Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 191

November 23, 2015

In praise of Mega Man X

Going fast is easy—the challenge is in reacting to the unwritten near-future while maintaining environmental awareness to avoid running into shit. For all the risks to life and limb, the human brain and body craves the thrill of speed. As such, even relatively primitive virtualized acceleration titillates. In the 16-bit era, games like Sonic the Hedgehog and F-Zero managed to create a placebo of velocity; my muscles tingled at every near-miss and last-second pass, or more often my ears throbbed with the rage of repetitive crashes. A lack of larger peripheral vision is what held back the otherwise stylish and fondly remembered 2D Sonic games: the sense of perception was too narrow. You were simply a cerulean blur hitting the G’s, but myopia and mass kept you crashing until each layout was adequately memorized.

It’s only recently that I’ve recognized the importance of speed in another Super Nintendo title that has been fundamental to me. Mega Man X harnessed the opioid-like draw of speed while providing enough visual context to manage and utilize momentum for total mastery. This was a reboot of sorts for the NES classic Mega Man, a game about a blue cyborg and the various tool- and element-wielding robot masters he challenged. When a boss was defeated, Mega Man gained a new weapon, and thus a decade-long franchise and mechanic was born. X brought the Blue Bomber into the future of the future (the year 20XX, to be exact) and was his first appearance on the SNES, fawned over upon release in 1993 and canonized for its tight controls, frenetic and colorful visuals, and Iron Maiden-inspired soundtrack.

Most importantly, Mega Man X found a new way to deliver a headrush of speed, and all it took was abandoning all pretensions of realistic inertial physics. On the surface MMX was not a game about speed, but once the dash boots were claimed, the world truly cracked open and allowed X to compress distance into a blaze while maintaining visual awareness on a 4:3 cathode ray tube television. Where Sonic constantly pancaked into the unseen, for X most walls transformed into launch pads and complete navigation was enabled through cyber-pirouettes with a buster cannon to clear the obscured path ahead.

I did at least one playthrough of the game on a nearly daily basis, starting in 6th grade, cross-legged in my shared concrete bedroom in university student housing while my mom finished college. This lasted pretty much until I graduated high school and took the cartridge back to that same university for myself. I’m almost more proud of my ability to wipe up the Maverick menace in 45 minutes without using any special weapons and getting every upgrade (including the secret Hadouken) than my secondary education. Of course, this personal high point is glacial by today’s glitch-informed speedrunning standards, but every record is possible only through the dash boots (and the surplus of disposable hours available to a teenager).

MMX’s dash goes against known laws of nature. One can’t just dissipate momentum, whiff, full-stop, apropos of nothing, except if you are robot (or if you are the drummer in Napalm Death). Mid-air dashing near an open pit is no problem, just ease up on the d-pad and you float down like a single drop of rain and not a pixel past the ledge. In the context of the game this is all totally acceptable. Only when I am in full X cosplay mode, parkouring all over the zoo and pretending that the assorted animals are actually industrial cyborgs hacked for violence, am I confronted with the absurdity of going from 30 miles-per-hour to standing stone still, instantaneously. And not only that, X can then potentially flick around again, becoming a tornado of dashing bullets. This is what a ninja is supposed to feel like—the freedom to eye-blinkingly teleport around bosses and their measly weapons—and MMX sets the standard.

“Mega Man in Everything but Name”

Some Mega Man games prior to X did have a navigationally beneficial slide, but otherwise Rock was confined to jumping at the right time: not too soon, not too late. With the dash, X truly got horizontal. The other two MMX games on Super Nintendo left the dash relatively untouched; if it ain’t broke, etc. But after that, they never quite got it right again. Past those entries, movement in general would become more cumbersome and clunky as further entries materialized, especially throughout the PlayStation era. He had big open worlds to trot through. Mega Man Zero for the Game Boy Advance resurrected ninja-dashing and much about what made the X games such speedy delights, but the difficulty and claustrophobic screen size were too much for many. Thus, with nary a whimper, Capcom left Mega Man X and his dash to rot.

///

But others are picking up the slack. Among them is Keiji Inafune, one of the original developers of Mega Man and the person who held the reins for the majority of side-scrolling games that feature the Blue Bomber. He made internet waves with his “Mega Man in Everything but Name” game Mighty No. 9, one of the most high-profile crowdfunded videogame revival projects. This includes ramifications positive and negative, including entitled backer flare-ups and developer delays. As one of those backers, I was given a demo of the near-complete game with four levels and many barely endurable minutes of mostly unskippable voice acting.

Alas, Mighty No. 9 has lots in common with the PlayStation era of Mega Man X games. Perhaps it was naive to hope that, since I was actively trying to forget the driftwood dialog, high-school theater level construction, and swampy controls of those games, maybe Inafune was, too. Mighty No. 9 is not unendurably mired in these complaints, but I am disappointed that they went with polygons rather than sprites and won’t let me skip through the introductory chaff. Beck’s in-game design is stunted, bulbous, and bland; more a bobble-headed vinyl toy with oversized mitts, less a badass robot. It’s not exactly revolting, but it does feel uninspired. However, my ultimate concern is the potential of an updated dash, and Inafune’s team has surprisingly improved it.

You could beat the original MMX without the dash, though it would be a slog. The same could be said for Mighty No. 0, presumably. One needn’t dash to get through most of the levels, but that’s what they were designed for. The main difference here is that the dash is also a form of non-violent assault—shoot the various malfunctioning robots to wear them down, and then dash through them to repair the nefarious programming causing them to run amok. Dashing through enemies brings greater bounties, temporary ability bonuses, weapon enhancements, and if you can chain multiple dashed-through bots you build up a multiplier combo. None of these aspects are particularly game-changing, but in a near-Bloodborne style risk-reward scenario, you can throw yourself at the enemy and potential harm to garner a better payoff. In MMX it was the dash that kept you safely ensconced on the opposite edge of the screen, but Mighty essentially requires you to do damage and then collide head-on into most enemies and the bosses.

When I do occasionally let too many pellets fly, destroying rather than saving a minor enemy, guilt immediately pangs me. Given that throughout the history of Mega Man most bad guys have been made homicidal against their will, it’s compelling to consider salvation as opposed to wanton destruction. I don’t know if there are any narrative or mechanical consequences to choosing outright murder over the more dangerous but lucrative dash-save method, but having never been given the choice before I’m energized by the heightened tension of the difficult but slightly more morally compelling option.

Mighty No. 9 has lots in common with the PlayStation era of Mega Man X games.

My enthusiasm for Mighty No. 9 is trepidatiously renewed despite the underwhelming in-game art. It ain’t no Mega Man X, but I have faith that Inafune and his team is looking to more than rip off their own past. But it’s such a ripe history to explore, and others are also willing to excavate and innovate, including Batterystaple Games and their upcoming 20XX. Following a successful Kickstarter of their own (when the game was originally called Echoes of Eridu), 20XX is currently in Early Access Beta with a final release scheduled for 2016. The main developer counts Mega Man X as his direct inspiration, though to do otherwise would be a bald-faced denial. The title itself is a straightforward reference to MMX and its gameplay follows the same model of running, jumping, shooting robots, collecting weapons based on the bosses defeated, and most importantly: dashing.

20XX updates the recipe with some of the current trends; “rogue-lite” random elements and co-op. Like last year’s Crypt of the Necrodancer, each attempt at the game offers one life, and when you die, all progress is lost except for the Soul Nuts you’ll spend to unlock more potential items for the next go-round. Each level follows a theme and pattern, which isn’t breaking the contemporary “rogue” mold though that’s fine. They are environmentally familiar while avoiding outright memorization, which makes your one life and each tick of health more precious and forces you to learn dashing with purpose—an eye always looking ahead. There are animal-themed bosses and enemies which are appropriately outlandish but also subject to future changes, and the co-op is a fun way to compress the couch cushions. Overall, it inches very near to the d-pad rooted “feel” of MMX.

20XX isn’t perfect a perfect analogue though, nor could it be. Part of this is the dash, which is uncannily close to the source material, but still not quite there. Dashing hinges on miliseconds, and 20XX is a hair slow. The thinnest hair, but I feel it, though it isn’t enough to cause me to condemn this game which I have been truly enjoying and whose final release I eagerly anticipate. Like a musical harmony in the slightest perceptible discord, it buzzes and detracts ever so slightly.

Perhaps this says more about me, and the natural fear of change. 20XX is as close to a fresh but familiar Mega Man X experience as I will get, outside of some romhacks and forever-in-development fan tributes that I can’t help but also hopelessly pine for. But it has a GoBots sheen to it, an honest and loving tribute more than outright Chinese bootleg, but an “off” quality nonetheless. The ancillary artwork is charming and well executed, painting with the colors and flavors of the source material, but the the active on-screen characters feel like paper dolls in that “flash” way that I just can’t get behind, closer to the Mega Man cartoon than the sprites of MMX. It’s entirely a subjective reaction to the aesthetic, where I recognize the hard and successful work of these developers based on a series they clearly love as much, if not more, than I do.

Which is my problem, as a fan of a game old enough to drink, that I played so much so as to set the bar for the innate friction of all side-scrolling games since. I’ve been chasing the dash for so long that maybe I don’t even recall what it originally felt like. 20XX and Mighty No. 9 are the closest I’ve seen, with enough evolution to avoid mimicry. Where I am stifled in my desire to travel back into an idealized era that is most certainly not what I remember, others have taken the mantle of Mega Man X and evolved it rather than simply cloning what worked. Trusting in them, I look forward to falling in love with the dash all over again.

November 20, 2015

The Games of Los Angeles

Our upcoming print reinvention is going to zero in on the creators we love and their current projects. Three of our favorite upcoming games are from independent Los Angeles-based developers doing exciting, diverse work that nonetheless shares strong aesthetic vision full of pixels, pastels, and bold geometry. They take inspiration from LA’s cinematic history, its geography, and their local hangouts in ways both obvious—the heist hijinks of Quadrilateral Cowboy—and subtle—the way that LA’s growth has erased much of its history inspired Donut County. You can look for more in-depth looks at the developers when our magazine launches next year.

Hyper Light Drifter

Heart Machine’s Hyper Light Drifter is an action game set in a gorgeous pixel-art fantasy world where everything is out to kill you. It’s a mysterious, hostile wilderness painted in hot pink and teal—even the text is in indecipherable alien hieroglyphics.

The action is tight and snappy; a Drifter cabinet would be right at home in your local arcade. This game has been a long time coming, but every aspect of it looks and feels pored-over and impossibly stylish. It’s also surprisingly personal in a way that’s easy to miss in between all the hacking and slashing.

Quadrilateral Cowboy

Most of Brendon Chung’s games are about spies, heists, and murder. His latest, Quadrilateral Cowboy, is about all that with a cyberpunk sheen. He’s sort of a cubist Michael Mann, rendering quotidian moments and sudden violence with equal care. Chung brought cinematic editing techniques to videogames with Gravity Bone and Thirty Flights of Loving, but Cowboy’s gimmick is a sort of single-player co-op, putting the player in control of a team of hackers as they pull off sabotage, heists, and corporate espionage.

To do so, however, she’ll have to wrestle with a clunky, outdated desktop terminal and dig deep into a DOS-style command interface. Chung wants to keep the learning curve shallow, so that by the time you’ve grokked the ins and outs on a conscious level, you’re already a top-flight console cowboy.

Donut County

Ben Esposito’s Donut County presents an idyllic American Southwest full of soft pastel colors and gradient sunsets. And then lets you swallow it all up.

One day a girl working at a donut shop gets a delivery from some raccoons: donuts that spawn “mysterious growing hole[s].” The game is a sort of physics toybox, then, where you play as a tiny void out to solve puzzles and consume anything in your path. It’s got a distinct Katamari vibe, if Katamari were a little more earnest … and a little more inexplicably eerie. Esposito was inspired both by a local donut shop and the more intangible notion of “holes”—the things displaced and erased by the sprawl of modern LA.

Free Beer, Great Games at Movable Play

Do you like free beer? Do you like free food? How about the exciting future of design forward mobile games? You’ll find all three at our monthly Movable Play event, continuing Tuesday, December 1st. This month we have some very exciting speakers. On the creative side of things is Çağıl Bektaş, the creator of Vektor, the fast-paced driving game that will make you equal parts anxious and excited. On the business side we’ll be featuring Jesse Divnitch, VP of Product Strategy at Tilting Point. And lastly, we’ll be featuring Edgar Castro, a graduate of Parsons The New School of Design and his work, Howl. Join us for our last Movable Play of 2015, as always at Dots studio at Betaworks in Manhattan, Tuesday, December 1st at 7:00 pm.

Powered by Eventbrite

How temporary structures inspire architectural innovation

In many ways, the architecture of modern metropolises largely consists of simply lining each city block with minor variations on the same massive, contemporary rectangle of a skyscraper. The sheer size of these structures is impressive at first but, after a while, their similarity can leave a city feeling drained of personality. It’s difficult to blame corporations for choosing “safe” designs on multi-million dollar buildings that are meant to last decades, but once the initial impact of their size wears down, these soulless monoliths fail to leave much of an impression. So what happens when architects are given the freedom of designing temporary structures instead?

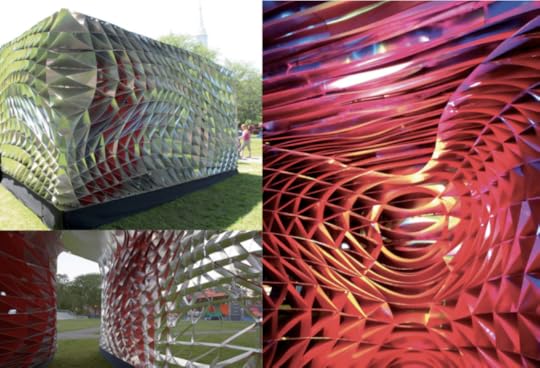

Evolvo, an architecture and design journal with an eye for the avant garde, aims to answer this question with its latest issue, entitled “Temporal Architecture.” Following pavilions, installations, and pop-up structures only meant to stay up for a limited time, the book is filled with creative designs that look less like corporate headquarters #42 and more like industrial coral reefs. As architects are given greater freedom to iterate without the worry of leaving a potential costly eyesore that will stand for decades, the standard sleek rectangle of New York’s Midtown is ditched for asynchronous, twisting patterns and dazzling bright colors. “The relative small scale of the projects allow for forward-thinking concepts to be developed and materialized,” explains Evolvo.

asynchronous, twisting patterns and dazzling bright colors

The issue features work from an extensive selection of architecture’s brightest, including the Yale School of Architecture and SOMA, the firm behind Manhattan’s controversial Park51 Islamic Cultural Center, which was unfortunately never built despite its proposed community value and eye-catching honeycomb design.

Standouts from the issue include a Parisian housing development that looks like a Jenga tower from Godzilla’s game room, as well as Resinet Pavilion, a twisting outdoor hallway that reinvigorates its space with a hand-woven nylon pattern that shines like the scales of a brightly-colored deep sea fish.

A stunning break from the norm, Evolvo’s “Temporal Architecture” can be bought in either print or digital form over on their site.

The code-generated architectural drawings of Miguel Nóbrega

The computational science of randomness is a way to establish a firm balance without bias; a gateway between an artist and code itself. In videogames, randomness can take hold anywhere from a laughable Bethesda glitch, a serendipitous discovery in Metal Gear Solid V, to the randomly generated levels of iOS indie hit Downwell. For Los Angeles-based artist Miguel Nóbrega and his online art gallery “Possible, Plausible, Potential,” randomness is implemented as a way to strike a balance between coding and the artist.

none of this illustrated architecture can actually exist.

Using a plotter machine armed with colored markers, Nóbrega has written lines of code with an architectural aim to craft “generative drawings,” as the pieces’ webpages describe, each fitting into a specific theme in the virtual gallery—“POSSIBLE STRUCTURES,” “POTENTIAL SCULPTURES,” “PLAUSIBLE SPACES.” The plotter is a combination of processing, an open source programming language, and a CNC vinyl cutter, with seven colored permanent markers attached. As the code is written, the plotter draws with extreme precision architectural shapes and lines: floors, walls, stairs, columns… basically anything with the possibility of being real. But here’s the catch: Nóbrega inserts randomized code into his already existing script, thus creating unpredictable turns.

Nothing in Nóbrega’s art is viable in a practical sense: none of this illustrated architecture can actually exist. The lines are precise, the texture almost feels tangible, the eye jumps all around the heavily detailed, machine-generated illustrations, not knowing where to rest. None of it is actually possible, plausible, or has any potential, but that’s the point, isn’t it?

View more of Nóbrega’s art on his online gallery, Superfície.

Save your dying sister by exploring this strange 3D world through words

I remember reading once that a good fiction writer will paint images in your mind. This is vital to the craft; not just stating “a tree” so readers imagine a tree, but describing it so that this is uniquely a tree of your creation, one that will be remembered with intense detail if, say, referenced later in the text. Porpentine has not only injected my mind with everlasting and often gruesomely detailed images (being penetrated by a cyberqueen will never leave me) with her Twine work over the years, but has caused visceral feelings to thrive around my body, contorting my face as I read. She excels at this.

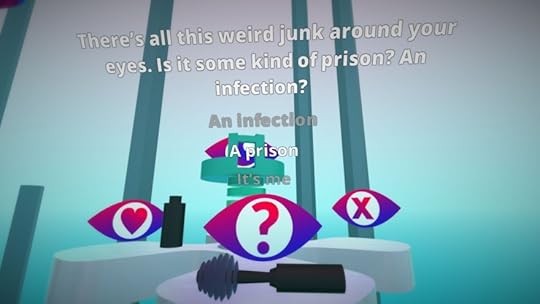

Her ability here is why I’ve never felt it necessary for her written work to ever need more than a custom font and a delicately selected hue as a background. Her choice of music doesn’t go amiss, either. My stance has always been that this limited format of text and hyperlinks couldn’t be realized with the same guts if it were a 2D or 3D world. It needs that vast imagination space that lets me turn her precise yet knotty sentences into dreamlike projections in my mind. But now that I’ve played Bellular Hexatosis—which Porpentine co-made with Brenda Neotenomie back in April for #adventurejam—I’ve changed my mind. It’s a surprisingly accomplished adaptation of Porpentine’s style as a 3D adventure game.

It’s about finding the antidote that your sister needs to cure her Bellular Hexatosis. This unknown disease is increasing her fragility day-by-day and as her only aid you care about fixing her deterioration deeply—the intimate conversation with her tells you this much—hence you travel the world to help her. Oh, and your sister is an enormous spiralling tower of petrified ocean, by the way. Typically, such an unusual form is something that Porpentine would craft with her words, but in Bellular Hexatosis it is rendered with 3D graphics. Luckily, it doesn’t reduce any of its otherworldliness, which is what I fear when something imagined is given a solid body, denying me access to visualize it from scratch.

graphics act as the bones, the words as flesh and fluids.

But, importantly, Bellular Hexatosis doesn’t let its graphics do all the work. It strikes a pleasing balance between direct depiction and textual implication. When you travel to the Seaside area, you can see chimneys poking out from under the water, billowing smoke. But it’s not until you click on the text hovering in the sky and start to read that you learn that these chimneys belong to underwater soda factories where vampires are concocting a new flavor to block the sun. Yep, it’s Porpentine in full swing; you’re shown a chimney but it’s her words that illustrate the factory below and everything inside it.

It’s not only that compromise that makes Bellular Hexatosis work. It’s also that the sense of exploring a space Porpentine manages through connecting text like rooms through killer use of the hyperlink is honored. The game opens up with the statement “Click words and objects to proceed.” Following this instruction, you navigate the 3D world of Bellular Hexatosis through the same means you would a Twine adventure. You stand static in a spot, able to look around the world from a first-person perspective, and to advance to the next static position you have to look at, read, and then click hovering sentences (side note: I love the way you zoom between locations to a great rushing sound, as if the game was showing the notoriously slow-moving Myst how it’s done). It works brilliantly to build the world as you move through it; the drowsy music and graphics act as the bones, the words as flesh and fluids.

And on that topic, one Tumblr user rightly makes a comparison with the writing in Bellular Hexatosis to the work of microbiologist and sci-fi author Joan Slonczewski. Porpentine employs similar word invention as the forebears of biologists and chemists to label her fictional diseases and chemicals. This pops up later as the gory webbing inside your body has its cavities labelled once you enter it (yep, that’s a thing that happens). Bellular Hexatosis also shares a setting with the water-covered moon in Slonczewski’s 1986 novel A Door into Ocean, plus there’s a similar sense of sisterhood and commitment to non-violence between the characters, whether it’s the sentient eyes you meet in the clouds, or your sleepover sex mate.

You can download Bellular Hexatosis on itch.io and Game Jolt, and you can also play it in your browser.

Against child protagonists

Videogames don’t like people. Of that, the overwhelming amount of fantasy, war and sci-fi games, the ones set around goblins, androids and super-soldiers—the ones patently uninterested in real human beings—are proof enough. But even when games profess an interest in personhood and human experience they avoid substantive fiction. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture seems to focus on a village in England, and the relationships between the people that live there, but the people are all dead and instead of seeing them and how they interact with one another you find, merely, their ghosts and some recordings of their voices. Gone Home is the story of a burgeoning teenage romance, two lovers and the families on either side, but again none of them appear on-screen. The Vanishing of Ethan Carter has no living humans, nor does Dear Esther. All the human interactions in Sunset occur off-screen. SOMA claims to debate human nature but almost every character is a robot. The Talos Principle is the same.

The games ostensibly about people and their experiences present, rather than complex, difficult human characters, simply a facade of human life—rather than conversation, situation or struggle, they center on after-the-fact narratives, inner monologues and second-hand reflections. You encounter humanity in games not in people but through simpler, more tangible non-human vectors. You never speak to people, because people are complicated. Instead, you straightforwardly learn about people through architecture, diaries and robots, objects which can purport an essence of humanity but also be used to conveniently sidestep the pressures and expectations of writing and creating a believable human character. I think videogames, recently, have been largely pretending to be about people. Apart from Will O’Neill, through his game Actual Sunlight, there aren’t many game-makers currently working who seem genuinely interested in telling stories about human beings. On the contrary, there are plenty who wish to appear to be doing so, who spin stories without any people in them, and sell them as human interest.

Child characters currently in videogames feel to me the same as the robots

Child protagonists, seemingly everywhere at the moment, from Beyond Eyes to Among the Sleep, The Unfinished Swan to Papo & Yo, The Walking Dead to Brothers, are symptomatic of this uneasy relationship games have with human beings. The child characters currently in videogames feel to me the same as the robots, ghosts or other non-human humans—they are vectors for simplified, digestible human emotion, a way for writers to appear to engage with personhood and human feelings without actually engaging with either. This isn’t to say that child characters or children in reality are incapable of representing complexity or being complex. It’s certainly not to say that children are anything other than human. It’s only that game-makers at the moment seem to be using children characters as an excuse for timid, slightly but not really emotional narrative, as a way to look involved with difficult human experiences like loss, fear and sadness while in fact keeping them at a safe distance.

The little girl’s cat dies in Beyond Eyes. The world of The Unfinished Swan is slightly cold and ominous. These are minor, slight little stories. Even games supposedly addressing somber topics like death (Among the Sleep), alcoholism (Papo & Yo) and domestic abuse (Brothers) excuse themselves, via their child characters, from delving into the subject matter, each one being so wrapped in metaphor and twee, pleasing imagery that you can forget the games’ stated stories. Brothers is a fairytale. Papo & Yo uses the aesthetic of a child’s imaginary world and friends as cause to never actually show abuse. Among the Sleep is a bait and switch. Its twist ending is token and trite, the perfect example of when game-makers conflate a child’s perspective with prettiness and simplification. Each of these games hints at something emotional, something saddening or bleak or real, but uses the child character to pull back and shield from that subject matter, to process a controversial or contentious topic into one that will elicit from the player only the simplest responses. The endings of these games are either “happy” or “sad”—it always seems that the child characters are intended to eliminate any doubts or lasting questions, and convert complicated real-world issues into easy, satisfying narratives.

As well as a disservice to topics like drug addiction and child abuse, this kind of writing smacks to me of an unwillingness to enter adulthood, of game-makers scared to do battle with human problems and trying to dodge difficult subject matter by persisting with the idea that basic sentimentalism is magical. I personally don’t buy it. I don’t think the easy, simple emotion found in a lot of games with child protagonists has any worth whatsoever. Moreover, I don’t think children are really this simple. My own childhood was never simple, never fully “sad” nor ever truly “happy.” Like life generally, it was complicated—games seem to want to think otherwise, and insist that children are emotionally much simpler than adults. That’s not true. Children suffer. They think. They worry. It’s not a terrifically written game, but The Walking Dead at least features a child protagonist who is, comparatively, complex, who has flaws, worries and emotions beyond those that can be easily compartmentalized. Limbo, too, seems to understand childhood and children. It plays on fear and awe, arguably simple emotions, but it never treats the central protagonist as a rare, beautiful, innocent flower—the many ways in which that young boy can be brutally killed implies a willingness by Limbo‘s creators to grapple with the occasionally harsh reality of childhood, as opposed to the empty, tear-jerking simplicity of something like Beyond Eyes.

I don’t think children are really this simple.

Child protagonists feel to me not just a sidestep away from dealing with true adult stories, but the creations of game-makers blindsided by nostalgia. They wish to simplify and make magic frightening human experiences while still appearing narratively confident. In doing so they end up writing child protagonists who are clean, basic and untrue, child protagonists who from my experience must be incredibly alienating to real children.

Why visit your relatives when you can send them creepy robot cats?

Well, this is creepy.

Toymaker Hasbro has taken it upon itself to solve the problem of senior isolation by creating “Companion Pets,” which is a less horror film way of saying “mildly robotic cats.” These cats do not even appear to occupy the uncanny valley. They look stiff and plasticky and move in about three mechanical ways. But maybe they could occupy your grandmother, and wouldn’t that be nice?

At this juncture, I should clarify that “Companion Pets” is apparently not a hoax. The toy’s website includes the following statement: “HASBRO’S JOY FOR ALL is proud to support Meals on Wheels America and its efforts to reduce senior isolation and hunger as a sponsor of its Spark the Movement event.” So, if this is a hoax, the humour’s pretty damn dark. While we’re on the subject of things that are real, senior isolation really is a big problem. As British Columbia’s Ministry of Health notes:

Social integration and participation of older adults in society are frequently seen as indicators of productive and healthy aging and it is widely accepted that social support has a strong protective effect on health. However, an increasing amount of seniors may be at risk of being socially isolated or lonely. This may be due to a number of factors such as increased likelihood of living alone, death of family members or friends, retirement or poor health. With current trends such as encouraging seniors to live longer at home or in the community, a highly mobile society and fewer children per family, the issue of social isolation takes on a new importance.

But come on. I’ve seen Robot & Frank. I know how this story ends:

Technologies designed to combat isolation often feel a bit off because they’re trying so hard. If you can’t be with a living thing, they seem to imply, why not be with something that’s almost living. There’s something to this idea, but it can easily cross the line into creepiness. You might be okay with friendly robots or robotic cats, but what about blowup dolls? Probably a step too far. Which is not to say that isolation cannot be countered using technology. Said technology does not, however, have to be an exact replica of that which it is supposed to replace. At a time when people are living longer and further apart, Skype and social media are valuable. Moreover, tablets offer sufficient affordance for elderly users. Fake living creatures aren’t always the answer.

Or, you know, you could just visit your relatives. That would be nice. (And your mother asked me to remind you that you never write or call. Do something about that?)

Still, it could be worse:

Find out more about Hasbro’s “Companion Pets” on its website.

The Witness won’t have music, and for good reason

The use of silence can be just as important and impactful as a well-chosen or carefully crafted soundtrack. This is the gist of what Jonathan Blow, creator of Braid, has to say in a new blog post on his upcoming puzzle game The Witness.

According to Blow, “The Witness is a game about being perceptive: noticing subtleties in the puzzles you find, noticing details in the world around you. If we slather on a layer of music that is just arbitrarily playing, and not really coming from the world, then we’re adding a layer of stuff that works against the game. It’d be like a layer of insulation that you have to hear through in order to be more present in the world.”

“It has forced us to be very creative with the audio”

But the world of The Witness is unusual. There are no insects, birds, or other wildlife present on the island either, explains Blow. You are completely alone. The utter lack of life aside from yourself on the island means things like wind, water, and the mechanisms of the island’s strange contraptions are mostly what’s left to hear.

You can get a feel for the types of soundscapes The Witness will feature in this “long screenshot” below—a slow pan from one end of the island to another, bird’s eye view, the terrain ranging from beaches to forests, river to meadow. Buildings, bridges, gardens, and more occupy the space in between. As the varied landscape sweeps by below us, so too does the voice of that terrain: slow waves, ocean wind, rushing water, leaves rustling in the breeze.

In a game as lonely as The Witness, the island has always been its most interesting character. We’ve seen plenty of it already, so it’s nice to get a chance to hear it too.

Despite being devoid of people, The Witness will still have a human presence in the form of audio diaries. Blow hasn’t revealed who these recordings belong to yet—that will be part of the puzzle you must piece together. The audio logs will be recorded in English only, with subtitles for over a dozen languages planned at launch, including French, Spanish, Arabic, Japanese, and Polish.

Find the full list of languages, and more information on the sounds of The Witness, on the game’s official blog.

Oneohtrix Point Never talks futurism, nostalgia, and the videogame music that haunts him

A computer doesn’t forget, it deletes. Its memories do not drop off the candle’s wick. Everything discarded is done so by some purpose, the will of the user or an overloaded failure of the hardware. People’s sense of memory can be more convenient; we can amplify the emotions of one moment to captivate the entire chapter. For many, the past becomes nostalgic: it’s easier to snip out the details we’re more often consumed by in the present. Even our feelings about computers gets nostalgic. Garden of Delete, the new album from Daniel Lopatin, aka Oneohtrix Point Never, doesn’t forget.

It is highs and lows simultaneously, a hazy spell cast over old familiars and comforting sounds, the popcorn akin to those old Mind’s Eye shorts, pierced by embarrassments, cornball guitar riffs and mushy oversentiments. Its lead player, a teenaged alien named Ezra, is plagued by acne and anxiety. OPN’s compositions have generally sounded like choirs of the computers, dabs of user interface sounds designed as tools, drawing their listenable properties out like a singing coach. Garden of Delete is more intimidating, though. During the first leg, the music cuts out into dead silence like something’s wrong. One track, “Animals,” feels profoundly sadder than what we’ve usually encountered. There are lyrics, apparently, too distorted and inhuman to naturally pluck out.

I spoke to Lopatin over the phone about arriving to this mood, the realities of touring with your childhood heroes and how we talk about technology. And videogames. Don’t worry. We talk plenty about videogames too.

Zack Kotzer (ZK): So, being frank, I’m representing a videogame magazine. I know it comes up a lot in conversations with you and I’m almost wondering if it’s a good starting point or just patronizing by now, but how have games influenced you?

Daniel Lopatin (DL): Yeah, they’re hard to avoid. I wouldn’t call myself a gamer because I’m just not that good at games at the end of the day. But my friends are. I grew up with videogames, you know. I was born in ’82, I got the NES for my… I don’t know, seventh or eighth birthday or something like that. I loved it, got into it. Went over to SEGA after that, PS1, PS2, PS3, PS4.

ZK: Just straight down the line.

DL: Straight down the line with PlayStation, and I started playing The Witcher ’cause I’d had it for awhile, but I didn’t know what else to do last night, so I just started playing The Witcher. I love videogames on a level that, I think when I was a kid, the fact that they were more fantastical and ridiculous within a closed system of programming… music almost came from the same code as the game did… I think that in a way was interesting for me ’cause you know, it sounds like nothing else. The rest of the time you turn on a TV or something and you hear music. So it wasn’t really until TV where you could just preload audio files into a game, and that was part of the latticework of the game, was just recorded music. That’s when games started blending more with pop culture… to me that wasn’t psychedelic or hallucinatory, looking back I think the music from Metroid stuck with me forever but I couldn’t tell you what the loading screen music from X or whatever.

Music and sound designers are non-discrete. They kind of blend.

ZK: It doesn’t have to be so specific or citational.

DL: I’m just thinking about it. I think in general the idea that videogame music was really composed and melodic in a way that didn’t really connect to any kind of thought form, it was like this strange kind of reality that was somewhere between a score and a little song. That’s what I kind of loved.

ZK: There’s a lot going on with the people that composed that music, because one, there’s the technical limitations, but two, a lot of the sound you’re sort of designing is in a way a tool for the people interacting with this world to be able to interpret different actions or different settings

DL: Yeah, there’s a pragmatic aspect to it as well. I think now, in terms of what excites me about videogame music, is more to do with how music and sound designers are non-discrete. They kind of blend. So, you have this interesting interplay of sound design and music. Sound design’s actually harmonically in the same family as the music and interesting sound relationships emerge from getting through some kind of conflict. That, to me, is much more futuristic sounding. Music, if you just take that whole experience verbatim and say, “Okay, I’m not separating any of these sounds or any of these features, I’m just going to listen to this whole thing,” to me that sounds like future music, that’s how I want music to sound, music that would be on the radio. The new Killer Instinct is totally like that. I’m just so bewildered by all the layers of sound and music that to me it just sounds like truly radical music. And I think some of that came into the new album.

ZK: You’ve talked a bit in other interviews about characters you created for Garden of Delete to be a sort of score to, like Ezra. Did you come up with the characters in this world before you started composing this music?

DL: Completely afterwards. I made the record and then I saw that ahead of me was five months of waiting for the records to come out and I just wanted to do something meaningful. A lot of the press stuff that you have to do, not stuff that you want to do, can feel pretty tedious, so I was like, “I’m gonna have to do that, yes, but I’m also gonna have conversations with myself and thus, a public conversation with myself is also a conversation with my audience.” Really it turns into making all of these weird peripheral ideas and characters and ultimately this fractured universe around the record that I could use to explain the thing I just made to myself or kind of explore ideas around it without being real specific or without getting on a soapbox to say: “This is what my music is about.” It wasn’t at all as conceptual as it might occur at first glance; it was really just vague thought and universe building.

ZK: Did you start to view the music differently after you created these people to inhabit it?

DL: Maybe a little bit. You just notice certain anomalies or certain parallels or certain strange little morsels of information that kind of tie things to each other, but again, it’s just like throwing a bunch of stuff in a tumbler, seeing what emerges and ultimately just enjoying all these relationships and ideas, just seeing what’s humorous or seem like they could maybe branch out and be something else. Or use it as an exercise to develop ideas for the music video. For me, under the perfect circumstances, this whole universe can be a graphic novel, or an absolutely insane film, or a game. I don’t think that I endeavor to do all those things or claim that they’re doable, but I love those kind of strong ideas out there and just seeing their results. New ideas that come from them.

My favorite synthesizer is me.

ZK: You seem to leave the window open a little bit with the video for “Sticky Drama,” which is a pretty literal live-action role-playing game.

DL: Yeah, completely, because me and Jon (Rafman), once we got the ball rolling, I had this universe and these characters, and I brought them to Jon. So we started working with the more plausible things, and he has a way of twisting, fragmenting things into his own world view, so naturally it became much more collaborative and much more interesting than anything I could have possibly come up with on my own. But you know, we were laughing that this could be, we can do a whole Troma thing off just this one idea. It could be completely a radicalized, sub-basement version of Disney.

ZK: Who’s in your big tentpole franchise? Who’s your Avengers roster?

DL: Growing up in Massachusetts and going to school at Hampshire College, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was always the thing. I would hope that from the video it seems the villain, who’s collecting the Tamagotchis selfishly, kind of in an Icarus-like manner, trying to instrumentalize all his army and imperialize on everybody’s fun, and ultimately he’s killed because of his desire to have every single Tamagotchi. I think he would be a star at the end, he’s kind of Shredder-ed out. But, as I clearly would have to mark this as a major player. I think a movie would be sweet.

ZK: How would you describe your relationship to sort of the technologies we see come and go, as we grow up?

DL: I remember sitting at a bus stop with my grandpa, I was pretty young, maybe I was 17 or 18. I really see my grandpa as getting up there in his years, you know we used to hang out all the time, and I was pretty sad because I felt like maybe he was slowing down. I remember sitting at this bus stop with him and the cars going by and I was like, “Grandpa, what do you feel when you see all these cars? You’ve seen cars change so much for so many years. Do they look strange to you?” And he said, “I don’t know, they’re cars.” So, as I get older I feel like maybe he’s right, even though I feel like I’m sensitive to these things more than a guy like him. I wish I could say that I felt that the world was like changing as quickly as (futurist Ray) Kurzweil wants it to. To me there’s so many fundamental issues that I have to on a daily basis with the way people communicate, with the way people treat each other, with any number of unfortunate kind of realities seem to emerge.

Any time I’m doing something or just going through an airport I just feel like, “Why am I being pasteurized?” Why am I being put through this? If there is a future and there are airports, 50-100 years from now, they might laugh at the sort of draconian way we dealt with security. I think there’s probably much more effective ways to recognize who people are and get them through places on this earth in a more civilized way. There’s other things that amaze me, like I remember clearly a time when it wasn’t so easy and so obvious to get a car and just go from one place to the next. I feel like in some ways do people really understand what a luxury it is to be able to get money out of a machine? Or jump into an Uber? But we adapt to these things so quickly, and we just accept them.

ZK: I often wonder with the generations below us, what their perception of computers and the Internet and technology are going to be, since it’s so much more encompassing and resourceful for them. Like, full-time access to all these things, but when I was young I remember dial-up and I remember it just being this frustrating tool, that had its hiccups and took its time to process.

DL: Exactly, that weird dial tone sound and you had to wait, had to connect, then you’re loading slowly. It’s not that far away. I definitely remember that as well. I wonder if it’s because we so quickly adapt, and become in a technocratic society, even biologically we’re learning to forget the difficulties of technology very quickly. It’s funny because someone was recently talking to me about the phenomenon in which essentially memories are stored in our DNA, which makes perfect sense if you think about it.

ZK: Someone brought that up to me to, the concept that certain traumas can affect the body on a strictly genetic basis to even pass on from one person to the next like a small dab of evolution.

DL: It was even in the news recently, maybe a couple days ago. It makes perfect sense—that would explain instincts so well, because if you have these traumas, these understandings of these fear-based, implicit reactions coated into your DNA, or thousands of years of being traumatized by being attacked, I’d understand why we need to react to those things. I would imagine at some point we are going to have all these computer memories as well, or teach us how to deal with emerging technologies. We adapt really quickly, on some levels, so that’s a positive.

nostalgia is a feeling that the past is somehow intrinsically better than the present. And to me that’s unfair.

ZK: I don’t want to do a misreading, but I feel like there’s a bit of this even in your own music, because so often you’ll take familiar digital sounds or items and recontextualize them in sort of the mood or the setting. Like going all the way back to “Child Soldier,” it sounds like you’re having a bad trip in an arcade. Street Fighter, Space Invaders are just sort of jumbled together to form sort of a chorus. Even in your new song, “Ezra” there’s wails of guitar that don’t really feel like the kind of setting that the usual shriek of a guitar would accompany.

DL: I tend to think about it in terms of honesty. Honesty is part of being an artist. But to me I have this thing where I feel that music needs to encompass the entire situation that is listening. Listening is, to me, part of music-ing. When I try to write a piece of music, it has functionality. It’s a song, but beyond that the way that it’s arranged, the way that things are kinda smashed together, glued together, or taken apart. Whatever kind of arrangement, they need to absorb the whole of what I feel, when I’m perceiving sound. The easiest way for me to explain that is that you have a CD, and the CD’s got music on it. But before you listen to that piece of music, and absorb it as a song, you have to hit open on the CD tray, there’s mechanical sounds that happily do that, you feel the disc, you might see a reflection of life from the disc from the sun coming through the window, you have to put it on the tray, you have to close the tray, you have to get the laser working, the motors spinning. You have to listen to that piece of music, and also depend with all the things that are on your mind that may or may not permeate to that piece of music. When I became cognizant to this, I can characterize it as some sort of allegory. Using music, using sound, using texture, I can characterize the whole situation that is listening—and still write music. I became really obsessed with that, obsessed with that idea that to me was a way to be really honest with myself about the way I perceive reality. Not just as a person, a person that kinda shares something idiosyncratic about my music. So when I do these things, it’s to really be like, “Hey, this is the way I see this.”

ZK: Is there a sort of sense of rediscovery with that?

DL: Yeah, every time it’s an interesting challenge to see what material here emerges as the main one. Like it seems like this one is encoded with history, with these ideas. This one’s really kind of a formalized historical idea, formalized through a touch of historical ideas, this song, this progression that I’m obsessed with is that, armature of the piece. This one’s really personal, this song’s about this lyrical thing, that I can decorate those lyrics and stack all them and texture them along the edges with this idea about sound. It’s endless for me. My favorite synthesizer is me. Once I flatten all these ideas and make them even, make them equitable to each other, whether an idea, or a sound, or a piece of music, or a progression, or a feeling, when all these things are equal, and given credence to be musical weapons, then I can make cool stuff endlessly.

ZK: With Garden of Delete there seems to be a lot of themes of one’s adolescence but without that general nostalgia that people feel when talking about growing up. Do you think nostalgia is productive?

DL: I think it depends on the context, but generally I don’t, I kind of shy away from it, shy away from that word. Because to me nostalgia is a feeling that the past is somehow intrinsically better than the present. And to me that’s unfair. It seems to me as escapist as being really into the future, there’s really no difference, but these rounds of desire for something other than what you are, what you have. That bums me out. The part that I like about it is that those can be the future and the past, being equal; they’re both staging areas for all this speculation. And that’s not so far away from what I love about science fiction, or fantasy, or any of these things that are speculative arts. These are staging areas for your imagination to really reconfigure history and reconfigure philosophy, or reconfigure anything, really.

ZK: There’s definitely a sort of tonal shift lately between Interstellar or Destiny or The Martian, where aspects of science fiction are sort of renewing their optimism, that there are mounting problems but there are people that can still beat them.

DL: Maybe that’s just because we got so burnt out on cyberpunk or something. Which was already kinda ripe with issues. But yeah, optimism needs to be there, you have to be optimistic about yourself, you have to be optimistic about the idiosyncratic potential of whatever it is you’re doing, to share yourself and be as earnest about it as possible, is what I always what I enjoy in entertainment. When I’m just getting something that is custom-tailored from a person who decided to really listen to themselves and to share, I find that I’m mostly drawn to that. These macro-level ideas about things like: Is the future doomed? Is the future great? I don’t care. I’m more interested in what any individual person can tell me through those ideas about themselves as a human being, today.

here’s another day where I go out and play my inane fucking noise to an audience of Soundgarden fans

ZK: It’s very easy to romanticize your own past because you had a different sense of scale of the universe back then.

DL: At least on this record what it was to kind of go back and exhume the crypt of my adolescence, the stuff that stuck with me, speaking with memories and gender and DNA. The traumatic stuff emerged right away, the rest of it … didn’t. So things that I pushed away or didn’t mean to think about for awhile, were like looking at pictures of myself, or even reading my notes, my journal. These weren’t very unique things; in fact I noticed how generic I was. My concerns were generic, my overwhelming obsession with being liked or wanted, or specifically liked a girl that I’d get obsessed with, or my unrelenting naivete, this eagerness I had to be in the world, and that I wasn’t in the world. The world would kinda be around the bend once I was free, and all these very loaded cliches.

ZK: Do you find it a frustrating notion that one’s past is at direct odds with one’s future?

DL: Of course. I think so. It’s tricky. I would imagine that if I didn’t have a project that’s around those ideas, if I was just casually obsessing over it, it would be mega-maniacal and negative. It would be like, “Get a grip dude.” Now you’re this person, you’re this more visible, older version of this other thing, and that’s what you are. You’ve aged, you have things you need to do and accomplish on a daily basis to do them. The only reason it was even interesting to me is that I found myself on this tour with these bands that I had idolized when I was a kid. In a position where I was going to be on this amphitheater tour with Nine Inch Nails and Soundgarden. And by the way, I’m driving to make every sound check every day at 5:30, through the American midwest. You just have a lot of time to think of how you got to that point. You can make the point in the present and the point in the past, with that, and you start filling in the rest with your imagination every day, driving for hours and hours. By the time I got off the tour, I had created this very vague map of terrifying memories. We were listening to (XM hard-rock stations) Ozzy’s Boneyard and Lithium on the rides, we were almost giving ourselves a soundtrack to the whole thing. We were immersing ourselves in the feeling to get ourselves jacked up.

ZK: That must be quite surreal. Touring around with people who were your heroes. That’s a bit of the dream, isn’t it?

DL: Yeah, you can’t fathom it. And after awhile too, you adapt. You adapt to the initial shock. This amphitheater looks exactly like the last one except stage right and stage left is way more narrow. And here’s another day where I go out and play my inane fucking noise to an audience of Soundgarden fans. That’s a very specific scenario that quickly sobers you. This has a certain continuity that starts to emerge. More awkward than awesome. But you know, it was incredible, one of those highlights of my life.

ZK: Hey, if you achieve that sort of thing, achieve those moments, you can be proud of them.

DL: It’s the sort of thing of like everyone thinks that modesty and humility are always the way to go. And it’s so funny, because it’s almost like you didactically decided to take away all of the pleasure of these things that happen in your life, just because you think that it’s a nicer way to be, or something. Just be real with it. You have to recognize the awesome that has been served to you, and it has fucking seasons. There’s gonna be a lot of lows too, you gotta enjoy those highs.

ZK: If you can’t really appreciate the moments you’ve worked for, the moment you deserve, then why drag yourself through everything else.

DL: Yeah, you’re kind of doomed.

I just want someone to hand me the fucking gun, and be like, “You have to destroy all of this shit.”

ZK: If only you could live like videogames. Videogames rarely have any humility whatsoever. It’s all just action and agency.

DL: It’s funny with videogames, I never feel good when I beat them. I just feel relief. Sometimes I think about videogames and I get extremely bummed out, I get really obsessed with sports games. I’ll get into like the typical binge scenario with like Madden or NBA where it’s just like hours and hours of building up this thing, and I’ve won championships, lost them, done all of these things, it’s the year 2025, or later. I just kind of wake up and this is the most unsatisfying game in the world. I’m doing all this shit and there’s nothing at the end of the rainbow but another year of simulation.

ZK: With the popularity of all these livestreaming game services, on one hand it’s easy to scoff at them, on the other, it’s like, dude, you used to fantasize about people watching play Mario Kart.

DL: I know, like you wanted so badly to show your friends. I dunno, I think I’m playing games the wrong way. I’ll listen to podcasts about games, I hear a lot of people say their major grievances are really long games, these huge campaigns. People are just so burnt out, they just wanna play a short game. Even if it’s kinda on rails, they just want the experience. And the only satisfying gaming start to finish recently was Call of Duty, which I didn’t even like. I thought it was so corny. But I’m getting incrementally better at this, it’s getting harder but I can deal, and it’s gonna end—I can see the end.

ZK: Yeah, I loved the last Fallout or Skyrim, but to be honest, I didn’t beat them. There’s so much there, and I’m very ADD about these things sometimes, and at the same time kind of a stubborn completionist along the way. So if you keep giving me these sidequests, it’s hard for me to say no, hard for me to soldier on.

DL: Yeah, you’re gonna do them. On one hand, it’s nice that all these companies are like, okay, we’re gonna be really generous and give you all of this stuff, but on the other hand they just want to advertise that this has X amount of hours in this game. That’s all they want.

ZK: And most of those hours are you walking around and nothing’s happening. Which is nice but…

DL: Yeah, it’s just numbing after awhile. I tried to play Last of Us, which is obviously the most hyped about game, and I’m late to every game. I just got a PS4 in the summer. Even though everyone was like so over it. Okay, this is a classic PS4 game, here we go: I played for like two hours or something and I just don’t care, I don’t wanna kill these zombies. I don’t wanna do anything. It’s so not fun. I don’t like the story, I don’t like the melodrama. I just want someone to hand me the fucking gun, and be like, “You have to destroy all of this shit.” The best game I’ve played in a long time was Wolfenstein. Old Blood I beat, it was fucking so satisfying. I loved every minute of it. It’s like just the games that I like are always the ones that on IGN get good but not great reviews. Those are my favorite games. If there’s a 9.2 I’m out, I don’t want it. Obviously you guys love it because it’s so epic and such a feat of programming, but I’ll just stick to give me a gun, and let me run through this game.

ZK: When that last Batman game came out and everyone was giving it like nines out of tens, I really struggled to imagine how this Batman game could be one of the most sublime experiences.

DL: It’s Batman! It can’t be. It’s fucking Batman. No matter what it is, it’s never gonna be as good as a movie. Another thing about Batman, which I like but bothered me, was that I always feel blind, which makes me feel so weird. Like are they fucking with me, because it’s Batman, a fucking bat that can see at night? Because I can’t see anything. I don’t know what is around me. Maybe I’m not good at turning on the infrared or something at the right moment. My internal compass feels so damaged in that game. I can’t deal.

ZK: Okay, I feel like this is one of those banal, but necessary questions. You have music that’s inspired by games, what would you say is the most influential game music to you?

DL: I have to say that it was probably Metroid, just because I think that the amount of hours put into that game, its music became burned into my memory. And also the music was really strange and creepy and beautiful. And I love that. I do love the Metroid music. I love that music so much.

NES itself had the most purely creepy stuff going on, probably because the games were so raw, so simple

ZK: Nintendo are magicians in the whole sound design aspect, but they were going for such different sorts of feelings there than usual. Nintendo doesn’t really do spooky and isolated and claustrophobic, but then there’s just this one game.

DL: I think Nintendo became even more kind of saccharine in their later platforms. And Metroid was always their wolf, their intensity zone. I would say NES itself had the most purely creepy stuff going on, probably because the games were so raw, so simple in a way that even in a way where when they were trying to be sweet they ended up weird. There’s a thing where you had to figure it out, that always made it feel a little strange.

ZK: There’s something eerie and off-putting about a basic computer trying to speak to you.

DL: It’s super weird. There’s also those little intercenter challenges in Contra where you have to duck and shoot forward, and the music was good in that. There was a lot of Nintendo games that were creepy. I’m don’t know about later on, I’m sure the N64 they had their branding and everything was down pat, but Nintendo itself was really weird. Like the second Mario freaked me out.

ZK: What was it about the second Mario that freaked you out?

DL: Besides the obvious (reason), of them just porting some other fucking weird-ass game over to Mario, and just sticking Mario characters in it, that fucking egg, the end of the level and the eagle’s mouth opened and that fucking egg comes out or whatever.

ZK: It’s amazing as kids we all figured that out. Like it’s not a key, that’s not a door, but…

DL: I know! It was just creepy. Not part of your life. Unless you read a lot of fantasy books or if you play tabletop RPGs or something, your brain’s a little more calibrated to ideas about creatures and fantastical things. But if you think about it, that’s a really weird way to conduct your adolescent life.

//

Photo of Oneohetrix Point Never via Grantb88 on Wikipedia Commons

Photo of Oneohetrix Point Never, live on stage, via WFMU Radio on Flickr

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers