Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 190

November 24, 2015

Welcome to the adolescence of AI

Artificial intelligence does not have the cuddliest of reputations. It is either coming for your livelihood or, if movies are to be believed, your life.

Google, however, has unearthed a new problem: Its AI is too friendly—much, much too friendly.

In early November, the advertising (and search, and web) giant introduced “Smart Reply,” a feature in its Inbox app that could automatically reply to basic emails. “Machine learning is used to scan emails and understand if they need replying to or not, before creating three response options,” Wired’s James Temperton explained. He continued: “An email asking about vacation plans, for example, could be replied to with “No plans yet”, “I just sent them to you” or “I’m working on them”.” Or at least that was the theory.

In a blog post last week, Greg Corrado, a senior research scientist at Google, noted that “Smart Reply” was all too willing to respond with “I love you.” As he put it:

As adorable as this sounds, it wasn’t really what we were hoping for. Some analysis revealed that the system was doing exactly what we’d trained it to do, generate likely responses — and it turns out that responses like “Thanks”, “Sounds good”, and “I love you” are super common — so the system would lean on them as a safe bet if it was unsure. Normalizing the likelihood of a candidate reply by some measure of that response’s prior probability forced the model to predict responses that were not just highly likely, but also had high affinity to the original message. This made for a less lovey, but far more useful, email assistant.

This is a technology problem, but it is really a human problem. The most common way for artificial intelligence to become smarter is by emulating human behavior. As Buzzfeed’s Mat Honan documented through parrot-centric chicanery, M, Facebook’s personal assistant is currently largely powered by human contractors. “Before Facebook can make its robot act like lots of humans,” he concluded, “it needs a lot of humans to act like robots.” Similarly, Google’s machine learning taught “Smart Reply” to react to messages like a human does, which, in a vacuum, means saying “I love you.”

If AI is growing towards human knowledge, the “Smart Reply” snafu suggests that it is somewhere in its adolescence, maybe a few weeks before its Bar Mitzvah. And like most teenagers, AI says “I love you” too early and too often. It’s a phase most people grow out of, albeit with slightly less difficulty than passing the Turing Test. So maybe there is hope for your nephew and AI—not necessarily in that order.

Alternately, have you considered responding to every email with “I love you”? Should you do so, and write it up as a piece of low-stakes gonzo journalism, please share said piece.

Go back in time to save time in the adorable Tick Tock Isle

Described as a spiritual successor to the delightful Cat Poke, Tick Tock Isle is a point and click adventure game that doesn’t want to reinvent the wheel—and it’ll charm the pants out of anyone who thinks that wheel is outdated or boring.

The demo was originally released four years ago by the duo of Jason Boyer and Ryan Pietz. “We spent an entire summer designing our biggest game yet,” Boyer writes on his blog. “Unfortunately, we didn’t have anyone to program it beyond a demo, so it lingered in our unfulfilled dreams folder.” Finally in April 2015, they decided to “make our dream a reality and began programming the game ourselves in secret.”

It’s only befitting that their game about time is also a portal to the creators’ own past—while also taking place in the future. The mess of timelines interweaving in both the game proper and its own creation results, ironically, in a kind of timelessness. Called to a mysterious island by a mysterious phone call, the protagonist, a clock repairmen, arrives on a stormy night. The person who summoned him is nowhere to be found, but a massive, rusted old clock in the attic is what appears to be the problem. Upon fixing it, the protagonist leaves the house only to find himself in the not so distant past, before the mysterious island was left to abandoned to decay. By coming to understand the family who lived on the island and neglected to take care of the clock, you also come to understand why you were brought there to fix it.

more than just a nostalgia dump

Know for their nostalgic aesthetic and good natured comical stylings, Jason and Ryan’s work will make you smile even when you’re stuck on a particularly frustrating object puzzle. There are several call backs to classic mechanics like some simple platforming and Double Fine-esque puzzling. But Tick Tock Isle is more than just a nostalgia dump. Above all else, it’s sincere, recalling to a time in games before the need for grittiness for grittiness’ sake; a time when arriving on an island on a stormy night didn’t mean you’d find some horrible world in either the sky or beneath the ocean. Tick Tock Isle returns players to an era before Braid made designers think even their most adorable games required an undercurrent of depression in order to be taken seriously. Without sacrificing story, it manages to remain upbeat even while it explores the ravages of time.

You can play the demo or buy the full game for Windows.

Mini Metro makes mass transportation sublime

I don’t remember much from Jeen-Shang Lin’s Soil Mechanics class. Beyond a vague inkling of his whiteboard doodles and that time he paused mid-lecture to remark on my unexpected presence, most of it remains a formula-laden blur. Except for the one time he mentioned Pittsburgh’s North Shore Connector project. I can still recall his perplexed laugh. “Pittsburgh has some beautiful bridges,” or something like that, he said. “The people know how to build them, how to fix them … so why the hell did they decide to dig a tunnel underneath the Alleghany?” A shrug. More laughter. Then back to talking about datums and pore water pressure.

Mini Metro doesn’t ask you to decide between digging tunnels and building bridges. There are no budgets to balance or construction contracts to negotiate. Pittsburgh’s late 2000s light rail extension connecting the North Shore to downtown ballooned from an original price tag of $200 million to over $500 by the time it was completed. Various politicians fingered it as a prime example of gratuitous pork barrel spending while local residents found it preferable to no extension at all. In Mini Metro, the politics are much simpler—no one cares much what you do as long as you keep commuter wait times down.

no one cares much what you do as long as you keep commuter wait times down

As a result, the byzantine compromises of other urban simulators are replaced by a series of straightforward trade-offs. Based around supply and demand, Mini Metro simply invites you to develop a network of routes and trains with limited resources in order to get people wherever they’re going. Connect an existing square to a newly minted circle, and people from those two locations, in the form of various shapes, will be able to travel back and forth. Next, a diamond might appear, and then another circle, until eventually your city is bustling with symbols waiting impatiently at one station or another as you try optimize the number of lines and cars in search of an ever elusive equilibrium.

But while a peaceful balance is always evading the player, the game’s design never loses sight of it. Minimalist throughout, Metro City’s interface has been folded into the game proper to make them virtually indistinguishable. For that reason, building out your public transportation system is like playing with a beautiful subway map, one that prizes simplicity and elegance above all else. The game’s paramount achievement is the ease with which it transforms an acutely distilled spreadsheet of complicating variables into a constantly evolving map that’s intuitive without sacrificing complexity.

As stations swell and overcrowding becomes the norm, choices must be made. Do you connect three circles in a row in order to create the shortest route, despite the redundancy? Should you increase the efficiency of a station with multiple transfers, or decentralize them altogether to avoid having multiple trains dump all their passengers at the same station? At the end of every week, recorded by a small face clock in the upper right hand corner next to an abbreviation for what day it is, players get a new train and the choice of one potential upgrade, ranging from an entirely new color-coded line to more bridges.

These gifts come with a sigh of relief, but the peace of mind they bring is short-lived. By mid-week the scramble begins again, with an array of intersecting and overlapping routes that feels even more mangled than before. They are always knots of the player’s making, however, and unraveling them more closely approximates the anticipation of untying a birthday bow than the frustration of trying to sort out a wet shoelace.

the game seeks to avoid the anxious hustle of a traditional simulation

This difference can be traced directly back to the game’s fusion of interface and aesthetics. Mini Metro’s style of interaction, strings you can tug on and stretch, trains you can pick up and drop, makes the flat, two-tone depictions of cities like Cairo and Montreal feel aggressively tactile. Over the course of developing each transportation network, the contradictions of travel and their imperfect solutions are given a unique texture. The game doesn’t just show you the inefficiencies of your ad hoc development; it lets you feel them as well.

By linking these interactive aesthetics to a simulation kept sleek by its frugality, Mini Metro gives rise to a meditative experience that’s more serene and efficient than any existing transportation system. Many management games like to bombard the player with numbers and calculations. They wear their robust simulations on their sleeves like badges of programmatic honor. They reduce the player to a manipulator of menus, tasked with calibrating the spreadsheets running under the hood rather than asked to participate in the magic they produce. Just another cog in the game’s machine.

But Mini Metro submerges its formulae to create a space for more organic play. Like a city that leaves its streets to pedestrians, pushing highways underground and elevating trains overhead, the game seeks to avoid the anxious hustle of a traditional simulation by reducing clutter and keeping things at a more intimate, human level.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The Dismal Western Front of The Grizzled

The First World War is often referred to as The Great War, due to its immense scope, as it incited all the world’s national powers and resulted in a devastating death toll. Set within this war is the tabletop game The Grizzled, which makes no attempt to capture such scale, and instead hones in on a small squad of French soldiers whose camaraderie is their greatest chance for survival. In this, The Grizzled prompts comparison to Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, which describes the war through a concise and emotional narrative. The story follows the young Paul Bäumer and his squad of fellow volunteers of the German Empire. Like players in The Grizzled, Bäumer only manages to survive the war’s dangers by the love of his comrades and their distant hope for peace.

Like the novel it evokes, The Grizzled is a brief and straightforward experience. Each game is comprised of Missions in which players overcome Trial cards that are placed in the center of the playing field, known as No Man’s Land. Doing so activates Threats, and when No Man’s Land contains three identical Threats, the Mission is failed. It’s a cooperative game of “press your luck” in which players must safely empty their hand of Trials or withdraw to the cover of the trenches in order to succeed the Mission. Peace is ultimately achieved if the squad can overcome the deck of Trial cards before their collective Morale is depleted. This, like Remarque’s tale, establishes a harrowing tightrope walk done in tandem—as failure and success are collective fates.

The wartime horrors confronting Bäumer are rarely actualized as enemy soldiers. Instead of people, he is pitted against deadly devices and circumstances set forth by the machine of war. Due to their unrelenting breadth, these monstrosities create an inescapable environment of terror. For soldiers, the war is a world unto itself—a place where civility is foregone for animalistic survival. Of course, the decrees of politicians and the iron sights of marksmen are behind such evils, but Bäumer’s fragility cannot comprehend their humanity—and so he concedes, “We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation. It is not against men that we fling our bombs, what do we know of men in this moment when Death with hands and helmets is hunting us down.”

Threats in The Grizzled are characteristics of a similar milieu—battles of survival rather than head-to-head conflict. The game features no depictions of enemy soldiers brandishing bayonets. Instead, Threats are incorporeal in their origin, and break through grim skies with callous inevitability. Between these tumults there are restless days at the Front whose quietude force soldiers to wallow in their stark circumstances. Bäumer’s demons swell in such moments, “Night again. We are deadened by the strain—a deadly tension that scrapes along one’s spine like a gapped knife.” The Grizzled finds its rhythm in this sense of impatient anxiety, through which players crawl towards peace and risk safety in the frantic sprint towards victory.

Bäumer only manages to survive the war’s dangers by the love of his comrades

The Grizzled further captures this volatile setting with the illustrations of Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac—one of the many cartoonists and journalists tragically killed during the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January of 2015. In addition to his satirical illustrations for the fearless Charlie Hebdo magazine, much of Tignous’ career was motivated by activism. He belonged to Cartooning for Peace, an organization whose work promotes the education and awareness of topics such as women’s rights and censorship. Tignous also illustrated for the French affiliates of the World Wildlife Foundation and Clowns Without Borders. During a eulogy at her late husband’s funeral, Chloe Verlhac showed her belief in the importance of his work and praised cartoonists as “messengers of hope.”

In Tignous’ depiction of the First World War, this hope is one encumbered by colors of rust and rainy earth that all melt together and create a static mess of scenery. He paints the inescapability articulated by Remarque, “Everything is fluid and dissolved, the earth one dripping, soaked, oily mass in which lie the yellow pools with red spiral streams of blood and into which the dead, wounded, and survivors slowly sink down.” Those survivors, the Grizzled themselves, embody a grey reluctance with sapped shoulders and tired eyes. The game’s instruction booklet features a special thank you to Tignous, which characterizes him as a dear friend to the game’s creators. Readers are left with the words “Hasta Siempre Tignous,” a faithful phrase that suggests his work will be everlasting.

In addition to Threats such as frigid snow and mustard gas, which hinder all players equally, The Grizzled challenges players with Hard Knocks. These Trials capture the psychological horrors of war by forcing individual players to act irrationally, as they are overcome by frenzy and phobia. Such traumas take place on the periphery of Bäumer’s tale, like a toxic tide that washes through and floods the trenches, sweeping its victims elsewhere while leaving survivors muddy but still fit to fight. The violence that remains is in watching these stresses develop and linger before a helpless Bäumer: “One of the recruits has a fit. I have been watching him for a long time, grinding his teeth and opening and shutting his fists.” It is in coherence with these words that Hard Knocks are festering wounds, which must be dealt with collectively.

Amid such mental desolation, Bäumer’s only true comfort is the solace of his fellow soldiers. Even while lost in No Man’s Land, the mere sound of his comrades, familiar noises cutting through a wasteland, have the ability to lift him up above isolation. Amid despair, they prove to be invigorating— “They are more to me than life, these voices, they are more than motherliness and more than fear; they are the strongest, most comforting thing there is anywhere: they are the voices of my comrades.” Here too, in the words of companions, players of The Grizzled find some reprieve. Players may support one another through the difficulties of Hard Knocks, but they are unable to mend their own wounds. This interdependence is what drives The Grizzled, as the game grinds to an isolating halt when the team fails to communicate.

Bäumer and his squad mates, like those in The Grizzled, trudge through these motions of war like those confined to a chain gang—enslaved and bound to ill-fated neighbors. Their story isn’t one of particularly remarkable heroism, navigated by catastrophe or skill. They are not written into the forefront of iconic battles, nor are they described with great marksmanship or fortitude. Bäumer and his friends are vulnerable captives—“We are little flames poorly sheltered by frail walls against the storms of dissolution and madness, in which we flicker and sometimes almost go out… Our only comfort is the steady breathing of our comrades asleep, and thus we wait for the morning.” And so they do what little they can, clinging to one another for safety in the hope that chance will see them through.

the game grinds to an isolating halt when the team fails to communicate

This sense of hope through camaraderie is that of orphans bound by abandonment. It is not only that these soldiers are lost in a horrifying situation; it is also that they have no home to which they may return. Upon taking a brief leave, Bäumer has difficulty reconnecting with his family and hometown. As if they have betrayed him, or he betrayed them, there is a palpable discomfort in their reunion. His family members only fill him with sorrow, his neighbors fill him with contempt. He sleeps in his childhood bedroom as if a ghost, held within familiar walls but unable to feel anything at all. By the end of his stay, he regrets ever leaving the Front, for it has destroyed any wild dreams he held for normalcy after peace. Bäumer is alive, and so the war has not yet taken his future. Perhaps worse, he suffers the wretched fate of having been robbed of his past.

Among the solemn visual art of The Grizzled are two group portraits, which encapsulate such sentiments of irrevocably tainted innocence. At first glance these illustrations appear to show one squad of soldiers separated by long years of war. But peering through their veils of cigarettes and scruff chins, one finds mere children no older then when depicted with bright eyes in overalls and news caps. Bäumer laments this loss after watching his first friend killed by the war, “Iron Youth. Youth! We are none of us more than twenty years old. But young? Youth? That is long ago. We are old folk.” Like him, those in The Grizzled are broken kids—clutching to boots and rifles as though they are nostalgic dolls or baby blankets emitting motherly pheromones. They are no tougher or wiser than the day they left their families at the train station back home. Still children, but children turned grey as they are devoid of life’s color, sticking together in spite of it all.

November 23, 2015

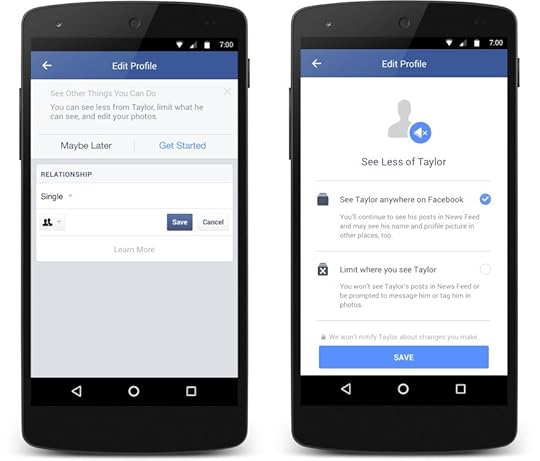

Facebook’s looking to streamline your next breakup

I started dating when MSN Messenger was still a thing and started breaking up in the era of Facebook, which was a good system right up until the moment that it wasn’t. That last comment is probably a fair description of all relationships. Social media did not create the awkwardness of breakups, but it did lengthen the gauntlet through which the newly single must run, and running is hard when all you want to do is stay in bed with Netflix and a tub of ice cream.

Facebook has apparently decided to do something about this 21st century problem. In a blog post published last Thursday, Facebook product manager Kelly Winters explained, “we are testing tools to help people manage how they interact with their former partners on Facebook after a relationship has ended.” To that end, Facebook users who exit relationships will be offered tools that will allow them to see less of their ex, ensure that former flames see fewer of their posts, and un-tag photos of the formerly-happy couple. “We hope these tools will help people end relationships on Facebook with greater ease, comfort and sense of control,” Winters writes.

Many moons, dates, and Facebook product updates ago, I parted ways with my partner of two-and-a-half years by mutual assent. “David is no longer in a relationship,” suddenly appeared in the newsfeeds of hundreds of putative friends. The only thing I remember about the evening in question is that one friend, whose connection with me remains something of a mystery, replied “Awwww, you two were like peanut butter and jelly.” Thanks, I guess?

The advertisers would rather you not be too miserable to log on.

What does one say in reply to such a comment? It is, on the one hand, the platonic ideal of a Facebook comment: brief, positive, and anodyne to the point of being impersonal. In any other context, it would be perfect. But thirty minutes after breaking up, it grates. This problem can either be solved by rooting out specific situations that are at odds with the ideal Facebook comment or by changing the definition of a good Facebook comment.

Is it any wonder that Facebook chose the former option? Better to weed out the occasional moment of incongruity than to change the platform’s entire tone. This act of kindness, like all acts of kindness, can quickly become oppressive. There will now be fewer reminders of your pain sandwiched between uplifting videos and ads. Don’t forget the ads. That is ultimately what this is all about. The advertisers would rather you not be too miserable to log on. They’ll still sell you dating services, naturally, but they don’t want you feeling too down. This may be a fair price to pay for not having to see your ex’s face for a little while, but it is unmistakably a transaction.

Facebook’s new breakup tools are but the latest case in which the company’s products have awkwardly intersected with its vision of wall-to-wall positivity. A little over a year ago, Facebook rolled out “year in review” videos in which a series of pictures from the previous year were compiled alongside cheerful graphics and music. Like everything else, this was a good system right up until the moment that it wasn’t. The most obvious shortcoming of this system was identified by Eric Meyer, who logged in to Facebook one day and was treated to a “Year in Review” ad featuring a picture of his daughter who had passed away during the year. Meyer came up with a term for this sort of technological mishap: Inadvertent algorithmic cruelty. He wrote:

And I know, of course, that this is not a deliberate assault. This inadvertent algorithmic cruelty is the result of code that works in the overwhelming majority of cases, reminding people of the awesomeness of their years, showing them selfies at a party or whale spouts from sailing boats or the marina outside their vacation house. …

To show me Rebecca’s face and say “Here’s what your year looked like!” is jarring. It feels wrong, and coming from an actual person, it would be wrong. Coming from code, it’s just unfortunate. These are hard, hard problems. It isn’t easy to programmatically figure out if a picture has a ton of Likes because it’s hilarious, astounding, or heartbreaking.

So once again, we have the question of whether you tweak the product or the broader context. If the default unit of a network is positivity, if engagement normally equals positivity, this sort of awkwardness will always live at the edges. The chosen solution, with breakup tools or with Facebook’s promise to Meyer that they would do better, is to fix some of those edge cases. This is a laudable goal, but you can’t hold back a flood with your fingers. As with nuclear war or a breakup, the solution to this sort of technological problem is a sort of détente in which a certain amount of negativity is allowed to permeate the social network’s bubble. Moments of sadness are only calamitous outliers because they are constructed as such.

Yet change to the underlying context remains largely off the table. Instead, we’re in for round after round of fixes around the edges, each of which highlights the edge cases that go comparatively unaddressed. Breakup tools are nice, but are they really more important than more powerful tools to deal with abuse? Perhaps not, but they may well be more monetizable. In this respect, the various attempts to smooth out a social network’s edges are often the clearest indications of where its central priorities lie.

The terror of a videogame made to look like a silent film

There’s no guessing as to where Letter To A Friend gets its look. The grey, flickering lights; the darkness heavy and consuming as miasma; everything out-of-focus, fuzzed and grainy as if seen through an old, dying lens. The creator needn’t say that its “visual references come from expressionistic silent movies and old analog recordings” for us to know that is the case. It’s a staggering recreation that speaks for itself.

Or rather, it doesn’t speak at all, and that’s part of what makes it so creepy. Everything from the frail shutter speed to the exposed scratches, dust, and hair that makes early film reel so easily identifiable has been simulated. Typically, this look is used by filmmakers as visual shorthand for something old-fashioned, easily dating the footage at around the early 20th century (it’s also used especially in ghost stories when explaining the origins of the disturbed, typically Victorian-era spirit). That may be the case in Letter To A Friend but the aesthetic is used more to achieve an unsettling sense of terror more than anything else. This is the same light and color tones that Nosferatu lurched up the stairs to the bedroom in that iconic horror film moment.

The narrative of Letter To A Friend is set-up as if a memory of a night once spooked. We are reliving a nighttime visit at a train station, something the character we inhabit does regularly, presumably after work or similar affair. But on this night there was a haunt. We are made uneasy from the start as the silent film recreation inhibits our sight as well as our sound. The dark is noticeably more impenetrable than it would be if we had clear vision. Look across the train tracks and you can make out no outlines or even the slightest of lights; only more pure darkness. A train passes right at the beginning without the loud sound we’d expect, clattering over the rails. The ubiquitous muted buzz we are left with instead lets us know that hearing won’t be an aid either. We are vulnerable to anything lurking in the dark that may creep up on us.

It is everything we dread.

What the game does from there is, at first, brilliantly disturbing. A silhouetted figure ambles silently under the light cones of streetlamps in a car park. We don’t know who they are. No one else is around and we are forced to wait for a train. Next, we see a faint dark figure move slowly across a lit window in a large building on the other side of the train tracks. This really is Nosferatu. Finally, they appear on the train platform itself, appearing as a menacing silhouette. It is everything we dread. Their stillness leaves us in suspense. What are they going to do now that they are so close to us?

What works here is that suspense. The figure is ambiguous, uncanny, and otherworldly. Where it all falls apart is when, right at the end, the dark figure is seen up close and its mystery is replaced with goofiness. Another slight slip-up is a lack of stringency. While the intertitles that tell the story provide appropriate segmentation for each part of the night, you are left wandering too long, aimlessly, trying to activate the next title. If it were snappier the gradual terror of the experience would be so much more effective.

Still, for a game made in a matter of hours as part of the Asylum Jam it’s an accomplished proof-of-concept. And no degree of failure in other parts of the game are able to let down the anxiousness present in its silent film aesthetic. Hopefully it isn’t left unexplored from here but is either expanded or used in horror games to a similar effect. It deserves that much.

Why Paper?

Support print media in the modern world by backing us on Kickstarter

If you want a sense of the difference between the worlds of paper media and videogames, color is the best place to start.

In print, as we learn in kindergarten, there are three primary colors—red, blue, and yellow—and you get all the other colors by mixing them together. If you pay attention to the color cartridge in your printer, you’ll see blue and red are “cyan” and “magenta,” but otherwise it’s the same.

This color palette, often referred to as CMYK for cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black), is the subtractive color model, and it’s the opposite of how TV and computer monitors work. Subtractive color starts with a white page and adds ink to reduce the light reflected to a specific desired color. Screens, on the other hand, start with a black, unlit surface and add light to produce color. This requires a different set of primary colors—red, green, and blue, often abbreviated as RGB.

All of this creates constant headaches for print designers who today almost universally have to translate the work they create on a computer screen (in RGB additive color) into the language of CMYK subtractive color for the final physical product. It’s almost certainly much less of an issue for game designers, creating on screens, for screens.

So given all this, why in the world should anyone be interested in a videogame and culture site relaunching its printed magazine? Isn’t that like trying to push games back onto cartridges in a world of digital downloads? I mean, physicality is so 1990, right? You might as well take a cue from Magritte and paint a Super Mario World box: Ceci n’est pas une pipe? Ceci n’est pas un jeu vidéo.

There is always something lost in the process of translation, and to be clear, the movement from play to language is a translation even more substantial than moving an image between additive and subtractive color. No publication will ever replace putting a tablet or controller into someone else’s hands and saying you have to try this. But if there’s a loss inherent in translation, in talking about a thing in a different medium with different tools, there’s the possibility that something may be gained as well.

A work in a new language may result in a new reader, a new context, a new discussion with a new set of ideas. An image of a Magritte painting on a screen takes a conversation about image and representation and places it in the middle of the reality of (post-)mechanical reproduction. Magritte via Benjamin via. . . Warhol? Jameson? Sontag? Or are all of these already painfully, unendurably out of date?

Games move fast. Software, measured in individual titles, is obsolete in a year. (The year-end best-of list is an obituary.) Planned obsolescence for consoles is generally as long as five or six years, mobile devices less than two. The online news cycle feeds on previews and pre-release reviews. By the time the game exists, it’s already over.

It leaves artifacts that can be forgotten, collect dust, and still be rediscovered.

And this is what the translation to paper has to offer—time. Paper is an old thing. It requires time to prepare. It leaves artifacts that can be forgotten, collect dust, and still be rediscovered.

Images on a screen are recreated between 60 and 120 times per second. They are retrievable as long as a disc is readable, or as long as a server is maintained. Many computers no longer bother to include optical drives; when was the last time you even saw a floppy disc?

I own a run of an undergraduate literary magazine extending back to 1966. I am one of probably a dozen people in the world who care, but you can read it if you would like. I would be happy to put it into your hands—here, you have to see this.

Videogames deserve an alternative to obsolescence driven by marketing cycles and an endless procession of newer, shiner screens. They deserve a chance to grow old and still speak to us, in languages beyond nostalgia. This is why paper, even now, especially now. The page will never, can never replace the screen. It can only ever be a translation, a thing to be seen in different colors. Something slightly new, perhaps, and, with luck, still a thing for some time to come.

///

CMYK/RGB Image created by Hana Khalyleh

Header image via JLS Photography – Alaska

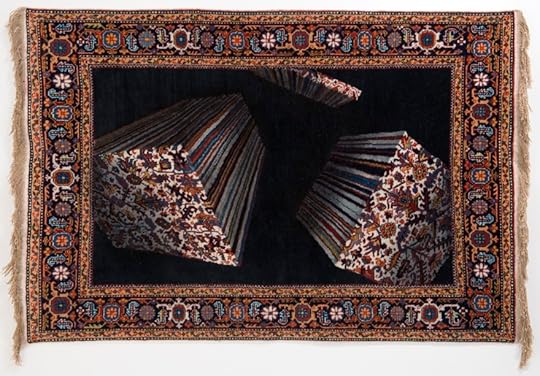

Sculptor turns Azerbaijani rugs into sublime glitch art

If patterns are a language, as artist Faig Ahmed describes them, then his trippy redesigns of traditional Azerbaijani rugs are a dramatic rearticulation.

One of his woven carpets stretches like a VHS error midway down and melts onto the floor in a pool of swirling colors. Another rug hangs half-pixelated, the intricate patterns visible on one side minimized into thick squares on the other. Several others feature an untouched, ornate border around a void of floating cubes, or spherical protrusions behind a sunken field, or a spiral cone bursting through the medallion; a modern brand of psychedelic framed by an ancient craft.

Ahmed’s stunning abstractions of classic textiles merge what he refers to as a long-running human tradition with a seemingly glitch-inspired aesthetic. Rugs within rugs within rugs. Rugs warped out of shape, bleeding neon, fragmenting into patterns new and unfamiliar to the established vocabulary.

Several of Ahmed’s works are featured in Crafted: Objects in Flux, an exhibit dedicated to new methods and materials of contemporary craft.

Find out more about Faig Ahmed and his glitch rugs on his website.

League of Legends and the problem of online communities

If you liked what you read, why not back us on Kickstarter?

Early last Friday, just before the opening remarks of “Tribeca Games Presents: The Craft and Creative of League of Legends,” I sat next to a young man named Will, who told me he had come all the way from Daytona Beach, Florida. I asked him if it was a business trip; this was the first time Riot and Tribeca Games had ever put on an event like this. There were maybe a little over a hundred people present; it’s not the sort of thing I would expect fans to pilgrimage over. “No,” he said. He seemed shy about it. “I just didn’t get a chance to go to Blizzcon this year. So, I figured I should make it out to this.”

The events are hardly comparable, though. “The Craft and Creative of League of Legends” is focused more on the design and art side of games. Many of the attendees work in the gaming industry, or aspire to. It’s this second group that Will falls into, I learn. “Do you want to be a designer, or an artist?” I ask. Will is noncommittal—he doesn’t know what he wants to do. He just knows where he wants to do it.

A busy-looking dude stops in front of us mid-stride. “Is that your homemade poro?” he asks, pointing down at the stuffed animal sitting atop Will’s bag. (Poros are little horned puffballs in League of Legends, sort of a cross between a goat and a cotton ball.) Will perks right up.

Riot prefers to talk about their “community”

The guy is from Riot, the company that makes the game we were all here to talk about. “Wow, this is awesome,” the guy says, tweaking the horns. Will mentions that he’s actually sent two of the stuffed animals to Riot HQ, in Los Angeles. He then pulls out a card, Hallmark-style but with the Riot Games logo printed on the front, a fist punching viewer-wards. It’s a thank-you card, for all of Riot. Will’s got a stack that he means to hand out to every Rioter he sees.

This one takes it gracefully. He thanks Will, shakes our hands, and leaves to do whatever he needs to do, which is probably a lot.

This is the sort of dedication that Riot, who has only released one game—albeit a very, very popular one—inspires in fans, even if the company itself would avoid calling them that. Riot prefers to talk about their “community,” who they never miss an opportunity to praise. The lounge, where there’s a break between each panel for attendees to get food and water, is also bedecked in fan art, with various interpretations of some of the 128 characters in League of Legends. The portion of the wall for concept art, made by Riot’s actual team, is maybe one fourth of the art on display, and it’s not clearly differentiated here.

NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 13: Shannon Berke, Evan Monteiro and Josh Singh speak at the Tribeca Games Presents The Craft And Creative Of League Of Legends on November 13, 2015 in New York City. (Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tribeca Games)

NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 13: Shannon Berke, Evan Monteiro and Josh Singh speak at the Tribeca Games Presents The Craft And Creative Of League Of Legends on November 13, 2015 in New York City. (Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tribeca Games)This is a weird stylistic choice. Riot has some truly tremendous talent working for them, as the first few panels of the day demonstrated. The first real panel after the opening remarks concerns the recent redesign of one of their older champions, a pirate sort named Gangplank. The panel, which featured a character artist, a game designer, a sound designer and one of Riot’s senior writers, discussed the creation of a complex history and motivation for Gangplank, along with new character art drawn from sources as diverse as 19th-century Russian realism. Being walked through that sophisticated process was, for me, the highlight of the day.

The low point, on the other hand, might be the “Sharing Player Stories” panel, a display of Riot’s self-congratulatory branded journalism. (Full disclosure: Kill Screen’s parent company Kill Screen Media Inc. has produced content for Riot, separate from my coverage of this event.) While the previous panels—the art demonstration, in which one of Riot’s 3D sculptors recreated the model for a champion live, on stage—peeled back Riot’s curtain and showed how the developers of the most popular game in the world, well, develop, “Sharing Player Stories” turned the focus off of Riot, previewing two films focused around fans of the game. “Love and League” follows several couples who play League of Legends together—that’s pretty much the elevator pitch. “Live/Play” focuses on League of Legenders with interesting stories, and gets a little closer to compelling material; one of its subjects, in the preview, describes being shot at during the Egyptian revolution of 2011, before returning to reinforce how much League of Legends de-stresses him.

A more frank discussion of these issues would have been a lot more interesting for me

After the previews, Riot’s film producers came out to talk about the films. Creative challenges mentioned here were always framed in positive ways; how could the filmmakers choose just a few stories, for example, from Riot’s global fanbase? This felt disingenuous, because while Riot surely loves their fans wholeheartedly, they’ve also spent an enormous amount of time and effort in recent years trying to improve the more toxic elements of the community. Take the Honor Initiative, whose explicitly stated purpose was to encourage more positive behavior. Take their new questionaire for players with inappropriate names, which uses questions lifted directly from the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. A more frank discussion of these issues would have been a lot more interesting for me, and I imagine for the rest of the League community as well.

The “Sharing Player Stories” panel was the second to last of the day. The last one, a musical demonstration of some of League of Legends’ orchestral loading screen music, was beginning soon, but the crowd already seemed smaller and drowsier than the high pitch of excitement from earlier. In between cosplayers in pastel wigs, I noticed Will, holding his homemade Poro in front of him like a dowsing rod. He looked a bit glassy-eyed. I wondered if his flight back to Daytona Beach would leave tomorrow, or whether he’d stay on, through the weekend, once he had run out of thank you cards to give out.

///

Lead Photo by Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Tribeca Games

Event Name: Tribeca Games Presents The Craft And Creative Of League Of Legends

How to make soccer more entertaining? Add ragdoll physics

Americans insist that soccer is and always will be boring. And, admittedly, low-scoring games with few opportunities for commercial breaks isn’t the most ‘Murica thing ever. But defenders of soccer might point to the simple elegance of a well-executed pass, or the unparalleled tension of a final battle in the penalty box.

Well, all of that—the good and the bad—gets thrown out the window in Footbrawl, a ragdoll soccer game being developed by designer Kevin Suckert. Right now, Footbrawl is just a basic prototype with lots of funny GIFs to show for it. But the potential seems, well, endless. “Its [sic] basically everything what FIFA street should be or what made PES2010 so good:” reads the devblog, “glitches and stupid Ragdoll Physics.”

As evidenced by the prototype, American football fans will feel at home in Footbrawl; the slow and deliberate grace of soccer replaced by needless head-on collisions and tackles. Aside from the constant group pummeling that comes with chasing the ball, the creator also says you can “pick up weapons and beat the shit out of your enemies.”

So, let’s say you’re running down the field, the ball miraculously staying with you as you sprint down dozens of yards before finally positioning yourself perfectly in front of the goal, all of a sudden you get wiped out by a plank of wood to the head. Sure, you could call for a red card. Sure, you could fight back. But no one will care and you’ll still be concussed and out a goal. You know, the American way.

“pick up weapons and beat the shit out of your enemies.”

I can’t speak to whether or not this violence improves on the art of soccer as a sport, but my inclination is that it’s a firm “no.” But on the other hand, watching characters make desperate runs for the ball only to get trampled by their own stiffened physics is priceless. Who’s faking injuries now, amiright?

Suckert says he’s working on a few arenas, ranging from a Brazilian favela to the “Ostseestadion” in Rostock, which he frequented often as a child. The main arena featured in the prototype, however, is a simple backyard where a group of young boys appear to be enjoying a quick game. The setting perfectly matches the awkward over exuberance of the ragdoll physics. But the youthful aesthetic also inadvertently layers in this theme of fun-filled childish banter, as you watch kid after kid fling themselves at goal posts and get pelted by soccer balls, all without a single concern for their own safety.

While the amateurish aesthetic matches the games mechanics, I can’t help but imagine how revolutionary it would be if these ragdoll physics were applied to a more established game like FIFA. I mean, how much money would you pay to see Neymar beating Lionel Messi by slamming into his body and clubbing him with a stick. Are you taking notes yet, EA?

You can stay up to date with the development of Footbrawl through its website and the creator’s Twitter.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers