Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 84

November 30, 2013

The Republic of Rock…Live in Concert @ Brown University

I will be at Brown University this coming week to talk about The Republic of Rock:

Michael J. Kramer

The Republic of Rock: Music and Citizenship in the Sixties Counterculture

Monday, December 2, 2013, 3:30pm

Petturutti Lounge, Peter J. Roberts Campus Center

I will also be talking about the Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project:

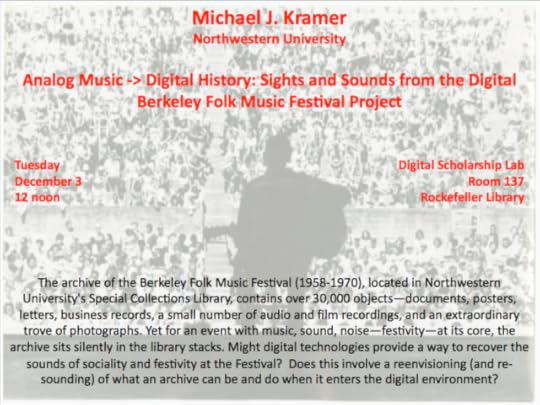

Analog Music -> Digital History: Sights and Sounds from the Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

Tuesday, December 3, 2013, noon.

Digital Scholarship Lab, Room 137, Rockefeller Library

Liberation Struggles

more reflections on christopher lasch’s reflection.

The following x-post comes from an ongoing conversation with Christopher Shannon at the Society of US Intellectual History blog. We have been debating the legacy of Christopher Lasch’s social criticism.

—

What is the “common life” and how do we achieve it? What is “tradition” and how do we use it to grapple with present conundrums and concerns? These seem to me to be the stakes of Shannon’s critique of my recent post on Christopher Lasch, a post that served as a preview of a longer article I published in the print edition of The Point magazine this fall. To address Christopher Shannon’s critique demands attention to the intellectual orientation from which I understand him to be approaching Lasch—and from which he comments on my interest in recovering the mid-career work of this impressive but certainly not perfect thinker.

Shannon uses my recent writing on Lasch to retrofit and restate his general position on secular modern liberalism, a stance of rejection and condemnation that he first mapped out in his striking book Conspicuous Criticism (and expanded in A World Made Safe for Differences). This leads him to contest my contention that the mid-career Lasch is worth recovering in comparison to the later Lasch, who I view as retreating from his earlier confrontations with pressing social issues on their own terms. Not entirely, but in crucial ways, Lasch gave up on that mission in exchange for a seemingly more stable conservative vision that was, because of its intensive efforts to locate authentic and fixed roots for the common life, paradoxically a kind of escapist turn.

I cannot quite tell from his comments if Shannon read the article I published in The Point, or if he is just responding to the post about the article. In the article itself, I am far more sympathetic to the later work of Lasch than my post perhaps indicated. There is, yes, a touch of the declension narrative to my interpretation. But that is because the vast bulk of Lasch scholarship is much more of an ascension narrative: the “Passion of Christopher Lasch,” as I have teased Eric Miller about his excellent biography of this important thinker (a biography that is particularly moving and illuminating on the later Lasch’s turn to theology and his morally and politically infused decision not to undergo chemotherapy when he was diagnosed with cancer).

So I grant that there is an effort on my part to recover a mid-career Lasch that is overshadowed by the later work and life. I do think though, despite my critique, that we also have much to learn from Lasch’s final decade or so of writing. His defense of the family against the encroachments of capitalist market and technocratic state, his recognition of the ideal of progress as, paradoxically, a dead end for making the world a better place, his search for a position of hope beyond the shallow waters of either optimism or its flipside nostalgia, these are all points that are worth keeping in play within the contemporary arena of social and cultural criticism. Like Shannon, though without his turn to traditionalist conservatism, I think Lasch’s later efforts, while at times romanticizing a working-class populism and lumping all professionals, willy-nilly, into the villainous role of out-of-touch elites, have much to offer contemporary social and cultural critics who remain interested in the transformative potential of thinking better about both social injustices and hopes for a better world.

Here’s the difference between us. Shannon contends that the mid-career Lasch I admire is a model of the free-floating, independent intellectual, which, as he argued in Conspicuous Criticism, was a kind of shadowy alter-ego, a doppelganger, to the very technocratic experts and corporate capitalist commodifiers that mid-twentieth century intellectuals such as C. Wright Mills sought to critique, reject, overthrow. Mills’s famous file system of his “Intellectual Craftsmanship” essay are, for Shannon, but a miniature version of the dossiers of the Cold War security state apparatus or the customer research department of the marketing firm on Madison Avenue. Shannon prefers the later Lasch, who grappled with theological perspectives that might provide firmer ground. This Lasch, Shannon contends, transcended the “conspicuous criticism” of modern liberal intellectuals who while they romanticized the lone independent critic were in fact surrounded by file folders and found their craftsmanship but a parallel to the bureaucratic and exploitative structures they scrutinized and so disliked.

For Shannon, Lasch stepped out of the deeper currents of the Enlightenment project in which modern liberal individualism was immersed. He moved away from the strategy of isolating and instrumentalizing the entire world from its smallest everyday elements to its largest forces. Instead, he turned to traditions of humility and limits, boundaries and faith-based tradition. In the process, Lasch came close to overcoming what Shannon labels as the failed modern quest of social and cultural criticism in service of transformation and moral improvement through analysis and rational-critical comprehension. Some things, Shannon believes, should be left as mysteries, should exist outside the scope of critical inquiry. Though he critiques Lasch for looping back into the problematic American mode of the jeremiad, he positions himself in the late Lasch’s footsteps down the path away from modernity. This is fitting, since Lasch was quite literally one of his teachers. But Shannon goes further down the antimodernist track, or, better said, further back along it than Lasch. He draws upon Lasch’s work to advocate that we leave modernity behind entirely. Or better said, we should leave it ahead. Like many “postmodern” theorists (Foucault, the Frankfurt School), Shannon contends that modernity will ultimately eat itself. The Enlightenment project will eventually and paradoxically darken our doors.

I find Shannon’s own thinking on these matters intriguing, even compelling. Even more so, I find his attention to Lasch as an antimodernist important. But I perceive the late and the mid-career Lasch in almost exactly the opposite way than he does. Whereas Shannon sees the mid-career Lasch as a failure for attempting, supposedly, to escape into a fantastical absent-presence as a “free floating” independent intellectual, in the process merely masking his membership in the very professional classes benefitting from the modern capitalism and the technocratic state he sought to condemn, I view mid-career Lasch not as independent, but as engaged. He was hardly independent or free-floating in this work. He was, rather, in deep and careful conversation with those around him. He implicates himself in their pursuits. But he does not merely acquiesce to the trendier obsessions around him, whether it be the vanguardist “new radicalism” of the liberationist left during the late 1960s or the cynical conservatism and cozying up to power of the mainstream liberal establishment or the rising “New Right.”

To my reading, it is not the mid-career Lasch but the later one who, while full of insights into modern America, tilted toward an escapist fantasy: that we can somehow return to a nineteenth-century populism or even Shannon’s idealized premodern traditions without arriving at them within our own modern existence. The mid-career Lasch looked the predicaments of modernity more clearly in the eye, I think. He got face to face with the roiling forces of the 1960s and 1970s. Without turning away, he offered a mode of social and cultural criticism that was sharp, barbed, and very critical. But this work was also sympathetic and filled with a hope born of extended inquiry, listening, and thinking. It represents a staunch refusal to give up on the best aspects of the modernist project while still forcefully critiquing its ironic, vexing, and tragic twists and turns.

The argument I make is that the mid-career Lasch is more useful for contemporary social and cultural criticism because his writing from that time is, in its way, more humble yet determined than his later work. By listening more closely to the voices around him, he expressed a humility of engagement, not independence. He did so not by agreeing or rejecting, but by his willingness to identify, analyze, and clarify shortcomings in the positions of others while granting them credence where he saw fit. This is not “free floating” freedom but rather commitment, obligation, and duty at work.

Indeed, the best aspects of Lasch’s last writings are present in the mid-career essays, book reviews, and social commentaries. The idea of limits, for instance, appears first in this mid-career work. Lasch presents the concept of limits as a possible source for fostering a new kind of common life that does not turn away from uses of the state or the market for good, but rather utilizes them as a way to mitigate or even stop once and for all the worst aspects of these structures. The contemporary left has much to learn from this interest in limits. Lasch’s critique of liberation as an ideal, of progress as the main goal, also remains deeply relevant. What, he begins to wonder in the mid-career essays and fully articulates later in his career, would it mean to approach pressing social issues by exploring not how to break on through to some utopian future, but rather recover useful elements of older traditions, whether they be the cultivation of limits, the affirmational potential of work outside of modern regimes of production and consumption, and the reinvigoration of the private sphere of the family as a foundational site of shared, public, civic virtue? It is not breakthrough he seeks here, but rather the question of what kind of balance might be achieved when vanguardist liberation is replaced by sustained inquiry and a mingling of old and new.

Not only members of the left, but also those on the contemporary right might grapple far more robustly with Lasch’s speculations on these counts. I would hope then that traditionalist conservatives such as Shannon spend as much time critiquing others on the right who advocate “progress” and “liberation” as they do attacking modern liberalism.

Shannon’s response to what he perceives as the dead end of modern liberalism and the Enlightenment project is ultimately quite different from Lasch’s. While Lasch never rejected modernity but sought out ways of altering its worst aspects, Shannon calls for us to abandon the modern Enlightenment project in toto as a method for pursuing moral inquiry and social transformation. Instead, we should return to older, premodern traditions as wellsprings for these kinds of endeavors (or giving up on them entirely as beyond the scope of human comprehension and control). All efforts at achieving freedom against the worst aspects of modernity from within its lines of analytic inquiry will, Shannon argues, be complicit with the very forces they oppose. That these so-called premodern traditions have themselves already intersected with the development of modernity—and that we cannot magically return to them, even by a leap of faith, but through the currents of modernity that already surround us—is something I wonder about. But the point here is that Shannon turns to a particular vision of the premodern, traditional, and conservative in what to me seems an intellectual strategy that seeks to outflank the complicity in the ills of modernity that he perceives in all Enlightenment-descended modes of cultural critique and social science.

In this regard, we might call Shannon’s writing (playfully) conspicuous conservatism. It shows off excessive conservatism in an effort to outcritique, to outradicalize, the traditions of analysis found in the secular, modern, liberal Enlightenment legacy itself! Liberation will arrive, Shannon’s line of thinking implies, by the forsaking of liberation once and for all. This seems to me as much an extension of the liberationist impulse within modernity as a rejection of it. In seeking escape through reactionary rejection, through a certain construction of a pure premodern tradition erected outside and against modernity, it leads Shannon toward a reactionary position that is not too different from the very ideologies he seeks to combat within the confounding modernist tradition of erasing tradition itself. Freedom comes, in this (masochistic?) version of antimodernism, by submitting.

I do not mean solely to hoist Shannon on his own petard here. What I do admire about his work is that he very profoundly helps us consider how as we are unmoored in the pursuit of more, whether it be more abundance, more control, or more understanding and meaning, we lose any attachment whatsoever to the mores—the values and morals—that matter. With no ground to stand on, we sink into the abyss, analyzing our fall all the way down. This is a remarkable warning. What is so oddly dizzying about Shannon’s thinking is that he argues for this reactionary stance from the vantage point of the avant-garde. The reasoning of the most advanced kinds of modern social theory undergird his very retreat from modernity. As a sympathetic commentator, Wilfred McClay, wonderfully put it, Shannon’s work is “a cross between the cultural criticism of the Frankfurt School and the constructive impulses of communitarian Catholic social thought” (McClay also notes, intriguingly, that Shannon demonstrates how these may not be as different as one at first thinks). Shannon is, as McClay points out, as “at home in the precincts of social theory” as he is in the world of conservative thinking. His ability to hook the most postmodern and futuristic modes of recent critical theory back into a traditionalist orientation is as intellectually intriguing as it is disconcerting and strange. His writing is suffused with the most cutting-edge social theory, put into service to undermine itself.

Both mid-career Lasch and the best aspects of late Lasch often arrived at a related position to Shannon’s: the cure was worse than the disease, the liberation from limitations itself was a devil’s bargain, only further enmeshing individuals in what we might call uncommon but unfulfilling lives rather than the common life. Which is to say experiences that were thrillingly liberating at first for the immediate intensity and gratification of their taste of freedom were unsustainable and, ultimately to Lasch, even more alienating than what they momentarily replaced. Liberation was a canard, a phantom, an insidious lure that provided no true and sustainable freedom.

This brings us to the question of second wave feminism, aka Women’s Liberation, and its relationship to the common life. The late-career Lasch angrily lambasted upper middle class women for pretending that entering the work force without altering the fundamental forms of industrial capitalism was anything but a way to maintain class prestige and power. Two career families and equal access to jobs might appear liberating at first, he contended, but they were only bringing women into the ills of corporate capitalism without transforming the system for the better of all. These are important interventions, ones that Lasch shared with socialist feminists. But his interest in demonstrating how the traditional family had been a key site of mutual obligation, sacrifice and commitment for all—men and women (and children)—led Lasch to minimize how the family itself had been a patriarchal institution whose inequities themselves undermined the common life (Lasch does something of the same kind of operation in his mention, then overlooking of the xenophobia, racism, sexism, and paranoia of the nineteenth century populists).

The flaws of the traditional family were precisely what led feminists such as Ellen Willis to decide that there was no turning back. The path beyond modernity’s ills had to be through modern experiences themselves. These could be—indeed they were for her coming of age as a woman in 1950s America—subversively radicalizing steps on the way toward a more thorough and thoughtful revolution. For Willis, the problematic but quite real liberations experienced in the sphere of consumer capitalism (a sphere gendered female already) were openings to deeper political efforts. “The history of the sixties,” she wrote in 1981, “strongly suggests that the impulse to buy a car and tool down the freeway with the radio blasting rock and roll is not unconnected to the impulse to fuck outside marriage, get high, stand up to men or white people or bosses, join dissident movements.” The language here—”not unconnected”—reveals Willis’s own careful scrutiny of how these linkages between pleasure and power worked in actuality. And they remind us that she, like Lasch, was not simplistically committed to liberation as a straightforward path to the common life.

Lasch came to be convinced that the common life could not be achieved within the constraints of modern individualism’s insistence on liberation. Hence “Women’s Liberation” fell directly under fire in the ill-tempered condemnations of his later work. For Willis, however, the patriarchal legacy of traditional constructions of family and public life alike meant that there could be no turning back to pasts in which women were fundamentally restricted from shaping their fates. The path to mutual obligation, sacrifice, and commitment had to travel through whatever experiences of liberation could be grasped at hand in the existing system, she believed. He argued for a common life that might, in its return to tradition, liberate Americans through a renewed emphasis on limits. She responded that “collective liberation without individual autonomy is a self contradiction.” The past was of less help than Lasch thought. Indeed, it was of no assistance at all other than as a long litany of examples of what should not be repeated in the lives of women. The path forward was…forward. Without something new, women could never imagine, never mind achieve, full participation in a common life worthy of its very commonness in all senses of the term, whether it be its everyday ordinariness or its accessibility for everyone.

That Willis took such umbrage at Lasch’s work bespeaks the similarities as well as the differences between them. Both agreed that the current situation was untenable. And both searched for a common life that might replace it. What is intriguing to me is that mid-career Lasch offers intersections with Willis’s position—even presages it—that his later writings do not. Rather than merely dismiss the liberation in Women’s Liberation in his mid-career writings, Lasch kept his focus on the need for the second wave feminist critique of the family to expand to an analysis of the connections of the family to larger structures of power in society (as indeed many socialist feminists were doing at the time). Here is Lasch in World of Nations, the essay collection published in 1974:

What will emerge from the new criticism of the family is not yet clear. Whether the latest wave of feminism leaves a more lasting mark than earlier waves depends on its ability to associate criticism of the family with a criticism of other institutions, particularly those governing work. If the attack on the family results merely in the founding of rural communes, it will offer no alternative to the isolated family or to the factory, since in many ways the rural commune simply caricatures the new domesticity, reenacting the flight to nature and the search for an isolated and emotionally self-sufficient domestic life. To be sure, it reunites the family with work, but with a primitive kind of agricultural labor which is itself marginal. The “urban commune,” in which the members work outside, avoids these difficulties, but it is not clear that it is more than a dormitory—in particular, it is not clear whether it can successfully raise children.

Lately, there has been a tendency for the attack on the family, like so many other fragments of the new left, to degenerate into a purely cultural movement, one aimed not so much at institutional change as at abolishing ‘male chauvinism.’ I have already criticized the illusion that a “cultural revolution,” a change of heart, can serve as a substitute for politics. Here it is necessary only to add that the criticism applies with special force to feminism, since the peculiar strength of this movement is precisely its ability to dramatize specific connections between the realm of production on the one hand and education, child rearing, and sexual relations on the other. It ought to be recognized, for example, that large numbers of women will not be able to enter the work force, except by slavishly imitating the careers of men, unless the nature of work undergoes a radical change. The entire conflict between “home and career” derives from the subordination of work to the relentless demands of industrial productivity. The system that forces women (and men also) to chose between home and work is the same system that demands early specialization and prolonged schooling, imposes military-like discipline in all areas of work, and forces not only factory workers but intellectual workers into a ruthless competition for meager rewards. At bottom, the “woman question” is indistinguishable from what used to be known as the social question (pp. 157-158).

I think it is this “social question”—which we might also define as the relationship between what Lasch would later come to call work and love, and which Shannon describes as the great tension between modern visions of social unity and individual autonomy—with which the contemporary social and cultural critic must continue to grapple. As Lasch remarked in World of Nations:

…it is only, in short, when we are confronted with the contradictions of individualism and private enterprise in their most immediate, unmistakable, and by now familiar form that we are forced to reconsider our exaltation of the individual over the life of the community, and to submit technological innovations to a question we have so far been careful not to ask: Is this what we want? (p. 307).

And here is none other than Lasch’s supposed arch-nemesis, Ellen Willis, writing in a rather similar vein on the limits that subversive mass art experienced in the sphere of consumption can have when it comes to politics. This is from her introduction to the 1981 collection Beginning to See the Light: Sex, Hope, and Rock ‘n’ Roll (interesting that she, like Lasch, arrived at “hope” as a keyword):

…neither mass art nor any other kind is a substitute for politics. Art may express and encourage our subversive impulses, but it can’t analyze or organize them. Subversion begins to be radical only when we ask what we really want or think we should have, who or what is obstructing us, and what to do about it (xviii).

Two very different perspectives, written in different registers, but they share a common point: the politics of progress may have their origins in the technological capacities of modern capitalism and liberalism to generate abundance, pleasure, and fun—and great wealth for a small slice of the population—but they have to move to something other than this ideal of progress to develop their politics any further. To progress requires abandoning the dream of progress, instead recognizing the cost of liberation as an end in itself (a self-defeating and narcissistic one, as Lasch famously realized) and, as an alternative, seeking out new hybrids of tradition, modernity, and futurity.

For Lasch and Willis alike, this search might be fueled by moving from analysis to what is a rather stunningly simple kind of “asking” that stops us in our tracks for a moment as it intermingles the individual and the collective, the me and the we. “Is this what we want?” Lasch asks. “Subversion begins to be radical only when we ask what we really want or think we should have, who or what is obstructing us, and what to do about it,” Willis writes. There is a faith, a hope, in these two sentences, a form and a mode of engaging in contemplation within the modernist framework. As Lasch himself wrote in World of Nations, “Part of the job of criticism today would seem to be to insist on the difference between attempting to give popular themes more lasting form and surrendering to the absolute formlessness of the moment” (335). If our modern (postmodern?) moment has a formlessness to it even more paralyzing than the one Lasch experienced in the early 1970s, then offering a criticism that has some shape seems all the more important. Bringing Lasch and Willis together in a dance of thoughts might provide a way out—or better said a way further into—contemporary quandaries. For only by going fully into them can we hope to reshape them.

It seems to me that contemporary social and cultural critics might learn from Lasch’s mid-career interest (and Willis’s too) in making distinctions within modernity rather than either simplistically celebrating its liberatory thrusts or rejecting its traditions of inquiry wholesale. The past and its usable traditions can matter here. The premodern too. But only in hybridized forms. The goal would not be jeremiad but rather a wrestling with the angels (and the devils). If this be what Shannon refers to as “thought in motion,” without foundations, then so be it. But perhaps thought in motion can itself become a foundation for the common life. The very energies of conversation become a means not merely of going through the motions, but rather concentrating our attention on what is at stake in the moment as it is historically located. They provide a space in which social and cultural critique can be affirmational even in its negations, and negate forcefully when affirmation is problematic.

At its best, social criticism in this vein becomes relevant without being relativist, instrumental without being instrumentalist, self-reflective without being solipsistic, communal without constraining the call for equality among different voices, critical without foreclosing hope. It asks us to explore the limits of insisting upon no limits while also reminding us that we still must carry on within the paradoxical traditions of modernity—both the dominant ones and the hidden ones—as they exist. It might even, to refer again to Shannon’s conclusion in Conspicuous Criticism, provide a way of informalizing the formal rather than what he discerns in modern social science as the continual formal scrutiny and, hence, colonization, of informal, everyday life. At the very least, it offers a mode for potentially connecting thinking to doing, asking to answering, making new to remembering old from within our current, vexing, deeply imperfect, and sucky stuckness in the middle.

November 7, 2013

Christopher Lasch’s Reflection

on christopher lasch’s underappreciated mid-career essays & the future of radical social criticism.

X-post from the US Intellectual History Blog.

I used to wonder sometimes, bicycling to work at Northwestern University, which of the suburban houses I was passing in the leafy suburb of Evanston, Illinois, was the former home of Christopher Lasch. Lasch taught at Northwestern from 1966 to 1970. I have since learned from Lasch’s biographer Eric Miller precisely where the historian and social critic, who eventually settled at the University of Rochester for the duration of his career, lived (for the record, it was roughly where I suspected). These bike rides took on a symbolic quality for me. Finding the home, the root, of Lasch’s work—and also discovering a way to be at home with his work myself—became much on my mind over the last year as I worked intensively on an essay about “Lasch as social critic” for the wonderful print magazine The Point.

Lasch is a complicated figure, dismissed on the right for never quite completely abandoning a radical position, yet also condemned on the left for his seemingly conservative critique of progress and liberation in all forms. In my essay, I hoped to lift Lasch out of this vice-grip of clunky left or right, liberal or reactionary, categories. My hope was to do so by returning to the essays he wrote in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Lasch resided in the very place I now work.

Lasch actually didn’t much like his time at Northwestern. The university “has no political life at all,” he complained to his much beloved parents, the Pulitzer Prize-winning liberal newspaper editorial columnist Robert Lasch and the philosopher Zora Schaupp Lasch. Its History Department was “not a department at all” but rather “the kiddie corner, where the department is largely controlled by the bag-lunch and basketball set—a more obnoxious collection of young fogeys would be hard to find” (quoted in Miller’s Hope in a Scattered Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch, p. 154). Yet despite his alienation from Northwestern, it was during these years that he wrote some of his most engaged, subtle, and now underappreciated work.

To get to that work required thinking more broadly about Lasch’s entire career. And this was something that my editors at The Point urged me to do as we engaged in the extensive back and forth commentary and revisions of the magazine’s editorial process (as an aside, is there no greater and no more unsung role than the editor in contemporary scholarly life? Should we not be pushing for the recultivation of editing, a dying art, in these times of the permanent crisis of the humanities?). So my essay, which began as a kind of “insider baseball” effort to get existing fans of Lasch to pay more attention to the lesser-known work of his middle career, turned into something bigger and, I hope, more accessible and appealing to a wider audience of readers. It became an exploration of Lasch’s larger lines of thinking across his career as they relate to the contemporary possibilities and problems for radical social criticism.

To those larger lines of thinking then. Lasch is most famous, if remembered at all, as the author of The Culture of Narcissism, a curmudgeonly and difficult screed from the late 1970s that, in an unlikely turn of events, made it to the American bestseller list. Narcissism lambasted the structures of power in American life, most especially consumer capitalism but also, more controversially, the professional experts in the welfare state, for depriving Americans of the resources to build strong internal character and, from that development of the inner self, create autonomous and thriving families and communities. In its search for the crisis of civic life in post-60s America, this was a book that took seriously the psychoanalytic understanding of narcissism. Which is to say that Lasch did not mean the common usage of the word to mean self-absorption, but rather he referred to its more classic, formal definition: the inability to distinguish between self and world (Narcissus’s own plight when he could only see his own reflection in a pool of water). Not unlike a contemporary thinker of Lasch’s working in a very different vein—Michel Foucault—and not entirely unconnected from the Frankfurt School critique of Enlightenment rationality and modernity—best articulated by Horkheimer and Adorno—Lasch wrote specifically in the US context of the ripping away of the boundaries around the self so that the market and the state could expand their influence over everyday Americans.

With its critique of structural power as it manifested in American cultural and intellectual life,Narcissism carried forward a number of Lasch’s concerns from his breakthrough 1965 book The New Radicalism in America, which explored the emergence of intellectuals as a new status group in the US over the first half of the twentieth century. The “intellectual as social type,” as Lasch put it, conflated cultural rebellion against a parental Victorianism with political efficacy in a modern, industrializing America. This, Lasch argued, paradoxically added a debilitating dose of anti-intellectualism to the intellectual role and replaced clear thinking with either romanticizations of the lower echelons of society or a coddling up to institutions of power in the name of “action.”

Lasch would have none of this, and his work grew at once more magisterial and more bitter after the success of The Culture of Narcissism in the late 1970s. At the end of his life (he died of cancer in 1994), Lasch released two books: his magnum opus True and Only Heaven, which analyzed the problematic ideal of “progress” in the United States, and The Revolt of the Elites, a clever transformation of José Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses into a polemical critique of upper-class managerial professionals, who Lasch claimed had utterly lost touch with what mattered in shared civic life by embracing an unmoored drive for personal success. He did not go so far as to call these new elites “latte-drinking liberals” or “bobos in paradise,” but he might as well have.

Against the upper-classes, Lasch sought to resuscitate the late-19th century populist movement’s interest in religious callings, the cultivation of republican selfhood, and the embrace of limits. For sustenance and inspiration, he turned to what he took to be the gritty but resigned attitudes of the existing lower middle class, inceasingly in tatters then and only more ragged today than when he wrote his last books. It was an unlikely turn of events for a thinker who had, in The New Radicalism, thoroughly critiqued intellectuals for their romanticizations of the common man in America. And together with Lasch’s rather tin ear for the range of positions articulated within second wave feminism, it undercut what made his work so powerful.

Lasch’s relationship to women’s liberation is particularly fascinating and something my essay did not have space to explore fully. By the 1970s, Lasch increasingly did not approve of said liberation. This was not because he wanted to keep women in their places, or some such nonsense, but rather because he viewed all liberation as a bad move for building a sustainable radical movement for all people. To him, the move toward liberation, untethered from any actual structural transformation of American life, fed right back in to the ideologies and operations of capitalism and professional-managerial domination since these had no problem with liberation per se. Indeed, the awful but brilliant perception Lasch had was that capitalism and managerial-professional expertise both fed on the elusive search for utopia. Of course, certain second wave feminists were already saying this, and Lasch seemed to ignore them (see Ellen Willis’s amazing takedown of Lasch’s posthumous book, Women and the Common Life: Love, Marriage, and Feminism, published as “Backlash,” Los Angeles Times Book Review, 12 January 1997, for a good example of how his work missed the mark with second wave feminists). Nonetheless, the recent debates over Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In movement bespeak much of what Lasch noticed back in the late 1970s and thereafter (see, for instance, Kate Losse, “Feminism’s Tipping Point: Who Wins from Leaning in?”, or bell hooks, “Dig Deep: Beyond Lean In”). So even in the case of women’s liberation, where Lasch seemed somewhat less attuned in his thinking, his work remains relevant.

As someone who has written a book that takes seriously the moments of liberation people felt, and then grappled with, when they experienced rock music in the 1960s, I found Lasch’s critique of all forms of liberation a profoundly useful challenge to confront. For Lasch, liberation was inextricably tied to his dismissal of modern liberalism as a whole. To Lasch’s mind, the modern liberal search for technocratic progress and perfection led to such madnesses as the Vietnam War, with all the social, ethical, and environmental degradation that it not only encompassed but also came to symbolize. At first glance, his rejection of liberalism seemed to make Lasch yet another onetime liberal “mugged by reality,” as onetime Trotskyist turned neoconservative Irving Kristol once remarked of his shift rightward. But Lasch was different. His interest in conservatism stemmed from a radical position that he never forsook. Even though one could easily argue that True and Only Heaven and Revolt of the Elites succumbed to the very misconceptions that Lasch noticed among intellectuals in New Radicalism, he remained an extraordinarily subtle and clear-eyed thinker (for instance I am leaving out all the nuance found in books such as Haven in a Heartless World and The Minimal Self, which might be read as a precursor to Culture of Narcissism and a sequel to that most famous of Lasch’s books). Lasch’s prose had a way of sympathetically but forcefully dissecting arguments and exposing their inner workings in the name of pushing their best ideas and intentions forward while rejecting where they went wrong.

Lasch himself, in his book reviews, was a kind of social critic as editor, something that made me appreciate all the more the back and forth with the editors of The Point concerning my essay about him. There was less a shrill romanticism in his work than a deep engagement with troubling issues, viewed from a lifelong commitment to speaking truth to power in the search for a radicalism that might not simply explode in paroxysms of rage but rather create the conditions to sustain a common good life for all.

That said, what was dismaying about the arc of Lasch’s career to me was that while he never became a neoconservative, by the end of his career he did back away from his most ambitious efforts to write historically-informed social criticism. It was in the aftermath of New Radicalism‘s success in 1965 but before his turn to a more angry and perhaps brittle declensionist tone by the time of Culture of Narcissism that Lasch sought to imagine and embody a different role for the radical social critic than what he had seen in the thinkers featured in New Radicalism and to which he would later himself fall prey. In these years, he had not yet thrown in the towel, as it were, on the possibilities of the emergence of a vital radical politics that arose through the civil rights and the anti-Vietnam War movements as well as the counterculture. He never entirely embraced them, but he wrote in conversation with them. He was, during these years, one and the same time a penetrating analyst of the liberal establishment, a firm opponent to the startling rise of reactionary right-wing politics, and an independent but critical ally of the younger New Left.

Eric Miller, Lasch’s aforementioned biographer, portrays this period as a kind of lost, searching time for Lasch, but to me it is when he did some of his most incredible work. As the historian Jackson Lears, someone who I think of as taking up the mantle of Lasch’s approach, wrote in a survey of Lasch’s career, “It is difficult to recapture the spell that Lasch cast over a generation of historians and cultural critics who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s” when his writing “seemed to light up the whole dreary landscape of debate during the Vietnam War.” This was because, as Lears puts it, “In a time when public discourse was dominated by the bland horrors of ‘tough-minded’ technocratic liberalism, the increasingly mindless liberationism of the New Left and return of the diabolical clown Nixon and his retinue of thugs, Lasch was a sharp, sustaining presence in American intellectual life” (Jackson Lears, “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” The New Republic, 2 October 1995, 42). Engaged in efforts to foster a more robust and connected intellectual life connected to social democratic politics during this period, Lasch wrote essay after essay that refused to retreat to the more fatalistic and exhausted positions that came to dominate his later work. It was these essays, book reviews and short pieces reworked into the two collections The Agony of the American Left and World of Nations, that I wanted to recover and highlight in my essay for The Point.

These essay collections are today more relevant, more applicable to contemporary quandaries than the more famous early and late books of Lasch’s career. His earliest work seems from a bygone era, when Cold War liberalism, with its doomed mix of welfare programs and hardline foreign policy, seemed to be the only game in town; his later work, while still illuminating of the problems with technocratic, managerial liberal thinking, does not speak to the outrageous attacks from the right on the any sense of the common good whatsoever. To me it’s the middle period Lasch that has increasingly been ignored when it comes to this social critic’s legacy. Reading Marx and exploring the cultural Marxism of Gramsci, E.P. Thompson, and Raymond Williams, arguing with and working alongside fellow radical US historians Eugene Genovese (before he himself went neoconservative), James Weinstein, and the journalist Barbara Ehrenreich, engaged with the possibilities and the problems of social democracy, paying attention to the student movement and other dimensions of the New Left without fawning over their growing militant vanguardism, honoring the best aspects of populist, working class, and even bourgeois thought and practice without turning a blind eye to the shortcomings of these positions, and curious about what the late Tony Judt has called, more recently, the “rethinking of the state” rather than its wholesale dismissal—this is the Lasch I found the most compelling.

Paradoxically, the less definitive mid-career work of Lasch should be understood, to my mind, as the most long-lasting. Its searching quality, its empathetic but fierce scrutiny of ideas relevant to pressing matters of the day, its lack of polemics or set judgments, its reflexivity instead of simple reflex responses—in sum, its evidence of thought in motion, forceful but open to subtle shifts and cross-cut lines of possibility in the thinking of others, makes it more significant, in its odd way, than Lasch’s more realized arguments and positions earlier and later in his life. Reflecting (non-narcissistically I hope) on Lasch’s own reflections during this mid-career period offers contemporary social critics a way to think through our own dilemmas of how to comment, react, and respond to the world around us. During the years when he wrote uncomfortably between radicalism and conservatism, when he began to sketch out a new combination of the two that defied existing categories of thought, the time when he did not just see the failings of liberalism everywhere he looked, this to me seems to be the Lasch most worth paying attention to now. To do anything less is to miss Lasch’s own quest to turn to the past not as a mirror on the present, but as a resource for confronting current crises.

See an excerpt of my essay on “Looking Back: Christopher Lasch and the Role of the Social Critic,” in the Fall 2013 issue of The Point. And subscribe, if you can, to this great journal of independent thought and social criticism.

November 4, 2013

Hear Here!

Please join us for the next NUDHL (Northwestern University Digital Humanities Laboratory) meeting:

#dhsound: Digital Humanities and Sound Studies

With special guest, Jonathan Sterne, McGill University, author of The Audible Past, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, and editor of The Sound Studies Reader.

**Note special time and place**

**Wednesday, November 6, 2013, 11am-1pm, Ver Steeg Lounge, NU Library**

#dhsound: Digital Humanities and Sound Studies

In this session, special guest Jonathan Sterne, Department of Art History and Communication Studies and the History and Philosophy of Science Program at McGill University, author ofThe Audible Past, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, and editor of The Sound Studies Reader, will join us for an informal discussion of digital sound studies. Michael Kramer and Jillana Enteen moderate. **Special Event: In lieu of our usual monthly Friday meeting, we are convening on Wednesday, 11/6, 11am-1pm in the Ver Steeg Faculty Lounge, Northwestern University Library. Coffee and pastries served. All are welcome to join the conversation.**

For reading and more information: http://sites.weinberg.northwestern.edu/nudhl/?page_id=840.

November 3, 2013

For An Unreliable Criticism

I think criticism is one person’s flawed and subjective account of an experience. What I don’t like about the “rough draft of history” statement is that it somehow elevates criticism to this thing that is set in the record book. It places an undue emphasis on getting it right or getting it down for posterity, and I don’t think criticism is reliable that way. People have all sorts of agendas, and the “rough draft” of history would be implicated in the production of a “one true version” of a history. Also, it diminishes what criticism can do as an elucidation of thought, as an art form on the page, it diminishes what can be really galvanizing and powerful about this form, and it aggrandizes it in a way that is distasteful to me. And if people are writing with that over their shoulders, I don’t think it’s doing them any favors.

A text by La Rocco, written (after reading five pages of Edward Said) as a site-specific piece for the wall of photographer José Carlos Teixeira’s studio as part of his Translation(s), a project developed at Headlands Center for the Arts, 2013. Photo: José Carlos Teixeira.

Writing About Dance Is Like Poetry About Architecture

…at a certain point the fact that it was an impossible thing to do—write about performance—started to get really exciting. My training is in poetry, and I started seeing a lot of the similarities. My way into a lot of contemporary dance is through poetic structures. Structurally, the two forms seem to be in conversation in interesting ways.

Claudia La Rocco. Photo: José Carlos Teixeira.

November 1, 2013

Going to Ground

kate corby & dancers, digging @ chicago cultural center, 24 October 2013.

If Kristina Isabelle Dance Company’s The Floating City was about motion that perhaps hid a longing for stillness (see “Sinking In to The Floating World”), then Kate Corby and Dancers’ Digging, the first iteration of a developing piece, was about starting with a stillness that gave way to motion.

In The Floating City, the movement energy seemed to seize the dancing bodies, to erupt upon them, to guide them away from interiority. Yet this left the viewer (at least this one) with a sense that the dancers were actually exploring, in a kind of negative space, a worry about what was actually inside, what came from within: where was the self, exactly, when set free, unfixed and floating, to explore the surreal cityscape of contemporary times?

Digging, by contrast, started from a very different place. Corby and troupe used 20 minute sessions of group meditation at the start of each rehearsal as a research tool, and the performance itself started with six dancers standing in place in a diagonal formation for an extended duration. That they were standing and not sitting in cliched meditation poses presaged the dance to come, which was not about meditation in of itself, but rather seemed to be about ideas, gestures, feelings, statements of the self, and questions about relationships that might arise from engaging with stillness.

Stillness here seemed to become, perhaps paradoxically, a force. It at once grounded the dancers. It kept them. Yet it also catapulted their bodies into the externalization, the expression, of what had been inside. Stillness was generative of motion.

Digging took its time to get going. Dueting dancers locked hands, forearms, and explored the weight between them, the push and pull. The motions were stiff, formal, poised, restrained. Things were tentative. Then, gradually, over time, the dancing grew more fierce, more free. At the temporal and thematic center of the work was Josh Anderson’s solo, in which his body’s slow, rigid posture gave way to waves of motion that shot through his limbs, up and down his torso. Where the motion had been linear up to that point in Digging, suddenly it spiraled. Anderson collapsed and rose again. Energy roiled through his muscles from fingertip to solar plexus and back out again. The other dancers followed in increasingly complex arcs of motion.

Yet it all came from a place of centered grace. As the final section of Digging combined various duets to culminate in a beautiful ensemble of repeated gestures given new life as they played off each other, we moved from individual to group, from self to society. It proved to be a meditation on how to trace the bodily line between the interior and the exterior.

From this composed composition, this going to ground, something quite charged and electric emerged.

Links:

Kate Corby & Dancers Present Digging.

Kate Corby & Dancers.

October 31, 2013

Historical Ambivalence & Understanding

The writer’s empathy…is…itself born in voyeurism. Understanding the past is inextricably bound up with guilt: writing history requires an imaginative leap into a time and a place where one was not, an exercise insisting upon a simultaneous violation of and identification with the other. This book…lays bare the ambivalent process of writing history. It also, I hope, reveals something about what it means to understand.

— Marci Shore, The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe, quoted in Norman Davies, “The Deep Stains of Dictatorship,” New York Review of Books, 9 May 2013.

Featured image: Eustache Le Sueur, The Muses Clio, Euterpe and Thalia (1640/5).

Trickle-Up Economics

a rising tide that lifts all yachts.

These findings defy a core precept of conservative economics, the premise that economic growth requires financial investors to be richly rewarded, an idea disparaged by critics as trickle-down economics. The postwar era, by contrast, was an age of trickle-up. Some creditors lost in the short run, but broadly shared prosperity stimulated private business. Eventually, the rising tide lifted all yachts.

— Robert Kuttner on Carmen M. Reinhart and S. Belen Sbrancia’s findings in “The Liquidation of Government Debt,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16893, March 2011, mentioned in review of David Graebner’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years, New York Review of Books, 9 May 2013.

Featured image: Saul Steinberg. The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Sinking In to The Floating City

kristina isabelle dance company, the floating city @ links hall, 24 october 2013.

Diana Deaver (left) and Kristina Isabelle (right) in The Floating City. Photo: Ryan Bourque.

So. floating on the margin of the ensuing scene, and in full sight of it, when the half-spent suction of the sunk ship reached me, I was then, but slowly, drawn towards the closing vortex. — Ishmael, Moby Dick

Hi-def film footage, a body sprawled out on a barge floating aimlessly across the water, the Chicago skyline from Lake Michigan, candles, broken glass, flowing water in closeup; a dancer in a skeletal, spiky fish-like costume crawling over a miniature skyline; another dancer hanging off of a larger art deco skyscraper set; flashlight illuminated lantern boxes.

The imagery and themes came fast and furious at the start of Kristina Isabelle’s The Floating City. It felt like too much, too quickly, an overwhelming clutter of themes and concepts that threatened to sink The Floating City under the weight of its own intriguing ideas. The pacing was frenetic, leaving an audience member unsure how to catch it all, reel it in. Only when the film and set moved to the background did things got more interesting. Indeed, the piece might have been stronger if slowed down and even stripped everything away but the dancing. That alone was enough to sustain attention.

This was a piece about four flaneuse journeying through a Chicago-like contemporary setting. The dancers were forceful, their gestures athletic and virtuosic: expressive juts and chops, extensions of sinew, thrusts of muscle, snaps of energy up the spine and out the head. This was dexterity and concentrated power, controlled exertion on display.

The movements hardly seemed floating or dreamy or surreal, but rather assertive, almost showy. These wanderers in the city were hungry for experience, certain that they belonged, longing to discover and experience urban life. These were four women out on the town. They were not tender, but rather bordering on incendiary, throwing themselves around the city rather than floating in or on it.

There was no time for lingering in this piece, but rather a need expressed throughout to leave one’s mark, to shoot across the grid, to burst through walls, as the dancers quite literally did in one filmed sequence. These dancers wanted to shake their city up, leap across its skyline, dig deep into its layers, speed around its corners, and zoom up and down its streets till dawn.

The individual was the main unit of expression here rather than the group. With this focus on the solitary dancer rather than the ensemble, The Floating City became something graceful but not ethereal. It accessed the vernacular movements of young people on a Saturday night, energy and desires and curiosities and the freedom of youth coiled up tight, unleashed with a roaring ease. These were isolated figures on the prowl, conquistadoras of the nightlife, aware of their own powers, taking pleasure in their assertions of virtuosity, seeking danger, impervious to failure or harm. Yet shadowing their bursts of intense movement and self-assured energy was something else too: loneliness.

Perhaps it was because the solo work so dominated the ensemble interactions, but there was something intensely cold, icy, even cruel, lurking in the dance. There was little in this floating world to ground the individual. And even the individual dancing somehow seemed to erupt on the bodies rather than from within them. This kind of floating might not, in fact, be as liberating and pleasurable as it first appeared. Being a flaneuse was, perhaps, not all it was cracked up to be. There was a nagging anxiety below the confident expressions of virtuosity: at some level, the dancing suggested, beneath the stellar, almost frantic, but always controlled movements that defined the performance, these characters were trying to avoid a state of concern about their unmoored places in the urban environment that they moved through with such seeming assurance.

The more the dancers pushed at the imagined world of The Floating City, the less they found there to sustain their efforts, and hence the more forcefully, the more desperately, they danced. This made for something to think about: perhaps not an easy, open, airy feeling of floating in any simple sense, but rather a drive to soar emanating from a not-quite-conscious worry about gravity’s pull. Here was an impressive flexing of the body out into space to prevent the reflexive act of turning back inward, toward interior self-scrutiny.

In the noir-ish vibe of The Floating City, there was, fittingly, some kind of cover up. Stepping out with a grace and pizzazz expressed in almost-violent motions of the body also revealed the hint of fear that if one stopped moving with such force and grew still, everything might fall to ruin.

The Floating City (solo draft work) from Kristina Isabelle on Vimeo

Links:

Kristina Isabelle Dance Company.