Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 90

December 14, 2012

#554 – Past Plays

dramatizing the return of the repressed: moment @ steep theatre, 10/18/12 & good people @ steppenwolf theatre, 11/8/12.

History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake. — James Joyce, Ulysses

Both Moment, presented by the Steep Theatre, and Good People, at Steppenwolf Theatre, tell stories of Irish families (Irish American in Good People‘s case) struggling with the aftermath of some kind of traumatic event. In the case of Moment, the story turns on the reunion with his estranged family of a prodigal son who committed a heinous crime. In Good People, teenage lovers from a working-class Irish-American community in Boston are reunited after one made it out of the old neighborhood and the other did not, but the memories of old pains return with a fury.

Is there something particularly relevant about the shared Irish cultural heritages of the plays in terms of the haunting role of the past in the present affairs that take place on stage? Perhaps. But more fascinating than that, to me, was the whole dramatic narrative device of the return of the repressed. Events that do not take place on the stage, that took place years prior to the plays’ temporal settings, come roaring out to shape the stories.

Cynthia Marker and Grace Melon in Moment. Photograph: Lee Miller.

Very early on in both plays, these past events loom, unspoken, or perhaps in whispers and weird pauses. They are taboo ghosts that hover in the wings. Then they slowly start to gather energy, building up as the plays unfold. They begin to take on mass and weight, to crowd out the actors and the very plot taking place on the stage. Then, at last, bursting at the seams, they explode, shattering everything around them, leaving the characters to pick up the shards.

Neither of the two plays would exist or could function dramatically without these prior events, which become secrets that cannot help but secrete themselves into the dramas. They are preceding traumas that cannot be blotted out from the proceedings. Having already occurred, they emerge anew, essential to the progress, to the very plot, of the plays themselves. Out of sequence, they create order with their disorder. The momentous “moment” in Moment turns out to have happened already before this wisp of a play even starts; it should more accurately be called Aftermath of the Moment. To make good in Good People turns out to hinge on having gotten away with being bad; its title, after one has seen the performance, is deeply ironic too since it uses the return of the repressed to probe what defines the good in people who do well in the world as compared to those who struggle to make ends meet.

Keith Kupferer and ensemble members Alana Arenas and Mariann Mayberry. Photograph: Michael Brosilow.

The futures in both these plays depend on their pasts, on what happened before they started. As the terrible memories in each production come into focus, they eventually reorganize the meaning of the dramas taking place, as if one suddenly placed a lens, cracked and shattered, over an eye that had simply grown too tired of looking away from the truths of past scars. The old wounds, never quite healed, are ripped open again for the characters and the audience to see afresh.

This is not, of course, the first time plays have exploited the return of the repressed for dramatic ends, but Moment and Good People are reminders that the time spent in the theater is always shaped by the time before it, that when a world opens on a stage, another world opens up in the time before that stage and its play appeared. There are worlds within those worlds, one alway shaped by the one that came before it. But then again, as we know, when it comes to the world being a stage, what’s past is prologue.

#553 – Thinking Through Dancing, Lavishly

same planet different world 15th anniversary @ victory gardens biograph theater, 3/18/12.

Adam Guazza and Liz Jenkins of Sam Planet Different World dance company.

Dance that deconstructs itself always runs the risk of being too meta, too linguistic, too brainy. But this was not the case with Same Planet Different World‘s take last spring on Peter Carpenter’s Rituals of Abundance for Lean Times #5: Lavish Possession (2012). The spoken commentary on the dance was essential to the gestural language itself. The dancers explored in words and movement how the space opened up for creating art can sometimes afford its makers momentary distance from the sufferings of the world. But in creating this distance, it also makes them far more aware of that suffering.

Inquiring into the privilege of having the time to rehearse, explore, create, the dancers noted their awareness of being more fully in control of their bodies—and their thoughts about their bodies. Carpenter and the dancers treated this as a luxury on the surface, but the undercurrent of the piece was that while this experience of abundance, a kind of intellectual and spiritual abundance as well as an awareness of corporeal autonomy and control, at first felt like a privilege, it might prove in the end to be a right universally desired and deserved. When it came to controlling one’s own body, the questioning of lavish possession gave way to an insistence to it.

The dancers spoke and moved in paradoxes: they developed a “lavish phrase” that was in fact rather simple; they announced “this won’t happen again,” then repeated a gesture, they mused over their newfound abundance, but connected it to the degradations of others. The body of one person was connected to another: someone walking was matched by someone crawling; someone leaping was matched by someone stumbling; someone free to self-reflection was met by a silent other.

The freedom to contradict oneself in these ways was a sign of liberty, of claiming rights rather than receiving them as gifts, or better said of mapping out a new relationship between claims and gifts, demands and wondrous receipts.

It was also a recognition of the sin and suffering that sustains luxurious possibilities. The performance was not an expression of decadence so much as a critical inquiry into the bounty of expressive possibilities when one thinks through dancing.

Bookended by a first dance, The Drift League, that was balletic, quick, buglike, formalistic, icy, and abstract and the final two pieces, After Many Years and IT is What it IS, which were narrative, gooey, burlesque, smoky, hazy, sexual, wet, Rituals of Abundance for Lean Times #5: Lavish Possession was at once contemplative and sensual, meta and in the moment, bodily and mindful—it was an absorbing profusion of streamlined, eloquent awareness.

*A shout out to Time Out Chicago dance critic Zachary Wittenburg, who was on much the same interpretive wavelength about this performance.

December 12, 2012

#552 – Good Morning, Vietnam!

another fine radio documentary about rock and other music during the vietnam war era.

Album cover for Saigon Rock and Soul (Sublime Frequencies).

My acquaintance Sheila Pham has created a fascinating radio documentary about music during and after the Vietnam War era. The mix of personal exploration, multiple voices, memory, reflection, and sounds both old and new is marvelous and moving.

Listen and/or download here: Saigon’s Wartime Beat.

December 10, 2012

#551 – In the Shadow of the Sun (Ra)

artist cauleen smith grapples with the legacy of afro-futurism through her encounters with sun ra’s archives & the streets of chicago.

Cauleen Smith, Nicolai and Regina Series 01 (film still), 2012 16mm – digital print. Cinematography: Cauleen Smith and Ian Curry.

__________________________________________

Right now I urgently have to start preparing to go to Chicago to do this film about . . . it’s not about Sun Ra. It’s more about the psychogeography of Chicago as it relates to American music, about improvisational music, about radicality in Chicago’s working classes, and about how Sun Ra was able to tap into that in the process of becoming Sun Ra. It’s also about contemporary Chicago musicians and artists who are still very much coming from what I think is a black working-class wellspring unique to Chicago. They’re called creative musicians, not jazz musicians. As a group they create sound compositions using collaborative improvisational strategies. It’s not like a traditional setup where each musician takes turns improvising. These multi-instrumental musicians, who even build their own instruments, create the composition together—in real time. It’s mind-boggling. Originally, I wanted to get music lessons from them. I wanted my camera to become an improvisational instrument. — Cauleen Smith, quoted in Leslie Hewitt, ”Cauleen Smith,” Bomb 116 (Summer 2011)

For me afro-futurism centralizes formal considerations, structural considerations, and the stakes are in the praxis as much as in the language–if not more so. One of those practices, I believe, is most definitely the mastery of improvisation. …The formal concerns are where the stakes are because of the fierce rigor required to create alternative forms, alternative structures. It’s not that hard to name a record album after Sputnik, or a planet. It is more difficult (and to me more interesting) to generate several volumes of text devoted to deconstructing language, speculating about the past as it relates to the future, and living by the very forms proposed in your work and poetry as Sun Ra did and as Harriet Tubman did. — Cauleen Smith, quoted in Nettrice Gaskins, “Cauleen Smith: A Star is a Seed, A Seed is a Star,” art:21 blog

__________________________________________

Artist Cauleen Smith‘s great feat in her work inspired by the musician, composer, bandleader, and mystic Sun Ra is to enter into the composer and band leader’s esoteric, self-contained world without getting utterly absorbed into it.

Most scholars, artists, and fans who are drawn to Sun Ra get completely caught up in his universe. Rightfully so, since his self-created system of knowledge is so exhilarating in its sonic creativity, so seemingly complete in its self-contained sense of order and referentiality, so different from the usual way of doing and hearing and being, even when it comes to the rest of jazz. Those who get interested in Sun Ra want to understand this genius on his own terms, to unlock the secret code of his worldview, to grasp the complete song of his autodidactic arrangements of information and belief.

But Smith, while deeply curious about delving into Sun Ra’s many ideas, foregrounds her own concerns. Her engagement with him serves as but the starting point for her own art. Her work, on view at ThreeWalls Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago during the past year or so, is not about getting lost in Sun Ra’s world, but rather drawing upon archives of his work to make her own.

In this sense Smith’s work is part of a broader interest among recent artists in the concept of the archive, in esoterica, in examples of so-called “outsider art,” and in traces of systematized memory. But aside from those, what Smith most takes from Sun Ra is his tactic of reconfiguring conventional symbols, sounds, landscapes, monuments, metaphors, and forms into a kind of secret language. This rearranging of the dominant into another register taps into the longer traditions of signifying and double consciousness that Smith points out are found in the richness of African-American culture, forged as it was out of the need to survive and even thrive in extraordinary difficult circumstances. Smith’s own genius is to draw out for her own uses Sun Ra’s position within this larger practice and theory of how to survive and thrive.

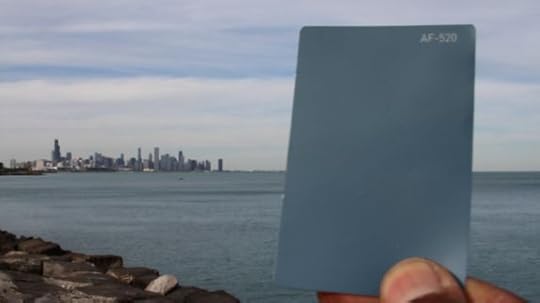

Cauleen Smith, Lake Interiors: AF-520 (HD still), 2012, Digital print, Cinematography: Cauleen Smith.

Most especially, her digital video works offer a kind of secret cityscape of Chicago within the existing city, a transfigured world of spiritual and political possibility that springs to life from what’s available rather than outright accepting or rejecting what’s already there. The gaze of her camera is transformative in a sharply sly way. Her art is Ellisonian with a twist, a sort of invisible woman approach to the city as cultural and political space of play, work, sound, image, struggle, anxiety, pointed critique, and pleasure. It is very moving.

Smith’s MCA exhibition took the viewer from an outer room in which multiple versions of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” were playing, including one by Sun Ra, through a dreamlike, space-age maze of mirrors, statues, and mysterious monuments, and finally into a video room where her digital videos screened. Entering into this pyramid-like tomb seemed, at first, like a journey into Sun Ra’s world, but the videos quickly took one back out into the Chicago landscape that Herman Blount, soon to become Sun Ra, occupied during his formative years as a musician and thinker, and which Smith made her own during a set of visiting artist residencies in the Windy City.

The videos featured musicians from the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians), the long-running institution for jazz and improvisational music in Chicago, performing around the city. Most provocative of all was a video of Kelan Phil Cohran, who performed with Sun Ra, playing under, in, and around Cloud Gate, better known as the Bean, the sculpture in Millennium Park by Anish Kapoor. Cohran pulled the weirdness of Cloud Gate out from its iconographic power as a symbol of the sleek, integrated global touristic sense of the city that governmental elites wish it to become. Suddenly, the Bean became a spaceship, a weird vessel of other Chicagos reflected on its silver surfaces, other sound waves enveloping it in a different cultural formation. Cloud Gate seems poised to blast off, no longer a tourist destination but rather some kind of boundary crosser into worlds hidden right there in the contorted everyday reflections across its exterior. Space was the place, indeed, as Sun Ra’s Arkestra famously sang, but it was also right there where we never even noticed it.

In other videos, Smith held up paint sample cards with various names against Lake Michigan. “Ode to Blue” was the most clever one, with its reference to the musical notes that accompanied the video footage. Here again, Smith’s work emphasized the making of a world that played off existing materials to take them in new and unlikely directions and colorations. The lake, so elemental and natural, so oddly grounding in its watery presence, bumped up against the mass-produced color—Smith’s art took place in the space opened up by the contrast between the two. An ode to the fascinating interplay between the Ode to Blue and the thing itself of light and water slapping up against the rocks just in front of her camera.

Most moving of all the videos were three that came across as little short stories, novellas of an African-American woman’s Sun Ra-inspired encounter with the cityscape of Chicago.

The first, Sonata for the Guardian of the Blackstone, portrayed the impressionistic adventures of a group of masked and caped children riding their bikes along the Lake Michigan waterfront. One looping segment featured an African-American girl spinning along a low wall by a pathway, her head connecting the dots of lamps poised atop lamp posts.

Another video, Nicolai & Regina, featured two African-American women in red, Run, Lola, Run wigs as they ran around various streets and monuments in Chicago. Were they running from something or just exploring the city for the joy of movement? It was ambiguous. They appeared at first outside the window of a silent-movie style therapy session in a wood-paneled home, dreamlike visions of an alternative life form, aliens arrived to offer access to new ways of understanding the everyday city around them.

Their most amazing encounter was with the “Golden Lady” Statue of the Republic that now stands at the center of a traffic circle in Jackson Park. This Statue of Liberty-like symbol of American values of freedom, liberty, and equality once, in its original incarnation, stood in front of the White City at the Columbian Exposition of 1893. But it took on all sorts of new meanings in the context of Sun Ra’s music on the soundtrack and the presence of these two African-American women, played by Rachel Russell and Brittany Brown, running up to, around, and in the shadow of the monument. The video summoned forth a sense of sourness and hope all at once, another kind of blues note on the shortcomings of American ideals of liberty and freedom, but also a recovery and recasting of those ideals. The video at once rejected the statue’s symbolic claims to stand for these ideals and reclaimed them for the purposes of Smith and her two characters.

A piece of notebook paper suddenly appeared before the camera in the video, graffitied with a quotation from Sun Ra: “You are all instruments. Everyone is supposed to be playing their part.” One can interpret this quotation in many ways, but one would be to think of Smith’s camera as her instrument, playing its own part by recasting the world it takes in, transforms, and registers as containing multiple frequencies. To be an instrument in the Sun Ra sense here is, in Smith’s video world, to find a way to play off the built environment in which one finds oneself. Recast by sound and alternative systems of autodidactic meaning-making, the city’s material realities break open with symbolic and emotional rewritings, reinscriptions, reworkings. There are cities within cities within the city, dreamscapes made real, realscapes made dream, all quite literally overlaid (or underlaid might be the better word) into its grid.

The final video, Space is the Place, offered the most powerful example yet of this transmogrification of the city by music and Sun Ra-inspired symbolic reformulation. It featured the Rich South High School Marching Band performing as The Solar Flare Arkestral Marching Band in a flashmob that suddenly manifested itself in a Chinatown square. The drums thundered, uniforms and hats and tassels and flags shone in glorious colors, musicians chanted Sun Ra’s lyric, “space is the place.” Smith’s camera caught Chinese characters written on the walls, the rain coming down around the band as they suddenly appeared, the onlookers who were unsure at first what was occurring then listened intently to the sonic and visual transformation of an everyday space into something else. It was a space that did not exist, yet seemed to have always been there in the first instance, immanent, just waiting to make its presence known to the eyes and ears that could see and hear it. Once musically and visually caught on film, it seemed as permanent, as material, as real—no realer—than the cement and buildings, which themselves took on a phantasmagoric, dreamy, slightly misty and mystical quality. Maybe it was the song’s beat and melody bouncing off them.

Then the band scattered and there was silence but for the storm clearing, the light and shadow, the people and their umbrellas, the sun just about to peer out from the clouds.

SOLAR FLARE ARKESTRAL MARCHING BAND #1 from Cauleen Smith on Vimeo.

#550 – Informal Archives of the Dead

comments on elisabeth lach-quinn’s comments on nick paumgarten’s comments on the grateful dead’s live concert archive’s comments on history. feel free to add comments.

Reposted from comments section of Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, “Dead but Not Forgotten,” US Intellectual History: The Blog of the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH), http://us-intellectual-history.blogspot.com/2012/12/dead-but-not-forgotten.html

Paumgarten’s portrait fuels meditations on the very activities that define us–as both creatures and creators of the past, whether through our collecting, connoisseurship, research, scholarship, or mere inhabiting or enduring of moments, whether of the original-feeling kind or those seemingly once, twice, or thrice removed but perhaps in fact just as originating–in their own story.

— Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, “Dead but Not Forgotten”

What marvelous reflections here. Thanks. I take the main theme to be the meaning and power of creating what might be called informal archives—constellations of artifacts assembled outside official channels, constellations that continually regenerate memories and meanings in endlessly reshaped reconfigurations.

Paumgarten reaches to express something like this theme, and in a way he demonstrates it in the loving details of his and others’ obsessive listening habits, which even they themselves are somewhat sheepish and embarrassed about admitting. But he does not quite get there at the theoretical level. Well it is a New Yorker piece, not something for History and Theory, so we should give him a break.

But I take your point to be that in the obsession by Paumgarten and others with the archive of live Grateful Dead recordings there is not an aim for fidelity in the empirical sense but rather in the emotional sense. And shifting to that register of fidelity entails raising extremely important and difficult questions about what history is exactly, how we determine it, and what it means to draw upon sources to make it. What does it mean to study moments when people were trying to live in the now, as it were. How does living in the now always involve an effort to live in (with?) the past? How do archives enable this strange pursuit?

Grateful Dead with American flag, late 60s. Credit: Grateful Dead Online Archive.

Grateful Dead with American flag, late 60s. Credit: Grateful Dead Online Archive.

My question is this: is there something particularly “sixties-ish” about this story? In that the Grateful Dead’s musical ethos features a kind of twin movement toward blasting memory away and, at the same time, preserving it? They wanted to “live in the moment, man,” but, in doing so, in the band and their audience’s shared goal of reaching states of pure improvisational collective musical creation, they also wanted to “make history,” which is to say they dreamed of imprinting the suffused authenticity of the immediate moment on their minds and bodies forever and even, perhaps, of using the energy of that shared effort to alter the future and possibly change the world around them for the better.

That dream was so awfully subverted, or at least obscured, by the aimless, decadent, upper-class hedonism that became the element of the band and the Deadheads by the late 1970s (and maybe was already there in that the band arose within the Cold War suburban defense industry technoworld of Palo Alto/Stanford in the mid-60s). Which is why Paumgarten turns to describing what at many levels was the tragicomic failure of the Dead milieu when it came to social change. Yet always lurking in the music, even through the 80s and 90s, was this spirit—magical, phantasmagorical, probably deluded—of somehow seizing history by its sensorial horns through musical communion, of losing oneself to the moment in order to pull away from it to some greater transformation. That’s religious in its roots, but also profoundly modern, even postmodern, in that it partly included the feeling of joining, of making, of being, of becoming part of a living archive comprised, paradoxically, of fleeting moments and psychedelically-infused flashes of powerful feeling.

Did something about the pressures and possibilities of the 60s moment create this kind of historical sensibility? Pardon the awkwardness of the term, but is this mode of historical consciousness itself historicizable? Perhaps it explains the oft-repeated reflection among participants in the more tumultuous events of the 1960s that they felt as if history had suddenly come alive, unhinged, that they were “living in history,” that history was suddenly swirling all around them, that they were even “making history.” The period in which the Dead forged their musical style was shaped by a strange mix of dreamlike surreality and the feeling of lifting the veil off a kind of canned experience. The war, the fraying of Cold War consensus, the radical energies that the nuclear age unleashed, the continued struggles among many for equality before the law and beyond it, these rendered a particular vision of history, of what counted as part of its archive of the past, and how this archive and its history might be made and unmade and remade again. The Dead’s music always, even as it changed into something far more formulaic, a brokedown palace of sound, retained the stamp of its origins in that 60s moment.

So what then does it mean exactly, this living sonic (and if you go on youtube visual) archive of the dead, this historical monument to a thing that sought, at its essence, to breakthrough from history and yet also seemed, from the get-go, to have an eye on itself from a perspective of the beyond, of historical legacy itself (they were the Grateful Dead after all)?

There’s certainly a lot of pointless philosophical noodling to do here, as befits the music and its stoned vibes I suppose, but the topic also raises up to consciousness the very deep levels at which history emerges, levels at which aimless noodling suddenly becomes a psycho-social spaghetti of tingling nerve endings.

Finally, isn’t it funny—and is it important—that so many of the key “texts” of this masculinist world of archival and Talmudic Grateful Dead study were created and compiled by a woman? And that this woman, Betty Cantor-Jackson, was among the first to perceive the historical consciousness in play through what she experienced as the beauty of the Grateful Dead’s concert experience. It certainly makes one think about gender in all of this collective history and memory stuff.

Listen to how Cantor-Jackson talks about these matters so eloquently and provocatively to Paumgarten:

She mixed to her own taste. ‘It has my tonalities. My sound is beefy. My recordings are very stereo, very open, with a lot of air in them. You feel like you’re standing in the middle of the music. My feeling is everyone wants to play in the band.’

The goal here is at once to make an archive of the self (“my tonalities” “my sound”) and create a space of collective sharing (“very open, with a lot of air in them” “you’re standing in the middle of the music” “everyone wants to play in the band”). So not only does this music and social experience pivot on simultaneously exploding and preserving history, it also turns on the creation of a kind of subtle, barely discernible filter between the individual and the collective.

How do I, how do we all, fit in, both temporally and spatially? That seems to be the motivational calling card for those drawn to the Dead’s informal archive. It is the continual cataloging and recataloging of possible answers to this question that makes it significant.