Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 29

October 12, 2021

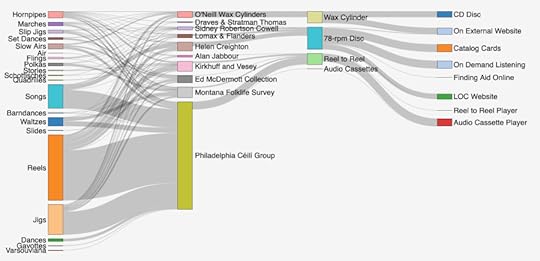

Review—Connections in Sound

Michael J. Kramer, “Review: Connections in Sound,” Reviews in Digital Humanities 2, 10 (2021).

October 10, 2021

Hitting a Nerve

From the Soviet film Appassionata (1963), Rudolf Kerer plays Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Sonata for Lenin (played by Boris Smirnov) and Gorky (played by Vladimir Yemelyanov).I can’t listen to music too often. It affects your nerves, makes you want to say stupid, nice things, and stroke the heads of people who could create such beauty in this vile hell. And now you mustn’t stroke any one’s head—you might get your hand bitten off.

Vladimir Lenin to Maxim Gorky

October 7, 2021

On the Fence

Still from Peter Bo Rappmund,Tectonics, US 2012, 60 min., digital video.

Still from Peter Bo Rappmund,Tectonics, US 2012, 60 min., digital video.At the northern end of Mexico, which is also the southern end of the United States, the real and the surreal meet to dance. So we see in Peter Bo Rappmund’s 2012 digital video Tectonics, a striking travelogue of life along through that region. Grass grows in the dust and trees bend in the wind. Corrugated metal creaks and towns are sliced in half by nation states. Nature mingles with the unnatural. Water laps the shore like the hem of a garment. Human settlements form colorful blocks of apartments and buildings. Motors hum. Radios blare. Silence sits above tire tracks on a dirt road, remnants of a chase. The sky is big and blue. Tiny bits of green and brown desert scrub cling to crevices and cracks. There are hardly any people, or if they appear they are overshadowed by the landscape.

Peter Bo Rappmund,Tectonics, US 2012, 60 min., digital video.In Commotion Dance Theater’s Tectonic Dances, presented at the Multi-use Community Cultural Center (MuCCC) as part of the Rochester Fringe Festival, the choreographer Ruben T. Ornelas along with dancers Nanako Horikawa Mandrino, Natalia Lisina, Alaina Olivieri, and Roy Wood bring bodies to this ghostly video. They do so, however, not merely to inhabit it. To be sure, at times the dancers become people, perhaps a refugee or immigrant hiding from the authorities, an ICE agent on the prowl or chase. In one moment, they take on the characteristics of animals: a horse, a bird. There is a lurking violence always threatening the dancers the more they creep toward the human.

Commotion Dance Theater rehearsing Ruben T. Ornelas’s Tectonic Dances.Just as often the dancers leave human figuration entirely behind to blend into the non-human world of the video. Limbs articulate as if almost to break the body itself up into component parts. The dancers echo, quote, imitate, and evoke the formal beauty of Rappmund’s images. Arms roll like the waves washing in against a pier in the Gulf of Mexico. Torsos lean and bend like trees in the wind-whipped desert. Bodies puff like clouds or move like rivers. They clutch to the sides of hills, flow over the ridges and peaks of mountains, root down into the earth, or tumble over like grains of sand.

And then there are the fences in Rappmund’s video. Fences, fences, and more fences. They are beautiful yet terrifying. They play with the light, creating texture and depth. They sparkle in the hot dryness that high-definition digital video is so good at capturing. They rust, creating hues that seem to blend into the desert. They moan and groan in the wind. They tilt and lean like modernist sculptures. They almost, but not quite, seem to fit. But the brutality of these structures is also ever-present. They interrupt and block, disturb and shut off. The dancers explore these qualities in their movements, often diverging into solos, uncomfortably touching and then ripping away from each other again.

Hovering between the embodied and the abstract, the representational and the purely formal, Commotion Dance Theater’s performers never quite come to rest in either mode. They dance at the border.

October 5, 2021

This Show of Ours

Michael Gandolfini as young Tony Soprano in The Many Saints of Newark.

Michael Gandolfini as young Tony Soprano in The Many Saints of Newark. David Chase’s prequel to The Sopranos is a surprisingly normal Mafia film. It even features Ray Liotta from Good Fellas fame, as if to say, look we are just like all the other Mafia films. Liotta turns in not one but two nice character portrayals in the film, but overall The Many Saints of Newark has little heavenly or goodly about it. The movie lacks almost all the weirdness that made The Sopranos so wonderful as a series. In particular, the movie does not emphasize the ways in which conventional American life might often lean uncomfortably closer to the abhorrent activities of American gangsters than most want to admit. That was one of many innovations and insights of the original series, yet it is little explored here.

Even the camera work and filming choices are different. While the camera often crept in for tight shots and crowded intimacy in The Sopranos, in The Many Saints of Newark everything is distanced. The film arrives in a sepia veneer of history instead of appearing way too close for comfort. This is a movie that wants to announce it is a historical epic rather than a show that kept leaping out of the television set (remember those) into everyday life during turn-of-the-twenty-first century America. Even the playful “prequelity” of the show—John Magaro’s spot-on interpretation of Stevie Van Zandt’s Silvio Dante, now as a young man; Livia Soprano’s miserable crankiness; young Paulie “Walnuts” Gualtieri already concerned about his clothes getting mussed up; Junior’s sociopathic streak; Janice’s stoner vibe; or having Christopher Moltisanti narrate the film from the grave—merely gives The Many Saints of Newark a nostalgic tinge instead of the dramatic immediacy of the original series.

That all said, there is one moment toward the very end of the new film that elevates it to Sopranos level. It comes through the acting of Michael Gandolfini, and it serves as both an homage to his late father and as a moment of the captivating quality of the original show. Sitting at the counter in Holsten’s Brookdale Confectionery, which was where the iconic last scene of The Sopranos was filmed and were Tony maybe (we’ll never know!) met his end, Michael Gandolfini waits for his uncle, Dickie Moltisanti (Christopher’s father and Tony’s sort-of-mentor), to meet him (his uncle never arrives). A milkshake is half empty before young Tony Soprano’s interlaced fingers. His football varsity letter jacket bunches up around his arms. Gandolfini bites his lip, hunches his shoulders forward, takes a deep breath, darts his eyes around. It’s an expression lifted straight from his father’s portrayal of the grown Tony Soprano, and it is thrilling acting. We sense Tony’s hulking mass to come in the future, his emerging sense of his need to assert his own place in the world, and his swirl of emotions—disappointment, sadness, resentment, rage, cold reasoning, determination, confusion.

This is the Tony we know. The facial expression and body language says this character is at once expecting someone to scold him (maybe Livia) and that he is leaving his adolescence behind. The acting almost singlehandedly connects past to future. Ruefully, in dread, we know, it will lead right back to a booth at that same restaurant. Gandolfini stands up quickly, then pauses at the door. Above the restaurant lettering on the glass, the camera zooms in. We gaze at his face in the doorway as the camera lingers, framing the intensity of his facial expression—the lip curled, the eyes shifting to the side, the sigh, the concentrated mix of emotions.

It’s a more subtle moment by miles than anything else in this oddly plain film. The camera pans back as Frank Sinatra sings “Whatever Happened to Christmas?” We see the bear-like silhouette of Tony—Michael, but almost also maybe is it James Gandolfini?—against the light streaming into Holsten’s. The figure hovers between son and father in a film all about a son seeking a father (and an acting son who lost his father, and is now playing his father when the father was his age). We watch Tony on the cusp of becoming what we know awaits him.

One only wishes that David Chase and the other makers of The Many Saints of Newark had started with a scene like this one and sustained the mood. Maybe then we could, once again, spend some time with this show of ours.

October 3, 2021

September 30, 2021

Rovings

Claude Viallat @ Document Gallery.SoundsThe Vanishing of Harry Pace, RadiolabA Charles Paris Mystery, BBC SoundsTakeover, BBC SoundsNaguib Mahfouz, The Cairo Trilogies (Dramatized), narrated by Omar SharifVarious Artists, Ork Records: New York, New YorkThe Charles River Valley Boys, Bluegrass and Old Timey MusicHank Bradley, The Pescadero BluesBob Dylan, Springtime in New York: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 16, 1980-1985Emerson String Quartet, Bartok: The String QuartetsVarious Artists, Music from the OzarksSteven Bernstein’s Millennial Territory Orchestra, Tinctures in Time (Community Music, Vol. 1)WordsAmy Kittelstrom, “The American Mind Is Dead, Long Live the American Mind,” Modern Intellectual History 18, 3 (September 2021)Julie Greene, “Rethinking the Boundaries of Class: Labor History and Theories of Class and Capitalism,” Labor 18, 2 (May 2021)Clyde W. Ford, Think Black: A MemoirTJ Clark, “Masters and Fools: On Velázquez,” London Review of Books, 23 September 2021David Masciotra, “Patti Smith and Male Bias in Music Criticism,” LA Review of Books, 14 March 2019

SNCC Digital Gateway

“Walls”Frida Kahlo: Timeless, Cleve Carney Museum of ArtAfterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art, Jewish MuseumPhyllida Barlow, Hauser & Wirth LondonRosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Swiss InstituteBruce Connor & Jay Defeo (“we are not what we seem”), Paula Cooper GalleryMoki Cherry Communicate, How?: Paintings and Tapestries, 1967 – 1980, Corbett vs. DempseyStockyard Institute: 25 Years of Art and Radical Pedagogy, Depaul Art MuseumJoan Mitchell, SFMoMA

Ibrahim Mahama: Lazarus,

White Cube Bermondsey

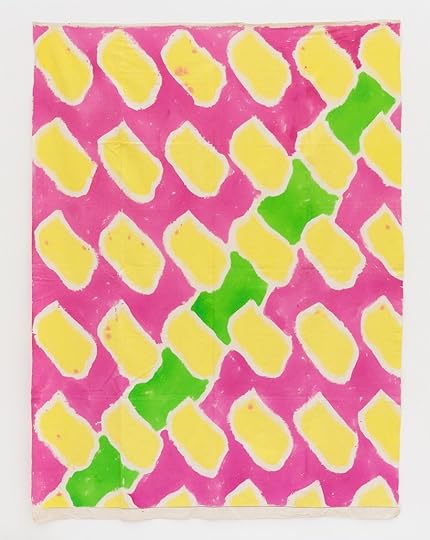

Claude Viallat

, Document GalleryTaryn Simon, The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection, Gagosian 976 Madison AvenueJonathan Muecke, Volume GalleryStagesCommotion Dance Theater, Techtonic Dances and Fairy Tales of Our Own Devising (a tryptych), Rochester Fringe Festival, MUCCDancing Out of The Dust, Rochester Fringe Festival, Rochester Contemporary Art Center Side LawnNique Content, The Consciousness, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineMoby Dick Bemshi!, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineDaystar/Rosalie Jones, No Home But the Heart: An Assembly of Memories, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineScreensBorgen, Seasons 01-03Dr. Paul Farber with Dr. Elizabeth Alexander, Monumental Conversations: What We Found When We Analyzed America’s Monuments, Mellon Foundation, 29 September 2021Ghosts of AtticaBetrayal at AtticaMcCartney 3, 2, 1Mayans M.C.

Claude Viallat @ Document Gallery.SoundsThe Vanishing of Harry Pace, RadiolabA Charles Paris Mystery, BBC SoundsTakeover, BBC SoundsNaguib Mahfouz, The Cairo Trilogies (Dramatized), narrated by Omar SharifVarious Artists, Ork Records: New York, New YorkThe Charles River Valley Boys, Bluegrass and Old Timey MusicHank Bradley, The Pescadero BluesBob Dylan, Springtime in New York: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 16, 1980-1985Emerson String Quartet, Bartok: The String QuartetsVarious Artists, Music from the OzarksSteven Bernstein’s Millennial Territory Orchestra, Tinctures in Time (Community Music, Vol. 1)WordsAmy Kittelstrom, “The American Mind Is Dead, Long Live the American Mind,” Modern Intellectual History 18, 3 (September 2021)Julie Greene, “Rethinking the Boundaries of Class: Labor History and Theories of Class and Capitalism,” Labor 18, 2 (May 2021)Clyde W. Ford, Think Black: A MemoirTJ Clark, “Masters and Fools: On Velázquez,” London Review of Books, 23 September 2021David Masciotra, “Patti Smith and Male Bias in Music Criticism,” LA Review of Books, 14 March 2019

SNCC Digital Gateway

“Walls”Frida Kahlo: Timeless, Cleve Carney Museum of ArtAfterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art, Jewish MuseumPhyllida Barlow, Hauser & Wirth LondonRosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Swiss InstituteBruce Connor & Jay Defeo (“we are not what we seem”), Paula Cooper GalleryMoki Cherry Communicate, How?: Paintings and Tapestries, 1967 – 1980, Corbett vs. DempseyStockyard Institute: 25 Years of Art and Radical Pedagogy, Depaul Art MuseumJoan Mitchell, SFMoMA

Ibrahim Mahama: Lazarus,

White Cube Bermondsey

Claude Viallat

, Document GalleryTaryn Simon, The Color of a Flea’s Eye: The Picture Collection, Gagosian 976 Madison AvenueJonathan Muecke, Volume GalleryStagesCommotion Dance Theater, Techtonic Dances and Fairy Tales of Our Own Devising (a tryptych), Rochester Fringe Festival, MUCCDancing Out of The Dust, Rochester Fringe Festival, Rochester Contemporary Art Center Side LawnNique Content, The Consciousness, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineMoby Dick Bemshi!, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineDaystar/Rosalie Jones, No Home But the Heart: An Assembly of Memories, Rochester Fringe Festival OnlineScreensBorgen, Seasons 01-03Dr. Paul Farber with Dr. Elizabeth Alexander, Monumental Conversations: What We Found When We Analyzed America’s Monuments, Mellon Foundation, 29 September 2021Ghosts of AtticaBetrayal at AtticaMcCartney 3, 2, 1Mayans M.C.

September 29, 2021

Travel the Spaceways

We are on as spaceship. It is also a space ship. It is also a shape ship. It is black as space, a wondrous zone of movement not so much celestial as intergalactic, beyond the heavens, out there, in the silent vacuum, where life began and to which, like black stars, we shall all return. There is something oddly grounding in the performance. Terrestrial is extra-terrestrial. Humanity is astronomical.

We humans have always glimpsed the stars afar to see ourselves up close, to get outside in order to get inside, to go to the edge of the universe only to discover that it was right here in our moving limbs all along. This is what Kyle Marshall and his collaborators—dancers Bree Breeden and Ariana Speight, sound designer Kwami Winfield, custume designer Malcolm-x Betts, lighting designer Amanda K. Ringger, makeup artist Edo Tastic, and film director Tatyana Tenebaum seem to be up to in STELLAR. Traveling the spaceways means always trying to come home. An odyssey is a circuitous route. It circles back. Indeed, in STELLAR, the circle establishes the line that loops back on itself, resolving where it starts again. Motion and emotion transmit ideas of order and freedom like radio waves emanating from finger tips, reaching the edge of touch, where the atmosphere meets the galaxy, and beyond it, so far far away that it comes right back down to the molten core in which our beings are forged, our entities are realized.

Marshall’s choreography travels the spaceways, a bit in the spirit of Sun Ra, in order to circumvent, to punch through to hypermode. Something has come unmoored, yet all is calm, steady. There is a kind of tensile force at work even in this dreamy gravity-less zone of the filmed dance.

Life itself gets coiled up in the movement, preserved, intensified. A kind of freedom emerges in this quietly intense, meditative performance. We get lost in space to find ourselves, we leave earthly problems behind yet out there, beyond the atmosphere, you don’t just float away. Instead, a kind of epic gyrational orientation surfaces with magnetizing implications. We watch people navigate, try out new moves in new spaces. They experiment. They dock. They connect. They depart. They clap for each other. They are close by at times. They journey light years apart. They are in touch, intimate, yet scalar, distant, at a magnitude. They gain mass, they seem to almost slow down as they speed up.

In Kyle Marshall’s “dance of speculative fiction,” the black marks on the costumes of Bree Breeden, Ariana Speight, and Marshall himself almost look like anarchy symbols. People spin on their own axes, pulled back to where they came from, finding each other circulating, achieving lift-off, loosening and tightening up, shedding weight and finding it again in the weightlessness, searching and finding and searching again, liberated in the infinitesimal, located in the vastness that become, for moments, no longer opposites.