Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 88

June 9, 2013

The Music of Politics

Music itself should not be used for political or any other purpose. But although you cannot make music through politics, perhaps you can give political thinking an example through music. As the great conductor Sergei Celibidache said, music does not become something, but something may become music.

— Daniel Barenboim (h/t to Bill Sharpe)

Zap!

Electromagnetism has made possible new kinds of narrative.

—Thomas Lacquer, “Why name a ship after a defeated race?,” review of various books, exhibitions, films about the Titanic disaster, London Review of Books, 24 January 2013.

May 13, 2013

Thinking About “Technologies of Thinking, of Processing, and of Making Distinctions”

My next post on the Open Thread on The Digital Humanities as a Historical “Refuge” From Race/Clas/Gender/Sexuality/Disability. Full context here: http://dhpoco.org/2013/05/10/open-thread-the-digital-humanities-as-a-historical-refuge-from-raceclassgendersexualitydisability/.

—

I am interested in connecting Anne Balsamo’s articulation of post-identity social analysis (“queer, feminism, post-colonial thinking, race….aren’t really about identities…but rather about technologies of thinking, of processing, and of making distinctions such that the plentitude of what reality is gets ‘processed’ to ‘be’ one thing and NOT another”) to the current debate between David Golumbia and Rafael Alvarado about digital humanities and cultural studies.

I’m approaching this as a cultural historian who spends a lot of time learning from cultural studies, gender and sexuality studies, literary studies, and cultural anthropology but is not deeply embedded in any of those worlds.

It strikes me that Anne’s articulation of one way we might think about identity in non-essentialist ways—in place of static identity we shift to understanding it as generated by “technologies of thinking, of processing, and of making distinctions”—points toward a fascinating, strange, and intriguing alignment of cultural studies (Anne, is it fair to call your work cultural studies?) and digital humanities around conceptualizations of “technologies” as the means by which power operates. And I mean power here in all its senses: electronic, material, technical, political, epistemological, ontological, historical, economic, ecological, psychological, “biological,” racialized, gendered, classed, normalized, resisted.

“Technologies of thinking, of processing, and of making distinctions.” Can we go a bit more into what we mean by “technologies” here? Is “technology” simply a metaphor for talking about cultural logics? Is it a way of referring to “machines” whether abstract or material, Jamesonian or Turingian? Are words such as “tools,” “technologies,” “machines” precise enough for the work we need to do to better understand DH as a refuge, whether that’s a good or bad thing, and for whom and on what terms?

Most of all, what does it mean in the contested spaces of digital humanities to, in some sense, restrict “technologies” to digital operations alone, to the workings of ones and zeroes, bits and bytes, on-off electrical pulsations (this puts me in mind of Tara McPherson’s work on “lenticular logics”)? In other words, I want to know more about what happens when we start to use the concept of “technologies” as a way of thinking about both power in the social sense and power in the epistemological sense. When we come to know things through computers, what different kinds of “technology” are at work?

Another observation and a few musings on it. I fear this is rather abstract (“abstract machine”?) and half-formed but perhaps it is useful:

It seems to me there are really two conversations going on sparked by Roopika and Adeline’s open thread. One is about inclusion and exclusion in the digital humanities (what projects get to count? who does the speaking and what voices must they use or ventriloquize to speak? Who remains silent or silenced, too scared to participate?). The other is about trying to crack open the discourse itself of digital humanities to see what’s going on inside this new, vexing “technology” that has raised so many hopes and hackles in equal measure.

These two matters (inclusion/exclusion and discourse) are, of course, utterly connected. The challenge we face is how to move between the two. On the first count, we must confront the static identities that are present, named or unnamed; how do we confront these and redress the injustices they create? On the second count, we need to grapple with the underlying (overlording?) forces into and out of which those static identities arrive as if fully formed.

The deeper question being debated here, however, is how the surface appearances of identity and the deeper logics producing them/being produced by them interact. And this relationship can perhaps be better understood by grappling more with what we mean when we use the term “technologies.”

For instance, there is a way in which the debates about digital humanities tend to break down into binaries: who’s in? who’s out?; Type I vs. Type II; etc. What I wonder about is whether the digital has intensified thinking in binaries? It’s either binaries or fluidity? Two sides or rhizomes? As a technology at the material level, why is it that digital code asks us, indeed seems to require us, to toggle between either putting things (and people) into binaries or imagining them in endless networks of decentered, fluid entanglements. Is this all we have at our disposal as our “technologies of thinking, of processing, and of making distinctions”? What else might we discover, invent, render, produce, foster, join, imagine?

This goes to a deeper issue (“technology”?) haunting the debate here. What are the precise links between the material qualities of the digital and the intellectual/ideological logics of social relations? Is the link direct? Homological? Oppositional? A correlation? A horizon? An organization? Is there no link at all? Is there a hyperlink here?

When we think through binary code, does it render everything around it into binaries of a static nature or can it crack open the world into more fluid possibilities? Do we want that fluidity or not? What would it mean? Is there something else to imagine and enact here in place of either static binaries or endless fluidities?

These are but some queries, some terms for searching more deeply into what the “technologies of thinking, of processing, and of making distinctions” are, exactly, when it comes to debating the stakes of digital humanities.

Michael

May 12, 2013

Does This Post Make Me a Tool?

My response to OPEN THREAD: THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES AS A HISTORICAL “REFUGE” FROM RACE/CLASS/GENDER/SEXUALITY/DISABILITY?, http://dhpoco.org/2013/05/10/open-thread-the-digital-humanities-as-a-historical-refuge-from-raceclassgendersexualitydisability/#comment-1907:

This is a rich and multifaceted discussion. I just want to add one observations that it has made me ponder.

The discussion has made me think about the metaphor of “tools” in digital humanities work. This makes sense, because the word “tools” is full of all kinds of associations. It is most of all a way to imaginatively bridge the troubling gap between the individual and the machine, between older modes of production and autonomy and newer ones. It alludes to the romantic vision of handicraft labor; it hints at masculinized visions of work (in ways that Natalia Cecire convincingly proposes are profoundly gendered); it offers a way to overcome questions of scale between the individual and larger, overwhelming, and dehumanizing structural forces (tools are held in the hand, safe and under control, mastered; machines are scary, semi-autonomous, out of control things, watch out, it’s Frankenstein!!); tools are at once something from the deep past, often conceptualized as what makes us human–as in it is our species nature to create and use them–and they are also somehow futuristic, key to a cyborgian vision of humans fusing with machines; tools are a way of mediating between, navigating between, compromising between culture and counterculture (I’m thinking of Fred Turner’s great work here on Stewart Brand in From Counterculture to Cyberculture), as in tools sound are ostensibly small and mobile enough that they can be wielded in an oppositional way by the marginalized, oppressed, impoverished even though it takes the massive infrastructure of modernity, military-industrial style, to create them; and while we’re at it, let’s make a bad joke about tools and all the sexual innuendo therein.

Tools are doing a lot of work for us, not only in building things digitally, but in building the theoretical apparatus for this construction zone. Men at work? Is this union restrictive in its membership? Who’s working for whom, anyway? What kind of shop is this? Won’t get tooled again?

OK, I’ll stop. I could go on, but the main point is this: I wonder if part of developing a better critique of digital humanities as “refuge” from questions of identity, structure, and power might focus a bit more on this concept of “tools” and the work that this term is doing conceptually, politically, institutionally in DH.

Do we want to imagine platforms, software, hardware, code, institutions, universities, funding agencies, bodies, identities, language, discourse, networks, the digital itself all as “tools”? Or are tools some subset of one of those other categories? If everything is a tool, what does that framework get us? What does it obfuscate?

What I’m proposing is not that tools are part of the problem, but rather that the use of that word offers a way into better theorizing and critiquing of what is at stake in digital humanities work (Type 1, 1.5, 2, etc. see Ramsey post and all the responses) in relation to questions of identity, structure, and power, into concepts of building and critical analysis of that building, into issues of individual agency, collective negotiation, and institutional organization, into the nature of things and people and all that gets constructed between and among them.

Michael

May 3, 2013

Attack of the Alt-Acs: Response to Stephen Ramsey, “DH Types One and Two”

Response to Stephen Ramsey’s post, “DH Types One and Two”:

Stephen –

Thank you as always for your engagement with these sorts of dh debates. They do get tiresome, yes, but they are also important for thinking critically about all the different kinds of work going on under the rubric of dh.

I think your typology is productive, but I was also struck by a missing aspect of it. Actually less a missing type than what I would call a slightly different historicization of the humanities computing to digital humanities transition.

What I remember most from the last ten years or so is that suddenly, around 2008 or thereabouts, the “digital humanities” was tethered to the emergence of the “alt-ac” movement. That was the crucial moment when digital humanities became cemented in as the term of choice instead of humanities computing (sure the term was already around, but those were the key years when digital humanities gained prominence).

So I would build upon (we all like to build, eh?) your typology in this way.

(1) Type 1: the humanities computing subfield, as you describe it, already at work with computers dating back to the 1990s (and earlier)

(2) Type 1.5: the appearance of, say let’s call it the “alt-ac/digital humanities tendency,” which burst on the scene around 2008/2009 and positioned the digital as the key to solving the jobs crisis among humanities PhDs by picturing those scholars pursuing a much broader range of intellectual jobs beyond barely existent tenured professorships. Visions of the “big tent,” of an opening up of scholarly activity.

(3) Type 2: the more recent emergence in the last few years of critique and backlash (coming from a media studies/cultural studies orientation often) against digital humanities as a kind of inside-job sabotage of academia by neoliberal forces and ideologies dressed up to seem like liberation from hierarchy, but in fact smuggling in invidious new modes of control and exploitation: the deskilling of academic laborers; the assessment-crazed “show me the data” loss of autonomy over the classroom; the fading of consensus about how the publication process should function; MOOC-ville; and, worst of all, the mirroring at the micro-level of academe what are macro-level operations of surveillance, corporatization, inequality, and faux-populism in contemporary society.

I wonder if the disconnects, the talking past, between type 1 and type 2 dh hinge on the historical emergence of type 1.5, which absorbed and cannibalized earlier practices of humanities computing, but also linked the digital to larger, very fraught and vexing struggles over intellectual labor and work under neoliberalism, corporatization, and privitization in the US and beyond.

I think it is this moment when humanities computing and the “alt-ac” vision came together that needs more attention here. Why “alt” (shades of alt.rock?)? Why were “alt” and “digital” so powerfully connected as driving terms and forces suddenly? It’s questions like these that seem pertinent to the political stakes of defining dh. The seeming randomness of the shift from humanities computing to digital humanities takes on a whole new light when linked to struggles over jobs in the academia, their quality, their precarity, their “alternativeness” and the terms of that imagined alternative.

– Michael

Tweetdendum 5/4/13:

To be clear, “attack of the alt acs” title of my post meant to be silly, like b movie title. Not meant as a slam of alt-ac…

… rather to ask us to think abt the larger forces into which/out if which “alt” surfaces, gains attention.

April 26, 2013

Kramer’s HASTAC 2013 Talk: The Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Sonification of the Ephemeral Past

Slides for my short talk today at HASTAC 2013 in Toronto. You can follow the proceedings online, many panels being streamcast, plus on Twitter at hashtag #hastac2013.

Hastac 2013 Talk: The Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival & the Sonification of the Ephemeral Past from michaeljkramer

March 30, 2013

Paul Williams, 1948-2013

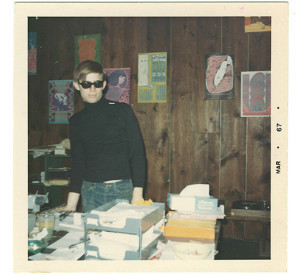

Paul Williams, March 1967. Photograph: David Hartwell.

In the spring of 1967, on the cusp of the Summer of Love, a young rock critic attended a concert at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco and deemed it an “induction center.” It was a clever and sharp reference to the military draft, expanding rapidly that year with the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

The sounds of rock at the Fillmore were as important, this observer believed, as the draft boards that were calling up young men by the tens of thousands in 1967. Something was happening in San Francisco, and to the young rock critic at the Fillmore, what it was was perfectly clear: rock offered passage—”induction”—to a vastly different vision of American life than the war did.

The rock critic at the Fillmore was Paul Williams, founding editor of Crawdaddy! magazine, arguably the first publication of fully-fledged rock criticism in the world. His evocative description of promoter Bill Graham’s psychedelic emporium, mentioned in an album review of San Francisco bands, opens my new book on rock music and citizenship in the sixties counterculture.

Williams died on March 27th, 2013 after a long struggle with dementia brought on by a head injury during a bicycling accident in 1995. (For some wonderful writing, see the blog of his wife, singer-songwriter Cindy Lee Berryhill, who lovingly and bravely chronicled the last years of his life.)

Williams’s keen insights about San Francisco in the spring of 1967 were not utopian, but they were suffused with hope. This East Coast writer, visiting the Bay Area from New York City, looking as cool as Andy Warhol (see photograph above), thought that he glimpsed—and heard—a profound turn to a better civic existence in the streets and parks of San Francisco. For individuals and communities alike, the Fillmore had become the entry point, the processing center, for an emerging counterculture. If you were in search of an alternative to the Vietnam War and all that it symbolized, rock at the Fillmore offered access across the boundary to a different country, what would eventually be called Woodstock Nation.

Williams is an important, and often overlooked, figure in the emergence of rock criticism during the 1960s. His style was confessional, but he postured much less than Bangs, Christgau, and other wonderful but more tough and gritty writers. The early Williams was tender, honest, and unafraid of being vulnerable in print. He was quite young, a drop out from Swarthmore College when he started Crawdaddy! His writing could be clunky at times, but it was also full of keen observations, deep thinking, and passionate feeling about pop music.

I think of Williams as the male counterpart to Ellen Willis. He was less political and more wordy, dreamy, and flowery in his prose, but like Willis, he wanted to register the small subtleties and huge implications alike of his experiences of rock music. And he wanted to do so to capture all the complexity, power, attractiveness, beauty, scariness, and fraught tension of the music as both a commercial and a civic phenomenon.

Williams’s writing was often addressed to a “you”—the reader as friend, comrade, confidant, equal member in a secret society whose messages were being broadcast in code right out in public. Inspired by science fiction fanzines and folk music from his childhood in the Boston/Cambridge area, amazed at the discovery that the latest songs on the radio seemed as resonant, as meaningful, as artful as any kind high art out there, Williams as writer and editor turned Crawdaddy! into a key text for all the rock criticism to follow.

His own effort in its pages to use rock music to make sense of the world still sings out from the 1960s. It is dated, but indelibly so, communicating from a lost time with a young person’s courageously earnest and determined goal to make sense of musical sounds that seemed at once immensely significant and troublingly ineffable.

Rest in peace, Paul. And know, wherever you are, that the strange, fantastic dream of flying the sonic flag of the republic of rock lives on in the words you left on record.

#563 – Paul Williams at the Fillmore

paul williams, 1948-2013.

Paul Williams, March 1967. Photograph: David Hartwell.

In the spring of 1967, on the cusp of the Summer of Love, a young rock critic attended a concert at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco and deemed it an “induction center.” It was a clever and sharp reference to the military draft, expanding rapidly that year with the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

The sounds of rock at the Fillmore were as important, this observer believed, as the draft boards that were calling up young men by the tens of thousands in 1967. Something was happening in San Francisco, and to the young rock critic at the Fillmore, what it was was perfectly clear: rock offered passage—”induction”—to a vastly different vision of American life than the war did.

The rock critic at the Fillmore was Paul Williams, founding editor of Crawdaddy! magazine, arguably the first publication of fully-fledged rock criticism in the world. His evocative description of promoter Bill Graham’s psychedelic emporium, mentioned in an album review of San Francisco bands, opens my new book on rock music and citizenship in the sixties counterculture.

Williams died on March 27th, 2013 after a long struggle with dementia brought on by a head injury during a bicycling accident in 1995. (For some wonderful writing, see the blog of his wife, singer-songwriter Cindy Lee Berryhill, who lovingly and bravely chronicled the last years of his life.)

Williams’s keen insights about San Francisco in the spring of 1967 were not utopian, but they were suffused with hope. This East Coast writer, visiting the Bay Area from New York City, looking as cool as Andy Warhol (see photograph above), thought that he glimpsed—and heard—a profound turn to a better civic existence in the streets and parks of San Francisco. For individuals and communities alike, the Fillmore had become the entry point, the processing center, for an emerging counterculture. If you were in search of an alternative to the Vietnam War and all that it symbolized, rock at the Fillmore offered access across the boundary to a different country, what would eventually be called Woodstock Nation.

Williams is an important, and often overlooked, figure in the emergence of rock criticism during the 1960s. His style was confessional, but he postured much less than Bangs, Christgau, and other wonderful but more tough and gritty writers. The early Williams was tender, honest, and unafraid of being vulnerable in print. He was quite young, a drop out from Swarthmore College when he started Crawdaddy! His writing could be clunky at times, but it was also full of keen observations, deep thinking, and passionate feeling about pop music.

I think of Williams as the male counterpart to Ellen Willis. He was less political and more wordy, dreamy, and flowery in his prose, but like Willis, he wanted to register the small subtleties and huge implications alike of his experiences of rock music. And he wanted to do so to capture all the complexity, power, attractiveness, beauty, scariness, and fraught tension of the music as both a commercial and a civic phenomenon.

Williams’s writing was often addressed to a “you”—the reader as friend, comrade, confidant, equal member in a secret society whose messages were being broadcast in code right out in public. Inspired by science fiction fanzines and folk music from his childhood in the Boston/Cambridge area, amazed at the discovery that the latest songs on the radio seemed as resonant, as meaningful, as artful as any kind high art out there, Williams as writer and editor turned Crawdaddy! into a key text for all the rock criticism to follow.

His own effort in its pages to use rock music to make sense of the world still sings out from the 1960s. It is dated, but indelibly so, communicating from a lost time with a young person’s courageously earnest and determined goal to make sense of musical sounds that seemed at once immensely significant and troublingly ineffable.

Rest in peace, Paul. And know, wherever you are, that the strange, fantastic dream of flying the sonic flag of the republic of rock lives on in the words you left on record.

March 16, 2013

Criticizing After Dinner

What is criticism? Karl Marx had a pretty good idea. On a perfect day in a perfect world, he wrote, a happy citizen might “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening” and, finally and best of all, “criticize after dinner,” perhaps with a bottle of wine on the table.

Marx understood that criticism doesn’t mean delivering petty, ill-tempered Simon Cowell-like put-downs. It doesn’t necessarily mean heaping scorn. It means making fine distinctions. It means talking about ideas, aesthetics and morality as if these things matter (and they do). It’s at base an act of love. Our critical faculties are what make us human.

— Dwight Garner, ”A Critic’s Case for Critics Who Are Actually Critical,” New York Times

#562 – Culture Rover’s Unfamiliar Quotations

dwight garner on why it’s critical to be critical.

What is criticism? Karl Marx had a pretty good idea. On a perfect day in a perfect world, he wrote, a happy citizen might “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening” and, finally and best of all, “criticize after dinner,” perhaps with a bottle of wine on the table.

Marx understood that criticism doesn’t mean delivering petty, ill-tempered Simon Cowell-like put-downs. It doesn’t necessarily mean heaping scorn. It means making fine distinctions. It means talking about ideas, aesthetics and morality as if these things matter (and they do). It’s at base an act of love. Our critical faculties are what make us human.

— Dwight Garner, ”A Critic’s Case for Critics Who Are Actually Critical,” New York Times