Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 38

August 23, 2020

Contemporary Dance Investigating Social Dance Investigating Contemporary Dance

One of the great turns in contemporary visual art over the last fifty years has been toward a fascination with embodiment. Performance art as a key example of this. This interest has pushed the visual arts world closer to contemporary dance. One of the great strengths of contemporary dance, however, is precisely not embodiment, but rather abstraction. Whether on a proscenium stage or in site-specific setting, contemporary dance does not really blur art into life. Instead, it harnesses gesture, movement, and performance for intellectual contemplation and reflection. It does not necessarily use spoken or written language, but it is philosophy.

To be sure, contemporary dance is also many other things, lots of them contested, but in watching Doug Elkins Choreography, Etc.’s wonderful “Scott, Queen of Marys,” recorded in 2012 and screening at the PlayBAC series from Baryshnikov Arts Center until August 25, 2020, the power of contemporary dance’s capacity for abstraction stood out to me most of all.

Elkins’ “Scott, Queen of Marys” is a deeply playful meditation on social dance. It was originally created and performed in 1994. The piece incorporates references to voguing, tutting, breakdance, English country dance, modern dance, and more, always with an eye toward heightening awareness of—and generating implicit (and sometimes quite obvious) commentary on—the implications of social dance. Elkins and dancers provide captivating choreography and performance with these moves while also continually asking the audience to draw back a moment with them to observe social dance and its dynamics askew, askance, anew. Two steps forward one step back. Maybe even one step forward two steps back. Contemporary dance is investigatory. It performs and watches itself performing all at the same time.

There is something doubly funny going on in this respect with “Scott, Queen of Marys.” The social dances themselves that the piece contemplates already contain a level of contemplation. Which is to say, they already contain moments of abstraction, irony, and virtuosic physicality coupled with expressive signaling that the dancer is well aware of the social relations, historical legacies, interpersonal negotiations, and power dynamics in which the dancing is located. Voguing, for instance, already uses abstraction, slicing up moments of stillness and flow, appropriating gestures from Hollywood starlets, the fashion show, and the House Music dance floor into movement that demands attention and provides reflection and commentary all at once.

So this kind of abstraction is already present in many types of social dance. But contemporary dance really focuses on it as a mode. If one locates the origins of contemporary dance in Anna Halprin’s experiments out West and the Judson Theater scene in downtown New York City, it was always in conversation with social dance and also with the mundane movements of everyday life. Crucially, it sought not to merely dissolve art into them, but rather to draw attention to social life and the everyday aesthetically and ethically. And to do so with great force and beauty. If contemporary visual artists wanted to take paint beyond the canvas, contemporary dance wanted to frame the world and the way we move through it so that we could contemplate it more profoundly.

In the 2012 version of “Scott, Queen of Marys,” with its clever title inversion already signaling a kind of abstraction, the ostensible “queen” is Javier Ninja (b. Javier Madrid), who moves his arms in all kinds of impressive contortions around and behind his head, sways his hips, and compellingly holds center stage while striking one pose after another. He exudes the confident jousting of the Harlem Ballroom Scene, bringing it into the contemporary dance setting, at times almost seeming to throw shade on the entire production and its audience, at other times basking in the glow of a transposed setting.

Ninja comes from more recent generations of the underground voguing houses first brought to greater attention by the 1990 documentary film Paris Is Burning. While the documentary film rather exoticized performers in the subaltern world of voguing, “Scott, Queen of Marys” brings Javier Ninja into a continuum of social dance. Voguing turns seamlessly into two-stepping into English country dancing into b-boy breakdancing, whose gendered forms are then fabulously abstracted through reversal, particularly by Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie, who identifies as a b-girl, and Cori Marquis. They take on the masculine roles of classic breakdance posturing, grabbing their crotches, nodding their heads, popping and locking, symbolically thrusting their groins into the upraised booties of male dancers.

There are even some moments in “Scott, Queen of Marys” when moves from modern and contemporary dance appear: more upright spines, unison ensemble choreography, and the carving up of stage space with side lifts and turns that are descended from, but also rebelling against, the formalities of ballet. Only now, within the established scheme and mood of the piece, it is almost as if we are watching contemporary dance investigating social dance investigating contemporary dance. Who’s the queen now?

With “Scott, Queen of Marys,” Elkins and his dancers do not ask us to dissolve the boundaries between the immersive, informal worlds of social dance (themselves already containing their own modes of abstraction and self-awareness) and the more formalized spaces and assumptions of contemporary concert dance. Instead, he and his company refract and replay social dance, defamiliarizing it, investigating it, moving it this way and that, stepping just to the side of it, entering into it only to step out of it again, doubling it back on itself, and even turning social dance’s attention to modern and contemporary dance so as to invert the power of who’s gazing whom, calling into question the hierarchies of elite art worlds and social dance settings.

Elkins and his group bring us closer to social dance’s power and, simultaneously, further away from it to a perspective of observation and commentary. Art does not blur life, rather life comes through more clearly under the magnifying glass of art. Elkins and company most of all dance on the line between art and life, holding forth there, motioning to us: hey, people, come over, take a look, and think about this.

August 22, 2020

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival on KPIX News in 1968

KPIX News report by Ed Arnow from July 6th 1968 explains:

They say folk music is the music of the people, and different people sure approach folk music differently. Here in the University of California’s Lower Plaza we sure have an assortment [that’s Lower Sproul Plaza I believe].

Among others who appear, Mitch Greenhill talks about folk music, the always-marvelous Sam Hinton plays some “real orthodox” instruments, and Allan MacLeod performs a Scottish ballad. The music is “weird,” as one performer says, and in 1968, of course (and maybe still) that was a good thing!

One side note on the 1968 Festival is the remarkable fact that director Barry Olivier and his staff brought it off without any disruptions as protests turned into skirmishes with the police just a few blocks away on Telegraph Avenue. More of this and many other stories in the upcoming Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project.

The footage is now digitized from deep in the vaults of the Bay Area Television Archives at San Francisco State University’s J. Paul Leonard Library’s Department of Special Collections.

August 3, 2020

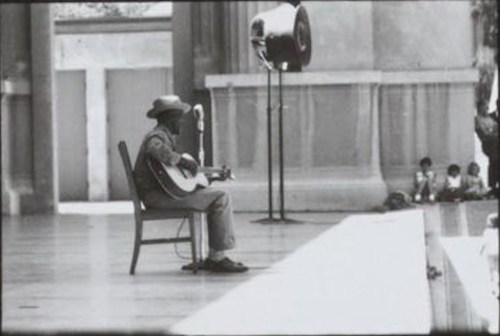

Mance Lipscomb @ the 1961 Berkeley Folk Music Festival

Mance Lipscomb @ the 1961 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert in the Greek Amphitheater, University of California campus. Photograph: Cliff Soubier.

Mance Lipscomb @ the 1961 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert in the Greek Amphitheater, University of California campus. Photograph: Cliff Soubier. Mance Lipscomb @ the 1961 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert in the Greek Amphitheater, University of California campus. Photograph: Cliff Soubier.

Mance Lipscomb @ the 1961 Berkeley Folk Music Festival Jubilee Concert in the Greek Amphitheater, University of California campus. Photograph: Cliff Soubier.Check out Mance’s performance recorded at FolkSeattle.

And Les Blank’s documentary film, A Well Spent Life.

August 1, 2020

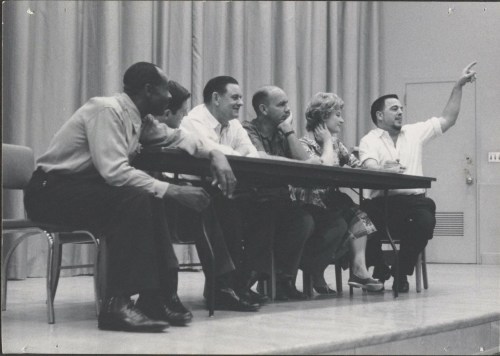

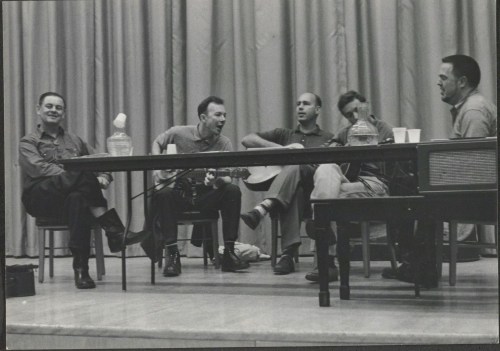

Talkin’ Folk Music—Panel Discussions @ the 1959 Berkeley Folk Music Festival

Research continues on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project.

Jesse Fuller, Merritt Herring, Jimmy Driftwood, Sam Hinton, Shirley Collins, and Alan Lomax, Panel Discussion, 1959 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: P. Olivier.

Jesse Fuller, Merritt Herring, Jimmy Driftwood, Sam Hinton, Shirley Collins, and Alan Lomax, Panel Discussion, 1959 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: P. Olivier. Jimmy Driftwood, Pete Seeger, Sam Hinton, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Alan Lomax, Panel Discussion, 1959 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: P. Olivier.

Jimmy Driftwood, Pete Seeger, Sam Hinton, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Alan Lomax, Panel Discussion, 1959 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo: P. Olivier.

July 31, 2020

Rovings

Sounds

Elizabeth A. Baker, Dreamscape, Experimental Sound Studio Quarantine ConcertsKentucky Colonels, The New Sound of Bluegrass America (1963), Long Journey Home (1964)Scotty Stoneman and the Kentucky Colonels, 1965 Live in L.A.“Breaking Down The Legacy Of Race In Traditional Music In America,” NPR, 25 July 2020

Words

Deborah Coen, Climate in Motion: Science, Empire, and the Problem of ScaleIan McEwan, Machines Like MeVivian Gornick, The Romance of American Communism

“Walls”

Into the Void: Prints of Lee Bontecou, Art Institute of Chicago Al Taylor: Early Paintings Dwan Gallery: Los Angeles to New York, 1959–1971, National Gallery of Art (exhibition catalog)Another Idea, Gray Center for Arts & Inquiry

“Stages”

Aszure Barton, Over/Come (2005) Studio Showing, Rudolf Nureyev Studio, PlayBAC 2Company SBB//Stefanie Batten Bland, A Place of Sun (2012), PlayBAC 2Richard II, Public Theater and WNYCJohn Szwed, “Town Hall on Alan Lomax”

Screens

Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories, Seasons 1-3The Bureau, Season 1

July 24, 2020

Rovings

Sounds

The Californian Century, BBC Radio 4Nina, RadiolabThe Mekons, ExquisiteBob Dylan, Rough and Rowdy WaysChris Corsano, Everything About It Video (excerpt) (h/t Jesse Jarnow)Neil Young and the Stray Gators, TuscaloosaRoscoe Mitchell, SplatterDirty Projectors, Flight Towerboygenius, boygenius ep (h/t Alison Bartolone)

Words

Homi Bhaba, “Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority under a Tree outside Delhi, May 1817,” Critical Inquiry 12, 1 (Autumn, 1985), 144-165Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native StudiesIsaiah Berlin, Historical InevitabilityRobert Musil, “On Stupidity”Maria Golia, Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the AdventureTomeka Reid, “On Onomatopoeia”Steffani Jemison with Garrett Gray, “On Similitude”

“Walls”

Cauleen Smith, Human_3.0 Reading ListThe Drawings of Al Taylor, Morgan Library and MuseumJean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect. Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Morgan Library and MuseumAlfred Jarry: The Carnival of Being, Morgan Library and MuseumArthur Jafa, Love is the Message, The Message is Death

“Stages”

Rennie Harris PureMovement, History of Hip Hop, Bates Dance FestivalPivot Arts Festival, Un(Touched)Irene Hsiao, Score for an Unfinished DanceRed Clay Dance, Re-Imagined ResilienceKathryn Hamilton/Sister Sylvester, “Halobiont”Ron Brown, EvidenceBruce Molsky @ The Old Tone Music Festival

Screens

Hunters Little Drummer Girl Marshall McLuhan, “Living in an Acoustic World,” University of South Florida, 1974

July 10, 2020

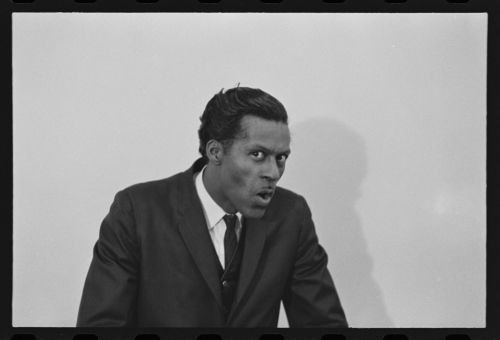

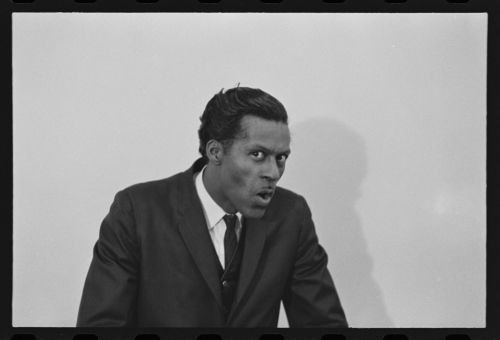

Chuck Berry @ the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival

A few of the wonderful performance and portrait shots of Chuck Berry at the Berkeley Blues Festival, 27 February 1965, from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection. These were likely taken by Berkeley Folk Music Festival director and amateur photographer Barry Olivier.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Blues Festival ’65 Handbill. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Blues Festival ’65 Handbill. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival program. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

1965 Berkeley Blues Festival program. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Full program

Hear Chris Strachwitz discuss Berry’s West Coast visit in 1965

Chris Strachwitz—Arhoolie Records proprietor, vernacular music collector, anti-Mickey Mouse music proponent, and 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival co-producer—on Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival and his visit out on the West Coast that year.

Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival

A few of the wonderful performance and portrait shots of Chuck Berry at the Berkeley Blues Festival, 27 February 1965, from the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection. These were likely taken by Berkeley Folk Music Festival director and amateur photographer Barry Olivier or the photographer Kelly Hart.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry performing at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Chuck Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival. Photographer probably Barry Olivier or Kelly Hart. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Blues Festival ’65 Handbill. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Blues Festival ’65 Handbill. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival program. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

1965 Berkeley Blues Festival program. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Full program

Hear Chris Strachwitz discuss Berry’s West Coast visit in 1965

Chris Strachwitz—Arhoolie Records proprietor, vernacular music collector, anti-Mickey Mouse music proponent, and 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival co-producer—on Berry at the 1965 Berkeley Blues Festival and his visit out on the West Coast that year.

June 30, 2020

Courses

Modern America: Freedom Dreams and Multiracial Democracy (US History Since 1865)US History Since 1893US History Since 1945US Cultural History, Civil War to the PresentUS Intellectual History, Civil War to the PresentAmerican Studies: An IntroductionUS Labor HistoryAfrican-American HistoryUS History of Technology

US and Transnational History Topics

The Sixties in the US and the WorldPopular Culture and American HistoryUS Popular Music: A Cultural HistoryWhat Is Hip? The History of Bohemianism in AmericaAmerican Culture in the World, 1776-2001A History of Capitalism in AmericaSensory History: Feeling the PastCitizenship and the Public Sphere in Historical PerspectiveCultural Analysis: An IntroductionThe History of History: Methodologies of Historical Inquiry

Digital History, History of Technology & Digital Humanities

The Computerized Society: Cultural History of the ComputerApproaching Digital Humanities: An IntroductionApproaching Digital History: An IntroductionHistorical Methods for Digital ProjectsDigitizing Folk Music HistoryWriting Digital Cultural Criticism

Public History and Civic Engagement Courses

Public History: An IntroductionCommunity in the United States: The History of a Concept and PracticeThe Challenge of the Citizen-Scholar: Civic Engagement and Public HumanitiesHistorians Working with Artists and Writing About the Arts

Teaching Philosophy

My goal as a teacher is to help students develop skills of analysis and communication grounded in a deeper understanding of the past. I place questions of identity, social position, and power—of race, class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, region, nation, and the global—in relation to aesthetic form, economic structure, and political ideologies and practices. A consistent theme in all my courses is engagement with a wide range of primary source evidence: students work not only work with written texts, but also with music, film, radio, television, maps, speeches, architecture, urban space, material culture, and visual artifacts. Then, through multimedia-based lectures, classroom activities, field trips, guest speakers, and digital projects, students and I contextualize source materials by applying different methodological approaches, examining past historiographical debates, and linking classroom study to broader issues of public life.

I believe the classroom can be a far richer environment if it moves beyond the standard lecture format. In my courses, students conduct interviews, develop websites and audio podcasts, attend intellectual events of interest, go on field trips, and even role-play and act out the past themselves. For example, to investigate industrialization in the United States during the late-nineteenth century, my students break up into three groups—upper-class owners, working-class laborers, and middle-class managers—to debate the question “Who built America?” Utilizing materials they have read and studied, each group of student makes their case. Once, my “working-class laborers” went so far as to stage a strike and walk out of the classroom.

I have also grown interested in how to teach effective historical writing. In my United States History Since 1865 course, I work to develop a set of related assignments that serve as building blocks toward a final essay. Students move through assignments on the component parts of a successful piece of analytic writing: a thesis; a successful body paragraph that analyzes evidence; introduction; conclusion; and transitions between sections of an essay. As they work on these smaller assignments, students receive feedback on their writing. The assignment culminates in a final essay in which students put together the materials and the writing skills they worked on during the term.

More recently, I have explored the use of digital tools for historical study: students in my methods and research seminars on digital history use annotation software, database design, computational analysis, mapping, visualization strategies, glitching experiments, and multimedia storytelling tactics for both historical analysis of evidence and the communication of findings to fellow scholars and broader public audiences. Students investigate how digital technologies reinvigorate core historical questions. They complete assignments that help them better track the movement from evidence to interpretation; and they deepen skills of expressing evidence-based arguments in more dynamic and effective prose as well as in new multimedia forms. In my digital pedagogy, technology often becomes a way not of speeding up, but rather of slowing down the analytic and communicative processes so that students can begin to examine and improve their skills and capacities for conveying information and meaning.

For instance, in a course called Digitizing Folk Music History, students develop interpretive digital research projects based on primary sources in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection at Northwestern University. Students not only acquire digital skills and literacy in the course and learn more about the folk music revival and American cultural history, they also confront basic methodological questions in historical scholarship: how does one frame a research question, describe existing interpretations, and offer new analysis based on archival sources? Helping students to think about these questions, my digital history course looks toward future ways of doing history digitally while also emphasizing that this future circles back to core skills and practices of historical study. In service of this dialectic between past and future, I also teach a history of technology course on the history of the computer itself. By applying digital tactics to historical inquiry and, simultaneously, rooting digital technologies themselves in historical context, we can help students better navigate today’s disorienting wireless world.

I have also worked extensively with graduate students in both traditional PhD programs and in more non-traditional adult education settings. I encourage graduate students to delve into both primary sources and historiographical debates through intensive reading, discussion, and writing. I have overseen thesis projects on a range of topics: American nurses in the Vietnam War; the development of Old Town as a countercultural neighborhood in 1960s Chicago; the emergence of the contemporary craft movement; portrayals of the Civil War in high school textbooks; “scramble” marching bands at US universities in the 1960s; and muckraking novels during the Progressive Era. Interacting with and mentoring graduate students has been one of my most rewarding intellectual experiences as a teacher and scholar. Most recently, I have introduced a course, Introduction to Cultural Analysis, in which graduate students draw upon a wide range of intellectual sources to help access different theoretical approaches that can enhance particular research interests.

My teaching also extends beyond the classroom. Museums, historical societies, outside speakers, film screenings, plays, concerts, dance companies, and other institutions and events provide new pathways to knowledge. For instance, I work as a historian-in-residence and dramaturg for a contemporary dance company in Chicago, helping to facilitate conversations on college campuses between the ensemble’s research-driven performance and departments far beyond the dance world. At Northwestern, I helped to conceptualize the Graduate Engagement Opportunities field study program and taught a public humanities seminar, The Challenge of the Citizen-Scholar, that accompanied graduate internships and fieldwork. And in a course I taught on the cultural history of the Americas, students and I traveled to Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art to learn about an exhibition focused on the Brazilian Tropicalia arts movement; meeting with the show’s curator, students learned about the decisions that determined which art objects were chosen and why; the class had an opportunity to see how the history of Tropicalia—its controversial aesthetics and continued political relevance in Brazil—affected the creation of a contemporary museum exhibition. I have also developed a course in digital cultural criticism and museum studies in which students meet with curators, read historical examples of critical writing, and write in digital modes about contemporary art, performance, culture, and politics.

Overall, my approach to teaching encourages students to grapple with the meaning of history as both a specialized area of scholarly inquiry and a foundation from which to address pressing issues in contemporary life. Whether in methodological, historiographical, or topical courses, I help students bring together primary materials, absorb existing scholarly debates, raise relevant questions, map out explanatory problems and quandaries, connect the classroom to public life, and improve their skills of communication. I work to foster an inclusive atmosphere in which students can discover and relish history as a deeply relevant field of intellectual inquiry. At its best, my classroom becomes an active community of practice in which students improve their capacities for research, writing, acts of generous listening, the cogent expression of evidence-based arguments, and sharpened senses of critical awareness.