Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 86

September 3, 2013

New Books Network Podcast Interview

I had a great time talking at length with Ray Haberski about The Republic of Rock on The New Books in Intellectual History Podcast. You can hear our conversation here.

August 24, 2013

Cracking Art Codes

The imagery and narratives that constitute art discourses are rooted in deep social assumptions, which are things we don’t know. The coercive forces of society that act on our lives and impress our work are merely understood, like parts of nature. A meaningful order, or nomos, is imposed on the discrete experiences and meanings of individuals. Cracking art codes is not possible without undermining, or acknowledging, personal prejudice—the ’tissue of clichés’ [CR note: from Barthes] by which we habitually perceive the world, and selves in world.

— Jill Johnston, Secret Lives in Art

Jill Johnston. Photograph: Jack Manning/New York Times/File 1985.

Jill Johnston. Photograph: Jack Manning/New York Times/File 1985.

August 22, 2013

Hip Militarism in the Woodstock Transnational

part 3 of tim lacy on The Republic of Rock.

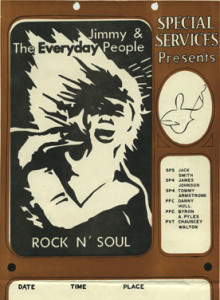

“Rock n’ Soul”: Jimmy & the Everyday People Poster, Command Military Touring Show, Republic of Vietnam, 1971.

“Rock n’ Soul”: Jimmy & the Everyday People Poster, Command Military Touring Show, Republic of Vietnam, 1971.

August 9, 2013

We’ve Got a (Historical) Situation

Triangles may be explicable without reference to historical situations. Concepts such as ‘civilization’ and Kultur are not. It may be that particular individuals formed them from the existing linguistic material of their group, or at least gave them new meaning. But they took root. They became established. Others picked them up in their new meaning and form, developing and polishing them in speech or writing. They were tossed back and forth until they became efficient instruments for expressing what people had jointly experienced and wanted to communicate. They became fashionable words, concepts current in the everyday speech of a particular society. This shows that they met not merely individual but shared needs for expression. The shared history has crystallized in them and resonates in them. Individuals find this crystallization already in their possibilities of use. They do not know very precisely why this meaning and this delimitation are bound up with the words, why exactly this nuance and that new possibility can be drawn from them. They make use of them because it seems to them a matter of course, because from childhood they learn to see the world through the lens of these concepts. The social process of their genesis may be long forgotten. One generation hands them on to another without being aware of the process as a whole, and the concepts live as long as this crystallization of past experiences and situations retains an existential value, a function in the actual being of society—that is, as long as succeeding generations can hear their own experiences in the meaning of the words. The terms gradually die when the functions and experiences in the actual life of society cease to be bound up with them. At times, too, they only sleep, or sleep in certain respects, and acquire a new existential value from a new social situation. They are recalled then because something in the present state of society finds expression in the crystallization of the past embodied in the words.

August 7, 2013

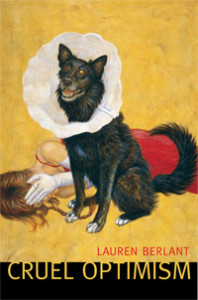

Crisis Ordinariness

Crisis is not exceptional to history or consciousness but a process embedded in the ordinary that unfolds in stories about navigating what’s overwhelming.

August 6, 2013

Talk: WordPress for the Humanities – Developing a Digital History Course 2.0

Presentation at the Arthur Vining Davis Digital Humanities Summer Faculty Workshop at Northwestern University, Monday, 5 August 2013:

Talk notes (please pardon any typos):

I want to start out briefly discussing the broader scope and significance of my research. Then I’ll turn to how I involve undergraduates and why I use WordPress to do so.

My current research focuses on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, which ran from 1958-1970 on the Cal campus. The Berkeley Festival preceded the more famous Newport Folk Festival and was a model for it since it mingled older and younger performers and rather than function as a spectacle of musical performance included workshops, talks, and more egalitarian, hands-on involvement by all attendees. It also, of course took place in a center of radical political and cultural activity—Berkeley and UC Berkeley in particular—so one central question is why has it largely been left out of the historical record. The digital may have something to offer in answering this question.

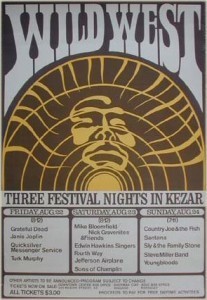

The Festival was run by one man: Barry Olivier. It featured a wide range of performers: Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Doc Watson, Mississippi John Hurt, Mance Lipscomb, Rev. Gary Davis, New Lost City Ramblers, Country Joe and the Fish, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Phil Ochs, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, Almeda Riddle, Bessie Jones, Alan Lomax, Charles Seeger, Archie Green, and many, many others, including Jesse Fuller, the one man band, who you just heard singing his famous San Francisco Bay Blues at the start of this presentation.

The archive of the BFMF, purchased by Northwestern’s Library in 1973, consists of over 30,000 plus objects. Business records, posters, letters, ephemera, audio, film, and especially rich trove of photographs.

In this study, I am interested in a number of issues:

What is the relationship b/t visuality and aurality? This is an archive dominated by photographs, yet it was first and foremost a sonic and musical event. How might one study it as a sonic and musical event through visual material?

The lostness of the sonic and musical qualities of this event has led me to ponder additional questions of what we might call ephemeral history, namely what exactly is an archive that documents event such as the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, whose most significant elements might well be its most ephemeral experiences?

How do we study ephemeral historical experience, particularly when it comes to temporary but very powerful aesthetic encounters?

This question has led me to think about the perceptual and phenomenological in historical study. Historians tend to privilege the semantic and epistemological—just go look at the documents and write about what they say one colleague once patronizingly (and naively I would say) told me. But this approach misses huge swathes of what matters historically, which is the very weirdness of historical archives, of documents themselves, what they contain, what they consist of, how the stuff got there, how it looks different depending on how you examine it. The question for me with the Berkeley event is that its importance is only half understood unless we think carefully about historical perception, phenomenology, sensation, experience.

All this has led me to consider what the digital might contribute to a study of ephemeral history, perception, sensation, and experience, particularly in relation to music and sound.

I can talk more about the details of my broader research agenda—it’s a many headed hyrdra that includes a digital archive, book, exhibition, and set of digital tools for studying vernacular music & culture. Particularly, I can talk more about the stakes of turning to the digital to study the past, but now…

Here is where undergraduates come in.

I teach an upper level history 395 research seminar, digitizing folk music history, in which students and I explore the intersection of contemporary digital platforms and the history of the folk revival.

It is a chance to deepen and expand my research agenda through teaching.

But it is also for the students. I think that as an historian I have an obligation to train my students for the contemporary world. And history is not antiquarian studies. It is about relating the past to the present.

So one of the working concepts for the course is that just as the digital can help us to better understand this historical phenomenon, so too this past episode in time—the folk revival (and one might say history in general) can help us get our bearings in the modern, wireless world.

The folk revival presaged many of the issues at stake in the digital: questions of democratic interaction between the individual and the collective; dilemmas of intellectual property rights and copyright; the relationship between cultural representations of race, gender, ethnicity, class, region and their political and economic ramifications; the interactions between tradition and modernity; the mediating presence of technology; and other issues.

So, in my course, which is as I said an upper level History 395 undergraduate history research seminar, I work with fifteen students to study the folk revival digitally and, simultaneously, to think about the digital age more historically.

To start with, I needed to dispel a current myth about today’s undergraduates. Some call them “digital natives,” a problematic term on multiple counts. But the connotations of native aside, it is true, in my experience, that today’s students exist effortlessly in a digital world of consumption. This is their indigenous culture. What is far less convincing is that they are able to function as critical analysts and able, autonomous producers of knowledge in this world dominated by the mediation of digital technologies. What I wanted to do in my course was to study the folk revival—and the Berkeley Festival in particular—in ways that helped my students think more critically and move more deftly through the digital milieu. WordPress became the best way to do this.

Remember, currently Northwestern, and especially Weinberg College, where the History Department is housed, has no curricula for the digital humanities or policy about how to incorporate the digital into the classroom. That’s fine. But it meant that my course would have no prerequisites in digital media skills (not to mention in musical training). Working with Josh Honn and Claire Stewart of the Center for Scholarly Communication and Digtal Curation at the NU Library, Harlan Wallach’s team in the NU A&RT division of NUIT, the librarians in Digital Collections, and Scott Krafft’s staff in the Special Collections library at Northwestern, we settled on WordPress as a good platform for the course.

Why? Begun as blogging software, WordPress has expanded into a lightweight content management system. It is fairly intuitive and easy to learn, it has a swift learning curve for newcomers and a robust user community for asking questions and seeking solutions to problems. But it also, if taught right, gives students a “peek under the digital hood” at how the digital works, particularly when it comes to using the basic building blocks for Internet websites such as databases, stylesheets, plugins, tools, right down to the core element of a hyperlink. We could examine the digital as a new medium for historical study without getting too bogged down in digital issues and losing our focus on our historical topic of the folk revival.

The user interface.

In the course, as we complete readings, watch documentary films, listen to audio mixes, and discuss our studies in a good, old-fashioned face-to-face seminar, my students also complete weekly mini-blog assignments, each using a different tool. These digital tool experiments culminate—as the History 395 course requirements stipulate— in a final project, here WordPress-based instead of on paper. It is based on original research and incorporates the tools with which they have experimented during the quarter, as well as new tools, thematic design layouts, and other digital techniques that might better develop and communicate each students’ analysis.

I call these final projects interpretive digital history projects to distinguish them from simple curations of digital content or the show-and-tell-type projects that to me seem to dominate the digital humanities landscape. The goal here is for students to pursue analysis, interpretation, an argument, grounded in evidence that has been deeply, robustly, meaningfully studied—processed we might say—digitally.

Here are a few examples of what students do in the course:

Annotation.

Table building.

Short writing that draws upon annotation and table building.

Interactivity through comments and followups.

Tagging and tag cloud folksonomy. Individual and collective.

All for getting students to more convincingly connect evidence description to interpretation.

The digital is employed here not to speed things up, the typical way we think of it, but rather to slow things down, to force students to do something that I’ve noticed increasingly missing from their writing, indeed from the thinking behind their writing: developing argument out of specific engagements with particular details. This isn’t about the trendy distant reading. It is about using the digital in service of developing better close reading.

But history happens in time.

So, in terms of time and chrinology, we do timeline building—good for students to begin to organize their readings and viewings into an overarching narrative. But also good for revealing the artificiality of any one neatly ordered chronology. the difficulty of constructing a timeline of the folk revival becomes productive here, the mutability of the timeline tool allows for a lot of playing around with order, configurations. Getting an overarching narrative in mind through creating one but also in the same digital exercise problematizing it.

History also happens in space. Geocoding. Maps. Thinking about data. (This could also one day come to include moving between the actual spaces of the festival and digital mappings of them.)

History is narrative. We use Wireframe cc to storyboard and experiment with design. Historical narrators of the future will need to think as much about visual, aural, multimedia design.

WordPress themes offer an opportunity to reformat the same content, to experiment with different modes of telling a story, mapping out its evidence, developing its historiographical and interpretative context, convincingly expressing a multimodal argument that uses not just text but also sound, imagery, and the multidimensional rhythms and flows of an Internet interface.

History is also constructed and historians can borrow from critical media theory to think more critically about the very materiality and strange mutability—the sheer weirdness—of our sources. Deformance. Not just close reading but compositional tactics in service of new aspects of our data: Stephen Ramsey’s “screwmeneutics” or the “hermeneutics of screwing around.”

This particularly history of the folk revival is also sonic, and given that it is folk music, especially focused on the reinterpretation of past sounds in new ways to speak to a contemporary perspective (in this way historical interpretation and folk music creation have a lot in common). So I have my students develop remixes of audio. History as remix assignment. I ask them to use simple sound editing software—Audacity—to create a remix and then respond to the following prompt: if my remix was a term paper, its argument would be…

Example: SBTRKT song, “Wildfire” mixed with Howlin Wolf Live at Berkeley 1968.

This student went on from Berkeley to our locale of Chicago. An amazing final project on Willie Dixon’s Blues Heaven Foundation in the context of the folk revival…completed and digitized oral history interviews with Dixon’s wife and son. A kind of public history and civic engagement in Chicago through the digital.

We have also had involvement both in person and virtual with participants at the Berkeley festival—Barry Olivier, the musician Alice Stuart, and others. WordPress a good platform for including participants from afar.

My WordPress website exists in a multisite structure, a potential distributed network model for creating a living archive, the archive as commons, a kind of ongoing, digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival. By archiving uses of the BFMF archive as new parts of the archive itself. Future historians can study what a college student in 2013 made of a college student in 1963 of the folk revival.

These are just a few of the possibilities that the WordPress platform allows. It’s not the only way to go. But I think it is a good starting point for teaching digital history, for helping students probe what it means to think critically both about and within the digital domain.

I’ll end here. Let’s talk more about what’s on your mind now.

Using Rock To Think—And Dream, Part 2

Tim Lacy continues his reading of The Republic of Rock over on the US Intellectual History Blog, with good sparks in the comments section thanks to Tom Van Dyke and Kahlil Chaar-Pérez:

Using Rock To Think—And Dream, Part 2.

July 23, 2013

Rebranding the Free Market

The task of today’s Left is not, then, to abolish property rights—as is so often supposed—but to invent or expand alternative property forms that recognize the ambiguity of ownership, especially in relation to intangible assets and organizations. The clear dichotomy of ‘public vs. private’ should be abandoned, and the gray area between the two explored.

—William Davies, “Freeing the Market,” The Point, Spring 2012

Copyrighting the Digital Stream

In the wake of Nigel Godrich and Thom Yorke’s removal of Radiohead albums from Spotify, Sasha Frere Jones of the New Yorker has a nice interview with Damon Krukowski (Galaxie 500, Damon and Naomi) concerning questions of digital copyright and the music industry: Sasha Frere Jones, “IF YOU CARE ABOUT MUSIC, SHOULD YOU DITCH SPOTIFY?,” 19 July 2013. Links to various other key articles—the Radiohead announcement, David Lowery of Cracker’s screed against fans downloading free music—in the piece.

I love these reflections on the history of recording, technology, copyright, intellectual property, and art from Krukowski:

I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that at the beginning of recording, the courts ruled that you couldn’t copyright a given performance of music because it was nothing more than vibrations in the air—and who can say they own the air? As I understand it, the history of record “labels,” “mechanical” royalties, album art, and all the rest began as an end run around that rather pataphysical ruling. Recording companies were looking to copyright all they could, since they couldn’t lay claim to the immaterial vibrations at the core of their products.

So here we are at the other end of that long century of cylinders, records, tapes, and discs, with more or less the same problem that started it all—because who can say they “own” a digital stream of information, any more than the air?

Spotify, Pandora, Apple, and the rest are doing what they can to make us believe they own that stream, just as recording companies did by copyrighting all the ancillary bits of albums. But they don’t. Just like the record companies at the beginning, they own only the means of delivery, not the music itself.

I think if we accept that basic truth—that no one can own the stream, any more than the air—then we can start from a more solid place to rebuild how and why we might compensate those involved in the production of recordings.

…But back to your question about the world ahead—I feel a bit like those Marxists when they are inevitably asked, O.K., but what happens after the state withers away? It certainly sounds like a dodge, but I sincerely think we won’t know till it happens. Or then again, maybe it has already happened, without our realizing—recordings are already essentially worthless in the marketplace—and it’s these heavily capitalized businesses like Apple, Spotify, and Pandora that are setting the agenda for the new order. I don’t think they have a claim over it, not in a moral and I am pretty sure not in a legal sense, either—but they are the ones loudly staking the claim. What I’m thinking is, What if we call their bluff? Maybe no one will end up being paid for recordings, in that case—but as it stands, musicians aren’t anyway.

Damon Krukowski and Naomi Yang.

Damon Krukowski and Naomi Yang.

July 21, 2013

The Surburbs

In the suburbs one bears a special onus to be happy.

— Michael Greenberg, “Sub Mission,” Bookforum, Feb/Mar 2012