Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 82

January 21, 2014

It Goes This Way and That Way

starting to historicize the folk revival in “digitizing folk music history” seminar.

We spent last week in Digitizing Folk Music History (see all posts on the course) beginning to move from our opening question—what is folk music, anyway?—to an initial description and interpretation of the folk revival and folk music using Ron Cohen’s Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival & American Society, 1940-1970 and the 2001 documentary film American Roots Music, directed by Jim Brown. Over the next few weeks we will be using seminar discussions and digital tools to grapple with the “macro” narrative of folk music and the folk revival in the US. We will also be considering the relationship of the big story to various micro and middle-level histories. (We’re using the digital as a way to think about scale, among other topics.)

To get into the material, students will annotate text documents we are reading (a 1963 article on the folk revival from Time magazine; Barry Olivier’s reflections on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival; and a 1993 Larry Kelp article on the musical “Berkeley Renaissance”) using the Crocodoc annotation tool, they will build tables (a key research tool and form—the database—that underlies so much multimedia publishing that can also be used to compile descriptive elements and begin to determine their significance on the way to an interpretation), and they will write short essays.

Then we’ll turn to timeline building using timeline.js in order to explore how historians construct temporal narratives at a macro-level, middle-level, and micro-level and how we might start to think about the benefits and shortcomings of a linear approach, as well as what other temporal representations might enhance our organizing of the US folk revival into a historicized set of occurrences, themes, people, places, forces. A few notes below from class. Next up: a few examples of student annotations, table building, and essay writing from this year’s seminar.

Notes from the board and class:

What are different ways of thinking about and tracking folk music? Mediation, circulation. Even though we think of folk music as the “root system” or the watershed whose streams feed contemporary music’s raging river (metaphors of Marty Stuart and Ricky Skaggs, beginning of American Roots Music), how might we describe (“annotate”) artifacts from the revival such as songs, reviews, posters, performances, recordings, business records, ephemera to make sense of how the revival existed (and continues to exist) as a cultural phenomena in motion? How is tradition paradoxically represented and re-represented over time?

We pursued a collective “close viewing” of the opening sequence in American Roots Music. What is going on here from the very start of the film? How, as images, sounds, “talking heads” edited together is it making its argument in form as well as content? How might we catch these and describe them (again, “annotate” them)? And then, building up from descriptions of those details, what is the documentary’s implicit (and sometimes quite explicit) argument exactly?

Talkin’ History Blues: folk revival consciousness asks us to think about how do we conceptualize historical time: linear, whether ascension/progress or declension/decline or circular or fragmented or pastiche or some other sense of temporality?

January 20, 2014

Digital Historiography & the Archives [5/5]

papers delivered at the 2014 AHA conference.

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

—

Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

mjk@northwestern.edu, twitter: @kramermj, www.michaeljkramer.net

I once joked to an archivist with whom I work that all I do as an academic historian is add meta-metadata. Metadata, the descriptive information that accompanies the artifacts in a fully-developed archive (and which also incidentally often accompanies certain categories of digital file types) places a layer of information, provenance, ordering, and hints of thematic significance upon each object in a collection. In the digital domain, metadata often becomes crucial for wielding large amounts of information—many thousands of documents—effectively or fruitfully. Archival description in the form of metadata is of course a key aspect of what professional archivists do. Historians often come into the archival picture after the metadata is in place, using it to survey archives in search of useful materials and then to probe these archival sources for their interpretive significance, their stakes for particular historical stories, themes, issues, and questions.

To call what historians do meta-metadata is to go meta, as it were, on the intersections between what professional archivists and historians do, and how they conceptualize their practices both separately and in league with each other (and sometimes in conflict with each other). It is, in short to practice what our panelists call, in the roundtable description, digital historiography. Which is to say it is a way of more critically connecting archival theory and professional archival practices to historical theory and professional historical practices. More of this term—historiography—and its significance in a moment. But first I wish to make a few brief comments about the short but sharp presentations by Josh Sternfeld, Katja Hering, and Kate Theimer.

It is my hope that these mini essays themselves eventually find their way into the archives, whether those be the storified live tweet archives of the session, the official AHA archives, or the vernacular archives of your minds (yes, Kate, I am going to use the term archives more metaphorically and adventurously here, and you are allowed to complain about this!). For these presentations are important contributions to the archive of how we are to understand digital technologies as we all—historians, archivists, students, professionals, citizens—increasingly dip our virtual toes in digital waters and sometimes find ourselves with the distinct feeling that we might soon be drowning.

Our round table today is particularly focused on three keywords: digital, historiography, and the archives. There are other keywords that crop up as well in Josh, Katja, and Kate’s comments: surface, context, provenance, metadata, scale, appraisal, calibration, evidence, criticism. But I want to hone in on the three words in our roundtable’s title as crucial ones before opening up the conversation to all of us.

The Digital

First, the digital. Josh Sternfeld’s wonderful suggestion is that we imagine a “quantum history” that moves beyond the scale of a sort of Newtonian historical middle ground in which evidence and convincing argument have largely stable properties and interact through mostly predictable and agreed-upon relationships. Going micro and macro have already become part of the historical repertoire, but I think Josh is correct to suggest that the digital affords new opportunities to revisit those strategies of analysis and think about how we might toggle, if you will, among them as we, as he puts it “calibrate” our narratives in new ways. One way to do this is for historians to think more critically about the provenance of our sources, a term to which Katja draws our attention. Rather than treat evidence as transparent access to the truth, we might consider the how’s and why’s of the origins of our “evidence” from their starting point right through to the generations of archival creators, maintainers, and interpreters. We should also remember that the archival objects are often surrogates (a wonderful term that Kate invokes) of a sort for what actually happened in the past. The bedrock of historical interpretation, these archival sources are themselves but representations, and usually partial or distorted ones at that.

So we will need to consider their provenance into the very moments, structures, forces, and people whom they represent and who did the original representing. Historians and archivists alike have been doing this for many years, of course, and traditions of historical and archival thinking and methodology have as much to bring to the new digital domains as digital technologies do to these respective fields. One also thinks of how digital history’s “quantum” turn, as Josh Sternfeld asks us to imagine it, offers an opportunity to revisit the notion of the long durée and the macro-historical Braudelian ideas of the Annales School. Similarly, digital technologies might allow us to rethink the concepts of “microhistory” as we might fix our attention on the “dark matter” of cultural minutae as they register in the world of data, networks, and digital infrastructures. Katja’s notion of source criticism, drawn from her reading of the nineteenth-century work of Johann Gustav Droyseen, bespeaks the productive effort to draw upon past ideas to grapple with current digital challenges and opportunities. So too does Kate’s insistence that we use the word archives with care and precision—and perhaps not use it sometimes.

Archives

Ah, now to that loaded word: archives. Why the popularity of this term? Why also the pressure on this word now? This pressure comes not merely from the new representational and methodological qualities of digital technologies; it also comes from a longer running inquiry into the power of representation, particularly of the state’s uses of official recordkeeping to wield power, secure legitimacy, obscure facts, and govern its citizens and so too those deemed non-citizens by tracking them as individuals or transforming them into abstract demographic statistics. This longer running inquiry into the power of the archives, their ability to wield knowledge in service of hierarchy and control, tilts me more toward using the digital to open up what we call an archive rather than limit it (yes Kate, I know I’m throwing down the gauntlet). In an era when large, “official” digital archives are being used to data mine human individuals on social media websites and erode privacy through government spying, we need to consider other kinds of imaginings of the archive that are not as totalizing, that are more quirky and messy and unofficial. The digital seems to make these possible too, if we let it. However, how we develop and use these kinds of archives within the urge for standardization in the digital arena becomes a great challenge.

Historiography

Historiography, the last term from our roundtable’s title, offers a key starting point for archivists and historians alike, I think, in trying to broaden what the archive might be and do in the digital domain in relation to history. There are some real differences here professionally between archivists and historians that we need to consider. After all, what archivists, as I understand their training, are taught to call objects, artifacts, documents, items historians, by contrast, refer to (sometimes with far too much unquestioned essentialism and with an air of exploitative plundering) as sources. For archivists, the goal is to preserve, describe, and provide access to archives for a broad range of users, from professional historians to private archive owners to the public at large. For historians, the goal is not only preservation or multifaceted access, though it can be those things; it is most of all to mine archival material for interpretation. These two approaches—archivist’s and historian’s—can go together, of course, but they only do so through slightly different imaginings of the stuff itself in the archives and the uses to which it should be put.

On this count, I think, historiography provides a way to grapple with the connections and divergences between archivist and historian. While there is a digital historiography that modulates between different levels of digital scale and appraisal, text and context, source preservation and source criticism, as our panelists have all pointed out, there is also a more traditional use of the term that can be brought to bear on our conversation. That is the way in which historians have used the word historiography to refer to what we might call the history of history itself, which is to say the history of historical interpretations of the past. If methodology, something that the three presentations are all concerned with, is a way to approach primary sources in archives, then historiography has usually been about secondary sources in the field of history itself.

But what, I wonder, would it mean to address this understanding of historiography within the digital domain? It would mean, perhaps, rethinking the relationship between primary and secondary sources in new ways, not just going to the supposedly pure sources, fetishized as they are in the field of history. It would also mean contextualizing them within ongoing conversations among historians both past and present, and taking a stand within these ongoing conversations.

In shifting from thinking about digital history to digital historiography, then, there is a different kind of provenance at work too, much as there is in archival work and theory. This is a historiographical sequence not of object ownership, but rather of interpretive ownership. It is far more contested kind of ownership of course, in a good way. It forces us to ask questions such as: which historians have looked at these archival things before? What sources have been ignored and why? What did historians have to say about archival sources and why? How did they temporalize them, contextualize them, conjoin them, or distort them? What methods and preoccupations, interests and worldviews, shaped their interpretations? These questions are meant to suggest that within a historiographic context, within thinking about the history of historical interpretation, we need to grapple with continuities between and among generations of historians and also, of course, debates. We also need to think carefully about voices left out of these conversations and the kinds of questions and themes that drive them as well as the well known established voices. We need to confront the whole assemblage of the history of history, which is grounded not only in readings of primary sources in archives, but also readings of secondary sources outside the archives.

Or better, yet, we might think of various historiographies themselves as archives. They may not be encased in walls or stacked in boxes on shelves, but they are sure enough constellations of materials brought together with a provenance secured and documented in literature reviews, encyclopedia entries, the background sections of articles and books, and in footnotes and endnotes. If primary sources exist as one kind of archive requiring more careful attention to methods of access and analysis, secondary sources are also an archive of sorts, brought together through interpretive practices, characterizations, and interventions in the field of history itself. What a digital archive might do is provide a space for bringing these two kinds of archives into play with each other. It can articulate them to one another. A digital architecture for a new imagining of the archive might be able to provide more dynamic linkages and movements among, on the one hand, materials being used as primary sources—put to service to represent the past as best as it can be factually reconstructed—and, on the other, materials being used more primarily as secondary sources.

A new kind of useful fluidity might emerge among linked open-source archives and scholarship using the materials in those archives. The digital archive, with an expanded notion of what it does, has the opportunity for enriching history by more dynamically linking primary sources and their subsequent interpretations, and in doing so, of raising the question of what a source is exactly, and how we appraise, to use Josh’s term, the relationship of evidence to argument, sources to interpretations and ongoing conversations. Within new kinds of digitized settings, historiography can flourish as a key part of archives themselves and the historical narratives of the past they inspire.

In this sense, maybe history is just meta-metadata. Maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

—

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

Digital Historiography & the Archives [4/5]

papers delivered at the 2014 AHA conference.

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 4: Kate Theimer, “A Distinction worth Exploring: ‘Archives’ and ‘Digital Historical Representations’”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

—

Kate Theimer, “A Distinction worth Exploring: ‘Archives’ and ‘Digital Historical Representations’”

kate.theimer@gmail.com, twitter: @archivesnext, www.archivesnext.com

As noted in the text, I had read drafts of Josh and Katja’s remarks before writing mine, which was very helpful in deciding what aspect of my perspective as an archivist I should focus on. I spoke without slides, and this is an only slightly modified version of the text from which I spoke. I’ve added links to the sites I reference and other sources that might be useful.

In approaching this session and this topic, I had trepidations, as I often do, about how the other speakers and the audience would be framing their conception of “archives.” In preparing my talk I read an article Josh had written for an archival journal in 2011 [“Archival Theory and Digital Historiography: Selection, Search, and Metadata as Archival Processes for Assessing Historical Contextualization,” American Archivist Fall/Winter 2011] and was pleased to see his careful usage of the phrase “digital historical representations” as an umbrella term covering some of the products created by archives, as well as a range of products created by other sources.

In approaching the subject of archives with historians and other humanities scholars, I often feel somewhat pedantic in my continual emphasis on the meaning of words. But after all, words represent concepts and perceptions of reality, and if those words aren’t clearly communicating what we intend, then it’s hard to achieve meaningful progress. What I’d like to talk about in the time I have, and hopefully as part of the discussion, is to illustrate the points Josh and Katja have made about the importance of questioning, understanding, and articulating the context of creation of digital historical representations by discussing the differences between different types of digital information sources created and used by historians—many if not most of which are often all referred to as “archives.” In all of these cases the context of the creation of the information sources is critical to understanding the problems that may be inherent in that source and which the researcher should take into consideration. I am not a historian, but I would think that understanding why and how an information resource was created—that is to say, its context—is more valid than ever in digital historiography.

Everyone here is familiar with what for lack of a better term I’ll call “traditional” archives—that is, primarily paper-based (or non-digital) largely unique materials, brought together in repositories in aggregations either created by the originating organization or person, or by a third party, such as a scholar, manuscript dealer, or the repository itself (as in special collections). Appraisal and selection of such materials is a multi-dimensional process, as you might imagine, with many factors involved, including sometimes political influence, censorship on the part of the creator/collector, resource limitations on the part of the repository, random chance and “acts of God.” How and why the materials on our shelves end up there is not always a straightforward story and one that is usually not captured in detail in the public description of the materials. How the materials were aggregated and for what purpose is usually described at some level in the finding aid, but documentation in this area is sometimes sporadic. I would guess most archivists believe—rightly or wrongly—that fields like “Custodial History,” “Appraisal, Destruction and Scheduling Information,” and “Administrative/Biographical History” (which applies to creators of aggregates) are not valued by most users. To be honest, I’m not sure how often it’s even of interest to historians, or at least how often they ask the archivist about more information if the finding aid is skimpy in this regard. Anecdotal evidence from my colleagues and user studies indicate that it is not widely valued or used by users.

Again, that’s “traditional” physical archival materials, represented digitally by descriptions in online finding aids, catalog records, etc. For these materials, what has changed for historians in the modern digital age, I think is the increased expectation—and reality—that more descriptive information about materials will be made available online, and also the ability to easily create their own digital copies with digital cameras and smart phones.

Next we have collections of digitized analog historical materials—sometimes called “digital archives.” These may be topically based—assembled from holdings of many repositories, like the William Blake Archive or the Wilson Center Digital Archive, which is focused on documents related to international relations. Or they may be all from one repository—as in the recently launched FRANKLIN site, which provides online access to digitized collections from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. These collections may be created by archivists, librarians, historians, passionate amateurs, nonprofit organizations or for-profit companies. Because these digital historical representations, to use Josh’s term, are created by such a wide range of sources, it’s critical to know about the context of these collections—including who assembled them, what their purpose was, and what criteria they used.

Often when historians are talking about archives, when I probe to see what they mean, it is these kinds of collections they are referring to. Katja’s point that it’s important to know where the individual original materials are located and where they fit in their archival context is a valid one, but it’s also important to understand where they fit in the context of the new digital collection. On what basis were items added to this collection? Why were some items excluded? To what extent is what’s being presented a subset of what’s available? Where does the metadata come from? How was it created and reviewed? As with online finding aids for physical collections, what you’re accessing in this kind of digital collection is a surrogate—a description of that object or aggregate created by a person to represent it. Even the scan is a surrogate—although hopefully an accurate one. Descriptions and metadata can be subjective and also subject to errors.

It seems to me as if these kinds of collection—or “digital archives” as they’re commonly called, would raise a host of questions in terms of digital historiography—some similar to those presented by online information for “traditional” archives, but many others that are different.

Yet a different kind of aggregate, also sometimes called “digital archives” are groups of born-digital materials as opposed to the digital surrogates of analog originals I just talked about. These types of aggregates, kept together because they come from a single source or creator, reside primarily within archives and special collections repositories, and consist of records created or received by an organization in the course of business, maintained by them and transferred to their associated archival repository. For example, the electronic records created by the Census Bureau and transferred to the National Archives. You can also have the equivalent of the “papers” of a person or family, such as Salman Rushdie collection at Emory, which contains the contents of his personal computers. For these kinds of aggregates archives have most of the same kinds of issues with selection, appraisal, and custodial history as they do with non-digital materials, but with additional issues raised by their digital format, as Katja noted, related to reliability and authenticity as well as how to provide access.

And last but not least, you can have assembled collections of born-digital materials—yet another category of what are termed “digital archives.” The September 11 Digital Archive created by the Center for History and New Media is a good example of this type of collection. In this case—and also with the Internet Archive—the collection serves a critical function: acquiring born-digital materials that might not otherwise survive. Many born-digital materials are more fragile than their analog counterparts for various reasons, and so some of these collections are similar in function to special collections libraries, which pull together valuable individual items for preservation. It’s also worth noting that in digital collections, copies of materials can reside in more than one collection. For example, in the September 11 collection there are copies of documents created by the New York City Fire Department (Incident Action Plans). Presumably there are also copies of these born-digital records being transferred to the official repository for the municipal records of New York City. These kinds of “digital archives” combine the issues related to assembled collections—that is, the necessity of exploring who is creating them, for what purpose and using what methods— and those concerns related to born-digital materials as far as preservation and authenticity.

Coming back to Josh’s use of the term “digital historical representations,” I’m happy to see this broader term being used in discussions about “archives” and digital historiography. For me, many products that come under this term—like databases and sources like Google Books—would be removed one step (or more than one step) too far to be categorized as “archives.” I would consider these as separate intellectual products created from archival sources. And, indeed, in a way, so are any of the collections in which copies of archival materials are removed from their original context and “re-mixed” to be part of a new creation—a new “digital archives” like Valley of the Shadow, to use a classic example. In fact, in a pre-digital era analogous versions of the scholarly products I’ve talked about here (other than databases) would still have existed, I think, and been called something other than “archives”—they would have taken the form of exhibits, edited volumes of letters or printed collections of documents, assembled and edited by historians or other sources. The question of why the word “archives” has been adopted to refer to collections of materials is one for a different discussion, but I do think it’s worth noting that this co-opting of the word does seem to be a rather recent development.

I hope the efforts being discussed today encouraging more rigorous assessment of digital historical representations will result in a greater understanding and appreciation of what makes archives distinct from these other kinds of products. I often fear that this appreciation and understanding is being lost as fewer historians work with “old-fashioned” physical archival collections, and do most of their work online, where it is easy to think that all digital collections are the same. The value of the collections of materials preserved in archives often lies in the relationship of the records to each other—what’s called the archival bond—which means that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. As a whole, the materials provide evidence about the activities of the creator.

In considering the topic of this session, I’d like all of us to consider this as two way street. It’s heartening to see archival concepts such as appraisal and provenance being discussed at an AHA session and so information flow from the archival literature to this audience, and hopefully this will continue. On a related topic, I’m always interested in hearing how much historians actually know about either archival theory or practice. Anecdotal evidence provided by many of my archivist colleagues suggests that such knowledge is, shall we say, uneven. So that’s another topic that might be worth discussing—how much do historians know about archives and what more would be helpful or necessary to assist in their work.

But I also want to see information flow the other way, and I hope we can get into this a bit in the discussion that follows. That is, I’m interested in learning what digital historiography, that is the study of the interaction of digital technology with historical practice—what can this new field of study and you as historians tell the archival profession—and me specifically. How has the way you do your work changed? And how can archives and archivists do things differently to assist in that?

Today’s conversation is about how digital technology has changed the way you do your work as historians, and certainly it has also effected the way archivists do our work as well. Among the most significant of those ways is in the increased workload to create descriptions and digital copies to post online, find ways to collect and preserve digital materials, and of course, actively connect with the public via the ever widening world of digital tools and social media. Digital technology has increased the user base for archival resources, meaning that the connection between our historian users and archivists is more diluted than it was in the past. In prioritizing our work and establishing our practices, archivists are trying to meet the needs of the broadest range of users. In so doing, it’s possible that the more specialized needs of historians—if indeed they are different from other users—are not being met. We need to keep an ongoing dialog between our two professions to ensure that we’re all working together as effectively as possible to support the historical enterprise.

I look forward to discussing both archival theory and practice, and hopefully historical practice as well, in the discussion that follows, and in many subsequent conversations.

—

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 4: Kate Theimer, “A Distinction worth Exploring: ‘Archives’ and ‘Digital Historical Representations’”

Digital Historiography & the Archives [3/5]

papers delivered at the 2014 AHA conference.

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 3: Katharina Hering, “Contextualizing digital collections based on the principle of provenance and the tradition of source criticism”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

—

Katharina Hering, “Contextualizing digital collections based on the principle of provenance and the tradition of source criticism”

[The following remarks have been slightly revised from the original presentation. I worked on this paper as an independent researcher, and it is not related to my position with the NEJL.]

Traditionally, the archival concept of provenance refers “to the individual, family, or organization that created or received the items in a collection,” and the principle of provenance suggests that records originating from the same source should be kept together, and not interfiled with records from other sources to preserve their context. (See the definition of provenance in SAA’s online glossary of archival and records terminology.) In her article, “The Death of the Fonds and the Resurrection of Provenance: Archival Context in Space and Time,” (Archivaria 53, Spring 2002:1-15) the Canadian archivist Laura Millar emphasizes the importance of recognizing provenance as the key element of archival arrangement and description. At the same time, Millar argues for an expanded understanding of provenance as a combination of creator history, records history, and custodial history. Her broadened concept of archival provenance is based on a comparative analysis of the concepts of provenance in museology, archaeology, and in archives, all of which have slightly different traditions and meanings. She further argues that a respect de provenance offers a much more useful and realistic basis for a broader contextualization of records than the principle of the respect des fonds (see the definition of fonds in SAA’s online glossary of archival and records terminology), which has traditionally shaped descriptive practice in government archives.

While emphasizing the importance of provenance as a key archival principle, Millar – among others — acknowledges that there is a discrepancy between aspiration and practice: While most archivists agree that providing information about the provenance of collections is critical, this understanding is not always reflected by archival practices. Frequently, the fields in archival finding aids or catalog records, where information about provenance is supplied, remain sparse, or empty. Sometimes, this may reflect that this information is not available, and sometimes existing information may not have gotten transferred from institutional documentation to finding aids. (* Touching on a related aspect of this issue was a discussion on Archives Next as to whether users care about provenance.)

[Depending on the content and cataloging standard used, the relevant fields differ. In APPM, which was replaced by DACS, there existed a field for information about provenance. In DACS, the relevant fields to include information about provenance are administrative/biographical history; custodial history, and immediate source of acquisition, in ISAD (G), the field for custodial history is called archival history. Related and relevant MARC fields are 541, 545 and 561. Provenance is not one of the 15 elements of the simple Dublin Core metadata element set, but part of the qualified Dublin Core set. Thanks to Kate Theimer for suggesting the clarification regarding the relevant fields.]

The lack of information about the provenance of collections, or items, is exacerbated in digital archives and collections, or, to use Joshua Sternfeld’s term, collections of digital historical representations. As Joshua Sternfeld has highlighted, items that become part of digital collections frequently get detached from their original collections, and in that process, existing information about the original provenance of the item of can easily get lost. Also, just as in many physical archives, the contextual information about the provenance of digital objects in born digital collections may not get collected in the first place. Supplying information about provenance in digital archives is also more complicated due to the massive scale of many collections (as J.S. has outlined), and due to the fact that one has to distinguish between the provenance of the original record, item, or collection, and the provenance of the digital historical representation, or collection of digital historical representations. Thus, digital collections often require additional more than one layer of information about provenance.

The reasons for the lack of adequate contextual information about provenance of digital historical representations are complex – there may be technical, conceptual, institutional, and economical. These significant challenges, however, do not diminish the need and ethical obligation (Jane Zhang presented a paper on Archival Context, Digital Content, and the Ethics of Digital Archival Representation,” which she mentioned in a contribution to the discussion about provenance on Archives Next) for providing adequate contextual information about items, collections, or digital historical representations. I believe that the tradition of source criticism in historical theory and methodology complements the archival principle of provenance, while underscoring the importance of adequate contextualization of records, collections, and digital historical representations.

Source criticism has been an integral part of historical theory and method since the concept was introduced by Prussian historian and philosopher Johann Gustav Droysen, and later developed by Ernst Bernheim. Droysen in his Outline of the Principles of History (1st German edition in 1867, first English ed. In 1893) defined the task of criticism as to “determine what relation the materials still before us bears to the acts of will whereof it testifies.” Droysen distinguished various elements of criticism: criticism determines the genuineness of a source, it addresses the development from earlier and later forms of the materials, it criticizes the validity of the information and the source, and the correctness of the information. It also includes the critical analysis of the information in the source itself: which events and developments does it reflect, how was the description influenced by its contemporary context, who was the author, how did it relate to other sources of the time? (Droysen, Outline, paragraph 26-36) Droysen emphasized that the outcome of the critical analysis was not the exact fact, but rather the ability to place “the materials in such a condition as renders possible a relatively safe and correct judgment.” Historian and philosopher Ernst Bernheim later expanded and specified Droysen’s theory (Lehrbuch der historischen Methode, 1st German ed. 1889 – Bernheim’s Lehrbuch was never translated into English). Especially relevant is Bernheim’s distinction between internal and external source criticism – the critical analysis of the content of the source v. the analysis of the creation context or provenance of the source. Based on Laura Millar’s definition of provenance, one could also understand external source criticism – when applied to individual records as well as collections — as the investigation of creator history, records history, and custodial history.

Certainly, the tradition of source criticism has to be situated in its time and historical context in the late 19th century, and the notion of a “source” itself can be rather problematic, as Michael Kramer highlights in his perceptive criticism of the essentialist connotation of a “source” as something that can be exploited by the historian (see M.K.’s later remarks). Still, the tradition of source criticism and the archival tradition and concept of provenance complement another in highlighting the importance of collecting and providing contextual information for sources or collections. Combined with a broadened understanding of provenance, the tradition of source criticism can support archivists, historians, librarians, digital humanists, and others with developing a set of questions and a vocabulary that can aid the analysis and description of digital collections, or digital historical representations alike. Source criticism — in a reformed, modern version, which was developed and theorized by the late Swiss historian Peter Haber (see: Peter Haber, Digital Past, München: Oldenbourg 2011, among other publications) as well as provenance are important elements of the critical digital historiography that Joshua Sternfeld has outlined.

But how can such an ambitious goal, backed up by archival and historical theory, be implemented? What are the challenges at specific institutions? What are possible practical approaches for archivists, historians, librarians, and others to collaborate to collect and provide adequate, critical, contextual information about digital historical representations? How can the contextual information that historians gather in the course of their research make their way into archival finding aids or catalog records? How can the contextual knowledge about collections that archivists have gathered help historians with developing source critical analyses? And what can researchers and archivists do if they find that digital historical representations lack adequate contextual information? How can source criticism lead to resource and database criticism? How can information professionals, including archivists, and researchers, including historians, voice their concerns when faced with a lack of contextual information provided by big commercial databases, such as JSTOR, Ancestry.com, EBSCO, and, of course, Google, over which they have no control? Could collaborative teams of history liaison librarians, archivists, and historians, develop portals that help with supplying contextual information about the provenance of specific collections made available by commercial databases that allow a critical, informed, use of these resources?

—

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 3: Katharina Hering, “Contextualizing digital collections based on the principle of provenance and the tradition of source criticism”

Digital Historiography & the Archives [2/5]

papers delivered at the 2014 AHA conference.

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

—

Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

joshsternfeld@gmail.com, twitter: @jazzscholar

The following remarks were delivered at the AHA Roundtable Session #83 Digital Historiography and Archives . They have been slightly modified for the online blog format. Please note that the concepts presented here are a work-in-progress of a much larger project about digital historiography; I welcome additional comments or feedback. Finally, the statements and ideas expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of my employer, the National Endowment for the Humanities, or any federal agency.

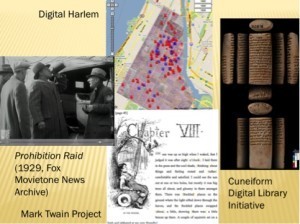

What do the contours of conducting history in the 21st century look like and how are they changing? As we face a whirlwind of activity in reshaping historical methods, theory, and pedagogy, one thing is certain:

The 21st-century historian has access to more varied and immense amounts of evidence, with the ability to draw freely from multimedia sources such as film and audio recordings; digitized corpora from antiquity to the present; as well as born digital sources such as websites, artwork, and computational data.

To get a sense of this abundance of evidence, let’s consider for a moment a very contemporary historical record, one that is undergoing perpetual preservation.

In April 2010, the Library of Congress signed an agreement with Twitter to preserve all 170 billion of the company’s tweets created between 2006 and 2010, and to continue to preserve all public tweets created thereafter. On a daily basis, that translates to roughly half a billion tweets sent globally.

The case of preserving Twitter is a task that should excite both archivists and historians. For archivists, the primary technical and conceptual challenge is to provide timely access to such a massive corpus. As of last year, a single computational search by a lone researcher would have taken an unreasonable 24 hours to complete, which is why the Twitter archive remains dark for now.

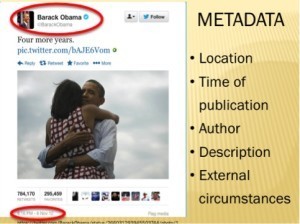

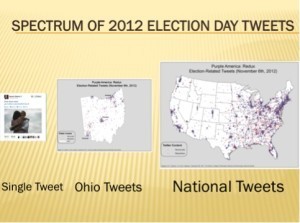

For historians, the challenge to analyze the Twitter corpus is equally if not more complex. Our traditional methods of close reading and deep contextualization fail to penetrate the social media network. To illustrate my point, we can conduct a close reading of a tweet in probably less than 5 seconds. At 8:16 PM, on November 6, 2012 – election night – President Barack Obama tweeted “Four more years” followed by an image of him embracing Michelle Obama. Granted, we could spend some time on the image that was selected for the tweet that accompanied Obama’s re-election announcement, but the statement itself, “Four more years,” leaves little to the analytic imagination. And there you have it, a close reading of a tweet’s text!

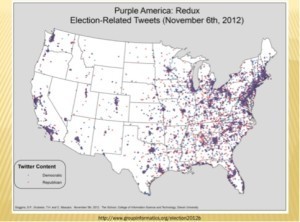

But when you consider that this single tweet, containing a three-word sentence and an image was retweeted 784,170 times and favorited nearly 300,000 times [see the red highlight circle above], you begin to get a sense of the vast network of people that lies just beneath the surface. As historians, we ought to be curious about the transmission of this tweet, including the demographics of who sent it, how quickly it circulated, and whether additional information was delivered as it raced through the Twittersphere. When you consider that at least 31 million additional tweets were sent on Election Day, you begin to realize that as historians, we will need to reorient our approach to studying the past that does not involve reading every one of those 31 million lines of text.

I have selected the Twitter corpus purely for illustrative purposes as just one of several possible examples of how digital media is transforming our relationship to historical materials.

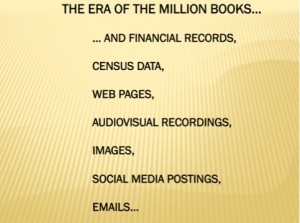

The point is, historians now must decide whether to work with a limited set of sources, say from a circumscribed set of archives or special collections, or materials that would be impossible to digest in a lifetime. In other words, we must learn to maneuver in not just the era of the million books, but the million financial transaction records, web pages, census records, and a wealth of other data points.

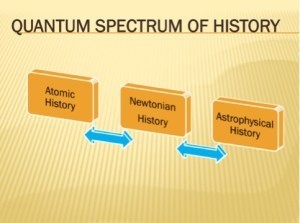

In today’s talk, I would like to outline two concepts – scale and appraisal — that are critical for orienting how we work with an abundance of historical evidence made accessible by digital archives, libraries, and collections. To help us grasp the difference between digital and traditional modes of history, I propose we think about history in a quantum framework.

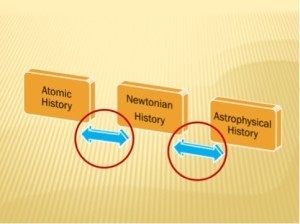

Just to be clear, I am not suggesting that a person could ever be in two places at once, or that historians will one day be able to “quantum leap” back in time with a companion named Al to rewrite the past! Rather, by placing history on a spectrum based on the scale of historical information, much like how our own physical environment can be placed on a scale from the subatomic to the astrophysical, we can reorient our understanding of human behavior, movement, networking, and activity.

Appraisal, to borrow a concept from archival theory, provides the framework to interpret the results of analysis conducted along the quantum spectrum. Whether we realize it or not, historians have always conducted appraisal of historical data, that is, we have always assessed what information has value as evidence. And let’s face it; we have been notoriously poor at explaining our methods of working in the archives. We have had a tendency to dismiss explaining how we search for and discover archival materials, organize those findings, and then present those findings in a cogent argument.

Our physical limitations of what we could read and collect have forced us to adapt, to draw upon inference, annotation, instinct and most of all experience as guides toward appraising evidence. The sheer size and scope of today’s digital sources does not afford such lax methods, but rather demands a level of methodological rigor that we are not yet accustomed to applying.

My discussion about scale and appraisal of historical evidence, and digital historiography in general, is grounded in a pursuit to define historical understanding in the digital age. Historical understanding explains how we learn about the past, authenticate evidence, and build arguments. In short, historical understanding answers the questions basic to all humanistic endeavors: how and why? Why did a phenomenon occur and why ought we consider it significant? How do we explain a pattern of human behavior? These basic questions should be the guiding force behind all activities in digital history, from the building of new tools to interpretative projects. All too often, however, historical understanding has been drowned out in the noise of historical big data and the glitz of complex software, leaving skeptics to wonder whether digital history can fulfill its promise of revolutionizing the discipline. Applying methods of digital historical appraisal based on the scale of evidence sets us on a path towards validating conclusions and therefore contributing to historical understanding for a new era.

SCALE

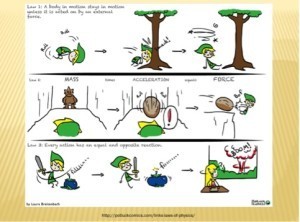

Let’s begin with the concept of scale, where I will borrow liberally from the sciences. There is a theory in physics that the Newtownian laws of our physical environment may not necessarily apply at the level of the extremely small or extremely large.

The properties of gravity, mass, acceleration, and so forth begin to break down when you consider subatomic particles too small to detect using conventional instruments. Mystifying substances such as dark matter seem to disrupt these same properties at an astrophysical level. While there are scientists who are working towards a unifying theory, for the time being these levels, and the laws that govern them, remain distinct.

I would argue that history operates in a similar fashion, with different levels of historical information, or data, with which one can choose to work. Up until very recently, the vast majority of historical work operated at what I call the Newtonian level, that is, the level at which a single historian can synthesize data into a coherent narrative argument. Our basic definition of history, the study of change over time, reflects a Newtonian mindset. Much like Newtonian physics, Newtownian history has been incredibly successful in building an understanding of the past, particularly when considering the laws of causality and the interactions of individuals and societies.

Just as the principles behind inertia inform us that an object in motion tends to stay in motion or an object at rest stays at rest, we have developed over time principles of rhetoric and logic that allow us to work within a degree of epistemological certainty. History in the modern era, in other words, works best when investigating the likelihood that event or person or society A may or may not have contributed to outcome B, however abstract that outcome may be. My point is that the type of linear narrative history that has developed over the centuries has depended in part upon the degree of access to historical data, our ability to synthesize that data into a cogent argument, and our modes of representation.

What happens to the fabric of historical work if we extend our access to information along a quantum spectrum? We begin to open new levels at which we can do history.

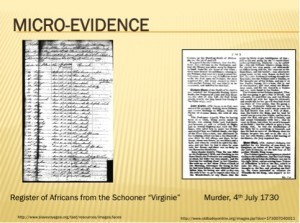

On one end of the spectrum, there is the study of a micro piece of evidence, much as we have always done but at a level of precision that may not have been previously possible. We can study the digitized manifest of a slave ship, or a criminal trial in London, each with a rich history worthy of unraveling.

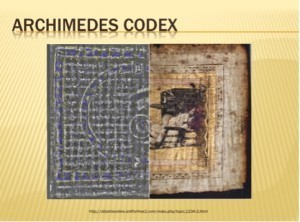

Digital technologies have also allowed historians to probe the materiality of artifacts in ways that have unearthed new findings. Methods of spectral analysis, for example, have detected pigments underneath parchment, such as was the case with the discovery of the Archimedes Codex, or the revelation that Thomas Jefferson originally intended for the word “citizens” to be “subjects” in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.

Returning to our example of Twitter, we might consider the single tweet. While earlier I may have dismissed a close reading of a tweet sent by Obama, there is in fact an extraordinary amount of visible and hidden information around the text message that one can extract from a published tweet that conveys a history unto itself. According to the Library of Congress, each tweet can contain 50 unique pieces of information, or metadata, such as the time it was published, the location from where the tweet was sent, and information about the person who sent it [see red highlight circles]. Besides information contained within the tweet, we may wonder about external circumstances surrounding its creation, for example, exactly where Obama was when he sent the announcement? Did he even compose it himself? Metadata can get us part of the way toward reconstructing the context behind the creation of a tweet, but we likely will need other sources of information outside Twitter to assemble a richer portrait of a moment in time.

On the other end of the spectrum, as suggested earlier, are the millions of tweets that may be connected to a single event, person, or community. Besides tweets, this extreme end of the spectrum also comprises massive databases, storehouses of information of all varieties from complex texts, to statistics, to non-textual media.

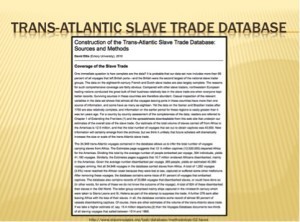

One ship’s manifest is combined with nearly 35,000 others to form the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (http://www.slavevoyages.org/tast/inde...), and one London trial is collated with nearly 200,000 others conducted between 1674 and 1913 to form The Proceedings of the Old Bailey (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org). For the remainder of my talk, I want to focus on this end of the spectrum.

As you may imagine, when you move into the realm of the vast, the traditional laws governing historical understanding begin to breakdown.

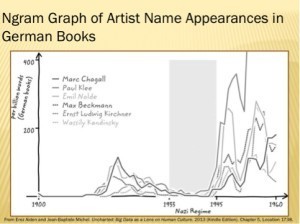

Take the graphs produced by the scientists behind the Google Ngram Viewer (https://books.google.com/ngrams), an analytic tool that counts the frequency of words and phrases across a portion of the millions of books scanned by Google. The scientists have demonstrated, for example, that by tracing the appearance of selected names we can generate graphs that reveal periods of state censorship. In the example above, the graph suggests that between 1933 and 1945 National Socialists in Germany suppressed works by artists deemed Jewish or degenerate. On the one hand, these graphs are compelling for suggesting the effectiveness of the censorship campaign. On the other hand, they don’t necessarily reveal anything historians don’t already know, and they certainly don’t explain the causes behind the statistical trend. We have no idea from the graph alone who enforced the artist ban or the rationale behind its enforcement. In other words, this big data visualization has wiped away any remnant of historical causality, and if you feel a sense of unease at this prospect, you are not alone.

Our unease should suggest that we need retake the reigns from the computer scientists and build a new framework for working with big historical data, one that can harness computational power while exploring deeper, less obvious connections. But where do we begin?

Returning to the physics analogy, the massive particle accelerator known as the Large Hadron Collider built in Switzerland was designed in part to test for the existence of the Higgs Boson, or “God particle,” by smashing together atoms and computationally sifting through the enormous amounts of resultant data.

Of course, before the Large Hadron Collider could be trusted to produce reliable data, it needed to be calibrated and recalibrated according to stringent standards established by the scientific community. I would argue that digital history is lodged in a perpetual state of experimentation, smashing data together to see what is produced, but not yet at a stage of calibration to produce a substantial body of worthwhile evidence. We are simply not yet accustomed to working at different scales of data, and a great deal of calibration is still required.

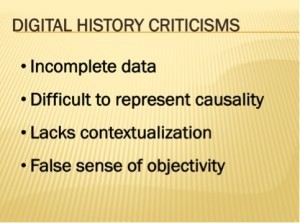

Why is this the case? Why don’t the laws of Newtonian history apply at different scales? The reason is that we have yet to calibrate the digital tools and methods according to historiographical questions both old and new that are suitable for investigation. When we transition into a new scale of data, we naturally introduce variables that have the potential for invalidating our findings. Skeptics declare – often rightly so — that historical data is incomplete, fuzzy, and ill suited for methods that operate on a presumption of scientific certainty. They also argue that digital media supplies a false sense of objectivity, or that the information lacks proper contextualization.

There is a lot of validity to these criticisms. More often than not, historical data sets are messy, and vulnerable to an assortment of critical attacks. Only by applying our skills of critical analysis will we feel comfortable participating in the creation and use of digital tools such as the Ngram Viewer. My point is that rather than dismiss our natural critical tendency in the humanities, which often leads to unproductive deconstruction for its own sake, we must use our skepticism to calibrate our data sets and the methods used to interrogate them. This brings me to digital historical appraisal, which, in a nutshell, is the process by which we profile a dataset.

DIGITAL HISTORICAL APPRAISAL

As I suggested earlier, we rarely stop to appreciate the complex analytic assessment that occurs during our appraisal of archival materials. Who has the time to acknowledge systematically the reams of materials that we reject before we stumble across the items we deem as possessing evidentiary value? Archivists would explain that evidentiary value derives from basic archival principles such as respects du fonds, which assures us that the original order of the materials has been preserved. As the other panelists will discuss further, the endeavor of organizing archival materials is an intellectual exercise and a subjective one at that. The decision-making process to arrange and describe a collection contributes to the collection’s contextualization and influences historians’ access to materials.

Contextualization also applies in the digital environment, although the risk of separating a digital record or artifact from its provenance raises the stakes considerably. Whereas historians feel comfortable assessing a collection defined in linear feet they have yet to find reliable methods for assessing collections defined in terabytes. The absence of visual cues thanks to cold, monolithic servers and hard drives, however, need not deter historians from gaining greater intellectual control over a digital collection. We simply need new methods to apply our historical appraisal.

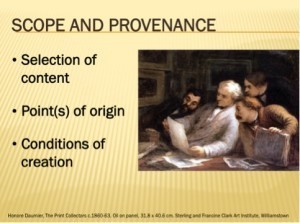

There are two elements vital to conducting an appraisal: scope and provenance. As with analog materials, we want to consider what digital materials have been selected for an archive or collection. By determining which items were kept and which ignored or discarded, we can begin to construct the contextual boundaries, or scope, of a collection. Besides the selection of materials, we also must account for whether one can trace data back to their point of origin, what archivists call provenance. For materials that were originally in an analog format, we would want to know their original archival location, whereas for born digital information we may want to know under what conditions data are generated. Without such information, or metadata, digital records pose a greater risk of becoming de-contextualized, that is, they have the potential to lose the value they may possess according to their relationship to other records. Just as we would be wary to trust a lone document that has been divorced from its archival folder or box, a digital item without metadata places additional strain on validating its authenticity and trustworthiness.

Think for a moment of how we might treat Obama’s tweet if we didn’t have the unique markers that signal that he was the author, or the time and location from which the tweet was sent. Would we still trust it as reliable evidence?

When you also consider for a moment the provenance of tweets, this element too appears more complex than at first glance. Although we may have a record of a tweet’s original time posting and possibly geographic point of origin, tracking its distribution in subsequent retweets, quotes, and conversations introduces a host of challenges that requires a combination of precision, deftness, and creativity in critical thought. Provenance also takes on a whole different meaning when you consider that the historical value of tweets often comes from referencing events, conversations, and websites that have a provenancial record outside the Twitter communication stream [marked by the arrows above]. In other words, historians may be interested not just in the provenance of the tweet itself, but the vast corpus of materials connected to those tweets.

There are researchers in other disciplines who are conducting experiments to answer these very questions in information science areas such as socioinformatics and alt-metrics. My point is that historians must play a role in this research, as we realize that the digital media of today becomes the artifacts of tomorrow. Participation begins with what historians do best, applying a critical framework to appraise historical data.

Thankfully, we are beginning to see examples of what digital historical appraisal may look like. Pragmatically, the methods of appraisal, and even the modes for explaining these methods will depend on the size of the collection and the nature of the project. At times, appraisal may require algorithmic computations measuring particular elements of the data. One such example worth noting is the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. The lead historian on the project, David Eltis, wrote an entire essay entitled “Coverage of the Slave Trade” that outlines the quantitative methods employed to estimate the data set’s completeness. Drawing upon accepted evidence from the field, Eltis contends that the nearly 35,000 trans-Atlantic voyages documented in the database can help scholars “infer the total number of voyages carrying slaves from Africa,” by concluding that the database represents approximately 80 percent of the vessels that disembarked captives. Note that the author elected to communicate his appraisal of a complex database using an “analog” format –the essay– that ought to remind us that visualizations may require just as much written explanatory text as a scholarly article or monograph. In short, relying upon a combination of statistical analysis and historiography, the developers generated a claim about their database’s representativeness. The interplay between historiography, appraisal, and digital modes of representations will require much more consideration as we continue to shape digital historiography.

DIGITAL HISTORIOGRAPHY

At its core, digital history has enhanced the capacity of historians to investigate the past at different levels of inquiry. By considering the concepts of scale and appraisal in tandem, my hope is that the field will move toward a pragmatic approach to conducting digital history. The size and scale of information will determine, in the end, the mode of inquiry and the results that are possible.

In previous work, I labeled this pragmatic approach to conducting history digital historiography, a term that has had some bearing on the title of the AHA session. I defined digital historiography as “the interdisciplinary study of the interaction of digital technology with historical practice.”[1] This definition provided an opening to consider digital history at every stage of production by encouraging the practitioners to consider how digital historical understanding should determine which theories and methods to adapt for a given pursuit.

Digital historiography recognizes that historical understanding possesses fundamentally different qualities in analog versus digital environments. Instead of adapting the historiographical questions of yesterday to the tools and methods of today, we ought to recognize that digital history will yield new understanding, new modes of inquiry that can complement our Newtonian tendencies to want to explain causes and effects.

In short, we can characterize digital historiography as mediating among the different levels of quantum history. By refining our ability to appraise historical data, we will become adept at moving back and forth among the levels.

In Twitter terms, this would be the negotiation of going from a single tweet, to a circumscribed network of tweets such as a professional society or state, to the national and even global expanse of tweets, and back again. How does each level inform the other and where are the connections that permit us to trace activity within the network?

In terms of the Ngram Viewer and similar tools, a query produced at a macro big data level may compel us to return to the underlying sources for additional close reading and analysis.

The key – and this is where archivists and historians must bridge the disciplinary divide – is to produce mechanisms that allow us to pinpoint the bits of data or texts that warrants our attention. In other words, we may want to develop methods for reducing a million books down to a more manageable set of materials.

Historians and archivists, therefore, ought to concern themselves with the areas of transition, the connections between macro datasets and those that can be consumed at a human level. This challenge requires a depth of knowledge of how digital information is managed, organized, and made accessible. In short, it requires coordination among historians, archivists, and other information professionals. By appraising more precisely the size, scope, and completeness of a given collection of historical data, we will begin to construct a pathway towards posing and answering some of our most complex and enduring questions about the human condition.

Thank you!

[1] Joshua Sternfeld. “Archival Theory and Digital Historiography: Selection, Search, and Metadata as Archival Processes for Assessing Historical Contextualization.” The American Archivist. v. 74, no. 2. Fall-Winter 2011. 544-575.

—

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Digital Historiography & the Archives [1/5]

papers delivered at the 2014 AHA conference.

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

Part 5: Michael J. Kramer, “Going Meta on Metadata”

—

Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

The following series of blog posts by Joshua Sternfeld, Katharina Hering, Kate Theimer, and Michael Kramer is based on our session at the AHA meeting in 2014 on Digital Historiography and the Archives. We conceptualized the session as an interdisciplinary round table discussion. Short presentations by each panelist led to a rich and multifaceted discussion with the audience. Expanding upon this format and our engaged in-person discussion, we hope that this series of linked blog posts will serve as a virtual, extended round table. Because it exists in the liminal, intermediary space between traditional conference session and formal publication, we imagine it as an experiment in new forms of “open source” scholarly communication. We will post our discussion papers in sequence with a concluding summary of the discussion that took place at the session itself. In sharing our work in provisional form, we encourage readers to continue this discussion on the blog by posting comments, ideas, reflections, and criticisms. If you wish to use this material in another place or venue, we ask that you contact each presenter directly for explicit permission to quote from the works presented here. The contact information for all presenters can be found at the end of this introductory post and in each subsequent post.

The preservation, analysis, and representation of digital information in digital collections, archives, and other media poses complex, challenging, and often confusing, issues for historical researchers, archivists, digital humanists, and librarians alike. Whether we even call these digital materials “archive” is at stake. We hoped to address some of these issues in the session, while also discussing some of the elements of a framework or vocabulary that can support a critical appraisal of digital information. In his 2011 article in the American Archivist, panelist Joshua Sternfeld introduced such a framework called critical digital historiography, which he defined as the “critical, interdisciplinary study of the interaction of digital technology with historical practice.”

All participants in the panel echoed Sternfeld in emphasizing how archival theory and practice need to be an integral element of such a critical framework, along with evolving historiographical and professional practices. The digital medium has challenged historians to expand their knowledge about archives, and understand their function in generating scholarship and knowledge. But what might be the key theoretical and methodological questions raised by digital archives or digital collections as they pertain to historical practice? What materials do archives collect and preserve, and why? Which materials are selected, and which are excluded? What are the driving forces and principles guiding the contextual information about collections provided by archives? Which political, social, economic, and cultural power relationships now structure the archives? These are the questions that archivists and historians might come together to confront in critical and productive ways.

Fortunately, not only has the digital medium unleashed a heightened awareness of established archival principles and historical practice, it has also introduced new lines of theoretical inquiry. Historians and archivists are beginning to work with sources of varying scope, format, and provenance, thereby challenging both fields to reconsider the limits of historical inquiry, the contextualizing properties of metadata, the design of access systems, and the engagement of new audiences. In short, trends in digital scholarship and practices have contested our collective conception of “ the archive” as well as the role of the 21st-century historian.

What became evident from the session was that historians must collaborate with information professionals, including archivists, to create critical contextual information for sources, reference resources, and repositories as well as new kinds of scholarly work that harnesses the power and registers the challenges of the digital archive, while serving a diverse community of users composed of researchers, educators, information professionals, students, artists, policymakers, and members of the public as a whole. The question is how? What areas of research should be explored and what methodologies and theories are already under development? We hope that sharing materials from the roundtable, even in provisional form, can provide a catalyst for a sustained discussion.

Michael J. Kramer (AHA Session Moderator) (mjk@northwestern.edu)

Katharina Hering (khering23@gmail.com)

Joshua Sternfeld (joshsternfeld@gmail.com)

Kate Theimer (kate.theimer@gmail.com)

—

Table of Contents:

Digital Historiography and the Archives, 2014 AHA Conference, Washington, DC, Friday, 3 January 2014

Part 1: Katharina Hering, Joshua Sternfeld, Kate Theimer, and Michael J. Kramer, “Introduction”

Part 2: Joshua Sternfeld, “Historical Understanding in the Quantum Age”

What Is Folk Music, Anyway?

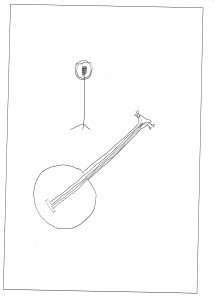

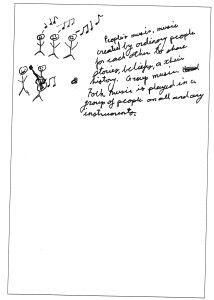

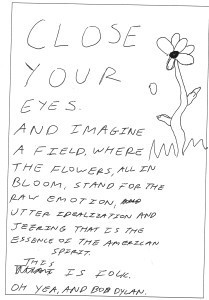

One of the themes that has led me to work on a history of the US folk music revival within a digital humanities framework is that it allows for a heightened sense of what it means to criss-cross the line between the handmade and the machine-made. Considering folk music history using digital tools and settings puts us in what Joel Dinerstein describes as a “technodialogical” mode. So, in the first meeting of Digitizing Folk Music History, an upper-level research seminar I teach in the History Department at Northwestern, I ask students to draw on paper a sketch in response to the question, “What Is Folk Music, Anyway?” Then we digitally scan these sketches and upload them to our collective WordPress blog.

This movement from the handmade (though written with mass-produced writing instruments on commercially-made printer paper!) quickly becomes a chance to think about mediation, about different kinds of technologies, about historical analysis as it relates to contemporary perceptions, and about the relationships among forms of thinking that stretch from the vernacular and immediate to the dematerialized and recontextualized (in the process, of course, troubling the waters of how we organize our understandings of these terms). What does it mean to move between the handmade to the mass-mediated, particularly when it comes to music, and what can a closer look and listen to the US folk music revival teach us about long-running issues of culture, labor, structure, agency, and technology in America and the world?

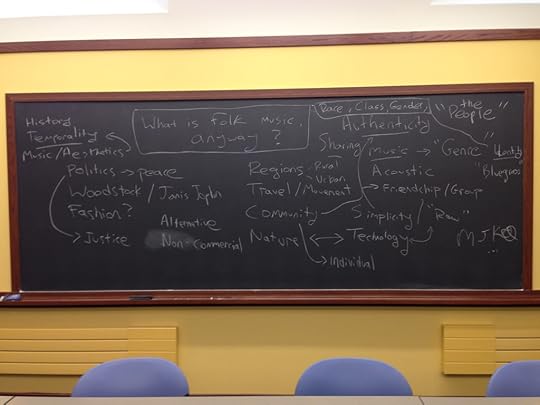

Below are the sketches students made. They will revisit these during the last week of class after immersing themselves both in the history of the US folk music revival and new methods of digital historical inquiry to see what has remained the same for them and what has changed. Following the sketches, a photograph of the board from the first day of class, on which we collectively wrote down keywords and themes that arose in making the sketches and discussing them in class. Face-to-face interaction complements technological interaction here (no distant-learning MOOC this). You can see the students already complicating their initial impressions of folk music as they begin to contemplate their sketches (we put each one up on the classroom screen using a document projector). From pictures of flowers, mountains, acoustic guitars, banjos, fiddles, and the like (all perfectly valid!), we start to delve into more robust concepts: genre, commerce, urban and rural settings, authenticity, technology, identity (race, class, gender, ethnicity, regionality), space and temporality, politics, and more.

At the end of this post, a few final reflections by me on generational experiences and changing perceptions of the folk music revival.

Student sketches:

The board, “What Is Folk Music, Anyway?,” 9 January 2014:

What I was struck by in our discussion was just how much the folk revival of the early 1960s has melded into rock music, Woodstock, hippies, singer-songwriter associations of the late 1960s and 1970s. Does this have something to do with the age of my students’ parents, few of whom are of the late 50s/early 60s generation and far more of whom came into adolescence and adulthood in the 1970s? I wonder. A few students have gotten a taste of the current roots music revival, whether through more commercially-successful bands such as the Avett Brothers or Mumford and Sons or through deeper engagement with local revival scenes and communities. And a number have gotten more curious about the folk revival due to the recent Coen Brothers’ film, Inside Llewyn Davis. All of which is quite different from my own inter-generational experience of the folk revival: my parents were born in the 1940s while I would guess most of my students’ parents were born in the 1960s.

This makes for quite a different context for considering the folk revival, particularly its apex in the early 1960s. So one task in this seminar is for my students and I to grapple with the shifting sands of generational relationships to American popular and vernacular music, to go further back into the folk revival past to the 1930s (and earlier), and to track it out into recent decades more accurately. We must shake up dominant assumptions, periodizations, and understandings of US folk music born from earlier generational and inter-generational confrontations with the legacy of “the sixties.” Rather than position folk music out of time as “traditional” music, we must join the effort to contextualize the very construction of traditions. Given the forward-march of time from which we must now look at and listen to folk music’s past, receding and fading into history yet also, through sound, leaping into our contemporary experiences with startling immediacy and currency, we need to keep trying on fresh perspectives and conceptual positions. Which is to say that we must enter into the process (folk process? historical process?) of continually re-historicizing the revival even as we re-revive it for scrutiny and study.

For more on the Winter 2014 installment of Digitizing Folk Music History, click here.

For past posts on Digitizing Folk Music History seminar, click here.

For more on the Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival project, click here.

January 18, 2014

Thinking Through Sound

image sonification and the study of the ephemeral past.