Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 33

May 17, 2021

Cretinous Concreteness

We must neither anthropomorphize nor objectify apparatus. We must grasp them in their cretinous concreteness, in their programmed and absurd functionality, in order to be able to comprehend them and thus insert them into meta-programs. The paradox is that such meta-programs are equally absurd games. In sum: what we must learn is to accept the absurd, if we wish to emancipate ourselves from functionalism. Freedom is conceivable only as an absurd game with apparatus, as a game with programs. It is conceivable only after we have accepted politics and human existence in general to be an absurd game. Whether we continue to be “men” or become robots depends on how fast we learn to play: we can become player of the game or pieces in it.

Vilém Flusser, Post-History

Three Ways of Looking At the Camera

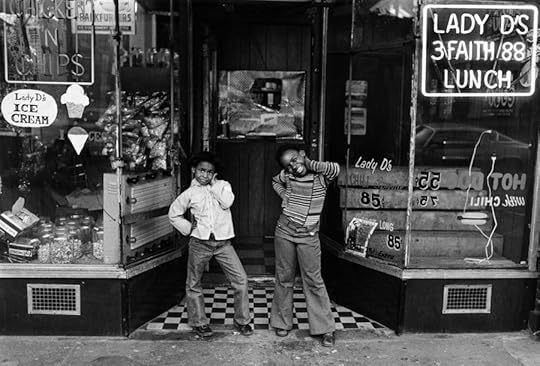

Dawoud Bey, Two Girls in Front of Lady D’s, ca. 1976.

Dawoud Bey, Two Girls in Front of Lady D’s, ca. 1976.Malick Sidibé, Teenie “One Shot” Harris, and Dawoud Bey: three remarkable photographers, the first Malian, the latter two American (Harris from Pittsburgh and Bey primarily, but not exclusively, shooting in New York). They have each gained attention from the art world in recent decades. Sidibé was a portraitist based in Bamako who captured a bustling youth culture in the 1970s and 80s. Harris chronicled life in Pittsburgh’s flourishing African-American community. Bey continues to explore African American life, and larger questions of community and place, in Harlem, Chicago, and elsewhere. Big questions about race relations, colonialism, and larger structures of power and inequality surface in their photographs, but what is most striking about looking at them together is how each photographer pictures people looking back at the camera differently.

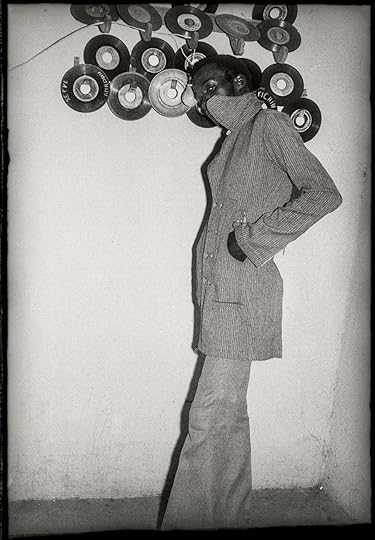

In Sidibé’s photos, people pose. “When I bought my first camera,” he explained to Brigitte Ollier for the exhibit and catalog Mali Twist, “there was a mirror attached to it.” This was because, Sidibé explained, “It was said that someone who looked at himself in the mirror became a genie. So that supernatural being, in order to demonstrate his stature, looked himself over in front of the others. He made the best of himself. Spruced himself up….” In Sidibé’s small studio and sometimes in the youth clubs, dancehalls, and outdoor settings of postcolonial Bamako, they often proudly display objects: a motorcycle, a soul or rock recording from the West, a turntable, boxing gloves, a guitar, a purse. Even when dancing they seem aware of the camera’s presence, that someone is looking at them, checking them out. They pose dressed to the nines: in the most amazing pair of flares you’ve ever seen, peering over a cool sunglasses, hats tilted just right, wearing a shirt, or not wearing one at all. They pose themselves for the camera, but they also pose the idea, often with their eyes, that they are not just there to be seen for the camera, but also beyond the camera, through the camera. They look out at the world through the lens. They look out at the future in the lens.

Malick Sidibé, Je Suis Fou des Disques, 1973.

Malick Sidibé, Je Suis Fou des Disques, 1973.By contrast, Teenie Harris’s photos bring us back to the past. He documents African American Pittsburgh in the 1940s and 50s, with images of nightclub owners and baseball stars, politicians and bigwigs, but also everyday folks, kids, and even, like the infamous Weegee in New York City, gruesome murders. To gaze at Harris’s photos is to notice people not looking back at you. They don’t seem to care for the future, but rather for the robust, fascinating world in which they are enmeshed. They are looking at each other and for each other. They look off at something or someone else in the room, down the street, in the moment. In one photo, a woman gazes adoringly at Duke Ellington, who looks down, a bit sheepishly, signing an autograph. In another, young women eat candied apples, joyously enjoying each other’s company. They know Harris is there taking the photo but their eyes smile with camaraderie. They are together. Harris is just there to document the fun.

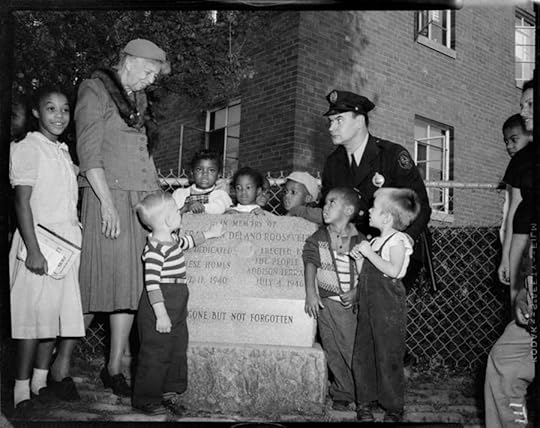

Sometimes one person’s eyes in the photo give us a clue of its larger historical stakes, as if they were the tell in a poker match, particularly one about the unfinished project of racial justice in America. A striking images captures a white police officer scowling at First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as she towers, like a gazelle, over black and white children gathered around a stone memorial for her husband Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In another image, from 1951, a muscular African American teenage boy holds a younger white child aloft in a pool during a swimming lesson. The young white boy looks like he might be about to fly, supported by the older black teenager, who looks down in concentration. Others children, black and white, seem to be posing for Harris. It is a scene of racial integration, with a sense of possibility to it, but Harris has caught a moment when one younger African American boy in the foreground of the photo looks on at the scene sourly, skeptically, registering suspicion with an out of sync side eye.

Teenie Harris, no title (Eleanor Roosevelt in Pittsburgh), 1956.

Teenie Harris, no title (Eleanor Roosevelt in Pittsburgh), 1956.In other images by Harris, one person might eye him back as he gets his shot, but everyone else seems unaware. Billy Eckstine, the jazz bandleader, looks up skeptically at Harris, but next to him Lucky Thompson, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker are lost in performance, on the cusp of inventing bebop. In another photo, Joe Lewis looks the camera squarely in the eye, but Cab Calloway gazes at Lewis slyly, Woogie Harris looks off in the distance, past the camera, and so does John Henry Lewis. In a photo of boy scouts on a street corner, everyone looks intently down at their sketchpads while they draw, but one boy looks up askance, dubiously, at his instructor. While there are certainly a number of portraits in which subjects look right back at Harris, he most of all specialized in being on the scene without being at the center of it (hence his nickname, “One Shot”). The way people are looking in the moment he snaps his photos is as important as the way they look. He captured Pittsburgh citizens in action. They don’t gaze at the camera with self-aware intensity most of the time. Rather they look at each other or are just caught up in the history Harris captured, at the scene of which they were all playing a part.

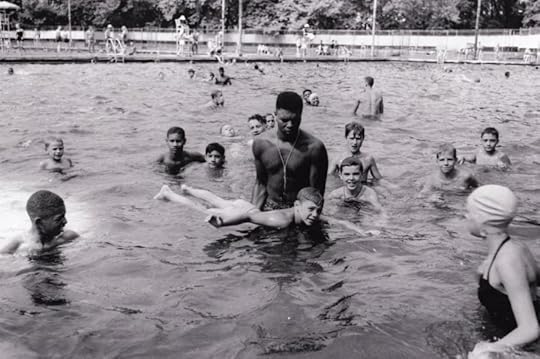

Teenie Harris, Lifeguard teaching boy to swim, Highland Park swimming pool, 1951.

Teenie Harris, Lifeguard teaching boy to swim, Highland Park swimming pool, 1951.Dawoud Bey’s photography, in contrast to Sidibé’s intense portraits and Harris’s embedded action shots, has a kind of gentle softness to it. In the 2016 survey of his career, Seeing Deeply, his subjects seem happy to see him seeing them deeply. A trust has developed, a kind of solidarity even between image giver and taker. Some look at him, some look away, some smile, others are lost in contemplation, some are in shadow, some step into the light, but all seem pleased to be with Bey.

Dawoud Bey, A Man in a Bowler Hat, from Harlem, USA, 1976.

Dawoud Bey, A Man in a Bowler Hat, from Harlem, USA, 1976.The only edge comes in his Harlem Redux photos, a sequel to Bey’s 1970s series Harlem, USA. In these photos, taken in 2016, we see the gentrification of Harlem. White business men marching ominously by the shuttered Lenox Lounge, its letters fading to black. One year later, the building would be demolished. A set of ghostly trench coats and jackets hang from a fence, hats with no heads lining its top, set against blue tarp hiding the pit of new construction behind it. You start to worry that the world has possibly overrun Bey’s sensitivity.

Dawoud Bey, from Harlem Redux, 2016.

Dawoud Bey, from Harlem Redux, 2016.But then, on the next page of the catalog, we see some of Bey’s very first photos. They are from 1964 and feature portraits of black and white classmates together on the playground of Public School 131 in Jamaica, Queens. The boys stand proudly, awkwardly, beautifully. They sit, thumbing through books (I want them to be comic books but they might not be). They are friends. They seem glad Bey is taking their photos. For he isn’t taking anything from them, he’s giving them something, a gift of seeing we get to see too.

May 12, 2021

Language Has Your Number

Words are abundances and afflictions—they give to us and take from us, they’re pleasure-givers and pain-bearers. They sing back at us not just knowledge of a singular moment but of an entire historic surround. Poetry makes a memorable impress not because it’s precious but because its actions are an impassioned activity of consciousness, and the actions change on us as we grow older. It’s a scarily private experience, it’s all personal, yet it’s only words in sequences.

W.S. Di Piero, “Table Talk,” Threepenny Review 149, Spring 2017

May 10, 2021

Lunar Graffiti

“Wow, that’s one hell of a moon!” graffiti on old railroad culvert, Stony Brook Park, Rush, NY.

“Wow, that’s one hell of a moon!” graffiti on old railroad culvert, Stony Brook Park, Rush, NY.

Transitions

Doug Varone.

Doug Varone.In my beginning is my end.

T.S. Eliot, “Four Quartets”

Dance is not just bodies moving through space; it is also about bodies moving through time. To move through time is to confront the question of transitions. From one thing to the next we go. But how we do so can vary greatly. In works from the last few years, three choreographers—Doug Varone, Liz Gerring, and Pam Tanowitz—offer three very different temporal modes of dance.

In his pieces performed in 2018 at the Dance Center of Columbia College, Doug Varone tried not to have any transitions at all. There is flow in the pieces that constitute the in the shelter of the fold series. They unfold. They fold back up. You never see the creases. The dance gradually transmogrifies so that suddenly one has moved with the dancers from one state to another, but how did we get here from there? There is no transition discrete from the ongoing transition.

Doug Varone and Dancers.By contrast, Liz Gerring often asks her dancers to pursue virtuoso but awkward moments of jerky leaps, skips, and jumps. In pieces such as Horizon and (T)here to (T)here, dancers work up to…interrupting themselves. Not unlike Merce Cunningham’s aesthetic, the choreography is staggering. The goal seems to be to linger in the gap, the synapse, with the electrical surge. Can one live in a transition? No, one must leave it, abandon it, reenter it again, for the transition to become visible, to even exist.

Liz Gerring Dance Company.In Pam Tanowitz’s choreographic take on T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, the dancers seem to get stuck in little repetitions rather than transitions. Their legs swing back and forth, an arm windmills and windmills again, a dancer runs forward at full speed only to retreat again. Time seems to hang in the balance. Maybe civilization itself does too. That’s what T.S. Eliot seems to think. “The end is the beginning,” but “what we call the beginning is often the end.”

Pam Tanowitz.We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

T.S. Eliot

These three choreographers investigate time’s inner mechanisms to see what can be done about moving from one moment to the next. As we follow their transitions, they are doing far more than just going through the motions.

The Counterculture in The World of Bob Dylan

For more see the TU Institute For Bob Dylan Studies website.

New Book: The World of Bob Dylan

May 4, 2021

Beyond Culture As Compensatory Politics

X-posted from S-USIH Book Reviews.

Christopher J. Smith, Dancing Revolution: Bodies, Space, and Sound in American Cultural HistoryAnn Powers, Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American MusicWe are living in an era of renewed emphasis on purity, an inflamed return to essentialisms. It is a time of sometimes righteous and sometimes reductionist efforts (and sometimes both) to distinguish who gets to say and do what in the cultural domain. This is true in popular culture. It is also true in historical scholarship about popular culture. In place of an interest in the twisted hybrids, knotted weaves, and multicultural amalgamations of American history, there has been a dramatic turn toward separating out cultural forms, and the people who create them, from each other, so that systems of oppression can be identified and credit and blame can be properly assigned. New wave of scholarship in cultural history seeks to point out abuses of power achieved through the manipulation of symbolic representation rather than bring to the surface buried cross-cultural rebellions and potential alliances. The latter was something cultural historians in particular grew keen to do in the last decades of the twentieth century, following the ideas of social history and cultural studies that first surfaced in the 1960s and 70s. Today that approach, with its curiosity about the subaltern, the transgressive, the resistant, is overshadowed by an urge to document how political and social domination functions culturally. Appropriation has replaced affiliation, cancellation has replaced counterhegemony, call-out culture has replaced an earlier focus on composite culture.

Two recent books, however—Christopher J. Smith’s Dancing Revolution: Bodies, Space, and Sound in American Cultural History and Ann Powers’s Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music—are throwbacks to the kind of cultural history that grew popular in the era just before our own. Back then, in the 1980s and 90s, scholars sought to recover the emancipatory possibilities of the polyglot. It seemed like highbrow theories might aid in the uncovering of the political dimensions of seemingly apolitical activities and concealed alliances. The job for the scholar of culture at that time was to master esoteric methods that might enable one to tune in to and translate the politics submerged in the lower frequencies of the historical mix. The scholar could be the one to excavate the values of cultural activities in the bottom realms of the social hierarchy. Or the scholar might be the one to lend explanatory heft to activities bubbling so close to the surface of the everyday in a mass consumer society that their deeper significance was easily missed. Cultural history’s goal, in short, became to elucidate the politics of areas of human life that were previously imagined as apolitical or even reactionary. To be sure, there was lot of hemming and hawing, the noticing of the resiliencies of hierarchy, a fascination with postmodernism’s seemingly apolitical turn, and a recognition of the complexities of cooptation, but mostly scholars wanted to locate the radicality in punk rock, the anti-misogyny in Madonna, the dialectical materialism concealed in Dynasty.

The task of recovering (or is it discovering?) renegade politics in culture has not vanished, but it has been superseded recently. Whereas in the 1980s and 90s, the goal was to shed light on the hidden transcripts of how common people fashioned covert politics through cultural means, today the focus of historical scholarship is increasingly to reveal continued subjugation. Studies have moved from glimpsing powerful countervailing energies in surprising places to pinpointing the unsurprising ways in which ruling political and economic actors reassert their power. In the late twentieth century, much cultural history concentrated on the power of politics when masked and hidden in cultural forms; now attention has shifted to unmasking an insidious politics whenever culture might seem to be covering it up.

Christopher J. Smith’s Dancing Revolution: Bodies, Space, and Sound in American Cultural History reads like a long-lost tract from the 1990s, when subcultural and subaltern transgression and resistance were all the rage in American cultural history. Smith, a professor of musicology at Texas Tech University, wants to recover the liberating potential of bodies dancing in akimbo in the streets, on stages, and on screen. “My fundamental premise,” he explains, “is that participatory vernacular dance in the United States, especially dance occurring in public or quasi-public contexts, has been a tool for contesting, constructing, and reinventing social orders” (2). He wants to celebrate the use of noise and motion as political acts compressed into cultural expressiveness. “Drawing on more than four centuries of vernacular dance encounters,” Smith elaborates, “I propose a historical model of street dance as both consciously irruptive and politically representative, while always acknowledging its fraught, racist, and exploitative history” (2). While the latter acknowledgement does not disappear from Dancing Revolution—Smith would never argue that American and global histories are free of suffering—his excitement, sometimes bordering on insistence, is far more about how vernacular dance marks a triumph of political activism. “If we therefore understand ‘akimbo’ motion and ‘rough music’ as representing related, indeed often simultaneous, subaltern defiance,” he writes excitedly, “it becomes possible to see public dance, especially street dance in groups, as likewise a tool of resistance and change” (30).

This argument repeats itself throughout the rest of Smith’s book, to the point that it starts to become rote at times. “For Native Americans subjected to psychological and physical displacement in the early nineteenth century,” Smith believes, “dance became a theological strategy and a revolutionary tactic” (75). “The akimbo nature of bodily motion and facial gesture, which provide a visual counterpoint to the sounding ‘participatory discrepancies’ polyrhythm and syncopation, thus links Baker to a transgressive and rebellious performance tradition,” he argues. “It likewise foreshadows her contributions to the complex oppositional semiotics of the proto-Civil Rights movement” (82). “In the rolling akimbo languages of African American expression,” Smith insists again, “generations of blacks, whites, and creoles, willing or unwilling, welcoming or resisting, have recognized the possibility of previously unimagined renewal. These heightened experiential spaces have also…permitted the possibility for subaltern communities (black, slaves, immigrants, mechanics and apprentices, women, gays, and lesbians), or other populations taking on the temporary mask, to critique, contest, or at the very least complicate dominant paradigms” (108). Smith on the 1960s: “A more nuanced understanding of the meaning of dance within the decade’s social culture, however, entails situating it within political landscapes of liberation: not only the liberation of middle-class white youth—the prototypical baby-boomer hippies—but also that of ethnic minorities, same-sex orientations, and most relevantly, of public spaces” (118).

Smith is so eager to assert the forceful coherency of vernacular dance as revolutionary that his book’s argument can grow a bit brittle, as much of the 1990s cultural history scholarship did in its efforts to convey the power of the powerless, the politics in the pop culture. Nonetheless, Dancing Revolution is filled with wonderful discoveries and potential connections. Over the course of nine chapters, Smith tracks the vernacular dancing body through the “riverine” networks of religion and commerce across the early nineteenth-century Cumberland Plateau in Kentucky and Ohio. He recovers the fascinating transatlantic careers of African-American actors such as Ira Aldridge. He hears the political implications of whistles and shrieks of noisy dance in public spaces. He follows the networks and exchanges of the French-, Afro-, and Celtic/Anglo-Caribbean. We learn about the Shakers and Native American Ghost Dances. Smith uncovers the threat of lower-class and racialized dance movement to class and hierarchy in Abraham James’s 1844 illustration A Grand Jamaica ball! Or the Creolean hop a la muftee; as exhibeted [sic] in Spanish Town. Josephine Baker’s cross-eyed and akimbo dance styles reveal not the fad for exoticism in Europe, but rather Baker’s ability to cut through primitivism with modernist critique by drawing upon Black Diasporic gestural vocabularies. Smith most brilliantly analyzes a striking scene of dance and music in the Marx Brothers’s 1937 film A Day at the Races. At first glance, the scene appears highly racist, but Smith wants to resituate it as a critique of racist norms in America. In his view, the film features virtuosic performances by Harpo Marx, Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers (probably choreographed by the great Frankie Manning), the Chrinoline Choir, and the jazz singer Ivie Anderson (who performed with Duke Ellington’s Orchestra). For Smith, these performances, set within clever camera work, stagecraft, and imaginative musical composition, delivered the rebelliousness of African-American subcultural styles to the mainstream. Smith takes us through the sequence’s many musical, gestural, theatrical, and cinematic references and implications, helping us see the beautiful, challenging, hopeful energies expressed in this dreamlike vision of a liberated, working-class space, grounded in Black culture, exploding from celluloid in the midst of Popular Front, New Deal, Great Depression America.

In Dancing Revolution, we also learn about perceptions of Black dance as proto-revolutionary in texts such as Malcolm X’s autobiography or films such Spike Lee’s underappreciated Bamboozled. Civil rights marches, hippie dance in the counterculture, Stonewall’s queer chorus line protests, punk rock mosh pits, and hip hop’s b-boy dancers follow, each demonstrating further iterations of protest expressed in gestural, cultural form. Smith ends with more recent moments of dance as politics: protesters tangoing against authoritarianism in Turkey’s Gezi Park and an appearance by Sir Mix-a-Lot along with a diverse group of women dancing to his hit song “Baby Got Back” at a Seattle Symphony “Sonic Encounter.” Recent cultural historians would likely point out that the tangoers were ultimately crushed by the ruling Turkish regime—so much for revolutionary dancing. And they might dismiss the latter event with Sir Mix-a-Lot as clear evidence of offensive appropriation or problematic cooptation. By contrast, Smith chooses to interpret these stories as dazzling instances of incipient revolution, moments when dance gestures forged during the injustices of the past resurfaced as challenges to undemocratic control by governments or bourgeois norms of decorum.

How does Smith get there? Throughout Dancing Revolution, we hear much about “body creolization,” “subaltern expression” (66, I counted at least twenty uses of the term in the book), “syncretic movement expression” (150), “nonnormative, potentially transgressive” dance (108), and Michel de Certeau’s concept of “the space of a tactic” as the “space of the other” (56-57). Smith brings together an impressive array of theoretical methods, ranging from his own training in musicology and ethnomusicology to approaches drawn from visual studies, semiotics, literary studies, and history. Perhaps most of all, he wishes to track long sweeps of gestural continuity across time and place in the Americas (with a bit of transatlantic attention). There’s that arm gesture again. There is that use of the torso. There is that syncopation. Here’s the harlequin trickster manifesting again as a blackface minstrel. There once again is that sacred use of the body, whether in a Protestant Great Awakening or Catholic or Diasporic African context. Here is that circle of street corner or dancefloor communal formation known in various guises as the crowd, the U, or the cypher.

Numerous close readings of source material are profoundly illuminating, but Smith does miss one promising theoretical point that he might have brought to the surface in Dancing Revolution. In arguing that both dance and music were, as de Certeau evocatively wrote, “the space of a tactic,” Smith might have made more of the etymological links between tactics and the tactile. Both dance and music are bodily forms of expression, giving physical, vibratory form to abstract ideas. Dance and music lend voice, muscle, and bone to the intellect. By restricting his focus, as much late twentieth-century cultural history did, to the politics of culture, Smith misses an opportunity to map out the broader significance of dance. This would mean not merely noting when people engage in dancing revolution, but more expansively when they use dancing and music for thinking. Eager to frame culture as a compensatory form of politics, Smith goes down what perhaps became a dead end for cultural history. His book contains traces of cultural studies doyen Stuart Hall’s infamous put down. “Popular culture,” Hall wrote, “is one of the sites where this struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is the stake to be won or lost in that struggle. That is why ‘popular culture’ matters. Otherwise, to tell you the truth, I don’t give a damn about it” (Hall, “Notes on Deconstructing ‘the Popular’” in People’s History and Socialist Theory, ed. Raphael Samuel (Boston: Routledge, 1981), 239). Smith would not go as far as Hall. In Dancing Revolution, he still gives a damn about vernacular dance in of itself. But he most of all insists that there is a potent politics to be recovered from sources that today are more often interpreted merely as expressing hateful denigration or patronizing appropriation. If you can just harness the right theories and methods to see and hear the emancipatory politics within the culture, Smith believes, the larger dance of revolution might commence from the many smaller acts of dancing revolution. The question remains: will it? Or is studying culture as compensatory politics merely another act of constraining its full whirl of significance?

Ann Powers, music critic at National Public Radio, is up to similar aims as Smith in her book Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music, but she wants not only to notice the politics of dance and music, but also track the fraught and sweeping history of the erotic in American life and culture, as expressed in its popular music and dance. “Taking the turn-on seriously,” she contends, “is the point.” For Powers, “every moment’s pleasure illuminates whole worlds of need, conflict, and possibility, and in its own way, sets the stage for the next” (xxv). In her approach to cultural history, “Music allows people—players, dancers, observers—to ride the storm that arises when desire encounters the roadblocks of prejudice, moral judgment, or cruel circumstance.” Although “American eroticism wants to be easy,” Powers emphasizes how “for most of history, American life has been hard. Our music grinds pleasure from hardship. It creates whirlwinds but also provides a means to manage them” (xxv). By expanding from music and dance culture as merely compensatory politics to treating them as modes of exploring the erotic in American life, Powers offers a potential pathway forward for the cultural historical methods of the 1980s and 90s. Hers is an explicitly feminist perspective that troubles the distinctions between the private and the public. This is a boundary that Smith seems oddly keen to maintain, contending that vernacular dance is most political only when taking place in public settings or with explicit public intentions. With the second-wave feminism trope that “the personal is political” guiding her work, Powers cracks open the distinction.

Popular music in particular cuts across the line between the private and the public, the personal and the political. Over the course of eight chapters and with a critic’s touch for turning a phrase, Powers takes us through how it has done so in different settings, with different figures, in different contexts. She begins with the fraught, racialized sexual interactions of ballrooms in antebellum New Orleans. Then she moves to the smoky clubs of shimmying, shaking bodies in the early twentieth century. She probes negotiations of the erotic in the sacred-secular dynamics of gospel music. In a particularly brilliant chapter, she identifies the embrace of doo-wopian nonsense—”dip dip dip dip dip”—as a means for making sense of adolescent sexuality in postwar America. Powers investigates the search for sexual liberation in the counterculture and the subsequent systemization and routinization of countercultural energies in the groupie system of 1970s rock and the synthetic beats of disco. She notes the musical response to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and the rise of a more masturbatory “self-pleasuring power” realm of fantasy in Madonna’s music video fame (272) as well as Prince’s cultivation of a “Reagan-era safe-sex outrageousness” (275). Powers ends with an exploration of the digital and cyborgian enactments of the erotic by Britney Spears, Beyoncé Knowles, and other more recent pop stars.

It is not that these topics are apolitical to Powers, but rather that they represent specific instances of music serving as a medium for thinking as well as protesting. This shift makes her book a promising model for future historical inquiry. Good Booty is neither obsessed only with recovering hidden political agencies, nor focused merely on condemning the continued domination of marginalized peoples. Instead, it listens and looks to music and dance as mediums through which Americans have navigated both the politics and the intellectual dimensions of the erotic. The very name of the book points to this tantalizing approach. Good Booty takes its name from the original, but ultimately excised, lyrics to Little Richard’s breakthrough hit, “Tutti Frutti.” The original phrase was a ribald allusion to anal sex that the rock and roll architect and his musical collaborators chose to remove from the recorded version of the song. This allowed the tune to circulate more widely than just through the nightclub circuit of the South in which Little Richard first made his name. As the song migrated in recorded form to radio, and as it was covered by white performers such as Pat Boone, “Tutti Frutti” became a vaguer, but also a more potent celebration not merely of the libidinal, but of the more capaciously physical experience of joy and energetic release, including the demand for liberation and mysterious but forceful call for fulfillment and satisfaction. The song’s turn to nonsense—”a wop bop a loo bop a lop bam boom!”—encompassed and intensified its sensory impact and its expressive but elusive semantic sense.

At the same time, as Powers points out, in disappearing from the recorded version of the song, the phrase “good booty” also reminds us of the shadow story of popular music’s celebrations of the erotic: its economic context. Little Richard’s celebration of the erotic, she evocatively writes, emerged in “the realm of commerce and plunder, of booty earned and stolen” (xxiv). And in doing so, the music produced vexations alongside its pleasures. To consider the “good booty” in popular music means also noticing how it has always arrived within the processes of a racialized and misogynist capitalism. This is true from the earliest days of Atlantic World colonialism and forced human bondage to more recent examples of Atlantic Records (or in Richard’s case, Specialty Records) copyright expropriation. Who gets to cash in on music’s erotic touch is a major issue. Nonetheless, for Powers it is less the contestation over the commercialization of pop music than it is the underlying physical and intellectual explorations of the erotic that is most central, most worth cultural history’s attention. “What Watson encountered,” she writes of Methodist layman preacher John F. Watson, who in 1819 was troubled by expressions of ecstatic religious fervor during the Second Great Awakening, “was an erotic exchange that’s at the heart of American popular music” (xvii). For Powers this exchange is not merely about sexual arousal, but a more expansive understanding of anima, of the “animating spirits, the ineffable mobilizing forces that make people feel alive” (xvi). “This method,” Powers continues, “of sharing and communicating the most personal, difficult to articulate, and indeed intimate aspects of the human experience has been taken up by every kind of American as a conduit for both joy and pain” (xvii). To Powers, this “taking up” is not just narrowly political in nature, but all-encompassingly social. It is not just about dancing revolution, but about thinking through the dilemmas and possibilities of human lives, from their most profane levels to their most sacred aspirations. “From the beginning,” she contends, “music’s ability to open people to each other also made it an avenue for exploitation, and a kind of theater where Americans acted out the ways they violated and oppressed one another and dreamed up ways they might heal those wounds” (xvii). This is a bigger story, more difficult to track and explicate than just focusing on political resistance in cultural form. Politics is part of it, but, as Powers points out, “the erotic as a force in music is rarely discussed in these more complicated terms. Instead, it’s the subject that makes people squirm” (xvii).

Squirming occurs because of sexuality; so too, Americans squirm when trying to reckon with the racism that is shot through the nation’s history. Because what Powers calls “African fundamentals” were absorbed into “the very core of American cultural expression,” then appropriated by white Americans, popular music registers the fraught nature of America’s racist death drive alongside its erotic life force (xxiii). This has allowed music and dance to serve as openings for subaltern politics, as Smith would contend, but in Powers’s framework, music also becomes a far more wide-ranging vehicle for capacious thinking. The temporary resistances of the subaltern become potentially permanent critiques. “In every era,” Powers concludes, “expressing the erotic through music has required Americans to confront the ways in which this culture is grounded in exploitation and violation as well as democratic openness and liberty.” In “the sex scenes of American music,” Powers wants us to hear and see “the most intimate cruelties we have wrought upon each other, alongside the pleasures and kindnesses” (xxiii).

In sum, both authors ask us to go back to the cultural history methods that emerged just before our own time, when a more Gramscian mode of reading counterhegemony in culture took hold than what now predominates, which is noticing domination everywhere you look and listen for it. Both books ask us to consider what might be lost in the shift away from the cultural historical approach of a few decades ago. Their books diverge, however, in how they address this task. Smith seeks to excavate a compensatory class and race politics from subaltern cultural expression. He uses abstract theories of how culture works to do so. For him, politics occurs by cultural means when normative avenues for political action are blocked. If you can’t pass laws in the halls of Congress, you can at least dance in the streets. Dancing revolution occurs when people cannot enact it by more conventional political means. Smith uses a robust set of interdisciplinary scholarly analytic tools to map out this recurring theme: here, there, and everywhere across vastly different historical settings and moments are bodies responding rebelliously to efforts at control of them. Under pressure and constraint, terror and domination, they move vigorously and defiantly, they noisily refuse to be subdued, they thrust out limbs, gyrate torsos, shimmy shoulders, let their backbones slip, pump their pelvises, and shake their asses. Sometimes their efforts appear in religious fervor, other times behind the mask of commercial blackface minstrelsy. Sometimes they gesture to revolution on the dance floor, other times directly in the streets. While they may not be able to overthrow the powers that be, Smith wants to honor their dancing as a mode of politics-by-another-means, a weapon of the weak—the return not of the repressed, but rather of the irrepressible.

It is Powers’s approach, however, that is ultimately the more intriguing. She reorients the study of culture from a form compensatory politics to the more far-reaching, and deeply felt, question of the erotic. Addressing popular music not only as politics by another means, but also as an investigation of the erotic that, crucially, includes intellectual activity, Powers pays attention to how music has served as a way for people not just to resist, but more generally to think. This allows her to broaden her story from how politics gets displaced into culture to a more important tale of how individual bodies and the body politic collide in popular music and dance. In doing so, they confound the very boundaries between the personal and the political, the private and the public. Powers proposes that a fuller sense of the past involves treating culture not merely as another lever of domination, nor only as an embodiment of resistance, but instead as erotically intellectual inquiry. And by imagining intellectual inquiry as a part of erotic life rather than something removed from it, her book suggests that acts of movement and sound-making are nothing less than the sources from which both the cultural and the political emanate.

April 27, 2021

2021 May 22—Dylan@80 Virtual Conference

On the occasion of Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday and the publican of The World of Bob Dylan, ed. Sean Latham (Cambridge University Press, 2021), I will be speaking on a panel about conducting research in the Bob Dylan Archive for an essay in the volume about Dylan and the 1960s counterculture. My brief talk is titled:

“One Should Never Be Where One Does Not Belong’: The Elusive Magical Mysteries of John Wesley Harding“

05/22/21: Dylan@80 Virtual Conference

On the occasion of Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday and the publican of The World of Bob Dylan, ed. Sean Latham (Cambridge University Press, 2021), I will be speaking on a panel about conducting research in the Bob Dylan Archive for an essay in the volume about Dylan and the 1960s counterculture. My brief talk is titled:

“One Should Never Be Where One Does Not Belong’: The Elusive Magical Mysteries of John Wesley Harding“

Test. Photo: Michael J. Kramer

Test. Photo: Michael J. Kramer