Michael J. Kramer's Blog, page 87

July 21, 2013

Mapping Out History

The best global histories will have some of the local in them, and vice versa. It’s a challenge to make room for these nested spheres given the constraints of researching and storytelling, not to mention the constraints of publishing. But it’s fun. There are so many ways to play with the concept of scale. It’s exciting to contemplate a literary analogue or complement to Geographic Information Systems or Google Earth. Our narrative histories can be maps of words.

— Jared Farmer, “Biography of a Landform,” American Scholar, June 2009

Bop Prosody At the Movies

The film cannot control its lust for the tang of actuality, forgetting what it takes to dream a prose narrative into being. Yes, Kerouac’s novel was very close to his life, but On the Road is really its prose. One might say the prose is the main character. How quickly it was written and under what conditions, who knows, any more than one can say what was really behind the tone of Charlie Parker when the sound came flowing out of his horn?

The film never finds a way to embody the sound….

— Andrew O’Hagen, “Jack Kerouac: Crossing the Line” New York Review of Books, 21 March 2013

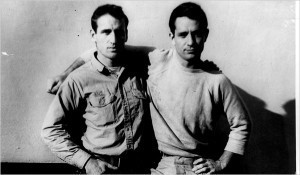

Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac, 1952. Photograph: Carolyn Cassady.

Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac, 1952. Photograph: Carolyn Cassady.

July 17, 2013

Emerging From the Shadows

manual cinema, lula del ray @ Den Theater, 13 December 2012.

The world has become sad because a puppet was once melancholy. — Oscar Wilde

Artifice is essential to the authenticity of Manual Cinema‘s postmodern shadow puppetry. As the name suggests, performances by the group are at once hands on and mediated as MC uses a mix of overhead projectors, screens, actors and actresses, video, sound both live and played back, and more. In Lula Del Ray, which the troupe has staged in Chicago over the last few years and which soon appears in New York City, MC uses odd cuts and varying scales of closeup and framing shots to lend a movie-like quality to the piece. But with the slightly off transitions, the visibility of the transparency plastic around the figures, the live actors just ever so slightly out of phase and position with the props shadowed on the screen, the awareness that this is not a film at all never entirely vanishes.

This renders the performance almost amateurishly theatrical, like watching your kids perform a puppet show in the backyard and, yet, at the same time, you feel like you are at the movies. It is from the imperfections mixed with the surprising juxtapositions of embodied and disembodied that we enter into an in-between space, one in which the live elements increasingly become cinematic and the filmic qualities start to leap out from the (digitized) celluloid. A kind of paradoxical “live” cinema emerges, one that ends up welcoming the viewer into a richly ambiguous space between the recorded and the immediate, the pre-existing and that which is created in the moment. Is it live, or is it Memorex?

The plot of Lula Del Ray works well with the effect produced by Manual Cinema’s approach to shadow puppetry. It’s a dreamlike story about a young girl’s awakening to adulthood among the satellite dishes and mobile labs of some kind of scientific nuclear era installation. We appear to be in the almost hallucinatory landscape of technology and nature in the deserts of the southwestern United States. We catch a bit of the disorienting isolation, the beauty of this landscape: a sea of satellite dishes and other equipment among the mountains, flowers, burning sun, glowing moon, and endless sky.

It is a stunningly stark, desolate, lonely, and disorienting world—so real as to be unreal—which is what makes the in-between mix of live and mediated in the MC approach so evocative. And when the young girl runs away to a city to try to see a dreamy boy band music group that entrances as they perform “live” at a theater (represented through a mix of silhouetted cowboy hat and guitar figures and live music performance), the mix of intense human emotion and distanced inhumane alienation grow to a weirdly hushed roar of feeling, an echoey fantasy of possibilities and problems, learning and loss, presence and absence—all suspended in shadow and light.

Beyond Cooptation: A Response to Ron Jacobs

To the Editors –

Thanks to Ron Jacobs for his thoughtful review of The Republic of Rock in Counterpunch (“Rock n’ Roll Nation,” 28-30 June 2013). I am largely in agreement with how he assessed the book except for one key issue: he implies that I adopt the standard interpretation of cooptation within the system of consumer capitalism to analyze rock music in the sixties counterculture. This standard formula holds that first, an autonomous subculture of rebellion appears, then capitalist corporations coopt it to make a profit, struggle ensues, capitalism wins, and then the cycle repeats with new subcultural formation. What I try to argue in The Republic of Rock, however, is that cooptation is the wrong way to understand the counterculture. Instead, what I contend is that rock and the counterculture were already inextricably embedded within US consumer capitalism and military imperialism. For participants in the counterculture, it was precisely this foundational complicity of rock with dominant cultural, political, and economic forces in the United States that made it so useful, so important, for grappling with all the possibilities and flaws of America during “the sixties.”

This is not rebellion and cooptation locked in a dialectical couple dance but something far more psychedelic. New kinds of “consciousness,” as it was called at the time, popped up in experiences of commercialized music from within the existing order as people used rock to explore the stakes of their lives and their surroundings at multiple levels: intellectual, emotional, corporeal, interior, external, local, national, global, political, technological, economic, spiritual, ecological, and more. A swirl of engagement arose through making and taking in music. It is this swirl that I would define as the counterculture, a social formation that functioned as a kind of momentary rippling of the social order, a bending and warping of the everyday toward other perceptions of how both individual and collective life might be lived, an unsettling but temporary seizure of feeling (as compared to Raymond Williams’ “structures of feeling”) that generated heightened critical awareness. Even though it was fun, hedonistic, crude, transient—maybe because it was all those things—the music was also a crucial means of accessing what we might call the deep politics below the surface politics: the philosophy and psychology of the good life and the ethics of citizenship and civic belonging.

This made rock neither revolutionary, nor commodifiable. Or, better said, it made the music both revolutionary and commodifiable. In either case, the binary of rebellion and cooptation is not a very useful one analytically. It might be better to think of rock as generating a jolt of energy formulated from the very same underlying forces that it seemed to oppose and, therefore, to conceptualize the counterculture as a countercurrent that sparked up from this power surge. As the music “blew your mind,” it did not propose answers so much as raise questions. It brought to light keenly felt wonderings about core questions of democracy, community, individualism, similarity, difference, ugliness, pain, beauty, sinfulness, grace, and human existence itself.

I know this is, for some, making too much of a rather crass, overblown, juvenile mode of musical expression. I am not claiming rock was great art (nor that it was not great art). I am only contending that it mattered immensely to its makers and listeners (which I suppose could be one definition of great art). I am most of all asking why it mattered so much to them? This is simply a question that cooptation theory cannot adequately answer.

Of course, drugs mattered too, as Ron Jacobs points out, as did new mores about sex and new conceptualizations of friendship as kinship. But music was the most plugged into, the most reliant on, the most connected to the larger apparatus of electronic mediation and technological power that structured US market and military domination. So it was music that had the broadest and most intriguing ability to provide access to countercultural participation. In this sense, perhaps the sex and the drugs were merely a way to try to recover what the music first introduced most prominently and provocatively!

Hey, I wasn’t there, man. But that’s the point. One reason why rock and the sixties counterculture return again and again like a skipping LP record (or better said an MP3 file on endless repeat) is that the memory—as compared to the history—of this long-gone era continues to serve as, as Jacobs points out, a “template” for grappling with current affairs. Listening back to rock and the counterculture in a more thoroughly historical way—past memory’s “foggy ruins of time”—allows us to grasp its profound weirdness and to rethink contemporary dilemmas of where culture and politics, citizenship and consumption, civil society and militarization intersect. Which is to say that a new and more precise comprehension of how the music mattered then, in its historical moment, has tremendous intellectual, ideological, political, even economic implications for the present. We need a better and more accurate way of understanding rock and the counterculture not as rebellion followed by cooptation, but rather as a disconcerting yet persistent cluster of sensations that coursed through the existing system: born from it, part of it, questioning it, beckoning beyond it. And to address this we need a more sophisticated model of how cultural politics work and of the elusive but essential concept of citizenship. For this reason, maybe, like Ken Kesey in his infamous appearance at the 1965 anti-Vietnam War rally in Berkeley, it’s time to turn our backs on cooptation theory and say fuck it.

Rock listeners in the sixties, like so many now, were thoroughly entangled in the wires of America’s militarized, corporatized system of consumer capitalism. But even from their compromised positions, they reached for something far more intriguing than rebellion or revolution: without always having the words to say so, many pursued deep inquiries into the nature of citizenship itself; they searched for what Slavoj Zizek eloquently called, in his 10 October 2011 remarks at Occupy Wall Street, “the language to articulate our non-freedom.” This is far different from the endless ping-pong theory of rebellion and cooptation. It was—and can still serve as an historical example for—an investigation into what the structures are, exactly, that are holding everything up.

R-E-S-P-E-C-T-fully,

Michael

July 15, 2013

Turn Up Your Transistor Radio! More RoR on USIH Blog

L.D. Burnett ponders rock music, transistor radios, technology’s relationship to commonality, and life in the ‘Nam after reading Chapter 4 of The Republic of Rock:

L.D. Burnett, “‘Do You Remember When We Used to Sing?,” U.S. Intellectual History Blog, 14 July 2013.

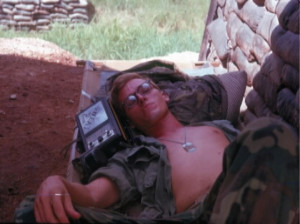

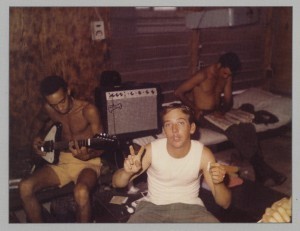

Snapshots of GIs in Vietnam, circa 1970.

More Republic of Rock on U.S. Intellectual History Blog

L.D. Burnett ponders rock music, transistor radios, technology’s relationship to commonality, and life in the ‘Nam after reading Chapter 4 of The Republic of Rock:

L.D. Burnett, “‘Do You Remember When We Used to Sing?,” U.S. Intellectual History Blog, 14 July 2013.

Snapshots of GIs in Vietnam, circa 1970.

July 12, 2013

Republic of Rock Reviewed on U.S. Intellectual History Blog

My dear friend and always sharp colleague Tim Lacy offers the first of a series of responses to The Republic of Rock:

July 10, 2013

Old, Slow & Human: Digital History from Archive to Argument @ ALA, 2013

Ace digital humanities librarian Josh Honn and I co-presented about developing the Digital Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project on a panel at the American Library Association Conference a few weekends ago.

Panel title: Digital History: New Methodologies Facilitated by New Technologies.

Our presentation: Old, Slow & Human: Digital History from Archive to Argument.

Josh has the full report, including slides (also embedded below) at his blog. Don’t miss his very smart comments over there! As usual, it was great fun and there was lots of learning in our continued collaboration between a librarian and a historian.

July 3, 2013

Review in Counterpunch

Ron Jacobs reviews The Republic of Rock in Counterpunch: “Rock ‘n’ Roll Nation,” 28-30 June 2013.

June 25, 2013

Review in DigBoston

Nice review by Blake Maddox, published 24 June 2013 in Dig Boston:

BOOK ‘EM: THE REPUBLIC OF ROCK BY MICHAEL J. KRAMER.

I’m pleased about three things: first, Blake is already quite knowledgable about rock in the sixties but feels Republic of Rock revealed surprising new stories and perspectives on the topic; second, Blake feels the book is accessible to readers beyond academia even as it addresses more specialized debates among professional scholars; and fInally, I like the (almost psychedelic!) experimentations with format in the review and its multimedia approach.

Thanks Blake for the careful reading of the book and your thoughtful review!