games are built around resolving conflicts and unlocking more of the story. The experience is relatively laid-back, and most graphical adventure games rarely deviate from the point-and-click interface.

But alternative games developers love to play around with our traditional expectations of games, and developer Arielle “SlimeKat” Grimes is no exception. As an altgames developer, most of Grimes’s work uses gaming as a sort of confessional interaction with the player. She pours herself into her games’ development, and builds her work around her experiences and feelings.

When I reached out to Grimes earlier this year, she emphasized how games let her communicate concepts to the player in a way that other mediums simply do not allow.

“I believe that the ‘engagement loop’ of players interfacing with a game, the series of inputs and outputs, can create a better understanding of ideas and concepts,” she told me. “It’s through the engagement that a player gets to connect with the content of a game—and when that content is emotional, [it] allows them to engage with what may be foreign to them.”

These ideas can be seen in practice in her expressionist videogame, What Now?. Described by Grimes as an “adventure in sensory overload and emotional breakdown,” players take on the role of an unnamed female protagonist, interacting with different objects found throughout her room, such as a bed, a computer desk, a bookshelf, and a mirror. Each of these items trigger a different journal entry about the player character’s thoughts and feelings while looking at the object.

However, Grimes isn’t very interested in the physical appearance of these objects. Unlike Adventure or King’s Quest, each piece of furniture has a deeply introspective meaning to the player character. She reflects on the conflicting emotions found inside her head, and each item builds a picture of her inner emptiness and despair.

Sounds simple enough, but Grimes adds a twist. If the player moves too quickly through the world, small blue and green pixels begin to cover the player character’s body. If the player keeps on moving, her character will become engulfed in an array of colors—first starting with the player character, then spreading throughout the room, until the entire world corrupts into a pixelated mess. The game begins to shut down, as the user interface fades into the player character, blocking out the bedroom world.

“You left me to rot IT NEVER ENDS WHY IS THIS,” the protagonist writes in her journal. Words flash in front of the player. “Screaming won’t make it stop,” she says. “It keeps happening.” And then the game fades, and restarts at the title screen.

“Screaming won’t make it stop”

“This game, it came from an emptiness in my life,” Grimes told me. “I wanted to convey to the player exactly where I was in my life at that point. Living in a space that is newly wholly your own space, dealing with the newfound emptiness, and the reminders of what was, everywhere around you.

According to Grimes, she began with the idea of “standing still,” and refusing to address emotional pain or anxiety. “We all know this isn’t healthy, or productive,” she explained, “and that we have to accomplish things—and even as we try we may still break down.”

Most players take movement for granted in adventure games. We assume that walking up, down, left, or right is always a safe choice. But Grimes breaks the rules in What Now?, and asks the player not to take freedom of movement as a given right. Instead, moving forward is dangerous. It overwhelms the player character and shuts down the game. So if the player wants to learn more about her character’s feelings, then they need to walk slowly, and in short steps. They need to play by Grimes’s rules. Otherwise, the world will start shaking back and forth, as the game fades away into the player character.

In the original version of What Now?, there was no end state to the game. Rather, if players moved too fast, the barrage of pixels mess would appear on screen and envelope the player character, but the game itself would never restart. However, when Grimes updated What Now? in 2015, she made the glitch mechanic a much more sudden experience. Instead, if the player moves too far while their character is glitching, the game will begin to shut down. Grimes refers to this as an “endpoint” that activates a “game loop.”

“I was preparing the game for its first proper public showing, and therefore needed an experience that could come to a defined end, and loop over so that I could generally not have to worry about the game needing to be reset,” she explained. “The original release was very ambiguous in its ‘meaning,’ and what the player was to take from it, after the experience is complete.”

But meaning is much more clear in the latest rendition of What Now? Seeing Grimes’s player character lament her loneliness as her room shakes uncontrollably is uncomfortable, to say the least. It replicates feeling overwhelmed quite well.

Granted, Arielle Grimes saw most of What Now?’s development as a deeply personal look at her own experiences with anxiety, rumination, and regret. But when she took the updated version of What Now? to Bit Bazar #5 in Toronto, she was amazed by her players’ responses.

“I was surprised to see kids drawn to my work, and to see even the antsiest of kids work through the whole demo,” she said. “By far the most stand-out reception was somebody who ended their playthrough smiling and crying. They thanked me, but were unable to talk to me directly about the experience. They were very overwhelmed.”

Colossal Cave Adventure and What Now? come from two radically different backgrounds. The former is an interactive journey through a Kentucky cave, developed by a computer programmer in the 1970s; the latter, a highly personal and introspective look at a young woman’s struggles with loneliness and anxiety. At first glance, it’s difficult to classify both titles as “adventure games.” Both works are dealing with different issues, and draw in different kinds of players.

Both games are about exploration and understanding

But there’s something important that both games share in common—they tell a story. They share an adventure with the player. Whether it’s a journey through a fantasy cave, or a voyage through a young woman’s mind, both games are about exploration and understanding. We learn and grow from the game world, even amidst the challenges we are presented.

When Arielle Grimes sat down to develop What Now?, she certainly wasn’t thinking of the evolution of adventure gaming. It’s hard to say King’s Quest was directly on her mind. But, in some ways, she ended up contributing to the genre’s growth. She challenged our understanding of what it means to play an adventure game. And in 2015, thinking differently about what it means to develop a videogame is more important than ever—even if alternative games make us feel a little uncomfortable in the process.

///

SlimeKat is an independent developer, 2D artist, and audio designer. Her work can be found on her official website, and she can be found on Twitter as @slimekat.

//

Photo of Colossal Cave Adventure by autopilot via Wikipedia Commons

December 4, 2015

The Ballet game Bound is already sashaying into our hearts

There is a certain ballet to game design. Perhaps not in the visual sense, but in the dedication—the blood, sweat, and tears it takes to pull off even a simple movement. Like a game designer, a ballerina must work night and day, while knowing every aspect of what goes into the beauty of her art, both inside and out. From the high level concepts to the granular, from the emotion of the piece to the soles of the shoes that help her execute it.

A ballerina must make a world erupt from the rigid structure of her body, creating by pushing the natural limitations of her canvas. Just look at this video of ballerinas preparing their pointe shoes and explaining the rigorous, tedious, and repetitive process—like programming for a game designer, the ballerina could ask a third party to deal with breaking in her pointe shoes. But then she would lose something in the process; that ultimate control over the container that shapes her artwork.

Ballet and game design share a natural passion with each other. And the Polish team of game makers called Plastic Studios will explore this common dialogue of passion as they set out to make Bound. As with the studios past titles (Linger In Shadows and Datura), Bound will be an experimental “notgame” game, but this time about a ballerina. Teaming up with Sony Santa Monica, Plastic Studios hopes to deliver an experience that not only captures the beauty of a performance, but also the rigors of a collaborative piece. With the tagline “sometimes to move forward you have to step back,” Bound will leverage the challenge of one big puzzle against a community of players working together.

In the announcement, director Michał “bonzaj” Staniszewski describes the Modern Art flavor of the game as ranging from “Suprematism, Concretism, Neoplasticism, or what Bauhaus has delivered.” Aside from the captivating art style, players can look forward to the ballerina protagonist played by Maria Udod and choreographed by Michał Adam Góra, who Staniszewski describes as having a “rich personality.”

There is a certain ballet to game design

The richness of her style is evident in both the trailer and the teaser website. Beginning with a focus on the classic pointe shoes, the trailer eventually broadens out to reveal the bird-like shape of the dancer and then the wide, expansive world she unveils with a sweep of her out stretched arms. If watched on the teaser site, the trailer is played over an animated backdrop of the ballerina, her motions mimicking the inward and outward focus of the video.

The music will be a blend of a classic ballet score and electroacoustic stylings as performed by Oleg “Heinali” Shpudeiko. On top of all that, the low poly art pulls it all back together to the quiet yet striking minimalism of its visual stylings.

You can check out the trailer and website for yourself here.

Euclidean Lands looks like the next great mobile puzzler

It’s nice to see how much care recent mobile games, like Monument Valley, Lara Croft GO, and Hitman GO before it, have put into building a distinct art style beyond the boring visual polish seen in the free-to-play market. A new game called Euclidean Lands seems to combine the best from the aforementioned titles: a bright and colorful world that’s part board game, part abstract, toy-like puzzler that spins and rotates like the Escher-esque worlds of Monument Valley.

We first got a look at Euclidean Lands last month, when it was only a . Now it has a trailer, showing off more of its puzzles, each like a miniature medieval Rubik’s Cube. Based on its YouTube description, Euclidean Lands is set across six planes (the different surfaces of a 3D cube, presumably) that can only be manipulated by a selected few.

Your character is one of the chosen ones, but it’s not that simple. Head over to the Twitter for Euclidean Lands and you’ll find a few new gifs pulled from the trailer with some accompanying explanations. In one, the creators show off how a boss fight set on a floating cube can get complicated when the boss has the power to rotate the cube’s sides, too.

Learn more about Euclidean Lands on its Facebook and Twitter.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers