Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 189

November 30, 2015

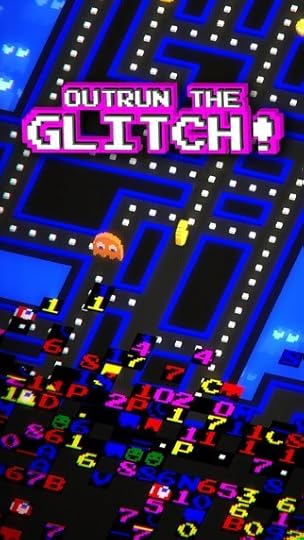

How a Small Team of Australian Game-Makers Reinvented Pac-Man

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

//

This past August, the latest version of Pac-Man reached #1 on the charts in Japan. This may not sound surprising. Until one considers that Pac-Man 256 is a touch-based mobile game made by a small independent studio from Melbourne, Australia.

When Matt Hall and Andy Sum of Hipster Whale released their Frogger-inspired mobile game Crossy Road last November, their expectations were realistic.

“We definitely didn’t expect any of this to happen,” Sum told me over the phone. “When we made Crossy Road, we knew we had a good game and we thought it was a lot of fun, but it just really took off more than we thought.”

What happened resembles the unrealistic plot of a power-fantasy young adult novel: their little game became a phenomenon. By mid-August 2015, Crossy Road was downloaded over 100 million times across all platforms. In the span of a calendar year, a small team from Australia became one of the most sought-after mobile developers in the world.

“We heard from a lot of companies,” Sum says. “Bandai Namco’s [pitch] was one of the strongest.” Soon after Crossy Road’s launch, the team opened an email from one of the oldest game developers in the industry. The idea? Make the next Pac-Man game for mobile.

Hipster Whale (with help from fellow Melbourne-based developers 3 Sprockets) mocked up a prototype to show Bandai Namco at the Game Developers Conference (GDC) in March of this year. They loved it. The next five months saw Sum and Matt Hall continue to tweak and polish the design, while 3 Sprockets handled the programming and Bandai Namco Vancouver headed up the Marketing and Publishing duties. Pac-Man 256 came out on August 19, quickly peaking to #1 in Japan.

The mobile game takes a glitch from the original arcade game and makes it sentient. Due to hardware limitations, players could only get to Level 255. Reaching Level 256 would cause the screen to fill with random numbers and colors, the code turning in on itself; colloquially, this is known as a “kill screen.”

In Pac-Man 256, the glitch is now a dark wave of broken code that slowly takes over the maze. The player controls the titular yellow circle with swipes in four cardinal directions, just as she moved the joystick in 1980. But here the maze is endless; ghosts are smarter, and a special mode that costs credits adds powerful weapons like lasers, bombs, and tornadoes. Munching dots in succession adds to the player’s score; power-pellets still turn ghosts an edible blue. But the glitch is always flowing upward, chasing the player through an infinite, randomly-generated labyrinth.

Sum is twenty-five and doesn’t have much of a history with Pac-Man, but Hall, his co-developer’s elder by a decade, fondly remembers playing the Namco original in the arcades.

“Because it’s Pac-Man, the audience is quite different [than Crossy Road],” Sum says. “It’s more of a hardcore audience or an audience that remembers Pac-Manfrom awhile ago. But we also wanted to make it accessible.”

Though access isn’t an issue for players, the creators have found it to be one of the biggest obstacles for developers in Melbourne. Though Sum and Hall live two hours away from each other, they often work remotely; when Sum and I spoke, he was in San Francisco. But collaborating or exchanging ideas with others is more challenging.

“As an Australian developer, one of the most difficult things is being physically far away from the rest of the world,” Sum says. “For GDC, Gamescom, E3, any of the big events, we have to fly literally to the other side of the world to meet up with everyone. It’s expensive and a very long flight.”

In the past, that distance has also turned out to be a strength. Crossy Road shipped with eleven different languages supported. New updates bring playable characters based on specific holidays or customs from various countries; a Korean update brought kimchi, the spicy vegetable, and Jindo, a hunting dog from an island off South Korea, whereas a U.K.-centric update included a Telephone Box and the Loch Ness Monster.

Pac-Man 256 won’t have the same expanded roster due to its more well-known heritage. But the character’s global popularity helps the game remain accessible across all borders, something Hipster Whale and other Australian citizens know is important.

“If you’re in Japan, you’re probably just going to make a game focused on Japanese gamers, because they have a very different games culture than the US,” Sum says. “If you’re in America [with its] 500 million people, how much does Australia and its 24 million people really count?”

“Since we’re so far away from everyone, we do think about how big the world is.”

Radio the Universe is still far away, but here’s some new art

Remember Radio the Universe? It started popping up around the web in 2012, ran a successful Kickstarter at the end of that year, and has been surfacing here and there for the last three years with bits of art and minor updates.

It was among the first wave of smaller games that seemed invested in taking pixel art in a new direction—still rooted in the isometric simplicity of retro-style games, but with a ton of detail and fluidity in the environment and character movement. Think Hyper Light Drifter.

For Radio the Universe in particular, it was the elegant pixel art, gorgeous color palette, and strange, stony sci-fi realms that drew me into the project at first glance, even before Hyper Light Drifter captured everyone’s attention. I never forgot about you, Radio the Universe.

In a rare Kickstarter update, the creator of Radio the Universe (known as 6e6e6e) has posted some new before and after art, showing off the way the game has changed graphically. It’s clear how much care has gone into every digital brushstroke.

In one image, a train transforms from a bulky hunk of smooth green metal to an intricately crafted locomotive granted shape by its sharp grooves and indentations. In another image, a rigid electrical device of some kind becomes a layered and bustling collection of parts.

“There’s more technically grounded detailing in the general design of the game,” explains 6e6e6e.

According to the update, most of the development time for Radio the Universe has gone into these graphical reworks and designing “later sets of areas” that include more moving parts.

“There’s a lot left,” says 6e6e6e. “Thanks for being patient people.”

See more Radio the Universe on its Kickstarter.

Eternal Darkness, Psychonauts, and sanity in videogames

Western depictions of mental illness often tend toward the dramatic. Shows like House often showcase rare disorders or extreme versions of a diagnosis when they mention mental illness at all: the schizophrenic woman who sees fire where there isn’t any, a mute patient who is able to speak after one redeeming event, or the man who had bipolar disorder and kept it secret after opting for an experimental surgery—one that ultimately resulted in malaria. In other cases, the idea of insanity is used as, if not a comedic device, a warning; one simply cannot look into the face of an Eldritch abomination or other horror without losing part of oneself, and many a psychological thriller’s plot revolves around an obsessive lunatic. Mental illness in fiction is often used as a way to strip individuals of their humanity and, in doing so, reflects a cultural fear of what happens when we, too, descend.

The videogame Eternal Darkness, released in 2002, centralizes this tension. Billed as a “psychological horror action-adventure,” the game’s most notable feature is a sanity meter that glows green on the left-hand side of the screen and depletes whenever the protagonist comes face to face with a monster. Once the meter dips low enough, in-game and fourth-wall-breaking (in)sanity effects begin to take over—the screen tilts, save games “disappear,” the protagonist has auditory or visual hallucinations, and the player’s television appears to mute or go to a blue screen.

used as a way to strip individuals of their humanity

While the game may not explicitly categorize the sliding scale of sanity as mentally stable versus mentally ill, the mechanic and effects are consistent with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some studies suggest that up to 40% of combat veterans with PTSD experience psychotic symptoms, and the probability increases the more burdened by PTSD they are. In Eternal Darkness, the godlike character Xel’lotath, whose domain is sanity, is herself depicted as “insane” via a Hollywood-esque version of dissociative identity disorder in which she appears to have multiple versions of herself that are aware of each other and converse.

The horror of Eternal Darkness therefore lies not in the monsters your character must fight, but in the long-term impact of encountering those monsters. As you navigate the game’s settings and your sanity depletes, it attempts to make its point by extending that impact into the player’s technology, wrapping us tightly in the fear caused by the idea that we can no longer trust our own perceptions of the external world. Meanwhile, the icon of insanity is Xel’lotath; sure, she’s powerful, but she’s also an alien, and not exactly someone the player wants to compare themselves to, despite that the inevitably decreasing sanity meter will force those questions. The game firmly aligns itself with the “badness” of mental illness and the value of holding on to your sense of reality in the face of terror.

This one-dimensional approach to mental illness—or, in some senses, simple departure from the “norm” that is often considered sanity—is a persistent theme in media contexts. The 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, where the titled characters are famously two distinct personalities in one body, is often associated with dissociative identity disorder, and casts Dr. Jekyll’s alter-ego as an evil murderer. The late 19th-century short story The Yellow Wallpaper and Sylvia Plath’s 1963 semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar both comment on the challenges of mental health for women trapped within the context of a patriarchal society, and, in the case of the former, it’s evidenced by the protagonist descending into madness.

In more modern contexts, the tabletop game Arkham Horror dissuades players from taking hits to sanity by sending them to the asylum whenever their meter hits zero. The online game Fallen London institutes a reverse sanity meter—nightmares—which, as it gets higher via otherwise profitable actions, may allow you to understand more terrible things beyond a certain level, but is also a fate widely recognized as not being worth this eventual payout, as you will hit a point where you must wait to return to being functional enough to interact with the game’s world. Finally, Amnesia: The Dark Descent is not unlike Eternal Darkness, in that once your sanity meter falls too low, you are pursued by monsters. While some examples, particularly Lovecraftian media, may assert one is incapable of reaching the same levels of understanding while remaining sane, it is rarely, if ever, regarded as a price one ought to pay, and it’s considered “bad” to lose one’s sanity at all.

departure from the “norm” that is often considered sanity

And then there’s Psychonauts. Originally released in 2001, Psychonauts is more overtly a game about the mind, mental illness, and other emotional problems. While Eternal Darkness explores the descent into madness and casts insanity as something to be avoided at all costs, Psychonauts takes a more comprehensive view. The protagonist, Raz, runs away from the circus to attend a summer camp for children with psychic abilities. While there, he hopes to hone his abilities such that he can become a “Psychonaut,” and his training largely involves him entering other people’s minds to help them with their mental issues. In some cases the “deeper issues” lie in a past traumatic event or a rough childhood but sectioned off, while in others the entire mental landscape is distorted to represent insanity. In all cases, there are memory vaults, “mental baggage” that takes the form of luggage, and other indications that no one in the game is completely mentally healthy.

At the same time, the game does not equate “mentally healthy” with being neurotypical in a direct fashion, nor does it tie competency to lack of mental illness or past trauma. Not only does pretty much every camper training to become a Psychonaut have traits that code for a mental illness—two happy campers are plotting suicide in attempt to gain more powers, a boy wears a tinfoil hat to avoid making things explode, and another child has extreme hydrophobia—but so do some of the camp instructors. Even characters that don’t have obvious coding, such as Raz, are shown to be wrestling with a deeper issue of one kind or another. For Raz to “fix” an issue obviously associated with a mental illness or help to resolve feelings over a past trauma, the person must be afflicted by it on some level; he does not assume particular eccentricities are a problem in the absence of related distress.

If Eternal Darkness is a game that speaks to “normal” people’s fear of going insane, Psychonauts is one that delves deeper into what being mentally healthy actually means. Eternal Darkness assumes it is impossible to see terrible things without going mad; Psychonauts largely assumes you’ve gone through something terrible, but recognizes the impact of that on your psyche is dependent on how you handle it and how your mental landscape looks otherwise. While it’s possible to restore sanity in Eternal Darkness via a particular finishing move, that it takes a one-dimensional view on it and implies a lack of sanity is less desirable has powerful and negative implications for mentally ill people outside of the game—in essence, it says that the deviation from the normal is itself the problem, and fixing it requires one to return to it. Psychonauts, though arguably poking fun at particular mental illnesses, takes a more positive approach: it says everyone’s mind is its own world, and “getting better” means handling our issues in the ways that make the most sense for us while embracing the rest of our eccentricities.

November 25, 2015

Kentucky Route Zero: Act IV is almost upon us

It’s been a slow ride since Cardboard Computer’s moody tale of dark roads and mysterious strangers first debuted in early 2013, but we’re getting steadily closer to the end.

Kentucky Route Zero: Act IV is nearing completion and while it has no exact release date yet, its developers have stated on Twitter that they are “excited to share it soon,” offering up a new piece of artwork in the interim.

While only one piece of the larger, dreamy puzzle that is Kentucky Route Zero, its third act prevailed as our game of the year in 2014 for its quiet beauty and sincerity. The game follows a delivery truck driver named Conway as he journeys through rural America, meeting other troubled souls along the way.

KRZ is all about small things

The gap between each episode has widened more and more since its debut—a couple months at first, then a full year, then a year and more, but a series of short experiences and other experimental interludes have filled the spaces inbetween.

Kentucky Route Zero is all about small things, so to receive its tale in fragments feels like part of the experience. But for those waiting to take it all in as a whole, it’s exciting to see Kentucky Route Zero trucking along towards its conclusion.

Find out more about Kentucky Route Zero on Twitter and its website.

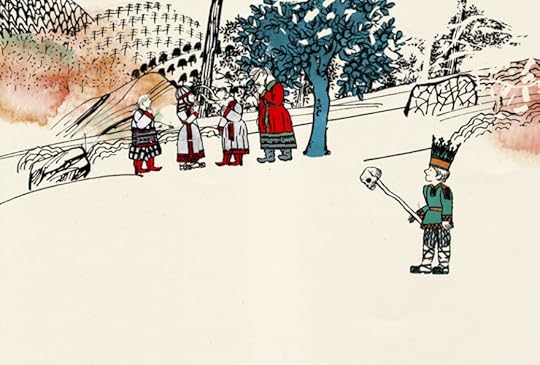

Turning Narrative Into A Play Space With Forest Of Sleep

Proteus creator Ed Key and artist Nicolai Troshinsky of Twisted Tree Games have only talked abstractly about their upcoming experimental narrative game Forest of Sleep before. But now, a few months after its initial announcement, the pair have cut into the specifics of what they mean when citing “emergent associations” and “cinematic language.” Speaking to Gamasutra, Key revealed the process behind his effort to use procedural generation to create stories that had both drama and pacing, using only hand-made art pieces and wordless animated scenes.

Crucial to this aim is the choice of influence found in late-20th century Eastern European illustration and animation and its “absurd fairytale logic.” It’s this that Key says has informed Forest of Sleep‘s visual language while pointing specifically to the artistry in Russian animator Yuri Norstein’s short Fox and Rabbit. In particular, Key draws attention to the “sense of framing and cutting between images and the position of characters.” Without words to say more, the viewer—or in this case, the player—naturally pays closer to attention to these kinds of details in a scene, meaning it’s their imagination that weaves the narrative threads together.

But it’s not enough to rely on players to tie together randomized plot points and visual structures. Key talks of striking a careful balance. As such, Forest of Sleep won’t only provide a series of folkloric tableaus but also build in a sense of action and response. This means that certain characters and objects that are generated will be marked for re-appearance later in the tale. This detail might seem trifle but it turns out that our human brains can’t resist creating inferences from this kind of material. In any case, it’s in these object-based callbacks that the stories of Forest of Sleep supposedly find rhythm.

“Even if something happens and it’s gone forever, if you mention it later on you reinforce that the game knows that it happened to the player,” Key told Gamasutra. “Once [the engine] has linked two entities together in its database, those should continue to be associated in some way, at least more than once. If you haven’t seen them for a long time, it should visually or musically recall them to reinforce that association.”

a scientific understanding of narrative.

The trick, then, is to have the player believe that the story they’re piecing together has been intended by an author, rather than produced with a piece of code. In order to achieve this, Key has had to deconstruct formulaic narratives and discover each of the common components so that he can feed them to his code to inform its replication. The result of this pursuit has led to what can only be described as a scientific understanding of narrative. Key reeled it out:

“The individual parts are kind of crafted templates that can take entities that have certain prerequisites. Such as having an item you don’t own, or someone you haven’t met before. The idea is that [the engine] has a lot of those to choose from, and the story system is working along this timeline, and as it moves towards an apex or twist, that becomes more flexible as the player might do something to stretch it out.”

The challenge for Key here is masking his method as is often the case with procedurally generated works. The nature of these projects means that repetition and accidents are easy to come by and immediately expose the skeleton carrying the whole thing. The team behind No Man’s Sky has overcome this by having hundreds of tiny drones that record videos of its many planets for the team to check over. It’s a compromise between total randomness and an effort to have order. It seems that Ed Key is going for something similar with Forest of Sleep except the subject isn’t a universe but short stories and implied plot structure. As Key concludes: “It’s a narrative playspace, rather than a linear narrative that the player goes through.”

You can find out more about Forest of Sleep on its website.

h/t Gamasutra

Lonely dwarf planet Pluto finally finds love as Noby Noby Girl arrives

It’s been a rough ride for Pluto ever since it was demoted in 2006 by the no-good scientists who deemed it unworthy of the proper “planet” classification. It lost its confidence, became altogether uninterested in life, and has been revolving in its own sorrow ever since. After the demotion, all of Pluto’s accomplishments were diminished by the “dwarf” planet prefix. No matter what it did—whether completing an orbit around the sun or being visited by a spacecraft—big brother Neptune and his ilk would always outshine him (you know, since they’re closer to the sun).

Fear no more the heat of the sun, Pluto

But fear no more the heat of the sun, Pluto, for you need not suffer through life alone anymore. Noby Noby Boy, the delightful little sandbox game by Katamari Damacy creator Keita Takahashi released back in 2o09, is about exploring planets and stretching across the solar system. Here’s how it works: players control a worm-like character known as Noby Noby Boy, raking up points based on how far they can stretch his body while exploring the environment. Every player’s score is then added up and transferred over to Noby Noby Girl, as she makes her solitary journey to the end of the solar system and back.

From last we heard back on March 6, 2014, Noby Noby Girl had finally reached the blue beauty Neptune. Yesterday, six years after the game’s initial release, she arrived at the very edge of our solar system. As evidenced by the video capturing the momentous occasion, Pluto looked frankly shocked to be receiving such a guest at this hour. Mouth agape, he couldn’t believe his luck. A friend! Not just any friend—a girl! Pluto readied himself to graciously receive Noby Noby Girl, but he was in the middle of revolving, and wound up embarrassingly turning his back on her (a faux pas in planetary social circles). But Noby Noby Girl was super chill about it, wrapping her wormy, heart-patterned tendrils around him in the cross-planetary embrace Pluto he had waited all his life for.

Reaching Pluto means that the planet finally opens up as a playable environment for players. Now, Pluto will be able to keep himself entertained for the years to come. Yet his moment in the sun with his love, Noby Noby Girl—who brought all this good fortune upon him—was sadly brief. It seems like almost as soon as she arrived, she already had one foot out of the door, turning back to make way for the sun again.

Heartbroken, Pluto will remember his momentary flirtation with Noby Noby Girl for the rest of his dwarf planet existence. And I guess, like the rest of us, he’ll have to wait quite a few more years before finally reconnecting with his stretching beauty again.

The Tower Inverted still looks longingly to the sky

The Tower Inverted is a game in the same way that a leisurely stroll through the park can be a game: Who knows what you’ll find?

Granted, the things you’ll find in The Tower Inverted aren’t a total surprise. To wit, here’s a far from comprehensive list: conical trees, low-slung huts, glowing globes, fractured earth, and towers. So many towers.

Those towers are the real attraction in The Tower Inverted. The game’s ostensible goal is to find the path to the next level, but that is hardly a challenge. “Generally,” its documentation notes, “the exit for each level can be reached by going straight ahead from the starting point.” While you’re proceeding in a straight line, you might as well take in the sights; look upwards and arise the towers that punctuate the landscape.

Although The Tower Inverted is, at its core, a stroll through the landscape, it is not a walking simulator. Its purpose is more specific. The game, to borrow a term from Le Corbusier, is an architectural. It is a carefully designed trip through a sequence of spaces, each level building to a specific conclusion. You can therefore approach The Tower Inverted’s levels from whatever angle you want, but they generally work if you just keep moving forward. The globes that float through the sky like electronic snowflakes direct your eyes as you march forward. Everything is a hint. Everything instructs you to look to the sky.

Everything instructs you to look to the sky.

The heavens in The Tower Inverted are largely empty, pierced only by the sun and the occasional tower, but there could be so much more to see when looking up. The game’s focus on the potency of overhead spaces is reminiscent of “Air Ops,” a 2013 proposal by then-Harvard University School of Design student James Leng. Responding to Hurricane Sandy, Leng proposed the creation of an overhead structure that would tie together all the buildings—many of them towers—on a block. The resultant structure would move a number of functions above street (and water) level and its city block-sized roof could capture significant solar energy, thereby creating a system that approaches self-sufficiency. Leng’s final proposal looked something like a low-poly cumulus cloud.

“Air Ops” had as much to do with planning as it did with design specifics. Zoning paradigms presuppose that buildings do not float atop one another or regularly connect above ground level. (This is a broader issue with how we think of space; above a low altitude, space is not really owned.) To that end, Leng proposed:

A new set of zoning provisions needs to be created to provide proper organizational and volumetric constraints. A new merged parcel ownership model enables individual owners to contribute air-rights potential, structural support, circulation access, or floor area, in exchange for compensation through a combination of renewable energy grants, tax credits, and on-site bonus FAR.

The Tower Inverted, though it does not implement any of James Leng’s ideas, also encourages its player to think about the space overhead. The air in the gameworld has a similar thickness to the ground level. The whole affair is a bit weightless, but it leads to the conclusion that buildings in the air, like clouds, could work. The Tower Inverted has assembled a series of entrancing architectural promenades. If only they concluded with “Air Ops” coming into view.

The game design of the Hunger Games

Calling the design of the Hunger Games terrible is kind of missing the point, right? There’s no fairness intended, no logic, no rules. The “gamemakers” are industrial-scale butchers, striking a balance between mass execution and mass execution that’s fun to watch. They’re games only in the bread-and-circuses sense: distractions. Bloody spectacle. (The series’ ravaged, enslaved nation is called, in a Kojima-esque flourish, Panem.)

Author Suzanne Collins famously says she came up with the idea for The Hunger Games books while flipping between reality TV and Iraq War coverage. That might be embellishment, but it’s also a cogent appraisal of the series as a whole. The films, especially since director Francis Lawrence hopped onboard with Catching Fire, have endlessly debated the packaging of heroine Katniss Everdeen as (depending on who’s doing the spinning) a propaganda figurehead or a symbol of dissident rot. The Hunger Games is frequently accused of stealing its core conceit from the cult Japanese film Battle Royale, but that film spent little time on the society that begat the whole children-murdering-each-other tradition. The Hunger Games, conversely, is more fascinated with the culture around the games than the games themselves.

The focus on the complicated interplay between media, government, and society in Catching Fire and Mockingjay parallels other contemporary fantasy narratives: A Feast for Crows, George R.R. Martin’s fourth book in the Song of Ice and Fire series, downshifted to dig into the utter apathy of the peasantry for the violent, meaningless squabbles of the aristocracy, and the film version of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince luxuriates in the looming twilight of its characters’ adolescence, thick with dread down to its rusted ochre color palette.

THG is more fascinated with the culture around the games than the games themselves

The Hunger Games movies have never been a place for balls-out action. The first film did its damndest to cut and shake the camera its way around the premise of “kids killing kids,” and, while Lawrence brought a steadier hand, an eye for symmetrical compositions, and sharp spatial awareness to the subsequent three films, they remained curiously bereft of the expected human-on-human violence. Mostly, you’ll be watching people run from bees, lightning, mud, mutated dogs, mutated humans, monkeys (possibly mutated?), smoke, gunships, disintegrating floors, and fire, to name a few.

However, this reflects a surprisingly consistent belief lying below the films’ big-budget exteriors: human life is sacred, and taking life fucks you up forever. The films don’t revel in violence; they don’t make it appealing to watch. The Kurosawa-esque jets of blood that punctuate Battle Royale act as outsize expressions of emotion; these kids literally wear their hearts on their sleeves.

The Hunger Games has larger concerns; the violence is done by the state above all else. Jennifer Lawrence plays Katniss as a raw nerve, a strong-willed girl nonetheless being ground under the heel of something massive and uncaring; when she suffers a panic attack brought on by PTSD or bursts into uncontrollable sobs, it’s painful to witness.

In the final film, Katniss swears off fighting entirely, saying that rebels and loyalists alike are being cajoled into violence by the Capitol. Their fight isn’t with each other, but with their oppressors. Of course it turns out that it’s not just the state that’s willing to beat its opponents into submission; French Royalist Jacques Mallet du Pan’s “the Revolution devours its children” has perhaps never been so bluntly rendered.

Human life is sacred, and taking life fucks you up forever

But rather than risking cheap Bioshock Infinite-style moral equivocation between the oppressed and their oppressors, Mockingjay Part Two wisely gives this some nuance. It’s not that the revolution itself is corrupt or made lesser by this turn of events. It was merely co-opted by an opportunist.

Mockingjay as a whole is an impressively funereal affair, leaching nearly all color out of the proceedings, both literally and figuratively; save for Jena Malone’s sardonic Johanna Mason, whose glorious roast of Katniss throws darts at her martyr complex and “tacky romance drama.” The climax of Part 1 is a legitimately tense Baby’s First Zero Dark Thirty set piece, only dulled by the fact that nothing really happens after all, and Part 2 features at least three of those scenes, including a painfully protracted sewer crawl that finally explodes in a whiplash bloodbath.

Anything other than grim, though, would betray the careful work done to this point. The resolution of the plot proper is rushed; with the amount of time allotted to the tedium of war perhaps slightly more attention could have been given to the thematically juicy denouement, and the near-absence of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Machiavellian, inscrutable Plutarch Heavensbee (and I’m not just talking about his name) severely weakens what is there.

But Katniss herself doesn’t get a happy ending. The film is committed to the rendering of her trauma to the exclusion of everything else. There’s no schmaltzy Harry-putting-his-kids-on-the-Hogwarts-Express epilogue. Superficially, the final scene of Mockingjay Part Two seems to hew close to that formula: we see Katniss many years later in a pastoral domestic tableau. But the war’s not over. In the book she describes the land she and her family live on as “a graveyard.” She’s there every time she closes her eyes. She’s there when she looks at her lover, when she goes hunting, when she falls asleep. All she can do is try to live for all those who didn’t; all she can do is push through the trauma for another day and try to make it all mean something.

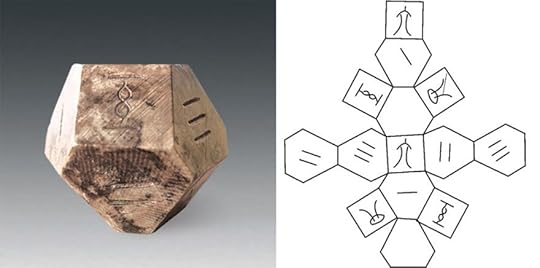

A 1,500-year-old board game has been unearthed in a Chinese tomb

When one thinks of the tombs plundered by videogame heroine Lara Croft, or even legendary adventure film archaeologist Indiana Jones, untold treasures and riches typically await them. During a 2004 excavation in China of first emperor of the Qin dynasty Qin Shi Huangdi’s self-constructed, terracotta warrior guarded, 2,300-year-old tomb, various artifacts were uncovered. Though not entirely reported until a full decade later in 2014 Chinese journal Wenwu, and translated recently into English and published in the Chinese Cultural Relics journal, the surprising find of an ancient board game was uncovered.

The ancient game, having been unplayed for approximately 1,500 years, was discovered in the heavily looted tomb along with a skeleton, presumably of one of the tomb’s aforementioned grave robbers. The game’s pieces consist of a 14-sided die (carved out of an old animal tooth), 21 numbered rectangular game pieces, and a slab of broken tile, thought to be a piece of the game’s board. The reconstructed tile was decorated with two eyes, which were painted amongst stormy cloud and thunder sketches, as archaeologists reported in their findings.

The game’s pieces are reported by archaeologists to potentially be of “liubo,” mostly called “bo” for short. “Bo” seemingly vanished from the history of ancient Chinese board games around 1,500 years ago, and researchers have remained at a loss as to how the game was played, as well as being unsure if the rules of the game even varied from generation to generation of players. The closest clue is that of a 2,200-year-old poem by Song Yu, which recounts a game with similar pieces to the ancient board game’s artifacts found over the years.

The 14-faced die is where this ancient game gets particularly interesting. Twelve sides of the die are numbered one through six in the ancient Chinese calligraphy of zhuan-shu, or “seal script,” which existed as the formal script for all of China during the Qin dynasty. However, the remaining two sides are blank – entirely vacant of any marks. Even with this new discovery, “Bo” remains a mystery to all.

///

Images courtesy of Chinese Cultural Relics

How Battlefront is both the past and the future of Star Wars

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

A month before the December 18 release of the seventh Star Wars movie, The Force Awakens, fans can get their fix of light sabers, starfighters and wookies in a galaxy far, far away inside EA DICE’s online shooter game, Star Wars: Battlefront. Drawing heavily on the original trilogy (Episodes IV, V and VI for the uninitiated), as well as from the new film, the game hopes to bridge the best of Star Wars in one epic online battlefield. But with a franchise so vast, and expectations so high, is it really possible to unite 38 years of stories, millions of fans and one galaxy into something coherent?’

“To me, and to the vast majority of fans out there, Star Wars is one place,” said Battlefront design director Niklas Fegraeus, referring to George Lucas’ vast and complex universe. “We tend to separate the original trilogy and the prequel trilogy and new films — but they all take part in one universe,” he said, adding that coherence is not just about connecting the dots. Fegraeus is almost evangelical about the possible breadth of Star Wars. “It has these different stories,” he explained.

Coherence doesn’t just come from the details, it comes from the way the world feels

This single universe vision is what lies at the heart of Battlefront. It’s not Star Wars as a single myth, a bedtime story told the same way every time — it’s Star Wars as an enormous world in which to play. In Battlefront, the coherence doesn’t just come from the details, it comes from the way the world feels. “You know when you watched the films for the first time and the universe was believable and relatable?” Fegraeus asked. “Science fiction prior to Star Wars was a lot of super alien environments.”

The feeling of believability is exactly what makes Star Wars, well, Star Wars. As in the movies, where viewers get transported to a fantasy land, Battlefront offers a fully immersive experience. Players can visit familiar planets, engage in multi-player battles, “fly” the Millennium Falcon or a TIE fighter, and become the heroes or villains they know so well from the films.

In order to achieve this immersive intimacy, Fegraeus and his team visited the original shooting locations for the planets of Endor, Hoth and Tatooine, where they captured the sounds and feels of those distinct places. It was this process that Fegraeus sees as central to achieving the “reality” of these fictional locations. When the team was sitting in front of their computers in Sweden, it was helpful to have traveled to the places they were trying to recreate. This same process informed how the developers created Battlefront’s new world, Sullust. An expansion of a throwaway line from Return of The Jedi, this volcanic world is perhaps the perfect symbol of the meeting point between the old and the new. The team created this new planet by using the same methods as capturing the old ones, traveling to Iceland for inspiration.

Then there is Jakku, the DLC map that allows players to fight in the battle that takes place 29 years before The Force Awakens and forms a key part of the film’s backstory. A key location for the new trilogy, its inclusion in Battlefront means that players will understand how the planet came to be scattered with the remains of Star Destroyers when they rush to the cinema. Placed alongside the rest of Battlefront’s planets, Jakku suddenly becomes part of a history, a universe of stories that, no matter how distant, can always be bridged.

For Fegraeus that is what, even after living and breathing Star Wars every day for the last two years, is so exciting about the game’s universe. He explains how his nine-year-old son loves Star Wars but that the books and games change the experience. “Star Wars is a mixed bag of all these narratives, all these characters and all these places,” Fegraeus said of his son’s view of the story. “It’s all just Star Wars.”

Battlefront, both in the painstaking detail of its creation and its intention to capture the feeling of Star Wars and not just the facts, is testament to this view. Many hope that The Force Awakens might be part of a grand return for Star Wars, a comeback of legendary proportions. But if Battlefront’s careful act of bridging tells us anything, it’s that, in reality, Star Wars never left.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers