Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 31

August 27, 2021

Syllabus—Reading and Writing Across Forms

Jeff Wall, After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, 1999-2000.Overview

Jeff Wall, After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, 1999-2000.OverviewHow do we more effectively and compellingly read, interpret, and analyze different forms of expression? What is “form,” anyway? A slave narrative, a speech, an essay, a court ruling, a novel, a poem, a music album, a film, visual art, the built environment, journalism, online social media, computational data: the world is filled with different kinds and types of material, information, styles, genres, expectations, and modes of communication. Beginning with this year’s common reading, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, we shall explore how to analyze these different forms, probing what it means to receive, describe, interpret, critique, and write about each one clearly and convincingly. We will also experiment with different forms of expression ourselves, from short analytic essay responses to social media documentation to oral presentation and discussion to a longer, comparative final essay that includes an option for digital, multimedia, or data-driven component.

Course MaterialMaterials are available for purchase at Brockport Bookstore or on reserve at Drake Library Reserve Desk. Some materials also available on course website.

RequiredJohn Stauffer and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., eds., The Portable Frederick Douglass (New York: Penguin, 2016)Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (New York: Random House, 1952)Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, ed., How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012)Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014)Plessy v. Ferguson Opinion of the Supreme Court and Dissent (1896) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Opinion of the Supreme Court (1954), available onlineFreedom’s Ring website, available online at https://freedomsring.stanford.edu/Map... Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America website, available online at https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/red... Gaye, What’s Going On (Detroit: Motown Tamla, 1971), available onlineDo The Right Thing, dir. Spike Lee (Forty Acres and a Mule/Universal Pictures, 1989), available onlineLearning GoalsUse effective critical thinking and writing skills to express complex ideas clearlyproduce, revise, and improve coherent texts within common college-level written forms, including an analytical essay requiring independent research analyze social conflicts, prejudices, and/or intolerance relevant to a contemporary setting, and arising from such issues as racism, ethnicity, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, class, etc.demonstrate relevant knowledge of scholarship on womendevelop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluated an oral presentation according to established criteriaEvaluationStudent info and course contract – 5%Douglass response – 10%Ellison and Supreme Court rulings response – 10%National Council for Public History Instagram takeover – 10%Taylor or Rankine response – 10%Marvin Gaye, Spike Lee, Freedom’s Ring, or Mapping Inequality response – 10%Final essay – 25%In-class presentations and participation – 20%ScheduleThe instructor may adjust the schedule as needed during the semester, but will give clear instructions about any changes.

Week 0108/30: Introductions — Collect summer assignment09/01: Gates, Jr., “What is An African American Classic?” and Stauffer and Gates, Jr., “Introduction,” in Portable Frederick Douglass09/03: Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Ch I-IV, pp. 1-31Week 0209/06: No class, Labor Day09/08: Douglass, Narrative, Ch V-X, 32-82Due 09/08: Student info and course contract09/10: Douglass, Narrative, Ch XI-Appendix, 82-100Week 0309/13: Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka09/15: Ellison, Invisible Man, Prologue, Chapters 1 and 209/17: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 3 and 4; Douglass, “The Color Line (1881), 501-512Due 09/19: Douglass response (see assignments for prompt)Week 0409/20: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 5 and 609/22: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 7 and 809/24: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 9 and 10; Douglass, “Letter From the Editor (On the Burning Down of His Rochester House) (1872),” 495-497Week 0509/27: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 11 and 1209/29: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 13 and 1410/01: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 15 and 16Week 0610/04: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 17 and 18; Douglass, “Toussaint L’Ouverture (ca. 1891),” 527-53710/06: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 19 and 2010/08: Ellison, Invisible Man, Chapters 21 and 22; Douglass, “The Future of the Colored Race (1886),” 513-516Week 0710/11: Ellison, Invisible Man, Section 23 and 2410/13: Ellison, Invisible Man, Section 2510/15: Ellison, Invisible Man, Section 26Week 0810/18: No class, fall break10/20: Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, Introduction, The Combahee River Collective statement10/22: Taylor, How We Get Free, Barbara Smith, Beverly SmithDue 10/24: Ellison and Supreme Court rulings response (see assignments for prompt)Week 0910/25: Taylor, Demita Frazier, Alicia Garza, Comments by Barbara Ransby and Douglass, “Woman Suffrage Movement (1870)”10/27: Rankine, Citizen, Ch. 1 and 210/29: Rankine, Citizen, Ch. 3 and 4Week 1011/01: Rankine, Citizen, Ch. 5 and 611/03: Rankine, Citizen, Ch. 711/05: Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? (1852),” 195-222Week 1111/08: Drake Library Introduction (meet at Drake Library)11/10: NCPH Instagram Takeover (possible visit from Dr. Bruce Leslie)11/12: NCPH Instagram TakeoverWeek 12Due 11/15: NCPH Instagram Takeover Week photos and writeups (see assignments for prompt)11/15: Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On, Side 0111/17: Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On, Side 0211/19: OpenDue 11/21: Taylor or Rankine response (see assignments for prompt)Week 13 – Thanksgiving – No MeetingsWeek 1411/29: Spike Lee, Do The Right Thing, First half of film12/01: Spike Lee, Do The Right Thing, Second half of film12/03: Spike Lee, Do The Right ThingWeek 1512/06: Freedom’s Ring website12/08: Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America website12/10: Reflections and Wrapping upDue 12/12: Marvin Gaye, Spike Lee, Freedom’s Ring, or Mapping Inequality response (see assignments for prompt)Final – 12/17Final essay due (see assignments for prompt)Syllabus—Modern America

Ms. Eastine Cowner, a former waitress, in her job as a scaler, constructing the Liberty Ship SS George Washington Carver, launched on May 7, 1943 during World War II. Photo: E. F. Joseph, US Office of War Information.Overview

Ms. Eastine Cowner, a former waitress, in her job as a scaler, constructing the Liberty Ship SS George Washington Carver, launched on May 7, 1943 during World War II. Photo: E. F. Joseph, US Office of War Information.OverviewModern America provides an in-depth exploration of the history of America since the Civil War. Through interactive multimedia lectures, readings, discussion, and writing, students analyze the struggles of diverse communities over wealth, rights, and authority in the United States. How did the historical experiences of a wide range of Americans shape systems of power, patterns of resistance, and socio-political identities during a period that saw the nation’s emergence as a global power? The course develops skills in critical close reading, historical thinking and contextualization, oral communication, project management, and effective writing.

Course MaterialEric Foner, Give Me Liberty! An American History Volume 2 Brief Sixth Edition. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2020.Eric Foner, Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History Volume 2 Sixth Edition. WW Norton & Company, 2020.Learning GoalsThe study of history is essential. By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills that will help you lead purposeful lives, exercise responsible citizenship, and achieve career success.

History Department Learning GoalsArticulate a thesis (a response to a historical problem)Advance in logical sequence principal arguments in defense of a historical thesisProvide relevant evidence drawn from the evaluation of primary and/or secondary sources that supports the primary arguments in defense of a historical thesisEvaluate the significance of a historical thesis by relating it to a broader field of historical knowledgeExpress themselves clearly in writing that forwards a historical analysis.Use disciplinary standards (Chicago Style) of documentation when referencing historical sourcesStudents will identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ workStudents will write and reflect on the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with multiple opportunities for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedbackStudents will demonstrate understanding of the methods social scientists use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of interpretive analysisStudents will demonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of historyStudents will develop proficiency in oral discourse and evaluate an oral presentation according to established criteriaGeneral Education Learning GoalsSocial Science (S)Students will demonstrate understanding of the methods social scientists use to explore social phenomena, including observation, hypothesis development, measurement and data collection, experimentation, evaluation of evidence, and employment of mathematical and interpretive analysis. Students will develop their understanding of methods and their skill in using them through daily class discussions that connect information from primary sources to the larger events of which they formed a part, and through writing of four interpretive papers which address the same goals in a more formal, written formStudents will demonstrate knowledge of major concepts, models and issues of at least one discipline in the Social Sciences. Students will be introduced to these through direct encounter with secondary sources and through classroom presentation and discussion of sameStudents will identify, analyze, and evaluate arguments as they appear in their own and others’ work. Each of the four written essay assignments requires this Students will write a short paper or report reflecting the writing conventions of the disciplinary area, with at least one opportunity for feedback and revision or multiple opportunities for feedback. All of the assigned papers reflect the writing conventions of the discipline. At least one paper will be presented for student feedback prior to submission of the final draft Diversity (D)Students will demonstrate an understanding of:

how systems of power and privilege and histories of oppression and activism have informed current social identities how identity categories and systems of power intersecthow bias impacts political, economic and social practices EvaluationAssignment 01—Student Info Card and Course Contract = 5%Assignment 02—Primary Source Analysis: Closely Reading, Contextualizing, and Interpreting Historical Evidence = 5%Assignment 03—Primary Source Analysis and the Art of the Topic Sentence = 5%Assignment 04—Citation: Hey, Who Said That? = 5%Assignment 05—Secondary Source Analysis, or “Historiography”: The Art of Paraphrasing = 5%Assignment 06—Secondary Source Analysis and the Art of the Introduction, Thesis Statement, and Conclusion = 5%Assignment 07—Final Essay Proposal = 5%Assignment 08—History Art Response = 5%Final Essay—Bringing It All Together = 15%InQuizitives 2%×15 = 30%Attendance and Participation (at least one constructive comment per class = full credit; occasional constructive comments = most credit; attentive presence = some credit) = 15%Extra credit:Monthly history encounters (3 total) = B+ and above on one assignment gives you a half-step improvement on one short writing assignment from semester; B+ and above on two assignments give you half-step improvement on final essay; B+ and above on all three assignments raises final grade half step (B+ to A- for instance). These cannot be completed after due dates.–OR–Brockport Faculty Historians Essay = B+ and above will raise final grade two steps (B+ to A for instance)ScheduleWeek 01 — Planting A Flag in Modern America08/30: Planting a Flag in Modern America09/01: Is Reconstruction Unfinished? America After the Civil War, 1865-1877Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Table of Contents,Preface, xix-xxviiiGive Me Liberty!, Chapter 15, “What Is Freedom?”: Reconstruction, 1865-1877, 437-46809/03: Discussing Frederick Douglass, “The Composite Nation”Readings due by class:Frederick Douglass, “Composite Nation” (1869), Voices of Freedom, Ch. 15, No. 100Week 02 — Is Reconstruction Unfinished? America After the Civil War, 1865-187709/06: No class, Labor DayDue 09/07: Assignment 01—Student Info and Course ContractDue 09/07: Inquizitive—How To Use InquizitiveDue 09/07: Inquizitive—Chapter 15 (https://digital.wwnorton.com/givemeli.... Then, be sure to log in to our student set (487752)09/08: Is Reconstruction Unfinished? America After the Civil War, 1865-1877Readings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 15, “What Is Freedom?”: Reconstruction, 1865-1877, 437-46809/10: Reconstruction discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 15Martin Pengelly, “A disputed election, a constitutional crisis, polarisation…welcome to 1876” (interview with Eric Foner), The Guardian, 23 August 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2... Brockport Faculty Reading: John Daly, “The Southern Civil War 1865-1877: When Did the Civil War End?” (on Canvas)Week 03 — America’s Gilded Age, 1877-1890Due 09/13: Inquizitive—Chapter 1609/13: The Hog Squeal of the Universe: Industrialization, Commodification, and UrbanizationReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 16, “‘America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890,” 447-50509/15: Where Does the Weekend Come From? Americans Respond to IndustrializationReadings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 16, “‘America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890,” 447-50509/17: Gilded Age discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 16, 28-52, pay particular attention to Carnegie (104), Second Declaration of Independence (106), George (107), and Saum Song Bo (109, especially in relation to Douglass, “The Composite Nation”)Week 04 — Freedom’s Boundaries, At Home and Abroad, 1865-1900Due 09/20: Assignment 02—Primary Source Analysis: Closely Reading, Contextualizing, and Interpreting Historical EvidenceDue 09/20: Inquizitive—Chapter 1709/20: From US Settler Colonialism to Formal EmpireReadings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 16, “America’s Gilded Age, 1870-1890,” The Subjugation of the Plains Indians-Myth, Reality, and the Wild West, pp. 493-501Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 17, “Freedom’s Boundaries, at Home and Abroad, 1890-1900,” 508-53909/22: The Nadir: Jim Crow09/24: Freedom’s Boundaries discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 17, 53-74, pay particular attention to Du Bois (113), Wells (114), and Aquinaldo (117)Hopi Petition Asking for Title to Their Lands (1894), scroll down to read the transcription, especially p. 7, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/d...Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884), Syllabus (full case optional if you are interested), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/fede... 05 — The Progressive Era, 1900-1916Due 09/27: Inquizitive—Chapter 1809/27: Did the Progressive Era Make Progress? Part 1Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 18, “Chapter 18: The Progressive Era, 1900-1916,” 540-57109/29: Did the Progressive Era Make Progress? Part 210/01: Progressive Era discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 18, 75-103, pay particular attention to Ryan (120), Sanger (122), and Wilson (124)Optional: Various Authors, “Suffrage at 100,” New York Times, 2019-2020, https://www.nytimes.com/spotlight/wom... Brockport Faculty Listening: Elizabeth Garner Masarik, “100 Years of Woman Suffrage,” Dig! A History Podcast, 5 January 2020, https://digpodcast.org/2020/01/05/wom... 06 — Safe for Democracy? The Great War and Its Aftermath, 1916-1920Due 10/04: Extra credit monthly history encounters (inspired by Dr. Chelsea Gibbon, optional)Due 10/04: Inquizitive—Chapter 1910/04: The Wartime State and Its Aftermath: Making the World Safe for Democracy?Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 19: Safe for Democracy: The United States and World War I, 1916-1920, 572-60510/06: Safe for Democracy discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 19, 104-133, pay particular attention to Bourne (106, in relation to Douglass, “The Composite Nation)10/08: Open (possible meeting at Drake Library about citation and Drake Library resources)Week 07 — From Business Culture to Great Depression in the “Roaring” Twenties, 1920-1932Due 10/11: Assignment 03—Primary Source Analysis and the Art of the Topic SentenceDue 10/11: Inquizitive—Chapter 2010/11: What Made the “Roaring” Twenties Roaring? Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 20, 1920-1932: From Business Culture to Great Depression in the “Roaring” Twenties, 606-63610/13: From Roaring Twenties to Great Depression10/15: “Roaring” Twenties discussion — Citation discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 20, 134-159, pay particular attention to Congress Debates Immigration (138) and Hill and Kelley Debate the ERA (1922)Week 08 — The New Deal, 1932-194010/18: No class, fall breakDue 10/20: Inquizitive—Chapter 2110/20: FDR’s New Deal and the Making of Modern LiberalismReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 21: The New Deal, 1932-1940, 637-66910/22: New Deal discussion — Citation discussionReadings due by class:Foner, ed., Voices of Freedom, Chapter 21, 160-186, pay particular attention to FDR (145), Hoover (146), Hill on Indian New Deal (148)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Anne S. Macpherson, “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938– 1941,” Journal of American History 104, 3 (December 2017), 656-680 (on Canvas)Week 09 — Fighting for the Four Freedoms: World War II, 1941-1945Due 10/25: Assignment 04—Citation: Hey, Who Said That?Due 10/25: Inquizitive—Chapter 2210/25: Was World War II the Actual New Deal?Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 22: Fighting for the Four Freedoms: World War II, 1941-1945, 670-70410/27: The American Century? The USA at MidcenturyReadings due by class:Foner, ed., Voices of Freedom, Chapter 22, 187-207, pay particular attention to Luce, American Century (152) and Wallace, Century of the Common Man (153)10/29: WWII discussionReadings due by class:Foner, ed., Voices of Freedom, Chapter 22, 187-207, pay particular attention to FDR on the Four Freedoms (150), WWII and Mexican Americans (155), and Jackson, Dissent in Korematsu (157)Week 10 — The Cold War at Abroad and at Home, 1945-1960Due 11/01: Extra credit monthly history encounters (optional)Due 11/01: Inquizitive—Chapter 2311/01: Cold War ContainmentsReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 23: The United States and the Cold War, 1945-1953, 705-733Due 11/03: Inquizitive—Chapter 2411/03: Cold War RebellionsReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 24: An Affluent Society, 1953-1960, 734-76511/05: Cold War discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 23, 208-239, pay particular attention to The Truman Doctrine (159) and Lippmann, A Critique of Containment (161)Voices of Freedom, Chapter 24, 240-263, pay particular attention to Mills (171)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Bruce Leslie (and John Halsey), “A College Upon a Hill: Exceptionalism & American Higher Education,” in Marks of Distinction: American Exceptionalism Revisited, ed. Dale Carter (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2001), 197-228 (on Canvas)Week 11 — Abundance and Its Discontents, 1960-1969Due 11/08: Inquizitive—Chapter 2511/08: A Second Reconstruction? The Modern African-American Civil Rights MovementReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 25: The Sixties, 1960-1968, 766-802Optional: Keisha N. Blain, “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Dauntless Fight for Black Americans’ Right to Vote,” Smithsonian Magazine, 20 August 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/histor... The Great Society and the Quagmire of the Vietnam War: The “Sixties”Readings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 25: The Sixties, 1960-1968, 766-80211/12: Civil Rights and the “Sixties” discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 25, 264-297, pay particular attention to Goldwater (1964), Port Huron Statement (178)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Meredith Roman, “The Black Panther Party and the Struggle for Human Rights,” Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men 5, 1, The Black Panther Party (Fall 2016), 7-32 (on Canvas)Week 12 — Disco Demolitions and the Rise of the New Right, 1970-1989Due 11/15: Assignment 05—Secondary Source Analysis, or “Historiography”: The Art of ParaphrasingDue 11/15: Inquizitive—Chapter 2611/15: Disco Demolition: The 1970s From Watergate to the Malaise SpeechReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 26: The Conservative Turn, 1969-1988, 803-83911/17: The Reagan Revolution: Modern Conservatism as Revolution—The Rise of the New RightReadings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 26: The Conservative Turn, 1969-1988, 803-83911/19: 1970s/1980s discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 26, 298-322, pay particular attention to Commoner (184), Blakemore (185), Carter (186), Reagan (190)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: Michael J. Kramer, “The Woodstock Transnational: Rock Music & Global Countercultural Citizenship After the Vietnam War,” Talk Delivered at Music and Nations III: Music in Postwar Transitions (19th-21st Centuries), Université de Montréal, 21 October 2018, based on material in the book The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), https://www.michaeljkramer.net/the-wo... Week 13 – Thanksgiving – No MeetingsWeek 14 — Between Two Falls: From the End of the Cold War to the Great Recession, 1989-2008Due 11/29: Assignment 06—Secondary Source Analysis and the Art of the Introduction, Thesis Statement, and ConclusionDue 11/29: Inquizitive—Chapter 2711/29: The 1990s: An Era of UncertaintyReadings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 27: From Triumph to Tragedy, 1989-2004, 840-87912/01: The End of the American Century? The 2000 Election, 9/11, the War on Terror, and the 2008 Great RecessionReadings due by class:Review Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 27: From Triumph to Tragedy, 1989-2004, 840-87912/03: 1990s/2000s discussionReadings due by class:Voices of Freedom, Chapter 27, 323-340, pay particular attention to Clinton on NAFTA (192), Oro and Los Tigres del Norte (195)Optional Brockport Faculty Reading: James Spiller, “Nostalgia for the Right Stuff: Astronauts and Public Anxiety about a Changing Nation,” in Michael Neufeld ed., Spacefarers: Images of Astronauts and Cosmonauts in the Heroic Era of Spaceflight (Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2013), 57-76Week 15 — Is America “Post” Modern Now?, 2008-2020Due 12/06: Assignment 07— Final Essay ProposalDue 12/06: Extra credit monthly history encounters (optional)Due 12/06: Inquizitive—Chapter 2812/06: From the Great Recession to Make America Great Again, 2008-2020Readings due by class:Give Me Liberty!, Chapter 28: A Divided Nation, 2001-2020, 880-92112/08: 2010s DiscussionVoices of Freedom, Chapter 28, 341-358, pay particular attention to Kennedy, Obergefell v. Hodges (199), Obama, Eulogy (201)Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/... 12/10: Assignment 08—History Art Response12/10: Is America Modern Yet? A Concluding DiscussionFinal – 12/17Final essay dueExtra credit Brockport Faculty Historians Essay (optional)August 22, 2021

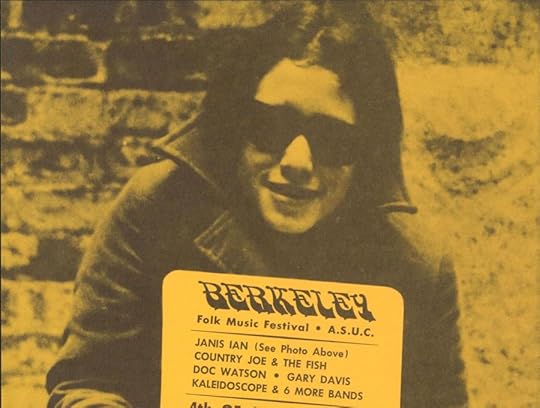

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction, a new digital exhibit, is now published at https://sites.northwestern.edu/bfmf/.

It’s a multimedia exploration I curated of an understudied but important folk festival that took place at the University of California-Berkeley between 1958 and 1970. For aficionados and newcomers alike, you can enjoy images, sound, video, and a written historical narrative about the Festival and its significance.

Working with the ace folks at Northwestern University Libraries on this project has been a pleasure. The effort has been years in the making, with more to come. Look for multimedia essays, an audio podcast, and an in-person gallery exhibition in the near future.

Numerous students have also worked on the project over the years, including Olivia Langa at SUNY Brockport; Julia Popham, Jacob Skaggs, and Sarah Bruyere at Northwestern University; and students in classes I’ve taught at Northwestern, Middlebury College, and Brockport. Kudos for your labor on the project!

Additionally, I have been greatly aided by Deborah Robins, Alice Stuart, Dev Singh, Barbara Dane, Neil Rosenberg, Ron Cohen, Robert Cantwell, Odette Pollar, Brian Miksis, Jesse Jarnow, Corry Arnold, Sandy Rothman, Chris Strachwitz, and countless others.

Most of all big praise to the Big O, Barry Olivier, director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Barry, we hear your baritone voice, joyful laugh, and good organizational energies streaming down the digital river of song from then to now to the future.

To visit the digital exhibit: The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction.

August 13, 2021

Coming Fall 2021—Extensive Digital Exhibit About the Berkeley Folk Music Festival

Pete Seeger performs at the University of California-Berkeley’s Greek Theater during the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.

Pete Seeger performs at the University of California-Berkeley’s Greek Theater during the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival.Coming fall 2021, the digital exhibit The Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Folk Revival on the US West Coast—An Introduction takes a look at and listen to the history of an understudied part of the 1960s folk revival. Taking place on the University of California-Berkeley campus between 1958 to 1970, the Berkeley Festival featured many of the most famous performers from the era, from Joan Baez and Pete Seeger to Doc Watson and Mississippi John Hurt to rock bands such as the Jefferson Airplane and Country Joe and the Fish. Countless other musicians appeared at the event as well, from norteño band Los Tigres Del Norte as its members were just starting out on their successful career to Woody Guthrie’s running buddy Cisco Houston at the tail end of his life. Curated by historian Michael J. Kramer, the multimedia exhibit features photographs, posters, ephemera, audio recordings, and video clips as well as an extensive narrative text that contextualizes the event within the cultural history of the post-World War II era in California and the United States as a whole.

August 2, 2021

History Is Not the Past

History is not the past. History is a story about the past, told in the present, and designed to be useful in the constructing of the future.

…History is picked at, scraped down, patched up, and encrusted with new ornament.

…History begins in the will of the historian, a forked mortal trapped in the unknowable flux. The courageous act of history is the act of the historian who ignores most people and events while selecting a tiny number of facts and arranging them artfully and truthfully in order to speak usefully about the human condition.

…History is intangible, a phantom of the mind, yet it is distanced from the dream of the self. History is a variety of imaginative literature, yet it shuns fancy for fact. As in making things, in thinking history, the real, the true is manipulated, arranged, made useful, accepted, made proof. Like artifacts, history depends on the individual for existence, but like the artifact, it is drawn from the world beyond the self, then pushed back into that world for objective evaluation.

…There is only one past but many histories. We think of one of them—our own—as ‘history’ and the others as ‘folk histories,’ but they are either all histories or all folk histories. All involve collecting facts about the past and arranging them artfully to explore the problems of the present.

…The reason to study people, to order experience into ethnography, is not to produce more entries for the central file or more trinkets for milord’s cabinet of curiosities. It is to stimulate thought, to assure us there are things we do not know, things we must know, things capable of unsettling the world we inhabit.

Henry Glassie

Rethinking “Rethinking Graduate Education”

What do we do when the elite members of a profession abandon the profession?

This is the problem with Philip J. Deloria’s recent Organization of American Historians President’s Column, “Rethinking Graduate Education,” published in The American Historian magazine. Deloria embraces the idea that history doctoral programs should teach “disciplinary expertise applicable to all social sectors,” as Robert Weisbuch and Leonard Cassuto argue in the 2016 Mellon Report, Reforming Doctoral Education. Rather than train historians for teaching and research history itself, Deloria wants to know “what would it look like if we imagined ‘flooding the zone’ of the United States with advanced-degree historians?” He continues with a list of the most expected, unsurprising, so-called “disruptive” ideas for transformation. Many sound good, and indeed are good, but the questions of how they would actually work, who would run them, and on what terms, and the kinds of labor practices to which they acquiesce remain alarmingly vague, concealed behind the legerdemain of flashy higher education “innovations.” Sadly, the proposals Deloria offers seem designed more to please administrators and boards of trustees outside the profession, or maybe self-satisfied elites within it, than actually help aspiring students have the time and resources to study history deeply and probingly in service of the public good. Seeking to save the historical profession, the recommendations in Deloria’s column may well destroy it. Here are some of the shifts in graduate education he waves before our eyes:

Reduce time to degree to four years. Throw out the comprehensive exam structure and replace it with a portfolio demonstrating broad expertise. Connect the historical toolkit with real quantitative skills and scientific literacy, particularly around climate issues. Build collaborative lab models for teaching and learning. Rethink the semester seminar, perhaps turning instead to modular and tutorial formats. Create high-end practicum and internship opportunities and connect graduate programs with an array of local, regional, and national institutions. Recognize the range of non-tenure track teaching and craft pedagogical training accordingly. Encourage dissertations that are not only books in the making, but that utilize digital formats, offer multiple public-facing essays, develop community-based projects, and explore other innovative forms. If on a full-funding model, then leverage small cohort size to create faculty teaching and mentoring clusters that break down traditional learning based on geography and chronological periodization. If on a tuition and teaching model, consider admitting more students, leveraging quicker time-to-degree and a range of engaged learning opportunities. Ensure that new strategies are geared to a more diverse range of students, enabled rather than constricted by changes in timing, format, and goals.

Some of these ideas might well expand what historical graduate education can do and who can do it, and for that great, but they hardly confront the main problem they seek to address: decent, stable employment for the teaching and researching of history. Maybe they solve the problem of justifying to administrators and boards of trustees the most elite programs in historical doctoral education, and maybe they can make the most elite professors in the profession feel good for being able, possibly (although even this remains dubious), to place students in other elite quarters of the professional-managerial classes, but in the process they largely abandon the historical profession itself: the insistence that it is a specialized path of highly skilled labor; the need for the field to stop the exploitative adjunctification of scholarly labor; the sacrifice of a wider field of sustainable scholarship by the many for the cheap thrills of a few select superstars who concentrate their own power within a rotten system, even at the expense of the careers of their own students as historians.

Deloria’s proposal feels like a smokescreen, I hope an unintentional one, that floats atop a smoldering ruin. That ruin is the abhorrent labor practices currently dominating higher education, particularly in humanities fields such as history. Instead of confronting those squarely as the leader of a prominent national professional organization, Deloria proposes that graduate programs should try “flooding the zone” of other professions with advanced-degree historians (although in his vision this advanced degree is no longer exactly that, it’s more of a sort of in-between Masters and PhD). “Flooding the zone” is a funny phrase to use, given that the last prominent person to use the term was Steve Bannon, the white nationalist right-wing political strategist. He described the conservative path to power as best accomplished through continual work to “flood the zone with shit.” I highly doubt Deloria wants to do such a thing, but his proposals for transforming historical graduate education certainly move in a rather putrid direction.

Maybe there are some other ways to think about historical graduate education. After all, there are, despite shifting demographics, still plenty of students to teach at the college level in the United States. Yet the historical profession’s most prestigious members seems oblivious to this fact. So focused on the most elite programs and how they might connect to other elite areas of American society, Deloria forgets the historical profession itself, the many regional universities and community colleges and smaller institutions. These could, with insistence on their value, offer a more egalitarian labor model for good jobs studying and teaching history. Yet in place of fighting for and insisting on the end of adjunctification and the demand for more stable, middle-class, tenure-track professorships across the ranks of regional universities and colleges, Deloria imagines instead a set of superficial, ill-defined transformations: speed ups to degree, abandonment of traditional comprehensive exams, portfolios, labs, internships, collaborative partnerships.

These are solutions only a managerial class could love: training for only more of the contingent labor practices and devaluing of intellectual labor that is precisely the current problem! Deloria’s proposals would maintain his and other elite faculty positions for the very few while precluding the preservation of time needed for difficult, extended historical research and discovery by graduate students. It’s a substitution of shiny, “save the world” fantasies about what historical education can do laterally in other fancy fields instead of a concentration on the need for affirming and insisting upon the basic employment conditions and infrastructure needed for sustaining the profession itself—and for making it better.

Here’s the most insidious dimension of the kind of thinking embraced by Deloria in his column. This kind of “rethinking” of graduate education not only undermines the profession at a moment of crisis, it also serves, troublingly, to maintain the very prestige system within the profession from which Deloria and others currently benefit. The fewer tenure-track professorships exist across America’s rich range of regional universities and community colleges, the more privileged and powerful the few historians at the top become. The “innovations” that they think are saving the profession in fact doom it. Their brilliant disruptive transformations allow them to sit atop rotting foundations. Eventually this will lead to the whole field’s collapse, as is already happening. At some point, why wouldn’t any higher ed administrator worth their managerial salt say: who needs historical graduate education? Why not just have a bunch of ersatz-historical degrees as part of the public policy program or the business school or marketing department?

To be sure, new ways of learning and sharing in the making of historical knowledge are wonderful; but only if they are positioned within a robust professional training of future scholars and a field of career opportunities to practice the scholarly discipline of history. Otherwise, the abandonment of distinctive, specialized training and knowledge are a recipe for disciplinary disaster. So yes, bring on the learning “innovation.” We need more labs, collaborations, internships, digital training, podcasts, websites, public projects, pedagogical training, a wider range of publications that qualify for tenure and promotion, more community partnerships. These are all good as part of an expansion of the core jobs of the profession itself. But if history graduate programs are to embrace these modes, then they need to position them as work done by tenure-track professors, not as a replacement for those positions.

Moreover, introducing these new approaches to history means it should take more time to degree, not less time. Students will need more time to perfect their craft, to train across a wider range of fields, to acquire the extensive administrative skills required to enact complex, multi-partner projects. They will need time and support to possess those while also continuing to hone their capacities as highly skilled, expert practitioners of existing—and promisingly new—historical methods.

What if instead of turning away from history as a profession, Deloria and the OAH doubled down on the advanced nature of what we do? Historians are not all-purpose thinkers at the graduate level, offering “disciplinary expertise applicable to all social sectors.” That might be part of our work as teachers of undergraduates, but at the graduate level, what we do is more like what biochemists or statisticians or economists or other similar highly-skilled specialized “knowledge” workers do. Instead of undervaluing this, what if the leaders of the history profession insisted upon its value for their less prestigious colleagues and their students alongside themselves? What we do requires extensive training. Then it requires an insistence, a demand, to those in power that they economically value that training in their employment practices. Our organizations should protect the significance of extensive, high-level, specialized historical training, not abandon it. Perhaps at an elite place such as Harvard, Deloria is taken in by the allure of his graduate students working in other (also quite elite) fields and jobs, but it leaves the rest of the profession—and even his own students—in the dust.

What if, instead of accepting the awful labor practices that now dominate the teaching of history in higher education, the field’s biggest professional societies such as the OAH organized a new accreditation system that made adjunctification an embarrassment for any institution, big or small? What if they weighed in with professional guidelines for tenure-track employment that department chairs of history departments could wield with their administrators to push for tenure-line hires rather than the use of exploited adjuncts? What if the most elite professors in the profession stopped spreading misinformation about unionization or just shrugging their shoulders as if it wasn’t their problem and got more militant and organized in challenging everything from right-to-work laws to the hiring of anti-union law firms by their own institutions to the Yeshiva decision? What if instead of abandoning history as a specialized, expert, advanced profession, the field’s lead organizations asserted their power to protect the profession, to become the guarantors of solid, expert teaching of history in higher education through the insistence on ethical labor practices?

After all, more tenure-track jobs across the spectrum of higher education are not just good for those who get them; they are also good for the communities in which those professors work. Tenure-track faculty at local institutions promises to foster regional universities and community colleges as thriving centers of community life, engines of economic growth, and spaces of democratic involvement and participation. A flourishing local university or college with stable, sustainable employment practices is as important, if not more so, for locales as landing a corporation headquarters or factory. Moreover, good tenure track jobs at these places enable the possibility for a wider range of public projects, community partnerships, and more creative, available modes of historical scholarship. These are precisely the sort of innovations Deloria dreams of in his column. Tenure-track faculty across the breadth of higher ed institutions in the United States even contributes to a more stable tax base in depopulating areas, and to more healthy, stabilized communities overall. We should fiercely advocate for these good-paying, highly skilled jobs and the graduate training required to filll them, not abandon the kind of graduate education they entail for a fantasy of historians in other professions. None of Deloria’s proposals definitively train graduate students for other professions anyway; they are vague. Even worse, are there really robust employment opportunities in these other fields? And would a four-year advanced degree in history really qualify one for whatever work is out there? Who knows?

The one thing turning away from Deloria’s proposals to these other suggestions might accomplish is an end to the increasingly suspect hierarchy that now dominates the field, a prestige and status system in which fancy historians at a few places are like trophies for administrators and boards of trustees to display upon the mantle of a burning fire of adjunctified, immiserated teachers below them. For the select few, the spoils. For the rest, increasingly less time, stability, or resources to conduct research, not even on how to become better teachers, if they are not forced to subsist on food stamps. Enough of that. The proposals Deloria suggests will only further turn higher education to a flooded zone…of wet ashes. In their place, what if we reassert—or maybe even assert for the first time—the specialization of graduate training, not the generalization of it? Of course, let’s do all we can to fight usurious student debt regimes and other obstacles so that we can open up the doors wide for whomever wants to go for it to obtain that training. Then let’s push for stable, sustainable employment at the end of historical graduate training, for long-term tenure-track jobs that are properly valued for the essential researching and teaching of the past they deliver to American college students and the broader public. If we do that, then by all means, let’s also bring in the portfolios, labs, internships, teams, new modes of scholarship, and the crucial webs of connection to the rest of society. They fit as part of that labor model, but not as a substitution for it.

In short, maybe we should insist upon historical graduate education for, you guessed it, learning the discipline. Otherwise, the intensive study of the past, a practice that any functioning democratic society desperately needs, threatens itself to become history.

July 18, 2021

Disarmed

Despite taking place over the Internet, Tania El Khoury and Basel Zaraa’s As Far As Isolation Goes (Online) explores issues of direct touch. It leaves its mark despite the lack of direct physical contact. Like a number of pandemic performances, it explores the stakes of how digital intimacy meets public alienation and distance through the model of connecting one performer to one audience member (see, for instance, the playlets in Theater For One: Here We Are, also performed this past spring of 2021).

The performance considers the traumas of a refugee’s life through a series of short encounters with Zaraa and additional film clips of hip hop performance. Tania El Khoury, artist in residence at Bard, helped to bring the piece to the Fisher’s online theater. The play build’s on Zaraa’s 2019 “As Far as My Fingertips Take Me,” which took place in person. In that play, audience members stuck an arm through a hole in a temporary wall so that Zarass could draw on it, mapping out his story quite literally on the flesh of the listener even as the wall conveyed how the borders and boundaries, policies and practices, of nation-states created his refugee situation. Forced to adjust by the Covid-19 pandemic in this sequel, the online incarnation of As Far As Isolation Goes intensified this sense of disruption. Now all that established a connection between performer and audience was the mediated space of Internet video. One could connect over it, but the relationship felt even more fleeting, temporary, and dislocated. Not even some kind of physical touch was possible.

Yet there is a stubbornness to the piece, so that even with the pandemic’s intensification of absence, maybe even because of it, a spirit of presence springs forth. Forced to interact beyond even arm’s length, we are drawn in. Zaraa appears in the video box, with a background that becomes a kind of placeless digital stage. We are all just bits and bytes, pixels and streams, separated. Nothing feels quite real. But then, as in person, what starts to matter most is that one is involved, one pays attention. Zaraa instructs the viewer to draw on their own arm as he explains his story, so that we as audience members wind up quite literally inscribing on our own skin a refugee’s sense of flight, loss, and fragmentation. We draw for him, on ourselves. We are a proxy, and we become proxy to the tale. Ostensibly we are safely in front of our screens at home, but the boundaries of body and screen, skin and ink, self and other, location and dislocation, begin to at once dissolve and take shape, disappear and then come profoundly into view.

The additional appearance of hip hop spoken word performances by a number of Zaraa’s friends only adds to the play’s explorations of marking, touching, and connecting at a distance. Prerecorded, they are interspersed with the direct, live moments in As Far As Isolation Goes (Online). The use of hip hop, with its traditions of glyphs, cyphers, and graffiti, of shouting out across appropriated, reimagined musical tracks, speaks in surprising and potent ways to the refugee experience. From temporary zones of the global modern world, it enables disempowered figures to leave their mark, flex their muscles, and reach for something more than merely what they have been handed.

In As Far As Isolation Goes (Online), it turns out that it only goes so far. Even as the marks fade, the stories get under our skin.

July 15, 2021

History’s Rough Draft

Nikole Hannah-Jones, lead reporter for the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, speaking at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in 2019.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, lead reporter for the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, speaking at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in 2019.The 1619 Project has, as intended, generated tremendous debate, both in the broader public sphere and among professional historians. Most of the discussion focuses on how the project strives to recenter the story of the United States around the realities of slavery rather than ideals of freedom. At once building on the work of at least three generations of scholarly historians, beginning with someone such as W. E. B. Du Bois, 1619 also paradoxically argues that the essential role of slavery in American history has long been ignored. It seeks to intervene in the broader popular understanding of the nation’s past by taking on the authority of conducting specialized scholarly research while still remaining journalism. In doing so, it moves journalism from its supposed role as “the first rough draft of history” (a phrase generally attributed to Washington Post President and Publisher Philip L. Graham) to proposing that it can present the best, final version.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Like any profession, scholarly history puts up gates and draws boundaries about who gets to wield authority and on what terms. However, in this case, many academic historians have already been moving in just the direction proposed by the 1619 Project as a new intervention. Popular history, measured by best sellers, has most definitely not, it should be noted; but academic historians have done so at least since the rise of social history in the 1970s. This has led to a push among academic historians to try to break through to the general public rather than only speak to each other as specialists. As a result, an odd collision emerges: while the 1619 Project features journalism as history, many historians increasingly pursue what might be described as history as journalism. Journalists claim Clio’s authoritative robes. Historians want to communicate directly to the public. Journalists develop projects of historical research. Historians publish op-eds, email newsletters, blogs, websites and host podcasts or direct documentary films. In short, the most prestigious journalists now claim the mantle of historians while highly esteemed historians hope to position themselves as journalists. While there is much else to discuss about the 1619 Project and the range of responses to it, the issue of how journalism and history collide is a little explored dimension of why the publication and historians’ responses to it matter.

To be sure, there has always been overlap between the professions of journalism and history; however, it is perhaps only with the collapse of previously stable modes of employment in these two fields over the last decades that we see a publication such as the 1619 Project emerge in its particular way, with its goal of altering public understandings of the long-running injustices and injuries of racism from the positionality not of a journalistic piece about what historians are doing, but rather as history itself. In journalism, corporate consolidation has eroded conventional daily “desk” reporting positions and placed much more focus on the revelatory interpretations of so-called long-form narrative. The 1619 Project does not just report on the findings of historians, it proposes to be telling history itself. It does so by contending that academic history has refused to recognize the facts, or tell the stories of slavery. Yet that contention is a bit disingenuous, since much of the 1619 Project builds precisely on powerful historical scholarship that has moved the stories of slavery and race to the center of the field. At the same time, the Project is still journalism, and so it needs to play by the conventions of that genre of writing. Therefore, 1619 must emphasize how it is not merely conveying historical findings, but rather is “breaking” a new story, which remains a paramount framing device in journalism. So too, the story must be bold and straightforward, supposedly, to reach a popular audience. It might even need to shock the reader. These create very different norms than in specialized historical scholarship. The imperatives of the field tilt away from the subtleties of historiographic debate or the ambiguities of the historical record and toward simplifying interpretations of historical evidence rather than considering complexity.

This is largely the critique found in Dr. Leslie M. Harris’s commentary about her role as a fact-checking historian for the 1619 Project. Crucially (and I would say rightfully), Harris still finds the attacks on 1619 far worse than the Project’s shortcomings, but her response articulates quite well the distance between academic historical approaches to the past compared to contemporary journalism.

What Harris does not mention is how the field of academic history itself, like journalism, is in crisis. The adjunctification of teaching positions has led many scholars beyond campus into the realms of public and “alternative-academic” labor. Even though there remains much historical scholarship to do, American universities are choosing not to create enough stable positions to do the work. This has led many academic historians to seek prestige, status, and employment not just in the traditional domain of specialized scholarship, but rather beyond campus. Even more oddly, some try to parlay attention beyond campus into a job in academia. As a side note, this intriguingly parallels how Hannah-Jones’s moved from success in journalism to a prestigious position at Howard University, although it should be noted that she only did so after the conservative Board of Trustees at her alma mater of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill overruled their own faculty to prevent Hannah-Jones from straightforwardly receiving a tenured appointment there, a troubling sign of who really holds power in contemporary American life: neither journalists nor historians. Yet young historians do not necessarily dream of writing great, nuanced historical essays or monographs for other historians; they yearn to become public intellectuals, pundits, talking heads, social media influencers, even brands (but maybe not H. W. Brands). They yearn to be…Nikole Hannah-Jones. This might even lead back to a tenure track job in the academy. It is a funny situation in which journalists move up the ranks by borrowing from historians, while historians potentially ascend their own professional ladder by acting like journalists.

There are far more concerning issues when it comes to the 1619 Project of course, such as the superficial yet awful assaults on the 1619 Project by cynical conservative politicians frothing at the mouth in their never-ending culture war. But it wasn’t only conservatives who criticized Nikole Hannah-Jones, it was also a number of liberal and even radical historians. Why? These historians complained by and large about the accuracy of her emphases and narrative choices. Hannah-Jones and her editors responded, in essence, that the 1619 Project worked by different rules and norms than academic history in how it wielded evidence, engaged with past scholarship, framed arguments, and offered interpretations. Nonetheless, they wanted to retain the value of the project as historical scholarship. They claimed to be saying things afresh even as they also simplified historical findings in problematic ways within the ground rules of academic history.

Perhaps the success of the 1619 Project as historical journalism merely generated envy among historians aspiring to mass public audiences, but more crucially it provides a way to notice the contested terrain between these two currently destabilized professions. Both want to be able to control the stories we tell about the national past according to their existing traditions while also borrowing prestige or access from the other field.

Can journalism’s first rough draft of history become history’s last best one? Can, in turn, history’s nuanced, deeply contextualized research effectively contribute to journalism’s efforts to capture the present? Can news makers capture history and history tellers make news? Part of the answers to these questions likely lies in creating more viable employment opportunities in each field. From there, more imaginative thinking about how their norms diverge but also can converge might arise in healthy ways. Rather than squabble, journalists and historians might work together in new arrangements and incarnations. Beyond the collisions between historical journalism and public history the 1619 Project points to new possibilities for both conscientious history and historical consciousness.

July 2, 2021

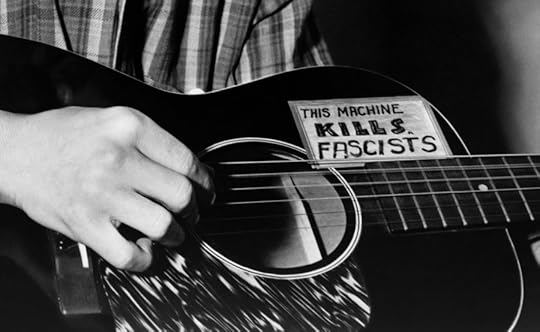

This Anthem Was Made For You & Me?

Just in time for your Fourth of July Independence Day weekend reading list, over at the website Clio and the Contemporary, I have a new essay about Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” & the question of alternative national anthems for the USA:

June 30, 2021

Rovings

SoundsClaire RousayLive – EPA Softer FocusI’ll Give You All of My LoveA Heavenly TouchColin Currie and Hakan Hardenberger, The Scene of the CrimeNate Lepine, Quartet: VorticesQuin KirchnerThe Other Side of TimeThe Shadows and the LightRogue Parade, Stomping off from GreenwoodChinchanoUn CambioEl RegresoEiko Ishibashi, Torn PageICE Contemporary, Field AurasDon Cherry on Swedish TV Documentary 1978Brötzmann / van Hove / Bennink“The End” (1974/02/04)“Einheitslied” (1974/02/04)Misha Mengelberg, Afijn

Now & Then

audio podcastEthel Waters, “Supper Time”Public Enemy, “Long and Whining Road”WordsFletcher, Jennifer Dunlop, Joseph Becker, Iwan Baan, Simon Sadler, and Chip Lord, The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and IdealismLawrence Chua, Bangkok Utopia: Modern Architecture and Buddhist Felicities, 1910–1973Gary Snyder, Three poems for animals, with Chinese translation by Wang Ping

A Black Gaze: Tina Campt and LeRonn Brooks in Conversation

, Getty Research InstituteHua Hsu, “How Sun Ra Taught Us to Believe in the Impossible,” New Yorker, 28 June 2021“Walls”

Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945

, Whitney MuseumFrank Bowling: London/New York, Hauser and WirthPrivate Lives Public Spaces, MoMA

¡Viva la Libertad!

, Newberry LibraryLouise Bourgeois: Freud’s Daughter, Jewish Museum

Hurven Anderson: Anywhere But Nowhere

, Arts Club of Chicago

Bethany Collins: Evensong,

Frist Art Museum

Senses of Brown: Curated by César García-Alvarez

, The Armory Show

Nancy Rubins: Fluid Space

, Gagosian Beverly Hills

Social Works: Curated by Antwaun Sargent

, Gagosian

Helen Frankenthaler: A Sculpture and a Selection of Works on Paper,

Gagosian London

Julie Curtiss: Monads and Dyads

, White Cube“Stages”Elizabeth A. Baker,

Sound Films,

Gray SoundBatsheva Dance Company,

Yag

, Joyce TheaterDavid Hammons, Global Fax Festival: A New Performance Dedicated to Butch MorrisSpektral Quartet,

Something to Write Home About,

Harris Theater

Moony

, Steep Theater

The Catalyst Quartet Presents: Uncovered—Florence B. Price

, Greene SpaceKyle Marshall, STELLAR, PlayBACSusie Ibarra, RouletteHan Bennick, Option Series, Experimental Sound StudioScreensMysteries of Lisbon

Pizza Pizza Daddy-O

SoundsClaire RousayLive – EPA Softer FocusI’ll Give You All of My LoveA Heavenly TouchColin Currie and Hakan Hardenberger, The Scene of the CrimeNate Lepine, Quartet: VorticesQuin KirchnerThe Other Side of TimeThe Shadows and the LightRogue Parade, Stomping off from GreenwoodChinchanoUn CambioEl RegresoEiko Ishibashi, Torn PageICE Contemporary, Field AurasDon Cherry on Swedish TV Documentary 1978Brötzmann / van Hove / Bennink“The End” (1974/02/04)“Einheitslied” (1974/02/04)Misha Mengelberg, Afijn

Now & Then

audio podcastEthel Waters, “Supper Time”Public Enemy, “Long and Whining Road”WordsFletcher, Jennifer Dunlop, Joseph Becker, Iwan Baan, Simon Sadler, and Chip Lord, The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and IdealismLawrence Chua, Bangkok Utopia: Modern Architecture and Buddhist Felicities, 1910–1973Gary Snyder, Three poems for animals, with Chinese translation by Wang Ping

A Black Gaze: Tina Campt and LeRonn Brooks in Conversation

, Getty Research InstituteHua Hsu, “How Sun Ra Taught Us to Believe in the Impossible,” New Yorker, 28 June 2021“Walls”

Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945

, Whitney MuseumFrank Bowling: London/New York, Hauser and WirthPrivate Lives Public Spaces, MoMA

¡Viva la Libertad!

, Newberry LibraryLouise Bourgeois: Freud’s Daughter, Jewish Museum

Hurven Anderson: Anywhere But Nowhere

, Arts Club of Chicago

Bethany Collins: Evensong,

Frist Art Museum

Senses of Brown: Curated by César García-Alvarez

, The Armory Show

Nancy Rubins: Fluid Space

, Gagosian Beverly Hills

Social Works: Curated by Antwaun Sargent

, Gagosian

Helen Frankenthaler: A Sculpture and a Selection of Works on Paper,

Gagosian London

Julie Curtiss: Monads and Dyads

, White Cube“Stages”Elizabeth A. Baker,

Sound Films,

Gray SoundBatsheva Dance Company,

Yag

, Joyce TheaterDavid Hammons, Global Fax Festival: A New Performance Dedicated to Butch MorrisSpektral Quartet,

Something to Write Home About,

Harris Theater

Moony

, Steep Theater

The Catalyst Quartet Presents: Uncovered—Florence B. Price

, Greene SpaceKyle Marshall, STELLAR, PlayBACSusie Ibarra, RouletteHan Bennick, Option Series, Experimental Sound StudioScreensMysteries of Lisbon

Pizza Pizza Daddy-O