Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 30

September 26, 2021

September 19, 2021

Contingency Plans

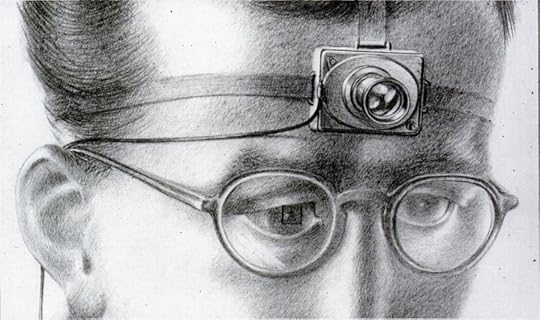

A man using the imagined “Memex machine,” from Vannevar Bush’s essay “As We May Think,” published in The Atlantic in July 1945.

A man using the imagined “Memex machine,” from Vannevar Bush’s essay “As We May Think,” published in The Atlantic in July 1945.X-posted from USIH Book Review.

As Abigail De Kosnik points out in her study of what she calls “rogue archives,” the Internet “began as a fantasy of the perfect archive, a technology that would preserve the vast record of human knowledge” (p. 44). Early futurists such as Vannevar Bush and JCR Licklider pictured an automated retrieval system, a kind of instant history machine.[1] A set of recent books grapple with whether this has become the case in the contemporary digital age. They draw upon the developing history of digital history itself to do so, and largely agree that digital technologies have turned out to be something very different from what Bush, Licklider, and other computer dreamers imagined. These recent books also diverge from the earliest explorations of digital history, which often took the form of how-to guides or manifestos (some were almost sales pitches for Silicon Valley). Instead, they adopt more reflective, scholarly responses to the transformations wrought by computers.[2] Taking topics such as mass digitization, networking, social media, data, the deeper logics of programming, and the history of digital history itself seriously, they offer a nascent intellectual history of how computers might be altering our contemporary understanding of the past. Joining a spate of scholarship in communications and media studies focused on how today’s digital technologies reinforce, and perhaps even exacerbate, long-running inequities in American culture when it comes to race, gender, and other factors, the books remind us that the time has come to treat digital history not merely as a flashy new method, but instead as a complex intellectual endeavor that demands full-throated theoretical scrutiny and more intensive historicization.[3]

These recent books are by no means the first to begin to address the intellectual implications of digital history, but they do mark a moment in which historicization of the field plays a more prominent role than in earlier assessments. Our very “sense of history,” as literary scholar Alan Liu calls it, is up for grabs as computers continue to alter both how historians access the past and how they communicate their findings. For instance, what even constitutes an archive is changing. What a historical study looks like is too. Repositories digitally leak out the library and even the words of essays and books loosen from the printed page. History now dances across screens, darkens the computing cloud, pulsates quite literally as beams of light along fiber optic networks. How do we make sense of these dramatic changes?

Like a good marketing campaign, the first wave of digital history scholarship often played up the momentous possibilities of digital technologies for the study of the past. Excited early adopters emphasized what digital humanities scholar Bethany Noviskie ultimately criticized as the “eternal September” of new approaches. Historian Cameron Blevins similarly finds fault with the “perpetual future tense” of the field. Everything was about to change, early digital historians claimed, and yet we always only seem to be at the beginning of those changes. The great transformation was coming, and yet still has not arrived. It was as if journal articles, books, and conferences had all become some weird history profession version of the latest Apple launch event. Only figures such as Roy Rosenzweig tended to take a more cautionary, historical perspective. In formative essays such as “Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era,” he proposed that the new challenge for history in the digital age would not be a paucity of sources, but rather a firehose of them. In “The Road to Xanadu: Public and Private Pathways on the History Web,” Rosenzweig was among the first to notice the tensions between grassroots, scholarly, and proprietary modes of digitizing the past. Lara Putnam’s important 2016 essay likewise issued a cautionary tale for the intersection of digital and transnational history: digital technologies allowed for faster cross-regional study through mass digitization, but they also threatened to undercut sustained, deeply contextualized inquiry into the archives; worse yet, they privileged the Global North over the Global South.[4]

New books pick up where these and other critiques left off.[5] In some sense they are all simultaneously studies of digital history and, without always explicitly announcing it, the larger neoliberal order that emerged in full during the 1990s and in which the field of digital history is inevitably enmeshed. With its reordering of the commons and collectivity into privatized, often atomized individuals who entrepreneurially seek out connections within large-scale technologies that render equality tantalizing but also constantly undermined, neoliberalism itself is only coming into view historically.[6] The intellectual history of digital technologies and their effects on historical study might well end up having something more to tell us about neoliberalism—as well as about efforts to resist it or reimagine it.

In an intellectual history framework, these recent books about digital history’s history also point to deeper connections to the past, not just the recent era of neoliberalism. Today’s digital historical practices link to longer-running stories about very big questions: what does it mean to develop a historical consciousness?; how is that consciousness linked to understandings of artifacts, evidence, and methods of access and analysis? So, while digital history may be neoliberal, exhibiting what opponents to digital humanities have described as an ominous “dark side,” they are not only that.[7] Or if they are, their neoliberal dimensions remind us that the neo in neoliberalism itself signals a larger intellectual history that stretches back to the liberal traditions of the Enlightenment and arises within the protracted currents of modernity.

The books under review do not always tackle these larger questions directly. They are instead focused mostly on the possibilities and opportunities historians face in confronting an unprecedented abundance of digitized but unstable and ephemeral sources. Yet even in their focus on the practicalities and challenges of what Ian Milligan calls “history in the age of abundance,” Adam Crymble describes as “transformation in the digital age,” Niels Brügger refers to as the “archived web” (as distinct from the World Wide Web or digitized collections of previously “analog” material), Nanna Bonde Thylstrup refers to as “the politics of mass digitization,” Abigail De Kosnik identifies as “digital cultural memory and media fandom,” and Alan Liu views as an emergent new “sense of history,” they still reveal something of the texture of our times as it increasingly gets constituted not by older forms of artifacts and media, but rather by computational bits and bytes, servers and networks, code and commands.

The key focus for these scholars is the digital archive and how it is not the same as older modes or practices of archiving. In History in the Age of Abundance? How the Web is Transforming Historical Research, Ian Milligan asks, “what does it mean to write histories with born-digital sources?” He wants to know “how can we be ready, from a technological perspective as well as from a social or ethical one, to use the web as a historical source—as an archive?” In short, as the web itself becomes artifactual, not just a representation of older “analog” artifacts but a part of the historical record itself, how can historians best analyze it? The good news is that “historians with the training and resources are about to have far more primary sources, and the ability to process them, at their fingertips.” They will also, Milligan warns, face the problem that “super-abundance brings its own challenges” (pp. 3, 9). Most of all, Milligan is curious how the web as a historical artifact, when archived, will alter our “understanding of the past” (p. 3). How will it change processes of knowledge acquisition? To address this question, he calls for making the “largely implicit methodologies” historians use more explicit (p. 6).

Milligan’s book rejects the most positivist claims advocated by ardent cliometricians and digital humanities. He does not believe quantity trumps quality. More of something does not inevitably mean it is more true. The timeline of the past does not flow along a bell curve. “At the scales we are working with in born-digital data,” he writes, “the mere fact of something existing—or even hundreds of something existing—may not signify something significant.” Instead, “Context is king.” Therefore, while “distant reading is a necessity when working with web archives,” he writes, we must use it adroitly to “get a sense of what was being created and talked about, and what mattered to people, at scale” (p. 57). There is not just vastly more stuff when we examine websites and web pages as historical artifacts; they are also fundamentally different in their qualities as artifacts. Their constitutive elements, their very ontologies, are different; so too, the way we access them is different. Therefore, convincing arguments about them will have to move along different lines of logic, correlation, connection, and causation.

So too for Milligan, the “underlying mechanisms” of digitization and distant reading through computational tactics matter. They are far from neutral, which is precisely why he firmly believes that “transparency is imperative in the digital age” (p. 60). “Historians and other scholars using web archives,” he writes, “need to recognize the inherent subjectivity of the tools they design and use.” For Milligan:

If I designed the algorithm, my subjectivity is embedded in it: the weight given to various categories of analysis, the encoding decisions taken, the process by which unstructured text was turned into the structured data that computers make sense of, etc. And beyond that, the archives themselves are not perfect representations of the underlying reality. None of this is a neutral process: at almost every step it reflects or should reflect the user’s judgment as a researcher. All this comes before the critical process of making sense of the data. And even if the historian arrives at the same ‘answers,’ in sources and results, it does not mean that she will draw the same conclusions. As always, results need that extra step of interpretation (p. 59).

We can see all this most vividly in the case studies Milligan presents, from the vanished world of GeoCities websites to the efforts in 2013 at CERN to display the original world wide web page created by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991. In fact, by 2013 they could not display it. They had to simulate it since the original page existed through a “line-mode browser” rather than today’s web browsers. Moreover, they could not even locate the very original page, only a copy of it from December 1992. They had to, as Milligan wryly puts it, “fix” modern HTML code in order to make the page look more like it would have in 1991 (p. 65). In short, this “original” artifact was in fact a replica, yet in being a replica it was, oddly, more accurate to the past object, in its moment, than what still existed of the original in its original state.

Such are the paradoxes of digital preservation that historians must consider and with which they must contend. As Matthew G. Kirschenbaum has noticed in his work on the history of word processing and the “forensic imagination,” digital sources aren’t really things, they are processes. At their base, materially speaking, they are scores, notations to activate, but not the music itself.[8] Which is to say, the things we think of when we say “digital artifacts” are not really things at all. They are not set in stone (as it were), but rather, as new media, they exist in stepped commands awaiting execution. They are more like coiled springs in the printing press than manuscripts fresh off the platen. Digital sources are code and protocols and relationships, not objects in the conventional sense. We use our screens to perceive them, but screens are just that: a surface upon which projections appear. What we see on our screens is in fact illusory, a kind of performance of an artifact rather than the real thing. They are but a representational outcome of signals, sequences, commands, and orderings deeper within the machine. All this, according to Milligan, demands methodological reorientation and clarification. The idea of the artifact is changing in the digital era. We better keep up or get lost. Whether he is exploring the nature of web crawlers and robots.txt files or browser wars, Flash, and defunct web hosting services such as GeoCities or effort to preserve the original Tim Berner-Lee’s original webpage at CERN, this is Milligan’s key point.

Adam Crymble would largely agree, but in Technology and the Historian: Transformations in the Digital Age, he focuses even more explicitly on the recent past of historical study itself. He believes that as historians “increasingly work with computers, computers will increasingly exert their influence on our intellectual agenda.” Therefore, “we must understand both their strengths and the limits they impose on us.” By “putting technology at the center of the field’s own history for the first time,” he hopes to address “our professional blind spot” as historians. His goal is to present “a history of technology’s impact on historical studies” (p. 2). In place of the how-to guides and eternal sunrises of revolutionary methods that predominate, Crymble instead seeks to historicize digital history or, as he puts it, the multiple ways of “doing history in the digital age” that have emerged since the 1990s (p. 14). He investigates the origin myths of digital humanities developed back then from Roberto Busa’s use of computers decades earlier. He looks at the development of mass digitized archival holdings. He enters the classroom to investigate digital historical pedagogy. He recovers the importance of “informal channels” of digital skill acquisition among historians. And he traces the rise and fall of the academic blog over the last twenty years. Crymble’s study has a particularly transatlantic dimension since he has worked in both North America and the United Kingdom. Crymble mostly wants to emphasize the plurality of ways historians are investigating the past digitally. At the very end of his book, he also calls for a more global digital history and digital humanities, arguing that it is already moving from the North Atlantic to a more international framework.

This is most of all a book of splitting, not lumping—of foxes not hedgehogs. For Crymble, digital history consists of multiple different interests, approaches, perspectives, and pursuits. An error has been made in trying to condense it to one method, one shared vantage point on the past and how to harness computers for studying it. Nonetheless, the term digital history does summon forth, if not a unified subfield, is an “imagined community.” It began to take shape in the 1990s, according to Crymble, as a diverse group of historians who “had drunk deeply of the philosophies and culture of the digital era and who had designs on making adjustments to the status quo in the profession and the wider world” (p. 164). Whether they did so or not is still a point of contention. Whether they will so or not in the future remains to be seen.

Like Ian Milligan and Adam Crymble, Niels Brügger is keen to historicize the last twenty to thirty years of digital history. His focus, however, is less on the history of historians than on what is to be done with the massive historical record of websites and other online publications that have appeared since the early 1990s. He wants to better define the parameters of archives that preserve the web and calls for the continued development of an “archived web.” Brügger writes, “the archived web is a reborn digital medium, and as such it comes with a digitality of its own distinct from that of digitized collections and of the online web” (p. 6). “The web of the past itself is worthy of being studied,” Brügger believes (p. 15) but it “does not present itself as a phenomenon with clear and obvious demarcations indicating how a study of it should be focused.” For “unlike written documents, print media, or radio/television, where analytical objects such as ‘page,’ ‘image,’ ‘article,’ and ‘program’ seem the obvious focal points, the web does not lend itself to such straightforward and taken-for granted ways of approaching it analytically” (p. 31).

There is what we see on the web, to be sure, but really what we see is generated from underlying textual code that itself parlays electrical signals into a set of functions and outputs. The web contains layers upon layers. To archive it raises troubling questions, not only in terms of what is being archived, which is an age-old question of power in, for instance, the colonial archive, but also what Brügger calls “the intangible politics of the archiving process itself” (p. 73). For Brügger, the “archived web,” what we should understand as an archival world of born-digital, web-based publications, must always be the “reborn web.” It must be reconstructed, re-represented, even altered so that it can render as it once looked in newer web modes of structure and display (p. 74). The choices made in how we construct the “archived web” embed within the very artifacts themselves their potential for access, interpretation, meaning-making as cultural memory and history.

The mass digitization that has allowed for Brügger’s archived web even to exist at all is the topic of Nanna Bonde Thylstrup book. She probes the implications of mass digitization for “the politics of cultural memory” (p.3). For her, as those who wield digital technologies transform “historical material into ubiquitous ephemeral data” in projects that seek to increase the number of digital artifacts exponentially (think Google Books, the Internet Archive, the Million Books Project, the Digital Public Library of America or the HathiTrust Digital Library), a “new kind of politics” emerges in the “regime of cultural memory” even more than in historical studies. It is, in her view, most of all an “infrapolitical process” that is far from “rationalized and instrumental” but instead consists of “ambivalent spatio-temporal projects of desire and uncertainty” (pp. 5, 7). Indeed, for Thylstrup, “it is exactly uncertainty and desire that organizes the new spatio-temporal infrastructures of cultural memory institutions, where notions such as serendipity and the infrapolitics of platforms have taken precedence over accuracy and sovereign institutional politics” (p. 7). With mass digitization, cultural memory itself becomes part of an “anticipatory regime” in which people increasingly engage in “perpetual calculatory activities, processing affects, and activities in terms of likelihoods and probabilistic outcomes” (p. 135). So too, “new colonial and neoliberal platforms arise from a complex infrastructural apparatus of private and public institutions.” These become “shaped by political, financial, and social struggles over representation, control, and ownership of knowledge” in its new, digital forms (p. 136).

There is, Thylstrup notes excitedly, now “instant access to a wealth of works” for those who can access them. With this, there are, thankfully, new kinds of “cultural freedoms we have been given to roam the archives, collecting and exploring oddities along the way, and making new connections between works that would previously have been held separate by taxonomy, geography, and time in the labyrinthine material and social infrastuctures of cultural memory” (p. 136). At the same time, without naming it as such, a kind of Foucauldian awareness of politics appears in Thylstrup’s analysis. It is not a biopolitics in the capillaries of bodies so much as a mechano-politics in the wires of computational machines. Quoting Saskia Sassen, Thylstrup believes that “mass digitization appears as a preeminent example of how knowledge politics are configured in today’s world of ‘assemblages’ as ‘multisited, transboundary networks’ that connect subnational, national, supranational, and global infrastructures and actors, without, however, necessarily doing so through formal interstate systems.” Instead of a “sovereign decision” shaping mass digitization, it has “emerged through a series of contingencies shaped by late-capitalist and late-sovereign forces” (p. 18). It “stages a fundamental confrontation between state and corporate power, while pointing to the reconfigurations of both as they become increasingly embedded in digital infrastructures” (p. 29). It reveals conflicts “in the meeting between twentieth-century standardization ideals and the playful and flexible network dynamics of the twenty-first century.” And it manifests “at the level of users, as they experience a gain in some powers and the loss of others in their identity transition from national patrons of cultural memory institutions to globalized users of mass digitization assemblages” (p. 29). Sounds like neoliberalism, indeed.

If the politics of mass digitization take place at the level of digital infrastructure, as Thylstrup contends, then, as she writes, “political resistance will have to take the form of infrastructural interventions” (p. 138). This is just the sort of activity that Abigail De Kosnik tracks in her book Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. She combines approaches from media and performance studies to explore how fans appropriate, collect, reorient, reorganize, remix, transfigure, and share with each other and the world mass consumer media forms digitally. In the process, they create new kinds of archiving styles, “rogue” ones according to De Kosnik. Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s theories of outlaw “rogue” states and Diana Taylor’s distinction between archive and repertoire, by which Taylor meant the difference between embodied knowledge conveyed through performance and written knowledge fixed in archives, De Kosnik believes that “Rogue archivists explore the potential of digital technologies to democratize cultural memory” (p. 1-2).[9] Although she grants that digital technologies and even rogue cultural memories themselves are not automatically revolutionary, and may even “serve the interests of dominant classes and groups,” hers is a mostly hopeful perspective. Fan-built digital archives, she contends, improve “the positions and fuel the activities of subordinated individuals and collectives” (p. 10).

De Kosnik finds internet fan fiction archives particularly “valuable as objects of study because they are archives of women’s digital culture and queer digital culture” (p. 12). Overall, for De Kosnik, the era of digitization and the internet has meant that “memory has fallen into the hands of rogues, and what this explicitly means is: memory has fallen into female hands, into queer hands, into immigrant and diasporic and transnational hands, into nonwhite hands, into the hands of the masses” (p. 10). This has endowed them with more status, she argues, by including their “idiosyncratic repositories” in digital cultural memory as a whole (p. 18). Their labor at assembling “rogue archives” is the key. For De Kosnik, in contrast to Milligan, Brügger, and Thylstrup, the focus should not be on the technology itself, but rather on how “communities must work to conserve their digital artifacts and rituals, or risk losing them to the digital’s proclivity for ephemerality and loss” (p. 30).

Using oral history and data scraper-Python scripts, De Kosnik notices not so much new archives as new “repertoires” of archiving. She categorizes these into “three major digital archival styles” and gives them “the names ‘universal,’ ‘community,’ and ‘alternative’” (p. 73). Universal archivers “seek to replace canonicity and selective archiving” with a broader definition of what material counts as important to preserve and remember. Community archivers expand this work even further, beyond traditional institutions to everyday people. Most fascinating for De Kosnik are alternative archivers, who “propose new canons, canons of new types of objects or objects that are ignored by traditional archives. …content to let their assemblies of odd, strange, controversial, nongeneric, or radically new texts stand alongside those older sets of privileged works” (p. 75). The work of alternative digital archivers create “countercollections, storehouses of culture outside highly visible ‘official’ cultures, from which users can construct their own canons employing curatorial tastes that deviate from the cultural norm” (p. 104).

Fan fiction becomes De Kosnik’s prime example of alternative archiving. In her view, with digital fan fiction, the archive online becomes a stage. The network becomes a place of “virtual enactments; it is the performance space, a ‘global theater,’ in which shows are put on and received by any user who wishes to participate in the ‘perpetual happening’,” and “new stories emerge from new interactions all the time; each new story then gives onto more interactivity between fan authors and fan readers” (p. 246, 254). Free software and digital information preservation also become another example for De Kosnik of the digital archive not as a fixed place but rather as an active zone of making and remaking. They are not “prisons for documents that optimize for stasis and timelessness”; instead, they become “‘dynarchives’ (a term coined by Wolfgang Ernst) that invite interaction and remain (theoretically) forever in flux” (p. 275). Yet while Ernst, in his “media archeology” approach, emphasizes the ways machines can capture aspects of the past that humans did not discern at the time, De Kosnik focuses much more on what the humans themselves are doing.[10] What she calls “archontic production,” by which she means the reinterpretive performance of archiving online through “appropriative creativity,” “reveals that digital popular culture is enacting its own archival turn.” Audiences of popular culture, she contends, are resisting “the notion of ‘archive’ as a place where documents remain untouched and frozen, under ‘house arrest,’ and instead realize their power to seize upon all of culture, especially mass media, as an archive, as an ever-expanding collection of archives that exist for their use, that contain the raw matter for their generation of new narratives, new connections, new significations” (pp. 296, 279). The archive itself is no longer a storage site in the conventional sense of the term; instead it flows, flickers, and flourishes or fades. It has a rhythm rather than remaining silent. Its digital archivists iterate and reiterate as they gesture to their warehouse of goods on display.

In this way, we might note that digitization is not inherently archival, as De Kosnik is keen to point out. If anything, it tends toward what Wendy Hui Kyong Chun calls an “enduring ephemeral” state, a kind of endless present tense.[11] De Kosnik sees many “political potentialities” for cultural memory in this context (p. 298). Borrowing from the traditions of subcultural and cultural studies, she contends that through their unofficial archival efforts “rogues of digital culture do not ‘resist’ culture or law” directly. Instead, “they seep into, disfigure, overtake, and reform (in ‘whimsical,’ ‘sometimes ambiguous’ ways) structures of culture and of law.” One wonders, however, where the line really is between the official and the unofficial in contemporary corporate mass consumer culture. Do not mainstream forces of corporate and even governmental control seek to absorb alternatives to the mainstream in what Thomas Frank famously called a “conquest of cool”?[12] I’m hip, says the Madison Avenue adman, selling commodified rebellion and difference to the mainstream. Mass culture has gone subcultural. It is a veritable rogue’s gallery.

In recent decades, not only companies, but even politicians get in on the action. The president of the United States plays it cool these days, whether playing the saxophone (Clinton), painting (George W. Bush), singing lines from rhythm and blues songs (Obama), undermining everything in his path through mean, trashy comic satire (Trump), or wearing aviator shades and talking about vintage cars (Biden). Of course, those might not be “cool” gestures to everyone, but they are performative attempts to blur the lines between the official and the unofficial, the powerful and the casual. One wants De Kosnik to grapple more thoroughly with the difference between non-normative digital archiving and its acceptance—even encouragement—within the mainstream. Where does the fan fiction end and the company-approved social media fandom begin?

After all, has not Silicon Valley itself sought to define corporate cool at least since the rise of the personal computer industry in the 1970s? Do not Silicon Valley’s elites picture themselves as rebels in the belly of the beast, throwing monkey wrenches (or at least motherboards and mice) into the machines of conformity? Yet with its legions of “tech bros,” and its weird, troubling mix of libertarian and liberal efforts to “do good” and “do well” all at the same time, Silicon Valley speaks to the direction of analysis in which De Kosnik moves: underneath the gestures to subversion lie the achievement of dominating, exploitative power. How does this kind of rogue behavior relate to the rogue archiving that De Kosnik gives such effusive praise? I wish she confronted more directly how the official and unofficial overlap.

If De Kosnik concentrates on “digital cultural memory,” Alan Liu brings our attention back to history. His Friending the Past is perhaps the most profound of these recent books about how digital archives and digital history are changing our sense of historical consciousness. A Wordsworth scholar and longtime investigator of neoliberal trends as well as one of the earliest digital humanities investigators with his project Voice of the Shuttle, a website for humanities research, Liu seeks to understand “the sense of history in the digital age,” as he puts it. He wants to know if “the network effects empowered by today’s new media are capable of sustaining a contemporary equivalent of the sense of history?” Liu asks if “such a ‘sense of the network,’ as it might be called” can “correspond—or at least be accountable—to the older sense of history.” He wonders if it might “even ameliorate that older sense of history—the partner, we remember, of cruel nation- and empire-building projects conducted through the past worldwide web of trade, military, religious, transportation, and other networks?” Liu wonders “what can the sense of history be for us now?” (p. 8).

Liu’s writing can be dense, and he arrives at history from the domain of literary, cultural, and media studies more than intellectual history traditionally practiced, however his book virtually explodes with ideas for intellectual historians to consider. One of his book’s wonderful qualities is to open the valve between contemporary digital technology and Romantic literature. He seeks, as he puts it, “use Wordsworth to hack digital time, and digital time to hack Wordsworth” (p. xi). Throughout the book, Liu not only invokes Wordsworth to make sense of what is happening to our sense of time in the digital era, but also maps contemporary digital terms—network, WAN, data, code, crowdsourcing, algorithm, WARC files, Web 2.0—back on to the past so that we see continuities as much as changes. Sometimes this gets a bit too cute, but it is generally a clever and compelling way to situate his study of the sense of history in the digital now.

While Wordsworth and Romanticism help us think about the digital era, and vice versa, Liu’s book is ultimately more about ruptures than consistencies across time. He believes that in the digital era “the quality of the suspensive now that allows us to share a sense of history grows ever more fragile.” Past and present increasingly collapse into one another. Therefore, he argues, we must confront the new “post-linear” technologies that are replacing older experiences of time’s passing, of temporality itself (p. 4). Today, he writes, “The sense of history we pass on to you is like the ‘flickering signifier’ of the cursor blinking on and off right here and now on our word-processor screen where we are imprinting/pixelating our speaking-in-writing.” Whereas “in the nineteenth century one needed to feel the heft of the tomes of Historismus written by the original ‘historicists’ to sense the weight of ages, so today in the digital age one needs to handle the apparatus and the code to gain a feel for the future of the sense of history” (p. 8). To that technology Liu turns.

In a brilliant reading of the development from older constructions of linear historical timelines to the digital timeline found in the Javascript-based tool Timeline.JS, Liu discerns a key aspect of what he takes to be the shifting sense of history today. While older timelines were static, fixing the relation of one event to the next, this is only how Timeline.JS looks on the surface when it displays on a screen. Deeper in the code the events one assembles to display in the Timeline.JS interface are in fact unconnected “orphan” elements in a dynamic database. Using the now ubiquitous

tag, they can be arranged in relation to each other any way one wishes. Time itself, in the conventional linear sense, starts to crack apart into discrete elements: cells in a spreadsheet, blocks in a sequence of code. One can order them any which way.It is this sense of intensified “contingency” that Liu believes underpins our changing sense of history in the digital age. In particular, it challenges assumptions about cause and effect, which seem to become increasingly severed from each other without any particular set relationship. “Historical ends,” he believes, “become autonomous” in the new sensory worlds produced by networked digital architectures of database and code. Cause and effect as we know them stretch apart, even break and float freely, then conjoin in new configurations. As Liu puts it, “both origins and ends transform into objects/nodes in an overall reimagination of history as networked connectivity” (p. 213).

He goes still further in mapping out the increased nebulous fluidity of this strange new context. “What the objects/nodes making up today’s data transport and structuring systems tell is not time,” Liu boldly contends. Instead, “They tell about timing effects.” For instance, they “coordinate one and all one’s friends and followers in a rebalancing of individual meaning and collective significance creative of an altered sense of history.” This altered sense arises from how, Liu writes, “contingency reprograms the temporal parameters of the sense of history (especially the punctual and durational, and static and dynamic parameters) so that older modes of historical understanding reorient away from the sense of time as time (conceived as an axis) toward the sense of timing (conceived as a network of independently activated yet coordinated events)” (p. 214).

In this new, swarming, murky world of time in motion, discrete elements become untethered from any sort of deep social relationality. They now float, like so many

tags, in an ether of computational interactions. Therefore, “the balance of the parameters of the sense of history changes” and, as Liu puts it, “the relation of understanding to sensation, for instance, adjusts in the direction of ‘must see’ viral videos or ‘fake news.’” So too, the orientation “of the individual to the collective adjusts to favor, for instance, power-law imbalances between meme-leaders and followers, as well as the fragmentation of the public sphere into mutually incomprehensible media ‘bubbles’” (p. 214). Gone are the clear power lines (and lines of power) found in past institutional arrangements or the familiar arrangements of liberal civil society. Instead, in the contemporary world of the World Wide Web, “it is all a web,” as Liu puts it (p. 213). For him, there are many ways to understand these transformations: “Expressed geopolitically as globalism, technologically as networking, and artistically as intertextuality, appropriation, sampling, and so on, connectivity is the presentist ‘just-in-time’ end—or loose end—of multiple, reconfigurable terminations” (p. 213).We, and our senses of history, are potentially more connectable, but in more fragmented ways. We are multiple. We are endlessly reconfigurable. “If all our creations are imagined to be discrete worlds,” Liu writes, “then in the idiom of communications technology they are structurally ‘nodes’.” For Liu, “the end of a node—in the sense that a wire beginning at one node terminates in another—is connectivity.” Therefore, now “we are all nodes sending ‘packets’.” We reach out for “other nodes in a call for instantaneous, transient connectivity” (p. 213). History, in this context, has not short-circuited, It certainly has not ended (take that Francis Fukuyama!). If Liu is correct in his assessment, what has changed dramatically are our ways of accessing past events and rendering them in a compelling, convincing order. It is, he writes, “the parameters that mete out a networked—and no longer simple, regular, measured—sense of history” that we must contend with today.

Always slippery, fragmentary, elusive, the “parameters” of history have become even more provisional, more elastic. As historians reach for them and try to arrange them into stories and meanings through digital techniques and channels, many have gotten wired, in the caffeinated sense. Read any over-enthusiastic digital history blog for that energy. Others long for history to again be more hardwired, set in its ways. They want to constrain the study of the past, returning it to pre-digital methods that, despite the best of intentions, can threaten to produce reassuring myths instead of contingent and complex truths. History sure can feel rent, shattered, broken, fragmented these days, yet also oddly ossified and stodgy too.

Maybe, in the strange context of the digital era, intellectual history has something important to offer. The capacity of intellectual history to examine not just what happened, but also how it came to be ideationally and imaginatively becomes quite valuable. Rather than an embrace of simplified notions of political economy or fated cultural inevitabilities or technological determinisms, we might stick with intellectual history.[13] Maybe it can better ground us precisely because of its dexterity. Able to handle the abstract codes and confused contingencies that shape and undergird historical forces, intellectual history might be one way to maintain navigational balance in the dizzying weather of today’s wireless world.

[1] See Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic (July 1945), 101–108 and JCR Licklider, “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” The Transaction of Human Factors in Electronics (March, 1960), 4-11.

[2] See, for instance, Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig. Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005); William G. Thomas, II, “Computing and the Historical Imagination,” in A Companion to Digital Humanities, eds. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, John Unsworth (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004), 56-68 and “The Promise of the Digital Humanities and the Contested Nature of Digital Scholarship,” in A New Companion to Digital Humanities, eds. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, John Unsworth (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2015), 524-537; Edward Ayers, “The Pasts and Futures of Digital History,” History News, 56, 4 (Autumn 2001), 5-9; Various Authors, “Interchange: The Promise of Digital History,” Journal of American History 95, 2 (September 2008): 452–491; and Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[3] There are too many studies of race, gender, and other factors to list completely, however for starters see Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: NYU Press, 2018); Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Medford, MA: Polity, 2019); Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, Data Feminism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020).

[4] Roy Rosenzweig, “Road to Xanadu: Public and Private Pathways on the History Web,” Journal of American History 88, 2 (September 2001): 548–579 and “Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era,” American Historical Review 108, 3 (June 2003): 735-762; and Lara Putnam, “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast,” American Historical Review 121, 2 (April 2016): 377-402.

[5] For additional critiques in digital history, see, for instance, Sharon Leon, “Returning Women to the History of Digital History” Draft 1, [Bracket], 7 March 2016; Jessica Marie Johnson, “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads,” Social Text 36, 4 (2018): 57-79; and Tim Hitchcock, “Confronting the Digital: Or How Academic History Writing Lost the Plot,” Cultural and Social History: The Journal of the Social History Society 10, 1 (2013): 9-23. Many additional critiques of digital humanities more broadly have been published as well.

[6] See, for instance, Lily Geismer, “Agents of Change: Microenterprise, Welfare Reform, the Clintons, and Liberal Forms of Neoliberalism,” Journal of American History 107, 1 (June 2020): 107–31.

[8] See Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007); Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); and “Software, It’s a Thing,” Medium (blog), 26 July 2014. See, also, Trevor Owens, et. al., Preserving.exe: A report from the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program of the Library of Congress, October 2013.

[9] Jacques Derrida, Rogues: Two Essays on Reason, trans. Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005); Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2003).

[10] Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

[11] Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory,” Critical Inquiry 35, 1 (2008): 148–71.

[12] Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

[13] For critiques of the recent turn to political economy and the history of capitalism, see Nan Enstad, “The ‘Sonorous Summons’ of the New History of Capitalism, Or, What Are We Talking about When We Talk about Economy?,” Modern American History 2, 1 (March 2019): 83–95 and Paul A. Kramer, “Embedding Capital: Political-Economic History, the United States, and the World,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15, 3 (July 2016): 332–3. As examples of the call to return to political economy, Enstad cites Sven Beckert, “History of American Capitalism,” in American History Now, eds. Eric Foner and Lisa McGirr (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 314–35; Louis Hyman, “Why Write the History of Capitalism,” Symposium Magazine, 8 July 2013, reprinted as Hyman, “Why Study the History of Capitalism,” in American Capitalism: A Reader, eds. Louis Hyman and Edward E. Baptist (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014) xvii-xxiv; Kenneth Lipartito, “Reassembling the Economic: New Departures in Historical Materialism,” American Historical Review 121, 1 (February 2016): 101– 39; and Philip Scranton, “The History of Capitalism and the Eclipse of Optimism,” Modern American History 1, 1 (Mar. 2018): 107–11. For the turn to a rigid use of fated cultural values shaping history, see recent popular works such as Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018). For technological determinism, see popular works such as Thomas L. Friedman, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005) or Chris Anderson, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More (New York: Hyperion, 2006); more probing essays on the topic can be found in Merritt Roe Smith and Leo Marx, eds. Does Technology Drive History?: The Dilemma of Technological Determinism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994).

September 17, 2021

Tenure’s Tenure

What is an academic higher education worker, exactly? Is a professor still even a professor, or even treated as a professional, these days? Are college faculty ultimately to be tenured scholar-teachers or just instructors? Are they to generate new knowledge in their respective fields as well as teach it, or are they merely teachers imparting to students what is already known?

With potentially transformative changes to higher education funding rules under consideration in Congress’s 2021 budget reconciliation process, professors themselves cannot quite agree. Some dream of an unprecedented push for more tenure-track jobs. Others have given up the ghost on tenure—it’s tenure itself, they believe, has been denied. Forty years of neoliberal assaults on higher education, particularly public higher education, has led to a crisis of underfunding and overpricing, not enough support for institutions and soaring tuition for students. Working conditions have similarly suffered, with legions of precarious adjunct faculty far outnumbering more secure tenured professors.

What is to be done in this difficult situation? Some dream of a dramatic return to—or maybe more accurately an unprecedented expansion of—the ideal of tenure among the professoriat. Others fear this vision will ironically undermine the non-tenured rather than give them access to tenure-track positions. Academic higher education workers, they believe, should not seek more tenure lines; instead, they should demand better working conditions for non-tenure track instructors and lecturers.

To push for a greater percentage of tenure-track jobs or the improvement of non-tenure track jobs, that is the question. Of course, many push for both, and they explicitly seek to get legislators to embrace the conversion of adjunct and lecturer positions into tenure-track posts. So too, many see the crisis that is all around them in academic labor as well as in the affordability of a college education. They are keen to link an expanded version of tenure not to raising tuition for students, but rather, somewhat counterintuitively, to making the first two-years of public college or university education free for students and keeping access to it inexpensive. Check out, for instance, the recommendations of the the Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Education.

Others find these big dreams dubious. Those who have been through the wringer of precarious adjunctification are generally far more cynical, and who could blame them? Administrators keen to get ahead as university managers by cutting costs to the bone and producing a docile faculty labor force will seek out all the loopholes in new requirements for tenure track posts, many adjuncts protest. Worse, yet, maybe they will simply fire all the adjuncts and make tenure-line faculty teach more. Adjuncts distrust the tenured elites of the profession, whose own ability to conduct research or teach less now falls squarely on the backs of adjunct labor and who have repeatedly failed to confront the crisis of employment in the profession.

Behind these struggles lurks the effort to build solidarity across different positions within the dysfunctional, unhealthy ecosystem of today’s academic higher education labor market. Behind those are deeper and implicit (and occasionally explicit) visions of what a professor is and should be as well as what, exactly, colleges and universities are for in modern America.

If one clings to the ideal of the scholar-teacher as professor, both producing new knowledge and teaching it, then one tends to believe in the goal of expanding tenure rather than abandoning it. if one pictures tenure as a path to better experiences for students, one supports this position. If one imagines these kind of tenured posts as solid, stable, middle-class modes of professional employment, one wants to see more of these kinds of jobs. And if one imagines the university as governed by the faculty who serve as its stewards rather than being run by a detached class of administrators whose primary goals are to please boards of trustees and get ahead in their own managerial careers, then one tends to dream of an expansion of tenure.

By contrast, if one sees that vision of tenure as a bitterly vanquished dream, one shifts away from expanding the practice to a different goal: building better working conditions for non-tenure track jobs. Perhaps having been browbeaten into submission by the often harsh practices of employment that now dominate the higher education faculty labor market, in which the vast majority of courses and positions are taught by non-tenure track faculty, a person in this camp finds the current utopian dreams of the tenure-enthused unconvincing. One may even deeply resent those with tenure or on a path toward it. “Why them, and not me?” one might ask. The tenured still do not grasp just how awful the situation is, many adjuncts feel. Indeed, they do not want to grasp it, since they benefit from it, getting to do more research while adjuncts do take over their teaching duties. Tenure has run its course, those in this camp contend. It does more damage than good now. “Pie in the sky” plans of reinvigorating tenure will only cause the most vulnerable, precarious academic workers to lose even their tenuous hold on scholarly labor as adjuncts. So, these academic workers argue, why obsess about tenure when the fight is in developing better working conditions and wages for non-tenure track academic positions?

The differences here often have a lot to do with work experiences. They also have to do with something else: perceptions of the larger historical moment. Are we still in an era of neoliberal austerity, of a refusal by Americans to imagine government redistributing wealth in the name of the common good? Or are we passing out of that phase into something new—or maybe, better said, are we witnessing the return of something old: the New Deal?

How one interprets the horizon of political possibility in the United States at the start of the 2020s shapes which path one supports for going forward. If one thinks the country is at the brink of a new era of investment in the public good through government redistributing wealth, one may embrace the bold, idealistic plan for more tenure positions. If one is not convinced that this is the case, one may abandon tenure for the more practical goal of improving adjunct work under current conditions.

To stay in the arena of historical perceptions, this all seems a bit like age-old struggles in the American labor movement between trade unionists and industrial unionists. Yet today’s disagreements do not quite parallel the older tensions. In some ways they are even flipped around. The trade unionists of old—the AFL, the Samuel Gompers of the world at the turn of the last century—sought to close ranks around their skilled labor. They wanted to lock people out and defended the interests of their era’s equivalent of tenure-track employment. Today’s defenders of tenure, however, imagine the opposite. For them a dramatic expansion of tenure would, if legislated effectively, dramatically expand the ranks of the professoriat’s elites. It would open up the field. It would, in effect, create one big industrial union and overcome the current dividing and conquering that splits the ever-shrinking tenured and tenure track professors from the masses of adjuncts.

By contrast, those who want to shift toward improving adjunct working conditions now without focusing on tenure seem at first to be more like the industrial unions such as the CIO. They are like a larger working class of supposedly (but not really) deskilled workers who no longer can develop the specialized skills of scholars-teachers. They are teachers relaying that knowledge (no simple skill that!). Moreover, they lack the autonomy that the trades of yore idealized, and they no longer care about it. Pay me a good wage, they seem to say, and make my working conditions halfway decent and I no longer care about the autonomy that tenure imparts. Nor do I care anymore about being a steward of the university. We are but wage workers, they say, as in any other industry. What is odd, however, is that this seemingly industrial union position winds up seeking to circle the wagons. It sets out to defend the limited but precarious place in the higher education economy that adjuncts already occupy. In today’s academia, Gompers dreams of academic labor utopia for all; the CIOers call for a conservation of the existing order.

In this fraught situation, full of possibility, uncertain as to what direction the United States is headed, solidarity across academic higher education laborers is difficult to achieve. To boot, we are talking about professors. Go to any faculty meeting or conference and you’ll see professors disagreeing. That’s part of what professors do. They debate. They argue. If anything they are bound together by their belief in questioning received ideas. Are professors to remain professionals? On what terms? And who will even get to speak at the faculty meeting or have the resources to attend the conference in the future?

These questions point to how the working and learning conditions in the halls of academia are inextricably linked to the decisions made in the halls of state power. What kind of political economy might emerge in twenty-first century America? What kind of tax policy and vision of the public good shall become hegemonic? How students will access the world of college—and who, exactly, will be there to meet them at the campus gate, in the old brick building, or at the Cold War cinderblock hall when they get there—remains unclear.

September 10, 2021

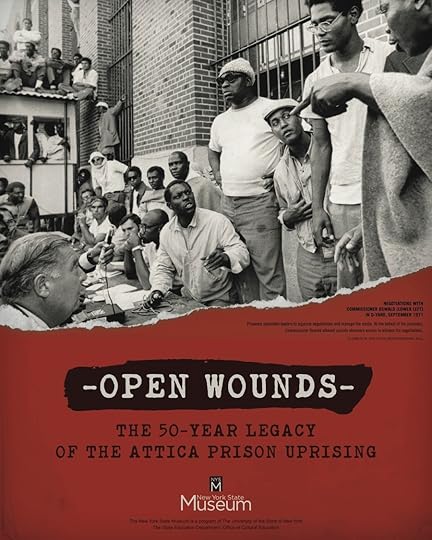

2021 September 14—Attica Prison Uprising Exhibit Discussion

Don’t miss the New York State Museum’s traveling exhibition “Open Wounds: The 50-Year Legacy of the Attica Prison Uprising” on display Monday-Wednesday, September 13-15, in Seymour Student Union Gallery. A special exhibition viewing and discussion will take place Tuesday, September 14, 5-7 pm with Will Walker, Joey Jackson Intercultural Center Coordinator, and Dr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor of History, SUNY Brockport.

“WE ARE MEN! WE ARE NOT BEASTS AND WE DO NOT INTEND TO BE BEATEN OR DRIVEN AS SUCH.” – L. D. BARKLEY, SPOKESMAN OF THE ATTICA UPRISING, 1971

In September 1971, incarcerated men at the Attica State Correctional Facility found themselves in a standoff against New York State. Conditions at the prison were deplorable and dehumanizing: abuse, overcrowding, and inadequate food and medical care among the problems. An argument between prisoners and guards on September 9th led to a fight. One Correction Officer, William Quinn, was badly beaten and died of his injuries two days later. Prisoners ultimately took 42 hostages from prison staff in an attempt to negotiate satisfactory changes, listing 28 demands that were similar to an earlier manifesto protesting their conditions at the prison. Some were met, but amnesty for the prison uprising was refused by New York State officials. The forcible retaking of Attica by New York State Police on September 13th, 1971 left 39 people dead, including nine hostages. All were killed by gunfire from law enforcement. Attica is remembered as both a failure of the American prison system and a call for justice against human-rights violations. This exhibition presents various viewpoints of the uprising and its aftermath and explains why this event is still important 50 years later.

Co-sponsored by the Department of History; the Department of African & African American Studies; the Department of Criminal Justice; the Joey Jackson Intercultural Center; the SUNY Brockport Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion; and the Seymour Student Union. Panels curated by the New York State Museum.

Attica-For-Further-Study-Handout_Final-Version_Kramer_2021-09-142021 September 14—Open Wounds: The 50-Year Legacy of the Attica Prison Uprising Exhibition

Don’t miss the New York State Museum’s traveling exhibition “Open Wounds: The 50-Year Legacy of the Attica Prison Uprising” on display Monday-Wednesday, September 13-15, in Seymour Student Union Gallery. A special exhibition viewing and discussion will take place Tuesday, September 14, 5-7 pm with Will Walker, Joey Jackson Intercultural Center Coordinator, and Dr. Michael J. Kramer, Assistant Professor of History, SUNY Brockport.

“WE ARE MEN! WE ARE NOT BEASTS AND WE DO NOT INTEND TO BE BEATEN OR DRIVEN AS SUCH.” – L. D. BARKLEY, SPOKESMAN OF THE ATTICA UPRISING, 1971

In September 1971, incarcerated men at the Attica State Correctional Facility found themselves in a standoff against New York State. Conditions at the prison were deplorable and dehumanizing: abuse, overcrowding, and inadequate food and medical care among the problems. An argument between prisoners and guards on September 9th led to a fight. One Correction Officer, William Quinn, was badly beaten and died of his injuries two days later. Prisoners ultimately took 42 hostages from prison staff in an attempt to negotiate satisfactory changes, listing 28 demands that were similar to an earlier manifesto protesting their conditions at the prison. Some were met, but amnesty for the prison uprising was refused by New York State officials. The forcible retaking of Attica by New York State Police on September 13th, 1971 left 39 people dead, including nine hostages. All were killed by gunfire from law enforcement. Attica is remembered as both a failure of the American prison system and a call for justice against human-rights violations. This exhibition presents various viewpoints of the uprising and its aftermath and explains why this event is still important 50 years later.

Co-sponsored by the Department of History; the Department of African & African American Studies; the Department of Criminal Justice; the Joey Jackson Intercultural Center; the SUNY Brockport Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion; and the Seymour Student Union. Panels curated by the New York State Museum.

Attica-Exhibit-Poster_Sept-2021September 9, 2021

Covid Open Pit

August 31, 2021

Rovings

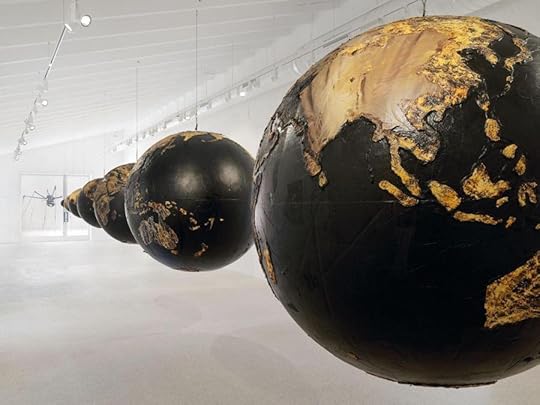

Installation views, Mark Bradford, Masses and Movements at Hauser & Wirth Menorca. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.SoundsZeena Parkins: The Illustrated Origin Story, The Roulette TapesVal Jeanty: The Spirit Story, The Roulette TapesShelley Hirsch: Primal Impulses, The Roulette TapesShelley Hirsch, Soundcloud pageVal Jeanty, Soundcloud pageIkue Mori, Sand StormPhil Baugh, “Country Guitar” (h/t Christian Gallo at the Dingy Old Jukebox podcast)Phil Baugh, “California Guitar”Various Artists, Echoes of the Ozarks, Vol. 1Julianna Barwick & Ikue Mori, FRKWYS, Vol. 6William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, BBC SoundsThe Pillow Book, BBC SoundsKeeping the Wolf Out, BBC SoundsFall of the Shah, BBC SoundsInflation Politics with Tim Barker, The Dig podcastWordsHenry Glassie, Passing the Time in BallymenoneKevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake NewsKwame Anthony Appiah, “The Prophet of Maximum Productivity,” New York Review of Books, 14 January 2021Jeremy McCarter, Young Radicals: In the War for American IdealsJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His IdeasJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, The Ideas that Made America: A Brief HistoryFrederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by HimselfDavid Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom“Walls”Mark Bradford, Masses and Movements, Hauser & Wirth MenorcaCaroline Kent, Chicago Works—Victoria/Veronica: Making Room, Museum of Contemporary Art ChicagoDawoud Bey: An American Project, Whitney Museum of American ArtPuppets of New York, Museum of the City of New YorkMutual Convergence: Yasi Alipour & Cy Morgan, Geary Contemporary“Stages”Jason Stein @ Constellation ChicagoMatthew Shipp @ Constellation ConstellationVal-inc @ Le StudioScreensHostilesDead ManTehran Season 1Gardener’s World

Installation views, Mark Bradford, Masses and Movements at Hauser & Wirth Menorca. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.SoundsZeena Parkins: The Illustrated Origin Story, The Roulette TapesVal Jeanty: The Spirit Story, The Roulette TapesShelley Hirsch: Primal Impulses, The Roulette TapesShelley Hirsch, Soundcloud pageVal Jeanty, Soundcloud pageIkue Mori, Sand StormPhil Baugh, “Country Guitar” (h/t Christian Gallo at the Dingy Old Jukebox podcast)Phil Baugh, “California Guitar”Various Artists, Echoes of the Ozarks, Vol. 1Julianna Barwick & Ikue Mori, FRKWYS, Vol. 6William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, BBC SoundsThe Pillow Book, BBC SoundsKeeping the Wolf Out, BBC SoundsFall of the Shah, BBC SoundsInflation Politics with Tim Barker, The Dig podcastWordsHenry Glassie, Passing the Time in BallymenoneKevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake NewsKwame Anthony Appiah, “The Prophet of Maximum Productivity,” New York Review of Books, 14 January 2021Jeremy McCarter, Young Radicals: In the War for American IdealsJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His IdeasJennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, The Ideas that Made America: A Brief HistoryFrederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by HimselfDavid Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom“Walls”Mark Bradford, Masses and Movements, Hauser & Wirth MenorcaCaroline Kent, Chicago Works—Victoria/Veronica: Making Room, Museum of Contemporary Art ChicagoDawoud Bey: An American Project, Whitney Museum of American ArtPuppets of New York, Museum of the City of New YorkMutual Convergence: Yasi Alipour & Cy Morgan, Geary Contemporary“Stages”Jason Stein @ Constellation ChicagoMatthew Shipp @ Constellation ConstellationVal-inc @ Le StudioScreensHostilesDead ManTehran Season 1Gardener’s World

August 27, 2021

Syllabus—The American Mind: What Were They Thinking?

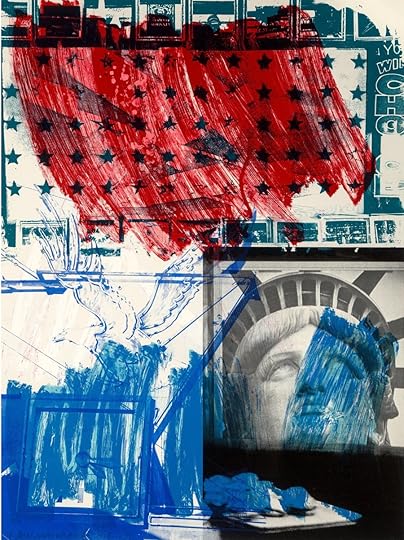

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), People for the American Way, 1991.Overview

Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), People for the American Way, 1991.OverviewHow have Americans thought about themselves and their world? How do ideas matter to history? Is there such a thing as “the American Mind”? How have Americans contested who is part of it? We explore a diversity of past voices that remain relevant today through primary sources and historical scholarship. Students read selected sources and studies in US intellectual history, engage in extensive discussion, and develop a set of analytic writing assignments. To develop employable, professional skills, students also pursue editorial/research assistantships in the course on a book roundtable for the online US Intellectual History Journal, acquiring editing, research, project management, and digital production skills in the process (no previous editorial or digital experience required). Graduate students will complete a “digital sidebar” project (timeline, map, playlist, annotated bibliography, or other component of book roundtable.

Course MaterialAvailable at Brockport bookstore, bookseller of your own choice, and on reserve at Drake Library.

Required:Kevin Mattson, We’re Not Here to Entertain: Punk Rock, Ronald Reagan, and the Real Culture War of 1980s America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020) **focus for USIH Journal book roundtable**Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, The Ideas That Made America: A Brief History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019)Jeremy McCarter, Young Radicals In the War for American Ideals (New York: Random House, 2017)Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, ed., How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012)Additional essays, readings, films, and multimedia materials on course websiteAt Library Reserves:David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper, eds., The American Intellectual Tradition, Volume I: 1630 to 1865, 7th editionDavid A. Hollinger and Charles Capper, eds. The American Intellectual Tradition, Volume II: 1865 to the Present, 7th editionLearning GoalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success.

Course Learning GoalsIn this upper-level history course, students have the opportunity to learn about:

historical facts concerning US historyhistorical interpretations concerning US historythe field of intellectual history as part of the historical disciplinehow history relates to the presenthow to think, write about, and discuss ideas about the past and presenthow to notice and analyze change and continuity over timehow to notice and analyze structures of power, how they have developed over time, and why they havehow to handle historical complexity through close analysis, paraphrasing, and interpretive questioninghow others have interpreted and debated the past (historiography)how to frame your own historical questionshow to develop close, accurate, compelling interpretations of historical evidence yourselfhow to improve your skills of developing a historical narrativehow to use evidence to develop a historical thesis, an argument-driven, evidence-based historical narrativehow to paraphrase effectivelyhow to use source citation using Chicago Manual of Style effectively and accuratelyhow to connect your historical inquiry to useful, employable professional skills (editing, research, project management, writing, and digital publishing)History Department Learning GoalsArticulate a thesis (a response to a historical problem)Advance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Style) of documentation when referencing historical sourcesStudents will identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workStudents will write and reflect on the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with multiple opportunities for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedbackStudents will demonstrate understanding of the methods social scientists use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisStudents will demonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of historyStudents will develop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluate an oral presentation according to established criteriaGeneral Education Learning GoalsStudents will identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ work. Students will write a short paper or report reflecting the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with at least one opportunity for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedback. EvaluationStudent info card and course contract – 5%Book review essay – 10%Midterm essay: primary-secondary source analysis – 15%Final essay: primary-secondary source analysis – 15%USIH Journal book roundtable projectEditorial/research work –Contact letter to roundtable writers – 5%Editorial assistant report 01 – 5%Editorial assistant report 02 – 5%Digital work –Scholar interview (audio file and transcription)— or —For graduate students and interested undergraduates, digital sidebar development (timeline, map, audio or video playlist, bibliography, image and caption development, short sidebar writing). – 20% (Draft – 5%)In-class presentations and participation – 20%ScheduleThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the semester, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

UNIT 01 – What Were They Thinking?Week 01 – 08/30 and 09/0108/30: Introductions09/01: What does it mean to ask “what were they thinking?,” or what is intellectual history, anyway?Materials:Peter Gordon, “What is Intellectual History? A frankly partisan introduction to a frequently misunderstood field,” unpublished manuscript, 2012Daniel Wickberg, “The Idea of Historical Context and the Intellectual Historian,” American Labyrinth: Intellectual History for Complicated Times, eds. Raymond J. Haberski and Andrew Hartman (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 305-322Brandon R. Byrd, “The Rise of African American Intellectual History,” Modern Intellectual History (2020), 1–32Optional:“Brandon R. Byrd—Redefining Intellectual History,” Fields of the Future Podcast“Brandon R. Byrd on African American Intellectual History,” AHR PodcastKiara M. Vigil, “Introduction: A Red Man’s Rebuke,” Indigenous Intellectuals: Sovereignty, Citizenship, and the American Imagination, 1880-1930 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 1-33Due 09/03: Student info sheet and course contract due (see assignments for prompt)Unit 02 – We’re Not Here to Entertain: Punk Rock, Ronald Reagan, and the Real Culture War of 1980s AmericaWeek 02 – No class on 09/07 (Labor Day) and 09/0809/08: Mattson, Preface and Prelude, pp. ix-10 — Discuss USIH Journal Roundtable plan — How to contact your writer draft emailsDue 09/10: Contact roundtable writer (see assignments for prompt)Week 03 – 09/13 and 09/1509/13: Mattson, Ch 1, pp. 11-8109/15: Mattson, Ch 2, pp. 82-173Week 04 – 09/20 and 09/2209/20: Mattson, Ch 3, pp. 174-23909/22: Mattson, Ch 4 and Epilogue, pp. 240-292Unit 03 – The Ideas That Made America: A Brief HistoryWeek 05 – 09/27 and 09/2909/27: Ratner-Rosenhagen, Introduction, Ch 1, and Ch 2, 1-5009/29: Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 3 and Ch 4, 51-96Due 10/01: Book review (see assignments for prompt)Week 06 – 10/04 and 10/0610/04: Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 5 and Ch 6, 97-13210/06: Ratner-Rosenhagen, Ch 7, Ch 8, and Epilogue, 133-180Unit 04 – Young Radicals In the War for American IdealsWeek 07 – 10/11 and 10/1310/11: McCarter, Introduction and Part 1, pp. xiii-5210/13: McCarter, Part 2, pp. 53-104Due 10/15: Midterm essay (see assignments for prompt)Week 08 – No class on 10/18 (Fall Break) and 10/2010/20: McCarter, Part 3, pp. 105-156Week 09 – 10/25 and 10/2710/25: McCarter, Part 4, pp. 157-24810/27: McCarter, Part 5 and Epilogue, pp. 249-324Optional: Reds, dir. Warren Beatty (1981)Due 10/29: Editorial assistant report 01 (see assignments for prompt)Unit 05 – How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River CollectiveWeek 10 – 11/01 and 11/0311/01: Taylor, Introduction, The Combahee River Collective statement11/03: Digital editing workshopWeek 11 – 11/08 and 11/1011/08: Taylor, Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith11/10: Digital editing workshopDue 11/12: Editorial assistant report 02 (see assignments for prompt)Week 12 – 11/15 and 11/1711/15: Taylor, Demita Frazier, Alicia Garza, Comments by Barbara Ransby11/17: The Examined Life, dir. Astra Taylor (2006)Week 13 – Thanksgiving – No MeetingsUnit 06 – Digital Editing and Wrapping UpWeek 14 – 11/29 and 12/01 – Digital editing workshops/The Examined Life11/29: Digital editing workshop12/01: Digital editing workshopWeek 15 – 12/06 and 12/08 – Wrapping up12/06: Wrapping up12/08: Wrapping upDue 12/10: Digital sidebar draft for graduate students and interested undergraduates (see assignments for prompt)Final – 12/17Final essay (see assignments for prompt)Scholar interview and/or (for graduate students and interested undergraduates) digital sidebar (see assignments for prompt)