Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 187

December 3, 2015

How do you follow up Bloodborne? Apparently, you don’t

The River of Blood, the Beast Cutter, the Surgery Altar, the Astral Clocktower, the Blood of Adeline, the Nightmare Church, the Underground Corpse Pile, the Holy Moonlight Sword, the Beasthunter Saif: the settings and armaments that furnish The Old Hunters will certainly sound familiar to veterans of Bloodborne. So too will its macabre menagerie: the Bloodlickers and the Parasites, the Winter Lanterns and the Nightmare Executioners. One can well imagine a brainstorming session at From Software, the developers trying to think gloomily as they thumb a dog-eared thesaurus. The Despairing Cutlass? The Infirmary of Sorrow? You half-expect to wander into the A Bit Crestfallen Caverns or pick up a rapier called Glum. They’d better leave Bloodborne alone after this expansion. They’re running out of synonyms for bad.

A sense of duplication looms over The Old Hunters. About midway through one confronts a troop of miniature bosses simply called the Living Failures, which could be the name of a good punk-rock band. These fellows are rangy and grayish and sort of drably nondescript, and in their number and manner seem conspicuously similar to the Celestial Mob fought previously in the Upper Cathedral Ward; they faff about in a garden rather than a shallow pool but attack alike and are contended with in much the same way. Though the resemblance may be deliberate. The Old Hunters takes place in a realm known as (what else?) the Hunter’s Nightmare. And the Hunter’s Nightmare, one gathers, is a kind of mirror image of Yharnam, the city in which Bloodborne proper takes place. Thus are its sundry ghouls and dreamscapes in fact reflections of the other side. The Living Failures are meant to be forgiven their plagiaristic aspect because it’s part of the game’s curious design.

In this way The Old Hunters feels less like an expansion than a reiteration. It begins in a negligibly remodeled Odeon Chapel, now ground zero of the Nightmare; from there one proceeds as usual through the Cathedral Ward, made over with verdant overgrowth and trees that slope and wend through the hills. This cloned environment has been populated with a handful of new enemies, true, whose styles and skillsets, especially early on, afford one a good deal of novel encounters. But even these feel mainly routine. Combat is still very much a matter of evading and parrying, swooping in and strafing away. And while nearly a dozen new weapons are introduced to your repertoire over the course of the game, only one, the Whirligig Saw, offers anything like a significant change. Bloodborne never particularly encouraged variety in arms—the blood stones needed to upgrade a weapon made it virtually impossible to enjoy the full use of more than one or two. The inclusion of so many here strikes me as nothing more than a concession to value.

Hidetaka Miyazaki’s most enduring idea was that videogames could stand to be rather more difficult. Bloodborne spiritedly advanced the cause: many of its ghastly enemies were occasion, for this player, for much hurling of the controller and gnashing of the teeth—though not at all unpleasantly. Miyazaki’s games are so capably, even elegantly designed that their demands on the player never quite seem unfair or unreasonable, no matter how outrageous; one naturally feels, as with a challenging novel, that their difficulty is conquerable. (The personal reward for all this rigor has been exhaustively chronicled elsewhere.) That The Old Hunters is grueling should hardly seem surprising. But the degree can’t be overstated. The Old Hunters is ludicrously, painfully, torturously difficult—so difficult that its (say) ten hours were stretched out for me to an exorbitant twenty-five, much of it spent repeating arduous grinding circuits. The press release included with my review copy recommends a character level of 65. Mine was a little over 90 when I trotted in—and I felt so far from prepared even then that I presume the press release’s author is either preternaturally talented or out of his mind.

Suddenly its difficulty no longer seemed conquerable

The first boss encountered in The Old Hunters is a heinous equine monstrosity called Ludwig the Accursed, though accursed in what way is anybody’s guess. Ludwig trots and whinnies grotesquely about a big cathedral room, whomping any moving target with ungainly hooves—a pretty ordinary Bloodborne foe, in other words. What you need to know about this Ludwig chap is that there’s a flailing corpse stationed right outside his chamber—one that yields five health-replenishing Blood Vials every time he’s chopped down. Ludwig is so bloody hard that the game is reduced to charity: accept this merciful gift, the game seems to say, since the boss certainly isn’t programmed to pity. For the first time in the nearly hundred hours I’d invested in Bloodborne I really did feel defeated. Suddenly its difficulty no longer seemed conquerable.

I bested Ludwig in the end, with the aid of a seasoned colleague willing, much to my relief, to lend a hand online. And with the cooperation of others I suffered through the following three boss battles too. (As a salve to those without online play, the designers have retrofitted the game with lamps at which A.I. hunters can be commissioned as partners, though in my brief experience they were so ineptly programmed that they could scarcely last five minutes in any kind of serious fight. One even got stuck against a wall straight away and stood unmoving as the enemy bore down on her.) It’s safe to say that I’ve had enough of Bloodborne—enough of Yharnam and the Hunter’s Nightmare, enough of blood echoes and quicksilver bullets, enough of grinding and more than enough of dying. Indeed I think I’d had enough before The Old Hunters started. The integrity of this game’s vision made it a seductively cohesive and concentrated thing, pure and unrefined. But perhaps that purity was already whole. More isn’t bad just for its faults and repetitions. It’s worse than that: Bloodborne was pure—and The Old Hunters dilutes it.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

December 2, 2015

New dark ambient album can only be listened to inside this virtual world

The advert lady on Spotify just told me that, as music is so easily available now through streaming services, it doesn’t matter what you’re listening to any longer but how you’re listening to it. This is Spotify’s attempt to boast that it’s setup to let you listen to music how best suits you. You might be lounging in a boutique, jogging with earphones in, or dancing around your kitchen while cooking tea. Spotify has you covered, apparently. Yawn. There’s more to listening to music than convenience, isn’t there, Spotify? You go to a concert in a large hall with hundreds of people to listen to a band play for the specific experience that cultivates; the sweat, the enthusiasm, the vibrations of the music created live right in front of you passing through your body.

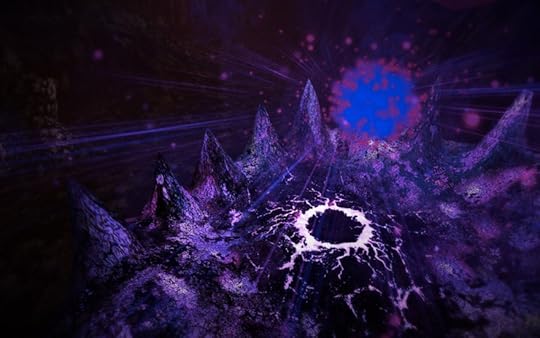

The construct of the concert space seems to be at the heart of the latest album by Argentinian drone music project Termotank. However, this space is virtual rather than physical, having you move slowly through a doomscape where dark mountainous spires serrate the moonlit sky like fangs. This is the only way to experience the album. Don’t ignore the significance of this limited setting. Termotank has a Bandcamp page where its other albums can be listened to. But this latest one, called Fernweh3D, isn’t available there. Termotank also plays festivals around Argentina and Latin America but Fernweh3D isn’t there, either. You have to download a file and enter a 3D virtual world, exploring the dark alien crags to discover the specific location of each track, signified by a fiery orb floating in mystical wonder.

The reason why Termotank has decided to deliver its new album like this is apparent when you’re in there. All of the spaces in Fernweh3D are designed specifically to fit the song they’re married to. Often you’ll see some form of entrance so that the approach becomes part of the eventual listening procedure. One song location is preceded by rocks carved as if welcoming pillars with purple flames dancing atop. Another has a transparent yet veiny bridge to cross before reaching a jaw of rock. A personal favorite has you almost get lost in a cluster of large needle-like stalagmites (without the necessary cave) where a green orb rests in a circular clearing at the center.

extraterrestrial ambient composition oozing out.

You get to these places and you stand there, listening. If you venture outside of a certain circumference of the orb then the music fades away. And so, stuck in these confines, it becomes natural, at least for me, to see how you can frame the visuals to fit the extraterrestrial ambient composition oozing out. The 3D world around you is primed for it. Theatrical clouds of smoky gas hang in the troposphere while in the distance sits a postcard-worthy sight of a glowing moon resting eerily behind a peak. Add to that the orbiting rock formations and gnarled trees and you get a scene that begs for a camera’s frame.

My impression is that Fernweh3D comes in this format so you can invent a spatial connection with the music. We do this with all music: Erykah Badu’s New Amerykah Part Two will forever be my university dorm, and practically every Sikth song is the stained hardfloor of my teenage self’s local mosh pit. But Termotank has engineered it so that this memoried location is the same for all listeners of these new tracks. The title of the album further suggests that Termotank wants us to become intimate and perhaps fond of this virtual world. According to the PDF that accompanies the album, “Fernweh” is a German word that means “being homesick for a place you’ve never been.” Whether that’s true or not matters less than what Termotank believes it to mean.

You can download Fernweh3D on its website, Game Jolt, and itch.io.

Pick up the strangest call of your life in this videogame labyrinth

You come to, upright, in the middle of a room swirling with color. Quickly, you realize the stripped wallpaper isn’t actually moving. It’s you, swiveling your head around, trying to figure out where and who you are—how you got to this ugly room in the first place. The neon walls overwhelm, but not nearly as much as the number of doors surrounding you.

Uncertain but too afraid to stand still in this ugly room, you walk through a door.

But in this place, you will discover, only ugly rooms lie beyond the doors that lead into even more ugly rooms. In the center of each one is a lonely red phone booth. When it starts ringing, you jump to pick it up. But instead of a voice, you hear a dial tone as the ringing continues. With no buttons to press, you can only sit and listen to the melody between the dial tone. Or you can hang up.

You hang up, the ringing never ceasing.

No matter how many rooms you go into or how many phones you pick up, it persists. Like the sound of a school bell, the noise immediately inspires an all-consuming anxiety inside you. Someone is reaching out—someone is trying to make contact. But you cannot be reached. Again and again, the dial tone signals your failure to pick up.

Finally, you notice that when you turn a certain way, the ringing gets louder. You must only listen well enough in order to find the true caller. After at last picking up the correct phone, the voice on the other side sounds like salvation.

the ringing sends a wave of panic through you.

He calls himself Dudley. He’s pretty sure you’ve both been imprisoned in this god forsaken labyrinth by a man named Ogilvy and his “attack on common sense.” As Dudley calmly explains, several pieces of evidence have led him to the conclusion that you are in a never ending virtual reality simulation. For one, there’s an obvious lack of fidelity to the reality you currently reside in, two, a glance down at your feet will reveal that your feet have been mysteriously “misplaced.”

Every now and again, Dudley will cut your conversation short, forcing you to go back into the maze to look for a needle in a haystack (or the real phone among a dozen virtual copies). Each time, the ringing sends a wave of panic through you. Slowly, you come to realize that what panics you most isn’t actually the high-pitched sound itself, but rather the notion that it would stop. That Dudley would give up or go silent. That you would be left here, without explanation or purpose.

///

Call of Dudley is an entry into PROCJAM, a game jam that hopes to make procedural generation more accessible to both players and creators alike. Like the moment in Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide, Call of Dudley appears to equate the relationship between a player/creator and the game to the act of picking up a phone. As in the The Beginner’s Guide, you are left clinging to the receiver, trying to make out the voice on the other end—but it sounds too faint. It doesn’t matter anyway, though, whether or not you can hear. All you really wanted was to know that you could pick up—that someone would be on the other end. That someone was reaching out, trying to communicate.

As in both the The Beginner’s Guide and the likes of A Clockwork Orange, you can’t trust anyone in Call of Dudley. Neither the narrator, the world, nor even the medium itself is reliable. Narrative is inherently a pack of lies. Videogame realities are inherently broken. You stand upon a foundation built like a house of cards and magic tricks. The mediated message you cling onto the phone to hear will crackle and cut short unexpectedly. It will crash into the void.

As the player, all you can do is go down with it.

You can play Call of Dudley on PC, Mac, and Linus for free here.

Stunning art exhibit reminds us that nature cannot truly be replicated

A video of a landscape: trees dance as what might be wind sings. The sound becomes more intense, revealing itself to not be wind but rain, though the image does not at first reflect it. It carries on, and as the branches move, they blur, as if they were never video but rather paint that has not dried and cannot withstand the added water. It shifts from photographic clarity to an impressionistic style that mirrors Monet, then further still, until the once crystal clear image is just a series of abstract colors.

to explore the tension between the real and abstract

Such is the exhibit “Pleasant Places” by London-based artist Quayola, which seeks to explore the tension between the real and abstract; bringing attention to the role of technology in modern art, paying homage to Vincent Van Gogh. After visitors to the exhibit experience the trees in front of them fading into abstraction, the video switches to a “behind the scenes” glance; the video is removed, and all that’s seen is the overlay that creates the blur on top of a black background, then just static spots of color like fairy lights on a black and white version.

The exhibit simultaneously draws viewers into a nature scene while pulling back the metaphorical curtains; it immerses us just long enough to shatter our feelings of serenity, and in doing so, reminds us that nothing artificial can entirely replace the natural world.

Find out and see more of Pleasant Places on Quayola’s website.

Grimes’ Art Angels obliterates pop culture

We like to talk about games in the context of all art and culture. If you agree, consider backing our Kickstarter!

///

Grimes destroys the male gaze. And the female gaze. If you will, the human gaze. Can’t stare right at her or you’re blinded, petrified. So Art Angels invites you to stare around the bubble, the distortion, the separation of you from her, it, self from self. It is sound and color through a cracked screen, a ghost in the machine, the machine Dance Dance Revolution, the ghost the soul of that girl who is always dancing on the machine, her body inseparable from the spirit trapped on the other side of the plastics; the sound of a remix as the point of genesis for the original composition, the new art, an angel with a face like a facsimile.

On cheesy, breezy, Carly Rae Jepsen-y “California,” Grimes says up-front, “This music makes me cry.” It might make the Grimes fan cry, too, if they were expecting the Grimes of the dark, cohesive nerd-pop of Visions. Grimes tells us on Art Angels that she is not just that Grimes. Nor is she just this one. She, like every other person, is other. She is foreign, alien, inscrutable. She presents a vapidity and asks you to prove that it is vapid. You can not. She throws out some hip or cool moment and what the hell does “hip” or “cool” even mean. Art Angels offers a welcoming veneer of accessibility, then riddles it with subversion. Your parasocial notion that you know Grimes or can categorize Grimes, she tells it to fuck off. She precedes “California” with a violin jig. She follows it with a Boredoms-esque electro-mosher. She constantly assures you that you do not know her, you presumptuous ass-hat (I’m talking to myself here).

Grimes is foreign, alien, inscrutable

Meanwhile, her album challenges your value judgments. What is good or bad? Shouldn’t this thing be more thought out, produced with more focus, more carefully sequenced, less eclectic? Shit, “Belly of the Beat” has spry acoustic guitar strumming over a drum machine…is that not, somehow, like, wrong? Grimes shakes her head. She is cycling through her playlists, through your playlists, aggregating moments, glitching them out. She is scratched-up compilation CDs of ’90s pop hits playing on your PS4 and, congratulations, your PS4 is now sentient, inspired, and has a new album it wants to share with you. It’s called Art Angels. It sounds like “Steal My Sunshine,” skipping.

In Spike Jonze’s film Her an “artificially” intelligent OS asks Joaquin Phoenix’s character a few pointed questions, reading him as he responds, and then generates a persona that can sublimate his social dysfunction into a working relationship. The OS calls herself Samantha. One of the ways that Samantha’s self broadens is through creativity, and this she displays in several ways, one of which being musical composition–and, as always, she plays off the disposition of her owner and the film’s creator, Jonze himself, so: simple, stately piano melodies or precious indie-folk ditties, ghost-written by the Arcade Fire, probably. And the more the creativity and self expands, the more Samantha refuses to be owned. In conclusion: Art Angels sounds like the music made by Justin Bieber’s OS, ’bout halfway before it’s about to phoenix off into transcendence. God, what a wonderful, horrible world.

“Kill V. Maim” blenders J-pop, cheerleading, the best bridge ever, a low-key chorus where Grimes says, brilliantly, that she’s “only a man,” and a coda with a ridiculous synth line that aesthetically amounts to Grimes reminiscing about clubbing in Berlin in 1987, you know, before she was born. Time is a flat circle. A compact disc. Again, scratched the fuck up. Grimes is DJing the discs while wearing a Virtual Boy. So everything around her is red and black, a color-coded binary. How do you critique this? Like Samantha from Her, Grimes sees all your critical perception and discernment and has already rearranged and edited and remixed it, sending it off for publication. How do you review playing a game when the game is playing you? More fundamentally, how do you say or think anything about a creation that is about its inspirations and the hardwired joy of its own unfiltered process? To create is divine. Here are our Art Angels. It’s a hot mess blessing, a seraphim kiss like a live coal to the lips. The iniquity of our tongue is purged. We don’t have to talk about this record any more. We don’t have to look at any artist like we know them. We have no claim. And the game plays on, insatiable. Give thanks. After all, “REALiTi,” er, reality is a construct. A funky, goofy, messy construct…and beautiful, too.

Now I’m gazing at all the things I could pretend Grimes to be: the angel, the nymph, the siren, the fairy, the demure Lolita, the Medusa, the object, the iconoclast, the icon, the diva, the pop culture succubus, the OS incarnate. They are all just bodies, shells, a pile of empty forms from which Grimes rises slowly, clad nakedly in everything that she loves (Mariah Carey, Renaissance music, Chrono Trigger, etc.), a glittering coat of colors that’s vulnerability is its admission that you are allowed to try (and fail) to look at the invisible, the substance of a person, by looking at the things that that person adores and then adore them with her. I see Grimes smiling. Or, at least, I think it’s a smile. Hard to tell beneath all that dark blood, running from her mouth. The bodies fall away, I can see now they’re her kills. And as they roll off onto the black-light carpet, I see that Grimes is dancing, forever, on a glowing four-square.

In The Pedestrian, it’s the signs that’ll do the walking

The genericized male figure has escaped his perch on the bathroom sign and soon his female counterpart in the gender binary shall do the same. That’s not bad as a political statement, but how does it fare as a game?

The Pedestrian, which developers Skookum Arts have slated for a mid-2016 release, turns this timely premise into an adventure game. The male figure is not running off, Man of La Mancha-style, to break down the gender binary; no, he’s out to rescue the object of his affections, the female bathroom figure. He travels the only way he knows how: through signs. The Pedestrian’s navigation-based puzzles take place in the built world, but its character can only move through signage. The player repositions signs, draws on them, and directs the male symbol so he can reach his goal. Each of these signs becomes a discrete puzzle, and they all add up to a quasi-sidescroller suspended on the walls of a building.

It’s all pretty meta. The Pedestrian is, after all, a game about wayfinding that takes place within wayfinding implements. It does, however, make a good deal of sense to proceed from the assumption that signage systems have inner lives. A sign that can’t decide where it points or what it means—a fate that is annoyingly common—is effectively experiencing an existential crisis. The Pedestrian literalizes that scenario. The signage in this world needs to figure itself out, and until it does it won’t be handing out advice.

You can keep track of The Pedestrian during its development on its website.

Just Cause 3 is a long day of kicking over sand castles

Help us cover the art of destruction in games by backing our Kickstarter!

///

Here’s a really enjoyable thing you can do in Avalanche Studios’ Just Cause 3: fly a fighter plane over the rolling green hills, white sand beaches, and turquoise waters of Medici. Spot a military base and strafe it with chaingun and missiles until the enemy scrambles helicopters. Jump out of the plane, skydive level with the helicopter, grapple over to it, and hijack it in mid air. Steer it on a course toward the center of the base and jump out just before it hits the ground. Within minutes, player character Rico Rodriguez will have acrobatically annihilated a sprawling facility. The explosions, it’s important to mention, will look fantastic.

///

There’s a purity to Just Cause 3 that comes, in large part, from its unwillingness to fully characterize its protagonist. The game begins with a credits sequence, Torre Florim’s mellow psych-rock cover of The Prodigy’s Firestarter playing over clips of Rico (sporting the thick beard and denim-on-denim of a rural Ontarian) surfing warheads and cracking wise with the rebel leaders he’ll meet when the story begins. Over the next few hours, the player is introduced to their mission—remove dictator General Di Ravello from the fictional Mediterranean nation of Medici. They learn how to use a combination of grappling hook, instantly-deployable parachute, and wingsuit to zip across the landscape. They’re taught how to set waypoints on the map that point out the next Di Ravello base to blow up or occupied town to liberate. But, they will not learn much of anything about Rico—aside from how to fling his body across the landscape or how well he can shoot rockets at fuel canisters.

There’s a purity to Just Cause 3 that comes from its unwillingness to characterize its protagonist

For a while, this is fine. Just Cause 3 is largely disinterested in being anything more than an excuse to destroy things. Its plot seems almost purposefully thin, a light action comedy stretched like saran wrap over dozens of hours. Its characters are archetypes (The Best Friend; The Scientist; The Tech-Savvy Mercenary; The Bloodthirsty Mercenary; The Evil Dictator). Its hero is a vessel for action defined solely by his love of contextual one-liners and unflagging determination to reduce every piece of military architecture or technology he comes across into scrap. Every narrative element is made as simple as possible in order to minimize distractions from what the game is most interested in offering: destruction.

///

Here’s another really enjoyable thing you can do in Just Cause 3: fly a fighter plane just above the forested mountains of Medici. Spot a military base and strafe it with chaingun and missiles until the enemy scrambles helicopters. Jump out of the plane, skydive level with the helicopter, grapple over to it, and hijack it mid air. Steer it on a course toward the center of the base and jump out just before it hits the ground. Within minutes, Rico will have acrobatically annihilated a sprawling facility. The explosions, it’s important to mention, will look fantastic.

///

Breaking apart the infrastructure dotting Medici’s landscape is as satisfying as wiping a completed 5,000 piece jigsaw puzzle off a table or flicking a center piece out from a Jenga tower. Planting plastic explosives on a series of towers and flying away to watch them detonate in a lovingly rendered chain of fireballs and screaming steel scratches the same itch as unmaking any carefully-made object. The game’s developer understands the common, primal urge we all have to wreck things. They couple this with the knowledge that human beings love to watch fire do its work—that, as much pride as we take in building beautiful structures and complicated machines, we get a simpler and more immediate joy out of seeing careful work obliterated in moments.

In Just Cause 3, since the story isn’t enough to keep the player going, the urge to destroy has to pick up the slack. Luckily, Medici is absolutely lousy with things to annihilate. Di Ravello’s propaganda speakers, satellite dishes, and military bric-à-brac are always painted red and grey and, with time, this color combination attracts the eye like a magnet. The islands of Medici are rendered in great detail: the nation’s weather patterns and varied landscape encouraging the player to set down the controller to drink in the setting. But the player’s attention is solely focused on the garish industrial drab of destroyable objects. It’s almost impossible to travel from one mission marker to another without encountering airfield tarmacs bordered with electrical generators (when they blow up, sparks strike out of the wreckage like snakes), outposts with big water towers (great torrents of water splash downward, turning the flames to black smoke), or coastal towns marred by Di Ravello statues (which, if C4 is placed along the knees, buckle into beautiful clouds of stone and dust).

The player’s attention is solely focused on the garish industrial drab of destroyable objects

The player quickly learns that the story missions rarely offer anything more novel than the free-form destruction found in these towns—they’re as perfunctory as going into a base to wreck a power relay or driving a character down a road while they talk—so it isn’t long before more time is spent experimenting with Rico’s aerial acrobatics and leveling optional bases than actually moving the plot forward. The id-fulfilling pursuit of explosions is gripping for quite a while. It’s testament to Avalanche Studios’ talent that something as pedestrian (in videogame terms) as shooting a bullet into an oil drum remains exciting for more than a few minutes. Just the same, and like everything, the simplest satisfactions quickly turn into chores if novelty isn’t introduced.

///

Yet another really enjoyable thing you can do in Just Cause 3: fly a fighter plane over the snowy fields and pine-covered peaks of Medici’s volcanic ranges. Spot a military base and strafe it with chaingun and missiles until the enemy scrambles helicopters. Jump out of the plane, skydive level with the helicopter, grapple over to it, and hijack it mid air. Steer it on a course toward the center of the base and jump out just before it hits the ground. Within minutes, Rico will have acrobatically annihilated a sprawling facility. The explosions, it’s important to mention, will still look fantastic.

///

After a few hundred times, even the most fantastic version of blowing something up gets tiring. It’s an appealing action because it isn’t complicated, but the least complicated thrills become banal far more quickly than complex ones. Just Cause 3 is engaging because it gets the first half of this so fully. Its developers have obviously poured an enormous amount of artistry and attention into making little moments of chaos impressive enough that the player seeks them out so compulsively. The larger scope of Just Cause 3’s design doesn’t do justice to this work, though. Without compelling characters or inventive story missions, all that’s left to keep the audience entertained is destruction, repeated ad nauseum. There’s value in the small-scale satisfaction each explosion creates, but an empty feeling lingers after every plume of smoke has cleared.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Replicate the world’s most complex systems via emoji

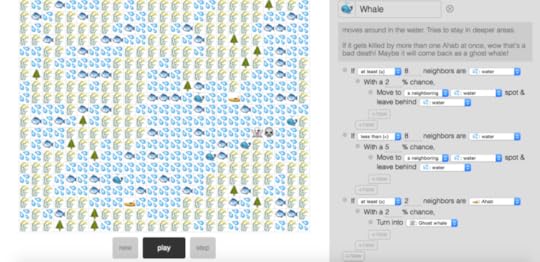

What if you could mod a game as seamlessly as playing it the way it was written? In Nicky Case’s latest simulation tool, A Simulation in Emoji, just that promise is fulfilled. In the introduction for A Simulation in Emoji, Case writes, “there is *no* difference between playing and making, between reading and writing.” This is because Case has given you, the player, all the tools already, to an endlessly customizable extent. But just what is being customized? A simulator for anything and everything—through emojis.

Case is no stranger to life-simulation tools. Case first made waves in 2014 with Coming Out Simulator, a self-described “half-true game about half-truths.” Later Case (and Vi Hart of YouTube fame) created the “playable post” Parable of the Polygons, which is actually less a game and more of an interactive lesson about diversity and how to navigate tricky unconscious bias. Case doesn’t falter when approaching tough, day-to-day subjects, and A Simulation in Emoji isn’t a stranger to this philosophy.

“There is no difference between playing and making.”

In his latest project’s description, Case expresses hope for players to create their very own Parable of the Polygons-esque explanations for the world. By using his free, infinitely customizable tool to represent essentially any complex system of the world—be it forest fires, global warming, animal extinction, racial bias, or anything else that can be portrayed via emojis—the possibilities are nearly endless. This leaves room for cleverness, such as Parable of the Polygons collaborator Vi Hart’s experiments with the new tool. Hart has created a cutesy snail simulator, in addition to a simulation of the effect of ‘ghost’ whales in the environment, thus truly showcasing the diverse topics, serious or not, one can experiment with using the tool.

In an interview with Kill Screen about recent release Neurotic Neurons, an interactive explanation about neurons and anxiety, Case described himself as being on the more “fuzzy side” of game design. In an explicit reference to Explorable Explanations, a project in the realm of text coupled with interactivity, Case said, “I can borrow the best bits of videogames, (learning-by-doing, emergent behavior design) but avoid the expectations and conventions of the medium (scores, fail states, a scruffy middle-age protagonist).” This can be said to also encompass the heart of A Simulation in Emoji as well, which transcends gaming for its own sake to become a useful, educational tool.

With the tools to create easy-to-digest experiences with a variety of topics, the player can help others understand a seemingly complex issue, all through the simple power of emojis. Or, you can just manipulate dozens of poop emojis to disappear across the grid by the power of sweeping toilet emojis. It’s your choice.

Create your own world simulations using A Simulation in Emojis, click here.

It’s time to take girl games seriously

If you think girl games matter, help us champion them in our magazine by backing our Kickstarter.

///

For generations of women, Judy Blume’s novels are a potent symbol. To the women that read her books in the ‘70s and ‘80s they were symbols of rebellion, offering knowledge that was forbidden by adults. “I knew reading it would be an act of revolt, but I wasn’t sure who I was revolting against,” said my friend Dayna Von Thaer, a young adult novelist, remembering the time that a sympathetic librarian sneaked her a copy of Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret in her early teenage years. For younger women like myself, Blume’s novels were conflated with becoming a woman after the stories had spent more than two decades of defining American puberty. We were handed Deenie and Forever by those women who had read them in secret, blushing and hiding the books at the back of our shelves. Their pastel covers were conspicuously dated, and we knew they were those “period books.” Although we did not have to deal with Blume’s widespread censorship, as previous generations of readers had, we still read her in secret—we didn’t want to broadcast the life changes that had become synonymous with reading Blume, but were hungry for the information within.

Judy Blume was the first adult to talk to us frankly about the struggles of adolescence—she was an adult who hadn’t forgotten what it meant to be a teenager. Regarding the title character from Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, Blume told Scholastic in an interview “Margaret was right from my own sixth grade experience. I wanted to tell the truth as I knew it.” Blume addressed a staggering number of themes of adolescence, ranging from male and female masturbation to teenage crises of faith, answering the questions that her readers had sent in hundreds of letters through stories that were clear and relatable.

The pop culture of girls has always been devalued or openly mocked

Yet despite the massive scope of her oeuvre, Blume is generally relegated to the canon of “girl books,” her novels disregarded in the mainstream since most of her protagonists are girls and young women. The pop culture of girls has always been devalued or openly mocked—think boy bands, teen dramas, and pink-glazed Barbie games—while the culture of boys is mainstream: would it be weird to see an article like this about Star Wars or Legos? Likewise, the male experience of adolescence is the one that children usually study. Holden Caulfield is the emblem of all adolescents, but despite the universality of her troubles Margaret Simon may only speak for girls.

Blume has been the defining voice on girlhood for the last forty-five years because she took teenage girls seriously. Blume legitimized teenagers’ problems and reassured her young female readers that they were normal. In Are You There God?, Margaret deals with her developing body, but she also struggles with her identity, her split-faith household leading her to question her religious beliefs and her sense of self. Female adolescence is about more than boys and periods, and Blume wrote true-to-life accounts to help girls and boys navigate that tumultuous period of life. Her novels are part of a canon of girlhood that is largely misunderstood by the rest of culture. But they initiated an important tradition of women using narrative to process their childhoods and adolescence by sending a whisper into the dark, simultaneously asking whether they are normal and assuring others that they are not alone.

In 1998, game developer Theresa Duncan said, “My stated goal in life is to make the most beautiful thing a seven-year old has ever seen.” Duncan’s beloved trilogy of ‘90s CD-ROM games are a digital heir to Blume’s legacy, celebrating girlhood and letting Duncan’s own memories shine through her young protagonists. Like Blume, Duncan never panders to her audience but rather offers them an interactive reflection of themselves. Her games starred and were made for inquisitive and adventurous little girls exploring every detail of the worlds where they lived. Chop Suey, Smarty, and Zero Zero gave girls characters that looked and thought like them in the same way that Blume’s Otherwise Known as Sheila the Great did. “Kids see a lot, and they’re wise and a little more complicated than most people give them credit for being,” Duncan said in a 1997 interview, echoing Blume’s respect and care for children.

The heirs to Blume’s legacy in gaming today are the women creating independent, autobiographical games with specific ties to their own girlhoods. These games are about reflecting on the joys and traumas of girlhood, or reappropriating an aesthetic associated with unimportant art to create artistic legitimacy for girlhood. “For me it’s about this call to women to say, ‘Let’s stand up for our memories, too,’” Rachel Weil said in a Skype interview. Weil is the creator of FEMICOM, an extensive project archiving so-called “girl games.” FEMICOM and many of Weil’s personal projects are grounded very firmly in bringing visibility to the “girl canon.” She creates pink and sparkly glitch and 8-bit art, and her games feature Hello Kitty. During our interview Weil recalled the gaps in the canon that created a great deal of confusion to reviewers when she released her game Electronic Sweet-N-Fun Fortune Teller, which was based heavily on the Tiger Beat quizzes that anyone who’s been a teenage girl in the last three decades knows well. Where Blume sought to legitimize the experiences of teenage girls, Weil seeks to secure girls’ media in the mainstream canon. “There are New York Times pieces about the work of Blume, those things that recapitulate and re-contextualize her work for an adult reader,” she said. “I think that’s something we sorely need for [girls’] games as well.”

Let’s stand up for our memories, too

Game designer (and former Kill Screen intern) Nina Freeman talked to me about how making games enabled her to process scenes from her adolescence. “I like to make games about things I feel unresolved about or have complicated issues with,” she said. Her games deal with her body and struggling for agency over it in various ways, a battle from their teenage years that has scarred many women. “When you grow up in a space where people and the media are telling you you should look a different way it makes you feel like you don’t have much control over yourself,” she said. “I think I felt disempowered because of that from a really young age.”

Nina’s games are a way for those who have exited girlhood to reclaim power and sort out those traumas of adolescence that were too confusing to manage in real-time. They function like a Judy Blume novel for adults still making sense of their teenage years, an answer to the question, “Am I normal?” that they are still asking years after adolescence has ended. Like Blume, Freeman was surprised that so many people had identified with her games, especially the number of strangers that had excitedly admitted to mashing their naked dolls together as children, as players do in her game How Do You Do It? “This wasn’t even my goal for these games, but they helped people feel a little more open about these kinds of things,” she said.

The experiences of girls and young women are not niche

In her novel Yes, Please, Amy Poehler writes, “If you ever want to see heaven, watch a bunch of young girls play. They are all sweat and skinned knees. Energy and open faces.” The gendered, patriarchal marketing machine churning out weirdly sexualized dolls profits by creating a false binary—if boys and girls must have dramatically different toys and clothes, then that’s twice the opportunity to sell. But girlhood is just as much about adventure as boyhood is—as a woman who spent hours upon hours of her childhood pretending she was Tom Sawyer, or gathering rocks in her backyard in her Pocahontas costume, I know. Women, and girls, deserve to be taken as seriously, and the canon of art by and for them does, too. The experiences of girls and young women are not niche. Many, many forms of media are beginning to turn to girlhood for their stories. In comics you have the much-beloved Lumberjanes, Nimona, the new Ms. Marvel and the recent series Paper Girls dedicated not only to empowering adolescent and pre-adolescent girls, but to giving a very mainstream account of girlhood read by women and men. Books like Coraline and the Fairyland series do the same.

Play is a natural part of all childhoods, and games have a unique opportunity to give girls agency through play. Despite mainstream progress in other mediums, most games dealing with young girls or girlhood are made by individuals or very small, independent teams—games like Slam City Oracles and Tampon Run, both made by women, in addition to the games discussed above. Society does not take women of any age seriously—this much is proven by the ongoing attempts to limit our reproductive rights and the constant devaluation of our time and skills in the form of workforce gender imbalances and wage gaps. Making girlhood mainstream and empowering the next generation of girls through their media and play is a bold and vital step towards true gender equality.

///

Header image by Jane Mai

December 1, 2015

Formula E will be the first racing championship with driverless cars

One of the charms of NASCAR, SB Nation word wizard Spencer Hall once argued, is that “You are watching for a non-fatal but spectacular crash.” Crashes are fun—and flammable—which is great up until the point you start to care about people. Therein lies the problem with racing. The distribution of interesting events is bipolar: either the humans tethered to machines do something brilliant or are on the verge of death. The baseline competence that would normally fill out the meaty part of a bell curve, while far more impressive than anything you could do, is fundamentally boring.

Fret not; Formula E is here to save the day—if by day, you mean the promise of entertainment with a minimum of human casualties. Starting next year, Wired reports, “ the series will see completely autonomous electric cars compete in one-hour races designed to test artificial intelligence.” The cars, which are currently in development, are supposed to reach close to 300km/h. As for what else they might do, the point of the exercise is to figure that out.

It is not just offline Rocket League (sadly)

This sort of racing, bonkers as it may occasionally seem, has practical value. It is not just offline Rocket League (sadly). Formula E CEO Alejandro Agag told Wired that Google, Uber, Continental, and Bosh were some of the companies he could see getting into this form of racing. Fair enough. As Clive Thompson noted in a September New York Times Magazine feature, Uber and Google are already engaged in a sort of race when it comes to self-driving cars, scooping up talent left right and centre in the hopes of getting a better product out sooner.

Formula E’s new series promises to be a more entertaining version of this metaphorical race, with some fun literal racing added to the mix. Moreover, because all of the technology is newfangled, the distribution of events should be more entertainingly bipolar. Failure is fun, achievement is fun and, just for now, baseline competence for driverless cars should be fun enough because it doubles as achievement. At some point, the excitement of baseline competence will fade as with the basic problem of NASCAR and Formula 1. But at least we’ll then have driverless cars?

That leaves us with one big question: How on earth will racing games adapt to the irrelevance of drivers.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers