Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 35

March 16, 2021

What Does A Photograph Sound Like?

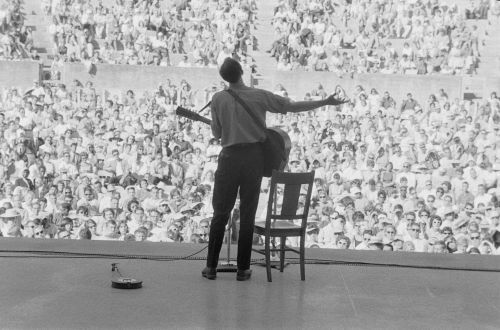

Computers have the capacity to transpose the pixels, shapes, and other features of visual material into sound. This act of data correlation between the visual and the audial produces a new artifact, a sonic composition created from the visual source. The new artifact, however, correlates precisely to data in the original, thus allowing for fresh ways of perceiving its form, content, and context. Seeming to distort the visual object into an aural one paradoxically allows an observer to observe the visual evidence anew, with more accuracy. A kind of generative, synesthetic criticism becomes possible by cutting across typical boundaries between the visual and the audio, the optic and the aural. Listening to as well as looking at visual artifacts by way of digital transpositions of data enables better close readings, more compelling interpretations, and deeper contextual understandings. Building on my earlier scholarship into image glitching, remixing, and sonification, this essay investigates a photograph of Joan Baez performing at the Greek Amphitheater in Berkeley, California, during the early 1960s. The image comes from my project on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival and the history of the folk music revival on the West Coast of the United States. Here, the use of digital image sonification becomes particularly intriguing. While we cannot magically recover the music being made in the photograph, we can more closely attend to the ghosts of sound within the silent snapshot. Digital image sonification does not recover the music itself, but it does help to amplify issues of gender, power, embodiment, spectacle, performance, hierarchy, and performance in my perceptions of Baez making music in the photograph. Using the ear as well as the eye to scan the image for its multiple levels of meaning leads to unsuspected perceptions, which then support more revealing analysis. In digital image sonification, a cyborgian dance of data, signal, image, sound, history, and human perception emerges, activating visual materials for renewed scrutiny. In doing so, this mode of AudioVisual DH activates the scholarly imagination in promising new ways.

To read the full essay: Michael J. Kramer, “What Does A Photograph Sound Like? Digital Image Sonification As Synesthetic AudioVisual Digital Humanities,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 15, 1 (2021).

March 13, 2021

In the Vernacular

Vernacular culture never disappears. Like the people it serves, it is always with us, sometimes driven beneath scrutiny, sometimes outlawed, patronized, deprecated, repressed, always infra dig.

— WT Lhamon, Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s

February 28, 2021

Rovings

February 9, 2021

Berkeley Folk Music Project Receives NEH Funding

Dr. Michael Kramer, assistant professor in the Department of History at SUNY Brockport, received a $30,000 National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Projects for the Public Grant to continue work on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. The grant will support the development of a website with interactive essays, an audio podcast, and a curated archive about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, which took place at the University of California, Berkeley from 1958 to 1970. The Festival offers a window into the vibrant and understudied West Coast folk music and cultural milieu of the 1960s.

The archival repository for the Festival resides at Northwestern University Libraries’ Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives. Kramer’s project builds on a previous NEH grant received by the Northwestern University Library system to digitize the collection, with Kramer consulting on that project.

Kramer has taught a course connected to the project, Digitizing Folk Music History, at Northwestern, Middlebury College, and now SUNY Brockport. With the new NEH DPP grant, graduate and undergraduate students in SUNY Brockport’s Department of History will participate as research assistants on the project, which includes a partnership with a web design firm, Extra Small Design, based in Phoenix, Arizona.

The award will be administered by The Research Foundation for SUNY Brockport. More about the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project can be found at bfmf.net.

Pete Seeger performing in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater at the University of California, Berkeley as part of the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photographer unknown.

Pete Seeger performing in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater at the University of California, Berkeley as part of the 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photographer unknown.

January 31, 2021

Rovings

January 29, 2021

Temporary Seating

The map of Iraq looks like a mitten, / and so does the map of Michigan— / a match I made by chance.

— Dunya Mikhail

— Theodore Roethke

A funny thing about a Chair: / You hardly ever think it’s there. / To know a Chair is really it, / You sometimes have to go and sit.

Bernie Sanders at Joe Biden’s inauguration, 20 January 2021. Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP.

Bernie Sanders at Joe Biden’s inauguration, 20 January 2021. Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP.As Naomi Klein proposed most compellingly (“The Meaning of the Mittens: Five Possibilities,” The Intercept, 21 January 2021), the now omnipresent meme of cranky Bernie Sanders is all about the mittens. They rest, criss-crossed, on his lap, oversized, practical, unfussy, realistic, and ready for reaching out to touch the broken world as it is, with all the urgent need for getting to work to fix it.

But the meme also contains another symbolic element that has gone less noticed: the chair. In particular, the image signals the political meaning of chairs. They don’t call it a “seat” of power for nothing. Think of the Iron Throne, the chairman of the board, the party chairman. Where, after all, was one of the first places the insurrectionists went when they got into the Capitol but a week earlier than the inauguration of Joe Biden outside the same building? They sat in the chairs on the dais of the Senate and House chambers. They sat in Speaker Pelosi’s chair and put their feet up on her desk.

Sitting is power. Even when it becomes a weapon of the oppressed, as in the civil rights sit-in, the capacity to be not only in good standing, but also hard sitting is a potent expression of protest, a way to mark issues of inclusion and exclusion. from the polity or from civil society. Do you have a seat at the table, or even at the Woolworth’s counter? Who gets to sit at all, and where they get to sit, really matters.

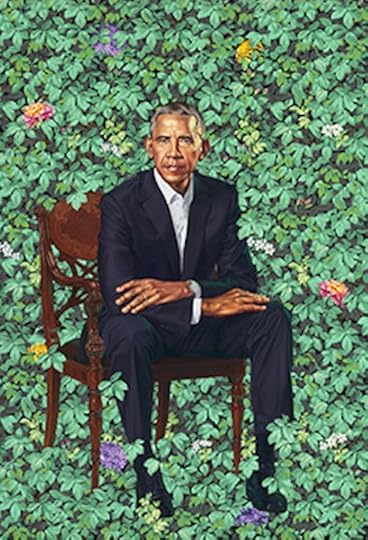

One image that came to mind from the resonances of the Bernie mittens meme was the controversial official portrait of Barack Obama, painted by Kehinde Wiley in 2018. What is Obama doing in the painting? Most noticed that he emerged, almost surrealistically, from a wall of foliage and symbolic flowers. He also sits in a chair. In this case, it is a wooden one that draws upon the Regency style blended with more contemporary elements.

Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley, oil on canvas, 2018.

Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley, oil on canvas, 2018.Bernie, in contrast to the Obama portrait, sits in a flimsy folding chair. He looks cold and grumpy, not suave and elegant. He is typically frumpy and disheveled. At the same time, he is but one of the few present at the inauguration at all due to Covid-19 safety restrictions, right down the aisle from the Obamas themselves. This Social Democrat now has a place closer to the centers of power in American politics. After all, he is now the chair of the Senate Budget Committee.

In this way, the original photograph is as much about the chair as it is about the mittens. To be sure, the mittens steal the show. As Klein eloquently put it:

In that moment, Bernie’s crossed arms and sartorial dissonance seemed to be saying, “Do not cross us.” If, after all the hoopla, the Biden-Harris administration doesn’t deliver transformational action for a nation and a planet in agony, there will be consequences. And unlike during the Obama years, those consequences won’t take years—because the revolutionary spirit is already on the inside, and it’s wearing mittens.

But the chair matters too. It’s not just that Bernie is bemittened that made the image proliferate so much; it’s also that he’s sitting in his chair. In the circulating meme, he sits everywhere, both joining the images in which memers have placed him, but also always slyly commenting on the images. He is not exactly a naif, an innocent accidentally wandering through the iconography of history—he’s not a pure outsider like Forrest Gump or Zelig. Instead, he is at once both insider and outsider. He is part of whatever mise-en-scène into which he is placed, yet never quite of it. He comes from another place, bringing another vision of the world, and harkens to that other worldview like an alien landed from another planet (seated, with large mittens) to bring messages of goodwill and utopian possibility.

To use the musical term for dropping in as a guest with a band, Bernie sits in with all these other images—as he does with the original setting on the Capitol steps at the inauguration. He is in them but not of them. He perches on ledges; sidles up to counters; sits on benches; joins famous movie scenes and tv shows; finds a place among reclining rock bands; takes his place in a seat within historical photos. Everywhere he goes, however, he refuses to join in entirely. He sits it out.

The Bernie meme, in this way, is also a stand-in. It serves as a symbol of social democratic desire in contemporary America. It proposes that enough is enough with the lack of universal health care, with racial injustice, with student debt, with climate change unconfronted, with tax cuts for the rich and the squeeze on everyone else. It signals that there are no-nonsense policies that can start to address these long-running problems. What are we waiting for? We are many (ready to warm up our hands), they are few.

While some have interpreted the meme as a “cutesification” of Bernie’s radicalism, and the radicalism of his supporters, as a taming of their energies, there is more to the image than just a Seinfeldification of Sanders. The more it circulates, the more it suggests that Bernie’s political sensibility lurks more places than one might think. Yes, it whispers its presence, muffled. It is inchoate. But it also starts to spring up everywhere, comically, warmly, sweetly, but also with an edge to it. There is something almost zoomorphic about Sanders, mostly due to the giant Vermont-made mittens looking a bit like paws, and also because of how he sits in his chair, as if possibly poised to pounce. Sanders, with all that he represents, seems about to spring from his seat, not only into the halls of power, but also perhaps across the breadth of American culture. The more one looks, the more those mittens start to seem like they might have claws.

January 26, 2021

Syllabus: US Since 1929

In this research-intensive course, we explore US history from 1929 to the present. Building on your basic understanding of US history, the course helps you develop six aspects of your liberal arts education and historical study:

a more sophisticated understanding of US history, particularly the historiographic debates among scholars about how to interpret the American past since 1929;learn about history itself as a discipline focused on empirically driven and theoretically sophisticated interpretive narratives and conversations about the past;notice the arc of key themes in twentieth-century American history such as race, gender, class, sexuality, region, culture, the law, the state, politics, economics, and ideas;improve your research, writing, and communication skills;work on your capacity to synthesize and handle informational complexity;consider how you might draw upon the knowledge you acquire in this course for teaching and other professional pursuits.We will be doing a lot of reading, but you will learn how to read for historical understanding more efficiently. We will also divide up the readings and use our discussion to bring together the different ideas and information they contain. Each student will complete a weekly response worksheet, a final project proposal, and a final historiographic essay based on readings in the course and additional material. Weekly online synchronous meetings are run as a synchronous seminar, and will focus on discussion with occasional lectures from the instructor.

How This Course WorksThis is a synchronous online course. That means you need a computer with a camera and microphone or some device that allows you to access the course and a decent Internet connection. Please confer with SUNY Brockport if you do not have access to this equipment and technical requirements. Please show up for class at our regular meeting times (there are a few built-in breaks throughout the semester too). Ideally you can turn your camera on and keep your microphone muted except when you wish to speak. A headset or earbuds with microphone often help a lot too for blocking out extraneous noise. You will also be well-served by finding a quiet, calm place from which to attend class online.

Digital learning during the pandemic is challenging for all of us and I will be as flexible as possible with your particular needs and situations according to SUNY Brockport policy. So long as you are participating in the course in good faith, we can still learn a lot together even though we are doing so under these extraordinary circumstances.

Digital ToolsWe will use a few digital tools in the course to facilitate our study together:

1. Computer with Camera and Microphone/Internet AccessA computer with a camera and microphone or some similar device that allows you to access the course.A decent Internet connection.A headset or earbuds with microphone.A quiet place from which to attend class.2. Canvas (Not Blackboard)I use Canvas instead of Blackboard. In most ways, it works the same as Blackboard, but I think its design, navigation, and performance are far superior. You will receive an invitation to join the course Canvas website at the start of the semester. Think of our Canvas website as the central syllabus, schedule, and assignment submission tool for the course—home base.

3. Google DocWe will use a basic Google Doc to sign up for and organize together the specific reading assignments in the course (explained below). This means you need a gmail account of some sort. They are free, most of you probably already have one, but if you do not, then create one at the Google Docs website.

4. ZoomWe will use Zoom as our online classroom for synchronous discussions. You can sign up for a free Zoom account if you do not already have one.

If you have questions about the technical requirements for the course, or about the hybrid nature of the course, please feel free to contact me.

ReadingWe will be doing a lot of reading, but you will learn how to read for historical understanding more efficiently. We will also divide up the readings and use our discussion to bring together the different ideas and information they contain. Each student will complete a weekly response worksheet, a final project proposal, and a final historiographic essay based on readings in the course and additional material. See my “Gutting” Books and Sharing Work for Historical Understanding” for more tips and instructions on reading for this course.

WritingWeekly Response Worksheets help me to gauge how you are processing and making sense of course content.Final Historiographic Essay proposals and development help me aid you in shaping your final project.Your Final Historiographic Essay gives you the opportunity to develop your ability to write a graceful, argument driven piece of writing, driven by research into debates about how we interpret a specific aspect of US history since 1929.DiscussionWe will join together remotely to practice the art and craft of historical discussion. How do we share ideas, articulate perspectives, ask good questions, and develop both individual and shared understandings of the past we are studying together.Required Materials To PurchaseRichard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017) ISBN: 978-1631492853W. T. Lhamon, Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s, Second Edition with a New Preface (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002) ISBN: 978-0674008731Michael J. Kramer, The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) ISBN: 978-0190610753Bethany Moreton, To Serve God and Walmart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise (Harvard University Press, 2009) ISBN: 978-0674057401Carlos Lozada, What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020) ISBN: 978-1982145620Additional readings, viewings, and more on CanvasScheduleWEEK 01 The 1930s New Deal as Starting Point and FrameworkRequired Reading Week 01Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore, “The Long Exception: Rethinking the New Deal in American History,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 3-32Kevin Boyle, “Why Is There No Social Democracy in America?,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 33 – 37Michael Kazin, “A Liberal Nation In Spite of Itself,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 38-41Jennifer Klein, “A New Deal Restoration: Individuals, Communities, and the Long Struggle for the Collective Good,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 42-48Nancy MacLean, “Getting New Deal History Wrong,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 49-55David Montgomery, “The Mythical Man,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 56-62Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore, “History, Complexity, and Politics: Further Thoughts,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74, 1 (Fall 2008): 63-69Jefferson Cowie, “We Can’t Go Home Again: Why the New Deal Won’t Be Renewed,” New Labor Forum, 25 January 2011Crowdsourced Readings Week 01 (pick one of the following on the Google Doc, read to share with class in seminar):Daniel T. Rodgers, “Forum: Modern American History—The Social-Ethnography Tradition,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 67-70Madeline Y. Hsu, “Forum: Modern American History—Asian American History and the Perils of a Usable Past,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 71-75Adam Rome, “Forum: Modern American History—Crude Reality,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 77-82Kim Phillips-Fein, “Forum: Modern American History—Our Political Narratives,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 83-86Leigh E. Schmidt, “Forum: Modern American History—Pluralism, Secularism, and Religion in Modern American History, Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 87-91Michael Sherry, “Forum: Modern American History—War as a Way of Life,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 93-96Regina Kunzel, “Forum: Modern American History—The Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 97-100Natalia Molina, “Forum: Modern American History—Understanding Race as a Relational Concept,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 101-105Philip Scranton, “Forum: Modern American History—The History of Capitalism and the Eclipse of Optimism,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 107-111Kevin K. Gaines, “Forum: Modern American History—The End of the Second Reconstruction,” Modern American History 1, 1 (January 2018): 113-119Assignment: Course Contract and Student Info CardAssignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetWEEK 02 The 1930s—The New DealRequired Reading Week 02Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017)Crowdsourced Readings Week 02Richard Hofstadter, “From Progressivism to the New Deal,” in The Age of Reform: From Bryan to FDR (New York: Vintage Books, 1955): 272-328Lizabeth Cohen, “Encountering Mass Culture at the Grassroots: The Experience of Chicago Workers in the 1920s,” American Quarterly 41, 1 (March 1989): 6-33Michael Denning, “The Left and American Culture,” in The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1997): 1-50John Kasson, “Introduction” and “Smile Like Roosevelt,” in The Little Girl Who Fought the Great Depression: Shirley Temple and 1930s America (New York: WW Norton, 2014): 1-45Romain Huret, Nelson Lichtenstein, and Jean-Christian Vinel, “Introduction. The New Deal: A Lost Golden Age?,” in Capitalism Contested: The New Deal and Its Legacies, eds. Romain Huret, Nelson Lichtenstein, and Jean-Christian Vinel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020): 1-18Louis Hyman, “The New Deal Wasn’t What You Think,” The Atlantic, 6 March 2019Lawrence Glickman, “Donald Trump and the Anti-New Deal Tradition,” Process: A Blog for American History, 8 December 2016Lawrence Glickman, “The left is pushing Democrats to embrace their greatest president. Why that’s a good thing,” Washington Post, 14 January 2019Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1930sThe Great Depression (7 Episodes, dir. Henry Hampton and others, 1993)The Roosevelts: An Intimate History* (4 episodes, dir. Ken Burns, 2014)The Living DealMapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal AmericaWEEK 03 The 1940s—World War IIRequired Reading Week 03Samuel Zipp, “Dilemmas of World-Wide Thinking: Popular Geographies and the Problem of Empire in Wendell Willkie’s Search for One World,” Modern American History 1, 3 (September 2018): 295-319Crowdsourced Readings Week 03John W. Dower, “Race, Language, and War in Two Cultures: World War II in Asia,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, eds. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996): 169-201– Shirley Ann Wilson Moore, “Traditions from Home: African Americans in Wartime Richmond, California,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, eds. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch, eds.(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996): 263-283– Edward J. Escobar, “Zoot-Suiters and Cops: Chicano Youth and the Los Angeles Police Department during World War II,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, eds. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch, eds.(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996): 284-312Keisha N. Blain, “‘We Want to Set the World on Fire’: Black Nationalist Women and Diasporic Politics in the *New Negro World*, 1940–1944,” Journal of Social History 49, 1 (Fall 2015): 194-212Alan Brinkley, “World War II and American Liberalism,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, eds. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch, eds.(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996): 313-330Carol Miller, “Native Sons and the Good War: Retelling the Myth of American Indian Assimilation,” in The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II, eds. Lewis A. Erenberg and Susan E. Hirsch, eds.(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996): 217-240Margot Canaday, “Building a Straight State: Sexuality and Social Citizenship under the 1944 G.I. Bill,” The Journal of American History 90, 3 (December 2003): 935-957Thomas Sugrue, “Crabgrass-Roots Politics: Race, Rights, and the Reaction Against Liberalism in the Urban North, 1940-1964,” Journal of American History, 82, 2 (September 1995): 551-578Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1940sThe War (7 episodes, dir. Ken Burns, 2007)WEEK 04 1950s—Conformity, Consumerism, and Cool During the Cold WarRequired Reading Week 04W. T. Lhamon, Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s, Second Edition with a New Preface (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002)Crowdsourced Readings Week 04Elizabeth Fraterrigo, “The Answer to Suburbia: Playboy’s Urban Lifestyle,” Journal of Urban History 34 (July 2008): 747-774David Austin Walsh, The Right-Wing Popular Front: The Far Right and American Conservatism in the 1950s,” Journal of American History 107, 2 (September 2020): 411–432Robert Korstad and Nelson Lichtenstein, Opportunities Found and Lost: Labor, Radicals, and the Early Civil Rights Movement, Journal of American History 75, 3 (December 1988): 786–811Manfred Berg, “Black Civil Rights and Liberal Anticommunism: The NAACP in the Early Cold War,” Journal of American History 94, 1 (June 2007): 75–96Mary L. Dudziak, “Brown as a Cold War Case,” Journal of American History 91, 1 (June 2004): 32-42Erik S. McDuffie, “Black and Red: Black Liberation, the Cold War, and the Horne Thesis,” Journal of African American History 96, 2 (Spring 2011): 236-247Ashley D. Farmer, “‘All the Progress to Be Made Will Be Made by Maladjusted Negroes’: Mae Mallory, Black Women’s Activism, and the Making of the Black Radical Tradition,” Journal of Social History 53, 2 (Winter 2019): 508-530Katherine Turk, “Out of the Revolution, into the Mainstream: Employment Activism in the NOW Sears Campaign and the Growing Pains of Liberal Feminism,” Journal of American History 97, 2 (September 2010): 399–423Michelle Nickerson, “Women, Domesticity, and Postwar Conservatism,” OAH Magazine of History 17, 2: Conservatism (January 2003): 17-21Katherine Rye Jewell, “Gun Cotton: Southern Industry, International Trade, and the Rise of the Republican Party in the 1950s,” in *Painting Dixie Red: When, Where, Why, and How the South Became Republican*, ed. Glenn Feldman (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2011)Emily S. Rosenberg, “‘Foreign Affairs’ after World War II: Connecting Sexual and International Politics,” Diplomatic History 18, 1 (Winter 1994): 59-70Timothy Mennel, “A Fight to Forget: Urban Renewal, Robert Moses, Jane Jacobs, and the Stories of Our Cities,” Journal of Urban History 37, 4 (2011): 627–634Lizabeth Cohen, “From Town Center to Shopping Center: The Reconfiguration of Community Marketplaces in Postwar America,” American Historical Review 101, 4 (1996): 1050-1081Eric Avila, “The Folklore of the Freeway: Space, Identity and Culture in Postwar Los Angeles,”” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 23, 1 (Spring 1998): 15-31Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1950sDavid Halberstam’s The Fifties (7 episdoes, dir. Alex Gibney and others, 1997)Rebel Without a Cause (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1955)A Raisin in the Sun (dir. Daniel Petrie, screenplay by Lorraine Hansberry, 1961)WEEK 05 The 1960s–Citizenship and Unrest in the Great SocietyRequired Reading Week 05Michael J. Kramer, The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013)Crowdsourced Readings Week 05Rick Perlstein, “Who Owns the Sixties? The Opening of a Scholarly Gap,” in Quick Studies: The Best of Lingua Franca, ed. Alexander Star (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2002): 234-246Alice Echols, “’We Gotta Get Out of This Place’: Notes Toward a Remapping of the Sixties,” in Shaky Ground: The Sixties and Its Aftershocks (New York: Columbia University Press): 61-74Steven Lawson, “The View From the Nation,” in Steven Lawson and Charles Payne, Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968, Second Edition (New York: Routledge, 2006): 3-48Charles Payne, “The View from the Trenches,” in Steven Lawson and Charles Payne, Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968, Second Edition (New York: Routledge, 2006): 115-158Peniel E. Joseph, “The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field,” Journal of American History 96, 3 (December 2009): 751-776Van Gosse, “Defining the New Left,” in Rethinking the New Left: An Interpretive History (New York: Palgrave McMillian, 2005): 1-8Michael W. Flamm, “The Liberal-Conservative Debates of the 1960s,” in Michael W. Flamm and David Steigerwald, Debating the 1960s: Liberal, Conservative, and Radical Perspectives (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007): 99-168Christian G. Appy, Introduction, “Facing the Wall” and Ch. 1, “Working Class War,” in Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993): 1-43Alice Echols, “Nothing Distant About It: Women’s Liberation and Sixties Radicalism,” in Shaky Ground: The Sixties and Its Aftershocks (New York: Columbia University Press): 75-94Beth Bailey, “Sexual Revolution(s),” in The Sixties: From Memory to History, ed. David Farber (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 235-262Robyn Spencer, “Communalism and the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California in the 1970s,” in West of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California, eds. Iain Boal, Janferie Stone, Michael Watts, and Cal Winslow (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012), 92-121Thomas Frank, “Of Commerce and Counterculture,” in The Conquest of Cool Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997)– Jeremi Suri, “The Rise and Fall of an International Counterculture, 1960–1975,” American Historical Review 114 (February 2009): 45-68Rebecca Klatch, “The Counterculture, the New Left, and the New Right,” Qualitative Sociology 17, 3 (September 1994): 199–214Robert M. Collins, “The Economic Crisis of 1968 and the Waning of the ‘American Century’,” American Historical Review 101, 2 (April 1996), 396–422Adam Rome, “‘Give Earth a Chance’: The Environmental Movement and the Sixties,” Journal of American History 90, 2 (September 2003): 525–554Paul C. Rosier, “’Modern America Desperately Needs to Listen’: The Emerging Indian in an Age of Environmental Crisis,” Journal of American History 100, 3 (December 2013): 711–735Eric Zolov, “Introduction: Latin America in the Global Sixties,” The Americas 70, 3 (January 2014), 349-62Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1960sEyes on the Prize (14 episodes, dir. Henry Hampton and others, 1987-1990Berkeley in the Sixties (dir. Mark Kitchell, 1990)July ’64 (dir. Carvin Eison, 2006)The Vietnam War (10 episodes, dirs. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, 2017)Monterey Pop (dir. DA Pennebaker, 1968)Woodstock (dir. Michael Wadleigh, 1970)Gimme Shelter (dir. Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin, 1970)WEEK 06 Research WeekAssignment: Final Project ExplorationWEEK 07 The 1970s—”It Seemed Like Nothing Happened,” Or Did It?Required Reading Week 07Craig Phelan, Gerald Friedman, Michael Hillard, Kevin Boyle, Joseph A. McCartin, and Judith Stein, “Labor History Symposium: Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade,” Labor History 52, 3 (September 2011): 323-346Crowdsourced Readings Week 07Peter Carroll, “It Seemed like Nothing Happened,” The Antioch Review 41, 1 (Winter 1983): 5-19Heather Ann Thompson, “Introduction: State Secrets,” Blood in the Water: The Attica Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy (New York: Pantheon Books, 2016)Jefferson Cowie, “That ’70s Feeling,” New York Times, 5 September 2010Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, “Introduction: Homeowner’s Business,” Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019) Robert T. Chase, “We Are Not Slaves: Rethinking the Rise of Carceral States through the Lens of the Prisoners’ Rights Movement,” Journal of American History 102, 1 (June 2015): 73–86Paul Sabin, “Crisis and Continuity in U.S. Oil Politics, 1965–1980,” Journal of American History 99, 1 (June 2012): 177–186Ashley D. Farmer, “”Abolition of Every Possibility of Oppression”: Black Women, Black Power, and the Black Women’s United Front, 1970–1976,” Journal of Women’s History 32, 3 (Fall 2020): 89-114Josiah Rector, “The Spirit of Black Lake: Full Employment, Civil Rights, and the Forgotten Early History of Environmental Justice,” Modern American History 1, 1 (March 2018): 45-66Kathryn Cramer Brownell, “Watergate, the Bipartisan Struggle for Media Access, and the Growth of Cable Television,” Modern American History 2-3 (December 2020): 175-198Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1970sFrost/Nixon (dir. Ron Howard, 2008)Network (dir. Sidney Lumet, 1976)Nashville (dir. Robert Altman, 1975)All the President’s Men (dir. Alan Paluka, 1976)The Candidate (dir. Michael Ritchie, 1972)Saturday Night Fever (dir. John Badham, 1977)WEEK 08 The 1980s—The Rise of the New RightRequired Reading Week 08Bethany Moreton, To Serve God and Walmart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009)Crowdsourced Readings Week 08Daniel T. Rodgers, “Prologue,” Age of Fracture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011)Michael Rogin, “‘Make My Day!’: Spectacle as Amnesia in Imperial Politics,” Representations 29 (Winter, 1990): 99-123Lawrence B. Glickman, “The Liberal Who Told Reagan’s Favorite Joke,” Boston Review, 5 August 2019Lawrence B. Glickman, “How Did the GOP Become the Party of Ideas?,” Boston Review, 9 December 2020Jefferson Cowie and Lauren Boehm, “Dead Man’s Town: ‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ Social History, and Working-Class Identity,” American Quarterly 58, 2 (June 2006)Kevin Mattson, “Remember Punk Rock? Probably Not…: The Real Culture War of 1980s America,” History News Network, 30 August 2020Jonathan Bell, Rethinking the “Straight State”: Welfare Politics, Health Care, and Public Policy in the Shadow of AIDS, Journal of American History 104, 4 (March 2018): 931–952Various authors, “Interchange: HIV/AIDS and U.S. History,” Journal of American History 104, 2 (September 2017): 431–460Kelly Lytle Hernández, Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Heather Ann Thompson, “Introduction: Constructing the Carceral State,” Journal of American History 102, 1 (June 2015): 18–24Donna Murch, “Crack in Los Angeles: Crisis, Militarization, and Black Response to the Late Twentieth-Century War on Drugs,” Journal of American History 102, 1 (June 2015): 162–173

– Kim Phillips-Fein, “Conservatism: A State of the Field,” Journal of American History 98, 3 (December 2011): 723–43Keisha N. Blain, “‘We will overcome whatever [it] is the system has become today’: Black Women’s Organizing against Police Violence in New York City in the 1980s,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 20, 1 (December 2018): 110-121James Morton Turner, “‘The Specter of Environmentalism’: Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right,” Journal of American History 96, 1 (June 2009): 123–148Kathleen Below, “Introduction,” Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), 1-18Laura Smith, “Lone Wolves Connected Online: A History of Modern White Supremacy,” New York Times, 26 January 2021Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1980sDo the Right Thing (dir. Spike Lee, 1989)Roger and Me (dir. Michael Moore, 1989)WEEK 09 The 1990s—America at the end of “The American Century”Required Reading Week 09Lily Geismer, “Agents of Change: Microenterprise, Welfare Reform, the Clintons, and Liberal Forms of Neoliberalism,” Journal of American History 107, 1 (June 2020): 107–131Crowdsourced Readings Week 09Andrew Hartman, “Introduction,” A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015): 1-8Michael Hirsh, “America Adrift: Writing the History of the Post Cold Wars, Review of War in a Time of Peace by David Halberstam,” Foreign Affairs 80, 6 (November-December 2001): 158-164David Fitzgerald, “Support the Troops: Gulf War Homecomings and a New Politics of Military Celebration,” Modern American History 2, 1 (February 2019): 1-22Michelle Alexander, “The New Jim Crow: How the War on Drugs Gave Birth to a Permanent American Undercaste,” Guernica, 9 March 2010 Heather Ann Thompson, “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History,” Journal of American History 97, 3 (December 2010): 703–734María Cristina García, “National (In)security and the Immigration Act of 1996,” Modern American History 1, 2 (April 2018): 233-236Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 1990sBob Roberts (dir. Tim Robbins, 1992)Bulworth (dir. Warren Beatty, 1998)Primary Colors (dir. Mike Nichols, 1998)Fight Club (dir. David Fincher, 1999)WEEK 10 Research WeekFinal Project ProposalWEEK 11 The 2000s—9/11 and Its FalloutRequired Reading Week 11Terry H. Anderson, “9/11: Bush’s Response,” in Beth Bailey and Richard H. Immerman, eds. Understanding the U.S. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (New York: NYU Press, 2015): 54-73Crowdsourced Readings Week 11Michael A. Reynolds, “The War’s Entangled Roots: Regional Realities and Washington’s Vision,” in in Beth Bailey and Richard H. Immerman, eds. Understanding the U.S. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (New York: NYU Press, 2015): 21-49Slavoj Zizek, “The Desert and the Real,” Lacan.com, 17 September 2001 Gary Gerstle, “America’s Neoliberal Order,” in Beyond the New Deal Order: U.S. Politics from the Great Depression to the Great Recession, eds. Gary Gerstle, Nelson Lichtenstein, and Alice O’Connor (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2019): 257-278Thomas Frank, “Lie Down For America,” Harper’s, April 2004, 33-46Thomas Frank, “The Wrecking Crew,” Harper’s, August 2008, 35-45Kelly Lytle Hernández, “Amnesty or Abolition?: Felons, illegals, and the case for a new abolition movement,” Boom: A Journal of California 1, 4 (2011): 54–68Melani McAlister, “A Cultural History of the War without End,” Journal of American History 89, 2 (September 2002): 439–455Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 2000sThe Matrix Trilogy (3 films, dir. The Wachowskis, 1999, 2001, 2003)September 11 Digital ArchiveWEEK 12 The 2010s—Thinking Through The History of the NowRequired Reading Week 12Carlos Lozada, What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020)Lawrence B. Glickman, “Forgotten Men: The Long Road from FDR to Trump, Boston Review, 12 December 2017Crowdsourced Readings Week 12James T. Kloppenberg, “Obama’s American History,” in Reading Obama: Dreams, Hope, and the American Political Tradition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012): 151-248Gary Gerstle, “Civic Ideals, Race, and Nation in the Age of Obama,” in The Obama Presidency: A First Historical Assessment, ed. Julian Zelizer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018): 261-280Peniel E. Joseph, “Barack Obama and the Movement for Black Lives: Race, Democracy, and Criminal Justice in the Age of Ferguson,” in The Obama Presidency: A First Historical Assessment, ed. Julian Zelizer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018): 127-143Sarah R. Coleman, “A Promise Unfulfilled, an Imperfect Legacy: Obama and Immigration Policy,” in The Obama Presidency: A First Historical Assessment, ed. Julian Zelizer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018): 179-194Michelle Alexander, “The Injustice of This Moment Is Not an ‘Aberration’,” New York Times, 17 January 2020Jill Lepore, “The Hacking of America,” New York Times, 14 September 2018George Derek Musgrove, “The Ingredients for ‘Voter Fraud’ Conspiracies,” Modern American History 1, 2 (April 2018): 227-231Julian E. Zelizer, “Tea Partied: President Obama’s Encounters with the Conservative Industrial Complex,” in The Obama Presidency: A First Historical Assessment, ed. Julian Zelizer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018): 11-29Assignment: Weekly Reading Response WorksheetOptional Viewing and Online Resources 2010sThe Facebook Dilemma (dir. James Jacoby, 2018)The Social Dilemma (dir. Jeff Orlowski, 2020)WEEK 13 and 14 ResearchFinal Essay DraftFinal Essay WorkshopsWEEK 15Final Essay Due

Syllabus: The Computerized Society

The scenario of the computerization of the most highly developed societies allows us to spotlight…certain aspects of the transformation of knowledge and its effects on public power and civil institutions—effects it would be difficult to perceive from other points of view.

— Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, 1979

How has the modern computer changed American and global society? In this course, we examine the history of the computer and its contemporary significance by exploring a range of historical sources. We will explore the computer as a technology, but as we do so, we will also pay attention to how the computer is a cultural creation, one linked to issues of politics, economics, law, race, gender, class, and other factors. A particular focus is placed on the hidden history and continued relevance of women in computer history.

Students encounter a wide range of sources in the course, developing skills of critical analysis, communication, and writing through assignments that pair creative responses to computer history with practice at developing evidence-based historical interpretations that are cogent and compelling. Class meetings feature both asynchronous multimedia presentations by the professor with student annotations and extensive discussion—a hybrid of lecture and seminar approaches.

No previous digital or historical training is required, just a curiosity to explore the topic with a commitment to improving your understanding of how the history of computers relates to their contemporary importance in American and global society today. Satisfies I (Contemporary/Integrative Issues) requirement.

What You Will LearnIn this course students:

acquire a deeper historical and cultural understanding of the computer’s significance in American and global life;make integrative, interdisciplinary connections between history of technology, cultural history, film and media studies, gender studies, American studies, sociological, technical, and other approaches to the computer;expand capability to process evidence, information, and arguments from written and visual sources as well as classroom lectures and discussions;sharpen ability to make convincing, compelling, and original evidence-based arguments in dialogue with the interpretations made by others.How This Course WorksThis is a course that combines synchronous and asynchronous learning. The beginning of each week generally features readings, documentary film viewings, and asynchronous lecture material. Annotation assignments help you to do formative assessment of how you are absorbing the course content. Thursdays we convene at class time for discussion of what we are studying together.

That means you need a computer with a camera and microphone or some device that allows you to access the course and a decent Internet connection. Please confer with SUNY Brockport if you do not have access to this equipment and technical requirements. Please show up for class at our regular meeting times (there are a few built-in breaks throughout the semester too). Ideally you can turn your camera on and keep your microphone muted except when you wish to speak. A headset or earbuds with microphone often help a lot too for blocking out extraneous noise. You will also be well-served by finding a quiet, calm place from which to attend class online.

Digital learning during the pandemic is challenging for all of us and I will be as flexible as possible with your particular needs and situations according to SUNY Brockport policy. So long as you are participating in the course in good faith, we can still learn a lot together even though we are doing so under these extraordinary circumstances.

Digital ToolsWe will use a few digital tools in the course to facilitate our study together:

1. Computer with Camera and Microphone/Internet AccessA computer with a camera and microphone or some similar device that allows you to access the course.A decent Internet connection.A headset or earbuds with microphone.A quiet place from which to attend class.2. Canvas (Not Blackboard)I use Canvas instead of Blackboard. In most ways, it works the same as Blackboard, but I think its design, navigation, and performance are far superior. You will receive an invitation to join the course Canvas website at the start of the semester. Think of our Canvas website as the central syllabus, schedule, and assignment submission tool for the course—home base.

3. VoiceThreadVoiceThread delivers course lectures to you digitally. Links will be provided to each lecture on our course Canvas website. There will be required annotation assignments using VoiceThread’s comments function. These allow you to begin to process the primary and secondary sources we will be investigating in the course and set up the writing assignments you will complete in the course.

4. Microsoft WordWe use Microsoft Word, which you can download through Brockport On the Hub, for writing assignments. Occasionally, I also ask you to sketch or draw and use a digital phone or camera to take a photograph of your work to upload along with your essay. either embedded in Microsoft Word or as a separate jpg or pdf file.

5. ZoomWe will use Zoom as our online classroom for synchronous discussions. You can sign up for a free Zoom account if you do not already have one.

6. Additional Digital ToolsWe may employ additional digital tools in the course, such as Perusall or Google Docs. If so, I will provide instructions for how to use them.

If you have questions about the technical requirements for the course, or about the hybrid nature of the course, please feel free to contact me.

ReadingWe will be doing a fair amount of reading and viewing for this course, but we will also work on skills of skimming for key ideas.

WritingWeekly annotation assignments for formative assessment help me to gauge how you are processing and making sense of course content.Four short essays based on course material, each featuring a creative prompt and an analytic component that asks you to wield evidence precisely to make a compelling argument in graceful, stylish prose.A final essay asks you to develop an overarching analytic argument about course content, wielding evidence precisely to make a compelling argument in graceful, stylish prose.DiscussionWe will join together remotely to practice the art and craft of historical discussion: sharing ideas, articulating perspectives, asking good questions, and developing both individual and shared understandings of the past we are studying together.Required MaterialsBlum, Andrew. Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet. New York: HarperCollins, 2012. ISBN-13:978-0061994951Ceruzzi, Paul E. Computing: A Concise History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. ISBN-13: 978-0262517676Wardrip-Fruin, Noahand Nick Montfort, eds. The New Media Reader. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2003.ISBN-13: 978-0262232272Numerous essays, articles, films, and websites on CanvasScheduleWEEK 01 Introduction: The Computerized SocietyRequired Materials Week 01Canvas website, aka the course syllabusRoy Rosenzweig, “Wizards, Bureaucrats, Warriors, and Hackers: Writing the History of the Internet,” American Historical Review 103, 5 (December 1998), 1530-1552James W. Cortada, “Studying History As It Unfolds, Part 1: Creating the History of Information Technologies,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 37, 3 (July-September 2015), 20-31James W. Cortada, “Studying History As It Unfolds, Part 2: Tooling Up the Historians,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 38, 1 (January-March 2016), 48-59Raymond Williams, “The Technology and the Society” (1974), in The New Media Reader, eds. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2003), 289-300Timeline of Computer History, Computer History MuseumAsynchronous: Introduction—The Computerized SocietyMeeting Week 01Assignment: Course Contract and Student Info CardWEEK 02 Early Adventures in ProgrammabilityRequired Materials Week 02Ceruzzi, “Chapter 1: The Digital Age,” 1-21Part 1, “Giant Brains,” The Machine That Changed the World documentary film, dir. Nancy Linde (1992)Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (1950), in The New Media Reader, 49-64Jeff Thompson, “The Physical Infrastructure of Human Computing,” Jeff Thompson website, 5 April 2015Optional: Angela M. Haas, “Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice,” Studies in American Indian Literatures 19, 4 (Winter 2007): 77–100Optional: David Suisman, “Sound, Knowledge, and the ‘Immanence of Human Failure’: Rethinking Musical Mechanization through the Phonograph, the Player-Piano, and the Piano,” Social Text 28, 1 (March 12010): 13–34Asynchronous: Early Adventures in ProgrammabilityMeeting Week 02WEEK 03 Digital Trajectories: The Computer and World War IIRequired Materials Week 03Ceruzzi, “Chapter 2: The First Computers,” 23-48Part 2, “Inventing the Future,” The Machine That Changed the World documentary filmPaul N. Edwards, “Why Build Computers? The Military Role in Computer Research,” in The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 42-73Norbert Wiener, “Men, Machines, and the World About” (1954), in The New Media Reader, 65-72Asynchronous: The Computer As Killing MachineAsynchronous: Giant BrainsMeeting Week 03WEEK 04 Gender, Cold War, and the Early ComputerRequired Materials Week 04Janet Abbate, “Introduction: Rediscovering Women’s History in Computing,” “Chapter 1: Breaking Codes and Finding Trajectories: Women at the Dawn of the Digital Age,” and “Chapter 2: Seeking the Perfect Programmer: Gender and Skill in Early Data Processing,” in _Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computin_g (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 1-72Clive Thompson, “The Secret History of Women in Coding,” New York Times, 13 February 2019Rhaina Cohen, “What Programming’s Past Reveals About Today’s Gender-Pay Gap,” The Atlantic, 7 September 2016Jennifer Light, “When Computers Were Women,” Technology and Culture 40, 3 (1999): 455-483Barkley Fritz, “The Women of ENIAC,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 18, 3 (1996), 13-28Asynchronous: Gender and the Early Computer—The Women of ENIAC and NASAMeeting Week 04Assignment: What is the Contemporary Relevance of Computer History?WEEK 05 Cold War Electronic BattlefieldRequired Materials Week 05Paul Edwards, “‘We Defend Every Place’: Building the Cold War World,” in The Closed World, 1-41Paul Edwards, “Sage” in The Closed World,” in The Closed World, 74-111Dr. Strangelove, or How I Stopped Worrying And Learned to Love the Bomb, dir. Stanley Kubrick (1964)Ceruzzi, “Chapter 3: The Stored Program Principle,” 49-80Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic (July 1945), in The New Media Reader, 35-48JCR Licklider, “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” The Transaction of Human Factors in Electronics (March, 1960), 4-11, in The New Media Reader, 73-82Optional: Jill Lepore, “Project X,” The Last Archive podcastAsynchronous: The Cold War’s Electronic BattlefieldAsynchronous: From Giant Brains to Man-Computer Symbiosis?WEEK 06 The Cold War and Democratic PersonalityRequired Materials Week 06Fred Turner, “The Cold War and the Democratic Personality,” in The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 151-180Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium is the Message” (1964, from Understanding Media) and “The Galaxy Reconfigured or the Plight of Mass Man in an Individualist Society (1969, from The Gutenberg Galaxy),” The New Media Reader, 193-210David C. Brock, “Meeting Whirlwind’s Joe Thompson,” Computer History Museum Blog, 20 February 2019Donna J. Drucker, “Keying Desire: Alfred Kinsey’s Use of Punched-Card Machines for Sex Research,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 22, 1 (January 2013), 105-125Mar Hicks, “The Mother of All Swipes: A working-class woman from East London invented computer dating more than half a century ago,” Logic 2 (1 July 2017)Joy Lisi Rankin, “Tech-Bro Culture Was Written in the Code,” Slate, 1 November 2018Robert McMillan, “Her Code Got Humans on the Moon—And Invented Software Itself,” *Wired*, 13 October, 2015Hidden Figures, dir. Theodore Melfi (2016)Asynchronous: The Cold War and the Democratic PersonalityAsynchronous: Sex, Statistics, and PunchcardsMeeting Week 06WEEK 07 Knowledge Workers in the “Information Economy”Required Materials Week 07Desk Set, dir. Walter Lang (1957)Andrew Utterson, “Computers in the Workplace: IBM and the ‘Electronic Brain’ of Desk Set,” in From IBM to MGM: Cinema At the Dawn of the Digital Age (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 16-32Steven Lubar, “Do Not Fold, Spindle, or Mutilate: A Cultural History of the Punch Card,” Journal of American Culture 15, 4 (Winter 1992), 43-55Jill Lepore, “How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future,” New Yorker, 3/10 August 2020Optional: Jill Lepore, “_The Computermen,” _The Last Archive podcastAsynchronous: Computers in the WorkplaceAsynchronous: Automation and Its DiscontentsMeeting Week 07Assignment: Gender and the Computer Op-EdWEEK 08 Rise of Silicon Valley—Integrated Circuits, Operating Systems, and Beanbag CapitalismRequired Materials Week 08Ceruzzi, “Chapter 4: The Chip and Silicon Valley,” 81-97 and “Chapter 5: The Microprocessor,” 99-119Lisa Nakamura, “Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture,” American Quarterly 66, 4 (December 2014): 919-941Lisa Nakamura, “Indigenous Circuits,” Computer History Museum Website, 2 January 2014Tara McPherson, “U.S. Operating Systems at Mid-Century: The Intertwining of Race and UNIX,” in Race After the Internet, eds. Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White (New York: Routledge, 2012), 21-37Fred Turner, “The Shifting Politics of the Computational Metaphor” and “Stewart Brand Meets the Cybernetic Counterculture,” in From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 11-39, 41-68Stewart Brand, “Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums,” Rolling Stone 7 December 1972Richard Brautigan, All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace poemOptional: Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), “Technology and Ethos,” Raise Race Rays Raze: Essays Since 1965 (New York: Random House: 1969), 155-157Optional: Silicon Valley, dir. Randall MacLowry and Tracy Heather Strain (2013)Optional: Douglas Engelbart, From Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework (1962), in The New Media Reader, 93-108Optional: Theodor H. Nelson, From Computer Lib / Dream Machines (1970-1974), in The New Media Reader, 301-338Optional: Joan Greenbaum, “Questioning Tech Work: Computer People for Peace,” AI Now Institute, 31 January 2020Asynchronous: Integrated Circuits as Culture, Culture as an Operating SystemAsynchronous: Beanbag Capitalism—From Computing to Communication and Business Culture to Counterculture (and Counterculture as Business Culture!)Meeting Week 08WEEK 09 Rise of the “Personal” ComputerRequired Materials Week 09Paul Ceruzzi, “Inventing Personal Computing” in The Social Shaping of Technology, eds. Donald MacKenzie and Judy Wajcman (Philadelphia: Open University Press, 1999), 64-86David Sims, “How Apple and IBM Marketed the First Personal Computers,” The Atlantic, 17 June 2015Meryl Alper, “‘Can Our Kids Hack It With Computers?’ Constructing Youth Hackers in Family Computing Magazines (1983–1987),” International Journal of Communication 8 (2014), 673–698William F. Vogel, “‘The Spitting Image of a Woman Programmer’: Changing Portrayals of Women in the American Computing Industry, 1958-1985,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 39, 1 (July 2017), 49-64War Games, dir. John Badham (1983)Optional: Episode 576: When Women Stopped Coding,” Planet Money, 17 October 2014Optional: 8 Bit Generation: The Commodore Computer Wars, dir. Tomaso Walliser (2016)Optional: Silicon Cowboys, dir. Jason Cohen (2016)Optional: Halt and Catch Fire, Seasons 1 and 2, created by Christopher Cantwell and Christopher C. Rogers (2014-2015)Asynchronous: Care For a Nice Game of Chess? The Rise of the “Personal” ComputerAsynchronous: 1984Meeting Week 09WEEK 10 Rise of the InternetRequired Materials Week 10John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” (1996)Ceruzzi, “Chapter 6: The Internet and the World Wide Web,” 121-154Janet Abbate, “Privatizing the Internet: Competing Visions and Chaotic Events, 1987-1995,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 32, 1 (January- March 2010), 10-22The Machine That Changed the World documentary film, dir. Nancy Linde (1992), Part 4, “The Thinking Machine”Martin Dodge, An Atlas of Cyberspaces, 1997-2004Internet History, 1962-1992, Computer History Museum WebsiteOptional: Halt and Catch Fire, Seasons 3 and 4, created by Christopher Cantwell and Christopher C. Rogers (2016-2017)Asynchronous: The Rise of the InternetMeeting Week 10WEEK 11 Tubes: A Material History of the InternetRequired Materials Week 11Andrew Blum, Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 1-103The Machine That Changed the World documentary film, dir. Nancy Linde (1992), Part 5, “The World at Your Fingertips”Christine Smallwood, “What Does the Internet Look Like,” The Baffler 18 (December 2009), 8-12Tim Berners-Lee, Robert Cailliau, Ari Loutonen, Henrik Frystyk Nielsen and Arthur Secret, “The World Wide Web” (1994), in The New Media Reader, 791-798Katrina Brooker, “‘I Was Devastated’: Tim Berners-Lee, the Man Who Created the World Wide Web, Has Some Regrets,” Vanity Fair, 1 July 2018Asynchronous: A Squirrel Ate Your InternetMeeting Week 11Assignment: The Past and Future of the “Personal” Computer—Design a New “Personal” Computer for AppleWEEK 12 Search Engine: Ethics and Power in the Algorithmic SocietyRequired Materials Week 12Siva Vaidhyanathan, “Introduction: The Gospel of Google” and “Render unto Ceasar: How Google Came to Rule the Web,” The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry) (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), xi-50Siva Vaidhyanathan, “Welcome to the Surveillance Society,” IEEE Spectrum, June 2011, 48-51The Matrix, dir. Lana and Lilly Wachowski (formerly the Wachowski Brothers) (1999)Jaron Lanier, “The Online Utopia Doesn’t Exist. We Need to Reboot,” Wired, 5 April 2013Jaron Lanier, “Fixing the Digital Economy,” New York Times, 8 June 2013Jaron Lanier, “Digital Passivity,” New York Times, 27 November 2013Optional: Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World, dir. Werner Herzog (2016)Optional: Terms and Conditions May Apply, dir. Cullen Hoback (2013)Optional: The Matrix Reloaded (2003); The Matrix Revolutions (2003)Asynchronous: The Googlization of EverythingAsynchronous: Who Owns the Future?Meeting Week 12WEEK 13 Crises of a Computerized DemocracyRequired Materials Week 13Siva Vaidhyanathan, “Introduction: The Problem with Facebook is Facebook,” Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019): 1-30Zeynep Tufekci, “The Latest Data Privacy Debacle,” New York Times, 30 January 2018Zeynep Tufekci, “Facebook’s Surveillance Machine,” New York Times, 19 March 2018Zeynep Tufekci, “We Already Know How to Protect Ourselves From Facebook.” New York Times, 9 April 2018Zeynep Tufekci, “The Looming Digital Meltdown, New York Times, 6 January 2018Sheera Frenkel, Nicholas Confessore, Cecilia Kang, Matthew Rosenberg and Jack Nicas, “Delay, Deny and Deflect: How Facebook’s Leaders Fought Through Crisis,” New York Times, 14 November 2018Nicholas Confessore and Matthew Rosenberg, “Sheryl Sandberg Is Said to Have Asked Facebook Staff to Research George Soros,” New York Times, 29 November 2018Gabriel J.X. Dance, Michael LaForgia and Nicholas Confessore, “As Facebook Raised a Privacy Wall, It Carved an Opening for Tech Giants,” New York Times, 18 December 2018Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Natasha Singer, Michael H. Keller, and Aaron Krolik, “Your Apps Know Where You Were Last Night, and They’re Not Keeping It Secret,” New York Times, 10 December 2018Philip E. Agre, “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy” (1994), in The New Media Reader, 737-760Kashmir Hill, “I Tried to Live Without the Tech Giants. It Was Impossible,” New York Times, 31 July 2020Safiya Umoja Noble, “Social Inequality Will Not Be Solved By an App,” Wired, 4 March 2018Zeynep Tufekci, “What Happens to #Ferguson Affects Ferguson: Net Neutrality, Algorithmic Filtering and Ferguson,” The Message, 14 August 2014Optional: Jaron Lanier, “How to Think about Privacy,” Scientific American 309, 5 (November 2013), 64-71Optional: Sue Halpern, “Are We Puppets Yet in a Wired World?,” New York Review of Books, 7 November 2013, 24-28Optional: Brendesha M. Tynes, Joshua Schuschke, and Safiya Umoja Noble, “Digital Intersectionality Theory and the #Blacklivesmatter Movement,” in __The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online_, eds. Brendesha M. Tynes and Safiya Umoja Noble (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2015), 21-40Optional: Ali Colleen Neff, “Digital, Underground: Black Aesthetics, Hip Hop Digitalities, and Youth Creativity in the Global South,” The Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music, eds. Justin D. Burton and Jason Lee Oakes (Oxford University Press, 2018)Optional: Coded Bias, dir. Shalini Kantayya (2020)Optional: The Facebook Dilemma, dir. James Jacoby (2018)Optional: Her, dir. Spike Jonze (2013)Optional: The Circle, dir. James Ponsoldt (2017)Asynchronous: The Facebook Dilemma—The Privacy CrisisAsynchronous: #BlackLivesMatter: Race Online and OffMeeting Week 13Assignment: The Past and Future of the Internet—Pitch a Matrix RemakeWEEK 14 All Watched Over By Machines (Of Loving Grace?)Required Materials Week 14Ceruzzi, “Chapter 7: Conclusion,” 155-159Zeynep Tufekci, “YouTube, the Great Radicalizer,” New York Times, 10 March 2018Zeynep Tufekci, “Russian Meddling Is a Symptom, Not the Disease,” New York Times, 3 October 2018Emilio Ferrara, “How Twitter Bots Affected the US Presidential Campaign,” The Conversation, 8 November 2016, updated 16 February 2018John Naughton, “Has the Internet Become a Failed State?,” The Guardian, 27 November 2016Jill Lepore, “The Hacking of America,” New York Times, 14 September 2018Tim Berners-Lee, “I Invented the World Wide Web. Here’s How We Can Fix It,” New York Times, 24 November 2019Optional: All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, dir. Adam Curtis (2011)Part 1, Love and Power: The Influence of Ayn RandPart 2, The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts: Ecology, Technology, and SocietyPart 3, The Monkey in the Machine and the Machine in the Monkey: The Selfish GeneOptional: Hacking Democracy, dir. Simon Ardizzone and Russell Michaels (2006)Optional: The Social Dilemma, dir. Jeff Orlowski (2020)Asynchronous: Hacking DemocracyAsynchronous: All Watched Over By Machines (of Loving Grace)?Meeting Week 14WEEK 15 Final EssayAssignment: Final Essay—What is the Contemporary Relevance of Computer History?Syllabus: Modern America

In this course we explore US history since the Civil War ended in 1865. Yes, the course will ask you to learn about names and dates. Those are the basic building blocks of understanding the past. But that’s just the beginning of what it means to study history! History, it turns out, isn’t just names and dates. Not at all. The past may be a big mess of names and dates, but history is about how we try to make sense of that big mess, how we organize it selectively, and how we must forge a clarifying path through the sprawl of the past by deciding what matters the most, how it matters, and why it matters. So, yes there are names and dates, but history is most of all about the craft of developing evidence-based interpretations of the past that are in conversation with other, competing, evidence-based interpretations. One might even say that history is one big, ongoing argument about what happened. Welcome to the conversation. Studying history will help you ground your sense of what it means to be alive in 2021 by understanding better some of the story of how we got here. Studying history will help you improve your ability to handle complexity of information. You will improve your capacity to read and process materials more critically and accurately. And you will be able to work on your skills of analytic writing, communication, and expression by practicing how to be more precise in how you develop an interpretation inductively from your close, critical readings of evidence.

What You Will LearnIn this introductory history course, you will:

learn about historical facts (the names and dates) concerning US history since 1865learn about historical interpretations concerning US history since 1865explore larger questions of what history is and how it matters to your lifeHow will we do this, you ask? By engaging wholeheartedly with the material in this course:

You’ll become a better thinker, writer, and speaker.You’ll be able to handle complexity of evidence and organize facts into a narrative and an argument.Some of you might even decide to become history majors or minors.Others of you will carry what you learn in this class into other courses, activities, jobs, personal experiences, and your important civic role in the United States.You will learn:

what happened when and who did it in the American past.why it matters, what the stakes are of the American past.how to notice and analyze change and continuity over time.how to notice and analyze structures of power, how they have developed over time, and why.how to handle historical complexity through close analysis, paraphrasing, and interpretive questioning.how others have interpreted and debated the past (what we call historiography).how to describe this historiography accurately and put different interpretations into conversation with each other.how to frame your own historical questions.how to develop close, accurate, compelling interpretations of historical evidence yourself.how to improve your skills of developing a historical narrative.how to use evidence to develop a historical thesis, an argument-driven, evidence-based historical narrative.how to position your historical thesis in relation to historiographical debates, or the disagreements other historians have had about the past.how to paraphrase effectively.how to use source citation using Chicago Manual of Style effectively and accurately.By exploring how our world came to be, the study of history fosters the critical knowledge, breadth of perspective, intellectual growth, and communication and problem-solving skills. These will help you lead a purposeful life, become an active citizen, and achieve career success.

How This Course WorksThis is a hybrid online course. That means it is partly asynchronous and self-directed. You will complete reading and writing assignments on your own, independently, following the deadlines listed on the course website. We also meet synchronously, once a week, to discuss what we are studying together. These are required meetings. Synchronous meetings mean you need a computer with a camera and microphone or some device that allows you to access the course and a decent Internet connection. Please confer with SUNY Brockport if you do not have access to this equipment and technical requirements. Please show up for class at our regular meeting times (there are a few built-in breaks throughout the semester too). Ideally you can turn your camera on and keep your microphone muted except when you wish to speak. A headset or earbuds with microphone often help a lot too for blocking out extraneous noise. You will also be well-served by finding a quiet, calm place from which to attend class online.

Digital learning during the pandemic is challenging for all of us and I will be as flexible as possible with your particular needs and situations according to SUNY Brockport policy. So long as you are participating in the course in good faith, we can still learn a lot together even though we are doing so under these extraordinary circumstances.

Digital ToolsWe will use a few digital tools in the course to facilitate our study together:

1. Computer with Camera and Microphone/Internet AccessA computer with a camera and microphone or some similar device that allows you to access the course.A decent Internet connection.A headset or earbuds with microphone.A quiet place from which to attend class.2. Canvas (Not Blackboard)I use Canvas instead of Blackboard. In most ways, it works the same as Blackboard, but I think its design, navigation, and performance are far superior. You will receive an invitation to join the course Canvas website at the start of the semester. Think of our Canvas website as the central syllabus, schedule, and assignment submission tool for the course—home base.

3. VoiceThreadVoiceThread delivers course lectures to you digitally. Links will be provided to each lecture on our course Canvas website. There will be required annotation assignments using VoiceThread’s comments function. These allow you to begin to process the primary and secondary sources we will be investigating in the course and set up the writing assignments you will complete in the course.

4. Microsoft WordWe use Microsoft Word, which you can download through Brockport On the Hub, for writing assignments.

5. ZoomWe will use Zoom as our online classroom for synchronous discussions. You can sign up for a free Zoom account if you do not already have one.

6. Additional Digital ToolsWe may employ additional digital tools in the course, such as Perusall or Google Docs. If so, I will provide instructions for how to use them.

If you have questions about the technical details of the course, or about the hybrid nature of the course, please feel free to contact me.

ReadingWe will be doing a fair, but manageable amount of reading and viewing for this course.